Abstract

Amid an influx of unemployed graduates who are offloaded by tertiary institutions annually, this study sought to promote job creation through entrepreneurial practices. The study criticises the notion that only tertiary education is enough for economic prosperity for both male and female tertiary students. A framework of the determinants of entrepreneurial mindset development was examined in which four determinants were analysed, namely entrepreneurial education, culture, individual and facilitating conditions. The moderating effect of gender on entrepreneurial mindset development was also tested whilst the direct link between entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship was analysed. Data were collected from 378 students from universities in Zimbabwe using a structured questionnaire. A causal research design was applied in testing the interlinks. Data for the study were analysed using the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) technique whilst the moderating effect of gender was analysed using the Hayes Process Macro procedure. The study validated that employment creation is attainable through entrepreneurship, which is driven by an entrepreneurial mindset. However, only entrepreneurial education, culture and individual determinants recorded significant effects on the entrepreneurial mindset. Consequently, the study found that gender stereotype is still rife within the entrepreneurship arena and cultural determinants and gender roles influence females’ uptake of entrepreneurial roles. Thus, a cultural, psychological and education shift was recommended towards employment creation.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

The sad reality among most tertiary institutions in Africa is that graduates spend many years studying various professions, yet the job market fails to absorb them all. Approximately nine million tertiary students are enrolled each year, yet an average of 27% have realistic employment opportunities (The World Bank Group, Citation2020). In South Africa, only 30% of the 250,000 fresh graduates released yearly find employment (Goyayi, Citation2022). Similarly, Zimbabwean universities churn out more than 5000 graduates every year, with thousands more coming from polytechnic colleges, teachers’ colleges and other institutions of higher learning. However, the unemployment rate in the formal sector is estimated to be over 90% in Zimbabwe (Zimstat, Citation2022). This brings about frustration as graduates fail to sustain their livelihoods as anticipated.

Regarding that problem, Dungey and Ansell (Citation2022) note that students were groomed to believe that formal education is the key to success. However, Makandwa et al. (Citation2023a) found that the antidote to the woes that most African graduates face with unemployment is employment creation, not employment seeking. This drives the need for students to focus not only on getting a tertiary qualification but also on developing an entrepreneurial mindset which drives venture creation. Calls to develop graduate mindsets towards entrepreneurship are worthwhile, considering that a solution to deal with threats from restless youths in society is required, and entrepreneurship is lauded for its capabilities to act as an effective remedy to the challenges of unemployment (Dungey & Ansell, Citation2022). Moreover, Makwara et al. (Citation2022) claim youth resistance and disinterest towards entrepreneurship due to a lack of entrepreneurship mindset.

Mawonedzo et al. (Citation2021) similarly claim that despite the perceived importance of entrepreneurship to livelihoods among tertiary graduates, over 80% of university graduates were unwilling to start business ventures, even when resources were available, preferring to be employed. That presents a practical and theoretical problem about the drivers of entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students in subsistence markets. Some scholars attempted to analyse the entrepreneurial mindset development from a cultural perspective (Roeslie & Arianto, Citation2022), others from a trait perspective (Al-Ghazali et al., Citation2022), gender perspective (Putri et al., Citation2022; Sitaridis & Kitsios, Citation2022), entrepreneurship education (Colombelli et al., Citation2022; Manafe et al., Citation2023) and the enabling environment (Ngwoke et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, a holistic approach to antecedents of entrepreneurial mindset development is still lacking.

This study sought to offer a unique contribution by modelling the key antecedents of entrepreneurial mindset development. A deductive approach was assumed through the unification of seemingly detached empirical contributions. In developing the key antecedent of the entrepreneurial mindset, we took a holistic approach of considering students as total beings whose entrepreneurial mindset is influenced by cultural, psychological, economic and resource attributes. The study further tested the relationship between entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship, which informs practice and methodology in subsistence markets. The study’s model is unique as it introduces gender as a moderating variable. Most African societies are patriarchal, which renders the role of gender pertinent when studying tertiary students and entrepreneurship. Thus, the study’s main objective was to develop and test a hybrid model of entrepreneurial mindset determinants, entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship. The association was hypothesised to be moderated by gender.

2. Literature review

2.1. Entrepreneurship

There is no unified definition of entrepreneurship owing to the different perspectives applied to it by researchers and practitioners. Putri et al. (Citation2022) note that entrepreneurship has attracted cultural, psychological, economic and management views. From an economic point of view, entrepreneurship focuses on the supply of money, innovation and allocation of resources (Al-Ghazali et al., Citation2022). Thus, entrepreneurship depends on the availability of resources to venture into a business. From a management perspective, entrepreneurship is a way of managing, aiming at the search for opportunities without considering the available resources (Muparangi & Makudza, Citation2023). This view suggests that an entrepreneur identifies an opportunity and then looks for necessary resources. From a cultural point of view, entrepreneurship is a process of developing the community through venture creation and venture growth maximisation (García et al., Citation2022; Manafe et al., Citation2023). Psychological views of entrepreneurship see an entrepreneur as an individual possessing risk-taking, leadership and crisis-management skills (da Silva Copelli et al., Citation2019). According to this view, the primary determinant of entrepreneurship is an individual, not his environment (cultural view) or resource (economic view). Contemporary researchers such as García et al. (Citation2022) explain entrepreneurship as establishing a business organisation that provides services and goods, creates wealth and employment and contributes to the gross domestic product. Thus, entrepreneurship is uncovering and developing opportunities to create value through innovation and seizing them regardless of the location of resources (Hartmann et al., Citation2022). In this study, we endorse all diverse views that juxtapose entrepreneurship with risk-taking, exploitation of business opportunities and value creation.

2.2. Entrepreneurial mindset among university students

The entrepreneurship mindset orientates individual behaviours toward activities and outcomes related to entrepreneurship (Saptono et al., Citation2020); hence, Bosman and Fernhaber (Citation2018) perceive it as the inclination to discover, evaluate and exploit opportunities. Before becoming an entrepreneur, students should be convinced that entrepreneurship is the way to alleviate various economic challenges. To that end, Mukhtar et al. (Citation2021) argue that students fully embrace an entrepreneurial mindset when thinking like habitual entrepreneurs. Bosman and Fernhaber (Citation2018) further clarify that students do not have to start a business to adopt an entrepreneurial mindset. Instead, students’ perceptions are guided by their entrepreneurial mindset, thereby developing solutions to almost any social or business problem.

