Abstract

During the last decade strengthening of the students’ entrepreneurial intention to start technology businesses has been a relevant objective for both business schools and engineering schools in Latin America. This research compares the entrepreneurial intention of business administration and engineering and technology students to start emerging technology businesses after the COVID-19 pandemic, evaluating whether students’ personality traits are related to their entrepreneurial intention toward these businesses. A comparison of central tendency, Spearman correlations and the Sidak test were conducted to analyzing the responses of 383 business administration and 161 engineering and technology students enrolled in universities of Chile and Ecuador, to an online self-reporting questionnaire. The results have supported a higher entrepreneurial intention of business administration students toward businesses related to e-commerce services, in contrast, engineering and technology students have showed a higher intention to start businesses associated with IT and telecommunications, health technologies and distance education. The findings also suggest that correlations between personality traits and the intention to create these technology ventures vary by area of study, being higher in entrepreneurial topics less close or known by students according to the themes seen in class. The evidence obtained in this study are relevant to improving the formation of technological entrepreneurs in Latin American universities because suggest that it is necessary to consider careers journeys and personality differences to design entrepreneurial training programs.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

After the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic the consumption and sale of products has shown an abrupt transformation (Ewe & Ho, Citation2022; Jiang & Stylos, Citation2021). The citizens of Latin America have also changed their spending patterns, their means of payment, their purchasing channels and their use of new technologies. Moreover, these changes have intensively increased the demand for digital services that enable remote communication, data and information security, online purchases and remote work. Thus, it has become crucial for Latin American universities to encourage student’s entrepreneurship related to this new trend, particularly, to strengthen students’ interest to create technology ventures. Among Latin American students, business administration and engineering and technology students are particularly relevant because their curriculum are linked with the creation of technological solutions to solve people’s problems (Glen et al., Citation2014; Lehmann et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, among the emerging technology businesses, the digitalization of banking and finance, IT and telecommunications, e-commerce services, technological services for health, and distance education have been recognized as important venture areas that are being currently developed (Rivas, Citation2021).

Although the strengthening of the students’ entrepreneurial spirit associated with new technology businesses is a responsibility of several Latin American universities, the achievement of this objective may be different among degree programs according to the disciplines learned by their student which are associated with topics in subjects, in this sense, business administration majors tend to incorporate more courses about entrepreneurship and more recently the need to include more entrepreneurial formation for engineering and technology students has been recognized (Asimakopoulos et al., 2021; Baruah & Mao, Citation2021). Moreover, it is also relevant to recognize that the individual differences of students lead them to a greater or lesser propensity toward these ventures; that is, in a group of students enrolled in the same career, according to their personal characteristics, some of them will manifest a greater or lesser intention to start technology businesses. These personal differences can be related in an important way to personality traits that represent tendencies of thoughts, feelings and behaviors. In this sense, personality, defined as an integrative combination or configuration of all cognitive, affective, conative, and physical qualities (Roback, Citation1931), has been widely used as a theoretical framework that allows understanding and predicting human attitudes and behaviors in areas such as product consumption (Machado-Oliveira et al., Citation2020), job performance (He et al., Citation2019) and also participation in business creation (Alshebami & Seraj, Citation2022).

Currently, little has been studied about differences, between business administration and engineering and technology students, regarding their entrepreneurial intention to create new technology businesses, this knowledge gap is recognized both in other continents and in Latin America. Previous studies have asked students enrolled in various careers and countries without directly compare their entrepreneurial intention (Ahmed et al., Citation2019; Asimakopoulos et al., Citation2019; Jiatong et al., Citation2021; Thomas, Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, despite published evidence supporting the influence of personality on entrepreneurial intention (Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Awwad & Al-Aseer, Citation2021; Hossain et al., Citation2021; Laouiti et al., Citation2022; Mei et al., Citation2017; Udayanganie et al., Citation2019), little is known with reference to the relationship between students’ personality and their intention to start technology businesses by discipline of study. In this regard, Vodă and Florea (Citation2019) evaluated the influence of the personality of business and engineering students from Romania without directly contrasting students from both degree programs, arguing that locus of control and need for achievement are personal characteristics, associated with personality, that positively influence the intention to create a business in the future. In Latin America, this lack of information is relevant due to the high percentage of students who choose to study business administration and engineering careers (Montes & Osorio, Citation2023), as well as the importance of science and technology-based entrepreneurship for the economic growth of this region (Kantis & Angelelli, Citation2020).

Comparative research on entrepreneurial intention has been frequently conducted in the last decade, as studies have contrasted the entrepreneurial intention of university students by gender (Chafloque-Cespedes et al., Citation2021; Fragoso et al., Citation2020), the entrepreneurial intention among university students from different countries (Díaz-Casero et al., Citation2012), the entrepreneurial intention among students from entrepreneurial and non-entrepreneurial families (Georgescu & Herman, Citation2020; Oluwafunmilayo et al., Citation2018), the entrepreneurial intention of students with higher and lower incomes (Millman et al., Citation2010), and the entrepreneurial intention among engineering and business administration students (Klapper & Léger-Jarniou, Citation2006). While comparing students in management and engineering may seem unfair due to the differences in their curriculum, this comparative analysis is necessary and relevant as it provides a better understanding of the implications of these differences and could guides the implementation of strategies to enhance the professional education; in this regard, prevous studies have compared students in management and engineering and proposed evidence-based practical recommendations to improve their education (Chan & Fong, Citation2018; Lishchynska et al., Citation2023; Zakaria et al., Citation2019).

Moreover, comparing the relationship between personality and entrepreneurial intention among business administration and engineering students is also relevant since business administration careers are more related to social and economic sciences by integrating the study of behavioral sciences (Universia, Citation2023), and, in contrast, engineering and technology careers require the study of physics, chemistry and mathematics at an advanced level (Godwin et al., Citation2016; Morris et al., Citation2019) as well as a more in-depth study of complex software (Tepper, Citation2014). Notwithstanding these disciplinary differences, both areas of study tend to promote entrepreneurship and business creation in their curricula through mandatory or elective courses related to entrepreneurship. Moreover, it is common that entrepreneurship programs implemented in Latin American universities involve lecturers or students from different disciplines who work collaboratively in the search for solutions to problems in the market, using research and development techniques and proposing innovations that solve relevant problems of population groups (Benavides-Sánchez et al., Citation2021; Estrada Molina, Citation2022).

This research attempts to develop new knowledge analyzing differences in entrepreneurial intention to start businesses related to digitalization of banking and finance, information technology and telecommunications, e-commerce services, health technology services and distance education, between business administration and engineering and technology students. Furthermore, this study evaluates the relationship between the students’ personality traits of both areas of study and their intention to start these businesses. In order to obtain new evidence, 544 responses were obtained from university students in Chile and Ecuador to an online self-report questionnaire that included the evaluation of entrepreneurial intention using the adaptation of the scale using Liñán and Chen (Citation2009) to assess five selected emerging technology businesses. The measurement of personality traits has been performed using the Big Six personality model (Agency, Agreeableness, Openness, Neuroticism, Extraversion and Conscientiousness) that is based on the framework of Lachman and Weaver (Citation1997). The analysis was conducted through central tendency comparisons, Spearman’s correlation coefficient and the Sidak test for comparison of frequency distributions. Such statistical methods have been selected because this research seeks to compare the magnitude of entrepreneurial intention of students enrolled in different careers and to study the relationship of personality with entrepreneurial intention. Additionally, this selection has been justified by the absence of normal distribution in the data obtained, which was verified with the Shapiro Wilk test.

