Abstract

This study aimed to investigate effects of adjunct model of content-based instruction on EFL students’ technical report writing performance. A quasi-experimental design was employed to attain the main objective of the study. It included sixty-four mechanical engineering students in the control group (31) and experimental group (33). The experimental group participants were taught technical report writing skills using adjunct content-based instruction, and the control group participants were taught the same lesson through the conventional method for eight weeks. Writing tests and interviews were employed to collect the data. One-way MANOVA was applied to analyze the data collected using the tools. The findings revealed that the students participated in the adjunct EFL program outperformed the ones who were instructed through the conventional approach. They improved their skills of writing task achievement, cohesion and coherence, lexical resource, and grammatical range and accuracy significantly. The result also showed that the experimental group students had positive perceptions about adjunct content-based instruction in learning technical report writing. Based on the findings, it was recommended that adjunct content-based instruction could be incorporated into teaching technical report writing at colleges and universities.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Effective technical communication skills are necessary for career success. Engineers and scientists could communicate effectively with the people whom they work. It is not enough for them to be technically smart, they should be skilful in communicating their tasks. For this purpose, engineering educations have strived to equip students with technical skills including technical communication skills. The skills of writing communication demand incorporating knowledge of contents, context, language, genres, and techniques for a writing task.

However, EFL students writing instruction at college and university like in Ethiopia ignores language of content courses in their field of study; as a result, it falls students to communicate their academic tasks effectively. This study examined how adjunct model of content-based instruction effective on students’ technical report writing performance. The findings proved that students could learn technical report writing skills better when they are enrolled in two linked courses. This way of teaching also prepared students for their future academic and professional life.

1. Introduction

Writing is pivotal to the development of various sectors. It is imperative for practical applications of education, business, and international relations. Hyland (Citation2013) states that it is impossible to consider contemporary academic and business life without essays, commercial letters, emails, reports, and minutes of meetings. As a result, the ability to write has become an essential skills in various aspects of life including academic real-life communication skills. Thus, an instructional approach that can integrate English language writing skills and the academic subject matter is content-based instruction.

The concept of content knowledge and language integration is rooted in the ninety-seventies language teaching projects like language across the curriculum, immersion education, and English for specific purpose (ESP) program. According to Richards and Rodgers (Citation2001), language across the curriculum began in British in the mid ninety-seventy. It centered on language in all subject areas across the curriculum. Immersion education is an instructional design in which the regular subject curriculum is taught via a foreign language. ESP is an English language program that integrates English language teaching with the school’s subjects and provides us with specific means of teaching language as communication rather than simply as usage. It focuses on the specific communicative needs and practices of particular social groups (Hyland, Citation2007). Hence, the interdependence of subject matter across the school curriculum and language later became the principal application of CBI in teaching EFL context.

The principles of CBI are also comprehensively rooted in the principles of communicative language teaching (CLT) since they involve the active participation of students in the exchange of content. It aims to develop communicative competencies. In this context, communicative competence is developed when learning about discipline-specific subjects like math, science, social studies, or others (Celce-Murcia, Citation2001; Duenas, Citation2004). Language can be a vehicle to study the subject matter of a content course, and content can be a resource to learn EFL. Such substantial integration of learning inspired linguists to propose several models of CBI. In this case, D. M. Brinton and Snow (Citation2017) identified three prototype models of CBI for teaching EFL: theme-based, sheltered content, and adjunct models of CBI.

Among the three prototype models of CBI, this study focused on the adjunct model of content-based instruction (ACBI) because Villalobos (Citation2013) proposed that the adjunct course provides the most authentic setting in which EFL students can learn effective academic strategies. It can fit with a specific context where learners must develop more determined English content. This model of CBI can also provide the most optimal input for more advanced EFL students enrolled in a regular college or university course. Of the other models, it maintains even emphasis of language and content integrated learning. In this regard, D. M. Brinton and Snow (Citation2017) adjunct instruction is a type of CBI where the two courses both the language and content have had equal weight of emphasis.

It is believed that the current EFL teaching and learning process should bring learners to the center of learning. For this reason, English language instruction at high school and university level, like in Ethiopia, aims to use meaningful contexts. Accordingly, Ethiopian EFL education should be directly linked with other school subjects and reflect the national focus on science and technology (MOE, Citation2018). These are basics that can pave the way to practice ACBI. Therefore, ACBI can be worthy alternative for teaching EFL.

It is generally accepted that students’ writing is more likely to be well organized and fluent when they have a deep understanding and well-integrated knowledge of their writing topic. On the other hand, if students have little knowledge or experience of a topic, their writing may be disorganized and unsupportive (Hyland, Citation2014; Khonsari, Citation2005).). In this regard, an approach like ACBI, which focus on integrating language learning with content knowledge, can be beneficial. It makes students familiar with the subject matter they are assigned to write about and can help students develop effective texts. This is especially important in academic settings, where students are often required to write about technical or specialized topics in their academic courses (Hyland, Citation2014). Thus, this study focused on effects of ACBI on students’ overall technical report writing performance, and it aimed to examine how this approach can impacted on EFL students’ technical report writing skills.

2. Literature review

2.1. Adjunct content-based instruction

Adjunct content-based language instruction is a model of CBI in which students enroll simultaneously in an EFL course and a content course; the courses have jointly synchronized materials and assignments so that the language course supports students’ learning in the content course (Richards & Rodgers, Citation2001; Snow, Citation2001). This model of instruction has mainly been compatible with post-secondary settings in which such linking of courses is feasible. Students are evaluated on content mastery. Therefore, as Carrio-Pastor (Citation2009), adjunct instruction is mainly based on the interplay between content and language and the collaborative work of two distinct instructors. In other words, there is evenly collaboration combined with the content and language-integrated learning approach

ACBI’s approach aims to develop students’ content knowledge and language skills by providing authentic and meaningful academic context. It rooted its theory in cognitive learning theory, according to which the process of acquiring literacy skills goes through three stages: the cognitive, the associative, and the autonomous (Celce-Murcia, Citation2001). In this process, scholars like Celce-Murcia also stated that ACBI should support students learning by linking new knowledge with their existing knowledge and schema. It facilitates their higher-order thinking and motivation by providing cognitively demanding material tasks.

Vygotsky’s sociocultural and social constructivist theory posits learner-centered and contextualized learning. It is also the notion of ACBI. As cited in Celce-Murcia (2000), Vygotsky’s concepts of the zone of proximal development, scaffolding, and inner speech describe how teachers or peers assist learners in their development. They can be effectively realized in ACBI contexts, where they have opportunities to negotiate not only with language but content in an increasingly contextual way. The social constructivist model encouraged EFL/ESL students to learn to interact with others and actively construct personal meaning. Williams and Burden (Citation1997) Beckett et al. (Citation2004) view learning as a social activity that uses EFL to construct meaning from authentic contexts with assistance from more capable others. This assumption can align with the premise of ACBI, according to which meaning is cooperatively constructed in an academic context (Troncale, Citation2002).