Students with entrepreneurial mindsets fervently look for new opportunities and pursue opportunities with exclusive discipline, they do not chase all opportunities but chase only the very best (Al-Ghazali et al., Citation2022). They focus on execution, do so in an adaptive manner, and engage the energies of everyone in their domain. An entrepreneurial mindset is a prerequisite for entrepreneurship (Ngwoke et al., Citation2020). Thus, for universities to alleviate the challenge of redundant graduates, the key ingredient is to impart entrepreneurial thinking to their students (Mukhtar et al., Citation2021).

2.3. Benefits of entrepreneurial mindset development in university students

If university students have a keen mind to become entrepreneurial, that brings about a pool of students ready to address the economic, social and political challenges that countries face (Bosman & Fernhaber, Citation2018). The more the students become entrepreneurial-minded, the more they become entrepreneurs and the more the economy prospers (Uvarova et al., Citation2021). Students who are entrepreneurial-minded are more likely to be successful in dealing with general life problems (Brunhaver et al., Citation2018; Mukhtar et al., Citation2021). Innovation is developed through business incubation, which is a determinant of an entrepreneurial mindset (Putri et al., Citation2022). Another empirically tested benefit of developing an entrepreneurial mindset among students is the development of agile behaviour. Agility is the ability to embrace change swiftly. Students with entrepreneurial thinking were found to be agile students who respond quickly to political, social, cultural, technological and even global changes (Karim et al., Citation2022). For instance, Munkongsujarit (Citation2017) found that the business landscape was becoming more complex as many new startup companies emerged and joined the market. Only those who were agile would survive. Some researchers concur that students with entrepreneurial mindsets enjoy other benefits that entrepreneurship itself enjoys (Abun et al., Citation2022; Bernardus et al., Citation2023). Such other benefits include, but are not limited to, personal satisfaction through gratification. Mawonedzo et al. (Citation2021) state that entrepreneurial-minded students will create employment for themselves and others, thereby reducing the unemployment rate in the country.

2.4. Theoretical analysis of entrepreneurial mindset development

Several theories of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial mindset have been developed over the years. To draw valuable meaning from such theories, it is imperative to look at them from the fields from which they come. Thus, a closer look at the theories suggests they emanate from views of psychology, culture, economics and management. From those fields, four distinct theories of entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship emerge. These clusters are resource-based entrepreneurship theories, economic entrepreneurship theories, psychological entrepreneurship theories, and cultural entrepreneurship theories.

According to resource-based entrepreneurship theories, entrepreneurial mindset development is a function of the availability of resources (Ratten, Citation2023). It is suggested that access to resources is an important predictor of entrepreneurship and the development of entrepreneurial thinking. Key resources of interest are financial resources, human resources and social capital resources (Audretsch et al., Citation2022).

On the other hand, the classical economic entrepreneurship theory suggests that an entrepreneur is not a production factor but an agent that takes risks and balances demand and supply in the economy (Walia & Chetty, Citation2020). According to this view, the main determinants of an entrepreneurial mindset are land, capital and labour. An entrepreneurial mindset is developed through developing and nurturing one’s judgement of the future demand, estimation of appropriate timings and input, judgement and calculation of probable production costs, selling prices, supervision, and administration (Mukhtar et al., Citation2021).

The psychological entrepreneurship theory focuses on individual personality characteristics to explain the determinants of an entrepreneurial mindset. Human beings have a natural inclination towards being successful and achieving in life (Feng & Chen, Citation2020). However, that drive varies from person to person. The more one has a high need for achievement, the more likely they will be entrepreneurial (Feng & Chen, Citation2020).

The cultural entrepreneurship theory considers the influence of society and the community to be a key determinant of entrepreneurial mindset development (Bernardus et al., Citation2023). Cultural contexts predict entrepreneurial mindset development through social networks, which build social relationships and life stage context based on life analyses, situations, and characteristics (Bernardus et al., Citation2023). Community experiences and cultural backgrounds push an individual into entrepreneurial thinking (Muparangi & Makudza, Citation2023). Population ecology supports environmental factors in promoting communities to be entrepreneurial (Makandwa et al., Citation2023a). presents a summary of the key theories used in this study.

Table 1. Summary of the key informant theories to this study.

2.5. Hypotheses development

2.5.1. Culture and entrepreneurial mindset development

Drawn from the cultural entrepreneurship theory, culture acts as an entrepreneurial mindset driver (Muparangi & Makudza, Citation2023). Morales et al. (Citation2022) found that entrepreneurial individuals have a high inclination to uphold the value of the family. By adopting Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, Alqarni (Citation2022) concludes that entrepreneurs tend to develop a superior entrepreneurial mindset and would want that to be passed on from generation to generation by imparting cultural values to children. Martínez-Martínez (Citation2022) highlights the importance of socio-demographic variables and the influence of entrepreneurial expectations and experiences of the population, especially in shaping perceptions towards entrepreneurial mindset development. Students from entrepreneurial cultures are more likely to be entrepreneurial (Laskovaia et al., Citation2017). Regardless of differing cultural backgrounds, entrepreneurs from different backgrounds share a common core set of entrepreneurial values, and as a result, every entrepreneur has the inherent seed of an entrepreneurial mindset, regardless of their society (McGrath & MacMillan, Citation2009). Systems of values, moral attitudes, and social influence can stimulate or limit entrepreneurial mindset development in individuals (Michalewska-Pawlak, Citation2012). Family, religion and community are the driving forces that sustain women’s commitment to entrepreneurship (Mazonde, Citation2016). However, in some African countries, culture diminishes the role of women as business leaders, which limits entrepreneurial mindset development among young women (Mazonde, Citation2016). It is against this backdrop that the following hypothesis is presented:

H1: There is a positive association between cultural determinants and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students.

