Abstract

The present study investigated the current status of Chinese pre-service English language teachers’ Technological Language Learning and Teaching (TLLT) competence in a 16-week PjBL-based course. As well as receiving instruction, the participants completed four group projects relating to MOOC, micro-lectures, games, and social media. The pre-service English language teachers were required to finish a reflection journal after each group project and to complete the survey again at the end of the course. They reported that their TLLT competence, including technological knowledge (TK), technological content knowledge (TCK) and technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK), significantly improved. Their reflection journals show they preferred social media and online shared document platforms to accomplish their group projects. Most technological tools and platforms that they applied in their projects were taught in the course. Besides, they believed this PjBL-based course could enhance their English language skills, including listening, reading, speaking, writing, grammar and translation skills. Regarding the implementation of technologies in teaching, the pre-service English language teachers mentioned various technological platforms and tools at different teaching stages. It is our expectation that this study could offer theoretical, methodological and pedagogical insights into pre-service language teachers’ professional development.

1. Introduction

Digital technologies have been integrated into different fields, including education, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Iivari et al., Citation2020). In language education, various technologies have been implemented in classroom settings and verified as effective tools in classroom practice. For example, these include social media (Reinhardt, Citation2019), computer-mediated communication (Golonka et al., Citation2014), augmented reality (Liu et al., Citation2016), and mobile learning (Chen, Citation2018). However, as technology integration in education is highly complex (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006), pre-service language teachers must enhance their technological language learning and teaching (TLLT) competence by developing and integrating their instructional, content and technological knowledge (Golonka et al., Citation2014; Hong, Citation2010; Jones, Citation2001; Liu & Kleinsasser, Citation2015; Tseng & Yeh, Citation2019; Yang & Wu, Citation2012).

Pre-service teachers refer to student teachers enrolled in a teacher education program and working toward teacher certification (Chand et al., Citation2022). Many struggle to integrate technologies into their teaching, although numerous teacher training activities, including conferences and workshops, have been held to enhance their technological competencies (Wang et al., Citation2004). The difficulties pre-service teachers encounter mainly arise because such training activities prioritise delivering content and using instructional strategies rather than helping them understand how to apply different technologies (Chao, Citation2015; Hong, Citation2010). Debski (Citation2006) and McNeil (Citation2013) argued that an effective teacher training programme should allow teachers to combine content activities and technology tools for different teaching purposes. Therefore, these prospective teachers must be equipped with pedagogical and content knowledge and technology-related knowledge, which are all necessary for their professional development.

Theoretically, Mishra and Koehler’s (Citation2006) Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework has been widely applied in technology-based teaching practices and teacher training activities to enhance teachers’ technological competence (Agyei & Voogt, Citation2012; Chai et al., Citation2012; Habibi et al., Citation2020; Liu & Kleinsasser, Citation2015; Valtonen et al., Citation2019). However, very few practices have been conducted to help pre-service language teachers comprehensively develop their technological, pedagogical and content knowledge to solve real-world problems and collaborate with others. Therefore, this study draws on the TPACK framework and applies the well-recognised project-based learning (PjBL) approach to help teachers develop this competence via practice and problem-solving processes. The main aim of this study is to investigate the current status and development of Chinese pre-service English teachers’ TLLT competence by taking an English education major course (i.e., Multimedia and Foreign Language Teaching) as an example. The study aims to offer insights into research and practices relating to pre-service language teachers’ professional development. The two main research questions are: (1) What is the current status of Chinese pre-service language teachers’ TLLT competence? (2) How does their TLLT competence develop via the Multimedia and Foreign Language Teaching course?

2. The TPACK framework

2.1. Overview of TPACK framework and conceptualisation of TLLT competence

Theoretically, this study draws on the TPACK framework that Punya Mishra and Matthew J. Koehler proposed in 2006. TPACK was developed to effectively integrate technology into educational activities (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006; Schmidt et al., Citation2009). The framework predominantly focuses on three main constructs, including Content Knowledge (CK), Pedagogical Knowledge (PK) and Technological Knowledge (TK), as well as three triangulated areas called Technological Pedagogical knowledge (TPK), Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) and Technological Content Knowledge (TCK). More specifically, TK refers to knowledge of technology tools but is not limited to the ability to operate various technologies. It includes knowledge of choosing appropriate technologies to complete tasks in various contexts. TCK refers to knowledge of the subject matter represented with technology. Finally, TPK relates to knowledge of using technology to implement teaching methods. The TPACK framework acknowledges that teachers act within complex spaces and serves as a theoretical guide for teachers to implement educational technologies in their classrooms (Figure ).

Figure 1. The TPACK framework (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006).

Tseng and Yeh’s (Citation2019) study proposed and sought to foster EFL teachers’ computer-assisted language learning (CALL) competence based on the TPACK framework. However, despite their rich results, they did not clearly conceptualise “CALL competence”. Furthermore, while they took every construct (TK, CK, PK, TPK, TCK, PCK) into consideration, some constructs, like CK, PK and PCK, are not closely relevant to CALL or technology. Besides, CALL predominantly focuses on language learning rather than language teaching from a conceptual perspective. Therefore, we have changed the term “CALL competence” to “TLLT competence”, which underscores technology-enhanced language teaching and learning. In the present study, TLLT competence refers to a series of abilities that require TK, TCK and TPK as included in the TPACK framework.

