Abstract

Societal ostracism and socio-cultural integration of children with disability, as well as parents’ and monitors’ challenges therefrom, constitute issues that deserve particular examination and consideration. Owing to that, through a qualitative ethnography, we investigated such issues employing in-depth interview and observation (n = 15). Some major findings are the following. Societal ostracism is a deeply-rooted social tendency of the mainstream in Mali that unobtrusively affects minority groups, especially children with disability. Due to that situation, if children with disability may end up wandering in streets and the consequences this entails, parents and monitors daily experience frustration, bewilderment, and disarray. Increased advocacy and sensitization by key actors would be an effective engine for driving socially paradigmatic change regarding the phenomena of societal ostracism and socio-cultural integration of children with disability. We also found out that preparing children with disability for socio-cultural life integration is as important as preparing society itself to welcome and receive these children. Parents and monitors need increased multifaceted support from government, social services, and relevant organizations to overcome difficulties and issues related to children’s disability and their socio-cultural integration.

1. Introduction

In great many countries in the world, the situation of individuals with disabilities is a matter of preoccupation as to protect them from societal ostracism and ensure their education and social integration (Brady et al., Citation1987; Breena et al., Citation2011; Edwards et al., Citation2019). Rieser (Citation2006) and Nagase et al. (Citation2021) argue that physically impaired individuals’ disability situation is obstacle for them to integrate society, standard system of education and socio-economic activities in their community due to existential barriers in attitudes and organizational model of society. The World Report on Disability (Citation2011) affirms that more than one billion people live with a type of disability, one of ten children have at least one form of disability, and 80% of them live in developing countries. If their disability singles them out from the other children, children with disability certainly have the same rights as the gifted children in sight of global measures. Among such global efforts are Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, United Nations’ Convention of Children Rights in 1989, UN Rules of equal opportunities for people with disability in 1993, World Conference on special education needs (access and quality), in Salamanque in 1994, and US Convention on the rights of disabled people in 2006. Despite such measures, individuals and children with disability are ostracized and do not benefit from equal opportunities as the rest of the community members since most of them cannot access health-care systems, education, desired employment, and social integration (World Health Organization and The World Bank, Citation2011). The social group, if given a real chance to integrate society and dominant culture, would be autonomous and have a brilliant future (Belibova, Citation2016).

Around 15% of Malian population live with disability and there are more and more cases of disability despite joint efforts of different actors (ODHD, Citation2021; Tan, Citation2020). Factors causing or worsening disability include but not limited to natural or human-induced disasters, wars and conflicts, social prejudice, malnutrition-related issues (e.g. vitamin deficiency, undernourishment), disabling illnesses (e.g. diabetes, high blood pressure, meningitis), and (car, work etc.) accidents (ODHD, Citation2021). In Mali, individuals with disability insufficiently contribute to the development of the nation since they lack adequate support (Tan, Citation2020). Yet, in Mali also, many protecting laws exist for individuals and children with disability, including the New Millennium Objectives for Development, December 1999 Education Orientation Act, and National Policy on special education for fostering the special educational needs and social integration of children with disability. In spite of such policies, children with disability in Mali face many issues among which social reclusion.

The psycho-medical school, which is the context of this paper hosts children with special needs, including those around age six, seven, or beyond. This special school is independent but in close relationship with three relevant Ministries in Mali: The Ministry of Education, The Ministry of Social Action, Social Services, and Solidarity, and The Ministry of Health. Supported by many other international organizations like UNICEF, the school has a long-time history, since the 1980s, of special education provision for children with special needs with the purpose to improve their health, physical, and intellectual conditions and to facilitate their socio-cultural integration. It has since then dedicated itself to unloading somewhat the load of many parents by giving some appropriate education and medical care to their children. Children with disabilities such as autism, motor, intellectual problems, trisomy are taken care of in the school. The children then spend five or six maximum years through services such as physiotherapy, psychomotricity, occupational therapy, and speech therapy. Alongside medical care and assistance, the school aligns itself with the national curriculum and tries to impart to children with disability basic skills such as reading, writing, arithmetic, drawing, and painting.

Not only do group members with disability less and less receive consideration and respect in the society, but also their case constitutes a source of astonishment and curiosity by many (Center & Ward, Citation1987; Dell’anna et al., Citation2020). This fact pushed most of people with disability to live a life of a recluse and to accept marginalization in their unwillingness (Oliver, Citation2013; Rieser, Citation2006). By so acting, the group accepts living aside from others for fear of contemptuousness and mistreatment. Nowadays, marginalization, prejudice, and exclusion are social inhibitors for the group with disability to fully develop and integrate the mainstream (Dyson, Citation2012, Tan, Citation2020; Luo, Citation2020). Many studies have been conducted about the societal rejection and social integration of children with disability (Karaatmaca et al., Citation2019; Luo, Citation2020; Rieser, Citation2006). However, little is known about this phenomenon through the perspectives of parents and monitors (Rieser, Citation2006; Tan, Citation2020). In this study, we aim to address the issues of societal rejection/ostracism and socio-cultural integration of children with disability through the perspectives of and by observing parents and monitors. We also try to debunk challenges that parents and monitors of children with disability regularly face.

This study is organized as follows. We reviewed the literature pertaining to the issue in consideration for three aspects, including challenges of parents and monitors due to children’s disability, social exclusion/ostracism, and social and cultural integration of children with disability. In methodology, we elucidated the research design, the data collection method and procedure, followed by the findings section. We then elaborated on discussions, pointed out potential implications, limitations of the study and direction for further studies, and provided conclusive remarks.

