Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted a reevaluation of educational modalities, shedding light on the potential incorporation of tax distance learning (TDL) in higher education. This study investigates the intricate relationship between psychosocial learning environments (PLE), anxiety, and satisfaction levels in TDL. Applying a quantitative methodology with a survey-based research strategy, data were collected through a questionnaire from a study sample of undergraduate taxation program students in the odd semester of the academic year 2022/2023. PLS-SEM was applied for data analysis. The findings reveal that PLE variables—instructor support, active learning, and enjoyment of online learning—are critical determinants, suggesting a nuanced interplay of factors influencing TDL outcomes. However, the study uncovers a paradox where high-quality instructor support fosters satisfaction despite inducing anxiety. Interestingly, student interaction, collaboration, personal relevance, authentic learning, and student autonomy exhibit limited influence during the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially due to altered dynamics in the tax educational landscape. The absence of a direct link between tax distance learning anxiety (TDLA) and tax distance learning satisfaction (TDLS) is explored, considering individual differences in coping mechanisms and the complex interweaving of cognitive, emotional, and motivational components within the Self-Determination Theory framework.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Distance education, also referred to as distance learning, is not a novel concept; however, in developing countries, this method is less popular than face-to-face learning. Nevertheless, with the implementation of large-scale social restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, distance learning emerged as a savior for education across nations (Barron et al., Citation2021). The COVID-19 pandemic triggered the phenomenon of “emergency distance learning” (Ezra et al., Citation2021; Ferri et al., Citation2020; Maphalala et al., Citation2021). Unlike conventional distance learning, the term emergency emphasizes the urgent need for temporary solutions and a shift in approach by relying on available resources to meet current needs (Ulus, Citation2020). This aligns with Tarchi et al. (Citation2022), who introduced the term “emergency” to underscore the specific situation that unfolded since early 2020. In response to the threat of COVID-19, universities worldwide canceled all face-to-face classes, including laboratories, internships, community service, and other learning experiences, swiftly transitioning to distance learning. The objective was to ensure that teaching and learning continued while safeguarding faculty, staff, and students from the public health emergency (Hodges et al., Citation2020). Consequently, students and instructors were compelled to swiftly shift and acclimate to distance learning without sufficient prior readiness, instructions, and resources (Abou-Khalil et al., Citation2021).

Reflecting on the experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, stakeholders in higher education acknowledge that distance learning plays a vital role and is equally essential as face-to-face instruction in delivering learning outcomes. Before the pandemic’s most severe period, Aktaruzzaman and Plunkett (Citation2016) emphasized that developing nations should reconsider distance learning as a necessity rather than a choice. This is crucial to ensure that every individual can access and complete their education to the highest level, especially when confronted with uncertain, ambiguous, complex, and increasingly turbulent conditions (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2018). Meanwhile, Ahmed et al. (Citation2020) concludes that migration to distance learning, although enforced as a non-alternative solution during COVID-19, will persist as the most viable alternative even after the pandemic subsides. Looking ahead, education should be considered not only as a lever to escape poverty (Hofmarcher, Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2021; Naveed & Sutoris, Citation2020) but also as a means to maximize individual potential and achieve well-being. Bozkurt and Sharma (Citation2020) assert that if designed effectively, distance learning can facilitate an efficient learning process, enabling students to attain their expected learning objectives and improving access to higher education for previously marginalized populations. Therefore, it is fitting to contemplate curriculum changes, including teaching methods, possibly in a radical manner.

Ismaili (Citation2021) believes there is significant future potential for e-learning platforms in higher education institutions. The research findings indicate that most students exhibit a positive attitude and willingness to engage in distance learning classes post the COVID-19 pandemic. However, students still deem traditional classroom settings indispensable, and distance learning is still in the developmental stage. Hence, a pivotal question remains whether distance learning can replace or merely complement face-to-face learning in developing countries after the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the transfer of the modern education paradigm from developed to developing nations may encounter challenges, as it is not always viable to tackle the associated obstacles effectively within a diverse environment. Furthermore, Ahmed et al. (Citation2020) asserts that the decision to permanently shift educational policies from face-to-face to distance learning in the future necessitates support based on a profound understanding of potential risks before their occurrence. Potential risks can be discerned from internal quality reports measuring student satisfaction and open comments reflecting students’ engagement in the learning process. Unmapped risks will contribute to the quality of education delivered to students. Xiao and Zhao (Citation2011) argue that this can impact societal perceptions, particularly employers’ views regarding the quality of graduates. Chen and Panda (Citation2013) support this by stating that exclusive online learning resources can raise questions about the validity and reliability of teaching methods and course content, leading to negative perceptions of distance education within society. A shift to distance learning methods without careful consideration also has consequences for a decrease in the rate of completion or an increase in dropout behavior (Heidrich et al., Citation2018; Pierrakeas et al., Citation2020; Tan et al., Citation2022; Yasmin, Citation2013). This paradox arises because distance learning is a viable alternative for both traditional and nontraditional students (Beese, Citation2014; Cooper, Citation2000), unrestricted by geographical locations (Gurajena et al., Citation2021).

In both normal and uncontrolled circumstances, previous researchers have predominantly emphasized the physical resources of online learning as the singular determinant of the success of implementing distance learning in developing country universities. Studies conducted in Asia and Africa before the pandemic have indicated that the deficiency in IT infrastructure (Al-Smadi et al., Citation2022; Farid et al., Citation2015), limited access to computers and the internet (Baggaley, Citation2008; Baro et al., Citation2013; Hondonga et al., Citation2021; Morgan et al., Citation2022; Moyo-Nyede & Ndoma, Citation2020), low Internet bandwidth (Fong & Hui, Citation2001; Maheshwari et al., Citation2021; Mondal et al., Citation2013; Othman et al., Citation2021; Ramos-Paja et al., Citation2010; Valentín-Sívico et al., Citation2023), security of e-learning systems (Barik & Karforma, Citation2012; Chen & He, Citation2013; Guo et al., Citation2020; Ramim & Levy, Citation2006), insufficient e-learning materials (Alabay & Baştürk, Citation2021; Alenezi, Citation2020; Sankar et al., Citation2022; Sarker et al., Citation2019), the absence of policies (Li & Li, Citation2023; Mishra et al., Citation2020; Mtebe & Raisamo, Citation2014; Ofosuhene, Citation2022), lack of collaboration (Clark & Wilson, Citation2017; Karim et al., Citation2021; Pujar & Tadasad, Citation2016), government subsidies or donations from charitable organizations (Al-Jarf, Citation2021; Melguizo et al., Citation2016), restricted financial resources (Barteit et al., Citation2020; Cuisia-Villanueva & Núñez, Citation2021; Khave et al., Citation2021), and the deficiency in skills among students and teachers (Farooq et al., Citation2020; Jeyshankar et al., Citation2018; Shah et al., Citation2022) have led to the failure of adopting distance learning.

Due to distance learning employing a student-centred teaching approach (Baudin & Villemur, Citation2009; Dabbagh & Kitsantas, Citation2004; Logan et al., Citation2002; Malczyk, Citation2020; Perreault et al., Citation2002), it is crucial to understand how students perceive their experiences with distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study uncovers two potential risks for students in developing countries during the abrupt transition to distance learning at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic: the potential emergence of learning anxiety and the unfulfillment of learning satisfaction. Furthermore, the researcher posits that the PLE is more critical in distance learning within uncertain situations than the physical learning environment. While the physical environment maintains significance in traditional settings, the flexibility of the digital realm and the psychosocial dynamics it enables have become paramount in shaping the modern educational experience. The capacity of the psychosocial environment to address emotional, social, and motivational aspects emerges as a critical determinant of students’ well-being and success in distance learning. Notably, no prior research has identified the three variables, namely PLE, distance learning anxiety, and distance learning satisfaction, in developing countries and within the setting of uncertain conditions.