The study of personal psychological variables that affect the creation of entrepreneurship has been approached through theoretical models related to entrepreneurial behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991; Bosma et al., Citation2021; Shapero & Sokol, Citation1982). From a theoretical perspective, this research provides new information on differences in the intention to start new technology businesses by career and on the relationship of personality traits with the intention to start new technology businesses by discipline of study. Such evidence could complement the findings of previous research that have analyzing the entrepreneurial intention of management students (Jena, Citation2020; Trivedi, Citation2017) or engineering students (Asimakopoulos et al., Citation2019; Kurniawan et al., Citation2018), by enhance the understanding about differences between students enrolled in these careers. From a practical perspective, these findings can guide the efforts of universities and governmental organizations in Latin America, that are associated with the training of technology entrepreneurs who must be capable of improving people’s lives through new technology solutions and developing businesses that facilitate remote shopping, work, health, education and finance through the digitization of services. Enhancing the training of university students to increase their participation in technological entrepreneurship is particularly important in Latin-American countries, because their economies are still strongly related to the extraction of natural resources as mining and forestry businesses (Merino, Citation2020; Svampa, Citation2019).

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Entrepreneurial intention

Entrepreneurial intention is defined by Engle et al. (Citation2010) as a person’s willingness to start a business on his or her own. In a similar vein, Chhabra et al. (Citation2020) propose that entrepreneurial intention is a state of mind that eventually leads an individual toward forming a new business concept and pursuing a career in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial intention is a particularly important concept in the field of entrepreneurial behavior because it has a high ability to predict future venture creation (Lüthje & Franke, Citation2003); likewise, it has been recognized that entrepreneurial intention is the first step in understanding the process of entrepreneurial behavior in global terms (Ilevbare et al., Citation2022; Nguyen, Citation2017). Several researches have assessed the entrepreneurial intention of people in countries of Asia, Africa, Europe, America, and Oceania (Beynon et al., Citation2020; Gomes et al., Citation2022; Lopez et al., Citation2021; Ni & Ye, Citation2018; Ratten, Citation2022), among such research, initiatives have aimed at understanding factors affecting entrepreneurial intention (Aloulou, Citation2021; Lingappa et al., Citation2020; Neneh, Citation2022) and also have aimed at recognizing personal demographic and psychological characteristics associated with a higher and lower entrepreneurial intention (Ferreira et al., Citation2012; Nguyen, Citation2018; Sahinidis et al., Citation2020).

The study of entrepreneurial behavior has considered theoretical frameworks such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991), the Model of the Entrepreneurial Event (Shapero & Sokol, Citation1982), and the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) theory (Bosma et al., Citation2021). These models propose that entrepreneurial behavior is explained by various environmental and individual factors that could lead to the initiation of a new business. Among the individual conditions, these reference theoretical frameworks have considered various psychological variables associated with the creation of entrepreneurship. The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) proposes that attitudes towards a behavior, subjective norms related to social pressure, and perceived control over the behavior affect entrepreneurial intention, and subsequently, entrepreneurial intention promotes entrepreneurial behaviors. The GEM model distinguishes, as factors incident to entrepreneurship, firstly, the social, cultural, political, and economic context, secondly, the social values that impact entrepreneurship, and thirdly, individual attributes of a psychological, demographic, and motivational nature (Bosma et al., Citation2021). The Shapero and Sokol’s model (1982) argues that the perceived desirability related to the degree of attraction that a person feels towards a behavior -in this case, becoming an entrepreneur-, the propensity to act that implies a person’s disposition to decide to take action, and the perceived feasibility associated with people’s self-perception of their capabilities to perform an action, affect the intention to create new businesses.

Several studies on entrepreneurial intention have analysed the university students’ entrepreneurial intention, particularly, they have evaluated the effects of university education on the intention to create new businesses (Aladejebi, Citation2018; Thoyib et al., Citation2016; Yousaf et al., Citation2022). An example of the international assessment of students’ entrepreneurial intention is the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey (GUESS) that has published reports about entrepreneurial spirit in more than 50 countries since 2003 (Guesss, Citation2022). Complementarily, the moderating effect of culture on the positive relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention has been argued (Yousaf et al., Citation2022), the positive influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention in undergraduate engineering students has been evidenced (Nwibe & Bakare, Citation2022) and the effect of pre-university entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intention (Delim et al., Citation2022) have been supported. A considerable proportion of this recent research has assessed students in Africa and Asia (Ntshangase & Ezeuduji, Citation2022; Munawar et al., Citation2023; Okagbue et al., Citation2023; Yan et al., Citation2023). Moreover, the effect of university education on entrepreneurial activity under the context of the COVID-19 pandemic has been studied in Latin American countries (da Rocha et al., Citation2022; Jones et al., Citation2021).

In relation to the entrepreneurial intention related to relevant businesses for the economic activity of countries, previous research has analyzed the magnitude of entrepreneurial intention and factors that affect it, concerning businesses such as tourism (Kusumawardani et al., Citation2020), e-commerce businesses (Lai & To, Citation2020) and sustainable businesses (Truong et al., Citation2022). In recent years, some studies have assessed entrepreneurial intention toward businesses involving new technologies (Dana et al., Citation2021; Farzin, Citation2015) as the entrepreneurial intention toward business located mainly in the sector of new technologies and Internet industries called Start-Ups (Kowalczyk, Citation2020); in this area, it has been supported that a favorable entrepreneurship ecosystem and the support of entrepreneurial education in universities positively affect students’ entrepreneurial/Startup intention (Gupta, Citation2022). Furthermore, research have compared the entrepreneurial intention of students from different countries or cultures, suggesting a higher entrepreneurial intention of students from the USA compared to students from Turkey (Naktiyok et al., Citation2010), a higher entrepreneurial intention of students from India compared to students from Saudi Arabia (Tausif et al., Citation2021) and a higher intention of entrepreneurship in underdeveloped countries compared to developed countries (Otchengco & Akiate, Citation2021).

Studies have also assessed the entrepreneurial intention in specifics disciplines of study as medical students (Jiatong et al., Citation2021), accounting students (Ahmed et al., Citation2019) hospitality and tourism students (Zhang et al., Citation2020), engineering students (Asimakopoulos et al., Citation2019), and business administration students (Thomas, Citation2022). Despite of theses analysis, little research has focused to directly compare the entrepreneurial intention of students from different fields of study. In this regard, Kolvereid and Moen (Citation1997) compared the behavior of business graduates majoring in entrepreneurship and graduates in other majors at a Norwegian business school, showing that graduates majoring in entrepreneurship are more likely to express higher entrepreneurial intentions and to start new businesses. More recently, Adelaja (Citation2021) compared the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention in non-technical and technical students, recognizing only a weak relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention in non-technical students. In the context of Latin America, there has been no in-depth comparison of entrepreneurial intention toward emerging technology businesses due to changes in people’s lives after the COVID-19 pandemic, between business administration and engineering and technology students.

Since it has been recognized that career choice is associated with personal interests in fields such as social sciences, arts and technology (Ackerman & Beier, Citation2003; Kaleva et al., Citation2023; Maksimovic et al., Citation2020), this research to propose that entrepreneurial intention should also be differentiated by students’ personal interests, particularly, students might evidence differences in their intention to start businesses related to several areas of interest like arts, finances, commerce, foresting. agriculture, or biological sciences, among others. Regarding the comparison between business administration and engineering and technology students these variations of interests that are associated with preferences more closeness to their subjects of study, should imply discrepancies on the intention to create business in areas with emerging technologies as IT and telecommunications, digitalization of banking and finance, e-commerce services, health technologies and distance education. Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 1: Entrepreneurial intention to start emerging technology businesses is different between business administration and engineering and technology students.

