Abstract

To attract and retain international students, institutional support services at Asian universities must add value from the student’s perspective. This study aims to explore international students’ experiences at Indian higher education institutions and understand their thoughts on how the university’s International Student Office (ISO) could best support them. Data was collected from 11 students. Eight participated in individual in-depth interviews and three in a small focus group discussion (international: n = 10 and non-resident Indian: n = 1). A qualitative thematic analysis was employed to extract themes that describe international student experiences and the role of the institutional support services i.e., the ISO. Grounded in the consumer value concept, this study discusses four emergent themes. These are ISO support during the stressful initial transition phase, overcoming language-related issues, mitigating cultural differences and envisaging an ISO that is organised for usage. Findings indicate that the students’ perceived value of institutional support provision is a multidimensional construct comprising attributes that capture sought-after outcomes, experiences, and interactions. This study proposes a consumer-centric framework by which international student support services at the university may offer more effectiveness and value.

1. Introduction

International student mobility literature suggests that, in recent decades, international student flows have not been limited to the Western developed host countries (Glass & Cruz, Citation2023; Hou & Du, Citation2022; UNESCO, Citation2023). Some Asian countries have rapidly emerged as education hubs and now compete with the traditional higher education destination countries. In particular, traditional student-sending countries like China, Korea, and Malaysia now rank as prominent higher education destinations (Ahmad & Shah, Citation2018; Manning, Citation2020; Pawar, Citation2022). India, another significant source country of international students, strives to establish itself as a global education hub (De Wit & Altbach, Citation2021; MHRD GOI, n.d.; Pawar, Citation2024). In a scenario marked by escalating global competition to enrol international students, host countries and universities recognise the importance of institutional support services in attracting and retaining international students (Ammigan & Jones, Citation2018; Woodend & Arthur, Citation2022).

The Indian government aspires to transform its higher education (HE) sector from being a source market for international students to becoming a favoured destination for overseas students. For example, the new National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) of the Indian government envisions India as a global education hub. The Indian government’s ‘Study in India’ program targets a four-fold increase in the enrolment of international students. Further, the policy framework also foresees an International Student Office (ISO) at each of the Indian HEIs that have a presence of international students. The ISO would manage all matters concerning supporting and welcoming overseas students (MHRD GOI, n.d.). Aligned with the NEP 2020 vision and common goal described by Perez-Encinas and Ammigan (Citation2016), this study views an ISO in the present Indian HE setting as an establishment that aims to support the development of international students. Previous research has documented the significance of such an institutional support provision in providing international students with a positive and successful experience during their stay on the host campus (Briggs & Ammigan, Citation2017; Chen et al., Citation2002). HEIs need to start by understanding the consumers’ view on institutional support attributes that enhance the experiences of international students. This study aims to explore international students’ experiences at Indian higher education institutions and understand their thoughts on how the university’s International Student Office could best support them.

This study contributes to the existing literature by responding to a shortfall in research-based knowledge on institutional support services for international students. This research was necessitated for three fundamental reasons. First, although empirical research on international student support provision is growing, it still needs to be expanded, given that international students are a distinct and economically significant consumer segment. In an expanding global industry that is regularly subject to consumerist demands, it is prudent to understand consumer needs when framing an international student service provision at the university. Second, much of the research on the needs and experiences of international students is set in developed English-speaking host countries such as the USA or the UK. Aspiring Asian HE destination countries offer a host country context where the first language of the Teachers is not English (Singh & Jack, Citation2021). Third, particularly in the case of India, the NEP 2020 of the Indian government brings in fresh policy reform plans that cater to the move towards internationalisation of Indian HE. This is thus an opportune time to study international student support services at Indian universities to offer valuable market intelligence that supports informed HE policymaking.

The first aim of this study was to investigate the thoughts of international students on how the student support office at Indian universities could offer support services to help them overcome challenges. Thus, the research question:

RQ1: What initiatives of international student support services add value from the student’s perspective?

The second aim is to develop a consumer value perspective framework constituting key support service attributes of an ISO to support international students. Hence, the research question:

RQ2: What are the consumer-centric components in framing effective and valuable international student support services?

The rest of the article is organised as follows. Section two briefly overviews the relevant background on the inbound mobility of international students in Indian HE, the consumer value concept, the relevance of consumer value in the HE industry context, the need for an international student-led support service provision and the experiences of international students in Asian destination country settings. Section three details the research methodology. Section four presents the key findings of this study. Subsequently, Section five discusses the results of this study and their implications. In section six, the conclusions and limitations of this research are presented.