Thus, one of the major contributions of this research is the development of a comprehensive model that offers a holistic perspective on the dynamics of distance education in developing countries. This model serves as a valuable theoretical framework for future research and policy development. Understanding the factors influencing the use and acceptance of emergency distance learning will assist curriculum developers in integrating it into hybrid or online programs in the future (Aguilera-Hermida et al., Citation2021). Meanwhile, for educators, it will be a consideration in deciding when to switch between the two methods and how to optimize the use of distance learning. Research on distance learning has been extensively explored in various academic disciplines, including medical education (Al-Balas et al., Citation2020; Bin Mubayrik, Citation2020; Nadezhda, Citation2020), engineering (Galindo et al., Citation2020; Khan & Abid, Citation2021; López Gutiérrez et al., Citation2021), science (Matorevhu, Citation2019; Sung et al., Citation2021; Yorkovsky & Levenberg, Citation2022), Physics (Napsawati & Kadir, Citation2022), biology (Perry et al., Citation2022), language (Arrosagaray et al., Citation2019; Douce, Citation2021; Povoroznyuk et al., Citation2022), architecture (Barbierato et al., Citation2021; Uyaroğlu, Citation2021\\chenassoft\SmartEdit\WatchFolder\NormalProcess\XML\IN\INPROCESS\145), and accounting (Elsayed, Citation2022; Maldonado et al., Citation2023; Mardini & Mah’d, Citation2022). Based on the researcher’s current knowledge, no prior research has analyzed the adoption of distance learning for taxation education in higher education. Consequently, this study focuses on taxation education to address this research gap, considering the unique characteristics of taxation learning.

Taxation education in higher institutions is characterised by its interdisciplinary nature, involving the exploration of complex legal frameworks with distinct tax codes across jurisdictions, setting it apart from the more theoretical aspects of mathematics learning. In contrast to other fields, taxation education is dynamic and continually evolving due to changes in tax laws at various levels, necessitating continuous adaptation and updates. This dynamic nature can pose challenges in student-centred learning environments, particularly in the context of distance learning and under potentially stressful situations. Additionally, taxation education stresses practical application, requiring students to apply tax principles to real-world scenarios and participate in ethical discussions surrounding tax practices during internship activities. The fulfilment of these demands presents challenges, particularly for universities in developing countries that may lack a robust online or virtual internship framework and collaboration with industry practitioners.

This research was conducted in Indonesia, a member of the E7 group, representing seven nations with the highest economic performance among emerging economies. The primary rationale for selecting this research location is grounded in the fact that there is only one public university and one private university offering an undergraduate taxation program in Indonesia. Notably, there is currently no taxation program at the master’s and doctoral levels (https://pddikti.kemdikbud.go.id/). This gap is significant considering the rising demand for professionals with a taxation education background, driven by international business activities and the increasing complexity of tax policies worldwide. The second rationale stems from the discouraging statistics on education in Indonesia. According to OECD data, tertiary education in Indonesia is less prevalent than upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education. In 2021, the proportion of individuals aged 25–34 with tertiary education (18.7%, ranking 42 out of 43) is the lowest among OECD and partner countries. This disparity is vast compared to Korea, the highest-ranking country at 69.3%. This lower position has persisted for the past fifteen years despite a percentage increase from 6.1% in 2005 (OECD, Citation2021). Specifically, the percentage of the population aged 25–64 with a bachelor’s degree or equivalent tertiary education is also among the lowest (5%), slightly surpassing Austria (4.9%) and Slovakia (3.7%) (OECD, Citation2023). The third rationale is rooted in Indonesia’s position as having the fourth lowest percentage of tertiary graduates in business, administration, and law among OECD and partner countries (18.3%, ranking 36/40). This percentage, including taxation within this discipline, is higher than Korea, which holds the lowest position at 14.4% (ranking 40/40). The fourth reason is that teacher attitudes, age, digital skills, and Internet connectivity are crucial success factors for students’ digital learning experiences (UNICEF, Citation2020). However, digital literacy in Indonesia lags behind other Southeast Asian countries despite the launch of many education initiatives by the government and private sector to increase the digital skills of students and teachers (Rumata & Sastrosubroto, Citation2020).

The experience gained during the COVID-19 pandemic provides valuable insights into the potential foundations for adopting TDL in higher education. Three research questions guide the study:

Which dimensions of the PLE significantly influence TDLA and TDLS assuming the undergraduate taxation study program adopts full or hybrid distance learning in the future?

Do uncertainties and lack of preparation, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, cause anxiety in students during TDL, and how does this affect their satisfaction with learning?

To what degree does TDLA mediate the impact of students’ attitudes toward the PLE on their learning satisfaction?

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

The landscape of TDL in developing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic has been marked by complex challenges that demand a comprehensive analysis. Taxation is a highly specialized area of study. It involves an elaborate connection of laws, regulations, and policies at various levels (national, regional, and global) that are subject to frequent changes (Rixen & Unger, Citation2022). Taxation is interdisciplinary because it involves complex laws, economic decisions, and government policies, interacts with international regulations, and has behavioral aspects (Amin, Citation2005; Lamb et al., Citation2004; Lamb & Lymer, Citation2002). This complexity naturally leads to its connection with various academic disciplines (such as business administration, accounting, finance, economics, law, and psychology) to comprehensively understand taxation’s impact. This specialisation demands strong critical thinking, analytical, and problem-solving skills as students dissect tax codes and apply them to practical scenarios (Cull et al., Citation2022; Edeh et al., Citation2022; Mabutha, Citation2017). Additionally, taxation courses incorporate case studies and practical exercises to immerse students in real tax scenarios and intricate tax issues (Van Oordt & Mulder, Citation2016). Furthermore, students must commit to continuous learning and staying up-to-date with the latest developments in tax law, which proves to be challenging amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, taxation education requires students to possess high motivation and self-regulation due to its complex and dynamic nature. In this regard, tax learning necessitates physical facilities and a balanced provision of psychological resources.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that in many developing countries, physical learning facilities are prioritised over students’ psychological aspects and mental health (Akramy, Citation2022; Saeed & Kayani, Citation2019). The PLE assumes a pivotal role due to its influence on the emotional and social dimensions of the learning experience (Kurdi et al., Citation2021). It catalyzes interpersonal interactions and emotional support, addressing the isolation often associated with distance learning. This connectivity fosters a sense of belonging, reduces anxiety (Saeed et al., Citation2015), and enhances learning satisfaction (DiMattio & Hudacek, Citation2020; Smith, Citation2013), ultimately encouraging students to engage in TDL in the future willingly.

