Abstract

This study shows the potential of collaborative mapping as a pedagogical tool for cultivating spatial citizenship competencies among young students from peripheral urban spaces in Ecuador. Building on theories of spatial citizenship, the study postulates that an understanding and critical collaborative analysis of socio-spatial dynamics foster responsible spatial citizenship. Adopting an experimental approach, the study engaged 18 student groups in a 6-week collaborative mapping exercise, harnessing tools such as Google Maps, recyclable materials, chart paper, markers, and paint. Initial findings revealed a pronounced lack of spatial citizenship competencies and political apathy among students. Post-mapping, students exhibited an enhanced understanding of their community’s spatial characteristics, notable locations, and potential improvements. Intriguingly, the activity sparked a renewed interest in political debates among the students and fostered a sense of ownership and responsibility towards their community. Additionally, it facilitated the identification of unregistered sites on Google Maps, thus developing their locational sense and exposing previously unseen urban dynamics. The study concludes that collaborative mapping can enhance students’ spatial citizenship competencies, encouraging them to play a more active role in their community’s development. The study’s findings have far-reaching implications for pedagogical approaches in social sciences and information gathering for municipal planning and territorial transformations.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

The engagement of youth in spatial planning is critically underexplored, especially when considering their unique geospatial perceptions, which can influence the inclusivity and effectiveness of city and neighborhood designs. The experiences and interactions young individuals have with urban spaces differ from those of adults, but spatial planning processes often overlook their perspectives. This oversight undermines harnessing youthful creativity and risks perpetuating unsuitable environments for many urban residents. Incorporating the geospatial information provided by youth can lead to more vibrant, inclusive urban spaces that reflect the diverse needs and innovative solutions of all age groups.

Four decades after the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which mandates the meaningful engagement and respect for youths’ views, their participation in spatial planning remains widely neglected (Yu et al., Citation2023). This is a notable unresolved issue that reveals a gap between global-scale policy intentions and real-world implementation. This gap becomes even more relevant when considering a growing political apathy among urban youth in developing countries and their perception of political actors as self-serving and uninterested in addressing their concerns (Koren & Mottola, Citation2022). This disengagement poses at least a twofold risk: stagnation in meaningful youth participation in spatial planning and a gradual erosion of democratic legitimacy as young people feel alienated from political processes that shape their living spaces.

Spatial citizenship, a competence that enables responsible participation in managing collective interests, can help to address such oversights. This concept is based on the principle that everyone has the right to influence their immediate surroundings (Cornwall, Citation2002; Löve, Citation2023). Spatial citizenship posits that a nuanced understanding of geographical concepts like space, place, and scale can enrich civic engagement and social participation (Shin & Bednarz, Citation2019). It serves as an interdisciplinary bridge, linking geography’s powerful disciplinary knowledge to the broader objectives of citizenship education, such as fostering social justice and civic responsibility. By promoting spatial citizenship, young people can strengthen their connection to the environment and engage in community decision-making, as they learn to understand their surroundings, recognize obstacles, and produce solutions. Such competence can empower youth to articulate changes, strengthen their presence in decision-making processes, and foster robust democratic engagement in urban development (Panek & Netek, Citation2019).

Previous studies have highlighted the transformative impact that learning spatial citizenship can have on young generations. Staley and Blackburn (Citation2023) emphasize the importance of teaching these concepts to equip youth with the ability to learn about their surrounding worlds and engage with them critically. Understanding the complex interplay between people, spaces, and the environment encourages youth to question and analyze these dynamics, potentially leading to innovative solutions. This educational approach lays the foundation for developing responsible citizens with a strong sense of ownership over both their local and global environments, thereby catalyzing sustainable behaviors and eventually supporting environmental restoration and preservation policies.

Similarly, Rozaki (Citation2022) highlights the value of spatial citizenship in encouraging a spirit of participatory democracy in young minds. As they mature, these individuals become active participants in shaping their environments and amplifying their voices on critical issues, from local development initiatives to global challenges like climate change (Haugseth & Smeplass, Citation2022). This engagement can enrich democratic processes, while fostering a future citizenry that is engaged, participative, and better suited to take on the responsibilities of our rapidly changing world.

