Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore and analyse teachers’ perspectives on factors influencing the school climate, to better understand teachers’ everyday efforts in influencing the school climate, including obstacles they might experience. Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological theory was utilized as the overarching theoretical perspective. Data were collected by means of 14 semi-structured focus group interviews with 73 teachers from two compulsory schools in southeast Sweden. Findings revealed that teachers experienced the school climate as both positively and negatively influenced by a number of internal and external factors, perceived as influenceable or uninfluenceable. According to the teachers, four types of factors affected the quality of the school climate: social processes and values in school (i.e. influenceable internal factors), school premises and support structures (i.e. uninfluenceable internal factors, external relations (i.e. influenceable external factors) and external means of control (i.e. uninfluenceable external factors). A grounded theory of teachers’ perceptions of factors influencing school were developed. Our conclusion is that the teachers talked about a multidimensional and malleable phenomenon, emanated by a complex interplay across multiple agents and contexts both within and outside the school, aligning with all domains and features and acting as preconditions for the school climate.

1. Introduction

The importance of creating a positive school climate has received increased attention in research and from practitioners (Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016). A positive school climate is associated with greater academic achievement (Demirtas-Zorbaz et al., Citation2021), particularly for students with lower socioeconomic backgrounds (Berkowitz et al., Citation2017), and psychological health and wellbeing among students (Aldridge & McChesney, Citation2018). Students in schools with a positive school climate are less likely to engage in problem behaviours such as delinquency and violence perpetration over time (Reaves et al., Citation2018).

School climate alludes to the quality and character of everyday life at school (Gase et al., Citation2017) and includes basically all aspects of people’s experience of school life (Cohen et al., Citation2009; Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), thus illustrating a holistic multidimensional construct. Even though there is no consensus on the optimal definition of school climate, one well established and often used definition refers to “the quality and character of school life” (National School Climate Council, Citation2007, p. 5), including a diversity of people and characteristics shaping the school system. Quality and consistency of interpersonal interactions within the school (Fan et al., Citation2011) based on students’ and school staff’s common values, attitudes and beliefs (Mitchell et al., Citation2010) are emphasized as important features of the school climate.

In their daily interactions with the students, teachers are a part of the school climate and have, at the same time, a professional responsibility to establish a positive and healthy school climate. Consequently, we assume that teachers, with their unique key position in schools, possess crucial information that can increase the understanding of teachers’ everyday efforts in influencing the school climate. Therefore, the focus in this article is on teachers’ perspectives on school climate, including obstacles they might experience.

Previous research, compiled in two reviews of school climate (Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), clearly shows that a positive, warm and supportive school climate beneficially influences teachers’ working conditions, students’ academic achievement and the well-being of everyone at the school. The most common features studied are, according to Garzia and Molinari (Citation2021), safety and engagement. Although there is a great deal of agreement between researchers that the multidimensional construct of school climate can be classified into some essential dimensions or areas, they do not agree on which, or how many labels to consider, or the features of each dimension or area (Cohen et al., Citation2009; Gase et al., Citation2017; Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016). One way to describe the school climate, based on assessment on 327 sources of previous research, is to use four domains: academic climate, community, safety, and institutional environment (Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016). Each domain alludes to the current concept of school climate and includes features from several previous classifications of school climate.

Academic climate encompasses the overall quality of learning and teaching processes, including features such as leadership and teachers’ professional development. Community accounts for connectedness to the school and the quality of interpersonal relationship between students, teachers, staff and people outside the school. Safety comprises physical and emotional safety as well as the quality of discipline practices at the school. Institutional environment refers to environmental and organizational aspects of the school but also the allocation of resources and student mobility. There are some ambiguities concerning whether cohesion should be part of the community domain or its own domain (Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021). In this article, we follow the researchers who use four domains, thus including cohesion in the community domain. Notwithstanding, each domain contributes individually but also jointly to the school climate and how it is collectively experienced both from inside and outside the school.

2. Research on school climate

Most research on school climate has adopted a quantitative approach based on student reports (Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Lenz et al., Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016). While such studies have elicited important knowledge on school climate, teacher reports and qualitative research methodologies should not be underrated. Qualitative research enables researchers in-depth exploration and understanding of the perceptions and experiences of individuals and groups, to capture detailed and nuanced data, and to give teachers an opportunity to discuss their own understanding of school climate in their own voices. The majority of qualitative studies on school climate has focused on students’ perspectives (e.g., Enkhtur et al., Citation2022; Forsberg et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Giraldo-García et al., Citation2023; Konishi et al., Citation2022; Newland et al., Citation2019; Strindberg & Horton, Citation2022; Zaatari & Ibrahim, Citation2021), whereas qualitative research on teachers’ or school staff’s perspectives is still scarce.

Considering the dominance of students as informants in previous research, more studies from different perspectives are requested that, as Wang and Degol (Citation2016) phrase it, “can boost the explanatory power of school climate” (p. 341). Consequently, teachers’ understanding of factors influencing the school climate should not be neglected, but instead be seen as crucial information for facilitating and sustaining a positive school climate as it will affect their attitudes and behaviours. The spare studies elucidating teachers’ voices on school climate have been concentrated on teacher safety and victimization (Berkowitz et al., Citation2022), teachers’ job satisfaction (Heinla & Kuurme, Citation2022), student’s self-regulating learning (De Smul et al., Citation2020), student mental health (Jessiman et al., Citation2022), school climate and LGBT+ students’ situations in school (Harris et al., Citation2021), what school climate factors teachers perceive predict students’ sense of belonging (Zaatari & Ibrahim, Citation2021), how teacher think their caring and collaboration are linked with student engagement and sense of belonging (Walls et al., Citation2021), school climate in inclusive schools (Pandia & Purwanti, Citation2019), and breaktime or recess (Horton et al., Citation2020; London et al., Citation2015) in relation to surveillance and school bullying (Horton et al., Citation2020). Less is known about what factors teachers consider to influence the school climate. In the present study, we have conducted focus group interviews to examine teachers’ perspectives in order to contribute to filling some gaps in the research field on school climate.

In addition, most studies on school climate where teachers have been the source of data have adopted a quantitative research approach (like when students have been the source of data), including a predetermined scale on school climate (Aldridge & McChesney, Citation2018; Berkowitz et al., Citation2017; Steffgen et al., Citation2013). Our study is, as far as we know, the first to examine teachers’ perspectives on factors influencing the school climate with a qualitative research design. Qualitative research methods offer an opportunity to examine teachers’ insider perspectives, experiences and main concerns (Charmaz, Citation2014; Flick, Citation2018), which are highly relevant considering teachers’ unique key position in school, their everyday influence on school climate and their professional responsibility of establishing a positive and healthy school climate in their interactions and collaborations with students and colleagues.

As many different dimensions might affect the classroom- and school climate it is imperative to acknowledge how also several factors both inside and outside the school might affect the school climate (Fraser, Citation2012). Because of this, we approach the school climate as produced by ongoing reciprocal interactions between different systems such as the home and the school, or the organization and the classroom. To be able to explore the complex interdependent interaction between individual and contextual factors we have adopted a social-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979).

