Abstract

Advancements and developments in technologies have compelled open distance learning (ODL) institutions to evolve through several stages of technological development. In some institutions, the COVID-19 accelerated these stages, and as a result, many educators across the globe are adopting and exploring various digital technologies and tools as student support mechanisms. Arguably, as teaching practices evolve due to these technological advancements and emergency teaching and learning modes; and, as new teaching models replace old ones, a “cultural change” is bound to occur. Thus, there is keenness among scholars to understand the effects of these new cultures in shaping student support in ODL environments. Using a theoretical lens derived from cultural anthropology, within the constructivist paradigm, the researchers sought to understand the extent to which lecturers’ technological and pedagogical practices within an ODL university reflect technological cultural shifts as required by the new culture at their institution. The findings indicated small and realistic strides in the adoption of various technologies to support postgraduate students as well as the development of 21 century skills.

1. Introduction

Technology in open distance learning (ODL) is as old as the practice itself, because ODL is technologically mediated. Advancements and developments in world technologies have compelled ODL universities to evolve through several stages of technological development. Earlier studies (Taylor, Citation2001) had identified five stages and later studies three (Anderson & Dron, Citation2011; Garrison, Citation2006), namely; (1) print media and postal correspondence; (2) audio/video; and (3) digital interactive technologies. Observations indicate that many ODL universities are at the digitisation stage, and this includes the University of South Africa (UNISA), one of the oldest ODL universities in the world. The University has evolved through several stages, having started as an examination centre (Tait, Citation2008) in Cape Town, in 1873, and in 1946 became one of the first universities to offer education through the distance learning mode, which involved print media and postal correspondence. Unlike the Open University UK (OU UK), which developed its tutor system as early as 1971, and computer-mediated conferencing in 1989 (Tait, Citation2014), UNISA’s integrated tutoring system was pioneered in 2013. The model comprised face-to-face and e-learning (tutoring) support for some undergraduate students. It was during this period that the University adopted its learning management system (LMS) technology, thus evolving into digitisation. This introduced a virtual platform for student-lecturer interactions to supplement the print media and postal correspondence delivery mode. This was a “huge cultural change” (Tait, Citation2014) that was going to affect student support mechanisms, learning, teaching and assessment. A 2014 study (Chimbo & Tekere, Citation2014) exploring UNISA’s academic staff’s level of readiness to migrate to e-learning reported that the majority of the respondents had indicated their readiness. The study also indicated that 50% of the academic staff was aware of digital technologies, however, there were very low levels of personal usage of technology. A similar study conducted five years later, (Nsamba, Citation2019) reported low rates of technology adoption and very low levels of technology use for teaching and learning, which included low levels of the LMS usage.

Further research was needed to understand how lecturers in the postgraduate programmes use the LMS and leverage other digital technologies such as social networks, email, and videos to teach and support their students, hence this study. The researchers were also curious to know whether such technologies encourage the development of 21 century skills (Agrusti et al., Citation2008). These are skills required in the Bachelor of Honours degree programme, one of the most popular postgraduate programmes at UNISA.

The Bachelor of Honours degree is a postgraduate specialisation qualification on the South Africa’s National Qualification Framework (NQF), awarded at level 8 NQF. The programme comprises coursework and research, therefore, demands not only a high level of theoretical engagement but also intellectual independence (Council of Higher Education, Citation2013). As in most postgraduate qualifications, students are expected to write an acceptable proposal and produce a research report. This requires considerable support because students struggle in this programme (Kevunja, Citation2016; Maor & Currie, Citation2017). Concerns raised in a study investigating the quality of support in one of Honours programmes in a South African ODL university (Van Antwerpen, Citation2015) indicated that communication, feedback, and research guidance support was inadequate. This finding corroborated our observation that support for Honours students is inadequate, echoing concerns raised over the years about the inadequacy of student support in ODL (Bbuye, Citation2006; de Oliveira et al., Citation2018; Makoe & Nsamba, Citation2019; Simpson, Citation2013). Inadequate support such as minimal student-lecturer interaction in ODL has often been associated with poor student performance.

In South Africa as in many higher education institutions, poor performance in a proposal module may mean failure to enrol into a masters or doctoral degree programme or into higher degrees research programmes (Kevunja, Citation2016). From policy perspective, this is undesirable in South Africa because the country believes that for it to achieve its developmental goals, knowledge production must increase; and universities have been affirmed as dominant knowledge producers (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2020). In pursuance of this goal, the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030 Strategy (Citation2011) increased the PHD graduate output per year from 35% to 75% by 2030. Secondly, the National Planning Commission (Citation2011) proposed that the higher education sector should produce more than 100 doctoral graduates per million of the population per year (Cloete, Citation2014). Currently, the numbers of doctoral graduates in South Africa are lower than those in other BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) and some other African countries (Department of Higher Education & Training, Citation2020).