According to Celce-Murcia (Citation2001) and Richards and Rodgers (Citation2001), research in second language acquisition, especially Krashen’s comprehensible input hypothesis and Cummins’ and Swain’s theoretical language proficiency framework, are complementary fundamentals of ACBI. These theoretical assumptions claimed that making comprehensible input and output as context-embedded as possible will aid comprehension. CBI has allowed students to be exposed to a considerable amount of language while learning academic content. Thus, CBI aims to promote the integrated development of students’ language competence and content knowledge. Therefore, several theories from different academic disciplines have supported CBI.

Pedagogically, Richards and Rodgers (Citation2001) have two primary reasons for using various models of CBI. The first one was that people learn ESL/EFL more successfully when they use the language as a means of acquiring information, rather than as an end in it. So, it is believed that the primary focus of ACB instruction is meaning rather than form. Therefore, the central organization of this instruction is derived from the subject matter rather than from forms, functions, etc.

The second pedagogical reason for using various CBI-like adjuncts is that it better reflects EFL students’ need to learn their target language. Villalobos (Citation2013) also indicated that ACBI emphasizes students’ need to succeed within the existing context. They said that EFL students must improve their English language skills for various purposes. They are to pass the assessment test, understand lectures and take practical notes on their content-area courses, and understand and answer test questions in both ESL and content-area courses.

Thus, ACBI is pedagogically effective in teaching and learning EFL/ESL, because it prioritizes the meaning that the learners can need at the college or university. Leaver and Stryker elucidate that ACBI is an approach in which language proficiency is achieved by diverting the focus from learning the language to understanding the academic subject matter. So, it helps the EFL/ESL students succeed in the educational content they need to know.

Effectiveness of the adjunct model of content-based language instruction in transitioning ESL students into the college or university academic environment have revealed positive results (Kasper, Citation2000; D. Brinton et al., Citation2003). They believe that adjunct courses are practical and ease the transition into content area classes by teaching the language skills necessary to pass their academic content courses, putting their academic achievements on par with native speakers. D. M. Brinton and Snow (Citation2017) also claim that an adjunct model offers students “two for one“that is, increased language proficiency as well as in-depth mastery of the content subject matter. They have verified it by providing two of the most frequently cited example of adjunct instruction research. They are UCLA’s Freshman Summer Program (FSP) and an English/Philosophy adjunct course offered at an English-medium private university in Turkey (D. M. Brinton & Snow, Citation2017). Accordingly, the outcome of those studies indicates that ACBI has been broadening students’ intellectual background knowledge and cognitive skills and exposing them to unabridged primary source texts.

However, the professional literature on ACBI offers little on this type of information. For instance, Percival (Citation1997) says that the emphasis in CBI classrooms was on having students comprehend the meaning and did not require the students to consider the relationship between language form and content. The argument here is that the adjunct model will succeed or fail in challenges depending on the kind and extent of the collaboration between content and language lecturers. In this case, Angelil (Citation1994) reviews in reporting a writing course in parallel with an introductory biology course, found that because the writing course was dependent on the content of the biology course it was difficult to develop a writing syllabus with a clear pedagogical or linguistic approach. The status of language is dependent on the amount of time given in the tutorial adjunct model. This argument can affect the effectiveness of ACBI. With this respect, the subsequent section focuses on some common opportunities and challenges of ACBI.

2.2. Some major opportunities for using ACBI

Using ACBI has been endorsed by various EFL educators. Scholars like Percival (Citation1997), Kasper (2001) and D. M. Brinton and Snow (Citation2017) found that ACBI is increasing students’ motivation. It is a fundamental reason for ACBI. Students will be motivated to learn a language because they are focused on studying content that they are interested in rather than just studying language in isolation. The focus on content enriches the classroom and makes the ESL classroom more interesting for the students, providing motivation. Some motivation in their EFL program may come from the fact that the students are receiving academic credit for the content course and need English support to do well in the content course (D. Brinton et al., Citation2003). Hence providing a motivational incentive is a major opportunity for using ACBI in EFL instruction like in learning technical report writing skills.

Another potential benefit of ACBI is enhancing EFL students’ academic achievement. Kasper (2001) advocated ACBI as it fosters academic growth and raises EFL language proficiency. Students in EFL instruction learn it interestingly. Richards and Rodgers (Citation2001) and Kinsey (Citation2008) indicate that ACBI classes help students acquire authentically contextualized academic skills. They would prepare them for academic courses they would take later.

Moreover, researchers like Douglas (Citation2017) suggest that the ACBI approach improves students’ literacy of academic subject matter. Students with different language ability levels gained content knowledge equally in the essays written in English; however, lexical development was significant in the low learners of the three language ability groups. Grammar accuracy in clause development was important among those with high language ability. The highest language ability group significantly improved the quality of essay writing. Therefore, ACBI is substantial for learners of all level of language ability in various aspects of language skills.

2.3. Potential challenges of using ACBI

Although the adjunct model offers multiple benefits and strengths, several potential challenges may limit its applicability. First, since the model depends on the availability of content course offerings, a successful adjunct model would be infeasible in an EFL program (D. Brinton et al., Citation2003). In this regard, Perceive (1997) explained three factors used to select the content course for the ACBI program. They are the nature of the content course, including the subject matter covered and the course’s structure and organization; the content professor’s attitude and interest; and whether or not the system meets general graduation requirements for students at that college or university. There are only limited-content courses that can fulfill these criteria at the same time.

ACBI also has its potential challenges in an administrative case. The program requires an administration willing to fund the extensive network of instructors and staff necessitated by the program. It involves the college administrators, program directors, participating faculty members, support staff such as tutors and counselors, and students must be willing at all times (Brinton & Snow, Citation2017; Kasper, Citation2000). Therefore, the adjunct model requires coordination among all these parts and ESL faculty. Organizing and managing such a program requires substantial time and energy for all parties to integrate the content materials with the language-teaching aims. Hence, it is not easy to do so. In other words, collaboration across disciplines is hard work and demands interdisciplinary programs that are difficult to sustain over long periods (Ghorbanchian & Karimi, Citation2022).

Furthermore, the instructional material of ACBI must include real-life experiences and contemporary issues from articles or magazines, and it must bear linguistic simplification to adopt text and promote comprehensibility (Stryker & Leaver, Citation1997). Therefore, considering all these things in the material for the ACBI course is challenging.

2.4. Adjunct content-based technical report writing

Technical writing is a form that can understandably elucidate complex concepts or procedures. Doing so demands researching and creating information about technical procedures and products. Teaching technical writing to EFL students is to help them communicate and, more precisely, share knowledge and technical information with others in a business or educational setting (Budinski, Citation2001). Therefore, it can be seen from two significant aspects: business and education.

