Abstract

The concept of interdisciplinarity has been the focus of much reflection, but studies on the implementation of interdisciplinarity in secondary schools remain rare. This literature review aims to provide a state of the art empirical studies of interdisciplinarity in secondary schools. This systematic review, based on PRISMA standards, includes a descriptive analysis and a thematic analysis using inductive and deductive methods. Studies were identified using the following databases, Web of Science (WOS), Taylor & Francis (T&F), ERIC, and Science Direct (SD). A total of 40 studies were selected and analyzed to (1) provide an overview of interdisciplinary practices in secondary schools, (2) highlight the effects of interdisciplinary practices on teachers and students, and (3) identify the conditions that favor the construction of interdisciplinary sequences. The results of this review show that few interdisciplinary practices are used in secondary schools and that even fewer achieve a real integration of disciplines. Interdisciplinary approaches seem to have positive effects on both students and teachers (promoting learning and, interest, developing interpersonal skills and encouraging professional development) when it is possible to overcome the many obstacles they face and to implement them in favorable conditions, such as those featuring a strong conceptual link between disciplines or complementarity between disciplinary and interdisciplinary moments.

Societies in the 21st century will face major challenges in the near future. The skills that are necessaryfor the development and integration of our youth in a changing and demanding world are based on complex and global understandings. Interdisciplinarity, which is often used as an umbrella term to represent all forms from of interdisciplinarity ranging multidisciplinarity to transdisciplinarity, is an encouraging approach to the development of values and skills such as creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and communication (McPhail, Citation2018). These skills are not always addressed in traditional education but are specifically necessary for the world of tomorrow. However, interdisciplinarity seems to be far from a common practice in schools, and the form that interdisciplinarity takes remains experimental. According to Darbellay (Citation2019), in Switzerland, cross-curricular skills (which, according to future teachers, should be a current priority) are only marginally integrated into teaching. Interdisciplinarity has been theorized extensively, and several taxonomies of quality interdisciplinarity have been produced (e.g., Klein, Citation2010). Theoretical knowledge in this domain is abundant, but in the context of their implementation, interdisciplinary approaches have difficulty gaining traction despite their supposed benefits. The aims of this literature review are to (1) establish a state of art of studies focusing on interdisciplinary experiences in school, (2) highlight the identified effects on students and teachers, and (3) identify the conditions that favor the construction of interdisciplinary teaching sequences.

2. School interdisciplinarity

Due to the large number of different interpretations of the word “interdisciplinarity”, a clarification of the terms is necessary. Throughout the text, the term interdisciplinarity is used generically to represent the whole interdisciplinary continuum. However, when clarification is necessary regarding on the degree of integration, the terms multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity are used in accordance with the definitions proposed by Klein (Citation1990). More precisely, Choi and Pak (Citation2006) (according to Klein, Citation1990) defined multidisciplinarity as “a process for providing a juxtaposition of disciplines that is additive, not integrative”, interdisciplinarity as “a synthesis of two or more disciplines [that] establishes a new level of discourse and integration of knowledge”, and transdisciplinarity as an approach that “provides holistic schemes that subordinate discipline, looking at the dynamics of whole systems” (Choi & Pak, Citation2006, p. 355). To provide guidance to the reader and facilitate reading, the term interdisciplinarity is used in this article in accordance with the definition provided by Klein (Citation1990).

In the context of this article, it is also important to define the terms school interdisciplinarity and academic interdisciplinarity clearly. According to Lenoir and Sauvé (Citation1998),

[…] school interdisciplinarity uses knowledge in an educational perspective; it aims to train social actors by creating the most appropriate conditions to encourage and support the development of integrative processes and the appropriation of knowledge as a cognitive product by students, which requires an adjustment of school knowledge at the curricular, didactic and pedagogical levels (p.111) (translated from French by the author).Footnote1

The main objective of academic interdisciplinarity is the production of new knowledge (Schulert et al., Citation1994). In this review, when we speak of interdisciplinarity, we refer only to school interdisciplinarity.

In the context of school interdisciplinarity, a variety of terms have been used to represent the intersection of several disciplines. The term “curriculum integration”, which was defined by Beane (Citation1997) as an approach that “promotes personal and social integration through the organization of curriculum around significant problems and issues, collaboratively identified by educators and young people, without regard for subject area lines” (p. xi), has been used frequently. In this article, we use the terms school interdisciplinarity and curriculum integration interchangeably, in line with Hasni et al. (Citation2015, p. 153), who noted that the concept of “interdisciplinarity” is “[…] strongly associated with the concept of integration, and the two concepts are sometimes used interchangeably”. This idea was also endorsed by McPhail (Citation2018, p. 57): “Bringing various subjects together in teaching and learning is known by a variety of names (interdisciplinarity, intersubject, cross-disciplinarity, cross-curricular, integrated inquiring teaching, curriculum integration) […]” (p. 57).

3. The quality of interdisciplinary practices

As noted by Boix-Mansilla and Duraising (Citation2007), it is difficult to define “the indicators of quality interdisciplinary work because interdisciplinarity is an elusive concept” (p.218).

In schools, some principles can be followed by teachers to promote and support the implementation of interdisciplinary approaches. Lenoir and Hasni (Citation2016) proposed six foundational principles that characterize quality school interdisciplinarity: (1) interdisciplinarity cannot exist without disciplines; (2) interdisciplinarity is not an accumulation of different disciplinary perspectives; (3) “interdisciplinarity in education belongs to the means, rather than the ends” (p. 2449); (4) there are no hierarchical relations among disciplines, which are treated equally; (5) three different interdisciplinary perspectives (logics) were highlighted by the authors, and “[…] these three logics of meaning, functionality and affectivity are complementary and should be interwoven when using interdisciplinary approach in teaching practices” (p. 2450); and (6) collaboration among teachers is mandatory in an interdisciplinary approach. Lenoir and Hasni (Citation2016) also developed a model that defines interdisciplinary teaching practices and their four derivatives (pseudointerdisciplinarity, hegemony, holism and eclectism) more precisely. Boix-Mansilla and Duraising (Citation2007) developed an assessment framework for evaluating students’ work that included the following three dimensions. (1) Disciplinary grounding: understanding the concept and methods of disciplines is mandatory to be able to create links among disciplines. Moreover, such an understanding protects against poor interdisciplinary projects. (2) Advancement through integration: all interdisciplinary projects should aim to advance students’ understanding. (3) Critical awareness: it is important to assess the advancement of students, but students should also be assessed in terms of their ability to reflect on the purpose, means and limits of their work. Boix-Mansilla and Duraising’s (Citation2007) first two points seem to be very similar and complementary to Lenoir’s first three points. However, the former author sheds additional light on the importance of putting students in a situation in which they are able to reflect on their own work. Although this framework was developed for university students, the outcomes could easily be transferred to secondary school students.

