Abstract

Job advertisements provide accessible and practical data to explore labour market dynamics and recruitment trends. This paper presents a scoping review of empirical studies using teacher or teacher educator job advertisements as primary data. Particularly, this review will provide a structured overview of the methodology and objectives of the studies in order to gain a better understanding of how job advertisements in the fields of teaching and teacher education have been investigated, and from what perspectives. As a result of a comprehensive search strategy, which included eight database searches, Google Scholar searches and a hand-search of the citations and reference lists, a total of twenty-three studies were included for this review. The studies sought to achieve a wide range of research objectives by analysing candidate descriptions, position descriptions, and institution descriptions contained in the advertisements. By pointing out the deficiencies of existing research in its methodological rigour, such as selecting data sources, sampling and conducting analysis, this review serves as a useful guide for conducting and further developing job advertisement research in the field of education.

1. Introduction

Job advertisements are written documents about specific job openings acknowledged through public media channels (Fu, Citation2012). They provide relevant information, for instance, about the employer, duties and responsibilities in the position in question, and the experience, qualifications, skills and knowledge required for the job (Kim & Angnakoon, Citation2016). Job advertisements are a key public bridge between recruiters and applicants, and, thus, play an important role in the early stages of the recruitment (Barber, Citation1998). In general, the main purpose of job ads is to attract the most suited candidates to apply for and fill vacant positions (Fu, Citation2012).

Job ad analysis has been regarded as an established approach for researchers, institutions and policymakers to explore the dynamics of labour markets and illustrate the emerging and future trends in recruitment (Mahjoub & Kruyen, Citation2021). A major motivation for studies which use job advertisements as data is to examine the (changing) nature of skills which are required in the workplace (Harper, Citation2012). Job ad analysis has been commonly used to identify gaps and lack of congruence between education offerings and employment requirements, and, thus, to provide a tool for curriculum development and redesigning the education to help prepare students to meet future workforce needs (Kim & Angnakoon, Citation2016). It also reveals disparities between the skills emphasized in previous literature and those sought by employers: for instance, some 21st-century skills touted as vital for workplace success, like social responsibility, are not mentioned or in low demand in job ads (Rios et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, there are weaknesses and criticisms regarding job ad research: these gaps include the lack of clarity regarding competencies required for different professions (Mahjoub & Kruyen, Citation2021) and inconsistencies among methodology which affects and hinders the comparison of findings and the drawing of definitive conclusions (Kim & Angnakoon, Citation2016).

In this review, a structured overview of the methodology and objectives in empiric research that has used teacher or teacher educator job ads as primary data is provided. The goal is to gain a better understanding of how job advertisements in the fields of teaching and teacher education have been investigated, and from what perspectives. The objective is not to undertake a full systematic review, but to conduct a scoping review on the extent, nature, and range of available research. Unlike a systematic review, a scoping review does do not aim to produce a critically appraised and synthesized answer to a particular question (Munn et al., Citation2018). Instead, scoping reviews aim to provide an overview of the ways the research has been conducted, clarify key concepts or definitions, and identify gaps in the existing research (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). A scoping review is a particularly useful approach in situations when it is still unclear what other, more specific questions can or should be posed or when the information on a topic has not been comprehensively reviewed (Munn et al., Citation2018). No previous publication on this topic employing review methodology was identified.

2. Research method

Empirical studies in which the content of teacher or teacher educator job ads was analysed were included for the review. Studies examining the job advertisements for teachers at various levels from early childhood education to secondary level were widely searched. At post-secondary level, only those studies that included an analysis of teacher educator job advertisements were included. In this study, teacher educator is defined as a profession that involves pre-service work with student teachers in a higher education. These criteria served as a means of judging the relevance of a study.

To identify studies analysing the content of teacher or teacher educator job ads, comprehensive and structured searches were conducted on December 20 and 21, 2021, in the following eight databases: Educational Resources Information Centre, Education Research Complete, Teacher Reference Centre, Education Source, EBSCO Open Dissertations, Education Database, SCOPUS and Web of Science. The searches were carried out using truncated search terms and Boolean operators described in Table . In addition, Google Scholar was used as a supplemental source, since it provides, despite its limitations, a powerful search tool for grey literature, such as conference papers, theses and dissertations, and reports. The Google Scholar searches were conducted with various combinations of the terms and the first 300 hits sorted by relevance by Google were screened, as recommended by Haddaway et al. (Citation2015).

Table 1. Search phrases in database searches

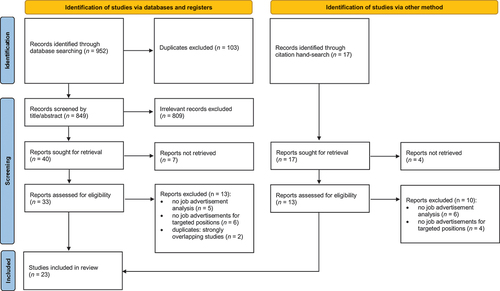

The database (942 citations) and Google Scholar (10 citations) searches yielded 952 potentially relevant citations, from which 103 duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts for the remaining 849 articles were reviewed for relevance. In addition to the bulk of studies from other fields and irrelevant sources presenting career opportunities, open positions or recruitment services, studies addressing teacher recruitment without analysis of job ads were excluded.