2.2. Personality

Individual personality has been defined as a set of individual characteristics that influence motivations, behaviors and emotions when facing a given circumstance (Damasio & Sutherland, Citation1994). Personality is a very important attribute in a person’s life because it is the basis for gathering information about their individual characteristics (Mishra & Sagnika, Citation2021), in that sense, the influence of students’ personality has been supported in domains as students’ academic achievements (Lateef et al., 2022) and students’ academic satisfaction with the process of learning (Trógolo & Medrano, Citation2012). Complementarily, personality has been supported as a relevant predictor of behaviors in diverse areas such as social network addiction (Abbasi & Drouin, Citation2019), online shopping frequency (Ayob et al., Citation2022), the way of selecting friends on online platforms (Zhou et al., Citation2021), purchase intention for new smartphones (Rai, Citation2021), and altruistic behaviors aimed at helping other people (Lu et al., Citation2020). In the GEM Model (Bosma et al., Citation2021), personality can be included as a psychological variable within the dimension of individual attributes that is related to entrepreneurial activity. In the context of the Theory of Planned Behavior, Ajzen (Citation2020, p.5) has argued that: ‘personality traits, intelligence, demographic characteristics, life values, and other variables of this kind are considered background factors in the TPB. They are assumed to influence intentions and behavior indirectly by affecting behavioral, normative, and/or control beliefs’, moreover, ‘that background factors can provide valuable information about possible precursors of behavioral, normative, and control beliefs, information not provided by the theory itself’.

Personality has been assessed using various theoretical constructs since the beginning of the 20th century. A model that has increased its use in the 21st century is HEXAC, disseminated by Ashton and Lee (Citation2007) that incorporates six personality traits, these are: Honesty-Humility (H), Emotionality (E), eExtraversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), and Openness to Experience (O). A predecessor personality model of HEXACO that has been widely used in academic research is the Big Five, which assesses individual personality through five personality traits; in particular, this model published by Costa and McCrae (Citation1988, Citation1992) proposes that personality is conformed by the integration of the following five individual traits: agreeableness (A), conscientiousness (C), extraversion (E), openness (O), and neuroticism (N).

The Big Five model states that agreeableness is the personal tendency to be cooperative, forgiving, compassionate, understanding, and trusting (Fincham & Rhodes, Citation2005); conscientiousness is a person’s tendency to demonstrate self-discipline and strive for competence and achievement (Greenberg, Citation2011); extraversion is an individual’s propensity to seek stimulation and enjoy communication with other people (Greenberg, Citation2011); openness to experience is an individual’s degree of open-mindedness, curious, imaginative, and originality (Costa & McCrae, Citation1992); and neuroticism is a predisposition to experience negative affect, therefore, individuals with a high level of neuroticism experience more anxiety, depression, and hostility (Stone & Costa, Citation1990). Complementarily, Lachman and Weaver (Citation1997) proposed an extension of the Big Five model by adding the personality trait agency, thus constituting a model with six personality traits called Big Six. The agency trait is understood as individualization in a group and implies independence, dominance over others and the seeking of personal growth, as opposed to communion that is associated with personal willingness to collaborate with other people to achieve shared goals (Bakan, Citation1966).

The study of the influence of university students’ personality traits on their entrepreneurial intention through the Big Five and Big Six models has presented diverse results. Awwad and Al-Aseer (Citation2021) asked 323 university students in Jordan and supported that awareness, openness, and alertness were associated with overall entrepreneurial intention after. Udayanganie et al. (Citation2019) analyzed the responses of 202 engineering students in Sri Lanka and evidenced that emotional stability (contrary to neuroticism) and openness to experiences positively affect overall entrepreneurial intention. Hossain et al. (Citation2021) analyzed the responses of 354 business students in Bangladeshi universities and supported that agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, emotional stability (contrary to neuroticism), and openness affect social entrepreneurial intention. Laouiti et al. (Citation2022) analyzing the responses of 531 students in one business school in southern France and showed that openness to experience, emotional stability (as opposed to neuroticism) and agreeableness are positively related to entrepreneurial intention. Mei et al. (Citation2017) evaluated the responses of 280 students from China and evidenced that Emotional Stability, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, and Interpersonal Relationship are positively associated with entrepreneurial intention in general. Ahmed et al. (Citation2022) evaluated the responses of 274 students from different universities in Pakistan and argued that only the trait Conscientiousness positively affects the students’ entrepreneurial intention.

In reviewing the research published in the last 10 years that has been focused on the influence of personality on entrepreneurial intention, it is recognized that the vast majority of such studies support a relationship between personality and entrepreneurial intention; likewise, that their results show important variations according to the country in which these studies are conducted and the characteristics of the students asked. In addition, mostly of these studies evaluate entrepreneurial intention globally, without investigating entrepreneurial intention in specific business areas and without comparing student groups by the career in which they are enrolled. Considering such previous evidence, this research proposes that the personality traits of business administration and engineering and technology students in Latin America should also be related to their intention to start new technology businesses with increasing importance after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, the following research hypotheses is proposed.

Hypothesis 2: The personality traits of university students in Latin America are related to their entrepreneurial intention to start emerging technology businesses.

Moreover, due to the diversity of results obtained in previous studies according to the degree programs of the students evaluated, this research proposes that there should be differences in the relationship between personality and entrepreneurial intention toward technology ventures between business administration students and engineering and technology students. This approach can also be supported by publications that have recognized differences regarding personal preferences that impact the student’s choice of career path in college; in this regard, Blotnicky et al. (Citation2018) argued that students with greater interest in technical and scientific skills are more likely to select a STEM career than those who preferred professional activities that involve practical, productive, and concrete activities. In addition, previous research has argued that personality influences personal preferences in various domains such as product selections (Xu & Jin, Citation2020), selection of disciplines of study (Knapp, Citation1990) and the preferences towards online learning and remote work (MacLean, Citation2022). Thus, this research proposes that personality traits, among business administration and engineering and technology students, should be differentially linked to their intention to start emerging technology businesses related with IT and telecommunications, digitalization of banking and finance, e-commerce services, health technologies and distance education. Consequently, the following research hypotheses is proposed.

Hypothesis 3: The relationship between personality traits and intention to start emerging technology businesses is different among business administration students and engineering and technology students.

3. Methodology and methods

3.1. Measurement

This research is quantitative and uses the method of self-administered online questionnaires that were distributed through SurveyMonkey platform. Responses were obtained during the academic semesters of 2022. The questionnaire included the Liñán and Chen (Citation2009) scale to evaluate entrepreneurial intention, this scale uses six statements to assess entrepreneurial intention that are scored on a 7-point Likert scale, considering alternatives from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (7). The six statements of the Liñan and Chen scale were adapted to evaluate the entrepreneurial intention related to five emerging technology business that have become more relevant after the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. For example, the statement associated to digitalization of banking and finance have been: 1- I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur on digitalization of banking and finance sector, 2- My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur on digitalization of banking and finance sector, 3- I will make every effort to start and run my own firm on digitalization of banking and finance sector, 4- I am determined to create a firm on digitalization of banking and finance in the future, 5- I have very seriously thought of starting a firm on digitalization of banking and finance sector, 6- I have the firm intention to start a firm on digitalization of banking and finance sector someday. The selection of these 5 areas described below, is based on the fact that they are growing businesses due to changes in life after the COVID-19 pandemic (Rivas, Citation2021).

