Abstract

Peace education has long been integrated into the higher education curriculum to equip students from diverse cultural backgrounds, languages, religions, regions, and lifestyles with the knowledge, skills, and values necessary to foster a culture of harmony and prevent future conflicts. This systematic research examines the peace education concept and practice in action from various universities in the world garnered from research articles published within the last 5 years between 2017 and 2021. This study uses international database in the form of articles in Scopus journals using such keywords in the Scopus database (scopus.com). The keywords we used were “peace education and higher education”, “peace education and university”, “peacebuilding and higher education”, and “peacebuilding and university”. Articles from many databases are selected using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) approach. From the results of the review of 10 articles, this study explores four emerging themes on peace education concept and practice which include 1) universities collaborating to develop peace programs; 2) peace education teaching; 3) peace education curriculum; and 4) peace education hidden curriculum. The analysis result shows that peace education needs to be prioritized to create a safe, harmonious, and peaceful atmosphere among students and all academic society members. This article is helpful for universities, particularly to help develop peace values in education.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The present systematic review synthesizes findings of qualitative studies on how higher education participates in peace building through conceptualizing and practicing peace education. Anchored in PRISMA methodology, out of 1.542, 10 articles matched with inclusion strategy and published in scholarly indexed journals between 2017 and 2021 were collected, synthesized, and analyzed using thematic analysis. The study found out that university partnership, peace education teaching, peace education curriculum, and peace education hidden curriculum contribute to the development of peace education in higher education contexts. This systematic review offers policy-making and practical implications for universities interested in integrating peace education into higher education curriculum.

1. Introduction

The role that universities play in studying and pioneering peace education is highly needed, to help create a peaceful, safe, and harmonious atmosphere throughout the world. Universities can contribute to the development of peace education which educates students to be agent of peace (Oueijan, Citation2018). Similarly, Milton (Citation2020) emphasizes that peace education is highly necessary for higher education to build peace in Libya after a prolonged conflict in the region.

Peace education also plays an important role in subsiding and neutralizing the history of terrorism which occurs at a global scale. Millican et al. (Citation2021) suggest that higher educational institutions need to ensure that peace education goes well. For this purpose, students can be invited to critically study the impacts of terrors for the world’s peace. For example, they can discuss the impacts of terror occurring in Asia such as Bali Bombings I and IIFootnote1 in Indonesia. Having reflected on those events, they can view those cases as a peace-related issue, get the idea of the source of conflict, and find the solution to creating peace (Sahfutra, Citation2012). Furthermore, apart from addressing acts of terrorism, students can be encouraged to explore other factors contributing to conflicts, such as discrimination against individuals based on their religious beliefs. This discrimination can be seen as contradictory to the principles and teachings of the respective religion itself (Sardi, Citation2012). In essence, individuals who discriminate against others on religious grounds can be viewed as contradicting their own faith and undermining the fundamental purpose of their religion. Despite its importance, Chelule (Citation2014) observed that few public universities in Kenya offer peace education courses due to the lack of qualified faculty, limited availability of relevant textbooks, and training materials (especially those by African scholars).

Some literatures have discussed peace education in universities and provide explanation on the importance for higher education in formulating peace education. To name a few, Adelson (Citation2000) argues that universities play a crucial role in critical analysis necessitating the establishment of peace education centers. Furthermore, John (Citation2018) stipulates that peace education serves as “a counter force and restorative process” (p. 54). Meanwhile, a mixed-method study conducted by Shehi et al. (Citation2018) found out that there is a clear emphasis on human-centered and relationship-centered subjects related to peace evident in both university curricula and student responses. However, a study discussing peace education concept and practice resulted from qualitative studies remains under-explored. Therefore, this research focuses on documenting peace education concept and practice in universities from the review of literature published by reputable publishers for the last 5 years. In the present systematic review study, the term “concept” refers to the principles that underpin the research findings. It represents the overarching concept that guides the investigation and analysis. Meanwhile, “practice” pertains to the practical implementation and real-world applications of the peace education concepts identified in this study. It explores how these ideas are put into action and integrated within educational settings as found in the studies.