At this point, 40 papers were found to meet the inclusion criteria. Seven papers were unobtainable and, accordingly, 33 articles were retrieved and read in full to further assess their eligibility. Based on the full text screening 13 articles were removed for not including job advertisement analysis, not including job advertisements for targeted positions as data, or because they were considered duplicates since the study design, sample, findings and conclusions strongly overlapped with another study included in the review. Therefore, 20 papers were included in the review at this stage.

In addition, a hand-search of the citations and reference list of each of the included articles that met the inclusion criteria was performed to ensure validity of the process. The process was continued until saturation point was reached and no new articles were identified (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). The hand-search added three more articles. The search strategy outlined above resulted in a total of 23 studies for this review. Figure represents the flow of studies through identification to inclusion following The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Each included study was coded based on the following features: (1) bibliographical information, (2) methodological information, and (3) information on research objectives. Bibliographical information included publication year, publication channel and country/ies of origin. Methodological information included the following features: data source, i.e. the source from which the job ads were sampled; sampling period, i.e. the timeframe in which the job ads were collected; sample size, i.e. the number of job ads collected; sample type, i.e. teacher or teacher educator job ads; job ads for other positions or from other fields included in the study; analysis techniques; analysis software used; and other data or methods included in the study. Information on research objectives consisted of the objectives of the study, research questions/hypotheses and selected study variables. The key information on the studies included in the review are summarized in the Appendix.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive overview

3.1.1. Publication channel

Of the 23 studies included, 20 have been published in peer-reviewed journals. The articles were published in a wide range of journals, with only Journal of Education for Teaching, TESOL Journal and Teacher Education and Special Education containing more than one included article (two each). Three of the studies are conference papers.

3.1.2. Publication trend

The studies were published between 1991 and 2021. The greatest number of articles were published in 2013 (n = 4). The volume of job ad research papers has grown during the last decade: during the 2010s twelve papers were published, while the number in the 1990s and 2000s combined was only eight. In the beginning of the 2020s three papers have been published.

3.1.3. Country of origin

Of the 23 studies, nine were conducted in the United States and three in Australia. Four of the studies conducted a cross-national examination in two or more countries: while Bryce et al. (Citation1991) demonstrated teacher recruitment between two countries, i.e. England and Scotland, Selvi (Citation2010) examined English language teacher job advertisements in 12 countries in North and South America, Europe, Asia and Africa.

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Data source

A variety of sources have been used to collect the job ad sample. Recruitment websites, such as jobs.ac.uk, higheredjobs.com, or seek.com.au, were the most common data source: more than half of the studies (n = 12) utilized the online job-search platforms. Ten of the studies used advertisement posted in newspapers, such as The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Guardian or The Hindustan Times. Local institutional websites, such as university, school, board of education or municipality websites, were utilized in five studies. One study (Mackenzie, Citation2021) gathered the data from two “prominent” Facebook groups for English language teachers in Colombia by arguing that, instead of internationally known websites, ads for positions as English language teachers in Colombia are much more common on social media, perhaps because, in contrast to most job websites, such advertising is free and posting is time-efficient. (p. 8)

The number of sources from which job ads were collected varied from sole source (n = 11) to 54 harvested websites (Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014). Five studies combined two types of sources, i.e. recruitment websites and local institutional websites (n = 4) or newspapers (n = 1). Multiple (types of) sources were used because researchers wanted “to provide a higher number of relevant results” (Talmo et al., Citation2020, p. 406) or to be “confident of obtaining as comprehensive list as possible of available positions” (Sims et al., Citation2010, p. 69).

3.2.2. Sampling

Ten studies focused on teacher job ads, i.e. ads for recruiting teachers from early childhood education to secondary level. Twelve studies analysed teacher educator job ads, i.e. ads advertising a position which includes work with pre-service student teachers in higher education institutions. The study by Bailey et al. (Citation2013) included both K−12 teacher and teacher educator job ads. The sample size in studies ranged between three and 3026 job advertisements (M = 382). Nine studies examined fewer than 100 job advertisements, while four studies examined more than 500 ads. Three studies included other job ads from other professions or fields as well.

Teacher recruitment in different countries can be considered to be highly seasonal, with most resignation and hiring activity occurring during specific months. Also, in HE institutions seasonal variation in recruitment needs to be considered, and for example Ellis et al. (Citation2012) chose their sampling periods because “it was felt they represented the busiest recruitment periods for universities and colleges” (p. 687). The sampling period in studies varied from one day to 24 months (<6 months, n = 6; 6–11 months, n = 8; ≥12 months, n = 7). A few studies provided more detailed information on the sampling period: for example, Nuttall et al. (Citation2013) reported that “a weekly scan” (p. 331) of the websites was conducted, Barrow (Citation2003) indicated that the announcements “were read weekly” (p. 144), and Piróg and Hibszer (Citation2020) stated that the data were collected “on the second working day of each week” (p. 69). Based on the sampling period descriptions, Selvi (Citation2010) collected the data most frequently by monitoring websites “daily for a period of three months” (p. 163).

