Abstract

Professional success depends on more than just academic achievements frequently defined and evaluated as grades, academic averages and approval of semesters. Other non-cognitive factors, such as ‘grit’, or academic persistence, have been related to a decrease in academic dropout and success prediction. But it has not been measured in medical students. This study seeks cross-cultural psychometric validation in Spanish of the GRIT-S questionnaire in its original version to measure academic persistence in medical students. Cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire was carried out based on the ISPOR standards (cultural translation and adaptation of texts). The final questionnaire was applied to 427 medical students. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed. The analysis was performed with Lisrel 9.30 student version. The questionnaire did not show difficulty in content or comprehension on the part of the students. The exploratory factor analysis identified two constructs: Consistency in interests and persistence of effort. A confirmatory factor analysis was performed with a sample size of 427 subjects. The overall fit indices indicate good fit: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) 0.0509 (< = 0.08), Normed Fit Index (NFI) 0.978 (> 0.9), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.996 (> 0.9), Standardized RMR (SRMR) 0.0361 (< 0.08), chi-square p-value 0.217. The GRIT-S questionnaire in Spanish is a feasible, valid, and change-sensitive tool when applied to medical students. It presents psychometric properties comparable to the original questionnaire, allowing its application for future studies and interventions focused on the academic success of this population.

Reviewing Editor:

Background

Traditionally, academic curricula focus on two primary domains for professional success: the acquisition of knowledge and the development of academic skills, which are aimed at obtaining scores or institutional results based on individual student performance (York et al., Citation2015; Cotruș et al., Citation2012; Tadese et al., Citation2022; Sladek et al., Citation2016). For many years, greater importance has been given to the wrongly labeled cognitive factors within the teaching-learning process, mistakenly attributing intelligence to these factors and systematically labeling ‘good students’ as more intelligent and ‘less intelligent’ those students with lower performance (Cotruș et al., Citation2012; Rivera Mandarache, Citation2007; Saibani & Simin, Citation2014; Duckworth et al., Citation2012). Non-cognitive skills, or ‘soft skills,’ refer to the skills students need to develop to for the purpose to interact with the educational context and achieve better learning outcomes (attitude, motivation, and performance) (Farrington et al., Citation2012; Isik et al., Citation2017).

Recently, Duckworth & Quinn (Citation2009), Duckworth et al. (Citation2007), Duckworth et al. (Citation2012) demonstrated that in the school population, students who showed greater strength and persistence in pursuing an academic goal had a higher chance of achieving professional success. This attribute, known as ‘grit’ or academic persistence, has been linked to superior academic achievements, such as decreased dropout rates, and is a more reliable predictor of success than innate talent (Duckworth et al., Citation2007). ‘Grit,’ is characterized by the courage and strength required for individuals to pursue a particular academic goal consistently over an extended duration. Individuals with high intellectual perseverance exhibit a clear understanding of their objectives and demonstrate tenacity and unwavering commitment in achieving them (Duckworth et al., Citation2007; Duckworth & Quinn, Citation2009).

The concept of ‘grit’ as a cardinal quality for professional success, especially in demanding fields such as healthcare, undergoes meticulous scrutiny when considering the complexity of human experience across various cultural and age-related contexts. The construct of ‘grit,’ comprised of passion and perseverance toward long-term goals, may present significant limitations when it comes to globally standardized measurements. Current tools for measuring ‘grit’ might not capture the fluidity of motivation and resilience, nor accurately reflect the diverse expressions of tenacity that vary with cultural and social practices within the stages of individual development. The literature underscores that definitions of success and commitment are not universally applicable, and attributes such as perseverance may be construed and esteemed differently across various cultures. This divergence presents challenges for validating existing questionnaires in a cross-cultural context.

Furthermore, the GRIT-S scale, which assesses academic tenacity, is grounded in a theory that may not account for the necessary adaptability in the face of unforeseen obstacles or changing interests over a lifetime. This rigid approach might not only limit our understanding of resilience among health professionals but also overlook the importance of cognitive and emotional flexibility in achieving long-term accomplishments. Moreover, current research has begun to question the reliability and incremental validity of ‘grit’ as a distinct construct from other personality traits, such as conscientiousness and self-control. In summary, although ‘grit’ may offer valuable insights into predicting success, it’s essential to approach its current measurements and practical applications cautiously, acknowledging its cultural variability and complexity.