This paper was a tentative participation in efforts that are meant to draw actors’ and public attention to the phenomenon of social rejection and problems of socio-cultural integration that children with disability experience. In the same vein, the study tried to highlight to these two audiences the challenges that parents and monitors of children with disability face. The solutions, therefore, proposed by this paper may inform policy, hone practical measures, and induce some amount of socially paradigmatic change regarding the case of children with disability, and their parents and monitors in Mali. To achieve such contributions, we tried to answer the following research questions:

How do parents and monitors perceive the issues of societal ostracism and socio-cultural integration of children with disability in the Malian society? In the same vein, what challenges do parents and monitors face in attending to the children with disability?

In parents’ and monitors’ views, what might be the solutions to eradicate the problems evoked above?

2. Literature review

2.1. Challenges of parents and monitors owing to child disability

To foster and attend to individuals with special needs, especially children with disability, is a perceptibly daunting task for both parents and monitors (Alshoura, Citation2021; Bamu et al., Citation2017). Children’s disability is source of stress, worry, and afflictions for parents since they remain uneasy about rejective tendencies of the society, challenges of upbringing and education, affording care and therapy, and the future of the child (Kalka & Lockiewicz, Citation2017; Leyser et al., Citation1988). Children’s disability seems to be exclusively the concern of parents and monitors since the rest of the immediate environment or society looks generally like indifferent (Leyser et al., Citation1988). In some African societies, traditional prejudices still label child’s disability as a sign of evil spell; hence pasting a social stigma on the family (Tan, Citation2020). In this case, the child with disability is confined at family and school because the social prejudice, shaping the widespread belief, is straightforwardly rejective (Karaatmaca et al., Citation2019; Tan, Citation2020). A socially constructed negative perception of children’s disability is thus a source of inconvenience and challenges for both parents and monitors. In many parts of the world, excruciating poverty of parents is consonant with decreased consideration for and less attention to the case of their children with disability (Tan, Citation2020). If those children logically belong to at-risk group, factors such as poverty of parents increase their level of vulnerability because they are not in capacity to afford school tuition and medical care for their children. Due to labelling system of specialists, some children’s disability does not prevent them from entering usual educational system whereas others need special education. In either case, parents face a proportionate amount of hardships (Tan, Citation2020). Elsewhere, besides being expensive, scarcity of special education schools can cause proximity problems to parents, adding more to their disarray (Leyser et al., Citation1988).

2.2. Societal exclusion/ostracism of children with disability

Societal ostracism or societal exclusion is the act whereby the dominant tendency or culture in a society rejects a minority group or prevents them from integrating the mainstream due to their exceptional characteristics, such as disability or old age (Karaatmaca et al., Citation2019; Luo, Citation2020; Walsh et al., Citation2018). Societal ostracism is reflected in a non-deliberate, tacit practice in society that induces a more or less brutal process of progressive societal link breakage for individuals with disability (Rieser, Citation2006). It is expressed in marginalization, social stigma, and social etiquette. Children with disabilities are then turned into social outcasts, forced solely into school and family life. Kane and Kyyrö (Citation2001) posit that societal practices conceal and fuel inequalities, such as societal rejection, since such practices, are labeled as good and inevitable. Ideologies and beliefs underpin, authenticate, and sustain rejective societal practices (Kane & Kyyrö, Citation2001; Rieser, Citation2006; Meyer & Meyer, Citation1991) against fragile groups such as children with disability. Rieser (Citation2006) contends that stereotypical practices take root in and is shaped by a community’s history, from which point they gradually perpetuate.

2.3. Social and cultural integration of children with disability

Social and cultural integration lies in the expression of equal chance for all, which is a state whereby all members of a society regardless of their social group benefit from and have access to society’s services and commodities such as material and cultural environment, housing and transportation, and health and education (Rieser, Citation2006; Sood et al., Citation2020). Luo (Citation2020) and Hirpa (Citation2021) add that social integration concerns the total participation of all individuals under any social group designations in any aspects of life of society and immediate environment that include benefiting from the full right, responsibility and obedience of rules and obligations in the society. The term “cultural” reinforces the dimension of social integration because human societal practices are entangled and clustered in established cultures (immediate way of life of a community), for instance, school systems, shopping habits, or health insurance models (Belibova, Citation2016). Dyson (Citation2012) identifies some strategies to make smooth disabled children’s social and cultural integration, including adequate surrounding conditions and positiveness of others’ attitudes toward children with disability. A determinant of social integration success is children’s achievement of self-worth and good conditions of life (Luo, Citation2020).

Although above studies depict well issues of societal rejection and social integration of disabled children, parents’ and monitors’ (special education teachers and therapists) voice is scarce in the extant literature. As illustration, Dyson’s (Citation2012) comparative study was targeting general primary education teachers to address social integration problem of disabled children. Luo (Citation2020) adopts an approach that moves from hindrances to solutions as for the social integration phenomenon of disabled children, specifically through the emphasis of psychological factors of children and social factors. The current study tries to supplement such existing literature through the perspectives of and by observing parents and monitors regarding issues of societal rejection and socio-cultural integration of children with disability and their hardships in relation to children’s disability.

