Abstract

Based on the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, this study examined the effectiveness of a brief psychological intervention to reduce study-related stress and enhance well-being. Our three-hour intervention taught students psychological strategies to cope with stress specifically tailored to their study situation. Our sample (N = 56) was comprised of advanced law students who were within a 12-to-18-month period of exam preparation. We applied a randomized controlled trial which included an intervention and an active waitlist control group. Students gave self-reports immediately before and after the intervention, as well as at baseline, one, and two weeks later (post and follow-up). Repeated-measure analyses of variance revealed a significant stress reduction right after the intervention but no significant improvement in well-being. Post-measurement showed a reverse pattern in that the intervention significantly enhanced students’ well-being but did not reduce their stress. Intervention effects remained stable at follow-up. The waitlist control group also showed lower levels of stress and higher levels of well-being after receiving the intervention. Overall, the brief intervention showed short-term effectiveness, boosting study-related well-being in particular. These results expand previous findings demonstrating the effectiveness of brief interventions during study periods with chronic stress characteristics.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Pursuing a degree in higher education has been shown to be a stressful undertaking for many students, taking a toll on their well-being (Bewick et al., Citation2010; Evans et al., Citation2018; Ribeiro et al., Citation2018; Xiang et al., Citation2019). Exam periods in particular have been linked to increased stress levels and decreased overall functioning (Ahrberg et al., Citation2012; Campbell et al., Citation2018; Lyndon et al., Citation2014; Zunhammer et al., Citation2013). Stress results from the subjective discrepancy between external or internal demands and available coping resources in a given situation that is typically perceived as unpredictable and uncontrollable (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Well-being results from the subjective cognitive and affective evaluations of a person’s life that includes life satisfaction as well as positive and negative affect (Diener, Citation1984). In the context of exam periods, academic stress can have both acute and chronic characteristics and heavily depend on the time students invest in preparation (i.e. studying for several weeks or months) as well as the relative importance of the final examination (Giglberger et al., Citation2022; Maydych et al., Citation2017). There is ample evidence that exam-related stressors associated with state examination formats, such as those in medical school, are experienced as particularly stressful (Duan et al., Citation2013; Multrus et al., Citation2017; Peters et al., Citation2017). State exams require extensive preparation, leading to a prolonged period of academic stress.

In Germany, obtaining a law degree requires an average of ten semesters. The first state exam is comprised of five to eight written exams taken within a two-week period, each exam lasting 5 hours in duration. In addition, students submit to a 90-minute oral exam a few months later. Students must choose from two possible exam dates offered during the academic year. Passing each written exam is considered very demanding since students need to solve a complex legal case within one topical area of law. Notably, exam performance is 70% of each student’s final law school grade, and failure rates are at 25–30%, constituting an additional psychological burden. Even though students are permitted a second attempt, there is a high risk of dropout following a failed first attempt (Ernst, Citation2018; Heublein et al., Citation2017). If students successfully pass their first attempt, they can use the second attempt to improve their grade. Either way, the final grade achieved within the first state exam has a substantial impact on career prospects (Towfigh et al., Citation2018).

Unlike other state examination formats, the German system of legal education entails an unusually long preparation time for the first state examination (Glöckner et al., Citation2013; Lobinger, Citation2016). Students typically start their exam preparation after their sixth semester and then take 18 months on average to prepare for their final exams (Busch, Citation1990; Sanders & Dauner-Lieb, Citation2013). Exam preparation requires students to review extensive study material and apply legal reasoning through mock exams. To meet their learning objectives, most students cut back on stress-reducing activities that enhance well-being. Exam preparation therefore constitutes a long-lasting and significant stress period, increasing the law student’s risk of chronic stress and resulting in negative trajectories for both physiological and psychological health (Giglberger et al., Citation2022, Citation2023; Rabkow et al., Citation2020; Reschke et al., Citation2023). While acute stress has been found to have positive effects, chronic stress constitutes a risk factor for psychological and physiological well-being and stress-related psychiatric diseases such as depression and anxiety disorders (Chrousos, Citation2009; Juster et al., Citation2010; McEwen, Citation2004).

Psychological interventions have been found to reduce stress and improve well-being among university students. Specific approaches, such as mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and technology-delivered interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing stress and enhancing well-being when compared to passive controls (Amanvermez et al., Citation2021; Halladay et al., Citation2019; Harrer et al., Citation2018; Howell & Passmore, Citation2019; Winzer et al., Citation2018). Interventions that focused on CBT, coping skills, psychoeducation, and social support were shown to be effective in reducing stress, (Yusufov et al., Citation2019) yielding medium effect sizes. Meta-analyses typically distinguish between brief (1–4 weeks), moderate (5–8 weeks), and long-term interventions (8+ weeks) (Amanvermez et al., Citation2023; Yusufov et al., Citation2019). However, many studies did not specifically adapt intervention content to the context of the university to meet students’ needs (Seidl et al., Citation2016; Sheehy & Horan, Citation2004; Yusufov et al., Citation2019). For example, brief interventions would be especially beneficial for advanced law students during exam preparation as students typically have limited time outside of their studies (Multrus et al., Citation2017; Rabkow et al., Citation2020). However, most interventions require students to participate over several weeks. Overall, there is very little evidence on brief interventions that were designed to address particular study periods such as prolonged exam preparation. Brief stress reduction interventions have been discussed to be more effective when tailored to a particular student group (Amanvermez et al., Citation2021; Van Daele et al., Citation2012; Yusufov et al., Citation2019).

The present study is based on the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TSC; Folkman, Citation2008; Lazarus, Citation2006; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). In the context of TSC, stress arises from a complex interaction between the demands of a given situation and the perceived resources for coping, all an internal process of cognitive evaluations. According to Lazarus and colleagues (Lazarus, Citation1966; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), a person perceives certain stimuli from the environment (potential stressors) and then makes a cognitive assessment as to whether these should be classified as positive, irrelevant, or stress-related (primary appraisal). If a situation is evaluated as stress-related, that person makes another assessment as to whether the individual resources to deal with the stressful situation are sufficient (secondary appraisal). The stress response is elicited when the person assesses his or her available resources as insufficient for coping with the demanding situation (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). To resolve this state, the TSC further assumes that two central pathways are available to deal with stress: problem-oriented and emotion-oriented coping. Whereas the problem-focused coping option holds mainly cognitive strategies to deal with the stressful event and aims at managing the source of the problem, the emotion-focused coping option involves emotional strategies to decrease negative feelings and feel better (Folkman, Citation2008; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984).