2. Background

2.1. International student mobility in Indian higher education

The inbound mobility of international students into Indian HEIs has received increasing attention from the Indian government. Of the approximate 48,000 international students presently enrolled in Indian HE, a large proportion comes from Nepal (about 28%) and a noticeable proportion from Afghanistan (about 8%) (UNESCO, Citation2023). Outside the Indian sub-continent, the African region has traditionally been a critical source of international students for Indian HE. However, the number of incoming students from some African countries has fallen sharply in recent decades (Pawar, Citation2024). Lavakare and Powar (Citation2013) expressed concern about the fall in the number of students from Africa, especially considering India’s popularity as a study-abroad destination for African students in the 1990s. They mention unfriendly administrative procedures and problems in adjustment to the Indian culture, among several other critical reasons for the decline in the inbound mobility of students from Africa.

2.2. The consumer value concept

The term consumer value has two primary connotations: value for the consumer and value for the business establishment. This research focuses on the former - value of an ISO for international students. Herein, consumer value focuses on the consumer’s product evaluation (Holbrook, Citation1999). The organisation’s ability to deliver value to the consumer is a significant source of achieving and retaining competitive advantage (Woodruff, Citation1997). The idea of consumer value being a multidimensional construct focuses on the involvement of varied values in experiences when consuming products; it includes a product’s cognitive, emotional and social aspects (Zeithaml et al., Citation2020).

Scholars have explained perceived consumer value as what the customers gain (the benefit) from purchasing and using a product against what customers expend (the cost) (Kumar & Reinartz, Citation2016; Zeithaml, Citation1988; Zeithaml et al., Citation2020). The frequently cited value types that benefit the consumer using the product include functional/utilitarian, hedonic/emotional and self-expressive/social value types (Sheth et al.,Citation1991; Woodall et al., Citation2014). Functional value signifies the perceived ability of the product to perform the said function. In this way, the consumer reaches the desired goal. Hedonic value characterises the offering of positive emotional states. The symbolic value for the consumer represents self-expression. Psychological and monetary costs signify the other part of the consumer value explanation: the sacrifices incurred by the consumer. Desired consumer value reflects the expected value, referring to the needs and goals of the customer (Komppula, Citation2005). Furthermore, desired consumer value can include many dimensions; each is meant to aid the customer in attaining explicit goals in particular situations, each with its relative status (Flint et al., Citation1997).

2.3. Consumer value in the HE industry

Students increasingly show consumer-like behaviour and demand more value from the HE provider (Tomlinson, Citation2018; Woodall et al., Citation2014). Thus, for universities, understanding the processes involved in knowing, creating and delivering suitable value to the student is crucial. Previous studies examining the consumer value concept in the HE context have classified the HEI value attributes into value types. For example, Dziewanowska (Citation2017) classifies 40 factors of importance identified through a survey into seven value types expected by students from their university. Dziewanowska (Citation2017) states that even though students highly appreciate utilitarian value, the desire for intrinsic and epistemic value is also notable. In a student housing context, investigating students’ sense of shared responsibility on their perception of value, Cao et al. (Citation2019) found that the value was more hedonic than functionality-driven. Associating value themes to the ‘push-pull’ factors that determine international student flows (Mazzarol & Soutar, Citation2002), Hattersley and Nicholson (Citation2024) find that functional (employment-related outcomes) as well as hedonic (freedom) value types drive the choice of UK HE for Chinese students. Affirming learning to be a core service of the HEI, Ng and Forbes (Citation2009) state that the learning experience is a co-creation that contains a hedonic dimension.

Woodall et al. (Citation2014) identify benefits and sacrifices significant to home, and international students’ value perspectives in a generic university experience context. A balance of ‘outcomes’ (e.g. practical, social) and ‘acquisition and relationship costs’ (e.g. starting a family) was found to be more relevant for international students than home students, where it was a price versus features interchange (Woodall et al., Citation2014). Highlighting the implications of consumer value in HE settings, Ledden et al. (Citation2011) find evidence of service quality being linked to value perception that drives satisfaction and word-of-mouth (recommendations).

2.4. The imperative for support services that international students deem valuable

Studies suggest that international students encounter diverse challenges, such as cultural differences, academic difficulties, and lack of social support (Sherry et al., Citation2010). These difficulties occur irrespective of the host country where international students study and in contexts inside and outside the classroom (Lee & Rice, Citation2007). Given the diverse challenges that international students face, the accountability lies with host universities to offer suitable support and resource schemes to help students achieve their goals (Akanwa, Citation2015; Briggs & Ammigan, Citation2017). Moreover, in a highly marketised global HE environment, support provisions at HEI campuses must address international student visa compliance and prioritise student experiences (Lee & Rice, Citation2007). A student support provision driven by student needs and expectations rather than what the university can provide is central to helping international students to better their experiences.

2.4.1. International student success challenges in Asian host country contexts

Extant Asian host country-focused studies suggest that international students in emerging Asian HE destinations such as China, UAE, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia experience unique challenges. If these difficulties persist, they may impede international student enrolment plans in these Asian education hubs. Ding (Citation2016) underscores the need for inclusive policies that China needs to embrace to enhance its competitiveness as a global destination for international students.

