Abstract

This mixed methods study examined students’ perceptions of EcoJustice and Social Justice curriculum in an undergraduate children’s literature course. Data included beginning-course and end-course Likert scale questions and open-ended responses, student reflective writings, and assignments. This study also examined survey responses from faculty teaching children’s literature. Results showed that students, primarily preservice teacher candidates, want EcoJustice topics in the curriculum and believe such teaching is more important than educators do. Students and teachers viewed Social Justice and EcoJustice pedagogy as separate and had much less understanding of EcoJustice topics and pedagogy compared to those of Social Justice; however, after experiencing an EcoJustice inclusive curriculum, the end-course results demonstrate that students had a much better understanding and a stronger belief in the importance of EcoJustice topics. Student participants reported a better understanding of how connected justice topics and pedagogy are and how they could incorporate such pedagogy into their own K-12 teaching using children’s literature. The author made her children’s literature courses more ecologically inclusive and justice-focused and provides brief recommendations for incorporating EcoJustice pedagogy in undergraduate children’s literature courses.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

Introduction

In Seven Blind Mice (Young, Citation1992), a picturebook based on an South Asian/Indian fable, seven blind mice argue over the appearance of something new in their world as they each explore different parts of ‘the Something.’ Finally, one mouse discovers ‘the Something’ is an elephant, and all the previously explored parts (an ear, tail, and leg, etc.) were taken in isolation. The story’s moral is that ‘wisdom comes from seeing the whole’ (last page). As an educator in the children’s literature domain for twenty-four years, I was compelled to study my observation that faculty were not incorporating EcoJustice topics and pedagogy in children’s literature courses the way they were with Social Justice topics and pedagogy. This study investigates that phenomenon.

Representations of cultural and social diversity, stories championing change, and the teaching of empathy, inclusion, equity, and justice are infused in children’s literature courses. This focus is also in children’s literature textbooks (Hintz & Tribunella, Citation2019; Kiefer et al., Citation2023; Lynch-Brown et al., Citation2011; Russel, Citation2019; Tunnel & Jacobs, Citation2008). Textbooks emphasize cultural and social diversity criteria when evaluating children’s literature, including social justice topics, and using equity lenses in examining and discussing children’s literature. According to my analysis and other research, children’s literature courses commonly focus on incorporating culturally responsive, anti-biased curriculum (Social Justice pedagogy); however, these inequality topics include little about ecological conditions (Graff et al., Citation2022; May et al., Citation2014; Reisberg, Citation2008).

Awareness of and inclusion of ecological topics and environmental justice across education occurs much less frequently on a national scale, and justice as applied to our relationship with the earth and how that affects people as well as the living and non-living eco-systems is not mentioned in the textbooks examined above. Many educators and the larger United States society still think of Social Justice and Environmental Justice in opposition to one another, or at least different from one another (Bowers, Citation2010; Damico, Citation2021; Gruenewald, Citation2006; Jackson, Citation2020). This bifurcation is a framing issue. Educators focusing on justice issues means that teacher-scholars must understand and teach the interconnectedness of both social and environmental justice; thus, this paper is an invitation to conceptualize and incorporate a praxis that is mutually inclusive of social and environmental justice topics in children’s literature courses—an EcoJustice ethic and curricula.

EcoJustice pedagogy, the primary framework for this study, is an educational approach emphasizing convergences between social and ecological justice (Martusewicz et al., Citation2021). EcoJustice pedagogy seeks to critically transform teaching to be more sustainable and just and to combat violence and oppression that minoritized groups and the natural world experience to equip learners with the knowledge and value of the interdependence of humans and the natural world. It cultivates learners’ agency to redress social-ecological subjugation (Cachelin & Nicolosi, Citation2022; Lupinacci & Happel-Parkins, Citation2016; Lupinacci et al., Citation2018a; Martusewicz et al., Citation2021).

Extensive calls have been made for higher education faculty to incorporate sustainability into their curriculum to motivate students to be ‘informed and thoughtful change agents’ (Coleman & Gould, Citation2019, p. 1). Sustainability in the public sector is often described as three pillars or interrelated circles of environment, economics, and society (Purvis et al., Citation2019). Looking at sustainability from a critical perspective and introducing this term in college-level courses, I prefer to conceptualize sustainability as the three Es: ecology, economics, and equity (Edwards, Citation2015; Fiorino, Citation2017). The United Nations also recommends that higher education include more sustainability concepts in the curriculum (Coleman & Gould, Citation2019), and others view the UN's Sustainable Development Goals as a way to transform higher education (Ogbuigwe, Citation2017). Similarly, the International Commission on the Futures of Education (Citation2021) states that higher education curricula should focus on ‘ecological, intercultural, and interdisciplinary learning’ (p. 77). Despite such calls, a survey of 1,068 two- and four-year higher educational institutions found that sustainability courses were offered in only 28% of the humanities disciplines and only 15% in education departments (McIntosh et al., Citation2008). Logically, K-12 educators could better teach sustainability, environmental education, and social and environmental justice topics if these topics were included preservice. Many studies have demonstrated that students are hungry for social and ecological examination and application, especially regarding climate change (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2015; Beck et al., Citation2013). Now more than ever, there is an urgency for higher education faculty to critically examine what and how they are teaching about relationships with each other and our world.

Community college context

Community colleges have a unique role in higher education since community colleges provide certificates and associate (two-year) degrees in workforce education and provide academic college transfer, enabling students to complete the first two years of a college/university education. Community colleges are essential in EcoJustice teaching, especially for students of color. Minoritized and first-generation college students who attend two-year institutions self-report a greater sense of belonging than those at four-year institutions, and college persistence is partially attributed to a sense of belonging (Johnson, Citation2020). Black and Latinx students of all income and performance levels are more likely to attend two-year institutions than their white counterparts (Ross, Citation2014). Given the student demographics at two-year institutions, it seems imperative that educators be aware and inclusive of social and environmental justice issues that affect students.

Community colleges also serve as a significant source of transfer to four-year institutions. Introductory or survey courses, like children’s literature, are most likely completed at the two-year level prior to student transfer, thus providing the opportunity to introduce students to sustainability topics, ecocriticism, climate literacy, and EcoJustice pedagogy, piquing their interest, and creating the desire for future courses incorporating such ideas and pedagogy. Additionally, such community college courses can seed ideas and provide the root system for preservice teachers to implement such topics in their current or future classrooms. For example, given the current teacher shortage in Arizona, K-12 educators can be hired without a bachelor’s degree. Some students enrolled in the children’s literature courses I teach are currently teaching in elementary schools without an associate or bachelor’s degree, especially in charter schools, government funded but independently operated K-12 schools. Community colleges are recognized as significantly more affordable and more flexible for students (The EdUp Experience Podcast, Citation2023). The typical transfer rate of community college students to four-year institutions is about 31%, and almost half of the graduates earning a bachelor’s degree in 2015–2016 had taken community college courses within the last ten years (Community College Research Center, Citation2022). These statistics are reminders that community colleges, undergraduate classes, and particularly children’s literature courses are important venues for reaching preservice teachers and, thus, addressing sustainability and EcoJustice topics.