This study aimed to examine the positive effects of a brief psychological intervention on students’ subjective stress and well-being during prolonged exam preparation. We implemented a three-hour workshop that aimed to reduce stress and enhance well-being based on TSC principles (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). We expected participating students to report (a) lower levels of study-related stress and (b) higher levels of study-related well-being after the intervention. We used a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and applied a pre-post design, including an additional follow-up measurement at one-week intervals each. Students were randomized into an intervention group (IG) and an active waitlist control group (CG) to test for intervention effectiveness on a between-subject level. The IG received the intervention between pre and post-measurement, while the CG received it between post and follow-up measurement. In addition, we included immediate measurements right before and after the intervention to test for intervention effectiveness on a within-subject level. Following our expectations, we derived the following research hypotheses:

A. Immediate intervention effectiveness (differences on a within-student level).

Hypothesis 1: All students who participate in the intervention report lower levels of study-related stress right after the intervention than before it.

Hypothesis 2: All students who participate in the intervention report higher levels of study-related well-being right after the intervention than before it.

B. Short-term intervention effectiveness (differences on a between-student level):

Hypothesis 3: IG students report lower levels of study-related stress at post-measurement compared to controls which shows up in a time × group interaction.

Hypothesis 4: IG students report higher levels of study-related well-being at post-measurement compared to controls which shows up in a time × group interaction.

C. Short-term intervention effectiveness stability (differences on a within-student level):

Hypothesis 5: IG students report their study-related stress to be stable at follow-up measurement while controls also benefit from the intervention which shows up in a time × group interaction.

Hypothesis 6: IG students report their study-related well-being to be stable at follow-up measurement while controls also benefit from the intervention which shows up in a time × group interaction.

2. Method

2.1. Sample and procedure

A total N = 61 students took part in our intervention study (baseline and post) with n = 41 students taking part in all three measurement occasions including follow-up (34% dropout). We excluded five students that reported a major critical life event to have influenced their well-being within the last weeks. Our final sample thus comprised N = 56 students (84% female) who were all actively enrolled at one large German university. The mean age was M = 23.98 years (SD = 2.24). All participants were advanced law students amidst their exam preparation to complete their studies and earn their law degree. Most students were in their 7th semester (M = 9.29, SD = 2.67, range 6–19) and in their second month of exam preparation (M = 8.35, SD = 6.13, range 1–24). The average student planned at least 18 months for preparation (M = 18.24, SD = 4.60, range 10–36) and had approximately ten months until their exam date.

We advertised for intervention participation via the faculty’s website, internal mailing lists, and social media. Students could then mail a staff member to express their wish to participate. We defined three inclusion criteria: Students needed to be within their exam preparation period, scheduled for their final exams within the next 18 months, and be willing to take part in the study. Students were randomly assigned to one of the two groups (IG vs. CG) by receiving a random number from the researchers conducting the study. Data was collected over three weeks in late 2017 using short self-report measures. Students were e-mailed links to the corresponding online questionnaires (baseline, post, and follow-up), and informed consent was obtained. A brief questionnaire was handed out right before and after the intervention for immediate assessment.

The intervention was offered in two consecutive weeks. The IG received the intervention between pre and post-measurements (t0 and t1), whereas the CG received it between post and follow-up measurements (t1 and t2). Since the IG received the workshop a week earlier, we wanted to ensure the CG was not left completely untreated. The video shown to the CG was intended to provide students with a certain degree of attention. This was to ensure that the reduction in the experience of stress was due to the actual experimental manipulation and not to the mere offering of a novel format. Therefore, differences at post-measurement should be attributable to the effect of the actual intervention (experimental manipulation). Control students were sent a twenty-minute video on creative ideas for studying. Two-thirds of the students within the CG reported having watched the short video. A final number of n = 26 students representing the IG whereas n = 30 were controls. The intervention was standardized in terms of time and place, as well as by the use of an intervention manual. It covered six modules and included a short break. The intervention was facilitated by a male psychologist roughly the same age as participants and with five years of teaching experience. Participants received no financial compensation, and the study design was approved by the local ethics committee.

2.2. Intervention

The intervention was delivered in a three-hour workshop specifically tailored to students undergoing prolonged exam preparation and addressed psychological stress and coping skills. The content of the intervention was built on the results of a previous interview study, and therefore, was adapted to students’ psychological needs. Within the three-hour workshop, students were taught six modules to reduce their stress and enhance their well-being during exam preparation. The intervention was divided into two parts with three modules each (time management, effective learning, and functional thinking routines vs. emotion management, relaxation training, and social support). The first part was based on stress prevention with a problem-focused coping orientation. Students learned about helpful ways to act on stressors and appraise situations differently. The second part was based on stress reduction with an emotion-focused coping orientation.

The intervention started with an introduction during which students described their motivation to take part in the workshop. Directly addressing students’ current situation, results of a pilot study about stress during prolonged exam preparation were briefly presented (Reschke et al., Citation2023). Students were then acquainted with stress theory and learned about four different ways of recognizing stress (cognition, emotions, behavior, and body). Lastly, students were familiarized with the transactional stress theory to better understand how psychological stress occurs.

Part 1: Stress prevention (problem-focused coping)

The time management module (1) covered the importance of circadian rhythms which regulate learning performance such as the ability to concentrate. This module described ‘brain-friendly’ study breaks and ways of dealing with distractions posed by modern media, promoting effective learning. The effective learning module (2) taught strategies to support active problem-solving. Students learned about preconditions for sustainable knowledge acquisition and how to best set goals and priorities. This included ideas about planning buffer times for learning and the importance of exam practice (i.e. taking mock exams to practice legal analysis). The functional thinking routines module (3) was based on cognitive reappraisal and restructuring of stress-reinforcing cognitions. This module discussed certain personified thoughts that many students are confronted with during exam preparation (e.g. the inner critic, the bad conscience, the fear of failure). Students learned to better identify negative thinking and were provided a list of positive reappraisals and self-instructions to use during exam preparation.

