Abstract

The present study has attempted to study the effects of depression, mental distress, and sleep disorders among students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stress, mental distress, depression, sleep disorders, headaches, loneliness, screen fatigue, and high distress levels are common symptoms observed across the population. The study focused on the students of higher education who have been attending online classes since the inception of COVID-19 virus. The detailed questionnaire was circulated online to 450 students, out of which 323 responded. After filtering the incomplete responses, 286 sample sizes were taken into consideration. The data were analysed using SPSS software, and hypotheses and model testing were performed using the AMOS software. A significant relationship was found between depression, distress, sleep disorders, and student behaviour. Loneliness, lack of physical interaction, and overexposure to screens were found to be major trigger elements affecting students’ mental health. To dilute the effect on students’ behaviour and enhance their mental health, the authors recommend taking precautionary measures by the concerned stakeholders.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The COVID-19 pandemic has left no one unscathed. In some way or the other, every individual has been deeply impacted by this virus. One of the safety measures adopted by the Government was Lockdown, which compelled the student community to resort to online mode of teaching and learning. This paper strives to study the impact of sleep disorders, mental distress, and depression on the students of higher education, while they were isolated. During the course of this study, it was observed that a) isolation, b) very limited or complete absence of any form of physical interaction and c) inflated screen time were found to be the fundamental factors affecting the mental and emotional wellbeing of the students. In this paper, the authors have also suggested certain measures to enhance the mental health of such students.

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus poses a unique challenge for one of the most populous countries with a wide income and social disparity, inadequate medical infrastructure, and diverse lifestyles, which makes the situation more complicated (Golechha, Citation2020). The virus that originated in Wuhan was first detected on 30 January 2020, in India, and within a few months, engulfed the whole nation (Singh et al., Citation2022; Mandala et al., Citation2022). To control the spread of the virus, India went into lockdown on 25 March 2020 (Pawar et al., Citation2020). This disrupted the existing business models as people were confined to their homes with limited access to various services and the economy suffered a lot.

Lockdown, which results in forceful confinement of people to their homes to reduce the spread of infection, can significantly affect the physical and mental health of people (Wang et al., Citation2020). Isolation from society, friends, and family members can trigger anxiety, fear, loneliness, and depression among individuals (Zhou et al., Citation2020). This forces people to spend more time in front of screens, which further leads to sleep disorders, reduction in physical activity, and mental imbalance. In a survey conducted among the residents of Wuhan, it was found that post-traumatic stress disorder was very high among the residents post COVID. Those who exercised regularly and slept properly reported less post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Liu et al., Citation2020) (See Figure ).

A sedentary lifestyle coupled with excessive exposure to screen led to the development of fatigue, anxiety, and sleep disorders among the population. The younger generation made excessive use of Internet-based devices to reduce their social isolation, which led to sleeping disorders (Orzech et al., Citation2016). The tendency among the young population to use social media for longer durations affects their sleeping patterns and causes anxiety and restlessness (Sivertsen et al., Citation2019). The rise in stress level is a critical factor that affects efficiency and severely impairs attention span (Verma, Citation2023). The emotional well-being of students directly affects their behaviour, self-esteem, educational growth, attendance in class, social life, and mental health (Rao, Citation2001). Students with good mental health possess better problem-solving skills, have a sense of purpose, and lead productive lives (Nintachan, Citation2007).

This study attempted to measure the increase in distress level among students due to COVID pandemic and the various factors that acted as a trigger point for enhancing their stress level. Researchers have attempted to cover both the physical and emotional well-being of the sample population and to fill the gaps found in existing research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Student’s behaviour

The COVID-induced lockdown created an atmosphere of uncertainty about their future academic and career prospects, making them prone to stress (Singh, Citation2020, Verma, Verma, Boaler, et al., Citation2022). There was a significant change in the behaviour and attitude of the students before and after the pandemic. The pandemic forced students to shift their attention from academics to other essential things, such as personal hygiene and social distancing (Meijer & Webster, Citation2020). Students’ inability to cope with e-learning and fear of academic year loss caused behavioural changes among students (Hasan & Bao, Citation2020; Verma, Verma, Boaler, et al., Citation2022). Academic pressure had a negative impact on the emotional well-being of students, which led to an increase in depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders (Bedewy & Gabriel, Citation2015). This paper attempts to measure the relationship between sleep disorders, mental distress, and depression on students’ behaviour during a pandemic.