2.4. Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework of this study, as shows, is based on Rieser’s (Citation2006) “social model” of disability. According to Burchardt (Citation2004) and Berghs et al. (Citation2019), the social model of disability originates from the fight of different movements, associations, and supporters of disabled people, especially from the Fundamental Principles of Disability document in the 1970s (Burchardt, Citation2004; Lawson & Beckett, Citation2021; Oliver, Citation2013). For this model, individuals and children with disability are an oppressed group in the society (Berghs et al., Citation2019; Finkelstein, Citation2001; Terzi, Citation2004). The social model of disability holds the premise that children with disability are to be viewed according to what they can contribute and what they can do in the society (Finkelstein, Citation2001; Rieser, Citation2006). Put another way, it emphasizes the social acknowledgement of disabled children’s potentials, value, and rights (Lawson & Beckett, Citation2020; Burchardt, Citation2004; Oliver, Citation2013; Rieser, Citation2006). This model advises not to view disabled children as individuals with differences and labels, but with capacities (Lawson & Beckett, Citation2020). According to the social model, the term “disability” has a negative connotation since it tacitly implies that physically impaired individuals have less opportunity range and less scope of social participation and contribution (Finkelstein, Citation2001; Rieser, Citation2006). With this term, a state of disablement hence underlies the situation of individuals with disability (Lawson & Becket, 2020; Oliver, Citation2013). Impairment describes appropriately physical, mental, or visual restrictions whereas disability reinforces the dimension of social barriers that hinder physically impaired individuals’ process of social and cultural integration (D’Souza, Citation2019; Lawson & Beckett, Citation2020; Rieser, Citation2006).

According to the model, socially constructed practices constitute the main disabling factors that prevent individuals and children with disability to avail of their social rights, services, and opportunities (D’Souza, Citation2020; Oliver, Citation2013; Riddle, Citation2020; Rieser, Citation2006; Terzi, Citation2004). Impairment per se is not tantamount to impossibility for individuals with disability to accomplish social tasks unless society enables their disablement (Goering, Citation2015, Lawson & Beckett, Citation2020; Rieser, Citation2006). The social model of disability is a social call and advocacy for the need to support, plead for, and involve in endeavors meant to halt societal ostracism and to help children with disability successfully integrate social and cultural life (Burchardt, Citation2004; D’Souza, Citation2019; Lawson & Beckett, Citation2021; Oliver, Citation2013; Riddle, Citation2020; Rieser, Citation2006; Samaha, Citation2007).

3. Methods

3.1. Study design

The current study adopted a qualitative design, especially critical ethnography, which stresses on aspects such as denunciation of unequal social practices and advocacy for a disfavored group (Creswell, Citation2012) with the purpose to correct injustice and/or drive change (Ary et al., Citation2010). In-depth interview and qualitative observational protocol were the instruments employed to collect data.

3.2. Participants

We sampled 15 research participants under non-probabilistic sampling where purposive and snowballing sampling procedures were used to obtain the sample of the study. Specifically, ten (10) parents who have their children in the school and five (5) monitors were the actual participants in this study. Tables provide a detailed breakdown of demographic information. The rationale for selecting three teachers and two monitors was to elucidate, respectively, some classroom instructional (educational) and therapeutic (medical care) issues that the professionals experience while caring daily the children with special need. The school put us through the indicated number of children’s parents on the basis of snowballing. It is noteworthy that information presented in Table under Disability Type of Children was provided by the school as it is technically accurate.

Table 1. Participants’ (Parents) demographic information and Disability Type of their Children

Table 2. Monitors’ Demographic Information

3.3. Procedures

The data collection spanning over three months took place in a psycho-medical school caring about children with disability and in families of the children’s parents in Mali, conducted upon the children’s parents and monitors. The case of this school in this ethnography is not fortuitous since it has nationwide consideration and is a pioneer engaged in the schooling, wellbeing, and social integration of the children with disability in Mali. In-depth interviews were employed with the purpose to approach the parents and monitors to gain far-reaching, in-depth understanding of the issues (Ary et al., Citation2010; DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, Citation2006). Through the in-depth interviews, we tried to tap to, collect, and make sense of parents’ and monitors’ experiences, concerns, feeling, and insights into the societal ostracism and social integration issues of children with disability. The in-depth interviews were also interested in recording the hardships that they encounter in fostering the children with disability. Face-to-face in-depth interviews offer the researcher the opportunity to tap to interviewees’ experiences in order to deeply comprehend a phenomenon and make sense of it (McGrath et al., Citation2019). Subsequently, we proceeded to non-participant observation, which helped gather fieldnotes both at school and in families to experience directly and witness the hard time and challenges the children, their monitors, and their parents regularly experience. During investigations, we used to carry out the observational session four times a week, twice in children’s family and twice at school. Each session could last two hours. Observation enables the researcher to sense the phenomenon in its natural setting, its contours and boundaries, and the outcomes of its interplay with such context (Bogan & Biklen, Citation1998). In-depth interview and observation are typical instruments of critical ethnography (Ary et al., Citation2010; Creswell, Citation2012).

