Abstract

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) adopted in higher education are an impactful topic for the actors directly involved. For this reason, the use and adoption of ICTs aimed at university student learning was examined through a systematic review using PRISMA methodology; this review included 27 articles that met the inclusion criteria. The results showed that the most used factor was the perceived usefulness of ICTs in receiving training. In turn, due to the conditions presented during the pandemic, variables such as fear and technological complexity were prominent to address needs in specific contexts. Thus, students were driven by current conditions, developing, and strengthening digital communication and collaboration skills to meet learning objectives. Among the emerging themes in the subject, elements related to immersive technologies, which include augmented reality and virtual reality, are observed. The results provide theoretical contributions and allow identifying relevant variables for technology adoption, such as attitude towards use, perceived ease, intention to use, perceived usefulness, perceived fear, satisfaction or enjoyment, and technological complexity. These findings have practical implications for formulating models focused on current academic needs and can guide research on technology adoption by higher education students.

1. Introduction

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have become indispensable tools in higher education, and their use helps to promote the execution of various tasks, which is why their development from the theoretical and investigative perspectives has advanced, especially in the last five years. ICTs are developing at a dizzying pace, requiring social responsibility on the part of basic, middle and higher education institutions. There has been a need to include ICTs in education, generating processes of reflection from the perspective of the different educational methods and levels in each professional training program, involving participants in new scenarios and learning environments, and incorporating derived policies of ICT integration (Sánchez, Citation2016).

The use and adoption of ICTs is important in regard to educational innovation and continuous quality improvement in schools. This integration and use of ICTs is part of a global trend in the knowledge and information community, where education at all levels is in some way involved, faced with cultural and social pressure that forces ICT participation to improve the educational processes of teaching and learning in higher education institutions (HEI) (Ancira & Gutiérrez, Citation2011; López, Citation2019), especially for the development of technical, technological and scientific skills that are influenced by the way these tools are implemented (Fernández-Gutiérrez et al., Citation2020).

In turn, virtual education has grown exponentially in recent years worldwide, and the appearance of new ICTs, the increase in transaction and exchange speed, knowledge management and other conditions have influenced HEIs to promote strategies that scale up and modernize and create flexibility in training processes (Naffah et al., Citation2016; Simó et al., Citation2020). These strategies have been accelerated by the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in most public institutions and private companies of greater size and scale quickly beginning to provide their services through digital media, allowing various levels of quality and support in learning and continuity in educational processes (Rama, Citation2021).

Therefore, it is necessary to carry out research to identify studies that define strategies, models, methodological approaches, and variables that intervene in the use and adoption of ICTs oriented to university student learning. In this work, a systematic literature review (SLR) is carried out, allowing the identification of various topics of interest and a concise understanding of the current state of literature and the identification of the most important factors that will lead to the development of the subject in the future (Abelha et al., Citation2020). In an SLR, strategies are used that limit biases and random errors to guarantee validity or veracity, methodological quality, and reliability or reproducibility of results (Manterola et al., Citation2013).

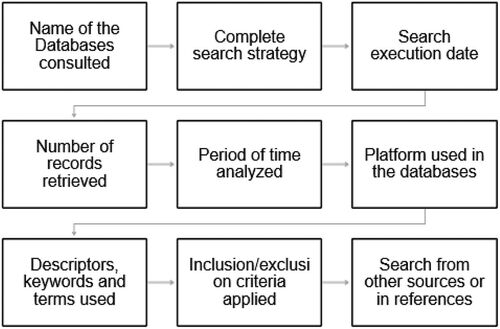

For this review, the guidelines of the PRISMA statement (Urrútia & Bonfill, Citation2013) have been followed, complemented with a systematic methodology that allows extracting the most relevant information from the literature in a certain field that responds to a research question or objective. The quality criteria were reviewed (see Figure ) to guarantee that the SLR contains all the information considered necessary for the methodology to be reproducible (Salvador-Oliván et al., Citation2018).

Figure 1. Quality criteria applied to the SLR. Taken from Castro et al (Castro et al., Citation2019).

Next, the SLR development process and its different stages, starting from the initial search and the systematic search to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and, ultimately, the results, are detailed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Initial search

This stage consisted of defining the strategy to develop the search in the databases. An initial review was carried out to explore the topic of study and identify whether it had bibliographic production and whether there was research aimed at some of the needs that would serve as a basis for the proposal of the questions to be answered in the review. The first searches were carried out in May 2021 combining the terms “adoption” and “ICT” in the Scopus database. Subsequently, the combination was expanded using the Boolean operators AND and OR as appropriate for the study. In addition, the keywords, databases and inclusion and exclusion criteria to be used (Aleixandre-Benavent et al., Citation2011; Castro et al., Citation2019) were defined, following the guidelines of the PRISMA statement (see Figure ). For this section of the study, the following questions were posed:

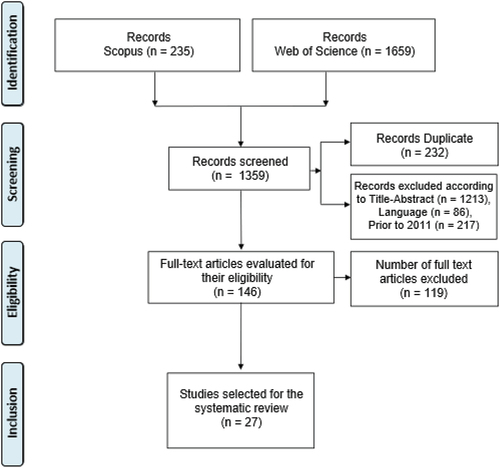

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram.

What variables or factors have been used in the adoption of ICTs in higher education that can help students learn?

Which models of ICT adoption are the variables identified associated with?

2.2. Systematic search

The systematic search was carried out again in May 2023 in Scopus and Web of Science because they are considered within the main international databases and have been used in other systematic literature reviews. In addition, they contain a volume of publications and concentrate high impact published articles (Castro et al., Citation2019; Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Citation2016). This selection was considered appropriate in accordance with the defined quality criteria because the existence of at least two databases avoids the possible omission of relevant studies (Salvador-Oliván et al., Citation2018).