Selected review of literature and scholarship

A number of studies (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2015; Hoppe, Citation2022; Leavenworth & Manni, Citation2021) have looked at various types of environmental education and sustainability education for preservice teachers and the value they placed on such education.

Overview of environmental education for preservice teachers

Environmental education aims to create environmentally literate students who have a foundation in understanding and solving ecological issues while kindling an appreciation of nature (Martusewicz et al., Citation2021; McBride et al., Citation2013). Though critical in raising environmental awareness, environmental education emphasizes scientific and individualistic approaches and sometimes focuses on ecological disaster narratives that can serve to distance and disengage students from environmental problem-solving (Martusewicz et al., Citation2021; Sobel, Citation2007, Citation2008). The distancing and disengagement can also occur with children’s environmental literature, given the typical scientific and individual hero focus (Gaard, Citation2014). EcoJustice pedagogy and ecopedagogy developed as a response to the concerns about environmental education and education for sustainable development not applying a transformative, critical lens, especially in higher education to development and sustainability topics in connection with social justice and the environment (Gaard, Citation2008, Citation2014; Misiaszek, Citation2019). Environmental education and education for sustainable development pedagogies focus on environmental sustainability and helping students understand such topics; therefore, for this paper, it is relevant to examine the studies relating to the importance of these pedagogies, especially in teacher education courses.

Lack of environmental education for preservice teachers

While several studies demonstrate the importance of environmental education, the literature demonstrates a lack of environmental education for preservice teachers. In an extensive literature review, Álvarez-García et al. (Citation2015) found nine studies that demonstrated higher education faculty were not engaging in cross-disciplinary environmental education for preservice teachers. Additionally, multiple gaps in learning exist about environmental education, mainly because courses with an environmental education and ecoliterary focus for preservice teachers are optional (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2015). Despite the lack of environmental education and education for sustainable development for preservice teachers, multiple studies have found that both, when in place, are valuable in developing awareness, confidence, and competence in discussing environmental topics. Preservice teachers reported positive associations with environmental education and believed it would improve their teaching and connection with their students (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2015). Education for sustainable development especially has been found to provide a ‘widened and more critical understanding of environmental issues’ (Leavenworth & Manni, Citation2021, p. 729).

Only a few studies have examined environmental topics from a more critical lens. For example, in one study, preservice teachers reported feeling more comfortable with racial justice topics than with environmental justice topics when using children’s picture books to integrate social justice material into their classrooms (Hoppe, Citation2022). All social justice topics (including racial and environmental) led to increased feelings of empathy and compassion as the preservice teachers moved through the discomfort of learning about justice topics (Hoppe, Citation2022).

EcoJustice education

Using EcoJustice pedagogy as a framework for a children’s literature course adds a liberatory, change-making feel to children’s literature. EcoJustice pedagogy is founded on Freire’s (Citation1970) critical pedagogy, where the use of praxis provides ‘reflection and action upon the world to transform it’ (p. 46). EcoJustice education incorporates Freirean ideas of ‘problem-posing’ (p. 39) questions to invoke a critical response to societal beliefs and norms that impact our relationships with our environments, with each other, and in relation to our environments (Bowers, Citation2010; Gaard, Citation2008; Misiaszek, Citation2019).

Ecojustice pedagogy recognizes that violence and oppression that minoritized groups and the natural world experience,

have deep cultural and socio-linguistic roots that are insidious. To the extent that teachers can begin to recognize the metaphoric structure of these discourses, handed down over many centuries and operating in our day-to-day exchanges, they will begin to challenge the appearance of universality, or naturalness. (Martusewicz et al., Citation2021, p. 103)

An EcoJustice approach refutes the dichotomy between social and ecological difficulties, arguing instead that they ‘are grounded in the same deeply embedded cultural assumptions and thus must be studied as such’ (Martusewicz et al., Citation2021, p. 9). Too much of education has been supportive of consumerism and the commodification of teaching and learning (Bowers, Citation2010). Basically, EcoJustice pedagogy is the union of Social Justice and Environmental Justice pedagogy. The students in this study often used the terms Ecojustice and Environmental Justice interchangeably, though the latter often focuses disproportionately on environmental injustices enacted on economically disadvantaged and minoritized peoples rather on a holistic framework recognizing the social and ecological injustices intertwining and affecting all life—people and planet (Martusewicz et al., Citation2021).

A core tenet of EcoJustice pedagogy is recognizing value-hierarchized thinking and challenging the logic of the domination model (Bowers, Citation2010; Lupinacci & Happel-Parkens, Citation2016; Martusewicz et al., Citation2021; Plumwood, Citation2002; Warren, Citation2000). This model recognizes that groups of people, through the use of specific metaphors and cultural assumptions, assert the idea that it is acceptable and natural for groups of people to dominate others. Thus, classism, racism, sexism, heterosexism, ecocide, and other injustices ‘must be seen in the context of the deeper cultural assumptions reproducing value hierarchies’ (Martusewicz et al., Citation2021, p. 141). Promoting EcoJustice education is essential if educators are to enable understanding, healing, and problem-solving of intertwining social and ecological justice crises.

EcoJustice pedagogy theorists have been critical of other critical pedagogies, claiming that they are too focused on neoliberal ideologies (Bowers, Citation2010; Lupinacci et al., Citation2018a; Misiaszek, Citation2019). In other words, these scholars-educators ask: How is our current Western development sustainable? They argue that higher education faculty is not doing enough to apply a critical economic lens to education. Bowers (Citation2010) is especially critical of Freire (Citation1970) and Giroux (Citation2004), indicating that critical pedagogy is too focused on Freire’s idea of individualism, which negates cultural traditions and intergenerational knowledge. The latter are especially important as we look toward TEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge) (Bowers, Citation2010; Kimmerer, Citation2013) and Emergent Strategies (Brown, Citation2017) for helping societies establish right relations with the earth and each other and develop lasting solutions to our current social and ecological crises. In particular, Bowers (Citation2010) reminds us of two problems with critical pedagogy. He is critical of the continual ideal of self-emancipation as unsustainable since it presupposes that all change is progress. Secondly, he argues that anthropocentrism is still the basis of critical pedagogy (Bowers, Citation2010; Lupinacci & Happel-Parkens, Citation2016; Lupinacci et al., Citation2018b). This human-centric (specifically male-dominated, Western world focus) does not help us address systemic problems impacting the nonhuman world, such as biodiversity loss or climate change.

Children’s literature

There is a growing body of scholarly inquiry emphasizing the incorporation of ecocriticism and eco-inclusive literature, especially in relation to using literature in a K-12 setting (Blenkinsop, Citation2022; Cachelin & Nicolosi, Citation2022; Misiaszek, Citation2019). Multiple teacher-scholars have recognized the value and effectiveness of using children’s literature with preservice teachers and K-12 educators to teach ethics of care, equitable human and land interaction, and counteract colonial representations of the environment (Grove & Still, Citation2014; Hoppe, Citation2022; Korteweg et al., Citation2010). Of note is not just the inclusion of ecocriticism and ecoliteracy pioneered by Gaard (Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2014; see also McBride et al., Citation2013), but to specifically focus on climate literacy (or climate change literacy) through literature for young people. While climate literacy is often considered synonymous with climate science literacy, environmental humanities scholars are beginning to consider climate literacy as a way of understanding environmental and ecological crises that emphasize earth-centric care, an examination of oppressive systems of people and planet, and stories that affect change. The focus is on a sustainable future using literature to promote action (Gaard, Citation2014; Oziewicz, Citation2023a; Citation2023b). In this paper, climate literacy is not climate science literacy, which focuses on the relationship between climate and humans and emphasizes facts and data. Since climate literacy is a narrative capacity, stories are the primary tools in this effort.