Digitalization of banking and finance: Related to provide services for digitization of finances as the automation of processes for online payments, digital savings and investment, digital currencies (blockchain) and improvements in online payment methods.

IT and telecommunications businesses: Related to supporting digitization of companies, delivering information systems consulting services, cybersecurity services and software development.

E-commerce services businesses: Related to provide services for the sale of products through e-commerce include storage and transportation of products, improvements in pre-sale and post-sale services, expanded reality to display products, dissemination of products in digital media such as social media, and solutions to improve the security of online purchases.

Health technologies businesses: Related to provide services or goods for telemedicine, the development of tools/methods for disease prevention and data management aimed at improving people’s health.

Distance education businesses: Related to deliver technical or professional online education and online professional upgrading.

In order to measure entrepreneurial intention, the arithmetic mean of the six statements of the Liñán and Chen (Citation2009) scale was calculated in these 5 technology business areas analyzed. The calculation of the arithmetic mean is based on the high reliability of the Liñán and Chen (Citation2009) scale which has been used for the measurement of entrepreneurial intention in several research published in the last five years (Barba-Sánchez et al. Citation2022; Kieu, Citation2022; Taneja et al., Citation2023; Sargani et al., Citation2019). To verify this reliability, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated for the 6 statements among the 5 technology businesses. All Cronbach’s alpha coefficient were higher than .7 that represents an acceptable reliability (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1978); likewise, previous research have obtained an indicator of entrepreneurial intention by calculating the arithmetic mean of the statements (Arribas et al., Citation2012; Wu et al., Citation2019).

The questionnaire has also included the personality scale proposed by Lachman and Weaver (Citation1997), which has been used and validated in recent research (Li et al., Citation2022; Sutin et al., Citation2018). The Lachman and Weaver (Citation1997) personality scale called The Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI), measures the six personality traits of the Big Six model. As previously stated, the six personality traits in this model are: agency, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, conscientiousness and extraversion. The selection of the MIDI scale was based on the fact that it includes a smaller number of personal characteristics associated with each personality trait, which allows obtaining a larger number of responses in a limited time frame. The scale has been developed from the need to measure personality traits in less time, its authors selected a list of adjectives commonly used in previous scales to measure personality (Joshanloo, Citation2018).

A parameter for each personality trait was also calculated based on the arithmetic mean of the personal qualities linked to each trait. Obtaining an indicator associated with each trait based on the arithmetic mean of the personal characteristics linked to each personality trait, is the original procedure defined in The Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) (Lachman & Weaver, Citation1997). Additionally, this procedure based on the arithmetic mean has been used in recent papers that measured the magnitude of individual personality through The Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) (Grzywacz & Marks, Citation2000; Lehberger et al., Citation2021). The Lachman and Weaver (Citation1997) scale begin with the phrase ‘Please indicate how well each of the following describes you’ and determines the magnitude of each personal characteristic with four levels of magnitude: not at all (1), a little (2), quite a lot (3), and very much (4). The personality scale items (Lachman & Weaver, Citation1997) were translated from English to Spanish to collect responses from Spanish-speaking students, and then translated back into English for presentation in this research. Before the final distribution of the questionnaire, a review of the questionnaire was carried out. shows the personal characteristics associated with each personality trait.

Table 1. Personal attributes related to personality traits.

3.2. Sample

The complete responses of 190 university students from Chile and 354 students from Ecuador were analyzed, totaling 544 students. Student from Chile were enrolled at Universidad de Las Américas of Chile (100%). Student from Ecuador were enrolled at Universidad de Las Fuerzas Armadas (45%) Escuela Politécnica Nacional (41%) and Pontificia Universidad Católica de Ecuador (14%). The students were selected through non-probability convenience sampling, which is a technique widely used in research that asks university students (Margaça et al., Citation2021; Núñez-Canal et al., Citation2022; Pinto Borges et al., Citation2021). Responses were obtained during the first and second academic semesters of 2022, for this purpose, emails were sent to students to request their responses on the SurveyMonkey platform The survey included a written informed consent request based on the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Universidad de Las Américas (ID: 44/2022). Only students who accepted the informed consent had access to the online survey questions. Moreover, this research has analyzed complete and error-free responses.

Among de 544 students who completed the survey, 383 students were enrolled in careers in business administration, finance, commerce and marketing, and 161 students were enrolled in careers associated with engineering and technology. Furthermore, the sample included 281 women and 262 men. The differences in the number of responses between men (107) and women (54) in engineering careers are consistent with the gender differences in STEM careers, since it has been recognized that the percentage of women studying Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics is significantly lower in Latin America (Camacho et al., Citation2021); on the other hand, women prefer, to a greater extent, to study careers associated with social sciences in this region (Universia, Citation2022). The average age of the students surveyed was 25,303 years, 24,996 years for women and 25,653 years for men. describes the number of students surveyed by career and gender.

Table 2. Description of sample.

3.3. Statistical analysis

Because this research seeks to compare the level of entrepreneurial intention toward emerging technology businesses between students enrolled in business administration careers and students enrolled in engineering and technology careers, a central tendency and dispersion analysis based on arithmetic mean, median, standard deviation and interquartile range was used. Furthermore, the differences in frequency distributions and central tendency of entrepreneurial intention between the two groups compared were evaluated through the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. This non-parametric test has been selected instead of traditional parametric tests such as ANOVA or t-Students because the frequency distribution of the data associated with entrepreneurial intention did not fit a normal distribution, which was determined through the Shapiro Wilk normality test (p-values < .005 related to entrepreneurial intention for all business areas). The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test has been recognized as a reliable substitute for ANOVA if the assumption of normality is not met (Goni et al., Citation2009).

Complementarily, Spearman correlation coefficients have been calculated in order to evaluate the link between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention in each business area. This correlational analysis has been performed among the group of business administration and engineering and technology students to compare the results obtained between these groups. Spearman’s correlation coefficient has been selected instead of Pearson’s coefficient because the data obtained on the variables did not fit a normal distribution, which was verified with the Shapiro Wilk test (p < .005). Additionally, the Sidak-adjusted test was used in order to recognize the statistically significant correlation coefficients. The adjusted Sidak test is more accurate (and rigorous) in assessing the significance of correlations by reducing the Type I error in hypothesis testing, ie it avoids rejecting the null hypothesis that states the absence of correlation when it is true and should be accepted (Salyakina et al., Citation2005). Statistical analysis was performed with STATA version 16.

4. Results

4.1. Central tendency and dispersion comparison

below compares the entrepreneurial intention to start the 5 technology ventures between business administration and engineering and technology students. It is recognized that arithmetic mean of the intention to start businesses to digitalization of banking and finance and e-commerce services was higher in business administration students, although the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test only supported, with 95% confidence (p = .019), a higher entrepreneurial intention to star business to digitalization of banking and finance in business administration students. Engineering and technology students showed a higher entrepreneurial intention to start IT and telecommunications, health technologies and distance education businesses, highlighting the difference of arithmetic mean of entrepreneurial intention to create IT and telecommunications businesses (.79) between business administration and engineering and technology students. A higher variability of the entrepreneurial intention of Business Administration students is also recognized in most of the business areas, which is supported by higher standard deviations and interquartile ranges.