It is expected that this research can give a conceptual and practical contribution to how universities can incorporate peace education in their curriculum concretely. Additionally, this research provides a practical implication on how to teach peace in universities by developing anti-violence, peace-loving, harmonious, democratic, human rights-upholding, tolerant, multicultural, and willingness to collaborate between and among religious groups and having positive attitude towards diversity.

2. Literature review

2.1. Peace education

The concept of peace education has been extensively discussed in the literature. From a pedagogical perspective, the pedagogy of the oppressed proposed by Freire (Citation1970) has played a significant role in advancing dialogical teaching methods for peace education. These methods aim to foster learning and knowing process that inherently incorporates the theorization of experiences shared within the dialogue. However, Hajir and Kester (Citation2020) argue that this concept prioritizes reason and rational dialogue as vehicles for transformation and liberation but overlooks the underlying unequal power dynamics that exist, including the suppression of non-rational ways of knowing and being. Thus, Zembylas (Citation2018) conceptualizes critical peace education (CPE) and postcolonial and decolonial thinking direct their attention towards matters of structural inequalities and aim to empower students with the ability to effect transformative change. This involves the creation of new epistemic, social, and political frameworks that promote social justice and foster a sense of agency among individuals (Bajaj, Citation2015; Zembylas, Citation2018). In other words, peace education needs to address power dynamics, structural inequalities, and empower students for transformative change in the field of peace education.

In this article, the concept of peace education is referenced from Sayaee Development Organization (Citation2000) who defines peace education as a process of teaching knowledge, skills, attitudes and values needed to prevent conflicts and violence, resolve conflicts peacefully, and creating a conducive atmosphere for peace. Peace education is based not only on skills and knowledge but also on arts, a creative process originating from imagination. The arising question is that: How can we create peace culture and provide rooms for others to participate? As a civilized way of doing and living, peace implies as an embodied and relational experience, rather than merely an intellectual endeavor (Lehner, Citation2021).

According to Kartadinata et al. (Citation2015), a peace education program ideally meets the following five components. First, collaboration should be presence among students. Second, peace education provides rights and obligations to students fairly and is beneficial to all. Third, students should be trained to put controversy-constructive way into practice to allow them to have the skills to deal with difficult situation. Fourth, students should also receive lessons on how to negotiate in an integrated manner and to serve as a mediator in resolving conflicts constructively. Finally, students shall receive education on the importance of civil values in realizing community interests in the long run.

2.2. Peace education in higher education

Universities play a highly important role in peace education since they serve as a central hub where students can extensively learn and practice the concept of peace education. Millican et al. (Citation2021) suggest that students need to be exposed to education on “life skills” such as negotiation, preventive diplomacy, emotional and empathy management, all important intra- or interpersonal elements in peace education. It is imperative to provide students with peace education to allow them to have knowledge and skills to resolve conflicts amiably and get the idea of non-violent alternative to minimize conflicts (Buckland, Citation2005; Smith & Vaux, Citation2005). In other words, peace education will encourage students to show more democratic, moderate, peace-loving, and tolerant attitudes.

Empirically, while Kester (Citation2013) conducted a study on the medium-term impact of peace education training for educators or lecturers to understand its broader implications, the results indicated that all the educators or lecturers who participated in the study continued their efforts to develop peace education programs or policies in their respective home countries. Additionally, Kester (Citation2017) argued that peace and conflict education has gained popularity as an approach to fostering social justice learning in higher education institutions in recent decades.

Universities also play an important role in peace education since they will graduate those who will eventually lead the community, either formally or non-formally. In other words, universities serve as a means of training for the youth in peace education. Millican et al. (Citation2021) report that peace education should be held by universities, considering their important role in peace education for the state’s youth since they are the right place to nurture peace education. The importance of higher education, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected states, in helping the youth develop peaceful habit and helping citizens and future leaders understand the importance of peace development has been widely acknowledged (Milton, Citation2020). It is therefore understandable that peace education for students in universities aims at making students accustomed to peaceful behavior and harmonious, anti-violence, and tolerant culture.