4. Study purpose and relevance

Many countries and researchers have been interested in developing interdisciplinarity in schools. In a changing world, young people need tools to understand the complexity of the world around them. However, these tools must add value to students during their education and, if possible, beyond it. Interdisciplinarity has frequently been described in the past, and many epistemological reflections on the subject have emerged (e.g., Klein, Citation2010; Lenoir & Sauvé, Citation1998). To date, however, studies on the implementation of interdisciplinary approaches in secondary schools have been rare, and no previous literature review has focused on interdisciplinary experiences in school and their effects on teachers or students despite the many attempts to introduce interdisciplinarity in the school setting in different countries.

Indeed, the compartmentalization of knowledge and disciplines as well as the specialization of teachers lead to more difficulties in the implementation of interdisciplinary approaches in secondary education than in primary education. For this reason, it is difficult to obtain a clear picture of the benefits of interdisciplinarity for students and teachers in secondary schools. The purposes of this paper are (1) to establish a state of the art of studies focusing on interdisciplinary experiences in secondary schools, (2) to highlight the measured effects on students and teachers, and (3) to identify the conditions that favor the construction of interdisciplinary sequences.

5. Method

5.1. Data collection and inclusion criteria

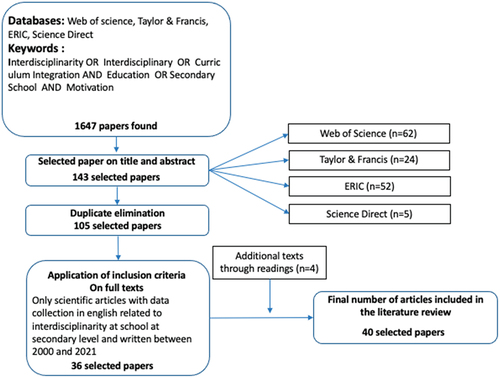

The procedure used for this systematic review follows the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., Citation2021).

For this literature review, articles were searched in the following databases: Web of Science (WOS), Taylor & Francis (T&F), ERIC, and Science Direct (SD). Five keyword combinations were used (see Table ). Because the term “education” was insufficiently restrictive, a wide disparity of texts was found across different grade levels, ranging from elementary to high school to university. In line with our research interest and the specificity of secondary school teachers specializing in specific school subjects, the keyword “education” was replaced with “secondary school”.

Table 1. Keyword Composition and Connectors

Following the keyword associations in the four databases, a total of 1647 texts were analyzed. The first sorting step consisted of the application of five inclusion criteria to the titles and abstracts of the 1647 articles: (1) articles related to school interdisciplinarity or those using a similar term (e.g., curriculum integration, cross-curricular teaching, multidisciplinarity); (2) articles published in peer-reviewed journals and featuring empirical data; (3) articles written in English; (4) articles published after 2000; and (5) articles dealing with or related to the secondary level (e.g., secondary teacher education). Of the 143 texts retained, 38 were duplicates and were thus eliminated.

Of the remaining 105 articles, the inclusion criteria were applied to a reading of the full-text, and 69 of the remaining 105 articles did not meet the criteria (see Table ); thus, a total of 36 articles were included. Four texts were added after the full reading of all 105 articles. A total of 40 texts were thus retained for this analysis. Figure shows the different stages of the selection process. This process was implemented by the two authors and a third external researcher was involved in cases of disagreement.

Table 2. Inclusion Criteria

5.2. Categorization of variables

The first descriptive analysis was based on the following information: year of publication, geographical location, type and size of the sample, type of measure and tools, disciplines involved and main results. An overview of the characteristics of the 40 selected articles is available in the supplemental material.

In a second step, a thematic analysis was conducted on the results of the different studies included in the review following the inductive and deductive methodology proposed by Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (Citation2006). Three themes emerged from this thematic analysis: (1) interdisciplinary experiences in secondary schools, (2) benefits of interdisciplinary teaching, and (3) challenges to interdisciplinary practice. The first theme was divided into two subcategories to analyze existing interdisciplinary practices and identify conditions favorable to the construction of interdisciplinary sequences. The second theme, benefits, included two subthemes based on who benefits from interdisciplinary teaching, (a) students or (b) teachers. Finally, the third theme, the difficulties associated with interdisciplinary practice, was divided into two subthemes: (a) students, for whom interdisciplinarity might be a barrier to learning, and (b) teachers, who must overcome the difficulties encountered during the construction and implementation of interdisciplinary sequences. Within each of these subthemes, subcategories were identified (see Table ).

Table 3. Thematic Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Descriptive analysis

Of the 40 articles selected, 26 articles were published between 2015 and 2019, nine articles were published between 2010 and 2014, and five articles were published between 2000 and 2009. It is interesting to note that among the texts written between 2010 and 2014, five texts were from the same thematic issue of the journal “Issues in Integrative Studies vol. 28 (2010)”, which was dedicated to the analysis of school interdisciplinarity in the classroom.

Of the total number of articles, 20 studies were based in Europe, 12 were based in the Americas including nine in North America, six were based in Australia or New Zealand, and two were multicontinental.

The sample sizes referenced by these studies varied widely. After excluding texts that did not specify the exact number of participants (e.g., participants from one school), the sample sizes ranged from three to 2051 participants, with only seven studies featuring more than 100 participants.

Of the 40 studies, 13 focused on teachers, seven were mixed, seven referred to students, four were aimed at prospective teachers, and four referenced “schools” without further specification. The remaining five texts were curriculum or text analyses.

Of the 40 texts, a large majority of the authors (26) employed a qualitative approach to their data, 10 employed a mixed approach, and four adopted a quantitative approach. More details can be found in Table .

Table 4. Data Type per Theme, Categories and Subtheme

It is also interesting to note that among the 26 studies with results related to student or teacher motivation, only three articles integrated these results into the framework of a recognized theory of motivation (i.e., self-determination theory (SDT) or situational interest (SI)).

Data collection tools were identified in the 40 articles: 21 studies used data collected from interviews or focus groups, 19 used questionnaires, 14 used classroom observations or recordings, 12 used text or curriculum analysis, seven used written work produced by students or teachers, and one used pre- and posttests of learning.

Finally, 28 articles specified the disciplines involved. Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) was the most frequently represented area in the studies with 20 mentions, followed by arts and music with eight mentions and literary disciplines and physical education with five mentions each.

6.2. Interdisciplinary experiences in secondary schools

This section aims (1) to analyze how interdisciplinarity is experienced in practice in schools and (2) to identify the conditions that favor the construction of interdisciplinary sequences. This section presents a wide variety of experiences with different strategies and constraints that help explain what is essential for a quality interdisciplinary approach.