3. The present study

The aim of this study was to explore and analyse teachers’ perspectives on factors influencing the school climate, to better understand teachers’ everyday efforts in influencing the school climate, including obstacles they might experience. To conceptualize the complexities and interaction of influencing factors addressed by the teachers, and the teachers’ apprehension of the possibility to influence these factors, we adopted a social-ecological perspective.

4. A social-ecological framework

Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994) social-ecological theory, which is one of the dominant theories used in school climate research according to Wang and Degol (Citation2015), emphasizes the complex interdependent interaction between individual and contextual factors. According to this perspective, there is a complex interplay among multiple agents and contexts both inside and outside the school influencing the school climate. Therefore, school climate must be seen as a multidimensional phenomenon (Wang & Degol, Citation2016, p. 319). From a social-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994), school climate can be understood as produced by an ongoing reciprocal interaction between different systems.

Microsystem accounts for the immediate environment in the school containing students and staff and the relationship between them. Mesosystem refers to local environments encompassing the relationships between different microsystems (e.g. school and family environment). Exosystem refers to factors existing in an environment outside the local environment where the individual is not directly present (e.g. the municipality, parents’ workplace). Macrosystem accounts for the all-encompassing society and includes social, political and economic structures and ideologies. Chronosystem consists of environmental change, historical events in children’s life, and transitions, such as moving or changing school.

Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological theory also aligns with the approach describing the multidimensional features of school climate using four domains (i.e. academic climate, community, safety and institutional environment). By adopting a social-ecological framework and emphasizing the complex interdependent interaction between individual and contextual factors, we elucidate that teachers are a part of, and are influenced by, different characteristics of the school system. In accordance with the constructivist grounded theory, we did not use the social-ecological theory to deduce explanations, but as a loose framework and a starting point (Charmaz, Citation2014), as a source of possible seeing and analytical tools in order to interpret and analyse our data (Thornberg, Citation2012).

5. Method

The present study combined a qualitative case study design (including two cases in terms of two public schools in Sweden) with a constructivist grounded theory design (Charmaz, Citation2014).

5.1. Participants

The participants of the current study consisted of 73 teachers (49 women and 24 men) from two compulsory schools in southeast Sweden. School A was a K-9 municipal school located in a small village, whereas School B was a K-6 independent school located in a medium-sized city. All teachers at both schools were invited to participate.

5.2. Data collection

We conducted focus group interviews with naturally existing working teams at the schools. However, three work teams included more than eight teachers each and were therefore each divided into two focus groups to facilitate individual participant’s voice and participation in the interview, which otherwise might be inhibited in too-large focus groups (Krueger & Casey, Citation2014). This procedure resulted in 14 focus group interviews with an approximately equal number of participants in each group (m = 5; range 3–7) that, in total, included all the 73 teachers in the study.

The first and second authors conducted the focus group interviews. They were well trained in doing qualitative interviews and focus group interviews with many years of experiences. To increase the trustworthiness of the data, they adopted an empathic and non-judgmental approach, and took the role as an active listener and interested learner. “If interviewers take on the role of the interested learner rather than, say, the distant investigator, they open spaces for their research participants to be experts on their lives” (Charmaz, Citation2014, p. 73). In line with the study aim, they used a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions that included questions on school-, classroom- and group climate (e.g. “How do you perceive the school-/classroom-/group climate at the school?”; “How do you work with improving the school-, classroom- and group climate? Challenges/possibilities?”; “What support do you perceive in this work, and by whom?”). We were careful with having these questions as open-ended questions to avoid pushing our personal assumptions and hypotheses on them in order to remain open-minded, curious and sensitive as researchers and to facilitate the teachers to talk about and discuss their own understanding and experiences in their own voices.

Probing questions were used to further elaborate on the teachers’ perspectives. This flexibility of the interview process enabled us to capture the teachers’ perspectives on various factors affecting the school-, classroom and group climate and to bring up all sorts of social-ecological systems affecting their work such as mesosystem aspects (eg., home environments), exosystem aspects (eg., organizational matters) or microsystem aspects (eg., relationships and processes in the school). The focus group interviews ranged from 39 to 75 minutes (m = 54; in total 13 hours and 32 minutes) and took place in the teachers’ ordinary conference rooms at their schools. The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and imported to the qualitative analysis program MAXQDA 18.

5.3. Analysis

The analysis was guided by a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz, Citation2014) in which the teachers’ perspectives are viewed as co-constructed through interaction between the participants and between them and the researcher. This approach is particularly suitable in educational studies (Lindqvist & Forsberg, Citation2022) where data are collected in focus group interviews and the researcher is interested in the participants’ perspectives on a phenomenon. In our analysis, we adopted initial, focused and theoretical coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). The coding process started with several perusals of the data, while simultaneously carrying out an initial line-by-line coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). During initial coding there was an openness towards the data by asking questions such as what is going on here, what aspects do the teachers mainly talk about and how do they understand these aspects. Through our close readings of data, we constructed initial codes by naming segments of data with labels that, at the same time, summarized and accounted for each piece of data. While coding, we used the constant comparison method and, thus, compared data with data, data with codes, and codes with codes in a search for similarities and differences (Charmaz, Citation2014), and to find recurrent patterns in the data. Through the end of initial coding, and as a result of constant comparisons and memo-writing, we grouped our initial codes and developed them into more comprehensive codes identified as focused codes. According to Charmaz (Citation2014), focused codes represent the most frequent and significant initial codes. We constructed focused codes on what teachers described as influencing the school climate. During focused coding, we turned our attention to these factors and analysed these codes in more detail and compared them with each other.

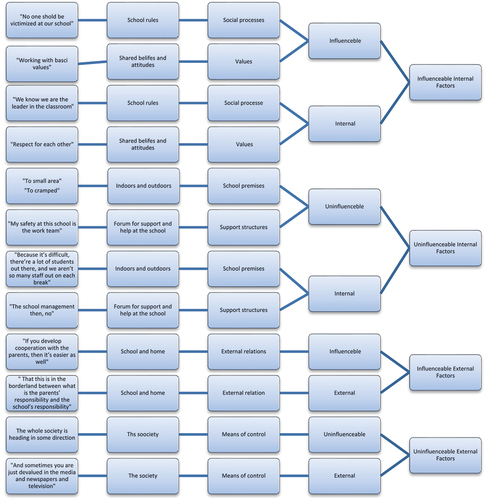

In this focused coding, focused codes were further developed and raised into categories with provisional definitions (Charmaz, Citation2014). By constantly comparing the focused codes and the emergent tentative categories, these were categorized into two dimensions: internal factors versus external factors and if they could be influenced or not influenced (see Figure ). Through theoretical coding that took place in parallel with focused coding, the relationships between our categories grounded in the focus group data were explored (Charmaz, Citation2014; Lindqvist & Forsberg, Citation2022). For example, we used Glaser’s (Citation1998) paired opposite coding family to construct the dimensions’ internal and external factors (and thus how certain codes were related to each other as paired opposites) (Figure ). In the coding process we adopted a social-ecological perspective as a loose frame (Charmaz, Citation2014) and treated its concepts as sensitizing (cf. Blumer, Citation1969) and used it as a tentative analytical tool to conceptualize the complexities and interaction of influencing factors addressed by the teachers, and the teachers’ apprehension of the possibility to influence these factors.

