Abstract

The article begins with a discussion on the importance, subjectivity, and longstanding search for a definition for Quality Education (QE). It conceptualizes QE in terms of “resilience” and “responsibility towards other”. It reviews the theoretical landscape and philosophical contributions of philosophers and learning theories to the field of education. It seeks to identify salient principles of QE from ancient times to the digital era and it speculates of how philosophers and learning theories would have thought about digital pedagogy today. Three principles of QE are proposed: 1) mutual respect and reciprocity, 2) differentiated and student-centered instruction, 3) attainment of knowledge for a virtuous humanity, along with two universal, timeless values: Equity and Democracy. The paper concludes with a discussion of how democracy and equity could be supported by Nussbaum’s model of human development as to cultivate the ethos of schools in the digital ages and transform QE into classroom practices.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This manuscript provides a literature review about quality education, from ancient philosophers to learning theories implemented in today’s digital classrooms. It attempts to register if there could be a consensus between all stakeholders when posing the questions “What is quality education in global times?” and “Can there be a definition for quality education that is accepted by all?” The concept of equity and democracy in education are prevailing to both philosophers and learning theories, along with three overarching principles; 1. An environment of mutual respect and reciprocity among all participants 2. Differentiated instruction and student-centered approaches 3. Attainment of knowledge for a virtuous humanity. Finally, the paper seeks to apply the critical tenets of quality education in school pedagogy and teachers’ practices by liaising the concept of quality with the current global digital setting and relating it with the local context of the educational reality in the classroom.

1. Introduction

From ancient times to the digital era, from the International Organizations to ministries of education, from philosophers, academics to every practitioner, from headmasters to every teacher, parent and student, from different psychological theories, pedagogies and teaching methodologies to the actual implementation in the classroom and to the actual process of learning taking place in each individual’s mind, the emphasis seems to be placed in the quality of education. The discourse around quality seems to be long and never-ending. Different perspectives, the uniqueness of the learning process, the non-visible and therefore non-measurable factors that affect learning and the unlimited opportunities to learn perplex the already overcomplicated concept of quality even more.

The question about the ingredients of “Quality Education” is still open to debate, being redefined constantly based on the complex and evolving reality in the class, in education, in society and in the world. In 2014, as a co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, Malala Yousafzai mentioned in her speech that she wants “to see every child getting Quality Education” and “education went from being a right to being a crime” referring to the dangers children can face in a few countries when going to school. In the digital era, there are countries and schools that offer to their students the most up-to-date methodologies and infrastructures and may travel around the world as a part of their school education curriculum and on the other side, children can get shot on their way to school. The increasing inequalities make “Quality Education” harder to define.

“Quality Education” is an elusive concept that can take different meanings and encompass different values, appearing in many levels from early childhood education to postgraduate levels of education (Master and PhD level) of any educational system. Different views on what could make humans happier and more resilient along with what could lead to more harmonious, just or economically solid and powerful societies convey to “Quality Education” different orientations, goals and ingredients.

As Gibson (Citation1986) describes it “Quality is notoriously elusive of prescription, and no easier even to describe and discuss than deliver in practice”. The term “Quality” measures value, it is linked to what is beneficial and important (Dochy et al., Citation1990). Quality becomes a multi-valued concept depending on the specific situation, as well as a multi-level concept, which includes different references, different contexts in which it can be analysed (Mills, Citation1984). Different groups- and probably each individual- conceptualize differently what quality education is. This great variety in conceptualizing quality education can relate both with political, moral, ideological and religious beliefs and with a set of ideas of what actions are the best for embracing the human nature and exploiting its potential in a way that the local, national and even global society could benefit from building a better world for all. Different views on what constitutes a better society and a better world set different goals to be achieved via educational systems. For instance, a group of people may believe that quality education presupposes growing conscientious individuals that coexist in harmony with themselves and others, while some other group may favour high educational outcomes in terms of success rate in high profile Universities or absorbance in well paid jobs. Another group may believe that the goal is to combine these two, growing conscientious individuals that will be able to achieve high educational outcomes, and so on.

Similarly, when referring to Higher Education and quality, Harvey and Green (Citation1993, 10) mention that quality is frequently alluded to as a relative idea. They identify two ways in which quality is relative. Firstly, they mention that quality is relative to the person who uses the term and the conditions in which it is conjured. It can mean various things to various individuals; for sure, a similar individual may embrace various conceptualizations at various minutes. And when the “whose quality” issue comes up, Harvey and Green state that a number of “stakeholders” is involved, including learners, employers, educators and non-educators, policy and funding agencies, accreditors and evaluators (Burrows & Harvey, Citation1992). Everyone has a different quality viewpoint. This is not a different view of the same thing, but different views on different things, which have the same tag. Secondly, Harvey and Green (Citation1993) recognize the “criterion” of subjectivism of quality, explaining that quality is viewed in terms of absolutes … “As an absolute [quality] is similar in nature to truth and beauty. It is an ideal with which there can be no compromise” (Sallis & Hingley, Citation1991, 3).

What is more, one major adversity in finding a definition for quality education is to predict the proper material and conditions for learning based on the unknown needs of future learners and the dynamics of the future societies where they will be living. The central conceptual axis of this article is: a) the view of Davies and West-Burnham (Citation1997, 12) on the quality of education, according to which any political innovative quality initiative will be altered if its historical origins are not properly analyzed and b) the view according to which the quality of education in a certain period of time is related to the set of values that characterize society and its level of education and culture. In a sense, quality education is a long -if not lifelong- process that can be assessed by the learner himself/herself, and unfortunately in most cases, once the process is near completion where remediation actions are sometimes not possible. Therefore, “Quality Education” is subjective and it is a term that influences everybody, every person, every country and the world. From ancient times, pedagogy, the theory and practice of learning, the effort to understand what social, political, contextual, psychological parameters enhance the learning capacity of a child intrigued all thinkers.

2. Conceptual framing of quality education

The term “Quality Education” is chosen opposed to other terms like “Effective Education” for two main reasons. First, “quality” has ideological and political connotations and is often used in educational goals and policy documents of national authorities and international organizations (i.e The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development endorsed by all United Nations Member States recognizes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the 4th SDG is named “Quality Education”, UNESCO’s report: Education for All: The Quality Imperative. EFA Global Monitoring Report (Citation2005)). The World Declaration on Education for All in Jomtien in Citation1990 and the Dakar Framework for Action in 2000 (UNESCO, Citation2000) recognized “quality” as the prerequisite for achieving equity. According to the Dakar Framework quality is “at the heart” of education. Second, “quality” has a broader scope enveloping parameters that do not only relate with measurable learning performance and outcomes, but with a sense of completeness in one’s life. It deals with the intangible of the learning process, the inner motivation that may be ignited by the example of people (parents, teachers, caretakers, thinkers, leaders, policy makers etc) or other traits of personality that inspire to learn, to continue learning and to adhere to a set of values.