As of now, there are no available questionnaires in Latin American Spanish tailored to assess academic tenacity specifically among medical students. Considering the possible results in school students by identifying those with decreased tenacity levels and their response to interventions, it is worth knowing whether these types of skills remain constant during adulthood or are modifiable, as in children during university years, and whether their identification or modification could have an impact on other variables such as academic success. Consequently, the aim of this study is the cross-cultural validation into Spanish of the GRIT-S scale in medical students. Hoping that this scale can be applied to undergraduate students as early as possible, making it possible to detect those at risk and carry out interventions promptly that contribute to their academic success and well-being.

Materials and methods

A Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation study of the GRIT-S scale in Spanish was designed for medical students and developed in two phases. The first phase consisted of the transcultural adaptation of the questionnaire based on the ISPOR guidelines for translation and cultural adaptation of texts. In the second phase, the internal consistency and construct validity of the Spanish version of the questionnaire were evaluated.

Cross-cultural validation of the questionnaire

The ISPOR guidelines for translation and cultural adaptation of texts () provided ten steps for validating the questionnaire in Spanish (Wild et al., Citation2005).

Table 1. Steps for translation and cross-cultural validation of questionnaires based on the principles of good practices for translation and cultural adaptation (ISPOR) (Wild et al., Citation2005).

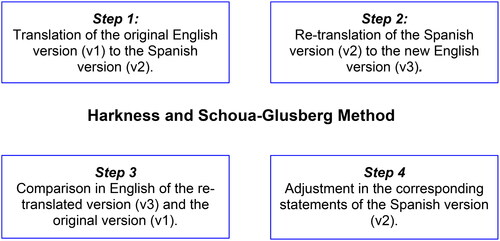

The steps from 1 to 5 were carried out using the four-step translation and back-translation method by Harkness and Schoua-Glusberg (Harkness et al., Citation2004) (). Considering the Latin American origin of the Spanish used in this study (Colombia), it is important to highlight that the translation was done into Latin American Spanish. Additionally, it is relevant to note that the translation and back-translation process was carried out by bilingual professionals whose native language is Spanish, thus ensuring the quality and fidelity of the final version.

Figure 1. Methodological translation process (Harkness et al., Citation2004).

A Delphi of six experts in medical education analyzed the translated version in Spanish through a process of harmonization and cultural equivalence evaluation. The Delphi group consisted solely of Spanish-speaking experts, primarily from Latin America, who were knowledgeable about the definition and significance of the construct of Grit and its domains. It’s important to note that the translators involved in the process were separate from the experts who participated in the Delphi study.

The resulting questionnaire was applied in a pilot test to a population of 42 medical students from the Faculty of Medicine of a Latin American university, with an equal gender distribution of 50% males and 50% females. Within this group, 70% were advanced students, enrolled between the third and sixth years of medical school. As for the faculty members, 70% held a master’s degree, while the remaining 30% had obtained a doctoral degree.

After obtaining informed consent, the procedure involved self-administration of the GRIT-S questionnaire and a cognitive interview that probed the question’s difficulty and comprehension (). After the pilot test, the items were further discussed, and some changes were made to the wording to improve understanding among the target population.

Table 2. Cognitive interview questionsTable Footnote*.

The final questionnaire was drafted after a last cognitive review by the group of experts, considering the information obtained and the corrections made during the pilot test.

Psychometric validation

Following the cross-cultural validation, an assessment of the psychometric properties of the final version was conducted to verify if the characteristics of the original questionnaire were maintained in the translation.

The instrument was administered to 427 medical students of different genders and educational levels after obtaining informed consent (from 1st to 12th semesters). Subsequently, as part of the confirmatory process, an initial exploratory factor analysis was conducted to analyze the items with higher weighted values, which were then subjected to expert committee review to be included in the model. Afterward, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed to confirm the construct validity of the questionnaire.

This study received approval from the ethics committees of both the teaching Hospital (CEI -101242-2019) and the School of Medicine (201812041).

Results

The instrument was administered to 427 medical students through non-probabilistic convenience sampling. Of the participants, 55% were women and 45% were men. Most of them fell within the participants’ mean (SD) age of 22.0 (±2.74) years.

