Abstract

This article presents an in-depth case analysis of Norwegian teacher training, exploring the intricate dynamics between global blueprints, national problem constructions and local realities. As Norwegian educational policy has aligned itself with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s recommendations, the study uncovers a loose coupling between educational policy, university and university college teacher training and school teaching practices. Starting from a neo-institutional perspective, our research utilised white papers and qualitative interviews with 65 stakeholders involved in teacher training. The findings reveal a complex relationship between policy and practice, with a tendency to overemphasise problems and understate the strengths of Norwegian teacher training. A document analysis and three empirical examples illustrate how this misalignment has contributed to misunderstandings regarding teachers’ competences and challenges in the field. The study also reflects on the global influences that shape domestic policy and the implications of focusing on international educational rankings. By shedding light on these nuanced connections, the article offers critical insights that recognises both the global trends and local specificities of the Norwegian educational system.

1. Introduction

The landscape of educational policymaking in Norway was once dominated by the voices of teacher associations, school principals and people associated with educational research (Helsvig, Citation2005). However, this power dynamic has shifted over time, as a diverse array of stakeholders with vested interests in the educational sector now influence policy decisions (Government, Citation2016c). Even in small nations like Norway, policy ideas are being imported from international organisations like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, short OECD (Smeplass & Leiulfsrud, Citation2022).

The Norwegian landscape of teacher training has undergone a series of rapid and profound reforms, reflecting the nation’s proactive response to the evolving currents of society (Cochran-Smith et al., Citation2020). These reforms have been set against the backdrop of globalisation and the adoption of New Public Management (NPM) during the 1990s. This transition propelled teacher training into an era of heightened expectations for productivity and quality, overseen by the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (NOKUT). As a result, the educational landscape experienced shifts from the overarching teacher reform in 1999 to the specific elementary school teacher reform in 2010, culminating in the comprehensive master’s reform in 2017 (Advisory Panel for Teacher Education, Citation2020). The pivotal transformation in teacher training policy that occurred in 2017 extended the training period from a four-year programme to a five-year master’s education, exemplifying a strategic initiative to align initial teacher training with international benchmarks and emphasise the significance of research and specialisation within education (Smeplass & Leiulfsrud, Citation2022). This transformational step was part of a broader pattern of structural changes within higher education and financing approaches based on measurable achievements.

However, when policymakers reform teacher training using universal solutions, new tensions in the education system are created as recommendations are driven by an intensified foci on results, effective teaching and learning output. In several OECD countries, these shifts in foci have been introduced through the “backdoor” following delegitimising international comparative assessments of school performance. In Norway, the country’s scores in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) were consistently below the OECD average from the initial assessment in 2000 through the period under discussion, a trend that began to challenge the prevailing idea of an educational system of exceptional quality and consequently led to major public debate at the beginning of the 2000s (Bergem, Citation2018; Helsvig, Citation2022; Meyer & Benavot, Citation2013; Pereyra et al., Citation2011). Soon after came the rise of a new policy regime and in consequence the replacement of an educational system informed by the expertise of the teaching profession through an increasingly bureaucratic and technocratic system.

Teacher training research has been a contested area since it was introduced in the middle of the 19th century (Mazandarani, Citation2022). The assumption that teacher quality is crucial to a nation’s educational excellence and that the preparation of teachers plays a pivotal role in ensuring quality (Cochran-Smith et al., Citation2020), underpins the ongoing debates in Norway. Numerous policy reforms and discourses indirectly revisit and revise the formal qualification competences of teachers (Smith, Citation2021). Still there are different understandings of how research should be utilised to improve the quality of Norwegian teacher training (Caspersen & Smeby, Citation2023). Many participants in the public debate hold the view that Norwegian teacher training is inadequate as teacher training programmes have always struggled to be acknowledged (Skagen & Elstad, Citation2023). This paper aims to illuminate the consequences of what is commonly perceived as problems in the structure of teacher training in Norway. By exploring the arguments used to critique teacher training and validate recent reforms against the backdrop of evolving policy changes, we seek to provide insights into the complexities of this educational landscape.

2. Theoretical approach

The study is informed by a neo-institutional approach. Therefore, all organisations involved in teacher training are believed to be subject to processes of adaption to their institutional surroundings, leading to the following consequences:

(a) they incorporate elements which are legitimated externally, rather than in terms of efficiency; (b) they employ external ceremonial assessment criteria to define the value of structural elements; and (c) dependence on externally fixed institutions reduces turbulence and maintains stability. As a result, it is argued here, institutional isomorphism promotes the success and survival of organizations. (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977: 348–349)

In education policy, assessments, in particular, have the power of (de-)legitimising organisations because within the education system there is no natural “currency” (e.g., money) that could be used. Delegitimisation through assessments occurs, in particular, when the educational organisation’s formal structures do not align with the current state of the art. Then, “problems” are created and orchestrated (Eagleton, Citation1991; Foucault, Citation1995; Lukes, Citation2006; Therborn, Citation1999) and can be used to enforce new policy agendas. To maintain conformity, organisations may be tempted to incorporate these agendas but at the same time buffer their everyday activities by implementing formal structures and becoming a loosely coupled organisation (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977: 341).

To address the social construction of problems, we use the concept of “problematisations” of Carol Bacchi (Citation2012a; Citation2016) translated into an analytic strategy and approach: “What is the problem represented to be?” (Bacchi, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Citation2016). In line with Bacchi’s (Citation2012a) notion of “problematisation”, it is of interest to reveal what constitutes a “problem”, including presuppositions and assumptions that underlie the idea of that specific problem. Is the “problem” a structural matter or the result of unwillingness to comply with new legislation? In contrast to a more conventional approach on discourses or agenda setting, Bacchi (Citation2016) insists that we must bring in items that are “successful” and what is referred to as “possible or desirable or impossible and undesirable” (Bacchi, Citation2016: 1). In line with Richard Svedberg’s approach of theorising, our theoretical strategy is to turn to the “context of discovery” (Swedberg, Citation2012, Citation2014, Citation2020; Swedberg & Swedberg, Citation2014). By focusing on the criticism raised in policy documents, we used Bacchi and Eveline’s (Citation2010) six questions: (1) What is the “problem”?; (2) What presuppositions and assumptions underlie the idea of a problem?; (3) How has this representation come about?; (4) What remains unproblematic?; (5) What are the effects produced?; (6) How can the representation of the problem be questioned?