2.2. Sleeping disorder

Sleep is considered an essential requirement for the human body and plays a vital role in the restoration of physiological and psychological health of human being (Leeder et al., Citation2012). Sleeping behaviour is directly related to biological functions, such as the immune system, restoration of tissue, boosting memory, and balanced metabolic activity (Erlacher et al., Citation2011). Getting enough rest and sound sleep are considered essential for managing fatigue and full body recovery (Robson-Ansley et al., Citation2009). COVID outbreaks significantly impacted the sleeping pattern of the population. Cellini et al. (Citation2020) measured the changes in sleeping patterns, time management, and use of digital devices in 1310 young adults and found an increase in the use of digital devices during sleep. It was also found that during the pandemic, people used to go late to bed and woke up later and had a poor quality of sleep (Zhou et al., Citation2020). There were high levels of sleep problems among young adults during COVID pandemic.

In line with previous research, the following hypothesis has been formulated.

H1a:

Insomnia is positively related to students behaviour

H1b:

Headache is positively related to student’s behaviour

H1c:

Restlessness is positively related to student’s behaviour

H1d:

Time Management is positively related to student’s behaviour

2.3. Depression

The ambiguous nature of the virus and subsequent lockdowns have triggered major psychological effects on the population, which have forced them to suffer from depression, anxiety, and stress disorders (Bao et al., Citation2020, Zandifar et al., Citation2020). People were terrified because they lacked a coping strategy for the pandemic (Mazza et al., Citation2020). Students were considered the most vulnerable group in society who suffered from anxiety, depression, and high stress levels during the pandemic (Lee, Citation2020). Previous researchers have studied students’ anxiety levels, depression, and stress and analysed the various factors that have a direct effect on students’ mental health.(Khoshiam et al., Citation2020) Closure of colleges and cancellation of examinations negatively impacted the career prospects of students, which further pushed them towards anxiety and depression. Depression is commonly accompanied by chronic pain and PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress disorder) (Poundja et al., Citation2006). Based on the above literature review, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H2a:

Lack of Focus positively related to student’s behaviour

H2b:

Nervousness is positively related to student’s behaviour

H2c:

Negativity in positively related to student’s behaviour

H2d:

Suicidal tendency is positively related to students’ behaviour

2.4. Mental distress

COVID-19 induced psychological factors that could lead to potential mental distress among the population. Discrimination arising from COVID is a potential cause of depression (Finch et al., Citation2000) and has been proven to be linked to mental distress in SARS research (Peng et al., Citation2010). Mental distress (e.g., anxiety, panic, and emotional disturbances) is linked to depression. Moreover, students worry about the loss of their academic year because online education is not accessible to all students. A high poverty level also hinders online education as a significant percentage of students do not have access to computers . These factors lead to distress among students, which, in the long term, is related to PTSD.

Hence, the following hypothesis has been proposed

H3a:

Study load is positively related to student’s behaviour

H3b:

Mental Tension is directly related to student’s behaviour

H3c:

Concentration is positively related to student’s behaviour

H3d:

Decision-making is positively related to student’s behaviour

3. Methodology

To measure the impact of the COVID pandemic on the behaviour of students, previous research was analysed and an online questionnaire was developed. To determine the validity of the questions, a panel of experts comprised academicians, parents, research scholars, and psychiatrists. The suggestions given by the panel were duly incorporated, and the questions were circulated among students from diverse educational institutes. A Likert scale was used to measure the responses. Demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and educational qualifications, were included in the survey. It was circulated among 450 students, out of which 323 responded. After filtering the incomplete responses, 286 sample sizes were taken into consideration.