6.2.1. Analysis of interdisciplinary practices in schools

Some authors (n = 7), five of whom were published in the same issue of the journal “Issues in Integrative Studies”, examined the interdisciplinary practices currently implemented in secondary schools without any researcher interventions in their respective countries. Their results indicated that despite teachers’ good will and awareness of the fact that interdisciplinarity is important for their students (Fidalgo Neto et al., Citation2014; Hasni et al., Citation2015), interdisciplinary practices in schools remain superficial, rare, and more similar to multidisciplinarity or intradisciplinarity (i.e., involving interactions among different domains of one discipline) than to interdisciplinarity (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Ghisla et al., Citation2010; Hasni et al., Citation2015; Kneen et al., Citation2020; Rodríguez, Blasco, Lenoir, & Klein, Citation2010). Moreover, the generally evident strong hierarchy among disciplines often leads some disciplines to be put at the service of others, which does not promote integration (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Hasni et al., Citation2015; Lenoir, Hasni, & Klein, Citation2010). Disciplinary hierarchies are present in almost all school systems. In Quebec, for example, French and mathematics are viewed as the most important subjects in the curriculum (Lenoir et al., Citation2010). The problem with disciplinary hierarchies is that they entail the risk of the least valued discipline serving as a substitute for learning in the more valued discipline. This situation does not promote integration and usually leads to pseudointerdisciplinarity. However, according to Baillat and Niclot (Citation2010), participating in an interdisciplinary teaching experience has positive effects on teacher’s conceptions of school interdisciplinarity. After an interdisciplinary experience, teachers are more inclined to repeat the experience and exhibit less reluctance toward interdisciplinarity.

6.2.2. Practical advice for implementing interdisciplinary sequences

Of the 40 articles included in this review, 12 provided practical and/or strategic advice to facilitate the implementation of quality interdisciplinary sequences. Of these 12 articles, five were conducted in Australia or New Zealand, four were conducted in Europe and three were conducted in the Americas. The vast majority of these articles (n = 8) were published between 2015 and 2019, thus highlighting the recent interest in the implementation of interdisciplinarity in schools. The advice of these articles was mostly based on research findings (for 9 articles) or theoretical developments (for 3 articles).

Several authors have highlighted the importance of understanding the links among disciplines. Indeed, in cases featuring a strong link between disciplines, particularly at the level of concepts, it seems that integration is more likely to be successful and higher quality (Gajic & Zukovic, Citation2013; Ghisla et al., Citation2010; Hasni et al., Citation2015; McPhail, Citation2016, Citation2018; Michelsen, Citation2015; Moser et al., Citation2019; Moss et al., Citation2019). McPhail (Citation2016) presented a case in which an economics component was added to a module dominated by a physics problem. The conceptual link between the economics-related part and the module was insufficient. The result was a lack of understanding of the content and the feeling that the students were taking several courses simultaneously. According to Locke (Citation2008), it is essential to view interdisciplinarity as complementary to disciplinarity. When a teacher wishes to implement an interdisciplinary sequence, the alternation between disciplinary and interdisciplinary1 moments must be taken into account to maximize the quality of the sequence. Indeed, interdisciplinary sequences generally address complex problems that require disciplinary knowledge and skills. Complementarity between interdisciplinary and disciplinary moments seems to promote good integration and overall understanding (Locke, Citation2008; McPhail, Citation2016, Citation2018). Indeed, in his study, McPhail (Citation2018) demonstrated that when studying a complex problem, such as the eugenics movement in Germany between the world wars, it is sometimes necessary to master disciplinary concepts (genetics, inheritance, eugenics, totalitarianism, political change, etc.) to be able to integrate these contents and understand the situation in question globally.

Students’ needs and interests are also key elements in the development of interdisciplinary sequences. For Rodríguez et al. (Citation2010), this process is not merely a matter of taking into account students’ needs and interests but also of involving all participants in the construction of the sequence as well as in the construction of the assessment criteria and the assessment process (Bartlett, Citation2005; Locke, Citation2008; McPhail, Citation2018; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010). For example, Locke (Citation2008) suggested that the curriculum should be developed term by term initially based on a major question or concept coconstructed with students. Teachers from all disciplines should then collaboratively plan the content and objectives for the term.

In some larger projects (n = 4) (Bartlett, Citation2005; Locke, Citation2008; McPhail, Citation2016, Citation2018; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019), the structure of some classrooms or schools was modified to be more in line with the different interdisciplinary projects at hand. In these projects, a strong will is evident on the part of the institutions with regard to promoting and facilitating the implementation of interdisciplinarity. One way in which this task has been accomplished is through collaborative curriculum design before the beginning of the school year (e.g. Locke, Citation2008), during which teachers create curricula for all disciplines while, taking into account the needs and interests of students. These changes also affect the form and duration of this process in several types of school organizations. In the situation reported by McPhail (Citation2016, Citation2018), the school agenda stipulated that 17% of the available time would be dedicated to the Learning Hub, which aimed to create a healthy environment for small groups of students; 11% to My Time, which allowed students to choose a subject or project to focus on three times per week; 44% to small interdisciplinary modules; 17% to SPINs (specific interests) that took into account the interests and needs of students; and 11% to long-term projects connected to the community. While Locke (Citation2008) asked teachers to create three-day episodes on defined theme once per semester, Bartlett (Citation2005) presented a model including eight projects per year based on six core competencies,Footnote2 and Pountney and McPhail (Citation2019) proposed four eight- to ten-week expeditions per year that involved more than 85% of the material that students were required to learn.

6.3. Benefits of interdisciplinary teaching

This section presents the observed benefits of the implementation of interdisciplinary approaches. As mentioned, some of the identified benefits pertained to students and others applied to teachers (see Table ).

6.3.1. Benefits for students

Some positive trends were noted by a majority of authors with regard to the effect of interdisciplinary approaches on students. These benefits were categorized into two subdimensions: motivation and achievement.

Motivation. The implementation of interdisciplinary sequences seems to have positive effects on motivation, according to 21 of the 40 articles analyzed (e.g.Bartlett, Citation2005; Cuervo, Citation2018; Gill, Citation2013; Hawkey et al., Citation2019; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Vieira et al., Citation2018). In particular, the implementation of interdisciplinary sequences seems to be more in line with students’ interests and needs by allowing students to choose their learning and by including them in the construction process; moreover, interest in one discipline can sometimes help students develop an interest in another discipline (Bartlett, Citation2005; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; McPhail, Citation2018; Michelsen & Sriraman, Citation2009; Moss et al., Citation2019; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019; Tammaro et al., Citation2017). Several studies have also noted that students seem to enjoy learning more in interdisciplinary sequences than in traditional lessons and that this enjoyment is shared with peers and diversified (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; Kneen et al., Citation2020; Moss et al., Citation2019; Papaioannou et al., Citation2020; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Vega & Schnackenberg, Citation2004). Papaioannou et al. (Citation2020) use a questionnaire (Situational Motivation Scale SIMS) validated by Guay et al. (Citation2000) to measure an increase in autonomous motivation and satisfaction and a decrease in amotivation. Finally, several authors have argued that interdisciplinarity seems to give meaning to learning by allowing students to establish connections between academic learning and reality. This contextualization of academic knowledge increases student motivation (McPhail, Citation2018; Michelsen & Sriraman, Citation2009; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019; Queiruga Dios et al., Citation2021; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Samson, Citation2014; Tammaro et al., Citation2017; Vieira et al., Citation2018).

