Abstract

By the beginning of 2020, there were widespread school closures caused by the spread of coronavirus for an unknown duration. Consequently, many schools turned to online learning using a software application, or a video conferencing system. As high levels of self-directed learning (SDL) are important for the quality of online learning, the present study aimed to understand learner SDL in an online environment and identify its challenges and barriers at one of the higher education institutes in Oman. It addressed a case study that documented how learning went in three online courses and reported perceptions of learners pertaining to effective SDL. Data were collected through interviews with seven selected students from each course, virtual observations of online teaching, and course documents. Results revealed four issues related to students’ SDL in online classes: 1) student cognitive engagement with online learning, 2) student-centered approach, 3) time-management and 4) student emotional engagement with online learning. The findings suggest a need to design an effective online learning environment through reinforcing students’ satisfaction and motivation in online classes, their time management skill, a student-centered approach and teacher presence.

1. Introduction

Given the increasing number of online learners, SDL is critical for enhancing learners’ performance (Chou, Citation2012; Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Glenn, Citation2016; Kebritchi et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2014; Rohs & Ganz, Citation2015, Xie et al, Citation2019; Zhu, Citation2021), which is widely defined as the learners’ beliefs and determination of their ability to successfully take charge of their own learning process (Knowles, Citation1975). Previous research has emphasized that learners with high levels of SDL ability are more motivated and willing to learn online and more determined to employ any resources to deal with their learning challenges and obstacles (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Glenn, Citation2016; Kebritchi et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2014; Xie et al., Citation2019). Conversely, it also affirms that SDL may create a disadvantage to those learners who think that the online learning environment requires less work. Therefore, to take the full advantage of online learning, there is a need to motivate virtual learners to be responsible for their own learning. Kim et al. (Citation2014) found that the learners’ SDL abilities improve when learners are more proactive in planning, organizing, and monitoring their activities.

However, considering that online learning occurs in unlimited time and space, the characteristics and effects of SDL in online education may differ. For example, it is often the case that face-to-face teaching requires students to follow a linear sequence in their learning; while in the online scenarios, learners have more flexibility in their learning choices over content, location, timing, and path. This higher responsibility may be a plausible reason why the attrition rates for online learners is 10% to 30% higher than face-to-face learners (Bouhnik & Marcus, Citation2006; Carr, Citation2000; Dutton & Perry, Citation2002). The students may need more support and preparations with SDL in an online environment. Therefore, there is a need to reconsider the concept and dimensions of SDL in the online environment to better understand how to raise its level among online learners.

Henceforth, this study attempts to investigate SDL in an online environment and identify the dimensions that impact this type of learning in an online context to assist the institute and teachers in changing their policies, teaching methods, and levels of support that will lead to improvement of learning conditions. SDL involves creating changes in all components of teaching and learning. Many empirical studies have been conducted to examine the practices of instructors in online environments, such as faculty roles, translating face-to-face courses to online, teaching styles, and time management. However, few studies (as will be shown in the sections below) have provided a comprehensive overview and synthesized prior studies on issues related to the dimensions and the extraneous influences that would affect SDL in an online context. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify and confirm challenges and issues influencing students’ SDL in an online environment and provide some suggestions to address the issues for online teachers and learners.

2. Literature Review

Researchers have signified the need to support learner SDL skills to enhance their performance. In the original research of Knowles (Citation1975), who was a pioneer to explore SDL, it is stated that higher education learners need to “take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies and evaluating learning outcomes” (p.18). This concept of SDL was further classified by several researchers (e.g. Chou, Citation2012; Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Durnali, Citation2020; Geng et al., Citation2019; Glenn, Citation2016; Kebritchi et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2014, Merriam, Citation2001; Song & Hill, Citation2007; Zhu et al., Citation2020) into different students’ learning needs and personality characteristics. Merriam (Citation2001), for instance, described SDL as a personal attribute of learners, which has been further classified into different characteristics, such as motivation, strategy use, and resource use (Song & Hill, Citation2007). SDL is also linked to different variables such as level of education, learning style and life satisfaction (Merriam etal., Citation2007). People with a high level of SDL should also be able to solve problems related to management and knowledge acquisition (Merriam et al, 2007). All of these definitions and classifications indicate that students’ SDL abilities are reinforced by practising a set of activities (listed above) iterated to meet the basic principle underlying SDL, which is that learners take an active role in their learning from the planning to the executing and evaluating their own learning endeavor instead of passively following teacher instructions.

However, learning in an online scenario may be more self-directed because it happened in unlimited time and space. In traditional teaching, students are usually required to follow a linear sequence in their learning. However, online-based instruction systems permit more flexibility in their choices, such as where, how, when, and with what activities or content they involve with. In recent years, researchers have increasingly paid attention to the characteristics of SDL in an online environment (Bonk et al., Citation2015; Zhu & Bonk, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2020; Zhu et al., Citation2020). They suggest that flexibility in online learning may require students to follow a more individualized approach to manage their learning and make their own learning decisions. In particular, students need to take responsibility for directing and guiding their learning experience, process, and activities in terms of coverage of content and depth of studying.

The flexibility may also evolve students to take more responsibility for time-management which refers to students managing and scheduling their study time (Alario-Hoyos et al., Citation2017). In fact, a lack of schedule and guidance from instructors in online learning can lead to poor time commitment which involves how long students study and when to study (Andrade & Bunker, Citation2009; Deimann & Bastiaens, Citation2010; Hromalik & Koszalka, Citation2018; Xie et al., Citation2019; Zhu, Citation2021). Indeed, some researchers assert that online classes require students to devote more time and effort than usual (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Glenn, Citation2016; Song & Hill, Citation2007).

The importance of time management in online learning has been widely referred to by some educators. Research has indicated that lack of time management skills may result in lower academic achievement (Nawrot & Doucet, Citation2014; Zheng et al., Citation2015) as well as procrastination (Rabin et al., Citation2011; Richardson et al., Citation2012) which itself is negatively related to life satisfaction (Deniz, Citation2006), stress and anxiety in academic study (van Eerde, Citation2003), especially in online education (Klingsieck et al., Citation2012). Lack of time management may also lead students to use the cognitive and metacognitive strategies for learning ineffectively (Howell & Watson, Citation2007; Wolters, Citation2003). The study of Kizilcec et al. (Citation2016) further verified the importance of time management skill for SDL. Their study showed that the students who demonstrated high time management skills completed their online learning successfully.

