Abstract

The widespread popularity of corporate social responsibility (CSR) within universities has influenced various changes in the higher education sector, affecting the operations of higher education institutions in many developed and developing countries. Using institutional theory, this study explores the connection between university CSR and university brand positioning, specifically focusing on university brand legitimacy. The quantitative findings, gathered from 398 students in Tanzania, indicate that university CSR cultivates a distinct and exclusive perception in the minds of students, who are considered as customers of higher education institutions. The study suggests the implementation of deliberate measures and necessary reforms in the higher education sector by incorporating CSR as a strategic function of the university.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Higher educational institutions, particularly universities in both developing and developed economies, have been undergoing strategic changes in response to pressure from various stakeholders (Amani, Citation2022c; El-Kassar et al., Citation2019; Miotto et al., Citation2020). These stakeholders are increasingly demanding that universities go beyond their traditional roles of teaching, research, and innovation (Lemos Lourenço et al., Citation2022; Miotto et al., Citation2018). They are urging universities to transform into world-class institutions that serve as drivers of social and economic development (Altschwager et al., Citation2018; Amani, Citation2022c; Miotto et al., Citation2020). According to Miotto et al. (Citation2020); and Nabi et al. (Citation2018), stakeholders expect universities to lead as think tanks for their respective countries and catalysts for social and economic development. Additionally, universities are expected to embrace social responsibility and be accountable members of society (Amani, Citation2022c; Wigmore-Álvarez & Ruiz-Lozano, Citation2012). They are seen as engines to achieve sustainable development goals and facilitate innovation (Cuesta-Claros et al., Citation2021; Ferraris et al., Citation2020). However, recent evidence indicates that in their effort to be socially responsible and accountable, universities are confronting economic forces in the global education market, pushing them toward commercial competition (Amani, Citation2022b). The growing competition in the higher education sector necessitates the development of distinct brand identities for universities (Furey et al., Citation2014; Perera et al., Citation2020). Heslop and Nadeau (Citation2010); Perera et al. (Citation2020) argue that, in order to thrive in this competitive landscape, universities consistently adopt positioning strategies to establish unique identification and differentiation. Brand positioning, a marketing strategy, involves offering products or services that aim to occupy an exclusive and distinctive place in the minds of customers when compared to competitors (Akbari et al., Citation2020; Perera et al., 2022). This strategic approach is crucial for universities as it enables them to establish a set of brand associations that resonate with key stakeholders including students. In the competitive educational market, brand positioning has become a cornerstone for building a positive image and perception among key stakeholders including students (Perera et al., Citation2020).

Despite varying perspectives on the pivotal role of brand positioning in cultivating competitiveness within educational markets, universities, primarily in developing nations, struggle with a series of challenges (Amani, Citation2022c). These challenges encompass attracting qualified students, retaining experienced faculty, forging corporate partnerships, and securing essential research grants and funding (Perera et al., Citation2020; Waris et al., Citation2021). The educational landscape is further complicated by the challenging difficulty of substitutability, owing to the inherent similarities and uniformity of universities’ offerings (Amani, Citation2022c; Perera et al., Citation2020; Simiyu et al., Citation2020). This diminishes the potential for differentiation, thereby complicating the task of students as they navigate the densely populated educational market (Miotto et al., Citation2020). In response to these challenges, universities in developing countries have come to recognize brand positioning as a crucial strategy to not only compete but also thrive in the higher education sector (Perera et al., Citation2020). The current landscape within the higher education sector in these regions demands a shift towards alternative strategies to gain a competitive edge. As Renani et al. (Citation2020) properly argue, the contemporary marketplace’s battleground is the minds of consumers, primarily within the realm of branding. However, a significant gap in knowledge exists regarding the development of brand positioning for universities, especially within the context of developing countries. While the existing body of literature extensively explores brand positioning in various sectors such as healthcare (Meese et al., Citation2019), the hospitality industry (Neirotti et al., Citation2016), financial services (Paltayian et al., Citation2012), automobiles (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, Citation2010), and retail (González-Benito & Martos-Partal, Citation2012; Martos-Partal & González-Benito, Citation2011), there is a notable scarcity of information within the higher education domain, particularly regarding the determinants of brand positioning (Perera et al., Citation2020). It is crucial to acknowledge that the drivers of brand positioning from other sectors cannot be indiscriminately applied to the higher education sphere due to the unique nature of the education sector and the operations of universities.

Empirical evidence underscores the pressing need for universities to adapt to the evolving demands and heightened expectations of stakeholders, particularly students (Heffernan et al., Citation2018; Miotto et al., Citation2020). In light of these changing dynamics, it becomes imperative for universities to explore innovative avenues to gain a competitive edge. A study conducted by Amani (Citation2022c) highlights the growing pressure on universities to transcend their traditional roles of teaching and research. In response to this, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) emerges as a promising means to establish a distinctive university identity (El-Kassar et al., Citation2019). University CSR, in this context, pertains to a commitment to ethical excellence in the university’s performance, which involves responsible management of the educational, cognitive, and labor impacts that the university generates (Latif, Citation2018). This approach is carried out through an ongoing dialogue with society, with a focus on fostering sustainable human development (Cuesta-Claros et al., Citation2021; Ferraris et al., Citation2020). Previous research, informed by institutional theory, suggests that organizations and institutions can enhance their corporate reputation by investing in ethical practices aligned with socially constructed norms, values, and beliefs (Yang et al., Citation2021). This opens up a novel pathway for universities to cultivate a unique and compelling identity that can bolster their competitive advantage. Contemporary literature in the higher education sector emphasizes the strategic role of CSR in shaping corporate reputation (El-Kassar et al., Citation2019; Perera et al., Citation2020). CSR offers a comprehensive framework for universities to craft a distinct image and shape the perceptions of their stakeholders (Plungpongpan et al., Citation2016). It encompasses the university’s enduring commitment to ethical conduct, contributing to economic development, and enhancing the quality of life for stakeholders and society at large (Latif, Citation2018). This paradigm implies that a university’s positioning in the higher education landscape should be driven by social acceptance, which is defined in this study as university corporate brand legitimacy (Amani, Citation2022c; Miotto et al., Citation2020). Corporate brand legitimacy is a measure of how well an organization’s activities align with socially constructed norms and values as perceived by society (Miotto et al., Citation2020). Therefore, this study posits an intricate interplay between various dimensions of university CSR, university corporate brand legitimacy, and university brand positioning. The study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: What is the influence of the dimensions of university CSR on university corporate legitimacy?

RQ2: What is the influence of the dimensions of university CSR on university brand positioning?

RQ3: What is the mediating effect of university corporate legitimacy on the relationship between the dimensions of university CSR and university brand positioning?