2.1.1. Empirical studies on TPACK

Regarding the application of TPACK in L2 education, Tseng (Citation2018) conducted a case study to examine how a Taiwanese English instructor improved L2 interaction and how her students responded to this type of instruction in a computer classroom. In her study, several data collection approaches were applied, and various technologies were implemented. Specifically, a questionnaire survey and focus-group interviews were used to gather information about students’ opinions, lesson plans and classroom observations and interviews were used to gather information about the teacher’s knowledge of TPACK-SLA. The results indicate that interactive classes can help students to boost their learner-computer engagement and interpersonal communication skills. However, it should be emphasised that the results of this study were limited to a computer classroom where each student had access to an individual computer were available. This is an issue as this type of specialised classroom is typically not as simply and conveniently accessible to EFL teachers compared to computer science teachers. Moreover, because only one Taiwanese junior high school English teacher’s TPACK was investigated, the generalisability of the study results is limited and should be improved in future studies.

Mainly concentrating on pre-service language teachers, Cheng (Citation2017) conducted a survey to examine Taiwanese language teachers’ perceptions of TPACK. The survey contained seven constructs, including CK, PK, TK, TPK, TCK, PCK and TPACK. Results show that the investigated teachers had relatively low confidence in TK and TPK, and they identified the significance of improving TK and TCK. These findings showcase the necessity of improving pre-service language teachers’ TLLT competence.

Tai (Citation2015) investigated the effects of a CALL teacher education workshop based on a TPACK-in-Action model. This model promotes a learning-by-doing methodology to understand how English instructors acquire technological competence in their teaching. As a mixed-method study, both quantitative and qualitative data (i.e., surveys, observations, interviews and reflections) were collected. According to the results, the TPACK-in-Action workshops benefitted the 24 participant teachers. It was noted their TLLT competence developed significantly in their teaching, including choosing online resources and the proper techniques for teaching content, utilising cloud computing for student interaction, and implementing the affordances of technology to meet their instructional goals. This study offers insights into how workshops can be implemented to develop pre-service teachers’ technological competence. However, few studies have focused on the benefits of project-based courses, and more attention should be paid to pre-service English teachers in other regions like mainland China.

3. PjBL and TLLT competence

Inspired by constructivist learning theory, project-based learning (PjBL) is an authentic and student-driven instructional approach that aims to engage students by connecting their learning to real-world issues and practical problem-solving. PjBL centres on a project that integrates multiple skills into various complex tasks, such as planning, gathering and discussing information, problem-solving, and report-writing (Hedge, Citation1993).

According to Stoller and Myers (Citation2019), learners should firstly determine the project’s theme and topics, concluding objectives, and a progression strategy. They gather information through diverse methods, including reading, internet searches, questionnaires, and interviews. Then, learners are guided through the information processing procedure by means of scaffolded instruction before sharing their projects with their instructors and peers to obtain feedback, comments, or grades. Finally, learners are required to reflect on what they have learned from the project through discussion, journal entries, or mediation to identify future project development strengths and weaknesses.

In language education, PjBL is used to equip students with critical thinking skills to enable them to independently and collaboratively complete the tasks required to solve complex problems (Fried-Booth, Citation2002). It allows teachers to develop technological competencies and teaching experiences to collaboratively discuss and solve teaching problems (Lin & Hsieh, Citation2001).

Numerous benefits of PjBL for L2 and foreign language learners have been recognised, including improving language skills, enriching content learning, acquiring practical skills and enhancing learning motivation (Grant, Citation2017; Stoller & Myers, Citation2019). Regarding teachers’ development in CALL competence, Liu and Kleinsasser’s (Citation2015) study investigated how six vocational high school EFL instructors developed TLLT competence during a one-year technology-enhanced professional development programme in which they designed two WebQuest projects. The teachers learned about the theory and design of project-based instruction, as well as how to conduct a WebQuest using the Moodle platform. Self-report data, via surveys and interviews, were collected from the teachers. Five of the six teachers increased their TPK, TCK and TPACK scores reported in the survey after receiving CALL training courses.

The goal of Tseng and Yeh’s (Citation2019) study (mentioned in Section 2) was to increase the CALL competence of EFL teachers through an 18-week PjBL project. In total, 12 EFL teachers participated in exercises, including group discussions, class observations, and lesson plan creation. Surveys on TPACK were given to the teachers, and qualitative data (e.g., lesson plans, reflection essays, and class observation notes) were also collected. The survey results revealed that the prospective teachers’ CALL competence increased after completing the PjBL project. The interviews focused on the benefits that these prospective teachers obtained and the problems they encountered when participating in the PjBL project. This study provides insights into the development of pre-service language teachers’ TLLT competence. However, as the study was conducted in Taiwan, more attention could be focused on prospective teachers in mainland China, where few relevant studies could be found. Therefore, in light of the limitations of the existing research, in the present study, the teacher training course comprises instruction concerning various technologies. Specifically, it implements the PjBL approach guided by Stoller and Myers (Citation2019) (mentioned in Section 3). A detailed introduction to this study’s methodology is provided next.