From a business perspective, technical writing is viewed as a skill of written communication for and about business and industry. It focuses on productions and services concerning their manufacturing, marketing, management, delivery, and use. It is written to supervisors, colleagues, subordinates, sellers, and customers in the workplace (Budinski, Citation2001). On the other aspect, Students, teachers, researchers, and other specialists undertake technical writing in education to report educational research, current trends, concepts, or theories (Glasman Deal, Citation2010). Studies cited by Khonsari (Citation2005) indicate that many writing tasks assigned in university courses vary in academic level, field, and even within disciplines. These writing practices are often required to demonstrate knowledge and are used by instructors to promote independent thinking, researching, and learning. Especially in the academic fields, students often choose tasks that require primarily transactional or informative writing; rather than general writing

In this case, Budinski (Citation2001) points out that the major types of reports in technical writing can be grouped under technical papers, magazine articles, books, proposals, and theses for education. Thus, the technical writing demanded in education is broad, encompassing reports in science, engineering, and the skilled trades. Many university courses in the sciences, like engineering, use introduction, method, result and discussion (IMRaD) reports, which include an introduction, methods, results, and discussion for their instructional purpose.

Technical report writing plays an essential role in the student’s life, whether in college or the workplace. As Anderson and Keel (Citation2002) note, it is a valuable, lifelong skill that plays an essential role in achieving a variety of goals, such as writing a report or expressing an opinion with the support of evidence, extending and deepening students’ knowledge, and acting as a tool for learning subject matters. Thus, good report writing should begin with the process that enables students to develop and execute academic tasks, skills, and strategies to enhance technical communication skills.

Above all, technical report writing is a highly structured and specialized form of writing that requires a writer to develop an understandable, comprehensive, and readable report. This nature of writing requires the right approach to teaching.

With this respect, Ethiopian higher educational institutes have been incorporating various ESL/EFL course for freshman, graduate, and undergraduate students in different fields of study. In the case of Bahir Dar University, courses in written communication with economics students, technical report writing with technology students, English for Lawyers, English for Journalists, and other ESP writing courses for undergraduate students are offered (Dawit, Citation2014). Among them, technical report writing Skills is a type of technical writing which has been offering to engineer students as part of their technical skills in their field of study.

Even though Bahir Dar University undergraduate engineering students’ curriculum has been intended to prepare students to handle writing tasks across their disciplines, the technical report writing course curriculum has given less emphasis to the academic needs of the learners (Aklilu, Citation2015). According to MoE (Citation2018), engineering education in Ethiopia is also insufficiently geared toward developing employability and other lifelong learning skills. Therefore, the EFL instructions, which predominantly use a teacher-centered approach, focus on learning English for general purposes rather than ESP. Thus, the prevalence of a teacher-centered approach less emphasizes students’ writing task achievement, cohesion, coherence, lexical resources, and grammar range and accuracy. Disconnection between writing tasks and topics students are assigned to write reports on related to their field of study can be factors that impede their writing performance (MoE, Citation2018).

Research in the area indicates that the CBI approach positively contributes to learning academic subjects in English. D. Brinton et al. (Citation2003) case study on the evaluation of the ACBI program in the Freshman Summer Program (FSP) at the University of California, Los Angeles, confirmed that ACBI increases students’ motivation in learning the target language. Students reported that they felt they were better readers and writers due to the FSP using ACBI. On the other hand, Dalton-Puffer (Citation2011) indicates that CBI seems to have little or no effect on the dimensions that reach beyond the sentence level. Therefore, studies on CBI, in general, and ACBI, in particular, have a positive and negative impact on the EFL program, implying that further investigation is needed to provide supplementary practical results of using ACBI.

Thus, the study focused on effects of adjunct content-based instruction (ACBI) on students’ technical report writing performance. To this end, the study sought to address the following research questions:

What are effects of adjunct content-based instruction on students’ overall performance in technical report writing?

What are effects of adjunct content-based instruction on students’ performance in writing a technical report in terms of task achievement, cohesion and coherence, lexical resources, and grammar range and accuracy?

What are the views of students about learning EFL technical report writing via using ACBI?

3. Methodology

The study aimed to investigate effects of the adjunct content-based instruction model on EFL students’ technical report writing skills. It also employed a quasi-experimental design, which is imperative to avoid any situation whereby subjects self-selected themselves to be in the treatment group. The study used pre- and post-tests with comparisons and an experimental group design.

3.1. Participants

The study involved 64 fourth-year mechanical engineering students at Bahir Dar University which has been offering higher education in the field of engineering and technology in Ethiopia since 1963. Two sections of mechanical engineering students in the 2021/22 academic year were selected for this study. One was assigned to a comparison group (31 students), and another (33 students) was assigned to an experimental group. Both groups of participants have learned the English language as a subject since grade one and used English to study all other courses at high school and university. Since the participants were in the fourth-year batch, they had taken communicative English language skills and introductory writing skills courses at university. Moreover, the participants took a class on technical report writing skills and research methods during the study. The course aimed to equip them with the necessary skills in technical communication.

3.2. Data collection

Technical report writing tests and semi-structured interviews were employed to collect data for this study. A writing test is an instrument used to assess students’ technical report writing (Hyland, Citation2003). Hence, technical report writing pretests and posttests were administered in this study for both sections of students before and after the intervention.

The pretest was employed before adjunct content-based instruction (ACBI) intervention. It was given to students to assess their invariability and overall writing performance level before they were labeled as an experimental group and a comparison group. The test was given to students with a scenario to write an IMRaD report on “An assessment of personal factors that can impede auto mechanics repairing and maintaining activities of the automobile.”

Upon the completion of the experiment, technical report writing post-tests were administered to both the experimental group and comparison group to assess their final writing performance. Like the pretest, students were requested to write an IMRaD report on “an investigation of the S-4003 diesel engine crankshaft failure.”

In doing so, the pretest and post-test were marked using IELTS rubrics by two TEFL instructors who drowned on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages Writing Task 1-level writing assessment scale. The scale-modified scoring scales contain four components, each accompanied by five-point scale descriptors. These components helped to assess the task achievement, cohesion and coherence, lexical resource and grammar range, and accuracy of the students’ texts.

Since the writing test should be valid and reliable, the content and face validity of the pretest and posttest described above were checked. In doing so, the tests were given to PhD TEFL instructors, colleagues, and supervisors to check the appropriateness of the tests. The writing test was administered to students as soon as the comments and feedback were gained from professional judgments. Pearson’s correlations were applied to estimate the interpreter’s reliability and check the agreement between the two instructors who marked the tests. The obtained coefficient (r = .83) confirmed that the test was reliable.

The study also employed semi-structured interview to gather information about the participants’ views of using ACBI to teach technical report writing. According to Dornei (Citation2007), there is a set of pre-prepared guiding questions and prompt in semi-structured interview, but the format is open ended and the interviewee is encouraged to elaborate on certain issues raised in an examining manner. The interview was used to determine the effectiveness of using ACBI in technical report writing from the student’s perspective. For this purpose, three students were randomly chosen from the experimental group and interviewed to obtain the needed information.