Therefore, the importance of the diffusion of digital technologies in ODL cannot be overemphasised as it minimises the inherent communication gap between students and lecturers. Arguably, as teaching practices evolve due to these technological advancements and emergency teaching and learning modes; and, as new teaching models replace old ones, a “cultural change” or shift is bound to occur. A cultural shift is defined as a change in ideas, norms, and behaviours of people, over time (Varnum & Grossmann, Citation2017). This shift, which is present in all societies involved in technological experiences, requires new articulations and readjustment (Combi, Citation2016) of teaching and learning. These new articulations include instructional designs that recognise the acquisition and mastery of knowledge and skills relevant to the 21st Century contexts such as: Critical thinking, communication, collaboration, creativity, innovation, problem-solving and technological skills (Partnership for 21st Century Skills, Citation2007). In addition, the use of technology to support meaningful learning requires educators’ knowledge of pedagogical and technological methods (Koehler et al., Citation2014). It is in this context that this paper was conceptualised.

Using a theoretical lens derived from cultural anthropology, within the constructivist paradigm, the researchers sought to examine and understand the extent to which lecturers’ technological and pedagogical practices within an ODL university reflect technological cultural shifts as required by the new culture at their institution in enhancing postgraduate student support. In addition, to determine whether their broadened practices offer the students opportunities beyond the Bachelor of Honours Degree. Our thinking is summarised in these three questions:

What cultural shifts are evident in lecturers’ choice of technologies to support their students?

To what extent does the cultural shift reflect the use of new concepts and the development of new understandings?

To what extent do lecturers’ practices reflect knowledge sharing and innovative ideas?

This paper flows from an ODL research support project (ODL RSP), (Ref #2019_RSP_10) whose aim was to examine strategies and technologies lecturers use to support their Honours students. Permission to conduct the research was granted by Research Permission Subcommittee (RPSC) of the UNISA Senate, Research, Innovation, Postgraduate Commercialisation Committee. The present study focused on the College of Science, Engineering and Technology (CSET), which comprises three schools, two of which offer Honours programmes. It builds onto recent research (Nsamba, Citation2019) exploring the maturity levels of e-learning tools and strategies in an ODL institution. In addition, it illuminates further insights into the use of various technologies to support students in ODL.

2. Understanding technology and cultural change in teaching and learning: an anthropological perspective

Over the years, researchers have relied on anthropology lens to study culture. Generally, variants of anthropology are applied to examine people’s belief systems, practices, experiences and behaviours. Anthropologists’ topics of interest throughout the years have included studies on ethnographies of scientists, engineering education, reproductive and medical technologies, gender and science, ethics and values, and science (Escobar, Citation1995). Lately, scholars have proposed a new paradigm that not only reflects on the interdisciplinarity of culture, but also on cultural shifts. This latest direction, referred to as cultural anthropology (Chen et al., Citation2018; Combi, Citation2016; Escobar, Citation1995; Minkov, Citation2013) is concerned with the understanding of innovative ideas (Chen et al., Citation2018; Tierney & Lanford, Citation2016) knowledge sharing (Chen et al., Citation2018) and new digital technologies (Combi, Citation2016; Escobar, Citation1995). According to Combi (Citation2016, 5), cultural anthropology seeks to understand how an individual learns to become a member of a society and how activities shape the process of learning. This perspective has led to deeper understandings of the definition and conceptualisation of culture.

The definitions of culture have been discussed and debated by scholars from a variety of disciplines, for years. Minkosh (Citation2013), who argued that such debates were pointless, propounded that culture “can be pragmatically defined by the contents and boundaries of the interests of scholars who study it” (p.11). The identification of these boundaries and contents is critical in helping with the understanding of the meaning of culture (Peterson & Spencer, Citation1990) especially in higher education. We considered this line of thinking while constructing this study’s conceptual framework. In this framework, we argue that an educational institution that is experiencing cultural shifting should consider the following as the desired contents and boundaries: The institutional culture; knowledge sharing and innovation, as well as the use of new digital technologies.

Most current discussions on institutional culture start from the epistemological requirement that organisational environment of higher education is “socially constructed” (Tierney & Lanford, Citation2019). Viewing organisations from a social construction perspective presupposes that members of those organisations have strong bonds which help them engage in conversations as they construct their activities (Geldenhuys, Citation2015). The idea of social construction of culture is consistent with Ferrare and Hora’s (Citation2014) view that academia culture is mostly viewed as a unitary set of beliefs, values and practices ascribed to disciplines. These are key elements that should be understood during cultural change (Schein, Citation2004) because they directly impact people’s behaviours, which in turn, influence knowledge creation and sharing behaviours (Park et al., Citation2017).

