Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of academic adjustment and sense of belonging on perceived stress in the context of college students’ adaptation to synchronous distance learning (SDL). It is driven by technological advancements and newfound familiarity, resulting from the necessity-driven adoption of SDL during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. We conducted a thematic analysis of 16 interview responses using the Academic Adjustment Scale, Sense of Belonging Scale, and Perceived Stress Scale to construe a quantitative questionnaire that was administered to 242 undergraduate and postgraduate students in India attending college through SDL. Both ‘sense of belonging’ and ‘academic adjustment’ emerged as significant predictors of perceived stress among students. Moreover, a student’s past campus experience played a moderating role in shaping the impact of ‘academic adjustment’ on perceived stress. Within the ambits of post-pandemic online degree programs, this study tackles a dearth of comprehensive research relating to the impact of SDL on the stress levels of college students. In the process, it highlights the implications of crafting interventions to foster belonging and academic adjustment so that students can better manage stress in SDL. It also underscores the value of factoring the students’ past campus experiences in promoting adjustment and reducing stress. Overcoming these challenges would ensure greater promotion of SDL dispersing quality and affordable education for the mass adaptable learners within the contemporary digital age, albeit in the Indian context.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

The global repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic reverberated across numerous sectors of the economy, including the education industry (Yi et al., Citation2024). The paradigm shift in the education delivery system has been profound, warranting a need for a deeper analysis of the effects of transformation in the learning environment on students. In the past, an extremely limited number of institutes offered the entire degree program online in a Synchronous Distance Learning (SDL) mode in which, the learning group interacts at the same time from different physical locations. Moreover, most of the courses offered online otherwise, were either short-duration or certification courses. Amidst this backdrop, owing to compulsions imposed by the pandemic, globally SDL emerged as a pivotal enabler of continuity in education, thereby allowing the institutions to transition into online operations. At that point, while proactively embracing this shift (Devisakti & Ramayah, Citation2023), institutions began adopting and implementing digital interface technologies, such as synchronous conferencing systems like Zoom and Google Meet and diligently training teachers to conduct classes in the SDL mode. Importantly, these digital alternatives could manifest through educational sessions conducted either synchronously or asynchronously. A study on German students indicated that those primarily engaged in synchronous settings reported a stronger sense of competence support, and relatedness, leading to greater overall satisfaction with the online term compared to students in mainly asynchronous settings (Fabriz et al., Citation2021). In fact, this connection between fulfilling psychological needs and positive outcomes does have far-reaching implications for the post-pandemic classroom environment.

Over time, the interplay between technological advancements, improved bandwidth, and the newfound familiarity resulting from the necessity-driven adoption of SDL, further catalyzed the surging popularity of this dynamic e-learning mode. In 2019, before the onset of the pandemic, the online degree market was forecasted to reach $36 billion by 2025. However, the impact of the pandemic substantially accelerated this projected growth, nearly doubling it to $74 billion by the same year (Unit, Citation2020). Fall 2020 marked a turning point, prompting a re-evaluation of education’s cost and value, comparing in-person learning to digital alternatives (Devisakti & Ramayah, Citation2023; Im Bok, Citation2023; Seifert & Bar-Tal, Citation2023; Tang et al., Citation2023; Yi et al., Citation2024; Zamora et al., Citation2023).

The transformative shift in the education landscape, particularly within post-pandemic online degree programs, necessitates an extensive exploration of its influence on learning outcomes, engagement, and overall educational experience. While there’s limited research on the impact of SDL on students’ stress levels, existing evidence is conflicting. For instance, a study on Vietnamese students indicated that 37.3% experienced stress in the e-learning environment (Lan et al., Citation2020); while other studies found no significant difference in stress levels between on-campus and off-campus students (Furlonger & Gencic, Citation2014; Ramos & Borte, Citation2020). Further research is needed to fully understand the role of academic adjustment and sense of belonging in influencing students’ perceived stress within the context of synchronous distance learning.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Academic adjustment

Pursuing higher education stems from the motive to excel professionally in life; and one of the most critical indicators of proficiency is deemed to be academic achievement (Iglesia & Solano, Citation2019). Where earlier studies have primarily focused on GPA as a significant predictor of academic achievement, more contemporary studies have gravitated towards a holistic approach to measuring academic adjustment, which in turn is a strong predictor of college attrition rate (Devisakti & Ramayah, Citation2023; Gerdes & Mallinckrodt, Citation1994). A few of the early pioneers in education have maintained their observation on ‘academic adjustment’ as a combination of several factors, like motivation levels, post-graduation plans, academic performance, lifestyle, and managing expectations. In a more general sense, how successfully students deal with the demanding and challenging needs of the educational environment in a college (Anderson et al., Citation2016; Baker & Siryk, Citation1984). Essentially, well-adjusted students are more likely to succeed professionally and maintain good emotional health (Baker & Siryk, Citation1984; Tang et al., Citation2023).

Academic adjustment as a parameter has not been widely studied in the context of SDL, leaving a gap for further examinations and explorations. Whatever little research that does exist, reveals contradictory evidence. While in some cases, there were no significant differences in the outcomes of SDL vis a vis traditional face-to-face learning (Neuhauser, Citation2002), other studies have noted that students preferred the traditional face-to-face setup over SDL on account of better time management, the ability to meet deadlines successfully, and better student-student and student-faculty interaction (Keramidas, Citation2012; Kunin et al., Citation2014). Bernard et al. (Citation2004) proposed that synchronous video classrooms in SDL mode have higher failure rates, resulting in higher dropouts compared to asynchronous learning and traditional face-to-face learning. However, the abrupt shift to online learning during the pandemic did significantly disrupt the students’ academic adjustment (Baltà-Salvador et al., Citation2021; Daşcı et al., Citation2023; Hollister et al., Citation2022; Lipka & Sarid, Citation2022), with unclear distinctions between synchronous and asynchronous learning formats in recent research. Therefore, this study specifically targets academic adjustment in synchronous distance learning settings, focusing on real-time interactions between students and instructors, albeit within the Indian context.

