Abstract

In higher education, students’ trust in the university management may affect both mental health and academic self-efficacy. This longitudinal study, conducted during the most challenging course of the COVID-19 pandemic, uses multinomial regression and causal inference to estimate the effects of students’ trust in their universities’ strategies for managing the pandemic, on students’ self-reported changes in mental health and academic self-efficacy. The analyzed sample (N = 2796) was recruited through online advertising and responded to a baseline online survey in the late spring of 2020, with two follow-up surveys five and ten months later. Results show that positive trust in university management of the pandemic protected against experiencing one’s mental health and academic self-efficacy as worse rather than unchanged, both five and ten months after the baseline assessment. The findings emphasize the importance of developing and maintaining trust-building measures between academia and students to support students’ mental health and academic self-efficacy in times of uncertainty.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic brought the need for dealing with uncertainty in human life to the fore, for the global population. During the enforced closure of university campuses, all actors within academia, including lecturers, administrators, developers, and students, rapidly had to adapt to new, challenging circumstances. Notably, the changes involved unfamiliar conditions such as online teaching and assessment (Watermeyer et al., Citation2022; Appleby et al., Citation2022). Whether or not students were able to adapt to these rapid changes successfully is likely to be affected by changes in the bonds of trust between academia and students.

Trust is a widely discussed concept across various disciplines (Mayer et al., Citation1995; Williams, Citation2002; Cook & Schilke, Citation2010; Bormann et al., Citation2021). Overall, trust can be defined as a complex relationship where the trustor agrees to be vulnerable, assuming the trustee will benefit the trustor. Specifically, in relation to higher education, student trust in the university has been defined as ‘the degree to which a student is willing to rely on or have faith and confidence in the college to take appropriate steps that benefit [them] and help [them] achieve [their] learning objectives’ (Ghosh et al., Citation2001). Models of trust development and change emphasize that trust is built on evidence of the other party’s motives and character (Lewicki et al., Citation2006). This evidence then forms the basis for beliefs, predictions, and faith judgments about the party’s likely future. Subsequent evidence and outcomes are used to recalibrate these judgments, which makes trust development a continuously ongoing and dynamic process.

Student trust in universities may have affected mental health and academic self-efficacy, two personal characteristics that dynamically wax and wane over time. Mental health can be defined as a dynamic state of well-being in which individuals realize their abilities, cope with everyday life stressors, are productive, and contribute to their community (WHO, 2022). A recent review shows that the pandemic had negative effects on student mental health (Buizza et al., Citation2022). Academic self-efficacy relates to students’ beliefs in their capacity to organize and perform any actions that are required for given academic attainments (Bandura, Citation1997). Four different sources contribute to the development and change in efficacy beliefs over time (Bandura, Citation1997). Mastery experiences involve personal experiences of success and failure, while social experiences are based on observing the success and failure of others. Efficacy beliefs are also influenced by social persuasion, as well as personal reactions and reflections relating to different life events. Recent research from Sweden showed widespread changes in academic self-efficacy, predominantly negative, during the initial phase of the pandemic (Berman et al., Citation2022).

In relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, we have identified six cross-sectional studies on students’ trust in university management. Calderone & Fosnacht, Citation20232022) compared two cross-sectional samples and reported that trust in US colleges did not differ between students responding to a survey before the pandemic, and during its first wave. Khan et al. (Citation2021) showed that trust in university management had a negative association with distress among international students in China. Defeyter et al. (Citation2021) found that low trust in university management during the pandemic was associated with low levels of mental well-being in UK students. Ballmann et al. (Citation2022) studied Danish and German students and found that lower trust in university COVID-19 regulations was associated with academic frustration. Andersson et al. (Citation2022) reported that lowered academic self-efficacy was associated with low trust in universities’ capacity to manage the lockdown and transition to emergency remote education in Sweden. Finally, Ogunmokun et al. (Citation2022) showed that Cypriot students’ trust in university management mediated the relationship between university crisis response and student attrition intentions.