Knowledge sharing behaviour cuts across all organisations (Liao & Wu, Citation2009), and in our observation, this culture is encouraged across different fields and professions such as online communities, project teams, social networking platforms, learning institutions and among professionals. Whilst authors like Staadt (Citation2015) found organizational culture to be the most prominent enabler in enhancing the knowledge sharing culture, others (De Long & Fahey, Citation2000) have found it to be a barrier to knowledge sharing.

Looking further, Hendriks (Citation2004) has indicated that knowledge sharing emphasises two types of roles in an organisation: The role of “bringing” as in teaching people new skills; and the role of receiving knowledge or learning. Krumova and Milanezi (Citation2014) refer to these roles as pull and push behaviour. The former occurs when a scholar actively consults knowledge sources, such as libraries, experts or colleagues; and the latter is when knowledge is “pushed onto” the user (p.51). Huang et al. (Citation2008) noted that people build good relationships through knowledge sharing. Other views are that knowledge sharing is reciprocal (Hersberger et al., Citation2004); eases competitions among students (Majid & Chitra, Citation2013); promotes a culture of sharing and collaborations (Opeke & Opele, Citation2014) as well as knowledge distribution and social exchange (Wittel, Citation2011).

Research is not silent on who knowledge sharers are. A startling discovery found in a 2016 review on knowledge sharing (Sergeeva & Andreeva, Citation2016) indicates that knowledge sharers are mostly employees (in different industries other than education), followed by managers and students. Opeke and Opele (Citation2014) had also found that Nigerian postgraduate students were knowledge sharers. Among the employee sharers were scientists and technicians, and surprisingly educators were not on the list of knowledge sharers. A more recent review (Al-Kurdi et al., Citation2018) revealed a similar finding that HE educators have tendencies of hoarding knowledge. Earlier studies (Huang et al., Citation2008; Li & Scullion, Citation2006) had found that generally, people across different spectra are unwilling to share knowledge, but hoard it. Bilginoğlua (Citation2018) defines knowledge hoarding as a “deliberate and strategic concealment of knowledge” (p. 62) by individuals who use their power and control to block knowledge exchange. In HE this behaviour, however, contradicts the notion of knowledge generation and dissemination (Al-Kurdi et al., Citation2018). In our observation, knowledge generation and sharing have been somehow promoted by research dissemination activities, as well as the OER and open access movements that advocate the free use of educational works. Nonetheless, there is limited research on knowledge sharing in HE, especially, cultural factors of knowledge sharing in developing countries (Al-Kurdi et al., Citation2018). This finding corroborates an earlier study (Majid & Chitra, Citation2013).

The third boundary that should be considered is innovation. Due to its differing conceptions by sociologists, psychologists, economists, policy makers and researchers, there is no consensus on the definition of innovation (Tierney & Lanford, Citation2016). In our observation and understanding, the term is mostly viewed as a process of generating and implementing new ideas. As early as 1950’s, innovation was defined as any new- coming behaviours and thoughts (Barnett, Citation1953).

Similarities have been drawn between innovation and knowledge sharing in the literature. Castaneda and Cuellar (Citation2020) who found that innovation was dependent on knowledge sharing, assert that this relationship can contribute to the design of services, products, processes, new models and schemes. These authors further noted that an organization whose culture encourages knowledge sharing facilitates innovation capabilities. This means that where organisational culture is an enabler of knowledge sharing, there is likelihood for innovation; and less likelihood of innovation if the organisational culture is a barrier to knowledge sharing. Zhu’s (Citation2015)) study examining the relationship between organisational culture and teachers’ responses to technology-enhanced innovations in Chinese universities found that features of organisational culture such as shared vision are associated with teachers’ responsiveness to innovation. Generally, in education, innovative ideas include those that can improve learning quality, such as new teaching approaches and techniques, tools, and pedagogic theories (Serdyukov, Citation2017).

The final consideration for the contents of our boundary is technology use in teaching and learning. Researchers (Al-Kurdi et al., Citation2018; Salloum et al., Citation2018) have found that information technologies play a significant role in facilitating knowledge sharing and innovation. In our consideration, the most appropriate theoretical lens through which to better understand technological cultural shifts and the role of technology in facilitating knowledge sharing is Combi’s (Citation2016) cultural anthropology framework. This model does not only promote innovative ways in using technologies in education, but also advances the teaching of the 21 Century skills. The model characterises technological cultural shifts as having the following features:

The instant circulation of information

The uninterrupted 24-hour link with people all over the world

Creativity and imagination

Circulation of ideas

Powerful and smaller instruments

Availability of many to many communications

Real time, reciprocal, interactive and non-stop computer communication (Combi, Citation2016, p.11).