Focus of this study

This study focused on undergraduate children’s literature courses. Most preservice teacher education programs include a children’s literature course where time is spent reading and evaluating a wide array of literature, determining quality literature for the preservice teachers’ future classrooms, and discussing how literature can make a difference for children and young people in enjoying, learning, and understanding diverse topics. This study examined undergraduate, community college students, primarily preservice teachers’, perceptions of an EcoJustice curriculum in children’s literature courses. Data included a beginning- and end-course survey (quantitative and qualitative responses), student reflective writings, and student assignments. Additionally, this study examined quantitative and qualitative responses from faculty teaching children’s literature at two- and four-year colleges. Consideration was given as to what factors affect faculty’s perception of social and ecological justice and pedagogy and their ability to integrate such curriculum into children’s literature courses. The specific research questions for this study were:

What knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs relating to social diversity, environmental topics, and justice issues do students have in regard to the teaching of literature for children?

To what extent, if at all, do faculty foreground and examine such topics and stories in children’s literature courses, and how does this impact their teaching?

Methods

The methodological approach for this research study was mixed methods, two-part self-administered survey research (Scharrer & Ramasubramanian, Citation2021). This study includes the mixed methods data collected from students over two semesters (one academic year) during fall 2022 and spring 2023. Additionally, fall 2023 student assignments were collected and included. The second part of the research included survey responses collected from faculty teaching children’s courses during the spring of 2023. Student survey respondents were confidential to the researcher and de-identified while faculty survey respondents were anonymous; both studies obtained IRB (Institutional Review Board) approval. To ensure establish the generalizability of the findings, both survey instruments were designed to be trustworthy and reliable (Patten, Citation2017; Scharrer & Ramasubramanian, Citation2021). The questionnaires were created with input from three experienced social scientists and included multiple member checks to help ensure question clarity in addition to accuracy and resonance with participant experiences.

Student demographics

Participants were enrolled in an online children’s literature course in a semi-rural area of Arizona in the United States. For this study, both semesters of beginning-course survey data were combined as were the two sets of end-course data, resulting in 46 beginning-course responses and 40 end-course responses.Footnote1 End-course responses indicated 73% of students were pursuing an education degree with the following breakdown: pre-k (13%), K-5th grade (43%), 6–8 grade (2%), 9–12 grade (13%), and college (2%). Ninety-three percent of the students identified as female and 7% as male.Footnote2 Race/ethnicity of student participants fit the following identity categories: African American, Asian American, and Asian/Pacific Islander (5%); Caucasian/White (50%); Hispanic/Latinx (45%); Native American/Indigenous (10%). Participants were allowed to select more than one category; thus, these percentages sum to over 100. Responses containing four or fewer for each identity category were aggregated to protect the participant’s identity. If there were five or more responses for each identity category, the category remained its own group to be compared to other demographic groups.

Faculty demographics

Faculty survey respondents were anonymous. Thirty-one faculty responded to the teacher survey that was open for five weeks. Unlike the student demographics that varied in race and ethnicity, 25 participants indicated they were White (e.g. European, European American), and six participants identified as another race/ethnicity or indicated they did not wish to share. Twenty-eight faculty respondents identified as women; three responded with a different gender identity or declined to share.

Faculty teaching the children’s literature courses were grouped into three levels: relatively new to teaching (one semester-5 years), fairly experienced (6–15 years), or experienced (16–30 years). The first category contained 13 faculty surveyed, while the fairly experienced group included 11 faculty, and those grouped as experienced included seven faculty.

Faculty respondents were nearly split in teaching at two-year schools (16 participants) and at four-year schools (12 participants). Two respondents indicated they taught graduate children’s literature courses at four-year institutions, and one person indicated ‘other’ but declined to explain where they taught. Nine of the 31 respondents indicated that their children’s literature courses were housed in their school’s Education department, while 21 indicated the courses were located in the English/Literature department. One respondent noted that the courses were in a combined Education/English/Literature/Languages department.

Data collection: Students

Data included student surveys and assignments such as reflective writings and discussion board posts. The surveys included four student data sets with two semesters of sampling done the first week of the semester (beginning-course) and the last week (end-course). The survey included five demographic questions, four Likert scale questions that had multiple sub-questions, and six qualitative questions using the principles outlined in Babbie (Citation1990), Merriam and Tisdell (Citation2016), Scharrer and Ramasubramanian (Citation2021), and Patten (Citation2017). The four Likert scale questions included the following themes relating to children’s literature: student knowledge of social and ecological topics, their perceived connection between social and ecological justice, the perceived pedagogical importance relating to multicultural and environmental awareness and social and ecological justice topics, and the perceived ease of incorporating social and ecological justice topics. See Appendix A for the specific qualitative questions asked.

Data collection: Faculty survey

The faculty survey used cross-sectional, non-probability, purposeful, and snowball sampling (Babbie, Citation1990; Blair et al., Citation2013; Creswell & Báez, Citation2021; Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018; Patten, Citation2017; Scharrer & Ramasubramanian, Citation2021) to seek responses from college faculty in order to determine if and to what extent they incorporate Social Justice and EcoJustice pedagogy into their courses. Recruitment consisted of three emails sent over five weeks to Arizona institutions of higher education faculty offering a children’s literature course. Recruitment also consisted of three emails sent over the same five-week period to a listserv of English faculty teaching at two-year colleges ([email protected]). Recipients were asked to forward the survey to faculty teaching children’s literature courses in any department or any higher educational institution. While survey dissemination was focused on community college faculty because of the availability of the listserv, faculty teaches at multiple institutions and at both two- and four-year schools. There was no attempt to limit responses from faculty as cross-pollination between two- and four-year schools could prove beneficial. As previously indicated, the response rate from faculty at four-year institutions was nearly equal to that of faculty teaching at two-year institutions.

The survey questions were designed to provide a snapshot of the faculty’s inclusion of eco-social justice topics in their children’s literature courses (Kent State University Libraries, Citation2021; Patten, Citation2017; Scharrer & Ramasubramanian, Citation2021). The survey consisted of 20 questions (nine quantitative/Likert scale questions, two open-ended questions, five demographic questions, and four optional and follow-up questions). See Appendix B for the nine Likert-scale questions. Two open-ended questions asked respondents for further feedback or ideas regarding their perception, integration, and application of Social Justice and EcoJustice pedagogy in children’s literature courses.