The items for the interview were prepared based on the existing relevant literature and formulated in the manner in which they addressed the research questions. Then, they were given to EFL instructors and research supervisors for comments. After that, the interview was conducted in English.

3.3. Instructional context of the study

The instruction was linked to the two courses for fourth-year mechanical engineering students for eight weeks. Technical report writing skills was the EFL course taught by the EFL instructor, and the course on internal combustion (IC) engines was the content course taught by the content specialist. ACBI was provided to the experimental group during the intervention phase. The experimental group proceeded through sequential instructional steps centered on an adjunct content-based instruction model adapted from Chamot (Citation2005) and Percival (Citation1997). By combining these instructional models, the experimenter employed the following instructional contexts: preparation, presentation, planning to draft, writing, reviewing, and revising.

3.3.1. Preparation

The preparation stage for using ACBI began with preparing students for the program by reviewing their needs, goals, institutional expectations, available resources, teachers, and expected final performance outcomes. In doing so, the 2018 mechanical engineering curriculum was used at the time of the study to review and identify the preliminary considerations of using ACBI. Accordingly, the curriculum aimed to equip students with technical and communication skills. For this reason, students were registered to take six courses that semester. At the start of the courses, they were involved in selecting the course and course contents, which mainly required them to write reports. As a result, most of the students requested a course on IC engines and reciprocating machines, which deals with IC engine machine design and its principal work; besides that, the IC engine instructor was willing to join this ACBI program. The two courses, technical report writing skills, and IC Engine, targeted at the ACBI program, have three credit hours per week. Then, the EFL instructors assigned to teach technical report writing and research methods observed the content class to identify the writing tasks demanded by their course. Then the content instructor assigned to teach IC and the EFL instructor sat down together, determined their course objectives, and joined the writing tasks for both courses. The tasks were writing reports from sources of reading, lectures, references, IC engine lab practice, article analysis, two days of motors and engineering corporation (MOENCO) internship, graphical data, and collecting data. Eventually, content instructor decided on content while EFL instructor decided on language aspects to guide and prepare students for both courses.

3.3.2. Presentation

Following the preparation stage, the EFL and content instructors presented a general overview of technical report writing skills and the IC engine. They simultaneously correlated course contents with their objectives through videos and texts. While the content instructor introduced the content material, the ESL instructor emphasized previewing writing materials. The two instructors then created a conducive teaching and learning environment for students to work on the mutual tasks of writing reports to which they were assigned. Students were supposed to focus on the language and contents used to write the IMRaD description.

As Khonsari (Citation2005) note, the adjunct model of content-based writing instruction can be an effective means of presenting students with the opportunity to develop imperative skills because it deals with writing similarly to how it is assigned, prepared for, and reacted to in the entire academic course. The task of writing a technical report required students to restate or recast the information presented via lectures, readings, and discussions connected to the course contents. Then EFL instructors gave students the task of writing the IMRaD report on the following:

Constructing materials for the IC engine machine,

Working principles of four- and two-stroke engine systems,

IC Engine Lab 1 practice,

Analyzing articles on the IC engine machine

Two days of internship practice in MOECO at Bahir Dar town

Analyzing graphical data

Collecting and reporting data on an IC engine machine

In the presentation stage, students acquainted themselves with the above writing tasks to learn technical report writing skills and study IC engines and reciprocating materials. The writing in this phase was categorized as a pre-writing stage in which the instructors’ familiarized students with the content, language, and study skills that can pave the way to developing an IMRaD report.

3.3.3. Planning

Based on the information acquired from the preparation and presentation stages, students were supposed to plan to write the IMRaD report. This stage aimed to activate the students’ schema and interest in the subject matter of the writing task by creating a connection to the experience they acquired from the earlier stages. The planning stage involved clarifying terms of reference, gathering information, organizing information, deciding on presentation styles, and making an outline.

Regarding writing, teachers and students aimed to clarify and define the four major tasks: establish the primary purpose, assess the targeted audience or readers, and understand the context. Accordingly, the instructor asked students simply what they wanted their readers to know, believe, or be able to do after they finished reading the report. In addition, students were made to consider their readers’ prior knowledge about the subject and the circumstances under which writers produced reports. The purposes achieved through each session or writing task were planned. In clarifying terms of reference, the writing instructor gave students the scope to decide what to include and not include in their writing.

Students also planned to gather information for each task of writing. In this stage, students sought adequate information and were required to decide on two things: the method of gathering information and the source. The instructor got students to use data-gathering tools. They also used sources of information like a lecture of content material, reading references, workshops on the campus, MOECO in Bahir Dar town, their peers, lab assistants, their instructors, and themselves. Generally, all these aspects of gathering information were intended at this stage.

Without organization, the material gathered during their research would be incoherent to their readers. To do so, they needed to determine the best way to structure their ideas; that is, they had chosen a primary method of development: sequential, chronological, or cause-and-effect, general to specific or vice versa. Since the writing was an IMRaD report, students intended to use the sequence of introduction, process, result, and discussion, which can fit the convention of report writing.

Deciding on presentation styles is another aspect of planning to write the report. Instructors in this stage got students to use appropriate language and format. This was because students decided to use the essential aspects of technical language to be considered in writing the report. The structure of sentences, tenses with passive/active voice, vocabulary, punctuation, and referencing style were decided in each session of writing the report.

The final stage of planning was outlining. Once students had chosen a development method, they were ready to prepare an outline. By structuring their thinking early, outlines were completed by allowing students to focus exclusively on writing before they began the rough draft. An outline can be beneficial for maintaining a collaborative writing team’s focus throughout a report. Hence, students were supposed to prepare a cooperative outline plan for each task of writing an introduction before practicing writing. As Alred et al. (Citation2009) explain, outlining breaks large or complex subjects into manageable parts. It also enables students to emphasize critical points by placing them in the order of their most significant importance.

Overall, the tasks in the above stages were performed in the pre-writing stages of writing the IMRaD report. In each step and sub-stage, careful preparation and execution of the plan are needed. Khonsari (Citation2005) substantiates that content-based technical report writing instruction requires students to restate and recast data and ideas from readings, lectures, and discussions on a topic and possibly report on the outcomes of independent or group research on related subjects. Thus, planning, as part of the pre-writing stage, created opportunities for students to use their prior knowledge to deal with the content and language of task achievement, cohesion, coherence, lexical resources, and grammar accuracy to write an IMRaD report.

Students were well-prepared to produce the report’s first draft after finishing the preparation phase. In every exercise of the program, they were instructed to develop their outline into paragraphs without worrying about grammar, usage changes, or punctuation. Regarding this, Khonsari (Citation2005) claimed that writing duties involve producing initial drafts under the same or similar conditions as those addressed by confronting assignments for topic courses in content-based approaches to developing technical reports. In this way, students structured and improved their writing processes and used their understanding of the standards of technical report writing to create a writing draft. In this phase, students worked on using cohesion and coherence, lexical resources, grammar variety, and other strategies to accomplish the task’s communicative goal.