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by Deci and Ryan (Citation1985) offers an extensive framework for distance learning research (Chen & Jang, Citation2010). SDT is considered one of the most comprehensive and empirically validated theories of motivation, personality development, and wellness in a social context (Ryan & Deci, Citation2022). The initial emphasis of the theory was on intrinsic motivation, yet it has evolved over the years to include both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). This evolution has given rise to novel insights into well-being, life goals, relationship quality, vitality and depletion, and eudaimonia, among various other subjects (Ryan & Deci, Citation2019). The assumptions of SDT have been empirically confirmed in Western cultures and other developed countries such as Japan and Russia (Chirkovw & Ryan, Citation2001; Ryan & Deci, Citation2002). In the midst of the COVID-19 situation, the SDT also underpins several studies related to online learning or distance learning in developing countries (Chiu, Citation2022; Shah et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2022). However, this theory has not been tested on Indonesian students who exhibit communal and value collectivism characteristics concerning their experiences in engaging in distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

SDT is a suitable framework for understanding and addressing motivation in the context of online learning. SDT is based on recognizing basic human needs, including autonomy (refers to a perception of authority and personal agency), competency (pertains to the feeling of being capable of performing tasks and endeavors), and relatedness (relates to the feeling of inclusion or affiliation with other people) (Rigby & Ryan, Citation2018). The three constructs are closely aligned with the features of distance learning such as computer-mediated communication (Lazou & Tsinakos, Citation2022; Leh, Citation2001), online social interaction (Cholifah et al., Citation2021), and provides a flexible and accessible mode of education (Bušelić, Citation2017; Gornitsky, Citation2011; Veletsianos & Houlden, Citation2019), often involving Self-Paced Learning (Hsieh & Cho, Citation2011). The emphasis on hands-on experience and self-regulated learning renders the three SDT constructs relevant in explaining why distance learning is still considered an inappropriate teaching method for vocational and technical skills (Burns, Citation2023; Shtaleva et al., Citation2021), such as taxation. Based on their experimental studies, Deci and Ryan (Citation2013) also suggest that SDT anticipates various learning outcomes, encompassing performance, perseverance, and satisfaction within courses.

Self-determination refers to the ability of an individual to make choices and decisions based on their freedom to pursue goals, personal preferences and interests, and the ability to be independent and autonomous rather than being controlled by external motivation, such as tangible rewards (Deci, Citation1992, Citation1998). Individuals have the potential to achieve self-determination when their fundamental demands for competence, relatedness, and autonomy are adequately fulfilled (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Ryan and Deci (Citation2000) stated that meeting these needs through daily activities and implementing long-term planning strategies contributes to the promotion of personal growth and well-being, irrespective of whether circumstances are stressful or favorable. In other words, the extent to which individuals demonstrate vitality and mental health is heavily shaped by the existence or absence of environmental factors that facilitate fulfilling their fundamental needs, both in their present situations and along their developmental trajectories.

Therefore, the psychosocial environment serves as a key concept in SDT. Moreover, in situations of uncertainty, the psychosocial environment acts as a buffer, offering emotional reassurance and guidance crucial for students navigating unfamiliar terrain. Conversely, the physical learning environment, although essential in traditional settings, takes a backseat in distance learning scenarios. The absence of a physical classroom diminishes its significance, particularly in contexts marked by uncertainty. The physical space no longer serves as the primary locus of learning, and its attributes, such as seating arrangements or classroom infrastructure, become less relevant (Pratidhina et al., Citation2021; Zhao et al., Citation2021). Instead, the focus shifts to digital platforms and the pedagogical approaches employed, where the psychosocial dynamics hold a more significant influence.

The PLE is defined as all social and psychological factors involved in the learning process that influence students’ learning experiences and outcomes (Cleveland & Fisher, Citation2014). The psychosocial environment has three dimensions: personal development, relationships, and system maintenance and change (Moos, Citation1980). Personal development focuses on the paths of personal growth and self-improvement, encompassing students’ autonomy, cognitive, emotional, and connection with the learning material. On the other hand, the relationships dimension emphasises the character and strength of interpersonal connections within the learning environment, the engagement of individuals, and their emotions of being affiliated, accepted and supported. Lastly, the system maintenance and change addresses the aspects of the learning environment, such as policies, procedures, and adaptability to alterations, involving the organisation of students and educators, timetabling, and oversight of the learning process. Gustafsson et al. (Citation2010) identified two primary dimensions within the psychosocial environment: (1) elements associated with the relationships between teachers and students, as well as among students themselves, along with the overall social climate within the educational environment, and (2) elements associated with individual perceived academic stress and failures.

This research analyses the PLE using the Distance Education Learning Environments Survey (DELES) developed by Walker and Fraser (Citation2005). DELES is a Likert-type survey that has been carefully crafted based on previous tools and expert opinions to ensure it covers essential aspects for successful distance education (Yousry & Azab, Citation2022). Its adaptability and applicability across different disciplines and contexts make it a versatile tool for assessing distance learning environments (Carver, Citation2014; Estriegana et al., Citation2021). Walker and Fraser (Citation2005) divide the PLE into 7 scales, including (1) instructor support (the level of support students receive from an instructor); (2) student interaction and collaboration (interactions with other students); (3) personal relevance (the relevance of the material taught in the courses); (4) authentic learning (the reality of content covered in the class); (5) active learning (how actively students manage their learning); (6) student autonomy (how much control students take for their learning); and (7) enjoyment (how satisfied students are in an online class).

Instructor support plays a pivotal role in shaping students’ perception of autonomy (Liu et al., Citation2021), providing the necessary scaffolding to navigate their learning journey independently. Through timely feedback and clear guidance, instructors empower learners to take ownership of their education, reducing anxiety and fostering satisfaction. This alignment with SDT's emphasis on autonomy highlights the importance of students feeling self-determined in their actions. Similarly, student interaction and collaboration contribute significantly to the dimension of relatedness within SDT. By engaging in collaborative activities and discussions, students develop a sense of connection and belonging within the learning community (Chang, Citation2012; Peacock et al., Citation2020), mitigating feelings of isolation and enhancing satisfaction. Moreover, these interactions facilitate the internalization of intrinsic motivation as students derive satisfaction from meaningful exchanges and shared learning experiences. Furthermore, personal relevance and authentic learning experiences cater directly to the dimension of competence in SDT. When students perceive the material as relevant and applicable to their academic or professional aspirations, they feel competent and motivated to engage with the content (Bundick et al., Citation2014), ultimately reducing anxiety and promoting satisfaction (Ryan & Deci, Citation2016). Additionally, exposure to authentic tax scenarios allows students to develop practical skills and knowledge (Morgan et al., Citation2022), enhancing their competence and intrinsic motivation through internalising meaningful learning experiences.

Active learning and student autonomy are inherently intertwined with all three dimensions of SDT – autonomy, competence, and relatedness. By actively engaging with course material and assuming control over their learning process, students experience a sense of autonomy and agency crucial for fostering intrinsic motivation (Lee & Hannafin, Citation2016; Reeve, Citation2012). As they navigate their learning journey independently and make decisions aligned with their goals, students internalise the value of learning, leading to greater satisfaction and reduced anxiety. Moreover, enjoyment, as a key component of the PLE, reinforces the internalisation of intrinsic motivation in SDT. When learning is enjoyable and fulfilling, students are more likely to engage willingly and persistently, driven by their inherent interests and curiosity (Fang & Tang, Citation2021). This intrinsic motivation stemming from the enjoyment of learning serves as a powerful catalyst for satisfaction in TDL.

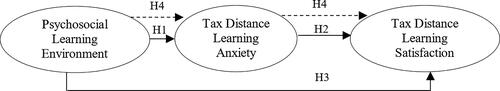

This research posits that TDL serves as a mediator in shaping student satisfaction, contingent upon their perceptions of the PLE. Firstly, anxiety diminishes autonomy as students may feel a loss of control over their learning process, relying more on extrinsic motivation like instructor guidance (Chiu, Citation2022). Second, anxiety undermines competence by inducing self-doubt and reducing self-efficacy, impacting students’ abilities to engage with tax-related concepts. Additionally, anxiety hinders relatedness by exacerbating feelings of isolation, limiting opportunities for meaningful interactions with peers and instructors (Zeidner, Citation2014). These disruptions to psychological needs diminish overall satisfaction with the learning experience. Recognising and addressing anxiety is crucial for creating a supportive environment that increases satisfaction with TDL. Based on SDT, this research proposes a research model as in .