Although the attributes that could be characterising “Quality Education” are infinite, this paper conceptualizes “Quality Education” on two main attributes. The first attribute is “resilience”. Resilience is linked to the cognitive and emotional dimensions of the learning process. Cognitive development is an explicitly defined objective by all educational systems. The curricula of each educational system ascribe teaching and learning methodologies, along with assessment methods that could evidence the cognitive progress of a learner. The term “resilience” goes a step further and is harder to be evidenced, since it describes the inner motivation, the emotional strength one can have to continue learning throughout his/her life. “Resilient learners can adapt to various tasks and environments, taking advantage of opportunities to reach their individual potential. Such learners have the capacity and agency to identify and capitalise on opportunities given to them by the system and create their own. They are also able to move between learning tasks and environments, engaging pro-actively in efforts to enhance them. All resilient learners can eventually reach their potential regardless of background, interests or needs” (OECD, Citation2021, p.10). The term resilience is defined as the positive adjustment that empowers individuals to surpass adversity, while academic resilience characterises students who thrive in school despite coming from a socio-economically disadvantaged background (Borman & Overman, Citation2004, Martin and Marsh, Citation2006, OECD, Citation2011, Sandoval-Hernandez & Cortes, Citation2012, Agasisti & Longobardi, Citation2014, Sandoval-Hernández and Białowolski, Citation2016). The second attribute is “the sense of responsibility towards others”. The ultimate aim of education is a major concern of every teacher, parent, educational system and international organization. This concern is diffused in school curricula, in many reports of educational systems, national and international organizations. For instance, in Unesco’s report Learning to Be (1972), there is a deep concern on how learning can foster human values, as to open the way for a Scientific Humanism, Social Commitment Towards Being Completely Human in a Learning Society. In this sense, the attribute “the sense of responsibility towards others” is set as a way to delve into the different values embedded in the epistemology of eight thinkers and in learning theories. It is generally acknowledged that the main goals of education are reflected in today’s school curricula with the form of values; a variety of descriptions is used to aspire local and global cultural values, peace education, citizenship education, inclusive practices, ways of learning to live together, helping one another, being in favor of social justice, accepting and building on differences, contributing to humanity and so on.

3. Method

The aim of this article is to unveil the universal, timeless values and salient principles embedded in Quality Education and to propose particular classroom practices that could be implemented in schools. Discussions regarding the transfer of responsibility for improving the quality of education from the international or/and national level to the school or individual level, establishing the educational discourse also create a particular concern in how quality is understood and interpreted in classroom practices. To this end, this article attempts to shed light on the thoughts of 8 great thinkers and 6 learning theories in relation to “Quality Education”. The analysis of some dominant epistemologies of thinkers and learning theories is relevant to broader global discussions and policies that codify pedagogy through national policy, funding schemes, basic school curricula, teaching standards, and teacher education schemes. The article’s scope revolves around an endeavor to discern if there is a correspondence between the stands of thinkers and these prominent learning theories and some consensus of what quality education is from ancient times to the digital era. In short, the rationale of this paper is to look for patterns among philosophers and learning theories and, if possible, to connect ideas between past and present and suggest some possibilities for consensus for the current “glocal” (global + local) educational practices.

If the aim of Quality Education is to build resilience and the acceptance of responsibility towards others two research questions are emerged:

What are Quality’s Education underlying principles coming from the past that are still relevant today?

Based on the analysis of the epistemologies of the thinkers and learning theories, would it be possible to speculate if they would be in favor of the digital pedagogy?

Answering these questions will contribute in the teacher education field. Every teacher as part of his/her professional development forms his/her identity and constructs a personal teaching philosophy. Developing a teaching philosophy promotes teacher agency in that it guides teachers to take ownership of the teaching practices they integrate in the classroom, as well as it guides teachers to understand the cognitive and emotional impact of these practices to their learners. A personal teaching philosophy elucidates to the teacher the prevailing values he/she wishes to diffuse to his/her learners. In addition, answering these questions will reveal the universal values embedded in the concept of Quality Education and propose specific classroom practices that cultivate the ethos of learners in the digital ages by developing empathy for the “other”.

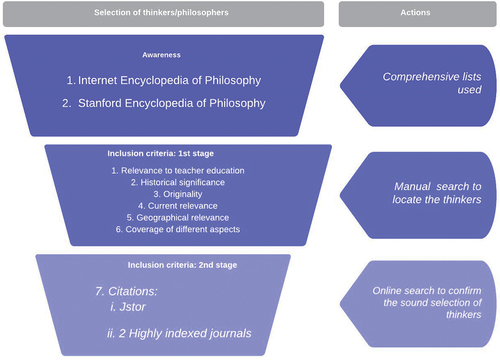

At the outset, to gain awareness of the philosophers and thinkers throughout history, two comprehensive lists were used, the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Subsequently, a manual selection of the philosophers was executed through the implementation of inclusion criteria, aimed at identifying those individuals who have had the most profound impact and exerted the greatest influence on the field of teacher education and the formation of pedagogical reflection.The following inclusion criteria were applied:

Relevance to teacher education: The philosopher’s work should be related to teacher education and should have a significant impact on the field.

Historical significance: The philosopher’s work should have had a significant impact on the development of teacher education over time.

Originality: The philosopher’s work should be original and not simply a repetition of existing ideas.

Current relevance: The philosopher’s work should still be relevant and applicable to teacher education today.

Geographical relevance: The philosopher’s work should be applicable to different educational systems and cultures.

Coverage of different aspects: The philosopher’s work should cover different aspects of teacher education such as teaching methods, curriculum development, teacher’s professional development, and educational policies.

Citations: The philosopher’s work should be widely cited in scientific/academic journals and in highly indexed journals in teacher education.

Consequently, the thinkers selected were based first on an attempt to depict the continuation of ideas through millennia and across the globe ensuring in this way a diversity of perspectives, and second, on the impact of their work to the field of “Teacher Education” beyond their country and lifespan. There were two stages on implementing the 7 inclusion criteria. At first, the first six criteria were applied to track the 8 thinkers. Then, the 7th criterion was applied to confirm the sound selection of the thinkers. The 7th criterion was based on a two stage internet search. The procedure for selecting the thinkers is depicted in Figure .

Two Greek philosophers who lived in successive years and the ideas of the first influenced the ideology of the other, were selected, Plato and Aristotle; two French thinkers having lived in different centuries, René Descartes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau; one British, John Locke; one German, Immanuel Kant; one American, John Dewey and one Brazilian, Paolo Freire. Then, to validate the sound selection of these eight thinkers and to cross-check the impact of their work to the educational scientific community, a two stage internet search was applied, which was performed in October 2022. The first stage was on Jstor, a digital library that provides access to a vast collection of academic content in the humanities and social sciences and the second on two highly indexed journals. Table depicts the results on the Jstor internet search, where the name of each philosopher was placed on the search box while the academic content of journals was ticked. In the second stage, two journals being highly indexed in the Journal Citations Reports (JCR) were selected: The Review of Educational research having the 1st rank and the Journal of Teacher Education having the 35th rank out of 267 journals in the 5 year impact factor in the Education and Educational Research field. The Review of Educational Research was selected as it is the higher indexed journal for the past five years and the Journal of Teacher Education was selected based on its thematic relevance with the field of “Teacher Education”. Table displays the results from the search conducted in the Review of Educational Research,while Table depicts the results from the search in the Journal of Teacher Education. In each of these two journals, the name (Plato, Aristotle) or last name of the thinker/philosopher was placed on the search box. In particular, the first column presents the name/last name of the philosopher, the second column the number of the articles where there is at least one reference to the name/last name of the philosopher, and the third column presents some indicative articles in which the philosophers are referenced. As it is evidenced in both tables, the articles in which the work of the eight thinkers is mentioned deal with themes of education, learning, educational changes, philosophical aspects of education, educational practice, research and teacher education, which are all linked to the conceptual framing of “Quality Education” as the intangible of the learning process that inspire to learn and to continue learning, and build towards resilience and the acceptance of responsibility towards others.

