Abstract

In the present study we dig into those post-confinement socioemotional factors that affect the academic competencies of students to the Science Faculty of the Universidad de Valparaíso. Learning conditions of these students in the previous years of their university life were completely online, interrupting normal socialization, at a key age of their neurodevelopment. A self-perception survey was applied to identify those factors that currently affect the students’ socioemotional processes with special attention on those related with academic performance. This is a quantitative study with a correlational descriptive scope. The study population consisted of 150 individuals admitted in 2021 and 2022. For the analysis of the results obtained from the survey on a Likert scale, associations were made according to the results of the Pearson correlation matrix. To the open questions, a NLP (Natural Language Processing) analysis was implemented, which consisted of counting words. Following the results of the survey, changes in teaching and learning strategies were implemented, which allowed improving the socioemotional gaps detected among students, improving their academic performance and perception of the contents addressed by the academics of the different subjects. Results drove us to the design of opportune academic strategies which tried to facilitate the transit to face-to-face learning and university life, safeguarding the students’ proper training process.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Quarantines implemented during the pandemic forced the adoption of an online teaching system. According to UNESCO (Citation2020), in April 2020 students in virtual classes exceeded one billion individuals (82% of global student population in more than 150 countries). In Chile, the social outbreak of October 2019, also caused the extension of the academic year at the beginning of 2020 in virtual or mixed mode (Navarro et al., Citation2020). Most educational centers returned to face-to-face teaching only in March 2022, which meant that students were out of the classroom for more than two years.

The Ministry of Education took measures to reduce the impact of the confinement, mainly at the school level, and a general action plan was formulated for higher education institutions (Mineduc, Citation2020), which covered in a particular way the needs of their students and teachers (AUR, Citation2020). These actions attempted to mitigate the possible effects on learning. However, the consequences of the confinement are still not dimensioned. Students in confinement were exposed to a considerable risk of developing depressive symptoms or experiencing exacerbation of pre-existing ones (Nearchou et al., Citation2020).

International studies confirmed the negative impact of confinement, indicating that it would be relatively long-lasting (Wang et al., Citation2020). The work of Van de Velde et al. (Citation2021) analyzed cross-national variation in depressive symptoms in university students from 125 institutions from 26 countries. High levels of depressive symptoms were observed, with higher incidence in women and students with lower socioeconomic resources in the USA, Spain, South Africa, and Turkey; the lowest levels were observed in Nordic countries and France. Researchers noted that reduced social contact, increased economic insecurity and academic stress were factors explaining depressive symptoms in students.

Similar results have been reported by Cao et al. (Citation2020). Early in the pandemic they surveyed more than 7,000 students in China, observed that 0.9% suffered from severe anxiety, 2.7% from moderate anxiety and 21.3% from mild anxiety, showing positive correlation with delays in academic activities. Wang and Zhao (Citation2020), applied the Self-Rated Anxiety Scale (SAS), observing a 30% increase in the mean score compared to the national average. Ma et al. (Citation2022) measured in Chinese University students the association of mental health problems and suicidal thoughts during the pandemic outbreak, which increased from the early periods (7.6%) to the late ones (10.0%). During the first period of the pandemic in the USA, they found that 25% of university respondents thought about suicide (Czeisler et al., Citation2020).

The Chilean study conducted by Mac-Ginty et al. (Citation2021), surveyed 2,411 university students, where 6 out of 10 students claimed to have suffered at least one adverse event in their family nucleus, and 3 out of 4 students reported that their mood was worse or much worse compared to the pre-pandemic context. In another study (Morán-Kneer et al., Citation2021), 1,002 students from different universities were surveyed on-line in 2020, where 74% presented moderate or severe depressive symptomatology. In relation to academics, Internet access is an important stressor. Forty percent of the population had poor or bad connection, 42% claimed being unfavored by the remote study modality, and 69% expressed their fear of continuing their studies due to economic difficulties. Carvacho et al. (Citation2021) proposed an increase in depressive symptomatology, which could be caused by the interruption of studies, social isolation, university experience that does not meet expectations, and by the cumulative effect of the social outburst of 2019.

On the other hand, there is sufficient scientific information on the neurobiological characteristics of the subject in question. In Chile, university entrance is on average at 18–19 years of age, an age that according to the (Sawyer et al., Citation2012), would be at the limit of adolescence (10 to 19 years). However, from neurobiology, adolescence is until the age of 25 years or more. At this stage, important changes occur in the central nervous system that affect precise affective regulations, as well as the maturity of executive functions (Caballero et al., Citation2016; Guyer et al., Citation2016; Murty et al., Citation2016).