3. Research method

This study utilises a quantitative method in conjunction with a survey-based research approach. This study used a questionnaire to collect cross-sectional data during the odd semester of the 2022/2023 academic year. Cross-sectional studies capture a specific moment in time, providing a snapshot of conditions or characteristics at that particular time. This can be valuable for understanding the prevalence and characteristics of a population at a given point, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Von Elm et al., Citation2007). Rindfleisch et al. (Citation2008) emphasise that cross-sectional data are suitable for investigations centred on concrete and externally focused constructs, involving samples comprising highly educated individuals and firmly anchored in theoretical foundations. The research period is determined based on the research objectives of understanding students’ overall experiences, including anxiety and satisfaction, in distance learning. Moreover, the absence of substantial university responses during the two-year pandemic, continued reliance on Zoom, lack of Learning Management System development blueprints, and insufficient instructor training ensure that the data obtained comprehensively captures the phenomenon. To mitigate the risk of common method bias, the researcher implemented several procedures recommended by Jordan and Troth (Citation2020), including informing respondents of the research objectives and instructions, improving scale item clarity, removing common scale properties, and including reversed coded items. Researchers distributed the questionnaires both in person and online to expedite data gathering. The questionnaire has two sections, one on research variables and the other focusing on respondent demographics. The questionnaire questions for the 7 exogenous variables that reflect the concept of PLE were taken from Carver (Citation2014). The number of question items for each variable is as follows: instructor support (8 items), student interaction and collaboration (6 items), personal relevance (7 items), authentic learning (5 items), active learning (3 items), student autonomy (5 items), and enjoyment of online learning (7 items). Meanwhile, the 7 question items for the TDLA variable were adopted from research by Abdous (Citation2019) and Spitzer et al. (2006). Researchers also refer to the research of Abdous (Citation2019) and Abdous and Yen (Citation2010) to develop nine question items for the TDLS. The question items for all variables are measured using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, where item one represents “strongly disagree,” and item five indicates “strongly agree.” All undergraduates enrolled in the taxation program at Brawijaya University constitute the target population for this investigation. Specific information is required in this research (Bougie & Sekaran, Citation2019); therefore, a judgment sampling method is applied to select the 469 samples, which is non-probability in nature. The criteria for selection require participants to have an active status throughout the research period, and participants must be enrolled in distance learning courses during the COVID-19 pandemic. We exclude active students who did not attend lectures during the COVID-19 pandemic as a sample, such as final semester students working on their thesis, because their experiences and perceptions of the PLE and anxiety related to distance learning may differ significantly from those who attended classes. Thus, TDLS will be evaluated in a biassed manner. By employing Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling, the data in this study are interpreted and analysed according to a path analysis model.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Respondent characteristics

Analysing respondent characteristics before scrutinising hypothesis test results is crucial in the research process. It enhances our research findings’ credibility, validity, and robustness, enabling researchers to draw more accurate and insightful conclusions. Out of the 469 responders with accurate data (), the majority were women, namely 70.15% (329). Meanwhile, based on age, 53.09% (249) were 18–20 years old and 45.63% (214) were 21–23 years old. Each grade group has adequate representation, namely freshman (31.56%), sophomore (31.34%), junior (21.11%), and senior (15.55%). During this study, most participants (49.47%) had a cumulative accomplishment index beyond 3.51, while 45.20% had an index ranging from 3.01 to 3.50. Only a small number of respondents had a cumulative achievement index below 3.0. In other words, most of the participants possess commendable academic aptitude.

Table 1. Respondent characteristics.

To provide a comprehensive understanding of students’ behaviour during TDL, the researcher also explored the characteristics of their learning resources. According to , 187 (39.87%) and 172 (36.67%) students spent 5–7 h and 3–5 h, respectively, engaging in TDL. Meanwhile, 48 students (10.23%) allocated only 1–3 h for TDL, and 6 students (1.28%) had to dedicate more than 10 h. The seamless operation of TDL relies heavily on the availability of adequate supporting devices for students. Despite the reassuring fact that the majority of students claimed access to supporting devices (375 students or 79.96%), 91 students (9.40%) reported non-functional devices or the need to share them with others (3 students or 0.64%). Laptops emerged as the most widely utilised device among students, whether functioning optimally (92%) or otherwise (73.63%).

Table 2. Characteristics of student TDL resources.

A total of 232 students (49.47%) expressed the need to spend between 100,000 and 250,000 IDR per month for TDL, while 131 students (27.93%) required expenses exceeding 250,000 to 500,000 IDR. A significant financial need was expressed by 10 students (2.31%), specifying expenses exceeding 1,000,000 IDR per month. Conversely, 67 students (14.29%) demonstrated a monthly requirement for expenses below 100,000 IDR. The presence of an uncertain situation, posing a threat to the continuity of the learning process in higher education, has prompted not only the government but also universities or specific programs to provide assistance in the form of devices or subsidies. Out of the respondents, 359 (75.55%) stated that they received assistance in the form of internet data packages, while the remaining did not. Meanwhile, 206 respondents (43.92%) reported finding the facilities offered by the undergraduate taxation study program quite helpful, while 151 respondents (32.20%) said that the facilities were helpful during the COVID-19 epidemic. However, it is noteworthy that some students feel that the facilities provided by the program are not helpful (12.15%) and are very unhelpful (3.20%).

It is critical for meeting the TDLS and mitigating TDLA that students have adequate discretionary time to engage in activities such as face-to-face learning and interaction with peers. As indicated by the data in , a considerable percentage of students have sufficient time to engage in social activities, spend time with family and friends, and pursue hobbies. More specifically, 248 students (52.88%) affirm having sufficiently allocated time, while 117 students (24.95%) report having adequate time for socialising with friends. These figures are higher for time availability for family gatherings, where 132 students (28.14%) indicate sufficient time and 318 students (67.80%) report having adequate time. The availability of time for pursuing hobbies also surpasses that for socialising with friends during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 289 (61.62%) and 142 (30.28%) students expressing adequacy. However, TDL hinders students from having sufficient time to participate in competitions or extracurricular activities. Specifically, 201 (42.86%) and 228 (48.61%) students state having inadequate and sufficiently adequate time, respectively, for participating in competitions or student activities. Only 40 students (8.53%) claim to have sufficient time to participate in competitions. Furthermore, 107 students (22.81%) express insufficient availability of time to participate in extracurricular activities, while 276 students (58.85%) consider their time to be adequately available.

Table 3. Characteristics of leisure time availability.

4.2. Students’ perception of distance learning

Can TDL be implemented in the future? This question can be addressed, in part, by analysing students’ preferences for learning methods during the COVID-19 pandemic. illustrates that while academic programs consider the abrupt transition policy from face-to-face learning to distance learning as the best option during the pandemic, most students (59.91%) opt for blended learning if feasible. Remarkably, 98 (20.90%) students persist in favouring traditional face-to-face lectures, with only 90 (19.90%) expressing suitability for distance learning. In further detail, over 50% of respondents across all groups, based on respondent characteristics and availability of leisure time characteristics, agree that blended learning aligns with their future learning needs. Meanwhile, face-to-face learning remains the primary choice for students who perceive TDL as highly ineffective (56.00%) and express complete dissatisfaction with it (76.00%). Nevertheless, those who affirm the effectiveness (64.71%), minimal anxiety (57.14%), and high satisfaction (61.22%) with TDL opt for it as their preferred learning method in the future.

Table 4. TDL perception.

4.3. Assessment of measurement model

demonstrates that all indicators associated with each variable in this research have successfully shown discriminant validity. This is demonstrated by cross-loading values exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.7. In addition to the construct validity test, this research also tested construct reliability through criteria such as composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha. The results of the construct reliability test are also satisfied, with both composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.70. The Average Variance Extracted values for the nine constructs are greater than 0.5, ranging from 0.557 to 0.734, indicating that convergent validity is accepted, as claimed by Hair et al. (Citation2019).