3.2.3. Analysis

All studies in this review analysed the content of job ads. Analyses were labelled, for example, as content analysis (Twombly et al., Citation2006), thematic analysis (Oraison et al., Citation2019) or as constant comparison method (Hales & Clarke, Citation2016). Usually, a scheme comprised of variables and categories was constructed for the coding. For example, Sims et al. (Citation2010) described the design of the coding form as follows:

We first added items on the basis of our experiences with reading and creating music education position announcements and then examined sample job descriptions and added categories until we reached redundancy, that is, the point at which we found no new information in the announcements that could not be accounted for on the form. (p. 69)

Some of the studies adapted a more complex and diverse forms of analysis. For example Ellis et al. (Citation2012) (followed by Gunn et al., Citation2015) performed a variety of analytic approaches, such as 1) membership categorisation, 2) linguistic annotation strategy, 3) word frequencies and key-words-in-context analysis, and 4) genre analysis. Descriptive statistics using frequency and cross-tabulation were commonly used to summarize the data quantitively. Nevertheless, statistical tests, i.e. chi-square and/or t-test, were carried out only in three studies (Anand, Citation2013; Barrow & Smith, Citation1994; Twombly et al., Citation2006). The low number of studies using statistical tests highlight the fact that job ad studies are descriptive in nature and rarely generate hypotheses.

Various methods were performed to improve reliability of the analysis. Out of all studies, only one (Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014) reported the calculated intercoder reliability, which refers to the extent to which two or more independent coders agree on the coding: “the coding for one third of the positions across the entire sample was completed by two independent coders to allow calculation of interrater reliability […] as calculated by agreements divided by agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100, was 84.5%” (p. 54). The study by Sims et al. (Citation2010) used a second individual not otherwise involved in the study to “check 30 (26%) randomly selected forms against the announcements to demonstrate third-party verifiability” (p. 69). Other methods to enhance reliability included having two or more independent coders (without reporting intercoder reliability), completing the analysis several times to ensure consistency, creating detailed instructions with descriptions of the underlying categories and coding rules, producing analytic memos and providing regular crosschecking for data interpretation and representation at each stage. The use of data analysis software was reported in two studies: MYSTAT was adopted in the study by Barrow and Smith (Citation1994), and Wordsmith and Max QDA in the study by Ellis et al. (Citation2012).

3.2.4. Other data or methods combined

Five studies analysed other datasets in addition to the job ad sample in their study. Telephone interviews were performed by Ellis et al. (Citation2012) and Gunn et al. (Citation2015), who interviewed the named personnel from the job advertisements to explore “how the position had come about, how its advertisement and associated documents were developed” (p. 311). Twombly et al. (Citation2006) used two survey datasets: first, from all individuals who earned doctorates from a graduate school and second, for chairs or an institutional contact from the listed job advertisements. Oraison et al. (Citation2019) utilized documents such as university course descriptions. Piróg and Hibszer (Citation2020) used official reports and statistics obtained from the Polish Ministry of Education that included, for example, the demographic profile of teachers.

3.3. Research objectives

3.3.1. The form of research objectives

All studies included in this review included an explicit statement of the objective, purpose, aim or goal of their research. Almost half (n = 11) of the studies formulated research question(s) that guided the research. The number of research questions that were answered with the job ad data ranged between one and nine (M = 3.36): Hales and Clarke (Citation2016) formed one broad question, i.e. “how is the concept of the Teacher Educator being constructed in Canadian university job advertisements?” (p. 321), while Yaman and Şahin (Citation2019) generated nine research questions for job ads, such as “what is the numerical distribution of the job advertisements about different branches of teaching?” and “what kind of special features are expected from the candidates in the job advertisements about English language teachers?” (p. 4).

Of those studies that formulated research questions, a majority (n = 8) formulated open-ended research questions beginning with words such as what and how. Two studies used closed-ended questions starting with the words do and does. One study (Talmo et al., Citation2020) posed research questions that were interpreted as representing both open-ended questions, i.e. “to what degree do job announcements looking for language teachers mention digital skills?”, and closed-ended question, i.e. “is there a relationship between strategic demands and the actual announcements at an institutional level considering digital skills for language teachers?” (p. 405). Only one study (Anand, Citation2013) expressed a clear hypothesis. Therefore, the fact that studies rarely formulate closed-ended questions or hypotheses confirms the earlier finding that teacher and teacher educator job ad studies are predominantly exploratory or descriptive in nature.

To achieve objectives, researchers selected certain study variables to analyse the job advertisement sample. The variables were classified into three categories: 1) candidate descriptions, 2) position descriptions and 3) institution descriptions. Categories, variables, and frequencies (i.e. number of studies targeting certain variables) are presented in Table . Each category and included variables are described in detail in the following sections (3.3.2.–3.3.4).

Table 2. Selected study variables

3.3.2. Candidate descriptions

Almost all of the studies included in this review (n = 21, except Bryce et al., Citation1991; Piróg & Hibszer, Citation2020) analysed the descriptions of a successful candidate in the teacher and teacher educator job ads. The purpose of this was “to provide current information about employer expectations for TESOL [Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages] job seekers” (Bailey et al., Citation2013, p. 774), to investigate “which attributes of teachers were seen by employers as important” (Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014, p. 53) and “to analyze the needs of the education market” (Talmo et al., Citation2020, p. 401). Stephenson and Carter (Citation2014) provided a useful clarification for classifying the tone in candidate description analysis:

Criteria were coded as ‘essential’ if the wording included terms such as ‘must have’, ‘will need to’, ‘be required to’, ‘prerequisite’ in relation to any job requirements. […] A similar set of codes was used for desirable criteria and for criteria that were not specified as essential or desirable. Desirable criteria were those that were described by terms such as ‘should’, ‘would be an advantage’ or ‘ideally’, or were listed under the heading ‘desirable’. Unspecified criteria were those where no indication of desirability was given and included terms such as ‘applications are invited from’ or ‘we seek’. (p. 54)

Also, Twombly et al. (Citation2006) used a similar type of classification of required and preferred qualifications.