Recent research on adolescent affective behavior (De Figueiredo et al., Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2020), demonstrate how neurobiological changes influence affective behavior, and how these influences are modulated by external environmental factors. These changes are associated with the maturation of regions involved in the control of motivation, emotion, and cognition. It is proposed that the prolonged development of the prefrontal cortex during adolescence (Caballero et al., Citation2016; Luna et al., Citation2004; Suzuki et al., Citation2005) underlies the maturation of cognitive functions (working memory, development of attention, planning, inhibition of automatic responses) and affective regulation, both of which are substantial for learning processes.

Emotion regulation can target the emotion itself (e.g. using relaxation techniques), the control and value appraisals that underlie the emotions (e.g. cognitive restructuring), the academic competences that determine the agency of students (e.g. development of learning skills) and the environment within educational institutions, including classroom instruction (e.g. design of academic environments or curricular adjustments).

According to Pekrun et al. (Citation2007) control-value theory of achievement emotions involves appraisals of controllability on one hand and of value on the other. Individuals would experience specific achievement emotions when they feel in control of academic activities and outcomes that are subjectively important to them. It also suggests that the assessment and the level of perceived control of academic activity triggers different coping strategies. In general, it is assumed that achievement emotions have influence on cognitive resources, on motivation, on the use of metacognitive strategies, on the learning process and on performance in general.

While positive achievement emotions will exert adaptive effects on learning and performance, on the other hand negative or unpleasant emotions tend to exert non-adaptive effects (Artino et al., Citation2012). The above is relevant for the design of “emotionally solid” learning environments (Astleitner, Citation2000; Pekrun et al., Citation2007). For example, if a student expresses interest in a learning material and feels able to handle it, then he or she will enjoy studying. If there is controllability, but the activity is valued negatively, it is postulated that frustration is experienced. Examples are activities that can be performed but are subjectively unpleasant because they require a lot of mental or physical effort. Conversely, if the activity is positively valued, but there is insufficient control and the obstacles inherent to the activity cannot be successfully managed, disinterest will be experienced.

According to what has been described, the socioemotional alterations of students during confinement could currently manifest feelings of overwhelm and overload, mainly in the first years. In this research we sought to investigate the impact of these negative valence emotions. For this purpose, a socioemotional self-perception survey was applied to the 2021 and 2022 cohorts. The results allowed us to identify the possible causes that prevent a healthy transition to university life.

Methodology

This is a quantitative study with a correlational descriptive scope. A validated instrument was applied to collect data on socio-emotional and learning factors to first-year university students. Based on the analysis of the data, the socio-emotional aspects of the students and their correlation with emotions of negative and positive valence are described, with the aim of identifying factors incident to their learning.

General objective

To collect and to analyze socio-emotional self-perception data of students admitted in 2021 and 2022, to identify incident factors in learning which may allow us to generate curricular adjustments that may facilitate the teaching/learning process in face-to-face teaching.

Specific objectives

To collect socio-emotional self-perception data of students admitted in 2021 and 2022 with a specifically designed survey.

To analyze data collected with the designed survey, by Pearson correlation coefficient.

To identify the most incident factors in the learning process.

To generate curricular adjustments which facilitate the teaching/learning process in face-to-face teaching.

Sample characterization

The population comprised 150 individuals, of which 116 responded to the survey (66.7% were admitted in 2021 and 33.3% were admitted in 2022). The following table () shows sociodemographic characteristics of the population, related to incident factors in depressive symptoms observed in previous research. In the economic profile, 53% of those surveyed have a gratuity benefit and 81% of them come from a municipal or private subsidized institution. In the demographic profile, 26% of the students come from distant regions, and 18% belong to some ethnic group. It is estimated that 75% completed – at least – one year of schooling with virtual or remote teaching.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the students.

Instrument design

In educational psychology there are some theoretical approaches that allow emotions to be operationalized during academic or learning activities. It is argued that achievement emotions (Pekrun, Citation2006; Pekrun et al., Citation2007) remain intrinsically linked to achievement activities (such as studying) or achievement results (success or failure), triggering anxiety, pride or shame. However, we know that not all emotions triggered in academic settings are related to achievement. Pekrun and Stephens (Citation2012) and Muis et al. (Citation2021) also distinguished thematic emotions, social emotions, and epistemic emotions. Where thematic emotions relate to the learning content, while social emotions focus on relationships with others in the learning context. Finally, epistemic emotions are those that are related to the perceived quality of knowledge and information processing (Muis et al., Citation2015, Citation2021; Pekrun & Stephens, Citation2012; Pekrun et al., Citation2016). The previous theoretical approach described by the authors was considered both for the construction of the instrument, as well as for its subsequent analysis of previous and subsequent results.