2.2. Sense of belonging

Maslow (Citation1943) postulated that human beings are motivated to achieve certain needs, owing to which, he derived a pyramid of motivational hierarchy, in which, he placed the ‘belongingness and love’ needs just above the basic physiological and safety needs (Mcleod, Citation2023). The experience of a person being involved in a system or environment that makes them feel like an integral part of that system or environment constitutes a sense of belonging (Hagerty & Williams, Citation1992). In the case of college students, the ‘need to belong’ stems from their perception of fit and the experience of valued involvement. The more students feel that their characteristics complement the system, and the more they feel valued and accepted in the new environment, the higher their belonging to the institute. In essence, this ‘sense of belonging’ is a parameter of evaluation for a smooth transition from the familiarity of high school to the new university system, coupled with the seamless integration into the dynamic college environment (Hagerty & Williams, Citation1992; Hoffman et al., Citation2002).

The need to belong theory propagates that belongingness has far-fetched effects on emotional patterns as well as on cognitive processes. It further states that a lack of healthy attachments can have a negative impact on an individual’s health, adjustment, and well-being (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). The exacting nature of the college programs makes it tougher for students to interact and form social groups, which is strongly associated with their sense of belonging (Hurtado & Carter, Citation1997). Other evidences reveal the importance of sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist in college (Devisakti & Ramayah, Citation2023; Hausmann et al., Citation2007; Im Bok, Citation2023; Seifert & Bar-Tal, Citation2023, Citation2023; Tang et al., Citation2023; Yi et al., Citation2024; Zamora et al., Citation2023). Existing literature has predominantly concentrated on the traditional college classroom environment. The sudden shift to online learning during COVID-19 led to a decrease in students’ sense of belonging (Dekhane et al., Citation2024; Tice et al., Citation2021). Studies have also indicated that implementing a study-together group intervention can positively impact the students’ sense of belonging, emphasizing thereby the importance of fostering a supportive community environment in online courses (Besser et al., Citation2022; Zhou et al., Citation2023). We focus on analyzing the sense of belonging in synchronous distance learning mode, aiming to understand how real-time interactions among Indian students and instructors influence the former’s sense of belonging.

2.3. Stress

The transition from school to college can be a stressful event, as it disturbs the students’ state of equilibrium, eliciting adaptive responses to the various stressors. In fact, stress, anxiety, and depression have been a few of the top concerns for college students in both traditional and non-traditional learning modes (Pedrelli et al., Citation2015). An analysis of the prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students revealed that more than one-third of the sample exhibited signs of stress (Beiter et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, while examining the different predictors of stress in a sample of French college students, it was discovered that most university students had high levels of perceived stress (Saleh et al., Citation2017). Around 30% of the students in a Hong Kong university displayed stress levels of moderate severity or above (Wong et al., Citation2006). As a matter of fact, the stress experienced by college students seems to be prevalent across programs and across cultures.

The results of stress analysis in the synchronous distance learning environment run parallel with that of the traditional learning framework. Qualitative research conducted on adult learners indicated stress as one of the primary negative emotions experienced in online courses (Zembylas, Citation2008). SDL also poses challenges while collaborating in teams, as it takes more time than usual to build trusting relationships due to the physical distance, making it thereby difficult for teams to collaborate effectively. The unsatisfactory performance in online collaborations due to half-built bonds and unutilized potential is a major source of stress (Allan & Lawless, Citation2003). A study investigated the impact of the forced change to online college during the pandemic on students’ emotional well-being and confirmed that stress had taken a toll in the new learning mode (AlAteeq et al., Citation2020; Chandra, Citation2021; Šorgo et al., Citation2022). However, a lack of detailed inquiry in the field of synchronous distance learning does make it imperative to explore the factors that cause stress vis a vis its remediation.

2.4. Academic adjustment and stress

When students transition from school to college, they are exposed to both social and academic changes. Specifically, the challenges of performing well academically, paving the way through a new curriculum, managing the workload, and future planning while maintaining a fine balance between academic and social life seem like daunting tasks for young adults. Maladjustment in any of these areas can exacerbate stress in students.

Findings suggest that academic concerns have been the leading predictor of stress in college-going students (Dusselier et al., Citation2005). As already established, considering GPA as the sole significant predictor of academic adjustment is not effective anymore. There has to be a combination of dimensions like academic performance, post-graduation plans, and pressure to succeed, which in amalgamation constitute academic adjustment, which in turn, correlates with stress (Beiter et al., Citation2015). Broadly, academic stressors have a notably higher negative correlation with students’ perceived stress levels, with academic performance cited as a significant source of stress by 82% of students (Malik & Javed, Citation2021; Son et al., Citation2020). Within the ambits of the pandemic, the drastic shift from a traditional classroom setting to a virtual one gave rise to the need to academically adapt to the new system. In fact, higher levels of stress have been consistently linked to poorer self-reported academic adjustment among students in this shift (VanRoo et al., Citation2023). Factors like the lack of digital connectivity, technical problems, excelling at a test through unscrupulous means, and online collaborations seem to have greatly affected the students’ ability to adjust academically, which in several cases led to stress. Therefore, a holistic analysis of how well academically adjusted the students are in this new synchronous distance learning setting, and if well-adjusted students feel less stressed, is called for. Therefore, this study proposes:

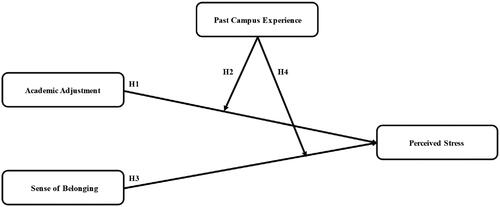

H1. Academic adjustment does have a significant effect on perceived stress of a student attending online college.