Research has shown that teachers need to support students in improving their time management and avoid procrastination through setting deadlines and tracking their use of time (Andrade & Bunker, Citation2009). However, the teacher role is a critical issue in SDL. There is a general consensus that one of the effective strategies that leads to high levels of SDL is the student-centered approach in which the core of online learning design is centered on learners who control their own pace and choose what and how they want to learn, rather than passively receive instructions from their teacher (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2014; Zhu et al., Citation2020). The research stressed the importance of encouraging students’ initiative, and helping them work together, rather than controlling and managing learning for them. Some researchers urge teachers to minimize their learners’ higher expectations by clearly communicating the course policies and rules at the beginning (e.g. Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Kebritchi et al., Citation2017; Xie et al., Citation2019). These researchers have a concern that learners’ expectation may be challenging when teaching online higher education courses in that students may expect instant feedback on their online assignments and consequently they may appear rude and demanding in their emails or they may even question their grades

Nevertheless, since students are separated from their teacher and their peers by a computer screen, it could be argued that we may need to look at teacher presence in the online environment from a different perspective. In traditional classroom, it is typically easier to follow-up and scaffold students in their SDL because both teachers and their students are in the same room together. However, with less face-to-face interaction on their work, teacher support and supervision may require a bit more effort in an online setting. Without sufficient guidelines and scaffolding from teachers, students may struggle to control and interact with an online learning environment. Indeed, in a study carried out by Denis (Citation2003), it is stressed out that online learners need more guidance and support on regulating their own learning processes compared to those students in traditional learning environments. In support, previous research has emphasized that in order to help students develop their SDL skills in an online environment, teachers should guide them to evaluate their own learning, articulate their learning goals and explore learning strengths and areas for improvement (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Dixson, Citation2010; Glenn, Citation2016; Sumuer, Citation2018).

Teacher support may be mostly needed to enhance student cognitive engagement with online learning. Online learners may feel lost and do not know how to control their own learning due to the increased cognitive load, especially if teachers do not consider creating clearly-organized and well-explained learning activities when translating a course into an online content. Melissa (Citation2015), shares that many instructors simply post their material (articles, web links, etc.) assuming that these would be enough to allow students grasp complicated concepts easily, and hence be able to process and apply their online learning effectively. Previous research has stressed out the essence of teacher presence as the foundation of student cognitive engagement with online learning (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Ingulfsen et al., Citation2018; Joksimović et al., Citation2015; Molinillo et al., Citation2018; Rotgans & Schmidt, Citation2011).

Finally, SDL could be also affected by student emotional engagement with online learning. It has been declared earlier that motivation and satisfaction are crucial characteristics of SDL (Merriam etal., Citation2007; Song & Hill, Citation2007). To meet these two dimensions in an online setting, more effort may be required. This is because online learners may feel disconnection and isolation from their teachers and peers (Aelterman et al., Citation2014; Buck, Citation2016, Chen et al., Citation2018; COLLINS et al., Citation2019; Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Dwivedi et al., Citation2019; Fazza & Mahgoub, Citation2021; Glenn, Citation2016). Emotion and satisfaction can be also affected by students’ anxiety in their online learning such as being stressed with assignment submissions or concerned with family issues (Buck, Citation2016; Dumford & Miller, Citation2018; Lup & Mitrea, Citation2021; Stone & O’Shea, Citation2019).

In the light of the above discussion, the characteristics of SDL in an online learning may differ from those in traditional classroom due to flexibility that students have in their learning choices over content, location, timing, and path, the absence of real interaction with their teachers and emotional constraints that affect their satisfaction to learn. To enhance learners’ SDL, designing an effective online learning environment that fosters and encourages student to take control of their learning plays a vital role. In response, we strive to obtain an in-depth understanding of students’ SDL in an online environment. The current study attempts to explore how to facilitate SDL in online environments. Particularly, the study aims to explore how SDL is understood and practised in online classes in a higher education institute (HEI) in Oman. To achieve this goal, the research question is as follows:

How is SDL interpreted, enacted, and developed by participants in online classes in an HEI in Oman?

3. Research method

In order to answer the research question, this study followed certain methodology and methods as will be explained in the following sub-sections.

3.1. The approach taken in the study

This study employed a qualitative approach to document three online English language teaching courses that the researcher was teaching and reported students’ online learning experiences. The premise behind this approach is that reality is socially constructed in the minds of participants and within situational constraints (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2017). In this approach, researchers explore a social phenomenon in a natural setting where they can understand, explain and describe it. This purpose fitted the goal of my study, which was to understand SDL in an Omani context and explore how to facilitate this type of learning in online environments.

To provide further insights on SDL in an online environment, a case study method was followed, which is commonly defined as “a well-established research strategy where the focus is on a case (which is interpreted very widely to include the study of an individual person, a group, a setting, an organization, etc.) in its own right and taking its context into account” (Robson, Citation2002, p.178). This study focused on one institution, one teacher and three group of students from three online courses. A case study was deliberately chosen in this research because its aim is to provide a detailed and comprehensive account of the context including descriptions of participants and the setting, with contextual conditions which give contextual interpretations of the phenomenon (see Yin, Citation2017).

4. Methods of data collection

The study deployed three methods of data collection: interviews, virtual observations and document analysis. The multiple methods used in this study were chosen to ensure comprehensiveness through providing a holistic and an intensive view of SDL in an online context. Additionally, the three methods complemented each other; one provided particular information that others could not provide sufficiently. Finally, the three methods also aimed to cross-check data. More discussion about the purpose of these three methods of data collection is provided below.

First, all virtual observations of students’ online participations were recorded and transcribed and students’ online discussions for each course were archived. These observations and online discussions helped in capturing the actual practices and interactions of the teacher and students during online classes. As Cohen et al. (Citation2017) declared, observations help to capture actual data from live situations, unlike interviews which can be subjected to participants’ short memories or their feeling of reluctance to comment negatively on their practices.

Data from each course also included course documents. Some instructional materials of the sample courses were also collected. These include the course outline, reading documents, assignment handouts, and emails. The purpose of collecting these documents was to gain knowledge of the contexts and explain data gained from observations and interviews. Document analysis provides an objective source of information about the case under investigation compared to others, such as interviews (Merriam, Citation2019).

Finally, all participants were interviewed towards the end of the semester. The interviews focused on the learners’ general online experience including their impressions of how their online classes went, reflections on their learning styles, time commitment and learning environments, opinions about course online activities and teaching practices, satisfaction with teacher and peer interactions, and suggestions for future online instruction and learning. The interviews were recorded after students’ permission; in addition, notes were taken to record non-audible responses. Each interview lasted from 40 minutes to 1 hour and it was transcribed word-for-word by the researcher.

All interviews were conducted via Zoom and followed the same individual semi-structured protocol. A semi-structured interview is a type of interview in which the interviewer prepares some questions in advance while the rest of questions are generated during the interview (George, Citation2008). This type of interview was intentionally selected to provide an in-depth understanding of online learners’ experience of SDL and explore any contextual influences that may impact this type of learning.