2.5.2. Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial mindset development

Influenced by the resource-based theory of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education refers to the university-driven taught theory and practice of entrepreneurship that seeks to enhance students’ entrepreneurial attitudes and skills (Muparangi et al., Citation2022). Jiatong et al. (Citation2021) postulate that entrepreneurship education is associated with cultivating creative skills and competencies to enable learners to identify and act on opportunities, engage in ventures and be innovative. This is embedded in the university academic curriculum and painted in the course outlines of students. Thus, entrepreneurship theory is taught as lectures, and entrepreneurship practice is nurtured through entrepreneurship incubation centres (Muparangi et al., Citation2022). According to Hardie et al. (Citation2020), business incubation develops the entrepreneurial mindset at tertiary institutions by helping students gather the necessary skills, resources and expertise. An entrepreneurial mindset is developed as students practically experience the process of running a business (Crosina et al., Citation2024). Thus, there is a need for tertiary institutions to blend theory and practice in the teaching of entrepreneurship to augment entrepreneurial mindset development (Mawonedzo et al., Citation2021). Karambakuwa and Bayat (Citation2022) recommend using technology in teaching to promote innovative entrepreneurs. Relating to the learning mode that drives entrepreneurial mindset development, Dangaiso et al. (Citation2023) emphasise the importance of incubation learning centres which promote business start-ups whilst Mauchi et al. (Citation2011) assert that it is the role of the government to ensure that entrepreneurship education in state universities is taught by lecturers who are industry experts and coaches. Therefore, the following hypothesis is presented:

H2: There is a positive association between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students.

2.5.3. Individual determinants and entrepreneurial mindset development

Individual determinants, in relation to the psychological theory of entrepreneurship, refer to personal, physical, biological and psychological factors peculiar to a student that determine their entrepreneurial mindset (Dangaiso et al., Citation2023). Individual factors have more significance in explaining entrepreneurial mindset development than other theoretically known factors (Stefanovic et al., Citation2010). This aligns with Ripollés and Blesa (Citation2024) who note that individual and personal attributes are the primary drivers of entrepreneurial mindset development among students. Students who believe in themselves are more likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities than those with low self-esteem (Nabilla & Usman, Citation2020). Individuals who are naturally risk-takers are more likely to be entrepreneurial than those who are risk-averse (Steenkamp et al., Citation2024). Some key traits that are especially significant in explaining entrepreneurial mindset development include creativity, innovation, good management skills and a business mind (Martínez-Martínez, Citation2022). Females are generally more risk-averse than their male counterparts when venturing into new territories, regardless of the nature of the business (Muparangi & Makudza, Citation2023). Risk-averse traits can deter individuals from developing an entrepreneurial mindset (Rafiq et al., Citation2024).

H3: There is a positive association between individual determinants and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students.

2.5.4. Facilitating conditions and entrepreneurial mindset development

Facilitating conditions refer to environmental enabling factors and policies that promote entrepreneurship (Mason & Brown, Citation2014). Three general facilitating factors are the availability of venture capital, government aid and opportunities (Mason & Brown, Citation2014). Facilitating conditions emanate from the resource and economic-based theories of entrepreneurial mindset development. Therefore, if students are conscious of the existence of financial and capital support, they are more likely to develop an entrepreneurial mindset (Makudza et al., Citation2022). Universities need to partner with private companies to create a known and ready pool of funding to motivate undergraduate students to think of employment creation (Magomedova et al., Citation2023). Easy access to loan facilities at favourable rates is an important trigger for promoting entrepreneurial mindset development (Bula, Citation2012). Government aid through youth training, project funding, favourable policies and infrastructure improvement favourably support sustainable entrepreneurial mindset development (Olutuase, Citation2014). Hence, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H4: There is a positive association between facilitating conditions and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students.

2.5.5. The moderating effect of gender

The centrality of gender in entrepreneurship discourse stems from its operative effect as a lens for interrogating differing experiences of male and female entrepreneurs and their orientations to entrepreneurial behaviours (Bruni et al., Citation2004). Entrepreneurship literature is replete with popular views that female entrepreneurs face prejudices and barriers due to their gender (Riebe, Citation2012) and that males are more likely to develop an entrepreneurial mindset than their female counterparts (Makandwa et al., Citation2023b). Teen boys are 30% more likely to aspire to become entrepreneurs than their girl counterparts (Cochran, Citation2017). Gender moderates attraction and access to entrepreneurship opportunities among individuals (Makandwa et al., Citation2023b). Population studies in Zimbabwe have indicated that women outnumber men (Zimstat, Citation2022). Despite this outnumbering, the involvement of women in entrepreneurship remains limited as very few of these women dare to start new ventures (Jacob et al., Citation2023). This can be attributed to several factors, including defying social expectations, accessing funding, and dominant and aggressive male personalities (Jacob et al., Citation2023). Risk-taking is also a major constraint among aspiring female entrepreneurs in Africa (Cochran, Citation2017). Thus, the following proposition is made:

H5: Gender moderates the association between entrepreneurial mindset development and its antecedents.

2.5.6. Entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship

Developing an entrepreneurial mindset is a critical factor in the success of an entrepreneur. Studies have shown that individuals who possess an entrepreneurial mindset are more likely to identify opportunities, take calculated risks, adapt to changing circumstances, and persist in the face of challenges (Mukhtar et al., Citation2021; Saptono et al., Citation2020). Individuals who actively work on developing an entrepreneurial mindset are more likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities (Al-Ghazali et al., Citation2022). This can manifest in a variety of ways, such as starting a new business, pursuing an opportunity within an existing organization, or investing in a new venture (Al-Ghazali et al., Citation2022). Individuals who participate in entrepreneurial mindset development programmes or workshops are more likely to successfully launch and grow their own businesses (Muparangi et al., Citation2022). These programmes typically focus on building skills, fostering creativity, and encouraging a proactive attitude towards problem-solving and decision-making (Makandwa et al., Citation2023b). Jabeen et al. (Citation2017) also concluded that a strong positive relationship exists between entrepreneurial mindset development and entrepreneurship. Investing in the development of an entrepreneurial mindset may increase an individual’s likelihood of successfully starting and growing a business, hence, the following hypothesis is presented:

H6: There is a positive association between entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship.

2.6. The framework of study

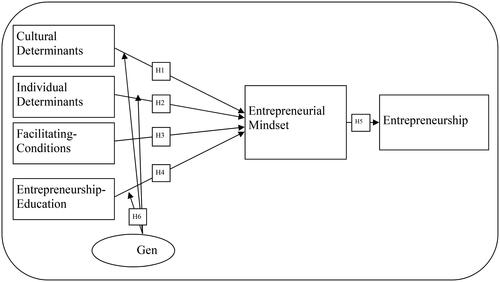

Guided by the hypotheses development section and the theories reviewed, the study presents the framework of the study in .

shows four predictor variables of entrepreneurial mindset development, namely cultural determinants, individual determinants, facilitating conditions and entrepreneurship education. These variables are posited to impact entrepreneurial mindset development whilst entrepreneurial mindset development directly impacts entrepreneurship. Gender is further presented as a moderating variable.