Findings

In many instances students and faculty reported similar understandings and needs, though students expressed more interest in and desire for EcoJustice education in both their quantitative and qualitative responses than faculty did. The following themes emerged from this study. in the Conclusion provides a visual of the themes.

Students viewed EcoJustice aspects as more important than faculty.

Students believed EcoJustice is important because they are concerned about planetary health for themselves and their future students.

Students and faculty considered Social Justice pedagogy more important than EcoJustice pedagogy, though students viewed EcoJustice pedagogy as equally important to Social Justice pedagogy after completing the course.

Students lacked knowledge of EcoJustice topics and pedagogy: Students felt less knowledgeable about environmental topics and EcoJustice pedagogy compared to cultural/social diversity and Social Justice topics.

Student understanding of EcoJustice pedagogy significantly increased over the semester: Views of importance, belief in the connection between social and ecojustice topics, and the ease of incorporating EcoJustice pedagogy into their teaching improved significantly, becoming nearly equal to responses regarding Social Justice pedagogy.

Faculty significantly emphasized Social Justice over EcoJustice pedagogy but want to include more of the latter.

Faculty institution type, department, and experience mattered little: There was little difference in the inclusion of Social Justice and EcoJustice pedagogy between faculty teaching at two versus four-year schools, those in Literature versus Education departments, or those with less teaching experience versus those with more.

Students viewed EcoJustice pedagogy as more important than faculty did

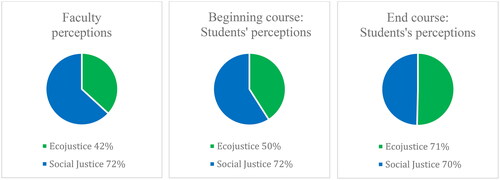

Perhaps the most revealing finding when comparing the student and faculty data was that students view the importance of EcoJustice pedagogy being taught in children’s literature courses as more essential than faculty do. Only 42% of teachers ranked the inclusion of EcoJustice pedagogy within a children’s literature course as very important compared with 50% of students who rated it as very important in the beginning-course questionnaire. At the end of the course, students ranked the importance of EcoJustice pedagogy at 71%. This number correlates with the qualitative responses.

Students concerned about the planet and future

In their survey responses, students typically indicated why they believed EcoJustice was important and why it was so for a children’s literature course. They mostly cited concerns about planetary health and how that would impact them and future generations. This student participant’s response was indicative of EcoJustice’s importance:

It is important because it’s a basic human right. It allows everyone to have some level of agency over the decisions that impact their lives. Without EcoJustice many people are made to be victims of the plans and ambitions of others.

By incorporating EcoJustice into children’s literature, we can raise awareness about ecological topics such as climate change, pollution, deforestation, and endangered species. This early exposure helps children understand the impact of human actions on the environment and encourages them to become active stewards of the planet.

Students and faculty believed social justice pedagogy is more important than EcoJustice pedagogy

Faculty and, initially, students felt that Social Justice pedagogy was more important than EcoJustice pedagogy. Both teachers and students view Social Justice and EcoJustice (Environmental Justice) as separate entities, reinforcing the lack of connection to one another and the artificial binary. Results show a significant gulf between faculty perceptions of the importance of Social Justice pedagogy and EcoJustice pedagogy. Seventy-one percent of faculty strongly agreed that Social Justice pedagogy is important in a children’s literature course compared to only 42% of faculty who strongly agreed that EcoJustice pedagogy is important in a children’s literature course. At the beginning of the course, students also rated social justice topics (72%) as more important than EcoJustice topics (50%) for a children’s literature course; however, the difference between the two was less than that of the faculty population. By the end of the semester, students saw how entangled the two pedagogies are. Students’ end-course quantitative responses demonstrated little difference between the importance of Social Justice pedagogy and EcoJustice pedagogy (70% and 71%, respectively). See for an illustration of the perceptions of faculty and students on the importance of Social and EcoJustice pedagogy.

Students lacked knowledge of EcoJustice topics and pedagogy

According to the responses, the initial lack of importance placed on EcoJustice pedagogy appears primarily to stem from students feeling they lack knowledge about environmental topics. For the beginning-course responses, only 35% of students indicated they felt knowledgeable or very knowledgeable about environmental topics, while only 20% indicated they felt knowledgeable or very knowledgeable about ecological justice. The student end-course responses rated these categories as 67% and 61%, respectively. A 40% increase in EcoJustice knowledge is significant; given the small amounts of EcoJustice topics and pedagogy I included in my children’s literature course, it is clear that small changes in curriculum yield large results. Similarly, students’ rating of being knowledgeable or very knowledgeable about Social Justice topics increased, too, jumping from 61% at the beginning of the course to 73% at the end of the course.

Student understanding about EcoJustice pedagogy significantly increased

As indicated above, student knowledge about environmental topics and EcoJustice pedagogy increased over the semester. Student views of the importance and the ease of incorporating EcoJustice pedagogy into their teaching also increased, becoming nearly equal to responses regarding Social Justice pedagogy. The belief in the connection between Social and EcoJustice topics also jumped from beginning-course to end-course.

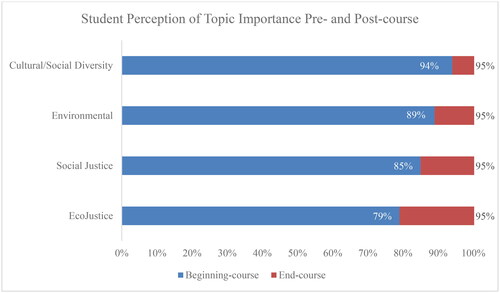

Student participants were asked to consider the importance of K-12 educators in teaching the following topics: social/cultural diversity, social justice, environmental topics, and ecological justice topics. Most students rated these topics as important or very important instead of somewhat important or neutral. At the end of the course, the percentage of students rating these four areas increased so that all categories were considered equal in their importance, as shown in , below. The questions asked included:

How important is it that K-12 educators teach topics of social/cultural diversity?

How important is it that K-12 educators teach environmental topics?

How important is it that topics of social/cultural justice are taught in relation to literature for children?

How important is it that topics of ecological justice are taught in relation to literature for children?

Regarding , the data displayed is an aggregation of student responses (in percentage) that were either ‘important’ or ‘very important.’ The two data points reflect beginning-course and end-course perceptions of importance regarding the four themes. While the view of Social Justice’s importance increased by 10%, most notably, students’ perceptions about EcoJustice’s importance jumped the most at 16%.

In addition to the importance of the above topics being taught, students felt the ease of teaching Social and EcoJustice topics through children’s literature was less difficult after completing the course. Beginning-course data included one student who stated, ‘I need help better understanding how to present ecological justice issues.’ Such comments were typical of students; they wanted information about how to approach and apply these ideas to their own or future classrooms or for their children. Students had similar questions and concerns about incorporating Social Justice pedagogy. Beginning-course data indicates that 14% of students considered the inclusion of Social Justice topics in their future teaching as somewhat easy; this percentage increased to 26% in the end-course data. Similarly, beginning-course responses showed that only 7% of students believed including EcoJustice topics in their future teaching would be somewhat easy, whereas 23% believed it would be so by the end of the course. Again, this percentage nearly equals the perceived ease of including Social Justice topics and issues within their teaching by the end of the course. It is important to note that students in my children’s literature course discuss teaching techniques and emphasize using literature in the classroom. However, this is a literature course, not a methods course; thus, even infusing a few assignments or beginning information about EcoJustice pedagogy made a difference.