3.4. Data analysis

To analyze data, we adopted Yin’s (Citation2003) model of convergence of evidence, meaning that data from the multiple method including interview and observational fieldnotes was all analyzed in an integrated manner. We transcribed, organized, familiarized with, and coded interview data (Ary et al., Citation2010; Marshall & Rossman, Citation2006), stressing on Values Coding to highlight aspects that criticize the society, which dimension well intertwines with critical ethnography (Saldaña, Citation2013). Observational fieldnotes were added to that process. From the codes, we identified categories, whose process led to developing themes (Creswell, Citation2007; Marshall & Rossman, Citation2006). We then interpreted and displayed the findings and meaning through thematic approach and thick description (Creswell, Citation2007; Walcott, Citation1994). The entire process of analysis followed a constant comparative method, which consists in putting together similar codes in units or categories, and similar categories in themes (Ary et al., Citation2010). Thematic coding was assisted by QDA Miner Lite version 2.0.9, alternative powerful computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS). All such data was then displayed in emic (direct refined accounts of participants) and etic (interpreted refined data by researcher) forms (Ary et al., Citation2010; Creswell, Citation2012). Before report, we brought the entire analyzed data to parents and monitors whether such data were representative of their views and experiences, for member checking purposes implying reliability of the study (Cresswell & Miller, Citation2000). They raised no major issue and we therefore drew the final report. In terms of ethical considerations, we carried out the study with the full consent and permission of the school administration and parents. All participants voluntarily brought their contributions and approved of the use of their credential details and report from the study. Owing to the nature of this study, we managed to do our utmost to solve all the ethical issues. Prior to study, the school granted full approval and consent, as per the Malian laws and regulations, to carry out the investigations. The school also directed us towards the parents who were presented and agreed with the consent form.

4. Results

Answer to Research Question 1:

Societal ostracism and socio-cultural integration of children with disability; Parents’ and monitors’ challenges in attending to children with disability

4.1. Society and rejection

Parents and monitors shared their experiences about what they think constitute the motives and consequences of their children’s societal ostracism, most of which points are in line with and add value to extant literature above. Interviewees claimed that rejection of their children with disability comes from society itself. “Whenever my child sets foot outside, they laugh at him and make fun of him. Such a situation of social rejection can but worsen my child’s case”, put forth a parent. “I think the outside world is unfair to my boy who suffers from cognitive issues. “They seem to look at him as somebody from another planet”, another parent stated. A monitor declared, “Children with disability are subject of misunderstanding by others and this aspect enormously complicates our task of socialization and education”. The consequences of societal rejection for the children with disability can be disastrous. A monitor made this moving remark:

We can notice that many disabled children are standing on roadsides begging for something to eat with their parents or kin. Some of them take early the path of drug addiction, left on their own, vagrancy and street life. It is mostly due to societal rejection, a sentiment of abandon. Don’t blame the parents because most of them are just poor and are already struggling for the daily crust; just blame the society. We are exactly trying to shield children with disability under our care from such danger.

4.2. Challenges

4.2.1. For parents

Alongside societal rejection of their kids, children’s parents experience problems due to their children’s disability such as language, communication, cognition, motricity, or instability issues. Parents affirm that such problems are dimensions of hardships for them. “It is no easy task caring about my boy that has cognitive and mobility troubles”, attested a parent. For this, the parents express their desire to see their children accommodated by the school for a long time. Many factors explain this standpoint such as the high cost in taking care of the child and protection inadequacy against dangers related to non-adapted social environment.

4.2.2. For monitors

The school faces many difficulties, including the lack of qualified personnel, adapted teaching-learning materials for activities and means of transportations, and less parental involvement. “Children’s disability unfortunately brings about other consequences such as parents’ melancholy, social rejection, and schooling issues”, posits a monitor. “For many in the society, being a person with disability is being different. We won’t refuse more assistance from government, social services, and NGOS to palliate such issues”, mentioned a monitor. The analysis of Table shows that there are more cases of children with autism, reaching four cases, followed by some cases of trisomy, motor, and mental retardation. This demonstrates that the school gathers and deals with children with different types of disability. “Each case presents unique challenges for us”, declares a monitor.

4.3. Monitoring and fostering children at school and home

We discovered that children’s monitors are passionate workers and devoted to their daily task, that is, the provision of quality educational, integrational, societal, and medical services to children with disability. A monitor could tell us, “The schooling of children with disability is part of their fundamental and unalienable right both on national and international bases. We need not snatch this from them. A big mind in a field may spring among these children labelled as ‘disabled’, but such talent is likely to be spotted in a learning setting like ours”.

It is such a delicate, and yet noble, task as the monitoring of children with disability. Through unswerving efforts and perseverance, the school struggles to provide somewhat adapted and adequate education to the children. “Children with disability need to be in schools that accommodate them for effective monitoring”, reported a monitor. All the children need to be treated on an equal basis and through unbiasedness. Two monitors, respectively, asseverated:

We are teachers and therapists that tend to the individual and collective educational and health needs of the children to enable their socialization and integration. When you get to know these children, you realize that they are amazing individuals capable of amazing things.

Both educators and therapists need to have a great humanistic sense when nurturing the children. These children with special needs deserve our attention and all we do for them need to be infused with our unshakable affection for them.

Our investigations reveal that parents assure the continuing monitoring of their children at home, which somehow facilitates monitors’ job at school. This means that parents try their best to abide by the instructions that the school gives them to ensure effective fosterage of the child and contribute to their development and the improvement of their lives. Interestingly also, parents show great satisfaction with the services of the school and the way their children are cared. Factors such as fostering methods, orientation, care, attention, quality service and personnel, and humanity can explain why parents have good ratings for the services of the school.