3.1. Analysis of data

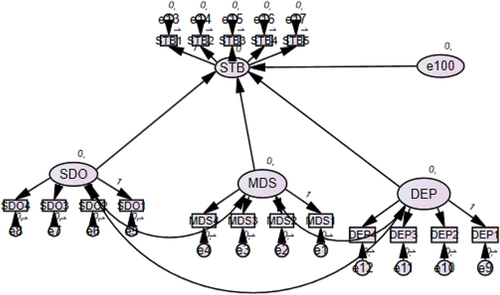

The data analysis was performed in various steps. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to determine the constructs and measure their impact. Then, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to perform convergent and discriminant validity tests, and finally, structural equation modelling was used to test the hypothesis (Table ).

Table 1. Socio-demographic profile

3.2. Measurement model

To test the adequacy of the sample and appropriateness of the data, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were performed. The KMO value was 0.758, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity value was 0.00, indicating that the data were appropriate for further analysis. The minimum acceptance value for the KMO test was 0.5 (Field, Citation2000; Kaiser, Citation1974). To test the reliability of the questionnaire, a Cronbach’s alpha test was performed for each construct (see Table ). The value for constructs lies within the range of 0.645–0.803, which is above the acceptable limit of 0.6 (Kerlinger & Lee, Citation2000). IBM SPSS version 26 was used to perform the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Factor loading, varimax rotation, and an eigenvalue >1 were used to perform the EFA (Kaiser Citation1958). Indicators with factor loadings less than 0.7 were removed to improve the accuracy. Indicators STB 4 and STB 5 had values below the desired level and were thus eliminated from the list (Table ). To perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), AMOS 26 was used. In Table , the AVE (average variance analysis) values for the constructs were above 0.5 and the CR (combined reliability) was above the standard limit of 0.7 which indicated significant convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The discriminant validity values of the constructs were lower than the square root of the AVE, which justified the acceptance of the test results (Fornell & Larcker Citation1981) Refer Table . The hypotheses were tested using a Structural Equation Model (SEM) with AMOS 26. These hypotheses were considered acceptable if p values were <0.5 were considered acceptable, whereas those with p values above 0.5 were rejected. Refer Table .

Table 2. Construct, indicator, Cronbach’s Alpha, mean, standard deviation

Table 3. Factor loading of constructs

Table 4. Average variance and construct reliability

Table 5. Discriminant validity test of constructs

Table 6. P-value

4. Major findings

4.1. Socio-demographic profile of respondents

A total of 323 students participated in the study, of which 286 responses were considered. The respondents included males and females in equal proportions, and the majority of the age group was between 20 and 30 years. About 10.2% of the students were below 20 years, and 7.6% students were above 30 years. The majority (83.5%) of the students were pursuing graduation, while 14.6% were pursuing Post Graduation. All the students were unmarried, 64% of the students were pursuing online education through mobile phones, and 32% were using broadband Internet connection.

4.2. Sleeping disorder

Hypothesis H1a revealed that the majority of the students had sleeping disorders (β = 0.31 p < 0.05). About 43.7% of the students said that they suffered from insomnia and were unable to sleep for more than 6 hours on account of extended use of cell phones and laptops for attending online classes and assignment submission.

The reason could be prolonged lockdown, which resulted in decreased energy levels and new academic patterns induced by COVID (Giusti et al., Citation2020). Hypothesis H2b revealed that there was no significant relationship between headaches and student behaviour. Only 16.4% of students said that they suffered from frequent headaches. Hypothesis H2c revealed a significant relationship between restlessness and student behaviour (β = 0.68 p < 0.05). Restlessness was found in 42.9% of the students, reasons may be lack of physical mobility, and online education would have led to increased restlessness and fatigue (Al-Tammemi et al., Citation2020). Hypothesis H2d revealed that there is a significant relationship between time management and student behaviour. About 46.7% of the students said that they were facing issues with time management and were unable to submit their assignments on time (β=−0.79 p < 0.05). The reasons may be disruption in the daily routine of students due to lockdown and inadequate Internet connectivity, which has led to poor time management among the student community (Horita et al., Citation2021).