Part 2: Stress prevention (emotion-focused coping)

The emotion management module (4) focused on reducing negative feelings and enhancing positive feelings. This module was comprised of different methods from positive psychology and emphasized regular positive activities after studying to create a sense of purpose, self-affirmation, and achievement in leisure (e.g. drawing or cooking). Students practiced enjoyable habits such as slowly eating a piece of chocolate or writing in a happiness journal that was handed out to them. The relaxation training module (5) informed students about the relaxation response as the physiological counterpart to the stress response. This module included a brief motivational video underscoring the important role of regular relaxation exercises in promoting recovery and maintaining balance. Students then practiced a mindfulness-based breathing relaxation exercise followed by a brief reflection. The very same guided relaxation was later sent to students as an audio track for further use. The final social support module (6) discussed the stress and anxiety-relieving effects of social support. Students learned about recognizing and making use of individual networks (e.g. roommates, friends, parents) and structural networks at university (e.g. fellow students, study groups, professors). This included highlighting the benefits of study groups that foster learning and make exam preparation a team project. Lastly, students watched a set of short motivational videos in which some of their professors talked about their own exam preparation challenges and how they overcame them.

The workshop ended with a wrap-up of the main ideas and a brief reflection on individual experiences. Students got to take different materials home to encourage integration of skills into their daily study routine (summary sheet, list of positive self-instructions, happiness journal, extra chocolate, guided audio relaxation).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Study-related stress

We assessed students’ perceived stress right before and after the intervention to account for immediate intervention effectiveness. Students were asked to mark their current stress level on a visual analog scale ranging from 0 (not stressed at all) to 10 (completely stressed out) using one item. This approach is often used to obtain momentary stress assessments in the course of interventions (Heinrichs et al., Citation2015). To measure short-term intervention effectiveness, we used the Heidelberg Stress Index (HEI-STRESS, Schmidt et al., Citation2018). The HEI-STRESS is a brief measure of subjective stress that relies on one scale with three items that were specifically developed for university students (Schmidt & Obergfell, Citation2011). The first item asks students to rate their subjective stress ranging from 0 (not stressed at all) to 100 (completely stressed out). The second item requires students to rate the frequency of general physical tension on a rating scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (daily). The third item asks students to evaluate the current stress in their lives on a rating scale ranging from 0 (not stressful at all) to 4 (very stressful). All items were answered with a seven-day time reference. The final score of the scale ranges between 0 and 100 and is computed with the formula (item 1 + (item 2 × 25) + (item 3 × 25))/3. The HEI-STRESS internal consistencies were satisfactory for all measurement occasions with α = .79 for baseline, α = .85 for post, and α = .79 for follow-up.

2.3.2. Study-related well-being

We also assessed study-related subjective well-being, including the cognitive and affective components that constitute psychological well-being. For lack of a suitable instrument to measure study-related well-being in the higher education context, we comprised study-related well-being from the following instruments.

2.3.2.1. Life and study satisfaction

We measured students’ perceived study satisfaction right before and after the intervention. They answered one item on a visual analog scale ranging from 0 (not satisfied at all) to 10 (completely satisfied). To account for short-term intervention effectiveness, we applied the Satisfaction With Life and Studies Scale (LSS, Holm-Hadulla & Hofmann, Citation2007). This questionnaire originates from the Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al., Citation1985) and measures the cognitive component of study-related well-being. Developed for higher education settings such as exam preparation, the LSS includes study satisfaction as a subdomain of life satisfaction. Both life and study satisfaction load on a single factor with α = .79 since academic and private life are assumed to be two life domains that are strongly interrelated for students (Holm-Hadulla et al., Citation2009). The entire scale consists of seven items. The life satisfaction subscale includes four items that focus on students’ personal life situation in terms of their perceived performance and functioning as well as their overall life satisfaction (e.g. ‘How healthy and productive do you currently feel?’, ‘How satisfied are you with your current life?’). The study satisfaction subscale has three items that focus on performance and situational aspects of studying (e.g. ‘How satisfied are you with your current academic achievements?’, ‘How satisfied are you with your current study situation?’). Students based their answers on the last seven days and were presented a rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) for all items. The internal consistencies were good at all measurement occasions and ranged from α = .82 for baseline and post to α = .84 for the follow-up-measurement.

2.3.2.2. Positive and negative affect

We applied the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Short Form (I-PANAS-SF, Thompson, Citation2007) to measure the affective component of study-related well-being. This questionnaire builds on the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS, Watson et al., Citation1988) and was further condensed and refined to fit time-constrained settings such as brief interventions. The shortened PANAS used comprises ten items for both subscales: five items for positive affect (‘alert’, ‘inspired’, ‘determined’, ‘attentive’, ‘active’) and five items for negative affect (‘upset’, ‘hostile’, ‘ashamed’, ‘nervous’, ‘afraid’). Students answered their experiential intensity on all items on a rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). They did so on a momentary basis right before and after the intervention as well as on a short-term basis with a seven-day time reference. The internal consistencies for each subscale were mostly acceptable at all measurement occasions both ranging from α = .66 to α = .80.

Study-related well-being was calculated as a composite score based on those single instruments (study-related satisfaction plus positive and negative affect). For immediate intervention effectiveness, we added the value of the study satisfaction VAS-item with the respective mean values for the positive and (inverted) negative affect subscales of the PANAS and got an average well-being score. The following formula was used to receive a final score ranging from 1 to 10 [(((VAS-item value) +1) + PA mean value + NA mean value)/2]. This procedure allowed comparability with study-related stress before and after the intervention. For short-term intervention effectiveness, we added the mean value of the Satisfaction With Life and Studies Scale with the respective PANAS means and calculated the overall mean for study-related well-being. Joint internal consistencies were good at all measurement occasions ranging from α = .82 to α = .88.