4.1. Participants of the study

To provide rich qualitative information, seven students from each course were selected for interview based on convenience sampling; i.e. the participants are selected based on their willingness to participate or easy accessibility (Dörnyei, Citation2007). There were nine males and 12 females who participated in the study (see Table below). They were from different years (1, 2 and 4) and their ages range from 18 to 22. The participants may not be representative, but this is not an issue in qualitative research that advocates that reality is constructed in the minds of individuals and so should vary from one to another.

Table 1. Information about participants’ profile

4.2. Ethical considerations

There were ethical considerations adhered at every stage of the research design of this study. All students in the three classes (not only the main participants) were asked to sign a consent form approved by the college in question that explains the purpose of the study and types of data required. The form also covers how long the data will be kept, and the students’ right to discontinue their participation in the research project at any point if they feel that the whole process causes much inconvenience or any harm to them. Added to this, to ensure the confidentiality of the students’ identities, all the recorded interviews and observations were destroyed after transcription had been completed. Furthermore, as shown in Table , the main participants of the study were identified only through labels to keep them anonymous.

Table 2. Participants’ Labelling

4.3. Data analysis

The analysis went through five main stages. First, in order to avoid confusion and conduct an in-depth analysis, the data collected from the three online classes were separated. For each course, eight weeks’ online observations, seven interviews (one interview per each participant) and four instructional materials (the course outline, reading documents, assignment handouts and emails) were gathered and transcribed. The grouped data were to be examined as an individual case of community of inquiry.

Second, based on the recommendation of Gläser and Laudel (Citation2013), the raw data of each class were initially linked to the research question and repetitive or irrelevant data were removed. For example, when answering about her overall experience with online learning C2S6 deviated from the main topic to talk about her life during corona virus,

C2S6: … and it is good for you to start business … business you like. You can succeed. We stay in my house and we have nothing to do. So, we can create things and think of useful thing. So, I design henna stickers. It is fun and interesting and I have lots of money …

Third, the relevant data were structured into categories following thematic coding (Gläser & Laudel, Citation2013) which evolved two steps. Thematic coding initially entailed searching for significant codes that provide an understanding of how the participants experienced SDL. For example, the following excerpt from C3S5’s interview was labeled as “time commitment”,

C2S7: I log in in different times. Sometime, I log in live video but sometime no

Researcher: Is this because you get disconnected or what?

C2S7: NO, no ((laughing) … I don’t have time to watch it.

Researcher: Why? Are you busy with anything else?

C2S7: No, it’s ….To be honest with you, I don’t give much time for online learning. Only when there is assignment that have marks.

Then, all the codes were grouped into different themes. For example, the above code alongside other three codes which were “lack of time”, “load of assignments” and “deadlines” were placed in “time management” theme.

Fourth, the codes and themes were reviewed many times. The researcher conducted a comparative study across all the three cases to identify the common and different perceptions and practices about SDL in an online environment.

Finally, an in-depth description of the results was written using the themes as headings to report the participants’ experiences and practices related to the phenomenon of SDL. Following the advice of Yin (Citation2017), the report was sent to the participants to verify in order to establish the credibility of the findings.

5. Results

As mentioned, the purpose of this study was to gain a concrete understanding of college students’ SDL in an online environment and identify its challenges and issues; therefore, in this section, particular attention is paid to reporting and describing students’ and teachers’ practices of SDL in online classes. The results of this study are mainly based on the experiences of students who learn online and, thus they are almost all unique to this environment. Nevertheless, some of the findings may be identical to those practices used in the face-to-face environment. However, as will be presented below, the way faculty and students dealt with these issues marks a clear distinction between what works in online courses and face-to-face.

The analysis of the students’ interviews supplemented by the three courses’ virtual observations and instructional materials revealed four issues related to students’ SDL in online classes: 1) student cognitive engagement with online learning, 2) student-centered approach, 3) time-management and 4) student emotional engagement with online learning.

5.1. Cognitive engagement

The study findings revealed that in order to develop their SDL, students need to have a clear framework that allows them to do that. Based on students’ interviews, 12 participants (Class 1: 5, Class 2: 3 and Class 3: 4) complained that their teachers were not concise with the delivery of new content. C3C1 complained that her teacher just sent the materials to students and never checked their understanding or responded to their queries.

C3C1: Some activities is difficult. I was confused and do not know how to answer. So, I wait for teacher answer.

Designing clear and simple instructions requires rigorous work itself. Two participants from Class 2 complained that they had to spend much time and use greatest amount of higher-order thinking to figure out what to do in one of their assignments because they received few instructions from their teacher. C2S2 commented,

C2S2: I will show you one assignment here on my phone. ((C2S2 showed his assignment to the researcher)). See this. Unclear. “Online learning has had a significant impact on education since 2020. Discuss the changes it has made.” So, what change? Change for us, students? Change for you, teacher? Change for what exactly? Unclear. Right? Then, when I write my essay, I have a bad mark because I talk about its benefits to students, save money. I mean students save money not use transport and rent house, like this.”

C2S4 agreed with C2S2 and confirmed that teachers should clarify all online materials in details and provide them as much guidance as possible so that they know how to perform their tasks properly.

However, the results also showed that excessive guidance and support reduced SDL and led students to be over-reliance on their teacher. When the twelve students who had issues with understanding online materials, mentioned above, were asked whether they attempted to question their teacher about these issues and have more clarification, they stated different excuses that indicate their unwillingness to direct their own learning.

Researcher: Have you tried to send her an email or raise your issue in your live-stream lectures?

C3S5: No

Researcher: Why?

C3S5: I don’t know. Maybe it is teacher job not my. ((Laughing))

Indeed, the findings revealed that SDL in an online environment flourished when teacher involvement was limited and when students were encouraged to initiate for their own learning. The section below present this aspect in details.

5.2. Student-centered Approach

Based on class observations, emails and students’ interviews, students in Classes 2 and 3 were found more committed to direct their own learning through setting goals, finding resources and seeking support. The number of students who were less determined to engage with the tasks and control their own work was higher in Class 1 (11) compared to Classes 2 (five) and 3 (four). (It should be noted that these numbers referred to all students in the three classes and not only the participants.)

The analysis connected such level of SDL to approaches to teaching followed in these classes. Based on their interviews, all participants realized that online education gears towards more SDL.

C3S7: I know this online teaching mean we need to work ourselves. We are responsible to log in, to participate, to give our opinion to submit work and ask our teacher if anything mot clear.