4.3. Mental distress

Hypothesis H2a revealed that the study load has a significant and positive influence on student behavior (β = 0.23 p < 0.05). The study revealed that majority (45%) of the students believed that study load had increased during pandemic. The reason may be that students tend to lose concentration due to prolonged exposure to screen, which gives rise to stress in their minds (Giusti et al., Citation2020). Hypothesis H2b revealed that there was no significant relationship between COVID and mental tension among students. Hypothesis H2c revealed that there was no significant relationship between students’ concertation and student behaviour. Hypothesis H2d revealed that there is a significant relationship between decision-making and student behaviour. About 38.8% students found difficulty in decision-making (β = 0.79 p < 0.05). The reason may be that they face difficulty arriving at any concrete decision as their frame of mind is disturbed, which affects their performance. The test results showed that online classes are cumbersome and passive, leading to an excessive study load. (Khawar et al., Citation2021)

4.4. Depression

Hypothesis H3a revealed that most students suffered from Depression during the COVID Pandemic. Forty-seven per cent of the respondents said that they often felt that they are not unable to think clearly (β = 0.84 p < 0.05). The reason for the lack of focus was lockdown, which restricted their interaction with peers, and the monotonous nature of online education, which did not meet their expectations (Khawar et al., Citation2021). Hypothesis H3b revealed that nervousness has a significant relationship with student behaviour. Forty-nine per cent of the students revealed that they became nervous, as they were not able to meet their study commitments (β = 0.74 p < 0.05). This may be due to the prolonged stay at home without any social and physical movement and face-to-face interaction with their classmates and teachers’ students, who reported high levels of depression (Islam et al., Citation2020). Hypothesis H3c revealed that negative feelings have a significant relationship with student behaviour. The majority (42.4%) complained about developing negative feelings during the lockdown (β = 0.79 p < 0.05). This increased pessimistic behaviour may be due to constant staying at home, scary news about pandemics, and fear of being infected. Hypothesis H3d revealed that suicidal tendencies have a significant relationship with student behaviour. Suicidal tendencies were found in 33% of the students (β = 0.46 p < 0.05). This result can be attributed to loneliness and a lack of emotional support from their social circles. Since they were not having physical access to their peer groups and friends, they were unable to share their feelings which build up the feeling to loneliness among them (Pramukti et al., Citation2020).

5. Discussions & implications

The present study focused on the relationship between sleep disorders, mental distress, depression, and student behaviour during COVID pandemic. Various studies have shown that previous pandemics such as flu, influenza, and Sars have a significant impact on the mental status of the general population, including students (Bao et al., Citation2020; Cao et al., Citation2020; Dong & Bouey, Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2004). The current study revealed that depression, sleep disorders, and mental distress significantly impacted the behaviour of students during the pandemic.