Degrees, certifications and registrations were coded in more than half of the studies (n = 14). Studies examining teacher educator job ads often analysed whether a doctorate (or imminent doctorate or doctorate in progress) was required for the position or not. For example, Twombly et al. (Citation2006) identified that a “terminal degree [the highest achievable degree in an academic field, usually PhD] was the most commonly required and preferred qualification” (p. 503) for the positions in the field of teacher education. Requirements for an undergraduate, bachelors’ or master’s degree were also examined. Interestingly, Selvi (Citation2010) found that some English language teacher job ads narrowed the definition of suitable degrees, by requiring “degrees from or professional training at American or Anglophone universities” (p. 166). Requirements for teacher registration (Gunn et al., Citation2015; Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014) and certification (Hales & Clarke, Citation2016; Mackenzie, Citation2021; Mahboob & Golden, Citation2013; Twombly et al., Citation2006) were also analysed.

Skills, knowledge and abilities (SKAs) were analysed in 14 studies as well. One common approach was to examine listed SKAs in educational technology, such as skills in multimedia web development and provision of online courses (Barrow, Citation2003), knowledge of distance education and e-mail technology (Lasseter & Ryndak, Citation1998) and competence to incorporate technology in a learning environment (Oraison et al., Citation2019) or curriculum (Sims et al., Citation2010). The study by Talmo et al. (Citation2020) analysed the digital skills requirements in language teacher job advertisements: they found that there are very few announcements that mention digital skills, and that “when digital skills are mentioned, most of the job announcements for language teachers require generic digital skills, i.e. being confident about ICT […] from the total of 854 announcements there are only 18 that ask for specific digital skills” (p. 410). The other common approach was to investigate whether ads required skills related to special education, such as expertise in disabilities (Ryndak & Sirvis, Citation1999; Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014). More contextual analyses of SKAs were also performed: for example, requirements for level of English and other languages were examined in an English language teacher job ad study (Mackenzie, Citation2021) and expertise in music education methods such as Orff, Kodaly or Dalcroze was examined in a study using music teacher educator job ads (Sims et al., Citation2010).

Studies analysing previous experience (n = 12) targeted listed requirements for teaching experience and/or other experience. In addition to whether teaching experience was listed in the job ads, the length of teaching experience (Bailey et al., Citation2013; Selvi, Citation2010; Yaman & Şahin, Citation2019) and level of teaching experience, i.e. primary, secondary or tertiary teaching experience (Barrow, Citation2003; Gunn et al., Citation2015; Nuttall et al., Citation2013; Sims et al., Citation2010) were also analysed. The study by Hales and Clarke (Citation2016) noticed that recent teaching experience at primary or secondary level was frequently listed in teacher educator job ads. Other experience, mainly analysed in teacher educator job ad studies, was usually connected to research activity, i.e. reputation in research and an established record of research publication (Gunn et al., Citation2015; Hales & Clarke, Citation2016; Nuttall et al., Citation2013; Twombly et al., Citation2006).

Personal qualities were analysed in six studies. For example, Ellis et al. (Citation2012) stated that “personal qualities were important in a significant minority of the advertisements” (p. 689). Hales and Clarke (Citation2016) continued by pointing out that “the use of personal descriptors (i.e., adjectives) and references to personal character were inconsistent across the advertisements” (p. 326). The above-mentioned studies indicated that personal qualities prioritized in job advertisements for teacher educator positions were “enthusiasm, dedication and resilience” (Ellis et al., Citation2012, p. 689) and being “’committed,’ “strong” and “excellent””, while the “use of terms such as ‘ethical,’ ‘learner-centred,’ ‘collaborative’ and ‘willing’ was limited to singular cases” (Hales & Clarke, Citation2016, p. 326). In teacher job ad studies, the personal qualities more frequently listed included, for example, interpersonal skills and teamwork (Bailey et al., Citation2013; Oraison et al., Citation2019; Selvi, Citation2010), sensitivity to cultural diversity and intercultural understanding (Bailey et al., Citation2013; Selvi, Citation2010), professionalism (Selvi, Citation2010), leadership skills and the right ethos for a particular educational institution, such as “strong commitment to Catholic education” (Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014, p. 57).

Biographical factors were analysed in five studies. The main approach in all of these studies was to examine discrimination and inequitable hiring practices through job advertisements. Four of the studies examined discrimination in English language teacher job ads focusing especially on nativeness and nationality preferences listed in the ads (Mackenzie, Citation2021; Mahboob & Golden, Citation2013; Selvi, Citation2010; Yaman & Şahin, Citation2019). The following example of an observed discriminatory requirement is provided by Selvi (Citation2010): “native English speaker or speaker with native‐like abilities with citizenship from one of the following countries: Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States” (p. 165–166). The highest proportion of discriminatory nativeness and/or nationality requirements were found in the study by Mahboob and Golden (Citation2013), in which 87 percent of the examined ads set the above-mentioned requirements. In other studies, the observed proportion of discriminatory ads including nativeness and/or nationality requirements were, in descending order, 60.5 percent (Selvi, Citation2010), 24.4 percent (Yaman & Şahin, Citation2019) and 23.1 percent (Mackenzie, Citation2021). Discrimination was also analysed from perspectives of age, gender and race. The study by Anand (Citation2013) focused solely on discrimination by gender or, as stated in the study, “gender stereotyping in recruitment advertisements” (p. 311). Of the school teacher job ads 16 percent included gender preferences, all targeting recruitment of a female candidate. Expressions such as “‘female candidates’, ‘energetic young female pgt’, ‘expd. lady teachers’” were used (p. 315).