Answer to Research Question 2:

Solutions to: the problems of societal ostracism and socio-cultural integration of children with disability; and parents’ and monitors’ challenges

4.4. Potential solutions

4.4.1. Solutions at home and school level

Parents claim more support in order to play effectively their role in attending to their children. For instance, parents would like to provide some types of games and other forms of entertainment to their children such as taking them to amusement parks. They assume that recreational activities are of great benefit for the health of their progenies. What is more, by so doing, they would align themselves with the recommendations of the school, which bear upon the facilitation of the adaptability of the child to social realities. However, they claim not being in capacity of doing so due to precarious conditions and poverty. “I know that entertainment benefits much my kid. This can for instance facilitates his social integration and improve his health conditions but I need to be wooed doing it due to my difficult financial state”, asserts a parent. As witnessed in Table above, many parents deal with unstable and unsteady part-time jobs, which situation connotes their state of poverty. A parent avers, “Poverty is not tantamount to fatalism. The remedy is that we need secured jobs to kick poverty so we can grant descent living conditions to our children with disability”.

Monitors also claimed that their wish list contains items such as continuing training, adapted teaching and monitoring aids, interconnectedness (networking) with other special schools around the globe, and similar support. “We love these amazing creatures and we can better provide them quality service if empowered”, maintains a monitor. “We need to partner with other special schools in other countries so we can learn from each other and bring better care to children”, pleaded a monitor. Another monitor reported:

Government, NGOs, and society should need to involve more so as we all join hands for the well-being, alleviation of disability load, intellectual and physical development, and social integration of the children. Together, we can.

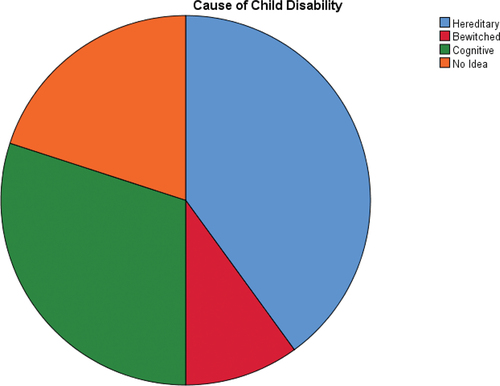

Most of the parents believe that their children’s disability is due to hereditary factors, and some others to cognitive related issues, as displays. As rooted in and fueled by popular imagination, one parent stated, “my child was victim of evil spell”. Sensitization must go to this sense to rule out ignorance and inform parents about the true common causes and type of disabilities of their children so as they can better rear their progenies at home.

4.4.2. Solutions at broader level

4.4.2.1. Advocating

Children with disability are not bound to stay everlastingly at home and at school even though they feel safe and secure in such settings. Like other individuals, they need to make contact with the external world to avail of their human rights. “Our human sense should act as a spur for us to allow the disabled children to enter the prevailing tendency of society”, declares a monitor. “We can’t claim to be democrat, just, and fair if we keep on pushing children with disability aside”, affirms a parent. Here is a combined assertion from a parent and a monitor:

Parents, monitors, officials, and NGO operatives form a small advocacy group for the cause of disabled children to the rest of the community. Through their joint actions, change is possible since the aim is to move from small group advocacy to community advocacy for children with disability.

4.4.2.2. Sensitizing

In a society where public attitude toward disabled individuals is generally negative, it remains crucial to increase sensitization in an attempt to change mindset. Communication canals such as television, radio, and social networks can help convey the message to the public as to the necessity of accepting and facilitating the integration of children with disability to the society. Highlighting to others the importance of social integration of exceptional children is a sound move to get the message through. “Each individual’s contribution is needed to build and develop the nation and the potential of children with disability is no exception”, contended a monitor. “People from all walks of life, including young and old, men and women, should be constantly enjoined to adopt positive attitude toward individuals with disability, especially exceptional children”, suggested a parent. A monitor emphasized:

National educational system programs from bottom to up should include rooms so as teachers can discuss with learners equality issues in the society, especially to advocate for the cause of children with disability. Because to drive change and positively shape new generation’s thinking about children with disability, there aren’t better places than schools.

4.4.2.3. Strengthening social activities at school and family

Family and schools are preparatory settings for children with disability to enter effectively social and cultural life. For this, parents and monitors need to accentuate social activities that enable the children to integrate smoothly the society, for instance, through entertainment and games. A monitor pointed out:

At our level and family, children are to be shown what good manners are and how to behave out there. Some of them already know how to cook, manipulate phones and other devices, play videogames, football, and other sports, show respect, and so on.

“My kid, suffering from trisomy, is in good relation with the rest of the family”, affirmed a parent. In addition, we researchers were honored to be welcomed by children with disability with a so beautiful a cappella song when we were initiating our interviews and observation at the school. A monitor made a moving remark:

Camaraderie is a positive and joyful situation that procures security, warmth, and comfort for the child. In addition, the child feels less stressed and isolated. Camaraderie also increases the child’s sense of belongingness to the mainstream without fear of rejection and marginalization.

4.4.2.4. Adapting life out there to disabled children

The interviewees (both parents and monitors) claimed not to deny the importance of preparedness of children with disability for outer life. For them, it also goes the other way around since they agreed to signal that the outside world should also be prepared all the way to welcome and receive children with disability. This is a calling into question as to say how much the society is ready for children with disability. Two monitors put forth such thought-provoking statements:

Of course, we are the first in charge of showing children how things move out there. But, let’s not forget a Deweyan perspective according to which schools are meant to help children unleash and reach their full potential and become their better unique selves. I do believe that we should not take this away from the children with disability in the name of socialization.

