Abstract

Limited Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) knowledge among China’s youth is a considerable challenge that impacts not only China but also the global progression towards sustainable development goals. This study aims to offer a comprehensive understanding of China’s sex education policy, its evolution in recent years, and the role played by domestic and international actors in the policy-making process. A combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies were employed to investigate the current state and historical progression of China’s sex education policy. The findings reveal a significant correlation between the government’s emphasis on sex education and several key indicators, including the incidence of abortion, the level of gender equality, and the development of the education system. The study also identifies several roadblocks hampering the comprehensive development of sex education in China, and recommends the establishment of a dedicated cross-ministerial institution to enhance collaboration and guide the development of comprehensive sex education in China.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) education is vital for young people’s well-being. In China, there’s a growing awareness of its importance, but challenges remain. This study delves into China’s sex education policy, its evolution, and the role of both domestic and international stakeholders in shaping it. While progress has been made, there are obstacles such as cultural taboos and limited inter-agency collaboration in the Chinese government. We suggest creating a cross-ministerial body to streamline policy-making. This research not only sheds light on China’s journey but also contributes to the academic debate on comprehensive sex education at the global level.

1. Introduction

As one of the most populous countries, the sexual and reproductive health of the Chinese people is important to not only China but the global society. However, data show that 96% of young people in China have limited knowledge of SRH (X. Zheng & Chen, Citation2010). Good sexual and reproductive health is a state of “complete physical, mental and social well-being in all matters relating to the reproductive system” (UNFPA, Citation2022b), and sex education is critical to achieving the state. The knowledge of SRH helps individuals make informed decisions about their health, relationships, and family planning.

In China, the development and implementation of sex education policy have been a collaborative effort between various government bodies and social organizations. The Ministry of Education (MoE), National Health Commission (NHC), All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF), and China National Committee for the Care of Children (CNCCC) have been key actors in this process. They are, sometimes, out of step with each other, making the policy development process mysterious to the public.

Previous research has identified the sources from which Chinese adolescents receive sex‐related knowledge (L. Zhang et al., Citation2007, Li et al., Citation2017, Lyu et al., Citation2020), explored the relevance between AIDS and sex education (Gao et al., Citation2001, Burki, Citation2016), and examined the design of curriculum and textbooks related to sex education (Liang et al., Citation2017, Liang & Bowcher, Citation2019, Ji & Reiss, Citation2022). However, less attention has been paid to the policy-making process of sex education and the actors involved, and how sex-related social factors impact policy development and implementation.

Therefore, this article aims to understand the different actors in the policy-making process of sex education and their respective roles. This will contribute to identifying the barriers to effective implementation, propose strategies to overcome the obstacles, and, eventually, add to the scholarly debates on the development of China’s sex education in general.

This study employs a comprehensive literature review, policy analysis, and stakeholder analysis to understand the landscape of sex education in China. With both quantitative and qualitative methods, the article examines existing academic articles, government reports, policy documents, and the roles and interests of various stakeholders involved in the formulation and implementation of sex education policies.

This study finds the correlations between sex education policy development and a variety of social and political factors, including sex-related events, gender equality and the development of the education system. However, it is noted that public opinion has not been a significant influence on policy-making.

2. History of China’s sex education

The history of sex education in China is a complex and evolving narrative closely connected to the changes in politics, culture and ideologies in this country. This section is designed to provide an overview of the key developments and shifts in China’s sex education over the centuries, providing historical background for understanding the current situation.

The discourse around sex education in China can be traced back to the early 20th century, even before the establishment of the Republic of China (1912–1949). As many scholars argue, the debates on sex education were raised as part of the modernizing elite’s discourse on national vulnerabilities and their aspiration for modernization in the early Republican era.

Both Chinese and international scholars trace the beginnings of debates on sex education in China back to the early Republican era. These discussions, including the criticism towards Chinese sex culture and suggestions on promoting sex education in China, were seen as part of the modernizing elite’s discourse on national vulnerabilities and their aspiration for modernization (Lu, Citation1993, Dikötter, Citation1995, Zhu, Citation2001, Aresu, Citation2009, Hayhoe & Ross, Citation2013).

In 1922, the Chinese government introduced a new school system and sex education was included in the curriculum (Zhu, Citation2001). However, considering the low enrollment rate and literacy rate, most Chinese did not have access to elementary education, let alone sex education. The progress in sex education was also slow and often met with resistance due to deeply ingrained cultural norms and beliefs.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, sex education has become a controversial issue. On the one hand, Zhou Enlai, the premier of China, as well as many scholars in the field of education, strongly supported and advocated for sex education, considering sex education is important for the healthy development of boys and girls (Dalin, Citation1994). On the other hand, the social norm was that sexually oriented topics were for the married instead of school-aged youth (Fraser, Citation1977). During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), sexual repression was widespread, and emerging sexual education was suppressed, resulting in the spread of misconceptions about sexual development (Lin, Citation2011).