H2. The effect of academic adjustment on perceived stress is moderated by a student’s past campus experience, if any.

2.5. Sense of belonging and stress

The need to belong theory postulates that a failure to satisfy the innate drive to maintain at least a minimum number of social relationships that have a positive, lasting, and significant impact on life could lead to pathological consequences (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). University students attempt to satisfy this need with healthy peer-to-peer and student-faculty interactions. However, in times when this need remains unsatisfied, issues in adjustment and well-being arise. However, it is important to note herein that students who feel ‘belonged’ to the institution/university exhibit lower levels of stress (Civitci, Citation2015; Grobecker, Citation2016; Moeller et al., Citation2020), owing to which, it has increased the student retention percentage to the programs (O’Keeffe, Citation2013), better college adjustment, and increased academic performance, as well as academic motivation (Freeman et al., Citation2007).

Research evaluating the relationship between sense of belonging and stress in SDL mode is virtually non-existent. Nevertheless, some studies have explored college belongingness, specifically within the ambit of the pandemic, and broadly established that the ‘sense of belonging’ does impact psychological adjustment in college students (Arslan et al., Citation2022; Yi et al., Citation2024; Zamora et al., Citation2023). Unclear of the learning format, whether synchronous or asynchronous, a few other studies have examined the importance of sense of belonging in the COVID-19 induced online environment only to have a mixed set of conclusions. Where Barringer et al. (Citation2023) concluded that there was ‘no change’ in the students’ sense of belonging; others have emphasized the impact of sense of belonging in alleviating stress in students (Kirby & Thomas, Citation2022; Zamora et al., Citation2023). Because of these multifaceted views observed in literature, it is critical that we probe this field for more information, to understand how unsatisfied belongingness needs accrue stress in university students, specifically in the SDL mode to facilitate a better overall learning experience. Accordingly, we posit:

H3. Sense of belonging does have a significant effect on perceived stress of a student attending online college.

H4. The effect of sense of belonging on perceived stress is moderated by a student’s past campus experience, if any.

3. Research methodology

Our conceptual model consisted of First Order Construct, with ‘stress’ as a dependent variable, and Second Order Constructs, with both ‘academic adjustment’ and ‘sense of belonging’ as independent variables. Notably, the model also included ‘past campus experience’ of a student as the moderating variable. The framework aimed at investigating the influence of academic adjustment and sense of belonging of a student in the SDL mode on students’ perceived stress moderated through prior campus experience.

We conducted in-depth, structured, and open-ended interviews (Supplementary Appendix) of 16 undergraduate and postgraduate research participants studying in the SDL mode. A thematic analysis of the responses led to the identification of the following themes: academic motivation and engagement, peer learning and experiences, teacher-student interaction and support, behavioral strains, and college life and past campus experiences. These themes merited the use of the Academic Adjustment Scale, the Sense of Belonging Scale, and the Perceived Stress Scale, which serve as vital tools in assessing the students’ academic adjustment, sense of belonging, and perceived stress within the online learning environment. Importantly, prior research underscored the relevance and utility of these scales in similar contexts, thereby demonstrating associations with academic performance, retention, student engagement, and mental health (Malik & Javed, Citation2021; Norvilitis et al., Citation2022; Zhou et al., Citation2023). The Academic Adjustment Scale enabled us to evaluate the students’ adaptability to online education demands, encompassing time management skills, study habits, and coping mechanisms. The Sense of Belonging Scale helped in providing crucial insights into the students’ connection to their academic community and engagement with learning, which are essential for nurturing a supportive online environment amidst limited face-to-face interactions. The Perceived Stress Scale served as a means to gauge the students’ subjective stress experiences, crucial for identifying areas requiring additional support, especially considering unique stressors like screen fatigue and social isolation in online learning settings.

We used the selected scales with additional questions to capture social demographic details to build our survey questionnaire (Supplementary Appendix). We collected data through an online survey, using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method. Interestingly at that point, we organized a lively ‘F.R.I.E.N.D.S’ quiz on the Dare-2-Compete (now Unstop) platform, incorporating screening questions tailored to ensure that the participants were Indian college students, who were engaged in synchronous distance learning, either within graduate or post-graduate programs. Through this quiz, we aimed to closely engage our target demographic while simultaneously gathering valuable data. Further, to uphold data quality, we instructed the participants to provide accurate responses, as we proposed to conduct ‘consistency checks’ on a weekly basis, giving out prizes to those who provided the most consistent answers. This methodology not only encouraged active participation but also ensured that the data collected was reliable and relevant to our research objectives. A total of 242 questionnaire responses were returned, out of which, 10 responses were invalid. Subsequent cleansing of data to remove missing values and outlier responses resulted in 225 valid responses. This sample size (i.e. of 225) was considered ‘valid’, as it met the guidelines of the sample being ten times the number of arrows pointing to the variables in SmartPLS4 (Hair et al., Citation2014).