Education is everybody’s chance to make it through life, so is the case for these children. Putting children with disability through school (be it in a special or usual school) is providing them the opportunity to do one day something they like, live their passion, and be happy. It is building their self-esteem and self-reliance like gifted children.

In many African countries where dire poverty prevails, there is a crucial need for increased humanity and solidarity, empowered and active social services in order to tackle issues related to children’s disability, especially their societal ostracism and social integration problems. Another aspect is to ease the integration of children with disability in the main educational system, which process accelerates their social integration. A monitor and a parent could think alike:

There do exist national policies and governmental measures to systematically mainstream some of our children into the usual system of education. However, the translatability of such policies into action is still a vain hope for the children, and consequently for us monitors and parents.

5. Discussion

The socio-cultural integration of children with disability in the mainstream still remains a pipe dream in Mali, as revealed in the synthesis of the findings above. The negative attitude from the public that views disability as a social stigma is the root cause for the socio-cultural ostracism of children with disability, as corroborated by Mueller (Citation2019), Rieser (Citation2006), and Wahat et al. (Citation2021). Consequently, children may face outcomes detrimental to their health and educational conditions like isolation at school and home, vagrancy, drug life, bad company, and begging. Results analysis also debunked that the challenges faced by exceptional children’s parents and monitors are twofold. Their first hardship relates to providing adequate care and education to the children due to scarcity of appropriate capacitation. Their second ordeal is to witness a society that ostracizes the kids from socio-cultural integration. As a result and as Vaughan and Super (Citation2019) and Hsu et al. (Citation2021) attest, such challenges undermine parents’ and monitors’ efforts in quality care provision to the children.

It urges to think out practical and pragmatic solutions to the public mindset that bars children with disability from joining in the predominant socio-cultural life. Put another way, potential solutions may consist of dynamics for common mentality change, including advocacy, sensitization, and facilitation of socialization and adaptation. There is the need of increased advocacy and sensitization for the cause of the physically impaired children’s full-scale socio-cultural integration (Hsu et al., Citation2021). Advocacy and sensitization consolidate social actions and raise awareness among community for helping children with disability to gain wider acceptability among the mainstream (Berghs et al., Citation2019; Oliver, Citation2013; Rieser, Citation2006). As Karaatmaca et al. (Citation2019) put it, instead of pity, exceptional children are only advocating for acceptability, consideration, and involvement in community life. It is noteworthy that the schooling process of children with disability should include socialization and adaptation (Luo, Citation2020) even if such points should only be part of the central foci in their education. Because, for humanistic educators like John Dewey and Maria Montessori, any children of any social group should benefit from quality instruction that enables their full development. For this, education primarily serves the interest of children, not that of society (Dewey, Citation1956; Montessori, Citation1912). To prepare exceptional children for social life integration is as important as to prepare the society itself to welcome and receive them.

Parents and monitors, as Hsu et al. (Citation2021) and Dijkstra and Rommes (Citation2021) agree to say, are in urgent need of sustainable support to be able to ensure the well-being and education of the children with disability. The treble preoccupation of parents and monitors includes good education and adapted therapeutic care, facilitation of socialization, and socio-cultural integration of children with disability. Specifically, as Gur and Stein (Citation2020) view it, they need continuing assistance from and constant collaboration with governmental and non-governmental bodies and relevant social services. Luo (Citation2020) posits that governmental and non-profit organizations play a major in alleviating the burden of parents and monitors, as well as in participating in efforts meant to solve the marginalization and socio-cultural integration issues of children with disability. International collaboration and networking among different special schools and actors in different countries, as emphasized by Hayward et al. (Citation2022), is also an efficient means to offer global assistance to children with disability, their parents, and monitors. As sustained in Hsu et al. (Citation2019), Dijkstra and Rommes (Citation2021), Luo (Citation2020), Karaatmaca et al. (Citation2019), and Vaughan and Super (Citation2019), in the process of inducing positive change in the society for the socio-cultural integration purpose of children with disability, some human values need to be rekindled, including solidarity, mutual acceptability, love, social justice, inclusiveness, and viewing each other through potentials and not as social groups.

6. Implications for practice

The findings from this study may not be generalizable about other contexts since we followed the tradition of a qualitative ethnography, which focuses on addressing issues of inequalities occurring within or about a culture-sharing group, a bounded case (Ary et al., Citation2010; Stake, Citation1995). Moreover, a qualitative study deeply explores a phenomenon for more comprehension and insights, which dimension does not necessarily seek transferability to other situations (Bogan & Biklen, Citation1998). However, a case that is studied can inspire knowledge about other similar cases in other contexts; hence a form of moderate generalizability (Creswell, Citation2012; Stake, Citation1995).

The potential ramifications of the current study for practice may stand in a multidimensional manner. It may raise more awareness among decision makers to make sure policy and action for social integration of children with disability are moving together and nationwide accentuated. Decision makers may also increase the support level destined for exceptional children’s parents and monitors to reduce their challenge load. The packaged support can include presence of highest authorities near parents and monitors, monetary assistance, facilitating networking with other special schools, encouragement, appropriate didactic and therapeutic materials, advocacy for exceptional children’s social integration through nationwide sensitization, and others. Decision makers, NGO operatives, school leaders and teachers, and any relevant structures may lean for support on the proposed solutions from this study to fight against societal ostracism of exceptional children and to drive change among the population.