The Reform and Opening Up policy started in 1978 has made China more liberal in general, and the importance of sex education was further realized by government officials in the 1980s. Many books on sex education were published, and some relevant journals were started, making sex education a social issue (Bullough & Ruan, Citation1990). More teaching materials have been produced and more sex education projects have been initiated, which is effective in increasing the sexual knowledge of students in China (Gao et al., Citation2001). However, limited attention was paid to sex education in schools, and physiology, where sexuality knowledge is involved, is often taught as a minor part of general biology. One reason behind this might be the connection between sex education and family planning since the Family Planning Commission (now part of the NHC) is always a major policy-making agency at the national level.

Sexuality education was officially incorporated into the school curriculum in China in 1988, and it has evolved into a strategy that provides age-appropriate information and guidance on sexual health and prevention measures since then (Li et al., Citation2017). In the Population and Family Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China issued in 2002, it is clearly stated that “schools in a manner suited to the characteristics of the receivers and, in a planned way, conduct among pupils education in physiology and health, puberty or sexual health” (UNESCO Bangkok, Citation2012). Sex is still a word with “shame” for many students and even teachers in China. For example, “puberty education” (qingchunqi jiaoyu) is a more often used term rather than “sex education”. In a report published in 2019, some teachers stated that they would just skip “sensitive parts” of sexual knowledge which causes “extremely uncomfortable” (UNESCO & UNFPA, Citation2019).

To sum up, sex education in China has been largely developed after 1978, especially in the twenty-first century. Notwithstanding, sex education is still inadequate in China, and the effective delivery of sex education in China continues to face challenges due to cultural taboos and systemic barriers. The school implementation of sex education is neither comprehensive nor well-integrated (UNESCO & UNFPA, Citation2019), and this article argues that the puzzle-like policy-making process regarding sex education might be an important reason.

3. Materials and methods

This article uses a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods. The authors review news and articles related to the domestic and international actors in the policy-making process of China’s sex education, including the official websites of different ministries and international organizations.

This article first conducts a text analysis to explore the evolving emphasis on sex education as well as the different roles of various institutions. In particular, policy word frequency is used to measure the government’s emphasis on the policy of sex education. The authors retrieved 415 publicly available web pages issued by four major institutions (MoE, ACWF, NHC and CNCCC) engaged in sex education development and implementation within the timeline of January 2021 to May 2022. These are all web pages within the timeline containing four selected keywords, i.e., sex education (xingjiaoyu), sexual health (xingjiankang), reproductive health (shengzhijiankang) and sexual assault (xingqin). The web pages were collected if any keyword was detected in either title or body text to achieve full coverage of relative contents.

Based on the analysis of the role of different institutions in policy-making and implementation qualitatively, the authors further explore the potential influencing factors by selecting variables in four dimensions: sex-related events, gender equality, education system development, and public opinion. Due to the relatively strong endogeneity among the various dimensions, this article does not make causal inferences but conducts a correlation analysis. The article calculates the correlation coefficients between the frequency of sex education policy words and other indicators in the same year, which can reflect how the government institutions, including the MoE, ACWF, NHC and CNCCC, react to various factors, and correspondingly emphasize sex education policies.

The information on the policy variables and the main relevant factor variables are shown in Table . Firstly, physical health and safety are essential aspects of sex education policy, and the occurrence of incidents that jeopardize sexual and reproductive health is a potential factor that affects the implementation of sex education policy. Therefore, annual data on the number of criminal rape cases filed by public security authorities and the number of abortions in China were also selected for this article.

Table 1. Variable summary

Secondly, according to UNESCO’s International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education, in addition to bodily rights and health, sex education also includes gender equality aspects (UNESCO, Citation2022a). The authors assume that promoting gender equality is one of the purposes of sex education policies, while the overall level of gender equality in society may, in turn, influence the institutional viability of policy formulation and implementation. Considering the availability of long-term historical data, this article draws on the Gender Development Index (GDI), published by UNDP in 1995, which measures women’s development in education, economy, and health (UNDP, Citation2023). Because GDI does not count women’s participation in politics, this article also selects data on the percentage of women delegates to the National People’s Congress (NPC).

In addition, the MoE is a critical stakeholder in sex education. There might be a correlation between the development of sex education and general education to some extent, and the authors select high school and university enrollment to evaluate the general development of the education system.

Last but not least, although academia has not reached a consensus on whether public opinion can influence public policy, it is undeniable that it can be a relevant factor worth discussing (Burstein, Citation2003). Therefore, to probe whether sex education policies correlate with public opinion, this article refers to the Baidu Index by using sex education (i.e., xingjiaoyu), inappropriate behaviour (rape, sexual harassment and molestation, i.e., qiangjian, xingqin, xingsaorao) and accidents (abortion, i.e., renliu, rengongliuchan) as keywords.

The above data were obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, Health Statistical Yearbook, Education Development Statistical Bulletin, Baidu Index and UNDP. Most data are collected from 2001 to 2021, though there are missing values. The data of the Baidu Index are only collected from 2011 to 2021 due to the late launch of this product.