The study revealed that sleep disorders were prevalent among students during the lockdown. During the lockdown, the movement of the students was restricted, and the time spent in front of the screen increased significantly, which severely impacted their sleeping patterns. The blue light emitted from the screen leads to the suppression of melatonin hormones, which aid in inducing sleep in humans (Calvo-Sanz & Tapia-Ayuga, Citation2020; Christensen et al., Citation2016). Research conducted by Vallance et al. (Citation2015) and Wu et al. (Citation2017) revealed that exposure to blue light emitted from digital devices can significantly reduce sleep duration in adults and children. The study found that the majority of students did not complain about headaches because of an increase in screen timing. Çaksen (Citation2021) revealed that excessive use of digital devices leads to frequent complaints of headaches and backaches among children. However, in our study, the relationship between screen time and headaches was not established. Restlessness, loss of appetite, and sleep disorders have been reported among college students. The students complained about restrictions and were eager to return to their physical classes (Birmingham et al., Citation2021). Mental tension and reduced concentration among students did not significantly affect student behavior. The mental framework of the students was severely affected by the lockdown during the pandemic. The students complained of fatigue, despair, anxiety, and boredom (Tümen Akyildiz, Citation2020). The lack of communication and physical interactions further reduced efficiency. Previous studies have revealed that the level of anxiety and mental stress is not affected by gender, year of study, current place of residence, or monthly income of the family (Saraswathi et al., Citation2020). Similarly, in a comparative study of mental stress, anxiety, and depression levels amongst the students, during the course of pandemic in 2020, 2021, and 2022, it was found that the level of stress and depression was found to be similar in 2021 and 2022. The level of anxiety was found to be highest in 2022 followed by 2021 and least in 2020 (Kavvadas et al., Citation2023). On the contrary, depression was found to be marginally high among the students in pre-pandemic period, while the anxiety level was on a higher scale during the pandemic in comparison to pre-pandemic level (Zhang et al., Citation2022). Interestingly, another study revealed that students became more resilient and adaptive with enhanced coping mechanism post pandemic (Janssen & van Atteveldt, Citation2023). Online teaching pedagogy and fear of loss of academic year also contributed to stress level among the students (Hasan & Bao, Citation2020).

There was a significant increase in the elements of depressive symptoms among the students’ post-lockdown. Home confinement, mental distress, and anxiety have been identified as major contributors to depressive symptoms. A lack of focus and concentration was found to be prevalent among the students, which acted as a stepping stone for depression. Remote learning, financial problems, and uncertainty were the main causes of anxiety and nervousness among students (Sundarasen et al., Citation2020). Students were forced to undergo several lifestyles changes due to the closure of schools and colleges. These gave rise to mental problems and propagated a feeling of negativity among them. A study carried out on Chinese children revealed that their mental health was severely impacted by the COVID-19 Pandemic and which significantly increased their depressive symptoms (Xie et al., Citation2020). Prolonged periods of isolation and confinement also lead to the development of suicidal tendencies among the population. Insomnia was also found to contribute to suicidal tendencies (Pompili et al., Citation2013).

6. Conclusion and future research

Apart from previous research, this paper has attempted to study the impact of COVID-19 on the behaviour of students and has established that the pandemic has led to an increase in depression, anxiety, and mental distress among students. The paper formulated three constructs—sleeping disorder, mentaldistress, and depression—and a detailed questionnaire was circulated among the students. To test the reliability of the proposed construct’s Cronbach’s alpha, the KMO Bartlett test, factor analysis, and Discriminant Validity tests were performed. The hypotheses and model were tested by conducting CFA. The study concluded that insomnia, restlessness, time management, lack of focus, nervousness, negativity, suicidal behaviour, study load, and decision-making have a significant impact on students’ behaviour, while tension, concentration, and headache have negative impacts on students’ behaviour. Lock down, though an effective measure to control the spread of the virus, has a significant impact on the lives of students. Sleeping disorders, mental distress, and depression were found in the majority of students. Sleeping disorders and lack of physical interaction play a role in the mental balance of the students, and our paper explores the various aspects of the students’ behaviour during the pandemic.

This study can be very useful for educational institutions, psychiatrists, and parents in monitoring students in Asian Countries. The authors suggest that concerned authorities should explore the option of imparting counselling sessions through offline and online modes to students so that it may prevent the deterioration of their mental health. Teachers need to adopt a more empathetic approach while interacting with students and try to reduce their academic pressure. Mentoring sessions should be organized on a regular basis, which will help students to express their feelings and keep a check on their academic progress. Academic institutions should also attempt to modify the syllabus to reduce students’ onscreen time.