Outside the academic sphere, international students grapple with adapting to new cultural environments and often experience social isolation. These challenges can become more pronounced when social relationships with students in the host country are not strong (Yusoff, Citation2012). One area that consistently falls short of global standards is the support services provided to international students upon arrival and during their initial days at the host higher education institutions (HEI) (Ding, Citation2016). Also, assumptions of HEIs on what international students need to overcome challenges seem to impact institutional support provision to students (Cruz et al., Citation2022). In academic settings, language barriers have been found to cause significant challenges to international students in multiple Asian destinations on two fronts: English and the local host country languages (Singh & Jack, Citation2021; Wen et al., Citation2018). Teachers using the host country language (e.g. Malay) instead of English as a medium of instruction in classrooms cause significant difficulties in understanding what is being said during the lectures (Singh & Jack, Citation2021; Snodin, Citation2019; Wen et al., Citation2018). Next, unequal English language proficiency among international and domestic students hampers group learning activities and discussions (Qiqieh & Regan, Citation2023; Rhein & Jones, Citation2020). Furthermore, students perceive faculty-international student interactions as inadequate, and the quality of education imparted is less than that of global benchmarks (Ding, Citation2016; Wen et al., Citation2018).

3. Methodology

Given the purpose of this study and its exploratory nature, we follow a qualitative approach to sampling, data collection, and analysis. Previously, researchers have successfully used a qualitative approach to knowing international students’ perceptions in varied host country contexts (Calikoglu, Citation2018; Pawar et al., Citation2020).

3.1. Study sample

The participants in this study were international students enrolled at multiple HEIs in western India. A combination of purposive and convenience sampling was used for recruitment. The initial approaches to recruiting international students for the interview began with convenience sampling of students in contact with the ISO - in charge and ‘available’ to be interviewed. This was followed by snowballing efforts to identify prospective respondents from different countries to allow a diverse sample set. Qualitative data were collected from eleven participants. Seven international students from five countries and one non-resident Indian (NRI) student participated in the interviews. The NRI student was an ‘international cell’ head in his third year of the undergraduate program and was considered a suitable respondent. Additionally, three international students participated in a focus group discussion (). The students were enrolled in varied undergraduate as well as postgraduate programs. Four students were from African countries, while three were from Asian countries. The participants were between 20 and 24 years old. The interviews and group discussions were conducted in English from July 2022 to November 2022.

Table 1. The participant profile (n = 11).

3.2. Interview and focus group format

Data was gathered through individual interviews and a small focus group discussion. This combination aided the interpretation of the phenomenon and enhanced the richness of information (Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2008). Herein, even though interviews are considered the benchmark in eliciting qualitative data, focus groups enabled the exploration of the respondents’ experiences in an interactive setup (Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2008). The interviews and the focus group were semi-structured, as the purpose of the meeting was to know the students’ perspectives regarding their experience of the phenomenon under study (McIntosh & Morse, Citation2015). The semi-structured interview type was used because some specific topics were to be covered, and at the same time, the stories of the students were to be heard (Rabionet, Citation2011). A verbal concurrence from the participant was obtained. The interviews consisted of open-ended questions about the experiences and expectations of international students from their student support provision. One researcher conducted the in-depth interviews and the focus group discussion in the presence of the second researcher. First, the researcher explained the context of the research project, the purpose, the methodology, and the respondent set for this research (Chenail, Citation1997). The main questions were open-ended. Example: ‘How can the international student office support international students?’ We also enquired about the students’ initial transition and social and academic life. The subsequent ones were comparatively more specific. Example: ‘What support is needed when the student first arrives in the host country?’ Follow-up questions and prompts were used to encourage the participants to develop ideas. The elicitation of participant data continued until information gathering reached a point of diminishing returns. Generalisability was not the aim; the priority was sample adequacy (the data saturation point) rather than the sample size (Bowen, Citation2008).

3.3. Data analysis

All online interviews were audio and video recorded; the in-person interviews and the focus group discussion were audio recorded; all recordings were written out and studied. To safeguard the privacy of the information elicited from the respondents, the discussions were transcribed in a private setting. Furthermore, the interview recordings were available only to the researchers. Thematic analysis, explained as ‘a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 79), was used to code the data. An inductive approach was followed to analyse, code, and generate a thematic map. The analysis ran alongside the conduct of the interviews. It started with the two researchers’ independent readings of the transcribed text. Reading and listening to the interview audio recordings multiple times helped identify meaningful qualitative units (Chenail, Citation2012). Though the transcripts were read and listened to line by line, the focus remained on recognising meaningful entire units (Chenail, Citation2012). The researchers identified the relevant sections guided by the research questions, and similar sub-codes were grouped. Perspectives across the relevant data were used to create classifications. The similarity of meaning is then linked to results. The researchers marked quotes to exemplify each theme. A manual examination was preferred over using software for two main reasons. One, the elicited data was not too large, and two, the researcher was familiar with the topic.

