Abstract

This study explores the connections between aspects of the school environment and emotional problems among boys and girls. The sample comprised 2,120 adolescents aged 17 and 18 years, in 129 school classes from 13 upper secondary schools in Trøndelag county, Norway. The response rate was 79%. The girls reported more emotional problems than the boys. Variations in perceptions of emotional problems between schools and classes is an under-researched topic. Multilevel models revealed a substantial class-level effect regarding emotional problems and a smaller school-level effect. Emotional problems varied between classes because of the class composition (share of boys and girls) and the class context. Contextual factors relevant to emotional problems were peer support, teacher support, and that emotional problems could ‘spread’ in a class. Relations between emotional problems and peer support, teacher support, and parental support were stronger for girls than boys. The study emphasizes the importance of the classroom environment, and it suggests that fostering strong relationships between adolescents and teachers, as well as addressing emotional issues among adolescents, can have a positive impact on emotional well-being. An important topic for future studies is whether the inclusion of the health and life skills theme improves mental health support in schools.

REVIEWING EDITORS:

Introduction

Most adolescents in Norway and other countries thrive and have good mental health, but some adolescents experience mental disorders (this refers to a psychiatric diagnosis) or mental problems (Morin, Citation2021; Rehm & Shield, Citation2019). Mental health problems are considered a significant economic burden at the national and global levels (Reneflot et al., Citation2018). People with mental problems are more likely to drop out of school and to be unemployed, despite their wish to work, and thus miss out on associated opportunities for financial security, personal development, social contact, and social status (Gustafsson et al., Citation2010; van Droogenbroeck et al., Citation2018).

Mental problems can be divided into externalizing and internalizing components. Whereas externalizing problems like conduct problems and hyperactivity particularly occur in interaction with the social environment, internalizing problems are focused on the self (Achenbach et al., Citation2016: Nikstat & Riemann, Citation2020). Examples of internalizing problems include social withdrawal, anxiety, depression, and emotional problems; this study focuses on emotional problems.

The aim is to investigate how different aspects of the school environment correlate with emotional problems among adolescents aged 17 and 18 years in Norway. There are many studies on the connections between the school environment and internalizing problems like emotional problems (Morin, Citation2021), but few studies have investigated whether adolescents′ mental problems vary among schools and classes. Because adolescents are nested within classes and classes are nested within schools, multilevel modeling makes it possible to separate the school and class effects from individual circumstances. It is reasonable to expect variations in emotional problems between schools and classes due to the composition of students and context of each educational setting. A compositional explanation indicates that schools and classes include adolescents with different risks of emotional problems, whereas the contextual explanation focuses on the shared organizational, cultural, social, and physical factors within the schools and classes (Andersson et al., Citation2009).

This study analyzes the possible effect of the school and the school class on boys’ and girls’ perceived emotional problems. Moreover, the study investigates whether relations between emotional problems and the social support from peers, teachers and parents are the same or differs for boys and girls. The gender perspective has been chosen for the study since girls report substantially more emotional problems than boys (Bor et al., Citation2014; Choi, Citation2018), though the gender gap in emotional problems is poorly understood (Campbell et al., Citation2021; Haugan et al., Citation2021). Understanding potential gender differences in how aspects of the school environment such as social support impacts emotional problems can help school leaders and teachers design their approaches to meet the specific needs of each gender. Schools and classes play a crucial role to adolescents’ mental health and knowledge about differences between boys and girls can lead to more informed strategies and changes that create a more supportive and inclusive environment for all adolescents.

Research on the school environment and mental health

Positive mental health among adolescents includes a sense of identity and self-worth, sound social relationships, the ability to learn, and the ability to use developmental challenges and cultural resources to maximize growth (Gustafsson et al., Citation2010). Poor mental health and mental health challenges are used as collective terms that include mental disorders and mental problems. Mental disorders like depression and anxiety affect approximately 3–5% of those aged 13 to 17 years in western countries, including Norway (Reneflot et al., Citation2018; Thorslund et al., Citation2020). Mental problems do not necessarily satisfy the criteria for a diagnosis, but they refer to symptoms that have a significant negative impact on well-being, learning, daily tasks and socializing with others. The prevalence of mental problems in Norway is about 20% among those aged 15 to 17 years (Morin, Citation2021), and similar numbers are reported in other European countries (Belfer, Citation2008; Rehm & Shield, Citation2019).

Previous studies indicate that boys act out more externalizing problems than girls, and that girls are affected by internalizing mental problems to a greater extent than boys (Campbell et al., Citation2021). Some studies have indicated that adolescents with externalizing problems were more likely to receive help than those with internalizing problems (Heiervang et al., Citation2007). One reason might be that externalizing problems were more visible and disruptive to the classroom environment than internalizing problems, leading teachers to perceive externalizing problems as more serious and concerning (Splett et al., Citation2019). Internalizing problems are not typically expressed outwardly through behavior and adolescents with internalizing problems are less likely to seek help or are less often identified as needing support (ibid.; Zee & Rudasill, Citation2021).

The focus of this study is emotional problems. Symptoms of emotional problems include feeling unhappy or downhearted, feeling fear or being scared, nervousness, complaining about headaches or stomachaches, and having many worries (Goodman et al., Citation2000; Helsen et al., Citation2000; Stormont et al., Citation2011). The extent of emotional problems among adolescents has increased over time both in Norway and other countries, particularly among girls (Bor et al., Citation2014; Choi, Citation2018). It must be noted that adolescents’ emotional problems depend not only on the objective challenges or the stressors they are exposed to, but also on how they subjectively evaluate the situation (Haugan et al., Citation2021).