The questionnaires were distributed in English; it captured the socio-demographic details (e.g. age, gender, level of education, and currently enrolled program). It also collected information on past campus experiences, if any. The mean age of the respondents was 22 years. The sample comprised 116 (51.6%) women respondents, 104 (46.2%) male respondents, and 5 (2.2%) respondents, who preferred to not state their gender. 72 (32%) respondents were pursuing postgraduate courses, while 153 (68%) were pursuing undergraduate courses. The respondents with past college campus experience were 71 (31.5%), and those with no past college campus experience were 154 (68.4%). The subsequent part of the questionnaire consisted of the following scales:

3.1. Academic adjustment scale

This scale (Anderson et al., Citation2016) was used to measure academic adjustment in students, who have experienced a change in their learning environment. The three sub-dimensions in this scale included academic lifestyle (e.g. ‘I am enjoying the lifestyle of being a college student’), academic achievement (e.g. ‘I am satisfied with the level of my academic performance to date’), and academic motivation (e.g. ‘The reason I am studying is to lead to a better lifestyle’), formatively defining ‘academic adjustment’; they also comprised nine reflective items, whereby each item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (rarely applies to me) to 5 (always applies to me). Table 1 in Supplementary Appendix shows these items within the Academic Adjustment Scale.

3.2. Sense of belonging scale

To investigate the degree of identification and affiliation students have with the university community in the synchronous distance learning environment (Hoffman et al., Citation2002), we opted for the ‘sense of belonging’ scale. The five sub-dimensions in this scale formatively defining the ‘sense of belonging’ included perceived peer support (e.g. ‘I have developed personal relationships with other students in my class’), perceived faculty support/comfort (e.g. ‘I feel comfortable asking a faculty for help if I do not understand course-related material’), perceived classroom comfort (e.g. ‘I feel comfortable contributing to class discussions’), perceived isolation (e.g. ‘I rarely talk to other students in my class’), and empathetic faculty understanding (e.g. ‘I feel that a faculty member would be sensitive to my difficulties if I shared it with them’), were compounded of 26 items. Each item again was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely true) to 5 (completely untrue). Table 2 in Supplementary Appendix shows items in the Sense of Belonging Scale.

3.3. Perceived stress scale

To maintain a higher response rate (Sahlqvist et al., Citation2011), the abridged version (PSS-4) of the original PSS-14 scale was used to measure stress as an outcome variable, thereby ascribing to the paradigm shift in the learning environment of students (Cohen et al., Citation1983). The scale was compounded of four reflective items (e.g. ‘In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way?’) measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Table 3 in Supplementary Appendix shows items in the Perceived Stress Scale.

3.4. Structural equation model

We employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the hypothesized relationships in the conceptual model. PLS-SEM is a causal-predictive approach to SEM and is a powerful statistical technique (Reinartz et al., Citation2009) that allows for the examination of complex relationships among latent variables in social science disciplines (Hair et al., Citation2019; Lohmöller, Citation1989; Sarstedt et al., Citation2021; Wold, Citation1975). A significance level of p < 0.01 for direct relationships and p < 0.05 for moderating impact on the direct relationships was selected for hypotheses testing to minimize Type I errors and enhance the reliability of the findings. Further, path coefficients (β) for direct relationships between academic adjustment and stress, and sense of belonging and stress were evaluated at a significance level of 0.01. Moderating effects of past campus experience on the direct relationships within the model were tested with p < 0.05.

4. Data analysis and results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

highlights the mean, median, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation in academic adjustment, sense of belonging, and perceived stress scores of 225 respondents. The range of perceived stress score is 0–16, reflecting thereby a higher score, and indicating greater stress. Sense of belonging scores ranged from 26 to 130, higher scores indicating higher degree of student affiliation with the college operating in synchronous distance learning mode. Similarly, academic adjustment scores of the respondents ranged from 9 to 45, with higher scores indicating better academic adjustment to the synchronous distance learning mode of education.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

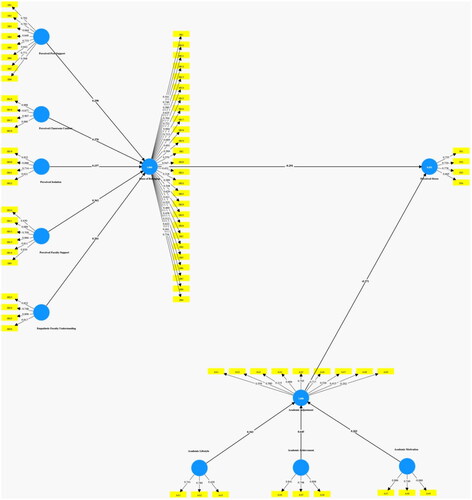

4.2. Reliability and validity

We tested the reliability of the variables using Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR). presents the results for reliability and validity, along with the factor loadings for the remaining items for the sample. All the Alpha values and CRs were higher than the recommended value of 0.700. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and CRs were all higher or close to 0.500 and 0.700, respectively, confirming therefore, convergent validity. Then, we assessed multi-collinearity with the value of each indicator’s Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) <5, as presented in . Further, discriminant validity was assessed through cross-loadings (). Through these data, we observe that all the factor loadings are greater than their cross-loadings, which in turn, satisfies the Fornell and Larcker criterion necessary for establishing discriminant validity.

Table 2. Reliability and validity measures.

Table 3. Discriminant validity.