Literature review and hypotheses development

Stakeholder theory

Stakeholder theory, as proposed by Freeman (Citation1984), identifies the main characteristics that distinguish stakeholders from others. The theory suggests that the success of any organization depends on the extent to which it has identified and engaged with relevant stakeholders who have interests in operations of the organization. It has been developed within the frameworks of systems theory, organization theory, and Corporate Social Responsibility (Freeman, Citation1984; Mainardes et al., Citation2011). According to Freeman (Citation1984), a stakeholder is any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives. A stakeholder plays a crucial role in determining the survival of the organization because they have a stake (Carroll, Citation1993). The stakeholder theory is employed in this study to provide a general understanding of the characteristics of an individual or entity that can be considered a stakeholder in a given setting (Parmar et al., Citation2010). The theory is intended to help define who should be called a stakeholder in different settings and environments (Byrd, Citation2007), providing a theoretical framework for understanding ‘who one is’. The theory rests on four assumptions: First, the focus is on managerial decisions. Second, each stakeholder is affected by or affects the organization’s decisions. Third, the relationship between stakeholders determines the success of both the organization and each stakeholder. Fourth, all stakeholder interests are considered equally important, with no single interest dominating the others. Therefore, these assumptions suggest that for a person or organization to be considered a stakeholder, they must be in a position to affect or be affected by anything undertaken within the organization.

Institutional theory

The theoretical underpinning of this study draws from institutional theory, a sociological perspective widely used to elucidate how external factors influence an organization’s decision-making processes (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977). According to institutional theory, organizations exist within a broader societal context and are subject to the influence of societal norms, expectations, and values. Institutional theorists argue that organizations should be regarded as corporate citizens with specific responsibilities, accountable for their actions (Bruton et al., Citation2010; Massi et al., Citation2021). It posits that organizations pursuing social acceptance face various institutional pressures stemming from sources like regulatory bodies advocating industry standards and societal expectations (Bruton et al., Citation2010). This theory suggests that organizations that respond to these institutional pressures are perceived as legitimate and are more likely to gain a competitive advantage. As highlighted by Krell et al. (Citation2016), when organizations align their actions and behaviors with institutional pressures, they tend to establish credibility, trust, and legitimacy, ultimately contributing to a positive corporate reputation. This study adopts the theoretical framework of institutional theorists to argue that universities embracing CSR can attain social acceptance, a critical element in achieving optimal university brand positioning. From a theoretical perspective, the study suggests that legitimacy can be achieved by conforming to societal norms and expectations, delivering high-quality products or services, and engaging in socially responsible behavior, such as CSR. Massi et al. (Citation2021) posit that within the institutional theory framework, legitimacy empowers universities to fulfill their duties and responsibilities while gaining the support of external and internal stakeholders, including students, by creating value propositions through university brand positioning.

University corporate brand legitimacy

The concept of corporate legitimacy has become a focal point of attention in the realm of educational marketing research (Miotto et al., Citation2020). Corporate legitimacy refers to the degree to which an organization’s activities and actions are perceived as fitting within a socially constructed framework of norms, values, and beliefs by members of society (Payne et al., Citation2021). It’s essentially a reputational asset that has the potential to bolster an organization’s goodwill and contribute significantly to its competitive advantage (Miotto & Youn, Citation2020). In today’s fiercely competitive market, organizations must actively work to acquire legitimacy by aligning their corporate behaviors with the aim of ensuring the long-term survival of the corporation (Amani, Citation2022c). University corporate brand legitimacy pertains to how well a university’s actions and practices conform to the expectations, values, norms, and regulations of societal and regulatory bodies (Latif, Citation2018; Wigmore-Álvarez & Ruiz-Lozano, Citation2012). Institutional theorists posit that institutions can sustain their legitimacy by actively engaging in socially responsible practices (Massi et al., Citation2021). In this context, universities characterized by a high degree of legitimacy are seen as institutions that make meaningful contributions to society, are responsive to the needs and expectations of their stakeholders, and adhere to practices that are in harmony with socially constructed norms, values, and beliefs (Amani, Citation2022c; Miotto et al., Citation2020). In today’s educational landscape, key stakeholders demand that universities not only provide quality education but also demonstrate social accountability and responsibility (Miotto et al., Citation2018). Empirical evidence underscores the acceptance of CSR practices among diverse stakeholders as an integral component of ethical conduct. CSR encompasses a range of actions that organizations undertake to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights, and stakeholder considerations into their core operations and fundamental strategies, often in close partnership with their stakeholders.

University corporate social responsibility

CSR embodies the practice of self-regulation that organizations adopt to ensure their alignment with widely accepted ethical principles and standards within society (Ruiz & García, Citation2021). From an institutional theory perspective, CSR reflects an organization’s commitment to conforming to societal norms, values, and expectations by integrating ethical and socially responsible practices into their core strategic functions (Amani, Citation2022c). The concept of university CSR specifically pertains to a policy focused on upholding ethical standards within the university community, which includes students, faculty members, and alumni (Carrillo‐Durán et al., Citation2023; Latif, Citation2018; Vasilescu et al., Citation2010). This commitment extends to the responsible management of the educational, cognitive, labor, and environmental impacts generated by the university, coupled with active engagement in dialogues with society to promote sustainable human development (El-Kassar et al., Citation2019; Latif, Citation2018; Vasilescu et al., Citation2010). Notably, it is emphasized that universities should exceed their core responsibilities of education, research, and community outreach (Miotto et al., Citation2018; Miotto et al., Citation2020). Universities, functioning as both think tanks and catalysts for social and economic development, take on a proactive role in ensuring the continuity of sustainable development (Cuesta-Claros et al., Citation2021; Vasilescu et al., Citation2010). University CSR encompasses various elements, including engagement with the community, ethical standards, responsibilities towards internal stakeholders, compliance with legal obligations, effective operational practices, philanthropic contributions, and the encouragement of research and development (Latif, Citation2018).

Community engagement responsibility

Research in the field of university CSR reveals that universities have the potential to create innovative solutions for societal challenges by collaborating with their local communities (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021; Latif, Citation2018). It is imperative for universities to establish strategic mechanisms for engaging with their communities to determine and enhance social welfare and well-being (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021; Chile & Black, Citation2015). Utilizing community engagement as a method for fostering connections with society, universities can adopt a collaborative approach to address societal issues and challenges. Previous research emphasizes that effectively communicating this engagement responsibility is one of the most critical components of CSR, as it plays a key role in shaping the distinctive identity of a university (Latif, Citation2018; Plungpongpan et al., Citation2016). Institutional theorists suggest that community engagement allows organizations, in this case, universities, to work in collaboration with members of society to achieve inclusive development that positively impacts both society and the institution itself (Bruton et al., Citation2010). Research within the CSR domain highlights that community engagement positions universities as active members of society, demonstrating their commitment to collaborating with other community members to achieve inclusive development (Saidi, Citation2021). From this perspective, community engagement serves to enhance the university’s legitimacy within society, bolstering its moral authority as a driver of both social and economic development (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021; Miotto et al., Citation2018). Consequently, this study hypothesizes that

H1: Community engagement responsibility influences university corporate brand legitimacy.

H1a: Community engagement responsibility influences university brand positioning.