4. Findings

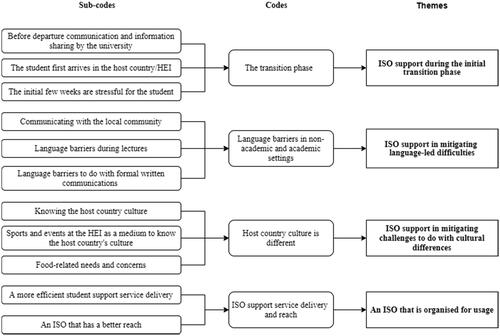

Four themes emerged: ISO support during the students’ initial transition phase, ISO support in mitigating language-led difficulties, ISO support in mitigating challenges concerning cultural differences and an ISO organised for usage. offers a view of the Sub-code-Code-Theme linkages. The Themes are issues that international students face and the role of the ISO in supporting students.

4.1. ISO support during the initial transition phase

Overall, this study finds that the ISO has a crucial role in improving student experiences during the initial days in the host country. Reflecting on the early interactions, P8 expressed: ‘My first point of contact was the international student office in the college.’ P8 also reported, ‘Active steps taken by the ISO can help them offer a warm welcome in the starting weeks.’ P4 appreciated the pre-departure orientation programs with the Indian Embassy and the university. She expressed a sense of readiness that this pre-embarkment engagement provided to her:

They guided me on what I should do when I was already in India, which helped me to come to India with determination and a set goal. Because I already knew not everything but (at least) a bit of what I should do when I was in India.

This kind of communication is a preparation before you start your new journey, so that helps because you feel safe knowing that there are people there who will support you, guide you, and help you; the first days are very crucial.

It was revealed that the initial weeks at the HEI were stressful. P3 recollected high anxiety during the first few weeks in India at the host HEI to express that ‘the first month was very hard.’ He also pointed out that the more days at the host HEI, the calmer he felt: ‘The more the months, the more the days start to get comfortable.’ Adding on, this student expressed that developing social contacts during this initial phase is a way to deal with the distress and to feel more ‘at home’ in the study abroad location:

You start meeting with lots of people, getting conversant, making connections, making relationships with people, feeling at home, and getting comfortable. (P3)

The content of the document presented by the international student is difficult […] show them how it is done and what to do because when you come here, the person comes here without knowing what is to be done. (P1)

4.2. ISO support in mitigating language led difficulties

4.2.1. Language barriers in non-academic settings

Chances are that people do not understand English outside the campus and in social settings and speak only the regional or the national language. This study finds that in social settings, not having a common language to communicate is a vital issue that international students face. For example, a student noted:

Not everyone can speak English, and not everyone can speak the official language of my country, nor can I speak the official language of every State or City (of the host country). That is the first support that the international student office should give to students and understand that they (the international students) do not understand the language. (P4)

4.2.2. Language barriers in academic settings

Participants expressed that Teachers used the local Indian language (Marathi) during their lectures, which caused much difficulty in understanding what was being said. P3 emphasised the need for Teachers to speak in English ‘throughout their lectures’. It was also voiced that language-related teaching-learning issues have continued over the years. In this context, the possibility of teachers not realising the presence of international students in the classroom was also expressed. P7 referred to the experiences of some of the international student friends to state, ‘What happens in those (some) colleges (is that) they teach only in the local language […] friends who have just come, it is so difficult for them’. Being the only student amongst 25 other students who talk in the local language made P5 doubt the learning outcome she derived from being there. It was expressed that the ISO should play a role in addressing this issue.

Furthermore, understanding the official circulars (formal written notifications) of the HEI was a challenge for the students as the language used in them was the official language of the particular Indian State and not English. It was expressed that translating these circulars through friends was challenging to practice. P2 voiced, ‘Sometimes you miss exam dates; you may miss an important announcement.’ The participant suggested that the international student support office may translate these circulars into English and make them available to international students.

4.3. ISO support in mitigating challenges to do with cultural differences

Participants highlighted the need for the host country actors to understand the wide-ranging cultural differences that international students have to accommodate:

The second support is to understand that we are not used to the culture, we are not used to the type of food, we belong to a different environment, and this is new to us; they should guide us on what is good and not good for us to follow to be able to adjust ourselves in the new environment that we are facing (P4).