In conducting the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis, we considered several statistical assumptions; for instance, normality of data distribution. Given the robustness of PLS-SEM to moderate departures from normality (Fornell & Bookstein, Citation1982; Hwang et al., Citation2010; Lohmöller, Citation1989; Wold, Citation1975), this assumption is reasonable, particularly given the large sample size typically required for SEM. Notably, both skewness and kurtosis for all the latent variables were within the limits of ±1 and ±3, respectively. Secondly, we assumed that the relationships between variables in the model were linear (Hair et al., Citation2013). The data collection methods and study design minimized any potential dependencies or biases in the sample. Then, we assessed multi-collinearity among predictor variables through the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with all indicators exhibiting VIF values below the threshold of 5, indicating thereby no substantial multi-collinearity issues. Importantly, this assessment suggests that the predictor variables in the model are not highly correlated with each other, supporting in the process the validity of our PLS-SEM analysis (Hair et al., Citation2019). Reflective-Formative Type 2 Model assessment in SmartPLS4 is shown in .

4.3. Structural model

4.3.1. Direct relationship analysis

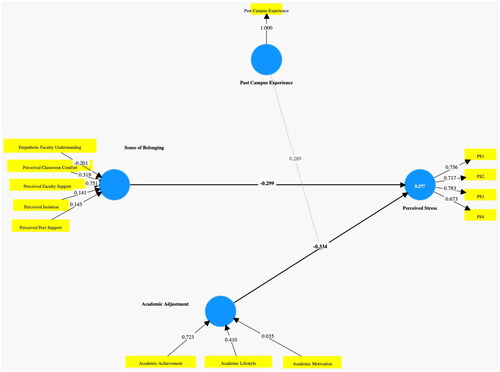

We tested the hypothesized relationships in the conceptual model; presents the results for the direct relationships. SRMR (Standardized Root Mean squared Residual) provides a measure of the discrepancy between the observed correlations and the correlations reproduced by the model. A lower SRMR value indicates a better fit of the model to the data. In our analysis, the SRMR value obtained for the estimated model was 0.068, which suggests a reasonably good fit.

Table 4. Direct relationship (hypotheses H1 and H3).

As the direct relationship between academic adjustment and perceived stress is negative and significant (β = −0.334, t = 4.148, p < 0.01), Hypothesis H1 is supported. Hypothesis H3 is also supported, as the direct relationship between sense of belonging and perceived stress is negative and significant (β = −0.299, t = 4.157, p < 0.01). Notably, the t-value represents the ratio of the estimated effect size to its standard error, indicating in the process, the extent to which the estimated effect differs from zero relative to the variability in the data. We compared the t-value to critical threshold values from the t-distribution to determine if the estimated effect is statistically significant. At a significance level of 0.01, t values in H1 and H3 are greater than tcritical of 2.576, thus supporting the hypotheses.

4.3.2. Moderation analysis

Then, we tested the moderation relationships in the conceptual model; shows the results for the moderating effects. The results reveal that for the relationship between academic adjustment and perceived stress, the moderating role of past campus experience was positive and significant (β = 0.289, t = 2.288, p < 0.05), lending support to Hypothesis H2 thereof. Further, for the relationship between sense of belonging and perceived stress, the moderating role of past campus experience was not significant (β = −0.112, t = 0.751, p = 0.453), owing to which, Hypothesis H4 is rejected. At a significance level of 0.05, t value in H2 is greater than tcritical of 1.96, thus supporting the hypothesis, and t value in H4 is lesser than tcritical of 1.96, thus not supporting the hypothesis.

Table 5. Moderation analysis (hypotheses H2 and H4).

shows the structural model analysis on SmartPLS4 for testing the above-defined hypotheses.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The study revealed that academic adjustment and sense of belonging have negative direct relationships with perceived stress among students. Thus, stress perceived by a student in the SDL mode may be attributed to low academic adjustment and low sense of belonging. Recent studies have found evidence supporting the negative impact of lack of academic adjustment and lack of sense of belonging on perceived stress among students in distance learning (Im Bok, Citation2023; Marler et al., Citation2021; Tang et al., Citation2023; VanRoo et al., Citation2023; Yi et al., Citation2024; Zamora et al., Citation2023). In their study, Tran et al. (Citation2022) on comparing two groups of students in Vietnam observed that the group with previous campus experience reported higher levels of stress. However, it may be noted that the specific moderator of past campus experience in SDL has not been explored before in the literature. This study indicates that past campus experience plays a moderating role in the relationship between academic adjustment and perceived stress, but not in the relationship between sense of belonging and perceived stress. Higher past campus experience can increase the perceived stress a student experiences in SDL due to poor academic adjustment. These findings along with the contributions of Fabriz et al. (Citation2021), Im Bok (Citation2023), Seifert and Bar-Tal (Citation2023), and Yi et al. (Citation2024), have important implications for educators and administrators alike, in designing programs and policies that can promote academic adjustment and sense of belonging among students in SDL, and ultimately reduce perceived stress levels. Further research may be conducted to explore other potential moderating factors that may influence these relationships.

In fact, this realization encourages a reassessment of the current support framework to guarantee both inclusivity and efficacy for students from various backgrounds. By placing emphasis on fostering nurturing learning environments, along with adaptive support systems, educators and administrators can equip students to excel despite the obstacles encountered in distance learning, nurturing in the process, a stronger and more vibrant educational community.