Ethical responsibility

Ethical responsibility stands as a pivotal component of CSR, championing the significance of aligning with social norms and standards to bolster organizational performance (Latif, Citation2018; Lemos Lourenço et al., Citation2022). It encompasses an organization’s capacity to identify, interpret, and act upon diverse principles and values within the framework of specific fields or contexts (Cezarino et al., Citation2022). Many consider ethical responsibility to be an organization’s unwavering commitment to conducting its affairs in an ethical manner, upholding the principles of human rights, and ensuring fair treatment for all stakeholders, while practicing equitable principles that benefit society as a whole (Kim et al., Citation2018; Latif, Citation2018; Taamneh et al., Citation2022). This goes beyond mere compliance with laws and regulations, extending into a moral-driven approach to business operations. Institutional theorists assert that organizations operate within the broader tapestry of societal influences, encompassing norms, expectations, and values (Krell et al., Citation2016). Similarly, universities, like other organizations, face mounting pressure from stakeholders to integrate societal norms and values into their operations (Amani, Citation2022c; Blanco-González et al., Citation2021). Research exploring the nexus between corporate reputation and ethical conduct underscores the pivotal role of ethical responsibility in forging a competitive advantage (Miotto et al., Citation2018; Miotto et al., Citation2020). Therefore, this study postulates that

H2: Ethical responsibility influences university corporate brand legitimacy.

H2a: Ethical responsibility influences university brand positioning.

Internal stakeholder responsibility

Universities rely on a diverse set of stakeholders who play a pivotal role in their growth and development (Latif, Citation2018; Miotto et al., Citation2018). In today’s fiercely competitive educational landscape, internal stakeholders, including students, are valuable partners, crucial for helping universities realize their missions and visions (Amani, Citation2022a). Internal stakeholders comprise those individuals within an organization who have a vested interest due to their direct access to its services or products, ownership, or investment (Latif, Citation2018). According to institutional theorists, both internal and external stakeholders exert substantial influence on an organization’s decision-making processes (Massi et al., Citation2021). El-Kassar et al. (Citation2019); Miotto et al. (Citation2020) reinforces this perspective, emphasizing that internal stakeholders within a university possess the potential to enhance the university’s brand value, thereby elevating the institution’s overall prestige. This underscores the importance of universities considering the interests and needs of internal stakeholders, especially students, to garner legitimacy and societal acceptance (Miotto et al., Citation2020). Numerous research avenues corroborate that internal stakeholders, particularly students, are the primary source of legitimacy for universities. Their endorsement provides moral authority, enabling universities to assume pivotal roles and responsibilities as catalysts for social and economic development in the broader community (Amani, Citation2022c). Recognizing the responsibility, they hold toward internal stakeholders, universities should actively engage in enhancing the social and academic experiences of their students. This commitment fosters students’ intentions to support the universities’ future development (Latif, Citation2018). As such, this study posits the following hypotheses

H3: Internal stakeholder responsibility influences university corporate brand legitimacy.

H3a: Internal stakeholder responsibility influences university brand positioning.

Legal responsibility

Universities, as integral entities within the higher education sector, must adhere to the legal procedures mandated by regulatory bodies (Miotto et al., Citation2018). Their adherence to these legal requirements is a critical factor in establishing and maintaining their legitimacy (Amani, Citation2022c). According to institutional theorists, organizations capable of effectively managing institutional pressures, including legal compliance in the higher education sector, are deemed legitimate and are better positioned to gain a competitive advantage (Jeong & Kim, Citation2019). Legal responsibilities encompass the extent to which an institution follows existing laws, regulations set forth by regulatory bodies, and the bylaws of specific communities (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2021; Latif, Citation2018). This facet of legal responsibility is a fundamental component of CSR that underscores an organization’s commitment to being responsible and accountable to society. As Lemos Lourenço et al. (Citation2022) articulate, legal responsibility seeks to define the organization’s willingness to be accountable and responsible for its actions and practices, demonstrating its commitment to being responsive and respectful toward society. Previous research in the higher education sector has consistently shown that compliance with laws and regulations mandated by regulatory bodies plays a pivotal role in enhancing a university’s reputation and ensuring its survival in the fiercely competitive educational landscape (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021; Miotto et al., Citation2020). In light of these explanations, this study posits that

H4: Legal responsibility influences university corporate brand legitimacy.

H4a: Legal responsibility influences university brand positioning.

Operational responsibility

Operational CSR, often defined as the set of initiatives championed by organizations to enhance efficiency and performance, plays a pivotal role in driving significant positive impacts on both the social and economic changes of society (Latif, Citation2018). Institutional theorists assert that the very essence of an organization’s existence lies in the continual enhancement of its efficiency and performance, consequently contributing to the greater welfare and well-being of society (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977). Recent research findings by Miotto et al. (Citation2020) have underscored that organizations, which diligently improve their efficiency and performance while considering the interests of their stakeholders, are perceived as more accountable and responsible. This concept has resonated throughout various sectors, including higher education, where stakeholders are vocally demanding consistent improvements in the efficiency and performance of universities (Cuesta-Claros et al., Citation2021; Miotto et al., Citation2020; Plungpongpan et al., Citation2016). Operational responsibility, which prioritizes the enhancement of efficiency and performance, not only fosters student satisfaction but also aligns with the expectations of external stakeholders (Latif, Citation2018). Consequently, universities must passionately embrace their operational responsibilities to attain top performance and maintain their legitimacy (Miotto et al., Citation2018). Institutional theorists argue that an organization’s core purpose is continual improvement, benefitting society (Fernando & Lawrence, Citation2014). In higher education, stakeholders demand university efficiency for societal advancement. Operational responsibility, aligned with stakeholder expectations, heightens student satisfaction and external stakeholder approval. Universities must embrace operational responsibilities for better performance and legitimacy (Miotto et al., Citation2020). This study thus hypothesizes that

H5: Operational Responsibility Influences University Corporate Brand Legitimacy.

H5a: Operational Responsibility Influences University brand positioning.

Philanthropic responsibility

Universities should actively demonstrate their engagement with society by engaging in voluntary activities aimed at improving social welfare and overall well-being (Latif, Citation2018). Institutional theorists emphasize that organizations, as integral members of society, must show a deep commitment to both the social and economic well-being of their communities (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977). The concept of philanthropic responsibility underscores an organization’s obligation to contribute to and support communities through acts of charity, volunteerism, and active participation within the community (Chan et al., Citation2021). As per Atakan and Eker (Citation2007), philanthropic efforts have the potential to address diverse issues, including education, healthcare, and social welfare. According to Sulek (Citation2010) the term ‘philanthropy’ originates from the Greek words ‘philein’, signifying love or care, and ‘antropos’, representing humanity. In this context, any philanthropic initiative should reflect an organization’s genuine desire to support the community, demonstrating passion, compassion, and love (Latif, Citation2018). Research in the field of education development indicates that key stakeholders in the education sector expect universities to actively participate in social events and projects that aim to uplift underprivileged communities (Miotto et al., Citation2020). Amani (Citation2022c) argues that universities which fulfill their responsibilities and meet societal expectations are more likely to receive social acceptance and approval from key stakeholders, including students. Miotto et al. (Citation2018) further contend that in the current educational landscape, universities are expected to build a distinctive image by engaging in activities that enhance social value for stakeholders. Research in education marketing suggests that voluntary activities have a direct impact on promoting loyalty and garnering positive recommendations from stakeholders, including students and alumni (Tan et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the study hypothesizes that:

H6: Philanthropic responsibility influences university corporate brand legitimacy.