4. Methodology

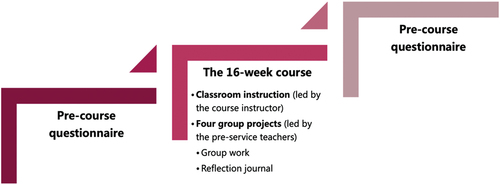

Mixed methods research can offer researchers various ways to gain empirical and descriptive insights into the topic with less danger of reaching a biased conclusion (Cohen et al., Citation2017; Denscombe, Citation2008). This mixed-methods study used quantitative and qualitative approaches, including pre- and post-questionnaires, project-based group work and reflection journals to depict a holistic, comprehensive and objective picture of the current status and development of Chinese pre-service language teachers’ TLLT competence. The pre- and post-questionnaires focused on collecting the pre-service English teachers’ self-report data on the three technology-related constructs (i.e., TK, TPK and TCK) to measure their TLLT competence before and after they took the course. The reflection journal aimed to investigate the participants’ viewpoints about the three aspects of TLLT and allowed them to freely express their ideas and perspectives based on their PjBL experience. In total, 33 third-year undergraduate students majoring in English language education participated in this research. They formed groups comprising three or four participants each to collaborate to complete four group projects.

4.1. Research procedure

At the beginning of the course, the participants were requested to self-evaluate their TLLT competence (including TK, TPK, TCK) by completing the questionnaire. Then, the 16-week course was implemented, during which the participants were assigned four group projects. After the classroom sessions, where the course instructor introduced knowledge about technologies, the pre-service language teachers gathered to prepare for their group projects. They first decided on each project’s theme before searching for information on the internet or in books. After finishing the project, they were asked to present it to the class and collect feedback from the audience. The course instructor assigned scores respectively for TK, TPK and TCK for each project. At the end of the course, the participants were asked to re-evaluate their TLLT competence. They were also required to keep a reflection journal detailing their learning experiences. The whole research procedure is shown in Figure .

4.2. An overview of the course

Regarding the course intervention, the pre-service English teachers in this study undertook a CALL course in their curriculum called Multimedia and Foreign Language Teaching. This course is student-centred, which includes task-based language teaching (TBLT), communicative language teaching (CLT), and interactive learning approaches. The course introduces essential technological approaches covering: (1) computer-assisted language learning (e.g., massive open online course (MOOC), game-based language learning); (2) mobile-assisted language learning (e.g., micro-lectures, social media-enhanced language learning); and (3) emerging technologies (e.g., augmented reality, virtual reality and artificial intelligence) in language learning.

4.3. The four group projects

The four group projects asked students to design a session/classroom activity about (1) MOOC, (2) game-based language learning, (3) a micro-lecture, and (4) social media. These projects aimed to develop the pre-service English teachers’ TK, TCK and TPK via planning, designing and collaborating.

The first group project required participants to create a course outline for an English MOOC. The course outline included the rationale for designing the course, the intended student population, an overview of the course, students’ prior knowledge, the overall course structure, assignments, exams, certificate requirements, discussion topics, and reference materials. The second group project required participants to integrate gamification into their English instructional activities. The activity had to include the activity’s name, type, platform, duration, and structure. The third group project required participants to create an English micro-lecture. Typically, such lectures consist of a video presentation on a narrowly defined topic. Participants were required to complete a 10-minute micro-lecture plan that included teaching objectives, a target student population, length, course structure, and a script. In the fourth group assignment, participants were tasked with designing an English language classroom activity on the selected social media platform. The project needed to include the activity’s name, the selected platform, the duration of the activity and the whole activity structure. Appendix A shows the title of the students’ projects and objectives for developing their TK, TCK and TPK.

4.4. Pre-and post-questionnaire

The pre-and post-questionnaires were designed based on Schmidt et al. (Citation2009) questionnaire. This instrument is appropriate for this purpose as it has been shown to be reliable in assessing TPACK for pre-service teachers. The reliability test results of this survey show that Cronbach’s alpha for different sets of items (i.e., TK, CK, PK, PCK, TCK, TPK, TPCK) ranges from 0.75 to 0.92, indicating acceptable reliability of this instrument. As the present study is only concerned with technology-related knowledge, we kept the items relating to TK, TCK and TPK. To better tailor it to the English education field, some wording was modified. For example, in Schmidt et al. (Citation2009), items in TCK cover subjects including mathematics, literacy, science and social studies:

I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing mathematics/literacy/science/social studies (Items 31–34 in Schmidt et al. (Citation2009)).

We changed these subjects to different aspects of the English language, including vocabulary, listening, reading, speaking, writing, grammar and translation.

I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing English vocabulary/listening/reading/speaking/writing/grammar/translation (Items 8–14 in our questionnaire).

The questionnaire, which contains 19 items, was conducted online. The platform we used is called Wenjuanxing (www.wjx.cn), which is one of the most popular and well-recognised online survey platforms in China. The questionnaire employed a five-point Likert scale (i.e., strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree). The whole questionnaire took approximately 10 minutes to complete. Appendix B presents the whole questionnaire.