The survey was designed by professors from the Faculty of Sciences of the Universidad de Valparaíso. It includes 2 parts: the first one collects information on socio-emotional perception and the second one, measures the effect of these socio-emotional factors in the academic field. It consisted of 31 items on a Likert scale, plus 3 open questions. The scale was as follows: (1) totally disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) agree, (5) totally agree. In the open questions, elements related to socio-emotional perception that directly impact cognitive processes were included, such as neurobiological and self-regulation aspects which were not considered in the 31 previous items.

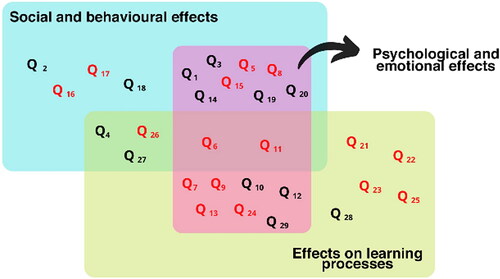

Items are identified with the symbol Qi, with i = 1,…,34, used to facilitate visualization by dimensions:

lists the effects that we searched to quantify, and to which aspects each item is related to.

Instrument validation

The first validation step consisted in applying Cronbach’s Alpha to estimate the reliability of the instrument (Aiken, Citation2003). Internal consistency was evaluated from the covariation between the items. The test suggested eliminating questions to improve the consistency of the instrument. Q1, Q14, Q17, Q18, Q20, Q30 and Q31 were eliminated since they corresponded to questions with a certain degree of subjectivity and did not compromise the results of the study.

The second step was an exploratory analysis of the correlation matrix to identify possible redundant or contradictory questions and, at the same time, investigate possible interactions – positive or negative – between the items. Correlations were obtained that hint at duplicity regarding the dimensionality of certain questions, and natural correlations such as the positive correlation between Q10(I feel motivated) and Q12(I feel confident), and the negative correlation between the degree of motivation and the evaluation of class participation, which intuitively showed that the answers were conscious and sincere.

Among the most significant correlations:

Positive of 0.6 between degree of overwhelm versus feeling of having little time to assimilate the contents addressed (Q9 and Q22).

Positive of 0.7 between degree of frustration and degree of overwhelm (Q9 and Q13).

Positive of 0.65 between valuation of leisure time during confinement, time to discover new interests and rest (Q2, Q3 and Q4).

Positive between feelings of being scared and difficulties to interact with their peers.

Positive, moderately significant, being demotivated by virtual classes and having little interaction with peers.

A factorial analysis was implemented, where it was tested whether the dimensions detected were consistent with those proposed in the formalization of the instrument. The initial objective of the construction of the survey was to quantify the assessment of virtual learning during confinement, the positive and negative aspects of confinement in terms of social aspects, the assessment of the return to face-to-face teaching, the negative aspects of the return to face-to-face teaching and the current emotional state. In the factorial solution (), the following grouping is identified:

Table 2. Grouping according to factorial solution.

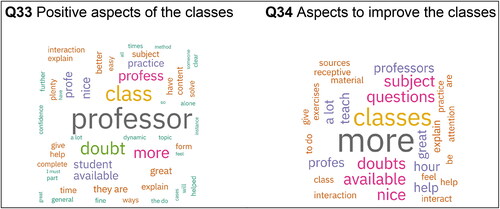

For open questions, a simple NLP (Natural Language Processing) analysis was implemented, which consisted of counting words, identifying the most repeated ones and the correlations between them.

Application of instruments and informed consent

The survey was anonymous and was answered through a link. This was applied in two moments of the semester (E1 and E2 from now on); E1 at week 8 and E2 at week 16 out of 18 weeks. Before the survey application, students were convened to an informative meeting managed by researchers. In this meeting study objectives were explained to the students, emphasizing their free participation. The required Informed consent document for the survey implementation was read and explained with the idea of solving any doubts directly. To assure the confidentiality of the information given to each participant and to avoid any feeling that their answers may be negatively evaluated, it was explained to students that both their personal data and their answers would be confidential, and their use would be exclusively reserved for the accomplishment of the objectives of this study. Students were given a 5 business days’ time to answer the questionnaire from their cell phones through a link.