H6a: Philanthropic responsibility influences university brand positioning.

Research-development responsibility

The responsibility for research and development plays a pivotal role in enhancing an organization’s innovation and growth (Cuesta-Claros et al., Citation2021). This perspective is strongly supported by institutional theory, which underscores the importance of organizations ensuring that society derives maximum value from their operations and practices (Gupta & Gupta, Citation2021). In the context of the higher education sector, universities are expected to function as intellectual powerhouses, where novel solutions to societal challenges and problems are sought (Cuesta-Claros et al., Citation2021; Miotto et al., Citation2020). Research and development responsibility encompasses a range of innovative activities undertaken by universities with the explicit purpose of discovering fresh solutions to the social and economic challenges faced by society (Ferraris et al., Citation2020). Research and development as a component of CSR, it involves not just conducting research but also translating and integrating the outcomes into the creation of novel ideas (Miotto et al., Citation2020). It reflects a university’s commitment to ensuring that its primary functions, including research, directly contribute to the social and economic development of society. Previous studies have consistently shown that investment in research and development is a driving force behind the establishment of world-class universities (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021). As Miotto et al. (Citation2018); Miotto et al. (Citation2020) suitably argue, innovation through research and development has played a central role in enhancing the global reputation of many universities. Therefore, this study puts forth the hypotheses that

H7: Research-development responsibility influences university corporate brand legitimacy.

H7a: Research-development responsibility influences university brand positioning.

University brand positioning

In competitive environments, brand positioning has garnered increased attention as a pivotal tool for gaining a competitive advantage by crafting a unique value proposition (Perera et al., Citation2020). Organizations that embrace brand positioning as a strategic tool seek to carve out a distinctive niche in their customers’ minds. The ultimate goal of brand positioning is to construct a customer-centric value proposition. This customer-focused value proposition should be fortified by compelling and well-substantiated arguments that shed light on the reasons why target customers choose these offerings (Akbari et al., Citation2020; Perera et al., Citation2020). Perera et al. (Citation2020) conceives brand positioning as the art of designing an organization’s offerings with a keen focus on securing a unique and enduring place in the hearts and minds of customers. Scholars such as Meese et al. (Citation2019) have defined positioning as either offering distinctly different products from competitors or delivering similar products in unique and novel ways. In a fiercely competitive marketplace, positioning evolves into a valuable organizational asset that proves difficult for others to replicate or supplant. Research in the field of brand positioning suggests that a successful positioning strategy encompasses defining what a brand represents (Gaustad et al., Citation2018), highlighting its distinctiveness (Perera et al., Citation2020), emphasizing its differentiation from competing brands (Batra et al., Citation2017), and elucidating the reasons why customers should opt for a specific brand (Sharma et al., Citation2016). Brand positioning is of paramount importance for institutions within the higher education sector, especially universities, as it empowers them to carve out a unique and lasting presence in the minds of prospective students, retain existing students and faculty members, and cultivate meaningful partnerships with corporate stakeholders (Perera et al., Citation2020).

University brand positioning is of utmost importance in addressing the contemporary challenges within the higher education sector (Perera et al., Citation2020; Simiyu et al., Citation2020). These challenges impact universities as they strive to attract well-qualified students, esteemed faculty members, and valuable corporate partnerships (Amani, Citation2022c). However, it is essential to note that the higher education sector has been somewhat slow to adopt the principles of brand positioning (Perera et al., Citation2020), despite its prevalence in various other industries (Alwi et al., Citation2020; Amani, Citation2022c). According to Gaustad et al. (Citation2018), brand positioning goes beyond focusing on product innovation and instead emphasizes reshaping consumer perceptions to establish a unique identity that distinguishes an organization’s brand from its competitors. Traditionally, positioning strategies have centered around marketing communication such as advertising and data-driven activities. Yet, Alwi et al. (Citation2020) argues that positioning in higher education should be understood more broadly, encompassing organization-wide processes necessary for developing and communicating the institution’s identity to stakeholders, including students and faculty members. Amani (Citation2022c) promotes a process-oriented approach to developing and managing an organization’s positioning strategies. This study contends that among these process-oriented approaches, CSR holds particular promise for universities in today’s environment, where ethical behavior and sustainability practices are increasingly significant to stakeholders (El-Kassar et al., Citation2023). In a process-oriented approach, CSR involves the integration of ethical and sustainable practices into all aspects of an institution’s operations, from strategic planning to day-to-day activities, with the goal of generating positive societal impacts. In competitive landscapes where universities face mounting pressure to extend their roles beyond traditional teaching and research functions, CSR emerges as a viable means to create a distinctive institutional identity (Vázquez et al., Citation2016). El-Kassar et al. (Citation2023); Tan et al. (Citation2022); Vázquez et al. (Citation2016) suggests that for a university to attain world-class status beyond conventional boundaries, it must operate as a socially responsible and accountable entity. Therefore, this study posits the following hypotheses

H8: University corporate brand legitimacy influences university brand positioning.

H9a: University corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between community engagement responsibility and university brand positioning.

H9b: University corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between ethical responsibility and university brand positioning.

H9c: University corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between internal stakeholder responsibility and university brand positioning.

H9d: University corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between legal responsibility and university brand positioning.

H9e: University corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between operational responsibility and university brand positioning.

H9f: University corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between philanthropic responsibility and university brand positioning.

H9g: University corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between research-development responsibility and university brand positioning.

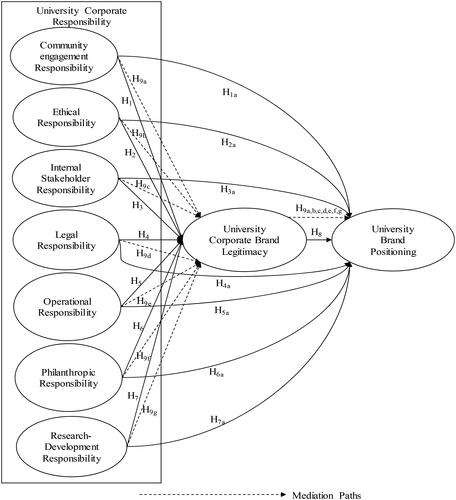

Conceptual model

The conceptual model presented in serves as a concise synthesis of the proposed hypotheses in this study. This conceptual model is rooted in institutional theory and stakeholder theory, which posits that organizations operate within a broader societal framework, subject to the influence of societal norms, expectations, and values. Consequently, this study postulates that the dimensions of university CSR define a specific societal sphere shaped by these societal norms, values, and stakeholder expectations. Furthermore, the study suggests that when universities operate in alignment with this societal sphere, they can garner social acceptance, exemplified by corporate legitimacy. This, in turn, empowers universities to establish a unique position in the minds of their stakeholders, thereby enhancing their brand positioning.