The pre- and post-questionnaire data and the instructor’s scores were analysed using descriptive and statistical analysis. Mean scores were mainly determined via descriptive analysis. The statistical analysis (i.e., the paired sample t-test) was applied to determine whether there were statistical differences between the pre- and post-questionnaire results, as well as the instructors’ scores for each group project. Data were analysed via SPSS 26.0.

4.5. Reflection journal

Stoller and Myers (Citation2019) argued that the final step of PjBL requires learners to reflect on what they have learned via various approaches, including reflection journals. According to Godwin-Jones (Citation2013), students can record, report, and discuss their experiences and emotions in a reflection journal. In this study, the pre-service language teachers were asked to complete such a journal after undertaking each group project. The reflection journals were also distributed via Wenjuanxing. In total, 132 journals were collected, which contained more than 50,000 Chinese words.

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the journals. We firstly read all the journals several times and familiarised ourselves with the data. As the journals were highly personalised, we used an open-coding method, which is efficient for initially labelling and categorising chunks of data (Rivas, Citation2012). We descriptively labelled the data as “units of meaning” (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994, p.56) to obtain the initial codes at a relatively low conceptual level. The three constructs in TLLT—TK, TCK and TPK—became the three main themes. Subsequently, we grouped these initial codes and reorganised them into broad categories in TK, TCK or TPK at a more abstract level. There were three sub-themes in TK, seven sub-themes in TCK, and three sub-themes in TPK. After defining and naming the themes as well as identifying the relationships between the themes and sub-themes, initial results were examined. We then checked whether any information was missing and whether the coding was accurate before making modifications. All journal data were coded and analysed by MAXQDA Plus. The themes, sub-themes, codes and examples are presented in Table . Detailed results will be presented in Section 5.

Table 1. Themes, sub-themes and examples of the interview data

The analysis produced 243 codes in total. Of these, 86 related to TK, 76 to TPK and 81 to TCK. To ensure inter-rater reliability, the authors randomly invited an applied linguist to analyse 33 (25%) reflection journals. The results of the authors and the rater were then compared. The consistency was 93.6%, indicating that the analysis of the reflection journals had high inter-rater reliability.

4.6. Ethical issues

One of the most important factors in determining the quality of the research is ethical concerns (Henning, Citation2011). We provided participants with a thorough explanation of the research and obtained their consent before the research began. We also gave them the option to decline participation. They confirmed their approval by signing the consent form. Anonymity is another significant ethical issue. All participant data, including demographic information, was always kept private. All data were password-protected and only saved on the first author’s PC. Additionally, we let the participants know that this study would not interfere with their studies or daily activities.

5. Results

5.1. Results from the pre- and post-course questionnaire

As Table shows, regarding the pre-service language teachers’ self-report questionnaire scores on TK, TCK and TPK, the paired sample t-test results show statistically significant differences (p < .05) before and after the course. Specifically, the results indicate that from the pre-service language teachers’ perspective, the course and the PjBL approach significantly contributed to their TK, TCK and TPK (i.e., their TLLT competence). To measure the strength of the relationship between the scores before and after the course, the effect size of the 19 items has been calculated. As Table shows, the effect size of TK ranges from 0.689 to 1.165, the effect size of TCK from 0.431 to 0.920, and the effect size of TPK from 0.431 to 1.015.

Table 2. Results of the paired sample T-test

Table 3. The effect size of the 19 items in three dimensions

5.2. Results from the reflection journals

5.2.1. TK

Regarding the results of the reflection journals, there are three sub-themes in TK, including: (1) technologies for preparation, (2) technologies for collaboration, and (3) technologies for design. “Technologies for preparation” refers to the technologies that the participants applied when preparing their group work. According to their responses, the participants prepared by using various online platforms and technologies. In particular, they preferred to make preparations via social media platforms. For instance, as Student Z mentioned in her group, social media, which has penetrated most people’s daily life, was one of the main resources that they used to prepare materials:

Initially, we searched on WeChat and Bilibili based on the keyword “telling Chinese stories well” and came up with many ideas. We also searched for keywords through Red. (Student Z)

For collaboration, the participants preferred to use online shared documents with their teammates. For example, Student J shared that she and her groupmates used Jinshan Document, which is a Google Docs-like shared document platform to collaborate. Other platforms like Tencent Document and Feishu were also commonly used by the participants, according to responses from Students Y and L.

In terms of course design, the pre-service language teachers preferred to use the technologies and platforms that had been taught in the course. As Student C wrote:

We decided to use Chinese University MOOC to design the course and distribute course resources, because our teacher showcased how to use this platform in the class. (Student C)

Besides, platforms that are similar to the ones learnt in the course were also used by the participants. As Student J reported:

We chose Quizizz, which is like Quizlet that we learned in our course. Quizizz is like an extensive library that contains rich information, amazing competitive games, timely feedback, and clear study reports. We used this platform because we feel more confident when using a platform that we have learnt before. (Student J)

Therefore, the investigated pre-service language teachers tended to rely on the social media that they used in their daily lives to search for the information they needed. Chinese online shared document platforms were popular among this group of students for accomplishing the four group projects. Apart from that, they preferred to use the technologies and platforms taught or mentioned in the course, which made them feel more confident and comfortable.