3. Methodology

The study targeted all undergraduate students from three universities in Zimbabwe, namely Manicaland State University of Applied Sciences (MSUAS), University of Zimbabwe (UZ) and Zimbabwe Ezekiel Guti University (ZEGU). The three universities were selected because of their strong efforts to teach entrepreneurship modules and foster entrepreneurial hub creation. A causal research design was applied to determine the cause-and-effect relationship among entrepreneurship mindset determinants, entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship among university students. In selecting the sampling type, the study considered the unique geographical and facilitating conditions of the students from each university in the sampling frame. That led to the development of three distinct strata, with each university in the sampling frame formulating a stratum. Since there were three universities in the sampling frame, the researchers came up with three strata: MSUAS, UZ and ZEGU. From each stratum, respondents were selected based on the proportion of the total number of students in each university. A sample size of 378 students was selected. Malhotra and Dash (Citation2011) argue that in framing a research problem to be analysed with factor analysis, the sample size must be at least 5 to 10 times the number of variables in the theoretical model. Thus, with seven variables, a sample size of 378 was higher than expected. Furthermore, the sample size exceeds immensely the minimum threshold suggested by Wang and Ahmed (Citation2004) who indicate that where CFA or SEM is employed to validate a scale, a sensible sample size using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method should be a minimum of 200 cases. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire. Structural equation modelling was used to analyse data. The measurement scales for the instrument were informed by previous conceptualisation of entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship (Bernardus et al., Citation2023; Feng & Chen, Citation2020; Ratten, Citation2023).

4. Data analysis

4.1. Sample profile

Male student numbers were greater than females, with males comprising 60.7% and females 39.3%. This trend was consistent with enrolment numbers in many African universities. Most respondents were conventional students (90.1%) against 9.9% block students. Second-year students were the majority group with 42.3% frequency. Third-year students were the least represented at 4%, first-year students made up 20.4% and fourth-year students were 32.4%.

4.2. Assessment of the measurement model

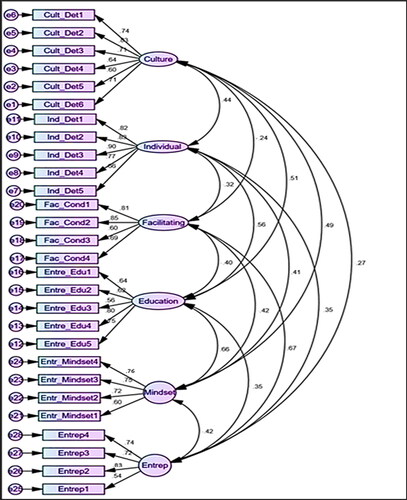

Data for the study were subjected to Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to measure and examine the psychometric properties. CFA assesses the factor structure of a set of observed variables. presents the confirmatory analysis results.

The CFA results indicated a good model fit: CMIN/DF = 2.207, GFI = 0.935, AGFI = 0.918, CFI = 0.956, RMSEA = 0.059. Using the guiding principles of Hair et al. (Citation2010), the study concluded that all model fit indices were within the acceptable range.

The study assessed unidimensionality through the assessment of factor loadings. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), standardised factor loadings for latent variables should have a minimum loading of 0.5. Using Hair et al. (Citation2010) cut-off of 0.5, the study found that all items had factor loadings higher than the cut-off. The lowest factor loading recorded was 0.671 and the highest was 0.90.

A convergent validity test examines the relatedness of similar constructs (Taherdoost, Citation2018). The study analysed the Average Variance Explained (AVE) to examine convergent validity. AVE relates to a measure of the amount of variance captured by a construct in relation to the amount of variance due to measurement error (Memon et al., Citation2013). The study worked with the cut-off threshold of 0.5 (Memon et al., Citation2013).

The results in are evidence of convergent validity as all AVE coefficients were higher than the cut-off of 0.5. Cultural determinants recorded the lowest AVE of 0.504, whilst the highest of 0.637 was recorded for individual determinants.

Table 2. Average Variance Explained (AVE).

4.3. Reliability

The study used the Cronbach Alpha (CA/α) and Construct Reliability (CR) test statistics to measure reliability. Ab Hamid et al. (Citation2017) suggest that the minimum cut-off threshold for both tests should be 0.70 if the measurement scale is to be deemed reliable. Results in , thus prove the internal consistency of the measurement model since all Cronbach alpha values were higher than 0.70, with the lowest being 0.727. The same conclusion was reached using the construct reliability test, which recorded the least coefficient of 0.737.

Table 3. Discriminant validity results.

4.4. Discriminant validity

A discriminant validity test measures the extent of unrelatedness of constructs (Taherdoost, Citation2018). Ab Hamid et al. (Citation2017) note that discriminant validity is guaranteed if the shared variance between a pair of constructs is greater than their individual average variance extracted. Discriminant validity results are shown in .

The results in are evidence of discriminant validity. The square roots of all AVE values for the latent constructs are greater than the inter-correlations of the latent constructs.

4.5. Hypotheses testing

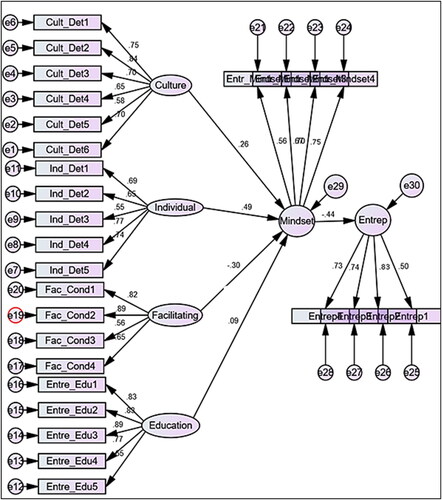

The study used the structural equation model analysis to validate the entrepreneurship model. Multicollinearity was diagnosed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance tests. The tolerance values for the study’s variables were higher than the minimum threshold of 0.2 (Byrne, Citation2013). Conversely, using the VIF test, all variables recorded values which were below the acceptable cut-off of 5.0 (Byrne, Citation2013). In addition, the normality assumption was passed as data were subjected to the univariate normality test using the skewness and kurtosis values. All values were within acceptable ranges of −2 to +2 for skewness and kurtosis (Hair et al., Citation2010). presents the diagrammatic representation of the structural model.