School level, school class level and educational program

All Norwegian adolescents have the right to upper secondary education. Upper secondary schools in Norway provide different education programs in classes of 15–30 adolescents with one or two teachers. The school is seen as central to promoting adolescents’ health and well-being. Several studies suggest the importance of considering the hierarchical structure of data when analyzing the effect of the school environment on different outcomes such as academic performance, physical activity, and mental health (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Sellström & Bremberg, Citation2006; Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2018). The compositional explanation of variations between schools and classes focuses on student diversity such as demographics, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. The contextual explanation, however, focuses on the way the school is structured and managed, the prevailing norms and values, the physical environment, and social factors like peer relationships and teacher-student relationships (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Wang et al., Citation2018). Variations in risks of emotional problems between peers in the same school and/or class may be related to the fact that they share courses and teaching staff and belong to the same peer group. Some studies have examined the transfer of moods, behaviors, attitudes, and emotions among people in groups, and attitudes towards mental health and emotional problems may ‘spread’ in a class or school (Christakis & Fowler, Citation2013; Danielsen et al., Citation2010).

In prior studies, school-level effects varied substantially according to the study group and the type of outcome. The variation explained by school-level factors on mental health and well-being [interclass correlation (ICC) = 1–5%] was lower than physical activity and academic performance (ICC = 5–10%) (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Morin, Citation2021; Sellström & Bremberg, Citation2006; Johansen, Citation2022). Studies indicated that class-level effects for explaining the adolescents’ outcomes in mental health and well-being were substantial (ICC = 4–12%) (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Wang et al., Citation2018).

Upper secondary schools provide programs for general and vocational studies. General study programs prepare for studies at university or college and the vocational programs prepare for the labor market (Nylund et al., Citation2018). There are several reasons to investigate the distribution of emotional problems in general studies and vocational programs. First, vocational programs are more gender-segregated than general studies, with girls dominating in caregiving and health and boys dominating in building and construction (Lorentzen & Vogt, Citation2022). Second, general studies is considered more attractive than vocational studies for adolescents with good grades (Vogt et al., Citation2020), whereas a study found that adolescents with early onset of emotional problems had lower grades and more often chose vocational programs (van Batenburg-Eddes & Jolles, Citation2013). Third, adolescents pursuing vocational programs often have parents with lower socioeconomic status and less educational attainment than parents of those in general studies (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Nylund et al., Citation2018). Fourth, adolescents in vocational studies were found to be less engaged in their studies and more likely to develop negative attitudes about themselves and their school than adolescents in general studies (Nylund et al., Citation2018; van Houtte & Stevens, Citation2009). Thus, it is also important to investigate whether the distribution of emotional problems vary between study programs.

Social support

Social support can be thought of as the individual’s perceptions of general support or specific supportive behaviors (available or enacted upon) from people in their social network, which enhances their functioning and/or may buffer them from adverse outcomes (Lyell et al., Citation2020; Malecki & Demary, Citation2002). Studies have found that adolescents with high perceived levels of social support from peers, teachers and parents have better academic performance, better social skills, and fewer mental problems (Malecki & Demaray, Citation2002; Morin, Citation2021). Some studies indicated a stronger relation between social support and mental problems among girls than boys, and that girls were more susceptible to negative consequences related to a lack of social support (Dalen, Citation2014; Noret et al., Citation2020; van Droogenbroeck et al., Citation2018). Moreover, the relationship between social support and mental problems depended on the source of support, with these associations also varying by gender (Helsen et al., Citation2000; Lyell et al., Citation2020)

Several studies have shown that peer support and being liked and accepted by peers was essential for adolescents positive development (Colarossi & Eccles, Citation2003; van Droogenbroeck et al., Citation2018). Adolescents who experience positive, caring, and stable relationships with peers were more likely to feel included and belonging, leading to positive emotions. Conversely, those who encountered low-quality relationships or were less socially included were more likely to experience mental health difficulties (Krane et al., Citation2016; Tian et al., Citation2015).

A wide range of research revealed that due to day-to-day contact, teachers were important for identifying emerging mental problems among adolescents (Stormont et al., Citation2011). Moreover, teachers facilitated positive mental health through instrumental and emotional support (Krane et al., Citation2016; Tian et al., Citation2015). Instrumental support is related to the practical assistance and subject-related guidance that teachers provide for individual adolescents. Emotional support is related to adolescents’ perceptions of the extent to which teachers value, accept, and respect them as people (Federici & Skaalvik, Citation2013). Adolescents might experience practical help in school-related situations as a sign that a teacher cares, and the division between instrumental and emotional support is not always clear in empirical research.

Finally, parents are a significant source of comfort for adolescents, acting as a ‘secure base’. Greater perceptions of family support were associated with fewer emotional issues during adolescence (Helsen et al., Citation2000). Some studies report a movement in social support during adolescence from the family to peers. This shift in influence was probably because many adolescents spent less time with parents and more time with peers at school and after school (Collins & Laursen, Citation2004).

