Abstract

Affective factors, such as anxiety, are located among the obstacles that hinder language learning and can result in language learners who are resistant to language input, especially in foreign language learning contexts. Thus, the current research effort aimed at examining the level of speaking anxiety among foreign language learners (English and Arabic) at Birzeit University (BZU). It also aimed at investigating the effectiveness of using online speaking tasks on lowering the anxiety level of students whose attitudes were also surveyed towards the online learning-teaching technique. The research adopted a mixed approach to obtain data. Both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection were utilized. Quantitatively, students’ foreign language speaking anxiety was calculated using a pre-post anxiety scale before and after the treatment (online speaking tasks) in addition to using semi-structured interviews with students in the experimental group. The participating students consisted of (70) students who study English and Arabic (PAS students) as foreign languages. The findings demonstrated the presence of a high level of speaking anxiety among foreign language learners at BZU. Besides, it was revealed that there were statistically significant differences in the level of speaking anxiety between the control and experimental groups in favor of the control group (higher level of anxiety). Regarding the attitudes of experimental group students, the semi-structured interviews have shown positive attitudes towards the online speaking task experience. The interviewees have indicated that delivering speaking tasks online has made the speaking task less stressful and less anxious. Accordingly, some conclusions and recommendations were suggested.

1. Introduction

Since the 1980s, there has been a considerable change in foreign language teaching and learning research. More focus was steered toward humanistic and emotional facets. The new language research trend indicated that emotions were as significant in learning foreign languages as other cognitive abilities (Horwitz et al., Citation1986). This manifested that foreign language teachers should consider learners’ feelings and emotions in language teaching and learning. Among these affective variables and emotions is the feeling of anxiety that has been proven to escort speaking a foreign language (Idri, Citation2012). According to Brown (Citation1974) and Oxford (Citation1999), anxiety can be a real obstacle that may hinder foreign language learning. As with other language skills, speaking can be impacted by affective factors (Gardner & MacIntyre, Citation1993). Several scholars and language professionals asserted the role of affective factors in the process of teaching and learning foreign language skills, these affective variables can stand as barriers to learning foreign languages (Brown, Citation1974 and Krashen, Citation1982).

Speaking, which is the oral use of language, is a means to deliver a message or explain thoughts and feelings by formulating words. As a crucial skill, Speaking was also regarded as a communication process of constructing meaning that involves creating, obtaining, and processing information (Burns & Joyce, Citation1997; Brown, Citation2001; Thornbury, Citation2005). Throughout developing the learners’ spoken language, multiple factors should be considered by foreign language teachers as this skill is consisted of complex aspects and has multiple affective factors that interfere all along the process, such as self-confidence, motivation and anxiety (Krashen, Citation1982). Anxiety indicates the emotional state that can be defined as “the subjective feeling of tension, apprehension, nervousness and worry associated with an arousal of the autonomic nervous system.”(Horwitz et al., Citation1986, p. 125). Thus, the interaction between foreign language learning and anxiety can lead to a type of anxiety known as Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA). When learners of a foreign language feel worried or stressed out about learning and using a foreign language their negative feelings are usually urged leading to the FLA (P. D. MacIntyre, Citation1999). Foreign language speaking anxiety has been also considered a major factor that can negatively impact oral production and communication. It has also been listed as one of the most obvious obstacles faced by speakers of foreign languages (Arnold, Citation1999; Alsowat, Citation2016; Abrar, Citation2017; Ariyanti, Citation2017; Bashori et al. Citation2020; Male, Citation2018). Hence, this paper attempts to highlight

Anxiety that foreign language speakers may experience has been attributed to multiple causes and factors. According to Nevid et al. (Citation2005), it was stated that anxiety can be triggered by sensitivity and low self-efficacy. Horwitz (Citation2010) also revealed that learners’ shyness, fear of public speaking, fear of judgments and test anxiety can be listed as the top factors that may lead to this barrier. Fear of foreign languages speaking, moreover, can be caused by some reasons divided into internal and external factors. As for internal reasons, low self-esteem, shyness, fear of making mistakes and demotivation were the main affective factors that can result in anxious foreign language speakers. Regarding the external factors, the learning environment, lack of readiness and methods of teaching were listed among the contextual obstacles that triggered anxiety among learners (Male, Citation2018, Quyen et al., Citation2018; Oteir & Al-Otaibi, Citation2019). Hence, it was recommended that foreign language educators should strive to devise trends that assist in minimizing the effects and consequences of this issue (Oteir & Al-Otaibi, Citation2019).