Given the importance of trust, there is a scarcity of longitudinal research studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic on whether students’ trust in university management has had long-term effects on student mental health and academic self-efficacy. Therefore, this longitudinal study uses causal inference to estimate the effects of students’ perceived trust in academic management on mental health and academic self-efficacy, over the most challenging course of the pandemic. Specifically, the present study’s first aim was to estimate the effects of students’ baseline trust in university management of the pandemic, on self-reported change in mental health and academic self-efficacy 5- and 10-months post-baseline. The second aim was to estimate the effects of students’ trust in university management at 5 months post-baseline, on self-reported change in mental health and academic self-efficacy 10 months post-baseline. Based on the existing cross-sectional studies (Calderone & Fosnacht, 2022; Khan et al., Citation2021; Defeyter et al., Citation2021; Ballmann et al., Citation2022; Andersson et al., Citation2022; Ogunmokun et al., Citation2022), we expected to find that positive trust in university management at both time points would be associated with better mental health and trust at both follow-ups.

Methods

Setting

This longitudinal study was conducted in Sweden. According to the Swedish Higher Education Authority (Citation2022), there are 31 public universities and university colleges with 386,747 registered students (range: 228-39,702), and 75,711 employees (range: 74-9,194). Public Health Agency of Sweden (Citation2022) reports that COVID-19 was introduced in Sweden in early February 2020 with a steady increase in infection during the spring, followed by further intense waves during the winter of 2020 and the spring of 2021. This was followed by another intense wave in the winter of 2021, after which the scope of the pandemic slowly diminished. Due to the pandemic, the Swedish Government decided to stop all on-campus instruction at institutions of higher education on 17 March 2020, in effect introducing an immediate transition to remote education (Lindblad et al., Citation2021). The requirement for remote education continued until the autumn of 2021, with some minor remaining restrictions being eliminated in the spring of 2022.

Participants and procedure

Ethical approval for this study was granted on May 11, 2020, by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. After this date, self-report survey responses were collected online, on three different occasions. The baseline cross-sectional survey was distributed during the initial wave of the pandemic in May 2020. Then, students were contacted again after 5 and 10 months, respectively. This period corresponds roughly to the second and third waves of the pandemic. Recruitment was carried out through announcements on the websites of ten public universities and university colleges as well as the National Association of Student Unions. Interested students clicked on a URL or QR code to access detailed project information and provide digital informed consent, before being asked to respond to a short questionnaire. No compensation was given for participating. At baseline, a total of 4497 consents were recorded from students at 19 universities and university colleges. Of the 4497 baseline responses, 3125 (69.5%) agreed to participate in two follow-ups, yielding 2796 (89.5%) unique e-mail addresses, which constituted the sample size. Follow-up surveys were distributed after 5 and 10 months to participants at these e-mail addresses.

Measures

The three constructs of interest in the present study were each assessed through single-item questions. Trust in university management was assessed with the question ‘How have you experienced your university’s/college’s way of managing the COVID-19 pandemic?’. Students were asked to choose one of the following five response alternatives: ‘Excellent’, ‘Good’, ‘Moderate’, ‘Poor’, and ‘Very poor’. Mental health was assessed with the following question ‘How has your mental health been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic during the past 4 weeks?’. Students were asked to choose one of the four response alternatives: ‘No effect’, ‘My mental health has been worse’, ‘My mental health has been better’, and ‘My mental health has been both better and worse’. The last response alternative allowed students who experienced improved mental health in some respects and poorer mental health in other respects to report this. Finally, academic self-efficacy was assessed with the question ‘How have your studies been going during the past 4 weeks?’ where the five response alternatives were as follows: ‘No change, my studies are going as usual’, ‘My studies have been going worse’, ‘My studies have been going better’, ‘My studies have been going both better and worse (in differing ways)’, and ‘I am not studying at this time’. As for mental health, the response alternatives allowed for students with varied experiences to provide responses.