To give continuity to the systematic search, the keywords of the topic of interest to be analyzed were established, and their synonyms were obtained from a thesaurus (ICT, adoption, acceptance, model, technology*, student, higher education, and college). The subsequent structuring of the search equation with logical operators that united adoption, technology and higher education sought to provide more accurate search results of the titles, keywords, and summaries within the database. The following search strategies were devised:

Scopus: (TITLE (use OR adoption OR acceptance) AND TITLE (ict OR technolog*) AND TITLE (student OR scholar OR undergraduate OR learner OR college OR institution OR education OR “higher education”) OR KEY (use OR using OR usage OR handling OR utilization) AND KEY (adoption OR acceptance) AND KEY (ict OR technolog*) AND KEY (student OR scholar OR undergraduate OR learner OR college OR institution OR education OR “higher education”))

Web of Science: TI= ((use OR adoption OR acceptance) AND (ict OR technolog*) AND (student OR scholar OR undergraduate OR learner OR college OR institution OR education OR “higher education”)) OR AK= ((use OR using OR usage OR handling OR utilization) AND (adoption OR acceptance) AND (ict OR technolog*) AND (student OR scholar OR undergraduate OR learner OR college OR institution OR education OR “higher education”))

The search equations used retrieved 235 documents in Scopus and 1,659 documents in Web of Science. Before selecting articles, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The establishment of inclusion and exclusion criteria for systematic reviews responds to standards required for the design of high-quality research protocols, where the inclusion criteria refer to the key characteristics of the population under study and that will respond to the research objective, and where the exclusion criteria are characteristics of the population, even if it meets the inclusion criteria, that are determined to interfere with the success of the research due to biases or quality deficiencies (Patino & Ferreira, Citation2018).

2.4. Inclusion criteria

Studies that mention variables, constructs or factors used in the adoption of ICTs, only and exclusively in higher education

Studies where the target audience is students belonging to HEIs

Studies in published in English or Spanish

Studies published between 1991 and 2023

Studies that seek to generate an impact on learning

2.5. Exclusion criteria

Studies published prior to 2011

Studies developed in a language other than English or Spanish

Studies aimed at actors other than students

Studies that do not focus on higher education

2.6. Data management

According to Rethlefsen et al (Rethlefsen et al., Citation2019), literature reviews, to be systematic, must not only clearly detail the results of the application of the search strategy but also specify in a detailed and reproducible way the means or tools used to collect, process, and analyze the information obtained.

Using the established criteria and the filtering options available in the databases, 86 studies with a language other than English or Spanish were excluded, leaving 1,808 documents. After this, using the same filters but this time to identify article published before the year 2011, 217 documents were eliminated, leaving a total of 1,591. Subsequently, the publications retrieved from the databases were downloaded, and 232 investigations that were duplicated or in both databases were eliminated, leaving 1,359 documents. At this stage, 29% of the publications retrieved in Scopus and Web of Science were excluded.

Search tools provided by Microsoft Excel were used to continue the exclusion process, during which titles and abstracts were reviewed; 1,213 studies that did not include words such as higher education, university and student were eliminated, leaving a total of 146 documents, i.e., 8% of those originally retrieved. Finally, the full texts of the 146 publications were read to determine whether they mentioned the variables, constructs or factors used in the adoption of ICTs and whether they sought to generate an impact on learning. After this reading, 119 documents were discarded. Thus, 27 articles that met the inclusion criteria were selected to carry out variable extraction.

2.7. Selection process

As per the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA 2020 statement and emphasized by Page etal. (Citation2021) (Page et al., Citation2021), it is crucial to consider the use of automatic classifiers in the systematic review’s study selection process. The disclosure regarding the use of an internal automatic classifier should be provided along with details on internal or external validation to assess the potential risks of either missing studies or misclassifying them. In the current investigation, we employed Microsoft Excel® automation tools as an internal instrument. It is important to mention that this classifier was collaboratively developed by all the researchers involved in the study. Furthermore, each researcher independently applied the tool during the selection phase, utilizing predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This methodology was implemented to reduce the possibility of omitting crucial studies or misclassifying them, guaranteeing the consistency and validity of identifying relevant literature for the systematic review focused on the adoption of information and communication technologies in university education.

2.8. Risk of bias assessment

In accordance with the PRISMA methodology employed in this systematic review, it is crucial to discuss the methods utilized in evaluating the risk of bias among the studies included. In view of this, it is vital to indicate the particular tools utilized, the number of evaluators for each study, and if they worked independently. In this study, all authors conducted bias risk assessments in a consistent and objective manner. Data collection was performed by all authors. To achieve this, each author independently utilized an identical, automated Microsoft Excel® tool for evaluating every included study. This collaborative and standardized approach ensures the quality and integrity of results garnered from the systematic review by aligning with PRISMA guidelines and implementing a thorough risk of bias assessment process in the selected studies.

3. Results

This SLR, using the exclusion criteria defined in the methodological design, consists of a detailed analysis of a total of 27 articles that examine the adoption factors of ICTs oriented to university student learning. Bibliometric mapping is carried out in the initial phase of reporting the results, with the purpose of cementing a general context of the scientific literature, allowing the identification of the research trends of the subject and the current state, as well as the future, of the derived themes.

Bibliometric aspects of the literature were associated with the adoption of ICTs aimed at university student learning.

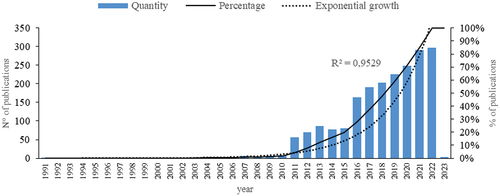

As seen in Figure , the scientific literature on the subject is located in the time window between the years 1991 and 2023, notably increasing from the year 2011; in that year, investigations were starting to use cutting-edge technological tools of the moment, specifically mobile learning. Likewise, the researchers aligned more with studies applied to the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology; in this context, there are important articles that study both the scope and the nature of the use of digital technologies by university students, determining that attitudes towards learning are influenced mainly by the teaching approaches of teachers (Margaryan et al., Citation2011), as well as research by Shroff et al (Shroff et al., Citation2011), who study the intention of using an electronic portfolio system by higher education students based on the technology acceptance model (TAM).

The Figure shows approximately exponential growth of interest in and publication of articles on the topic of the adoption of ICTs oriented to university students learning. The most productive years are 2022 and 2021, which indicates the importance of the subject both for the present and for the near future of scientific activity. For the year 2022, some studies focused on understanding the use of ICTs by medical students, as a characteristic population, in the pandemic period, showing the importance of factors such as attitude and subjective norms as predictors of the intention to use them (Rahmat et al., Citation2021), and in 2021, authors such as Alfadda and Mahdi (Alfadda & Mahdi, Citation2021) analyzed the acceptance and use of digital tools, such as Zoom®, by language students, demonstrating the diversity of the subject within the context of higher education.

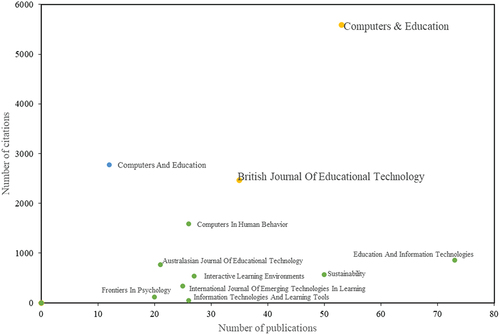

Three different groups of journals have been identified, as shown in Figure . Among the most notable in terms of productivity and impact are Computers & Education and British Journal Of Educational Technology, another category of journals is positioned as a reference in terms of impact, despite exhibiting a lower scientific productivity index, examples of which are journals such as Computers And Education, in contrast, The third group of scientific journals stands out for its scientific productivity, not so much for the number of citations, mainly highlighting Education And Information Technologies, this analysis reveals the diversity of approaches and emphases among the main journals that address the topic, encompassing both the proliferation of scientific production and the accumulated impact on the academic community.