3. Research method

This study is a systematic review of those publications on peace education concept and practice at universities. It was carried out based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline (Moher et al., Citation2009). This systematic review attempts to address the following research question: how is the peace education conceptualized and practiced at universities based on the qualitative research results within the last 5 years. The review’s results are expected to provide valuable insights to teacher educators on generally considering the incorporation of peace education practices in their respective situations and contexts.

3.1. Search strategy

This study was conducted in 2022 to review the articles published in English on the peace education concept and practice at universities. To that end, we studied the Scopus database from 2017 to 2021 (5 years). The keywords we used were “peace education higher education”, “peace education university”, “peacebuilding higher education”, and “peace building university”. Using AND, the keywords were combined and written in the search feature of Scopus database by title, abstract, and keywords.

3.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In this study, articles were selected based on specific criteria. These criteria include (1) focusing on the implementation of peace education at universities, (2) being published in English, (3) having publication dates between 2017 and 2021, (4) being published in journals indexed in Scopus and Web of Science databases, (5) utilizing qualitative research methods, and (6) falling within the subject areas of social science and arts and humanities. Consequently, articles published as book chapters, proceedings, and monographs were excluded from consideration. Furthermore, any articles that did not meet the search criteria were also excluded. Examples of such exclusions include studies employing mixed-method research, survey study, or other quantitative research methods. Moreover, studies involving participants other than university students, lecturers, or university staff, as well as research focusing on school-level or teacher leadership were also excluded.

3.3. Research procedure

The search was conducted in Scopus database using keywords “peace education higher education”, “peace education university”, “peacebuilding higher education”, and “peacebuilding university” between August and November 2022. The keywords are connected with the word “and”. For example, in the journal database, we searched the articles using combination of keywords “peace education and university”. Furthermore, the first search did not use any filter, then the next one used year, subject area, and document type as the filter. The result of those searches can be seen in the following Table .

Table 1. Result of search by keywords

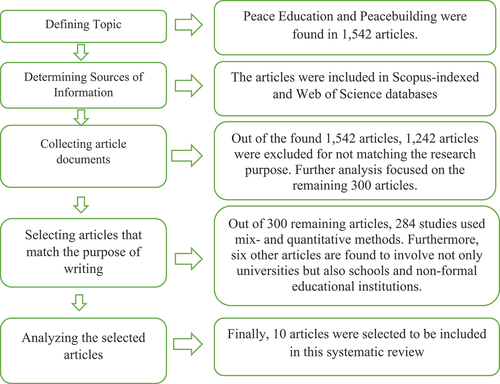

The procedure to select the articles was done through the following stages. First, the title was checked for its matching with the used keywords. Second, if the title matched, the abstract was checked for its matching with the set criteria. Third, if the abstract matched the set criteria, the writers would analyze the focus study and result of research for synthesizing the research result. Finally, from the analysis, 10 articles were selected for further analysis since they met the criteria in this study (see Figure ).

Using the PRISMA approach, 1542 articles were found to contain the keywords peace education, higher education, and peace building in Scopus database. From this number of articles, 10 articles were selected for further analysis. These articles were selected for matching the research objective which portrayed peace education concept and practice at universities. To support the analysis of the topic above, some research results in the form of a matrix which included the authors, titles, year of publication, objectives, type of research and research results are presented in the table (see the Appendix).

Using thematic content analysis technique (Gibson & Brown, Citation2009), this study reviews the research findings of the articles based on “commonalities, relationships, and differences according to the data set” (p. 127). This technique was translated by coding the lexical coding and discourse of the data set. Through this process, this systematic review finds that the peace education at higher education is conceptualized through four general ideas, namely 1) universities collaborating to develop peace programs; 2) peace education teaching; 3) peace education curriculum; and 4) peace education hidden curriculum. Further details on how these concepts are implemented are discussed in the subsequent findings to demonstrate the actual practices.