Table 5. Construct reliability and validity analysis.

4.4. Assessment of structural model

The inner or structural model is tested by examining the R-square, which measures the model’s goodness of fit. presents the R-square values for the TDLA, yielding a value of 0.070. This R-square value indicates that 7% of the variance in TDLA can be attributed to instructor support, student interaction and collaboration, personal relevance, authentic learning, active learning, student autonomy, and enjoyment of online learning. Unexplored variables influence the remaining 93%. In contrast, the R-square value for TDLS is 0.454. This implies that 45.4% of the student’s satisfaction with TDL is influenced by seven variables that encapsulate the PLE and TDLA. The Q-Square Predictive Relevance is also applied to gauge how well the model conservatively produces values and parameter estimates. The magnitude of Q-Square is analogous to the coefficient of total determination in path analysis. The Q2 value ranges from 0< Q2 < 1, where a value closer to 1 indicates a more robust model. From the computed results, the Q-Square value is determined to be 0.4922, suggesting a substantial level of predictive relevance in the model.

Table 6. Result of R2 and predictive relevance.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

The results of the hypothesis testing indicate that five research hypotheses support the SDT, while other hypotheses contradict the theory. This is evidenced by the t-statistics values from the t-table exceeding 1.960, with corresponding p-values below 0.05. Additionally, reveals that H1.1 and H2.1 exhibit positive Path Coefficient (β) values, namely 0.155 and 0.122, respectively. This signifies that instructor support positively influences TDLA and TDLS. In contrast, H1.7 has a negative β value (−0.185), and H2.7 has a positive β value (0.581). Thus, enjoyment of online learning negatively affects TDLA but positively affects TDLS. Another accepted hypothesis in this study is H1.5, which has a negative β value (−0.142). These findings substantiate that active learning has a negative impact on TDLA.

Table 7. Hypotheses testing direct and indirect effects.

5. Discussion

This research proves that instructor support directly influences TDLA positively. SDT posits that the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness drives human behavior (Deci et al., Citation1994). In guaranteeing the quality of distance learning in taxation implemented unexpectedly amid the COVID-19 pandemic, if instructor support becomes overly prescriptive or controlling, it may diminish a learner’s sense of autonomy (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). This controlled support may include highly structured assignments, rigid deadlines, or a lack of choice in the learning process. When learners feel that their autonomy is restricted, it can lead to anxiety, as they may perceive a lack of control over their learning environment (Deci & Ryan, Citation2013; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Additionally, high-quality instructor support may involve setting high standards and expectations for learners, which, while intended to foster competence, can also lead to performance pressure. If learners perceive that their competence is constantly being evaluated and their instructors closely monitor their progress, it can exacerbate anxiety about meeting these expectations. Furthermore, instructor support in distance learning, involving interactions with instructors and peers, can increase social pressure and competition, affecting learners’ sense of relatedness (Mohammed et al., Citation2021). This anxiety may arise from perceiving these relationships as judgmental or competitive. During the COVID-19 pandemic, instructor support is excessive and focuses on external rewards or punishments, making learners extrinsically motivated. This shift can reduce their intrinsic motivation, leading to anxiety when the external support is removed or if they perceive a risk of failing to meet external expectations.

However, this research highlights conflicting facts, wherein high-quality instructor support fosters TDLS despite eliciting significant anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. One potential explanation for this situation is the concept of cognitive dissonance. Despite the increased support, students may still experience anxiety related to the demands of taxation-focused distance learning. Taxation is a complex and technical subject, and some students may find the content challenging even with support. This can lead to heightened anxiety. The discrepancy between the expectation of a highly supportive environment and the reality of experiencing anxiety due to tax-related challenges can create cognitive dissonance. This dissonance, in turn, can lead to heightened awareness of the anxiety, making it seem more pronounced (Chen & Yan, Citation2023). Paradoxically, students may express higher satisfaction due to the support they receive and higher anxiety due to the dissonance. Their satisfaction is tied to the quality of instructor support, while their anxiety is related to the challenges of the subject matter.

The validity of the hypothesis, which posits a direct negative influence of active learning on TDLA, reinforces the rationale for why instructor support has a favourable impact on TDLA in this study. Active learning gives learners greater autonomy, allowing them to actively engage in the learning process and make meaningful choices, thus fostering a sense of control over their academic endeavours (Ryan & Deci, Citation2016). This heightened autonomy aligns with SDT, reducing TDLA as individuals perceive increased agency in navigating complex tax-related concepts. Furthermore, active learning strategies enhance perceived competence by necessitating active engagement and problem-solving (Ryan & Deci, Citation2019). Learners who tackle tax-related challenges through interactive methods experience a sense of mastery and accomplishment. This elevation in perceived competence, under SDT, acts as a counterforce to the anxiety associated with intricate tax concepts. Additionally, active learning fosters a sense of relatedness and social connection among learners, creating a supportive learning environment through collaborative activities and group projects (Rigby & Ryan, Citation2018). According to the SDT, this social cohesion fulfils the need for relatedness, serving as a protective factor against TDLA and fostering a sense of community and shared learning experiences.

This research also demonstrates that online learning enjoyment is crucial in alleviating TDLA and enhancing TDLS. According to the SDT, when students are free to make choices and control their learning process (autonomy), they are more likely to feel invested and engaged in the online learning experience (Fang & Tang, Citation2021), leading to increased enjoyment. Moreover, when students feel a sense of belonging and connection with their peers and instructors (relatedness), they are more likely to feel supported and motivated to participate in online learning activities, reducing anxiety. Finally, when students perceive themselves as capable of successfully completing tasks and achieving learning goals (competence), they are more likely to have a positive learning experience and increased satisfaction (Heckel & Ringeisen, Citation2019). Hence, as enjoyment increases, anxiety decreases, and satisfaction increases, forming a feedback loop that promotes a positive online learning experience for students.

The apparent lack of influence of student interaction and collaboration, personal relevance, authentic learning, and student autonomy on TDLA and TDLS during the COVID-19 pandemic may stem from multifaceted dynamics inherent in the tax educational landscape during this unprecedented global crisis. The overwhelming shift to distance learning during the pandemic has reshaped the traditional educational milieu, altering the dynamics of student interaction and collaboration. The virtual nature of TDL might have impeded spontaneous interactions and collaborative endeavors among students, contributing to a perceived disconnect and diminished impact on learning satisfaction. Additionally, the abrupt transition to online platforms may have hindered the establishment of personal relevance in educational content as students grappled with adapting to a new mode of learning delivery (Bishaw et al., Citation2022). Moreover, the challenges posed by the pandemic may have overshadowed the potential benefits of authentic learning experiences. The exigencies of distance learning might have limited opportunities for hands-on, real-world applications, diminishing the authenticity of the educational experience and, consequently, its impact on TDLS. Similarly, the constraints imposed by the pandemic could have constrained the scope for student autonomy, as the shift to online platforms may have necessitated more structured and controlled instructional approaches. The socio-economic disruptions caused by the pandemic might also have introduced external factors that overshadowed the impact of SDT factors on TDLA and TDLS (Gaidelys et al., Citation2022). Economic uncertainties, health concerns, and technological disparities could have influenced students’ perceptions and experiences, creating a complex interplay of variables that dilutes the direct influence of student interaction, personal relevance, authentic learning, and student autonomy on TDL outcomes. This explanation is also relevant to explain why PLE variables have a small influence on TDA. The results of a Systematic Literature Review by Jehi et al. (Citation2022) show that more than one-third of students suffered from anxiety in the early stages of the pandemic, and the most contributing factors were financial difficulties, the obligation to work full-time, quarantine isolation, concerns about infection for themselves and others, uncertainty about the future, and poor sleep quality. This implies that students give more consideration to external factors outside the educational context during the transition to TDL.