Figure 4. Main journals.

The academic journals Computers & Education and British Journal Of Educational Technology have played a crucial role in generating knowledge in the field of the use and adoption of information and communication technologies (ICT) in university learning. Computers & Education, through certain studies has addressed the issue of the existence of digital natives (Margaryan et al., Citation2011), I have also explored the use of wiki technology to support student participation, contributing significantly to the understanding of technological practices in the educational environment (Cole, Citation2009) (Cole, Citation2009). On the other hand, the British Journal Of Educational Technology has provided valuable insights, such as the work on university students’ intentions to use mobile learning (Park et al., Citation2012), as well as the study that examined the use of instant messaging mobile to enhance student participation (Rambe & Bere, Citation2013).

Similarly, Computers And Education has had a significant impact on the understanding of technology adoption in education, with notable contributions such as the structural meta-analysis that applied the Technology Acceptance Model to explain teachers’ adoption of digital technologies (Scherer et al., Citation2019). Similarly, Education And Information Technologies has enriched the field, as evidenced by the study on mining student behavior in online learning environments through cognitive processes and information technologies (Jalal & Mahmood, Citation2019). By providing rigorous research and innovative perspectives, these journals have significantly contributed to the advancement of knowledge on the effective use of ICT in the university context.

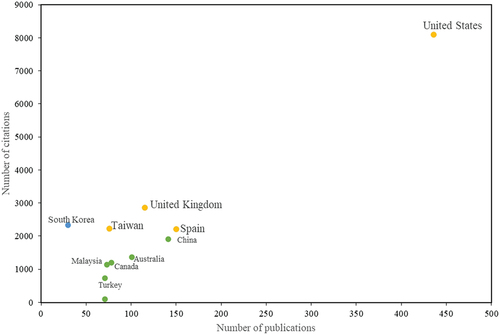

As regards the most important countries, three distinct groups of countries were identified, as shown in Figure . The most prominent countries in terms of productivity and impact on ICT research in higher education are the United States, the United Kingdom, Taiwan and Spain, which stand out both in terms of significant research production and impact on the international academic community. In another group are countries such as South Korea, which, despite having a lower index of scientific productivity, position themselves as references in terms of impact on the scientific literature; on the contrary, the third group of countries, led by China, stand out mainly for their scientific productivity, without this necessarily translating into a high number of citations.This analysis highlights the diversity of approaches and emphases among the leading countries in ICT research and higher education, demonstrating both the quality of scientific production and its global impact.

Figure 5. Main countries.

The United States, the United Kingdom, Taiwan, and Spain have emerged as prominent contributors in terms of scientific production and its impact on the field. The United States, for example, played a critical role during the COVID-19 pandemic by using technology to maintain the training of medical residents, as described in (Chick et al., Citation2020). In the case of the United Kingdom, factors influencing the adoption of mobile technology in higher education have been studied, providing valuable insights into the adoption of ICT by students (Abu-Al-Aish & Love, Citation2013). For its part, Taiwan has been addressed in research that examines the educational use of social networking technology in higher education (Hung & Yuen, Citation2010), while in Spain the acceptance of Moodle technology among business administration students has been analyzed (Escobar-Rodriguez & Monge-Lozano, Citation2012).

Furthermore, countries such as South Korea stand out as references in terms of impact, as reflected in the Technology Acceptance Model to understand the intention of university students to use e-learning (Park, Citation2009). On the other hand, China, although it stands out for its scientific productivity and not for its academic impact, has been the subject of analysis in terms of technology acceptance, as evidenced by the research on students’ intention to use an e-portfolio system (Shroff et al., Citation2011), these countries, by addressing different dimensions of ICT adoption in higher education, have significantly enriched scientific knowledge in this area, contributing to a more complete and global understanding of the challenges and opportunities associated with the integration of technology in university teaching.

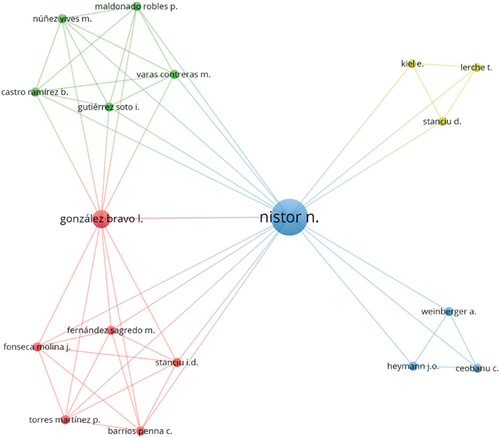

From another perspective, the bibliometric phase allowed investigating the main network of coauthor ship presented in the scientific body, which serves as an essential element to understand international scientific cooperation and association (Durieux & Gevenois, Citation2010; López-Sánchez et al., Citation2022). As seen in Figure , this coauthor ship network is presented in terms of associativity clusters, characterized by different colors; the blue cluster is the most relevant in terms of centrality and associativity because this cluster is related to all the rest. This cluster includes the authors Weinberger A., Heymann J.O., Ceobanu C., and Nistor N., who have produced articles that have addressed the ethnic and professional influences of the acceptance of technology by some higher education students using models validated by the scientific literature, for example, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Nistor et al., Citation2011).

Figure 6. Coauthorship network.

However, the cluster that accounts for the greatest number of authors is the associativity cluster indicated in red, composed of the authors Fernández Sagredo M., Fonseca Molina J., Stanciu I.D., Torres Martínez P., Barrios Penna C., and González Bravo I., who, together, have also made use of the UTAUT model to understand the adoption of technologies by dental students, revealing that expected performance is the main predictor (Bravo et al., Citation2020).

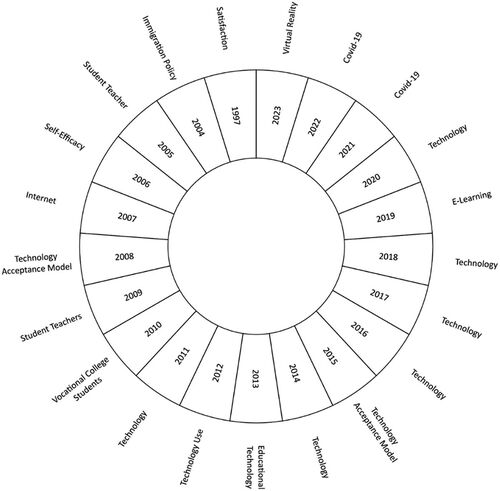

From a thematic approach, Figure allows an analysis of the thematic evolution of the adoption of ICTs oriented to university student learning between 1997 and 2023, during which there are consolidated concepts within the scientific body. When the topic was first explored, the studies focused on understanding the role of satisfaction within adoption, as observed in Igbaria and Tan (Igbaria & Tan, Citation1997), where both the implications and the consequences of the adoption of information technologies, with regard to user satisfaction, use of the system and individual impact in Singapore, determined that satisfaction is a predictor of the use of technologies.