In testing the moderation effect, we applied the Hayes PROCESS Macro for SPSS (Hayes & Rockwood, Citation2017). presents the moderation effect.

Table 4. The moderation effect of gender.

shows that the overall model for individual determinants, entrepreneurship education and cultural determinants on entrepreneurial mindsets were all valid with p-values of .00. However, a closer look at the moderation effects of gender shows that not all moderating interactions were statistically significant. The moderation effect of gender on the link between individual determinants and entrepreneurial mindset was statistically insignificant (βInt_1 = 0.0366 [−0.0718, 0.1450]; t = 0.6639; p = .5071 > .05). The moderation effect of gender on the link between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial mindset was also statistically insignificant (βInt_2 = 0.0425 [−0.2197, 0.3046]; t = 0.3186; p = .7502 > .05). A significant moderation was established on the effect of gender on the link between cultural determinants and entrepreneurial mindset (βInt_3 = 0.5705 [0.3128, 0.8282]; t = 4.3519; p = .00 < .05).

5. Discussion

The study’s first hypothesis sought to examine the association between cultural determinants and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students. shows a path estimate of 0.258 (p = .00; T = 4.477). This indicates a significant positive relationship between cultural determinants and entrepreneurial mindset development in tertiary students. A significant correlation coefficient of 0.487 also proves that cultural attributes have a positive association with the development of an entrepreneurial mindset, hence H1 was accepted. A significant positive relationship between cultural determinants and entrepreneurial mindset development suggests that cultural factors play a crucial role in shaping the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours related to entrepreneurship. This means that aspects such as social norms, values, beliefs, and practices within a specific culture influence how individuals perceive and approach entrepreneurship. Thus, it can be interpreted further that tertiary students’ entrepreneurial mindset was influenced positively by their norms, values, beliefs, religion, peers, friends, family and role models. This means that culture plays a crucial role in nurturing students to be venture-oriented and to think like business people who, if opportunities avail, will start their businesses. The findings from this study are consistent with previous studies (Martínez-Martínez, Citation2022; Mawonedzo et al., Citation2021). Michalewska-Pawlak (Citation2012) found that systems of values, morality attitudes and social influence can stimulate or limit entrepreneurial thinking in individuals. Other researchers found statistical significance between cultural determinants and entrepreneurial mindset (Bwisa & Ndolo, Citation2011; Ijaz et al., Citation2012).

Table 5. The results of the causal analysis.

The second hypothesis states that there is a positive association between individual determinants and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students. Using the results in , the study found a path estimate of 0.101. However, the association was not statistically significant as the p-value of .054 was above the alpha value of 0.05. Conversely, the T-value of 1.929 was in the rejection region since it was below the threshold of 1.96 (at a 95% confidence interval). Thus, H2 was rejected. This means that tertiary students under study did not consider personality traits, intrinsic motivational factors and the need for achievement to be important elements that stimulate their behaviour to be entrepreneurial. It shows that there is no relationship between certain personal traits or characteristics (individual determinants) and the development of an entrepreneurial mindset among tertiary students. In other words, specific traits in students do not guarantee entrepreneurial mindset development. This result contradicts contemporary studies such as Varamäki et al. (Citation2015) and Ward et al. (Citation2019) which found a positive association. The divergence in results could be attributed to different personalities and individual traits.

The third hypothesis posits that there is a positive association between facilitating conditions and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students. The study found a path estimate of 0.298 (T = 4.981), which proves that facilitating conditions have a moderate positive impact on the entrepreneurial mindset development of tertiary students. The findings were statistically significant with a p-value of .00 and a correlation of 0.416 further validating the significance of the moderate relationship between facilitating conditions and entrepreneurial mindset development. Hence, H3 was accepted. A positive association between facilitating conditions and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students means that creating an environment that supports and encourages entrepreneurial thinking can lead to increased development of an entrepreneurial mindset among students. In this context, providing students with resources, support, and opportunities to explore and develop their entrepreneurial skills can help them cultivate a mindset that is characterised by innovation, risk-taking, and a proactive attitude towards identifying and pursuing entrepreneurial opportunities. When students have access to mentors, networks, training programmes, funding, and other forms of support, they are more likely to embrace an entrepreneurial mindset and take action towards starting their own ventures or pursuing entrepreneurial endeavours. Several studies validated these results as they found related findings (Rodriguez & Lieber, Citation2020; Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2022).

The fourth hypothesis of the study suggests that there is a positive association between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial mindset development among tertiary students. This hypothesis was accepted and supported based on the results in (β = 0.477; T = 6.870; r = 0.555; p = .00). The results mean that teaching students entrepreneurship courses helps them think like business people. Entrepreneurship education helps tertiary students evaluate opportunities and threats and develop good business ventures. This means that students who are exposed to entrepreneurship education are more likely to develop the skills, knowledge, and attitudes necessary to succeed as entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship education provides students with the opportunity to learn about different aspects of starting and running a business, such as business planning, marketing, finance, and leadership. By engaging in practical activities and real-world projects, students are able to apply their knowledge in a hands-on fashion, which can help them develop problem-solving skills, creativity, and a willingness to take risks. These results were in line with previous studies. Mudondo (Citation2014) found that introducing entrepreneurship education in the university curriculum increased students’ awareness and interest in becoming entrepreneurs upon graduating. Similarly, Abaho (Citation2013) concluded that interaction with successful entrepreneurs, experimental learning and entrepreneurial lectures lead to the entrepreneurial values of students. Mauchi et al. (Citation2011) found that entrepreneurship education was still in its infancy in Zimbabwean tertiary education.

The fifth hypothesis tested the association between entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship. The results of this study proved that there is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship. A path estimate of 0.448, with a p-value of .00 (T = 5.169) was obtained, which means that the development of an entrepreneurial mindset predicts venture creation. The results also mean that individuals who possess characteristics of an entrepreneurial mindset are more likely to become successful entrepreneurs. Having an entrepreneurial mindset can also contribute to the development of essential entrepreneurial skills such as leadership, decision-making, and networking. These skills, combined with the right mindset, can help individuals navigate the complexities of starting and running a business successfully. These results concurred with the findings of Bilic et al. (Citation2011) and Bwisa and Ndolo (Citation2011) who also found that an entrepreneurial mindset relates positively to entrepreneurship.