Technology and online educational platforms started to be blended excessively in teaching, especially after the switch to online learning during the COVID-19 crisis. In the context of foreign language teaching, technology and Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) were conceived by many educators as promising alternative options that can promote foreign language and learners’ language skills, particularly speaking skills (Bibauw et al., Citation2015; Mohammed, Citation2022; Peeters & Ludwig, Citation2017). Besides, technology can have a significant role in motivating learners and decreasing their level of anxiety while speaking a foreign language. Shams, (Citation2006) stated that online technological aid can decrease FLA by offering foreign language speakers the opportunity to set their own personal learning pace hence feeling they have taken their learning activities under control. Ataiefar and Sadighi (Citation2017) emphasized that using technology and remote teaching can increase learners’ fluency and oral production. It was also confirmed by De Vries et al. (Citation2015) and Mohammed (Citation2022) that CALL technologies can foster speakers’ oral skills and facilitate their fluency.

In respect of foreign language speaking anxiety (FLSA), integrating technology in the context of foreign language speaking anxiety was asserted as a significant technique in previous studies. Bashori et al. (Citation2020), for example, conducted a study to investigate the presence of foreign language speaking anxiety among Indonesian students during speaking English and examined the effect of utilizing web-based language learning (Automatic Speech Recognition). Ataiefar and Sadighi (Citation2017) also performed a study that focused on enhancing English as a foreign language (EFL) learners’ communicative oral skills by minimizing foreign language speaking anxiety. Besides, Gruber and Kaplan-Rakowski (Citation2022) investigated the potential effect of virtual reality (VR) that stimulated real-life experiences to amplify foreign language anxiety. The findings revealed a significant regression in the degrees of speaking anxiety associated with the VR technology in contrast with the Zoom sessions. In addition to that, Grieve et al. (Citation2021) carried out a qualitative study that aimed at collecting insights into anxiety faced by students while performing their presentations using a foreign language. It has been asserted that anxiety can hinder oral production and impair the speaking skill of foreign language speakers, so anxious speakers are less able to speak fluently and communicate interactively (Wörde, Citation2003).

More studies were conducted in the last few years that highlighted the impact of online speaking tasks and the use of distance technological tools on foreign language speaking anxiety and other learning aspects. Pan et al. (Citation2022) carried out a study that investigated the effectiveness of massive open online courses (MOOC) on lowering foreign language speaking anxiety, learning motivation and learning attitude. The results revealed the positive impact of MOOC courses concerning foreign language speaking anxiety, motivation and learning attitude. Besides, Hanafiah et al. (Citation2022) investigated the impact of CALL on vocabulary learning, speaking skills and foreign language speaking anxiety. The findings showed that the experimental group, which was taught using CALL programs, outflanked the control group with less amount of speaking anxiety. In the same sense, Yuan (Citation2023) investigated how foreign language classroom anxiety was lowered while foreign language learning enjoyment was enhanced by the online learning process during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, Alamer et al. (Citation2023) studied how using What’s App can increase language students’ self-motivation and achievement and decreases foreign language learning anxiety. This study along with previous ones asserted the impact that technology and online programs can have on reducing foreign language learning and speaking anxiety.

Although addressing foreign language speaking anxiety (FLSA) among researchers and language instructors was investigated previously (Aydin, Citation2016; Dewaele et al. Citation2008; Kruk, Citation2018; Luo, Citation2012; Sammephet & Wanphet, Citation2013; Yoon, Citation2012; Yamini & Tahriri, Citation2006) most of the previous studies focused merely on revealing the causes and factors of foreign language anxiety. Besides, others investigated the effect of foreign anxiety on the willingness to speak and on the learners’ motivation (Horwitz etal., Citation2010; Liu & Huang, Citation2011). In a sense, the current study is a significant research effort since few studies examined foreign language speaking anxiety (FLSA) by blending remote online speaking tasks for lowering the students’ level of anxiety. Therefore, the novelty of the current research effort sprang from the importance of investigating the effect of a teaching technique that integrated distance learning in delivering the speaking task to reduce learners’ anxiety. Besides, after the COVID-19 lockdown, researchers have been interested in examining the effectiveness of using online learning platforms in foreign language teaching, as using technology has become inseparable after the pandemic. Online educational platforms and blended learning have become an integral part in the educational process in different educational institutions around the world. Thus, investigating the effectiveness of remote speaking activities based on online platforms falls in this significant dimension.