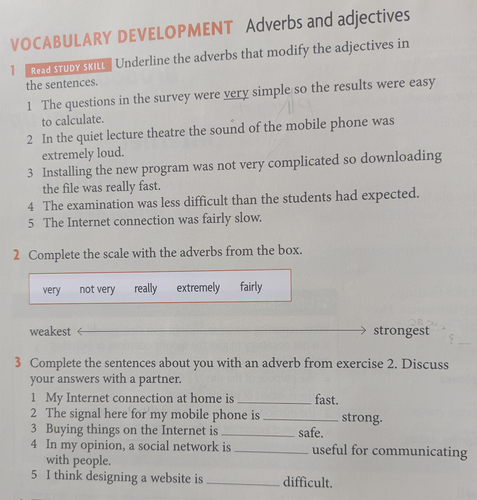

However, it seems to be that some students were not encouraged to take an active role towards their learning. In Class 1, for instance, the instructor taught with predefined content in that the students were asked to perform the textbook tasks (see Figure below) which did not engage learners in shaping and integrating their experiences into the course content. In such situations, the role of instructors to adopt an autonomous and active role in online teaching was downplayed.

On the other hand, in Classes 2 and 3, the teacher required the students to take more responsibilities in establishing their own assignment. The students were asked to follow a more individualized approach that helped them to perform better and design their timeframe neatly with very clear goals. Based on the virtual observations, emails, students’ submissions and participants’ interview, more than two-third of students in Classes 2 and 3 made an effort to take responsibility in establishing their own assignment. They were following their teacher in all processes of writing including brainstorming, outlining, drafting, reviewing and editing, and questioning her on everything; trying to understand the assignment requirements. Hence, they learnt how to take control over their own learning materials and succeeded to cope with this online learning, which offered a great extent of autonomy as compared with traditional face-to-face settings.

Taking control over own learning also evolved time management, as will be presented below.

5.3. Time-management

Based on the analysis, SDL required a high level of time management when taking an online course. It was found that 13 participants (Class1: 2, Class 2: 6, Class 3: 5) had good time management skills. Based on their interviews, these students created a list of tasks on daily basis and prioritized the tasks according to submission date, workload, and time required. Accordingly, they successfully submitted their work on time. C3S7 commented,

C3S7: We have many assignment in different courses and so we have to arrange them when to work for each one of them.

Researcher: How do you arrange that?

C3S7: First, based on when is the deadline. Then, how muck mark for each assignment. Also, how much work need for each assignment. Some assignment are simple and do not need much time.

On the other hand, the study revealed that 18 students out of 71 from the three classes had an issue with time management in that they failed to submit their work on due time. Based on these students’ emails and participants’ interviews, the students did not know how to manage their learning and schedule their study time. For example, when question how they manage their time when they study online, eight participants (Class1: 5, Class 2: 1, Class 3: 2) answered haphazardly showing that they had no plans or ideas on how to control their work. C3S3, for instance, commented,

C3S3: I attend live classes and then I do my assignment if there is assignment.

Researcher: When do you do your assignments? For example, that assignment which you submitted late last week, when did you start writing it?

C3S3: Two days

Researcher: Before submission?

C3S3: Yes

Researcher: Don’t you think that assignment requires more time?

C3S3: I don’t know. ((Laughing))

Researcher: Do you usually set more time for some assignments than others?

C3S3: No

Researcher: So, you set two days to work for any kind of assignment?

C3S3: Yes, two days or sometimes three days

The teacher set time for deadlines to help students manage their time; however, the results revealed that regardless of teacher effort to schedule students’ deadlines, some students were not committed to take responsibility to manage their work. When the eight participants, mentioned above, were questioned for how long they study and when to study, they showed a lack of commitment to dedicate time and effort to study online. The following excerpt for instance showed that C2S1 did not have the willingness to control her own pace and specify time for completing their tasks and assignments on time.

C2S1: I study before exams only ((laughing)).

Researcher: How about assignments, when do you work for them?

C2S1: Before we submit.

Researcher: Two weeks, for example? Three? Four?

C2S1: No no, one or two days

Researcher: Do you think these two days are enough?

C2S1: Yes ((laughing))

Researcher: Sure?

C2S1: Miss, too much work, we have to do lots of thing

Researcher: Like what?

C2S1: Attend class, submit assignment

Researcher: Do you think this is too much work?

C2S1: For me, yes ((laughing))

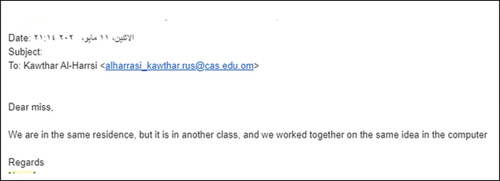

The lack of commitment was also revealed when one student from Class 2 submitted a plagiarized work, which yielded a matching percentage of 100% on the Safe Assign (a plagiarism detector tool). The plagiarized work was of another student from another class. When the student was questioned by the teacher, he claimed that he worked with that student with the same idea, but he wrote his essay himself (see Figure below). However, it should be mentioned that this student wrote a different outline and plan at the beginning of the semester. Furthermore, his first draft, which was incomplete, was totally different from his final draft. In addition, his work during the semester indicated that he had poor time commitment in that he had been regularly late for submitting his tasks. The teacher had to constantly remind him to submit his tasks and frequently extending his deadlines.

Another evidence for lack of commitment was when one participant reported that she and her colleagues failed to turn in their assignment on time because they did not open the Blackboard (a web-based server software) to check what was uploaded or sent by their teacher. This clearly indicates that the students did not like to be self-initiated and waited their teacher to send them an email.

I would like also to talk about the application we used. Most teachers insisted on using “blackboard”, however we did not receiving any notification from there. We had to open it as a window every day to see the updates … One of my teachers sent us the deadline of submitting an assignment and we had no idea about it. We only know after sending her an email and we were running out of time. I think this is everything. Hopefully next semester we will not use distance learning. (C2S7, interview)

Such an analysis can be substantiated with the emails that the teacher sent to those students who had an issue with their time management questioning their late submission. All of the students replied back with different excuses that do not indicate their willingness and dedication to manage their time. For example, one student acknowledged that he had to resort to his friends and relatives to write his assignments for him because he was overloaded with many assignments. Based on the student, he had five courses and each course had one assignment. In a normal circumstance; i.e. face-to-face learning, the rate of this load in the college is ordinary. It is obvious then that this student did not have the willingness to control over his time, and accordingly he felt a lot of stress when he tried to catch up with deadlines.