One example of student learning occurring when exposed to a wider justice lens and ecocriticism is a student who, earlier in the class, noted that she had to read materials multiple times and sometimes struggled with understanding. After reading Bradfield’s (Citation2020) article on applying an ecocritical lens to children’s literature, the student wrote:

Prior to reading the article, I had only considered teaching about the social and natural environment, not ‘in’ or ‘through’ it. I found it especially helpful that examples were provided that demonstrated how to incorporate each. What stood out the most was the section about teaching through the social and natural environment. I made a connection with a previous course on multicultural values in education, which highlighted the importance of teaching students to be open-minded global citizens who value perspectives outside of their own experiences. Although the focus was on cultural differences, I think the idea also fits with reading through an ecocritical lens. It is difficult to care about something you do not know about, so helping students make connections between themselves and their environment can promote environmental awareness, encourage sustainable values in students, and foster a sense of ecological responsibility. After reading Two Degrees by Alan Gratz last year, my daughter encouraged us to make efforts to reduce our own carbon footprints. I think this is the goal of reading through an ecocritical lens, it prompts readers to ask questions and take action.

Faculty significantly emphasized social justice over EcoJustice but want more of latter

As noted earlier, only 42% of the faculty teaching children’s literature indicated that EcoJustice pedagogy was very important. This rating differed from their view about Social Justice pedagogy, which 71% of the faculty rated as very important. While faculty indicated that time constraints limited their inclusion of Social Justice pedagogy, lack of knowledge was the most significant deterrent to including EcoJustice pedagogy, which may have affected faculty’s views of its importance since it is difficult to value something if one feels inept or inexperienced. One faculty participant wrote, ‘I had never considered EcoJustice in relation to Children’s Lit.’ Faculty noted ‘the lack of PD’ [professional development] and indicated they wanted and needed more PD to incorporate environmental topics and EcoJustice pedagogy in their courses.

Three qualitative responses indicated that faculty are incorporating climate justice curriculum into the course, and two faculty noted they were incorporating EcoJustice elements in small ways. Of the 31 quantitative responses, 20 Likert-type responses indicated that faculty integrated and incorporated EcoJustice pedagogy into their children’s literature courses via novels/books chosen for the class to read. Faculty were encouraged to select all the ways they included EcoJustice pedagogy in their course. The top four ways, in rank order, include novels/books, in-class discussions, articles relating to theory/pedagogy, and discussion boards. These top four ways mirrored how faculty integrate or incorporate Social Justice pedagogy, except that at the top of Social Justice pedagogy list was the inclusion of writing projects/papers. indicates the ways faculty integrate and incorporated both Social Justice pedagogy and EcoJustice pedagogy into their children’s literature courses.

Table 1. Ways faculty integrate SJ and EJ into their children’s literature courses.

Of significant note is that the ways faculty include EcoJustice pedagogy when it is incorporated in classes are like the ways they do so with Social Justice pedagogy; perhaps this then makes it easier for faculty newer to incorporating EcoJustice pedagogy to strategically implement it similarly to the way they are already teaching other justice topics. As demonstrates, this small study also indicates that more writing projects and papers are needed if EcoJustice topics are to be compared to how faculty incorporate other justice topics in children’s literature courses. Videos and applied/hands-on assignments focusing on the EcoJustice pedagogical arena were also lacking compared to usage of similar Social Justice materials. Whether the lack of these methods and materials when integrating EcoJustice pedagogy is due to lack of available resources or the lack of familiarity with such resources is something to consider.

Faculty institution type, department, and experience mattered little

Despite potential reasons for either two-year or four-year institutions to provide more emphasis on EcoJustice topics, no difference was discernible in this study between faculty teaching at two- or four-year schools. Similarly, there was no difference in faculty incorporating more environmental topics and EcoJustice pedagogy based on whether their school housed children’s literature courses in English/Literature or Education departments. A larger-scale study might find differences, or perhaps this is simply indicative of the lack of knowledge and experience that faculty across disciplines report regarding sustainability and ecological education (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2015). The faculty’s teaching experience also minimally impacted their inclusion of EcoJustice pedagogy. Based on qualitative responses, there was a slight difference in those relatively new to teaching (one semester – five years), indicating excitement and interest in EcoJustice pedagogy. For example, one faculty member reported, ‘This [EcoJustice pedagogy] is a new area related to literacy for me! I will need to learn more and see how I can incorporate EcoJustice into my current Children’s Literature course content and materials.’ Fairly experienced (6–15 years) faculty were slightly more likely than relatively new and experienced (16–30 years) faculty to report in their qualitative responses that they were incorporating some aspect of climate literacy or EcoJustice pedagogy.

Discussion and recommendations: toward the whole elephant

The results from this study support the larger cultural narrative of the separation between Social and Environmental Justice and the need for a more effective understanding and incorporation of EcoJustice pedagogy. Though the separation is the perception of faculty, it may contribute to the feelings of the faculty teaching children’s literature that they are not knowledgeable enough about ecological issues to teach about them. These results are in keeping with the perceptions that environmental topics are often the purview of the sciences (Coleman & Gould, Citation2019; McIntosh et al., Citation2008;) and findings that science faculty in higher education tend to feel more comfortable, knowledgeable, and responsible for teaching about climate change and thus incorporate it more in their teaching than Arts/Humanities, Business, Social & Behavioral, and Education faculty (Beck et al., Citation2013). However, four studies found that when environmental education promoted environmental knowledge and values, it was most effective when the information was taught cross-disciplinarily (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2015). Here, then, is where literature, which is multi-disciplinary, comes in. Literature provides education and knowledge about topics and can enable readers to reject and embrace various environmental and ecojustice ethics and values seeded through plot lines, character development, and creative, cooperative problem-solving focused on social and ecojustice aspects and critical literacies.

Gaps in knowledge are likely to occur in teaching children’s literature if we do not consider Social and Environmental Justice pedagogy, climate change literacy, ecoliteracy, and especially EcoJustice pedagogy. Projects like the Climate Lit database (https://www.climatelit.org/) help teachers select stories teaching children and youth to connect or reconnect with the environment (Leavenworth & Manni, Citation2021; Oziewicz, Citation2022b). Oziewicz’s (Citation2022a) focus on Planetarianism is especially relevant for children’s literature educators as he explains that Planetarianism prioritizes an earth-first agenda while fore-fronting applied hope through children and young adult literature. The stories society and authors offer, educators teach, preservice teachers discover, and young people consume encourage creative imaginative engagement, providing active, action-oriented hope for our ecological crises and ecological justice issues (Oziewicz, Citation2022b; Citation2022a). Additional exploration of various literary frameworks for K-12 educators, such as Wild Pedagogies (Blenkinshop et al., Citation2022) and CLICK (Climate Literacy Capabilities and Knowledges) (Oziewicz, Citation2023a), may aid faculty in creating climate literacy and providing an EcoJustice perspective that deconstructs unproductive narratives (such as dystopian visions of our future) (Oziewicz, Citation2022b) and provides counter-narratives to our cultural ecocide (Damico et al., Citation2020; Griffin, Citation2016; Oziewicz, Citation2022b)—promoting and engaging in transformative equity and eco practices.