Analysis

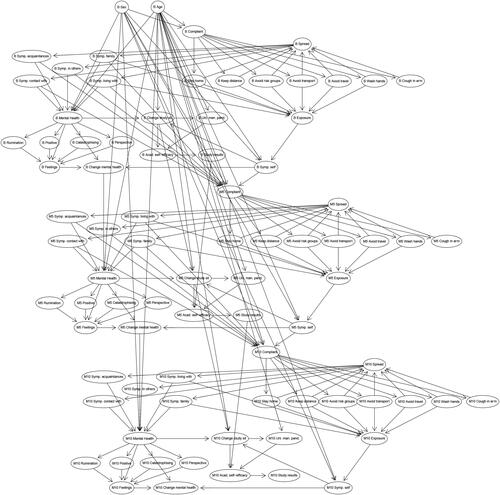

For the present study, there were six estimands of interest related to students’ trust in universities’ management of the pandemic: Effects of baseline trust on mental health (1) and academic self-efficacy (2) at the 5-month follow-up; effects of baseline trust on mental health (3) and academic self-efficacy (4) at 10-month follow-up; effects of 5-month trust on mental health (5) and academic self-efficacy (6) at 10-month follow-up. A directed acyclic graph (), which depicts the causal assumptions made to estimate effects from observational data, was used in conjunction with Pearl’s do-calculus (Pearl, Citation2009) to identify necessary adjustment variables. For estimands 1-4, models were adjusted for baseline age and baseline self-reported change in academic self-efficacy. For estimands 5 and 6, models were adjusted for baseline age and 5-month self-reported change in academic self-efficacy.

Figure 1. Causal assumptions made to estimate effects from observational data. The letter B refers to Baseline data. M5 and M10 refers to the two follow-up assessments. In relation to the variables, the following abbreviations appear: Acad. Self-efficacy = Academic Self-Efficacy; Sit. = Situation; Symp. = Symptoms; Uni. Man. Pand. = University Management of the Pandemic. As part of the statistical analysis plan, a complete list of included variables can be viewed and downloaded from OSF (Bendtsen et al., Citation2022). To improve readability, the figure can be enlarged in the online version of this publication.

Since the response alternatives were nominal—specifically the alternatives allowed students with varied experiences, i.e., both ‘better’ and ‘worse’, to provide responses in relation to mental health and academic self-efficacy—nominal regression was considered appropriate. Multilevel multinomial regression was used to estimate effects, with adaptive intercepts for universities and for subjects in longitudinal models. Models were estimated using Bayesian inference (Bendtsen, Citation2018). Covariates and adaptive intercepts were given standard normal priors, and posterior distributions were estimated using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. Posterior medians were used as point estimates of effects, alongside 2.5% and 97.5% posterior percentiles representing a 95% compatibility interval (CI). The posterior probability of effect estimates being less than or greater than the null was also reported.

Results

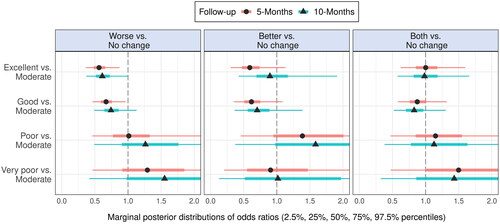

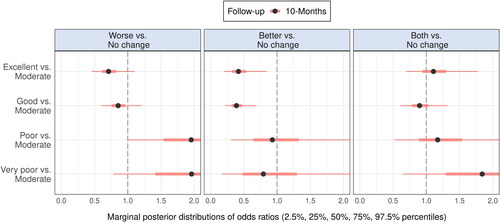

Marginal posterior distributions of coefficients in the multilevel multinomial regression models, estimating the effects of students’ trust in universities’ management of the pandemic at baseline on self-reported change in mental health at 5-month and 10-month follow-ups are presented in . For these analyses, data were available from 1,941 (69.4%) participants. The corresponding effect estimates of students’ trust in universities at a 5-month follow-up on self-reported change in mental health at a 10-month follow-up are presented in . For these analyses, data were available from 1351 (48.3%) participants. provides numerical details.

Figure 2. Marginal posterior distributions of coefficients in the multinomial regression models estimating effects of students’ trust in universities’ management of the pandemic at baseline on self-reported change in mental health at 5-month and 10-month follow-ups.

Figure 3. Marginal posterior distributions of coefficients in the multinomial regression models estimating effects of students’ trust in universities’ management of the pandemic at 5-months follow-up on self-reported change in mental health at 10-month follow-up.