The use of the TAM for studies on the adoption of this technology has occurred since 2008, with studies such as those by Martínez-Torres et al (Martínez-Torres et al., Citation2008), in which the adoption of digital tools in laboratories was validated by the extended TAM, as well as by Rezaei et al (Rezaei et al., Citation2008), in which the applicability of this model to predict the adoption of electronic learning in agricultural higher education was evidenced.

The literature in recent years has been framed by topics that are mostly validated within the scientific field, such as E-learning, as the leading concept in 2019, in studies such as that by Salloum et al (Salloum et al., Citation2019), who developed a comprehensive technology acceptance model based on the extended TAM with the most used external variables, for example, computer self-efficacy, subjective norm, perceived enjoyment, system quality, information quality, accessibility and computer playfulness.

Consistently, researchers in 2021 and 2022 focused on the analysis of adoption factors within the context of the pandemic, with the term COVID-19 being the most used in research articles; understanding the acceptance and use of technology was essential to continuing education in the pandemic period (Chick et al., Citation2020).

Likewise, the pandemic period allowed the emergence and consolidation of other technologies, such as virtual reality, which in recent years has been highly applied in the educational context, mainly for higher education, for example, the study by Bauce et al (Bauce et al., Citation2023), in which the adoption of virtual reality technology for nursing education was studied.

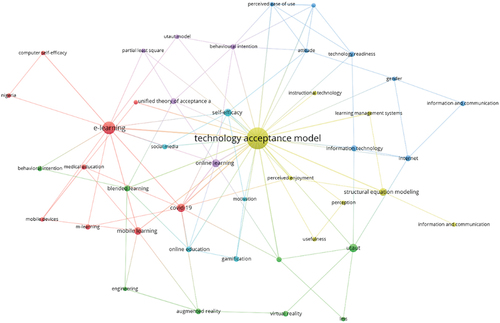

Continuing with the analysis of the themes associated with the scientific production on the adoption of ICTs oriented to university student learning, Figure presents the network of the co-occurrence of keywords, allowing the identification of thematic associativity from the joint relationship of two or more keywords (Durieux & Gevenois, Citation2010). In this sense, the main thematic cluster is yellow, composed mainly of the Technology Acceptance Model as well as other concepts such as Instructional Technology, Perceived Enjoyment, Perception, Usefulness, Structural Equation Modelling and Information and Communication. These articles have contributed to existing knowledge from the analysis of the adoption of online social networks as an educational tool for university students based on the TAM, validated by means of structural equations, as evidenced in Al-Sharafi et al (Al-Sharafi et al., Citation2018).

Figure 8. Keyword co-occurrence network.

Another illuminating cluster within the keyword co-occurrence network is the red cluster, composed of concepts such as mobile devices, m-learning or mobile learning, COVID-19, medical education, Nigeria, computer self-efficacy and, mainly, e-learning, which occur in studies in which electronic and mobile learning technologies are adopted as tools to support higher education in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic in the context of emerging countries such as Nigeria (Okuonghae et al., Citation2021).

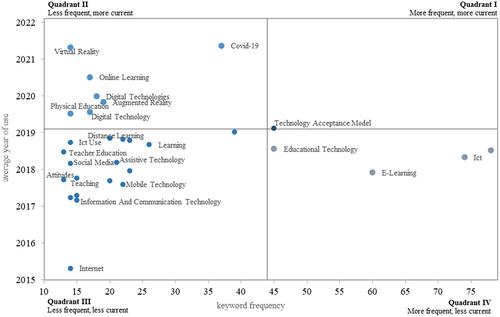

Finally, the bibliometric phase within this literature review analyses the trends in keywords by means of a Cartesian plane, where the X-axis measures the frequency of each keyword, and the Y-axis considers the average year of use as a measure of the validity of each concept. As seen in Figure , there are 4 different quadrants. Quadrant IV contains the most frequent but less current concepts, i.e., decreasing concepts in the field, for example, E-learning, which has been fundamental in validating the adoption of other tools such as m-learning (Hamidi & Chavoshi, Citation2018), educational technology, which has been analyzed based on its impact on the perceived quality of education (Petko et al., Citation2016), and ICT.

Figure 9. Validity and frequency of keywords.

Quadrant III contains infrequent and current concepts based on their average year; therefore, these keywords, at present, have not been sufficiently consolidated within the scientific body, including concepts such as Internet, Mobile Technology, Social Media, Teacher Education, Attitudes and Distance Learning, among others.

Quadrant II includes terms that although they are not the most frequent in the literature are among the most current or have the most recent average year of use, i.e., emerging concepts in the field of scientific knowledge on the subject. Digital technology, constituted as one of the main tools of ICTs, has been validated in different fields of educational knowledge, as evidenced in (Papouli et al., Citation2020), who analyse the adoption of digital technologies for social work students; augmented reality has been analysed for its influence on the mood of students in terms of creativity (Faqih & Jaradat, Citation2021); COVID-19 demanded the mandatory adoption of ICTs for continuity in higher education, as detailed in Sukendro et al (Sukendro et al., Citation2020), who analyse ICT adoption by sports science students; and virtual reality has been shown to allow immersive learning in virtual environments, i.e., 3D photos or 360° videos (Marks & Thomas, Citation2022).

Quadrant I contains all the concepts positioned among the most frequent and current within the scientific literature on the adoption of ICTs oriented to university student learning. Only Technology Acceptance Model is considered a growing keyword; this concept has been frequently investigated by authors such as Hsu and Lin (Hsu & Lin, Citation2021), who have validated it in the context of language learning, and Al-Rahmi et al (Al-Rahmi et al., Citation2022), who have studied the adoption of m-learning and other mobile technologies.

3.1. List of variables related to TAM

This SLR allowed the identification of all the articles that have variables related to models or strategies that seek technological adoption by students in higher education centres. Of the 27 articles, 9 had variables associated with the TAM, 8 studies are related to strategies that sought to strengthen the adoption of technology in favour of learning, 7 articles contained variables that are associated with UTAUT, 2 studies had variables related to personal learning environment systems, and 1 had variables pertaining to the theory of self-determination.

Regarding the category with the most studied variables, 9 articles focus on the perceived usefulness of technology, 8 articles address the ease of using ICTs, and 7 studies investigate the variables attitude towards use, expected effort, expected outcome and social influence; other articles study variables different from but no less important than those mentioned above, only less frequent.