Concerning pedagogical matters, recent studies in geographical education have introduced various approaches to promoting spatial citizenship among young students by using digital technology. One notable project was the ‘We Propose! Citizenship and Innovation in Geographical Education’ initiative implemented in Fortaleza City, Brazil, in 2011 (Barbosa Vieira & Esteves, Citation2018). This project aimed to encourage active spatial citizenship by empowering students to identify and propose solutions to local issues using open access online platforms. The initiative involved students identifying their key community problems and locating them on Google Maps. They then customized their maps by adding symbols to represent problematic areas to then share these maps on social media to raise public awareness about local violence and threats, and to discuss over alternative solutions to these challenges.

Similarly, Prihadi et al. (Citation2021) reported a study in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on an online geography course. This course encouraged students to map locations of interest and share their maps and thoughts on social media. The goal was to engage students in discussions about the significance of these spaces, deepening their understanding through interactions with others who also found these spaces meaningful. This approach emphasizes the importance of social interaction in learning about spatial relationships and challenges.

More recently, Sabah et al. (Citation2023) explored the use of extended reality (XR) technologies to engage young citizens in urban planning. These authors developed an online application intended to assist urban planning, which incorporates tangible interfaces, object detection capabilities, and augmented and virtual reality to create an immersive mixed reality environment. This application has proved capable of helping students develop spatial citizenship competences by enabling them to explore and adopt informed positions about the future of their city. Integrating XR technology represents a disruptive approach to geographical education, aiming to make urban planning more accessible and engaging for the younger generation.

Unfortunately, not all young students have equal access to digital-focused strategies, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds or living in informal peripheral neighborhoods. A study in Ecuador found that students living in informal settlements struggle to access basic infrastructure, hindering their use of digital devices and internet (Loor, Citation2024). This underscores the significance of inclusive educational practices that consider the varied technological accessibility of all students. By engaging in this, disadvantaged students can foster their spatial citizenship skills and make valuable contributions to their communities.

This study describes a teaching experiment aimed at fostering spatial citizenship among young students, particularly those in socio-economically vulnerable situations, through collaborative mapping exercises, combining Google Maps and site visits. Collaborative mapping entails the collection and sharing of spatial data through geospatial technologies (Atzmanstorfer et al., Citation2014). The experiment seeks to identify elements that empower these students to leverage their knowledge and contribute to societal problem-solving. Also, this approach addresses social inequality concerns related to the digital divide and inclusivity, rendering it feasible for students in economic hardship and with restricted access to technology. The rest of this article proceeds with a detailed account of the data collection and analysis methods, followed by the presentation of the results and their discussion and conclusion.

2. Material and methods

This study adopts a qualitative approach to explore the spatial understanding of peripheral neighborhoods and connections with the city’s core through the eyes of young students living in these areas. Recognizing the transformative potential of practical engagement and dialogue (Fetherston & Kelly, Citation2007), the research centers on an exploratory and descriptive qualitative experiment: a collaborative mapping task nested within a Geography course (Steils, Citation2021), which merges online services with repeated site visits. This emphasis on experiential learning and spatial exploration via collaborative mapping is chosen because it allows the students, as the agents of their learning, to critically engage with and navigate their surroundings. It provides them with a tangible tool to express their spatial narratives and witness the interconnectedness of the socio-environmental fabric within which they exist.

Manta, Ecuador, serves as the stage for this study, chosen for its suitable socio-spatial profile. Its fast-paced demographic expansion, young demographic composition, and significant proportion of inhabitants living in peripheral neighborhoods make it a veritable setting for understanding the stakes and complexities of fostering spatial citizenship among young students. Coupled with the backdrop of an impending electoral process, this case offers a prime vantage point to examine students’ interest in communal affairs and how they perceive, interact with, and wish to shape their urban environment, a narrative that remains underrepresented in spatial citizenship research.