The final hypothesis investigated the moderation effect of gender on the relationships among individuals, entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial determinants, cultural determinants and entrepreneurial mindset development. The results show that the moderation effect of gender on the link between individual determinants and entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial mindset was statistically insignificant (p > .05). The only significant moderation of gender was obtained on the link between cultural determinants and entrepreneurial mindset (βInt_3 = 0.5705 [0.3128, 0.8282]; t = 4.3519; p = 0.00 < .05). This means that being male or female influences the extent to which one becomes entrepreneurial. Zimbabwean society is patriarchal and places more emphasis on the male members of the society to act as breadwinners. This inordinately drives male society members to devise ways of how to make ends meet, which may lead to entrepreneurial mindset development. This notion aligns with Adom and Anambane (Citation2020).

6. Implications

The study heightens the need for universities to include entrepreneurial education in their curriculum. Of the determinants of entrepreneurial mindset in this study, entrepreneurial education is uppermost, which informs the need for university students to be taught a compulsory module in entrepreneurship. The study also recommends the use of a blended teaching approach in which both theory and practice are taught, with the practical component being further nurtured through entrepreneurial hubs. The study further implies the need for a cultural shift towards unfreezing the notion that a university qualification alone would enable one to get a good job and earn a comfortable livelihood. There is a strong need to enforce a new cultural perspective which fosters employment creation through entrepreneurial mindset development and starting ventures. Female students should be encouraged to break the glass ceiling and challenge male students in being entrepreneurial. Students should also be trained so that they develop self-esteem to become confident individuals, regardless of gender. The study further emphasises the need for scholars to develop research-based models which strongly emphasise gender and entrepreneurship among students in various institutions of higher learning.

7. Limitations

Despite making significant contributions to academia, policy and methodological spheres, this study had some limitations. The study focused only on student entrepreneurial behaviour in three universities in Zimbabwe. This may not be a fair representation of all other universities in the country. However, to minimise the effect of the limitation, the study used a large sample size which was generated at a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error. In addition, the study has a theoretical limitation in developing the determinants of entrepreneurial mindset. Only four determinants were considered in this study, yet there could be many more to which literature relates. However, the determinants used in this study were widely referred to in extant studies on entrepreneurial theories.

8. Conclusions

The study concludes that cultural determinants are pivotal in developing an entrepreneurial mindset among tertiary students. Furthermore, personal characteristics strongly influence the maturing of an entrepreneurial mental state of students from institutions of higher learning. Not to be ruled out is the influence of the facilitating conditions on how students develop their minds towards entrepreneurship. These conditions are featured prominently in the current scholarship’s responses. A key conclusion drawn from this study is that entrepreneurship education capacitates and empowers tertiary students. Most of the students interviewed indicated that despite harbouring entrepreneurial ideas, they lacked the knowledge to pursue them. The gender component was a topical issue, leading to the conclusion that gender stereotype is still rife within the entrepreneurship arena. Furthermore, cultural determinants and gender roles influence the uptake of females in entrepreneurial roles.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Forbes Makudza

Forbes Makudza is a full-time lecturer and chartered marketer based at the University of Zimbabwe. His research interests are in entrepreneurial marketing, digital marketing, social commerce and business management. Over the years he has taught various marketing and business management modules at various other universities such as Bindura University of Science Education (BUSE), Zimbabwe Ezeckiel Guti University and Manicaland State University. Forbes is available for local, regional or international collaborations.

Tendai Makwara

Tendai Makwara graduated from the Central University of Technology, Free State. Bloemfontein, South Africa with a PhD in Management Sciences (Business Management). He also holds a Master of Philosophy degree and a Post Graduate Diploma (Cum Laude) in (HIV and AIDS) in Management from Stellenbosch University, South Africa among other qualifications. Over the years, he has taught various business, human resources and health courses in the higher education and high school learning environments in Zimbabwe and South Africa. He also self and co-authored several articles in his areas of research interests, including health, social issues, entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility.

Rosemary F. Masaire

Rosemary F. Masaire holds a PhD in Entrepreneurship and Business Leadership as well as a Master and Bachelor of Commerce in Marketing. She also holds a Higher National Diploma in Marketing among other qualifications. She is a senior lecturer at the University of Zimbabwe, Faculty of Business Management Sciences and Economics and a visiting lecturer at Africa University (Zimbabwe). She is also a peer reviewer with the Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education (ZIMCHE). Her areas of research interest include entrepreneurship, marketing, reputation management, design thinking and innovation as well as social issues.

Phillip Dangaiso

Phillip Dangaiso is a full-time lecturer and academic researcher at Chinhoyi University of Technology, Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe. His research interests are in marketing management, services marketing, green marketing, digital marketing, social marketing, consumer behaviour, and brand management.

Lucky Sibanda

Lucky Sibanda is a doctoral candidate in Management at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa. He holds a Master’s degree in Business Administration (Entrepreneurship), a Bachelor of Technology degree in Business Administration (cum laude), and a Diploma in Entrepreneurship (cum laude) from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Over the past eleven years, he has taught face-to-face and distance learning modes in higher education. He also co-authored eleven peer-reviewed academic articles and one book chapter, presented at six conferences and is a research supervisor for honours programs at MANCOSA. His research interests include issues on student success and entrepreneurship.

References

- Ab Hamid, M. R., Sami, W., & Mohmad Sidek, M. H. (2017). Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 890(1), 012163. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/890/1/012163

- Abaho, E. (2013). Entrepreneurial curriculum as an antecedent to entrepreneurial values in Uganda: A SEM model. Global Advanced Research Journal of Management and Business Studies, 2(2), 2315–5086. http://garj.org/garjmbs/index.htm

- Abun, D., Foronda, S. L. G. L., Julian, F. P., Quinto, E. A., & Magallanes, T. (2022). Business intention of students with family business and entrepreneurial education background. International Journal of Business Ecosystem & Strategy, 4(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.36096/ijbes.v4i2.316

- Adom, K., & Anambane, G. (2020). Understanding the role of culture and gender stereotypes in women’s entrepreneurship through the lens of the stereotype threat theory. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(1), 100–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-07-2018-0070

- Al-Ghazali, B. M., Shah, S. H. A., & Sohail, M. S. (2022). The role of five big personality traits and entrepreneurial mindset on entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Saudi Arabia. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 964875. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2022.964875/BIBTEX

- Alqarni, A. M. (2022). Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in relation to learning behaviours and learning styles: A critical analysis of studies under different cultural and language learning environments. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 18(1), 721–739. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.545381401163832

- Audretsch, D., Cruz, M., & Torres, J. (2022). Revisiting entrepreneurial ecosystems. Policy Research Working Paper 10229. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099413211142227958/IDU04c1d171703fac0466a083eb0c835a900e26d.