4. Actors in the policy-making of China’s Sex education

4.1. Domestic actors

The Chinese government did not explicitly use the term “sex education” in national laws and regulations until 2020. In 1988, a national governmental document was issued to demand basic guidance for teenagers’ mental health education (Notice of the CPC Central Committee on Reforming and Strengthening Moral Education in Primary and Secondary Schools, Citation1988), which included puberty education, a normal term used to avoid directly mentioning sex education. China has been continuously formulating and adopting laws and regulations to provide due education for age-appropriate targets since the 21st century. As a result, China has adopted over 30 policies concerning sex education, of which 20 are promulgated under the guidance of the State Council, and the remaining 16 are mainly formulated by ministries and commissions such as the MoE and the NHC.

Notwithstanding, sex education had not been directly referred to until 2020, when the Amendment to Law on the Protection of the Minors was put into enforcement. The Amendment stipulates that “schools and kindergartens shall carry out age-appropriate sex education for minors” (Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of the Minors, Citation2020), which is the very first legal document highlighting sex education. However, this Amendment, despite being a landmark, does not indicate that China has a unified sex education policy, as this amendment has no clear provisions on the main responsible or competent ministries.

As indicated in the Figure , the word frequency analysis results of China’s sex education policy show that the focus of China’s sex education policy can be roughly divided into two parts, physical health education and mental health education, of which ensuring physical health is a more important concern. Most policies and regulations contain words related to physical health, prevention and control of AIDS, reproductive health, family planning, pregnancy, and sexual health. Regarding mental health education, policies put more emphasis on communication between genders, gender awareness, puberty knowledge, adolescent psychological development, and healthy relationships. In addition, the prevention of sexual harassment and assault also appears more frequently in recent years and is increasingly adding further weight. Although the emphasis might be different from the international standards, China’s sex education policy comprehensively covers the key contents of comprehensive sex education defined in International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An evidence-informed approach (UNESCO, Citation2022b).

Figure 1. Word cloud of China’s sex education Policy.

The sex education policy is jointly formulated by MoE, NHC, ACWF and CNCCC at the central government level. A series of government bodies and social organizations led by these four core actors are responsible for the implementation of specific policies and projects. The priorities of each body vary in practical implementation.

The educational system mainly promotes the popularization and progress of sex education through school education. Given the fact that adolescents, the main target group receiving sex education, should receive compulsory education, MoE covers the most comprehensive sphere of content on sex education among four core actors to make better use of the broad coverage of China’s compulsory education.

Sex education in school has been implemented in various settings. For one thing, schools incorporate age-appropriate mental health education courses into school curricula nationwide to help students establish correct gender awareness and cognition of gender communication. For another, some modules of biology courses are introduced to impart knowledge related to reproductive health, sexual health, and AIDS prevention when students enter puberty, so that students can better understand and adapt to their own physiological changes during that period. In addition, preventing sexual assault has also become a hot spot in recent years, in view of the frequent news of some teachers using their positions for sexual harassment in recent years (China Woman, Citationn.d.). At the request of MoE, schools not only strengthen and improve their own working mechanism to prevent sexual assault and harassment, but also cooperate with judicial organs (Supreme People’s Court, Citationn.d.), supervision organs (Supreme People’s Procuratorate, Citationn.d.) and public security organs (Ministry of Public Security Authority, Citationn.d.) to protect students’ sexual safety.

However, topics related to sexuality, especially physiology and sexual intercourse, have always been a cultural taboo in China (Zha & Geng, Citation1992). Even in the 21st century, when an increasing number of people hold a more open attitude toward sex, some Chinese teachers continue to avoid mentioning this concept and are unwilling to take the initiative to help students understand relevant information (Cui et al., Citation2001).

Compared with the education system, the health system has a much smaller coverage of sex education. It mainly concentrates on the fields related to physical health within its functions. Family planning, the prevention and control of AIDS, and the popularization of reproductive and health knowledge are all important concerns of NHC. The importance of these concerns gradually changes over time.

At the beginning of the 21st century, under the guidance and requirement of family planning policy, the National Health and Family Planning Commission (the predecessor of NHC) incorporated sex education content related to reproductive health into school education and social lecture publicity, aiming to help people better understand the knowledge of sex and reproduction, and pursue scientific pregnancy preparation and contraception. With the continuous change in China’s population structure afterwards, family planning policy has also changed. Under this pretext, the contents of publicity and education related to family planning have gradually disappeared, but the knowledge of reproductive and sexual health remains in the curriculum, which has now become an important part of sex education policy.

After the priority shifted from family planning, the prevention and control of AIDS have taken the central status in gradual. Till now it is still the module that witnesses the deepest level of participation of NHC. Since the first case of AIDS was reported in China in 1985, the spread of AIDS in China has been sporadic. In addition to unsafe injections and blood transfusions, people’s insufficient sexual knowledge and unsafe sexual behaviour also accelerated the spread of AIDS (K. Zhang & Beck, Citation1999), making HIV infection a great threat to young people’s health in China (Grusky et al., Citation2002). Therefore, NHC has a strong motivation to promote the development of sex education, especially knowledge related to AIDS prevention and control. However, it is difficult for NHC to involve in the school education process, without cooperating with MoE. With the cooperation of NHC and MoE, relevant curriculum content for students has been added to understand AIDS and its effective prevention and control. Meanwhile, a tradition of AIDS Day, a flagship initiative of NHC, has been formed to deepen students’ impression of relevant knowledge and awareness of self-protection. In addition, NHC is also playing its role in social education and publicity—a role that MoE pays far less attention to.