4.3.1. Knowing the host and showcasing your own culture

Findings show that international students face continued difficulties adapting to cultural differences in the new surroundings. Interactions with the participants revealed several initiatives for the ISO, ranging from organising culture-related programs and sports events to actions that may help overcome food-related concerns. Speaking of university-organized events as a way to know the host country’s culture, P4 expressed: ‘We are curious to know how Indian people do their events and how they behave, so that also gives us the connection.’ Furthermore, there was a desire to showcase the international students’ culture. This student explained her recommendation:

Let us say today is the Independence Day in my country, and the university itself creates something that is a celebration of the Independence Day of my country that gives me that belonging and that connection. It is not only for me; everyone else also gets to know my culture and experience different cultures. (P4)

4.3.2. Participation in team sports

Through sports, foreign students must be provided opportunities for cultural expression and adaptation to multicultural environments; otherwise, sports could become a vehicle for exclusion (Allen et al., Citation2010). When asked about the expected initiatives to help overcome culture-related issues, P4 said:

First, I think of sports because sports help people to become one, to be together because in sports they achieve, the aim of each team is to win, so sports make you communicate with each other. I think that is one of the events that can get people from different nationalities together.

I am a basketball player, a two-time national player, but here I could not join the university team because no one from international affairs introduced me to the sports department for the university sports activities.

4.3.3. Food-related issues

Participants expressed that their food habits are very different from the food that is on offer at the campus. To mitigate this issue, having international students on the food menu committee was recommended as a strategy: ‘At least two students in the mess committees can be from an international background’ (P6). Another student suggested: ‘Provide a kitchen in the student hostel for the students to prepare the food they want to have’ (P9).

4.4. An ISO that is organised for usage

4.4.1. Expected competencies of an ISO employee

Participants used the following terms to express their expectations of the human relations skills of ISO staff: friendly, understanding, patient, a good listener, and trustworthy. The personal qualities that an ISO staff should possess, as per the findings of this study, include having the requisite knowledge, being able to devote adequate time, and having an extroverted personality. The following statements are examples of participants’ opinions on the desired competencies of an ISO employee. ‘First of all, there should be someone always there or has the time available for us to guide us … someone that can communicate fluently and is an extroverted person in a way’ (P4). Another student stated: ‘The person needs to be friendly enough and accommodating; if not, it can be very hard for international students’ (P3). Another participant expressed the ISO staff knowing multiple Indian languages as a valuable competency, particularly in interacting with students that come from the neighbouring countries: ‘… if he (the ISO staff) knows ‘Bengali’ he will take care of the Bangladeshi students if […] if he knows English that is primary. Still, if he knows one or two other languages, the basics, just the words, it will be of great importance’ (P7).

4.4.2. An ISO that with a better reach

Accessing the ISO service by visiting the office frequently was expressed as a concern. A participant who was earlier a part of the international student cell suggested that a more spread-out ISO network with a role for the more experienced international students could add value:

I believe there is a field therapist who helps students, specifically international students, to settle into the country. You have campus leaders, the 4th year and the 3rd year students (the more experienced international students) as well, so a proper structural view rather than a single office (is recommended). Also, the office is a bit intimidating for people to keep on going to. So, having their peers be a part of this community is much more approachable for the students to reach out to. (P8).

Next, typically, HEIs are geographically away from the ISO headquarters at the main university campus, where the visa registration-related processes and enrolment formalities are conducted. In the focus group discussion, participants (P9 and P11) highlighted the need for the respective HEI with an enrolment of international students to have an ISO set-up that can independently deal with all such formal procedures (e.g. visa extension procedures). Difficulties commuting to the ISO from the main campus from the HEI where the student is enrolled were expressed as infrastructure was not convenient.

Counsellors to international students were found to ‘play a great role’ in helping students overcome challenging situations. P6 shared the positive experiences of having an in-house faculty as an ISO-affiliated counsellor at her HEI.

Every week, she (the teacher in the role of an international cell counsellor) used to give us an email that if you have any problem, come and talk to us, and even if we did not have a problem, have a cup of tea and talk so that builds a friendly relationship between the faculty and the student, so people used to feel comfortable to go and share with her the problems, so yes counselling in this matter really helped the international students. (P6)

The above statement signifies the value of the ISO-linked counsellor to international students, the reach (availability at the HEI location), regularity of counselling sessions and an informal approach to setting up the meetings. Faculty as counsellors/ISO representatives at universities were recommended rather than regular ISO staff because they could address academics-related issues. Another appreciated practice was allocating a counsellor for students from a particular geographical region (e.g. South Asia).

5. Discussion

The analysis reveals four main themes (). Theme 1 encompasses the pre-departure period and the purposefully vital initial few weeks at the study destination. This study reveals the need for a comprehensive information-sharing scheme by the host ISO before the student leaves for the host country (Bashir & Khalid, Citation2022). Similar to results obtained in other research (Barker et al., Citation1991), the initial few weeks after students first arrived were revealed to be stressful. Respondents highlight that all students must be received at the airport and feel welcome when arriving in the host country/HEI. In the initial, ensuring the well-being of the student and practices that promote social interactions are necessary, and the ISO potentially has a substantial role to play during this phase. The other aspect of particular importance in this initial Theme is the need for institutional guidance during the visa registration process.