Table 3. Central tendency and dispersion of entrepreneurial intention.

4.2. Correlation analysis

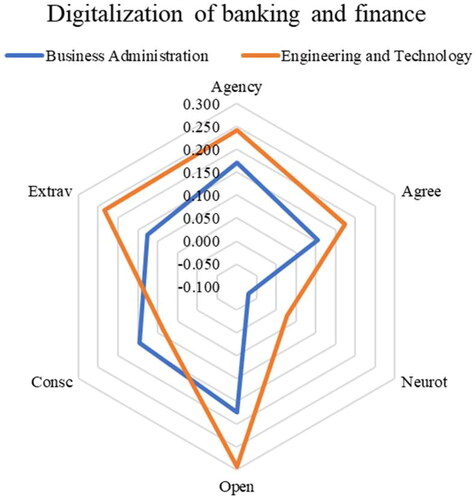

presents the correlation coefficients between the intention to start a business to digitalization of banking and finance and personality traits, comparing the responses between business administration and engineering and technology students. The p-values of the Sidak-adjusted test have been included. The results show that the correlations related to agency and openness traits were significant in both areas of study with 95% confidence (p < .05). A positive and significant correlation between the conscientiousness trait and entrepreneurial intention was also supported only in business administration students with 90% confidence (p = .087), and a positive and significant correlation between the extraversion trait and entrepreneurial intention was supported only in engineering and technology students with 90% confidence (p = .058).

Table 4. Correlation coefficients between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention to start businesses to digitalization of banking and finance.

below shows that the correlation coefficients linked to the intention to start business to digitalization of banking and finance were higher for engineering and technology students. It also highlights the positive magnitude of the correlation coefficient related to the openness trait in engineering and technology students (.293).

Figure 1. Comparison of correlations associated with business to digitalization of banking and finance by group of students.

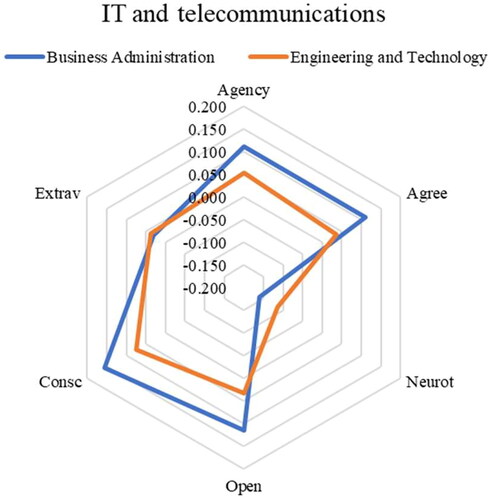

presents the correlation coefficients between the intention to start IT and telecommunications businesses and personality traits, comparing the responses between business administration and engineering and technology students. Likewise, the p-values of the Sidak-adjusted test were included. The results show that only personality traits of business administration students are significantly correlated with their intention to start IT and telecommunications businesses with 95% (p < .05) confidence. Particularly, the neuroticism trait is negatively correlated (p = .035) and the conscientiousness trait is positively correlated (p = .049) with the entrepreneurial intention. No statistically significant correlation coefficients were obtained between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention toward IT and telecommunications businesses in engineering and technology students.

Table 5. Correlation coefficients between personality traits and intention to start IT and telecommunications businesses.

compares the correlation coefficients linked to the responses of both groups of students. Correlation coefficients of higher magnitude, positive and negative, were recognized in the business administration students.

Figure 2. Comparison of correlations associated with IT and telecommunications business by group of students.

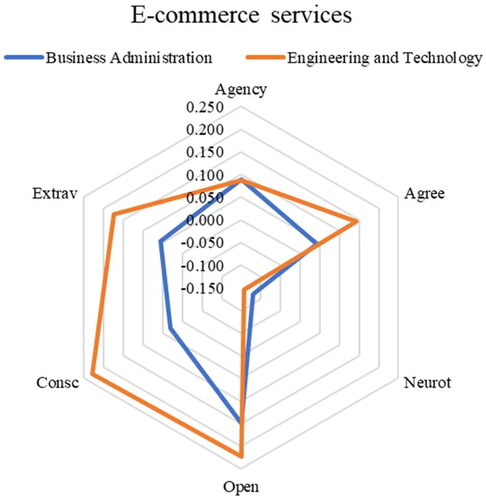

presents the correlation coefficients between the intention to start e-commerce service business and personality traits, comparing the responses between business administration and engineering and technology students. The results showed that the openness trait has a significant and positive correlation with entrepreneurial intention to start e-commerce service business in the group of business administration students with 90% confidence (p = .069) and also with entrepreneurial intention to start e-commerce service business in the group of engineering and technology students (p = .091). Additionally, a positive and significant correlation between the conscientiousness trait and entrepreneurial intention were evidenced only in engineering and technology students (p = .067).

Table 6. Correlation coefficients between personality traits and intention to start e-commerce business.

represents the correlation coefficients of both groups of students. Positive correlation coefficients with higher magnitude were recognized in engineering and technology students, highlighting the positive and significant correlation coefficients linked to the openness and conscientiousness traits.

Figure 3. Comparison of correlations associated with e-commerce services business by group of students.

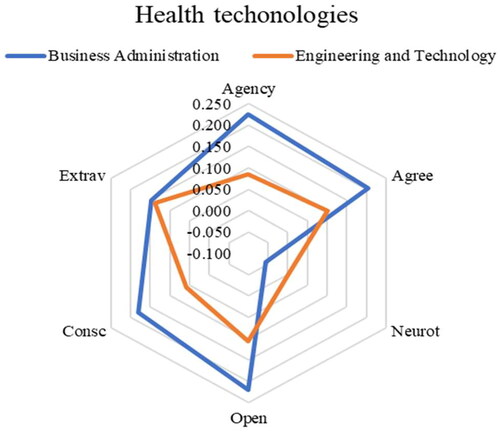

presents correlation coefficients obtained between intention to start a health technology business and personality traits, comparing the responses between business administration and engineering and technology students. The findings supported positive and significant correlation coefficients only in business administration students, particularly, significant coefficients linked to agency (p = .000), agreement (p = .001), openness (p = .000), conscientiousness (p = .009) and extraversion (p = .074) traits. No significant correlation coefficients were obtained in engineering and technology students.

Table 7. Correlation coefficients between personality traits and intention to start health technology business.

compares the correlation coefficients obtained in both groups of students. It was observed that the correlation coefficients in the group of management students were higher than in the engineering and technology students in this business area, except for the correlation coefficient of neuroticism. The higher magnitudes of the correlation coefficients related to the trait agency (.226) and openness (.219) in the business administration students stand out.

Figure 4. Comparison of correlations associated with health technologies business by group of students.