This framework places great emphasis on prompt communication and doing “things that were not possible before” (Combi, p.11). Therefore, the role of the teacher remains critical in shaping learning experiences and ensuring that things are done differently for the attainment of learning outcomes (Garrison et al., Citation2001),

3. Methods

3.1. Data collection

Qualitative data were collected from 31 lecturers within the School of Science (6 participants) and School of Computing (25 participants) who were purposively sampled after informed consent. Sequential sampling involving two stages of sampling and data collection and analysis was used. The initial stage involved collecting data from all the participants who were teaching the Honours module. After analysing the data, a group of seven participants who could provide some thick description of their experiences in integrating technology into their teaching was purposively sampled. They were interviewed face-to face and audio recorded. The process of data collection lasted one week. During the interview process, bracketing was applied as a precautionary principle to suspend the researcher’s knowledge and experiences of the use of technology at the University. This increased the rigor (Mitchell, Citation2014; Tufford & Newman, Citation2012), and the credibility of the findings.

3.2. Data analysis

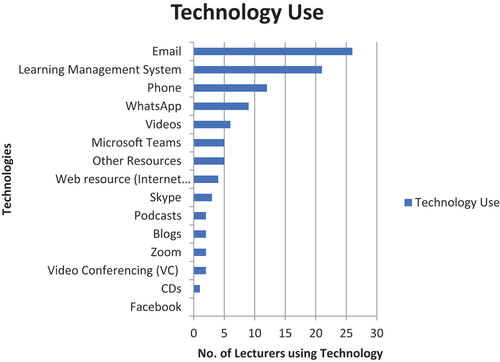

Two data analytical processes were employed. The first was content analysis to identify and quantify different technologies and other resources used by the lecturers (Figure ). In the second process, Thematic Analysis was used to organise data into codes and themes or labels. After repeatedly listening to the audio recordings, and re-reading the interview texts, the two researchers transcribed and coded the words associated with cultural shifts using line by line in vivo coding (Saldaña, Citation2009).

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. What cultural shifts are evident in lecturers’ choice of technologies to support their students?

The data revealed a wide range of technology adoption to support the postgraduate students, which is indicative of technological cultural changes. The chosen technologies had features that enable collaborations, creativity, circulation of ideas, knowledge sharing, as well as many to many and real time and reciprocal communications (Combi, Citation2016). These tools not only depict a cultural change but are also consistent with models that theorise online learning (Garrison et al., Citation2004; Siemens, Citation2005); and this is critical in ODL environments.

Figure indicates that all the participants in the study use more than one form of technology to communicate to their students. The most utilised tool was email, followed by the LMS and phone, and the least utilised tools were podcasts, blogs, WhatsApp, Skype, Video Conferencing (VC), Zoom, Microsoft Teams; Samigo and CDs. Surprisingly, none of the participants indicated the use of Facebook despite its popularity and reported pedagogical benefits (Giannikas, Citation2020; Mbati & Minnaar, Citation2015). Facebook is said to have approximately 2.4 billion active users across the globe. The reluctance in using Facebook for educational purposes is corroborated by Nsamba (Citation2019) and Mbati and Minnaar (Citation2015). Unsurprisingly, one participant indicated that he uses CDs in his teaching. The CDs are said to be beneficial to students who live in areas without bandwidth or do not have enough data bundles.

A further analysis of the data revealed various ways to use technologies in teaching and learning. 6 participants out of 31 said they use videos (YouTube links) to support students in different ways. One participant with approximately 150 students indicated that she prepares an introductory video to the proposal module each year and uploads it to the University LMS platform. To supplement the introductory videos, YouTube video links are sourced and uploaded on the LMS. Other participants reiterated that video recorded lessons are a great substitute for face-to-face instructions, and that the videos can be used as many times as possible. The effectiveness of videos in supporting learning is corroborated by other researchers (Boateng et al., Citation2016; Brame, Citation2016; Calandra & Rich, Citation2014). Furthermore, a third of the participants indicated that Skype, Zoom, Microsoft Teams and WhatsApp were useful and effective learning support tools.

Notwithstanding, it should be emphasised however, that, the level of utilisation of digital tools to support students is still minimal. For example, only two participants indicated that they hold conference meetings on Skype or Zoom with their students and another two indicated their use of video conferencing (VC). The VC technological support has been available at the University for years. Other resources (utilised by only five participants) include, WinEdt, Dropboxes for sharing material with students. Nonetheless, further research should be able to establish how technology is utilised in the post COVID-19 era. As has been alluded in earlier research (Nsamba, Citation2019) more lecturers should adopt interactive technologies to support their students and supplement the LMS.