3.3.4. Reviewing and revising

Reviewing and revision was the stage in which the instructor let students review and rewrite the second or final version of their writing by incorporating all necessary comments from their peers and instructor and beginning to write the report in an organized way. Self and peer review were applied to evaluate their first draft. This revision session required students’ introduction writing skills by including task achievement, coherence and cohesion, lexical resources, grammatical range, and technical accuracy in report writing tasks. This last step was categorized as part of the post-writing stage. Therefore, in this step, the instructors’ comments could create opportunities for students to confidently write the revised version of the writing by incorporating comments.

The experimental group passed through the pre-writing, writing, and post-writing stages while practicing the adjunct content-based instruction model. This instructional approach was not only demanding cautious preparation and execution of the plan in the writing and post-writing stage but also required EFL and content instructors’ commitment in each stage of writing tasks.

On the other hand, the control group was taught using the conventional approach. The above steps employed in the experimental group were not used in the control group. Hence, the instructional process of the control group was tracked as follows: first, the instructors provided the students with sources of information like texts, lectures, and the like. Students then attended to the sources of information relating to their content material and discussed them in pairs. Finally, instructors let them write IMRaD reports.

4. Data analyses

The study intended to investigate effects of using ACBI on students’ technical report writing performance. It employed a one-way multivariate analysis of variance (one-way MANOVA) on SPSS version 25.0. This is because one-way MANOVA computed both overall and discrete differences. Both multivariate and univariate comparisons were made between the control group and the experimental group in terms of their mean scores of the four dependent variables: task achievement (TA), cohesion and coherence (CC), lexical resource (LR), and grammatical range and accuracy (GRA).

The study also employed thematic analysis to analyze qualitative data obtained through interviews. Thus, the analysis involved effects of ACBI using both quantitative and thematic qualitative methods.

5. Results

The data were collected through writing tests and semi-structured interviews in order to address effects of ACBI on students’ overall technical report writing performance, effects of ACBI on students’ technical report writing skills, and students’ view about using ACBI in technical report writing instruction.

5.1. Effects of ACBI on students’ overall technical report writing performance

The study employed Pre-intervention one-way MANOVA tests in order to compute the results of the control and experimental groups before they were assigned as experimental and control groups. For this purpose, descriptive statistics and multivariate test results are presented in Table .

Table 1. Pre-intervention one-way MANOVA statistics and Multivariate tests

TRW=Technical report writing, TA= task achievement, CC=cohesion & coherence, LR=lexical resource, GRA= grammar range & accuracy.

a. Design:Intercept + Group,

Exact statistic,

Computed using alpha =.05

Table illustrates the mean and multivariate tests comparison between the two groups in the pre-intervention phase. The Table indicates that the control group and experimental group scored (M = 2.18 with SD = 0.50, and M = 2.29 with SD = 0.45) on their TA respectively. The mean scores of the two groups were nearly similar to each other. The scores of the control group and the experimental group on CC were (M = 2.06 with SD = 0.51, and M = 1.95) with SD = 0. .47) respectively. Hence, the scores of the two groups were near to similar with respect to CC.

Table also indicates that the scores (M = 1.98 with SD = 0.38 and (M = 1.88 with SD = 0.42) were the control group and experimental group participants’ achievement on LR respectively. Therefore, there was a slight difference between the control group and experimental group participants’ scores. Moreover, the mean score of the control group (M = 2.31) is close to the mean score of the experimental group (M = 2.28) in terms of GRA. Thus, there were almost similar scores between the control and experimental group participants in their pre-intervention technical report writing performance.

Moreover, the multivariate test result in Table above shows that there was insignificant difference between the two groups’ overall technical report writing performance. This was because the Wilks’ Lambda statistic revealed the following results: Wilk’s Lambda λ =.897, F (4, 59) = 1.691b, p = 0.164, η2 =. 0.103. According to the result in Table , the groups were homogenous in terms of multivariate variance (P > 0.05).

One-way MANOVA was also used to compare the differences between groups in the post-test intervention. Based on this, the overall impacts of ACBI on students’ TA, CC. LR, and GRA of technical report writing were checked. In doing so, the descriptive statistics and multivariate tests are presented in Table .

Table 2. Post-intervention one-way MANOVA statistics and Multivariate test

TRW=technical report writing. TA=Task Achievement, CC= cohesion and coherence, LR= lexical resource, GRA= grammatical resource, and accuracy.

a. Design:Intercept + Group,

Exact statistic,

they were computed using alpha =.05.

Table reveals the descriptive statistics between the control and experimental groups’ technical report writing performances regarding TA, CC, LR, and GRA. The control and experimental groups’ mean and standard deviation scores for TA were (M = 2.419, SD = 0.4301, and M = 3.00, SD = 5731) respectively. Hence, the experimental group’s mean score (M = 3.00) was higher than the control group’s mean score (M = 2.419) in TA. Thus, there was a difference between the control and experimental groups’ writing TA after the experimentation.

Regarding with CC, the means of the control and experimental groups were (M = 2.097, SD =.3746, and M = 2.606, SD=.6093) respectively. Therefore, there was a variance between the control and experimental group scores in writing CC. Thus, experimental group participants had improved cohesion and coherence of writing report over that of control group cohesion and coherence of writing report in the post-intervention phase. Furthermore, the post-intervention results associated with LR (M = 2.145 with SD =.4122) was the mean and standard deviation of the control group, while (M = 2.561 with SD =.5414) was the mean and standard deviation of the experimental group. Hence, the experimental group scored higher than that of the control group after the intervention of using ACBI. This result means that students in the experimental group were better lexical users than the students in the control group. In the post-intervention, the experimental group’s GRA (M = 2.939, SD = 0.5414) was better than the control group’s GRA score (M = 2.468, SD = 0.3637). Thus, the experimental group scored higher than those in the control group of GRA in the post-intervention writing.

To see whether the overall score between groups was significant, multivariate difference was examined. Accordingly, the multivariate differences between the experimental group and control group was significant, with Wilks’s λ = 0.730, F (4, 59) = 5.453b, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.270. The result revealed that ACBI brought about a significant multivariate change between the control and experimental group participants’ writing performance in the post-intervention phase. The effect size η2 = 0.270 is too large. This mean to that the effect size of ACBI on the overall performance of writing was 27%.

Above all, collected data using writing tests before the intervention of using ACBI showed that the two groups were virtually similar in their overall performance of technical report writing before the intervention. On the other hand, the result indicates that the multivariate difference between groups was statistically insignificant at the onset of pre-intervention phase. Contrasting to the pre-intervention results, experimental group participants who were involved in using ACBI brought changes on the overall performance in technical report writing after the intervention of using ACBI. Results of Multivariate test revealed that there were statistically significant differences between groups in their technical report writing skills favoring to the experimental group. This was the combined result of the four variables, but it does not indicate the individual results of the four dependent variables separately. Therefore, the univariate differences across each component of the dependent variable are provided in the subsequent section.