Research question and expectations

The research question asked in this study was: What connections are there between aspects of the school environment and emotional problems amongst girls and boys? Aspects of the school environment include school level, class level, education program, and social support from peers, parents, and teachers. The following hypotheses were formulated:

H1 Emotional problems vary significantly among schools and classes. The literature review indicated that schools and particularly classes could be influential to the distribution of emotional problems among adolescents.

H2 Emotional problems are higher in vocational programs than general study programs. The literature review indicated a difference in the distribution of emotional problems between education programs.

H3 Emotional problems are connected to the degree of perceived support from peers, teachers, and parents. The literature review indicated that adolescents with high perceived levels of social support reported fewer emotional problems and that emotional problems of girls could be more closely related to the level of social support than for boys.

Materials and methods

Data collection and sample

The data used in this paper were part of a larger data collection and research project on adolescents’ perceptions about their life in school. The primary focus of the study was to investigate and gain insights into academic, social, and relational aspects of school life among adolescents. The data can be described as a convenience sample (McQueen & Knussen, Citation2006). All 16 upper secondary schools (USS) in Sør-Trøndelag county were invited to take part in the study. Three schools chose not to participate, resulting in a sample of 13 schools for the study.

Sør-Trøndelag county was chosen for data collection for several reasons. First, the county offered a diverse representation of urban schools and rural schools, which ensured a broad perspective on adolescents’ school life experiences. Second, the county comprised schools with all types of general and vocational educational programs, which allowed the researchers to explore different contexts within the educational system. Finally, relevant demographic characteristics of students and schools in this county were similar to the national population, thus enhancing the generalizability of the study’s findings. Overall, Sør-Trøndelag county provided a very good setting for obtaining valuable insights into adolescents’ perceptions of their life in school.

The survey was administered at the school, according to instructions from members of the research team. The paper-based questionnaire covered the following topics: demographic background, aspects of social life in school, social support, mental health, academic achievements, motivation, drop-out, and more. The questionnaires were returned to the research team in closed envelopes. The participants were informed in advance that the study was voluntary and that they were considered to have given their consent by answering the questionnaire.

The study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Norwegian Social Data Services (approval ID: 42443). This approval signifies that the research complied with the relevant ethical and legal guidelines, ensuring the protection of participants’' rights and privacy. The study adhered to the necessary procedures for obtaining informed consent from the participants, informing them in advance that their participation was voluntary.

The sample consisted of 2,120 adolescents in Level II in USS, aged 17 and 18 years. The response rate was satisfactory (79%), both overall and in the participating schools (response rates between 70-90%). The satisfactory response rate can be attributed to the convenience of organizing the survey during school hours and the relevance of the research topic. There were some variations in response rates between schools, and this could be related to to reasons such as variations in teacher organization, the timing of information dissemination about the survey, and students absent on the days of the survey not having an opportunity to participate. The sample was representative regarding gender, education program (good distribution of adolescents in general studies and vocational education), academic achievement (similar distribution of grades as the population), geography (including both schools in the periphery and urban schools), and school size.

Variables

The multilevel models included the individual level, the class level, and the school level. There were 2120 adolescents (level 1) in 129 school classes (level 2) across 13 schools (level 3). The average number of adolescents in the study from the same class was 16, ranging from 4 to 30.

The dependent variable—emotional problems—was constructed from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman et al., Citation2000). SDQ is a well-established and extensively researched measurement instrument for assessing emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. The psychometric properties of the SDQ have been assessed in several studies in many countries and in different age groups, and these studies have concluded that the reliability and validity were good (Essau et al., Citation2012; Kersten et al., Citation2016; Van Roy et al., Citation2008). The response categories in SDQ were ‘Not true’ (0), ‘Somewhat true’ (1), and ‘Certainly true’ (2). Emotional problems were measured by five statements that were each scored from 0–2, making up a sum score from 0 to 10. Examples of statements were: ‘I am nervous in new situations’, ‘I easily lose confidence’, and ‘I worry a lot’. In line with previous studies (Essau et al., Citation2012; Van Roy et al., Citation2008), a principal component analysis showed that the internal consistency of the emotional problems scale was satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77). Higher scores on emotional problems suggest more difficulties, with any score over 7 considered a sign of poor emotional well-being (abnormal score). Therefore, in addition to analyzing emotional problems as a continuous scale (0-10), we also comment on the share of boys and girls with abnormal scores. Descriptive statistics of emotional problems are presented in the results section.

The independent variables included education program, teacher support, peer support, parental support, gender, mother′s education level, and average grade. The scales for social support were based on Malecki and Elliott (Citation1999) and Malecki and Demary (Citation2002). Previous assessments of the psychometric properties of the social support scales concluded that the reliability and validity of teacher support, peer support, and parental support were good (Mjaavatn et al., Citation2019; Haugan et al., Citation2019). The response categories for all statements were on a six-point scale, ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly agree’ (6).

Perceived teacher support was constructed by eight statements that included instrumental support (e.g. ‘My teachers explain to me what I do not understand’) and emotional support (e.g. ‘My teachers care about me’). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.93.

Perceived peer support contained four items that measured adolescents’ perceptions of having supportive relations to their peers and their sense of belonging to the class. Examples of statements were: ‘Other students in my class do things with me’ and ‘Other students in my class say positive things about me’. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.85.

Perceived parental support was constructed by four items that measured whether the adolescents found that their parents were supportive both academically and emotionally. Examples of statements were: ‘My parents support me if I have problems’ and ‘My parents are interested in my schoolwork’. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.92.