Facing less anxiety while speaking a foreign language may have a positive impact on EFL learning attitudes. Attitude was defined as “an evaluative reaction to some referent or attitude object, inferred on the basis of the individual’s beliefs or opinions about the referent” (Gardener, Citation1980,p.9). Sauvignon (Citation1976, p.295) argues that “attitude is the most important factor in second language learning”. Hence, learners ’attitudes have a significant place in learning a foreign language. Based on (Weinburgh, Citation1998) there is a strong relation between attitude and learner’s behavior. In addition, attitude can impact learners’ achievement and success (Schibeci & Riley, Citation1986). Thus, foreign language speakers’ attitudes were explored in this study to find any possible correlation between the online remote speaking tasks and EFL learning attitudes.

Thus, this study aimed to examine the effectiveness of using distance speaking tasks and activities, through online educational platforms, on the level of anxiety of students who studied Arabic and English as foreign languages in comparison with face-to-face speaking activities. It also researched students’ attitudes towards the teaching technique (online speaking task).

2. Statement of the problem

According to P. MacIntyre and Gregersen (Citation2012), foreign language anxiety is one of the major affective factors that is responsible for hindering an appropriate, smooth and fluent use of the foreign language. Foreign language speakers who usually feel stressed out and anxious while speaking foreign languages are likely to fall in grammatical mistakes or misuse vocabulary items. This can ultimately lead to weak communication with others, in addition to the feeling of lack of self-confidence and self-esteem in using a foreign language. Consequently, such learners will be reluctant to speak the foreign language frequently and so will hide away. In this sense, technology and online platforms can offer a functional and feasible resolution for many foreign language speakers. These online platforms can reduce negative emotions like tension, embarrassment and panic which usually correspond with face-to-face foreign language speaking.

3. Questions of the study

The current study aimed at answering the following questions:

To what extent do BZU students have foreign language speaking anxiety?

Are there any statistically significant differences (at α = 0.05) in students’ speaking anxiety degree that can be attributed to the teaching technique (using Online speaking tasks versus in-class oral presentations)?

What are students’ attitudes toward using online speaking tasks in teaching foreign languages?

4. Method

This current study aimed at investigating the anxiety level of speaking a foreign language among students, and it targeted examining any significant differences in students’ speaking-anxiety levels that can be attributed to the teaching method; online speaking tasks versus in-class-oral presentations. To answer the study’s questions, quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection were followed in a mixed approach (Creswell, Citation2014). To this end, the researcher adopted a quasi-experimental design consisting of measuring participants’ degrees of anxiety which were obtained through the implementation of a scale for foreign language anxiety before and after the treatment.

Besides, the current study examined students’ attitudes in the experimental group toward using online speaking tasks. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with (7) students from the experimental group to uncover their attitudes toward the new treatment of online speaking tasks.

5. Participants

This study was conducted in the first semester of the academic year 2022–2023. A total of (70) BZU students, who were studying English and Arabic as foreign languages, were selected randomly to participate in this experiment. As for the participating students who studied Arabic as a foreign language, they were selected from the Palestine Arabic Studies (PAS) program at BZU. It is worth noting that in the PAS program, only international students from different cultures can be enrolled to learn about the Palestinian culture and language (Arabic). As mentioned earlier, two mixed-gender groups were randomly selected from the researchers’ classes at Birzeit University. The participants were first-year university students and have enrolled both in the Unlock instructional program intermediate courses (A2 and B1) and the PAS program in the first semester of 2022–2023. They consisted of (70) students, from different specializations and disciplines. The experimental group consisted of (31) students and the control had (39) students. Of course, both groups have previous basic experience with online learning, which was implemented at schools during the lockdown period. As for the qualitative data, obtained data were collected by exploring the attitudes of (7) students in the experimental group towards utilizing the online speaking tasks.

The students in the experimental and control groups had to respond to the pre and post-foreign language anxiety scale to measure their anxiety degrees before and after the treatment. The experimental group was taught to practice their speaking skill and send the speaking tasks online.

6. Data collection

Data collection was obtained quantitatively and qualitatively following a mixed approach. As for the quantitative data, they were obtained through the implementation of a scale for foreign language anxiety before and after the treatment. Regarding the treatment, the participating students in the experimental group were asked to perform and submit the speaking tasks online.