Table 1. Assessments of trust in university management at baseline and at 5-month follow-up in relation to self-reported change in mental health at 5-month and 10-month follow-ups.

reveals a pattern indicating that reporting excellent or good trust at baseline, rather than moderate, resulted in an observed lower odds of reporting worse mental health rather than unchanged at the 5-month follow-up. This pattern was also evident at the 10-month follow-up, though with diminished strength for those reporting good trust at baseline. Among those who reported excellent or good trust at baseline, the odds for reporting better mental health were also lower than unchanged mental health at 5 months, however, this pattern did not hold at 10 months. Other effect estimates of baseline trust on change in mental health had wide posterior distributions indicating high uncertainty. In , effect estimates indicate that reporting excellent or good trust at 5 months resulted in lower odds of reporting better mental health rather than unchanged at the 10-month follow-up, with other estimates either having high uncertainty or being close to the null. For greater clarity, see .

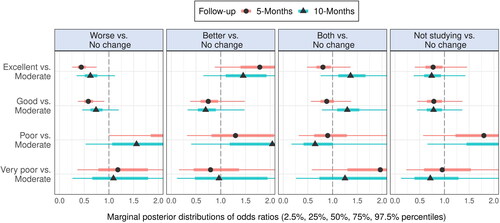

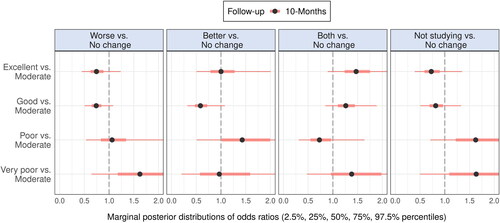

The corresponding results for academic self-efficacy are presented in and , and in . Data were available from 1930 (69.0%) of participants followed-up for estimates in and 1341 (49.6%) for estimates in . As is evident from , there was considerable uncertainty in the estimates of the effects of baseline trust on 5-month and 10-month self-reported change in academic self-efficacy, with the exception that excellent or good baseline trust at baseline resulted in an observed lower odds of reporting worse academic self-efficacy rather than no change. Similarly, in , estimates of the effects of 5-month trust on 10-month academic self-efficacy had high uncertainty or were close to the null, although the estimates of the odds of reporting worse rather than unchanged academic self-efficacy at 10 months were in the anticipated direction (i.e., lower) among those who reported having good or excellent trust in the university management at 5-months.

Figure 4. Marginal posterior distributions of coefficients in the multinomial regression models estimating effects of students’ trust in universities’ management of the pandemic at baseline on self-reported change in academic self-efficacy at 5-month and 10-month follow-ups.

Figure 5. Marginal posterior distributions of coefficients in the multinomial regression models estimating effects of students’ trust in universities’ management of the pandemic at 5-months follow-up on self-reported change in academic self-efficacy at 10-month follow-up.

Table 2. Assessments of trust in university management at baseline and at 5-month follow-up in relation to self-reported change in academic self-efficacy at 5-month and 10-month follow-ups.

Discussion

In summary, positive trust in university management seemed to protect against experiencing one’s mental health as worse, rather than unchanged, both 5 and 10 months after the baseline measure in the late spring of 2020. The same kind of protective effect was evident for academic self-efficacy. These results emphasize the importance of developing and maintaining positive bonds of trust between academia and students in order to support students’ mental health and academic self-efficacy.

Implications

Our findings extend previous pandemic-related research by adding a longitudinal perspective that complements cross-sectional studies that have reported associations between students’ trust and psychological distress (Khan et al., Citation2021; Defeyter et al., Citation2021), as well as between trust and academic frustration (Ballmann et al., Citation2022). While previous research has reported results related to the early phase of the pandemic, the current study shows longitudinal effects of trust in relation to mental health and academic self-efficacy. Our findings support considerable previous research on the beneficial effects of positive trust (see for example a review by Guinot & Chiva, Citation2019).

The pandemic has brought to the fore the capability to deal with uncertainty within higher education institutions, where academic developers have a key role in maintaining standards of excellence in teaching and learning, In a recent editorial note, Huijser and Sim (Citation2022) wrote that ‘this is not the first time, nor will it be the last, that academic developers have confronted profound uncertainty related to the purposes, practices, and contexts of our work’, and that ‘academic developers may be ideally placed to mediate in times of crisis since abrupt and continuous change can be seen as part of their 'natural environment’’. Concerning future pandemics and other crises and causes of uncertainty, the present study identifies trust as a key concern for university staff, where academic developers could be tasked with devising overall university strategies for maintaining or increasing trust.