5.1. Implications

This study investigated the impact of SDL on the psychological well-being of university students while exploring the predictors of stress. In the post-pandemic synchronous classroom environment, it reveals the importance of devising interventions, fostering a sense of belonging, and academic adjustment to help students cope with stress in SDL. This may include, but is not limited to initiatives that provide more opportunities for student engagement and interaction, as well as academic support services tailored to SDL. The study highlights the importance of considering the students’ past campus experiences when implementing interventions to promote academic adjustment and reduce stress thereof.

These findings have implications for shaping future policies regarding online learning, particularly highlighting the necessity for allocating additional resources and providing support mechanisms to assist students in managing the distinctive challenges associated with SDL. Our interdisciplinary approach, combining psychology, education, and technology underscores the potential for interdisciplinary collaborations. Surmounting these challenges could promote SDL as the favored educational mode, triggering therefore, a competitive landscape among institutions to provide degree programs in either pure SDL or hybrid formats. This would also enrich the overall educational experience for students seeking comprehensive and adaptable learning within the contemporary digital era.

5.2. Limitations

There are certain limitations to the study that should be considered when interpreting the results and designing future studies. Firstly, the sample primarily comprised Engineering and Business School students from India only, limiting thereby the generalizability of the findings across other disciplines. Secondly, the scales used in the survey have not been specifically validated for use in web-based surveys. However, previous research suggests that web-based surveys and traditional paper surveys tend to produce comparable results (McCabe, Citation2004). Finally, we used a shorter version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) to measure stress levels, which may not capture the full complexity of the construct. Nevertheless, previous research has established the reliability and validity of the PSS-4 across different cultures (Warttig et al., Citation2013).

5.3. Future research directions

The current analysis focused on stress levels leaving other psychological well-being parameters like depression, anxiety, loneliness, etc. for further examination. Previous campus experience was used as a moderator to validate that those students who had previously been on campus for their college education experienced more stress in the SDL mode compared to students, who had never been on campus before the pandemic. Other moderating and/or mediating variables could be used in the future to scrutinize their effects on the direct relationships. For instance, social support has proven to have a buffering as well as a main effect on stress (Cohen & Wills, Citation1985). Further exploration is warranted in the SDL mode of education to identify and overcome the existing challenges for it to flourish as, if not more preferred, but equally preferred mode of education, given its promising nature in the constantly evolving industry of education.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.4 MB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (111.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sagarika Jaiswal

Sagarika Jaiswal is a software engineer and has recently completed a Master's degree in Psychology, merging her expertise in coding and statistics with a profound interest in human behavior. Her interdisciplinary background fuels a passion for utilizing software engineering techniques in deriving psychological insights. Through her work, she aspires to catalyze positive change by deepening our understanding of human behavior in the digital realm while innovating solutions at the forefront of technology. Sagarika can be contacted at [email protected]

Chinmay Tiwari

Chinmay Tiwari is a Business Analyst at JP Morgan, where he leverages data engineering and statistical modeling to empower the organization with valuable insights, driving strategic decision-making and facilitating business growth. With a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical and Electronics Engineering and a Master’s in Business Administration, he is deeply engaged in mastering applied statistics, quantitative research, data engineering, and other techniques to design efficient models to enhance decision-making in complex processes. Chinmay can be contacted at [email protected]

Amol Subhash Dhaigude

Amol Subhash Dhaigude is working as an Associate Professor in the department of OSCM&QM at S. P. Jain Institute of Management and Research (SPJIMR), Mumbai India. He is Fellow of IIM Indore, India. His publications have appeared in Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Journal of Knowledge Management, Communications of the Association for Information Systems (CAIS), Journal of Decision System, Measuring Business Excellence, Tourism Recreation Research, Journal of Public Affairs to name a few. He is actively engaged in research in supply chain management and services management. He is passionate about casewriting and teaching. He has published more than 25 cases in leading case publishing outlets including Ivey Publishing, CAIS, Emerald Emerging Market Case Studies, Operations Management and Educations Review and Journal of International Business Education. Amol can be contacted at [email protected]

Agrata Pandey

Dr. Agrata Pandey is a faculty at the Indian Institute of Management Rohtak, India, in the area of Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management. She has completed Fellow Program in Management (FPM) from Indian Institute of Management Indore. She has published numerous research papers and case studies in reputed peer reviewed journals. Prof. Pandey has been a part of various consulting assignments for organisations like Ordnance Factory Board, National Police Academy to name a few. Her research interests include the dark side of leadership, personality, organisational learning, knowledge management and perceived organizational support.

Giridhar B. Kamath

Dr. Giridhar B. Kamath is an Associate Professor at the Department of Humanities & Management, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal. He also holds an MBA and a doctorate degree in Marketing. He has published his papers in journals such as Journal of Travel Research and International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship.

References

- AlAteeq, D. A., Aljhani, S., & AlEesa, D. (2020). Perceived stress among students in virtual classrooms during the COVID-19 outbreak in KSA. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 15(5), 398–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.07.004

- Allan, J., & Lawless, N. (2003). Stress caused by on‐line collaboration in e‐learning: A developing model. Education + Training, 45(8/9), 564–572. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910310508955

- Anderson, J. R., Guan, Y., & Koc, Y. (2016). The academic adjustment scale: Measuring the adjustment of permanent resident or sojourner students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 54, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.07.006

- Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., & Zangeneh, M. (2022). Coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment in college students: Exploring the role of college belongingness and social media addiction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(3), 1546–1559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00460-4

- Baker, R. W., & Siryk, B. (1984). Student adaptation to college questionnaire. [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t06525-000