Table 1. Number of mentions found on journals in jstor for each philosopher

Table 2. Review of Educational Research

Table 3. Journal of teacher education

Ιn parallel, this article focuses on the intangible of the learning process as prescribed by six influential learning theories; behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism and social constructivism, critical pedagogy, transformative learning and connectivism. Behaviorism, cognitivism, (social) constructivism are examined as they are the primary learning theories. Critical pedagogy is viewed, as it is liaised with the notions of equity and social justice and with invisible factors that could build the sense of responsibility towards others. Transformative learning is explored as it is linked with adult training, teacher professional development and teacher education in general. Connectivism is examined as it is one of the most current learning theories that is strongly associated with the digital educational landscape. Needless to mention, that the selection of the eight thinkers and the six learning theories are not exhaustive and nor representative of the millenniums, centuries and the globe.

4. Mapping and unpacking the different concepts of “Quality Education”: The philosophers’ approach

This section presents an overview of the conceptual framing of “Quality Education” for each of the great philosophical/thinker in an attempt to identify the intangible of the learning process which build towards resilience and the acceptance of responsibility towards others. At first the epistemologies, theoretical contributions focusing on the ways knowledge, teaching and learning are conceived by each philosopher are presented. The purpose of education, the role of the teacher, the relationship of teacher-student are also examined, as intersecting strands existing within each epistemology and as identifiable elements of what “Quality Education” would mean to each philosopher. The two attributes of “Quality Education”, resilience (cognitive and emotional dimension) and responsibility towards others are examined for each philosopher/thinker. The potential impact of each epistemology on society, on other philosophies or educational strands and posterior thinkers is also mentioned.

4.1. Plato (around 427–347 BC) and Platonism

The origins of the term quality go back to the ancient Greek philosopher Plato who was Socrates’ student. It is of general consensus that Plato devoted his existence to vindicate Socrates’ remembrance and to immortalize Socrates’ thoughts, teachings and philosophy of education. It is likely Plato introduced the concept of “quality” (in ancient Greek “ποιότης”) in his dialog Theaetetus where Socrates outsets his inquiry to find out what truth is by embracing the work of the relativists, Protagoras and Heraclitus. Each said that the universe was in constant flux and that we could only learn from the feelings we got through our experiences, or as Protagoras stated: “Man is the measure of all things”. The Roman head of state and philosopher Cicero translated the Greek word “ποιότης” into the Latin word “qualitas” in his preface to Greek philosophy in 45 B.C.

The purpose of “Quality Education” in Platonic philosophy is to guide people to make the best use of their logic as to perceive the “Form of the Good”, that is to become virtuous. In Socrates, the connection between virtue and happiness is a relationship of personality: man acts in a good way by virtue and consequently is happy. Plato deals with the issue of education in The Republic (Reeve, Citation2004) as an important and essential part of a broader question of society’s prosperity. Plato followed the Socratic or Maieutic Method that was initially employed by Socrates. The Socratic Method is an interactive argumentative dialogue, based on questions being asked and answered in order to encourage logical assumptions and thoughts. Plato suggested equality in men and women depending on their capacity and willingness to learn. Plato supported a type of vocational education, so each group of people can accomplish their role in life in accordance with their abilities. In the Platonic system of education, teacher has a central role and a double mission; to be an instructor and a mentor. Plato believed that the good teacher must guide students towards knowledge and deep thinking and that the learning process is facilitated when trust is built between the learner and the teacher, and the teacher exhibits a true interest in learners. As indicated by Plato, an equitable society consistently attempts to give the best instruction to every one of its individuals as per their capacity, helping them conquer virtue and happiness, by the means of acquiring knowledge. For Plato, the cognitive dimension of resilience is built by integrating the maieutic method and honing critical thinking skills, while the emotional dimension is fostered via the good life example of the instructor that inspires the learner to learn. Responsibility towards others is omnipresent in Plato’s epistemology, as it is the basis of virtue that leads to happiness.

4.2. Aristotle (384–322 BC) and Aristotelianism

Another ancient Greek innovator, Aristotle, follows the example set by Socrates and Plato, since he also believes that virtues are the quintessence for a fulfilling life. But, in contrast to them, Aristotle moves away from the Platonic philosophical theory and delves into empiricism. Whereas Plato believed truth was found within the mind and had a more idealistic approach on education, Aristotle looked to the world outside the mind to find evidence of what was true and gave a realistic approach on education. He believed knowledge is ultimately based on perception. Aristotle was the first to introduce a holistic philosophical system incorporating science, moralism, reasoning, aesthetics, ontology and politics. In addition, he was also the first to introduce reasoning as a discipline and to believe the pursuit of rational thought as humanity’s absolute purpose. Aristotle introduced the concept of the “golden mean”, the intermediary space, between two poles. The concept of teleology is another pillar of Aristotelianism; the belief that all things are planned for or guided towards a final outcome or intention.

Aristotle’s essays on ethics {particularly the “Nicomachean Ethics” (Aristotle, Citation2014) and the “Eudemian Ethics” (Aristotle, Citation2012)depend on the concept that ethics have a practical dimension; if an individual wishes to be virtuous, he must be committed in conducting virtuous actions and not only philosophize about ways to attain virtue. He emphasized that man is a logical being, and that virtue is developed when logic is being properly practiced. He advocated the characteristic Aristotelian virtue of practical knowledge which is bisected in two segments: “Techne” (expertise, competence) and “Phronesis” (enlightenment, judgement). The distinction between Techne and Phronesis focuses on the sense of the relationship between the aim and the required means to attain it. While technical competences enable us to achieve aims outside the action, phronetic knowledge helps us attain aims that are integral to the action (Shlomo, Citation2002).

According Aristotle’s epistemology, the purpose of “Quality Education” is to live a life of happiness, which should also be the main goal in one’s life. Aristotle claims in the preface of book viii of Politics (Aristotle, Citation1995) that education is a requirement for implementing virtuous actions and therefore is a social issue. Education is required for man to complete the process of self-realization; it is a continuous and lifelong process through which virtue is acquired. He categorized the concept of virtue into two parameters: 1) the moral virtue (goodness of character), that doesn’t arise by nature, but is the result of reasoning, persistence and habit, and can be perfected when adapting social conventions and proper behaviour, and 2) the intellectual virtue (goodness of intellect), that is the result of teaching and a product of learning, experience and good judgment, which finally enable us to attain truth. Curren (Citation2010) argues that Aristotle regards moral virtues as declarations of the illogical segment of the mind and as the groundwork for the emergence of intellectual virtues. Aristotle believes that all should be directed at the emergence of the psyche’s intellectual virtues—the “best part” of humanity, whose thriving is essential to a fulfilling life. In the closing chapters of Book VII of the Politics, Aristotle affirms a unity of virtue hypothesis, stating that there are complementarities between wisdom and virtue. No virtue could be a true virtue unless it is driven by wisdom, and nobody will develop wisdom while not having acquired natural or habituated types of virtues (ibid).

Concerning Aristotle’s practical aspects of “Quality Education”, it is an instruction that emphasizes on memorization of facts and development of key competences. Aristotle believed that students should enhance their critical thinking and scientific skills via inquiry learning and that the curriculum should be systematic and focused on a scientific discipline. Aristotle defines teaching as Techne. Techne presupposes four dimensions of knowledge: (a) “practical theory” which includes the principles linking the objectives with the means in a distinct discipline, (b) “a process of deliberation”, which looks at the proper methods for accomplishing the objectives in the particular parameters of the specific circumstance (c) “practical Nus” which allows an individual to speculate the effectiveness of an idea or action; “practical Nus” is enhanced by practice and (d) proficiency skills which refer to distinct competences. Therefore, Aristotle believes that “Techne” is not about applying theoretical knowledge but a kind of autonomous knowledge acquired from practice throughout the individual’s life experience. It could be argued that “Techne” shares similarities with the recent Competency Based Education (CBE) approach which allows students to develop a skill based on their own pace and context. In the Aristotelian theory, resilience is built by integrating “Techne” and “Phronesis”. “Techne” would refer to the cognitive dimension, while “Phronesis” to the emotional dimension of resilience. Responsibility towards others is reflected via conducting virtuous actions, which lead to wisdom.