Measures and questionnaire development

The study employed a comprehensive approach to measure various dimensions within the fields of corporate social responsibility, corporate legitimacy, and brand positioning. To ensure the study’s alignment with existing literature, it relied on established and validated scales known for their proven validity and reliability. Multiple items were utilized, a common practice in social sciences research, to minimize measurement errors and encompass a wide array of variable attributes (Churchill, Citation1979). In gauging respondents’ attitudes and emotional reactions toward specific concepts, the study utilized semantic differential questions or scales, a widely accepted rating system in surveys (Osgood, Citation1964). This approach is particularly suitable for social research as it guides respondents toward a specific scale, reducing the potential for non-responses compared to an open-ended approach. All participants’ responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1, signifying strongly disagree, to 5, indicating strongly agree (Likert et al., Citation1934). The measurement of university corporate social responsibility encompassed dimensions such as community engagement responsibility (3 items), ethical responsibility (3 items), internal stakeholder responsibility (5 items), legal responsibility (5 items), operational responsibility (5 items), philanthropic responsibility (3 items), and research and development responsibility (3 items). These dimensions were assessed using scales sourced from (Amani, Citation2022c; Latif, Citation2018). Likewise, the evaluation of university corporate legitimacy (6 items) drew from established measures (Amani, Citation2022c; Miotto et al., Citation2020), while the assessment of university brand positioning (5 items) relied on scales from (Perera et al., Citation2020).

Methodology

Study setting

The research was carried out in the Dodoma region, which serves as the capital of Tanzania. This region is centrally located in Tanzania and is home to six prominent higher education institutions. Notably, among these institutions, one stands out as one of the largest universities in East and Central Africa, both in terms of student enrollment and the breadth of academic programs it offers. The primary focus of the study was on two universities situated in the Dodoma region. The selection of these universities was based on two main criteria: (1) the total number of enrolled students and (2) the variety of degree programs they offer. For this study, a quantitative cross-sectional survey design was employed. This approach aimed to establish causal relationships between specific variables within the hypothesized model (Cummings, Citation2014). Additionally, data collection occurred during a designated time period, without any intention of conducting the same study again to track changes that might occur after specific interventions (Saunders et al., Citation2007).

Population and sampling procedures

The study’s population encompassed students enrolled in higher education institutions within the Dodoma region. To create an effective sample for the study, a stratified sampling approach was implemented. This methodology proves especially advantageous when dealing with a diverse study population, as it strives to guarantee adequate representation of every distinctive characteristic within the sample (Saunders et al., Citation2009; Zikmund et al., Citation2009). The sample determination process involved the following key steps: Firstly, the population was partitioned into homogeneous sub-populations, referred to as strata. These strata were defined based on the various academic programs pursued by the students in their respective institutions. The selection of strata based on degree programs aimed to ensure that every individual within the population belonged to precisely one stratum. Secondly, within each stratum (corresponding to different degree programs), a simple random sampling method was applied. This method facilitates the calculation of statistical measures for each stratum.

Data collection procedures

Data from 398 respondents were gathered through a self-administered survey questionnaire between April and May 2023. This sample size sufficiently ensures the robustness of the findings in multivariate data analysis, particularly in the context of partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), the method employed for data analysis in this study (Hair et al., Citation2019; Sarstedt et al., Citation2019). A pretesting phase was undertaken to confirm the questionnaire’s clarity and content. In this phase, 50 respondents were selected to participate, and they were intentionally not included in the final study sample. This decision aligned with the guidance of Perneger et al. (Citation2015), who recommended excluding data from participants involved in the pretesting phase to ensure the final dataset remained free of measurement errors identified during questionnaire improvement. The pretesting results did not uncover any significant issues or challenges, and consequently, no changes were made to the questionnaire. During the full-scale survey, the questionnaires were randomly distributed to respondents within each stratum. To enhance the response rate, a drop-off/pick-up approach was employed in questionnaire administration (Junod & Jacquet, Citation2023).

Data analysis and results

Common method bias

This study used a self-reporting approach in which both the independent and dependent variables are measured within one survey, using the same response method. This approach may pose a concern regarding common method bias in the collected data. Common method bias (CMB) has several effects including errors when estimating the relationships between the variables of interest in the study (Fuller et al., Citation2016). To address this issue, the study has implemented both procedural and statistical measures. Procedurally, steps were taken to ensure the anonymity and confidentiality of respondents, and it was emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers to the survey items. Additionally, statistical remedies were employed to examine CMB. The specific statistical remedy used was Harman’s single-factor test. All underlying factors were subjected to exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with a single rotation to identify the dominant factor (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). The results indicate that no single factor accounts for more than 50% of the total variance, suggesting that CMB was not detected in the collected data.

Measurement model

The reflective measurement model underwent a comprehensive assessment for both validity and reliability through an analysis of key metrics, including the composite reliability coefficient, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α), factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratios, employing the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) technique. The results, as illustrated in , showcase the robustness of the model. The composite reliability values for all constructs fall within the range of 0.729 to 0.894, consistently surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Similarly, the Cronbach alpha coefficients range from 0.711 to 0.894, also exceeding the 0.7 benchmark (Cronbach & Shavelson, Citation2004). This robust performance of both composite reliability and Cronbach alpha coefficients strongly supports the notion that the construct reliability is indeed acceptable. Turning our attention to the factor loadings, the values range from 0.717 to 0.850, all comfortably exceeding the 0.7 threshold (Sarstedt et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the AVE values, ranging from 0.59 to 0.653, surpass the commonly accepted threshold of 0.5 (Valentini et al., Citation2016). The strong factor loadings and AVE values together offer compelling empirical evidence of convergent validity. Discriminant validity was rigorously examined using the HTMT ratio and Fornell and Larcker’s criterion. According to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square root of AVE for each construct was compared with inter-construct correlations (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The outcomes, as presented in , demonstrate that the square root of AVE for each specific construct consistently exceeds the correlation with any of the other constructs. In addition, the HTMT ratios, detailed in , all remain comfortably below the 0.90 threshold (Ab Hamid et al., Citation2017). Together, these results from both the Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT ratio analyses provide strong empirical support for discriminant validity. Moreover, the study included an evaluation of multicollinearity among indicators, with variance inflation factors ranging from 1.364 to 1.921. Importantly, these values are substantially below the recommended threshold of 5, affirming the absence of significant multicollinearity concerns (Hair et al., Citation2020).

Table 1. Measurement model validation results.

Table 2. Discriminant validity using Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Table 3. Discriminant validity using Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratios.