3.3.3. Position description

A majority (n = 15) of the studies included in this review analysed the position descriptions in the teacher and teacher educator job ads. Duties and responsibilities were analysed in 12 studies by often subdividing the perspective into two, i.e. teaching duties and responsibilities and other (nonteaching) duties and responsibilities. Teaching duties and responsibilities were coded, for example, on the basis of context (e.g. English as a second language or English as a foreign language, Selvi, Citation2010), grade or subject (Bryce et al., Citation1991), courses (e.g. Sims et al., Citation2010) or the placement of the position (e.g. regular class, support class, special school or unspecified, Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014). Nuttall et al. (Citation2013) observed that almost all teacher educator job ads “describe the daily work of the successful applicant as largely comprising teaching, including lecturing, teaching tutorials, course coordination and administrative tasks related to teaching” (p. 336). By analysing the verbs attributed to teaching duties in a teacher educator position Ellis et al. (Citation2012) perceived that “most of the further particulars emphasized the variety of teaching required by the posts but there were many references to training and delivering content” (p. 689, see also Gunn et al., Citation2015). The other main responsibilities analysed, mainly in the teacher educator job ad studies, were the supervision of student teachers and pre-service practicums (Barrow & Smith, Citation1994; Gunn et al., Citation2015; Hales & Clarke, Citation2016; Sims et al., Citation2010) and research activity, including publishing and writing grants. The position of research varied in the descriptions of teacher educators’ main duties between and within institutions, and it was rarely given priority among the main duties (Ellis et al., Citation2012). However, Hales and Clarke (Citation2016) argue that teacher educator job ads suggest comparable commitment to both teaching and research as a duty; in summary they state that their “characterisation of teacher educators’ work reveals an all-encompassing range of institutional commitments to scholarship, teaching and fieldwork—specifically the supervision and instruction of pre-service teachers” (p. 327).

Title and rank were targeted in 11 studies. For example, Stephenson and Carter (Citation2014) coded position titles under certain professional categories. Sims et al. (Citation2010) discovered that although many teacher educator job ads included the position title directly in the heading, and some specified the title in the text of the announcement, a substantial number did not provide a specific title for the position other than “music education”” (p. 71). Accordingly, Nuttall et al. (Citation2013) perceived “the almost complete absence of the ‘teacher educator’ within these texts” (p. 329). Therefore, it is understandable that Ellis et al. (Citation2012) adopted a broader conceptual stance by analysing the main noun used for describing the position of teacher educator, such as practitioner, educator, pedagogue and lecturer. In addition to the title, the rank of the position was analysed, for example in terms of whether the position was ranked as full-associate, associate, assistant-associate level or assistant (Barrow, Citation2001, Citation2003; Hales & Clarke, Citation2016; Sims et al., Citation2010), or to a certain level from “level A (first level of lecturer) through to Level E (professor)” (Nuttall et al., Citation2013, p. 331). Also, tenure track status was examined: Barrow and Smith (Citation1994) and Sims et al. (Citation2010) observed that the majority of the advertised teacher educator positions were tenure track positions.

Terms of employment were analysed in four studies. This included the analysis of whether job ads advertise part-time or full-time positions (Piróg & Hibszer, Citation2020; Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014; Yaman & Şahin, Citation2019), or permanent or fixed term positions (Piróg & Hibszer, Citation2020; Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014). It is noteworthy that only one study (Bailey et al., Citation2013) analyzed salary information and range. The limited number of studies on this topic may be attributed to the infrequency of detailed salary information presented in job ads, which can make analysis difficult or even impossible.

3.3.4. Institution description

A majority of studies (n = 15) incorporated the analysis of institution descriptions, including institution type, institution size, geographic location of the institution and/or institutional priorities. Institution type was classified in 11 studies. Various categorizations were utilized when specifying the type of institution, such as educational level (Bryce et al., Citation1991; Piróg & Hibszer, Citation2020; Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014; Twombly et al., Citation2006), education sector, i.e. independent or maintained, publicly or privately supported (Bryce et al., Citation1991; Sims et al., Citation2010; Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014; Talmo et al., Citation2020; Twombly et al., Citation2006; Yaman & Şahin, Citation2019), religion (Bryce et al., Citation1991; Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014), gender, i.e. single/mixed, and number of pupils (Bryce et al., Citation1991). Also, some established rankings, such as the Carnegie Classification in the United States (Barrow, Citation2003; Twombly et al., Citation2006), groupings and networks, such as the Group of 8 in Australia (Nuttall et al., Citation2013), were utilized. In some teacher educator job ad studies, the hiring institutions were also classified in terms of disciplines and departments (Nuttall et al., Citation2013; Sims et al., Citation2010; Twombly et al., Citation2006).

Geographic location of the hiring institution was coded in 11 studies as well. Yaman and Şahin (Citation2019) coded the location to represent distribution of English language teacher advertisements in Turkish cities while Piróg and Hibszer (Citation2020) coded the location to represent the distribution of geography teacher jobs offered in cities, towns, small towns and villages in Poland. Coding of the location and regional comparisons were performed in various ways depending on the established regional systems in each country, such as states (Barrow & Smith, Citation1994; Barrow, Citation2001, Citation2003; Sims et al., Citation2010; Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014), regional divisions (Bailey et al., Citation2013) and territories (Stephenson & Carter, Citation2014). A comparative approach between countries (Bryce et al., Citation1991; Selvi, Citation2010) and regions, e.g. Middle East and East Asia (Mahboob & Golden, Citation2013) were also adopted. Mahboob and Golden (Citation2013) highlighted the importance of the comparative approach in identifying differences and gaps between regions, thereby enabling a discussion on the role of historical context, for example in shaping the extent of discriminatory practices in teachers’ job ads across different regions.