The Aristotelian theory of logic was prevailing until 19th Century where there was an advancement in mathematics. In addition, the Aristotelian idea of teleology seems to have influenced Immaneul Kant, Georg Hegel and Karl Marx. What is more, in recent times, there is a revival of Neo-Aristotelian approaches. Aristotelian ideas about human flourishing, character and virtue have influenced many current educationists who have tried to import them into the moral education discourse (Kristjánsson, Citation2015). Aristotle’s impact is also apparent to character education, to motivational externalism psychology, to contemporary moral education and to developmental neuroscience.

4.3. René Descartes (1596–1650)

Descartes was a mathematician, scientist and French philosopher and is generally regarded as the “father of modern philosophy”. He lived after the period of Renaissance during an extended period of inactivity in philosophy due to the influence of the church. Descartes epitomizes a separation with the prevailing theories at the time, the Aristotelian and Scholastic theory. Descartes disaffirmed the separation of corporeal substance into matter and form and he also disaffirmed any impact of metaphysical means in understanding natural phenomena (Carlson, Citation2001).

Descartes’ rejection to approve the authority of others philosophers and his firm conviction to only believe what is obviously observed without any questions is at the root of his theory. Descartes believed that the aim of education is to question everything. Descartes with his philosophical theory of doubt assumed that the process of acquiring knowledge should entail the questioning of beliefs that represented “the most perfect certainty” (Newman, Citation2019). The main “certainty” that derives from his theory of doubt is the beinghood of the self, reflected on the phrase “I think; therefore, I am” (“Cogito, ergo sum” in Latin). Descartes believed that the theory of doubt is the “correct path” for anyone to acquire true knowledge (Bicknell, Citation2003, p.33). In the Discourse on the Method (Descartes, Citation2006), Descartes was the first to refer to dualism; he related the mind with one’s self-awareness and separated it from the brain, which is the physical reflection of the mind. He concluded that mind and body were two very different and separate things. He, also, argues, that mathematical reasoning can be regarded as a model for progress in human knowledge.

Descartes in the Preface of the French edition Principles of Philosophy describes the image of a tree to debate about which type of knowledge is important. Descartes states that “the whole of philosophy is like a tree whose roots are metaphysics, whose trunk is physics, and whose branches, emerging from the trunk, are all the other sciences, which may be reduced to the three principal ones, namely, medicine, mechanics and morality”. Descartes states that, “by morality I understand the highest and most perfect morality which presupposes a complete knowledge of the other sciences and is the ultimate degree of wisdom” (1973–76, IXb, p.14). Descartes defines this ultimate degree of wisdom as “Perfect Knowledge”, which is recognized in terms of doubt: “there is conviction [persuasio] when there remains some reason which might lead us to doubt, but knowledge [scientia] is conviction based on a reason so strong that it can never be shaken by any stronger reason” (24 May 1640 letter to Regius, AT 3:65, CSMK 147 cited in Newman Citation2019). Descartes’s tree has three main branches which symbolize “applications of our knowledge to the external world, to the human body, and to the conduct of life” (Finkle, Citation1898, p. 194). According to Finkle (Citation1898), Descartes considers mathematics and science more important from an education directed at arts. Descartes believes that it is the responsibility of every man to examine the supposed realities of the world (Baird & Kaufmann, Citation2003). In this way, one is responsible for his/her learning and becomes his/her own instructor. Nevertheless, Descartes believes that sometimes a person who has more experience can have the role of a “mediator” to assure that the questioning method is on the right path. Descartes retrospects on the school years of his Jesuit education and concludes that he has learned more from sciences when he was elder and able to think for himself than from the arts and the process of strict, guided learning, stating that arts and learning are futile “unless something tangible could be extracted therefrom” (Finkle, Citation1898, p. 194). It could be therefore claimed that “Quality Education” for Descartes starts with a curriculum based on metaphysics; since he believes that metaphysics is the cornerstone for understanding mathematics and science. Descartes would opt for a self-directed learning where learners would acquire knowledge via creativity activities that allow for discovery learning and critical thinking. The teacher would follow the learning pace set by the student and would only intervene in case the student misinterpreted phenomena and data. The content of the curriculum would be connected with reality and the physical world. For Descartes the cognitive dimension of resilience is built via the knowledge of sciences and mathematical reasoning. The emotional dimension of learning is not explicitly framed, but it could be argued that his theory of doubt reinforces the quest of learning by strengthening thinking skills; responsibility towards others is reflected via “Perfect Knowledge” and its application to the “conduct of life” (Finkle, Citation1898, p. 194).

Descartes introduced Cartesianism or the 17th century rationalism that was later advocated by Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz (Moorman, Citation1943). Descartes’ concept of education has similarities with the one of John Dewey.

4.4. John Locke (1632–1704)

Locke was one of the leading representatives of British classical empiricist epistemology and liberal thought. He was a physician and an academic and is considered to be one of the most inspirational Enlightenment philosophers. Contrary to the Cartesian philosophy, Locke postulated that knowledge is determined by experience and observation. Locke’s main separation point from Descartes and other contemporaries was the importance he gave to the senses as an essential source of knowledge. On the other hand, Descartes argued that we are motivated by the senses to have certain convictions, but these convictions alone do not consist of “Perfect knowledge”.

Locke’s educational thoughts are dispersed in many of his works. Τhe first stimulus to develop his educational philosophy are found in the letters he wrote in 1693, while he was exiled, in response to the quest of his cousin and her husband to offer them his insights on their son’s education. In these letters, which were later published in the book Some Thoughts Concerning Education (Citation1970) Locke introduces the “tabula rasa” concept for the human mind; that is, an absence of preconceived ideas; a clean slate when a human is born. The “tabula rasa” concept presupposes equity between humans and the capacity for each individual to develop his/her personality and mind. This book is considered to mark a new era on “the discovery of the child”, since in medieval times a child was considered “only a simple plaything, as a simple animal, or a miniature adult who dressed, played and was supposed to act like his elders … Their ages were unimportant and therefore seldom known. Their education was undifferentiated, either by age, ability or intended occupation” (Axtell, Citation1968, 63–4). Locke encouraged parents to steadily foster the strengthening of their children’s logic. He motivated parents to face children as human beings, to share time with them by responding to their needs and personal traits as to develop a strong body and mind, to play with them and not to punish them (Locke, Citation1947). Locke advocated for the importance of helping them develop good judgment and values rather than memorizing content. He stretched the importance of cultivating values as “justice as respect for the rights of others, civility, liberality, humanity, self-denial, industry, thrift, courage, truthfulness, and a willingness to question prejudice, authority and the biases of one’s own self-interest” (Grant & Tarcov, Citation1996, xiii). Locke commented on the dressing, nutrition, teaching, learning, exercise and assessment of children (Baldwin, Citation1913, 186). He wrote about the importance of a good and mutual relationship between child and teacher (Baldwin, Citation1913, 184). Locke’s idea of “associationism” found in his work Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Citation1847) encourages parents to safeguard their children from creating negative inferences that could impede their quest for learning (Yolton, Citation1971, 28–29). Locke was against scholasticism and disciplinarian methods. Locke noted that play motivates students to learn and should be integrated in the learning process (ibid 84–85).