4. Research findings

4.1. Universities collaborating to develop peace program

Higher education plays a role in building a sound democratic climate, in many students’ activities (Sahar & Kaunert, Citation2021). In addition, it serves the purpose of nurturing the human resources to gain knowledge, innovation, information, and creativity to advance the country further and create excellence in all state institutions. Also, universities can prevent and tackle early any root of violence and promote humanistic education values among their students. In a wider perspective, universities are encouraged to promote collaboration in peace-building programs. Millican et al. (Citation2021) suggest a cross-university program to involve the community, through a civic and transformative education, pedagogic memory, teacher training program, and international partnership. Akkad and Henderson’s (Citation2021) study reports lecturers at universities as agents of change in a post-conflict community and the challenges they have to face such as the education situation and system in their campus. Reviewing the policies in two state universities in Ivory Coast and Kenya, Johnson (Citation2019) in his research reports that in addition to the policies to deal with local conflict and the solution to resolve it, universities can also build the capacity and infrastructure of peace education. In addition, partnership with the community and ethnic alliance within the campus is also needed as an attempt to prevent violence from occurring in the community. This is because the lack of campus-community partnership might trigger conflicts (Akkad & Henderson, Citation2021; Johnson, Citation2019).

Meanwhile, Kurian and Kester (Citation2019) in their research critically study the peace and conflict among lecturers and students of PACS (Peace and Conflict Studies) in higher peace education institution of the United Nations in understanding, practicing, and experiencing the challenges and contradictions of teaching for peace in the twenty-first century. Similarly, Brantmeier and Webb (Citation2020) suggest a way to nurture peace sustainably among leaders by involving students to clarify their own core values and by checking UNESCO’s sustainable development and Earth Charter, peace leader education concept, and decent economy. Similarly, Johnson (Citation2019) found out that students could be engaged in interesting studies about conflict management working together with NGO, government, or church organization. It indicates that universities including faculty members and students can collaborate with peace education practitioners, international organizations, and local communities to promote a holistic approach to peace education and contribute to the development of sustainable peace-building initiatives.

4.2. Peace education teaching

Teaching and learning strategies can be used to nurture peace values in higher education. Kester (Citation2017) University of the Andes in Bogota, Colombia, employs pedagogies of memory and moral ethics to understand and deconstruct memories of history, culture, and personal past through reflection. Furthermore, students can learn to use the memories of their own, family members, social groups, and their relatives, and events documented in films, arts, and literary works on violence, reparation, and non-violence to prevent past violence from being repeated and to make the future better (Millican et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, underpinned in the concept of Whiteness in the pedagogy, Kester (Citation2018) observed that participants offered various pedagogical instructions in mediating peace learning such as experiential activities, Socratic dialogue, theater exercises, etc. The multi-approach learning methods by putting aside differences among students are the best method in peace education teaching and learning in universities.

The development of dialog and critical thinking as a university’s program to build peace education has to be considered as well. Kester (Citation2021) shows that this approach is important to stimulate students to think critically on diversity and deal with conflict, rather than avoiding it. In addition, Brantmeier and Webb (Citation2020) found out six main practices in teaching peace education, including 1) learning about self which encouraged students to develop personal values; 2) learning about others which allowed students to understand core values, philosophy, and practice of others; 3) systems understanding which promoted students’ system thinking development of peace; 4) awareness of ability to change the world which engaged students in a variety of peace actions; 5) action commitments which empowered students to create sustainable future; and 6) deep learning which engaged students in reflective practice. Engaging students in these reflective activities can contribute to students’ awareness development of how they see themselves and how they see others to build peace and live in harmony.

Also, universities should give lecturers and students from marginalized groups a chance to equitable access to higher education. Universities also need to have policies on diversity or multiculturalism and respect to diversity. Creating an academic atmosphere in universities constitutes the first important step to tackle potential conflict (Johnson, Citation2019). To respond to this, Kester (Citation2021) suggests that lecturers can assign their students to different seats and work in group with them. By fostering collaborative learning, students can gain valuable skills in effective communication, teamwork, conflict resolution, and embracing diverse perspectives. They can develop the ability to actively listen, engage in constructive dialogue, and find common ground with their peers. Collaborative learning also promotes critical thinking, problem-solving, and creative approaches to addressing complex issues.