Figure 1. The coding process following a constructivist grounded theory approach including initial, focused, and theoretical coding, from quotation to conceptualizations.

Through the whole research process, constant comparative method was used, which means that we triangulated data, codes and categories to increase the trustworthiness of the analysis and findings. Moreover, investigator triangulation was built into the present study because the analysis and writing were based on collaborative teamwork (Flick, Citation2019), in-depth discussion and negotiated consensus (Bradley et al., Citation2007).

In the grounded theory tradition, the term “emergent fit” is sometimes used when broad concepts from the literature fit with the data and earned their way into the analysis (Thornberg, Citation2012). In our study, this happened with the concepts of internal and external factors and whether they were influencable or not as these different ways of attributions (i.e., how people explain or perceive causes of behaviors and events) can be find in the attribution theory literature (e.g., Graham & Folkes, Citation2016). Teachers’ understanding of what factors influenced the school climate of their school was a part of the their main concerns in their efforts to increase and maintain a good climate in the school and their classrooms. When we conceptualized their perspectives, we found that they considered how both internal and external factors influence the school climate. The teachers perceived these factors to be either possible to influence or not. The perceived factors influencing school climate represented different and interacting social-ecological aspects (individual and contextual factors). In line with the constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz, Citation2014), and through constant comparisons between data, codes, categories, and literature (Thornberg, Citation2012), concepts from the social-ecological perspective and the attribution theory that made an analytical fit with our data, codes, and categories have been adopted (Charmaz, Citation2014).

In accordance with grounded theory, we used an iterative approach, meaning that data gathering and analysis took place in parallel, with each informing the other, We moved back and forth between gathering and analysing data directed towards exploring and refining concepts that are emergent in the data, known as theoretical sampling (Charmaz, Citation2014).

5.4. Ethics

The ethical principles provided by the British Psychological Society guidelines (British Psychological Society BPS, Citation2014) and the Swedish Research Council (Citation2017), both emphasizing the concern for participants’ interests and right to confidentiality, have been applied throughout the study. All participating teachers gave their informed consent. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board at Linköping University (Dnr 2017/143-31).

6. Results

Across all focus groups, teachers described a well-functioning, sustainable and positive school climate as a safe and quiet school characterized by a high degree of well-being, good teaching, caring teachers, and where students and teachers thrive. For instance, the introduction of a shoe-free school policy (i.e. students and teachers had to take of their shoes indoors) at School A was suggested to have a positive influence on the school climate, as it dampened the noise level and made students less rowdy indoors.

Since we actually became a shoe-free school, it did a lot for the climate. I mean, you’re not that tough when you shuffle around in your socks. You don’t like to kick on the cupboard because it hurts worse when you are not wearing shoes. (lower secondary school teacher, School A)

However, we also found differences in teachers’ perspectives on the school climate dependent on where they worked (i.e. School A or School B, elementary or secondary school level, and personal experience). Their perceptions of their school climate varied from being overall good, quiet, and safe to be more tough and hard. The latter perception was more common among teachers in School A (i.e. the larger school that also included lower secondary school level), than among teachers in School B (i.e. the smaller school that only included elementary school level), and among secondary school teachers than among elementary school teachers.

According to the teachers, the quality of the school climate was influenced by various factors within and outside the school. Because they acknowledged the importance of a safe, orderly, respectful and supportive school, their main concern in co-creating a positive school climate was their efforts in influencing internal and external factors identified as having an impact on the school climate. This main concern was, in turn, linked to whether teachers apprehended that it was possible or not for them to influence various dimensions of internal and external factors that they believed had an impact on the school climate at their school.

6.1. Influenceable internal factors: social processes and values

The teachers argued that there was a number of social processes and values in the school that influenced their school climate, and some were perceived to be influenceable. Since the teachers simultaneously talked about school climate and classroom climate when they discussed internal factors considered influenceable to a varying extent, these factors also applied to the classroom climate. “I really think that classroom climate and school climate overlap each other, thanks to the fact that we [the teachers] are everywhere all the time” (upper elementary school teacher, School B). According to the teachers, school climate referred to the overall climate of the school but they viewed the classroom climate as a part of the school climate at the classroom level and consisted of between-classroom similarities and differences at the school. Even though, school climate does not equal classroom climate the teachers talked about them as if similar processes occurred at both levels. The result presents processes that the teachers described regarding both school- and classroom climate simultaneously. For instance, were shared beliefs, values and attitudes, as well as which academic climate should prevail at the school, highlighted in the teachers’ narratives regarding school- and classroom climate. These aspects became especially salient when the teacher addressed how they, at both schools on all levels, worked with values to improve and sustain a positive school climate. The desirable values at the school included, for instance, equal value for all students, and good behaviour towards everyone in school. “Working with basic values” (upper elementary school teacher, School B). “I work with the group and values there, how they [the students] are towards each other, for example” (lower secondary school teacher, School A). “And a little about respect for each other. Towards adults, towards each other as friends” (lower elementary school teacher, School B).

One way to facilitate and sustain a good school and classroom climate was, according to the teachers, to establish and enforce general rules for good behaviours in school. “But, in any case rules of order are: 1. No one should be victimized at our school, and if you are, you should tell an adult” (upper elementary school teacher, School A). Addressing the rules in the classroom and at the school was one way for teachers to work with the school climate. This included working with rules both about how to behave towards each other and rules with the aim of creating harmony/calm and order in the classrooms and at the school. Their “rule work” also included attending to the students’ use of language, since a nurtured language use, according to the teachers, was a clear sign of a good school climate.

The second influenceable internal factor affecting the quality of the school climate addressed by the teachers concerned how the academic environment should be at school and in the classroom. This internal factor included three subcategories: academic demandingness directed towards students, classroom management and teachers’ interaction with, and management of, students outside the classroom at school. The teachers apprehended that they, to a certain degree, influenced eligible values and the academic climate at both school and classroom level in a positive direction. They did that by acting as role models for their students and by intervening, managing and disciplining student behaviours that negatively affected the school or classroom climate. Acting as a leader, with all that it entailed, promoted, according to the teachers, a positive school and classrooms climate:

But at the same time, what we have in common, I think, is that we all feel that now we are the teachers.

Yes, exactly. We know that we are the leader in the classroom (lower secondary school teachers, School A).

In sum, enacting teacher authority in terms of classroom management but also outside the classroom, enforcing rules, acting as a good role model and intervening and disciplining inappropriate behaviours were, according to the teachers, efforts that positively affected the classroom climate and, by extension, and in collaboration with other teachers and school staff, the school climate.

6.2. Uninfluenceable internal factors: school premises and support structures

In addition to internal influenceable factors, teachers also discussed internal factors that they considered to be impossible to influence, namely school premises and support structures at the school.