Theme 2 and Theme 3 are the language and culture-oriented issues that international students in India encounter. The unique language barriers for international students that this study identifies face are in social as well as academic settings. Complex multilingual environments are typical of Asian countries due to the high cultural and lingual diversity. English may not be understood by people in social settings, making it difficult for students to communicate with the local community. The language issue is also a significant hindrance to achieving academic goals. In some HEIs, Teachers use Indian languages in classrooms, making it difficult for overseas students to comprehend. Furthermore, formal written communication also at some HEIs tends to be in the regional language. These revelations are similar to the research findings in other Asian HE settings, such as Malaysia and Chinese HE (Hussain et al., Citation2022; Citation2023; Singh & Jack, Citation2021). For example, in Malaysia, international students mention teachers’ non-regular use of English in the classroom and the posting of circulars on notice boards in Bahasa Melayu (Singh & Jack, Citation2021). Findings also reveal the difficulties students encounter in adjusting to different cultural environments in India. The need for adjustment includes understanding human behaviour and the food choices available to international students.

Finally, Theme 4 is what students perceive would make the ISO service more organised for usage. This is expressed by two aspects: the competencies of the ISO staff that would make the ISO more able to deliver value to students and, the ISO as a support provision being more accessible to international students. First, the skills and knowledge of the ISO staff are essential in providing effective service (Ziguras & Harwood, Citation2011). Burkard et al. (Citation2005) find two important competency areas for entry-level student affairs staff: personal qualities and human relations skills. Respondents revealed the need for the ISO staff to be knowledgeable about students’ processes and documentation needs, approachable, patient, and good with language skills. Next, regarding accessibility, the respective in-house faculty at the HEI are ISO-linked councillors, and a network of experienced ISO-linked international students is the initial point of contact.

5.1. ISO student support attributes and value types

Subject to increasing consumeristic pressures and global competition, delivering value to international students is more vital than before. Herein, the value offered by the ISO to the student is viewed as a multidimensional idea. This is because consumption practices may concurrently entail more than one value feature, including utilitarian, hedonic, symbolic, relational and aesthetic features in consumption (Zeithaml et al., Citation2020).

represents the essential attributes of the Indian ISO's student support services and the corresponding value types. Based on the themes and sub-themes identified by this study, the Table offers a basis for the university student support service provision to specify value-creation strategies. The classification of support initiatives shows that these support service attributes are of functional, hedonic, symbolic and relational value types. The analysis indicates that the role of the ISO as a student support service extends beyond the practical features and that students are likely to see value through emotions and associations as well.

Table 2. Student support components and the value type.

5.1.1. Implications for practice and policy

Impactful HEI-level support for international students is essential for Indian HE to achieve the NEP 2020 goal of a more prominent presence of international students at Indian campuses. This study’s central idea is that most international students support initiatives, if not all, that should add value from the student’s perspective (Di Maria, Citation2020). Participants of this study described their experiences and indicated a role for the ISO to help them overcome challenges. The delivery of student support service attributes such as those recognised in this research () act as a market intelligence input for Indian HE policymakers and HEIs to enrol and retain international students. This study reports support service attributes for multiple phases of the international student experience.

6. Conclusion

This research contributes to the literature by examining the needs of international students in an emerging Asian HE destination (India), a host country setting that is far less researched. The challenges international students face in Indian HE are similar to those in other developing Asian host countries (e.g. China and Malaysia). These challenges include social challenges, teacher-led communications with students, and language barriers in academic and non-academic settings wherein English is not only the international student’s second language but also that of the host communities. The participants in this study were largely successful in recommending ways in which the ISO could play a more impactful role in supporting students to overcome distress and difficulties. This study adds to the present knowledge of international student support services by offering a perspective that has consumers at its core. This study advocates a support provision driven by what the international students’ desire rather than only what the university thinks is required. Not all challenges students encounter may have to do with student adjustment; some are because of the shortfalls of the host HE system. Examples of such shortfalls have been noted in other HE destinations, such as accommodating foreign students, complex visa registration procedures, and inconsistent use of the English language by teachers during lectures (Lee & Rice, Citation2007; Singh & Jack, Citation2021). Finally, this study indicates that the sought-after value of institutional support services is multi-dimensional. This means that international students’ support needs are not only derived from sought-after outcomes and correct product attributes (functional value) but also from emotions (hedonic value) and interactions (relational value).

The qualitative nature of this study and having only eleven participants may have minimised the generalisability of the findings. However, we focused on an in-depth search, so the sample size was thought sufficient for this study. Another possible limitation was that the respondents of this study came from different geographies (countries of origin) and diverse cultural backgrounds. Upcoming research with a more generalisable sample size and a relatively focused scope may better explain the complexity of individual constructs. For instance, future research may dwell on African or Asian students’ initial transition phase experiences in a non-English speaking developed host country.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sanjay Krishnapratap Pawar

Sanjay Krishnapratap Pawar is an Associate Professor at the Symbiosis Institute of Management Studies, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, India. Before entering employment in higher education, Sanjay worked in the Indian industry as a marketing professional for several years. His research focuses on international higher education from consumer behaviour and marketing strategy perspectives. Sanjay’s research has been published by highly ranked academic journals, including those ranked by the ABDC Journal Quality List. He has received funding from several Indian organisations to pursue international student-focused research projects. Sanjay brings deep knowledge in providing market intelligence and strategic insights for universities and higher education systems to attain competitive differentiation.