For the studies in Table related to the TAM, some reinforce the knowledge or learning regarding the impact that the use of ICTs has on students in relation to usefulness and ease of use (Kılıç, Citation2014; Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2019), and other articles indicate that perceived self-efficacy, motivation (Shah et al., Citation2021; Taylor, Citation2018), expectations for personal outcomes and perceived support to improve social ties are pertinent antecedents for students’ initial acceptance of using ICTs for learning (Ifinedo, Citation2017), taking into account that technological readiness could affect students’ attitude towards the use of ICTs (Gombachika & Khangamwa, Citation2013; Kanthawongs & Chitcharoena, Citation2013).

Table 1. Variables related to the TAM

Nine investigations based on the TAM studied 20 variables, among which the most used was perceived usefulness (n = 9), accounting for 15%, followed by ease (n = 8), accounting for 13%, and attitude of use (n = 7), accounting for 11%. These variables are specifically based on explaining and predicting the acceptance of technology by users (Fernández Morales et al., Citation2015; Setyohadi et al., Citation2017; Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2019).

3.2. List of variables related to strategies

A strategy can be defined as the establishment of actions that make it possible to meet a specific objective (Sierra, Citation2013). For this specific case, explicit and detailed actions (Humanante-Ramos et al., Citation2019; Paz-Pérez et al., Citation2018) are developed in the investigations, deliberately based on adopting ICTs among higher education students, from the variables extracted in the documents.

The studies in Table that investigate variables associated with strategies allowed establishing a positive assessment of ICTs with collaborative or personalized learning experiences (Sánchez et al., Citation2013; Vota et al., Citation2014) because they facilitate the search for resources, compliance with academic tasks (Muñoz-Repiso & Tejedor, Citation2017) and improvements in student performance (Basri et al., Citation2018; Rojas et al., Citation2018). These studies also relate the importance of generating processes to strengthen digital skills and abilities for students who use ICTs (Briceño et al., Citation2017; Humanante-Ramos et al., Citation2019) and, finally, demonstrate how technology in learning can generate a competitive advantage when entering the workplace (Paz-Pérez et al., Citation2018).

Table 2. Variables related to strategies

Eight investigations studied 10 variables pertaining to strategies, among which perceived usefulness, teacher readiness, satisfaction with use and performance were the 4 variables most encountered by the authors, with 2 occasions each and each variable accounting for 14%. In turn, the variables pertaining to these strategies were proposed as routes that allowed aligning the adoption of ICTs in learning processes for HEI students.

3.3. List of variables related to the UTAUT

The articles in Table related to the UTAUT focused their findings on the ability of this theory to explain the adoption of ICTs; showing that expected performance, expected effort and social influence have positive significant relationships with behavioral intention (Haron et al., Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2019) to use ICT tools and that facilitating conditions are directly related to use behavior (Martín-García et al., Citation2014; Rosaline & Wesley, Citation2017).

Table 3. Variables related to the UTAUT

Knowing about the technological appropriation of students is important (Wan et al., Citation2017) be-cause, among other aspects, it helps to improve the conditions of educational systems through opening effective communication channels that overcome the space and time limitations and contribute to the administration and equitable distribution of knowledge (Fernández Morales et al., Citation2015), which, consequently, should improve the academic performance of students and, consequently, their abilities to face the world of work and their daily lives (Almisad & Alsalim, Citation2020; Yakubu & Dasuki, Citation2018).

Seven investigations based on the UTAUT studied 11 variables, among which expected effort, expected outcome and social influence were the 3 variables most used by the authors, with 7 occasions each and with each variable accounting for 18%. The UTAUT accounted for 3 of the 4 main variables, reinforcing its effort to synthesize and use the best models, such as the TAM (Haron et al., Citation2021; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003).

3.4. List of variables related to others

The variables related to others pertain to personal learning environment systems, which are conceived as a transformation in the training methodology that promotes self-learning, from the use of online resources, forming a system centred on the student (Martínez et al., Citation2016; Villaverde & Benito, Citation2015). In turn, the list includes the self-determination theory, which proposes that social contextual factors prevent or favour the motivation of an individual by satisfying their basic psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017; Shah et al., Citation2021).

The studies in Table that include variables associated with personal learning environments allowed establishing which technologies university students value for learning and how they perceive the effectiveness of technology to support their learning (Dabbagh et al., Citation2019), i.e., their attitude towards the use of ICTs for learning (Villaverde & Benito, Citation2015). Table shows the studies based on the self-determination theory that examined the impact of digital learning on student motivation to confirm a direct relationship between digital learning and student satisfaction (Shah et al., Citation2021).

Table 4. Variables related to others

Two studies based on personal learning environment systems investigated 4 variables, and 1 study based on the theory of self-determination investigated 4 variables. Each variable accounts for 13% of the total in Table . Although variables pertaining to other models are presented, there are yet others that give value to the subject studied due to their relevance.

4. Discussion

Research on the use and adoption of ICTs aimed at student learning is of great interest due to the impact it has on the knowledge society, a society that, influenced by technological innovation and information technologies, allows multiple activities to compete and be successful in a modern world. From this, it is important to recognize that to improve training and academic environments, tools are key to generating learning experiences, integrating areas of knowledge, and developing skills for life.

Therefore, it is evident in the research that the subject has a strong relationship with technology acceptance models, where the main factors are oriented to learning by university students. In this context, TAMs have a great variety of variables that participate in the processes of technology adoption in HEIs. This result is consistent with those obtained by Kanthawongs et al (Kanthawongs & Chitcharoena, Citation2013), Naffah et al (Naffah et al., Citation2016). and Valencia-Arias et al (Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2019), authors who state in their studies that the TAM is an opportune model to understand the acceptance of technology in training and academic environments.

However, the scope of the study is uncertain due to the context of the pandemic because it is not clear when it will end. However, it serves as a support to strengthen training processes during the health contingency and as a step for new studies when the pandemic ends. This is an investigation that provides theoretical contributions that influence the adoption of ICTs oriented to university student learning and allows identifying the most relevant variables, such as attitude towards use, perceived ease, intention to use and perceived usefulness. Some variables have recently been used by researchers, such as perceived fear, satisfaction or enjoyment and technological complexity.

The results reported by Al-Maroof et al (Al-Maroof et al., Citation2020). established that perceived fear, which has an important effect on measuring the influence of COVID-19 on a group of students, was directly related to perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness and with another external variable of the TAM, subjective norms. Likewise, Hu et al (Hu et al., Citation2022). revealed in their research that the TAM is relevant in explaining the intention to use technology among university students with fear of technological complexity generated by the pandemic, revealing effects associated with perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use.

There are several practical implications of this research. Initially, the results from this study will allow the formulation of models focused on the needs that are currently presented in the academic sector and even be replicable in different social, cultural, and educational environments, without interrupting training processes. However, modelling exercises may be conditioned on the use of variables based on the contexts that are presented.