4.2. To what extent does the cultural shift reflect the use of new concepts and the development of new understandings?

Given that our participants were Computer Science lecturers, we had hoped that they would help us understand how they “negotiate meaning and cultural understanding” (Kern, Citation2006,198) during their interactions with the students and the technologies. The purpose therefore was to explore the adoption of some technological concepts and words within the postgraduate programme. Communities in the digital environments use words and concepts such as: Screen sharing, upload, download, collaborative spaces, online assessment, Megabytes, teleconferencing, Web 2.0, Apps, social media etc, when describing their environments. Such concepts indicate that one has been “socialised” into the online community’s discourse (Kern, Citation2006, p.199). The concepts coded in our data included “Uploading on the LMS” whereby lecturers upload activities and information on the University’s Learning Management System; “Web links” and “Web page”, which are provided to the students for further reading; and “teleconferencing”, “webinars”, which are virtual interaction platforms. Other concepts emerging were “screen sharing” for interactive teaching and learning and “video games”, which suggested the emergence of a culture of gamification in the Honours programmes. Another compelling concept to emerge was “real time”. One of the participants, mentioned that the use of digital tools such as WhatsApp communication and feedback to the students, should be in “real time”. She emphasised:

“Information should be received now … You want them to get information now.”

We can deduce that the use of real time technologies guarantees timely feedback and feedforward for students’ learning. While the data depicted a minimal usage of real-time technologies in teaching, there is a glimmer of hope in the future improvements of support provision at postgraduate level. In other words, the lecturers are beginning to change their perspectives on how to approach teaching and learning in ODL and the learner will move from marginal participation to central participation (Odo et al., Citation2017) because the use of new technologies is a learning curve.

4.3. To what extent do lecturers’ practices reflect knowledge sharing and innovative ideas?

To answer the question on knowledge sharing and innovative ideas, the researchers coded all the themes related to “circulation of ideas and knowledge” (Combi, Citation2016). This theme is consistent with methods of teaching and learning, particularly in virtual environments. Data revealed different sharing behaviour patterns. The first behaviour was the “pull” and “push” (Krumova & Milanezi, Citation2014) which involves the act of sourcing material and sharing with the users. This behaviour was displayed by participants with more than 15 years in the ODL space. They indicated that they usually source You-Tube videos relevant to their module topics and “push” them onto their students. The “push” role is one of the most effective support methods in ODL as it enhances knowledge and skills acquisition. Another push sharing behaviour pattern revealed in the data indicated that participants with less than 11 years in ODL were more inclined to video-recording their own lessons and pushing them onto their students. This is consistent with the role of “bringing” whereby new skills and knowledge are brought to the users, who play the role of receiving knowledge and learning (Krumova & Milanezi, Citation2014).

Another knowledge sharing behaviour found in the data was collaborative learning and teaching. In ODL environments, collaborative lecturer-student and student-student experiences include projects, online discussion forums and presentations. Data indicated that the participants integrate collaborative activities into their instructional designs and use the strategy to discuss components of a research proposal, answer student questions, provide pointers and debate issues on individual students’ projects. One participant emphasised that the focus of the lecturers is not only to “get student pass” but also to provide the students with the skills and assets that will allow them to be mature and responsible members of the society. This is a valuable strategy that teaches students engagements and networking skills in preparation for future Masters and PhD programmes. Additionally, the participants emphasised that group discussions were more beneficial than teaching individual students (as is the case in ODL). Thus, integrating activities into the teaching strategies makes learning interactive and engaging (Majid & Chitra, Citation2013).

Further analysis revealed another pattern of sharing behaviour using information sharing technologies such as VC, Zoom, Teams and Skype. The participants indicated that they prefer these technologies because they enable real-time discussions and make lessons more interactive. The technologies are used to discuss feedback on the proposal writing. One lecturer who encourages knowledge screen sharing noted that Zoom was beneficial during discussions and that he discovered that,

“screen-sharing is one of the best ways to encourage student collaborations in a remote learning context, allowing students and us to share their work and other valuable content with the rest of the class”.

As noted by Zhu (Citation2015), shared vision within teaching and learning organisations promotes teachers’ responsiveness to technology-enhanced innovations, thus leading to new designs (Castaneda & Cuellar, Citation2020). This corroborated our data which revealed that one of the participants encourages the students to create their own videos as part of the portfolio assessment. These creations are always preceded by the lecturer’s demonstrations. This assessment strategy in the postgraduate modules indicates that the University policies are open to innovative ideas.