The first uninfluenceable factor concerned school premises. The teachers argued that the design of school premises (i.e. buildings, grounds/surroundings and indoor spaces) affected the school climate both positively and negatively. They thought about the school premises as conditions that they had no control over. They were not in the position to affect or change the buildings, surroundings and so on. Some of the indoor premises that often came up in the discussion were corridors, cloakrooms and dining rooms. They were often problematized as “too cramped”, “too small an area”, and “a puzzle to ensure that not all students will be there at the same time”. According to the teachers, confined spaces promoted the emergence of different types of conflicts and, by extension, affected the school climate negatively. “And then there is a little space inside, it’s a bit crowded and sometimes with all off and on clothing … there is no space” (lower elementary school teacher, School A). “Or, thus, poorly adapted premises for large groups [of students], even though we are many adults [supervising breaks], the external circumstances are not optimal” (lower elementary school teacher, School A).

Considering the outdoor school context, lower and upper elementary school teachers were mainly occupied with the schoolyard—not in how it was designed, but in terms of difficulties in supervising the entire schoolyard. Supervising during breaks was addressed in terms of both positive and negative influence depending on whether the focus was on students’ or teachers’ school climate. “Because it’s difficult, there’re a lot of students out there, and we aren’t so many staff out on each break, so you kind of can’t know what’s going on everywhere in the schoolyard either” (school-age educare teacher, School B).

The teachers described a dilemma in relation to break supervision. If a larger number of staff was present on the schoolyard supervising the students during the breaks, it would promote school safety and rule-following behaviour and counteract peer aggression and victimization among students, but at the cost of teachers’ opportunities for having a short rest and pedagogical discussions with colleagues. While a growing amount of break supervision was found to influence school climate in a positive way on behalf of the students, it had—at the same time—a negative impact on teachers in terms of teacher stress (loss of rest and preparation time between lessons) and professional community-building (loss of interaction, conversation and pedagogical discussion with teacher colleagues).

We have to do more and more supervising during breaks every year.

Yes, it’s good for the breaks, but it’s worse for us. For us, thus, this natural connection to have a cup of coffee and talk during the break.

Yes, we have had to drop that.

We have had to skip that. We barely see each other.

Yes, because we try to make it better for the students.

Yes, and then it becomes a pedagogical loss as well, because even if we have a so-called break, you sit and talk about different things, and that opportunity has flown away for us now, because then we are supposed to spread out and supervise a break or do something else. It was a bit of what I was talking about as well, as that break supervision can actually be done by others [don’t need a teacher education for that]. (upper elementary school teacher, School A)

The number of teachers supervising during student breaks was, according to the teachers, dependent on the number of staff working at the school that specific day, thus dependent on absence or other commitments and thereby unimpressionable. Hence, more teachers supervising on the breaks could positively affect students’ school climate while at the same time influence the teachers’ school climate negatively.

Lower secondary school teachers at School A highlighted the unique opportunity that the manned leisure centre located in the middle of the school building offered, and its positive influence on the school climate. This meant that both the older students and adults were often nearby.

Then I think that our manned leisure centre is very valuable for noiseless school. That they [students] have somewhere to go. They don’t have to stand and hang in the corridors, because that’s also something that creates anxiety when they stand and hang in the corridors when you have to pass through. We don’t have noisy gangs hanging in the corridors, but they go to the leisure centre and hang out there, and there are always adults who see them. (lower secondary school teacher, School A)

The second uninfluenceable factor that, according to the teachers, had an impact on the quality of the school climate, was the internal support structures at the school, that is, the forum for support and help at the school that is accessible to the teachers. This included several agents and teams such as school management, student health team, school safety team, school nurse, school psychologist, trade union and the work team. The degree of availability and the sort of help and support they could offer were perceived to be beyond teachers’ influence. The teachers reported that the most usable support group for them was their own work team. Even though teachers could not influence the composition of the work team or how much time was allocated for teamwork, this was where they felt supported and safe.

No, so I, my safety at this school is the work team. That’s how it is. I don’t feel that I get it [support from the school and school management]. So purely crass, if I had problems, I wouldn’t turn to the school psychologist and so on, because there I know that I wouldn’t get any support. The school nurse, yes, I can go down there myself if there’s a student who I need to ventilate, then I’m listened to, and I know that things are taken seriously. The school management then, no, I would like to say not always. It varies very much from person to person. And at the same time, I know that they are still busy with their stuff. But that’s how it is; maybe there’s not always time. (upper elementary school teacher, School A)

Even if the teacher apprehended these internal factors as uninfluenceable, they described having strategies helping them to work with the preconditions that existed in a constructive way, to improve the social processes among students and thus improve the school climate. For example, the teachers tried to minimize the number of students in the corridors and cloakrooms, by allocating various times for breaks or dining room visits. Furthermore, the teachers recounted how they negotiated with the management to have more time set aside for working in the work team; that is where they believed their most important and rewarding work regarding school climate was performed.

6.3. Influenceable external factors: external relations

In addition, the analysis of the focus group data revealed that teachers apprehended that the quality of the school climate was affected by various dimensions of external factors, of which some were perceived to be receptive. External relations, especially the relation between school and home environment, were often addressed by the teachers as influenceable and important factors that emanated outside the school and influenced the school climate. A well-functioning collaboration with parents facilitated the ongoing work with the school climate, and vice versa. Acquiring parents committed and involved in their children’s schooling was important in promoting and maintaining a well-functioning school climate. “If you develop cooperation with the parents, then it’s easier as well. If you have them with you, and they know what happens [at school]” (upper elementary school teacher, School B). “Sometimes ‘we bang our head against a wall’ if we don’t get the support from home; if that they [the parents] are not interested or disparage what we do—then it’s uphill” (upper elementary school teacher, School B).

As the teachers disclosed, school climate is related to being supported by and cooperating with the parents. Another issue that teachers felt affected them, and in turn the school climate, was the expectations that some parents had on their children to receive high grades. “This is an area where a lot of parents expect their children to have A or B, and that can make you feel a little badly, because those are very high grades” (upper elementary school teacher, School B). Too high or unrealistic expectations from parents regarding their children’s achievements and grades put the teacher in an uncomfortable position. The teachers tried to deal with students’ stress, failures and negative emotions due to high demands from home by reducing the pressure on the students in school. “We [the teachers] expect you [the students] to be approved first and foremost and then we’ll see” (upper elementary school teacher, School B). The teachers emphasized that there was a fine line between what a teacher was allowed to interfere with and not, which had to do with parenting and parental responsibility, but in the long run can have significance for the school climate.