Structure model and hypotheses testing

The study employed the bootstrapping technique within SmartPLS 4.0 to scrutinize the structural model. This assessment encompassed effect size (f2), coefficient of determination (R2), predictive relevance (Q2), path coefficients, and their associated significance. Notably, the f2 values for community engagement, ethical responsibility, internal stakeholder responsibility, legal responsibility, operational responsibility, philanthropic responsibility, and research and development responsibility on university corporate brand legitimacy were 0.27, 0.39, 0.42, 0.29, 0.32, 0.37, and 0.47, respectively. Leveraging Cohen (Citation1988) recommendations, these values indicated substantial impact. Furthermore, university corporate brand legitimacy’s effect size on university brand positioning was 0.26. These findings affirmed the substantial influence of university corporate social responsibility dimensions on brand legitimacy. The R2 values aligned with substantial and moderate predictive power, registering at 0.481 for university corporate brand legitimacy and 0.430 for university brand positioning (Chin, Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2017). The predictive relevance (Q2) corroborated the structural model’s quality, with endogenous variables exceeding zero (Chin, Citation2010; Hair et al., Citation2019). The hypothesis testing results, presented in , depicted path coefficient estimates ranging from 0.058 to 0.656, with nine hypotheses showing significant results at a 5% level of significance and six hypotheses remaining unsupported. Specifically, community engagement responsibility, ethical responsibility, internal stakeholder responsibility, and legal responsibility were confirmed to positively influence university corporate brand legitimacy and university brand positioning (supporting hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4, 1a, 2a, 3a and 4a), while operational responsibility, philanthropic responsibility, and research-development responsibility exhibited insignificant influence on university corporate brand legitimacy and university brand positioning, thereby not supporting hypotheses 5, 6, 7, 5a, 6a and 7a). Furthermore, the results in demonstrated that university corporate brand legitimacy positively impacted university brand positioning, supporting hypothesis 8.

Table 4. Parameters estimation.

Mediation analysis

The set of hypotheses was considered in testing the mediation effect of corporate brand legitimacy on the relationship between dimensions of university corporate responsibility and university brand positioning. Hypothesis 9a of the study proposed that corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between community engagement responsibility and university brand positioning. This hypothesis was supported (βCER→UBL→UBP = 0.121; t-statistics > 1.96; 95% CI = 0.039 to 0.198). Additionally, hypothesis 9b suggested that corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between ethical responsibility and university brand positioning. This hypothesis was also supported (βETR→UBL→UBP = 0.082; t-statistics > 1.96; 95% CI = 0.012 to 0.161). The results in confirmed hypothesis 9c, which proposed the mediation role of corporate brand legitimacy in the relationship between internal stakeholder responsibility and university brand positioning (βISR→UBL→UBP = 0.132; t-statistics > 1.96; 95% CI = 0.055 to 0.208). Furthermore, the results in supported hypothesis 9d, which hypothesized the mediation role of corporate brand legitimacy in the relationship between legal responsibility and university brand positioning (βLGR→UBL→UBP = 0.102; t-statistics > 1.96; 95% CI = 0.035 to 0.178). Hypothesis 9e speculated that corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between operational responsibility and university brand positioning. However, the hypothesis was not supported (βOPR→UBL→UBP = 0.080; t-statistics < 1.96; 95% CI = 0.001 to 0.163), as presented in . The results in indicate that hypothesis 9f, which hypothesized that the relationship between philanthropic responsibility and university brand positioning is mediated by university corporate brand legitimacy, was not supported (βPHR→UBL→UBP = 0.038; t-statistics < 1.96; 95% CI = - 0.026 to 0.106). Finally, in hypothesis 9 g, the study proposed that university corporate brand legitimacy mediates the relationship between research and development responsibility and university brand positioning. The results in did not support this hypothesis (βRDR→UBL→UBP = 0.050; t-statistics < 1.96; 95% CI = −0.026 to 0.128).

Table 5. Parameter estimation: mediation analysis.

Discussion

This study delved into the impact of university CSR on university brand positioning, specifically through the lens of university corporate brand legitimacy. Consequently, the discourse on these findings revolves around the theoretical foundation that university CSR represents a category of ethical practices capable of eliciting support from various stakeholders, including students. Among the array of findings, this study establishes that social acceptance, in the form of university corporate brand legitimacy, stands as an indispensable element in crafting value propositions, which, in turn, determine university brand positioning. These findings gain substantial support from the work of Miotto et al. (Citation2020), who underscores that, when an institution garners legitimacy from its stakeholders, its reputation can surpass that of competitors within the same sector or industry. The research also highlights that universities, by engaging in community involvement and responsibility, are able to motivate stakeholders, including students, to bestow legitimacy upon the university brand. Community engagement responsibility empowers universities to manifest their role as active members of society, bearing a collective responsibility to collaborate with stakeholders in driving social and economic development. The findings are corroborated by Blanco-González et al. (Citation2021), who emphasizes that community engagement represents a pivotal strategic component that situates universities at the forefront of advancing the agenda of social and economic development.

Furthermore, the research findings underscore the influential role that adherence to societal norms and values plays in motivating key stakeholders, particularly students, to cultivate social acceptance and legitimacy. These results corroborate the institutional theory affirming that when an organization aligns itself with the prevailing social norms and values accepted by society, it paves the way for garnering widespread social approval (Massi et al., Citation2021). In essence, a university, as an integral part of society, bears a responsibility to uphold and preserve these social norms and values, which are indispensable elements in formulating compelling value propositions within the fiercely competitive educational landscape (Amani, Citation2022c; Latif, Citation2018). Universities must consistently demonstrate honesty, transparency, and fairness in all their undertakings to craft robust positioning strategies that yield a competitive advantage (Miotto et al., Citation2018; Miotto et al., Citation2020). Past research by Carrillo‐Durán et al. (Citation2023) further underscores the notion that universities, as societal members, must harmonize their actions with prevailing social norms and standards to position themselves as leading agents of social welfare and well-being. Furthermore, the study’s findings illuminate the fact that treating stakeholders, particularly students, with respect and attentiveness to their expectations can expedite the attainment of social acceptance (Chan et al., Citation2021). This, in turn, can pave the way for securing a competitive edge through effective brand positioning (Perera et al., Citation2020). Within the competitive landscape of higher education, internal stakeholders such as students are invaluable assets for universities aiming to thrive. This insight is reinforced by Amani (Citation2022c); Latif (Citation2018), who emphasizes that a university’s corporate image is shaped and upheld by students who have experienced respect and dignity in their interactions with the institution and its faculty members.

The research findings have shed light on the critical importance of universities adhering to legal procedures set by regulatory bodies within the higher education sector as a means to establish a competitive advantage through effective positioning. It is imperative for universities to exhibit a high level of academic integrity and professionalism in their operations. This not only garners legitimacy and social acceptance from key stakeholders, including students, but also forms a solid foundation for crafting compelling value propositions (El-Kassar et al., Citation2023; Jongbloed et al., Citation2008). These results align with the views of Amani (Citation2022c); Latif (Citation2018), who emphasized that compliance with the legal framework governing higher education demonstrates a university’s commitment to responsible, accountable membership within society and its governing bodies. Conversely, the study has yielded unexpected outcomes for three hypotheses, challenging the prevailing literature in the higher education sector, particularly in developed nations. Surprisingly, the research suggests that the operational aspects of a university, when considered as part of CSR, do not significantly impact social acceptance and competitive advantage through university brand positioning. This contrasts with the majority of studies in developed countries that highlight operational responsibility as a crucial tool in enhancing a university’s reputation (Carrillo‐Durán et al., Citation2023; Latif, Citation2018). However, in line with previous research in developing countries, the findings revealed operational matters, including educational quality, as a critical challenge for universities in emerging economies (Amani, Citation2022c). For example, the study by Mogaji et al. (Citation2022) underscores the pressing need for universities in developing countries to improve service delivery, learning conditions, and foster freedom of expression among students and faculty members. Furthermore, the study’s results do not support the idea that philanthropic activities contribute substantially to building a competitive positioning through legitimacy. This stands in contrast to the prevailing literature in developed countries, where universities often engage in consistent voluntary efforts aimed at promoting societal well-being and welfare (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021).