4.3. Peace education curriculum

Peace-building through curriculum in higher education context is carried out through civic and transformative education module by University of Rwanda. Their curriculum covers intercultural teaching and learning, democracy and human rights education, critical discourse analysis in media, and contemporary history teaching (Millican et al., Citation2021). Kester (Citation2019) found the demands of equity policy statement in syllabi towards gender mainstreaming pedagogic objectives in necessary materials. Moreover, a consideration is also made to incorporate local wisdom into the peace education curriculum by adopting local history, geography, peace efforts from local conflict, and culture in dialog with global history and culture. Practically speaking, Kester suggests that students be involved in peace education to facilitate guest speaker from conflict-affected areas to give a perspective on peace and to share positive experience.

To develop lecturers’ capacity in teaching peace, they need to be given wider opportunities in teacher professional development. As suggested by Akkad and Henderson (Citation2021), first, lecturers have the responsibility for developing their profession by updating their teaching method and building collaboration among themselves to create a practical community. Second, lecturers play an important role in post-conflict reconstruction by making good use of their specialization to attempt reconstruction, making their students aware of their role in rebuild the country, explaining the impacts of war, and rehabilitating students after the conflict. Third, lecturers prepare the country’s future by teaching their students to shape a new generation and future leaders. Fourth, lecturers are responsible for developing students into knowledgeable and high-quality persons. Fifth, lecturers are responsible for promoting such values as tolerance, respect, responsibility, and mutual assistance as part of the world and making students aware that intolerance and ignorance are the causes of war. Sixth, lecturers are demanded to develop students’ transferable skills, such as debate, technology, problem-solving, information collection, interpersonal, communication, self-management, teamwork, and cooperation. Seventh, lecturers need to build a closer relationship with students and act as a role model. Eighth, lecturers play a role as motivations for students by implanting hope and moral support.

Lecturers also need to get a grasp of the history and conflict of the region where the students originate from, since it is possible that students in their classrooms might be traumatized that they need a special attention (Kester, Citation2021). They also have to be capable of removing the violence image in traditional textbooks, especially the one that strengthens local superiority (Kester, Citation2021). Moreover, they need to develop passion education to focus on maintaining a positive human relationship. Lecturers should welcome, encourage, and be patient in guiding students to get the idea of peace education concept.

4.4. Peace education hidden curriculum

University stakeholders also need to make policies to prevent and prohibit practical politic from developing in the universities for peace within the campus and with the community. Kester (Citation2021) suggests peace education to be included in the education as a hidden curriculum, without having to make it a separate course, thus it becomes an interdisciplinary education concept at higher education level. As Johnson (Citation2019) has shown, University of Cote d’Ivoire prohibits its student organizations from affiliating with any political party and labor union to prevent conflict within the campus and to make students focused on pursuing academic excellence. He also shows that Western Kenya University forbids politicians to come to campus unless they are invited by the campus, rather than on their own initiative. This is to prevent dangerous political discourse from developing that may lead to conflict in the campus. In their study, Akkad and Henderson (Citation2021) reported that students can be engaged in post-conflict resolution through a particular subject, such as architecture, which enabled them to develop awareness that rebuilding was simpler than rehabilitating. In other words, peace education can be instilled in the university courses although it does not explicitly discuss peace education in particular.

Furthermore, training on courses, pedagogy, and insights to enable social change and post-conflict issue resolution in students’ life also needs to be provided to lecturers and university staff (Akkad & Henderson, Citation2021). At the same time, universities need to establish a center for peace where students, the faculty, and members of the community can participate and collaborate with the peace committee in their own area (Johnson, Citation2019). Moreover, Kester (Citation2019) finds that the development of peace education program in universities needs to consider three main factors in peace education: criticism for internal work method in the field, scarcity of studies showing the personal narratives of peace educators, and the less-represented peace education concept.