That this is in the borderland between what is the parents’ responsibility and the school’s responsibility. It goes without saying, I think, that you raise your child and set rules for what applies, but when they are bypassed, it’s not noticed until during the day, perhaps, that you’re tired, and it’s us who meet them during the day, but it isn’t us who set the boundaries at home. And then there will be a collision. You don’t want to meddle in about bedtime or screen times or eating habits or anything like that, but we notice that it affects the children here. But it’s kind of hard to say yes, but have to put your child to bed at this time and say that she or he falls asleep. (upper elementary school teacher, School B)

The excerpt above illustrates how leisure time activity spilled over and influenced the school climate (i.e. sleep, diet, screen time). Students’ use of social media is one example emphasized in the interview, often with a negative connation to the school climate. If a well-functioning relation between school and home environment has been established, there are usable strategies for collaboration between teachers and parents. The teachers refer to discussions in lectures, at parent meetings and through dialogues during development conversation meetings between teachers, parents and students as eligible strategies for enhancing the quality of the school climate. In Sweden, a teacher has an annual meeting with a student and their parents—a so-called “developmental conversation meeting” – to discuss the student’s progress and learning in school. “We have brought it up in development conversation meetings and talked about sleep: do we sleep properly at home? Do we eat properly at home? How much screen time do we have? Are there lots of other activities?” (upper elementary school teacher, School B).

The teachers also highlighted that they apprehended they could influence these external factors through conducts and rules in the school, for instance by regulating the time spent using electronic devices and social media in school and thereby facilitating and sustaining a positive and well-functioning school climate for everyone at the school.

6.4. Uninfluenceable external factors: external means of control

The findings also disclosed a certain amount of teachers’ resignation when they described how external influencing factors, at the societal level (external means of control) and beyond their control, significantly influenced the possibility of facilitating and sustaining a positive and well-functioning school climate for everyone at the school. The school is situated in a society that is heading in a certain direction:

The whole society is heading in some direction that is hard for us to grasp. Or we have not used the right tools over the years, and now we have to collect them somehow. And I think we probably fumble our way. (upper elementary school teacher, School B)

We are here because we like the profession and we want to … and sometimes you are just devalued in the media and newspapers and television and among parents, instead of helping one another with these groups. Helping each other to get things going in the right direction. (lower elementary school teacher, School A)

School political decisions, economy, national school policies and the school debate in media at the macro level, along with local school political decisions, economy and regulations at the exo- and meso level, were perceived to impact the local school climate in a way that was beyond the teachers’ control. “Things happen one after the other. It’s this new curriculum and programming that is a fact” (lower secondary school teacher, School A). Too many reforms and too little resources decreased their sense of professional agency and control and increased their teacher stress and a sense of professional inadequacy (i.e. not being able to live up to their own professional standards, see Lindqvist et al., Citation2017) that altogether interfered with their efforts in creating a good school climate. The uninfluenceable external factors also included news flashes and official statistics that put schools (and teachers) in a bad light. “Although that is a problem for the Swedish National Agency for Education, the school management has to deal with that, unfortunately” (upper elementary school teacher, School A). “We measure. This is mostly what is talked about when there are examinations based on PISA [Programme for International Student Assessment]” (upper elementary school teacher, School B).

Teachers in the present study also argued that the Swedish free-market competition and choice approach to schools had a negative impact on the school climate through its negative influence on teachers and other school staff. It generated an always present threat from dissatisfied parents to change school: “do something about it or we will move our children” (upper elementary school teacher, School A). This external factor affected what measures staff dared to take or not to take within the school.

No, the threat to change school is present. Yes, and the principals are afraid to take action because then they lose money, student money, and then they have to get rid of staff and then it does not work here. (upper elementary school teacher, School A)

As elucidated in the excerpt, the worrisome threat constituted by the free school choice was closely associated with another strong incentive, namely economy. The schools’ economies had, according to the teachers, a significant impact on the school climate of their school. “Then it’s the economy that also governs” (school-age educare teacher, School B). “Yes, both voluntary and involuntary mobility between schools, which is completely open today, it’s completely crazy” (upper elementary school teacher, School A). The teachers experienced that the open mobility and turnover between schools had created an unsustainable economic situation influencing the school and classroom climate negatively. Not knowing which colleagues and students were attending the school continuously entailed an uncertainty that effected the teachers’ opportunities for professional work.

At the local level, teachers talked about student population (i.e. students’ socioeconomic background, the proportion of socially disadvantaged students and whether the school included elementary and/or secondary students) as factors that could facilitate or challenge the efforts in creating and maintaining a positive school climate.

Then we have quite a lot of segregation here as well. There are two independent schools apart from our school, so we have three elementary schools that students also move between, which means that sometimes there isn’t a really good composition of the classes.

No, and we have been considered a “bottle funnel” as well. We are the school you opt out of in the first place.

It’s the rough municipal school.

Yes, and then it’s the other, partly I think it’s that we include a lower secondary school, which makes many parents [of the younger students] feel a little worried. Yes, so we are the ones where you see most segregation and have been so for a long time. I think it has begun to get tougher at the other schools as well.

The free choice of school is a huge reason for this, according to my point of view.

Yes, it’s useless. (upper elementary school teacher, School A)

As another side effect of the free-market competition and choice approach to schools, the teachers highlighted that a public school, in contrast to a private school, was obligated to accept all students whenever they were enrolled during the school year. “We must always accept students” (upper elementary school teacher, School A) regardless of student characteristics (i.e. special needs, mother tongue, moved around a lot etc.), which affected mobility and turnover in the classes. For example, too many students in the class created a sense of professional inadequacy and made it harder to create a positive classroom climate and student safety. “There are very large classes in first grade. Difficult to be sufficient” (lower elementary school teacher, School A). When various organization changes happened to often, it interfered with teachers’ work with school and classroom climate.

But there have been many changes in the organization from the last autumn, and even during the academic year it has been necessary to change due to various new conditions. And it’s noticeable that it gets messier in the groups. (school-age educare teacher, School A)

Some teachers also mentioned teacher education as an uninfluenceable external factor, and how it insufficiently prepared prospective teachers in beliefs, values and attitudes consistent with what the teachers in the study described as necessary in a well-functioning, sustainable and positive school and classroom climate. “You realize that a lot are lacking in teacher education, in other words, how you are in a classroom, how you treat students, how to resolve a conflict” (upper elementary school teacher, School B).

6.5. A grounded theory of teachers’ perceptions of factors influencing school climate

By crossing the two dimensions internal–external and influenceable—uninfluenceable, we identified four types of factors affecting the quality of the school climate according to the teachers’ perceptions and experiences: social processes and values in school (i.e. influenceable internal factors), school premises and support structures (i.e. uninfluenceable internal factors), external relations (i.e. influenceable external factors) and external means of control (i.e. uninfluenceable external factors) (see Figure ).

Figure 2. A grounded theory of teachers’ perceptions of factors influencing school climate. Concepts from Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994) and the four domains of school climate (Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016) have been integrated in the theoretical model.