5.2. Effects of ACBI on students’ technical report writing skills

Pre-intervention one-way MANOVA Univariate analysis was employed in order to compare the two groups’ technical report writing performance before they were assigned as experimental and control groups. The results are presented in Table .

Table 3. Pre-intervention univariate tests results

R Squared =.014 (Adjusted R Squared = −.002),

R Squared =.011 (Adjusted R Squared = −.005),

R Squared =.018 (Adjusted R Squared =.002),

R Squared =.022 (Adjusted R Squared =.006),

Computed using alpha =.05

As shown in Table , one-way MANOVA was applied to compare the two group results on TA, CC, LR, and GRA discretely. Accordingly, the results of univariate analyses of variance revealed insignificant differences between subject effects on each component of writing skills in the pre-intervention phase.

The univariate differences between the two groups were found as follows: TA (F (1, 62) = 0.877, p = 0.353, η2 = 0.014; CC (F (1, F (1, 62) = 0.666, p = 0.418, η2 = 0.011; LR, (F (1, 62) = 1.122, p = 0.294, η2 = 0.018; GRA (F (162) = 1.369, p = 0.247, η2 = 0.022). As seen in this result, the significant level of each component was above 0.05 (P > 0.05). This implies that there were no significant differences between the control and experimental group participants writing performance on TA, CC, LA, and GRA at the onset of pre-intervention phase. Thus, the assumption that the two groups were homogeneous in their writing report in terms of TA, CC, LR, and GRA remained the same before the intervention.

Post-intervention tests were also used to compute control group and experimental group technical report writing performance with respect to TA, CC, LR, and GRA separately. So univariate analyses of variance (Tests of Between-Subjects Effects) is provided in Table

Table 4. Post-intervention univariate comparison

• TA= task achievement, CC=cohesion & coherence, LR=lexical resource, GRA=grammar range &accuracy R Squared =.212 (Adjusted R Squared =.199). R Squared =.205 (Adjusted R Squared =.192), R Squared =.160 (Adjusted R Squared =.147), R Squared =.210 (Adjusted R Squared =.198), Computed using alpha =.05.

The univariate test results in Table above were used to examine the effects of ACBI on students’ technical report writing relating to TA, CC, LR, and GRA discretely. Accordingly, the univariate differences of TA, CC, LR, and GRA in the control and experimental groups were dissimilar in the post-intervention phase. Regarding the four dependent variables of writing a technical report, the univariate mean differences between the control and experimental groups were significant. The results were obtained as follows: TA (F (1, 62 = 16.666, P = 0.000, η2 = 0.212), CC (F (1, 62) = 15.977, P = 0. 000, η2 = 0.205), LR (F (1, 62) = 11.816, P = 0.000, η2 = 0.160) and GRA (F (1, 62) = 16.518, P = 0.000, η2 = 0.210). The significant level of each dependent variable is below 0.05 (P < 0.05). As a result, the univariate test results were significantly different between the two groups. When comparing the impact of using ACBI on each component of writing, TA, GRA, CC, and LR were (η2 = 21.2%), (η2 = 21%), (η2 = 20%) and (η2 = 16%) respectively. Therefore, the effect size of ACBI on students’ technical report writing about the four skills ranged from LR (η2 = 16%) to TA (η2 = 21.2 %). Thus, the largest effect size existed with TA. Following TA, the effect size of using ACBI on GRA and CC too large respectively after the intervention of ACBI.

Thus, tests between subjects-effects were comparable in terms of TA, CC, LR and GRA. The groups were homogenous in their technical report writing skills with respect to TA, CC, LR, anGRA (p > .05) at the on-set of pre-intervention phase. On the other hand, results of Univariate tests also showed that there were statistically significant differences between experimental and control groups in technical report writing skills in terms of TA, CC, LR and GRA. Thus, the participants who were involved in experimental group improved their writing skills regarding to the four writing traits.

5.3. Students’ view about using ACBI in technical report writing instruction

Upon completing the intervention using ACBI, a semi-structured interview was conducted with three randomly selected students from the experimental groups. It aimed to obtain information about students’ views using ACBI in their technical report writing instruction. So, interviewees were asked if there were differences between the ACBI and the former one EFL instruction. Hence, all of them agree that the two instructional approach were unlike. In this case S1 states as:

There were differences between using ACBI in technical report writing and former EFL/ESL instruction. ACBI was making easy to write the report assigned by two instructors. Contents I assigned to write were related to my major course subject matter, so I had had opportunities to use references from my classmate, internet and library. The assignments were submitted to the two instructors. They were IC engine instructor and technical report writing instructor. However, the former EFL instructional approach didn’t have opportunity to write about topics related to my academic subject. I submitted the assignments to one instructor.

Thus, students have recognized the differences between using ACBI and former EFL instructional approach. They believe that their non-CBI which the former instruction was not integrate the content and language learning.

The interviewees were also asked if they liked using ACBI in their technical report writing instruction. Accordingly, S1 also stats as:

Yes, using ACBI in learning technical report writing was attractive. It helped a lot as it was a practical way of understanding the subject matter I have had studied. I needed little effort to report what was done in my task. In this case, I improved my academic and future professional skills of writing TA, CC, LR, and GRA as effectively and efficiently as possible.

According to the responses of the interviewee, students who enrolled in the experimental group liked using ACBI in learning technical report writing.

Students also explained that learning through ACBI had many benefits for their academic careers. For example, S2 says as:

I gained so many benefits from learning to write technical reports using ACBI. It improved my academic success and the quality of writing content for my course assignments from various sources. I learned and used more words and phrases in technical reports writing introduction, method, result, and discussion than before the intervention. I also learned to organize and punctuate good writing of my future final-year projects and apprenticeship reports.

In this view, D. Brinton et al. (Citation2003) state that students who were treated using ACBI felt to improve their study skills. They became more confident in their ability to read and write report. The students were also asked if ACBI helped them to improve their writing strategies. Accordingly, all of them have positive views about the importance of ACBI in enhancing their writing strategy use. Concerning this, the third student (S3) says:

As stated in the question, ACBI improved using writing strategies like collecting information from peers, reading references, attending lectures from the instructors, IC engine workshops, and MOECO at Bahir Dar town. And then, organizing, presenting, reasoning, and analyzing the information obtained from the source were practiced in technical report writing class. Finally, we reviewed our draft in groups and developed a well-organized report to be submitted to technical report writing and IC. Engine instructors.

Thus, the data from interviewees on their views about using ACBI indicated that ACBI improved not only their writing report assignments for the course of technical report writing skills and research methods, it also enhanced their skills in their practical academic tasks, writing projects, apprenticeships, and professional practice as effectively as possible. Students believed that they could transfer skills and knowledge acquired through ACBI to their field of studies and actual life practice. Speaking, reading, writing, and academic study skills were integrated while collecting, organizing, justifying, analyzing, and reviewing sources and drafts of writing reports.