Hirak Dasgupta

Hirak Dasgupta is an Associate Professor at the Symbiosis Institute of Management Studies, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, India. Hirak has a PhD in Business Management and nearly two decades of academic experience. His research papers have been published in reputed peer-reviewed journals.

References

- Ahmad, A. B., & Shah, M. (2018). International students’ choice to study in China: An exploratory study. Tertiary Education and Management, 24, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2018.1458247

- Akanwa, E. E. (2015). International students in western developed countries: History, challenges, and prospects. Journal of International Students, 5(3), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v5i3.421

- Allen, J. T., Drane, D. D., Byon, K. K., & Mohn, R. S. (2010). Sport as a vehicle for socialization and maintenance of cultural identity: International students attending American universities. Sport Management Review, 13(4), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.01.004

- Ammigan, R., & Jones, E. (2018). Improving the student experience: Learning from a comparative study of international student satisfaction. Journal of Studies in International Education, 22(4), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318773137

- Barker, M., Child, C., Gallois, C., Jones, E., & Callan, V. J. (1991). Difficulties of overseas students in social and academic situations. Australian Journal of Psychology, 43(2), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539108259104

- Bashir, A., & Khalid, R. (2022). Determinants of psychological adjustment of Pakistani international students. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2113214. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2113214

- Bowen, G. A. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794107085301

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Briggs, P., & Ammigan, R. (2017). A collaborative programming and outreach model for international student support offices. Journal of International Students, 7(4), 1080–1095. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v7i4.193

- Burkard, A. W., Cole, D. C., Ott, M., & Stoflet, T. (2005). Entry-level competencies of new student affairs professionals: A Delphi study. NASPA Journal, 42(3), 283–309. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1509

- Calikoglu, A. (2018). International student experiences in non-native-English-speaking countries: Postgraduate motivations and realities from Finland. Research in Comparative and International Education, 13(3), 439–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499918791362

- Cao, J. T., Foster, J., Yaoyuneyong, G., & Krey, N. (2019). Hedonic and utilitarian value: The role of shared responsibility in higher education services. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 29(1), 134–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2019.1605439

- Chen, H. J., Mallinckrodt, B., & Mobley, M. (2002). Attachment patterns of East Asian international students and sources of perceived social support as moderators of the impact of US racism and cultural distress. Asian Journal of Counselling, 9(1–2), 27–48.

- Chenail, R. J. (1997). Interviewing exercises: Lessons from family therapy. The Qualitative Report, 3(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/1997.2025

- Chenail, R. J. (2012). Conducting qualitative data analysis: Reading line-by-line, but analyzing by meaningful qualitative units. Qualitative Report, 17(1), 266–269.

- Cruz, N. I., Sy, J. W., Shukla, C., & Tysor, A. (2022). Ready, willing, and able? Exploring the relationships and experiences of international students at a federal university in the United Arab Emirates. STAR Scholar Books.

- De Wit, H., & Altbach, P. G. (2021). Internationalization in higher education: Global trends and recommendations for its future. In Higher education in the next decade (pp. 303–325). Brill.

- Di Maria, D. (2020). A basic formula for effective international student services. Journal of International Students, 10(3), xxv–xxviii. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v10i3.2000

- Ding, X. (2016). Exploring the experiences of international students in China. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316647164

- Dziewanowska, K. (2017). Value types in higher education–students’ perspective. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(3), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2017.1299981

- Flint, D. J., Woodruff, R. B., & Gardial, S. F. (1997). Customer value change in industrial marketing relationships: A call for new strategies and research. Industrial Marketing Management, 26(2), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(96)00112-5

- Glass, C. R., & Cruz, N. I. (2023). Moving towards multipolarity: Shifts in the core-periphery structure of international student mobility and world rankings (2000–2019). Higher Education, 85(2), 415–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00841-9

- Hattersley, D. J., & Nicholson, J. (2024). Unpacking the value sought by Chinese international students in UK higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2306347

- Holbrook, M. B. (Ed.). (1999). Consumer value: A framework for analysis and research. Psychology Press.

- Hou, C., & Du, D. (2022). The changing patterns of international student mobility: A network perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(1), 248–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1797476

- Hussain, W. A., Shao, Y., Liu, B., Abbas, H., Sallieu Jalloh, I., Akhtar Jamsheed, R., & Javed, M. (2023). Exploring the international postgraduates’ perspective of academic problems in Chinese universities located in Wuhan, China. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2168937. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2168937

- Hussain, W. A., Zhang, Z., Ilyas, M., Akram, S., & Ali, M. R. (2022). An empirical investigation on the cultivation and management of international postgraduates at five universities located in Wuhan, China. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2064582. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2064582

- Komppula, R. (2005). Pursuing customer value in tourism–a rural tourism case-study. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism, 3(2), 83–104.