The previous institution information (institution type and geographic location) were coded in a straightforward manner to explore similarities and differences between institutions and regions. Nevertheless, two studies (Hales & Clarke, Citation2016; Nuttall et al., Citation2013) took a deeper look into institution descriptions by analysing institutional statements included in teacher educator job ads that provide information on the priorities, goals and culture of the institutions. Hales and Clarke (Citation2016) observed that the majority of the teacher educator job advertisements included parts to entice potential applicants by presenting information on (1) culture/work environment and (2) organisational goals and priorities. In the first category to describe university-wide and departmental work culture, “terms such as ‘collaborative,’ ‘vibrant’, ‘dynamic’, ‘forward looking’ and ‘poised for significant growth’ were employed” (p. 328). Organisational goals and priorities were observed focusing “mainly on teaching, academic research and community outreach. Specific commitment to teacher education programming and instructions appeared in three advertisements [out of 30 postings examined]” (p. 328). Correspondingly, Nuttall et al. (Citation2013), noted that the few times it was mentioned that a university offered teacher education, it “tended to take secondary position” in the ads (p. 334). According to their description, institutional statements, such as “producing research ‘output’ that is ‘ranked above world standard’” and an invitation for “applicants to ‘make a significant impact nationally and internationally’” (p. 334), are typical job advertisement discourse and provide clear evidence of the marketisation process: the intention with job advertisements is not only to recruit personnel but also to market the institution.

4. Discussion

In this scoping review, a structured overview of research using teacher or teacher educator job advertisements as primary data has been provided. Despite the slight increase of interest in this area of research in recent years, the attention directed at investigating teacher and teacher educator job ads is still relatively low compared to other fields, where job ads have been described as an appealing and commonly used source for research (e.g. Kim & Angnakoon, Citation2016; Mahjoub & Kruyen, Citation2021) mainly because of the easily accessible, organic and practical nature of the data (Harper, Citation2012). Yet, collectively, the analysis of the studies offered insights into the range of methodological approaches, such as selecting the data source and conducting sampling and analysis, and into the various research objectives that can be pursued by examining candidate, position and institution descriptions listed in the job advertisements. Although there remains considerable room for improving the methodological rigour of teacher and teacher educator job ad research, it is hoped that this review not only offers an analysis of the literature in the area, but by pointing out the methodological deficiencies it also serves as useful guidance for those seeking to conduct, publish and further develop the quality of job advertisement research in the field of education.

From an analytical point of view, three deficiencies observed from the studies need to be addressed. Firstly, theory-driven teacher and teaching competence frameworks (e.g. Baumert & Kunter, Citation2013; Metsäpelto et al., Citation2022) for examining candidate descriptions were not identified from the studies and could be applied to job ad research in the teaching field in the future. Secondly, many of the studies provided a parsimonious description of the coding and categorization processes, which lack the objective definitions for coding and authentic descriptions of interpretation and its challenges that would have helped in evaluating the reliability of the analysis. Also reporting the inter-coder reliability to express the extent of agreement among coders should be more frequently adopted in job ad studies in the field of education. Thirdly, the analysis software was only rarely exploited (or at least reported to be exploited) in studies included in this review. Computerized analysis should, however, be taken advantage of more frequently since it affords several enhancing benefits for organizing, searching, linking and retrieving the data, and therefore for making the handling of larger samples in particular more manageable and productive. Also, it is worth considering automated text analysis, also known as text mining, which offers distinct advantages over manual content analysis, including reduced time requirements and decreased need for human labour (Pejic-Bach et al., Citation2020).

From the data credibility standpoint, poor sampling decisions should be avoided by defining a clear and justified frame for sample and sources (Kim & Angnakoon, Citation2016). Development in technology has caused online media to play a major role in job advertising and, thus, has raised the importance of online job ads for researchers (Mahjoub & Kruyen, Citation2021). The results of this review indicate that the use of online sources to collect teacher and teacher educator job ads has rapidly increased since the late 2000s. This has diversified the data sources compared to the traditional way of collecting job advertisements by using newspapers, and therefore, can be considered to support the comprehensiveness and representativeness of data. However, it needs to be taken into account that, recruitment systems and websites vary widely between countries: for example, in Finland almost 80 percent of municipalities publish all their open vacancies, including positions in early childhood education, primary and secondary teachers, through the same website (https://www.kuntarekry.fi/en/), which can diminish the likelihood of sample bias. Social media platforms, such as LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter, as data sources are still arguably underutilized, although they have certain clear advantages compared to recruitment websites and newspapers, such as the fact that they are free and posting ads is time-efficient.