7. Limitations and suggestions to further studies

This study attempted to solve rejective and integrating issues of children with disability and their parents’ and monitors’ hard knocks therefrom. However, it has the following limitations with pertaining suggestions to future studies. First, this ethnography only covers one single case related to a culture-sharing group. A multi-case study can also shed much light on the issue. Second, the solutions that are provided may stand as context-specific, not necessarily applicable to other situations. Future studies can test such solutions to other contexts so as to grasp hold of what works. Lastly, the current work used only a qualitative study. A replication of this study using a full-scale mixed method would also help generate more depth and breadth of the issue.

8. Conclusion

This interview and observational ethnography endeavored to address the problems of societal ostracism, hindrances of social integration of children with disability, and challenges of parents and monitors related to children’s disability, and potential solutions to address these issues. Children with disability need not only attention, understanding, and care from their parents and monitors, but also from the mainstream. Societal acceptability of children with disability is a major determinant of parents’ and monitors’ success and relief. Societal ostracism of children with disability constitutes not only huge adversity for parents and monitors, but also a sword of Damocles hanging over the children’s chances to a brighter future.

Short Summary

This research study was carried out by a team of doctoral candidates at the Faculty of Education of Southwest University, in Chongqing, in China. This work goes into the list of a series of similar studies about inequality related issues of vulnerable social groups in education that the team is attempting to address. School-life relationship problems of children with disability, rural girls’ schooling, race, ethnic, and gender matters in education, inclusiveness in education, and curriculum inequalities are illustrations of our research team interests. Below is a picture of the main and corresponding author, Cheick Amadou Tidiane Ouattara.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

We express our thanking and gratitude to Dr. Shengquan Luo, Professor, Dr. Ying Tang, Associate Professor, both at the Faculty of Education, Southwest University, China. Our thanking also goes to Dahamane Mahamane, PhD, Secretary General and Professor at the Teacher Training College of Bamako (ENSup), Mali, and Mr. Mohamed Kouyaté, graduate of Social Service Higher Institute of Bamako, top-level Administrator. Their illuminating guidance, teaching, and insights have much served our purpose, pointed us at the right direction, and been crucial to the accomplishment of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cheick Amadou Tidiane Ouattara

This research study was carried out by a team of doctoral candidates at the Faculty of Education of Southwest University, in Chongqing, in China. This work goes into the list of a series of similar studies about inequality related issues of vulnerable social groups in education that the team is attempting to address. School-life relationship problems of children with disability, rural girls’ schooling, race, ethnic, and gender matters in education, inclusiveness in education, and curriculum inequalities are illustrations of our research team interests. Below is a picture of the main and corresponding author, Cheick Amadou Tidiane Ouattara.

References

- Alshoura, H. (2021). Critical review of special needs education provision in Malaysia: Discussing significant issues and challenges faced. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 70(5), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2021.1913718

- Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Sorensen, C., & Razavieh, A. (2010). Introduction to research in education (8th ed.). WadsWorth Cengage Learning.

- Bamu, B. N., Schauwer, E. D., Verstraete, S., & Hove, G. V. (2017). Inclusive education for students with hearing impairment in the regular secondary schools in the North-West Region of cameroon: Initiatives and challenges. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 64(6), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2017.1313395

- Belibova, S. (2016). Social integration of children with intellectual disabilities from poor rural families of the republic of Moldova. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16(1), 989–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12243

- Berghs, M., Atkin, K., Hatton, C., & Thomas, C. (2019). Do disabled people need a stronger social model: A social model of human rights? DISABILITY & SOCIETY, 34(7–8), 1034–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1619239

- Bogan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (1998). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods (3rd ed.). Ally and Bacon.

- Brady, M. P., McEvoy, M. A., Wehby, J., & Ellis, D. (1987). Using peers as trainers to increase an autistic child’s social interactions. The Exceptional Child, 34(3), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/0156655870340306

- Breena, L., Wildy, H., & Saggers, S. (2011). Challenges in implementing wellness approaches in childhood disability services: Views from the field. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 52(2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2011.570500

- Burchardt, T. (2004). Capabilities and disability: The capabilities framework and the social model of disability. Disability & Society, 19(7), 735–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000284213

- Center, Y., & Ward, J. (1987). Teachers’ attitudes towards the integration of disabled children into regular schools. The Exceptional Child, 34(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/0156655870340105

- Cresswell, J. W., & Miller, D. (2000). Determinig validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Eductional research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Dell’anna, S., Pellegrini, M., Ianes, D., & Vivanet, G. (2020). Learning, social, and psychological outcomes of students with moderate, severe, and complex disabilities in inclusive education: A systematic review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 69(6), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2020.1843143

- Dewey, J. P. Books, Ed. (1956). The child and the curriculum the school and society. The University and Chicago Press.

- DiCicco-Bloom, B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). Making sense of qualitative research: The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40(4), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

- Dijkstra, M., & Rommes, E. (2021). Dealing with disability: Challenges in dutch health care of parents with non-Western migration background and a child with developmental disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(23), 7178–7189. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1985637

- D’Souza, R. (2019). Exploring ableism in Indian schooling through the social model of disability. DISABILITY & SOCIETY, 35(7), 1177–1182. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1668635

- Dyson, L. (2012). Strategies for and successes with promoting social integration in primary schools in Canada and China. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 59(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2012.676422

- Edwards, B. M., Cameron, D., King, G., & McPherson, A. C. (2019). How students without special needs perceive social inclusion of children with physical impairments in mainstream schools: A scoping review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 66(3), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2019.1585523

- Finkelstein, V. (2001). The social model of disability repossessed. Manchester Coalition Of Disabled People – 1stdecember 2001.