2.3.3. Control variables

We assessed three additional variables to control for potential bias. We asked students to provide more information about their current study situation to check for equal groups at baseline measurement. First, we included a brief instrument to test for personality because neuroticism has been shown to affect subjective stress evaluations in students (Austin et al., Citation2010; Schmidt et al., Citation2015). We used the Big Five Inventory-10 to assess basic personality traits (BFI-10, Rammstedt & John, Citation2007) and focused on the two-item neuroticism subscale to account for negative affectivity (‘I see myself as someone who is relaxed, handles stress well (reverse coded)’, ‘I see myself as someone who gets nervous easily’). Students rated both items on a scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Second, we asked students to report time until examination because we expected them to rate their study-related stress and well-being differently depending on how many months they have left until taking the exam. Studies have shown students report more pronounced stress during examination periods than the proceeding time period (e.g. Zunhammer et al., Citation2013). In our study, students prepared for one out of three possible exam dates that fell into three categories (March 2018, September 2018, or March 2019). Third, we identified whether students were preparing for the first time (initial attempt) or preparing to improve their grade (second attempt), creating two additional categories.

2.4. Statistical analyses

All data was analyzed using SPSS (version 25). With regard to the RCT, we first tested for group equivalency at baseline using independent t-tests for both groups and applied one-tailed tests to examine our hypotheses. We applied two one-way repeated measures analyses of variance (RM-ANOVA) to examine immediate intervention effectiveness for both outcomes (hypotheses 1 and 2). To examine short-term intervention effectiveness, we applied two-way RM-ANOVAs including both groups (IG vs. CG) and pre vs. post measurement. This approach allowed us to test the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing stress and enhancing well-being by finding a time × group interaction (hypotheses 3 and 4). Moreover, to test for intervention effectiveness stability, we ran two equivalent RM-ANOVAs to check for another time × group interaction. This was done to examine whether students in the IG remained stable on their study-related stress and well-being at follow-up measurement and whether controls also benefited from the intervention (hypotheses 5 and 6).

We performed theory-driven outlier analyses and checked for relevant statistical assumptions such as testing for normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests for both groups and all time points. Missing data was neither replaced nor substituted by imputation methods because missing values were scattered and followed a random pattern. Moreover, group sizes were small and would have introduced bias. We included three control variables as covariates in all analyses to check for potential bias. For interpreting the magnitude of all mean differences, we calculated effect sizes (Cohen’s d).

3. Results

We first tested for group equivalency at baseline. Independent t-tests for both groups revealed no significant differences neither for study-related stress and well-being nor for the control variables which made randomization successful (see ).

Table 1. Summary of baseline characteristics using independent-samples t-tests with respective means and standard deviations for both groups.

3.1. Immediate intervention effectiveness

A total number of n = 53 students gave ratings on their study-related stress and well-being right before and after the intervention. All students (IG and CG) reported higher stress levels before (M = 4.7, SD = 1.92) than after the intervention (M = 2.67, SD = 1.85) with higher levels of well-being afterward (M = 4.11, SD = 1.11) than before (M = 3.79, SD = 1.06). With regard to our first hypothesis, results showed that students’ stress levels were significantly lower after the intervention than before the intervention, F(1, 49) = 4.27, p = .044, d = 0.50. All three control variables had no significant impact on the changes in students’ stress levels. This finding supported our first hypothesis and revealed a medium effect size that suggests that the intervention was immediately effective in reducing students’ stress levels. Concerning our second hypothesis, results showed a non-significant effect on students’ levels of well-being, F(1, 49) = 3.29, p = .076, d = 0.41. All three control variables had no significant impact on the changes in students’ levels of well-being. Our second hypothesis was not supported.

3.2. Short-term intervention effectiveness

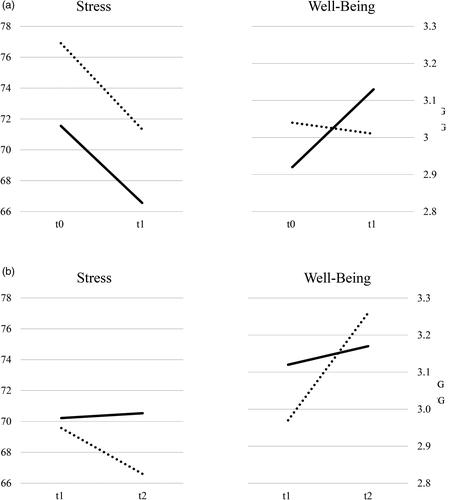

Looking at study-related stress, both IG students (n = 26) and CG students (n = 29) gave ratings on their study-related stress at baseline and post-measurement. When testing our third hypothesis, results revealed a non-significant interaction effect of time × group, F(1, 50) = 0.02, p = .89, d = 0.04. This finding did not support our third hypothesis because the changes in students’ stress levels were not significantly different between groups. depicts that both groups declined in their stress levels from baseline to post-measurement (Baseline: IG M = 71.55, SD = 15.68, CG M = 76.91, SD = 10.7; Post: IG M = 66.56, SD = 17.25, CG M = 71.33, SD = 15.02). There were no effects of the covariates.

Figure 1. (a) Short-term effectiveness of the brief psychological intervention for study-related stress and well-being. Lines show students’ stress and well-being levels for baseline and post-measurement with respect to the intervention group (IG; n = 26) and control group (CG; n = 29). The time interval between t0 and t1 is one week. (b) Short-term effectiveness stability of the brief psychological intervention for study-related stress and well-being. Lines show students’ stress and well-being levels for post and follow-up measurement with respect to the intervention group (IG; n = 22) and control group (CG; n = 19). The time interval between t1 and t2 is one week. CG students received the intervention between t1 and t2.

Turning to study-related well-being, n = 26 students within the IG and n = 30 controls rated their study-related well-being at baseline and post-measurement. Regarding our fourth hypothesis, the time × group interaction was significant, F(1, 51) = 5.62, p = .02, d = 0.66, indicating that the change in well-being levels in the IG was significantly different from the change in the control group. This finding supported our fourth hypothesis indicating the intervention to have increased students’ well-being levels with a medium to large effect size. See for a graphical representation. Students of the IG significantly increased their well-being compared to the CG (Baseline: IG M = 2.92, SD = 0.55, CG M = 3.04, SD = 0.58; Post: IG M = 3.13, SD = 0.5, CG M = 3.01, SD = 0.6). There were no effects of the covariates.