Changes in student learning

Over the three semesters of integrating EcoJustice pedagogy in my children’s literature course, students responded each semester with increased knowledge, a sense of importance, and an understanding of EcoJustice topics and curricula. After one semester of integrating EcoJustice pedagogy into my children's literature course, to: After students experienced one semester of EcoJustice pedagogy integrated into my children's literature course, it is striking that students at the end of the course reported Social Justice and EcoJustice topics as equally important and the ease of teaching both as nearly the same. Such results suggest that even small amounts of EcoJustice pedagogy changed the classroom dynamic, helping students create connections to the environment and better understand social, historical, and economic inequities relating to our interactions with each other and the planet.

Similarly, students’ reported knowledge of environmental topics and EcoJustice topics increased from the beginning to the end of the course. As noted earlier, a 40% increase in EcoJustice knowledge is significant, demonstrating that even a few articles and texts helped students’ knowledge of issues relating to climate change, earth-centric care, and various portrayals (both in words and images) of the environment. Students reported feeling knowledgeable or very knowledgeable about Social Justice topics at 73 percent, whereas the same reported feelings for EcoJustice were 61 percent. While the EcoJustice aspects were nearly equal or equal to Social Justice categories in importance, ease of teaching, and how connected the justice aspects are, the reported difference in knowledge is the biggest difference between Social Justice and EcoJustice pedagogy. These results suggest that students likely need more environmental topics infused and EcoJustice pedagogy integrated throughout children’s literature courses. These results mirror other research indicating that preservice teachers felt less knowledgeable about environmental and ecological topics than other topics, including racial justice issues (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2015; Hoppe, Citation2022). Such similarities likely reflect the lack of sustainability topics and focus throughout much of higher education.

Professional development

From the other research noted and this study’s findings, students want and need pedagogy relating to EcoJustice issues and eco literature. While some faculty provides this in their children’s literature courses, nearly all faculty surveyed indicated that their lack of knowledge in this area was a significant gap for them. Because of this gap, this is likely why faculty has such a division in their sense of importance between the two. Most also indicated that professional development (PD) opportunities are much needed. Institutions of higher education need to provide funding for such PD and offer in-house opportunities for faculty to discuss topics related to sustainability and ecojustice across disciplines.

While it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide extensive praxis-orientated suggestions, faculty can still make incremental EcoJustice pedagogical changes to their courses. For example, faculty can ask critical questions incorporating an ecojustice ethic and social justice topics. EcoJustice pedagogy can be integrated into children’s literature courses through assignments, reading materials, and theory incorporating ecoliteracy questions, a discussion of the logic of the domination model, and stories that include a critical analysis of humans’ relationships with each other and the earth. While teaching the EcoJustice inclusive courses, my self-reflexive notes and students’ qualitative responses indicate more authentic learning and deeper engagement than previous semesters that did not integrate an ecojustice focus. Problematizing the lack of environmental topics and ecological justice aspects empowered me to revise my children’s literature course to promote effective changes.

Limitations

The small faculty sample size creates limitations. Further study is needed to obtain a more extensive cross-section of faculty. However, the snowball recruiting provided a unique offering of two-year and four-year faculty teaching undergraduate children’s literature courses. The online survey embedded in my children’s literature course may have deterred students from responding or responding honestly, thus skewing the results. I took all precautions, however, to separate the optional study participation from the required coursework and to communicate to the students the purpose of the study and the anonymity of their responses. Finally, some wording in the student and faculty surveys may not address distinctions or nuances in interpretations. For example, the students often used the words environmental justice and EcoJustice interchangeably throughout the course and the survey, though both terms were defined in the course and on the survey. Likewise, the phrase EcoJustice pedagogy was clearly defined in the faculty survey; however, this term may be less familiar to faculty. Thus, faculty may be engaging in EcoJustice pedagogy without fully realizing they are doing so. Since the scope of this study did not include EcoJustice pedagogical professional development, faculty understanding, knowledge, and value of implementing EcoJustice pedagogy would likely have changed if faculty had been surveyed after receiving such professional development.

Conclusion

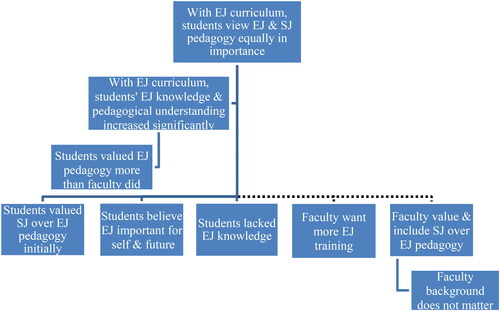

The multiple findings or themes from this study are visually summarized in .

The dotted line from the faculty findings represents the need for faculty to provide more EcoJustice pedagogy. When such pedagogy is a part of the curriculum, portrayed by the solid black line, student knowledge about environmental topics and EcoJustice pedagogy increased over the semester. Student understanding of the following also increased: views of the importance of an EcoJustice education, belief in the connection between Social Justice pedagogy and EcoJustice pedagogy, and the ease of teaching environmental topics and EcoJustice pedagogy. Such a curriculum led to students’ beliefs that Social Justice and EcoJustice pedagogy are equally important.

Ultimately, EcoJustice pedagogy can provide the methods and content for children’s literature educators to help learn, unlearn, and relearn healthier ways of interacting with our world. Faculty can specifically assist students and preservice teachers in doing this through literature for children. Returning to Ed Young’s (Citation1992) picturebook, educators need to understand the whole elephant and integrate social and ecological justice issues to address gaps, blend, and blur the bifurcation of Social Justice versus Environmental Justice teaching—embracing an EcoJustice pedagogy.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karen M. Hindhede

Karen M. Hindhede is an English Professor and Interim Academic Dean at Central Arizona College. She is finishing her Ph.D. in Sustainability Education at Prescott College. Professor Hindhede has taught children’s literature classes in person and online for twenty-four years. Professor Hindhede noticed a lack of environmental justice picturebooks, despite the numbers of picturebooks portraying social justice. This led Professor Hindhede to investigate picturebook portrayals and publish We All Need to Be Water Protectors: Diversity, the Environment, and Social and Environmental Justice Picturebook Themes and Portrayals in Environmental Education Research. Given the intertwining aspects of environmental justice and social justice, Professor Hindhede began researching EcoJustice pedagogy for her dissertation and how it might be applicable in children’s literature courses. This research and the corresponding changes she instituted in her courses led to this article. In conjunction with this piece, Professor Hindhede wrote a practitioner-focused article building on the research discovered in this study. That article, Implementing Ecojustice Praxis in Children’s Literature Courses, is under review.