To ensure the validity of the responses, participants could only answer the questions through their institutional email. The responses were collected in an excel spreadsheet administered only by the study group for later analysis.

For the analysis of the results obtained from the survey on a Likert scale, associations were made according to the results of the Pearson correlation matrix and the factor analysis, which allows the response Qi to be related to the response Qj. With this information, a descriptive analysis of the results obtained in both surveys was carried out. To the open questions, a NLP (Natural Language Processing) analysis was implemented, which consisted of counting words, identifying the most repeated ones and the correlations between them.

Results

Perceptions of confinement

The overall results revealed both positive and negative aspects of the lockdown. Of the positives, 51.8% declared having had more time for leisure versus 28.4%; more time to rest, 50.8% versus 25%; and to discover new interests 55.1% versus 24.1% ().

Table 3. Self-perception of leisure time in confinement.

Regarding the negative perception, demotivation was mainly evidenced by the remote classes (75.8%). This could be explained by interaction with their peers (79.3% declare low interaction).

Some factors () that could influence the negative perception are related to family dynamics; 45.7% declare frequent conflicts related to domestic or work responsibilities, 38% affirm that they have assumed houseworks, which is consistent with Mac-Ginty et al. (Citation2021) observed.

Table 5. Self-perception of negative family aspects of confinement.

The negative perception of some experiences in confinement influence the motivation of students in the face of academic responsibilities. This coincides with what is described in the theory of achievement emotions (Pekrun et al., Citation2007), where it is proposed that positive or negative emotions, which are not related to an ongoing achievement activity, distract attention from the activity, reducing the cognitive resources available for the task and impairing performance.

The elements investigated in factors 2 and 4 () refer to emotions related to motivation and self-efficacy. Motivation is described in the literature as an awareness and willingness to act in a certain way based on an idea or state of mind, while self-efficacy is defined as a self-reflective belief in the ability to succeed (Code, Citation2020). These act as determinants in the choices of individuals, the effort they expend, the perseverance in the face of difficulties, in addition to the thought patterns and emotional reactions they experience (Code, Citation2020).

Emotional self-perception in face-to-face teaching

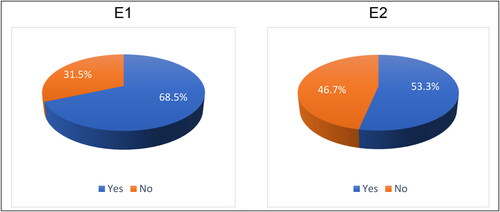

In the first survey, 68.5% stated that they felt overwhelmed (). The results showed that the sensation is related to academic and emotional aspects.

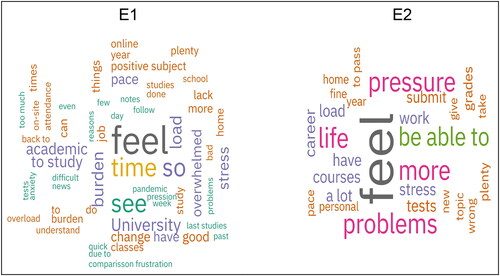

Frequency of the tokens (words) that justify the feeling of being overwhelmed, () where I feel is more frequent in E1 and E2.

In E1 the words can be identified: pandemic, pressure, problems, stress, burden-overload, anxiety, overwhelm, frustration, university; It follows that the reasons for the overwhelm are focused on the academic and emotional aspects.

The other most repeated words in E1 were time and university. After an exhaustive analysis, they showed a higher correlation with the words transport, missing, trip, journey, fear, personal, administration, performance, balance, leisure and invest.

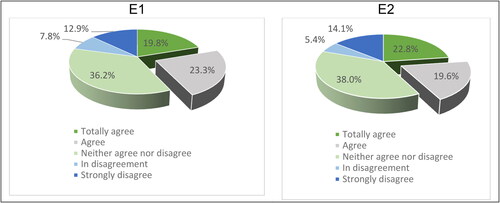

The students expressed a lack of time for their academic performance, due to the academic load and transfers to the university. Some reported having difficulty resuming the rhythm of face-to-face, which is consistent with the assessment of leisure time in confinement (), added to the perception of having little knowledge. These results are related to emotional and academic aspects, 48.3% feel identified with the feeling of fright and 54.3% with frustration (). However, 56% claim to be motivated () which suggests a positive assessment of the return to face-to-face.