Achievement. The interdisciplinary approach seems to have beneficial effects on students’ learning according to a majority of studies (n = 25). These learning effects are noted to occur at three levels.

First, interdisciplinary sequences seem to promote an improvement in academic learning by providing a better understanding of academic content (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Bartlett, Citation2005; Bollati et al., Citation2017; Cuervo, Citation2018; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; Locke, Citation2008; Michelsen, Citation2015; Moss et al., Citation2019; Queiruga Dios et al., Citation2021; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016). According to students and teachers, interdisciplinary approaches also provide a more holistic understanding of learning (Cuervo, Citation2018; Fenwick et al., Citation2013; Harris & de Bruin, Citation2018; Locke, Citation2008; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Vieira et al., Citation2018). These approaches create links among disciplines, contribute to the development of a better understanding of disciplinary logics, and promote the transfer of knowledge and skills among disciplines (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Hasni et al., Citation2015; Hawkey et al., Citation2019; Locke, Citation2008; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010). Interdisciplinary sequences may also promote deeper learning and provoke student reflection (Cuervo, Citation2018; McPhail, Citation2018; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019). Finally, they appear to have a positive effect on student achievement on summative assessments (Bollati et al., Citation2017; Cuervo, Citation2018; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016).

Personal skills also seem to be promoted during interdisciplinary sequences by making students active participants in their learning. According to teacher and student interviews in particular, these approaches aim to train autonomous, empathetic, responsible, respectful, and creative students and help develop students’ self-confidence and critical thinking skills (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Bartlett, Citation2005; Braskén et al., Citation2020; Cuervo, Citation2018; Harris & de Bruin, Citation2018; Hawkey et al., Citation2019; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; Kneen et al., Citation2020; Locke, Citation2008; McPhail, Citation2018; Moss et al., Citation2019; Queiruga Dios et al., Citation2021; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Tammaro et al., Citation2017; Vieira et al., Citation2018).

Finally, interdisciplinary approaches seem to promote and develop students’ relational skills by stimulating collaboration, and group work, and by strengthening the social connections among students and between teachers and students (Braskén et al., Citation2020; Fenwick et al., Citation2013; Gill, Citation2013; Harris & de Bruin, Citation2018; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; McPhail, Citation2018; Moss et al., Citation2019; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019; Queiruga Dios et al., Citation2021; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Vieira et al., Citation2018).

6.3.2. Benefits for teachers

Fewer authors (n = 12) referred to the beneficial effects of interdisciplinarity for teachers, but interdisciplinary approaches also seem to have positive effects for teachers. Benefits have been observed in two dimensions: teachers’ motivation and professional development.

Motivation. For teachers, the interdisciplinary approach seems to be a source of motivation (e.g.,Hawkey et al., Citation2019). It is a challenging, routine-breaking approach that stimulates stakeholders (Harris & de Bruin, Citation2018; Michelsen, Citation2015; Moser et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Stubbs & Myers, Citation2016). It is also an approach that allows teachers to perceive the benefits for students and promotes student engagement. For teachers, the ability to observe the evolution of their students provides additional motivation (Hardré et al., Citation2013). This approach also allows teacher to establish better relationships with their colleagues by creating a climate of trust (Fenwick et al., Citation2013; McPhail, Citation2018; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010).

Professional Development. By collaborating with colleagues from all disciplines, interdisciplinary teaching seems to foster teachers’ professional development. Each teacher’s expertise and professional experience are significant assets that endure even after the interdisciplinary experience (Braskén et al., Citation2020; Fenwick et al., Citation2013; Gill, Citation2013; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Harris & de Bruin, Citation2018; Hawkey et al., Citation2019; McPhail, Citation2018; Moser et al., Citation2019; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Tinnell et al., Citation2019). Interdisciplinary approaches also allow teachers to be aware of what is happening in other disciplines and provide opportunities for teachers to increase their knowledge and expertise, especially in disciplines that they do not teach. Interdisciplinary teaching allows teachers to create and understand connections among disciplines (Braskén et al., Citation2020; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Hawkey et al., Citation2019; Locke, Citation2008; Moser et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Tinnell et al., Citation2019). Finally, it offers variety in instruction based on an approach that promotes connections to the real world and enables teachers to allocate time to the students who struggle most (Bartlett, Citation2005; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Hawkey et al., Citation2019; Kneen et al., Citation2020; Tinnell et al., Citation2019).

6.4. Difficulties related to interdisciplinary teaching

6.4.1. Difficulties for students

According to some authors, the implementation of interdisciplinary sequences can have negative consequences on students’ learning. Indeed, if interdisciplinarity is the only approach used, it can lead to disciplinary gaps, confused learning or difficulties in managing the globality of the information received (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Braskén et al., Citation2020; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Hawkey et al., Citation2019; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; McPhail, Citation2018; Vieira et al., Citation2018). These difficulties are encountered more frequently when integration among disciplines is weak or incomplete (multidisciplinarity or pseudointerdisciplinarity).

Conflicts among students also occur more frequently as interdisciplinarity often puts students in situation of cooperation/collaboration (Vieira et al., Citation2018). Complementarity between disciplinary and interdisciplinary moments seems to be a solution to limit these difficulties, although it remain uncommon in the literature (e.g., McPhail, Citation2018).

6.4.2. Difficulties for the teacher

Research has shown that most difficulties pertaining to the implementation of interdisciplinary sequences in secondary schools are naturally linked to the teacher’s job. Indeed, from a vertical perspective, teachers are torn between the injunctions of their hierarchy (management, ministry, etc.) and the implementation of these injunctions in the classroom, while taking into account the students and their needs. The following points highlight the difficulties that must be overcome to implement quality interdisciplinary sequences.

Teacher Professional Identity. The strong disciplinary affiliation of secondary school teachers is a clear obstacle to interdisciplinarity. This disciplinary specialization can make teachers reluctant to adopt this approach because they are often largely unaware of other disciplines and their contents and tend to defend their own branch at all costs at the expense of others (i.e., hierarchization of disciplines) when implementing interdisciplinary projects (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Gajic & Zukovic, Citation2013; Hasni et al., Citation2015; Locke, Citation2008; Michelsen & Sriraman, Citation2009; Michelsen, Citation2015; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Samson, Citation2014). More effective integration of disciplines occurs when teachers view themselves as teachers first and only therafteras specialists (Fenwick et al., Citation2013).

The teacher’s role is also fundamentally different during interdisciplinary sequences. Teachers act more as guides who support and direct students and limit traditional frontal interactions. Studies have shown that teachers find it difficult to change their posture and transition to a less dominant role (Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010; Bartlett, Citation2005; Ghisla et al., Citation2010; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; McPhail, Citation2016; Vieira et al., Citation2018).