The finding of the study also indicated that EFL students who were engaged in the experimental group had positive views about using ACBI in learning technical report writing and research methodology course. They believed that ACBI improved their’ technical report writing skills, IC engine course content knowledge, and their academic and professional skills in their field of study. They also view that ACBI acquainted themselves with their study skills and learning strategies.

6. Discussion

Systematic collaboration between the content and EFL/ESL instructors in Ethiopia post-secondary education has been ignored in ELT instruction. It is believed that this situation has affected students’ technical report writing skills. They failed to develop structured introduction, method, result, discussion and conclusion of their written assignments. In this case, the study intended to investigate the effects of ACBI on EFL students’ overall technical reports writing performance. It also aimed to examine if ACBI brought significant changes on EFL students’ technical report writing skills. Upon analyzing the data obtained from the technical report writing test and comparing outcomes of the control and experimental groups, it was found that using adjunct model of CBI improved EFL students overall and separate skills of technical report writing. In this context, ACBI was pedagogically considered the right option for teaching technical report writing and research methodology courses because it produced meaningful features.

The findings of this study are consistent with the results of the study undertaken by Ghorbanchian and Karimi (Citation2022). Accordingly, their study was intended to investigate the efficacy of the adjunct model in improving the overall reading comprehension of Iranian architecture students in EAP courses. Their findings revealed that EFL students in the adjunct class outperformed their peers in the other two classes who engaged in a theme-based and sheltered model of content-based instruction on reading and writing achievements. Hence, the current study which was intended to examine effects of ACBI on students’ technical report writing performance is positively correlated to Ghorbanchian and Karimi (Citation2022) studies which focused on efficacy of the adjunct model in improving the overall reading writing achievements of Iranian architecture students in EAP courses.

The results found in this study also coincide with findings in Douglas (Citation2017), Dalton-Puffer (Citation2011), Phonlabutra (Citation2007), Khonsari (Citation2005), and Percival (Citation1997). According to Douglas (Citation2017), students involved in CBI with different language ability levels gained content knowledge uniformly and attained linguistic ability and quality of writing skills in varied ways. In this result, CBI has increased oral and written language development and sub-skill areas of language competence such as vocabulary, morph syntax, discourse, pragmatic language use, and learning strategies. Therefore, the study undertaken by Douglas (Citation2017) is definitely associated with the findings of this study.

The outcome obtained through this study also agrees with Khonsari’s (Citation2005) conclusion, for the results of students who use a content-based approach to learn writing skills are pretty satisfactory. These students had a better vocabulary, grammar, reading comprehension, and writing compared to the students involved in non-CBI. Their scores in their content course were also higher than the scores of the students in the non-CBI course. This study was also substantiated by scholars like Celce Murcia (Citation2001) and Beckett et al. (Citation2004). They indicate that most participants consider ACBI methods as an effective pedagogical technique to acquire writing skills and content knowledge.

Similarly, D. Brinton et al. (Citation2003) found that the students, teachers, and parents perceive that the ACBI contributes to high English language proficiency, self-confidence in communicating in English, and academic achievement. Issues such as English curriculum, content, and language accuracy are also addressed. A comparative study of CBI also found that an experimental group required to reconstruct aural texts showed better comprehension of aural texts and evidence of past tense development in their writing in their post-test (Kasper, Citation2000). Thus, the current study is related to Kasper (Citation2000) and D. Brinton et al. (Citation2003) reports that ACBI could improve GRA and writing proficiency.

Overall, this research indicated that mechanical engineering students involved with ACBI improved their skills in technical report writing, which is assigned to do frequently in their field of study. According to Beckett et al. (Citation2004) the ACBI course enrolls EFL students for praise in a subject matter content course and an associated EFL course in which the content material is reviewed and the academic skills and background knowledge necessary for success in the study are taught. The purpose of this course is to help students master the subject matter content material, introduce them to English academic discourse, and develop skills that they can transfer to other academic areas (Beckett et al., Citation2004). Likewise, the adjunct course that was concurrent with the I.C. engine course and EFL technical report writing skills courses in this study, helped students to have positive views on their academic and practical skills. This study showed that students engaged in ACBI significantly outperformed those who used the conventional approach. Therefore, it is suggested that ACBI can be successfully implemented in EFL contexts, but careful consideration, planning and execution are required.

However, the findings of this study contradicted some studies like Villalobos(Citation2013) Valeo (Citation2013) employed a quasi-experimental, comparative research method. Accordingly, the study found that form-focused instruction significantly contributed to substantial gains in two grammatical forms, the present conditional and the simple past tense, and content knowledge among the learners in an adult ESL/EFL CBI. Therefore the findings of this study negatively correlated to results obtained by Valeo (Citation2013).

Thus, the present study focused on effects of content-based adjunct instruction with limited mechanical engineering student participants in Ethiopia. It can be undertaken comprehensively with a large sample and participants in various contexts to verify its consistency. This is because collaborative instruction in adjunct model demands managing coordinated labors of the two separate course instructors.

7. Conclusion

ACBI is one of the areas in which researchers’ interest has been growing. This study focused on effects of ACBI on EFL students’ technical report writing performance. It employed a quasi-experimental design to find out effects of adjunct model instruction on the student’s technical report writing skills. It was also intended to examine Students’ views about using ACBI in learning technical report writing and research methodology course. Based on the results and discussion. The study concluded that ACBI brought statistically significant change in the overall and results of technical report writing skills, favoring the experimental group.

The findings also proved that ACBI yield statistically significant improvement in technical report writing skills concerning with TA, CC, LR, and GRA discretely. On the other hand, Students who were involved in ACBI develop well accurate resourceful and sound inter and intra-structured technical report writings which could be an account of their academic task over students who engaged in non-ACBI. This study also proved that those students who were engaged in ACBI had positive perception about learning technical report writing. Thus, it can be concluded that ACBI positively impacted on EFL students’ technical report writing performance.

These findings imply that collaborative teaching played a significant role in EFL acquisition by providing students with comprehensible input and output. The ACBI program can create a smooth relationship, socialization, and cooperation between the EFL and engineering faculty. Moreover, this program could meet students’ technical communication needs in their specific academic and field of profession.

The pedagogical implications from this study are anticipated to be feasible to teachers, researchers, and educators involved in writing English for academic purposes, particularly to those concerned with the teaching of technical report writing skills and preparing students to further college and university academic courses. Researchers may also find the outcome of this study substantial to undertake further research. Moreover, syllabus developers find it to use the ideal choice for planning and preparing for English for technical communication courses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Assefa Chekol

Assefa Chekol is a lecturer and PhD candidate at Bahir Dar University. He is interested in studying Collaborative learning, content-based instruction, and adjunct model instruction in particular on students’ technical writing skills, and learning strategy use.