- Baltà-Salvador, R., Olmedo-Torre, N., Peña, M., & Renta-Davids, A. I. (2021). Academic and emotional effects of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic on engineering students. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7407–7434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10593-1

- Barringer, A., Papp, L. M., & Gu, P. (2023). College students’ sense of belonging in times of disruption: Prospective changes from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Education Research and Development, 42(6), 1309–1322. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2138275

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90–96. volume https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054

- Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Lou, Y., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Wozney, L., Wallet, P. A., Fiset, M., & Huang, B. (2004). How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 74(3), 379–439. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074003379

- Besser, A., Flett, G. L., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2022). Adaptability to a sudden transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Understanding the challenges for students. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 8(2), 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000198

- Chandra, Y. (2021). Online education during COVID-19: Perception of academic stress and emotional intelligence coping strategies among college students. Asian Education and Development Studies, 10(2), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-05-2020-0097

- Civitci, A. (2015). Perceived stress and life satisfaction in college students: Belonging and extracurricular participation as moderators. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 205, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.077

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Daşcı, E., Salihoğlu, K., & Daşcı, E. (2023). The relationship between tolerance for uncertainty and academic adjustment: The mediating role of students’ psychological flexibility during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1272205. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1272205

- Dekhane, S., Park, H., Jonassen, L., & Jin, W. (2024). Virtual peer mentoring to develop a sense of belonging during COVID-19 – A pilot study. Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3626252.3630962

- Devisakti, A., & Ramayah, T. (2023). Sense of belonging and grit in e-learning portal usage in higher education. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(8), 4850–4864. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1983611

- Dusselier, L., Dunn, B., Wang, Y., Shelley, M. C., & Whalen, D. F. (2005). Personal, health, academic, and environmental predictors of stress for residence hall students. Journal of American College Health, 54(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.54.1.15-24

- Fabriz, S., Mendzheritskaya, J., & Stehle, S. (2021). ‘Impact of synchronous and asynchronous settings of online teaching and learning in higher education on students’ learning experience during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 733554. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.733554

- Fornell, C., & Bookstein, F. L. (1982). Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151718

- Freeman, T. M., Anderman, L. H., & Jensen, J. M. (2007). Sense of belonging in college freshmen at the classroom and campus levels. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.203-220

- Furlonger, B., & Gencic, E. (2014). Comparing satisfaction, life-stress, coping and academic performance of, counselling students in on-campus and distance education learning environments. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 24(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2014.2

- Gerdes, H., & Mallinckrodt, B. (1994). Emotional, social, and academic adjustment of college students: A longitudinal study of retention. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1994.tb00935.x

- Grobecker, P. A. (2016). A sense of belonging and perceived stress among baccalaureate nursing students in clinical placements. Nurse Education Today, 36, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.09.015

- Hagerty, B. M., & Williams, L.-S. (1992). Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 6(3), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9417(92)90028-h

- Hair, J. F. Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & G. Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hausmann, L. R. M., Schofield, J. W., & Woods, R. L. (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and White first-year college students. Research in Higher Education, 48(7), 803–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-007-9052-9

- Hoffman, M., Richmond, J., Morrow, J., & Salomone, K. (2002). Investigating ‘sense of belonging’ in first-year college students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 4(3), 227–256. https://doi.org/10.2190/DRYC-CXQ9-JQ8V-HT4V

- Hollister, B., Nair, P., Hill-Lindsay, S., & Chukoskie, L. (2022). Engagement in online learning: Student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Frontiers in Education, 7, 851019. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.851019

- Hurtado, S., & Carter, D. F. (1997). Effects of college transition and perceptions of the campus racial climate on Latino college students’ sense of belonging. Sociology of Education, 70(4), 324–345. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673270

- Hwang, H., Malhotra, N. K., Kim, Y., Tomiuk, M. A., & Hong, S. (2010). A comparative study on parameter recovery of three approaches to structural equation modeling. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(4), 699–712. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.47.4.699

- Iglesia, G. d., & Solano, A. C. (2019). Academic achievement of college students: The role of the positive personality model. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 77(5), 572–583. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1301840 https://doi.org/10.33225/pec/19.77.572

- Im Bok, G. (2023). Belonging in distance learning: Perspectives of adult learners in Malaysia. Learning and Teaching, 16(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.3167/latiss.2023.160104

- Keramidas, C. (2012). Are undergraduate students ready for online learning? A comparison of online and face-to-face sections of a course. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 31(4), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/875687051203100405

- Kirby, L. A. J., & Thomas, C. L. (2022). High-impact teaching practices foster a greater sense of belonging in the college classroom. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(3), 368–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1950659

- Kunin, M. D., Julliard, K. N., & Rodriguez, T. E. (2014). Comparing face-to-face, synchronous, and asynchronous learning: Postgraduate dental resident preferences. Journal of Dental Education, 78(6), 856–866. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2014.78.6.tb05739.x

- Lan, H. T., Long, N. T., & Hanh, N. V. (2020). Validation of depression, anxiety and stress scales (DASS-21): Immediate psychological responses of students in the e-learning environment. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(5), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n5p125

- Lipka, O., & Sarid, M. (2022). Adjustment of Israeli undergraduate students to emergency remote learning during COVID-19: A mixed methods examination. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2022.2033856

- Lohmöller, J. B. (1989). Latent variable path modeling with partial least squares. Physica.