Table 6. Self-perception of emotional aspects.

In academics, 44.8% consider the class schedule extensive and overloaded (); around 60% affirm that the contents are treated with little time to be able to assimilate them. The foregoing is consistent with the perception of lack of time (61.2%) of previous knowledge (43.1%) to meet academic requirements, and insecurity in the first evaluations due to face-to-face (53.5%).

Table 7. Self-perception of academic performance in face-to-face teaching.

This is complemented by the analysis of open questions related to the positive (Q33) and negative aspects of the classes (Q34) (). As for the positive aspects, the willingness of teachers and support in cognitive processes stand out, valuing student/teacher interaction, highlighting the importance of face-to-face attendance. Among the aspects to improve perception of overload, lack of time and previous knowledge to face learning.

The open questions showed that student-teacher interaction has been important in face-to-face (). Teachers were attentive and receptive 81.9%, which meant an increase in confidence. The neutral position of 25.9% of those surveyed regarding this topic stands out, which suggests a process of adaptation to face-to-face.

Table 8. Self-perception of student-teacher interaction.

Actions implemented from E1 results

The results of E1 were socialized in the academic faculty, in which, among other authorities, teachers of the first and second year from general education subjects took part. In this instance, it was agreed to apply pedagogical strategies to reduce the burden of students, the main measures implemented are:

Reduction in the class period: from 90 continuous minutes to 40 minutes, considering a 10-minute break between periods.

Distribution of evaluations: set a maximum of 2 evaluations per week.

Change of class methodology: leave a 1.5-hour session for workshop modality.

Results obtained in E2

The quantitative information from E2 shows that the measures implemented after the first intervention were positive. There was a decrease in the feeling of being overwhelmed (15%) (); unlike E1, the overwhelm is attributed to problems of a personal nature rather than of an academic nature (). The most repeated words in E2, in addition to I feel, were more, life, problems, pressure; although the frequency of these is lower (40% less) than the results of the first application. Compared to E1, in E2 there is a 60% decrease in words related to academics. The highest correlation observed (greater than 0.6) between the tokens are: problems related to home, life with lead, family pressure, more with personal, power with expectations, comply, duties, perform and address.

Class breaks decrease the perception of long and overloaded hours (from 44.8% to 32.7%) (). Teachers carried out more exercise workshops, which impacted the perception of lack of time to "learn" content. The percentage of students who fully agree that there is insufficient time to assimilate the contents decreases by 10% (see Q22), while those who fully agree with the lack of time to meet the academic requirement decreases by 9% (see Q23). A smaller percentage of students increase their self-confidence regarding their academic competencies (4% decrease in Q25). However, an increase (7%) of students who are in an intermediate situation stands out. This could be due to the learning processes of each student. It is expected that as the actions continue to be implemented, the percentage decrease will be greater.

Table 4. Self-perception of negative aspects of confinement.

The feeling of fright dropped slightly (), however, frustration decreased significantly from 54.3% to 29.4% in the second application. The percentage of students who say they are motivated increases from 56% to 60.8% (). These results are somehow related to the moment in which E2 was applied, which was in the period of final evaluations, which may mean an increase in fear. Despite this, the aspects evaluated in Q10, Q11 and Q13 suggest that the student evaluated the control of the academic situation, valuing environmental influences and adapting to the regulation of personal processes.

Social interaction in face-to-face

It is important to analyze the current interaction between peers, possibly conditioned by confinement. In E1, 18.1% of the students say they interact little, decreasing to 13% in E2 (). What is relevant is the decrease (5%) of those who preferred to be alone.

Regarding communication difficulties, the results are low in E1 (), and lower in E2. According to the data, the preference of not interacting could be caused mainly by communication difficulties and should not be based on the perception towards the rest (consistent with Q19 in both surveys). This self-perception may be due because since in confinement they did not participate in classes (discussions, questions, opinions) and possibly, the interaction was not intentional in virtual classes. These results are consistent with those obtained in E2, 80% consider that teachers have been receptive, increasing student-teacher interaction from 43.9% to 52.2% ().

Table 9. Self-perception of the interaction between peers.