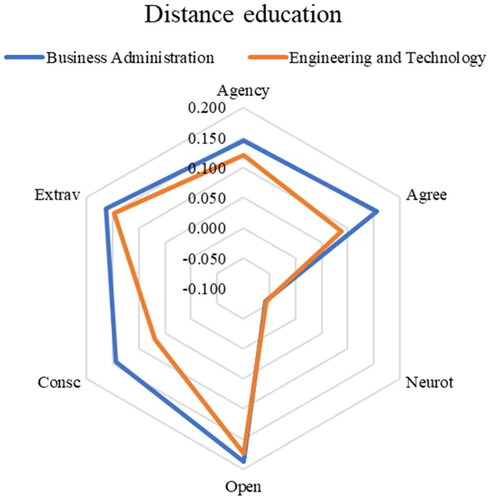

shows the correlation coefficients between the intention to start distance education businesses and personality traits, comparing the responses between business administration and engineering and technology students. The findings have evidenced that only personality traits in business administration students are significantly correlated with entrepreneurial intention to start distance education businesses with 95% (p < .05) or 90% (p < .10) confidence; particularly, significant correlation coefficients related to agency (p = .093), agreement (p = .046), openness (p = .005), conscientiousness (p = .092) and extraversion (p = .028) traits. No statistically significant correlation coefficients were obtained between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention toward distance education business in engineering and technology students.

Table 8. Correlation coefficients between personality traits and intention to start distance education business.

compares the correlation coefficients obtained in both groups of students. As in the case of the health technology business, higher correlation coefficients were observed in business administration students.

4.3. Acceptance or rejection of hypotheses

The information presented below in synthesizes the findings supported by the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, Spearman correlation coefficients and the Sidak-adjusted test.

Table 9. Validation or rejection of hypotheses.

5. Discussion

This research seeks to compare the intention to create technology ventures between business administration and engineering and technology students in Latin America; additionally, this study evaluates the relationship of students’ personality traits with their intention to create these ventures. The findings presented in have demonstrated that there are significant differences between the entrepreneurial intention of business administration students and engineering and technology students. in particular, it has been recognized that business administration students only show a greater entrepreneurial intention toward businesses associated with e-commerce services and digitalization of banking and finance, although significant differences regarding business to digitalization of banking and finance business have not been supported with 95% (p < .05) or 90% (p < .10) confidence. Conversely, engineering and technology students showed a higher entrepreneurial intention toward IT and telecommunications, health technologies and distance education businesses with 99%, 95% or 90% confidence. These results allowed to accept hypothesis 1 which states that the entrepreneurial intention toward emerging technology businesses is different between business administration and engineering and technology students.

Furthermore, the relationship between some personality traits of students and their intention to create technology businesses has been supported through the Sidak-adjusted test in of this study. The findings obtained supported the hypothesis 2 which states that students’ personality traits are related to their entrepreneurial intention toward emerging technology businesses. These results are consistent with previous findings that supported the relationship between personality traits and the intention to create new ventures (Karabulut, Citation2016; Rohman & Miswanto, Citation2020). In this sense, the correlations coefficients obtained between openness trait and the entrepreneurial intention have been positive and significant in most business areas, which is in line with various studies that evidenced a positive, strong and significant relationship between openness trait and intention to start a new venture (Awwad & Al-Aseer, Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2022; Tuncer & Şahin, Citation2018; Udayanganie et al., Citation2019). This relationship between openness trait and entrepreneurial intention can be explained since openness trait personality is positively associated with creativity (Corazza & Agnoli, Citation2020) and innovative behaviors (Kurz et al., Citation2018), and such qualities are also characteristic of entrepreneurs. Previous studies have concluded that creativity positively impact on entrepreneurial intention (Shi et al., Citation2020) and that previous students’ innovative behaviors affect their future entrepreneurial intentions (Huang et al., Citation2021).

When comparing the influence of personality on entrepreneurial intention among the areas of study, in the group business administration the positive and significative correlation coefficients between conscientiousness, extraversion, agency and agree, and the intention to start health technology and distance education businesses have been highlighted. Differently, in the group of engineering and business students, the positive and significative correlation coefficients linking the openness and conscientiousness traits with the intention to start e-commerce businesses stand out, as well as the correlation coefficients linking the agency, openness, and extraversion traits with the intention to start business to digitalization of banking and finance. Such findings are in line with results of previous research that, although they supported a relationship between personality and entrepreneurial intention, also showed substantial variations regarding which traits are related to entrepreneurial intention according to the country where the research were conducted and the characteristics of the persons in the sample (Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Awwad & Al-Aseer, Citation2021; Hossain et al., Citation2021; Laouiti et al., Citation2022; Mei et al., Citation2017; Udayanganie et al., Citation2019).

5.1. Theoretical implications

Personality is a psychological variable widely studied in various areas of human behavior, including entrepreneurship, therefore, the findings of this study are consistent with this theoretical framework and deepen the understanding of the influence of personal interests and personality on the intention to start emerging technology ventures. The findings are framed within the theoretical models that explain entrepreneurial behavior, such as the GEM model that incorporates psychological variables as conditions that may be related to the creation of ventures. In addition, as Ajzen (Citation2020) has argued, personality traits, intelligence, demographic characteristics, vital values, and other such variables are considered background factors in the theory of planned behavior, and it is assumed that these indirectly influence intentions and behavior by affecting behavioral, normative, and/or control beliefs. The theory of planned behavior has been employed in recent research aimed at determining factors that affect entrepreneurial intention in different academic programs (Yaser Hasan et al., Citation2020) and also to understand personal conditions associated with digital entrepreneurial intention of university students (Al-Mamary & Alraja, Citation2022).

From the theoretical point of view, the present study has allowed (1) to carry out an integration of the literature in relation to the entrepreneurial intention towards emerging technological businesses (2) to analyze differences between students of business administration and engineering and technology in their intention to start businesses of banking and digital finance, information technology and telecommunications, services for electronic commerce, technological services for health and distance education (3) evaluates the relationship of the personality traits of the students of both study areas with their intention of undertaking in these businesses (4) contributes to include information on entrepreneurial intention and personality traits when starting technological businesses of students immersed in different training, such as technology and administration careers.

Considering the five-factor theory of personality (Costa & McCrae, Citation1988, Citation1992), this research deepens the understanding of the interaction between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention towards emerging technology businesses, suggesting that the interaction of personality and entrepreneurial intention towards emerging technology businesses is different between business administration students and engineering students. In this sense, in business administration students, a greater number of significant correlation coefficients have been found between personality and entrepreneurial intention associated with IT and telecommunications, distance education, health technologies, and conversely, a lower number of significant correlation coefficients between personality and entrepreneurial intention associated with digitalization of banking and finance, E-commerce services. Finance and commercialization courses are relevant to the training of business administration professionals. The personality traits that have shown significant correlations with entrepreneurial intention in this research are consistent with the qualities of entrepreneurs that have been highlighted in previous research, as it has been recognized that individuals with a greater propensity to develop entrepreneurship tend to exhibit higher levels of extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness, and lower levels of neuroticism (Gao et al., Citation2020; Heydari et al., Citation2023). Recently, Al-Mamary and Alshallaqi (Citation2022) argued about the impact of autonomy, innovativeness, and risk-taking propensity on the entrepreneurial intention of university students; these characteristics are consistent with the individual traits of the personality traits identified.

Likewise, the comparison between business administration and engineering students, as well as comparisons by gender, family background, and income level previously published (Chafloque-Cespedes et al., Citation2021; Fragoso et al., Citation2020; Georgescu & Herman, Citation2020; Millman et al., Citation2010; Oluwafunmilayo et al., Citation2018), is relevant as it allows for a better understanding of how individual differences incorporated in frameworks such as the GEM model are related to people’s propensity to create new technological businesses. Kuckertz and Wagner (Citation2010) have recognized differences in entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions between business and engineering students. In this line, this study contributes to knowledge in this field by incorporating the relationship between personality and entrepreneurial intention among students in these careers. In addition, as has been proposed, the comparison between students enrolled in business administration careers in Latin American universities is important, due to the high number of students who choose to study business administration and engineering (Montes & Osorio, Citation2023) and due to the importance of science and technology-based entrepreneurship for the economic growth of this region (Kantis & Angelelli, Citation2020).