One potential area for future research is the impact of ICT on student engagement and motivation (Shah et al., Citation2021). While some studies have suggested that ICT can enhance student engagement and motivation (Kowitlawakul et al., Citation2022), others have found that excessive use of technology can lead to distraction and reduced attention span (Mendoza et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2022). Additionally, there may be individual differences in how students respond to different types of technology, which could impact their engagement and motivation. Further research in this area could help to identify best practices for using ICT to enhance student engagement and motivation, while minimizing potential negative effects. Finally, the results of this review serve as a reference guide for research that has a methodological approach directed at systematic reviews of literature on the use and adoption of technology by higher education students.

4.1. Limitations

Acknowledging the extent and significance of this research, it is crucial to address limitations that could impact the interpretation and generalizability of the findings. Firstly, the absence of a dedicated quality assessment in the selected studies presents a potential threat to the study’s overall validity. Despite utilizing the PRISMA methodology for systematic review, the lack of a thorough assessment of the quality of the included articles introduces variability that requires consideration. Authors should acknowledge the limitations resulting from this omission and recognize that the varying quality of the reviewed studies may affect the strength of the drawn conclusions.

Moreover, a noteworthy limitation pertains to the restricted scope of databases utilized for this review. The emphasis on Scopus and Web of Science, although useful in covering a significant amount of literature, generates a possible bias by excluding relevant research existing in other databases. This limitation may compromise the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the review, as relevant studies could have been unintentionally omitted. Recognizing this constraint is crucial, and authors should recommend that future research efforts expand the search to include a broader range of databases. This approach would enhance the understanding of the academic landscape concerning the integration of information and communication technologies in university education.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, TAM variables are prevalent in studies of ICT adoption in HEIs for improving students’ learning. Other influential actors, such as teachers, should be explored, and complete coverage of the factors that intervene in the adoption of ICTs for the normal development of training processes should be sought.

Undoubtedly, the pandemic promoted the development and strengthening of adaptive abilities by students to meet learning objectives. However, as the pandemic end nears, research contexts prior to, during and after COVID-19 will be necessary to learn and survey its implications in the practicality of the training processes within HEIs, with the main focus on students.

In conclusion, learning-oriented ICT adoption models and strategies offer great opportunities and have even been adapted to the contexts of many countries and institutions due to the various conditions to which they may be exposed and their adaptability properties. Likewise, the pandemic facilitated the development and strengthening of digital skills mediated by various technological tools, skills that can be the subject of study for models or strategies for the adoption of ICTs by students in HEIs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abelha, M., Fernandes, S., Mesquita, D., Seabra, F., & Ferreira-Oliveira, A. T. (2020). Graduate employability and competence development in higher education—a systematic literature review using PRISMA. Sustainability, 12(15), 5900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155900

- Abu-Al-Aish, A., & Love, S. (2013). Factors influencing students’ acceptance of m-learning: An investigation in higher education. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 14(5), 82–22. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v14i5.1631

- Aleixandre-Benavent, R., Muñoz, M. G., Alonso-Arroyo, A., & Dios, J. G.-L. (2011). Fuentes de información bibliográfica (I). Fundamentos para la realización de búsquedas bibliográficas. Acta Pediátr Esp, 69, 131–136.

- Alfadda, H. A., & Mahdi, H. S. (2021). Measuring students’ use of zoom application in language course based on the technology acceptance model (TAM). Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 50(4), 883–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09752-1

- Al-Maroof, R. S., Salloum, S. A., Hassanien, A. E., & Shaalan, K. (2020). Fear from COVID-19 and technology adoption: The impact of Google meet during coronavirus pandemic. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(3), 1293–1308. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1830121

- Almisad, B., & Alsalim, M. (2020). Kuwaiti female university students’ acceptance of the integration of smartphones in their learning: An investigation guided by a modified version of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 12(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTEL.2020.103812

- Al-Rahmi, A. M., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Alturki, U., Aldraiweesh, A., Almutairy, S., & Al-Adwan, A. S. (2022). Acceptance of mobile technologies and M-learning by university students: An empirical investigation in higher education. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 7805–7826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10934-8

- Al-Sharafi, M., Mufadhal, M., Arshah, R. A., & Sahabudin, N. A. (2018). The acceptance of online social networks as a technology-based education tools among higher institutes students: A structural equation modeling approach. Scientia Iranica, 26, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.24200/sci.2018.51570.2256

- Ancira, A. Z., & Gutiérrez, F. J. M. (2011). Integración y apropiación de las TIC en los profesores y los alumnos de edu-cación media superior. Apertura, 3, 1–26.

- Basri, W. S., Alandejani, J. A., & Almadani, F. M. (2018). ICT adoption impact on students’ academic performance: Evidence from Saudi universities. Education Research International, 2018, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1240197

- Bauce, K., Kaylor, M. B., Staysniak, G., & Etcher, L. (2023). Use of theory to guide integration of virtual reality technology in nursing education: A scoping study. Journal of Professional Nursing: Official Journal of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 44, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2022.10.003

- Bravo, L. G., Fernández Sagredo, M., Torres Martínez, P., Barrios Penna, C., Fonseca Molina, J., Stanciu, I. D., & Nistor, N. (2020). Psychometric analysis of a measure of acceptance of new technologies (UTAUT), applied to the use of haptic virtual simulators in dental students. European Journal of Dental Education: Official Journal of the Association for Dental Education in Europe, 24(4), 706–714. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12559

- Briceño, M. L., Saldivia, B. E. S., Jiménez, A. S. A., Martínez, M. M., & Díaz, J. H. (2017). Factores que influyen en la adopción de las Tecnologías de Información y Co-municación por parte de las universidades. Dimens Enseñ-Aprendiz, 21, 143–153.

- Castro, M. P., Castillo, M. R., & Zermeño, M. G. G. (2019). Estrategias de visibilidad para la producción científica en revistas electrónicas de acceso abierto: Revisión sistemática de literatura. Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 20, 13. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks2019_20_a24

- Chick, R. C., Clifton, G. T., Peace, K. M., Propper, B. W., Hale, D. F., Alseidi, A. A., & Vreeland, T. J. (2020). Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Surgical Education, 77(4), 729–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

- Cole, M. (2009). Using wiki technology to support student engagement: Lessons from the trenches. Computers & Education, 52(1), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.07.003

- Dabbagh, N., Fake, H., & Zhang, Z. (2019). Student perspectives of technology use for learning in higher education. RIED Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 22(1), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.22.1.22102

- Durieux, V., & Gevenois, P. A. (2010). Bibliometric indicators: Quality measurements of scientific publication. Radiology, 255(2), 342–351. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.09090626

- Escobar-Rodriguez, T., & Monge-Lozano, P. (2012). The acceptance of Moodle technology by business administration students. Computers & Education, 58(4), 1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.11.012

- Faqih, K. M. S., & Jaradat, M.-I. R. M. (2021). Integrating TTF and UTAUT2 theories to investigate the adoption of augmented reality technology in education: Perspective from a developing country. Technology in Society, 67, 101787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101787