Results were compared for boys (reference category) and girls. The education programs were divided into general studies (reference category) and vocational education programs. Mother’s education level was divided into low educational attainment (upper secondary school, reference category), middle educational attainment (bachelor’s degree), and high educational attainment (master’s degree or higher). The average grade in Norwegian, Mathematics, and English in the last semester before the data collection was used as an indicator of academic achievement. The variable ranged from 1 (lowest grade) to 6 (highest grade).

Statistical analysis

To construct scale variables (previous section), we used principal component analysis with oblique rotation (direct-oblimin). Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure internal consistency. We also analyzed bivariate correlations in scale variables to make sure that these were of adequate strength (r = 0.3–0.7).

The results section presents the descriptive analysis. We analyzed bivariate correlations using a mix of different coefficients. We compared our results using the emotional problems scale data with British norm data and a previous Norwegian study.

Multilevel modeling is performed to examine connections between school, class, and individual factors and emotional problems. Multilevel models allow researchers to separate contextual effects from intra-individual effects; it is a preferred technique for modeling nested data (Hoyle & Gottfredson, Citation2015; Maas & Hox, Citation2005; Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012). Moreover, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) describes how strongly units in the same group resemble each other, and when multiplied by 100, the ICC can be interpreted as the percentage of variance attributed to the given level (Andersson et al., Citation2009). The variance attributable to differences between schools and classes is analyzed both without and with adjustment for independent variables. To investigate variations between boys and girls, multilevel models are presented for the whole sample and for boys and girls separately.

An important issue in multilevel models is what constitutes a sufficient higher-level sample size. Several rules of thumb about sample size are available in the literature, with propositions based on simulation, experience, and analytical work (Hoyle & Gottfredson, Citation2015). There is general agreement among statisticians and researchers that 100 or more units at the highest level is sufficient (Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012). Some researchers have argued that 50 units are needed to give accurate estimates (Maas & Hox, Citation2005), whereas others argue that multilevel modeling can be used when the number of groups is larger than 10 (Hoyle & Gottfredson, Citation2015; Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012). Studies and simulations indicate that estimates of the regression coefficients are quite accurate in small samples, but that estimates of standard errors are biased (Maas & Hox, Citation2005). Thus, when sample sizes are small and close to 10, the researcher must be aware of the possibility of statistical problems and unreliable results. This study includes 13 schools, which is enough to separate schools as an analytical level, but we are aware that estimates for the school level are less accurate.

Results

presents an overview of the characteristics of the respondents. The sample comprised 50% boys and 50% girls. 37% of respondents had a mother with low educational attainment, 29% with middle educational attainment, and 34% with high educational attainment. 52% of the respondents went to general studies and 48% went to vocational education programs. The average grade in Norwegian, Mathematics, and English was 4.0. The average score of perceived parental support was 5.1, whereas the average score of perceived peer support was 4.8, and the average score of perceived teacher support was 4.3.

Table 1. An overview of the characteristics of the respondents.

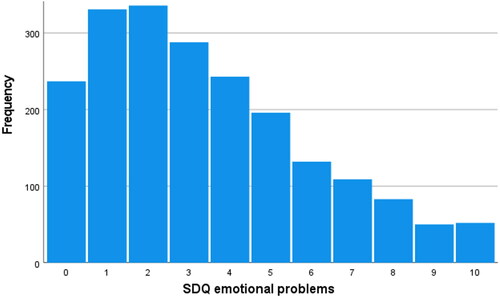

shows the distribution of emotional problems. The average score was 3.4 and standard deviation was 2.5. 14% of the adolescents had a score of 7 or higher, and that is considered abnormal.

Figure 1. Distribution of dependent variable SDQ emotional problems in Sør-Trøndelag county, upper secondary school level II (USSII), 2017, n = 2057.

compares the share of boys and girls with normal and abnormal scores on emotional problems in three different studies. According to the British norm data, about 5% of boys and girls would score abnormal (Goodman et al., Citation2000). Girls reported abnormal scores on emotional problems more often than boys in the Akershus study, with 11% vs. 4% (Rødje et al., Citation2004). In our study, 24% of the girls reported abnormal scores on emotional problems, compared to 4% for the boys. Thus, the share of boys with abnormal levels of emotional problems was stable over time, whereas the share of girls reporting abnormal scores rose significantly.

Table 2. Comparison of the share of adolescents with normal/abnormal score on emotional problems in Sør-Trøndelag USSII compared with Akershus and British norms.

presents the correlation matrix for the variables in the study, using a mix of different correlation coefficients. As expected, there was a medium strong negative positive correlation between girls and emotional problems (r = 0.40). Moreover, the support variables correlated negatively with emotional problems (ranging from r = −0.28 to r = −0,32). The strongest correlations in the matrix were between support from peers and support from parents (r = 0.48) and teachers (r = 0.48). Thus, multicollinearity was not a concern.

Table 3. Correlation matrix using a mix of different coefficients: Pearson’s r (two variables on interval/ratio scale), point biserial correlation (dichotomous variable and interval/ratio scale variable) and phi (two dichotomous variables).

gives the results from the multilevel models for all adolescents in the sample. The analyses showed relatively good fit, and the Pseudo R2 was 32% in Model III.

Table 4. Results from multilevel modeling analyses predicting participating adolescents’ emotional problems, interclass correlation coefficient (ICC), estimates of fixed effects, standard errors (in parentheses), and p-values (**=significant at 0.01, *=significant at 0.05).