Miss 90% of the assignment sent by our teacher, I wasn’t able to do it by myself. I was asking my friends and my parents asking for help. To be honest, they write some assignment or write 90 or 80%.There are many assignment I was asking. Teachers give lots of work in online class to make sure we follow her. Too much for us. Some of the assignments were difficult because it require a lot of time to do it. It worth like 20 marks 25 marks. I have five courses and 5 assignments. (Course 3, email)

Nevertheless, lack of time commitment was also linked to student emotional engagement with online learning, which will be presented below.

5.4. Emotional engagement

The results of the study revealed that SDL was influenced by student satisfaction and motivation to take control of their learning. The findings showed that the more successful online learners were the ones who were motivated to learn in online settings. More than half of the participants (Class 1: 3, Class 2: 5 and Class 3: 6) were highly motivated to learn online. Therefore, these students were willing to take charge of their own learning process and maintained successful communication and comprehension of their online course content. C3S7, for instance, had a positive attitude towards online learning, and thus he considered online learning as a challenge to be mastered and he maintained a strong commitment to achieve the outcomes of the online courses. He was a successful learner who did things out of enjoyment and curiosity and was determined to seek out answers and also speak up when questions arise.

C3S7: I like these online classes. I enjoy them very much. I know there are some students who say “oh this is difficult” but I don’t agree with them. These student don’t want to work. They are lazy. They think that online class are difficult because they did not work hard. Some of them just log in and go to do other thing. Some of them pretend that they do not have internet and some say “I have a problem with my computer or microphone”. So, they don’t work and finally say “this online teaching is useless!”

C2S3 also expressed satisfaction with the autonomous and self-regulating work he does in online learning. He even thought that it is not the responsibility of teachers to teach students technical skills. He commented that students can easily learn how to utilize technology on their learning.

C2S3: English learning is not like so much a few years ago. You have to use technology. As I said in my essay which is bout “studying English using technology”, technology is very useful and students should learn English using modern technology. They should not wait their teacher to teach them how to use online application. Everything is easy and student now are clever in technology. It is easy to learn how to submit assignment in Blackboard or how to be live in Zoom.

On the other hand, there were seven participants (Class 1: 2, Class 2: 3, Class 3: 2) who showed less satisfaction with online learning. Three of them (C2S4, C3S5 and C3S6) expressed that online learning disconnects and isolates them from their teachers and classmates. They reported that they miss the collaborative learning environment that exists in traditional learning. When questioned for their low engagement in online discussion, in that they rarely logged in or posted comments and opinions, they justified that these discussions can never be a replica of traditional classroom discussions.

C2S4: In traditional learning, we see the teacher. We see student. We communicate in real with them. We feel interest because it is real communication.

In addition to their sense of belonging, four students (C1S1, C1S6, C2S5 and C2S6) also showed a lack of satisfaction and motivation with the flexibility of learning. These students thought that traditional teaching helps them to be more disciplined and wisely use their time throughout the semester, while with online learning, they felt lost and could not deal with the responsibilities required by their courses.

C1S6: In classroom, teacher follow step, we follow these steps. Everything is organized and teacher do everything in organized way. We don’t have to worry when to do our task or this assignment. Here, online, everything is upside down.

These students reported that they engaged less than their peers in their tasks and activities. They also felt disappointed when experiencing difficulties and had weak commitments to perform their tasks or submit their assignments.

C2S5: Of course this online classes are difficult than face-to-face because it is difficult to connect with this teaching and maybe you don’t have internet. Sometimes, I don’t find the link to submit my work. I remember, one day, I have problems to log in quiz. I spend time and tried hard. The teacher say she explain this many time and my friends all know to log in and why only me … At the end, I failed to submit online. I don’t know. So, I send the quiz by email.

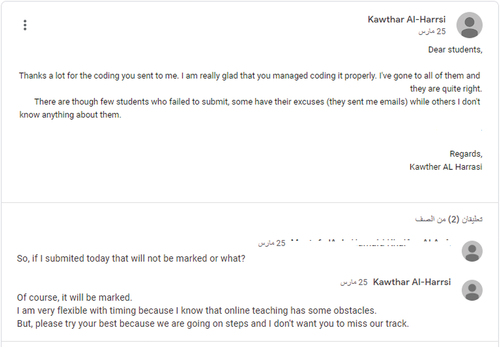

In addition to students’ interviews, the virtual classes also demonstrated a connection between students’ satisfaction with SDL in online learning and their success. There was a group of students from the three courses (Class 1: 11, Class 2: 5, Class 3: 4) who were less determined to engage with the tasks set for them and advance their skills. The students were inactive in class activities, rarely attended their virtual classes, and failed to submit their assignments on time. In a matter of fact, they rarely expressed their opinions in online discussions and shared their answers with their classmates. As a consequence, the teacher had to send individual emails to these students and post frequent online reminders and announcements. The announcements contained comments on where students were, and what and when they needed to submit. The following post (see Figure ) taken from Google Classroom (a web-based platform) showed that some students did not even bother to send their excuses to their teacher for being unable to submit their work on time. When questioned, they showed their unwillingness to engage with online learning and did not think it is an effective substitute to traditional learning. There were also four low-level students who regarded online assignments as homework when they were not marked and so they did not bother to keep up with the workload of the online course.

6. Discussion

In the light of the above-mentioned results, this study stresses out that online learners have more flexibility in their choices such as where, how, when and with what activities or content they engage with; however, this flexibility creates constraints to SDL as students tend to struggle to cope with some issues related to their online learning in terms of the level of motivation, taking initiative for learning, self-management of learning activities, organization skills, time management, maintaining interactions, and building rapport with their peers.

First, motivation can be a major influence on online learner SDL. The results of this study suggest that those students who were more enthusiastic about online learning had a strong sense of responsibility for directing and guiding their own learning and for keeping up with their online classes. Indeed, previous research has emphasized that motivation and satisfaction with learning are crucial characteristics of SDL (Merriam etal., Citation2007; Song & Hill, Citation2007). However, the results of this study suggest that more effort is needed to raise students’ motivation and satisfaction with learning in an online setting. Based on the results, some students were less engaged in discussions in that they rarely logged in or posted comments and opinions because they felt disconnected and isolated from their teachers and peers by a computer screen, a finding that goes in line with previous research (Aelterman et al., Citation2014; Buck, Citation2016, Chen et al., Citation2018; COLLINS et al., Citation2019; Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Dwivedi et al., Citation2019; Fazza & Mahgoub, Citation2021; Glenn, Citation2016). These students emphasized that online learning can never be a replica of a traditional classroom. They longed for real traditional teaching as they appreciate being able to see their teachers and interact with them in real time and place. Hence, this suggests a need to reconsider approaching motivation in online learning.