5.2.2. TCK

Seven language knowledge aspects (i.e., vocabulary, listening, reading, writing, speaking, grammar, and translation) were mentioned in the pre-service language teachers’ reflection journals. Vocabulary was mentioned most (i.e., 22 codes), while grammar was rarely mentioned (i.e., only 3 codes). This may indicate that the pre-service language teachers perceived that the course and the four group projects helped them to practice vocabulary more than other aspects of language learning, especially grammar. Participants perceived that developing such English language courses or course activities could help them to review and consolidate key vocabulary and sentence patterns. For example, as Student W stated:

English expressions about the Dragon Boat Festival can be taught in micro-lectures, such as the historical origins and the evolution of customs. We’ve learned these expressions during the preparation process. (Student W)

For listening, the pre-service language teachers mentioned that they had used a variety of English materials and resources. They could practice their listening skills during the design process, as they needed to listen to and comprehend the content. Similarly, the participants thought their reading skills could be improved, because they read a large volume of English materials. For writing, although there was no writing task for the participants, they were still required to write the course plan and details in English. Regarding speaking, as Student Y shared, they designed a series of speaking tasks for students, such as introducing Chinese cuisine to a foreign friend and recording this in a video. They also undertook mock exercises when perfecting their design. Besides, they attempted to discuss issues in English. All these efforts contributed to their improved speaking skills.

Despite using a variety of English materials, the course included many materials written in Chinese. Therefore, the trainee teachers needed to translate them into English. During this process, they were able to practice their translation skills.

However, grammar was the least mentioned aspect. This is because it was not the focus for the PjBL task. As Student Y said:

The course we designed mainly aimed to help students fluently and appropriately discuss Chinese culture in English rather than correct their grammatical errors. Accordingly, we didn’t pay much attention to this aspect. I don’t think my grammar improved during this process. (Student Y)

To summarise, the four projects benefited the pre-service language teachers’ development of their language abilities, including vocabulary, listening, reading, speaking, writing and translation. The teachers were generally satisfied with the PjBL process.

5.2.3. TPK

In terms of TPK, the trainee teachers’ responses could be categorised into three stages: before class, in class and after class. Before class, they preferred to use videos or micro-lectures to help their students preview knowledge. According to Student B:

We decided to design and use videos for previewing to help students better understand the background information. Regarding our course, our students could learn some expressions about Chinese tea, which could lay a solid foundation for their studies in class. (Student B)

During class, the pre-service language teachers integrated various types of multimedia technologies to deliver content. As Student D mentioned, they tried to apply texts, pictures, audio and videos in their course design, and technological approaches such as social media platforms and games taught in the course were also applied. From their perspective, these multimedia technologies and platforms could motivate their students to learn the target language:

I am impressed by various technologies, including videos, audio, flash, pictures and so on. And there are many online resources available for teachers to choose from for their students, such as micro-lectures and online educational videos like TED. I believe these technologies can stimulate my students’ interest in learning English. (Student D)

In terms of after class, games were popular among the trainee teachers to review the knowledge they learnt in class. For example, Student W shared that her group applied online games like Bamboozle to help students review the English words learnt in the class. Her group thought that teachers could use games to promote collaborative learning and contextualised learning. Similarly, Student Q wrote:

Games like Quizlet and Kahoot! are effective and exciting ways for our students to review what they have learned during class. The games are different from traditional paper exercises that are quite boring. They can compete and learn from each other during the games, which could benefit their collaborative and communicative abilities. (Student Q)

In summary, the pre-service language teachers shared their viewpoints on TPK, which could be divided into three stages: before class, during class, and after class. They preferred videos or micro-lectures to help their students preview knowledge. During class, various multimedia technologies and platforms were applied. After class, games were widely used, as these could motivate students to review the knowledge that they had acquired in the class.

6. Discussion

Liu and Kleinsasser (Citation2015) found that in previous CALL training programmes, teachers frequently restricted themselves to the conventional use of technology by requiring their students to recite content from online websites. One of the greatest challenges that pre-service language teachers face is to determine which tools and platforms can be integrated into their lessons (Vanderplank, Citation2010). They should decide the extent to which technologies meet teaching objectives and can be adapted to specific teaching contexts. In this study, the four group projects required the pre-service language teachers to learn how to use technological tools and platforms before integrating selected tools and platforms into their language teaching activities. This provided hands-on experience in integrating TK, TPK and TCK required for TLLT competence.

Based on Mishra and Koehler’s (Citation2006) widely-recognised TPACK framework, this study aimed to investigate how participation in a PjBL course could enhance the TLLT competence of prospective language teachers. Quantitative data (i.e., results of the pre- and post-course questionnaire) indicate significant differences before and after the course in their TLLT competence. Qualitative data (i.e., responses in their reflection journals) show their learning process and gains during the class, which are valuable complements to their self-report questionnaire results. The results of this study echo previous studies (e.g., Liu & Kleinsasser, Citation2015; Tseng & Yeh, Citation2019), which demonstrate that PjBL projects can assist pre-service language teachers in developing their TLLT competence.