In contrast, students in the control group were asked to conduct in-class oral presentations. After accomplishing these two methods, students were asked to respond to the same scale regarding foreign language anxiety. Data obtained from the pre-and post- anxiety scale were calculated and compared statistically to answer the research questions. As for the foreign language anxiety scale used in the current study, it was adapted based on the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) developed by Horwitz et al. (Citation1986). In terms of the qualitative data, semi-structured interviews were conducted with (7) students from the experimental group who were selected randomly.

7. The instructional strategy

To achieve the study’s purpose, the researchers designed an instructional speaking strategy for teaching students speaking skills, but instead of delivering speaking tasks in class, they had to do their oral presentations online. The assigned speaking tasks were short recorded videos that reflected themes in the participants’ learning material. The participants were asked to record required videos and send them through Moodle platform. The participants had to submit four online videos during this intervention. Each video reflected a theme of an educational unit in their learning material (four learning units). It is noteworthy that the participants had four speaking classes during the experiment. Students of the experimental group were given an orientation session on preparing and submitting online speaking presentations. This orientation session involved important criteria for the required videotaped presentations. On the other hand, the control group had to deliver the speaking task face-to-face in the classroom. It is noteworthy that both control group students and experiment group students were informed ahead of the required speaking tasks; therefore, they both had the chance to practice more than once before delivering the tasks.

8. Instrument validity and reliability

To set the validity of the anxiety scale, it was given to a jury of experts from the Department of Languages and Translation at BZU who confirmed its face and content validity. Besides, a translated (into Arabic) copy from this scale was also prepared. As for the reliability of the scale, the internal consistency (Cronbach approach) and the test-retest approach were set by the original developers. The Cronbach coefficient of the foreign language scale was set by the original developers (Horwitz et al., Citation1986) as 0.93.

In the present study, Cronbach alpha coefficient is 0.87 and the test-retest coefficient is 0.84 which was higher than the threshold value (0.70) (Cronbach, Citation1951). Besides, the corrected item-total correlation ranged between (0.56–0.77), which indicated there was an acceptable level of internal consistency. As such, the scale is reliable and applicable to measuring speaking anxiety

9. Validity of the interviews

The set of interview questions (for seven students from the experimental group) was also validated by two educational experts.

Pilot interviews were conducted with the help of a group of student volunteers to ensure the clarity of questions and detect any possible vagueness and ambiguity in the questions.

10. Reliability of the interviews

To ascertain the reliability of the semi-structured interviews, the following steps were done:

The researcher ensured that the interviewees were fully willing to conduct the interviews voluntarily.

The researcher made sure that the interviewees understand the questions asked.

The interviews were conducted in English language and the responses were also reported in English.

After the interviews were conducted, the researcher summarized the interviewees’ responses, then the responses were approved by the interviewees.

11. Data analysis

To analyze the data that emerged before and after the treatment to answer the study’s questions, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Program (SPSS version 26) was utilized. To answer the research questions, one-way ANCOVA was used.

12. Results

To answer the first question regarding the extent BZU students have a foreign language speaking anxiety, the means and standard deviations of the pre-post-test scores in students’ speaking anxiety for the two groups were calculated as shown in Table .

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviation of the Students’ Speaking Anxiety

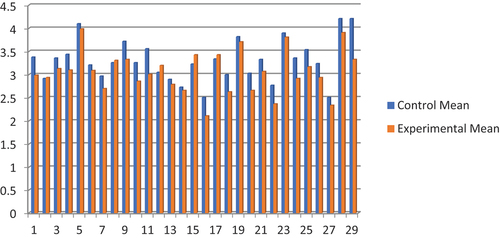

As shown in Table , the mean scores of the anxiety level of the two groups; control (3.9) and experimental (3.7), were relatively high (3.6). It also shows that the mean scores of anxiety for the experimental group are lower than the mean scores of the control group as measured by the anxiety scale. Figure shows that the means of the control group for the majority of items were higher than the means of the experimental group.

Figure 1. The means of speaking anxiety per item for the two groups.

To answer the second question related to investigating any statistically significant effect of the teaching technique (online speaking tasks) on the students’ speaking anxiety after controlling the effect of the pre-test scores, a One-Way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed as shown in Table .

Table 2. Results of one-way ANCOVA for the effect of teaching technique on the students’ speaking anxiety

Table shows a statistically significant difference in students’ speaking anxiety between the experimental and control groups in favor of the control group. The partial eta squared value of 0.329 indicates that the teaching technique explained 32.9% of the variance in students’ speaking anxiety. Additionally, the means, standard errors, and standard deviations of the two groups in the students’ speaking anxiety before and after controlling the pre-test scores were calculated. Table illustrates the results.