Another essential area that may impact learner SDL is the flexibility of learning online. Based on the results of the study, some students preferred traditional teaching because it made them more disciplined and wisely used their time throughout the semester. On the other hand, they were dissatisfied with the flexibility and freedom to study materials in online classes because they could not deal with the responsibilities required by the online courses. Accordingly, these students failed to take initiative for learning and were unable to manage their time and learning activities because they felt stressed meeting the deadlines of assignments, which supports previous research (Buck, Citation2016; Dumford & Miller, Citation2018; Lup & Mitrea, Citation2021; Stone & O’Shea, Citation2019). Not to mention that those students who were already weak scholars or those who regarded these online assignments are somehow equivalent to doing homework, were hopeless of trying to keep up with the workload of the online course.

Learner ability to cope with the flexibility in online learning, and SDL in specific, can be majorly connected with their time management. The flexibility in learning requires high levels of time management. The results showed that some students failed to manage their learning and deal with the responsibilities because they had poor time management in that they did not understand how to manage their time wisely throughout the semester to make enough room for the online course tasks and assignments. In agreement with previous research, lack of time management leads to low academic achievement (Deniz, Citation2006; Howell & Watson, Citation2007; Klingsieck et al., Citation2012; Nawrot & Doucet, Citation2014; van Eerde, Citation2003; Wolters, Citation2003; Zheng et al., Citation2015) and procrastination (Rabin et al., Citation2011; Richardson et al., Citation2012).The importance of time management for SDL was further verified by students who succeeded to take control of their own learning because they had high time management skills in that they knew how to schedule their study time and catch up with deadlines. Indeed, the study of Kizilcec et al. (Citation2016) provided further evidence on the ability of those learners who have high levels of time management to cope with their SDL.

Previous research has shown that teachers can set deadlines and track their students’ use of time to help them manage their time appropriately and avoid procrastinating (Andrade & Bunker, Citation2009; Dembo & Seli, 2013; Wang et al., Citation2013). However, the results of this study suggests that teacher effort was not much effective as the issue of time management was mainly due to students’ sense of responsibility and commitment. Although the teacher set a schedule of deadlines for work submissions, still some students failed to hand in their work on time. This was due to poor time commitment. When questioned for how long they study and when to study, students showed a lack of commitment to dedicate time and effort to study online. They did not show their willingness to control their own pace and specify time for completing their tasks and assignments on time. It should be mentioned that more discipline and commitment from the part of learners is required in online learning which entails devoting more time and effort than usual (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Glenn, Citation2016; Song & Hill, Citation2007).

In fact, the study findings suggest that the core of online learning should be centered on learners to empower their SDL abilities. Based on the results, in Classes 2 and 3, the teacher required the students to take more responsibilities in establishing their own assignment. The students were asked to follow a more individualized approach that helped them to perform better and design their timeframe neatly with very clear goals. Therefore, the students in these two classes were active and engaged in their own activities and were familiar with how to take control over their own learning materials and cope with online learning. On the other hand, since SDL was downplayed in Class1 because their teacher taught with predefined content, the students were left with few opportunities to engage in shaping and integrating their experiences into the course content. Therefore, in agreement with previous research (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2014; Zhu et al., Citation2020), the findings of the current study strongly suggest that the student-centered approach in which the responsibility for the learning path is placed in the hands of students helps to develop SDL as it leads learners to be more motivated, self-disciplined, and well-organized, as well as gain high degrees of time management skills.

Nevertheless, while the student-centered approach may work effectively in an online environment, being distant from their teachers, online learners may need more clarification on their online materials (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Denis, Citation2003; Dixson, Citation2010; Glenn, Citation2016; Melissa, Citation2015; Sumuer, Citation2018). Based on C2S2, he had to spend much time and use greatest amount of higher-order thinking to figure out how to perform one of his online tasks. For this reason, the teacher goal should be to critically create a clear framework that guides students in their online SDL. It is necessary to constantly assure learners’ understanding of the online content to lead to successful learning (good academic performance) in the online environments. As previous research has stressed out, teacher presence is the foundation of student cognitive engagement with online learning (Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Ingulfsen et al., Citation2018; Joksimović et al., Citation2015; Molinillo et al., Citation2018; Rotgans & Schmidt, Citation2011).

However, the results of the study also suggest that students may have higher expectations from teachers to perform everything for them such as providing instant feedback on their online assignments. As revealed in the results, some students failed to turn in their assignment on time because they did not open the Blackboard (a web-based server software) to check what was uploaded or sent by their teacher. These students did not like to be self-initiated and waited their teacher to send them an email. Hence, this goes against the student-centred approach and SDL in general. Previous research provided further evidence on this (e.g. Danver & Danver, Citation2016; Kebritchi et al., Citation2017; Xie et al., Citation2019). This then suggests that for SDL to be flourished effectively, teachers need to be cautious on the amount of guidance and effort that should be provided to learners.

7. Implications of the study

The goal of this study was to contribute to the understanding of college students’ SDL in an online environment and accordingly provide some suggestions to address the issues related SDL. The discussion section shows that students tend to struggle to cope with the sequence and the pace of learning, and with the amount of content. Based on these constraints, the results suggest that individuals need to be empowered with competencies related to SDL in online learning, including training online learners to exercise control over their studying in terms of taking initiative for learning, organization skills, self-management of learning activities, time management, maintaining interactions, and building rapport with their peers. To develop these competencies, there is a need to design an effective online learning environment through reinforcing students’ satisfaction and motivation in online classes, their time management skill, a student-centered approach and teacher presence.

First, initially to enable students be self-directed, teachers need to provide special motivation that extends across the traditional classroom setting into online learning. They need to devote more effort to help students maintain interactions and build rapport with their peers to enhance their sense of belonging and motivate them to learn. Perhaps, they can establish a collaborative learning environment through group works or through welcoming students and providing encouragement.

To develop their SDL skills, teachers also need to reinforce a student-centered approach in their teaching in which the responsibility for the learning path is placed in the hands of students. Perhaps, more self-directed tasks need to be assigned for students. It is preferable that these tasks are assigned for assessment so that students consider them seriously. Teachers can help students with low level of commitment to follow a more individualized approach to online learning compared to traditional learning by following their own learning strategies and by making decisions to meet their needs in accordance to learning goals and at their own pace. They also need to help them develop their time management skills in that they need to understand how to manage their time well to make enough room for the online course tasks and assignments.

In addition to a student-centered approach, there is also a need to communicate the course policies and rules clearly to students at the beginning of the online course to lower their expectations and to establish an independent mode of learning that directs students to take control of their own learning and thus reinforce their SDL. As the results of this study suggests, online learners may have higher expectation from their teachers such as providing instant feedback on their assignments.