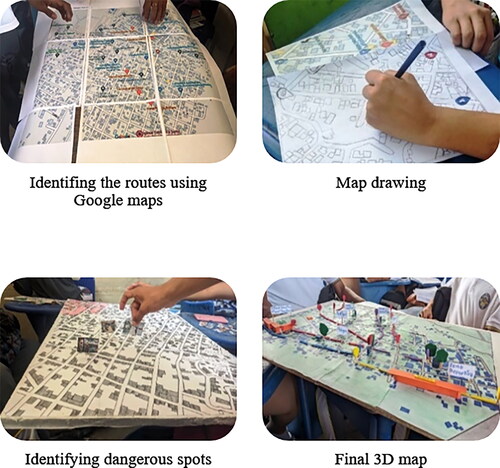

The study involved 103 students aged 15–16, who were divided into 18 groups, in a 6-week study organized in three strategic phases. The first phase laid the foundation by gauging students’ baseline spatial awareness through focus group discussions. The second phase employed an active learning paradigm, enabling the students to collaboratively map their immediate environment, thus fostering a collective narrative and a sense of shared accountability for the spaces they inhabit. This phase was operationalized through a set of instructions summarized in and an evaluation rubric, guiding students through the specifics of the mapping exercise. Finally, the third phase evaluated the growth in students’ spatial understanding by juxtaposing their initial focus group inputs with the outcomes of their collaborative mapping efforts. In compliance with ethical research standards, informed consent was obtained from the guardians of all participating students, and ethical approval for the study was appropriately waived.

The students were instructed to delineate areas in their communities and along their daily routes from home to school that held significance for them. They were encouraged to think beyond geographical landmarks to include spaces of emotional or social value. Concurrently, they were prompted to engage in reflective dialogues within their groups, to articulate why these places hold such meaning, capturing these reflections in verbal formats. To bring the maps to life, students were advised to use recyclable materials including cardboard, bottle caps, and old textiles, adding a tactile, three-dimensional aspect to their projects. This directive aimed to blend conventional cartographic elements with personal narrative and artistic expression, resulting in a more holistic representation of their spatial environments.

Additionally, to clarify expectations and guide student efforts, a comprehensive rubric was developed. The rubric outlines various criteria for four performance levels: excellent, good, satisfactory, and needs improvement. It assesses whether the map includes essential information, such as the title, subject, student’s name, and presentation date. The rubric then evaluates the accuracy of the map in representing the intended spaces, the hierarchical organization of content, and the justification for sites selection. Furthermore, it assesses the level of detail in the procedure and activity descriptions, the use of geographic references, and the use of colors and recyclable materials to emphasize significant areas. Last, the rubric examines how well the map reflects the spatial relationships of the depicted places.

In this process of discovery and learning, a word of caution must be heeded. The authors’ positionality, which is deeply rooted in urban settings where political and ideological polarization is rampant, may create certain inherent biases in this study. As educators raised in such contexts, we bring our expectations that others would naturally be aware of political happenings and, as a result, participate in political activism and discussions. This assumption, stemming from our own backgrounds, can potentially skew our interpretation of the students’ responses. To mitigate this potential bias, we place emphasis on privileging the voices of the students taking part in the research. Their perspectives, experiences, and understandings form the cornerstone of our study, and we remain cautious about allowing our personal biases to overshadow their experiences and observations.

Finally, the reflective nature of the third phase of the method, which juxtaposes initial observations with the outputs of the mapping exercise, facilitates an in-depth analysis of the growth in spatial understanding among the participants. This comparison provides a tangible measure of progress, grounding the research in empirical observations while also nurturing introspective learning among the students. By highlighting the transformations in their spatial comprehension and engagement, it underscores the pedagogical potency of collaborative mapping that merges online services with repeated site visits in fostering spatial citizenship. Thus, the method aligns with the research’s goal of catalyzing transformative participation in shaping urban landscapes and nurturing informed, active citizens who are equipped to engage with the complexities of the spatial environments they inhabit.

3. Results

The results highlight collaborative mapping as a powerful tool for enhancing spatial understanding and fostering spatial citizenship skills, particularly in contexts where political apathy and a lack of environmental awareness are prevalent among adolescents in peripheral urban Ecuador. The scenario, marked by optional voting for 16–18-year-olds and a fragmented understanding of governmental institutions, illustrates a considerable gap in their political and spatial knowledge. Their reliance on experiential rather than formal geographical markers, coupled with their sedentary lifestyles and spatial anxieties, emphasize the urgent need to strengthen spatial citizenship competencies.