Similarly, there is still room for improvement in the coverage, frequency, and penetration of social education. Besides, few grass-roots health institutions like health stations exert their strength and participate in similar activities, which failed to radiate sex education to a wider area and population.

Apart from the ministries, mass organizations at the central government level are also important forces in promoting the development of sex education, among which the ACWF and the CNCCC are the most outstanding ones. Within their respective mandates, i.e. protecting women’s rights and caring for adolescents’ healthy growth, they share similarities in facilitating sex education. These two mass organizations’ activities mainly adopt the channel of social education and family education. It is important to highlight that social education features cross-sectoral cooperation. For one thing, they cooperate with educational authorities to carry out lectures on puberty education and sex education knowledge, construct training courses for sex education instructors, and conduct various activities focusing on the growth of girls. For another, they collaborate with the public security, judicial and inspection authorities to carry out lectures on law to protect the rights and interests of girls and supervise schools. Both organizations at all levels have been trying to raise parents’ attention to and guide their participation in children’s sex education by shooting short videos, distributing brochures, inviting experts to answer questions, and holding competitions.

The most prominent characteristic of mass organizations in carrying out sex education activities lies in their mass nature, which allows them to have the widest coverage and the strongest sinking strength. Although school education has broad coverage, some economically underdeveloped and poverty-stricken areas find it hard to ensure compulsory education, let alone sex education courses that have not been attached with much importance. Against this background, these two organizations take the responsibility of visiting and publicizing relatively remote and less-developed areas, such as counties, villages and some ethnic autonomous, especially in the central and western regions of China and take the above as their main workplaces, according to a series of activities reported on the official website.

However, there are subtle differences between the two organizations in organizing sex education activities. The target audience of the ACWF is mainly female minors, while the other organization has no such difference. This slight difference also exposes the problems of ACWF in the process of sex education. To some extent, the excessive attention on girls puts boys in the situation of lacking enough awareness when facing actions that threaten their sexual safety. As for the CNCCC, the biggest problem lies in its inactivity in carrying out sex education activities as its main body is composed of retired high-ranking civil servants.

4.2. International actors

In addition to domestic governmental agencies, international organizations have also contributed to the agenda-setting and policy-making of China’s sex education. The mandates of some organizations cover sex education, making them actors in policy-making globally and in China. For example, the China Office of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) identifies promoting “life-skills based comprehensive sexuality education” as one of its strategies (UNFPA, Citation2022a). Other active actors include the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), UN Women, UNAIDS, UNICEF, United Nations Development Program (UNDP), International Labour Organization (WHO), World Bank, and World Health Organization (ILO). The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) also plays its role in promoting sex education worldwide, but it does not have a local office in Mainland, China.

Similar to domestic policymakers, the international actors can be divided into different categories, i.e., sexual and reproductive health, education, gender equality, and prevention of AIDS, by their respective mandates and areas of focus, as indicated in the Table . These agencies have been authorized to take their roles in promoting comprehensive sexuality education worldwide, and the China Offices thereof have long participated in the policy-making process since the 1980s. Some UN agencies with less connection with sexuality-related issues, e.g., the World Food Programme (WFP), also implemented sex education projects in China (He & Rehnstrom, Citation2005).

Table 2. Involved UN agencies and focus areas regarding sex Education

At the global level, the headquarters of these UN agencies set up international standards and guidelines, publish policy reports, and organize international conferences on relevant issues. The activities are likely to contribute to the norm diffusion of appropriate sex education. In 1994, the Programme of Action (PoA) of the International Conference on Population and Development was adopted, in which the importance of providing adolescents with sexuality-related “information and services” (UN Ed., Citation1995). In the following years, the PoA was revised and updated, and more attention was paid to sex education. However, scholars have found that there is a change in the language of comprehensive sexuality education in the UN resolutions from 2018, including the removal of “sexuality” to an increased emphasis on the role of families (Gilby et al., Citation2021), which might reflect the conservative shift in the norm diffusion. The international conferences held by UN agencies are usually participated by representatives of national governments, but also delegates from NGOs, academia and the media. The government representatives provide official authorization to the joint political decisions made by the international conferences, and the non-governmental actors might set the advocacy agenda and as pressure groups (Carpenter, Citation2007). Myriads of actors, both individuals and organizations, participated in many lobbying, standard-setting, monitoring of compliance with standards, and even shaming norm violators (Keck & Sikkink, Citation2014). The international norm might have created international pressure to which the Chinese government has to respond. However, there are only a few, if any, evidence-based empirical studies on the correlation between international pressure and China’s sex education policy-making. The data and sources are limited, and the Chinese government is strong enough to insist on its position on many issues without swaying under international pressure. In recent years, the Chinese government has been highly cautious of the spread of “Western values” (Qin et al., Citation2021), and sex education, especially when connected to human rights, e.g., LGBTI rights, could be sensitive for the officials. The Chinese delegation sent to these international conferences is usually combined with diplomats from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and professionals from competent ministries and agencies. They are responsible for sharing the opinions of the Chinese government and providing policy suggestions to the leadership on how to respond the international trend.