Discussion

The control-value theory (Pekrun et al., Citation2007) suggests that an increase in the sense of control over the academic environment favors a progressive mobilization of one’s own responsibility. This promoted values of commitment and academic performance (Pekrun, Citation2006) by increasing the perception of controllability and giving place to internal locus explanations about the causes of performance, thus avoiding blaming academic overload. The same happens in relation to the change in class methodology, which considered favoring work in workshop mode to promote collaborative work, since social interaction is also related to the development of self-regulated skills of learning (Volet et al., Citation2009). For example, the elements contained in factor 1 account for characteristics directly related to self-regulation, defined as the monitoring, regulation and control of cognition, motivation and behavior, guided and limited by its objectives in relation to the contextual characteristics of the environment of learning (Code, Citation2020). Human agency theory, as described by Bandura (Citation2006; Code, Citation2020), provides a conceptualization of how behavioral, cognitive, and other personal factors, as well as environmental influences, interact to provide a more holistic and contextual view of learning. The theory also implies that emotions can be regulated and changed by addressing any of the elements involved in these cyclical feedback processes.

With the pedagogical measures, the circumstances that define controllability and the values associated with the academic challenge were modified, seeking to promote a greater perception of student control in two types of causal expectations (Pekrun et al., Citation2007): (1) Student perception that he/she could invest effort in learning (control-action) and (2) Perception related to the fact that, thanks to his/her effort, he/she would obtain a good grade (action-result). Actions such as the reduction of the class period and the better distribution of evaluations modified the perception of lack of time to "learn" and showed a slight increase in the students’ confidence regarding their academic skills. Classes based on collaborative work also contributed to these changes, since interaction is related to the development of self-regulated learning skills (Volet et al., Citation2009).

In this line, and from the control-value theory (Pekrun et al., Citation2007), a greater sense of control over the academic environment was promoted to favor the student’s responsibility towards educational processes, promoting both commitment and academic performance (Pekrun, Citation2006), understanding that the causes of performance are found in its internal locus and not necessarily in external factors such as academic overload.

In the study we observed that the emotions of academic achievement can be regulated by modifying the socioenvironmental variables. We must consider that, during the long time in the classroom, social relationships are created, and the achievement of life goals depends on both the individual and collective action of educational institutions. Although the regulation of personal processes is inherent to the individual effort, the individual does not operate in isolation; it requires the mediation of others and a sociocultural environment to develop, which allows it to operate in an objective-directed manner. Bearing this in mind, the ethical relationship implied by the attitude of welcome and commitment to the student is essential in the learning process.

Conclusions

In the study, students were asked about their socio-emotional self-perception, in relation with emotions of positive and negative valence, such as burden (Q9), motivation (Q10), scare (Q11) and frustration (Q13). They were also asked about their perception of learning environment characteristics such as extension of hours (Q21), time to address contents (Q22), previous knowledges (Q25) and receptiveness of teachers to their questions (Q27). All this was carried out through a mixed socio-emotional self-perception survey (31 items in Likert scale and 3 open questions) applied twice during the development of the academic semester. Data were analyzed using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results from the first survey were analyzed first, to identify those factors incident to student learning on their in person return to the University after the confinement caused by Covid-19. Based on the results from the first survey pedagogical measures were implemented to reduce the identified factors, and then, in the second application of the survey, evaluate whether the incident factors decreased after the implementation of the pedagogical actions. In this way, we sought to promote a greater perception of control of the learning process by the students, based on the consideration of the results of the initial self-perception survey to mobilize changes that considered the needs of the students and thus to favor their learning process.

The analysis of the results of the second application of the survey shows that the measures applied after the first survey had a positive effect, observing a decrease in the perception of negatively valence emotions, and an increase in the positive perception of environmental variables. This allows us to conclude that the application of this type of instrument generates information to adopt pedagogical measures that influence the socio-emotional self-perception of students. Proof of this is the decrease in the appearance of academic elements associated with negatively valence emotions in the development questions.

In relation to the reduction in the class period and in the distribution of evaluations, its impact is observed in the decrease in the perception of lack of time to “learn” and the slight increase in the students’ security regarding their own academic competencies.