Finally, the implementation of interdisciplinary sequences seems to be a challenge for teachers; it is a demanding practice, and few teachers receive interdisciplinary training in their preservice or in-service training. Moreover, the quality of integration seems to be directly related to teachers’ experience and abilities in situation, which does not encourage teachers with little knowledge of other disciplines to gain the confidence necessary to engage in joint projects (Fenwick et al., Citation2013; Gajic & Zukovic, Citation2013; Ghisla et al., Citation2010; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Hasni et al., Citation2015; McPhail, Citation2016, Citation2018; Moss et al., Citation2019; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Samson, Citation2014).

Teacher-Knowledge Relationships. The didactic construction of interdisciplinary sequences is undoubtedly more difficult than that of traditional sequences. The former requires more time because it forces teachers from different subjects to organize and meet more often (Fidalgo Neto et al., Citation2014; Gajic & Zukovic, Citation2013; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Harris & de Bruin, Citation2018; Hasni et al., Citation2015; McPhail, Citation2018; Michelsen, Citation2015; Moss et al., Citation2019; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Samson, Citation2014; Stubbs & Myers, Citation2016).

The lack of framework documents and manuals to guide teachers is also a barrier to implementing these sequences, especially for teachers without experience in the field (Fidalgo Neto et al., Citation2014; Ghisla et al., Citation2010; Hasni et al., Citation2015; Moss et al., Citation2019).

Finally, assessment is an important challenge because general abilities and skills must be assessed in addition to disciplinary abilities and skills. In addition, forms and types of assessment in this context often differ from those associate with traditional assessments, and they must adapt to the different projects being implemented (Bartlett, Citation2005; McPhail, Citation2018; Moss et al., Citation2019).

Teacher-Teacher Relationships. Interdisciplinarity requires collaborative work among teachers, which can obviously lead to relational problems. The use of different terminologies associated with different disciplines can lead to misunderstandings and difficulties when collaborating with teachers of other subjects, especially when groups are excessively large (Fenwick et al., Citation2013; Hasni et al., Citation2015; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; Michelsen, Citation2015; Moser et al., Citation2019; Moss et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Samson, Citation2014; Tinnell et al., Citation2019). Some teachers also prefer to work alone, and when collaboration is forced, it often leads to poor-quality sequences (Samson, Citation2014; Tinnell et al., Citation2019). Therefore, dialog is necessary to clarify the goals of each discipline, plan the sequence and construction, and work in a collaborative manner.

Teacher-Institution Relationships. According to several authors (Fidalgo Neto et al., Citation2014; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Hasni et al., Citation2015; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Samson, Citation2014; Tinnell et al., Citation2019), the structure of secondary schools does not promote interdisciplinarity. Indeed, the programs associated with such schools are designed without collaboration among disciplines, and the defined schedules and periods are too short and thus do not allow for quality interdisciplinarity. Moreover, the support provided by the school administration is often insufficient to motivate teachers in this respect. A genuine institutional will is necessary for the implementation of quality interdisciplinary teaching, which makes it possible to legitimize the practice, solve the problems of time and scheduling, and create a climate of trust and collaboration among teachers (Fenwick et al., Citation2013; Ghisla et al., Citation2010; Hardré et al., Citation2013; Hasni et al., Citation2015; Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Samson, Citation2014).

7. Discussion

The purposes of this paper were (1) to establish a state of art of studies focusing on interdisciplinary experiences in school, (2) to highlight the identified effects on students and teachers and (3) to identify the conditions that favor the construction of interdisciplinary sequences. The diversity of the studies thus analyzed defines a broad framework and leads to the generation of varied observations on interdisciplinary practices in secondary school. The analysis of interdisciplinary practices in schools (e.g., Hasni et al., Citation2015; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010) shows that very few real interdisciplinary sequences are implemented in the field at the secondary level. Moreover, teachers who have tried to adopt this approach have mostly remained at the multidisciplinary stage and have struggled to integrate the disciplines in full.

This failure is probably due to the many obstacles that teachers face when attempting to implement interdisciplinary sequences. In view of the difficulties noted in this review, it is unsurprising that in practice, few teachers attempt to develop of interdisciplinary sequences and that few approaches to teaching are truly interdisciplinary.

These difficulties affect teachers in several aspects of their teaching, their relationship to themselves, their relationship to the content of the disciplines and the available resources, their relationship to collegiality and collaboration with colleagues, and finally, their institutional possibilities and opportunities. The first difficulty for teachers with regard to the degree of integration is that interdisciplinary approaches are more difficult to implement. Indeed, these approaches are complex due to teachers’ lack of knowledge in the nonteaching discipline and to the associated training (initial and continuous), which is insufficient to fill the gaps faced by teachers at this level (e.g., Hasni et al., Citation2015). These approaches to teaching therefore often remain at a multidisciplinary level featuring a mere juxtaposition of knowledge. The fact that few interdisciplinary practices are used in secondary school (in term of quantity), this is also a result of the presence of a strong disciplinary identity among specialist teachers (e.g., Ríordáin et al., Citation2016; Samson, Citation2014). Indeed, a willingness “to familiarize themselves with other disciplines and way of thinking” (Michelsen, Citation2015, p. 493), to collaborate with teachers working in other disciplines, and to overcome hierarchical conceptions that define the importance of branches is necessary to implement an interdisciplinary approach. In particular, teachers often tend to think that their discipline(s) is particularly important in the curriculum and place it above other disciplines (e.g., Samson, Citation2014). It is also necessary to teachers to be able to change roles and no longer to be the sole guarantor of knowledge. In interdisciplinary teaching, the teacher plays more of a guiding role, and the hierarchical teacher-student structure is somewhat attenuated (e.g., Holmbukt & Larsen, Citation2016). This findings confirms the reflections of D’Hainaut (Citation1986) regarding the role and identity of teachers, for whom feelings of incompetence and prestige are linked to mastery of their discipline(s).

In addition, some teachers do not feel comfortable working collaboratively and prefer to work alone. Forcing teachers to work in groups can lead only to conflict and other relational problems (e.g., Hasni et al., Citation2015; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010). Collaborative work can be difficult for some teachers. Although this point was mentioned less frequently by the various articles included in this review, collaboration should not be neglected due to the corresponding risks to the proper functioning of the interdisciplinary sequence (Eishof, Citation2003).

Finally, a lack of support and opportunities, whether due to official guidelines, a lack of textbooks or training (initial or in-service) (Ghisla et al., Citation2010) or structural difficulties (schedule and infrastructure), does not encourage teachers who are open to adopting this more complex approach to think outside the box and invest time in this process. These results are in line with the reflections of Darbellay (Citation2019). Without a real willingness on the part of institutions to facilitate the implementation of interdisciplinary practices, the difficulties associated with this process must be overcome solely by teachers. Any additional effort is made during their personal free time, which is obviously very complicated and limits spontaneous practice to the few teachers who are convinced of this method (e.g., Ghisla et al., Citation2010; Ríordáin et al., Citation2016). However, on this point, in the medium term, the difficulties related to preparation time seem to be mitigated by constructing the programs jointly (interdisciplinarity), which limits the repetition of knowledge and allows the contents to be treated in a complementary way. Thus, in an ideal setting, the complementarity of different disciplines makes sense, and interdisciplinarity represents a practical response to the diversity of knowledge and skills that must be taught (Fenwick et al., Citation2013; Locke, Citation2008; Michelsen, Citation2015; Rodríguez et al., Citation2010; Tammaro et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, it seems that articles on situation in which comprehensive or partial changes have been implemented in the institutional system have reported better integration. This situation was the case, for example, in McPhail (Citation2018), who reported a reorganization of students’ timetables to include thematic modules, long-term projects or even personal time as well as in Fenwick et al. (Citation2013), who observed a marked institutional willingness, especially with regard to the recruitment of teachers, to work collaboratively and in an interdisciplinary manner. However, this approach requires genuine will on the part of the state and school management, as noted by D’Hainaut (Citation1986). Teachers are too often left with guidelines to follow but without the tools or structures necessary to implement them (e.g., Ghisla et al., Citation2010).