At the ministerial level, the China Offices of international organizations are the key communication channel between the headquarters thereof and the competent agencies in the Chinese government. By organizing policy dialogues and high-level meetings, international organizations try to influence the policy-making process of the Chinese government. The ministries and international organizations also jointly implemented nationwide programmes related to sexual and reproductive health (He & Rehnstrom, Citation2005). The ministries, which are mostly political-risk-averse peracetic institutions, are willing to follow the traditional cooperation channels but cautious about initiating unconventional new programmes. The establishment of new cooperation programmes relies on a political decision.

At the local government level, many projects have been conducted jointly by international organizations and local governments (UNFPA, Citation2021). The attitude of local governments toward cooperation with international organizations varies and the brand of the United Nations is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the international reputation makes it more convenient for any UN agencies to communicate with the local governments which are willing to cooperate with international organizations. On the other hand, some government officials are prudent and cautious of the potential political and diplomatic risks, so they tend to obtain direct and clear instructions from the upper-level government. Notwithstanding, the local governments are more flexible compared to the central ministries and many projects with regard to sex education promotion have been conducted or finished in a number of provinces in China.

The activities solely conducted by international organizations also directly impact society and academia. In 2009, the International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education was issued by UNESCO, providing more detailed approaches for schools, teachers and health educators (UNESCO, Citation2009). Involving numerous scholars and experts, a series of international guidelines and standards regarding sex education has created an environment where transnational processes are growing continuously (Cross, Citation2013). In this regard, an epistemic community, which is “a network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue area” (Haas, Citation1992), has been deeply involved in the policy-making process in many countries, and China is not an exception. Even more, academia in China is one of the most progressive groups in promoting sex education. In recent years, many scholars suggest that sex education should be emphasised at all levels of school, some of them, as deputy to the National People’s Congress or member of the China People’s Political Consultative Conference, has officially submitted their motions or proposals regarding promotion of sex education in China (Xiao, Citation2022). Notwithstanding, there is a gap between academia and the public, which is sometimes more conservative. Discourses have long targeted foreigners and “immoral” Chinese women as vectors and transmitters of AIDS and other sexual diseases (T. Zheng, Citation2009), ignoring the importance of sex education in the prevention and control of sexual diseases.

Many international and domestic non-governmental organizations have been involved in the process. Some of these NGOs act as partners of international organizations and/or domestic agencies at the working level, indirectly participating in the policy-making process at a lower level. Marie Stopes International, as one of those, has developed the You & Me sexuality education platform, providing material and technical support to educators to conduct sexuality education (UNESCO, Citation2021). However, due to a lack of meaningful engagement between the government and NGOs (Hasmath & Hsu, Citation2014), the operation of NGOs, especially those foreign-funded, might be comparatively limited in China.

5. Analysis of relevant factors in policy-making

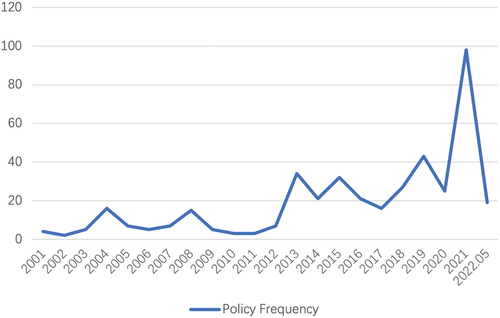

From 2001 to May 2022, the word frequency trend of sex education policies on relevant government websites is shown in Figure . The overall trend is rising, indicating that the Chinese government is gradually increasing the importance of sex education policies. However, compared with the policies mentioned above, there is no significant consistency between the trend of change in importance and the time of policy introduction. This suggests that the government’s emphasis is influenced by various factors. In this section, we explore the possible factors from the perspective of sex-related incidents, gender equality, education system development, and public opinion.

Figure 2. Word frequency trend of China’s sex education policy.

The results of the correlation analysis are shown in Table . Sex-related incidents are significantly correlated with the emphasis on sex education policies. With the coefficient being 0.654, it indicates that the occurrence of abortion is strongly associated with sex education policy, and family planning and physical health can be attached with great importance by the government institutions. As for rape, the coefficient is −0.380, negative and relatively low. However, it does not necessarily demonstrate the government does not concern about security. One possible explanation is that sexual assault and rape have been attached of great importance in recent years as analyzed in the previous section, while this may not have been the case in the early stages of policy development. In addition, sex education policy could also contribute to preventing gender-based violence including rape through sexual and reproductive health education by promoting healthy relations, consent, and respect for boundaries (Senn et al., Citation2011, World Health Organization, Citation2009).

Table 3. Correlation between the policy-making of sex education and other factors

The two indicators of gender equality, both the GDI and the percentage of female delegates to the NPC, are significantly and strongly correlated with policy word frequency. As shown in Table , the correlation coefficient of GDI is 0.620, and the coefficient of female political participation is 0.687. It implies that the government of a society with a higher level of gender equality may have fewer barriers and stronger motivations to put forward policies promoting gender equality. Women’s political participation and representation have also proven to be a greater impetus for government investment in education and healthcare policies and to favor women-friendly laws, especially in developing countries (Clots-Figueras, Citation2012, Kittilson, Citation2008, Bhalotra & Clots-Figueras, Citation2014). In China, Agencies like the ACWF, aiming at safeguarding female rights, may play a significant role in implementing sex education policies.