Consequently, Locke’s theories of “tabula rasa” and “associationism” suggests a conception of “Quality Education” that would advocate for a curriculum based on approaches that foster self-realization through experimentation as for children to develop their own moral systems and critical thinking. Play would have a central role as an igniter of inner motivation to learn. Student-teacher relationship would be based on two way trust and respect. For Locke, the cognitive dimension of resilience is fostered via the strengthening of the child’s logic by the use of their senses, while the emotional dimension, the inner motivation to learn is cultivated via approaches that foster self-realization. Responsibility towards others is developed through experimentation of right and wrong as for children to develop their own moral systems and values. Locke’s influence in education is, also, clearly stated in Peter’s Gay comment that “John Locke was the founder of the Enlightenment in education as in much else” (Gay, Citation1964). Though, his denouncement of classical education provoked reaction at his time, his belief in experiential learning and the integration of play in the learning process makes him an early predecessor of progressive education.

4.5. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778)

Rousseau in his educational novel Emile (Citation1911) explains the ways to prepare an ordinary boy for adulthood. Rousseau, a Swiss born philosopher, believed that man is born with an innate kindness but is corrupted by the education he receives and by society. Rousseau believed that living in nature develops man’s reasoning and virtues. This is why, in Emile the boy lives in the countryside and with the guidance of his teacher. Emile aims to describe an educational system that could develop the ideal citizen where the educational process must respond to the intellectual needs of the learner and to his age.

Rousseau’s philosophy of education is Naturalism. Naturalism considers parents to be the ideal instructors of their child. Naturalism’s principles aim at a naturalistic education, pleasurable and attractive to the children, responding to the child’s nature, acquisition of knowledge, intellectual and physical development, inductive approaches, corrective actions only as response to mistakes (Butler, Citation2012). Rousseau’s philosophy and works have influenced, among others, Pestalozzi, Montessori and Dewey.

The ideas, both of Locke and Rousseau, that human nature is good and all people are equal, have influenced the humanistic approaches in learning. In this sense, “Quality Education” for Rousseau must be adapted to the preconditions of the child, since education is directly linked to the perceptions, needs and prior knowledge of each learner. According to Emile, “Quality Education” is meant to be attractive to the learner and to embrace the nature of the child. The learning process is defined by the child and not by the teacher or any other external source. “Quality Εducation”, based on Emile, would also mean that learners construct their own meanings, there are no prescribed curricula, the teacher’s role is to facilitate learners to reach their full potential, parents’ role is crucial, the values of kindness and citizenship are prevailing. For Rousseau the cognitive dimension of resilience is set by the personal interests and learning pace of the child, the emotional dimension is set by nature, the example, guidance and support of parents. Responsibility towards others is expressed via kindness and good citizenship values.

4.6. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

Immanuel Kant is considered to be one of the greatest philosophers of all times. He is widely held to have synthesized rationalism and empiricism by forming the doctrine “transcendental idealism” in his work Critique of Pure Reason (Kant, Citation2003).

Kant’s practical philosophy is related to his ideas on moral law, virtue, dispositions and judgement. He believes that human beings should promote general and not merely personal happiness; and that education is the means that enable humans to cultivate themselves in order to promote the highest good, that is happiness, and make moral perfection their final destiny. In the book Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (Citation2006) Kant acknowledges education to be the most important confrontation of all times. In 1776 when writing in an academic journal, Kant presents his opinion for the “Philanthropin” institute in Dessau, to which he attributed an unconventional, broadminded and sophisticated importance that will lay “the foundations for a whole new order of things”. Kant is likely the first philosopher to talk about student as “citizen of the world” (Kant, Citation1963, 61), to predict the major changes that education will encounter and to attribute global characteristics in education when he speaks about the “Philanthropin” Institute in Dessau which admirably exemplifies an “early revolution” in reforming schools (ibid). Kant attributes a major role in educators and he remarks that the “Philantropin” constituted an educational institution “in which the teachers were free to work out their own methods and plans, and in which the teachers were in communication with each other and with all the learned men of Germany” (Kant, Citation1960, 19).

Kant finds education to be the most important factor for the evolution of humanity and it is seen beyond the individual traits of every human being and every nation (Kant, Citation1963). Kant argues that education should include the following: “(a) structured reasoning; (b) development of a sophisticated judgement; (c) improvement of the society; and (d) development of moral values” (p. 16). He thought that education at his times covered in a way the first three elements but not the fourth; he claimed that “moral rectitude still lies in the distant future” (p. 17). Based on Kant’s beliefs, moralization denotes that every individual should cultivate some principles so as to opt for “good purposes only, which necessarily secure universal approval and may at the same time be the purposes of everyone” (p. 17). Kant believed that children’s education must be oriented towards fulfilling their obligations towards themselves and others. Kant relates his philosophical concept of categorical imperative with the development of the qualities of a global citizen and with a universal moralism. Kant advocates that education makes an individual important for himself/herself, practical education makes him/her important for the society in which he/she lives and moral values makes him/her important for humanity. In this way, men’s and women’s actions make them responsible for the future of mankind and emplaces them all in an equal status. Kant discusses the ways children can learn and gives an important role to play, to discovering knowledge by themselves and to honing their critical thinking skills via disciplined thinking (Kant, Citation1963, 16). Kant acknowledges that “The principal need is to teach children to think” (ibid, 40) as a way to exploit in the best possible way their freedom for themselves and the others. Children should be trained from a young age towards understanding their responsibility towards others, since “Adopting a particular course of action from a sense of duty means obeying the dictates of reason” (Kant, Citation1963, 46). Kant argues that the Socratic Method must be the basis for all learning and denounces methods based on memorization. In addition, Kant utilized conventional methods for the learning process like observation, use of literature and insights of important men of his period. During his university lectures he acted as a mentor to his students.

Based on his intellectual undertakings and published work (Citation1963, Citation2003, Citation2006), “Quality Education” for Kant presupposes his influence on discourse around equity in education, peace and citizenship education. Based on his ideas (Kant, Citation1963, p16) Kant’s purpose of “Quality Education” is to empower disciplined thinking, to acquire a cultivated perspective of the world that would enhance civilization and impart moral values. Kant would opt for a curriculum that would rely on observation methods and inductive teaching approaches, but would also integrate the enlightened views of other philosophers and literature masterpieces to provide a broad view of a future world ethic. The teacher’s role would be the one of a mentor who imparts moral values, hones the ability to think and questions the best use of freedom towards oneself and the other. The idea of duty is central in Kant’s learning process and liaised to disciplined thinking, reasoning and freedom. Inclination, interest and “joy of the heart” (ibid, p59) are an integral part of the learning process provided that they do not impede the learner’s commitment on the well-being of all men. For Kant, the cognitive dimension of resilience is based on inductive approaches of learning and on observation, while the emotional dimension is set by the example of educators and the enlightened views of philosophers and literature masterpieces. Kant’s epistemology integrates responsibility towards others via the role of the educators that imparts moral values and the sense of commitment on the prosperity of mankind. Kant’s work is esteemed to have influenced all scientific fields. His work has influenced the work of the sociologist Max Weber, the psychologist Jean Piaget, the linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky and the work of Albert Einstein (Issackon, Citation2007).