On the contrary, in developing countries, universities have tended to overlook voluntary philanthropic activities and often perceive them as the exclusive domain of non-profit organizations (Amani, Citation2022c). This oversight suggests that universities in developing nations are missing a valuable opportunity to bolster their societal standing, potentially paving the way for them to establish a competitive edge through strategic positioning. These findings are reinforced by the perspective of Kamal (Citation2021); Uzochukwu et al. (Citation2016), who contends that a substantial disconnect between society and universities in developing countries hampers these institutions’ ability to make meaningful contributions to social and economic progress within their communities. Moreover, the study indicates that research and development programs in these universities are not typically utilized as a means to promote corporate legitimacy, nor as a tool for enhancing their competitive advantage through brand positioning. In the realm of higher education, research and development stands as a critical pillar of university operations (Ndiango et al., Citation2023a). Universities are expected to view research and development as a strategic imperative, serving as both the rationale for their existence and as the driving force behind their contributions to social and economic advancement (Ndiango et al., Citation2023b). These findings stand in stark contrast to the prevailing narrative in developed countries, where research and development are commonly perceived as essential tools that enable universities to demonstrate their unparalleled role in fostering social and economic progress (Miotto et al., Citation2020). However, it is worth noting that these findings find support in studies from developing countries, which frequently highlight the limited emphasis on research and development activities among the majority of universities (Ndiango et al., Citation2023a). Furthermore, this study reveals that universities in developing countries often allocate insufficient resources and attention to promoting research and development despite its crucial role in justifying their contributions to the social and economic development of developing economies. The study by Cuesta-Claros et al. (Citation2021) reinforces these results, emphasizing that universities in developing nations could significantly enhance their impact on social and economic development if they made more substantial investments in research and development endeavors.

Theoretical recommendation

CSR has been extensively examined in various sectors, including its growing adoption within the higher education domain, particularly among universities. While some research has explored how CSR affects university performance, there’s limited evidence on its impact on university branding. This study aims to empirically test a conceptual model that investigates how university CSR influences university brand positioning, with a focus on university corporate brand legitimacy. The study’s findings contribute theoretical insights by shedding light on the role of university CSR in strengthening a university’s brand positioning. Drawing from institutional theory and stakeholder theory, the study suggests that universities that embrace CSR can attain social acceptance, a crucial factor in achieving an optimal university brand positioning. Furthermore, the study advances theoretical knowledge by highlighting that legitimacy can be achieved by adhering to societal norms and expectations, delivering high-quality products or services, and engaging in socially responsible practices, such as CSR. In essence, the study proposes a theoretical framework rooted in institutional theory and stakeholder theory, suggesting that legitimacy empowers universities to fulfill their responsibilities and gain support from both internal and external stakeholders, including students. This is achieved by creating value propositions in the form of university brand positioning.

Managerial recommendation

The study underscores the need for essential reforms and transformations within universities, primarily in developing countries, to fully embrace CSR as an integral part of their core operations. The study recommends establishing and strengthening specific units or departments responsible for outreach programs, including CSR programs. These units and departments should encompass personnel who have been well-equipped and trained to handle CSR programs, which could have a strategic impact on the community and the university’s corporate brand. These units or departments should be given the mandate to propose and design relevant and appropriate CSR programs that can improve university participation in ensuring the social and economic well-being of societies. Furthermore, university management should establish metrics or Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to evaluate the impact of CSR programs on the community, as well as university growth and development. These metrics could include the social and economic impact of CSR programs, the contribution of CSR programs to promoting societal goals, diversity and inclusion metrics such as gender and ethnicity representation, philanthropic contributions such as financial donations, volunteer hours, and community engagement initiatives, and customer satisfaction metrics measuring the impact of CSR efforts on the corporate reputation of the university. The study recommends that university management use a participatory approach to engage key stakeholders in proposing, designing, and implementing CSR programs. Universities, through their respective units or departments responsible for outreach programs such as CSR programs, should convene strategic meetings with stakeholders to collect their opinions or expectations. Additionally, as CSR programs require resources, university management should explore various mechanisms for mobilizing funds and resources, involving diverse stakeholders such as corporate entities, alumni, and government institutions. Faculty members are of utmost importance because they are directly engaged in the execution of CSR programs. From this perspective, faculty members should be adequately prepared for this critical role, as it can significantly impact a university’s viability in a competitive educational landscape. Thus, the study advocates for the implementation of capacity-building programs that focus on both the intellectual and technical empowerment of faculty members in managing CSR programs, with the expectation of achieving desired outcomes for the universities.

Limitations and avenues for further studies

This study is one of the few academic efforts that investigate the impact of university CSR programs on university brand positioning. Although it provides valuable insights in the field of university branding, it has identified some limitations that should be addressed in future research. Firstly, the study focused on only two universities. To strengthen the validity of the findings, future studies should involve a larger number of universities to establish a solid theoretical understanding of the relationship between university CSR and branding in higher education. The study’s findings were particularly surprising in areas such as operational responsibility, research and development responsibility, and philanthropic responsibility. Given the significance of these findings, it is suggested that future research should aim to replicate the proposed research model in diverse socio-cultural contexts, especially in developing countries. Considering the global relevance of university CSR, conducting a cross-cultural comparison with institutions in other developing countries could illuminate unique challenges and opportunities in effectively implementing CSR strategies. Additionally, undertaking comparative studies to contrast CSR practices among universities in developing and developed countries could also yield valuable insights. Such an approach would contribute to the generalization and robustness of findings related to university CSR and its impact on brand positioning.

Moreover, as the study involved both a public and a private university, future investigations might consider conducting comparative analyses between these two sectors to determine if there are statistically significant differences in their CSR practices and resulting brand positioning. To further enrich the knowledge in the university branding domain, the conceptual model can be modified and extended by including new variables or new perspectives regarding the topic under investigation. The model can be modified and extended to explore the role of digital media in amplifying the visibility and impact of university CSR activities and their impact on the image of the universities from customers’ perspectives. Additionally, the model can be modified and extended to explore the influence of moderator variables like employee empowerment, examining the combined effects of university CSR and faculty members’ empowerment on university brand positioning. Further studies could expand the research to include faculty, administrative staff, and external stakeholders such as employers and community members, providing a more holistic view of CSR's impact on university brand positioning. This study adopted a quantitative approach; hence, to complement the quantitative data, incorporating qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups could capture deeper motivations, attitudes, and perceptions of stakeholders regarding university CSR activities. This mixed-methods approach could enrich the findings and provide a more comprehensive analysis. Furthermore, the study proposes the adoption of a longitudinal approach to trace the evolving impact of university CSR on brand positioning. This approach recognizes that various interventions, implemented periodically, can influence stakeholders, including students, in different ways over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Amani

Dr. David Amani is a lecturer and research scholar in marketing who earned his Ph.D. in Business Administration (Marketing) from Mzumbe University in Tanzania. Currently, he works as a lecturer and researcher in the Department of Business Administration and Management at the University of Dodoma in Tanzania. His research interests include brand management, tourism marketing, sports marketing, corporate social responsibility, and entrepreneurial marketing. He has published several papers in various reputable journals, such as Service Marketing Quarterly, Social Responsibility Journal, International Hospitality Review, Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, and Future Business Journal.