The upcoming paragraphs illustrate how the collaborative mapping exercise transitions students from a passive learning state to an active one, symbolizing the emergence of spatial citizenship capabilities. As students engage with the complexities of map design, their evolving spatial awareness and growing understanding of the environment become apparent. During the evaluation phase, students show awareness of safety and commercial aspects of different routes. This highlights the role of collaborative mapping in expanding spatial consciousness. Consistently, students gain a better understanding of political challenges within governmental institutions. This leads to discussions about their rights and responsibilities as voters, encouraging them to engage more actively in spatial citizenship. The following sections will explore the socio-political and spatial dynamics uncovered by this educational method.

3.1. Establishing the baseline

The initial phase of the experiment revealed a troubling reality: young students exhibited a profound lack of spatial citizenship competencies and a marked indifference towards the political sphere. This disengagement from the civic realm became even more pronounced in a context where voting is optional for 16–18-year-olds, as previously noted. When presented with the prospect of voting and exercising their democratic rights in the upcoming elections, an unsettling uniformity echoed across the student cohort: a definitive reluctance to vote and a stark aversion to their peers who chose to engage. The sentiment that emerged was a collective disapproval of intent to vote, construed as a manifestation of personal interests or political affiliations. One of the students stated: ‘I vote if they pay me. I know of candidates who offer money in exchange of our vote’.

To explore the root of this political apathy, the students’ understanding of governmental institutions was addressed. The findings showed that their knowledge of these democratic fundamentals was lacking. This limited understanding may explain their apathetic response to the initial invitation to take part in the study. A common reason given for their disinterest in politics is a sense of powerlessness in shaping political outcomes. The perception of politics and politicians being linked to corruption and conflict exacerbates their disengagement. Additionally, they reported that electoral speeches often fail to align with their interests, exacerbating the disconnect from the political world.

When valuing their environmental consciousness, their lack of formal spatial understanding became obvious. Only a minority of individuals could accurately specify their residential addresses by providing both the street name and house number. Conversely, the majority relied on landmarks for navigation, showing a preference for experiential over formal geographical knowledge. Further analysis of their daily spatial practices revealed a sedentary lifestyle, with students predominantly confined to their homes. Those who venture out typically visit public spaces such as football fields or parks, and less frequently, the homes of neighbors or relatives. A smaller group reported aimlessly wandering the streets, highlighting a lack of purpose in their spatial activities. To illustrate, the following is the response of one student who took part in the study:

I live in the 15 de Septiembre neighborhood. Every day I walk from my house to school with my brother and two neighbors. That takes us about an hour. Along the way, there are several sections in which we speed up our pace or cross to another pavement to avoid conflicts with problematic people or stray dogs… my street has no name, but it’s easy to get to; there is a Christian church that everyone knows around the corner, on the main street, in the stretch that is unpaved.

3.2. The experiment

The heart of the study, the collaborative mapping exercise, brought enthusiasm to the geography classrooms. This activity spanned 6 weeks, dedicating 4 h each week to a blend of creativity and geographical reasoning. Students moved away from their usual coursework to create three-dimensional maps, using recyclable materials from their homes and school. Equipped with chart paper, markers, and paint, they reconstructed their familiar environments. Additionally, they used Google Maps to model the routes between their homes and school. Mapping their daily routes on a familiar application fostered a new appreciation for this technology.

Guided by the instructions illustrated in , and the rubric mentioned in Section 2, the students’ efforts resulted in maps that consistently included appropriate titles, subjects, and dates. While the sophistication of spatial representations varied, all maps captured the environments the groups intended to portray. Most maps showed a hierarchical organization of content and an advanced draft structure, although the justification for selecting specific sites could have been stronger. Comprehensive procedure logs and activity descriptions were common, with effective use of geographic references. The drawing of subject places was performed well, and the use of colors and recyclable materials effectively highlighted significant areas. The articulation of spatial relationships on the maps was identified as an area for potential improvement. Overall, the maps were rated between good and excellent across the various criteria.