Table 3. Adjusted and unadjusted means of the speaking anxiety

As shown in Table , there are observed differences between the two groups in students’ speaking anxiety after the differences in the pre-test scores were controlled. As a result, it can be stated that the online speaking tasks (technique) decreased students’ speaking anxiety in the experimental group.

Regarding the third question, semi-structured interviews were conducted with (7) students from the experimental group to disclose their perspectives on online speaking tasks. The obtained data from interviews were analyzed according to the themes reflected by the interview questions stated below. The interviews have shown that the students had positive attitudes toward the online speaking tasks. Three questions were asked of all the interviewees. These were:

Describe your experience in the online speaking tasks, how did it go?

What was different about the online speaking task?

What do you think are the reasons that made the online speaking task experience less anxious and stressful?

The interviewees’ responses revealed the positive attitudes they have toward online speaking tasks. The students declared that the online speaking task experience has had positive impacts on them as speakers of English as a foreign language. All the interviewees stated that the experience went smoothly and quite well. One of them indicated that “It was a new experience that I have not done before, which was nice and different. I believe that it’s a good method that the speaker could use to develop his/her speaking and personality. Overall for the first time, it went smoothly and not stressful”. Another student described the experience as “different and useful”. She went on “a very wonderful and enjoyable experience. I learned a lot from this special shot. It wasn’t as hard and stressful as I thought it to be”.

The interviewees also reflected on how different the online speaking task was. Most of them agreed that the intervention was less stressful and anxious than they thought. They also emphasized the importance of having one’s own space and pace to speak freely with less tension away from the shyness of speaking in front of a crowd. One of them commented, “The difference is that you’re less stressful since you’re not in front of a crowd. You can keep repeating your speech until it’s perfect”. Another one stated “It was more comfortable and less stressful than speaking in front of an audience. There is also a sense of freedom to re-tape the video easily without anyone knowing about it! I used to laugh every time I made a mistake and also when I was looking at my brother’s face when he was filming me, but I don’t think I could laugh if my eyes met my friend’s eyes while talking”. A third student observed that “Unlike speaking at class and in front of my classmates, this shot was less anxious and different concerning my ability to take my own space to show my true personality away from shyness. Also, the filming and editing experience was really fun!”

Finally, the interviewees explained the reasons that made this experience less tense and more comfortable. They all agreed that online speaking tasks gave them the chance to be away from crowds and so have less fear to commit mistakes, in addition to the opportunity to repeat the speaking task multiple times until they reach perfection. One of the interviewees observed, “When the speaking task is online, speakers won’t perform in front of others, and this will make the experience less stressful for them.”

Another speaker confirmed the importance of having the opportunity to prepare well and repeat “Having enough time for preparation and more chances to repeat until you reach a satisfactory speaking level is extremely relieving and soothing”. Another added, “Not being afraid of mispronouncing a word and having the option to retake the video and avoiding being watched while speaking is highly convenient”.

13. Discussion

The current study aimed at researching to what extent BZU students have foreign language speaking anxiety, and it examined the effectiveness of using online speaking tasks on decreasing students’ level FLSA.

As shown previously, it can be concluded that the level of foreign language anxiety (Arabic and English) was relatively high. This result interprets the demotivation among students towards participating in classroom discussions, as well as can explain the low grades students tended to achieve in presentations in front of their classmates, although they were high-achievers and tended to gain high grades in paper-pen exams based on the researchers’ observation who teach foreign languages (English and Arabic) at BZU. In addition to that, the high level of anxiety that students in the two groups demonstrated in the results can suggest some reasons for the difficulty that students can have in explaining their ideas while interacting with instructors or even classmates using a foreign language. This finding is consistent with the previous studies (Horwitz et al., Citation1986; Male, Citation2018; Quyen et al., Citation2018; Oteir and Al-Otaibi, Citation2019) that demonstrated that FLSA can cause certain symptoms, such as sweating, trembling, fear, worry and difficulty in concentration so that they became embarrassed in front of their classmates, as they care immensely about their self-image as adult learners. It is worth noting that speaking is a cognitive activity that implies complex stages; encoding, storage and retrieval (MacIntyre, Citation1995), so when students become anxious while speaking a foreign language these processes are interfered causing attention distraction, which students can experience, between the speaking task at hand and the emotion-related issues. These affective factors that students go through while speaking a foreign language can be in charge of activating the Affective Filter and make learners defensive to foreign language input (Krashen, Citation1982).