Model I showed that most of the variance in emotional problems was accounted for by individual level factors (88%), but there were also statistically significant class-level effects (9%) and school-level effects (3%). Model II included variables that characterized adolescents with different risks of emotional problems (gender, mother′s education level, and grades), and this inclusion reduced class-level effects (4%) and school-level effects (2%). Model III adjusted for factors like social support and education program, and then class-level effects (2%) and school-level effects (1%) were further reduced. Thus, when comparing results for Models I, II, and III, it seems likely that some of the class-level effect and school-level effects were explained by the composition of the student group and some by the education context.

Model II showed that girls had a much higher score on emotional problems compared with boys. Adolescents with a mother with low educational attainment reported higher scores on emotional problems compared to adolescents with a mother with high educational attainment.

Model III showed that support from peers correlated strongly with emotional problems. Parental and teacher support was also strongly connected to emotional problems. Moreover, those in vocational education programs reported higher scores on emotional problems compared to those in general studies.

presents the results from multilevel models split between girls and boys. Vocational education was a significant variable in the model for girls, but it had less significance for boys. Moreover, social support seemed to have a stronger correlation for emotional problems among girls compared with boys. The most important factor was peer support.

Table 5. Results from multilevel modeling analyses predicting emotional problems among boys and girls, interclass correlation coefficient (ICC), estimates of fixed effects, standard errors (in parentheses), and p-values (**=significant at 0.01, *=significant at 0.05).

Assumptions for the multilevel models ( and ) were checked. There were no problems with multicollinearity, relations between the independent variables and emotional problems were linear, and the assumption of homoscedasticity was fulfilled. As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded the school-level from the multilevel model. The result was that the class-level effect rose to almost 12%, whereas individual level factors still accounted for about 88% of the variance.

Discussion

The present study explored associations between adolescents’ perceptions of emotional problems and different aspects of the school environment.

H1 Emotional problems vary significantly among schools and classes

This hypothesis was confirmed. Most of the variation in emotional problems is found at the individual level (88%), implying that factors unique to each person play a substantial role in the distribution of emotional problems. There is also a substantial class-level effect (9%) on emotional problems and a smaller school-level effect (3%) (see ). The importance of the class in explaining emotional problems can find support in previous studies indicating that mental health and behavioral problems significantly varied among classes (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Konu et al., Citation2002; Wang et al., Citation2018). The school-level effect is in line with previous research suggesting that school-level factors have quite a small effect on adolescents’ mental health (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Dalen, Citation2014).

Multiple studies have shown that girls report higher rates of emotional problems compared to boys (Bor et al., Citation2014; Campbell et al., Citation2021; Choi, Citation2018; Haugan et al., Citation2021). Classes with a high proportion of girls typically have higher scores on emotional problems than classes with fewer girls, and the class-effect was stronger for girls’ score on emotional problems than for boys (see ). The relationship between the gender composition in a class and the distribution of emotional problems is interesting, in particular since prior studies have shown that girls, to a greater extent than boys, influence each other and exaggerate a broad range of mental problems, such as emotional problems and stress (Brolin-Låftman et al., Citation2013; Dalen, Citation2014). There might be specific social dynamics, peer interactions, or communication patterns in classrooms with more girls that could contribute to elevated emotional problems.

The analyses also indicate that some of the class-level effect is explained by contextual factors. Previous studies found that the interactions between the peers and between adolescents and teachers affected adolescents’ emotions and behavior at class level (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Wang et al., Citation2018). The impact of social dynamics is not limited to individual students, but can also affect the overall classroom environment: A positive classroom atmosphere, fostered by peer and teacher support, can contribute to fewer emotional problems and better well-being for all students in the class. A possible contextual factor is that emotional problems may ‘spread’ in a class or school. Studies on emotional and social contagion have examined the ‘spread’ of obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, influenza, happiness, loneliness, depression, suicide, and tastes in music, books, and movies (Christakis & Fowler, Citation2013). These studies have shown that starting or quitting smoking spread through social ties, that having a friend who committed suicide increased the likelihood of suicidal thoughts or attempts, and that affective states such as happiness, loneliness, and depression tend to cluster (ibid.). In line with this research, we suggest that adolescents with emotional problems may affect peers and increase the risk of them developing emotional problems, even if they have no problems initially (Danielsen et al., Citation2010). The possible influence of teachers is also relevant, and a mild positive correlation has been found between adolescents’ mental health problems and the mental health of teachers (Wang et al., Citation2018).

H2 Emotional problems are higher in vocational programs than general study programs

This hypothesis was partly confirmed. We find that girls in vocational programs have more emotional problems than girls in general studies, whereas there is no difference for emotional problems between boys in vocational programs and general studies (see ). A possible reason for the connection between education program and emotional problems among girls is the selection of individuals with mental health problems into various education programs. Studies have shown that adolescents with early onset of emotional problems are more likely to be underachievers in lower secondary school (van Batenburg-Eddes & Jolles, Citation2013) and more likely to choose practical, vocational programs. Another possible point is that vocational programs are more gender-segregated than general studies (Lorentzen & Vogt, Citation2022), As mentioned previously, in classes with higher proportions of girls, there is the possibility for emotional problems ‘spreading’ and thus increasing the risk of more girls developing/reporting emotional problems (Dalen, Citation2014; Danielsen et al., Citation2010). The opposite is also true; in classes with higher proportions of boys, emotional problems are exposed to a much lesser degree and do not ‘spread’. Further research is needed to understand gender-based differences in the occurrence of emotional problems among students in vocational programs and general studies.