5.2. Practical implications

From a practical point of view, this research allows us to know the behavior and personality traits of these two types of students at the time of undertaking, this helps to guide the efforts, academic organization and decisions of universities and government organizations towards the training of students. The findings obtained allow to identify students with greater and lesser propensity to start technology businesses according to their career of study and their personality traits. Therefore, this research can guide the creation and implementation of university programs to strengthen technological entrepreneurship in Latin America considering the career of study in which the students are enrolled and their personality. Particularly, higher education institutions in Latin America could apply the Lachman and Weaver (Citation1997) personality test in order to assess the personality traits of their business administration and engineering and technology students. With this diagnosis they could recognize students with higher and lower propensity toward technology entrepreneurship, and using this information, they could implement plans and strategies to support students with higher intention to create technology business through funding, access to support networks and advanced training; likewise, they could promote technological entrepreneurship to develop interest in students less inclined toward these topics. Additionally, universities should develop competitions or technological entrepreneurship projects promoting the interaction of students from different careers to develop multidisciplinary perspectives. These initiatives could strengthen the interest in recent technologies and creation of new technology ventures in diverse areas, by generating experiences that are shared by students from several careers and interests.

6. Conclusions

This research provides new evidence regarding the differences in entrepreneurial intention to start technology ventures between business administration and engineering and technology students. The relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention has also been analyzed among students of these discipline areas. The findings of this research support difference in entrepreneurial intention between business administration and engineering and technology students. Moreover, the evidence has supported that engineering students who express a higher intention to engage in e-commerce service businesses are characterized by a specific personality configuration, as well as business administration students who express a higher intention to engage in computer and telecommunications, health technology, and distance education businesses.

The results deepen the understanding of the influence of personal interests and personality on the intention to start emerging technology ventures, furthermore, the evidence of this study suggests guidelines to strengthen technological entrepreneurship and economic and social development of these countries, through the implementation of programs based on mentoring and interdisciplinary competitions. Contributing to the knowledge of the students’ entrepreneurial intention related to technology ventures is important because the transformation of industries and consumer markets after the COVID-19 pandemic; in this line, it is necessary that university managers of Latin American achieve a better understanding on the relationship between students’ personality and their intention to create technology ventures.

7. Limitations and future research

This research compares business administration and engineering and technology students, however, engineering and technology students are enrolled only in industrial engineering, production engineering, and careers associated with computer science and telecommunications. Future research should analyze the entrepreneurial intentions of students enrolled in other engineering majors such as chemical engineering or biotechnology engineering. The results of this research have been presented in general terms without differentiating findings by demographic variables that may be of interest, such as students’ gender and income level; future research should compare the findings by such demographic groups to deepen the understanding of the results obtained. In addition, the convenience sample used in the research only incorporates university students from Chile and Ecuador which limits the generalization of the results; therefore, next studies should analyze students’ responses from other Latin American countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gustavo Barrera-Verdugo

Gustavo Barrera Verdugo is a Full Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Business at the Universidad de Las Américas in Chile. He holds a Doctorate and Master’s degree in Administration Sciences from the Universidad de Santiago de Chile, a Master’s degree in Marketing from the Universidad de Chile, and a Bachelor's degree in Economics and Administrative Sciences from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. His research focuses on demographics and psychological attributes of entrepreneurs and consumers.

Jaime Cadena-Echeverría

Jaime Cadena Echeverría has served as the Dean of the Facultad de Ciencias Administrativas at Escuela Politécnica Nacional de Ecuador. He holds a Master’s degree in Industrial Engineering and Productivity from the Escuela Politécnica Nacional de Ecuador. His research interests focus on entrepreneurship, small businesses, and higher education.

References

- Abbasi, I., & Drouin, M. (2019). Neuroticism and Facebook addiction: How social media can affect mood? The American Journal of Family Therapy, 47(4), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2019.1624223

- Ackerman, P. L., & Beier, M. E. (2003). Intelligence, personality, and interests in the career choice process. Journal of Career Assessment, 11(2), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072703011002006

- Adelaja, A. A. (2021). Entrepreneurial education exposure: a comparative investigation between technical and nontechnical higher education. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(5), 711–723. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-12-2020-0429

- Ahmed, E. R., Rahim, N. F. A., Alabdullah, T. T. Y., & Thottoli, M. M. (2019). An examination of social media role in entrepreneurial intention among accounting students: a SEM study. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 15(12), 577–589. https://doi.org/10.17265/1548-6583/2019.12.003

- Ahmed, M. A., Khattak, M. S., & Anwar, M. (2022). Personality traits and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of risk aversion. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(1), e2275. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2275

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

- Aladejebi, O. (2018). The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention among tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 6(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.15640/jsbed.v6n2a1

- Al-Mamary, Y. H. S., & Alraja, M. M. (2022). Understanding entrepreneurship intention and behavior in the light of TPB model from the digital entrepreneurship perspective. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100106

- Al-Mamary, Y. H., & Alshallaqi, M. (2022). Impact of autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness on students’ intention to start a new venture. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(4), 100239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100239

- Aloulou, W. J. (2021). The influence of institutional context on entrepreneurial intention: evidence from the Saudi young community. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 16(5), 677–698. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-02-2021-0019

- Alshebami, A. S., & Seraj, A. H. A. (2022). Exploring the influence of potential entrepreneurs’ personality traits on small venture creation: The case of Saudi Arabia. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 885980. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.885980

- Arribas, I., Hernández, P., Urbano, A., & Vila, J. E. (2012). Are social and entrepreneurial attitudes compatible? A behavioral and self‐perceptional analysis. Management Decision, 50(10), 1739–1757. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211279576

- Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868306294907

- Asimakopoulos, G., Hernández, V., & Peña Miguel, J. (2019). Entrepreneurial intention of engineering students: The role of social norms and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Sustainability, 11(16), 4314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164314

- Awwad, M. S., & Al-Aseer, R. M. N. (2021). Big five personality traits impact on entrepreneurial intention: the mediating role of entrepreneurial alertness. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-09-2020-0136

- Ayob, A. H., Wahid, S. D. M., & Omar, N. A. (2022). Does personality influence the frequency of online purchase behavior? International Journal of Online Marketing, 12(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJOM.299398

- Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence: Isolation and communion in Western man. Beacon Press.

- Barba-Sánchez, V., Mitre-Aranda, M., & del Brío-González, J. (2022). The entrepreneurial intention of university students: An environmental perspective. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(2), 100184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2021.100184

- Baruah, B., & Mao, S. (2021). An effective game-based business simulation tool for enhancing entrepreneurial skills among engineering students. 2021 19th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET) (pp. 01–06). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITHET50392.2021.9759800

- Benavides-Sánchez, E. A., Castro-Ruíz, C. A., & Quintero-Angel, M. (2021). Technology-based entrepreneurship enabling factors in higher education institutions with a limited entrepreneurial trajectory in Colombia. Cuadernos de Administración, 37(69), e2510766. https://doi.org/10.25100/cdea.v37i69.10766

- Beynon, M., Jones, P., Pickernell, D., & Maas, G. (2020). Investigating total entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurial intention in Africa regions using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Small Enterprise Research, 27(2), 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2020.1752294

- Blotnicky, K. A., Franz-Odendaal, T., French, F., & Joy, P. (2018). A study of the correlation between STEM career knowledge, mathematics self-efficacy, career interests, and career activities on the likelihood of pursuing a STEM career among middle school students. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0118-3

- Bosma, N., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelly, D., Guerrero, M., & Schott, T. (2021). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2020/2021 global report. The Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School.