In a recent publication, Lewicka (Citation2022) points out key issues to be considered by academic developers to facilitate trust between universities and students. There is an emphasis on the need to incorporate trust into the university’s vision and its organizational values. Moreover, the need to develop a clear policy, sufficiently train university management, and lecturers, and base long-term relationships with students on mutual understanding is underscored. Furthermore, it is emphasized that situations of intense change require timely communication and need to offer a sense of organizational stability and situational normality. Obviously, far from all of these key issues and their related actions were in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, it is important to keep in mind that any damaged trust can be restored by communicating a strong commitment to undertaking strategic and institutional repairs aiming to prevent future violations of trust (Poppo & Schepker, Citation2010).

Strengths and limitations

The main methodological strength of the present study lay in its longitudinal design as well as the use of a principled approach to defining causality. The use of a causal model allowed for the estimation of effects from observational data under the assumptions conveyed in the directed acyclic graph (), which by using do-calculus informed which variables needed to be adjusted to avoid confounding. This also means that the findings are limited by the causal graph’s representativeness of actual causal relationships; if they do not hold, then the estimates of effects are potentially still confounded and should be interpreted as associations. In the latter case, there is no protection against spurious associations induced by collider bias, apart from where time can guarantee the direction of causality. Thus, the estimates presented in the analyses should only be understood to represent effects if the causal model is appropriate.

Another noteworthy limitation related to the questions asking students to compare their mental health, and academic self-efficacy, to the four weeks immediately preceding the time point when the questionnaire was distributed. This meant that there was no baseline measure for levels of mental health and self-efficacy on a specified day, thus limiting our ability to assess whether baseline levels of mental health and perhaps academic self-efficacy as well, were variables that mediate the reports of trust in university management. Work showing that life satisfaction is associated with greater trust in others on both societal and individual levels (Helliwell & Wang, Citation2011) suggests that this question is worth investigating further. Also, the current study concerned a limited group of students choosing to participate themselves after responding to advertisements at a limited number of universities. These conditions mean that the participants may not be representative of the total group of students. Here, there is a need to add that the study findings may also have been affected by non-response vis-à-vis the two follow-ups.

A further limitation is related to the use of single items to assess the intended constructs which, in comparison to multiple-item measures, are considered to have lower content validity, sensitivity, and reliability. However, single-item measures can serve as a substitute for multiple-item measures since single items on global phenomena (e.g., ‘how would you rate your health?’) correlate overall with multiple-item total scores (Hoeppner et al., Citation2011). Additionally, single items are superior from the perspective of lowering the response burden, which may be important in online studies, particularly so in times when remote education requires students to spend much time online (Matthews et al., Citation2022). While prior research has shown that single-item measures of trust have good validity (Matthews et al., Citation2022), it should be noted that none of the single-item measures used in the present study were à priori-validated in relation to targeted constructs. This relates to our objective, as researchers, to react quickly when launching this study in order to systematically research any changes taking place during the initial - most challenging – period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Instead of defining each construct as a manifest state, the single-item measures were designed to capture the dynamic and changeable characteristics of the targeted constructs. Thus, the single-items addressed experiences underlying the constructs. For example, experiences related to university management were considered to recalibrate students’ judgments of trust in an ongoing process throughout the pandemic. By asking about students’ experiences, this question provided a valuable opportunity to understand the multifaceted characteristics of trust in the context of the universities’ ways of responding to a global crisis. Likewise, by targeting experiences contributing to the development and changes of efficacy beliefs and the development of mental health, the question provides insights into how these constructs developed during the pandemic.