3.3. Short-term intervention effectiveness stability

With regard to study-related stress, there were n = 19 students in the IG and n = 22 in the CG that provided ratings at post and follow-up measurement. Results on our fifth hypothesis revealed a non-significant interaction effect of time × group, F(1, 36) = 1.27, p = .27, d = 0.36. All three control variables had no significant impact on the changes in students’ stress levels. IG students reported equally high stress levels at post (M = 70.22, SD = 16.23) and follow-up (M = 70.53, SD = 17.02). In contrast, controls reported declining stress levels from post (M = 69.57, SD = 16.40) to follow-up (M = 66.6, SD = 18.76). Even though students participating in the intervention showed stable stress levels compared to controls, the missing time × group interaction did not support our fifth hypothesis. The results are also depicted in . However, follow-up analyses showed a non-significant main effect of time reflecting stress level stability for the IG, F(1, 15) = 0.68, p = .42, d = 0.27.

Turning to study-related well-being, n = 19 students in the IG and n = 22 controls gave ratings at post and follow-up measurement. Regarding our sixth hypothesis, the time × group interaction was significant, F(1, 36) = 4.67, p = .037, d = 0.72, which suggests that the change in well-being levels of IG students was significantly different from the change of controls. IG students reported their well-being to be stable from post (M = 3.12, SD = 0.53) to follow-up (M = 3.17, SD = 0.64). To the contrary, controls reported their well-being levels to have increased from post (M = 2.97, SD = 0.55) to follow-up (M = 3.26, SD = 0.45). This finding supported our sixth hypothesis in that IG students showed stable well-being levels compared to controls. shows a graphical illustration. Once again, there were no effects of the covariates.

4. Discussion

This was the first experimental study to examine the immediate and short-term causal effects of a brief psychological intervention for students undergoing a study period of prolonged academic stress. Given the chronic stress characteristics of exam preparation, we implemented a single session three-hour intervention that taught advanced law students psychological strategies tailored to their study situation. The intervention showed both immediate and short-term effectiveness revealing a distinct pattern for study-related stress and well-being. In the following, we discuss our results along with the hypotheses, mention limitations, and provide practical recommendations.

4.1. Immediate intervention effectiveness

In line with hypothesis 1, all students (IG and CG) reported being less stressed right after the intervention than at the beginning. This indicates that the intervention was effective in reducing study-related stress levels on an intraindividual level (d = 50). However, contrary to hypothesis 2, students did not report feeling better immediately after the intervention. Despite its positive trend (d = 0.41), the intervention was not effective in improving students’ well-being on an immediate time horizon. This is in line with previous work that showed brief psychological interventions to reduce stress levels quite quickly when university students were targeted (e.g. Call et al., Citation2014; Renshaw & Rock, Citation2018). Moreover, there is evidence that such interventions have more pronounced positive effects on stress than on subjective well-being (Renshaw & Rock, Citation2018). It is likely that the positive impact on well-being would unfold over time, and therefore, did not show up within one day in our study. This is also why we looked at short-term effects over the period of one week.

4.2. Short-term intervention effectiveness

Contrary to hypothesis 3, there was no significant time × group interaction for study-related stress after one week. Changes in students’ stress levels were not significantly different from each other because both groups (IG and controls) reported being less stressed from baseline to post-measurement. It is unclear to what this nearly parallel decrease in the stress levels of both groups can be attributed. It is rather unlikely that watching the video had a positive effect on reducing the stress levels of CG students. The video was brief at only 20 minutes and covered creative thinking which is of little importance in exam preparation. However, the video may have made students think less about exam-relevant requirements. The study took place during a typical semester when students were in the midst of routine exam preparation. Two possibilities could potentially explain this effect. On one hand, the offer of a workshop could have been so well-received by students that the very prospect of such an opportunity could have led to a reduction in stress in controls. On the other hand, the intervention may not have had enough strength to reduce stress in IG students and thus produce the desired interaction effect. This would validate earlier findings that have argued law students suffer from persistently high levels of stress during exam preparation (Reschke et al., Citation2023; Sanders & Dauner-Lieb, Citation2013). Two recent studies provide evidence that students suffer from chronic stress during exam preparation and results of longitudinal analyses showed blunted alterations in their cortisol release upon awakening (Giglberger et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). Therefore, students’ stress experiences could have been too pervasive, thus undermining a stronger stress-reducing effect of the intervention. Furthermore, the stress-reducing effect for both groups of students could have occurred because students exchanged ideas after the first workshop, allowing students of the control group to apply some of the strategies taught.

In line with hypothesis 4, however, there was a significant time × group interaction for study-related well-being after seven days. Changes in study-related well-being were significantly different from each other due to intervention participation from baseline to post-measurement, indicating the positive effects of the intervention unfolded over one week. The intervention increased student well-being in the short term with a medium to large effect size (d = 0.66). This is in line with previous studies showing that students’ levels of well-being were higher after taking part in psychological interventions that focus on positive emotions, behaviors, and thoughts (Howell & Passmore, Citation2019, Renshaw & Rock, Citation2018). Students received advice on how to uphold a good level of subjective well-being during exam preparation. Offering them different ideas on how to reduce negative feelings and enhance positive feelings may have been what students needed.

Taken together, the results on immediate and short-term intervention effectiveness show a reverse pattern. The intervention had an effect on study-related stress but not well-being on an immediate time horizon. In the short term, the intervention had an impact on study-related well-being but not stress. This constitutes an interesting finding as it is possible that the brief and tailored nature of the intervention made students more satisfied but not less stressed after one week given academic demands remained the same. Despite evidence suggesting the effectiveness of shorter interventions in reducing study-related stress (Breedvelt et al., Citation2019; Halladay et al., Citation2019), stress reduction during prolonged exam preparation may require a lengthier (or more comprehensive) psychological intervention.