5. Discussion

This study reviews peace education concept and practice in universities. Peace education serves as a procedure to develop mindset, attitude, and capacity to create highly civilized life that includes emotionally, spiritually, and culturally healthy life, to maintain dignified life, and to be capable of solving disputes amiably (Kartadinata et al., Citation2015). In the long run, as universities embrace and prioritize peace education, they can play a pivotal role in building a world where compassion and harmony prevail. The review on the role of universities in peace education can be seen from the result of Sahar and Kaunert’s (Citation2021) research who find that universities play a role in building a good democratic climate, in various students’ activities. This means that universities play an important role in nurturing democratic values for students. Milton (Citation2020) argues that when it is cross-disciplinary and integrated into the curriculum, as well as the fact that research agendas in fragile contexts are heavily donor-driven and might be strengthened, peace education can be enacted through genuine university partnerships. Furthermore, Millican et al. (Citation2021), on the other hand, record cross-university collaboration by involving the community in general in peace education. Other researchers emphasize that intense communication in and between universities will give birth to cohesive approach to dealing with post-conflict issues (Akkad & Henderson, Citation2021). In other words, these propositions confirm the important role that collaborating universities play in peace education.

Second, the development of peace education can be done through various teaching methods. As suggested, for instance, by Millican et al. (Citation2021), pedagogies of memory and moral ethics can be used to understand and deconstruct the memory of history, culture, and personal past through reflection method. Pedagogies of memory intensify the knowledge on the suffering caused by a conflict to allow mutual empathy to grow. However, Hajir and Kester (Citation2020) put a reminder that the variety of teaching methods should be informed by critical peace education teaching grounded in Freiren-informed approach such as pedagogies of resistance.

Third, a strategy needs to be selected to integrate peace education into the curriculum. Bajaj and Hantzopoulus (Citation2016) stipulate that critical peace education pays special attention to local realities and local ideas of peace by amplifying underrepresented voices through community-based research, narratives, oral histories, and locally developed curricula. Peace curriculum development can consider giving lecturers opportunities for teacher professional development. Lecturers play an important role in teaching peace education. Akkad and Henderson (Citation2021) report that lecturers play the role of agents of change in post-conflict community. Also, they are responsible for developing their professions by updating their peace teaching methods. They play an important role in developing transferable skills in their students, such as debating, technology, problem-solving, information collection, interpersonal, communication, self-management, teamwork, and collaboration. They also have to be capable of removing the violence image in traditional textbooks, especially the one that strengthens local superiority (Kester, Citation2021). Moreover, they need to develop passion education to focus on maintaining a positive human relationship. Lecturers should welcome, encourage, and be patient in guiding students to get the idea of peace education concept.

Fourth, the peace education curriculum and teaching materials can be integrated through the so-called hidden curriculum by, for example, incorporating them to civic education course or religion study, especially regarding tolerance and moderation in religion by integrating the noble values of Pancasila with (Islamic) religious character values as reported by Purwanto (Citation2021). Meanwhile, reviewing the policies in two state universities in Ivory Coast and Kenya, Johnson (Citation2019) in his research reports that in addition to the policies to deal with local conflict and the solution to resolve it, universities can also build the capacity and infrastructure of peace education. Therefore, collaborative curriculum between several universities is integrated, then the similarities from respective universities are taken, thus an integrative curriculum in peace education is formed.

6. Conclusion

The review of this study shows that peace values can be developed in universities by encouraging them to play an active role in developing peace education. Universities can develop programs or learning to integrate peace values through building university partnerships, innovating peace-informed critical pedagogy, integrating peace education into curriculum, and considering peace education as a part of hidden curriculum. The synthesis of that literature shows that peace education practically can be developed in campuses and then disseminated to the surrounding community. In other words, the three important elements in the development of peace values are administration (curriculum, teaching materials), resources (universities, lecturers, students), and innovation (program, teaching strategies).

To support sustainability, peace education in universities needs to be regularly evaluated in terms of its administrative documents, resources participation, and the innovation made by the universities. Furthermore, universities can analyze the challenges to nurture peace sustainably by their leaders and all members of their academic society. The latter is important because peace education will only be successful if all of them, including students, are involved. This is because students will be agents of change in their community in the future. Having been equipped with peace values, they can put the constructive controversy methods into practice to deal with difficult situation. Students should also be provided with topics on serving as reliable peace mediator and information on civil values.