This literature review shows that teachers must overcome many obstacles when implementing interdisciplinary sequences. This focus on the difficulties encountered in teachers’ work may be due to the real difficulties faced by the field teachers interviewed in the various studies included in the review.

Although all these difficulties seem to have strong negative impacts on the quantity of sequences implemented and sometimes on the quality of the integration of disciplines, the results of this review show that after having interdisciplinary experience, teachers seem to be less resistant and to exhibit a positive vision of interdisciplinarity (e.g., Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010). Moreover, many positive effects following the implementation of interdisciplinary sequences have been noted by the different studies cited in this review.

Indeed, several studies have reported a positive effect on students’ motivation and learning from the implementation of interdisciplinary approaches (e.g., Michelsen & Sriraman, Citation2009; Moss et al., Citation2019). The results of this review show that several studies identified interdisciplinary approaches as being closer to students’ interests and noted that they aim to give meaning to learning as well as to enable student to learn while having fun, and develop cross-curricular and relational skills and a global vision in addition to knowledge of the disciplines at hand. These results corroborate the reflections of Lattuca et al. (Citation2004) and Lenoir and Sauvé (Citation1998).

It should be noted, however, that a minority of texts have claimed that gaps in learning are possible when integration is poorly implemented (e.g., Vieira et al., Citation2018) and that interdisciplinarity can cause learning to become confusing for students (e.g., Baillat & Niclot, Citation2010). This findings echoes Eishof (Citation2003), according to whom the process of transgressing boundaries is not without danger.

Teachers also seem to benefit from these approaches (e.g., Rodríguez et al., Citation2010). One-third of the studies (n = 12) reported that once teachers have taken a step toward interdisciplinarity, they feel motivated and challenged, develop skills in other disciplines, establish trusting relationships with their colleagues (which leads to decreased loneliness), and benefit from each other’s experience. According to the teachers themselves, they are fully satisfied. Once again, the field results are in line with theoretical reflections (Baluteau, Citation2004) and confirm the proposed ideas.

The results of this review show that according to the articles analyzed, several factors make it possible to define conditions conducive to the construction of interdisciplinary sequences: (1) a strong link must exist between the disciplines in question, particularly at the level of concepts, to avoid instrumentalization; (2) the participants must be involved in the construction and evaluation of the project to allow it to be as close as possible to their needs and interests; (3) interdisciplinarity must be viewed as a complementary approach to disciplinary teaching and not as the application of two opposing approaches (Bartlett, Citation2005; Locke, Citation2008; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019). This final point is included in the fundamental principles of Lenoir and Hasni (Citation2016), who noted that interdisciplinarity cannot exist without disciplinarity, a form of complementarity that is necessary for the implementation of interdisciplinary sequences. The importance of a strong link between disciplines and the integration of participants in the construction and evaluation of sequences are quite specific to a practice setting and are not necessarily found in all epistemological reflections. A combination of the two visions at hand seems to be an ideal way to create quality interdisciplinarity.

Finally, studies conducted in New Zealand and Anglo-New Zealand (n = 5) have very specifically implemented and described interdisciplinary approaches at the institutional level (Bartlett, Citation2005; Locke, Citation2008; McPhail, Citation2016, Citation2018; Pountney & McPhail, Citation2019). A point that all these studies have in common is that they meet the conditions listed above in addition to changing classroom organization and the school structure to varying degrees. Similar to other studies, these studies found positive outcomes for both students and teachers however, more importantly, they found fewer difficulties for teachers. With institutional support, the difficulties noted are to the result of teachers’need to play the role of guides as well as the difficulty of the interdisciplinary approach, which requires certain types of expertise. Other difficulties are due to the time available for implementing this approach and the evaluation, which naturally involved greater complexity than disciplinary situations, as Boix-Mansilla and Duraising (Citation2007) noted. The problems associated with collaboration or relations with other colleagues or the institution which have frequently been reported by other studies included in this review, are no longer in evidence as a result of the institutional will of the directors to organize learning in an interdisciplinary manner.

7.1. Limitations and perspectives

This review face certain limitations that must to be taken into account. First, two-thirds of the studies included in the review(n = 26) used only a qualitative method. This percentage may be as high as 87% for some of the results (see Table ). In addition, only three studies clearly defined the motivational theories used and the tools related to these theories. Michelsen and Sriraman (Citation2009) defined their research in terms of situational interest and created a questionnaire for this purpose. Holmbukt and Larsen (Citation2016) focused on SDT (self-determination theory), as did Papaioannou et al. (Citation2020), who employed a questionnaire (SIMS) validated by Guay et al. (Citation2000).

Only seven studies included samples of more than 100 participants; thus, the results are not generalizable to or representative of a whole population. In addition, the participants in several studies were volunteers and may have received positive advance notice of the use of interdisciplinary approaches. Interdisciplinarity in practice is subject to multiple challenges, which makes this approach dependent on the context in which it is implemented (e.g., Hasni et al., Citation2015). Thus, the articles discussed in this review all focus on very different political and institutional contexts, and it is important to keep this fact in mind when establishing connections among different studies.

In future research, it would be interesting to measure motivation more accurately by using quantitative or even mixed approaches and to link those approaches to a theory of motivation, as was performed in the study conducted by Michelsen and Sriraman (Citation2009). The use of validated questionnaires, as in Papaioannou et al. (Citation2020), would also be beneficial to obtain more generalizable results. Situational interest seems to be a theory that is particularly suitable for measuring the effects of interdisciplinarity since it focuses on the interest that can be aroused in a particular learning context by differentiating between the triggering of students’ interest and its maintenance (including two subscales, i.e., maintenance of feelings and maintenance of values) (Roure, Citation2020). Motivation can therefore be measured at the level of an activity or sequence.

Finally, as mentioned previously, interdisciplinary approaches are difficult to implement and can quickly fall into pseudointerdisciplinarity (e.g., Hasni et al., Citation2015). Therefore, in future research it would be interesting to take into account teacher training (preservice and in-service) as we observed in this review that few teachers are trained in interdisciplinarity, and few are able to integrate two or more disciplines correctly. In addition, it is important to pay particular attention to the political and institutional context of the country and institution in which an interdisciplinary approach is to be implemented.