Regarding knowledge sharing among lecturers, data showed inadequate peer support at modular level, inadequate orientation opportunities to address lecturers’ expectations on ODeL approaches and non-existent communities of practice and networks. The issue of non-existent lecturer support at the College level was raised by three participants. Although the majority of the lecturers indicated that there was lecturer support in the form of workshops, the likelihood that such support is not focused to the needs of individual lecturers is high. Similar to student support, lecturer support should be context-specific and geared towards the needs of the individual lecturers. Such support can be provided by members of communities of practice through discussions on new technologies (Johnson et al., Citation2016). One participant expressed the importance of sharing ODeL postgraduate teaching and learning approaches to support those who are not conversant with ODL:

“Should we give them (students) everything or, expect them to have some expertise of learning on their own. You do not want to teach them like undergraduate students. Do we give them information? Should we expect them to look for information on their own?”

Furthermore, regarding hoarding, the data did not conclusively indicate any hoarding behaviour among the participants. It is well documented that different departments at this University organise formal sessions for sharing knowledge and innovative ideas and these have been in the increase since the COVID-19 pandemic. Examples are research seminars and conferences where academics showcase their projects and innovative work.

5. Implications and recommendations

Throughout history change has always been known as a process of transitioning to new goals and values within different formations of societies. This work attempts to look for new meanings for proposal teaching in ODeL institutions going through transition as we attempt to answer the question: Are there new cultures emerging through the use of new technologies in supporting postgraduate students?

Culture starts within societies. Fundamentally, the culture of technology adoption by lecturers is a large part of this transition because technology plays multiple roles: Mediating learning and teaching, promoting innovative behaviour, encouraging creativity and imagination, enhancing knowledge expansion and sharing, and mediating non-stop communication among ODeL players. The adoption of WhatsApp, videos, video conferencing tools, web links, podcasts and blogs as teaching tools and resources indicates the shift towards the new culture of teaching and learning. These are networking technologies that allow instant delivery of information. This means that ODeL postgraduate students engaging on proposal and research report writing can realise improved teaching quality and successful outcomes because of the following benefits: Non-stop communication with lecturers and peers, collaborations and knowledge sharing, receiving timely feedback and opportunities for innovations (creativity). In addition, the shift indicates the lecturers’ new understandings of teaching beliefs and assumptions as shaped by the digital era.

Another cultural shift in the lecturer’s use of words and concepts such as: Screen sharing, uploading and downloading study material, LMS; web links and web pages, teleconferencing, webinars, screen sharing, video games and gamification, and real time. These words describe activities that take place on computers and other technological devices. Knowing these words indicates that virtual players have been socialised into discourses used on virtual spaces, and it is important that students know these concepts.

Robust technology cultural shift such as the one existing in CSET, provides building blocks for sub-cultures like knowledge sharing and innovative behaviour. For example, some lecturers leverage technologies to teach their students new skills such as designing videos. Another important knowledge sharing culture involves sharing resource links to help students access learning material from libraries and Internet databases.

On the basis of the above implications, the following recommendations should be considered to maximise postgraduate students support using technologies. First, training and professional development on pedagogical and technological knowledge and skills should be a priority for all lecturers involved in postgraduate research development. Second, all lecturers involved in research development should be encouraged to adopt multiple tools and technologies to support their postgraduate students’ learning and increase interaction. Third, the adoption of teaching and learning technologies should consider students’ technology preferences during this transition time. For example, technology should enable them to obtain what they want “rapidly” and “pleasantly”. Fourth, there is need to establish communities of practice for peer support as this will encourage knowledge sharing and development. As indicated, technological cultural shifts are characterised by collaborations and circulation of ideas. Lastly, policy makers and managers have the duty to promote cultural changes that include the understanding of 21-century students’ skills, knowledge sharing among staff and students, and the establishment of communities of practice.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agrusti, F., Keegan, D., Kismihok, G., Krämer, B. J., & Mileva, N. (2008). Eds. The impact of technologies on distance learning students. FernUniversität.

- Al-Kurdi, O., El-Haddadeh, R., & Eldabi, T. (2018). Knowledge sharing in higher education institutions: A systematic review. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 31(2), 226–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-09-2017-0129

- Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2011). Three generations of distance education pedagogy. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 12(3), 80–97. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v12i3.890

- Barnett, H. G. (1953). Innovation: The basis of cultural change. McGraw-Hill.

- Bbuye, J. (2006). Towards developing a framework for support services for universities in Uganda. Retrieved from http://pcf4.dec.uwi.edu/viewpaper.php?id=52&print=1.