4.3. Short-term intervention effectiveness stability

In line with hypothesis 5, stress levels of IG students remained stable two weeks after taking part in the intervention. Students reported equal stress levels from post to follow-up measurement. This indicates that the strategies taught in the workshop were helpful and that the intervention had lasting positive effects on students’ stress levels. Interestingly, control students also benefitted from the intervention as the stress-reduction effect appeared as well following the workshop. This mirror image pattern of decreasing stress levels provides further evidence that the workshop was successful in addressing relevant issues to reduce study-related stress in the short term. It is possible that the tailored nature of the intervention played a role in this pattern showing up. Previous research has indicated target group-specific adaptation of training content has several advantages (Seidl et al., Citation2016; Yusufov et al., Citation2019).

In line with hypothesis 6, well-being levels of IG students also remained stable after two weeks. Students reported equal levels of well-being from post to follow-up measurement. This finding provides support that the intervention may have helped maintain and uphold a certain level of well-being showing that the intervention had lasting positive effects. Again, control students also benefited from the intervention as the enhancing effect for well-being showed once more. This mirror image pattern of increasing well-being levels in controls provides additional support that the workshop was successful in addressing key concerns in improving study-related well-being in the short term, replicating previous studies showing psychological interventions have positive effects on well-being (Conley et al., Citation2013; Howell & Passmore, Citation2019; Winzer et al., Citation2018).

Of note, the stress levels of IG students decreased from t0 to t1 and stayed stable at t2 meaning that stress did not increase after the intervention. Moreover, the results of the follow-up show that both stress and well-being levels of the IG students remained stable over the course of two weeks. Additionally, the intervention effects were visible twice as the control group also benefited from the intervention. This can be interpreted in terms of the goodness of the intervention. Participating students received lots of material to take home, and this could have been a key factor encouraging integration into daily study situations (e.g. happiness journal, guided audio relaxation). It is possible that by participating in the intervention, students felt they were now better equipped to continue with their exam preparation, even in the face of continued academic stress.

4.4. Limitations and further research

Due to the short-term nature of our study, it is not clear whether the intervention effects were sustainable over a longer period of time. Even though our approach intentionally entailed very little participant burden, future research should examine long-term effects (e.g. one month, six months) specifically for students undergoing prolonged exam preparation. In addition, the sample was relatively small, so future studies should validate the effectiveness of the intervention using larger samples. Furthermore, we drew our causal conclusion based on self-reports solely. Future intervention studies should take physiological measures such as salivary cortisol into account. Moreover, we examined advanced law students only which makes it difficult to generalize our findings to other student groups undergoing prolonged academic stress. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to further examine the effectiveness of tailored psychological interventions to reduce stress and enhance well-being.

4.5. Practical implications

Our study has important practical implications for intervention efforts during stressful study periods in higher education contexts. The results suggest that creating brief psychological interventions beyond traditional approaches, which typically take several weeks for students to complete, can be useful. Due to their short duration, brief interventions require little participant burden and fit into academic structures more easily, better facilitating the transfer of competencies into everyday study life. Moreover, brief interventions like our three-hour workshop are a feasible format that can effectively reduce stress and enhance the well-being of university students. This becomes particularly important when studying is prolonged, such as in months-long exam preparation (e.g. advanced law students preparing for their final exams within the German system of legal education). For these students with chronically high stress levels, brief interventions can play a crucial role in addressing stress-related complaints and help prevent mental illness (Giglberger et al., Citation2022; Halladay et al., Citation2019; Rabkow et al., Citation2020; Van Daele et al., Citation2012).

The findings of our study also indicate there is value in tailoring stress reduction interventions to the specific context of the student, such as prolonged periods of exam preparation. Study periods such as these place an unusually high academic burden on students that can exceed coping resources and increase stress levels. Providing students with psychological strategies that are more easily integrated into daily study routines increases the likelihood of continued practice and sustained stress reduction. In this context, studies suggest that tailoring interventions toward particular groups and outcomes is promising (Seidl et al., Citation2016; Yusufov et al., Citation2019). When establishing psychological support services, universities should consider the unique needs of students undergoing prolonged exam preparation. Tailored interventions would positively impact students’ current study situation by reducing study-related stress. In doing so, they also have the potential to enhance study-related well-being.

5. Conclusion

Challenging study periods such as exam preparation lead to prolonged academic stress that negatively affects students’ well-being. Prolonged exam preparation holds chronic stress characteristics that call for tailored stress reduction interventions. Our brief psychological intervention helped law students preparing for final exams increase their study-related well-being and reduce their stress in the short term. There is great potential in providing students with brief and tailored interventions that are both accessible from a time management perspective and easily integrated into their daily lives. By implementing targeted and effective interventions, universities can play a key role in improving the lives of students undergoing stressful study periods.

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants for their interest in our research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tom Reschke

Tom Reschke, Master of Science in Psychology, is a PhD student at Heidelberg University, Germany. He is investigating the effectiveness of various intervention approaches to reduce stress of law students preparing for their final exams. He developed an individual coaching concept specifically for exam candidates and has a distinguished background including psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g., systemic therapy, clinical hypnotherapy, relaxation training and stress management). He is also self-employed and runs a company named TALENT SAFARI that offers psychological diagnostics, counseling, and training in the context of school and education.

Thomas Lobinger

Thomas Lobinger, is professor of Civil Law, Labor, and Commercial Law at Heidelberg University, Germany. He is the faculty representative for exam preparation. He served as dean for the law faculty, and was awarded the “Ars legendi” faculty prize for excellent teaching in 2013. He stands for exam preparation that focuses on the legal tools of the trade and combines the teaching of relevant exam knowledge with in-depth academic study of key problems. He is the initiator of the project called “Exam Villa”, which offers students the opportunity to work together in an inspiring environment during exam preparation.

Katharina Reschke

Katharina Reschke, PhD in Psychology, studied psychology at Heidelberg University, Germany and completed her dissertation on the topic of “The relative importance of motivation for school achievement” in 2019. She is now investigating explanatory factors of gender differences in students' motivation as part of her habilitation at Heidelberg University. Furthermore, she lectures on educational psychology for teacher training students and teaches basic methodology courses at the Institute of Educational Studies. Beyond the university context, she also runs the TALENT SAFARI together with her husband.