- Fernández-Gutiérrez, M., Gimenez, G., & Calero, J. (2020). Is the use of ICT in education leading to higher student outcomes? analysis from the Spanish autonomous communities. Computers & Education, 157, 103969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103969

- Fernández Morales, K., McAnally Salas, L., & Vallejo Casarín, A. (2015, June). Apropiación tecnológica:Una visión desde los modelos y las teorías que la explican. Perspectiva Educacional, 54(2). https://doi.org/10.4151/07189729-Vol.54-Iss.2-Art.331

- Gombachika, H. S. H., & Khangamwa, G. (2013). ICT readiness and acceptance among TEVT students in university of Malawi. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 30(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650741311288805

- Hamidi, H., & Chavoshi, A. (2018). Analysis of the essential factors for the adoption of mobile learning in higher education: A case study of students of the university of technology. Telematics and Informatics, 35(4), 1053–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.09.016

- Haron, H., Hussin, S., Yusof, A. R. M., Samad, H., & Yusof, H. (2021). Implementation of the UTAUT model to understand the technology adoption of MOOC at public universities. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science & Engineering, 1062(1), 12025. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1062/1/012025

- Hsu, H. T., & Lin, C. C. (2021). Extending the technology acceptance model of college learners’ mobile‐assisted language learning by incorporating psychological constructs. British Journal of Educational Technology: Journal of the Council for Educational Technology, 53(2), 286–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13165

- Humanante-Ramos, P., Solís-Mazón, M. E., Fernández-Acevedo, J., & Silva-Castillo, J. (2019). Las competencias TIC de los estudiantes que ingresan en la universidad: Una experiencia en la Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud de una universidad latinoamericana. Educación Médica, 20(3), 134–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2018.02.002

- Hung, H. T., & Yuen, S. C. Y. (2010). Educational use of social networking technology in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(6), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.507307

- Hu, X., Zhang, J., He, S., Zhu, R., Shen, S., & Liu, B. (2022). E-learning intention of students with anxiety: Evidence from the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 309, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.121

- Ifinedo, P. (2017). Examining students’ intention to continue using blogs for learning: Perspectives from technology acceptance, motivational, and social-cognitive frameworks. Computers in Human Behaviour, 72, 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.049

- Igbaria, M., & Tan, M. (1997). The consequences of information technology acceptance on subsequent individual performance. Information & Management, 32(3), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-7206(97)00006-2

- Jalal, A., & Mahmood, M. (2019). Students’ behavior mining in e-learning environment using cognitive processes with information technologies. Education and Information Technologies, 24(5), 2797–2821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09892-5

- Kanthawongs, P., & Chitcharoena, C. (2013). Applying the technology acceptance model in a study of the factors affecting intention to use Facebook in education of the Thai university students. Proceedings of Proceedings of the 7th International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics and In-formatics, Florida, United States.

- Kılıç, E. (2014). Determining the factors of affecting the moodle use by using TAM. The story of a university after a destructive earthquake. Hacettepe universitesi Eugitim Fakultesi Dergisi, 29, 169–179.

- Kowitlawakul, Y. (2022). Utilizing educational technology in enhancing undergraduate nursing students’ engagement and motivation: A scoping review. Journal of Professional Nursing, 42, 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2022.07.015

- Liu, D., et al. (2019). Using the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) to investigate the intention to use physical activity apps: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 7(9), e13127. https://doi.org/10.2196/13127

- López, I. E. G. (2019). Experiencias del modelo de la Red de Comunidades para la Renovación de la Enseñanza-Aprendizaje y el uso de TIC móviles en la UAEMéx. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 10(19), 40. https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v10i19.561

- López-Sánchez, J., Landazábal, N. S., & Valencia-Arias, A. (2022). Tendencias en estudios sobre el uso y adopción de tecnologías de información y comunicación en instituciones de educación superior: Un análisis bibliométrico. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica Del Norte, (67), 136–162. https://doi.org/10.35575/rvucn.n67a6

- Manterola, C., Astudillo, P., Arias, E., & Claros, N. (2013). Revisiones sistemáticas de la literatura. Qué se debe saber acerca de ellas. Cirugia espanola, 91(3), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2011.07.009

- Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A., & Vojt, G. (2011). Are digital natives a myth or reality? University students’ use of digital technologies. Computers & Education, 56(2), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.09.004

- Marks, B., & Thomas, J. (2022). Adoption of virtual reality technology in higher education: An evaluation of five teaching semesters in a purpose-designed laboratory. Education and Information Technologies, 27(1), 1287–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10653-6

- Martínez-Torres, M. R., Marín, S. L. T., García, F. B., Vázquez, S. G., Oliva, M. A., & Torres, T. (2008). A technological acceptance of e-learning tools used in practical and laboratory teaching, according to the European higher education area. Behaviour & Information Technology, 27(6), 495–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290600958965

- Martínez, J. A. G., Vargas, M. A. F., & Jiménez, A. G. (2016). Desarrollo del entorno personal de aprendizaje: Valoración de una experiencia con estudiantes universitarios. Summa Psicológica, 13(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.18774/448x.2016.13.317

- Martín-García, A. V., Dujo, Á. G., & Rodríguez, J. M. M. (2014). Factores determinantes de adopción de blended learning en educación superior. Adaptación del modelo UTAUT. Educación XX1, 17(2), 217–240. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.17.2.11489

- Mendoza, J., Pody, B., Lee, S., Kim, M., & McDonough, I. (2018). The effect of cellphones on attention and learning: The influences of time, distraction, and nomophobia. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.027

- Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of web of science and scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

- Muñoz-Repiso, A. G. V., & Tejedor, F. J. T. (2017). Percepción de los estudiantes sobre el valor de las TIC en sus estrategias de aprendizaje y su relación con el rendimiento. Educación XX1, 20(2), 137–159. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.19035

- Naffah, S. C., Valencia Arias, A., Hernández, J. B., & Rojas, C. M. O. (2016). Percepciones estudiantiles acerca del uso de nuevas tecnologías en instituciones de Educación Superior en Medellín. Revista Lasallista de Investigación, 13(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.22507/rli.v13n2a14

- Nistor, N., Weinberger, A., Ceobanu, C., & Heymann, J. O. (2011). Educational technology and culture: The influence of ethnic and professional culture on learners’ technology acceptance. In C. D. Kloos, D. Gillet, R. M. C. García, F. Wild, & M. Wolpers (Eds.), Towards ubiquitous learning (pp. 477–482). Springer.