- Bilginoğlua, E. (2018). Knowledge hoarding: A literature review. Management Science Letters, 9, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2018.10.015

- Boateng, R., Boateng, S. L. R. B., & Ansong, E. (2016). Videos in learning in higher education: Assessing perceptions and attitudes of students at the University of Ghana. Smart Learning Environments, 3(8). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-016-0031-5

- Brame, C. J. (2016). Effective educational videos: Principles and guidelines for maximising student learning from video content. CBE - Life Sciences Education, 15(6), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125

- Calandra, B., & Rich, P. J. (Eds.). (2014). Digital video for teacher education: Research and practice (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315871714

- Castaneda, D. I., & Cuellar, S. (2020). Knowledge sharing and innovation: A systematic review. Knowledge Process Management, 27(3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1637

- Chen, L., Lee, M. Y., & Wu, J. (2018). Analysis of higher education and management model based on cognitive anthropology. Cognitive Systems Research, 52, 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2018.08.017

- Chimbo, B., & Tekere, M. (2014). A survey of the knowledge, use and adoption of emerging technologies by academics in an Open distance learning environment. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 10(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v10i1.26

- Cloete, N. (2014). Nurturing doctoral growth: Towards the NDP’s 5000? South African Journal of Science, 111(11/12), 3. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2015/a0127

- Combi, M. (2016). Cultures and technology: An analysis of some of the changes in progress - digital, global and local culture. In K. Borowiecki, N. Forbes, & A. Fresa (Eds.), Cultural heritage in a changing world (pp. 3–15). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29544-2_1

- Council of Higher Education. (2013). The Higher Education Qualification Framework. Council of Higher Education. Retrieved from www.che.ac.za.

- De Long, D. W., & Fahey, L. (2000). Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management. Academy of Management Executive, 14(4), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.2000.3979820

- de Oliveira, P. R., Oesterreich, S. A., & de Almeida, V. L. (2018). School dropout in graduate distance education: Evidence from a study in the interior of Brazil. Educ Pesqui, São Paulo, 44, e165786. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634201708165786

- Department of Higher Education & Training. (2020). Are we producing enough doctoral graduates in our universities?. Government Printers. https://www.dhet.gov.za/Planning%20Monitoring%20and%

- Escobar, A. (1995). Anthropology and the future: New technologies and the reinvention of culture. Futures, 27(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-3287(95)00013-M

- Ferrare, J., & Hora, M. T. (2014). Cultural models of teaching and learning in math and Science: Exploring the intersections of culture, cognition, and pedagogical situations. Journal of Higher Education, 85(6), 792–825. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2014.0030

- Garrison, D. R. (2006). Online collaboration principles. Online Learning, 10(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v10i1.1768

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640109527071

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2004). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7–23.

- Geldenhuys, D. J. (2015). Social constructionism and relational practices as a paradigm for organisational psychology in the South African context. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 41(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v41i1.1225

- Giannikas, C. (2020). Facebook in tertiary education: The impact of social media in eLearning. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.17.1.3

- Hendriks, P. (2004). Assessing the role of culture in knowledge sharing. Proceedings of 5th European Conference on Organizational Knowledge, Learning, and Capabilities (OKLC), Innsbruck, Austria. 1–24.

- Hersberger, J., Rioux, K. S., & Cruitt, R. O., (2004). Information sharing and community building in an internet-based community. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science annual meeting, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 41, 620–626.

- Huang, Q., Davison, R., & Gu, J. (2008). Impact of personal and cultural factors on knowledge sharing in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25, 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-008-9095-2

- Johnson, A. M., Jacovina, M. E., Russell, D. E., & Soto, C. M. (2016). Challenges and solutions when using technologies in the classroom. In S. A. Crossley & D. S. McNamara (Eds.), Adaptive educational technologies for literacy instruction (pp. 13–29). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315647500-2

- Kern, R. (2006). Perspectives on technology in learning and teaching languages. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 183–210. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264516

- Kevunja, D. (2016). How to write an effective research proposal for higher degree research in higher education: Lessons from practice. International Journal of Higher Education, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v5n2p163

- Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., Kereluik, K., Shin, T. S., & Graham, C. R. (2014). The technological pedagogical content knowledge framework. In J. Spector, M. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_9

- Krumova, M. Y., & Milanezi, B. D. (2014). Knowledge sharing and collaboration 2.0. KSI Transactions on Knowledge Society, 4(4), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4227827

- Liao, S. H., & Wu, C. C. (2009). The relationship among knowledge management, organisational learning, and organisational performance. International Journal of Business & Management, 4(4), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v4n4p64