Although the study has many merits, it also has some limitations that can be extended in the form of future research. The sample size of the study was small, and it can be increased for a better analysis. One of the major limitations of the paper is that the study was completely based on a cross section of students in India. Likewise, the synthesized respondents were typically young adults. Hence, it shall not be appropriate to generalize this study’s findings to people belonging to all ethnic groups and demographic profile. However, further research can be carried out in terms of people belonging to various demographic profiles such as “Impact of the pandemic on married and unmarried students.” Aligning this study with the number of family members present at home during the lockdown and their living standards and financial conditions could also be explored in the future research. Also, since the questionnaire was in English, we could not cover students from rural areas due to language barriers. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the impact of COVID on students, it is recommended that questions be framed in vernacular languages

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Meenakshi Verma

Meenakshi Verma has served as a reviewer for various journals listed in ABDC and Scopus. She has conducted FDP on Research Methodology and Systematic Literature review for Research Scholars and Faculty members. She has five papers listed in Scopus, one in Web of Science, and six in ABDC.

Anuj Verma

Anuj Verma has served as a reviewer for ABDC and Scopus listed journals. He has published numerous papers published in six in ABDC, three in Scopus, and one in Web of Science Journals. He also published three case studies in reputed journals.

Gangu Naidu Mandala

Gangu Naidu Mandala is an avid researcher with multiple papers published in Scopus, Web of Science, and ABDC. In addition to the above, he also has numerous case studies and chapter publications to his credit.

References

- Al-Tammemi, A. A. B., Akour, A., & Alfalah, L. (2020). Is it just about physical health? An online cross-sectional study exploring the psychological distress among university students in Jordan in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 562213. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.562213

- Bao, Y., Sun, Y., Meng, S., Shi L, J., & Lu, L. (2020). Lu 2019-nCov epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society. Lancet (London, England), 395(10224), e37–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3

- Bedewy, D., & Gabriel, A. (2015). Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The perception of academic stress scale. Health Psychology Open, 2(2), 2055102915596714. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102915596714

- Birmingham, W. C., Wadsworth, L. L., Lassetter, J. H., Graff, T. C., Lauren, E., & Hung, M. (2021). COVID-19 lockdown: Impact on college students’ lives. Journal of American College Health, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1909041

- Çaksen, H. (2021). Electronic screen exposure and headache in children. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 24(1), 8.

- Calvo-Sanz, J. A., & Tapia-Ayuga, C. E. (2020). Blue light emission spectra of popular mobile devices: The extent of user protection against melatonin suppression by built-in screen technology and light filtering software systems. Chronobiology International, 37(7), 1016–1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2020.1781149

- Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

- Cellini, N., Canale, N., Mioni, G., & Costa, S. (2020). Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Sleep Research, 29(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13074

- Christensen, M. A., Bettencourt, L., Kaye, L., Moturu, S. T., Nguyen, K. T., Olgin, J. E., & Marcus, G. M. (2016). Direct measurements of smartphone screen-time: Relationships with demographics and sleep. PLoS One, 11(11), e0165331. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165331

- Dong, L., & Bouey, J. (2020). Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 26(7), 1616. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200407

- Erlacher, D., Ehrlenspiel, F., Adegbesan, O. A., & Galal El-Din, H. (2011). Sleep habits in German athletes before important competitions or games. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(8), 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.565782

- Field, A. (2000). Discovering statistics using SPSS for windows. Sage publications.

- Finch, B., Kolody, B., & Vega, W. (2000, September). Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 41(3), 295–313. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676322

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Giusti, L., Salza, A., Mammarella, S., Bianco, D., Ussorio, D., Casacchia, M., & Roncone, R. (2020). # Everything will be fine. duration of home confinement and “all-or-nothing” cognitive thinking style as predictors of traumatic distress in young university students on a digital platform during the COVID-19 Italian Lockdown. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1398. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.574812

- Golechha, M. (2020). COVID-19, India, lockdown and psychosocial challenges: What next?. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(8), 830–832. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020935922

- Hasan, N., & Bao, Y. (2020). Impact of “e-Learning crack-up” perception on psychological distress among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A mediating role of “fear of academic year loss”. Children & Youth Services Review, 118, 105355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105355