The sampling period needs to be cautiously designed when investigating teacher job ads in particular, since teacher recruitment is highly seasonal with most resignation and hiring activity occurring in certain months of the year. Especially in studies restricting the timeframe for data collection to a few months it would be exceedingly important to hit the busiest recruitment period, and, thus, to avoid excluding a large proportion of annual job ads because of a negligent decision on sampling period. Longitudinal approaches, such as sampling data for several years or at constant time intervals over a longer term were not recognized from the studies included, which can all be classified as cross-sectional. However, a longitudinal approach would support identifying trends and changes in teacher and teacher educator recruiting. In addition, sample size is an eternal question in job ad research. In this study the mean sample size was significantly smaller than in the comparable job ad study reviews in other fields (e.g. Harper, Citation2012; Kim & Angnakoon, Citation2016). Although it is easy to argue that studies with a small sample size (i.e. under 100 postings) could benefit from a larger sample, the sample size can actually be viewed from two angles: the clear benefit of having a large sample size is that it leads to a more accurate overall picture, but often the large sample analysis cannot be carried out in depth and in a contextual manner because of the atomistic data (Harper, Citation2012).

Although comparisons were made, for instance, based on institution information and location, other comparative perspectives were, however, not highlighted in the studies. For example, the comparison between teachers and teacher educators was not identified, although teacher educators are frequently referred to as teachers of teachers and “super teachers” (e.g. Ellis et al., Citation2012, p. 692), which could encourage this approach. However, Harper (Citation2012) points out that the data in job ads can be rather resistant to comparative analysis and producing synthesized results. When compared to rather straightforward teacher job ad studies, some of the teacher educator job ad studies can be considered more in-depth and conceptual. Especially research conducted in the international Work of Teacher Education (WoTe) project (e.g. Ellis et al., Citation2012; Gunn et al., Citation2015; Hales & Clarke, Citation2016; Nuttall et al., Citation2013) has been trying to examine how the profession of teacher educator is conceptualized. Overall, the observed difference indicates that the analysis of job advertisements can be that of broad surface structure (a manifest analysis) or of a deep structure (a latent analysis) (Bengtsson, Citation2016), i.e. “reading between the lines” and “looking for ‘leakages’” as described in the study by Nuttall et al. (Citation2013, p. 337). A latent approach could be adopted also in teacher job ad studies, in order to conduct an in-depth and conceptual analysis of institutional requirements set for teachers in first-order setting. In particular, in-depth job ad analysis focusing on early childhood education, a context rarely identified in this review, would provide valuable information to structure the field and to provide tools for the development of teacher education for early childhood education teachers.

The study not only proposes several recommendations for future research on job advertisements in the fields of teaching and teacher education, but also has practical implications. With UNESCO estimating that the world needs nearly 69 million new teachers by 2030 to meet educational goals (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Citation2016), there is a significant demand for effective and successful teacher recruitment. This study supports the development of teacher recruitment by offering valuable tools for evaluating and improving job advertisements, by providing a comprehensive view of the requirements and responsibilities of teaching professionals, and highlighting multiple perspectives from which the content of job advertisements can be designed.

The limitations of this review are connected to the risk of missing relevant studies. Although the search strategy in this scoping review was planned with care, there still remains a risk of missing relevant data—teacher educator job ad studies in particular. Hales and Clarke (Citation2016) observed that, because of what they refer to as HR-isation, there is almost a complete absence of the title “teacher educator” from teacher education job advertisements. Accordingly, various academic titles were utilized in the studies that analysed the teacher educator position. Therefore, the selection criterion for identifying studies analysing teacher educator job ads was defined to be based on the duties involved, i.e. studies had to include reference to work with pre-service teachers for them to be counted as a teacher educator job ad study, instead of simply relying on the title of the position. Nevertheless, because of the rather demanding duty-based definition, it is quite possible to miss some relevant data. In a scoping review this may cause selection bias, which, in addition, may stem from the fact that only studies written in English were included in this review.

In conclusion, we need to remind ourselves that job ads are ads (Fu, Citation2012), which may reflect a desired state rather than reality (Harper, Citation2012). In other words, job ads only indicate what the employers explicitly decide and are able to express in sometimes restricted and regulated public advertising space, and they may not represent actual hiring decisions. Therefore, interpretation of the research should be done with care. However, with awareness of the above-mentioned restrictions, job ad analysis is a tool that, combined with other research instruments, can provide a holistic view of the requirements and responsibilities of the professions. Given the centrality of the teaching work force to the well-being of our societies, more research on the recruitment of teachers and teacher educators giving weight to job ad analysis should be conducted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ville Mankki

Ville Mankki is a University Research Fellow at the Department of Teacher Education, University of Turku, Finland. His research interest and publications focus on teacher education, teachers’ professional learning and student selection in teacher education programmes. This scoping review conducted by Mankki is linked to and underpins a broader empirical research project investigating teacher competences in Finland, using extensive national teacher job advertisements data collected between 2020 and 2022.

References

- Anand, R. (2013). Gender stereotyping in Indian recruitment advertisements: A content analysis. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 8(4), 306–17. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBGE.2013.059161

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bailey, C. L., Tanner, M. W., Henrichsen, L. E., & Dewey, D. P. (2013). The knowledge, experience, skills, and characteristics TESOL employers seek in job candidates. TESOL Journal, 4(4), 772–784. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.110

- Barber, A. E. (1998). Recruiting employees: Individual and organizational perspectives. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452243351

- Barrow, L. H. (2001). An analysis of middle school preservice faculty positions. Education, 122(2), 402–407.

- Barrow, L. H. (2003). Searching for educational technology faculty. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 12(2), 143–147. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023987727296

- Barrow, L. H., & Smith, C. S. (1994, March 26–29). Analysis of college science education position announcements [conference paper]. Annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Anaheim, CA, USA.