Concerning criterion validity, each of the intended constructs follows the expected patterns hypothesized after reviewing cross-sectional research on trust (Calderone & Fosnacht, 2022; Khan et al., Citation2021; Defeyter et al., Citation2021; Ballmann et al., Citation2022; Andersson et al., Citation2022; Ogunmokun et al., Citation2022). However, since construct validity is lacking for all three single-item measures, the alternative is simply to consider what is addressed as ‘trust’ as ‘students’ experiences of universities’ way of managing the pandemic’, ‘mental health’ as ‘experienced changes in mental health’, and ‘academic self-efficacy’ as ‘experiences about how studies developed’. Obviously, content validity remains a limitation to single-item measures due to problems relating to fully covering the entire domain of interest. Ideally, future research should focus on validating the single-item measures used in the present study (cf. Matthews et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our longitudinal findings are in line with previous cross-sectional research on trust. With trust positively affecting student mental health and academic self-efficacy, the findings emphasize the importance of integrating sustainable trust-building measures at universities in times of uncertainty.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted on May 11, 2020, by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Ref. No. 2020-02109). All participants provided informed consent by ticking a box before entering the questionnaire.

Acknowledgements

We extend our appreciation to the participants in our study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset analyzed in the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Claes Andersson

Claes Andersson, PhD, is an Associate Professor in Psychiatry and senior lecturer of Criminology at Malmö University. He has experience doing research on mental health in university students, both nationally and internationally, and has experience in using both qualitative and quantitative methods.

Anne H. Berman

Anne H. Berman, PhD, is a Professor of Psychology at Uppsala University’s Department of Psychology. She has over 25 years of experience conducting RCTs, focusing on low threshold, easy access interventions, from ear acupuncture to minimal as well as low- and high-intensive digital interventions for substance use and mental health.

Petra Lindfors

Petra Lindfors, PhD, is a Professor of Psychology at the Department of Psychology, Stockholm University. Her research focuses on well-being and health, specifically in educational settings, youth, and early adulthood. She has been involved in both implementation and intervention research.

Marcus Bendtsen

Marcus Bendtsen, PhD, is a Senior Associate Professor in biostatistics and public health at Linköping University. He has extensive experience in designing, executing, analyzing, and leading RCTs on behavior interventions. Bendtsen is an expert in Bayesian statistics and leads a research lab focusing on health behaviors, health economy, and biostatistics.

References

- Andersson, C., Bendtsen, M., Molander, O., Granlund, L., Topooco, N., Engström, K., Lindfors, P., & Berman, A. H. (2021). Associations between compliance with covid-19 public health recommendations and perceived contagion in others: A self-report study in Swedish university students. BMC Research Notes, 14(1), 429. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-021-05848-6

- Andersson, C., Bendtsen, M., Molander, O., Lindner, P., Granlund, L., Topooco, N., Engström, K., Lindfors, P., & Berman, A. H. (2022). Academic self-efficacy: Associations with self-reported COVID-19 symptoms, mental health, and trust in universities’ management of the pandemic-induced university lockdown. Journal of American College Health, 1–6. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2145893

- Appleby, J. A., King, N., Saunders, K. E., Bast, A., Rivera, D., Byun, J., Cunningham, S., Khera, C., & Duffy, A. C. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the experience and mental health of university students studying in Canada and the UK: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 12(1), e050187. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050187

- Ballmann, J., Helmer, S. M., Berg-Beckhoff, G., Dalgaard Guldager, J., Jervelund, S. S., Busse, H., Pischke, C. R., Negash, S., Wendt, C., & Stock, C. (2022). Is lower trust in covid-19 regulations associated with academic frustration? A comparison between Danish and German university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031748

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.

- Bendtsen, M., Berman, A. H., Andersson, C., Perski, O., & Lindfors, P. (2022, May 27). Longitudinal data on Swedish university students’ mental health and study capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://osf.io/37dhm/

- Bendtsen, M. (2018). A gentle introduction to the comparison between null hypothesis testing and Bayesian analysis: Reanalysis of two randomized controlled trials. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(10), e10873. https://doi.org/10.2196/10873

- Berman, A. H., Bendtsen, M., Molander, O., Lindfors, P., Lindner, P., Granlund, L., Topooco, N., Engström, K., & Andersson, C. (2022). Compliance with recommendations limiting COVID-19 contagion among university students in Sweden: Associations with self-reported symptoms, mental health and academic self-efficacy. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948211027824

- Bormann, I., Niedlich, S., & Würbel, I. (2021). Trust in educational settings—What it is and why it matters. European perspectives. European Education, 53(3-4), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2022.2080564