- Horita, R., Nishio, A., & Yamamoto, M. (2021, January). The effect of remote learning on the mental health of first year university students in Japan. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113561

- Islam, M. A., Barna, S. D., Raihan, H., Khan, M. N. A., Hossain, M. T., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). Depression and anxiety among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A web-based cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0238162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238162

- Janssen, T. W. P., & van Atteveldt, N. (2023). Coping styles mediate the relation between mindset and academic resilience in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 6060. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33392-9

- Kaiser, H. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575

- Kaiser, H. F. (1958). The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 23(3), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289233

- Kavvadas, D., Kavvada, A., Karachrysafi, S., Papaliagkas, V., Chatzidimitriou, M., & Papamitsou, T. (2023). Stress, anxiety, and depression levels among university students: Three years from the beginning of the pandemic. Clinics and Practice, 13(3), 596–609. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract13030054

- Kerlinger, F. N., & Lee, H. B. (2000). Foundations of Behavioral Research (4th ed.). Harcourt College Publishers.

- Khawar, M. B., Abbasi, M. H., Hussain, S., Riaz, M., Rafiq, M., Mehmood, R., & Farooq, A. (2021). Psychological impacts of COVID-19 and satisfaction from online classes: Disturbance in daily routine and prevalence of depression, stress, and anxiety among students of Pakistan. Heliyon, 7(5), e07030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07030

- Khoshaim, H. B., Al-Sukayt, A., Chinna, K., Nurunnabi, M., Sundarasen, S., Kamaludin, K., & Hossain, S. F. A. (2020). Anxiety level of university students during COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 579750. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579750

- Lee, J. (2020). Lee mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(6), 421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7

- Leeder, J., Glaister, M., Pizzoferro, K., Dawson, J., & Pedlar, C. (2012). Sleep duration and quality in elite athlete measured using wristwatch autography. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(6), 541–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.660188

- Liu, C. H., Zhang, E., Wong, G. T. F., & Hyun, S. (2020). Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for US young adult mental health. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172

- Mandala, G. N., Verma, A., & Verma, M. (2022). Consumption patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Information and Optimization Sciences, 43(6), 1363–1373. https://doi.org/10.1080/02522667.2022.2122196

- Mazza C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., & Roma, P. (2020). A Nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093165

- Meijer, A., & Webster, C. W. R. (2020). The COVID-19-crisis and the information polity: An overview of responses and discussions in twenty-one countries from six continents. Information Polity, 25(3), 243-274.10.3233/IP–200006.

- Nintachan, P. (2007). Resilience and risk taking behaviour among Thai Adolescents living in Bangkok, Thailand (Ph.D). VA Virginia Commonwelath University.

- Orzech, K. M., Grandner, M. A., Roane, B. M., & Carskadon, M. A. (2016). Digital media use in the 2 h before bedtime is associated with sleep variables in university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.049

- Pawar, D. S., Yadav, A. K., Akolekar, N., & Velaga, N. R. (2020). Impact of physical distancing due to novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) on daily travel for work during transition to lockdown. Transportation research interdisciplinary perspectives, 7, 100203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100203

- Peng, E., Lee, M., Tsai, S., Yang, C., Morisky, D., Tsai, L., Weng, Y.-L., & Lyu, S.-Y. (2010, July). Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: An example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 109(7), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60087-3

- Pompili, M., Sher, L., Serafini, G., Forte, A., Innamorati, M., Dominici, G., Lester, D., Amore, M., & Girardi, P. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide risk among veterans: A literature review. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(9), 802–812. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a21458

- Poundja, J., Fikretoglu, D., & Brunet, A. (2006). The co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and pain: Is depression a mediator?. Journal of Trauma and Stress, 19(5), 747–751. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20151

- Pramukti, I., Strong, C., Sitthimongkol, Y., Setiawan, A., Pandin, M. G. R., Yen, C., Lin, C., Griffiths, M. D., & Ko, N.-Y. (2020). Anxiety and suicidal thoughts during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-country comparative study among Indonesian, Taiwanese, and Thai University Students. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(12), e24487. https://doi.org/10.2196/24487