8. Conclusion

The purposes of this review were (1) to establish a state of art of studies focusing on interdisciplinary experiences in school, (2) to highlight the identified effects on students and teachers and (3) to identify the conditions that favor the construction of interdisciplinary sequences. The results show that few interdisciplinary practices are currently used in secondary schools, and even fewer of these practices achieve real integration. Indeed, the strength of interactions among disciplines is often limited, which leads mainly to multidisciplinarity (weaker integration). Several difficulties can explain the small number of interdisciplinary practices as well as the low level of integration thus observed. For teachers, whether in initial or ongoing education, interdisciplinary training programs are rare. Teachers are not prepared to support interdisciplinary teaching. Teachers must also cope with the guiding role assumed in interdisciplinary approaches and the strong professional identity present in secondary schools. The knowledge-teacher relationship in interdisciplinary approaches is characterized by a longer preparation time, a lack of resources (manuals, frameworks, etc.) and more difficult evaluation. Moreover, teachers must manage their relations with their colleagues. Finally, teachers are also dependent on the institutional choices and opportunities available to them. This point seems to be of crucial importance with regard to the quantity and quality of the interdisciplinary approaches implemented in this context. However, once those difficulties have been overcome, interdisciplinary approaches seem to have a positive effect on students and teachers. By promoting learning, interest, relational competencies, and professional development, an interdisciplinary approach offers the opportunity for those who participate to develop as human beings in a world that is less compartmentalized than the school structure suggests. This review also highlights some essential conditions for constructing interdisciplinary practice in schools. Ensuring quality integration is not always easy in practice, and most projects are very specific to their environment. They are rarely categorized according to the level of integration at hand. It would be very interesting for future research to analyze the effect in the classroom of projects that are defined as multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2216038

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benoit Tonnetti

Benoit Tonnetti is a doctoral student in science education at the University of teacher education, State of Vaud (HEP Vaud), Lausanne, Switzerland and at Fribourg

University, Avenue de l’Europe 20, CH-1700 Fribourg.

email: [email protected]. His current research focus on school interdisciplinarity with a focus on student’s motivation and achievement and teacher’s motivation and professional development. He is also a secondary physical education and physic teacher and is interested in classroom based-research directly tied to sciences teaching practices.

Vanessa Lentillon-Kaestner

Vanessa Lentillon-Kaestner, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2646-4383

Vanessa Lentillon-Kaestner is ordinary professor and head of the physical education and sport unit (UER EPS) at the University of teacher education, State of Vaud (HEP Vaud), Lausanne, Switzerland. She finalized our PhD in 2006 on gender inequalities in physical education at the university of sport of Lyon, France, worked six years at the university of sport of Lausanne, and since 2010 she works at the HEP Vaud. She has developed different research projects on various domains: gender inequalities, eating disorders, doping behaviors, teacher health and professional identity and student motivation in physical education. Based on a psychosocial perspective, her research focuses on both psychological and sociocultural factors that may influence health behaviours in sport and student/teacher behaviours in physical education. She has already developed different national and international research collaborations and obtained different research funding as main applicant.

Notes

1. 1Translated from Lenoir and Sauvé (Citation1998) : […] l’interdisciplinarité scolaire recourt pour sa part aux savoirs dans une perspective éducative; elle vise la formation d’acteurs sociaux par la mise en place des conditions les plus appropriées pour susciter et soutenir le développement des processus intégrateurs et l’appropriation des savoirs en tant que produits cognitifs chez les élèves, ce qui requiert un aménagement des savoirs scolaires au niveau curriculaire, didactique et pédagogique (p.111).

2. The six core competencies by Bartlett (Citation2005) are active learning through inquiry, independent student-centered learning, authentic contexts, collaborative learning, ICT-enhanced learning, and the building of connections to family and community.

References

- Baillat, G., & Niclot, D. (2010). In search of interdisciplinarity in schools in France: From curriculum to practice. Issues in Integrative Studies, 28(28), 170–17.

- Baluteau, F. (2004). Les dispositifs interdisciplinaires dans les collèges: les enjeux de l’engagement. Spirale-Revue de recherches en éducation, 34(34), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.3406/spira.2004.1359

- Bartlett, J. (2005). Curriculum integration in the junior secondary school. Curriculum Matters, 1, 172–186. Retrieved from. //WOS:000208449800010

- Beane, J. A. (1997). Curriculum integration: Designing the core of democratic education. Teachers College Press.

- Boix-Mansilla, V., & Duraising, E. D. (2007). Targeted assessment of students’ interdisciplinary work: An empirically grounded framework proposed. The Journal of Higher Education, 78(2), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2007.0008

- Bollati, I. M., Gatti, C., Pelfini, M. P., Speciale, L., Maffeo, L., & Pelfini, M. (2017). Climbing walls in Earth Sciences education: An interdisciplinary approach for the secondary school (1st level). Rendiconti Online Societa Geologica Italiana, 44, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.3301/rol.2018.19

- Braskén, M., Hemmi, K., & Kurtén, B. (2020). Implementing a Multidisciplinary Curriculum in a Finnish Lower Secondary School – the Perspective of Science and Mathematics. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(6), 852–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1623311

- Choi, B. C., & Pak, A. W. (2006). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine, 29(6), 351.

- Cuervo, L. (2018). Study of an interdisciplinary didactic model in a secondary education music class. Music Education Research, 20(4), 463–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2018.1433148

- Darbellay, F. (2019). L’interdisciplinarité à l’école: succès, résistance, diversité. Alphil.

- D’Hainaut, L. (1986). L’interdisciplinarité dans l’enseignement général. Paris: Division des sciences de l’éducation, des contenus et des méthodes. UNESCO. URL: https://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/31_14_f.pdf

- Eishof, L. (2003). Technological education, interdisciplinarity, and the journey toward sustainable development: Nurturing new communities of practice. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 3(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14926150309556558

- Fenwick, A. J. J., Minty, S., & Priestley, M. (2013). Swimming against the tide: A case study of an integrated social studies department. The Curriculum Journal, 24(3), 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2013.805658

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Fidalgo Neto, A. A., Lopes, R. M., Magalhães, J. L. C., Pierini, M. F., & Alves, L. A. (2014). Interdisciplinarity and teacher education: The teacher’s training of the secondary school in Rio de Janeiro—Brazil. Creative Education, 5(04), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.54035

- Gajic, O., & Zukovic, S. (2013). Integrativity and interdisciplinarity in religious and literary education. European Journal of Science and Theology, 9(4), 61–76. Retrieved from. //WOS:000321473300005

- Ghisla, G., Bausch, L., & Bonoli, L. (2010). Interdisciplinarity in Swiss Schools: A Difficult Step into the Future. Issues in Integrative Studies, 28(28), 295–331.

- Gill, C. (2013). How can the secondary school learning model be adapted to provide for more meaningful curriculum integration?. University of Waikato.

- Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., & Blanchard, C. (2000). On the assessment of situational intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motivation and Emotion, 24(3), 175–213. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005614228250

- Hardré, P. L., Ling, C., Shehab, R. L., Nanny, M. A., Nollert, M. U., Refai, H., & Wollega, E. D. (2013). Teachers in an interdisciplinary learning community: Engaging, integrating, and strengthening K-12 education. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(5), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487113496640

- Harris, A., & de Bruin, L. (2018). An international study of creative pedagogies in practice in secondary schools: Toward a creative ecology. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 15(2), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2018.1457999

- Hasni, A., Lenoir, Y., & Alessandra, F. (2015). Mandated Interdisciplinarity in Secondary School: The Case of Science, Technology, and Mathematics Teachers in Quebec. Issues in Interdisciplinary Studies, 33(33), 144–180.

- Hawkey, K., James, J., & Tidmarsh, C. (2019). Using Wicked problems to foster interdisciplinary practice among UK trainee teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45(4), 446–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2019.1639263

- Holmbukt, T. E., & Larsen, A. B. (2016). Interdisciplinary teaching as motivation: An initiative for change in post-16 vocational education. Nordic Journal of Modern Language Methodology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.46364/njmlm.v4i1.325

- Klein, J. T. (1990). Interdisciplinarity: History, theory, and practice. Wayne state university press.

- Klein, J. T. (2010). A taxonomy of interdisciplinarity. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, 15(6), 15–30.

- Kneen, J., Breeze, T., Davies-Barnes, S., John, V., & Thayer, E. (2020). Curriculum integration: The challenges for primary and secondary schools in developing a new curriculum in the expressive arts. The Curriculum Journal, 31(2), 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.34

- Lattuca, L. R., Voight, L. J., & Fath, K. Q. (2004). Does interdisciplinarity promote learning? Theoretical support and researchable questions. The Review of Higher Education, 28(1), 23±. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2004.0028

- Lenoir, Y., & Hasni, A. (2016). Interdisciplinarity in primary and secondary school: Issues and perspectives. Creative Education, 7(16), 2433–2458. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.716233

- Lenoir, Y., Hasni, A., & Klein, J. T. (2010). Interdisciplinarity in Quebec schools: 40 years of problematic implementation. Issues in Integrative Studies, 28(28), 238–294.

- Lenoir, Y., & Sauvé, L. (1998). Note de synthèse. De l’interdisciplinarité scolaire à l’interdisciplinarité dans la formation à l’enseignement: un état de la question [2-Interdisciplinarité scolaire et formation interdisciplinaire à l’enseignement]. Revue Française de Pédagogie, 125(1), 109–146. https://doi.org/10.3406/rfp.1998.1111

- Locke, J. (2008). Curriculum integration in secondary schools. Curriculum Matters, 4, 69–84. Retrieved from. //WOS:000263835500006

- McPhail, G. J. (2016). From aspirations to practice: Curriculum challenges for a new ‘twenty-first-century’ secondary school. The Curriculum Journal, 27(4), 518–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2016.1159593

- McPhail, G. J. (2018). Curriculum integration in the senior secondary school: A case study in a national assessment context. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(1), 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2017.1386234

- Michelsen, C. (2015). Mathematical modeling is also physics—interdisciplinary teaching between mathematics and physics in Danish upper secondary education. Physics Education, 50(4), 489. Retrieved from http://stacks.iop.org/0031-9120/50/i=4/a=489

- Michelsen, C., & Sriraman, B. (2009). Does interdisciplinary instruction raise students’ interest in mathematics and the subjects of the natural sciences? ZDM, 41(1–2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-008-0161-5

- Moser, K. M., Ivy, J., & Hopper, P. F. (2019). Rethinking content teaching at the middle level: An interdisciplinary approach. Middle School Journal, 50(2), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2019.1576579

- Moss, J., Godinho, S., & Chao, E. (2019). Enacting the Australian Curriculum: Primary and Secondary Teachers’ Approaches to Integrating the Curriculum. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v44n3.2

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

- Papaioannou, A., Milosis, D., & Gotzaridis, C. (2020). Interdisciplinary Teaching of Physics in Physical Education: Effects on Students’ Autonomous Motivation and Satisfaction. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(2), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2018-0315

- Pountney, R., & McPhail, G. (2019). Crossing boundaries: Exploring the theory, practice and possibility of a ‘Future 3’ curriculum. British Educational Research Journal, 45(3), 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3508

- Queiruga Dios, M. -Á., López-Iñesta, E., Diez-Ojeda, M., Sáiz-Manzanares, M. -C., & Vázquez-Dorrío, J. -B. (2021). Implementation of a STEAM project in compulsory secondary education that creates connections with the environment (Implementación de un proyecto STEAM en Educación Secundaria generando conexiones con el entorno). Journal for the Study of Education & Development, 44(4), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2021.1925475

- Ríordáin, M. N., Johnston, J., & Walshe, G. (2016). Making mathematics and science integration happen: Key aspects of practice. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 47(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2015.1078001

- Rodríguez, J. G., Blasco, C. M., Lenoir, Y., & Klein, J. T. (2010). Interdisciplinarity and research on local issues in schools: Policies and experiences from Colombia. Issues in Interdisciplinary Studies, 28(28), 109–137.

- Roure, C. (2020). Clarification du construit de l’intérêt en situation en éducation physique. [Clarification of situational interest construct in physical education]. Staps, 130(4), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.3917/sta.130.0061

- Samson, G. (2014). From Writing to Doing: The Challenges of Implementing Integration (and Interdisciplinarity) in the Teaching of Mathematics, Sciences, and Technology. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 14(4), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14926156.2014.964883

- Schulert, J., Frank, A., Bailis, S., & Klein, J. T. (1994). Interdisciplinary studies as change of perspective. Issues in Interdisciplinary Studies, 12(12), 77–92.

- Stubbs, E. A., & Myers, B. E. (2016). Part of What We Do: Teacher Perceptions of STEM Integration. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(3), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2016.0308

- Tammaro, R., D’Alessio, A., & Petolicchio, A. (2017). Orienteering: Motivation, multidisciplinary and skills. A project in a secondary school in the province of Salerno. International Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 9(5), 34–40.

- Tinnell, T. L., Tretter, T. R., Thornburg, W., & Ralston, P. S. (2019). Successful Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Supporting Science Teachers with a Systematic, Ongoing, Intentional Collaboration Between University Engineering and Science Teacher Education Faculty. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 30(6), 621–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2019.1593086

- Vega, E. S., & Schnackenberg, H. L. (2004). Integrating Technology, Art, and Writing: Creating Comic Books as an Interdisciplinary Learning Experience. Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 2(27), 818–823.

- Vieira, A. A. S., Dias, L., & Chediak, S. (2018). Challenges and contributions regarding integration of disciplines in the vocational education integrated to upper secondary education at ifms, nova andradina campus. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação, 13(esp1), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.21723/riaee.nesp1.v13.2018.11425