- Bernardus, D., Kurniawan, J. E., Murwani, F. D., & Yulianto, J. E. (2023). Star intrapreneurs:characteristics of Indonesian corporate entrepreneurs. Heliyon, 9(1), e12700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12700

- Bilic, I., Prka, A., & Vidovi, G. (2011). How does education influence entrepreneurship orientation? Case study of Croatia. Management, 16(1), 115–128. https://hrcak.srce.hr/clanak/103436

- Bosman, L., & Fernhaber, S. (2018). Defining the entrepreneurial mindset. In L. Bosman & S. Fernhaber (Eds.), Teaching the entrepreneurial mindset to engineers (pp. 7–14). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61412-0_2

- Brunhaver, S. R., Bekki, J. M., Carberry, A. R., London, J. S., & Mckenna, A. F. (2018). Development of the engineering student entrepreneurial mindset assessment (ESEMA). Advances in Engineering Education, 7(1), n1. http://engineeringunleashed.com/keen/about/

- Bruni, A., Gherardi, S., & Poggio, B. (2004). Entrepreneur-mentality, gender and the study of women entrepreneurs. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(3), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810410538315

- Bula, H. O. (2012). Evolution and theories of entrepreneurship: A critical review on the Kenyan perspective. International Journal of Business and Commerce, 1(11), 81–96. http://ir-library.ku.ac.ke/handle/123456789/9389

- Bwisa, H. M., & Ndolo, J. M. (2011). Culture as a factor in entrepreneurship development: A case study of the Kamba culture of Kenya. Opinion, 1(1), 20–29. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:15483057

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with Mplus. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203807644

- Cochran, S. L. (2017). The role of gender in entrepreneurship education [PhD thesis]. University of Missouri-Columbia. https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10355/61911/research.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Colombelli, A., Loccisano, S., Panelli, A., Pennisi, O. A. M., & Serraino, F. (2022). Entrepreneurship education: The effects of challenge-based learning on the entrepreneurial mindset of university students. Administrative Sciences, 12(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010010

- Crosina, E., Frey, E., Corbett, A., & Greenberg, D. (2024). From negative emotions to entrepreneurial mindset: A model of learning through experiential entrepreneurship education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 23(1), 88–127. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2022.0260

- da Silva Copelli, F. H., Erdmann, A. L., & Dos Santos, J. L. G. (2019). Entrepreneurship in Nursing: an integrative literature review. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 72(suppl 1), 289–298. (Associacao Brasilerira de Enfermagem. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0523

- Dangaiso, P., Makudza, F., Jaravaza, D. C., Kusvabadika, J., Makiwa, N., & Gwatinyanya, C. (2023). Evaluating the impact of quality antecedents on university students’ e-learning continuance intentions: A post-COVID-19 perspective. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2222654. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2222654

- Dungey, C., & Ansell, N. (2022). ‘Not all of us can be nurses’: Proposing and resisting entrepreneurship education in rural Lesotho. Sociological Research Online, 27(4), 823–841. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780420944967

- Feng, B., & Chen, M. (2020). The impact of entrepreneurial passion on psychology and behavior of entrepreneurs. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1733. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01733

- García, M. D., Moreno Meneses, J. M., & Valencia Sandoval, K. (2022). Theoretical review of entrepreneur and social entrepreneurship concepts. Journal of Administrative Science, 3(6), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.29057/jas.v3i6.7687

- Goyayi, M. (2022). Why tackling graduate unemployment in SA is important for post-covid19 economic recovery. https://ddp.org.za/blog/2022/06/03/why-tackling-graduate-unemployment-in-sa-is-important-for-post-covid19-economic-recovery/

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2010). SEM: An introduction. In Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (17th ed., pp.629–686). Pearson.

- Hardie, B., Highfield, C., & Lee, K. (2020). Entrepreneurship education today for students’ unknown futures. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 4(3), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.33902/JPR.2020063022

- Hartmann, S., Backmann, J., Newman, A., Brykman, K. M., & Pidduck, R. J. (2022). Psychological resilience of entrepreneurs: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(5), 1041–1079. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.2024216

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2016.11.001

- Ijaz, M., Yasin, G., & Zafar, M. J. (2012). Cultural factors effecting entrepreneurial behaviour among entrepreneurs. Case study of Multan, Pakistan. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 2(26), 908–917. https://archive.aessweb.com/index.php/5007/article/view/2269

- Jabeen, F., Faisal, M. N., & I. Katsioloudes, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial mindset and the role of universities as strategic drivers of entrepreneurship: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(1), 136–157. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-07-2016-0117

- Jacob, T., Thomas, V. R., & George, G. (2023). Female entrepreneurship: Challenges faced in a global perspective. In A. D. Daniel, & C. Fernandes (Eds.,), Female entrepreneurship as a driving force of economic growth and social change (pp. 90–110). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-7669-7.ch006

- Jiatong, W., Murad, M., Bajun, F., Tufail, M. S., Mirza, F., & Rafiq, M. (2021). Impact of entrepreneurial education, mindset, and creativity on entrepreneurial intention: Mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 724440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724440

- Karambakuwa, J. K., & Bayat, M. S. (2022). Understanding entrepreneurship training in incubation hubs. Indonesian Journal of Innovation and Applied Sciences, 2(3), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.47540/ijias.v2i3.568

- Karim, M. S., Sena, V., & Hart, M. (2022). Developing entrepreneurial career intention in entrepreneurial university: The role of counterfactual thinking. Studies in Higher Education, 47(5), 1023–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2055326