The neo-institutional approach, used in this study, offers a valuable lens through which to understand the intricate interactions between formal structures, everyday practices and external influences within educational organisations. By combining it with Bacchi’s approach, we delve deeper into the underlying presuppositions of identified problems, revealing a layered understanding of the challenges that go beyond obvious descriptions.

3. Data and methods

The study of Norwegian teacher training is founded on an extended case study approach (Burawoy, Citation2009), employing a combination of document analysis, focus groups, interviews and questionnaires within a larger investigation of educational policy and teacher training organisations (for details see Smeplass, Citation2018). The qualitative study was conducted during 2015 and 2016, aligning with the period leading up to the substantial teacher training reform implemented in 2017. The chosen documents for the document analysis were not only politically significant during this period but were also the most frequently cited documents within the contemporary public discourse. This approach allows us to capture the political and bureaucratic arguments used to enhance the quality of education through teacher training—a tool at the intersection of policy and practice.

Sixty-five interviews conducted over the two-year span represented a diverse range of stakeholders in teacher training, including students, novice teachers, supervisors, counsellors, government officials and teachers from other sectors (see Table ). This varied group allowed us to explore different perspectives and understandings surrounding teacher training, offering insights not apparent in the public debate. For each group, we used a distinct interview guide with questions adapted to the specific situation and with different foci (for details see Smeplass, Citation2018).

Table 1. Types of data analysed

The selection of documents was strategically chosen to span 12 years from 2002 to 2014, culminating in the teacher training reform of 2017. This timeframe aligned with the crucial period of policy development leading up to the transformative reform. Our analysis aimed to uncover how these policy documents addressed and targeted issues related to teachers and their training. The combination of qualitative methods—interviews and document analysis—allowed us to gain a comprehensive understanding of the various dimensions and discourses surrounding teacher training policy in Norway. By examining both the voices of key stakeholders and the official policy documents, we aimed to provide an insightful exploration of the evolving landscape of teacher training and its policy implications. In the thematic document analysis, we consider how policy measures were set to target “problems” and we investigate how “problems” related to teachers and their training were defined.

Our interviewees were recruited from three different public teacher training organisations in Norway, universities or university colleges and represent different study programmes (teacher training for primary and upper-secondary schools with different subject specialisations). Students were at the end of their studies and were asked in focus groups to discuss the social responsibility for teachers in schools and how prepared they felt for a future career in teaching. Teacher trainers and counsellors in the study had many years of experience and were confronted with some of the students’ perspectives. The other groups of interviewees were recruited based on strategic samples of central actors with other relationships to teacher training. Every group mentioned in Table was asked to reflect upon their own challenges related to their work and situation and upon definitions of what constitutes a “good teacher” and “good teacher training”. Their connection to teacher training was important to investigate alternative and contradicting views on teacher training and educational policy.

The final cases presented in the analysis are the result of several rounds of “casing” where we discovered alternative ways of understanding phenomena that are represented in the data material (Burawoy, Citation2009; Ragin, Citation1989; Ragin & Becker, Citation1992). This approach provides us with an interesting departure for discovering new perspectives and understandings. Combined with a theoretical notion of problematisations (see Bacchi Citation2012a, Citation2012b), this methodology has provided access to the narratives of actors who are not represented in the public debate on teacher training.

4. Changing institutional landscape for teacher training

Several scholars describe a new global system of educational governance (Lawn & Lingard, Citation2002; Lindblad & Popkewitz, Citation2006; Mundy, Citation2007; Parreira Do Amaral, Citation2011; Parreira Do Amaral et al., Citation2019; Popkewitz, Citation1987; Sjøberg, Citation2018). This recent policy turn in education influences the way in particular Western nations organise their educational systems (Meyer & Benavot, Citation2013; Meyer & Rowan, Citation2012). In recent decades, there has been a widespread adoption of data-driven policy tools aiming to modernise education governance and enhance global competitiveness. These tools, such as large-scale (inter-)national assessments, have been widely disseminated and are now employed in countries with diverse administrative traditions and levels of economic development (Verger et al., Citation2019). External pressure comes from several government branches that are designed to evaluate the quality of education. As part of the international policy reform efforts, there has been a pervasive conviction that teacher training can play a transformative role in shifting traditional modes of schooling by producing a new generation of skilled teachers who can elevate the knowledge standards of students and enhance the economic prowess of nations (Trippestad et al., Citation2017).

For teacher training in Norway, the most significant changes in the institutional environment have been the creation of the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (NOKUT) in 2003 (NOKUT, Citation2016, Citation2017) and the separation between the Ministry of Education and Research and its executive agency, the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (UDIR) in 2004. NOKUT was assembled in the aftermath of the Bologna Process, with the goal of ensuring comparability in the standards and quality of higher education qualifications in the European Higher Education Area. UDIR was established to formally depoliticise the educational sector through a separation of evaluation that was executed by the UDIR and governance through the Ministry of Education (Helsvig, Citation2014). The UDIR has the overall responsibility for supervising early childcare, education and the governance of education. Furthermore, it is responsible for national educational statistics. Based on these statistics, the directorate initiates, develops and monitors the development in the sector. The objective is to ensure high-quality education on all levels through tighter monitoring of the sector’s achievements.