- Camacho, A., Peñalvo, F. G., Holgadp, A. G., García, L., & Peñabaena, R. (2021). Construyendo el futuro de Latinoamérica: mujeres en STEM. Encuentro Internacional de Educación en Ingeniería, https://doi.org/10.26507/ponencia.1847

- Chafloque-Cespedes, R., Alvarez-Risco, A., Robayo-Acuña, P. V., Gamarra-Chavez, C. A., Martinez-Toro, G. M., & Vicente-Ramos, W. (2021). Effect of sociodemographic factors in entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intention in university students of Latin American business schools. In Universities and entrepreneurship: meeting the educational and social challenges (pp. 151–165). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2040-724620210000011010

- Chan, C. K., & Fong, E. T. (2018). Disciplinary differences and implications for the development of generic skills: a study of engineering and business students’ perceptions of generic skills. European Journal of Engineering Education, 43(6), 927–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2018.1462766

- Chhabra, S., Raghunathan, R., & Rao, N. M. (2020). The antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among women entrepreneurs in India. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-06-2019-0034

- Corazza, G. E., & Agnoli, S. (2020). Openness. In S. Pritzker & M. Runco (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (3rd ed., pp. 338–344). Academic Press.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1988). From catalog to classification: Murray’s needs and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(2), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.2.258

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 6(4), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1992.6.4.343

- da Rocha, A. K. L., Pelegrini, G. C., & de Moraes, G. H. S. M. (2022). Entrepreneurial behaviour and education in times of adversity. Revista de Empreendedorismo e Gestão de Pequenas Empresas, 11(2), 2040–2040.

- Damasio, A. R., & Sutherland, S. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason and the human brain. Nature, 372(6503), 287–287.

- Dana, L. P., Tajpour, M., Salamzadeh, A., Hosseini, E., & Zolfaghari, M. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurial education on technology-based enterprises development: The mediating role of motivation. Administrative Sciences, 11(4), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040105

- Delim, S., Caras, J. A. M., De La Paz, R. M., Kieng, R. U., & Tanpoco, M. (2022). The effects of pre-university entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention as mediated by acquired competencies and mindset. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(8), 3185–3203.

- Díaz-Casero, J. C., Ferreira, J. J. M., Hernández Mogollón, R., & Barata Raposo, M. L. (2012). Influence of institutional environment on entrepreneurial intention: a comparative study of two countries university students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0134-3

- Engle, R. L.,Dimitriadi, N.,Gavidia, J. V.,Schlaegel, C.,Delanoe, S.,Alvarado, I.,He, X.,Buame, S., &Wolff, B. (2010). Entrepreneurial intent. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 16(1), 35–57. 10.1108/13552551011020063

- Estrada Molina, C. M. (2022). Education, employment and entrepreneurship in the third decade of the 21st century accompanied by SENA. Editorial Planeta Colombiana S. A.

- Ewe, S. Y., & Ho, H. H. P. (2022). Transformation of personal selling during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In COVID-19 and the evolving business environment in Asia: The hidden impact on the economy, business and society (pp. 259–279). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2749-2_13

- Farzin, F. (2015). An investigation into the impact of techno-entrepreneurship education on self-employment. International Journal of Economics and Management Engineering, 9(3), 1019–1031. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1109329

- Ferreira, J. J., Raposo, M. L., Gouveia Rodrigues, R., Dinis, A., & do Paço, A. (2012). A model of entrepreneurial intention: An application of the psychological and behavioral approaches. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(3), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211250144

- Fincham, R., & Rhodes, P. (2005). Principles of organisational behaviour (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Fragoso, R., Rocha-Junior, W., & Xavier, A. (2020). Determinant factors of entrepreneurial intention among university students in Brazil and Portugal. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2018.1551459

- Gao, Y., Zhang, D., Ma, H., & Du, X. (2020). Exploring creative entrepreneurs’ IEO: Extraversion, neuroticism and creativity. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02170

- Georgescu, M. A., & Herman, E. (2020). The impact of the family background on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis. Sustainability, 12(11), 4775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114775

- Glen, R., Suciu, C., & Baughn, C. (2014). The need for design thinking in business schools. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 13(4), 653–667. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0308

- Godwin, A., Potvin, G., Hazari, Z., & Lock, R. (2016). Identity, critical agency, and engineering: An affective model for predicting engineering as a career choice. Journal of Engineering Education, 105(2), 312–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20118

- Gomes, S., Santos, T., Sousa, M., Oliveira, J. C., Oliveira, M., & Lopes, J. M. (2022). Entrepreneurial intention among women: A case study in the Portuguese academy. Strategic Change, 31(2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2489

- Goni, R., García, P., & Foissac, S. (2009). The qPCR data statistical analysis. Integromics White Paper, 1, 1–9.

- Greenberg, J. (2011). Behaviour in organisations: Understanding and managing the human side of work. Pearson Education International.

- Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.111

- Guesss. (2022). Key Facts for the GUESSS Project. Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students ‘Survey – Guesss’. https://www.guesssurvey.org/keyfacts/

- Gupta, R. K. (2022). Does university entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship education affect the students’ entrepreneurial intention/startup intention? In Industry 4.0 and Advanced Manufacturing: Proceedings of I-4AM 2022. (pp. 355–365). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0561-2_32

- Hasan, Y., et al. (2020). Factors impacting entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Saudi Arabia: testing an integrated model of TPB and EO. Education + Training, 62(7/8), 779–803. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-04-2020-0096

- He, Y., Donnellan, M. B., & Mendoza, A. M. (2019). Five-factor personality domains and job performance: A second order meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 82, 103848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103848

- Heydari, E., Rezaei, M., Pironti, M., & Chmet, F. (2023). How does owners’ personality impacts business internationalisation in family SMEs?. In Decision-making in international entrepreneurship: Unveiling cognitive implications towards entrepreneurial internationalisation. (pp. 331–347). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80382-233-420231016

- Hossain, M. U., Arefin, M. S., & Yukongdi, V. (2021). Personality traits, social self-efficacy, social support, and social entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2021.1936614

- Huang, J., Wu, J., Deng, B., & Bao, S. (2021). Research on the optimization strategy of innovation behavior and entrepreneurship intention in entrepreneurship teaching. Scientific Programming, 2021, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4872108

- Ilevbare, F. M., Ilevbare, O. E., Adelowo, C. M., & Oshorenua, F. P. (2022). Social support and risk-taking propensity as predictors of entrepreneurial intention among undergraduates in Nigeria. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 16(2), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-02-2022-0010

- Jena, R. K. (2020). Measuring the impact of business management Student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106275

- Jiang, Y., & Stylos, N. (2021). Triggers of consumers’ enhanced digital engagement and the role of digital technologies in transforming the retail ecosystem during COVID-19 pandemic. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 172, 121029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121029

- Jiatong, W., Murad, M., Li, C., Gill, S. A., & Ashraf, S. F. (2021). Linking cognitive flexibility to entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial intention among medical students with the moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A second-order moderated mediation model. PLOS One, 16(9), e0256420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256420