Cross-cultural validation

81% of the students found it easy or very easy to answer the questionnaire after the pilot test. In comparison, 19% of the students considered it difficult or very difficult, specifically regarding item number 8. Therefore, this item needed to be modified by replacing the word ‘diligent’ with its Spanish equivalent, as it was confusing for most students. The rest of the items did not show difficulty in terms of content or comprehension for the students.

Psychometric validation

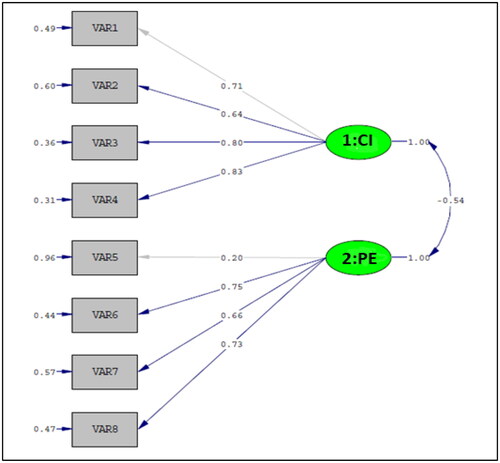

The analysis was done with Lisrel 9.30 Student Version and the Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimator because the variables are ordinal with five categories and don’t show multivariate normality (Finney et al., Citation2013). After performing the confirmatory factor analysis (n = 427), the distribution of items into two factors or constructs was confirmed. The overall fit indices are acceptable (see ). After performing the confirmatory factor analysis (n = 427), the distribution of items into two factors or constructs was confirmed. The overall fit indices are acceptable (see and ).

Table 3. Overall fit indices.

Table 4. Composite reliability and average variance extracted for academic tenacity.

Factor: Consistency in interests: Items 1, 2, 3, 4

Factor: Persistence in effort: Items 5, 6, 7, 8

Construct validity

A confirmatory factor analysis was performed with a sample size of 427 subjects. The overall fit indices indicate good fit: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) 0.0509 (< = 0.08), Normed Fit Index (NFI) 0.978 (> 0.9), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.996 (> 0.9), Standardized RMR (SRMR) 0.0361 (< 0.08), chi-square p-value 0.217.

The composite reliability and average variance extracted are acceptable, except for the average variance extracted of the second construct. For the consistency in interests (CI) construct, the composite reliability is 0.83 (> 0.7), and the average variance extracted is 0.56 (> 0.5). For the persistence in effort (PE) construct, the composite reliability is 0.69 (< 0.7), and the average variance extracted (AVE) is 0.39 (< 0.5).

Convergent validity is considered sufficient as the standardized factor loadings are high (greater than 0.6) and statistically significant (t value > 1.96), except for variable 5. Discriminant validity is adequate (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981), as the average variance extracted for each factor is greater than the square of the correlation between them (0.54 x 0.54 = 0.29). See and .

The data analysis reveals two factors: interests (factor one), measured by Items 1, 2, 3, and 4, and persistence in effort (factor two), measured by Items 5, 6, 7, and 8.

The composite reliability for the first factor is 0.83, and for the second factor, it is 0.69 (). Both values are acceptable, as the literature suggests a value of 0.7 or higher. The average variance extracted (AVE) for the first factor is 0.56, and for the second factor, it is 0.39. The second factor has a low AVE due to the weak factor loading of the first variable in that factor. The literature suggests AVE values equal to or greater than 0.5. Convergent validity is suitable for both the first and second factors, except for the weak factor loading of the first variable in the second factor.

Table 5. Factor loadings for grit survey items: original version (Christensen & Knezek, Citation2014) vs. Spanish Version.

The composite reliability for the first factor is 0.83, and for the second factor, it is 0.69, as shown in . The average variance extracted (AVE) for the first factor is 0.56, and for the second factor, it is 0.39. The square of the correlation between the two factors is 0.29 (, ). The second factor has a low AVE due to the weak factor loading of the first variable in that factor. The literature suggests AVE values equal to or greater than 0.5. Convergent validity is suitable for both the first and second factors, except for the weak factor loading of the first variable in the second factor. Discriminant validity is adequate (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981), as the AVE for each factor is greater than the square of the correlation between them ().

Table 6. Discriminant validity of the factors.

Table 7. Factor loadings or standardized regression coefficients (Spanish Version).