Notes

1 I have chosen to only share the end-course student demographic data because there was little difference in the beginning-course and end-course responses. For example, 74% of students beginning-course indicated they planned to pursue teaching as opposed to 73% of students end-course. Any end-course number changes reflect students withdrawing from the course or identifying differently from their beginning-course responses such as in which grade level they may wish to specialize.

2 Student participants were able to select from multiple gender identities; however, they only chose female and male.

References

- Álvarez-García, O., Sureda-Negre, J., & Comas-Forgas, R. (2015). Environmental education in preservice teacher training: A literature review of existing evidence. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 17(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2015-0006

- Babbie, E. (1990). Survey research methods (2nd ed.). Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Beck, A., Sinatra, G. M., & Lombardi, D. (2013). Leveraging higher-education instructors in the climate literacy effort: Factors related to university faculty’s propensity to teach climate change. The International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses, 4(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.18848/1835-7156/CGP/v04i04/37181

- Blair, J., Czaja, R., & Blair, E. (2013). Designing surveys: A guided to decisions, and procedures (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Blenkinsop, S., Morse, M., & Jickling, B. (2022). Wild pedagogies: Opportunities and challenges for practice. In M. Paulsen, J. Jagodzinski & S. Hawke, (Eds.), Pedagogy in the Anthropocene (pp. 33–51). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bowers, C. A. (2010). Toward an eco-justice pedagogy. Environmental Education Research, 8(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620120109628

- Bradfield, K. (2020). Reading with an ecocritical lens: Deeper and more critical thinking with children’s literature. Practical Literacy: The Early and Primary Years, 25(2), 15–16. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/informit.172131407109704

- Brown, A. (2017). Emergent strategy. AK Press.

- Cachelin, A., & Nicolosi, E. (2022). Investigating critical community engaged pedagogies for transformative environmental justice education. Environmental Education Research, 28(4), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2034751

- Coleman, K., & Gould, R. (2019). Exploring just sustainability across the disciplines at one university. The Journal of Environmental Education, 50(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2019.1582471

- Community College Research Center. (2022). Community College FAQs. Teacher College Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/community-college-faqs.html

- Creswell, J. W., & Báez, J. C. (2021). 30 Essential skills for the qualitative researcher (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

- Damico, J. S. (2021). Then and now: Time for ecojustice literacies. Language Arts, 99(2), 126–130. DOI https://doi.org/10.58680/la202131519

- Damico, J. S., Baildon, M., & Panos, A. (2020). Climate justice literacy: Stories-we-live-by, ecolinguistics, and classroom practice. [Peer reviewed version]. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 63(6), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1051

- Edwards, A. R. (2015). The heart of sustainability: Restoring ecological balance from the inside out. New Society.

- Fiorino, D. J. (2017). Green economy: Reframing ecology, economics, and equity. In J. Meadowcroft & D. J. Fiorino (Eds.), Conceptual Innovation in Environmental Policy (pp. 281–306). MIT Press Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262036580.003.0012

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Publishing Group.

- Gaard, G. (2008). Toward an ecopedagogy of children’s environmental literature. Green Theory & Praxis: The Journal of Ecopedagogy, 4(2), 15. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Greta-Gaard/publication/265048062_Toward_an_Ecopedagogy_of_Children%27s_Environmental_Literature/links/559c2d1c08ae898ed651c31b/Toward-an-Ecopedagogy-of-Childrens-Environmental-Literature.pdf

- Gaard, G. (2009). Children’s environmental literature: From ecocriticism to ecopedagogy. Neohelicon, 36(2), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11059-009-0003-7

- Gaard, G. (2014). What’s the story? Competing narratives of climate change and climate justice. Forum for World Literature Studies, 6(2), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660466.2017.1364096

- Giroux, H. (2004). Cultural studies, public pedagogy, and the responsibility of intellectuals. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 1(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1479142042000180926

- Graff, J., Liang, L. A., Martinez, M. G., McClure, A., Day, D., Sableski, M. K., & Arnold, J. M. (2022). Contemporary children’s literature in education courses: Diverse, complex, and critical. Literacy Practice and Research, 47(3) https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/lpr/vol47/iss3/3

- Griffin, S. (2016). Sustainability and the soul. In Canty, J.M. (Ed.), Ecological and social healing: Multicultural women’s voices (1st ed., pp. 12–21). Taylor & Francis. https://www.routledge.com/Ecological-and-Social-Healing-Multicultural-Womens-Voices/Canty/p/book/9781138193666

- Grove, M. K. & Still, K. L. (2014). ‘They’ll grow up and be adults wanting to take care of our environment’: The story of Jan and critical literacy. Reading Improvement, 51(2), 254–268. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/%22They%27ll+grow+up+and+be+adults+wanting+to+take+care+of+our…-a0376070829

- Gruenewald, D. A. (2006). Place-based education: Grounding culturally responsive teaching in geographic diversity. Democracy & Education, 16(2), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315769844

- Hintz, C., & Tribunella, E. (2019). Reading children’s literature (2nd ed.). Broadview Press.

- Hoppe, K. (2022). Engaging pre-service teachers in interactive social justice-themed read-alouds. Educational Considerations, 48(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4148/0146-9282.2322

- International Commission on the Futures of Education. (2021). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract of education. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379381

- Jackson, A. E. (2020). I am a Black climate expert. Racism derails our efforts to save the planet. The Washington Post. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/race-and-climate-change/

- Johnson, E. (2020). Student’s sense of belonging varies by identity, institution. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/01/02/minority-students-sense-place-higher-two-year-four-year-institutions#:∼:text=A%20new%20study%20shows%20that%20minority%20and%20first-generation,two-year%20colleges%20than%20their%20counterparts%20at%20four-year%20institutions.

- Kent State University Libraries. (2021). SPSS tutorials: Working with ‘check all that apply’ survey data (multiple response sets). https://libguides.library.kent.edu/SPSS/Multiple-Response-Sets

- Kiefer, B., Tyson, C., Barger, B., Patrick, L., & Reilly-Sanders, E. (2023). Charlotte Huck’s children’s literature. McGraw Hill.

- Korteweg, L., Gonzalez, I., & Guillet, J. (2010). The stories are the people and the land: Three educators respond to environmental teachings in Indigenous children’s literature. Environmental Education Research, 16(3–4), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903549755

- Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teaching of plants. Milkweed.

- Leavenworth, M. L., & Manni, A. (2021). Climate fiction and young learners’ thoughts: A dialogue between literature and education. Environmental Education Research, 27(5), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1856345

- Lupinacci, J., & Happel-Parkins, A. (2016). (Un)Learning anthropocentrism: An ecojustice framework for teaching to resist human-supremacy in schools. In S. Rice & A.G. Rud (Eds.), Animal interactions: Blurring the species line (pp. 12–30). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lupinacci, J., Happel-Parkins, A., & Lupinacci, M. W. (2018a). Ecocritical contestations with neoliberalism: Teaching to (un)learn ‘normalcy. Policy Futures in Education, 16(6), 652–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318760465

- Lupinacci, J., Happel-Parkins, A., & Turner, R. (2018b). Concluding thoughts: A conversation with C. A. Bowers. Issues in Teacher Education, 27(2), 118. Corpus ID: 150950444

- Lynch-Brown, C., Tomlinson, C., & Short, K. (2011). Essentials of children’s literature. Pearson.