Teacher role though is needed in other aspects of SDL. The results of the study showed that online students need more scaffolding on understanding materials compared to students in traditional learning environments. As shown in the results section, some participants complained that their teachers were not concise with their delivery of new content in that they just sent them the materials and never checked their understanding or responded to their queries. Hence, teachers need to ensure students’ understanding of the content, assignments or tasks. Without sufficient support from their teachers, students may be less cognitively engaged with online learning.

In conclusion, since online learning is very different from traditional learning, throughout this process, researchers, online course designers, and teachers need to reexamine student readiness for online learning and re-develop a more comprehensive measure of SDL considering the key issues that would affect students’ readiness for online learning. By undertaking this approach, researchers can better enhance understanding of college students’ SDL in an online environment and encourage learners to take control of their learning. Furthermore, this approach helps to design better online courses and enable teachers to guide students towards more fruitful and successful online learning experiences.

8. Limitations of the study and future research

There are three main limitations of this study that need to be acknowledged and addressed in future research. First, the interviews which were conducted towards the end of the semester were influenced by the shortcomings of the participants’ memories in some cases. Therefore, participants may need to reflect on their own practices immediately after each observation.

Moreover, this study reveals the need for exploring students’ final exam as one of the students’ success indicators. The final course grades can help obtain an in-depth understanding of the relationship between SDL abilities and academic performance.

Finally, the validity of the results of the study may be affected by the researcher being the teacher in the three courses. The participants could have acted differently and felt reluctant to reveal any negative issue or comment on their teachers’ deficiencies. Therefore, for future research, it is more valid to involve different teachers to participate in the study.

9. Conclusion

The purpose of the current study was to understand college students’ SDL in an online environment and also to identify its challenges and issues. Based on the results, four issues were related to students’ SDL in online classes: 1) student cognitive engagement with online learning, 2) student-centered approach, 3) time-management and 4) student emotional engagement with online learning.

First, the results found teacher guidance and support significant for student cognitive engagement with online materials. Students found difficulty understanding the new online content when there was no clear framework and the teacher never checked their understanding or responded to their queries. The students also found it difficult to deal with assignments that had few and complicated instructions. Such assignments evolved much time and effort and use greatest amount of higher-order thinking to figure out how to complete them effectively. On the other hand, the results revealed that students perform their tasks properly when they received detailed guidance from their teachers.

Nevertheless, it was also shown that teachers’ excessive support sometimes led students to be dependent on their teachers and unwilling to direct their own learning. The study showed that SDL in an online environment flourished when teacher involvement was limited and when students were encouraged to initiate for their own learning. Based on the findings, the class that was not encouraged to take an active role towards their learning and less engaged in shaping and integrating their experiences into the course content was less committed to direct their own learning through setting goals, finding resources and seeking support. On the other hand, the class that was required to take more responsibilities in establishing their own assignment and follow a more individualized approach that helped them to perform better and design their timeframe learnt how to take control over their own learning materials and succeeded to cope with this online learning.

Taking control over own learning also evolved time management. The results showed that SDL required a high level of time management when learning online. Those learners who had good time management skills; e.g. they prioritized the tasks according to submission date, workload, and time required, successfully submitted their work on time. On the other hand, the learners who had no plans or ideas on how to manage their work failed to submit their work on due time. The teacher may set time for deadlines to help students manage their submissions; however, the findings confirmed that learners’ time management was highly dependent on the learners’ willingness; that is, when learners were not committed to take responsibility to manage their work and dedicate time and effort to study online, they tended to submit a plagiarized work or not turn in their assignments on time.

Nevertheless, lack of time commitment was also linked to student emotional engagement with online learning. The results of the study revealed that SDL was influenced by student satisfaction and motivation to take control of their learning. The findings showed that the more successful online learners who maintained a strong commitment to achieve the outcomes were the ones who had a positive attitude towards online learning and considered online learning as a challenge to be mastered. On the other hand, those who showed less satisfaction with online learning and expressed that online learning disconnected and isolated them from their teachers and classmates were less determined to engage with the tasks set for them and advance their skills and felt disappointed when experiencing difficulties.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kothar Talib Sulaiman AL Harrasi

Kothar Talib Sulaiman AL Harrasi is currently an assistant professor at Rustaq College of Education, University of Technology and Applied Sciences in Oman. She has been teaching ELT students for almost 12 years. She is particularly interested in presenting and publishing papers related to TESOL and Applied Linguistics.

References

- Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., van den Berghe, L., de Meyer, J., & Haerens, L. (2014). Fostering a need-supportive teaching style: Intervention effects on physical education teachers’ beliefs and teaching behaviors. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 36(6), 595–20. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2013-0229

- Alario-Hoyos, C., Estévez-Ayres, I., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Kloos, C. D., & Fernández-Panadero, C. (2017). Understanding learners’ motivation and learning strategies in MOOCs. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 18(3), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i3.2996

- Andrade, M. S., & Bunker, E. L. (2009). A model for self-regulated distance language learning. Distance Education, 30(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910902845956

- Bonk, C. J., Lee, M. M., Reeves, T. C., & Reynolds, T. H. Eds. (2015). MOOCs and open education around the world. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315751108

- Bouhnik, D., & Marcus, T. (2006). Interaction in distance-learning courses. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(3), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20277

- Buck, S. (2016). In their own voices: Study habits of distance education students. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 10(3–4), 137–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290x.2016.1206781

- Carr, S. (2000). As distance education comes of age, the challenge is keeping the students. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 46(23), A39–A41. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ601725

- Chen, J., Wang, M., Kirschner, P. A., & Tsai, C. C. (2018). The role of collaboration, computer use, learning environments, and supporting strategies in CSCL: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 88(6), 799–843. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318791584

- Chou, P.-N. (2012). The relationship between Engineering students self-directed learning abilities and online learning Performances: A Pilot study. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER), 5(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v5i1.6784

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in Education (8th ed.). Routledge.