Discussion

The adaptation of the Instrument for measuring Academic Perseverance (GRIT-S) was proposed in this study for monitoring and evaluating academic perseverance in medical students, similar to its original use, which aimed to identify students who were less likely to achieve their long-term learning goals. This instrument adaptation was carried out following a methodology that ensured content validity. The results of this validation were compared to the results of the original scale. The GRIT-S scale in Spanish is valid and reliable for judging medical students between the ages of 15 and 26. It showed acceptable results in the confirmatory factor analysis, confirming the loading of items into two factors (like the original work) and having composite reliability values higher than the suggested literature threshold of 0.7. Like the original Grit scale, the Grit (Duckworth et al., Citation2007) and GRIT-S (Duckworth & Quinn, Citation2009) scales identified two constructs: consistency of interests (Items 1, 2, 3, and 4) and persistence of effort (Items 5, 6, 7, and 8). However, this study did not incorporate variables such as performance, satisfaction, happiness, or other non-cognitive skills that may be related to grit, similar to previous related validations conducted by Duckworth & Quinn (2007, Citation2009) and Tyumeneva et al. (Citation2019).

Additionally, the data correlated with Spanish validation studies of the GRIT-S questionnaire in Spanish in other populations (Arco-Tirado et al., Citation2018; Collantes-Tique et al., Citation2021).

One weakness is that the factorial loading of item 5 (0.2) is lower than the recommended threshold in the literature, which decreases the variance extracted for the corresponding factor. However, from a conceptual perspective, it is appropriate to retain the item. For these reasons and following the recommendations of the literature (Chin, Citation1998), it is advisable to validate the instrument initially and propose changes to the wording of item 5 in future work to achieve a better correlation with the factor.

The adjustments made in the cross-cultural validation regarding specific terms about the context did not modify the psychometric characteristics of the scale. This validation allows us to use the scale to identify and monitor medical students with low levels of grit, facilitate the definition of practical intervention actions, and improve short- and medium-term outcomes.

Conclusions

The GRIT-S questionnaire in Spanish is a feasible, reliable, and valid tool for medical students. It demonstrates psychometric properties similar to the original questionnaire, enabling its application for future studies and interventions focused at enhancing on the academic success of this population.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by FVP and SJR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SJR and EMTM, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have approved the submitted version and have agreed to be personally accountable for their contributions. They ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even those in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and documented in the literature.

Statements and declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate in The Ethics Review Committee of Universidad de Los Andes approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the researchers committed to safeguarding the confidentiality of the data collected. Participants were informed of their right to refuse or withdraw from the study at any time without adverse consequences. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend sincere gratitude to Professors Leopoldo Ferrer Záccaro and Daniel Enrique Suárez Acevedo for their invaluable guidance and mentorship throughout the research project, as well as to graduates Julieta Rozo Castaño and Daniela Duarte Montero for their dedicated contributions. The authors also acknowledge the School of Medicine of Universidad de los Andes, for their administrative support. Without their expertise, collaboration, and logistical assistance, the study would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sandra Ximena Jaramillo-Rincón

Sandra Ximena Jaramillo-Rincón is a Junior Researcher at Universidad de Los Andes, specializing in education for health professions. Her research interests include the impact of non-cognitive skills on professional success, teaching clinical reasoning, simulated patient programs, performance assessment, and reflective practice. She aims to understand the influence of emotional intelligence and resilience on professional effectiveness. Currently, she is conducting a 3-year experimental study measuring the impact of interventions to increase GRIT in medical students on academic success in the preclinical stage. Sandra also explores instructional methods and assessment tools to enhance clinical reasoning skills and optimize simulated patient programs for healthcare education. Her work advances healthcare education and improves patient care. Dr. Jaramillo-Rincón has published articles in medical journals such as Medical Teacher and Simulation in Healthcare. Her research on simulated patients and non-cognitive skills in medical education includes presentations at the AMMEE conference and regional research events. Since 2018, she has disseminated research data through presentations like “Non-Cognitive Skills” and “Measurement of Non-Cognitive Skills in Medical Students.”

Fernando Vazquez-Peña

Fernando Vazquez-Peña specializes in the analysis of questionnaires in educational research and the design, adaptation, and validation of these tools. He has published articles on the development and psychometric validation of questionnaires in renowned national, regional, and international journals, including the BMJ.