Regarding the effect of using online tasks on students’ level of FLSA, the findings demonstrated that there were statistically significant differences between the control and experimental groups in the level of anxiety in favor of the control group, which indicates that students’ level of anxiety in the experimental has lowered after being asked to submit their video-audio tapped online presentations remotely. This result can be referred to the space that students in the experimental group had when they were asked to deliver the speaking tasks online in a way that gave them plenty of time to rehearse, practice and repeat before submitting their performance. In contrast, students in the control group had to manage the cognitive aspects of the language as well as the affective factors synchronously, which participated in leveling up their anxiety while speaking a foreign language. Besides, blending technology with the experimental group tasks may have been motivating and appealing for the experimental group students, and this may have participated in lowering their level of anxiety. This finding is also in harmony with previous studies (Ataiefar & Sadighi, Citation2017; Bashori et al., Citation2020; Grieve et al., Citation2021; Gruber & Kaplan-Rakowski, Citation2022) that confirmed the significance of using technology and online learning in improving foreign language students’ speaking and can lower the level of anxiety.

Regarding the discussion of the third study question’s results, it can be concluded that the speakers had positive attitudes toward the experience of online speaking tasks. This positiveness in speakers’ perspectives can be attributed to several reasons. First of all, delivering speaking tasks online and remotely can help students avoid the shyness and fear that resulted from speaking in front of others in a classroom setting. Thus, online speaking tasks can help speakers avert other students’ judgment when they commit mistakes. Furthermore, preparing a speaking task and sending it online for teachers and instructors can provide sufficient time for preparation and more chances to edit, repeat and modify before directing the speaking task to the targeted recipient. Finally, the speakers’ positive attitudes can also be imputed to the general feeling of self-confidence that most speakers have had after the experience. They acquired higher self-esteem and self-confidence after being able to produce orally in a foreign language. The general feeling of panic and apprehension that speakers usually have when speaking a foreign language, which is the headmost barrier to oral production, can be minimized and lessened in online speaking tasks. These inferences go in line with (Ataiefar & Sadighi, Citation2017; Gruber & Kaplan-Rakowski, Citation2022; Horwitz etal., Citation2010; Liu & Huang, Citation2011) that emphasized the positive impact of technology and online speaking tasks in reducing the levels of anxiety in foreign language speaking and promoting speakers’ oral production in the target language. This in turn can enhance speakers of foreign language attitudes and perspectives towards speaking in the foreign language in general and the online speaking experience in particular.

14. Conclusion and recommendations

This study is limited to the following considerations. First, it was carried out during the first semester of the academic year 2022/2023. Hence, a longer duration may have different results. In addition, this study was limited to investigating the anxiety levels of speakers of English and Arabic as foreign languages. No other foreign languages were included in the study. Upon close analysis of the findings that resulted in the current study, some conclusions and recommendations can be presented. It can be concluded that fostering learners’ speaking of a foreign language has been regarded as one of the issues that grabbed the attention of many people globally as learning a foreign language can function as their passport to the world. Thus, considering the emotional state of learners during teaching and learning a foreign language is a paradigm that foreign language teachers and educators worldwide should embrace while designing their teaching techniques and methods. Anxiety is an affective factor that can hinder and negatively interfere with learning a foreign, which may interpret high achievers’ defects in speaking foreign languages. The significance of the results of the current study also sprang from investigating two related the anxiety of students who studied two foreign languages; English and Arabic, which encourage other future efforts to include more detailed factors and to study more languages in the future. Thus, teachers of foreign languages are urged to blend online speaking tasks into teaching, as this technique was beneficial for decreasing students’ level of anxiety and for providing off-defensive learning environments. It is also recommended to measure any differences between the two modes of teaching (in-class-speaking activities versus online tasks) in terms of students’ speaking performance.

Ethical clearance

No ethical clearance was required from the institution (Birzeit University).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Haya Fayyad Abuhussein

Dr.Haya Fayyad AbuHussein is an assistant professor at the Department of Languages and Translation at Birzeit University, Palestine. She received her (BA) in English Language and Literature from An Najah National University, and her (MA) in the Arts of Teaching English from Al-Quds University-Bard College programme. In 2016, she was awarded a Fulbright Distinguished Award in Teaching at Indiana University in the United States of America. She completed her Doctorate at Yarmouk University, Jordan in Curriculum Studies and Methods of Teaching English as a Foreign Language in 2020. Dr. Fayyad Abuhussein is also a research visiting fellow at St. Antony’s and the Middle East Centre, University of Oxford. Dr. Fayyad Abuhussein is mainly interested in curriculum and TEFL studies.