In TDL, the PLE variables are key to these motivational factors. This research examines the influence of three primary PLE variables: instructor support, active learning, and enjoyment of online learning. It is conceivable that TDLA, while a significant aspect, may not independently drive satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Instead, its influence could be contingent on the prevailing psychosocial context and the learner’s perception of autonomy, competence, and relatedness within the educational setting. Individual differences could also influence the absence of a direct link between TDLA and TDLS in coping mechanisms, resilience, and adaptability. Some learners may effectively navigate and mitigate anxiety, thus preserving overall satisfaction in the TDL environment. Furthermore, the complex interaction of multiple psychological processes can explain the lack of a mediating impact. A complex interweaving of cognitive, emotional, and motivational components likely shapes TDLS. TDLA might be one among several factors influencing learners’ cognitive and emotional states, but other variables within the SDT framework may overshadow its direct mediation role.

6. Conclusion

Rooted in SDT, this study reveals that if unaddressed, autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs lead to anxiety amid sudden changes like the shift to distance learning. The paradoxical discovery that high-quality instructor support induces anxiety but fosters satisfaction highlights cognitive dissonance. Aligned with the theory, active learning mitigates anxiety by providing autonomy, enhancing competence, and fostering relatedness. Notably, student interaction, collaboration, relevance, authenticity, and autonomy have muted impacts during the pandemic. The absence of a direct link between anxiety and satisfaction underscores the multifaceted nature of learner experiences, emphasising the need for a comprehensive understanding of the PLE during disruptions like COVID-19. Future research endeavours should continue to explore and unpack the intricacies of these dynamics, considering the evolving educational landscape and its impact on learner experiences. Moreover, the complex dynamics introduced by the sudden shift to distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic may limit the generalizability of findings. Hence, future research should explore the longitudinal effects beyond the pandemic period to advance our understanding of TDL. A comparative analysis of diverse educational settings and cultural contexts could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the PLE's impact. As a subject matter, taxation may introduce unique challenges and opportunities that require more understanding, so it becomes crucial to consider testing other variables in the model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Priandhita Sukowidyanti Asmoro

Priandhita Sukowidyanti Asmoro is an assistant professor in the Taxation Study Program at the Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Administrative Sciences, Universitas Brawijaya. She actively contributes to developing the taxation curriculum and enhancing tax awareness through educational initiatives, leveraging her previous roles as the Secretary of the Taxation Study Program and the Chair of the Tax Center at the same institution where she teaches. Having an interdisciplinary perspective, she is open to collaborating on research projects aligned with her research interests, encompassing tax policy, tax behaviour, and environmental tax.

References

- Abdous, M. H. (2019). Influence of satisfaction and preparedness on online students’ feelings of anxiety. The Internet and Higher Education, 41, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.01.001

- Abdous, M. H., & Yen, C. J. (2010). A predictive study of learner satisfaction and outcomes in face-to-face, satellite broadcast, and live video-streaming learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(4), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.04.005

- Abou-Khalil, V., Helou, S., Khalifé, E., Chen, M. A., Majumdar, R., & Ogata, H. (2021). Emergency online learning in low-resource settings: Effective student engagement strategies. Education Sciences, 11(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010024

- Aguilera-Hermida, A. P., Quiroga-Garza, A., Gómez-Mendoza, S., Del Río Villanueva, C. A., Avolio Alecchi, B., & Avci, D. (2021). Comparison of students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19 in the USA. Mexico. Peru. and Turkey. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 6823–6845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10473-8

- Ahmed, S. A., Hegazy, N. N., Abdel Malak, H. W., Cliff Kayser, W., Elrafie, N. M., Hassanien, M., Al-Hayani, A. A., El Saadany, S. A., Ai-Youbi, A. O., & Shehata, M. H. (2020). Model for utilizing distance learning post COVID-19 using (PACT)™ a cross sectional qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 400. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02311-1

- Akramy, S. A. (2022). Shocks and aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic in Afghanistan higher education institutions. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 9(1), 2029802. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2022.2029802

- Aktaruzzaman, M., & Plunkett, M. (2016). An innovative approach toward a comprehensive distance education framework for a developing country. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(4), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1227098

- Alabay, S., & Baştürk, M. (2021). Development. implementation and evaluation of e-learning materials for FFL with Adobe Captivate Software. International Education Studies, 14(6), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v14n6p59

- Al-Balas, M., Al-Balas, H. I., Jaber, H. M., Obeidat, K., Al-Balas, H., Aborajooh, E. A., Al-Taher, R., & Al-Balas, B. (2020). Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 341. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02257-4

- Alenezi, A. (2020). The role of e-learning materials in enhancing teaching and learning behaviors. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 10(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2020.10.1.1338

- Al-Jarf, R. (2021). Investigating digital equity in distance education in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Conference Proceedings of» eLearning and Software for Education «(eLSE), vol. 17(01) (pp. 11–20).

- Al-Smadi, A. M., Abugabah, A., & Al Smadi, A. (2022). Evaluation of E-learning experience in the light of the Covid-19 in higher education. Procedia Computer Science, 201, 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.03.051

- Amin, M. (2005). Taxation: An interdisciplinary approach to research. Canadian Tax Journal, 53(4), 1162–1163.

- Arrosagaray, M., González-Peiteado, M., Pino-Juste, M., & Rodríguez-López, B. (2019). A comparative study of Spanish adult students’ attitudes to ICT in classroom, blended and distance language learning modes. Computers & Education, 134, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.016

- Baggaley, J. (2008). Where did distance education go wrong? Distance Education, 29(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802004837

- Barbierato, E., Campanile, L., Gribaudo, M., Iacono, M., Mastroianni, M., & Nacchia, S. (2021). Performance evaluation for the design of a hybrid cloud based distance synchronous and asynchronous learning architecture. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory, 109, 102303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpat.2021.102303

- Barik, N., & Karforma, S. (2012). Risks and remedies in e-learning system. arXiv preprint arXiv:1205.2711.

- Baro, E. E., Joyce Ebiagbe, E., & Zaccheaus Godfrey, V. (2013). Web 2.0 tools usage: A comparative study of librarians in university libraries in Nigeria and South Africa. Library Hi Tech News, 30(5), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-04-2013-0021

- Barron, R. M., Cobo, C., Munoz-Najar, A., & Sanchez, C. I. (2021). Remote learning during the global school lockdown. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/160271637074230077/pdf/Remote-Learning-During-COVID-19-Lessons-from-Today-Principles-for-Tomorrow.pdf

- Barteit, S., Guzek, D., Jahn, A., Bärnighausen, T., Jorge, M. M., & Neuhann, F. (2020). Evaluation of e-learning for medical education in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 145, 103726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103726

- Baudin, V., & Villemur, T. (2009). Student centered distance learning experiments over a communication and collaboration platform. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 6(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/17415650910965209

- Beese, J. (2014). Expanding learning opportunities for high school students with distance learning. American Journal of Distance Education, 28(4), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2014.959343

- Bin Mubayrik, H. F. (2020). Exploring adult learners’ viewpoints and motivation regarding distance learning in medical education. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 11, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S231651

- Bishaw, A., Tadesse, T., Campbell, C., & Gillies, R. M. (2022). Exploring the unexpected transition to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic in an Ethiopian-public-university context. Education Sciences, 12(6), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060399

- Bougie, R., & Sekaran, U. (2019). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bozkurt, A., & Sharma, R. C. (2020). Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to CoronaVirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), i–vi.

- Bundick, M. J., Quaglia, R. J., Corso, M. J., & Haywood, D. E. (2014). Promoting student engagement in the classroom. Teachers College Record, 116(4), 1–34.