4.7. John Dewey (1859–1952)

John Dewey was one of the most progressive American philosophers. His ideas were linked with the philosophy of pragmatism and progressive education. Pragmatism advocates that reality must be experienced, while progressive education emphasizes the importance of learning by doing. In his work School and Society (Dewey, Citation1900/1985), Dewey explains the reasons why education should be completely reconstructed. Dewey (ibid, 17–19) sees “an education dominated almost entirely by the medieval conception of learning”, he remarks that “our social life has undergone a thorough and radical change” and he states that education “must pass through an equally complete transformation” in order to have a vital part in contemporary society. In Self-Realization as the Moral Ideal, Dewey affirms that “the most needed of all reforms in the spirit of education” would be to “[c]ease conceiving of education as mere preparation for later life, and make of it the full meaning of the present life” (Dewey, Citation1893, 50).

In Democracy and Education (Dewey, Citation1916/1985), Dewey expresses his view that education is about helping everyone to grow and acknowledges that each individual has a potential that will not be activated unless he/she has “opportunities to employ his own powers in activities that have meaning” (ibid, 179). Dewey advocates that education as growth includes two main goals. The first goal is to learn how to think and solve problems and, the second is to inspire the desire to never stop learning. Starting with the former, if our educational goal is personal development, the focus should be placed on honing children’s thinking skills and not merely to gather data. According to Dewey the only obligation the school “can or need do for pupils, so far as their minds are concerned … is to develop their ability to think” and this can only be achieved by engaging learners in problem solving. Dewey describes a learner-centered approach where the teacher acts as a facilitator of learning, he guides learners towards the path of their educational growth. “The educator’s part in the enterprise of education,” he notes, “is to furnish the environment which stimulates responses and directs the learner’s course” (ibid, 188). A major concern in Dewey’s Education as Politics is to provide equal voice to all children in the classroom to enable them “to discriminate, to make distinctions that penetrate below the surface” so that every child will “take charge of himself” become adjusted “to the changes which are going on” and “to shape and direct those changes” (Dewey, Citation1922/1985; 329). These are the preconditions for an “effective self-direction” as Dewey remarks in his work School and Society (1900, 20 cited in Campbell, Citation2016).

For Dewey the crucial role of education in a democracy is to assist learners in developing their personality, the traits and values, that would “create an interest in all persons in furthering the general good, so that they will find their own happiness realized in what they can do to improve the conditions of others” (Dewey, Citation1932/1985, 243). Dewey believed that a school should be organized as a collaborative community to foster social spirit and develop a democratic character in children that would make “school life more active, full of immediate meaning, more connected with out-of-school experience” (Dewey, Citation1916/1985, 325). To do this, Dewey proposed a form of vocational training, introducing the concept of “hands-on” activities, and an interdisciplinary curriculum. Dewey believed that education and democracy were substantially interrelated: “democracy and education bear a reciprocal relation, for it is not merely that democracy is itself an educational principle, but that democracy cannot endure, much less develop, without education” (Dewey, Citation1938a, 92).

Dewey’s work (Dewey, Citation1900/1985, Dewey, Citation1893, Dewey, Citation1922/1985, Dewey, Citation1916/1985, Dewey, Citation1932/1985, Dewey, Citation1938a, Dewey, Citation1938b) advocates that the purpose of “Quality Education” would be to inspire learners to learn, to think on their own and to promote the general good. For Dewey, “Quality Education” would presuppose a learning community where every child is given the chance to develop his full potential, makes his voice heard, participates in problem-solving activities by making use of many different approaches, takes responsibility of his/her learning and demonstrates an honest interest in the well-being of all other individuals in the community. The curriculum would be interdisciplinary and active learning methods would be employed. In this learning community, there would be no distinction between teachers-learners, they are all peers, working together, facilitating one another and experiencing the ups and downs of the learning process. For Dewey, the cognitive dimension of resilience is based on hands-on activities that develop the ability to think, while the emotional dimension is fostered by inspiring the desire to learn via experiential activities that have meaning. Dewey seems to introduce the concept of relevance by emphasizing the importance of activities that have meaning and are linked to real life as to inspire learners to learn. The importance of resilience is evidenced in Dewey’s epistemology via the ability of learners for “effective self-direction”. Responsibility towards others is omnipresent in Dewey’s epistemology, since for Dewey the crucial role of education is to “create an interest in all persons in furthering the general good, so that they will find their own happiness realized in what they can do to improve the conditions of others” (Dewey, Citation1932/1985, 243).

4.8. Paulo Reglus Neves Freire (1921–1997)

Freire was a 20th century philosopher from Brazil. Liberty, democracy and critical engagement in society are the main ideas at the heart of his pedagogical thought (Gadotti & Torres, Citation2009). Freire’s pedagogy was influenced by classical approaches as well as modern Marxist and anti-colonialist thinkers. Plato’s influence is mostly reflected in Freire’s work with his involvement in adult education and the great emphasis he gives in the power of dialogue, what he calls “circle of culture”. In this education scheme, Freire disclaims the teacher—learner polarity and suggests a mutual relationship based on dialogue and respect of the other. He rejects the role of the teacher as “the only true knowing” (Freire, Citation2004, 64) in favour of a facilitator of the learning process who has a deep faith in students and guides them to rise above any barriers of the learning process as they understand their limitations to explain facts. Instead of a predetermined curriculum, Freire favors a flexible curriculum developed by the learners. In the Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, Citation1972), Freire criticises the “banking” notion of education where the learner is faced as a void vessel to be loaded by the educator. Freire viewed learners as co-creators of knowledge and agrees with Rousseau’s idea of the child as an engaged learner and not as “tabula rasa”. He believed “education makes sense because women and men learn that through learning they can make and remake themselves, because women and men are able to take responsibility for themselves as beings capable of knowing—of knowing that they know and knowing that they don’t” (Freire, Citation2004: 15).

Viewing teaching and learning as political acts, Freire was concerned with the question of learning for personal growth, and particularly the ways to connect personal learning with citizenship education (Gadotti & Torres, Citation2009). In the Pedagogy of Freedom (Freire, Citation2000), Freire discusses the significance of openness, acceptance, equity, humility, commitment and poses questions of morals, values, aesthetics, education and politics. In this work, Freire claims that any form of discrimination is not moral and seems to be referring to the current concept of equity in education. Learning, he believed, in no way can be separated from examining and thinking on the ways society functions, and educators must expand the thinking capacity of their students to analyse the social and political facts of the world (Jackson, Citation2007). “Education for development” should be an “education that makes it possible for people to fearlessly discuss their problems” (Freire, Citation1972: 84), “that is situated in dialogue” (ibid: 85) and “makes it susceptible to a kind of rebelliousness” (ibid.). This popular rebelliousness must be converted into “engineering”, since Freire persists that his “Education for development” “is identified with scientific methods and processes” (ibid.). In addition, education should “help people reflect about their ontological vocation as subjects” (ibid: 52). In the Pedagogy of Indignation (Freire, Citation2004), Freire describes neoliberalism as the use of knowledge for the benefit of industrialism and admonishes that “the more education becomes empty of dreams to fight for, the more the emptiness left by those dreams becomes filled with technique, until the moment comes when education becomes reduced to that. Then education becomes pure training, it becomes pure transfer of content, it is almost like the training of animals, it is a mere exercise in adaptation to the world” (ibid, 84). For Freire, a “rebellious”, “humanizing” education that can transform the world must be driven by hope and dreams: “What I mean to say is this: To the extent that we become capable of transforming the world, of naming our own surroundings, of apprehending, of making sense of things, of deciding, of choosing, of valuing, and finally, of ethicizing the world, our mobility within it and through history necessarily comes to involve dreams towards whose realization we struggle” (ibid, 7).