Rania Mohammad Qassrawi

Rania Mohammad Qassrawi is an Assistant professor at Birzeit University in Palestine. She received her Ph.D. in Teaching English as a Foreign Language from Yarmouk University, Jordan. She has been working at BZU since 2017 in the Languages and Translation Department as well as in the Faculty of Education. She is highly interested in conducting research regarding the latest language teaching methods with a special emphasis on the psychology of language learning.

Sami Shaath

Sami Shaath is an assistant Professor at Palestine and Arabic Studies Program (PAS), Birzeit University. Dr. Shaath is specialized in teaching Arabic as a foreign language, both Standard Arabic and colloquial Palestinian dialect for international students through using modern teaching methods. He is also the co-founder of the PAS program in Birzeit University in 1994. His main research interests include the quality of teaching performance, students’ needs, and the difficulties students face while learning Arabic. Moreover, he also works on preparing Arabic language instructors at the university. Furthermore, Dr. Shaath works on developing special curriculum for teaching the Arabic language in the PAS program.

References

- Abrar, M. (2017). An investigation into Indonesian EFL university students’ speaking anxiety. Journal of English Education and Linguistics Studies, 4(2), 93–12. https://doi.org/10.30762/jeels.v4i2.358

- Alamer, A., Al Khateeb, A., & Jeno, L. M. (2023). Using WhatsApp increases language students’ self‐motivation and achievement and decreases learning anxiety: A self‐determination theory approach. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(2), 417–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12753

- Alsowat, H. (2016). Foreign language anxiety in higher education: A practical framework for reducing FLA. European Scientific Journal, 12(7), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v12n7p193

- Ariyanti, A. (2017). Foreign language anxiety in academic writing. Dinamika Ilmu, 17(1), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.21093/di.v17i1.815

- Arnold, J. (1999). Affect in language learning. Cambridge University Press.

- Ataiefar, F., & Sadighi, F. (2017). Lowering foreign language anxiety through technology: A case of Iranian EFL sophomore students. English Literature and Language Review, 3(4), 23–34. https://ideas.repec.org/a/arp/ellrar/2017p23-34.html

- Aydin, S. (2016). A qualitative research on foreign language teaching anxiety. The Qualitative Report, 21(4), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2232

- Bashori, M., Hout, R., Strik, H., & Cucchiarini, C. (2020). Web-based language learning and speaking anxiety. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(5–6), 1058–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1770293

- Bibauw, S., FranCois, T., & Desmet, P. (2015). Dialogue-based CALL: An overview of existing research. In F. Helm, L. Bradley, M. Guarda, & S. Thou€esny (Eds.), Critical CALL – Proceedings of the 2015 EUROCALL Conference (pp. 57–64). Researchpublishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2015.000310

- Brown, H. D. (1974). Affective variables in second language acquisition. Language Learning, 23(2), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1973.tb00658.x

- Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley Longman.

- Burns, A., & Joyce, H. (1997). Focus on speaking. Macquire University Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and Qualitative Research (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

- De Vries, B. P., Cucchiarini, C., Bodnar, S., Strik, H., & van Hout, R. (2015). Spoken grammar practice and feedback in an ASR-based CALL system. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(6), 550–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.889713.

- Dewaele, M., Petrides, V., & Furnham, A. (2008). Effects of trait emotional intelligence and sociobiographical variables on communicative anxiety and foreign language anxiety among adult multilingual: A review and empirical investigation. Language Learning, 58(4), 911–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2008.00482.x

- Gardener, R. (1980). On the validity of affective variables in second language acquisition: Conceptual and statistical considerations. Language Learning, 30(2), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1980.tb00318.x

- Gardner, R. C., & MacIntyre, P. D. (1993). A student’s contributions to second-language learning. Part II: Affective variables. Language Teaching, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800000045

- Grieve, R., Woodley, J., Hunt, S. E., & McKay, A. (2021). Student fears of oral presentations and public speaking in higher education: A qualitative survey. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(9), 1281–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1948509 Retrieved from.