H3 Emotional problems are connected to the degree of perceived support from peers, teachers, and parents

The hypothesis was confirmed. High levels of perceived peer, teacher, and parental support are associated with lower levels of self-reported emotional problems. Previous studies found the significant role of perceived social support in mental health contexts (Colarossi & Eccles, Citation2003; Lyell et al., Citation2020; Mjaavatn et al., Citation2019; Morin, Citation2021). The strongest correlation for both girls and boys were between peer support and emotional problems (see and ). Considering that our study group is aged 17 and 18 years, this correlates well with previous research that found a shift in social support during adolescence from the family to peers (Collins & Laursen, Citation2004).

For both boys and girls, high levels of perceived peer, teacher, and parental support are associated with lower levels of emotional problems. However, support from peers, teachers, and parents seems to be more closely correlated to emotional problems for girls compared with boys. Previous studies found that girls had stronger social networks than boys, and that girls are more likely to seek closeness in relationships and talk about emotions and mental problems with peers, teachers, and parents (Lyell et al., Citation2020; Noret et al., Citation2020; van Droogenbroeck et al., Citation2018). Girls are more open about emotional problems, and the presence of a supportive and nurturing social network might be more critical for girls’ emotional well-being compared with boys.

The study also confirmed previous research about an increase in self-reported emotional problems over time for girls, but not for boys (see and ) (Bor et al., Citation2014; Choi, Citation2018; Haugan et al., Citation2021; Rødje et al., Citation2004). Girls and boys seem to experience and evaluate emotional problems differently. The growth in self-reported emotional problems over time could imply that more girls struggle with mental health problems than previously. It could also relate to the way girls report health complaints, and that it is now more common for girls to be open about emotional problems.

Very few boys report emotional problems. In determining reasons for this, several considerations arise. One is that the low levels of emotional problems among boys could be a social norm among adolescent boys to be strong, and it could be seen as a sign of weakness and not masculine to be open about emotional problems. Studies have shown that boys are more concerned with concealing internalization problems and feel less comfortable reporting about their feelings than girls (Granrud et al., Citation2020). A second important consideration is the potential expression of emotional problems through externalizing symptoms among boys. Externalizing symptoms such as conduct problems, hyperactivity and aggression are more frequently observed among boys than girls (Campbell et al., Citation2021). A third consideration is that there might be measurement errors and a bias to detecting symptoms of emotional problems that are more common for girls than boys. If so, further study is needed to clarify which symptoms truly describe boys’ experiences of emotional problems.

There are limitations to the findings. First, the quantitative data used were cross-sectional and based on adolescents’ self-reports. Self-reported cross-sectional data do not provide causal explanations, as they only reflect the individual’s own perspective and do not necessarily reflect the true underlying causes of the observed relationships. It is particularly important to consider that connections can go both ways, for instance when discussing the relationship between emotional problems and social support. The use of self-reported data makes it likely that the study may suffer from common method bias arising from the characteristics of the items, the measurement context, and matters related to the respondent and their behavior (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012).

Second, the analysis showed a substantial class-level effect and a smaller school-level effect on emotional problems. Regarding sample size, we might consider that estimates of the class-level effect are quite accurate (Hoyle & Gottfredson, Citation2015; Maas & Hox, Citation2005; Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012), but there is more uncertainty about the accuracy of the school-level effect.

There is more to learn about relations between the school environment and emotional problems. To investigate causal relations, it would be of interest to test the associations between aspects of the school environment and adolescents’ emotional problems via longitudinal and experimental designs. One could also argue that connections between the school environment and emotional problems are better understood when we combine information from several informants (e.g. adolescents, teachers, parents), and go into qualitative studies with in-depth descriptions about variations in emotional problems between schools and classes. We also think that qualitative studies could shed light on gender-based differences in the prevalence of emotional problems among students in vocational programs and general studies. Finally, the interdisciplinary topic ‘health and life skills’ was introduced at all education levels in 2020 and is a relevant topic for future studies, particularly in relation to its potential impact on improving mental health support for adolescents.

Conclusion

This paper asked the following research question: What connections are there between aspects of the school environment and emotional problems amongst girls and boys? First, the study found that girls reported emotional problems more often than boys. Second, the study showed that emotional problems varied significantly between classes. Third, that emotional problems were related to peer, teacher, and parental support, and such support was more important for girls than boys. Fourth, that girls in vocational programs had more emotional problems than girls in general studies, whereas no such difference was found for boys.

Given these findings, we can point to various potential implications for practice. The significant gender difference in the prevalence of emotional problems underscores the need for gender-differentiated approaches in addressing mental health challenges. Targeted strategies could also be considered in schools and classes where there is suspicion of extensive emotional problems, including providing training for teachers on the importance of social support, recognizing signs of emotional problems, and understanding gender differences in emotional problems. Adolescents must also learn about mental problems, and how important it is that they contribute to create a comfortable classroom climate with good relations between peers and between themselves and teachers. In that respect, the introduction of the topic health and life skills has given an opportunity for adolescents to learn about a variety of topics related to mental health and well-being.