Lina Rodríguez

Lina Rodríguez focuses on the social determinants of health and social inequalities, particularly related to vector-borne diseases, mental health, and the syndemic relationship with non-communicable diseases in Colombia, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

Elena María Trujillo-Maza

Elena María Trujillo-Maza, MD, MEd, is a Family Physician and Associate Professor at Universidad de los Andes. Her research focuses on non-cognitive factors and predictors of academic success in medical students. Their findings have been presented at national scientific events, contributing to the field of medical education. Dr. Trujillo-Maza has co-authored several publications, including “Undergraduate Medical Training in Communication Skills: From Face-to-Face to Virtual Environments” and “Habilidades de comunicación en la formación médica contemporánea: Una experiencia pedagógica.” She has also conducted a case study on blended learning in social medicine, published in the International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. These works collectively advance medical education through innovative approaches like virtual environments, telemedicine, and blended learning.

References

- Arco-Tirado, J. L., Fernández-Martín, F. D., & Hoyle, R. H. (2018). Development and validation of a Spanish version of the grit-s scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 96. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00096

- Brown, T. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press.

- Chin, W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In M. G.A, Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Christensen, R., & Knezek, G. (2014). Comparative measures of grit, tenacity and perseverance. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 8(1), 16–30.

- Collantes-Tique, N., Pineda-Parra, J. A., Ortiz-Otálora, C. D., Ramírez Castañeda, S., Jiménez-Pachón, C., Quintero-Ovalle, C., Riveros Munévar, F., & Uribe Moreno, M. E. (2021). Validación de la estructura psicométrica de las escalas Grit-O y Grit-S en el contexto colombiano y su relación con el éxito académico. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 24(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.14718/ACP.2021.24.2.9

- Cotruş, A., Stanciu, C., & Bulborea, A. A. (2012). EQ vs. IQ which is most important in the success or failure of a student? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 5211–5213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.411

- Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (Grit-S). Journal of pPersonality aAssessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M., & Kelly, D. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of pPersonality and sSocial pPsychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

- Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P., & Tsukayama, E. (2012). What no child left behind leaves behind: The roles of IQ and self-control in predicting standardized achievement test scores and report card grades. Journal of eEducational pPsychology, 104(2), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026280

- Farrington, C. A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E., Nagaoka, J., Seneca, K., & Johnson, D. W. (2012). Teaching adolescents to become learners: The role of noncognitive factors in academic performance. A critical literature review. Chicago: Consortium on Chicago School Research. Obtenido de https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED542543

- Finney, S., DiStefano, C., En, M. R., & Hancock, G. R. (2013). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 439–492). NC: Information Age.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2018). Multivariate data analysis. Cengage Learning EMEA.

- Harkness, J., Schoua-Glusberg, A., & Pennell, B. (2004). Survey questionnaire translation and assessment. Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires, 546, 453–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471654728.ch22

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

- Isik, U., Wouters, A., Ter Wee, M. M., Croiset, G., & Kusurkar, R. A. (2017). Motivation and academic performance of medical students from ethnic minorities and majority: A comparative study. BMC mMedical eEducation, 17(1), 233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1079-9

- Rivera Mandarache, E. Y. (2007). Tesis: Coeficiente intelectual, rendimiento académico y satisfacción con la profesión elegida en grupos de estudiantes de la Universidad Nacional de Educación. Universidad Nacional de Educación Enrique Guzmán y Valle. Obtenido de . https://renati.sunedu.gob.pe/handle/sunedu/3128794

- Saibani, B., & Simin, S. (2014). The relationship between multiple intelligences and speaking skill among intermediate EFL learners in Bandar Abbas Azad University in Iran. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 4(2), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2014.861

- Sladek, R. M., Bond, M. J., Frost, L. K., & Prior, K. N. (2016). Predicting success in medical school: A longitudinal study of common Australian student selection tools. BMC mMedical eEducation, 16(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0692-3

- Tadese, M., Yeshaneh, A., & Mulu, G. B. (2022). Determinants of good academic performance among university students in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC mMedical eEducation, 22(1), 395. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03461-0

- Tyumeneva, Y., Kardanova, E., & Kuzmina, J. (2019). IRT analysis and validation of the grit Scale: A Russian investigation. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000424

- Wild, D., Grove, A., Martin, M., Eremenco, S., McElroy, S., Verjee-Lorenz, A., & Erikson, P, ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value in hHealth: The jJournal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 8(2), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x

- York, T. T., Gibson, C., & Rankin, S. (2015). Defining and measuring academic success. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 20(5), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.7275/hz5x-tx03