In line with previous research (Mitchell et al., Citation2010), social processes and values in school were emphasized as prominent influenceable internal factors affecting the school climate (left upper corner in Figure ), illustrating the importance of quality and consistency of interpersonal interactions within the school (Fan et al., Citation2011). These factors were connected to both micro- and mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), referring to how beliefs, values and attitudes as well as academic climate were factors shaped by reciprocal interactions between teachers, staff and students (microsystem) and between different environments at the school, for instance the classroom and schoolyard (mesosystem). Furthermore, these influenceable internal factors corresponded to three of four school climate domains, that is the academic (i.e. classroom climate), community (i.e. interpersonal relations) and safety domains (i.e. physical and emotional safety) (Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), featuring preconditions for facilitating and sustaining a positive school climate. One important finding was that the teachers apprehended these factors as possible to influence, and thereby, if necessary, conceivable to change in a desirable direction. For instance, as the desirable values at the schools included equal value for all students and good behaviour towards everyone in school, the teachers believed they actively could work towards these desirable values to improve and sustain a positive school climate.

More stable uninfluenceable internal factors that the teachers associated with quality of school climate were school premises and support structures (upper right corner in Figure ). Like the influenceable internal factors, these factors were also connected to both micro- and the mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994; Wang & Degol, Citation2016) and referred to how school premises affected the quality of the school climate. For instance, several teachers at school A emphasized how the centrally located leisure centre had a positive influence on the quality of the school climate. On the other hand, cramped school premises affected the quality of school climate negatively by, for instance, promoting the emergence of conflicts, fights and peer victimization. In the teachers’ report, we found that the institutional environment and safety domain (Cohen et al., Citation2009; Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016) as preconditions for school safety were dependent on the environmental organization of the school. Thus, it was considered a factor with great impact on the school climate that teachers apprehended as uninfluenceable.

An interesting finding was the teachers’ discussion on supervision of the schoolyard as means to both positive and negative influence on the school climate, depending on whose perspective was highlighted. More supervision during recess could positively affect the students’ school climate by increasing students’ sense of safety. However, it could at the same time decrease the quality of the school climate from teachers’ point of view, as it minimized their time to socialize with each other in between the lessons (cf. Horton et al., Citation2020). Another noticeable comment from teachers, in one of the focus group interviews (upper elementary school teacher, School A), was whether “break supervision can be done by others”. This indicated an assumption that school staff do not need to exercise any pedagogical leadership during breaks. This despite the fact that several studies have shown that the breaks, in particular, often gave rise to situations that need to be addressed and solved by pedagogically skilful professionals (Fram & Dickmann, Citation2012; Horton et al., Citation2020; Mulryan-Kyne, Citation2014; Woolley, Citation2019).

In contrast, poor management of fights, conflicts, teasing, bullying, ostracism and harassments among students would create a “hidden curriculum” (cf., Jackson, Citation1968) on the schoolyard and in the school corridors. Such “hidden curriculum” might, in turn, teach and mediate values, norms and social behaviours contrary to the formal curriculum of school, and thus in conflict with moral, democratic and prosocial values, norms and behaviours, such as caring, respect, fairness and compassion (cf. Campbell, Citation2003; Lovat et al., Citation2010; Nucci & Ilten-Gree, Citation2021). Additionally, if school staff fail to deal with negative, violent and degrading (inter)actions between students in an effective and pedagogical manner during the break, the students would probably be, as the teachers in the study argued, transferred into the classroom after the break and thereby affect the classroom climate negatively.

Internal support structures varied a bit between the two schools (e.g. availability and composition of school management, student health team, school safety team etc.). The common denominator, however, was that teachers from both schools emphasized that they could not influence what support functions were available. However, the teachers asserted that the own work team were the most usable and appreciated support group. Even though the teachers appraised that these internal factors were impossible or next to impossible to change, the narratives depicted that the teachers had developed strategies to cope with the preconditions that existed in a constructive way.

External relations, especially the relation with the students’ home environment, were a prominent, impressionable factor that teachers perceived could influence the school climate in both directions (lower left corner in Figure ). The relation between school and home refers to the mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), featuring preconditions aligned with the community domain (Cohen et al., Citation2009; Gase et al., Citation2017; Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016). As the teachers highlighted, a good relationship with the students’ home environment was an important prerequisite that could influence the quality of the school climate in both directions. A well-functioning, reciprocal collaboration with parents favoured the school climate, and vice versa.

Although the teachers felt that it was possible to actively work with the relationship between home and school (external factor possible to influence), the teachers’ expressed some doubt apropos their authority compared to parents’ right to raise their children. Where is the boundary between parental responsibility and teachers’ opportunity to influence? Students’ use of social media was one example often raised in the narratives, frequently with negative connation, since excessive use of screen time often led to late nights and less sleep, which spilled over to the next school day; hence tired students influenced the school climate negatively.

The teachers disclosed a sense of resignation when they described uninfluenceable external factors that they associated with quality of school climate in terms of external means of control (lower right corner in Figure ). This refers to factors beyond the teachers’ control and aligned with exo-, macro- and chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), in other words, how neighbourhood and municipality (exosystem), society (macrosystem) and historical changes (chronosystem) in the exo- and macrosystems significantly affected the school climate in a positive or negative way. Student population, school organization and the free-market competition and choice approach to schools were often highlighted by the teachers and can be considered as preconditions connected to the institutional environment domain (Cohen et al., Citation2009; Gase et al., Citation2017; Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016). According to the teachers, these factors affected mobility and turnover in both schools and were closely connected to the school’s economy, and thereby, by extension, had a significant impact on the teachers’ continuous work of promoting and maintaining a positive school climate.

7. Discussion

In accordance with the school climate literature (Cohen et al., Citation2009; Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), the teachers in our study employed a multidimensional perspective. Their explanations of the school climate, as emanated by a complex interplay among multiple agents and contexts both inside and outside the school, can be related to the social-ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), and linked to four domains of school climate in the literature: academic climate, community, safety and institutional environment (Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016).

In the present study, the teachers described a good school climate in terms of a safe and quiet school, characterized by well-being, good teaching and caring teachers, where students and teachers thrive. These findings are in line with the school climate literature (Cohen et al., Citation2009; Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), previous qualitative findings on teachers’ perspectives (Harris et al., Citation2021; Jessiman et al., Citation2022; Pandia & Purwanti, Citation2019; Walls et al., Citation2021; Zaatari & Ibrahim, Citation2021), and previous qualitative findings on students’ perceptions of school climate (Thornberg et al., Citation2022), Further, they acknowledged that people (e.g. parents, municipal officials) and parameters (e.g. policy instruments, media) outside the school affected the quality and experience of the school climate (cf. Cavrini et al., Citation2015; Cohen et al., Citation2009; Garzia & Molinari, Citation2021; Horton et al., Citation2020). Our findings suggested that the teachers’ main concern in co-creating a positive school climate was their efforts in influencing internal and external factors identified as having an impact on the school climate. That made them inclined to interpret and consider the influenceability of internal and external factors, in other words, to what degree they could influence the influential factors.