The practical aspects of what “Quality Education” entails for Freire are found mostly in the Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, Citation1972) and in the Pedagogy of Indignation (Freire, Citation2004). “Quality Education” for Freire presupposes a curriculum, developed by the learners, which takes into account their prior knowledge. The teacher would be a facilitator of learning. The learning would take place in a community where an ambience of trust would be prevailing and the teaching methods would initiate active participation of all learners. The learners dare to try new things, to discuss any issues without fear, embrace their mistakes and learn by them, they never cease learning. The ultimate aim of education is to always try to change things for the better especially for those that may be not be able to defend their own rights. There is a strong sense of equity and responsibility to humanity. The pursuit of education is a constant struggle towards the self and the world, a struggle where hope prevails and this is why the struggle never ends (Freire, Citation2000, Freire, Citation2004). The concept of “Quality Education”, as prescribed in this article, with the attribute of “resilience” and “responsibility towards others” is reflected in Freire’s “education for development”. The cognitive dimension of resilience is developed via engagement of every learner with “scientific methods and processes” (Freire, Citation1972, 85), while the emotional dimension is fostered via the “circle of dialogue”, a community of trust where every individual is enabled to make sense of things, decide, choose, value in order to transform the world (Freire, Citation2004). The sense of responsibility towards others is dispersed to all his works, as for Freire, the purpose of “education for development” and “Quality Education” is to transform the world and to make it better for the underprivileged.

Freire is the founder of the Critical Pedagogy, which had a deep influence on the pre-service and in-service training of teachers around the world. His work Pedagogy of the Oppressed, inspired the emergence of comparative and international educational studies. Freire’s work influenced Carl Rogers, Lev Vygotsky and John Dewey. UNESCO’s Global Report of Adult Learning and Education-GRALE (UNESCO, Citation2016) highlights Freire’s contributions to adult learning.

4.9. Mapping the dimensions of the Philosophers’ Approach

Figure brings together the conceptual framing of “Quality Education” that build towards resilience and the acceptance of responsibility towards others for Platon, Aristotle, Descartes, Locke, Rousseau, Kant, Dewey and Freire. The main stances of the philosophers/thinkers are frequently apparent in the curricula of contemporary educational systems across the world either as values embedded in the curricula to be embraced by learners or as teaching and learning practices to be implemented within the classrooms.

5. The theories of learning approach

This section presents six learning theories; behaviorism, cognitivism, (social) constructivism, transformative learning, critical pedagogy and connectivism. Behaviorism, cognitivism, (social) constructivism are examined as they are the primary learning theories. Transformative learning is explored as it is linked with teacher education. Critical pedagogy is viewed, as it is liaised with the notions of equity and social justice and with invisible factors that could build the sense of responsibility towards others. Connectivism is examined as the most recent learning theory strongly associated with the changes that the digital era brought to education and the way learning is acquired. First, the main stances of each learning theory are presented, along with a short critic. Then, each learning theory is related to the concept of “Quality Education” as prescribed in this article: the inner motives and the emotional dimensions that inspire to learn, continue learning, and build resilience and the sense of responsibility towards others. There is a reference to the dimensions “Quality Education” encompasses for each learning theory, namely knowledge construction in curricula and classrooms, structure and content of curricula, the role of the educator/teacher, the role of the learner, student-teacher relationship, teaching methodologies, learning and assessment methods.

5.1. Behaviorism

The behaviourist theory of learning emerged in the 19th century and became influential in the early 20th century; it comes as an opposite theory to humanistic approaches. Behaviourism assumes that learning consists of a change in behavior through associations between stimuli from the environment and observable responses of the individual. An individual selects one response instead of another because of prior conditioning and psychological drives existing at the moment of the action (Parkay & Hass, Citation2000).

Edward Thorndike was the first to talk about the “law of effect”; he evidenced that a response to a stimulus is reinforced when followed by a positive rewarding effect and it becomes stronger by exercise and repetition. Another principal behaviorist was John B. Watson who focused his ideas on learning on the studies of Ivan Pavlov. Going beyond Watson’s stimuli-reactions model, B.F. Skinner proposed a more holistic type of conditioning, including two types of conditioning “respondant” and “operant conditioning” (Skinner, Citation1968). “Respondant” conditioning involves an operation where the individual reacts to extrinsic stimuli while “operant” involves the betterment, augmentation of a reaction through punitive/rewarding measures that make new learning happen and/or stop previous unwanted behavior. In Behaviorism learning is understood as the successive approximation of the intended partial behaviors using reward and punishment. Behaviorism doctrines (Honig and Fetterman, Citation1992, Mahoney Citation1974, Meichenbaum Citation1977) that learners cannot discover knowledge by themselves and they do not have interior learning incentives; punitive and reward methods can change the behavior of an individual; learning takes place when observable reaction is changed through control and the use of punitive and reward methods; repetitive tasks, drill exercises, memorization, tests and deductive methodologies assist in changing learners’ behavior and in this way learning is achieved (Skinner Citation1968). Some of the critics of Behaviorism involve the denial of free will and of the social dimensions of learning, the implication that what happens in animals is the same with humans, the lack of self-regulation and the undermining of intrinsic motivation and critical thinking skills.

Therefore, behaviorist theory indicates “Quality Education” that presupposes the existence of standardized curricula based on prescribed objectives and assessment and tests that have the most important role in defining the learning methods. The behaviorist educator is the expert who controls stimuli and responses and makes the decisions about learning (UNESCO, Citation2005). Teaching methodologies would be deductive and traditional with tasks that focus on rote learning and repetition. The role of the student is mostly passive, as he/she has to practice what the teacher proposes. The teacher adapts the learning content based on the student’s progress towards prescribed learning objectives. Behaviorism is more concerned with changing behavior than with deepening thinking, learning facts and developing skills is more important than understanding. In behaviorism, rewards are means to form desired behaviors. Breaking learning into parts and teaching and testing these parts separately is the best way to teach a complex skill. Behaviorism focuses on the cognition part of the learner, while it is not evident how behaviorism inspires the inner motivation to learn and continue learning. In this sense, it could be stated that behaviorism fails to develop resilience, as the emotional dimension of learning is neglected. Similarly, it does not cover the “responsibility towards others” dimension. Although the majority of educators do not embrace behaviorism in all its details, features of behaviorism exist in teacher education both in pre-service and in-service programmes, in school syllabuses in many disciplines (i.e mathematics, language, foreign language, music, chemistry, physics etc) from primary education to high schools, and most importantly in the ways educators teach in their classrooms worldwide even today (Jarvis, Citation1983, 61). It seems that overly intense accountability and assessment policies increase the use of behaviorist practices in schools, since teachers, leaders and education systems often fall back on a more behaviorist approach when they are under pressure and stress.

5.2. Cognitivism

Cognitivism came as a reaction to behaviourism and made its appearance in the 1950s. Cognitive psychologists use observable behaviors as an indication for deducing what is going on in a person’s mind (Gage & Berliner, Citation1988). They lay emphasis on the multiple ways the brain functions during the learning process. Hence, cognitive psychologists give to the learner’s mental capacity a dynamic and developmental role and not a static one (Reid, Citation2005). Cognitive theory usually relates to the role of information processing; new information should be clearly explained and thus easily perceived and stored. The aspects involved in processing such as memory, organization and neurological connections are viewed as central in cognitive theories, since they keep the learner’s attention and activate his/her mental processes. J.S Bruner, who made a significant contribution to cognitive learning theory, introduced the notion of “scaffolding” to refer to the way learners construct their cognition by mounting the new knowledge they acquire to previous knowledge. Cognitivism emphasizes ways of interpreting information, memorization, transferring knowledge, enhancing metacompetences, fostering understanding via demonstrations, illustrative examples, animations, and digital simulations. Other pioneering cognitive theorists are J.R. Anderson, D. P. Ausubel, B. Bloom and R. M. Gagné. Cognitivism has received criticism on assuming that internal information processing is the same for all individuals and ignoring differences based on each individual’s cognitive function.