An extensive school reform, the Knowledge Promotion Reform, was introduced in all Norwegian primary and secondary schools from 2006 onwards (Bakken & Elstad, Citation2012). The overall goal was to increase the level of knowledge and basic skills. In addition to introducing the PISA, the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), the Norwegian government has developed national tests in reading, mathematics and English. Test results are currently publicly available. Furthermore, they are repeatedly referred to in the national media (Lepperød, Citation2016). These measurement tools create a new climate for the school system, which is becoming increasingly rigged for the neoliberal idea of accountability (Camphuijsen et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, the institutional environment and organisational basis of Norwegian teacher training have changed dramatically as reforms, new agencies for evaluation and control and other policy measures have altered the premises (Smeplass & Leiulfsrud, Citation2022). This change was associated with a critical view of public education and a political narrative where both teachers and their training were deemed insufficient in terms of ensuring necessary skills and evidence-based teaching (Gallagher & Bailey, Citation2000; Murray, Citation2000). Norwegian education policy is heavily influenced by international blueprints and reform agendas. Questions regarding the quality of teachers and teacher training have been highlighted in the American context since the 1990s (Cochran-Smith, Citation2021; Cochran-Smith & Zeichner, Citation2009). One of the ideas that has gained ground in Norway, without any serious debate, is that reforms of teacher training with tightly integrated programmes will produce teachers who are more effective and more likely to enter and stay in teaching (Darling-Hammond, Citation2000).

The official narrative is that the educational system will be depoliticised through an ever-increasing rationalisation of the organisation, although the inclusion of new interests creates a more fragmented policy landscape. At the same time, teachers’ organisations, such as the Union of Education Norway (Citation2014), have less influence on the overall design of educational policy. As a reaction to new measures that are intended to control teachers’ time and work, a national teacher strike took place in 2014. Following the strike, the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) signalled that it wished to transfer decision-making powers to the employers’ organisations. Consequently, many teachers felt a lack of trust in the profession—demonstrated by attempts to micromanage their day-to-day work (Union of Education Norway, Citation2014). The conflict between the teachers’ union and the government illustrates an ongoing conflict over how to define educational policy and a shift of power from the profession towards the government on educational issues.

One of the most significant recent changes in Norwegian teacher training is the change of the national framework plan for teachers—from the general teacher reform in 1999 (ALU 1999), which encompassed the elementary school teacher reform in 2010 (GLU 2010), to the master reform in 2017 (MGLU 2017). Still, the long-term effect of these reforms is yet to be investigated. In summary, these changes represent a move towards a more academic teacher training, which is believed to strengthen teachers’ knowledge by focusing on their formal subject competence. The generalist teacher (“almennlæreren”) was, for several years, the established norm, and students gained introductory knowledge on a broad range of subjects. A broad competence with less specialisation was regarded as necessary for teaching children at all levels of primary and secondary schools. Since 2010, teacher students have received a more subject-specific education, specialising in two main subjects, with didactics focusing on either the 1st to the 7th grade or the 5th to the 10th grade. These reforms were followed by a national demand for higher enrolment quotas in teacher training as official statistics predicted a future teacher shortage (Roksvaag & Texmon, Citation2012; Gunnes & Knudsen, Citation2016). However, there has been a relatively high dropout rate from teacher training, ranging from 27% to almost 40% in some cases (Utdanningsforbundet, Citation2017). Dropout rates from teacher education has been given political attention, as research indicates that more than 30% of trained teachers work in other sectors (Government, Citation2016a).

Based on the established statistical models (LÆRERMOD) and related publications, national admission to the education profession increased from 3,000 teachers per year in 2008 to 4,000 teachers in 2016 (Government, Citation2016b). This has resulted in dramatic challenges for some teacher training organisations that doubled their student intake and consequently desperately needed to increase the number of academics. Simultaneously, new requirements for teacher trainers were implemented (Government, Citation2014), demanding a higher percentage of academics with PhDs. In 2014, the government also set new formal requirements for applicants for teacher training grades in two subjects, Norwegian and mathematics. Although these changes were substantial, the different organisations offering teacher training had no real way to oppose the measures because evaluations of the ongoing reforms confirmed many of the political assumptions (Rogne et al., Citation2012; 2014).

These policy changes were motivated by ideas that resonate with a global system of educational governance (Lawn & Lingard, Citation2002; Lindblad & Popkewitz, Citation2006; Mundy, Citation2007; Sjøberg Citation2015) and recent trends in how the educational systems tend to be organised (Meyer & Benavot, Citation2013; Meyer & Rowan, Citation2012). In the next section, the official arguments used to criticise the educational system and teacher training are introduced.

5. Defining problems in policy and practice

In our document analysis, we found eight problematisation categories that represent either a diagnosis regarding the school system or teacher training (see Table ). Regarding the school system, educational policy has increasingly focused on results. Derived from the Norwegian PISA test results, the official narrative was that Norwegian schools are characterised by (I) inadequate goal attainment (NOU, Citation2002: 18; Report to the Parliament No. 11, Citation2008–2009: 10). Furthermore, questions are raised with respect to the (II) inability to provide social equality, as children’s social backgrounds continue to determine their success in the educational system (NOU, Citation2014: 43–44; Report to the Parliament No 16, Citation2006, 2006–2007: 22). Other problems related to schools are identified as (III) teachers’ resisting to implement educational policy (Report to the Parliament No. 11, Citation2008–2009: 27; Government, Citation2014: 20) and (IV) deficiencies compared to other OECD countries’ school organisation (NOU, Citation2002: 23; for the argument in general see; Gonon, Citation1998).