- Okuonghae, O., Igbinovia, M. O., & Adebayo, J. O. (2021). Technological readiness and computer self-efficacy as predictors of E-learning adoption by LIS students in Nigeria. Libri, 72(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2020-0166

- Page, M. J. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

- Papouli, E., Chatzifotiou, S., & Tsairidis, C. (2020). The use of digital technology at home during the COVID-19 outbreak: Views of social work students in Greece. Social Work in Education, 39(8), 1107–1115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1807496

- Park, S. Y. (2009). An analysis of the technology acceptance model in understanding university students’ behavioral intention to use e-learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 12(3), 150–162. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.12.3.150

- Park, S. Y., Nam, M. W., & Cha, S. B. (2012). University students’ behavioral intention to use mobile learning: Evaluating the technology acceptance model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(4), 592–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01229.x

- Patino, C. M., & Ferreira, J. C. (2018). Inclusion and exclusion criteria in research studies: Definitions and why they matter. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia : publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia, 44(2), 84. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562018000000088

- Paz-Pérez, L. A., Tamez-González, G., Hernández-Paz, A., & Leyva-Cordero, O. (2018). Presencia, utilización y aprovechamiento de las TIC en la formación académica estudiantil. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 9, 191–210. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2018.26.303

- Petko, D., Cantieni, A., & Prasse, D. (2016). Perceived quality of educational technology matters: A secondary analysis of students’ ICT use, ICT-related attitudes, and PISA 2012 test scores. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 54(8), 1070–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633116649373

- Rahmat, T. E., Raza, S., Zahid, H., Abbas, J., Sobri, F. A. M., & Sidiki, S. N. (2021). Nexus between integrating technology readiness 2.0 index and students’ e-library services adoption amid the COVID-19 challenges: Implications based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 11, 50. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_508_21

- Rama, C. (2021). La nueva educación híbrida. CUAD University, 11, 1–133. http://dspaceudual.org/handle/Rep-UDUAL/202

- Rambe, P., & Bere, A. (2013). Using mobile instant messaging to leverage learner participation and transform pedagogy at a South African university of technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4), 544–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12057

- Rethlefsen, M. L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., Koffel, J. B., Blunt, H., Brigham, T., Chang, S., Clark, J., Conway, A., Couban, R., de Kock, S., Farrah, K., Fehrmann, P., Foster, M., Fowler, S. A. … Wright, K. (2019). PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic Review, 10(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z

- Rezaei, M., Mohammadi, H. M., Asadi, A., & Kalantary, K. (2008). Predicting e-learning application in agricultural higher education using technology acceptance model. Turkish Online Journal Distance Education, 9(1), 85–95.

- Rojas, D. G., Jiménez-Fernández, S., & Rodríguez, R. M. S. (2018). Gestión del tiempo y uso de las TIC en estudiantes universitarios. Pixel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, (53), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i53.07

- Rosaline, S., & Wesley, J. R. (2017). Factors affecting students’ adoption of ICT tools in higher education institutions. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education: An Official Publication of the Information Resources Management Association, 13, 82–94. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijicte.2017040107 2

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

- Salloum, S. A., Alhamad, A. Q. M., Al-Emran, M., Monem, A. A., & Shaalan, K. (2019). Exploring students’ acceptance of E-learning through the development of a comprehensive technology acceptance model. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Access, 7, 128445–128462. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2019.2939467

- Salvador-Oliván, J. A., Marco-Cuenca, G., & Arquero-Avilés, R. (2018). Las revisiones sistemáticas en Biblioteconomía y Documentación: Análisis y evaluación del proceso de búsqueda. Revista espanola la de documentacion cientifica, 41(2), 207. https://doi.org/10.3989/redc.2018.2.1491

- Sánchez, O. N. (2016). Tecnologías de la información y la comunicación aplicadas a la educación. Praxis & Saber, 7(14), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.19053/22160159.5215

- Sánchez, J. J. M., Ruiz, A. B. M., Sánchez, F. A. G., & Pina, F. H. (2013). Valoración de las TIC por los estudiantes universitarios y su relación con los enfoques de aprendizaje. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 31(2), 537–554. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.31.2.151891

- Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Tondeur, J. (2019). The technology acceptance model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Computers & Education, 128, 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.009

- Setyohadi, D. B., Aristian, M., Sinaga, B. L., & Hamid, N. A. A. (2017). Social critical factors affecting intentions and behaviours to use E-learning: An empirical investigation using technology acceptance model. Asian Journal of Scientific Research, 10(4), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajsr.2017.271.280

- Shah, S. S., Shah, A. A., Memon, F., Kemal, A. A., & Soomro, A. (2021). Aprendizaje en línea durante la pandemia de COVID-19: aplicación de la teoría de la autodeterminación en la ‘nueva normalidad’. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 26(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2020.12.004

- Shroff, R. H., Deneen, C. C., & Ng, E. M. W. (2011). Analysis of the technology acceptance model in examining students’ behavioural intention to use an e-portfolio system. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(4), 600–618. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.940

- Sierra, E. R. C. (2013). El concepto de estrategia como fundamento de la planeación estratégica. Pensamiento Gest, 152–181.

- Simó, V. L., Couso, D., & Simarro, C. (2020). Educación STEM en y para el mundo digital. Cómo y por qué llevar las her-ramientas digitales a las aulas de ciencias, matemáticas y tecnologías. Revista De Educacion, 5. https://doi.org/10.6018/red.410011

- Sukendro, S. (2020). Using an extended technology acceptance model to understand students’ use of e-learning during covid-19: Indonesian sport science education context. Heliyon, 6(11), 5410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05410

- Taylor, A. (2018). The impact of employability on technology acceptance in students: Fin-dings from Coventry university London. Jounal of Pedagogy Dev, 8(3), 1–19.

- Urrútia, G., & Bonfill, X. (2013). La declaración PRISMA: Un paso adelante en la mejora de las publicaciones de la Revista Española de Salud Pública. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 87(2), 99–102. https://doi.org/10.4321/s1135-57272013000200001

- Valencia-Arias, A., Chalela-Naffah, S., & Bermúdez-Hernández, J. (2019). A proposed model of e-learning tools acceptance among university students in developing countries. Education and Information Technologies, 24(2), 1057–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9815-2

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

- Villaverde, V. A., & Benito, V. D. (2015). Aprendizaje percibido y actitud hacia las TIC desde la perspectiva de los PLE. Opción, 31(5), 91–110. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=31045570006

- Vota, A. M. G. A., Diez, M. C. G., & Beltrán, J. L. B. (2014). Escenarios de aprendizaje y satisfacción estudiantil en posgrado virtual 2010. Apertura, 9, 110–125. https://doi.org/10.32870/ap.v9n1.918

- Wan, K., Cheung, G., & Chan, K. (2017). Prediction of students’ use and acceptance of clickers by learning approaches: A cross-sectional observational study. Education in Science: The Bulletin of the Association for Science Education, 7(4), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7040091

- Wang, C., Salisbury-Glennon, J., Dai, Y., Lee, S., & Dong, J. (2022). Empowering college students to decrease digital distraction through the use of self-regulated learning strategies. Contemporary Educational Technology, 14(4), 3. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/12456

- Yakubu, M. N., & Dasuki, S. I. (2018). Factors affecting the adoption of e-learning technologies among higher education students in Nigeria. Information Development, 35(3), 492–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666918765907