- Kumar, V., & Reinartz, W. (2016). Creating enduring customer value. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 36–68. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0414

- Lambert, S. D., & Loiselle, C. G. (2008). Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(2), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x

- Lavakare, P. J., & Powar, K. B. (2013). African students in India: Why is their interest declining? Insight on Africa, 5(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975087813512051

- Ledden, L., Kalafatis, S. P., & Mathioudakis, A. (2011). The idiosyncratic behaviour of service quality, value, satisfaction, and intention to recommend in higher education: An empirical examination. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(11-12), 1232–1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2011.611117

- Lee, J. J., & Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International student perceptions of discrimination. Higher Education, 53(3), 381–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-005-4508-3

- Manning, K. D. (2020). Motivational factors among international postgraduate students in Hong Kong and Taiwan. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 22(1), 82–100.

- Mazzarol, T., & Soutar, G. N. (2002). ‘Push‐pull’ factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540210418403

- McIntosh, M. J., & Morse, J. M. (2015). Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 2333393615597674. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615597674

- Ministry of Human Resource Development, GOI. (n.d). New Education Policy 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0. pdf.p39.

- Ng, I. C., & Forbes, J. (2009). Education as service: The understanding of university experience through the service logic. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 19(1), 38–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841240902904703

- Oliver, R. L. (2002). Value as excellence in the consumption experience. In Consumer value (pp. 59–78). Routledge.

- Pawar, S. K. (2022). An assessment of market dependency risk in the international student industry. International Journal of Educational Reform, 105678792211067. https://doi.org/10.1177/10567879221106727

- Pawar, S. K. (2024). India’s global education hub ambitions: Recent student mobility trends, the underlying dynamics and strategy perspectives. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2289310. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2289310

- Pawar, S. K., Vispute, S., & Wasswa, H. (2020). Perceptions of international students in Indian higher education campuses. The Qualitative Report, 25(9), 3240–3254. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4453

- Perez-Encinas, A., & Ammigan, R. (2016). Support services at Spanish and US institutions: A driver for international student satisfaction. Journal of International Students, 6(4), 984–998. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v6i4.330

- Qiqieh, S., & Regan, J. A. (2023). Exploring the first-year experiences of international students in a multicultural institution in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of International Students, 14(1), 323–341. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v14i1.4967

- Rabionet, S. E. (2011). How I learned to design and conduct semi-structured interviews: An ongoing and continuous journey. Qualitative Report, 16(2), 563–566.

- Rhein, D., & Jones, W. (2020). The impact of ethnicity on the sociocultural adjustment of international students in Thai higher education. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 19(3), 363–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-020-09263-9

- Sherry, M., Thomas, P., & Chui, W. H. (2010). International students: A vulnerable student population. Higher Education, 60(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9284-z

- Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(91)90050-8

- Singh, J. K. N., & Jack, G. (2021). The role of language and culture in postgraduate international students’ academic adjustment and academic success: Qualitative insights from Malaysia. Journal of International Students, 12(2) https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v12i2.2351

- Snodin, N. (2019). Mobility experiences of international students in Thai higher education. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(7), 1653–1669. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2018-0206

- Tomlinson, M. (2018). Conceptions of the value of higher education in a measured market. Higher Education, 75(4), 711–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0165-6

- UNESCO. (2023). Number and rates of internationally mobile students (inbound and outbound). Retrieved from http://data.uis.unesco.org/

- Wen, W., Hu, D., & Hao, J. (2018). International students’ experiences in China: Does the planned reverse mobility work? International Journal of Educational Development, 61, 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.03.004

- Woodall, T., Hiller, A., & Resnick, S. (2014). Making sense of higher education: Students as consumers and the value of the university experience. Studies in Higher Education, 39(1), 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.648373

- Woodend, J., & Arthur, N. (2022). Qualitative research with former international students: Reflections on conceptualization, planning and relational engagement. The Qualitative Report, 28(5), 1268–1281. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2023.6067

- Woodruff, R. B. (1997). Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02894350

- Yusoff, Y. M. (2012). Self-efficacy, perceived social support, and psychological adjustment in international undergraduate students in a public higher education institution in Malaysia. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(4), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311408914

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

- Zeithaml, V. A., Verleye, K., Hatak, I., Koller, M., & Zauner, A. (2020). Three decades of customer value research: Paradigmatic roots and future research avenues. Journal of Service Research, 23(4), 409–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520948134

- Ziguras, C., & Harwood, A. (2011). Principles of good practice for enhancing international student experience outside the classroom.