References

- Ahrberg, K., Dresler, M., Niedermaier, S., Steiger, A., & Genzel, L. (2012). The interaction between sleep quality and academic performance. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(12), 1618–1622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.008

- Amanvermez, Y., Karyotaki, E., Cuijpers, P., Salemink, E., Spinhoven, P., Struijs, S., & de Wit, L. M. (2021). Feasibility and acceptability of a guided internet-based stress management intervention for university students with high levels of stress: Protocol for an open trial. Internet Interventions, 24, 100369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100369

- Amanvermez, Y., Rahmadiana, M., Karyotaki, E., de Wit, L., Ebert, D. D., Kessler, R. C., & Cuijpers, P. (2023). Stress management interventions for college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology, 30(4), 423–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12342

- Austin, E. J., Saklofske, D. H., & Mastoras, S. M. (2010). Emotional intelligence, coping and exam-related stress in Canadian undergraduate students. Australian Journal of Psychology, 62(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530903312899

- Bewick, B., Koutsopoulou, G., Miles, J., Slaa, E., & Barkham, M. (2010). Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they progress through university. Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216643

- Breedvelt, J. J. F., Amanvermez, Y., Harrer, M., Karyotaki, E., Gilbody, S., Bockting, C. L. H., Cuijpers, P., & Ebert, D. D. (2019). The effects of meditation, yoga, and mindfulness on depression, anxiety, and Stress in Tertiary Education Students: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 193. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00193

- Busch, M. (1990). Die Vorbereitung auf das Erste juristische Staatsexamen – Eine Umfrage unter Freiburger Examensabsolventen [Preparation for the First State Examination in Law – A survey among Freiburg graduates]. Juristische Schulung, 12, 1028–1029.

- Call, D., Miron, L., & Orcutt, H. (2014). Effectiveness of brief mindfulness techniques in reducing symptoms of anxiety and stress. Mindfulness, 5(6), 658–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0218-6

- Campbell, R., Soenens, B., Beyers, W., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2018). University students’ sleep during an exam period: The role of basic psychological needs and stress. Motivation and Emotion, 42(5), 671–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9699-x

- Chrousos, G. P. (2009). Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology, 5(7), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2009.106

- Conley, C. S., Durlak, J. A., & Dickson, D. (2013). An evaluative review of outcome research on universal mental health promotion and prevention programs for higher education students. Journal of American College Health, 61(5), 286–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2013.802237

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Duan, H., Yuan, Y., Zhang, L., Qin, S., Zhang, K., Buchanan, T. W., & Wu, J. (2013). Chronic stress exposure decreases the cortisol awakening response in healthy young men. Stress, 16(6), 630–637. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2013.840579

- Ernst, B. (2018). Weichenstellung im Jurastudium [Setting the course in law studies]. Zeitschrift für Didaktik der Rechtswissenschaft, 5(3), 272–276. https://doi.org/10.5771/2196-7261-2018-3-272

- Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, L. T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089

- Folkman, S. (2008). The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 21(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701740457

- Giglberger, M., Peter, H. L., Henze, G.-I., Kraus, E., Bärtl, C., Konzok, J., Kreuzpointner, L., Kirsch, P., Kudielka, B. M., & Wüst, S. (2023). Neural responses to acute stress predict chronic stress perception in daily life over 13 months. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 19990. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46631-w

- Giglberger, M., Peter, H. L., Kraus, E., Kreuzpointner, L., Zänkert, S., Henze, G.-I., Bärtl, C., Konzok, J., Kirsch, P., Rietschel, M., Kudielka, B. M., & Wüst, S. (2022). Daily life stress and the cortisol awakening response over a 13-months stress period – Findings from the LawSTRESS project. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 141, 105771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105771

- Glöckner, A., Towfigh, E., & Traxler, C. (2013). Development of legal expertise. Instructional Science, 41(6), 989–1007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-013-9266-5

- Halladay, J. E., Dawdy, J. L., McNamara, I. F., Chen, A. J., Vitoroulis, I., McInnes, N., & Munn, C. (2019). Mindfulness for the mental health and well-being of post-secondary students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 10(3), 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0979-z

- Harrer, M., Adam, S. H., Baumeister, H., Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Auerbach, R. P., Kessler, R. C., Bruffaerts, R., Berking, M., & Ebert, D. D. (2018). Internet interventions for mental health in university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatry Research, 28, 1–18.

- Heinrichs, M., Stächele, T., & Domes, G. (2015). Stress und Stressbewältigung [Stress and stress management]. Hogrefe.

- Heublein, U., Hutzsch, C., Kracke, N., & Schneider, C. (2017). Die Ursachen des Studienabbruchs in den Studiengängen des Staatsexamens Jura. Eine Analyse auf Basis einer Befragung der Exmatrikulierten vom Sommersemester 2014. [The reasons for dropping out of law school in the courses of study for the state examination in law. An analysis based on a survey of exmatriculated students from the summer semester 2014.]. Deutsches Zentrum für Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsforschung.

- Holm-Hadulla, R. M., & Hofmann, F.-H. (2007). Lebens- und Studienzufriedenheitsskala [Satisfaction With Life and Studies Scale]. Deutsches Studentenwerk.

- Holm-Hadulla, R. M., Hofmann, F.-H., Sperth, M., & Funke, J. (2009). Psychische Beschwerden und Störungen von Studierenden. Vergleich von Feldstichproben mit Klienten und Patienten einer psychotherapeutischen Beratungsstelle [Psychological complaints and mental disorders of students. Comparison of field study samples with clients and patients of a psychotherapeutic counseling center]. Psychotherapeut, 545, 346–356.

- Howell, A. J., & Passmore, H.-A. (2019). Acceptance and commitment training (ACT) as a positive psychological intervention: A systematic review and initial meta-analysis regarding ACT’s role in well-being promotion among university students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(6), 1995–2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0027-7

- Juster, R. P., McEwen, B. S., & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002

- Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. McGraw-Hill.