Recommendations

What is stated in this article corresponds to a descriptive comparison between two moments during the development of the academic semester of first-year university students. A systematic evaluation of impacts requires analysis of data over longer periods. Based on this point, we suggest that, in future research, we will also consider investigating the socio-emotional perception of teachers, who oversee mediating the training processes, generating educational contexts that allow a positive experience in the classroom. Furthermore, considering that what is presented in this article corresponds to a descriptive comparison between two moments during the development of the academic semester of first-year university students we believe that a systematic evaluation of the impacts of pedagogical measures requires data analysis over longer periods.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pamela Herrera Albornoz

Pamela Herrera Albornoz is assistant professor at the Phisiology Institute of the Science Faculty of the Universidad de Valparaíso. Degree in kinesiology from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Master in science mention neuroscience from the Universidad de Valparaíso. Director of the bachelor’s degree program in sciences with a mention in Biology or Chemistry. Undergraduate coordinator of the Science faculty of the Universidad de Valparaíso.

Cristian Contreras Cáceres

Cristian Contreras Cáceres is psychologist working at the APPA of the Universidad de Valparaíso. Degree in Psychology and Master in Cognitive Development with mention in Dynamic Assessment. Currently working in the development of self-regulation of learning with students entering university and in the development of Early Warning Systems for the prediction of the risk of dropout of students in Higher Education.

Kerlyns Martínez Rodríguez

Kerlyns Martínez Rodríguez, PhD, is assistant professor at IDEUV (2021-) and director of the master’s program in Statistics. Degree in Mathematics from the Universidad Central de Venezuela, 2014, and PhD in Mathematics from the consortium between UV, UTFSM and PUCV, 2019. She specializes in stochastic processes and mathematical modeling with applications in different areas of science.

Álvaro Bustos Rubilar

Álvaro Bustos Rubilar, PhD, is academic at the Mathematics Institute of the Universidad de Valparaíso. Degree in Mathematics and Master and PhD in Sciences in the specialty of educational mathematics from Cinvestav-IPN, México. His research lines are classroom proof processes, geometric thinking and use of technologies in the teaching of mathematics.

Marcela Venegas Hartung

Marcela Venegas Hartung is professional at the Science Faculty of the Universidad de Valparaíso. Degree in Journalism and Graduate in History and Social sciences from the Universidad Adolfo Ibañez. Postgraduate in strategic communication and Diploma in Cultural management from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso. Master © in teaching for Higher Education from the Universidad Andrés Bello.

Iván González González

Iván González González, PhD, academic at the Institute of Physics and Astronomy of the Universidad de Valparaíso. Degree in Physics and Sciences Education from the Universidad de Playa Ancha, Chile, and PhD in Physics, specializing in high-energy physics, from the Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María in Chile. His specific research areas include perturbative quantum field theory, Feynman diagram calculations, and the development of advanced integration techniques.

References

- Aiken, L. R. (2003). Tests psicológicos y evaluación. Pearson Educación.

- Artino, A., Holmboe, E., & Durning, S. (2012). Control-value theory: Using achievement emotions to improve understanding of motivation, learning, and performance in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 64. Medical Teacher, 34(3), e148–60. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2012.651515

- Astleitner, H. (2000). Designing emotionally sound instruction: The FEASP-approach. Instructional Science, 28(3), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003893915778

- AUR. (2020). Universidades Regionales: Aportes y Experiencias ante la Situación Generada por la Pandemia de Coronavirus (COVID-19). http://www.auregionales.cl/documentos-pdf/2020/INFORME_AUR_27may_2020.pdf

- Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

- Caballero, A., Granberg, R., & Tseng, K. (2016). Mechanisms contributing to prefrontal cortex maturation during adolescence. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.013

- Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

- Carvacho, R., Morán-Kneer, J., Miranda-Castillo, C., Fernández-Fernández, V., Mora, B., Moya, Y., Pinilla, V., Toro, I., & Valdivia, C. (2021). Efectos del confinamiento por COVID-19 en la salud mental de estudiantes de educación superior en Chile. Revista Medica de Chile, 149(3), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0034-98872021000300339

- Code, J. (2020). Agency for learning: Intention, motivation, self-efficacy and self-regulation. Frontiers in Education, 5(19). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00019

- Czeisler, M., Lane, R., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E., Barger, L., Czeisler, C., Howard, M., & Rajaratnam, S. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

- De Figueiredo, C., Sandre, P., Portugal, L., Mázala-de-Oliveira, T., da Silva, C., Raony, Í., Ferreira, E., Giestal-de-Araujo, E., Dos Santos, A., & Bomfim, P. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 106, 110171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171

- Guyer, A. E., Silk, J. S., & Nelson, E. E. (2016). The neurobiology of the emotional adolescent: From the inside out. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.037

- Luna, B., Garver, K. E., Urban, T. A., Lazar, N. A., & Sweeney, J. A. (2004). Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Development, 75(5), 1357–1372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00745.x