- Gruber, A., & Kaplan-Rakowski, R. (2022). The impact of high-immersion virtual reality on foreign language anxiety when speaking in public. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3882215

- Hanafiah, W., Aswad, M., Sahib, H., Yassi, A. H., Mousavi, M. S., & Namaziandost, E. (2022). The impact of CALL on vocabulary learning, speaking skill, and foreign language speaking anxiety: The case study of Indonesian EFL learners. Education Research International, 2022, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5500077

- Horwitz, E. K. (2010). Research timeline. Foreign and second language anxiety. Language Teaching, 43(2), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480999036X

- Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

- Idri, N. (2012). Foreign language anxiety among Algerian EFL students: The case of first year students of English at the University of Abderahmane Mira-Béjaia; LMD (Licence/Master/Doctorate) System Group. Universal Journal of Education and General Studies, 1(3), 055–064.

- Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon.

- Kruk, M. (2018). Changes in foreign language anxiety: A classroom perspective. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 28(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12182

- Liu, M., & Huang, W. (2011). An exploration of foreign language anxiety and English learning motivation. Education Research International, 2011(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/493167

- Luo, H. (2012). Sources of foreign language anxiety: Towards a four-dimension model. Contemporary Foreign Language Studies, 12, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol10no3.21

- MacIntyre, P. D. (1999). Language anxiety: A review of the research for language teachers. Affect in Foreign Language and Second Language Learning: A Practical Guide to Creating a Low-Anxiety Classroom Atmosphere. 24, 41.

- MacIntyre, P., & Gregersen, T. (2012). Affect: The role of language anxiety and other emotions in language learning. Psychology for Language Learning: Insights from Research, Theory and Practice, 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137032829_8

- Male, H. (2018). Foreign language learners’ anxiety in language skills learning: A case study at Universitas Kristen Indonesia. Journal of English Teaching, 3(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.33541/jet.v4i3.854

- Mohammed, T. (2022). Designing an Arabic speaking and listening skills E-course: Resources, activities and students’ perceptions. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 20(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.34190/ejel.20.1.2177

- Nevid, S., Rathus, A., & Greene, B. (2005). Abnormal psychology in a changing world. Prentice Hall.

- Oteir, I., & Al-Otaibi, A. (2019). Foreign language anxiety: A systematic review. Arab World English Journal, 10(3), 3-9–317. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol10no3.21. doi.

- Oxford, R. L. (1999). Anxiety and the language learner: New insights. In J. In Arnold (Ed.), Affect in language learning. Cambridge University Press.

- Pan, H., Xia, F., Kumar, T., Li, X., & Shamsy, A. (2022). Massive open online course versus flipped instruction: Impacts on foreign language speaking anxiety, foreign language learning motivation, and learning attitude. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 85. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.833616

- Peeters, W., & Ludwig, C. (2017). Old concepts in new spaces’?–A model for developing learner autonomy in social networking spaces. Learner Autonomy and Web, 2, 117–142. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319645433_‘Old_Concepts_in_New_Spaces’_A_Model_for_Developing_Learner_Autonomy_in_Social_Networking_Spaces

- Quyen, P., Thi, P., & Nga, T. (2018). Challenges to speaking skills encountered by English-majored students: A story of one Vietnamese University in the Mekong Delta. Can Tho University Journal of Science, 54(5), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.22144/ctu.jen.2018.022

- Sammephet, B., & Wanphet, P. (2013). Pre-service teachers’ anxiety and anxiety management during the first encounter with students in EFL classroom. Journal of Education & Practice, 4(2), 78–87. https://core.ac.uk/reader/234633920

- Sauvignon, S. J. (1976). Understanding second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

- Schibeci, R. A., & Riley, J. P. (1986). Influence of students’ background and perceptions on science attitudes and achievement. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 23(3), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660230302

- Shams, A. N. (2006). Use of computerized pronunciation practice in the reduction of foreign language classroom anxiety. [ Doctoral Dissertation]. Florida State University.

- Thornbury, S. (2005). How to teach speaking. Longman Pearson.

- Weinburgh, M. H. (1998). Gender, ethnicity, and grade level as predictors of middle school students’ attitudes toward science. www.Ed.Psu.Edu/Ci/Journals/1998aets/S5_1_Weinburgh.Rtf

- Wörde, V. R. (2003). Students’ perspectives on foreign language anxiety. Inquiry, 8(1).

- Yamini, M., & Tahriri, A. (2006). On the relationship between foreign language classroom anxiety and global self-esteem among male and female students at different educational levels. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 9(1), 101–129.

- Yoon, T. (2012). Teaching English through English: Exploring anxiety in non-native pre-service ESL teachers. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 2(6), 1099–1107. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.2.6.1099-1107

- Yuan, R. (2023). Chinese university EFL learners’ foreign language classroom anxiety and enjoyment in an online learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2023.2165036