In contrast to conventional paper-based assessments that primarily measure learners’ final learning outcomes, PjBL presents an authentic, dynamic and creative approach for educators and pre-service language teachers to evaluate progressive academic development (Poehner & Lantolf, Citation2005). Authenticity, as many scholars (e.g., Hafner & Miller, Citation2019) have argued, should be embodied in (1) audiences, (2) purposes, and (3) texts. The participants in our study were not only learners but also prospective teachers who should consider their future students and clarify the teaching objectives before designing courses and tasks for them. When selecting materials, they should be critical and innovative in searching for up-to-date, high-quality references and resources. According to their responses in their reflection journals, social media has already become one of the main sources when they search for information, and online shared document platforms are a prominent choice when undertaking group work. Although many previous studies have demonstrated that social networking sites and web-based collaboration tools can benefit interactive learning, promote language learning outcomes and reduce learning anxiety (e.g., Benati & Angelovska, Citation2016; Bikowski & Vithanage, Citation2016; Sun & Chang, Citation2012; Vurdien, Citation2013; Yang, Citation2011; Yim & Warschauer, Citation2017), language learners, including pre-service language teachers, should also develop their new media literacy (Dezuanni, Citation2015; Zhang & Wu, Citation2023) to critically understand, analyse, evaluate and create course content. Teachers and instructors should consider integrating new media literacy education into the current course and curriculum.

Furthermore, the results of this study also reflect that the pre-service language teachers tended to use the technological tools and platforms that the course instructor taught in the course. As a coach, the instructor played a significant role in supporting them in completing the group projects. Many Chinese students are very reliant on their teachers’ instructions because of the washback effect of high-stakes exams and spoon-fed teaching. The importance of teacher’s guidance in students’ task completion and learning outcomes has been highlighted in previous studies (Liu & Stapleton, Citation2014). In this case, future studies and practices should make more efforts on offering pre-service teachers constructive and timely instructions, support and feedback.

In this study, the prospective teachers perceived that their English language abilities, including listening, reading, writing, speaking, translation and grammar, improved during the PjBL process. Previous empirical studies have also verified the affordances of PjBL for different student groups. For instance, Alotaibi (Citation2020) focused on secondary school students’ persuasive writing skills, finding significant effects of PjBL on participants’ writing performance. Bakar et al. (Citation2019) study aimed to improve EFL college students’ oral communicative competence via a 12-week PjBL-based course called Communicative English, and the results demonstrated its effectiveness. Li et al. (Citation2015) conducted a study that attempted to apply PjBL in translator education and discussed how PjBL could be incorporated into business translation teaching in China. After taking the translation course, the participants in Li et al. (Citation2015) study found that the divide between classroom teaching and the real field of translation was narrowed, and the participants reported positive and encouraging feedback on this PjBL course. Therefore, future empirical studies and practices could continue exploring the effectiveness of PjBL in pre-service language teachers’ language ability development.

Responses regarding TPK revealed that the pre-service language teachers used various technological tools and platforms at different stages. According to Lai (Citation2013), students’ technology use is impacted by many factors, including: (1) attitudinal factors (e.g., learning motivation, perceived usefulness of technology, perceived compatibility between technology use and learning expectations), (2) perceived support from teachers and peers, (3) self-regulation abilities, and (4) confidence in selecting and using technologies. When pre-service language teachers consider integrating technologies into different stages of class, we, as educators and instructors, should consider the complexity of technology use in different teaching settings and give pre-service teachers adaptive suggestions to support their teaching.

7. Concluding remarks

The findings of this study shed light on the effectiveness of a PjBL course for Chinese pre-service teachers’ TLLT development. After the 16-week course, their three constructs of TLLT—TK, TCK and TPK—had all developed significantly. According to their responses in their reflection journals, in terms of TK, the trainee teachers preferred to use social media to search for information. They also tended to use online shared document platforms to collaborate with their groupmates. The technologies and platforms taught by the instructors were most popular. Regarding TCK, they reported the gains from the four projects relating to their different English language abilities (i.e., vocabulary, listening, reading, speaking, writing, translation and grammar). Their responses about TPK could be categorised into three stages: before class, during class and after class. According to their responses, they favoured using videos or micro-lectures to help their students understand the materials before class. They utilised various multimedia technologies in class to meet different teaching needs. They frequently used games after class, which they believed could motivate their future students to review the information acquired.

This study provides insights for educators, researchers and teachers to understand Mishra and Koehler’s (Citation2006) TPACK framework. It also showcases a well-designed curriculum and a technology-rich language learning environment, which could contribute to both enhanced curriculum design and teachers’ professional development. However, despite its valuable findings, there are also some limitations which must be acknowledged. First, the pre-service teachers did not implement the lesson plans they created in actual classrooms. Future research could therefore examine how pre-service and in-service language teachers apply their lesson plans in actual classroom settings and ask them to reflect on their lesson plans’ efficacy. Second, this study did not require the prospective teachers to compose a CALL lesson plan before the PjBL project to compare the pre- and post-project outcomes. This is because the participants were pre-service language teachers who lacked the knowledge to design lesson plans before the class. Thus, future studies may wish to compare the lessons created by in-service teachers before and after PjBL to evaluate changes in their TLLT competence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Danyang Zhang

Danyang Zhang is an Assistant Professor and Associate Dean at the College of International Studies, Shenzhen University. Her research interests include: second language vocabulary acquisition, technology-enhanced language learning, and teacher development. Danyang has published her work in numerous SSCI journals, including Applied Linguistics, Computer Assisted Language Learning and Language Teaching Research. She currently serves as the Associate Editor of IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies (SSCI & SCI) and is a journal reviewer for ReCALL, Language Learning & Technology, Virtual Reality and Interactive Learning Environments. She has presented her projects at several international conferences, including BERA, CALL and EUROCALL. She is the winner of the BJET Best EdTech Paper Award and an awardee of mLearn Conference Best Paper.