Table 2. Thematic codes of the document analysis

Regarding teacher training, we found extensive references to (V) problems with teacher training and teacher students, both for having low average grades upon their admission and for having instrumental learning strategies overfocusing on tests results during their studies (Report to the Parliament No. 11, Citation2008–2009: 30; Government, Citation2014). It is claimed that teacher students do not work in an adequate and systematic way during their studies (Government, Citation2014: 42). The policy documents in the analysed period create a narrative of the academically weak teacher student studying fewer hours per week than the average undergraduate student. Even so, their grades tend to be normally distributed (Government, Citation2014: 12). This discrepancy is interpreted as low quality in teacher training. Another problem that is addressed is (VI) variation across different teacher training programmes and, in some cases, outdated teaching practices (Report to the Parliament No. 11, Citation2008–2009: 16). Hence, a lack of standardisation across different teacher training programmes is seen as a threat to policy measures. Another way of framing the problem of teacher training is to point to (VII) structures of teacher training, including insufficient assessment of students (Report to the Parliament No 16, Citation2006, 2006–2007: 79), the academic staff’s low competence (Report to the Parliament No. 11, Citation2008–2009: 10), little emphasis on subject specialisation and poor coherence between theoretical knowledge and practical use. It is also claimed that teachers lack enough formal competence in their subjects (Government, Citation2014: 6). The final problem identified in the official reports is the (VIII) comparison to other nations (for the argument in general see Gonon, Citation2011). In this context, the claim is that Norwegian teacher training is substandard to Danish (Report to the Parliament No. 11, Citation2008–2009: 61), Finnish (Report to the Parliament No. 11, Citation2008–2009: 62, 76, 89–80) and Swedish teacher training (Report to the Parliament No. 11, Citation2008–2009: 62).

Overall, the analysis illustrates how both the school system and teacher training are heavily scrutinised in the educational documents. The measures intend to generate a more integrated system for evaluation, comparison and standardisation. Some of the criticisms in the official reports may be considered universal challenges or questionable unless they are evaluated from a strict governance perspective that demands complete adherence to official policy and political rhetoric.

6. Three cases of educational contradictions

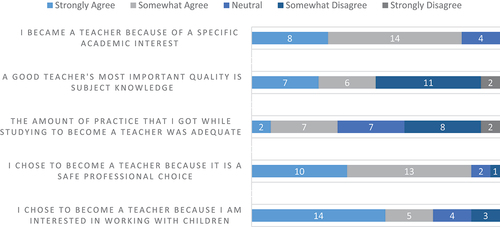

It is of interest how teachers and other actors within teacher training experience the ongoing reforms and shifts occurring within teacher training and the school system. While teacher trainers seek legitimacy through local implementation of the official framework, students are subject to several contradictory expectations. One year after obtaining their teacher degree, a questionnaire containing both qualitative and quantitative questions was sent to the 32 novice teachers interviewed in 2015. 26 of the 32 answered the quantitative questions. We found that most teachers in our study had chosen a teaching career because they were interested in children’s wellbeing in school. Almost three-quarters of the students were initially motivated to become teachers because of their general interest in children. More than 80% answered that they found teacher training to be a safe professional choice, the same level as with those who reported an academic interest in teaching (see Figure ).

Figure 1. Questionnaire with the novice teachers One year after obtaining the degree, selected questions (N=26).

These findings illustrate that while the teacher role may be associated with academic content, it is also attracting students because of their pedagogical interests and also because teaching is a secure job in the welfare state context. In the following three sections, we identify and describe different cases of adaptation and institutional decoupling in the relationship between teacher training and the school system.

6.1. The irrational student

Our first case focuses on the idea of teacher students as irrational actors. This idea is not limited to an established narrative in the policy documents; it is also expressed by the professors at the universities and university colleges that are training teachers. Several of the professors in our study describe how teacher students have problematic expectations of education and how they tend to undermine their own status as students and future teachers. In the following quote, a professor describes the students’ critique of the teacher training organisation:

Students in teacher training are critical of their education in general – more so than others, and it is like that all over the country. They tend to “foul their own nest”. Students in other fields, for example in economics, are preoccupied with their status. They brag about their education, but this aspect, teachers do not understand. (Margrete,Footnote1 supervisor, 2015)

During our interviews, both teacher trainers and counsellors demonstrated little interest in students’ feedback and critique of the teacher training programme. They are less preoccupied with critiques from students who seek more practice, a more coherent education and better connections between education and professional life. In the following quote, Maria, who is a primary school teacher, explains how she tends to play down subject matters highlighted in her training and instead focuses on a good learning environment and on the children’s wellbeing:

The most important aspect I have learned about being a teacher is how substantial relationships are for wellbeing and learning for both teachers and students. Earlier, I had the impression that the subject matters were at the core of our practice, but this view changed rather rapidly after my first experiences from the practice field. (Maria, novice teacher, 2016)

Teacher students’ practical orientation diverges from the political focus on increasing subject-specific knowledge. In our study, we found that subject matter training is more or less taken for granted and is neither stressed nor problematised by the novice teachers. By disregarding teacher students’ expectations and demands for a more practical and coherent education, educators, bureaucrats and policymakers fail to recognise how the educational reforms force novice teachers to bridge the gap between theory and practice after finishing their education. If we consider the novice teachers in this study, 19 out of 24 reported one year after obtaining their teacher degree that they taught subjects in school without having any formal qualification through credit points. Several also taught other age groups of pupils who were not matched with the specialisation acquired during their teacher training.

The first year as a professional teacher is heavily influenced by how teachers adapt to an organisational context and environment (Amdal & Willbergh, Citation2020). While the problem discourse in policy documents upholds a top-down approach, our informants demonstrate how competencies required in schools are broad and complex and are difficult to rationalise and control. Our novice teachers reported that they were not trained to address the bureaucratic demands of reporting locally, especially in cases of children with special needs or parental contact. 80% of the novice teachers had worked as substitute teachers during their studies. As teacher training reforms take education in an increasingly academic direction with a strong focus on formal competence and a less explicit focus on the negotiation aspects of being a professional teacher, additional practice becomes a strategic asset. These are all practical aspects overlooked in the current public discussion of what is required of a good teacher.