References

- Ab Hamid, M. R., Sami, W., & Mohmad Sidek, M. H. (2017). Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 890(1), 012163. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/890/1/012163

- Akbari, M., Mehrali, M., SeyyedAmiri, N., Rezaei, N., & Pourjam, A. (2020). Corporate social responsibility, customer loyalty and brand positioning. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(5), 671–689. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-01-2019-0008

- Altschwager, T., Dolan, R., & Conduit, J. (2018). Social brand engagement: How orientation events engage students with the university. Australasian Marketing Journal, 26(2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2018.04.004

- Alwi, S., Che-Ha, N., Nguyen, B., Ghazali, E. M., Mutum, D. M., & Kitchen, P. J. (2020). Projecting university brand image via satisfaction and behavioral response: Perspectives from UK-based Malaysian students. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 23(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-12-2017-0191

- Amani, D. (2022a). Demystifying factors fueling university brand evangelism in the higher education sector in Tanzania: A social identity perspective. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2110187. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2110187

- Amani, D. (2022b). Internal branding and students’ behavioral intention to become active member of university alumni associations: The role of students’ sense of belonging in Tanzania Internal branding and students’ behavioral intention to become active member of university. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1997171

- Amani, D. (2022c). Internal corporate social responsibility and university brand legitimacy: An employee perspective in the higher education sector in Tanzania. Social Responsibility Journal, 19(4), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-12-2021-0540

- Atakan, M. G. S., & Eker, T. (2007). Corporate identity of a socially responsible university–a case from the Turkish higher education sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 76(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9274-3

- Batra, R., Zhang, Y. C., Aydinoğlu, N. Z., & Feinberg, F. M. (2017). Positioning multicountry brands: The impact of variation in cultural values and competitive set. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(6), 914–931. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.13.0058

- Blanco-González, A., Del-Castillo-Feito, C., & Miotto, G. (2021). The influence of business ethics and community outreach on faculty engagement: The mediating effect of legitimacy in higher education. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 30(3), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-07-2020-0182

- Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x

- Byrd, E. T. (2007). Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Review, 62(2), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605370780000309

- Carrillo‐Durán, M. V., Blanco Sánchez, T., & García, M. (2023). University social responsibility and sustainability. How they work on the SDGS and how they communicate them on their websites. Higher Education Quarterly, 2023, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12470

- Carroll, A. B. (1993). Business and society: Ethics and stakeholder management (2nd ed.). South-Western College Publishing.

- Cezarino, L. O., Liboni, L. B., Hunter, T., Pacheco, L. M., & Martins, F. P. (2022). Corporate social responsibility in emerging markets: Opportunities and challenges for sustainability integration. Journal of Cleaner Production, 362, 132224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132224

- Chan, T. J., Huam, H. T., & Sade, A. B. (2021). Students perceptions on the university social responsibilities of a Malaysian private university: Does gender matter. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 11(9), 1460–1473. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v11-i9/10754

- Chile, L. M., & Black, X. M. (2015). University–community engagement: Case study of university social responsibility. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 10(3), 234–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197915607278

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (pp. 655–690). Springer.

- Churchill, G. A. Jr, (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600110

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cronbach, L. J., & Shavelson, R. J. (2004). My current thoughts on coefficient alpha and successor procedures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64(3), 391–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164404266386

- Cuesta-Claros, A., Malekpour, S., Raven, R., & Kestin, T. (2021). Understanding the roles of universities for sustainable development transformations: A framing analysis of university models. Sustainable Development, 30(4), 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2247

- Cummings, C. L. (2014). The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods (M. Allen (Ed.), pp. 315–317). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483381411.n118

- El-Kassar, A. N., Makki, D., & Gonzalez-Perez, M. A. (2019). Student–university identification and loyalty through social responsibility: A cross-cultural analysis. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(1), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-02-2018-0072

- El-Kassar, A.-N., Makki, D., Gonzalez-Perez, M. A., & Cathro, V. (2023). Doing well by doing good: Why is investing in university social responsibility a good business for higher education institutions cross culturally? Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 30(1), 142–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-12-2021-0233

- Fernando, S., & Lawrence, S. (2014). A theoretical framework for CSR practices: Integrating legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory. Journal of Theoretical Accounting Research, 10(1), 149–178.

- Ferraris, A., Belyaeva, Z., & Bresciani, S. (2020). The role of universities in the Smart City innovation: Multistakeholder integration and engagement perspectives. Journal of Business Research, 119(2020), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.010

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman Publishing Inc.

- Fuchs, C., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2010). Evaluating the effectiveness of brand‐positioning strategies from a consumer perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 44(11/12), 1763–1786. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561011079873

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Furey, S., Springer, P., & Parsons, C. (2014). Positioning university as a brand: Distinctions between the brand promise of Russell Group, 1994 Group, University Alliance, and Million + universities. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 24(1), 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2014.919980

- Gaustad, T., Samuelsen, B. M., Warlop, L., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2018). The perils of self‐brand connections: Consumer response to changes in brand meaning. Psychology & Marketing, 35(11), 818–829. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21137

- González-Benito, Ó., & Martos-Partal, M. (2012). Role of retailer positioning and product category on the relationship between store brand consumption and store loyalty. Journal of Retailing, 88(2), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2011.05.003

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Díaz-Fernández, M. C., Shi, F., & Okumus, F. (2021). Exploring the links among corporate social responsibility, reputation, and performance from a multi-dimensional perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 99, 103079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103079

- Gupta, A. K., & Gupta, N. (2021). Environment practices mediating the environmental compliance and firm performance: An institutional theory perspective from emerging economies. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(3), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-021-00266-w

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Heffernan, T., Wilkins, S., & Butt, M. M. (2018). Transnational higher education: The importance of institutional reputation, trust and student-university identification in international partnerships. International Journal of Educational Management, 32(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-05-2017-0122

- Heslop, L. A., & Nadeau, J. (2010). Branding MBA programs: The use of target market desired outcomes for effective brand positioning. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 20(1), 85–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241003788110

- Jeong, Y. C., & Kim, T. Y. (2019). Between legitimacy and efficiency: An institutional theory of corporate giving. Academy of Management Journal, 62(5), 1583–1608. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0575

- Jongbloed, B., Enders, J., & Salerno, C. (2008). Higher education and its communities: Interconnections, interdependencies and a research agenda. Higher Education, 56(3), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9128-2

- Junod, A. N., & Jacquet, J. B. (2023). Insights for the Drop-off/Pick-up Method to Improve Data Collection. Society & Natural Resources, 36(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2022.2146821