Wenjing Wang

Wenjing Wang is a passionate educator and researcher in second language teaching and technology-enhanced language learning. She is majoring in English Teaching at the College of International Studies, Shenzhen University. She has rich experience in rural volunteer teaching and education practice. She has presented her work at conferences such as the 2nd APSCE International Conference on Future Language Learning (ICFULL).

References

- Agyei, D. D., & Voogt, J. (2012). Developing technological pedagogical content knowledge in pre-service mathematics teachers through collaborative design. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28(4), 547–19. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.827

- Alotaibi, M. G. (2020). The effect of project-based learning model on persuasive writing skills of Saudi EFL secondary school students. English Language Teaching, 13(7), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n7p19

- Bakar, N. I. A., Noordin, N., & Razali, A. B. (2019). Improving oral communicative competence in English using project-based learning activities. English Language Teaching, 12(4), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v12n4p73

- Benati, A., & Angelovska, T. (2016). Second language acquisition: A theoretical introduction to real world applications. Bloomsbury.

- Bikowski, D., & Vithanage, R. (2016). Effects of web-based collaborative writing on individual L2 writing development. Language Learning and Technology, 20(1), 79–99.

- Chai, C. S., Koh, J. H. L., Ho, J. H. N., & Tsai, C. C. (2012). Examining preservice teachers’ perceived knowledge of TPACK and cyberwellness through structural equation modelling. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28(6), 1000–1019. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.807

- Chand, R., Alasa, V. M., Chitiyo, J., & Pietrantoni, Z. (2022). Preparation of pre-service teachers: Assessment of generation Z students. In K., Jared (Ed.), Handbook of research on digital-based assessment and innovative practices in education (pp. 116–130). IGI Global.

- Chao, C. C. (2015). Rethinking transfer: Learning from call teacher education as consequential transition. Language Learning & Technology, 19(1), 102–118.

- Chen, C. P. (2018). Understanding mobile English-learning gaming adopters in the self-learning market: The uses and gratification expectancy model. Computers & Education, 126, 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.015

- Cheng, K. H. (2017). A survey of native language teachers’ technological pedagogical and content knowledge (TPACK) in Taiwan. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(7), 692–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1349805

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

- Debski, R. (2006). Theory and practice in teaching project-oriented CALL. In P. Hubbard & M. Levy (Eds.), Teacher education in CALL (pp. 99–114). John Benjamins.

- Denscombe, M. (2008). Communities of practice a research paradigm for the mixed methods approach. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2(3), 270–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689808316807

- Dezuanni, M. (2015). The building blocks of digital media literacy: Socio-material participation and the production of media knowledge. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 47(3), 416–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2014.966152

- Fried-Booth, D. L. (2002). Project Work. Oxford University Press.

- Godwin-Jones, R. (2013). Integrating intercultural competence into language learning through technology. Language Learning & Technology, 17(2), 1–11.

- Golonka, E. M., Bowles, A. R., Frank, V. M., Richardson, D. L., & Freynik, S. (2014). Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 27(1), 70–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.700315

- Grant, S. (2017). Implementing project-based language teaching in an Asian context: A university EAP writing course case study from Macau. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 2(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-017-0027-x

- Habibi, A., Yusop, F. D., & Razak, R. A. (2020). The role of TPACK in affecting pre-service language teachers’ ICT integration during teaching practices: Indonesian context. Education and Information Technologies, 25(3), 1929–1949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10040-2

- Hafner, C. A., & Miller, L. (2019). English in the disciplines: A multidimensional model for ESP course design. Routledge.

- Hedge, T. (1993). Key concepts in ELT: Fluency and project. ELT Journal, 3, 275–277.

- Henning, B. (2011). Standing in livestock’s “long shadow”: The ethics of eating meat on a small planet. Ethics & the Environment, 16(2), 63–93. https://doi.org/10.2979/ethicsenviro.16.2.63

- Hong, K. H. (2010). CALL teacher education as an impetus for L2 teachers in integrating technology. ReCALL, 22(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834400999019X

- Iivari, N., Sharma, S., & Ventä-Olkkonen, L. (2020). Digital transformation of everyday life–how COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183

- Jones, J. F. (2001). CALL and the responsibilities of teachers and administrators. ELT Journal, 55(4), 360–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.4.360

- Lai, C. (2013). A framework for developing self-directed technology use for language learning. Language Learning & Technology, 17(2), 100–122.