- Burns, M. (2023). Distance education for teacher training: Modes, models, and methods. Education Development Center, Inc.

- Bušelić, M. (2017). Distance Learning–concepts and contributions. Oeconomica Jadertina, 2(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.15291/oec.209

- Carver, D. L. (2014). Analysis of student perceptions of the psychosocial learning environment in online and face-to-face career and technical education courses. Old Dominion University.

- Chang, H. (2012). The development of a learning community in an e-learning environment. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 7(2), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.5172/ijpl.2012.7.2.154

- Chen, K. C., & Jang, S. J. (2010). Motivation in online learning: Testing a model of self-determination theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(4), 741–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.01.011

- Chen, Q., & Panda, S. (2013). Needs for and utilization of OER in distance education: A Chinese survey. Educational Media International, 50(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2013.795324

- Chen, R., & Yan, H. (2023). Effects of knowledge anxiety and cognitive processing bias on brand avoidance during COVID-19: The mediating role of attachment anxiety and herd mentality. Sustainability, 15(8), 6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086978

- Chen, Y., & He, W. (2013). Security risks and protection in online learning: A survey. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(5), 108–127. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v14i5.1632

- Chiu, T. K. (2022). Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(sup1), S14–S30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998

- Chirkov, V. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Parent and teacher autonomy-support in Russian and US adolescents: Common effects on well-being and academic motivation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 618–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032005006

- Cholifah, P. S., Nuraini, N. L. S., Mahanani, P., & Rini, T. A. (2021, September). Designing online social interaction instrument based on assessment as learning [Paper presentation]. In 2021 7th International Conference on Education and Technology (ICET) (pp. 241–246). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICET53279.2021.9575067

- Clark, C. H., & Wilson, B. P. (2017). The potential for university collaboration and online learning to internationalise geography education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 41(4), 488–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2017.1337087

- Cleveland, B., & Fisher, K. (2014). The evaluation of physical learning environments: A critical review of the literature. Learning Environments Research, 17(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-013-9149-3

- Cooper, L. (2000). Online courses: Tips for making them work. Journal of Instructional Science and Technology, 3(3), 20–25.

- Cuisia-Villanueva, M. C., & Núñez, J. L. (2021). A study on the impact of socio-economic status on emergency electronic learning during the coronavirus lockdown. FDLA Journal, 6(1), 6.

- Cull, M., McLaren, J., Freudenberg, B., Vitale, C., Castelyn, D., Whait, R., Kayis-Kumar, R., Le, V., & Morgan, A. (2022). Work-integrated learning for international students: Developing self-efficacy through the Australian national tax clinic program. Journal of the Australasian Tax Teachers Association, 17(1), 22–56.

- Dabbagh, N., & Kitsantas, A. (2004). Supporting self-regulation in student-centered web-based learning environments. In International Journal on E-Learning, (3(1), 40–47.

- Deci, E. L. (1992). The relation of interest to the motivation of behavior: A self-determination theory perspective. In K. A. Renninger, S. Hidi, & A. Krapp (Eds.), The role of interest in learning and development (pp. 43–70). Erlbaum.

- Deci, E. L. (1998). The relation to interest to motivation and human needs: the self-determination theory viewpoint. IPN Press.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. In Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior (pp. 11–40). Springer.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Deci, E. L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B. C., & Leone, D. R. (1994). Facilitating internalization: The self‐determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality, 62(1), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00797.x

- DiMattio, M. J. K., & Hudacek, S. S. (2020). Educating generation Z: Psychosocial dimensions of the clinical learning environment that predict student satisfaction. Nurse Education in Practice, 49, 102901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102901

- Douce, C. (2021). Distance learning and language learning. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 36(1), 2–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2020.1863204

- Edeh, N. I., Ugwoke, E. O., & Anaele, E. O. (2022). Effects of innovative pedagogies on academic achievement and development of 21st-century skills of taxation students in colleges of education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 59(5), 533–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2021.1919174

- Elsayed, N. (2022). Belief perseverance in students’ perceptions of accounting in a distance-learning environment: evidence from a GCC university. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 13(5), 849–869. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-12-2021-0406

- Estriegana, R., Medina-Merodio, J. A., Robina-Ramírez, R., & Barchino, R. (2021). Analysis of cooperative skills development through relational coordination in a gamified online learning environment. Electronics, 10(16), 2032. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10162032

- Ezra, O., Cohen, A., Bronshtein, A., Gabbay, H., & Baruth, O. (2021). Equity factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Difficulties in emergency remote teaching (ert) through online learning. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7657–7681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10632-x

- Fang, F., & Tang, X. (2021). The relationship between Chinese English major students’ learning anxiety and enjoyment in an English language classroom: A positive psychology perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 705244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.705244

- Farid, S., Ahmad, R., Niaz, I. A., Arif, M., Shamshirband, S., & Khattak, M. D. (2015). Identification and prioritization of critical issues for the promotion of e-learning in Pakistan. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.037

- Farooq, F., Rathore, F. A., & Mansoor, S. N. (2020). Challenges of online medical education in Pakistan during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons-Pakistan: JCPSP, 30(6), 67–69. https://doi.org/10.29271/jcpsp.2020.Supp1.S67

- Ferri, F., Grifoni, P., & Guzzo, T. (2020). Online learning and emergency remote teaching: Opportunities and challenges in emergency situations. Societies, 10(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040086

- Fong, A. C. M., & Hui, S. C. (2001). Low-bandwidth Internet streaming of multimedia lectures. Engineering Science & Education Journal, 10(6), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1049/esej:20010601

- Gaidelys, V., Čiutienė, R., Cibulskas, G., Miliauskas, S., Jukštaitė, J., & Dumčiuvienė, D. (2022). Assessing the socio-economic consequences of distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 12(10), 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100685

- Galindo, C., Gregori, P., & Martínez, V. (2020). Using videos to improve oral presentation skills in distance learning engineering master’s degrees. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 51(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2019.1662118

- Gornitsky, M. (2011). Distance education: Accessibility for students with disabilities. Distance Learning, 8(3), 47.

- Guo, J., Li, C., Zhang, G., Sun, Y., & Bie, R. (2020). Blockchain-enabled digital rights management for multimedia resources of online education. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 79(15–16), 9735–9755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-08059-1

- Gurajena, C., Mbunge, E., & Fashoto, S. (2021). Teaching and learning in the new normal: Opportunities and challenges of distance learning amid COVID-19 pandemic. Available at SSRN 3765509.

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Allodi, M. W., Åkerman, B. A., Eriksson, C., Eriksson, L., Fischbein, S., Granlund, M., Gustafsson, P., Ljungdahl, S., Ogden, T., & Persson, R. S. (2010). School, learning and mental health. A systematic review. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. https://www.kva.se/globalassets/vetenskap_samhallet/halsa/utskottet/kunskapsoversikt2_halsa_eng_2010.pdf

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Heckel, C., & Ringeisen, T. (2019). Pride and anxiety in online learning environments: Achievement emotions as mediators between learners’ characteristics and learning outcomes. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35(5), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12367

- Heidrich, L., Barbosa, J. L. V., Cambruzzi, W., Rigo, S. J., Martins, M. G., & dos Santos, R. B. S. (2018). Diagnosis of learner dropout based on learning styles for online distance learning. Telematics and Informatics, 35(6), 1593–1606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.04.007

- Hodges, C. B., Moore, S., Lockee, B. B., Trust, T., & Bond, M. A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/104648/facdev-article.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Hofmarcher, T. (2021). The effect of education on poverty: A European perspective. Economics of Education Review, 83, 102124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102124

- Hondonga, J., Chinengundu, T., & Maphosa, P. K. (2021). Online teaching of TVET courses: An analysis of Botswana private tertiary education providers’ responsiveness to the COVID-19 pandemic learning disruptions. The on-line Journal of Technical and Vocational Education and Training in Asia, 16, 1–16.