In addition, the coefficients of educational system development are 0.749 and 0.496 for universities and high schools respectively, also significantly positive and relatively high. Such results manifest that the efforts and accomplishments of MoE are highly relevant to the advancement of sex education policies. The development of the education system in China, especially the higher education system, also contributes to more investment in sex education policy-making.

As for public opinion, this article cannot significantly prove that public opinion and sex education policy can influence each other. As shown in Table , the correlation coefficients between the sex education policy and levels of public attention on sex education, sex-related inappropriate behaviours and sex-related incidents are not positive nor significant. The results are consistent with the existing literature. While public opinion can be a powerful force in shaping policy outcomes, the relationship between the two is complex and often mediated by a range of other factors, including interest groups, political institutions, and media coverage. The responsiveness of public policy to public opinion can be low and problematic (Zaller & R, Citation1992).

Despite the limited data source, the results of the correlation analysis echo the findings of the qualitative analysis, and are enlightening for future work to delve into and draw a robust conclusion on whether the sex education policy is primarily affected by public opinion in China.

6. Conclusion

Over the past decades, China’s sex education policy has been continuously evolving and become more complex. In general, the policy focuses more on physical health education, but also takes into account the content of mental health education. This paper utilizes quantitative and qualitative methods to analyze the evolution of China’s sex education policy, highlighting the roles of various domestic and international actors in the policy-making process.

Multiple domestic and foreign actors play a role in China’s sex-related policy-making. MoE covers the most comprehensive domain content through school education. NHC has a narrower coverage and focuses mainly on physical health. ACWF and CNCCC use social education and family education channels and have the widest coverage and the strongest sinking strength. In addition, international actors including various international organizations can to some extent influence the policy-making process in China, jointly implement programs and influence society and academia from different levels.

Our key findings reveal a significant correlation between the development of China’s sex education policies and certain factors including the occurrence of sex-related public events, the degree of gender equality, women’s political participation, and the development level of the education system. Notably, public opinion has shown less influence on sex education policy-making.

The findings from the correlation analysis significantly complement our examination of the roles played by different actors in sex education policy-making. The correlation analysis underscores the prominent role physical health plays in each actor’s policy focus, evidenced by the high correlation coefficient between policy development and sex-related events. Gender equality, a focal point for international organizations, also shows a clear influence on policy development. As the degree of gender equality and women’s political participation increase, policy agenda setting, formulation, and implementation undergo notable changes. This is also reflected in the amplified voice of the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF) in the policy-making process. As for the education system development, MoE implements sex education policies mainly through school education. Therefore, the development of mass education also relates to the advancement of sex education.

However, public opinion appears to have a limited impact on actors’ responses in policy-making, suggesting a potential area for increased consideration in future policy development processes. We must also acknowledge the limitations present in this study. Although our objective was to identify the factors influencing sex education policy-making, issues of reverse causation among these factors may complicate interpretations of the findings.

In summary, the international society has witnessed the development of China’s sex education in recent years—more policies have been initiated, more teaching materials have been developed, and more social attention has been raised. Both domestic and international actors have positively promoted the development of sex education policy, along with cooperation at different levels. With the occurrences of sex-related social incidents, as well as the improvement of gender equality and the education system, related actors have paid more attention to the contents of sex education and influenced policy-making.

However, there are still many challenges obstructing the development of comprehensive sexuality education in China. First, the four central government institutions involved in policy-making tend to operate within their own mandates, which limits collaboration within the public sector. Second, sexuality is traditionally considered shameful and embarrassing, which makes sex education unwelcome for many parents in China, causing difficulties in promoting sex education in local communities. Third, although the contents of sex education in China are becoming gradually comprehensive, different contents have not received equal attention in the implementation, especially the lack of attention to sexuality-related mental health education and education for boys. Fourth, the conservative shift in the norm diffusion globally might reduce the degree of shared perspective and consensus. This might also negatively impact the effectiveness of international actors’ programme implementation.

In light of these findings and challenges, we recommend the establishment of a cross-ministerial division to foster collaboration among different institutions and manage the overall policy development of sex education. Also, active participation from all actors across sectors is critical for the sustainable development of comprehensive sexuality education.

Overall, we have seen remarkable progress in China’s sex education policies and its recognition both domestically and internationally. This research provides insights into the current status and potential future of sex education policy-making in China, contributing to the global dialogue on comprehensive sexuality education.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, Q.Q.; methodology, Z.J.; formal analysis, Z.J.; investigation, Q.Q.; writing, Q.Q., Z.J.; project administration, Q.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend our gratitude to Wang Jing from Wuhan University for providing technical expertise in crawler programming. Our appreciation also goes to Xianxian Lin and Ceshu Gao for their invaluable assistance in information gathering. Administrative support was graciously provided by Lao Meir and Xiaotong Jiao. We sincerely thank everyone mentioned for their contributions. Additionally, we are grateful to other individuals and organizations that offered support for this research, including the journal editor and the two anonymous reviewers who provided valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Qian Qin

Qian Qin is a Casual Academic at UNSW Sydney. He is a member of Australian Political Studies Association. Qian’s research interests cover International Relations, UN System, International Law, SDG and Development Studies. He previously worked for different agencies within the UN System where he gained practical expertise in global governance. Jiali Zhang is a Yenching Scholar at Peking University, focused on China studies, economics and manage management track. Her research interests cover education economics and international development.