The primary focus of the evaluation extended beyond merely assessing adherence to specified criteria; it aimed to highlight the procedural aspects and foster ongoing reflection on the students’ spatial understanding. The students exhibited a strong bond as they worked together on design elements and actively searched for locations close to their residences and along their daily commute to and from school. This heightened involvement led to productive outcomes. Not only did the students meet the evaluation criteria, but they also showed substantial improvement in their map-creation skills. shows the sequence of map making.

One notable outcome of this exercise was the observable enhancement in students’ understanding of map design and their improved ability to identify significant locations. As the weeks progressed, what initially seemed like a daunting task became more intuitive, with students gaining confidence in their spatial abilities. This progress provided a crucial insight: by adopting a dynamic, hands-on approach to teaching map usage, students actively engage in both creating maps and identifying places of interest. This shift from passive to active learning is crucial in enhancing their spatial citizenship competencies, hopefully preparing them to become spatially aware democratic citizens.

3.3. Learning evaluation

During the evaluation stage, group interviews were conducted with the leaders of the 18 participating groups. The goal was to understand whether the collaborative mapping exercise had encouraged the development of spatial citizenship skills and altered their perceptions of politics and collective issues. The questions were metacognitive, designed to explore what the students learned, how they learned it, how they identified and analyzed vulnerable spaces, and how they considered potential remedial actions.

Their daily commuting habits were especially interesting, with some notable findings. A slight majority reported relying on public transport, while others preferred walking or riding on a family member’s motorcycle or private car. The blend of transportation methods used by the students encouraged them to share and consequently discover and explore alternative routes. Through this process, they used different colors to label these routes based on safety and distance: red for high-risk areas, yellow for safe walking zones, and green for busy commercial areas. Their categorization resulted from a comprehensive analysis that considered various factors, such as incidents of violent robberies, traffic accidents, and proximity to commercial establishments.

Moreover, the students’ understanding of their surroundings expanded as they developed their maps. They noticed sites that were not previously recognized on their mental or Google Maps, enhancing their spatial awareness. Their maps included a diverse mix of spaces such as houses, commercial venues, eateries, healthcare services, government agencies, and sports fields. This activity enabled the students to uncover services and urban dynamics that were previously unknown to them, allowing them to link these sites to specific human activities, smells, noises, and even types of waste.

A notable outcome of the collaborative mapping was an increased political awareness among the students. Their thoughts show an increased understanding of the difficulties that government institutions face, especially in aspects like public infrastructure and waste disposal. Previously uninterested, several students, especially the females, began to critically evaluate their rights and the responsibilities of local government. This change led them to reconsider their optional voting rights and sparked debates about government accountability. Nonetheless, these observations are based on the opinions of a specific group and may not be universally valid. Thus, further research is required to fully comprehend the broader implications of such educational interventions on political consciousness. A quote from one of the female students is presented below:

Before this project, I did not really care about voting; it seemed pointless. But mapping our neighborhood made me realize how neglected our area is, especially when it comes to public services like waste collection. Now, I see that if we do not vote, we are basically giving permission for this negligence to continue. It is our right and our responsibility to demand better.

4. Discussion

Reflecting upon the development of spatial citizenship competencies, the students taking part in this exercise showed an enhanced understanding of their communities, which facilitated empowerment and encouraged an active role in shaping their environments. The practice of collaborative mapping promotes both teamwork and collaborative dynamics within diverse groups.

The experiment presented above illuminated the gaps between the spatial needs of youth and the actual attributes of the spaces they frequent. The act of mapping crucial locations such as health centers, commercial spots, eateries, sports fields, and government agencies underscored how young individuals could elevate their environmental awareness, leading to a sense of ownership and responsibility. This empowerment might spur increased participation in local initiatives, as noted in Panek and Netek (Citation2019) discussion on understanding the triggers behind spatial transformations.

The experiment facilitated a platform for students to express and exchange ideas about their environment, resonating with the findings of Araya Anabalón (Citation2011). The emergence of contrasting views among the students fostered a collective construction of reality and spatial possibilities, sparking an interest in political dialogue. The maps were a powerful tool that allowed students to share their spatial perceptions and ideas. This highlights the potential of collaborative mapping to improve students’ skills in critically analyzing and assessing spatial arrangements and changes. These skills play a crucial role in nurturing spatial citizenship and fostering a nuanced comprehension of socio-spatial dynamics.