This research provides higher education policy and practical implications. From policy standpoint, universities can play a more active role in developing peace education for their students by considering partnerships and explicit and implicit integration of peace education into curriculum. To support this, the government is suggested to increase the budget for the implementation of peace education in campuses. Secondly, faculty members are responsible for peace education agency. They are encouraged to design and implement peace-based critical pedagogy which can help nurture students to develop their sense of peace agency. Additionally, they can be engaged in continuous professional development such as through peace education training.

While this systematic review offers new insights on how peace education is conceptualized and implemented in higher education settings, it has two main limitations. First, although Zakharia (Citation2016) formulated three distinct situations of peacebuilding—prior to violence, during conflict, and post-conflict—the articles included in the analysis did not specifically examine the integration of these situations into peace education practices. Thus, future systematic reviews are encouraged to conduct specific analyses regarding this matter. Secondly, the selected articles included multiple papers written by the same author or co-author, potentially causing selection bias. Therefore, a future systematic review on a related topic is worth further consideration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yedi Purwanto

Yedi Purwanto teaching Islamic Religious Education at the Bandung Institute of Technology. Doctoral degree at Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta. Specialization of expertise in the field of peace education, sociology of religion in relation to science, technology, and arts.

Suprapto

Suprapto is a researcher at the National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. Bachelor’s degree in Education Management at the IKIP Bandung in 1986 and Masters in Education Management at Jakarta State University in 2002.

Dicky R. Munaf

Dicky R. Munaf is Professor in Sociotechnology, teaching State Ideology at the Bandung Institute of Technology. Ph.D degree from University of Pittsburgh , USA in the field of Theoretical Mechanics and Post Doctoral from National Ressilience Institute in the field of National Politics and its Strategy.

Hasan Albana

Hasan Albana is a researcher at the Research Center for Education of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Organization of the National Research and Innovation Agency.

Notes

1. Bali bombing 1 was a bomb attack on the island of Bali on October 12, 2002 at Paddy’s Pub and Sari Club in the Kuta area and a bomb near the United States consulate in Denpasar. More than 299 people were killed foreigners and Indonesian citizens. Conducted by Jemaah Islamiyah which is linked to al Qaida. Bali Bombing 2, occurred on October 1, 2005 exploding simultaneously at Jimbaran Beach and Raja cafe in Kuta Bali. This attack was also carried out by Jemaah Islamiyah terrorists linked to al Qaida (Peristiwa Bom Bali 1 dan Bom Bali 2 | Muhammad Luffi Asyari Wahib (muhluffi.blogspot.com), accessed on 8 May, 2023.).

References

- Adelson, A. (2000). Globalization and university peace education. Peace Review, 12(1), 117–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/104026500113908

- Akkad, A., & Henderson, E. F. (2021). Exploring the role of HE teachers as change agents in the reconstruction of post-conflict Syria. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1965571

- Bajaj, M. (2015). ‘Pedagogies of resistance’ and critical peace education praxis. Journal of Peace Education, 12(2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2014.991914

- Bajaj, M., & Hantzopoulos, M. (2016). Theory, research, and praxis of peace education. In M. Bajaj & M. Hantzopoulus (Eds.), Peace education: International perspectives (pp. 1–16). Bloomsbury.

- Brantmeier, E. J., & Webb, D. (2020). Examining learning in the course, “inclusive leadership for sustainable peace”. Journal of Peace Education, 17(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2019.1669145

- Buckland, P. (2005). Reshaping the future: Education and postconflict reconstruction. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-5959-2

- Chelule, E. (2014). Impediments to implementation of peace education in public universities in Kenya. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 19(3), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-1932174185

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

- Gibson, W. J., & Brown, A. (2009). Working with qualitative data. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Hajir, B., & Kester, K. (2020). Toward a decolonial praxis in critical peace education: Postcolonial insights and pedagogic possibilities. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 39(5), 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-020-09707-y

- John, V. M. (2018). Teaching peace education at a South African university. Peace Review, 30(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2017.1419671

- Johnson, A. T. (2019). University infrastructures for peace in Africa: The transformative potential of higher education in conflict contexts. Journal of Transformative Education, 17(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344618779561

- Kartadinata, S., Affandi, I., Wahyudin, D., Ruyadi, Y., & Latifah, P. (2015). Pendidikan Perdamaian. Remaja Rosdakarya.