- Baumert, J., & Kunter, M. (2013). The COACTIV model of teachers’ professional competence. In M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, & M. Neubrand (Eds.), Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers: Results from the COACTIV Project (pp. 25–48). Springer US.

- Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

- Bryce, C., Lee, R., & Mohan, J. (1991). The geographies of teacher recruitment in England and Wales: Evidence from national advertisements. Area, 23(2), 119–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20002941

- Ellis, V., McNicholl, J., & Pendry, A. (2012). Institutional conceptualisations of teacher education as academic work in England. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(5), 685–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.02.004

- Fu, X. (2012). The use of interactional metadiscourse in job postings. Discourse Studies, 14(4), 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445612450373

- Gunn, A. C., Berg, D., Hill, M. F., & Haigh, M. (2015). Constructing the academic category of teacher educator in universities’ recruitment processes in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Journal of Education for Teaching, 41(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2015.1041288

- Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., Kirk, S., & Wray, K. B. (2015). The role of google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE, 10(9), e0138237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

- Hales, A., & Clarke, A. (2016). So you want to be a teacher educator? The job advertisement as a construction of teacher education in Canada. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(4), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2016.1193842

- Harper, R. (2012). The collection and analysis of job advertisements: A review of research methodology. Library and Information Research, 36(112), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.29173/lirg499

- Kim, J., & Angnakoon, P. (2016). Research using job advertisements: A methodological assessment. Library & Information Science Research, 38(4), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.11.006

- Lasseter, D. J., & Ryndak, D. L. (1998, March 25–28). A discussion of the roles of institutions of higher education in meeting the needs of schools in rural areas [conference paper]. American Council on Rural Special Education,

- Mackenzie, L. (2021). Discriminatory job advertisements for English language teachers in Colombia: An analysis of recruitment biases. TESOL Journal, 12(1), e535. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.535

- Mahboob, A., & Golden, R. (2013). Looking for native speakers of English: Discrimination in English language teaching job advertisements. Voices in Asia Journal, 1(1), 72–81.

- Mahjoub, A., & Kruyen, P. M. (2021). Efficient recruitment with effective job advertisement: An exploratory literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 24(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOTB-04-2020-0052

- Metsäpelto, R. L., Poikkeus, A. M., Heikkilä, M., Husu, J., Laine, A., Lappalainen, K., Lähteenmäki, M., Mikkilä-Erdmann, M., Warinowski, A., Iiskala, T., Hangelin, S., Harmoinen, S., Holmström, A., Kyrö-Ämmälä, O., Lehesvuori, S., Mankki, V., & Suvilehto, P. (2022). A multidimensional adapted process model of teaching. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 34(2), 143–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-021-09373-9

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nuttall, J., Brennan, M., Zipin, L., Tuinamuana, K., & Cameron, L. (2013). Lost in production: The erasure of the teacher educator in Australian university job advertisements. Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2013.799849

- Oraison, H. M., Konjarski, L., & Howe, S. T. (2019). Does university prepare students for employment? Alignment between graduate attributes, accreditation requirements and industry employability criteria. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(1), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2019vol10no1art790

- Pejic-Bach, M., Bertoncel, T., Meško, M., & Krstić, Ž. (2020). Text mining of industry 4.0 job advertisements. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.07.014

- Piróg, D., & Hibszer, A. (2020). The situation of geography teachers on the labour market in Poland: Overt and covert issues. European Journal of Geography, 11(2), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.48088/ejg.d.pir.11.2.65.87

- Rios, J. A., Ling, G., Pugh, R., Becker, D., & Bacall, A. (2020). Identifying critical 21st-century skills for workplace success: A content analysis of job advertisements. Educational Researcher, 49(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19890600

- Ryndak, D. L., & Sirvis, B. (1999). Advertisements for faculty with expertise in severe or multiple disabilities: Do they reflect initiatives in teacher education and school reform? Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 22(1), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/088840649902200103

- Ryndak, D. L., Webb, K., & Clark, D. (1999). Faculty advertisements: A road map for future faculty. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 22(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/088840649902200104

- Selvi, A. F. (2010). All teachers are equal, but some teachers are more equal than others: Trend analysis of job advertisements in English language teaching. WATESOL NNEST Caucus Annual Review, 1(1), 155–181.

- Sims, W. L., Jeffs, K. C., & Barrow, L. H. (2010). Help wanted: Music education positions in higher education, 2007–2008. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 20(1), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083710363386

- Stephenson, J., & Carter, M. (2014). What do employers ask for in advertisements for special education positions? Australasian Journal of Special Education, 38(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2014.3

- Talmo, T., Soule, M. V., Fominykh, M., Giordano, A., Perifanou, M., Sukacke, V., Novozhilova, A., D’Ambrosio, R., & Elçi, A. (2020). Digital competences for language teachers: Do employers seek the skills needed from language teachers today? In P. Zaphiris & A. Ioannou (Eds.), Learning and collaboration technologies. Designing, developing and deploying learning experiences. HCII 2020. Lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 12205, pp. 399–412). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50513-4_30

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Twombly, S. B., Wolf-Wendel, L., Williams, J., & Green, P. (2006). Searching for the next generation of teacher educators: Assessing the success of academic searches. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(5), 498–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487106292722

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2016, October). The world needs almost 69 million new teachers to reach the 2030 education goals. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000246124

- Yaman, İ., & Şahin, M. (2019). An investigation into the employment of English language teachers in the private sector in Turkey. Journal of Language Research, 3(1), 1–13.