- Hsieh, P. A. J., & Cho, V. (2011). Comparing e-Learning tools’ success: The case of instructor–student interactive vs. self-paced tools. Computers & Education, 57(3), 2025–2038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.05.002

- Ismaili, Y. (2021). Evaluation of students’ attitude toward distance learning during the pandemic (Covid-19): A case study of ELTE university. On the Horizon, 29(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-09-2020-0032

- Jehi, T., Khan, R., Dos Santos, H., & Majzoub, N. (2022). Effect of COVID-19 outbreak on anxiety among students of higher education; A review of literature. Current Psychology, 42(20), 17475–17489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02587-6

- Jeyshankar, R., Nachiappan, N., & Lavanya, A. (2018). Analysis of gender differences in information retrieval skills in the use of electronic resources among post graduate students of Alagappa University. Tamil Nadu. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1–19.

- Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2020). Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Australian Journal of Management, 45(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871976

- Karim, N., Rybarczyk, M. M., Jacquet, G. A., Pousson, A., Aluisio, A. R., Bilal, S., Moretti, K., Douglass, K. A., Henwood, P. C., Kharel, R., Lee, J. A., MenkinSmith, L., Moresky, R. T., Gonzalez Marques, C., Myers, J. G., O'Laughlin, K. N., Schmidt, J., & Kivlehan, S. M. (2021). COVID‐19 pandemic prompts a paradigm shift in global emergency medicine: Multidirectional education and remote collaboration. AEM Education and Training, 5(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10551

- Khan, Z. H., & Abid, M. I. (2021). Distance learning in engineering education: Challenges and opportunities during COVID-19 pandemic crisis in Pakistan. The International Journal of Electrical Engineering & Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020720920988493

- Khave, L. J., Vahidi, M., Hasanzadeh, T., Arab-Ahmadi, M., & Karamouzian, M. (2021). A student-led medical education initiative in Iran: Responding to COVID-19 in a resource-limited setting. Academic Medicine, 96(1), e2–e2. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003802

- Kurdi, V., Joussemet, M., & Mageau, G. A. (2021). A self-determination theory perspective on social and emotional learning. In Motivating the sel field forward through equity (pp. 61–78). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Lamb, M., & Lymer, A. (2002). Taxation in an accounting context: Future prospects and interdisciplinary perspectives. In Taxation: Critical perspectives on the world economy (pp. 287–316). Routledge.

- Lamb, M., Lymer, A., Freedman, J., & James, S. (Eds.) (2004). Taxation: An interdisciplinary approach to research. OUP Oxford.

- Lazou, C., & Tsinakos, A. (2022, June). Computer-mediated communication for collaborative learning in distance education environments. In International conference on human-computer interaction (pp. 265–274). Springer International Publishing.

- Lee, E., & Hannafin, M. J. (2016). A design framework for enhancing engagement in student-centered learning: Own it, learn it, and share it. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(4), 707–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9422-5

- Leh, A. S. (2001). Computer-mediated communication and social presence in a distance learning environment. International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, 7(2), 109–128.

- Li, J., & Li, K. (2023). Multiple perspectives on the educational policies on studying in China During the epidemic era. Beijing International Review of Education, 4(4), 750–758. https://doi.org/10.1163/25902539-04040015

- Liu, F., Li, L., Zhang, Y., Ngo, Q. T., & Iqbal, W. (2021). Role of education in poverty reduction: Macroeconomic and social determinants form developing economies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(44), 63163–63177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15252-z

- Liu, H., Yao, M., Li, J., & Li, R. (2021). Multiple mediators in the relationship between perceived teacher autonomy support and student engagement in math and literacy learning. Educational Psychology, 41(2), 116–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1837346

- Logan, E., Augustyniak, R., & Rees, A. (2002). Distance education as different education: A student-centered investigation of distance learning experience. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 43(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/40323985

- López Gutiérrez, J. R., Ponce, P., & Molina, A. (2021). Real-time power electronics laboratory to strengthen distance learning engineering education on smart grids and microgrids. Future Internet, 13(9), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi13090237

- Mabutha, R. J. (2017). Tax ethics education within the chartered accountant curriculum in South Africa. Doctoral dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, School of Accountancy).

- Maheshwari, M., Gupta, A. K., & Goyal, S. (2021). Transformation in higher education through e-learning: A shifting paradigm. Pacific Business Review International, 13(8), 49–63.

- Malczyk, B. R. (2020). Introducing social work to HyFlex blended learning: A student-centered approach. In Online and distance social work education (pp. 161–175). Routledge.

- Maldonado, I., Silva, A. P., Magalhães, M., Pinho, C., Pereira, M. S., & Torre, L. (2023). Distance learning of financial accounting: Mature undergraduate students’ perceptions. Administrative Sciences, 13(4), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040103

- Maphalala, M. C., Khumalo, N. P., & Khumalo, N. P. (2021). Student teachers’ experiences of the emergency transition to online learning during the Covid-19 lockdown at a South African university. Perspectives in Education, 39(3), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v39.i3.4

- Mardini, G. H., & Mah’d, O. A. (2022). Distance learning as emergency remote teaching vs. traditional learning for accounting students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Accounting Education, 61, 100814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2022.100814

- Matorevhu, A. (2019). Student perceptions of blended assessment approach in The Bachelor of Education Degrees in mathematics and science through open distance and e–learning (Odel). International Journal of Trends in Mathematics Education Research, 2(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.33122/ijtmer.v2i1.109

- Melguizo, T., Sanchez, F., & Velasco, T. (2016). Credit for low-income students and access to and academic performance in higher education in Colombia: A regression discontinuity approach. World Development, 80, 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.018

- Mishra, L., Gupta, T., & Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012

- Mohammed, T. F., Nadile, E. M., Busch, C. A., Brister, D., Brownell, S. E., Claiborne, C. T., Edwards, B. A., Wolf, J. G., Lunt, C., Tran, M., Vargas, C., Walker, K. M., Warkina, T. D., Witt, M. L., Zheng, Y., & Cooper, K. M. (2021). Aspects of large-enrollment online college science courses that exacerbate and alleviate student anxiety. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 20(4), ar69. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.21-05-0132

- Mondal, P., Misra, S., & Misra, I. S. (2013). A low cost low bandwidth real-time virtual classroom system for distance learning [Paper presentation]. In: 2013 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference: South Asia Satellite (GHTC-SAS), August) (pp. 74–79). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/GHTC-SAS.2013.6629892

- Moos, R. H. (1980). Evaluating classroom learning environments. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 6(3), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-491X(80)90027-9

- Morgan, A., Freudenberg, B., Kayis-Kumar, A., Le, V., Whait, R., Cull, M., Castelyn, D., & Vitale, C. (2022). Pro bono tax clinics: Aiding Australia’s tax administration and developing students’ self-efficacy. Journal of Australian Taxation, 24, 76.

- Morgan, H. (2022). Alleviating the challenges with remote learning during a pandemic. Education Sciences, 12(2), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020109

- Moyo-Nyede, S., & Ndoma, S. (2020). Limited Internet access in Zimbabwe a major hurdle for remote learning during pandemic. Afrobarometer Dispatch. No. 371. 30.

- Mtebe, J. S., & Raisamo, R. (2014). Investigating perceived barriers to the use of open educational resources in higher education in Tanzania. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2), 43–66.

- Nadezhda, G. (2020). Zoom technology as an effective tool for distance learning in teaching English to medical students. Бюллетень науки и практики, 6(5), 457–460.