6.2. Dropout as a structural problem

Our second case is based on the strong and consistent focus on dropout from the teaching profession (Government, Citation2018). It is the government’s goal to reduce dropout from teacher training programmes and from the teaching profession in general (Roksvaag & Texmon, Citation2012). Based on our analysis of how professors and teacher students understand dropout, it serves as a mechanism to determine who is best suited for teaching:

I wish more students could find out they are not suited the first year, because too many leave the education too late. I think that is too costly for them and the society. The suitability requirement should come earlier […] This assessment we normally just use for those students who are unable to be guided to leave, or who do something really inappropriate during their studies. (Borghild, supervisor, 2015)

To decide who is suited for teaching, educators use their own discretion and negotiate between ideals of what constitutes suitable as opposed to non-suitable teachers. This rather heuristic idea of dropout as an organisational function shows how it can be regarded as a mechanism to ensure qualified candidates. Hence, the strategies of educators to ensure good teachers reach beyond the national requirements and policy discourse. Even if certain candidates can take their exams and follow the national requirements, their educators and fellow students might think they are not suitable. The following quote illustrates how a student regards the question of suitability in terms of candidates’ personal abilities:

Someone can be really good in their subjects, but they don’t have any interest in the relational aspects [of the teacher profession]. And maybe their character makes them difficult for kids to trust […] You need to have social antennas. (Sofie, student teacher, 2015)

Dropout from the training programme ensures a population of teachers with appropriate professional focus and motivation. Many of the students begin teacher training with vague ideas about what their professional role will require in practice, including communicative skills or bridging theory and everyday life. A process of guiding students to leave their training or simply letting students drop out after they fail either their practical training or exams is revealed as a practice that ensures that core professional myths (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977) of good teachers keep defining who completes the teacher training.

6.3. Bureaucratic disinterest in the field of practice

Our third case illustrates the gap between formal structures and the local framework of implementations at the school level. Employees interviewed at the UDIR showed little interest in local variation and actual organisational life, as the educational sector is primarily analysed through a lens of implementation, quality assurance and evaluation:

We work on developing a national curriculum, implementation and school development. […] Generally, when we are out talking to people in the school sector, we see the importance of our work. To see what the school reform is and what this demands locally, it has to be connected to the governing documents. […] It is demanding, and we experience how those working in schools don’t connect these things properly. (Tine, government official, 2015)

As representatives for the UDIR, these actors have adapted the language of new public management. They perceive teachers’ challenges in everyday practice as irrelevant to the future development of the sector. From their perspective, negotiations taking place between actors with diverging expectations in the educational sector are signs of unwillingness to follow the streamlined and well-designed initiatives. As an ultimate example of decoupling (Boxenbaum & Jonsson, Citation2008), government employees simply portray the official mandate of their own organisation, giving the impression of an educational institutional environment in which the rational simplification of educational organisations has left the Norwegian educational system in a loosely coupled and fragmented state. This is an organisational paradox, as the goal of separating educational organisations and politics has been to create a more coherent system (Helsvig, Citation2014).

7. Discussion

Drawing upon the neo-institutional approach, which emphasizes the impact of external pressures and the legitimation of organisational practices, our study gains insight into how the formal structures of teacher training institutions interact with the dynamic realities of everyday practices. Applying Bacchi’s “problematising” concept, grounded within the neo-institutional lens, enabled us to unveil the hidden assumptions shaping educational problems and provided a nuanced perspective on the challenges faced by teacher training institutions. Isomorphism, a central concept of the neo-institutional framework, reveals its significance as we consider the implications of our findings in the context of a nation’s proclivity to import international policy ideas. In the case of Norway, the embrace of global policy blueprints—importing practices and recommendations from international organisations like the OECD—has engendered a complex interplay between external pressures and domestic educational practices. The adaptation and institutional decoupling observed in teacher training organizations mirror the pressure to conform to these global blueprints.

The Nordic welfare state is a complex system of control, evaluation and policy. A strong public sector and substantial social and economic redistribution encircles the central government’s financial spending. Education is a free public good and more than 96% of all children attend public primary and lower secondary schools (Statistics Norway, Citation2021). At the same time, this situation creates a particularly strong public interest in educational policy. Constant evaluation becomes an important source of institutional legitimacy in the educational sector, although little is known about the complex relationship between formal structures and day-to-day activities in educational organisations. Additionally, frequent system reforms uphold an image of an active, up to date and professional government.

In contrast, the empirical evidence of this paper shows how central actors in the educational system are side-lined. This is a problem in terms of giving different stakeholders a voice, and it undermines attempts to approach the various roles and functions of the teachers and teacher training in society. The problems identified in the white papers, green papers, legislation and political strategy documents are primarily framed in a policy logic highlighting the formal structure and its stakeholders at the expense of the organisational factors within. It is interesting to observe how problems identified within the school domain are explained by the quality of teacher training, staff and students, without a discussion on how these aspects are interrelated. One challenge in the narratives revealed is that these tend to underestimate and oversimplify the competence required of the teacher students and teachers. Another challenge is the lack of interest in the existing tensions and contradictions built into the education system in practice. Consequently, we observe several cases of adaptation and institutional decoupling (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977) in the relationship between teacher training and the school system.

Almost regardless of the empirical substance behind claims found in the Norwegian policy documents, it is obvious that several “problems” are general features found in most educational systems, including other Nordic nations and despite the PISA scores. This is clearly the case if we examine criticism of inadequate goal attainments, an inability to conquer social inequality or resisting implementation of national policy at the school level. From a policy perspective, architects and evaluators of the school system may ideally wish for a system with clear goals, a high degree of transparency and accountability. At the same time, transparency in policy and implementation must also be understood against a counter logic at the organisational level, with an increased policy objective for schools and teachers in the context of a welfare state (Rapp, Citation2018). The school is not just a public domain of learning and socialisation; it is also increasingly intertwined with the welfare system. The official claim of organisational deficiencies in the way schools are organised in Norway compared to other countries may be seen as part of an ambition to reduce the autonomy of schools, principals and teachers. In summary, this may be seen as an argument to further strengthen what is essentially already a well-organised and integrated school system at the national and local levels.