Considering the broader applicability of the findings, collaborative mapping exercises could be instrumental across various global contexts, not only in neighborhoods where map functions are underdeveloped but also in well-mapped areas. The combination of emotional and physical aspects in the project’s approach to mapping creates a powerful and universally applicable method that can enrich spatial literacy and promote civic engagement. This approach aligns with current global trends, where there is an increasing emphasis on enhancing civic engagement through technology and participatory practices. As highlighted in the introduction, initiatives using digital technology are becoming more prevalent, demonstrating a global shift towards more inclusive and interactive governance. Even well-established regions stand to benefit from the improved socio-emotional mapping that these exercises facilitate, offering fresh perspectives and deeper community involvement in urban planning processes.

Finally, besides confirming previous research in various areas, the study also revealed two previously unexplored aspects. First, it found that students were initially doubtful of their peers who opted to vote. This shows the necessity for further investigation into the societal, psychological, and economic factors that influence young voters and their involvement in elections. Second, the study uncovered that female students exhibited a greater interest in political participation. This brings into question whether women feature a higher concern for political matters, particularly in the peripheral urban spaces of developing countries. These findings emphasize the need for more targeted studies in these contexts to address this uncertainty.

5. Conclusion

The practice of collaborative mapping, as demonstrated in this research, offers a dynamic platform for youth engagement in the generation and dissemination of geospatial information. This approach endows young people with the agency to incorporate their perspectives into the fabric of their communities, resulting in innovative spatial narratives, along with a heightened awareness of vital communal assets and prevailing issues. This study’s findings have multiple ramifications, both theoretical and practical. Theoretically, the study underscores the fluid nature of spatial citizenship, which, although a universal concept, manifests differently across various spatial contexts and among diverse actors. This variance is particularly salient given the study’s focus on adolescent students residing in peripheral urban areas in developing nations, a nuance that ought to shape interpretations of our results. On a practical level, the work can stimulate fresh pedagogical paradigms in social science education while supplying instrumental methods for capturing the public demands pivotal for municipal and regional planning.

It is important to acknowledge some limitations to the study’s approach. One notable constraint is the specific sociocultural context in which the study was conducted, which may limit the direct generalizability of the findings. The study’s focus on a single age group and specific urban peripheries may not capture the full spectrum of experiences and views across different demographics or geographical settings. Nonetheless, the methods used are compelling and applicable in diverse neighborhoods globally, particularly in promoting civic engagement. To fully explore this potential, it is necessary to evaluate these methods in a variety of contexts to confirm their effectiveness and adaptability across different sociocultural landscapes.

As for future work, there is an exigent need to explore the longitudinal effects of collaborative mapping initiatives on students’ spatial literacy and community engagement. In addition, comparative studies that examine how this practice influences spatial citizenship in varying sociopolitical contexts could further nuance our understanding. Conducting similar studies with different demographic groups could also enrich the pedagogical discourse and offer comprehensive insights into the versatility of collaborative mapping as an educational tool. These future avenues could help establish a robust methodological and theoretical framework, leading to the creation of more effective and context-sensitive pedagogical strategies and, ultimately, contributing to the advancement of urban communities, particularly in peripheral areas.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used Chat-GPT to improve readability and language. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Authors contributions

Ignacio W Loor: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review & editing, supervision. Wegner A Muentes: Investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ignacio W. Loor

Ignacio W. Loor holds a PhD in Human Geography and concentrates on the complex socio-environmental challenges of informal settlements in cities of developing countries. His work aims to connect scholarly research with practical policy implications, particularly examining how the spatial dynamics and layout of cities interacts with socio-economic factors to either exacerbate or mitigate vulnerabilities in peripheral communities. Beyond this central theme, this author also delves into corporate social responsibility, exploring how economic activity contributes to shaping the social and environmental fabric of informal settlements. His overarching goal is to conduct research that advances both academic understanding and policy frameworks for sustainable urban development. He is currently based at the Facultad de Ciencias Humanísticas y Sociales at Universidad Técnica de Manabí, in Ecuador.