- Kester, K. (2013). Peace education: An impact assessment of a case study of UNESCO-APCEIU and the university for peace. Journal of Peace Education, 10(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2013.790252

- Kester, K. (2017). The United Nations, peace, and higher education: Pedagogic interventions in neoliberal times. Review of Education, Pedagogy, & Cultural Studies, 39(3), 235–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2017.1326273

- Kester, K. (2018). Reproducing peace? A CRT analysis of Whiteness in the curriculum and teaching at a university of the UN. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(2), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1476339

- Kester, K. (2019). Whiteness, patriarchy, and peacebuilding in UN higher education: Some theoretical and pedagogical implications from one case institution. Irish Educational Studies, 38(4), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1645722

- Kester, K. (2021). Toward a conflict-sensitive approach to higher education pedagogy: Lessons from Afghanistan and Somaliland. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.2015754

- Lehner, D. (2021). A poiesis of peace: Imagining, inventing & creating cultures of peace. The qualities of the artist for peace education. Journal of Peace Education, 18(2), 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2021.1927686

- Millican, J., Kasumagić-Kafedžić, L., Masabo, F., & Almanza, M. (2021). Pedagogies for peacebuilding in higher education: How and why should higher education institutions get involved in teaching for peace? International Review of Education, 67(5), 569–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-021-09907-9

- Milton, S. (2020). Higher education and sustainable development goal 16 in fragile and conflict-affected contexts. Higher Education, 81(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00617-z

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Altman, D., Antes, G., & Tugwell, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Oueijan, H. N. (2018). Educating for peace in higher education. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(9), 1916–1920. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.060909

- Purwanto, Y. (2021). Pendidikan Perdamaian: Integrasi Nilai-Nilai Karakter Agama dan Panccasila [peace education: Integration of Religious and pancasila character values]. ITB Press.

- Sahar, A., & Kaunert, C. (2021). Higher education as a catalyst of peacebuilding in violence and conflict-affected contexts: The case of Afghanistan. Peacebuilding, 9(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2020.1731123

- Sahfutra, S. A. (2012). Sensitivitas Konflik: Upaya Mendeteksi dan menguatkan positivisme Konflik [conflict sensitivity: Detecting and strengthening conflict positivism]. In M. N. Ichwan & A. Muttaqin (Eds.), Agama dan Perdamaian: Dari Potensi Menuju Aksi [religion and peace: From potential to action] (pp. 42–55). Program Studi Agama dan Filsafat, Program Pascasarjana, Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga.

- Sardi, M. (2012). Membangun Hidup Beragama yang Beradab Demi Damai yang Berkesinambungan [Building Civilized Religious Life for Sustainable Peace. In M. N. Ichwan & A. Muttaqin (Eds.), Agama dan Perdamaian: Dari Potensi Menuju Aksi [religion and peace: From potential to action] (pp. 3–26). Program Studi Agama dan Filsafat, Program Pascasarjana, Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga.

- Sayaee Development Organization. (2000). Peace education training manual for teacher. SDO.

- Shehi, R. Z., Ozcan, S., & Hagen, T. (2018). The role of higher education institutions in building a culture of peace: An Albanian case. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 13(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2018.1427136

- Smith, A., & Vaux, T. (2005). Education, conflict and international development. DFID.

- Zakharia, Z. (2016). Peace education and peacebuilding across the conflict continuum: Insights from Lebanon. In M. Bajaj & M. Hantzopoulos (Eds.), Peace education: International perspectives (pp. 71–87). Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474233675.ch-004

- Zembylas, M. (2018). Con-/divergences between postcolonial and critical peace education: Towards pedagogies of decolonization in peace education. Journal of Peace Education, 15(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2017.1412299