The problems identified with the overall quality of teacher students in terms of low average grades upon admission and limited time spent per week on study are at least empirically substantiated and are concerns that both legislators and the teacher training programmes share. However, as most of our novice teacher interviewees also combined their studies with jobs as substitute teachers, this clearly contradicts the problematic notion of lazy teacher students.

As quality in education is increasingly understood due to the new measurement systems (NOKUT, Citation2016, Citation2017), the logic of the reforms tends to be a simplification of what constitutes high-quality teacher training. This approach is driven by an economic bias promoted by the OECD to ensure that the government is economically effective. Variables such as the production of teachers, credit points and other measurable outputs from educational organisations are based on a problematisation discourse (Bacchi, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Bacchi & Goodwin, Citation2016). These problems are in sharp contrast to an educational system and a teacher profession that was regarded as a success in Norway.

Our three cases illustrate several difficulties with the strong belief in educational governance through political reforms at the expense of a more comprehensive debate over the various functions the school system and teacher training are supposed to fulfil. It may also be argued that the debate tends to be trapped in arguments over actors’ rationality, interests and motivation. Consequently, we are left with a discussion of rational or irrational actors in terms of individual interests and formal organisation at the expense of a discussion on how to think of the school system as a network of organisations and an integral part of the state and welfare system (Meyer & Benavot, Citation2013; Meyer & Rowan, Citation2012). What in theory may appear as irrational students downgrading the merit of their teacher training and as a student culture of complaint, conforms to a criticism found in the document analysis. Relying heavily on legitimation may also potentially undermine the teaching profession. The problem with accepting the idea of irrational students as an objective truth is that the students compensate for a lack of practice experience as substitute teachers. Based on the results presented in this article, one may also ask how the newest teacher reform in Norway creates a narrower translation of formal teacher competence and subject specialisation into an education sector.

A focus on formal organisation and on how things ideally should be tends to disregard the challenges faced by teachers and other actors within teacher training. The analysis illustrates how central actors decouple their practices and understandings from the official framework, challenging official definitions of problems with their own conceptions. While the teachers’ educators seek legitimacy through local implementation of the official framework, students are subject to contradictory expectations. Many have chosen a teaching career based on their interest in children’s wellbeing in schools. Their pedagogical competences and interests are, in their perspective, more-or-less taken for granted, and in their highly individualised understanding, it is up to them to bridge the gap between an increasing academic focus in education and other practical challenges in the profession.

The current evaluations of teacher training in Norway have a strong bias, as they seek to reveal how actors are not implementing reforms as they should; they take for granted that the reforms themselves serve as solutions and show little interest in unintended consequences. The interviews with representatives at the UDIR clearly confirmed a policy view that is framed in a language of problems and policy goals in governing documents, saying “those working in schools don’t connect these things properly”. This is not to say that the bureaucrats in charge of implementation, quality assurance and evaluation are necessarily unaware of challenges in daily work at the school level, but those challenges tend to be discussed in terms of actors’ unwillingness and inability to follow policy. Paradoxically, the intention of rationalising the education sector has been to create a more coherent and integrated system, which has improved the quality of the learning output. This paradox highlights the tension between the policymakers’ desire to achieve specific policy goals and the unintended consequences that may arise from implementing these policies. The focus on compliance and achieving policy goals may overlook the complexities and nuances of the education system, leading to a narrow and biased assessment of teacher training that may hinder the intended improvement of the learning output. The strategic embrace of global policy recommendations, often framed as solutions for educational enhancement, further underscores the intricate dynamics of institutional isomorphism. While these blueprints may be intended to promote efficiency and improved outcomes, our study, anchored within the neo-institutional framework, underscores the nuanced realities where imported policies intersect with local contexts.

8. Conclusion

Endless reforms and experimentation in any educational system tend to be associated with a risk of overlooking what is working well. Almost regardless of whether we focus on the organisations in charge of teacher training or on schools, organisations are largely based on day-to-day activities, social interactions and problem solving. Many problems are solved daily to get things done. What constitutes problems in daily work at a workplace or in an educational setting is, however, less obvious once we make comparisons to official policy programmes, goals and assessments at the system level. Within the contemporary research on Norwegian teacher training, a gap exists concerning the practical implications of international trends. While international ideas dominate the policy discourse, little exploration has for example been undertaken to understand how Norway’s unique historical conditions shape the value orientation of professional groups like teachers. Our study endeavours to bridge this gap by delving beyond prevailing international concepts and highlighting the national context.

The Norwegian case is of interest because the policy problems that are defined are met with a strong belief that the public sector, including higher education and the school system, are better off when governed by principles associated with a private market actor and their rationality to optimise gains. A major problem with this strong belief in market- and incentive-driven policy is that it has obvious limitations. Even if the organisations of the welfare state, including the educational system to a large extent, are based on accountability and market-based principles, in Norway, such activity is financed by tax revenues.

Another issue is that the current idea of a rational educational governance is based on a simplistic view of the role of the educational system and what the different stakeholders define as problems. Almost regardless of the economic bias built into the evaluation regime of teacher training, the school system and other branches of the public sector, there are currently no acknowledged alternatives to measure the success of an educational organisation. The case of Norwegian teacher training illustrates how this regime and type of educational governance have left the teacher profession with substantially less power and control, at the same time they hold a societal mission extending beyond knowledge transfer—they are agents of social welfare and citizenship. Our argument champions a more comprehensive analysis.

We conclude that the quest for enhancing teacher training should not rely on external policies. The Norwegian case illustrates several challenges associated with global educational governance, including the perspective that teacher training reforms will lead to improved learning outcomes. Despite recent investments in Norwegian teacher training, it is not self-evident that this strengthens the overall quality of teachers. In an era of rapid educational reforms, our findings highlight the value of embracing a participatory approach to policymaking and reforms at a slower pace.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The names of the interviewees are anonymised.