- Ma, Z., Wang, D., Zhao, J., Zhu, Y., Zhang, Y., Chen, Z., Jiang, J., Pan, Y., Yang, Z., Zhu, Z., Liu, X., & Fan, F. (2022). Longitudinal associations between multiple mental health problems and suicidal ideation among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 311, 425–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.093

- Mac-Ginty, S., Jiménez-Molina, A., & Martíne, V. (2021). Impacto de la pandemia por COVID-19 en la salud mental de estudiantes universitarios en Chile. Revista Chilena de Psiquiatría y Neurología de la Infancia y de la Adolescencia, 32(1), 23–37. https://www.sopnia.com/noticias/revistas/vol-no32n1/

- Mineduc. (2020). Plan de acción para Instituciones de Educación Superior. https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/14673

- Morán-Kneer, J., Moya, Y., Cárcamo, D., Cuevas, M., Loayza, A., Silva, M., Gutiérrez, C., Bastías, G., Godoy, I., Jofré, C., Delgado, M., Miranda-Castillo, C., & Carvacho, R. (2021). Encuesta de caracterización de estudiantes chilenos de educación superior durante la pandemia por Covid-19: Aspectos académicos, relacionales y de salud mental. http://midap.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Ues-Covid.pdf

- Muis, K., Psaradellis, C., Chevrier, M., Di Leo, I., & Lajoie, S. (2015). Learning by preparing to teach: Fostering self-regulatory processes and achievement during complex mathematics problem solving. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 1–19.

- Muis, R., Chevrier, M., Denton, C., & Losenno, K. (2021). Epistemic emotions and epistemic cognition predict critical thinking about socio-scientific issues. Frontiers in Education, 6, 669908. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.669908

- Murty, V. P., Calabro, F., & Luna, B. (2016). The role of experience in adolescent cognitive development: Integration of executive, memory, and mesolimbic systems. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.034

- Navarro, L., Gonzáles, L., & Espinoza, O. (2020). El sector educación bajo el estallido social y la pandemia. Barómetro de Política y Equidad, 17, 177–221. https://barometro.sitiosur.cl/barometros/chile-en-cuarentena-causas-y-efectos-de-la-crisis-politica-y-social

- Nearchou, F., Flinn, C., Niland, R., Subramaniam, S., & Hennessy, E. (2020). Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes in children and adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228479

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

- Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. (2012). Academic emotions. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, S. Graham, J. M. Royer, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook: Individual differences and cultural and contextual factors (Vol. 2, pp. 3–31). American Psychological Association.

- Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. (2007). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: An integrative approach to emotions in education. In En Schutz, P & Pekrun, R (Eds.), Emotions in education (pp. 13–36). Academic Press.

- Pekrun, R., Vogl, E., Muis, K., & Sinatra, G. (2016). Measuring emotions during epistemic activities: the epistemically-related emotion scales. Cognition & Emotion, 31(6), 1268–1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1204989

- Sawyer, S., Afifi, R., Bearinger, L., Blakemore, S., Dick, B., Ezeh, A., & Patton, G. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet, 379, 1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60531-5

- Singh, S., Roy, D., Sinha, K., Parveen, S., Sharma, G., & Joshi, G. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429

- Suzuki, M., Hagino, H., Nohara, S., Zhou, S. Y., Kawasaki, Y., Takahashi, T., Matsui, M., Seto, H., Ono, T., & Kurachi, M. (2005). Male-specific volume expansion of the human hippocampus during adolescence. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991), 15(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhh121

- UNESCO. (2020). Covid-19 impact on education. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

- Van de Velde, S., Buffel, V., van der Heijde, C., Çoksan, S., Bracke, P., Abel, T., Busse, H., Zeeb, H., Rabiee-Khan, F., Stathopoulou, T., Van Hal, G., Ladner, J., Tavolacci, M., Tholen, R., & Wouters, E, C19 ISWS Consortium. (2021). Depressive symptoms in higher education students during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: An examination of the association with various social risk factors across multiple high-and middle-income countries. SSM – Population Health, 16, 100936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100936

- Volet, S., Vauras, M., & Salonen, P. (2009). Self- and social regulation in learning contexts: An integrative perspective. Educational Psychologist, 44(4), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903213584

- Wang, C., & Zhao, H. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety in Chinese university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01168

- Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., McIntyre, R., Choo, F., Tran, B., Ho, R., Sharma, V., & Ho, C. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028