- Rao, M. (2001). Promoting children's emotional well-being by Ann Buchanan and Barbara Hudson(Book Review). Journal of Public Medicine, 23(2), 168–169. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/23.2.168

- Robson-Ansley, P. J., Gleeson, M., & Ansley, L. (2009). Fatigue management in the preparation of Olympic athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(13), 1409–1420. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802702186

- Saraswathi, I., Saikarthik, J., Kumar, K. S., Srinivasan, K. M., Ardhanaari, M., & Gunapriya, R. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on the mental health status of undergraduate medical students in a COVID-19 treating medical college: A prospective longitudinal study. PeerJ, 8, e10164. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10164

- Singh, S., Parmar, K. S., Kumar, J., & Kaur, J. (2022). Prediction of Confirmed, Recovered and Casualties’ Cases of COVID-19 in India by Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) Models. Modeling, Control and Drug Development for COVID-19. Outbreak Prevention.

- Sivertsen, B., Hysing, M., Knapstad, M., Harvey, A. G., Reneflot, A., Lønning, K. J., & O'Connor, R. C. (2019). Suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm among university students: Prevalence study. BJPsych Open, 5(2), e26. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.4

- Sundarasen, S., Chinna, K., Kamaludin, K., Nurunnabi, M., Baloch, G. M., Khoshaim, H. B., Hossain, S. F. A., & Sukayt, A. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 and lockdown among university students in Malaysia: Implications and policy recommendations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176206

- Tümen Akyildiz, S. (2020). College students’ views on the pandemic distance education: A focus group discussion. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 4(4), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.150

- Vallance, J. K., Buman, M. P., Stevinson, C., & Lynch, B. M. (2015). Associations of overall sedentary time and screen time with sleep outcomes. American Journal of Health Behavior, 39(1), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.39.1.7

- Verma, A., Chakraborty, D., & Verma, M. (2023). Barriers of food delivery applications: A perspective from innovation resistance theory using mixed method. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 73, 103369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103369

- Verma, A., Verma, M., Boaler, M. S., & Mandala, G. N. (2022). Determinants of consumer intention towards Covid vaccination the mediating role of attitude. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 26(3), 1–20. https://www.proquest.com/openview/10ea413616b6a61657dec5710016ebad/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=38744

- Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., McIntyre, R. S., & Ho, C. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

- Wong, J. G., Cheung, E. P., Cheung, V., Cheung, C., Chan, M. T., Chua, S. E., McAlonan, G. M., Tsang, K. W. T., & Ip, M. S. (2004). Psychological responses to the SARS outbreak in healthcare students in Hong Kong. Medical Teacher, 26(7), 657–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590400006572

- Wu, X., Tao, S., Rutayisire, E., Chen, Y., Huang, K., & Tao, F. (2017). The relationship between screen time, nighttime sleep duration, and behavioural problems in preschool children in China. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(5), 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0912-8

- Xie, X., Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. [published online ahead of print 2020]

- Zandifar, A., Badrfam, R., Yazdani, S., Arzaghi, S. M., Rahimi, F., Ghasemi, S., & Qorbani, M. (2020). Prevalence and severity of depression, anxiety, stress and perceived stress in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 19, 1431–1438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-020-00667-1

- Zhang, Y., Tao, S., Qu, Y., Mou, X., Gan, H., Zhou, P., Tao, F., Wu, X., & Tao, F. (2022). The correlation between lifestyle health behaviors, coping style, and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic among college students: Two rounds of a web-based study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1031560

- Zhou, S.-J., Wang, L.-L., Yang, R., Yang, X.-J., Zhang, L.-G., Guo, Z.-C., Chen, J.-C., Wang, J.-Q., & Chen, J.-X. (2020). Sleep problems among Chinese adolescents and young adults during the coronavirus-2019 pandemic. Sleep Medicine, 74, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.001