“Quality Education” for cognitivists would mean engaging learner in all teaching and learning procedures taking place in the classroom. The cognitivist curriculum is spiral and every discipline or competence is readdressed at different times at a more complicated degree; new information is organized in chucks in a structured and comprehensible way to ensure optimal processing; educational goals are subdivided into concrete learning aims and further subdivided into personalized activities; there are clear linkages between prior knowledge and new knowledge; assessment would be based in concrete criteria that could be adjusted to each learner’s potential and individualized learning objectives. The cognitivist teacher ensures that the learner develops transferable problem-solving skills and that is able for a (meta)analysis and deep understanding of knowledge. The teacher observes the understanding, the mental processes of the learner and proceeds accordingly providing the material that is adjusted to his/her needs. The learning material is multigenre. The learning activities aim at fostering understanding. Cognitivism builds learner’s resilience, as it focuses on the inner drives of cognition, it adapts learning procedures to learner’s needs taking into account mental abilities and personal preferences, but the “responsibility towards others” dimension is not clearly addressed.

Cognitivism is related to the emotional dimension of the learning process (Goleman, Citation1995, Ledoux Citation1996), to the linkage between motivation and acquisition of knowledge (Ashman & Conway, Citation1997), to the influence of social interactions on learning and on education policy making (Bruner, Citation1996, Raeff and Benson Citation2003) and to the study of neuroscience and learning.

5.3. Constructivism and social constructivism

Constructivism emerged in the 1970s, it has its premises in cognitive theories and reflects the ideas previously expressed by John Dewey. Its central idea is that human learning is constructed rather than acquired. Constructivism claims that learners are engaged in the learning process by interpreting information and building up their knowledge via social influences, beliefs, experiences and prior knowledge. Constructivism was expanded with the concept of “situated cognition and learning” (Brown et al., Citation1989) that focused on the importance of the social impact and environment and was, also, called Social Constructivism. The various differentiations between theories of constructivism have the same underlying principle that construction of knowledge is an active procedure that presupposes learner’s engagement and an active building up of prior knowledge via mental schemata and social interactions that are unique to every individual. Constructivism is viewed as a learning theory that deals with the mental processes that assist individuals in understanding the subtle and often invisible ways learners build-up their knowledge. Among the influential theorists are Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, Mikhail Bakhtin and Jean Lave. Probably the most important criticism on (social) constructivism is its lack of structure and disregard of the standardized methods and curricula, since some students wish for a stable setting in order to learn.

In constructivism “Quality Education” means that the learner constitutes the driving force for every learning initiative. The teacher guides the learner through the path of understanding the mental processes that help him/her construct knowledge. Therefore, the teacher becomes more of a coach who guides the learner to be autonomous and to take charge of his/her own learning. There is an emphasis on discovery learning, learner’s engagement and motivation, collaborative learning and peer-teaching. A particular value is, also, attributed to the ways students understand facts and physical phenomena. On the other hand, the prior setting of curriculum, educational aims, teaching and learning methodologies, activities and lesson plans is less important; educational goals stem from “situated learning” instances and they come as a response to the learner’s need to understand a concept in a more comprehensive way. Following the same rationale, teaching methodologies, activities and lesson plans are developed as a response to the learner’s quest of knowledge. Implementation of different learning approaches, reflective practice, finding alternative solutions to the same problem, exploiting mistakes to understand the way mental processes work, developing critical thinking skills and most importantly metacognitive skills are of significant importance. Assessment is formative (i.e. portfolios, projects) rather than summative and less circumscribed. (Social) constructivism fosters learner’s resilience, as it focuses on strengthening learner’s motivation for learning and cognition; “situated learning” offers insights from context for “responsibility towards others”.

The concepts “active learning” (Cohen, Citation1988), “situated cognition” (Resnick, Citation1987) and “cognitive apprenticeship” (Collins et al., Citation1989) are applied (UNESCO, Citation2005).

5.4. Transformative learning

The work of remarkable thinkers like Thomas Kuhn’s (Citation1962) “paradigm”, Paolo Freire’s (Citation1972) “conscientization” and Jurgen Habermas’s (Citation1971, Citation1985) “domains of learning” had an impact on Jack Mezirow’s theory of transformative learning. Mezirow presented his theory in 1978 and has since expanded “into a comprehensive and complex description of how learners construe, validate, and reformulate the meaning of their experience” (Cranton, Citation1994, p. 22).

Mezirow believes that transformative learning is the essence of adult education that is “to help the individual become a more autonomous thinker by learning to negotiate his or her own values, meanings, and purpose rather than uncritically acting on those of others” (Mezirow Citation1997, p. 11). For adults to modify their “meaning schemes” (convictions, behaviors, frame of minds and expression of emotions), “they must engage in critical reflection on their experiences, which in turn leads to a perspective transformation” (Mezirow Citation1991, p.167). A “perspective transformation” leading to transformative learning, however, requires many different stages, a deep understanding of oneself and may take place in two distinct circumstances. Firstly, it may take place effortlessly via a considerable number of successive transformations in different “meaning schemes” (Mezirow, Citation1985). Secondly, “perspective transformation” can be an “epochal … [and] … painful” (ibid, p. 24) transformation of sets of “meaning schemes”, as this circumstance includes a holistic and perceptive self-reflection. According to Mezirow “perspective transformation” comes from a “disorienting dilemma”, which is activated from one of the two aforementioned circumstances, either due to a considerable number of successive transformations in different “meaning schemes” or a serious problem or confrontation (Mezirow Citation1995, p.50). The 10 phases of transformative learning are presented by Mezirow (Citation1978a, Citation1978b cited in Kitchenham Citation2008) as follows:

“Phase 1: A disorienting dilemma

Phase 2: A self-examination with feelings of guilt or shame

Phase 3: A critical assessment of epistemic, sociocultural, or psychic assumptions

Phase 4: Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared and that others have negotiated a similar change

Phase 5: Exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and actions

Phase 6: Planning of a course of action

Phase 7: Acquisition of knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans

Phase 8: Provisional trying of new roles

Phase 9: Building of competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships

Phase 10: A reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by one’s perspective”

In 1991, Mezirow revised this model by adding an extra phase between the phases 8 and 9, which he described as “renegotiating relationships and negotiating new relationships” (Mezirow, Citation1994, p. 224). This additional phase focuses on the significance of an in-depth self-reflection that originates from the way our “meaning schemes” are confirmed by our interpersonal relationships.

Transformative learning theory has different strands and responds to different contexts. Apart from adult education, it has been employed in many different educational fields such as peace education, AIDS education, citizenship education, social justice and spiritual education (see case studies in Associates, Citation2000 cited in Sifakis Citation2009). It has also been employed in training programs that addressed adults wishing to learn English as a Second Language, in training programs that addressed developing basic literacy and numeracy skills (e.g., Comings et al., Citation2004 cited in Sifakis Citation2009), in training programmes concerning intercultural education, and in pre-service and in-service teacher education programs (e.g., Pickering, Citation2003; Crosby, Citation2004 cited in Sifakis Citation2009). The main criticism Mezirow’s theory has received is that it overemphasizes rationality and self-reflection (Taylor, Citation1998, pp. 33–34).