- COLLINS, K., GROFF, S., MATHENA, C., & KUPCZYNSKI, L. (2019). Asynchronous video and the Development of instructor Social presence and student engagement. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 20(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.522378

- Danver, S. Eds. (2016). The SAGE encyclopedia of online education. SAGE Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483318332

- Deimann, M., & Bastiaens, T. (2010). The role of volition in distance education: An exploration of its capacities. The International Review of Research in Open & Distance Learning, 11(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i1.778

- Denis, B. (2003). A conceptual framework to design and support self-directed learning in a blended learning programme. A case study: The DES-TEF. Journal of Educational Media, 28(2–3), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358165032000165626

- Deniz, M. E. (2006). The relationship among coping with stress, life satisfaction, decision-making styles, and decision self-esteem: An investigation with Turkish university students. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 34(9), 1161–1170. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2006.34.9.1161

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2017). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (Fifth ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Dixson, M. (2010). Creating effective student engagement in online courses: What do students find engaging? Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(2), 1–13 http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ890707.pdf.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics : quantitative,qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford University Press eBooks. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA82715592

- Dumford, A. D., & Miller, A. L. (2018). Online learning in higher education: Exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 30(3), 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-018-9179-z

- Durnali, M. (2020). The effect of self-directed learning on the relationship between self-Leadership and online learning among university students in Turkey. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 8(1), 129–165. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-8(1)-2020pp129-165

- Dutton, J., & Perry, J. (2002). How do online students different from lecture students? Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(4), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v6i1.1869

- Dwivedi, A., Dwivedi, P., Bobek, S., & Sternad Zabukovšek, S. (2019). Factors affecting students’ engagement with online content in blended learning. Kybernetes, 48(7), 1500–1515. https://doi.org/10.1108/k-10-2018-0559

- Fazza, H., & Mahgoub, M. (2021). Student engagement in online and blended learning in a higher education institution in the Middle East: Challenges and solutions. In Studies in technology enhanced learning. Published. https://doi.org/10.21428/8c225f6e.5bcbd385

- Geng, S., Law, K. M. Y., & Niu, B. (2019). Investigating self-directed learning and technology readiness in blending learning environment. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0147-0

- George, M. (2008). Understanding Social research: Perspectives on methodology and Practice. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Gläser, J., & Laudel, G. (2013). Life with and without coding: Two methods for early-stage data analysis in qualitative research aiming at causal explanations. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(2), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-14.2.1886

- Glenn, C. (2016). Adding the human touch to asynchronous online learning. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 19(4), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025116634104

- Howell, A. J., & Watson, D. C. (2007). Procrastination: Associations with achievement goal orientation and learning strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(1), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.017

- Hromalik, C. D., & Koszalka, T. A. (2018). Self-regulation of the use of digital resources in an online language learning course improves learning outcomes. Distance Education, 39(4), 528–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1520044

- Ingulfsen, L., Furberg, A., & Strømme, T. A. (2018). Students’ engagement with real-time graphs in CSCL settings: Scrutinizing the role of teacher support. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 13(4), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-018-9290-1

- Joksimović, S., Gašević, D., Kovanović, V., Riecke, B. E., & Hatala, M. (2015). Social presence in online discussions as a process predictor of academic performance. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(6), 638–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12107

- Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher Education. A Literature Review Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(1), 4–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713

- Kim, R., Olfman, L., Ryan, T., & Eryilmaz, E. (2014). Leveraging a personalized system to improve self-directed learning in online educational environments. Computers & Education, 70(1), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.08.006

- Kizilcec, R. F., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., & Maldonado, J. J. (2016). Recommending self-regulated learning strategies does not improve performance in a MOOC. Proceedings of the third (2016) ACM conference on learning (pp. 101–104).

- Klingsieck, K. B., Fries, S., Horz, C., & Hofer, M. (2012). Procrastination in a distance university setting. Distance Education, 33(3), 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.723165

- Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Association Press.

- Lup, O., & Mitrea, E. C. (2021). ONLINE LEARNING DURING the PANDEMIC: ASSESSING DISPARITIES in STUDENT ENGAGEMENT in HIGHER EDUCATION. Journal of Pedagogy - Revista de Pedagogie, LXIX(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.26755/revped/2021.1/31

- Melissa, K. (2015). Lost in translation: Adapting a face-to-face course into an online learning experience. Health Promotion Practice, 16(5), 625–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839915588295

- Merriam, S. B. (2001). Andragogy and Self-Directed Learning: Pillars of Adult Learning Theory. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 2001(89), 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.3

- Molinillo, S., Aguilar-Illescas, R., Anaya-Sánchez, R., & Vallespín-Arán, M. (2018). Exploring the impacts of interactions, social presence and emotional engagement on active collaborative learning in a social web-based environment. Computers & Education, 123, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.04.012

- Nawrot, I., & Doucet, A. (2014). Building engagement for MOOC students: Introducing support for time management on online learning platforms. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web (pp. 1077–1082). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2567948.2580054

- Rabin, L. A., Fogel, J., & Nutter-Upham, K. E. (2011). Academic procrastination in college students: The role of self-reported executive functioning. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 33(3), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2010.518597

- Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838

- Robson, C. (2002). Real world research. Blackwell.

- Rohs, M., & Ganz, M. (2015). Moocs and the claim of education for all: A disillusion by empirical data. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 16(6), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i6.2033

- Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2011). Cognitive engagement in the problem-based learning classroom. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 16(4), 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-011-9272-9

- Song, L., & Hill, J. (2007). A conceptual model for understanding self-directed learning in online environments. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 6(1), 27–42. http://acmd615.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/1329033/Song.pdf

- Stone, C., & O’Shea, S. (2019). Older, online and first: Recommendations for retention and success. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3913

- Sumuer, E. (2018). Factors related to college students’ self-directed learning with technology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(4). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3142

- van Eerde, W. (2003). A meta-analytically derived nomological network of procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(6), 1401–1418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00358-6

- Wolters, C. A. (2003). Understanding procrastination from a self-regulated learning perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.179

- Xie, K., Heddy, B. C., & Greene, B. A. (2019). Affordances of using mobile technology to support experience-sampling method in examining college students’ engagement. Computers & Education, 128, 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.020

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Zheng, S., Rosson, M. B., Shih, P. C., & Carroll, J. M. (2015). Understanding student motivation, behaviors and perceptions in MOOCs. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 1882–1895). Association for Computing Machinery. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2675217

- Zhu, M. (2021). Enhancing MOOC learners’ skills for self-directed learning. Distance Education, 42(3), 441–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1956302

- Zhu, M., & Bonk, C. J. (2019a). Designing MOOCs to facilitate participant self-directed learning: An analysis of instructor perspectives and practices. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 16(2), 39–60. https://bit.ly/3yBPHI8

- Zhu, M., & Bonk, C. J. (2019b). Designing MOOCs to facilitate participant self-monitoring for self-directed learning. Online Learning, 23(4), 106–134. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i4.2037

- Zhu, M., & Bonk, C. J. (2020). Technology tools and instructional strategies for designing and delivering MOOCs to facilitate self-monitoring of learners. Journal of Learning for Development, 7(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v7i1.380

- Zhu, M., Bonk, C. J., & Doo, M. Y. (2020). Self-directed learning in MOOCs: Exploring the relationships among motivation, self-monitoring, and self-management. Educational Technology Research & Development, 68(5), 2073–2093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09747-8