Wegner A. Muentes

Wegner A. Muentes has a master’s in Education and has been a teacher at the Paquisha Public School in Manta, Ecuador for 10 years. He focuses on teaching History and Geography to high school students. Additionally, he guides students in research methods and case study projects. His goal is to help students develop thinking skills that are useful in school and in understanding politics and democracy in everyday life.

References

- Araya Anabalón, J. (2011). Jürgen Habermas, democracia, inclusión del otro y patriotismo constitucional desde la ética del discurso. Revista Chilena de Derecho y Ciencia Política, 2(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.7770/rchdycp-V2N1-art39

- Atzmanstorfer, K., Resl, R., Eitzinger, A., & Izurieta, X. (2014). The GeoCitizen-approach: Community-based spatial planning – an Ecuadorian case study. Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 41(3), 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230406.2014.890546

- Barbosa Vieira, E. C., & Esteves, M. H. (2018). An analysis of the contribution of ICT in association with geographical education for the formation of the spatial citizenship in public schools in Fortaleza, Brazil. In A. Baldini (Ed.), Conference proceedings. New perspectivs in science education (7th ed., p. 708). Libreriauniversitaria.it.

- Cornwall, A. (2002). Locating citizen participation. IDS Bulletin, 33(2), i–x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2002.tb00016.x

- Fetherston, B., & Kelly, R. (2007). Conflict resolution and transformative pedagogy: A grounded theory research project on learning in higher education. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(3), 262–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344607308899

- Haugseth, J. F., & Smeplass, E. (2022). The greta thunberg effect: A study of norwegian youth’s reflexivity on climate change. Sociology, 57(4), 921–939. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385221122416

- Koren, A., & Mottola, E. (2022). Marginalized youth participation in a civic engagement and leadership program: Photovoice and focus group empowerment activity. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(4), 1756–1769. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22959

- Loor, I. (2024). Unveiling the dynamics of informal settlements in quito: Occupation, organisation, and infrastructure challenges. GeoJournal, 89(2), 76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-024-11076-9

- Löve, L. E. (2023). Exclusion to inclusion: Lived experience of intellectual disabilities in national reporting on the CRPD. Social Inclusion, 11(2), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v11i2.6398

- Panek, J., & Netek, R. (2019). Collaborative mapping and digital participation: A tool for local empowerment in developing countries. Information, 10(8), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10080255

- Prihadi, S., Sajidan, S., Siswandari, S., & Sugiyanto, S. (2021). The challenges of application of the hybrid learning model in geography learning during the covid-19 pandemic. GeoEco, 8(1), 1–11. https://jurnal.uns.ac.id/GeoEco/article/view/52205 https://doi.org/10.20961/ge.v8i1.52205

- Rozaki, A. (2022). From political clientelism to participatory democracy. Engagement: Jurnal Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.29062/engagement.v6i1.1185

- Sabah, S., Hossain, I., Weiss, D., & Tillmann, A. (2023). Towards increasing active citiezn involvement in urban planning through mixed reality technologies. In N. Vrcek, L. Ortega, & P. Gird (Eds.), Proceedings of the Central European Conference on Information and Intelligent Systems (p. 577) Faculty of Organization and Informatics.

- Shin, E. E., & Bednarz, S. W. (2019). Conceptualizing spatial citizenship. In E. E. Shin & S. W. Bednarz (Eds.), Spatial citizenship education: Citizenship through geography (pp. 1–9). Routledge.

- Staley, S., & Blackburn, M. V. (2023). Troubling emotional discomfort: Teaching and learning queerly in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 124, 104030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104030

- Steils, N. (2021). Qualitative experiments for social sciences. In New trends in qualitative research (1st ed., Vol. 6, pp. 24–31). Ludomedia. https://doi.org/10.36367/ntqr.6.2021.24-31

- Yu, L., Gu, M., & Chan, K. L. (2023). Hong Kong adolescents’ participation in political activities: Correlates of violent political participation. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 18(3), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10143-6