References

- Aresu, A. (2009). Sex education in modern and contemporary China: Interrupted debates across the last century. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(5), 532–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.04.010

- Bhalotra, S., & Clots-Figueras, I. (2014). Health and the political agency of women. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(2), 164–197. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.6.2.164

- Bullough, V. L., & Ruan, F.-F. (1990). Sex education in Mainland China. Health Education, 21(2), 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00970050.1990.10616184

- Burki, T. (2016). Sex education in China leaves young vulnerable to infection. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00494-6

- Burstein, P. (2003). The impact of public opinion on public policy: A review and an agenda. Political Research Quarterly, 56(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290305600103

- Carpenter, R. C. (2007). Setting the advocacy agenda: Theorizing issue emergence and nonemergence in transnational advocacy networks. International Studies Quarterly, 51(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00441.x

- China Woman. (n.d.). Building a “Protection network” for Minors Under the Guidance of Party Building. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://www.women.org.cn/art/2022/1/10/art_20_168005.html

- Clots-Figueras, I. (2012). Are female leaders good for education? Evidence from India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(1), 212–244. Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.4.1.212

- Cross, M. K. D. (2013). Rethinking epistemic communities twenty years later. Review of International Studies, 39(1), 137–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210512000034

- Cui, N., Li, M., & Gao, E. (2001). Views of Chinese parents on the provision of contraception to unmarried youth. Reproductive Health Matters, 9(17), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(01)90017-5

- Dalin, L. (1994). The development of sex education in China. Chinese Sociology & Anthropology, 27(2), 10–36. https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA0009-4625270210

- Dikötter, F. (1995). Sex, culture, and modernity in China: Medical science and the construction of sexual identities in the early Republican period. University of Hawaii Press.

- Fraser, S. E. (1977). Family planning and sex education: The Chinese approach. Comparative Education Review, 13(1), 15–28.

- Gao, Y., Lu, Z. Z., Shi, R., Sun, X. Y., & Cai, Y. (2001). AIDS and sex education for young people in China. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 13(8), 729. https://doi.org/10.1071/RD01082

- Gilby, L., Koivusalo, M., & Atkins, S. (2021). Global health without sexual and reproductive health and rights? Analysis of United Nations documents and country statements, 2014–2019. BMJ Global Health, 6(3), e004659. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004659

- Grusky, O., Liu, H., & Johnston, M. (2002). HIV/AIDS in China: 1990–2001. AIDS and Behavior, 6(4), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021109031521

- Haas, P. M. (1992). Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International Organization, 46(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300001442

- Hasmath, R., & Hsu, J. Y. J. (2014). Isomorphic pressures, epistemic communities and state–NGO collaboration in China*. The China Quarterly, 220, 936–954. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741014001155

- Hayhoe, R., & Ross, H. (2013). Education in China: Educational History, Models, and Initiatives (1st ed.). Berkshire. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1j0pszw

- He, J. L., & Rehnstrom, J. (2005). United Nations system efforts to support the response to AIDS in China. Cell Research, 15(11–12), 908–913. Article 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290367

- Ji, Y., & Reiss, M. J. (2022). Cherish lives? Progress and compromise in sexuality education textbooks produced in contemporary China. Sex Education, 22(4), 496–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2021.1955670

- Keck, M. E., & Sikkink, K. (2014). Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. In Activists beyond borders. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801471292

- Kittilson, M. C. (2008). Representing women: The adoption of family leave in comparative perspective. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238160808033X

- Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of the Minors, (2020). https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail2.html?ZmY4MDgwODE3NTI2NWRkNDAxNzUzZmI5YzQ1ODEyN2I%3D

- Liang, J. Y., & Bowcher, W. L. (2019). Legitimating sex education through children’s picture books in China. Sex Education, 19(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1530104

- Liang, J. Y., Tan, S., & O’Halloran, K. (2017). Representing sexuality and morality in sex education picture books in contemporary China. Social Semiotics, 27(1), 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2016.1161117

- Li, C., Cheng, Z., Wu, T., Liang, X., Gaoshan, J., Li, L., Hong, P., & Tang, K. (2017). The relationships of school-based sexuality education, sexual knowledge and sexual behaviors—A study of 18,000 Chinese college students. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0368-4

- Lin, S. (2011). Xing Jiaoyu 60 Nian: Zai Mengmei yu Ganga zhong mosuo [60 years of sex education: Exploring through ignorance and embarrassment]. Nanfang Renwu Zhoukan, (29). https://news.sina.cn/sa/2011-08-26/detail-ikftssap4044450.d.html

- Lu, Y. (1993). Qingmo Minzhu Woguo Xuexiao Xingjiaoyu Shulue[Sex education in the late qing dynasty and early Republic of China]. Chinese Journal of Medical History, 23(1), 6–11.