- Buizza, C., Bazzoli, L., & Ghilardi, A. (2022). Changes in college students mental health and lifestyle during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Adolescent Research Review, 7(4), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2022.2080564

- Calderone, S. M., & Fosnacht, K. J. (2023). Student trust in higher education institutions: How the pandemic influenced undergraduate trust. American Behavioral Scientist, 67(13), 1611–1631. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642221118263

- Chen, Y.-C. (2017). The relationships between brand association, trust, commitment, and satisfaction of higher education institutions. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(7), 973–985. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-10-2016-0212

- Cook, K. S., & Schilke, O. (2010). The role of public, relational and organizational trust in economic affairs. Corporate Reputation Review, 13(2), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2010.14

- Defeyter, M. A., Stretesky, P. B., Long, M. A., Furey, S., Reynolds, C., Porteous, D., Dodd, A., Mann, E., Kemp, A., Fox, J., McAnallen, A., & Gonçalves, L. (2021). Mental well-being in UK higher education during COVID-19: Do students trust universities and the government? Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 646916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.646916

- Ghosh, A. K., Whipple, T. W., & Bryan, G. A. (2001). Student trust and its antecedents in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 72(3), 322–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2001.11777097

- Guinot, J., & Chiva, R. (2019). Vertical trust within organizations and performance: A systematic review. Human Resource Development Review, 18(2), 196–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484319842992

- Helliwell, J. F., & Wang, S. (2011). Trust and wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 1(1), 42–78. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v1i1.9

- Hoeppner, B. B., Kelly, J. F., Urbanoski, K. A., & Slaymaker, V. (2011). Comparative utility of a single-item versus multiple-item measure of self-efficacy in predicting relapse among young adults. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41(3), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2011.04.005

- Huijser, H., & Sim, K. N. (2022). Academic development in times of crisis. International Journal for Academic Development, 27(2), 111–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2022.2073654

- Khan, K., Li, Y., Liu, S., & Li, C. (2021). Psychological distress and trust in university management among international students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 679661. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.679661

- Lewicka, D. (2022). Building and rebuilding trust in higher education institutions (HEIs). Student’s perspective. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 35(6), 887–915. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-02-2022-0037

- Lewicki, R. J. (2006). Trust, trust development, and trust repair. In. M. Deutsch, P. T. Coleman, & E. C. Marcus (Eds.), The Handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice (pp. 92–119). Wiley Publishing.

- Lindblad, S., Lindqvist, A., Runesdotter, C., & Wärvik, G. B. (2021). In education we trust: On handling the COVID-19 pandemic in the Swedish welfare state. Zeitschrift Fur Erziehungswissenschaft: ZfE, 24(2), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-021-01001-y

- Matthews, R. A., Pineault, L., & Hong, Y. H. (2022). Normalizing the use of single-item measures: Validation of the single-item compendium for organizational psychology. Journal of Business and Psychology, 37(4), 639–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09813-3

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- Ogunmokun, O. A., Timur, S., & Ikhide, J. E. (2022). Reversing student attrition intentions using university COVID-19 response: A serial mediation and multi-group analysis. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2022.2052226

- Pearl, J. (2009). Causality (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803161

- Poppo, L., & Schepker, D. J. (2010). Repairing public trust in organizations. Corporate Reputation Review, 13(2), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2010.12

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. (2022). Number of cases of COVID-19 in Sweden [Antal fall av Covid-19 i Sverige]. https://fohm.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/68d4537bf2714e63b646c37f152f1392

- Swedish Higher Education Authority. (2022). The Swedish Higher Education Authority’s statistical database The University in figures [Universitetskanslersämbetets statistikdatabas Högskolan i siffror]. https://www.uka.se/statistik–analys/hogskolan-i-siffror.html

- Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., & Knight, C. (2022). Digital disruption in the time of COVID-19: Learning technologists’ accounts of institutional barriers to online learning, teaching and assessment in UK universities. International Journal for Academic Development, 27(2), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1990064

- Williams, B. (2002). Truth and truthfulness: An essay in genealogy. Princeton University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7ssz4

- World Health Organization, WHO. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338