- Martusewicz, R. A., Edmundson, J., & Lupinacci, J. (2021). EcoJustice education: Toward diverse, democratic, and sustainable communities (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- May, L. A., Bingham, G. E., & Pendergast, M. L. (2014). Culturally and linguistically relevant read alouds. Multicultural Perspectives, 16(4), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960.2014.952299

- McBride, B. B., Brewer, C. A., Berkowitz, A. R., & Borrie, W. T. (2013). Environmental literacy, ecological literacy, ecoliteracy: What do we mean and how did we get here? Ecosphere, 4(5), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00075.1

- McIntosh, M., Gaalswyk, K., Keniry, L. J., & Eagan, D. J. (2008). Campus environment 2008: A national report card on sustainability in higher education. https://www.nwf.org/EcoLeaders/Campus-Ecology-Resource-Center/Reports/State-of-the-Campus-Environment

- Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Misiaszek, G. W. (2019). Ecopedagogy: teaching critical literacies of ‘development’, ‘sustainability’, and ‘sustainable development. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(5), 615–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1586668

- Ogbuigwe, A. (2017). Advancing sustainability in higher education through the UN’s Sustainability Development Goals. MIT Office of Sustainability. https://sustainability.mit.edu/article/advancing-sustainability-higher-education-through-uns-sustainable-development-goals#:∼:text=Goal%204%20of%20the%20SDGs%20is%20specific%20to,That%27s%20enough%20reason%20for%20me%20to%20jump%20onboard%21

- Oziewicz, M. (2022a). Planetarianism now: On anticipatory imagination, young people literature, and hope for the planet. In M. Paulsen, (Ed.), J. Jagodzinski & S. Hawke, (Eds.), Pedagogy in the Anthropocene (pp. 33–51). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Oziewicz, M. (2022b). Why children’s stories are a powerful tool to fight climate change. Yes! https://www.yesmagazine.org/opinion/2022/01/14/climate-change-childrens-stories

- Oziewicz, M. (2023a). The CLICK framework: A care-centric conceptual map for organizing climate literacy pedagogy. Climate Literacy in Education, 1(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.24926/cle.v1i2.5438

- Oziewicz, M. (2023b). What is climate literacy? Climate Literacy in Education, 1(1), 1–3. https://pubs.lib.umn.edu/index.php/clj/issue/view/303 https://doi.org/10.24926/cle.v1i1.5266

- Patten, M. L. (2017). Questionnaire research: A practical guide. Routledge. (Original work published 1986)

- Plumwood, V. (2002). The blindspots of centrism and human self-enclosure. In V. Plumwood, Environmental culture: The ecological crises of reason (pp. 13–37). Routledge.

- Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 681–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

- Reisberg, M. (2008). Social/Ecological caring with multicultural picture books: Placing pleasure in art education. Studies in Art Education, 49(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2008.11518739

- Ross, J. (2014). Why do most Black and Latino students go to two-year colleges? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/05/why-do-a-majority-of-black-and-latino-students-end-up-at-two-year-colleges/371423/

- Russel, D. (2019). Literature for children: A short introduction. Pearson.

- Scharrer, E., & Ramasubramanian, S. (2021). Quantitative research methods in communication: The power of numbers for social justice. Routledge.

- Sobel, D. (2007). Climate change meets ecophobia. Connect, 21(2), 14–21. http://www.synergylearning.org/wp-content/uploads/CONNECT-final-NOV-DEC-2007.pdf

- Sobel, D. (2008). Childhood and nature: Design principles for educators. Stenhouse.

- The EdUp Experience Podcast. (2023). 715: Walking in your purpose-with Dr. Mautra Staley Jones, president of Oklahoma City Community College. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/vl1cuMD9kQ0?si=Pt488RhfQrNNlfmg [DA1]

- Tunnel, M., & Jacobs, J. (2008). Children’s literature briefly. Pearson.

- Warren, K. J. (2000). Ecofeminist philosophy: A Western perspective on what it is and why it matters. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Young, E. (1992). Seven blind mice. Philomel Books.

Appendix A:

Qualitative questions asked of student participants

Please explain why you think it is important or not important to teach social justice concepts in relation to literature for children.

Please explain why you think it is important or not important to teach environmental concepts in relation to literature for children.

What specific aspect(s) about social justice do you think should be covered in Literature for Children’s course that would help future educators teach about this topic?

What specific aspect(s) about ecological (environmental) justice do you think should be covered in Literature for Children’s course that would help future educators teach about this topic?

What questions do you have about teaching social justice through literature for children?

What questions do you have about teaching ecological (environmental) justice through literature for children?

Appendix B:

Faculty closed ended questions requesting likert scale responses following definitions

Definitions of terms used in this survey are presented below and before certain questions which may be helpful when considering your responses.

Pedagogy – consider this to be both teaching methods and content (activities and assessments).

Social justice (SJ) pedagogy is an educational approach focusing on equity literacy. It prioritizes a redistribution of access and opportunity across axes of power, leveraging systemically marginalized groups and building accountability practices for learners. Social justice pedagogy is informed by culturally relevant and sustaining theory and practice, fostering learners’ critical consciousness and cultivating their agency to act for social change.

EcoJustice pedagogy is an educational approach emphasizing social and ecological justice convergence. It seeks to critically transform teaching to be more sustainable and just and combat violence and oppression that minoritized groups and the natural world experience. EcoJustice pedagogy equips learners with the knowledge and value of the interdependency of humans and the natural world. It cultivates learners’ agency to redress social-ecological subjugation.

Note: The purpose of the following questions is to assess your perception, integration, and application of Social Justice pedagogy and EcoJustice pedagogy. You may have intentionally designed your course with these aspects in mind or they may have happened more ‘organically’ with or without knowledge of specific theory or vocabulary. When considering the integration and application of Social Justice pedagogy and EcoJustice pedagogy, they might manifest in your courses in multiple ways and places. For example, you might assign students to read a historical novel about racism, which becomes an entry port for a discussion about fairness and equity. Maybe later in the course, this discussion is linked to current equity issues or ecological crises, etc.

How often do you believe you use social justice pedagogy in your Children’s Literature courses?

In what ways do you integrate or incorporate social justice pedagogy in your Children’s Literature courses?

What factors, if any, limit your inclusion of social justice pedagogy in your Children’sLiterature courses?

To what extent to you agree that teaching social justice pedagogy is important in a Children’s Literature course?

How often do you believe you use EcoJustice pedagogy in your Children’s Literature courses?

In what ways do you integrate or incorporate EcoJustice pedagogy in your Children’s Literature courses?

What factors, if any, limit your inclusion of EcoJustice pedagogy in your Children’s Literature courses?

To what extent do you agree that teaching EcoJustice pedagogy is important in a Children’s Literature course?

Are you familiar with the term climate literacy?

Questions 2, 3, 6, 7 include multiple-response sets with an option to write in other possibilities. Questions 1, 4, 5, 8, 9 are Likert scale questions based on agreement.