References

- Advisory Panel for Teacher Education. (2020). Transforming Norwegian teacher education: The final report for the international advisory panel for primary and lower secondary teacher education (Report no. 3-2020). Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education. https://www.nokut.no/globalassets/nokut/rapporter/ua/2020/transforming-norwegian-teacher-education-2020.pdf

- Amdal, I. I., & Willbergh, I. (2020). Det produktive praksissjokket. Nyutdannedes læreres fortellinger om lærer-elev-forholdet i overgangen fra lærerutdanning til lærerarbeid. Acta Didactica Norden, 14(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.8421

- Bacchi, C. (2012a). Introducing the “what’s the problem represented to be?” approach. In A. Bletsas & C. Beasley, ed. Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic interventions and exchangespp. 21–24. University of Adelaide Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/UPO9780987171856.003

- Bacchi, C. (2012b). Why study problematizations? Making politics visible. Open Journal of Political Science, 2(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2012.21001

- Bacchi, C. (2016). Problematizations in health policy: Questioning how “problems” are constituted in policies. SAGE Open, 6(2), 215824401665398. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016653986

- Bacchi, C., and Eveline, J. (2010). Mainstreaming politics: Gendering practices and feminist theory. University of Adelaide Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/UPO9780980672381

- Bacchi, C., & Goodwin, S. (2016). Making politics visible: The WPR approach. Poststructural Policy Analysis: A Guide to Practice, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52546-8_2

- Bakken, A., & Elstad, J. I. (2012). For store forventninger - Kunnskapsløftet og ulikhetene i grunnskolekarakterer (Vol. 7). NOVA Rapport. Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring.

- Bergem, O. K. (2018). Undervisningskvalitet i norsk skole: status, trender og utfordringer: Analyser basert på data fra PISA og TIMSS i perioden 2000–2015. In Tjue år med TIMSS og PISA i Norge: Trender og nye analyser (pp. 199–221). Universitetsforlaget.

- Boxenbaum, E., & Jonsson, S. (2008). Isomorphism, diffusion and decoupling. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), The sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 78–98). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200387.n3

- Burawoy, M. (2009). The extended case method: Four countries, four decades, four great transformations, and One theoretical tradition. University of California Press.

- Camphuijsen, M. K., Møller, J., & Skedsmo, G. (2021). Test-based accountability in the Norwegian context: Exploring drivers, expectations and strategies. Journal of Education Policy, 36(5), 624–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1739337

- Caspersen, J., & Smeby, J. C. (2023). Research-based teacher education in Norway – a longitudinal perspective. International Journal of Educational Research, 119, 102177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102177

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2021). Rethinking teacher education: The trouble with accountability. Oxford Review of Education, 47(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1842181

- Cochran-Smith, M., Grudnoff, L., Orland-Barak, L., & Smith, K. (2020). Educating teacher educators: International perspectives. The New Educator, 16(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1547688X.2019.1670309

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Zeichner, K. M. (2009). Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203864043

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). How teacher education matters. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003002

- Eagleton, T. (1991). Ideology. An introduction. Verso.

- Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

- Gallagher, K. S., & Bailey, J. D. Eds. (2000). The politics of teacher education reform: The national commission on teaching and America’s future. Corwin Press.

- Gonon, P. (1998). Das internationale Argument in der Bildungsreform: Die Rolle internationaler Bezüge in den bildungspolitischen Debatten zur schweizerischen Berufsbildung und zur englischen Reform der Sekundarstufe II. Peter Lang.

- Gonon, P. (2011). Die Bedeutung des internationalen Arguments in der Lehrerbildung. BzL - Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung, 29(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.36950/bzl.29.2011.9748

- Government. (2014). Promotion of the Status and Quality of Teachers Ministry of Education and Research. Retrieved February 11, 2019 https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/vedlegg/planer/kd_strategiskole_web.pdf

- Government. (2016a). Flere tar lærerutdanning. [More Students at the Teacher Education] Retrieved March 9, 2017 https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/flere-tar-larerutdanning/id2518114/.

- Government. (2016b). GNIST indikatorrapport. Retrieved February 11, 2019 https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/6b3b8534bb6749558747a51ab77d23ae/gnist-indikatorrapport-2016_pdf

- Government. (2016c). Innspill til stortingsmelding om kvalitet i høyere utdanning. [the official homepage for the hearing regarding a white paper on higher education] Retrieved February 11, 2019 (https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/innspill-til-stortingsmelding-om-kvalitet-i-hoyere-utdanning/id2476318/)

- Government. (2018). Teacher education 2025. National strategy for quality and cooperation in Teacher education. Ministry of Education and Research. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/larerutdanningene-2025.-nasjonal-strategi-for-kvalitet-og-samarbeid-i-larerutdanningene/id2555622/

- Gunnes, T., & Knudsen, P. (2016). LÆRERMOD: Forutsetninger og likninger. Statistics Norway.

- Helsvig, K. (2005). Pedagogikkens grenser: kampen om norsk pedagogikk ved Pedagogisk forskningsinstitutt 1938-1980. Abstrakt forlag.

- Helsvig, K. (2014). 1814-2014 Kunnskapsdepartementets historie. Kunnskapsdepartementet.

- Helsvig, K. G. (2022). Kunnskapssamfunnet og nasjonen: –den internasjonale vendingen. Nytt norsk tidsskrift, 1(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.18261/nnt.39.1.2

- Report to the Parliament No. 11. (2008–2009). Læreren–rollen og utdanningen. Ministry of Education and Research.

- Lawn, M., & Lingard, B. (2002). Constructing a European policy space in educational governance: The role of transnational policy actors. European Educational Research Journal, 1(2), 290–307. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2002.1.2.6

- Lepperød, T. (2016). På disse skolene går landets beste 5. klassinger, https://www.nettavisen.no/na24/pa-disse-skolene-gar-landets-beste-5-klassinger/3423289549.html)

- Lindblad, S., & Popkewitz, T. (Eds.). (2006). Educational restructuring: International perspectives on traveling policies. IAP.