- Malik, M., & Javed, S. (2021). Perceived stress among university students in Oman during COVID-19-induced e-learning. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 28(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00131-7

- Marler, E. K., Bruce, M. J., Abaoud, A., Henrichsen, C., Suksatan, W., Homvisetvongsa, S., & Matsuo, H. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on university students’ academic motivation, social connection, and psychological well-being. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000294

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

- McCabe, S. E. (2004). Comparison of web and mail surveys in collecting illicit drug use data: A randomized experiment. Journal of Drug Education, 34(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.2190/4HEY-VWXL-DVR3-HAKV

- Mcleod, S. (2023, March 2). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory. Retrieved from Simply Psychology https://simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

- Moeller, R. W., Seehuus, M., & Peisch, V. (2020). Emotional intelligence, belongingness, and mental health in college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 93. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00093

- Neuhauser, C. (2002). Learning style and effectiveness of online and face-to-face instruction. American Journal of Distance Education, 16(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15389286AJDE1602_4

- Ng, K. C. (2007). Replacing face-to-face tutorials by synchronous online technologies: Challenges and pedagogical implications. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v8i1.335

- Norvilitis, J. M., Reid, H. M., & O'Quin, K. (2022). Amotivation: A key predictor of college GPA, college match, and first-year retention. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 11(3), 314–338. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijep.7309

- O’Keeffe, P. (2013). A sense of belonging: Improving student retention. College Student Journal, 47(4), 605–613.

- Pedrelli, P., Nyer, M., Yeung, A., Zulauf, C., & Wilens, T. (2015). College students: Mental health problems and treatment considerations. Academic Psychiatry, 39(5), 503–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0205-9

- Personnel and Human Resources (2019). Global e-learning market analysis 2019. Retrieved from Research and Markets https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/4769385/global-e-learning-market-analysis2019

- Pittman, L., & Richmond, A. (2008). University belonging, friendship quality, and psychological adjustment during the transition to college. The Journal of Experimental, 343–362. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.76.4.343-36

- Ramos, J., & Borte, B. (2020). Graduate student stress and coping strategies in distance versus traditional education. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 52–60.

- Reinartz, W., Haenlein, M., & Henseler, J. (2009). An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2009.08.001

- Sahlqvist, S., Song, Y., Bull, F., Adams, E., Preston, J., & Ogilvie, D. (2011). Effect of questionnaire length, personalization and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: Randomized controlled trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-62

- Saleh, D., Camart, N., & Romo, L. (2017). Predictors of stress in college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00019

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of market research (pp. 587–632). Springer International Publishing.

- Seifert, T., & Bar-Tal, S. (2023). Student-teachers’ sense of belonging in collaborative online learning. Education and Information Technologies, 28(7), 7797–7826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11498-3

- Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

- Šorgo, A., Crnkovič, N., Gabrovec, B., Cesar, K., & Selak, Š. (2022). Influence of forced online distance education during the COVID-19 pandemic on the perceived stress of postsecondary students: Cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(3), e30778. https://doi.org/10.2196/30778

- Tang, C., Thyer, L., Bye, R., Kenny, B., Tulliani, N., Peel, N., Gordon, R., Penkala, S., Tannous, C., Sun, Y.-T., & Dark, L. (2023). Impact of online learning on sense of belonging among first year clinical health students during COVID-19: Student and academic perspectives. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04061-2

- Tice, D., Baumeister, R., Crawford, J., Allen, K., & Percy, A. (2021). Student belongingness in higher education: Lessons for Professors from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 18(4), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.4.2

- Tran, N. H., Nguyen, N. T., Nguyen, B. T., & Phan, Q. N. (2022). Students’ perceived well-being and online preference: Evidence from two universities in Vietnam during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912129

- Unit, E. I. (2020, April 30). $74B Online degree market in 2025, up from $36B in 2019. Retrieved from Holon IQ https://www.holoniq.com/notes/74b-online-degree-market-in-2025-up-from-36b-in-2019

- VanRoo, C., Norvilitis, J. M., Reid, H. M., & O'Quin, K. (2023). The new normal: Amotivation, sense of purpose, and associated factors among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Reports, 332941231181485. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941231181485

- Warttig, S. L., Forshaw, M. J., South, J., & White, A. K. (2013). New, normative, English-sample data for the Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4). Journal of Health Psychology, 18(12), 1617–1628. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313508346

- Wold, H. (1975). Path models with latent variables: The NIPALS approach. In H. M. Blalock, A. Aganbegian, F. M. Borodkin, R. Boudon, & V. Capecchi (Eds.), Quantitative sociology: International perspectives on mathematical and statistical modeling (pp. 307–357). Academic.

- Wong, J. G. W. S., Cheung, E. P. T., Chan, K. K. C., Ma, K. K. M., & Wa Tang, S. (2006). Web-based survey of depression, anxiety and stress in first-year tertiary education students in Hong Kong. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(9), 777–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01883.x

- Yi, S., Zhang, Y., Lu, Y., & Shadiev, R. (2024). Sense of belonging, academic self‐efficacy and hardiness: Their impacts on student engagement in distance learning courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13421

- Zamora, A. N., August, E., Fossee, E., & Anderson, O. S. (2023). Impact of transitioning to remote learning on student learning interactions and sense of belonging among public health graduate students. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 9(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/23733799221101539

- Zembylas, M. (2008). Adult learners’ emotions in online learning. Distance Education, 29(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802004852

- Zhou, X., Li, Q., Xu, D., Holton, A., & Sato, B. K. (2023). The promise of using study-together groups to promote engagement and performance in online courses: Experimental evidence on academic and non-cognitive outcomes. The Internet and Higher Education, 59, 100922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2023.100922