- Goering, S. (2015). Rethinking disability: The social model of disability and chronic disease. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med, Springer, 8(2), 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-015-9273-z

- Gur, A., & Stein, M. A. (2020). Social worker attitudes toward parents with intellectual disabilities in Israel. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(13), 1803–1813. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1537382

- Hayward, B. A., Mckay-Brown, L., Poed, S., & McVilly, K. (2022). Idenfying important persons in the promotion of positive behavior support (PBS) in disbility services: A social network analysis. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 47(4), 292–307. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2021.1984084

- Hirpa, D. A. (2021). Exclusion of children with disabilities from early childhood education: Including approaches of social exclusion. In B. F. Ewing (Ed.), Cogent Education (pp. 1–20). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1952824

- Hsu, T.-L., Deng, F., & Cheng, S. (2021). An examination of parents’ perceptions of developmental disability, social support, and health outcomes among Chinese American parents of children with developmental disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilites, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2021.1994819

- Kalka, D., & Lockiewicz, M. (2017). Happiness, life satisfaction, resiliency and social support in students with dyslexia. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2017.1411582

- Kane, E. W., & Kyyrö, E. K. (2001). For Whom Does Education Enlighten?. Gender & Society, 15(5), 710–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015005005

- Karaatmaca, C., Altınay, M., & Toros, E. (2019). Stop the pity, unlock the potential: The role of non-governmental organizations in disability services: Evaluating and monitoring progress. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 66(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2019.1642454

- Lawson, A., & Beckett, A. E. (2021). The social and human rights models of disability: Towards a complementarity thesis. The International Journal of Human Rights, 25(2), 348–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2020.1783533

- Leyser, Y., Margarit, M., & Avraham, Y. (1988). Families of disabled children in the israeli kibbutz: A community which provides for all needs. The Exceptional Child, 35(3), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0156655880350305

- Luo, T. (2020). Difficulties and solutions for social integration of disabled children. In E. a. Advances in Social Science (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Seminar on Education, Management and Social Sciences (ISEMSS 2020). 466, pp. 532–537. Sewanee, TN: The University of the South, Atlantis Press.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2006). Designing qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- McGrath, C., Palmgren, P. J., & Liljedahl, M. (2019). Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Medical Teacher, 41(9), 1002–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497149

- Meyer, L., & Meyer, L. H. (1991). Social integration and severe disabilities: A longitudinal analysis of child outcomes. The Journal of Special Education, 25(3), 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/002246699102500306

- Montessori, M. (1912). The montessori method: Scientific pedagogy as applied to child education “the children’s houses” with additions and revisions by the author. Frederick A. Stokes Company. https://doi.org/10.1037/13054-000.

- Mueller, C. (2019). Adolescent understanding of disability labels and social stigma in school. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 32(3), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1576940

- Nagase, K., Tsunoda, K., & Fujita, K. (2021). Effects of teacher efficacy and attitudes toward inclusive education for children with disabilities on the emotional distress of middle school teachers in Japan. In A. Pepe (Eds.), Cogent education (pp. 1–14). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.2007572

- ODHD (Observatoire du Développement Humain Durable [Body in Charge of Human Sustainable Development]). (2021). Etude de base sur les personnes vivant avec un handicap au Mali, avec un focus sur les enfants de 0-17 ans Malian Government.

- Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability and Society, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.818773

- Riddle, C. A. (2020). Why we do not need a ‘stronger’ social model of disability. DISABILITY & SOCIETY, 35(9), 1509–1513. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1809349

- Rieser, R. (2006). Disability equality: Confronting the oppression of the past. In M. Cole (eds.), Education, Equality and human rights issues of gender, ‘race’, sexuality, disability and social class (pp. 134–156). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Samaha, A. M. (2007). What good is the social model of disability? The University of Chicago Law Review, 74(4), 1251–1308. Retrieved from. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20141862

- Sood, S., Kostizak, K., Stevens, S., Cronin, C., Ramaiya, A., & Paddidam, P. (2020). Measurement and conceptualisation of attitudes and social norms related to discrimination against children with disabilities: A systematic review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 69(5), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2020.1786022

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The Art of Case Study Research. Sage Publications.

- Tan, D. (2020). Être une fille et handicapée en Afrique de l’Ouest. La situation éducative en question – Étude Pays – Mali. Humanité & Inclusion.

- Terzi, L. (2004). The social model of disability: A philosophical critique. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 21(2), 141–157. Retrieved from. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24355191

- Vaughan, K. P., & Super, G. (2019). Theory, practice, and perspectives: Disability studies and parenting children with disabilities. Disability & Society, 34(7–8), 1102–1124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1621741

- Wahat, N. W., Mohamed, N. A., D’Silva, J. L., & Hassan, S. A. (2021). Development and validation of self-acceptance scale for people with disabilities in Malaysia. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2021.1931817

- Walcott, H. F. (1994). Transforming qualitative data: Description, analysis, and interpretation. Sage Publications.

- Walsh, B., Dinning, T., Money, J., Money, S., Maher, A., & Boylan, M. (2018). Supporting reasonable adjustments for learners with disabilities in physical education: An investigation into teacher’s perceptions of one online tool. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1525828

- World Health Organization and The World Bank. (2011). World report on disability. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). 3rd Case Study Research Design and Methods. Sage Publications.