- Lukes, S. (2006). Power: A radical view. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-80257-5_2

- Mazandarani, O. (2022). The status quo of L2 vis-à-vis general teacher education. Educational Studies, 48(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1729101

- Meyer, H.-D., & Benavot, A. (Eds.). (2013). PISA, power, and policy: The emergence of global educational governance. Symposium Books Ltd https://doi.org/10.15730/books.85

- Meyer, H.-D., & Rowan, B. (2012). New institutionalism in education. State University of New York Press.

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

- Mundy, K. (2007). Global governance, educational change. Comparative Education, 43(3), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060701556281

- Murray, F. B. (2000). The role of accreditation reform in teacher education. Educational Policy, 14(1), 40–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904800014001005

- NOKUT. (2016). Stortingsmeldingen om kvalitet i høyere utdanning- NOKUTs innspill https://www.nokut.no/contentassets/5979c996834c47f4a296269de44436b0/stortingsmeldingen-om-kvalitet-i-hoyere-utdanning—nokuts-innspill.pdf.

- NOKUT. (2017). Internasjonal rådgivingsgruppe møter grunnskolelærermiljøene. https://www.nokut.no/nyheter-2017/Internasjonal-radgivingsgruppe-moter-grunnskolelarermiljoene/

- NOU. 2002. Førsteklasses fra første klasse. [Official Norwegian Report/Greenpaper]. Utdannings- og forskningsdepartementet.

- NOU. 2014. Elevenes læring i fremtidens skole - et kunnskapsgrunnlag. [Official Norwegian Report/Greenpaper]. Kunnskapsdepartementet.

- Parreira Do Amaral, M. (2011). Emergenz eines internationalen bildungsregimes? International educational governance und regimetheorie. Waxmann. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-92615-5_10

- Parreira do Amaral, M., Steiner-Khamsi, G., & Thompson, C. (Eds.). (2019). Researching the global education Industry. Commodification, the market and business involvement. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04236-3

- Pereyra, M. A., Kotthoff, H.-G., & Cowen, R. (2011). PISA under examination. Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-740-0

- Popkewitz, T. S. (1987). Critical studies in teacher education: Its folklore, theory and practice. Taylor & Francis.

- Ragin, C. C. (1989). The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. University of California Press.

- Ragin, C. C., & Becker, H. S. (1992). What is a case - exploring the foundations of social Inqury ( red). Cambridge University Press.

- Rapp, A. C. (2018). Organisering av social ojämlikhet i skolan. En studie av barnskolors institutionella utformning och praktik i två nordiska kommuner. Department of Sociology and Political Science [ Doctoral thesis], Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- Report to the Parliament No. 16. (2006–2007). Early intervention for lifelong learning. Ministry of Education and Research.

- Rogne, M., Svensen, K.-A. M., & Munthe, E. (2012). Med god gli i kupert terreng : GLU-reformens 2. år. Følgegruppen for lærerutdanningsreformen. Ministry of Education and Research.

- Roksvaag, K., & Texmon, I. (2012). Arbeidsmarkedet for Lærere og førskolelærere fram mot år 2035 (Report No. 18). Statistics Norway. https://www.ssb.no/a/publikasjoner/pdf/rapp_201218/rapp_201218.pdf

- Sjøberg, S. (2018). The power and paradoxes of PISA: Should Inquiry-Based Science Education be sacrificed to climb on the rankings?. Nordic Studies in Science Education, 14(2), 186–202. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.6185

- Skagen, K., & Elstad, E. (2023). Teacher education in Norway. In Teacher education in the Nordic region: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 175–193). Springer International Publishing.

- Smeplass, E. (2018). Konstruksjonen av den problematiske lærerutdanningen- Lærerutdanningen i et institusjonelt og politisk landskap [The Construction of the Problematic Teacher Education – Teacher Education in an Institutional and Political Landscape], Department of Sociology and Political Science [ Doctoral thesis], Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- Smeplass, E., & Leiulfsrud, H. (2022). A widening gap between official teacher training and professional life in Norway. Interchange, 53(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-021-09445-1

- Smith, K. (2021). Educating teachers for the future school-the challenge of bridging between perceptions of quality teaching and policy decisions: Reflections from Norway. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2021.1901077

- Statistics Norway. (2021). Pupils in Primary and Lower Secondary School. https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/statistikker/utgrs

- Swedberg, R. (2012). Theorizing in sociology and social science: Turning to the context of discovery. Theory and Society, 41(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-011-9161-5

- Swedberg, R. (2014). The art of social theory. Princeton University Press.

- Swedberg, R. (2020). Exploratory research. In C. Elman, J. Gerring, & J. Mahoney (Eds.), The production of knowledge: Enhancing progress in social science (pp. 17–41). Cambridge University Press.

- Swedberg, R., & Swedberg, R. (2014). Theorizing in social Science : The context of discovery, the context of discovery. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804791199

- Therborn, G. (1999). The ideology of power and the power of ideology. Verso.

- Trippestad, T. A., Swennen, A., Werler, T., Brennan, M., Maguire, M., Smagorinsky, P., & Ellis, V. (Eds.). (2017). The struggle for teacher education: International perspectives on governance and reforms. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474285568

- Union of Education Norway. (2014). Governance and power shifts in the education sector – the autonomy and collective influence of the profession. policy briefing 6/2014.

- Utdanningsforbundet. (2017). Fakta: Rekruttering og frafall blant lærere. Retrieved February 11, 2019 https://www.utdanningsforbundet.no/nyheter/2017/fakta-rekruttering-og-frafall-blant-larere/

- Verger, A., Fontdevila, C., & Parcerisa, L. (2019). Reforming governance through policy instruments: How and to what extent standards, tests and accountability in education spread worldwide. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(2), 248–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1569882