We constructed a grounded theory of teachers’ perceptions of factors influencing school climate that consisted of two dimensions, internal—external and influenceable—uninfluenceable, and four types of factors: social processes and values in school (i.e. influenceable internal factors), school premises and support structures (i.e. uninfluenceable internal factors), external relations (i.e. influenceable external factors) and external means of control (i.e. uninfluenceable external factors). Even though the teachers considered uninfluenceable internal and external factors as more or less out of their control, there was a difference between how they talked about them. They expressed a sense of resignation in relation to uninfluenceable external factors, as they were taken for granted as impossible or next to impossible to change. In contrast, the teachers talked about uninfluenceable internal factors in a more constructive way and had developed strategies (i.e. through school and classroom rules and by allocating various times for break times) to cope with the preconditions that existed regarding uninfluenceable internal factors. By examining and theorizing on what teachers perceive influencing school climate and whether they are able to influence these factors, the present study proposes a hypothetical model on teachers’ perceptions of their agency or capacity in establishing and maintaining a positive school climate.

8. Limitations

Some limitations in respect of our study should be noted. First, the results rely on focus group interview data, which are vulnerable to social desirability, recall and perception biases. Interview data can be problematic in terms of ecological validity. In other words, what the teachers say happens and what actually happens in their everyday real-life setting would not necessarily be the same. In order to strengthen the ecological validity, ethnographic observations of school climate, and how possible factors within and outside school are influencing school climate, are suggested as further steps. Nevertheless, in accordance with a constructivist position of grounded theory, we do not claim to offer an exact picture but rather an interpretive portrayal of the phenomenon studied (Charmaz, Citation2014). Secondly, as the data were collected in a group context, this could have influenced the data, with compromised views or dominant voices becoming prevalent in the findings. On the other hand, focus group data are considered to be more ecologically valid than individual interview data because the participants are talking, discussing and interacting in their natural groups, representing their everyday microsystem context.

All together, because our findings are based on self-reported focus group data, the current findings are limited to our interpretation of their perspectives and are not able to represent the full complexity of interactions between various contextual systems and individual factors, as discussed by Bronfenbrenner (Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1994). Thus, further studies need to use multiple sources (e.g., students, parents, principals, stakeholders, policy documents, and local and national statistics) and multiple data collection methods (e.g., interviews, questionnaires, and ethnographic observations in classrooms, schoolyards, staff rooms and decision-making meetings in different system levels within the educational system).

Third, the small and non-probability sample of teachers from two different schools in a particular area of Sweden reflects the unique contextual factors but, at the same time, limits the generalizability of the findings. However, instead of claiming statistical generalisation built upon the logic of mathematics, in qualitative research, generalisation has been discussed in different terms. For example, Larsson (Citation2009) discusses generalisation through context similarity and generalisation through recognition of patterns, in which the reader, not the researcher, judges the generalisability. “The reader is invited to notice something they did not see before” (Larsson, Citation2009, p. 33), and to interpret whether the findings are useful in another similar context and whether the patterns in the findings are recognizable in the school context and the teacher population with whom the readers primarily work or are interested in. In accordance with the pragmatist epistemology underlying constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, Citation2014; Lindqvist & Forsberg, Citation2022), we argue that our findings are partial, provisional and fallible interpretations. They are not a fixed endpoint but are constantly open for modification as new data are gathered (Glaser, Citation1998). Thus, our middle-range grounded theory should be seen as a working model that has to take into account the actual but changeable context and the local conditions. This reminds of Cronbach’s (Citation1975) stance when he argued that, “When we give proper weight to local conditions, any generalization is a working hypothesis, not a conclusion” (p. 125). Thus, future research needs to examine how teachers in other school settings and cultural contexts interpret and explain school climate, influencing factors, and how they work to create a positive school climate while addressing various influencing factors.

9. Conclusion and practical implications

Teachers, with their unique key position in schools, possessed crucial information and thereby contributed new information regarding some gaps in the research field on school climate. This study was the first to examine teachers’ perspectives on factors influencing the school climate with a qualitative research design. This study highlights that the teachers talked about school climate as a multidimensional and malleable phenomenon, emanated by a complex interplay across multiple agents and contexts both within and outside the school, aligning with all domains and features acting as preconditions for the school climate. By analyzing the focus group data, we developed a grounded theory of teachers’ perspectives of factors influencing school climate that conceptualizes the complexities and interactions of influencing factors addressed by the teachers, and their apprehension of the possibility to influence these factors.

The results also serve as a means for practical implications, as they illustrate and conceptualize teachers’ beliefs about what builds a school climate, what they can do about it and what they consider to be out of their control. The constructed grounded theory and its concepts provides a professional language of how school climate is developed. Thus, the findings give tools to identify, name, communicate and discuss processes that promote a more conscious and professional work with the social climate in school and in the classrooms. Moreover, the findings provide the school management with teacher-based knowledge featuring preconditions for facilitating and sustaining a positive school climate. By enhancing the teachers’ comprehension of which factors actually are influencing the school climate, school management staff can address and support teacher efforts and direct their own efforts at the factors having the greatest benefit on the school climate. In addition, our findings provide a model to help the school management to identify and address factors beyond teachers’ control.

The study also shed some light on contemporary societal discussions and about what characterizes the responsibility of the school. Notwithstanding, highlighted in this study, there are factors outside the school influencing the school climate which are beyond the influence of the school and teachers. Accordingly, teachers should be aware of that they can not solve all obstacles regarding the school climate, other agents must also play their part in participate in this important mission. Focusing on the positive and what can be influenced can support the teachers’ engagement in facilitating and sustaining a positive and well-functioning school climate for everyone at the school.

Etical

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board at Linköping University (Dnr 2017/143–31).

Acknowledgments

The authors will give a special thanks to the teachers for their valuable contributions in this study; without their participation, no study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eva Hammar Chiriac

Eva Hammar Chiriac is a professor of Psychology at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Sweden. Her scientific activity lies within the social psychological research field with a strong focus on group research, mainly connected to groups, group processes, learning and education. Her current research project concerns group work assessment, school climate and relations in schools, and problem-based learning.

Camilla Forsberg

Camilla Forsberg is a senior lecturer in Education at the Department of Behavioral sciences and Learning, Linkoping University, Sweden. Her current research explores the relationships between schooling, gender and school bullying in Swedish schools. Other research areas include students’ and teachers’ perspectives on school climate and relations in school.

Robert Thornberg

Robert Thornberg is a professor of education at the Department of Behavioral sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Sweden. His current research is on school bullying, especially with a focus on social and moral processes involved in bullying, bystander rationales, reactions and actions, and students’ perspectives and explanations. Other research areas include social climate and relations in school, values education, and student teachers’ emotionally distressing educational situations.

References

- Aldridge, J. M., & McChesney, K. (2018). The relationships between school climate and adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Research, 88, 121–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.01.012

- Berkowitz, R., Bar-On, N., Tzafrir, S., & Enosh, G. (2022). Teachers’ safety and workplace victimization: A socioecological analysis of teachers’ perspective. Journal of School Violence, 21(4), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2022.2105857

- Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2017). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425–469. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316669821

- Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic Interactionism. University of California Press.