- Lin, B., & Hsieh, C. T. (2001). Web-based teaching and learner control: A research review. Computers & Education, 37(3), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1315(01)00060-4

- Liu, Y., Holden, D., & Zheng, D. (2016). Analyzing students’ language learning experience in an augmented reality mobile game: An exploration of an emergent learning environment. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 228, 369–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.055

- Liu, M. H., & Kleinsasser, R. C. (2015). Exploring EFL teachers’ CALL knowledge and competencies: In-service program perspectives. Language Learning & Technology, 19(1), 119–138.

- Liu, F., & Stapleton, P. (2014). Counterargumentation and the cultivation of critical thinking in argumentative writing: Investigating washback from a high-stakes test. System, 45, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.05.005

- Li, D., Zhang, C., & He, Y. (2015). Project-based learning in teaching translation: Students’ perceptions. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2015.1010357

- McNeil, L. (2013). Exploring the relationship between situated activity and CALL learning in teacher education. ReCALL, 25(2), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344013000086

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

- Poehner, M., & Lantolf, J. (2005). Dynamic assessment in the language classroom. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 233–265. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168805lr166oa

- Reinhardt, J. (2019). Social media in second and foreign language teaching and learning: Blogs, wikis, and social networking. Language Teaching, 52(1), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000356

- Rivas, C. (2012). Coding and analysing qualitative data. Researching Society and Culture, 3(2012), 367–392.

- Schmidt, D. A., Baran, E., Thompson, A. D., Mishra, P., Koehler, M. J., & Shin, T. S. (2009). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): The development and validation of an assessment instrument for preservice teachers. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42(2), 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2009.10782544

- Stoller, F. L., & Myers, C. C. (2019). A five-stage framework to guide language teachers. In A., Gras-Velazquez (Ed.) Project-Based Learning in Second Language Acquisition: Building Communities of Practice in Higher Education. Taylor & Francis.

- Sun, Y.-C., & Chang, Y.-J. (2012). Blogging to learn: Becoming EFL academic writers through collaborative dialogue. Language Learning & Technology, 16(1), 43–61.

- Tai, S. J. D. (2015). From TPACK-in-action workshops to classrooms: CALL competency developed and integrated. Language Learning & Technology, 19(1), 139–164.

- Tseng, J. J. (2018). Exploring TPACK-SLA interface: Insights from the computer-enhanced classroom. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(4), 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1412324

- Tseng, S. S., & Yeh, H. C. (2019). Fostering EFL teachers’ CALL competencies through project-based learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 22(1), 94–105.

- Valtonen, T., Sointu, E., Kukkonen, J., Makitalo, K., Hoang, N., Häkkinen, P., Järvelä, S., Näykki, P., Virtanen, A., Pöntinen, S., Kostiainen, E., & Tondeur, J. (2019). Examining pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge as evolving knowledge domains: A longitudinal approach. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35(4), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12353

- Vanderplank, R. (2010). Déjà vu? A decade of research on language laboratories, television and video in language learning. Language Teaching, 43(1), 1–37.

- Vurdien, R. (2013). Enhancing writing skills through blogging in an advanced English as a foreign language class in Spain. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 26(2), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2011.639784

- Wang, L., Ertmer, P. A., & Newby, T. J. (2004). Increasing preservice teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for technology integration. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 36(3), 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2004.10782414

- Yang, Y.-F. (2011). Learner interpretations of shared space in multilateral English blogging. Language Learning and Technology, 15(1), 122–146.

- Yang, Y. T. C., & Wu, W. C. I. (2012). Digital storytelling for enhancing student academic achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation: A year-long experimental study. Computer & Education, 59(2), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.12.012

- Yim, S., & Warschauer, M. (2017). Web-based collaborative writing in L2 contexts: Methodological insights from text mining. Language Learning & Technology, 21(1), 146–165.

- Zhang, D., & Wu, Y. (2023). Becoming smart “digital natives”: Cultivating Chinese English majors’ new media literacy via Journalism English reading and listening. Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 3(2), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1515/jccall-2022-0029

Appendix A

The titles of students’ group work and objectives for developing their TK, TCK and TPK

Appendix B

Questionnaire

Personal Information

Name:

Class:

Technology Knowledge (TK)

1. I know how to solve my own multimedia technical problems.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

2. I can learn multimedia technology easily.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

3. I keep up with important new multimedia technologies.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

4. I frequently play around with multimedia technology.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

5. I know about a lot of different multimedia technologies.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

6. I have the technical skills I need to use multimedia technology.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

7. I have had sufficient opportunities to work with different multimedia technologies.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

Technological Content Knowledge (TCK)

8. I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing English vocabulary.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

9. I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing English listening.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

10. I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing English reading.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

11. I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing English speaking.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

12. I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing English writing.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

13. I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing English grammar.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

14. I know about technologies that I can use for understanding and doing English translation.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK)

15. I can choose multimedia technologies that enhance the teaching approaches for a lesson.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

16. I can choose multimedia technologies that enhance students’ learning for a lesson.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

17. My program has caused me to think more deeply about how multimedia technology could influence the teaching approaches I use in my future classroom.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

18. I am thinking critically about how to use multimedia technology in my future classroom.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree

19. I can adapt the use of the multimedia technologies that I am learning about to different teaching activities.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly agree