Ethics approval statement

The study was ethically approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), ID: 42443.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Per Frostad and Associate Professor Per Egil Mjaavatn for giving us the opportunity to take part in their research project called “Life in schools”. This project has been a great experience. We would also like to thank all the students that participated in this project.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ingvild Røsand

Ingvild Røsand is a Ph.D. Candidate at the Department of Education and Lifelong Learning at NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Her professional research interests include adolescents’ mental health and well-being, stress, coping, social support, and a mixed-methods approach.

Vegard Johansen

Vegard Johansen is a Professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. He is Deputy Head of Research at the Department of Education and Lifelong Learning. He has written extensively about entrepreneurship education and project work in schools, children’s welfare and social policy, and everyday life in secondary schools. Johansen has led many national and international research projects. He teaches research methods courses at Bachelor, Master and PhD-levels.

References

- Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., Rescorla, L. A., Turner, L. V., & Althoff, R. R. (2016). Internalizing/externalizing problems: Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(8), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.012

- Andersson, H. W., Bjørngaard, J. H., Kaspersen, S. L., Wang, C. E., Skre, I., & Dahl, T. (2009). The effects of individual factors and school environment on mental health and prejudiced attitudes among Norwegian adolescents. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(5), 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0099-0

- Belfer, M. L. (2008). Child and adolescent mental disorders: the magnitude of the problem across the globe. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 49(3), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01855.x

- Bor, W., Dean, A. J., Najman, J., & Hayatbakhsh, R. (2014). Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(7), 606–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414533834

- Brolin-Låftman, S., Almquist, Y. B., & Östberg, V. (2013). Students’ accounts of school- performance stress: A qualitative analysis of a high-achieving setting in Stockholm Sweden. Journal of Youth Studies, 16(7), 932–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.780126

- Campbell, O. L., Bann, D., & Patalay, P. (2021). The gender gap in adolescent mental health: A cross-national investigation of 566,829 adolescents across 73 countries. SSM - Population Health, 13, 100742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100742

- Choi, A. (2018). Emotional well-being of children and adolescents: Recent trends and relevant factors. OECD Education Working Paper No. 169.

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2013). Social contagion theory: Examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Statistics in Medicine, 32(4), 556–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5408

- Colarossi, L. G., & Eccles, J. S. (2003). Differential effects of support providers on adolescents’ mental health. Social Work Research, 27(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/27.1.19

- Collins, W. A., & Laursen, B. (2004). Changing relationships, changing youth: Interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 24(1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431603260882

- Dalen, J. D. (2014). Gender differences in the relationship between school problems, school class context and psychological distress: Results from the Young-HUNT 3 study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(2), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0744-5

- Danielsen, A. G., Wiium, N., Wilhelmsen, B. U., & Wold, B. (2010). Perceived support provided by teachers and classmates and students’ self-reported academic initiative. Journal of School Psychology, 48(3), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2010.02.002

- Essau, C. A., Olaya, B., Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, X., Pauli, G., Gilvarry, C., Bray, D., O'Callaghan, J., & Ollendick, T. H. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire from five European countries. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1364

- Federici, R. A., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2013). Students’ perceptions of emotional and instrumental teacher support: Relations with motivational and emotional responses. International Education Studies, 7(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n1p21

- Goodman, R., Ford, T., Simmons, H., Gatward, R., & Meltzer, H. (2000). Using the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 177(6), 534–539. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.6.534

- Granrud, M. D., Bisholt, B., Anderzèn-Carlsson, A., & Steffenak, A. K. M. (2020). Overcoming barriers to reach for a helping hand: Adolescent boys’ experience of visiting the public health nurse for mental health problems. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 649–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2020.1711529

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Allodi Westling, M., Alin Åkerman, B., Eriksson, C., Eriksson, L., Fischbein, S., Granlund, M., Gustafsson, P., Ljungdahl, S., & Ogden, T. (2010). School, Learning and Mental Health: A systematic review. The Royal Swedish Academy of Science.

- Haugan, J. A., Frostad, P., & Mjaavatn, P. E. (2019). A longitudinal study of factors predicting students’ intentions to leave upper secondary school in Norway. Social Psychology of Education, 22(5), 1259–1279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09527-0

- Haugan, J. A., Frostad, P., & Mjaavatn, P. E. (2021). Girls suffer: The prevalence and predicting factors of emotional problems among adolescents during upper secondary school in Norway. Social Psychology of Education, 24(3), 609–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09626-x

- Heiervang, E., Stormark, K. M., Lundervold, A. J., Heimann, M., Goodman, R., Posserud, M. B., Ullebø, A. K., Plessen, K. J., Bjelland, I., Lie, S. A., & Gillberg, C. (2007). Psychiatric disorders in Norwegian 8–10-year-olds: An epidemiological survey of prevalence, risk factors, and service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(4), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e31803062bf

- Helsen, M., Vollebergh, W., & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(3), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005147708827

- Hoyle, R. H., & Gottfredson, N. C. (2015). Sample size considerations in prevention research. Applications of multilevel modeling and structural equation modeling. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 16(7), 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0489-8

- Johansen, V. (2022). Mini-companies and school performance in four European countries. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 47(1), 128–140.