- Bradley, E. H., Curry, L. A., & Devers, K. J. (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42(4), 1439–1796. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

- British Psychological Society (BPS). (2014.) Code of Human Research Ethics. Retrieved May 9, 2021. https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/bps-code-human-research-ethics-2nd-edition-2014

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In T. Husen, & T. Postlethwaite (Eds) The International Encyclopedia of Education (2nd ed.) (Vol 3, pp.1643–1647). Elsevier

- Campbell, E. (2003). The ethical teacher. Open University Press.

- Cavrini, G., Chianese, G., Bocch, B., & Dozza, L. (2015). School climate: Parents’, students’ and teachers’ perceptions. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Science, 191, 2044–2048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.641

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

- Cohen, J., McCabe, L., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. The Teachers College Record, 111(1), 180–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810911100108

- Cronbach, L. J. (1975). Beyond the two disciplines of scientific psychology. American Psychologist, 30(2), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076829

- Demirtas-Zorbaz, S., Akin-Arikan, C., & Terzi, R. (2021). Does school climate that includes students’ views deliver academic achievement? A multilevel meta-analysis. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(4), 543–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2021.1920432

- De Smul, M., Heirweg, A., Geert, D., & Van Keer, H. (2020). It’s not only about the teacher! A qualitative study into the role of school climate in primary schools’ implementation of self-regulated learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31(3), 381–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1672758

- Enkhtur, O., Gruman, D. H., & Munkhbat, M. (2022). ‘Put Students’ dreams first’: Student perspectives on secondary school climate improvement in Mongolia. School Psychology International, 014303432211472. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343221147268

- Fan, W., Williams, C. M., & Corkin, D. M. (2011). A multilevel analysis of student perceptions of school climate: The effect of social and academic risk factors. Psychology in the Schools, 48(6), 632–647. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20579

- Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research (6th ed.). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529622737

- Flick, U. (2019). From intuition to reflexive construction: research design and triangulation in grounded theory research. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The sage handbook of current developments in grounded theory (pp. 125–144). Sage.

- Forsberg, C., Hammar Chiriac, E., & Thornberg, R. (2021). Exploring pupils’ perspectives on school climate. Educational Research, 63(4), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2021.1956988

- Forsberg, C., Hammar Chiriac, E., & Thornberg, R. (2022). “I think we have a good time if there are no disputes”: pupils’ dynamic perspectives on being on breaktime. Educational Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2022.2120763

- Fram, S. M., & Dickmann, E. M. (2012). How the school built environment exacerbates bullying and peer harassment. Children, Youth and Environments, 22(1), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1353/cye.2012.0027

- Fraser, B. J. (2012). Classroom learning environments: retrospect, context and prospect. In B. J. Fraser, K. G. Tobin, & C. J. McRobbie (Eds.), Second international handbook of science education (Vol. 1, pp. 1191–1239). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9041-7_79

- Garzia, V., & Molinari, L. (2021). School climate multidimensionality and measurement: A Systematic literature review. Research Papers in Education, 36(5), 561–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1697735

- Gase, L. N., Gomez, L. M., Kuo, T., Glenn, B. A., Inkelas, M., & Ponce, N. A. (2017). Relationships among student, staff, and administrative measures of school climate and student health and academic outcomes. The Journal of School Health, 87(5), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12501

- Giraldo-García, R. J., Fogerty, L., Sanders, S., & Voight, A. (2023). Urban secondary students’ explanations for the school climate-achievement association. Psychology in the Schools. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22872

- Glaser, B. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Sociology Press.

- Graham, S., & Folkes, V. S. (2016). Attribution Theory. Psychology Press.

- Harris, R., Wilson-Daily, A. E., & Fuller, G. (2021). Exploring the secondary school experience of LGBT+ youth: An Examination of school culture and school climate as understood by teachers and experienced by LGBT+ students. Intercultural Education, 32(4), 368–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2021.1889987

- Heinla, E., & Kuurme, T. (2022). The impact of school culture, school climate, and teachers’ job satisfaction on the teacher-student relationship: A case study in four Estonian Schools. Research Papers in Education, 1–27. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2022.2150883

- Horton, P., Forsberg, C., & Thornberg, R. (2020). “It’s hard to be everywhere”: Teachers’ perspectives on spatiality, school design and school bullying. International Journal of Emotional Education, 12(2), 41–55.

- Jackson, P. W. (1968). Life in classrooms. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Jessiman, P., Kidger, J., Spencer, L., Geijer-Simpson, E., Kaluzeviciute, G., Burn, A.-M., Leonard, N., & Limmer, M. (2022). School culture and student mental health: A qualitative study in UK secondary schools. BMC Public Health, 22(1), Article 619. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13034-x

- Konishi, C., Wong, T. K. Y., Persram, R. J., Vargas-Madriz, L. F., & Liu, X. (2022). Reconstructing the concept of school climate. Educational Research, 64(2), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2022.2056495

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2014). Focus groups. A practical guide for applied research (5th ed.). Sage.

- Larsson, S. (2009). A pluralist view of generalization in qualitative research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 32(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437270902759931

- Lenz, A. S., Rocha, L., & Aras, Y. (2021). Measuring school climate: A systematic review of initial development and validation studies. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 43(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-020-09415-9

- Lindqvist, H., & Forsberg, C. (2022). Constructivist grounded theory and educational research: Constructing theories about teachers’ work when analysing relationships between codes. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 46(2), 200–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2022.2095998

- Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., Wernerson, A., & Thornberg, R. (2017). Resolving feelings of professional inadequacy: Student teachers’ coping with distressful situations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64, 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019

- London, R. A., Westrich, L., Stokes-Guinan, K., & Mclaughlin, M. (2015). Playing fair: The contribution of high-functioning recess to overall school climate in low-income elementary schools. Journal of School Health, 85(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12216

- Lovat, T., Toomey, R., & Clement, N. (Eds.). (2010). International research handbook on values education and student wellbeing. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8675-4

- Mitchell, M. M., Bradshaw, C. P., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Student and teacher perceptions of school climate: A multilevel exploration of patterns of discrepancy. Journal of School Health, 80(6), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00501.x

- Mulryan-Kyne, C. (2014). The school playground experience: Opportunities and challenges for children and school staff. Educational Studies, 40(4), 377–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2014.930337

- National School Climate Council. (2007). The school climate challenge: Narrowing the gap between school climate research and school climate policy, practice guidelines and teacher education policy. http://www.ecs.org/school-climate

- Newland, L. A., Mourland, D., Strouse, G., DeCino, D., & Hanson, C. (2019). A phenomenological exploration of children’s school life and well-being. Learning Environments Research, 22(3), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-019-09285-y

- Nucci, L. P., & Ilten-Gree, R. (2021). Moral education for social justice. Teacher College.

- Pandia, W. S. S., & Purwanti, M. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions of school climate in inclusive schools. Psikohumaniora, 4(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.21580/pjpp.v4i1.3357

- Reaves, S., McMahon, S. D., Duffy, S. N., & Ruiz, L. (2018). The test of time: A meta-analytic review of the relation between school climate and problem behavior. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 39, 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.01.006

- Steffgen, G., Racchia, S., & Viechtbauer, W. (2013). The link between school climate and violence in school: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(2), 300–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.12.001