Kassie Shiferie

Dr. Kassie Shifere (Associate Professor) He was awarded BA and MA in Linguistics and TEFL, respectively, from Addis Ababa University and Ph.D. from Andhra University, India. His research interests include classroom research, inclusive education, teacher education, and continuous professional development. Currently, he is engaged in teaching ELT courses in Graduate Program, advising graduate students, and training academic staff in the Higher Diploma Program.

Seyoum Teshome

Dr. Seyoum Teshome is an instructor and assistant professor at Bahirr Dar University in the Department of English Language and Literature. He has been advising students in the post graduate program. He has also a keen interest in studying language learning strategy, learning styles, learners’ autonomy and foreign language anxiety.

References

- Aklilu, G. (2015). An Investigation of the present situation communicative needs in an ESL Context. Civil Engineering Students in Focus: English for Specific Purposes World. ISSN, 16(48), 1682–22. www.esp-world.info

- Alred, G. J., Brusaw, C. T., & Oliu, W. E. (2009). The Handbook of Technical Writing (9th ed.). St. Martin’s Press.

- Anderson, D. M., & Keel, M. C. (2002). Using reasoning and writing to teach writing skills to Students with learning disabilities and behavioral disorders. Journal of Direct Instruction, 2(1), 49–55.

- Angelil, C. S. (1994). The adjunct model of content-based language learning. South African Journal of Higher Education, 8(2), 9–14.

- Beckett, G. H., Gonzalez, V., & Schwartz, H. (2004). Content-Based ESL Writing Curriculum: A Language Socialization Model. NABE Journal of Research and Practice, 2(1), 161–175.

- Brinton, D. M., & Snow, M. A. (2017). The Evolving Architecture of Content-Based Instruction: The Content-Based Classroom (2nd ed.). University of Michigan.

- Brinton, D., Snow, M., & Wesche, M. (2003). Content-based second language instruction. The University of Michigan Press.

- Budinski, K. G. (2001). Engineers’ Guide to Technical Writing. United States of America: ASM International.

- Carrio-Pastor, L. M. (2009). Content and language integrated learning: Cultural diversity. Peter Lang.

- Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Language teaching methodology (3rd ed). Prentice Hall.

- Chamot, A. U. (2005). Language learning strategy instruction: Applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 25, 112–130.

- Dalton-Puffer, C. (2011). Content-based instruction: A relevant Approach of Language Teaching.Annoul review of Applied linguistics. Oxford University.

- Dalton-Puffer, C. (2011). Discourse in content and language integrated learning classroom. John Benjamins.

- Dawit, A. (2014). Applying the process-genre approach to written business communication skills in English ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Bahir Dar University.

- Dornei, Z. (2007). Research Method in Applied Linguistics: Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Method. Oxford University.

- Douglas, M. O. (2017). Assessing the Effectiveness of Content-Based Language Instruction (CBLI. Japanese at the College Advanced Level: American Association of Teachers of Japanese, 51(2), 199–241.

- Duenas, M. (2004). The Whats, Whys, Hows and Whos of Content-Based Instruction in Second/Foreign Language Education. International Journal of English Studies, 4(l), 73–96.

- Ghorbanchian, E., & Karimi, M. Effects of Adjunct Model of Instruction on EAP Learners’ Reading Comprehension Skill. (2022). Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition, 8(2), 1–20. 2022.

- Glasman Deal, H. (2010). Scientific Research Writing for Non-native Speaker of English. Imperial College.

- Hyland, K. (2003). Second Language Writing. Cambridge University.

- Hyland, K. (2007). English for specific purpose: Some Influences and Impacts. The University of London.

- Hyland, K. (2013). Handbook of English for Specific Purposes. (2013). Blackwell.

- Hyland, K. (2014). English for Academic Purposes. In C. Leung & B. Street (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to English Studies (pp. 16). Routledge.

- Kasper, L. F. (2000). The Impact of Content-Based Instructional Programs on the Academic Progress of ESL Students. English for Specific Purposes, 16(4), 309–320.

- Khonsari, S. (2005). Approaches to Content-Based Academic Writing. Journal of ASIA TEFL, 2(2), 117–137.

- Kinsey, M. E. (2008). The adjunct model of language instruction: guide lines for implementation in the English for academic purpose program ( MA thesis). Indiana University.

- MOE. (2018). Ethiopia Federal and Democratic republic Ministry of Education: Ethiopia Educational training Roadmap preparation Study. Addis Ababa.

- Percival, G. S. (1997). The Adjunct Model of Content-based Instruction: A Comparative Study in Higher Education in. Portland University.

- Phonlabutra, K. (2007). Learning content-based program in a junior-high school in Thailand: A case study. The University of Arizona. http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194337

- Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2001). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Snow, M. A. (2001). Content-based and immersion models for second and foreign language teaching. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign l language (3rd ed., pp. 303–318). Heinle & Heinle.

- Stryker, S., & Leaver, B. L. (Eds.). (1997). Content-Based Instruction in Foreign Language Education. Georgetown University Press.

- Troncale. (2002). Content-Based Instruction, Cooperative Learning, and CALP Instruction: Addressing the Whole Education of 7-12 ESL Students. Columbia University. Teachers College.

- Valeo, A. (2013). the integration of language and Content: Form focused instruction in content-based language program.The. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: Oxford University, 16(1), 25–50.

- Villalobos, O. B. (2013). Content-Based Instruction: A Relevant Approach of Language Teaching. NOVACIONES EDUCATIVAS ·, 15(20), 20.

- Williams, M., & Burden, R. L. (1997). Psychology for language teachers: A social constructivist approach. Cambridge University Press.

Appendix

What differences have you recognized between the ACBI and the former one?/Can you describe how you have been learning TRW for the last time?

Do you like using ACBI in technical report writing instruction? How and why?

Is there any difference in your writing performance before and after you learned TRW using ACBI?/Do you think that the way you have been learning TRW for the last time brings about any difference in your TRW performance compared to the former one?

What are the benefits of using ACBI for studying your academic content course success

Do you believe that using ACBI can help you to improve technical report writing strategy use?

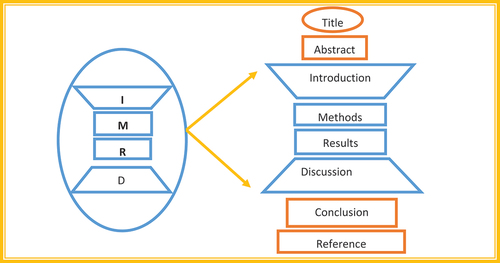

Caption: Structure of the IMRaD report (Glassman-Deal, 2010)

Figure above illustrates that an IMRaD report structure placed in the circle is a genre of technical report writing provided on the left side of the figure. It is presented to give the readers a clear image of the report structure students were assigned to write in the study. The structure of the IMRaD report includes an introduction, method, result, and discussion. It excludes some front matter and back matter elements revealed on the top and bottom of technical report writing. Therefore, the study focused on technical report writing in terms of the IMRaD report.