- Kersten, P., Czuba, K., McPherson, K., Dudley, M., Elder, H., Tauroa, R., & Vandal, A. (2016). A systematic review of evidence for the psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(1), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415570647

- Konu, A. I., Lintonen, T. P., & Autio, V. J. (2002). Evaluation of well-being in schools–A multilevel analysis of general subjective well-being. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 13(2), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1076/sesi.13.2.187.3432

- Krane, V., Karlsson, B., Ness, O., & Kim, H. S. (2016). Teacher-student relationship, student mental health, and dropout from upper secondary school: A literature review. Scandinavian Psychologist, 3, e11. https://doi.org/10.15714/scandpsychol.3.e11

- Lorentzen, T., & Vogt, K. C. (2022). Gendered transition structures: Life course patterns after completion of gender-segregated vocational education in Norway. Journal of Education and Work, 35(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.2009781

- Lyell, K. M., Coyle, S., Malecki, C. K., & Santuzzi, A. M. (2020). Parent and peer social support compensation and internalizing problems in adolescence. Journal of School Psychology, 83, 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.08.003

- Malecki, C. K., & Demary, M. C. (2002). Measuring perceived social support: Development of the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS). Psychology in the Schools, 39(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10004

- Malecki, C. K., & Elliott, S. N. (1999). Adolescents’ ratings of perceived social support and its importance: Validation of the Student Social Support Scale. Psychology in the Schools, 36(6), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(199911)36:6<473::AID-PITS3>3.3.CO;2-S

- McQueen, R. A., & Knussen, C. (2006). Introduction to research methods and statistics in psychology. Pearson.

- Mjaavatn, P. E., Buseth, L. H., & Frostad, P. (2019). Mest støtte til de faglig sterke? En studie av sammenhengen mellom opplevd lærerstøtte og prestasjonsnivå i ungdomsskole og videregående skole [Most support for the academically strong? A study of the relationship between perceived teacher support and achievement level in secondary and upper secondary school]. Spesialpedagogikk, 84(1), 52–63.

- Morin, A. H. (2021). Influence of the psychosocial school environment on adolescents’ mental health, wellbeing, and loneliness: Impact of a psychosocial school programme and other factors. NTNU

- Maas, C. J. M., & Hox, J. J. (2005). Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling methodology. Methodology, 1(3), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241.1.3.86

- Nikstat, A., & Riemann, R. (2020). On the etiology of internalizing and externalizing problem behavior: A twin-family study. PloS One, 15(3), e0230626. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230626

- Noret, N., Hunter, S. C., & Rasmussen, S. (2020). The role of perceived social support in the relationship between being bullied and mental health difficulties in adolescents. School Mental Health, 12(1), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09339-9

- Nylund, M., Rosvall, P. Å., Eiríksdóttir, E., Holm, A. S., Isopahkala-Bouret, U., Niemi, A. M., & Ragnarsdóttir, G. (2018). The academic–vocational divide in three Nordic countries: Implications for social class and gender. Education Inquiry, 9(1), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2018.1424490

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Rehm, J., & Shield, K. (2019). Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0

- Reneflot, A., Aarø, L. E., Aase, H., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Tambs, K., & Øverland, S. (2018). Psykisk helse i Norge [Mental health in Norway]. Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

- Rødje, K., Clench-Aas, J., van Roy, B., Holmboe, O., & Müller, A. M. (2004). Helseprofil for barn og ungdom i Akershus: Ungdomsrapport [Health profile for children and adolescents in Akershus: Adolescence report]. Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten.

- Sellström, E., & Bremberg, S. (2006). Is there a “school effect” on pupil outcomes? A review of multilevel studies. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(2), 149–155.

- Snijders, T., & Bosker, B. (2012). An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Splett, J. W., Garzona, M., Gibson, N., Wojtalewicz, D., Raborn, A., & Reinke, W. M. (2019). Teacher recognition, concern, and referral of children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. School Mental Health, 11(2), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-09303-z

- Stormont, M., Reinke, W., & Herman, K. (2011). Teachers’ knowledge of evidence-based interventions and available school resources for children with emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of Behavioral Education, 20(2), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-011-9122-0

- Thorslund, J., McEvoy, P. M., & Anderson, R. A. (2020). Group metacognitive therapy for adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 625–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22914

- Tian, L., Zhao, J., & Huebner, E. S. (2015). School-related social support and subjective well-being in school among adolescents: The role of self-system factors. Journal of Adolescence, 45(1), 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.09.003

- van Batenburg-Eddes, T., & Jolles, J. (2013). How does emotional wellbeing relate to underachievement in a general population sample of young adolescents: a neurocognitive perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 673. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00673

- van Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B., & Keppens, G. (2018). Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1591-4

- van Houtte, M., & Stevens, P. A. (2009). Study involvement of academic and vocational students: Does between-school tracking sharpen the difference? American Educational Research Journal, 46(4), 943–973. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209348789

- Van Roy, B., Veenstra, M., & Clench-Aas, J. (2008). Construct validity of the five-factor Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in pre-, early, and late adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 49(12), 1304–1312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01942.x

- Vogt, K. C., Lorentzen, T., & Hansen, H. T. (2020). Are low-skilled young people increasingly useless, and are men the losers among them? Journal of Education and Work, 33(5-6), 392–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2020.1820965

- Wang, J., Hu, S., & Wang, L. (2018). Multilevel analysis of personality, family, and classroom influences on emotional and behavioral problems among Chinese adolescent students. PLoS One, 13(8), e0201442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201442

- Zee, M., & Rudasill, K. M. (2021). Catching sight of children with internalizing symptoms in upper elementary classrooms. Journal of School Psychology, 87, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2021.05.002