- Li, S., & Scullion, H. (2006). Bridging the distance: Managing cross-border knowledge holders. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Springer, 23(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-006-6116-x

- Majid, S., & Chitra, P. (2013). Role of knowledge sharing in the learning process. Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal, 2(1), 1201–1207. https://doi.org/10.20533/licej.2040.2589.2013.0171

- Makoe, M., & Nsamba, A. (2019). The gap between student perceptions and expectations of quality support services at the University of South Africa. The American Journal of Distance Education, 33(11), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2019.1583028

- Maor, D., & Currie, J. K. (2017). The use of technology in postgraduate supervision pedagogy in two Australian universities. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0046-1

- Mbati, L., & Minnaar, A. (2015). Guidelines towards the facilitation of interactive online learning programmes in higher education. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 16(2), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i2.2019

- Minkov, M. (2013). The concept of culture. In cross-cultural analysis: The science and art of comparing the world’s modern societies and their cultures. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384719.n2

- Minkov, M. (2013). Cross-cultural analysis: The science and art of comparing the world’s modern societies and their cultures. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/978148338471

- Mitchell, P. H. (2014). Global education for collaborative practice. International Nursing Review, 61(2), 157–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12108

- National Planning Commission. (2011). National development plan 2030: Our future make it work. Government Printers. https://www.nationalplanningcommission.org.za/assets/Documents/ndp-2030-our-future-make-it-work.pdf

- Nsamba, A. (2019). Maturity levels of student support e- services within an open distance e-learning university. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 20(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i4.4113

- Odo, D. M., Pace, C., & Albers, P. (2017). Socialization through (online) design: Moving into online critical spaces of learning. Education, 23(1), 41–65.

- Opeke, O. R., & Opele, J. K. (2014). Assessment of knowledge sharing behaviours of postgraduate students in selected Nigerian universities. Information and Knowledge Management, 4(11), 102–106. .

- Park, J., Chae, H., & Choi, J. N. (2017). The need for status as a hidden motive of knowledge-sharing behaviour: An application of costly signalling theory. Human Performance, 30(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2016.1263636

- Partnership for 21st Century Skills. (2007). Framework for 21st century Learning. http://www.p21.org/documents/P21_Framework_Definitions.pdf.

- Peterson, M. W., & Spencer, M. G. (1990). Understanding academic culture and climate. New Direction for Institutional Research, 17(68), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.37019906803

- Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Salloum, S. A., Mhamdi, C., Al-Kurdi, B. H., & Shaalan, K. F. (2018). Factors affecting the adoption and meaningful use of social media: A structural equation modeling approach. International Journal of Information Technology and Language Studies (IJITLS), 2(3), 96–109. http://journals.sfu.ca/ijitls

- Schein, E. H. (2004). Organisational culture and leadership (3rd Ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Serdyukov, P. (2017). Innovation in education: What works, what doesn’t, and what to do about it? Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 10(1), 4–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-10-2016-0007

- Sergeeva, S., & Andreeva, T. (2016). Knowledge sharing research: Bringing context back in. Journal of Management Inquiry, 25(3), 240–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492615618271

- Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for a digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning. http://www.itdl.org/journal/jan_05/article01.htm

- Simpson, O. (2013). Student retention in distance education: Are we failing our students? Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 28(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2013.847363

- Staadt, J. (2015). The cultural analysis of soft systems methodology and the configuration model of organizational culture. Sage Open, 5(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015589787

- Tait, A. (2008). What are open universities for? Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 23(2), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680510802051871

- Tait, A. (2014). From place to virtual space: Reconfiguring student support for distance and e-learning in the digital age. Open Praxis, 6(1), 5–16. ISSN 2304-070X. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.6.1.102

- Taylor, J. (2001). Fifth generation distance education (report no. 40). E-Journal of Instructional Science & Technology, 4(1), 1–14. Retrieved from. http://eprints.usq.edu.au/136/

- Tierney, W. G., & Lanford, M. (2016). Conceptualizing innovation in higher education. In Conceptualizing innovation in higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26829-3_1

- Tufford, L., & Newman, P. (2012). Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice, 11(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325010368316

- Van Antwerpen, S. (2015). The quality of teaching and learning of BCom honours degree students at an open distance learning university in South Africa. Africa Education Review, 12(4), 680–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2015.1112159

- Varnum, M. E. W., & Grossmann, I. (2017). Cultural change: The how and the why. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 956–972. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617699971

- Wittel, A. (2011). Qualities of sharing and their transformations in the digital age. The International Review of Information Ethics, 15(9), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.29173/irie218

- Zhu, C. (2015). Organisational culture and technology-enhanced innovation in higher education. Technology, Pedagogy & Education, 24(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2013.822414