- Lazarus, R. S. (2006). Stress and emotion. Springer Publishing Company.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Lobinger, T. (2016). Verbesserungen in der juristischen Examensvorbereitung: Das Heidelberger Modell (HeidelPräp!) [Improvements in legal exam preparation: The Heidelberg Model (HeidelPrep!)]. In J. Kohler, P. Pohlenz, & U. Schmidt (Eds.), Handbuch Qualität in Studium und Lehre (pp. 115–128). DUZ Verlags- und Medienhaus GmbH.

- Lyndon, M. P., Strom, J. M., Alyami, H. M., Yu, T.-C., Wilson, N. C., Singh, P. P., Lemanu, D. P., Yielder, J., & Hill, A. G. (2014). The relationship between academic assessment and psychological distress among medical students: A systematic review. Perspectives on Medical Education, 3(6), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-014-0148-6

- Maydych, V., Claus, M., Dychus, N., Ebel, M., Damaschke, J., Diestel, S., Wolf, O. T., Kleinsorge, T., & Watzl, C. (2017). Impact of chronic and acute academic stress on lymphocyte subsets and monocyte function. PLoS One, 12(11), e0188108. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188108

- McEwen, B. S. (2004). Protection and damage from acute and chronic stress: Allostasis and allostatic overload and relevance to the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1032(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1314.001

- Multrus, F., Majer, S., Bargel, T., & Schmidt, M. (2017). Studiensituation und studentische Orientierungen. 13. Studierendensurvey an Universitäten und Fachhochschulen [Study situation and student orientation. 13th student survey at universities and universities of applied sciences]. BMBF.

- Peters, E. M. J., Müller, Y., Snaga, W., Fliege, H., Reißhauer, A., Schmidt-Rose, T., Max, H., Schweiger, D., Rose, M., & Kruse, J. (2017). Hair and stress: A pilot study of hair and cytokine balance alteration in healthy young women under major exam stress. PLoS One, 12(4), e0175904. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175904

- Rabkow, N., Pukas, L., Sapalidis, A., Ehring, E., Keuch, L., Rehnisch, C., Feußner, O., Klima, I., & Watzke, S. (2020). Facing the truth – A report on the mental health situation of German law students. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 71, 101599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101599

- Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001

- Renshaw, T. L., & Rock, D. K. (2018). Effects of a brief grateful thinking intervention on college students’ mental health. Mental Health & Prevention, 9, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2017.11.003

- Reschke, T., Lobinger, T., & Reschke, K. (2023). The potential of an exam villa as a structural resource during prolonged exam preparation at university. Frontiers in Education, 8, 648. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1130648

- Ribeiro, Í. J. S., Pereira, R., Freire, I. V., de Oliveira, B. G., Casotti, C. A., & Boery, E. N. (2018). Stress and quality of life among university students: A systematic literature review. Health Professions Education, 4(2), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpe.2017.03.002

- Sanders, A., & Dauner-Lieb, B. (2013). Lernlust statt Examensfrust: Strategien und Tipps erfolgreicher Absolventen [Desire to learn instead of exam frustration: Strategies and tips from successful graduates]. Juristische Schulung, 4, 380–384.

- Schmidt, L. I., & Obergfell, J. (2011). Zwangsjacke Bachelor? Stressempfinden und Gesundheit Studierender [Straitjacket bachelor? Perceived stress and health among university students]. VDM.

- Schmidt, L. I., Scheiter, F., Neubauer, A., & Sieverding, M. (2018). Anforderungen, Entscheidungsfreiräume und Stress im Studium: Erste Befunde zu Reliabilität und Validität eines Fragebogens zu strukturellen Belastungen und Ressourcen (StrukStud) in Anlehnung an den Job Content Questionnaire [Demands, Decision Latitude, and Stress Among University Students: Findings on Reliability and Validity of a Questionnaire on Structural Conditions (StrukStud) Based on the Job Content Questionnaire]. Diagnostica, 65(2), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000213

- Schmidt, L. I., Sieverding, M., Scheiter, F., and Obergfell, J. (2015). Predicting and explaining students' stress with the demandcontrol model: Does neuroticism also matter? Educational Psychology, 35, 449–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.857010

- Seidl, M., Limberger, M. F., & Ebner-Priemer, U. W. (2016). Entwicklung und Evaluierung eines Stressbewältigungsprogramms für Studierende im Hochschulsetting [Development and Evaluation of a Stress Management Program for Students]. Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie, 24(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1026/0943-8149/a000154

- Sheehy, R., & Horan, J. J. (2004). Effects of stress inoculation training for 1st-year law students. International Journal of Stress Management, 11(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.11.1.41

- Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and Validation of an Internationally Reliable Short-Form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106297301

- Towfigh, E. V., Traxler, C., & Glöckner, A. (2018). Geschlechts- und Herkunftseffekte bei der Benotung juristischer Staatsprüfungen [Gender and origin effects in the grading of legal state examinations]. Zeitschrift für Didaktik der Rechtswissenschaft, 5(2), 115–142. https://doi.org/10.5771/2196-7261-2018-2-115

- Van Daele, T., Hermans, D., Van Audenhove, C., & Van Den Bergh, O. (2012). Stress reduction through psychoeducation: A meta-analytic review. Health Education & Behavior, 39(4), 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198111419202

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Winzer, R., Lindberg, L., Guldbrandsson, K., & Sidorchuk, A. (2018). Effects of mental health interventions for students in higher education are sustainable over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PeerJ. 6, e4598. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4598

- Xiang, Z., Tan, S., Kang, Q., Zhang, B., & Zhu, L. (2019). Longitudinal effects of examination stress on psychological well-being and a possible mediating role of self-esteem in Chinese High School Students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(1), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9948-9

- Yusufov, M., Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, J., Grey, N. E., Moyer, A., & Lobel, M. (2019). Meta-analytic evaluation of stress reduction interventions for undergraduate and graduate students. International Journal of Stress Management, 26(2), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000099

- Zunhammer, M., Eberle, H., Eichhammer, P., & Busch, V. (2013). Somatic Symptoms Evoked by Exam Stress in University Students: The Role of Alexithymia, Neuroticism, Anxiety and Depression. PLoS One, 8(12), e84911. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084911