- Lyu, J., Shen, X., & Hesketh, T. (2020). Sexual knowledge, attitudes and behaviours among undergraduate students in China—implications for sex education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6716. Article 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186716

- Ministry of Public Security Authority. (n.d.). The Public Security Organ Appoints the Vice President of the Rule of Law to Assist in the Work Related to Campus Security and the Next Step. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/fbh/live/2022/53969/sfcl/202202/t20220217_599925.html

- Notice of the CPC Central Committee on Reforming and Strengthening Moral Education in Primary and Secondary Schools, (1988). https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E4%B8%AD%E5%85%B1%E4%B8%AD%E5%A4%AE%E5%85%B3%E4%BA%8E%E6%94%B9%E9%9D%A9%E5%92%8C%E5%8A%A0%E5%BC%BA%E4%B8%AD%E5%B0%8F%E5%AD%A6%E5%BE%B7%E8%82%B2%E5%B7%A5%E4%BD%9C%E7%9A%84%E9%80%9A%E7%9F%A5/56669442?fr=aladdin

- Qin, Q., Li, Z., & Jiao, X. (2021). Public opinion on the death penalty in Mainland China and Taiwan. China Report, 57(3), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/00094455211023909

- Senn, C. Y., Gee, S. S., & Thake, J. (2011). Emancipatory sexuality education and sexual assault resistance: Does the former enhance the latter? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310384101

- Supreme People’s Court. (n.d.). More Than 13000 Judges Have Served as Vice Principals of the Rule of Law in Primary and Secondary Schools. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/fbh/live/2022/53969/mtbd/202202/t20220217_600136.html

- Supreme People’s Procuratorate. (n.d.). Assist the School to Establish and Improve the Working Mechanism to Prevent Sexual Assault and Harassment. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/fbh/live/2022/53969/mtbd/202202/t20220217_600169.html

- UNDP. (2023). Human development reports. United Nations Development Programme. https://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137906

- UN (Ed.). (1995). Report of the international Conference on Population and development: Cairo, 5-13 September 1994. United Nations.

- UNESCO. (2009). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach for schools, teachers and health educators. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183281

- UNESCO. (2021). The journey towards comprehensive sexuality education: Global status report. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377963

- UNESCO. (2022a). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach for schools, teachers and health educators. //Lst-Iiep.Iiep-Unesco.Org/Cgi-Bin/Wwwi32.Exe/[In=epidoc1.in]/?T2000=028198/(100).

- UNESCO. (2022b). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach for schools, teachers and health educators. //Lst-Iiep.Iiep-Unesco.Org/Cgi-Bin/Wwwi32.Exe/[In=epidoc1.in]/?T2000=028198/(100).

- UNESCO Bangkok. (2012). Sexuality education in Asia and the pacific: Review of policies and strategies to implement and scale up. UNESCO. https://healtheducationresources.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/Resized_Review_policies_in_AP.pdf

- UNESCO & UNFPA. (2019). Implementation of sexuality education in middle schools in China. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367530

- UNFPA. (2021). Ensuring Rights and Choices for All: Practices of UNFPA China Livestreaming Comprehensive Sexuality Education Project in Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan Provinces. https://china.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/livestreaming_comprehensive_sexuality_education_project-web_0.pdf

- UNFPA. (2022a). Sexual & reproductive health. United Nations Population Fund. https://www.unfpa.org/sexual-reproductive-health

- UNFPA. (2022b). UNFPA - What We Do. https://china.unfpa.org/en/topics/adolescents-and-youth-5

- World Health Organization. (2009). Promoting Gender Equality to Prevent Violence Against Women. 16. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44098

- Xiao, W. (2022, March 16). Kaifa Xingjiaoyu Kecheng, Juban Duozhong Huodong [develop sex education courses, conduct different types of activities]. Haikou Ribao, 11.

- Zaller, J. R., & R, Z. J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press.

- Zha, B., & Geng, W. (1992). Sexuality in Urban China. The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, 28, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/2950053

- Zhang, K., & Beck, E. J. (1999). Changing sexual attitudes and behaviour in China: Implications for the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Aids Care-Psychological & Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/hiv, 11(5), 581–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540129947730

- Zhang, L., Li, X., & Shah, I. H. (2007). Where do Chinese adolescents obtain knowledge of sex? Implications for sex education in China. Health Education, 107(4), 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280710759269

- Zheng, T. (2009). Nationalism and women in the discourse of HIV/AIDS in China. In T. Zheng (Ed.), Ethnographies of prostitution in Contemporary China: Gender relations, HIV/AIDS, and Nationalism (pp. 55–76). Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230623262_3

- Zheng, X., & Chen, G. (2010). Survey of youth access to reproductive health in China. Population and Development, 16(3), 2–16. http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-SCRK201003001.htm

- Zhu, M. (2001). Sex education in China in the Early 20th Century. Journal of Nanjing University (Philosophy, Humanities and Social Sciences), 38(1), 149–154.