- Laskovaia, A., Shirokova, G., & Morris, M. H. (2017). National culture, effectuation, and new venture performance: Global evidence from student entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 49(3), 687–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9852-z

- Magomedova, N., Villaescusa, N., & Manresa, A. (2023). Exploring the landscape of university-affiliated venture funds: An archetype approach. Venture Capital, 25(3), 317–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2022.2163001

- Makandwa, G., Makudza, F., & Muparangi, S. (2023a). Augmenting family businesses in craft tourism through entrepreneurial skills development among southern Africa rural women. In M. Valeri (Ed.), Family businesses in tourism and hospitality: Innovative studies and approaches (pp. 15–31). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28053-5_2

- Makandwa, G., Makudza, F., & Muparangi, S. (2023b). Women’s participation in community-based tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case of Sengwe community in Zimbabwe. In K. Dube, O. L. Kupika, D., & Chikodzi (Eds.), COVID-19, tourist destinations and prospects for recovery: Volume three: A South African and Zimbabwean perspective (pp. 115–131). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28340-6_7

- Makudza, F., Mandongwe, L., & Muridzi, G. (2022). Towards sustainability of single-owner entities: An examination of financial factors that influence growth of sole proprietorship. Journal of Industrial Distribution & Business, 13(5), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.13106/jidb.2022.vol13.no5.15

- Makwara, T., Sibanda, L., & Iwu, C. G. (2022). To what extent is entrepreneurship a sustainable career choice for the youth? A post-covid-19 descriptive analysis. In A. A. Eniola, C. G. Iwu, & A. P. Opute (Eds.), The Future of Entrepreneurship in Africa. (pp. 59–79). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003216469-4

- Malhotra, N. K., & Dash, S. (2011). Marketing research: An applied orientation (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2989267

- Manafe, M. W. N., Ohara, M. R., Gadzali, S. S., Harahap, M. A. K., & Ausat, A. M. A. (2023). Exploring the relationship between entrepreneurial mindsets and business success: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Journal on Education, 5(4), 12540–12547. https://doi.org/10.31004/joe.v5i4.2238

- Martínez-Martínez, S. L. (2022). Entrepreneurship as a multidisciplinary phenomenon: culture and individual perceptions in business creation. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 35(4), 537–565. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARLA-02-2021-0041

- Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth-oriented entrepreneurship. Final Report to OECD 30, 77–102. http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Entrepreneurial-ecosystems.pdf

- Mauchi, F. N., Karambakuwa, R. T., Gopo, R. N., & Kosmas, N. (2011). Entrepreneurship education lessons: A case of Zimbabwean tertiary education institutions. Educational Research, 2(7), 1306–1311. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Entrepreneurship-education-lessons%3A-a-case-of-Mauchi-Karambakuwa/09a540af3e69ee58f1969af0460113592e428576

- Mawonedzo, A., Tanga, M., Luggya, S., & Nsubuga, Y. (2021). Implementing strategies of entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwe. Education + Training, 63(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-03-2020-0068

- Mazonde, N. B. (2016). Culture and the self-identity of women entrepreneurs in a developing country [PhD thesis]. University of the Witwatersrand. https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/c24c3a67-afc8-4e9d-8560-377cb3bdc22b/content

- McGrath, R., & MacMillan, I. (2009). Discovery driven growth: A breakthrough process to reduce risk and seize opportunity. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Memon, A., Abdul Rahman, I., Abdul Aziz, A. A., & Abdullah, N. H. (2013). Using structural equation modelling to assess effects of construction resource related factors on cost overrun. World Applied Sciences Journal, 21(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.21.mae.9995

- Michalewska-Pawlak, M. (2012). Social and cultural determinants of entrepreneurship development in rural areas in Poland. University of Wrocław, 2(1), 51–65.

- Morales, G. L. O., Aguilar, J. C. R., & Morales, K. Y. L. (2022). Culture as an obstacle for entrepreneurship. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00230-7

- Mudondo, C. D. (2014). Entrepreneurial perceptions and intentions : An empirical survey of students in the Faculty of Commerce at Great Zimbabwe University, Zimbabwe. International Journal of Management Sciences, 2(1), 1–11.

- Mukhtar, S., Wardana, L. W., Wibowo, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2021). Does entrepreneurship education and culture promote students’ entrepreneurial intention? The mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1918849. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1918849

- Munkongsujarit, S. (2017). Business incubation model for startup company and SME in developing economy: A case of Thailand. Proceedings of PICMET 2016 - Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology: Technology Management for Social Innovation (pp. 74–81). https://doi.org/10.1109/PICMET.2016.7806786

- Muparangi, S., & Makudza, F. (2023). Harnessing psychological capital to augment employee engagement in the micro-finance SME sector. Management of Sustainable Development, 15(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.54989/msd-2023-0001

- Muparangi, S., Makudza, F., & Makandwa, G. (2022). Entrepreneurial education: A panacea to formalisation of the informal sector. Management of Sustainable Development, 14(2), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.54989/msd-2022-0010

- Nabilla, T., & Usman, O. (2020). The effect of self-efficacy, motivation, and independence to the entrepreneurial intention. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3637329

- Ngwoke, A. N., Aneke, A. O., & Oraelosi, C. C. (2020). Developing entrepreneurial mindset in the Nigerian child through quality early childhood education. International Journal of Studies in Education, 16(2), 162–174. https://ijose.unn.edu.ng/wp-content/uploads/sites/224/2020/07/pp-162-174-Vol.16-No.-2.pdf

- Olutuase, S. O. (2014). Entrepreneurship model for sustainable economic development in developing countries. Univesity of Jos. http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/1173

- Putri, L., Rahmawati, R., & Putri, L. D. (2022). Formation of an entrepreneur mindset in creating competitiveness of female entrepreneurs. International Journal of Social Science, 2(1), 1179–1186. https://doi.org/10.53625/ijss.v2i1.2363

- Rafiq, M., Yang, J., & Bashar, S. (2024). Impact of personality traits and sustainability education on green entrepreneurship behavior of university students: Mediating role of green entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 14(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-05-2020-0130

- Ratten, V. (Ed.). (2023). Entrepreneurship business debates: Multidimensional perspectives across geo-political frontiers. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1071-7

- Riebe, M. (2012). Do highly accomplished female entrepreneurs tend to ‘give away success’?. In K. D. Hughes, & J. E. Jennings (Eds.), Global women’s entrepreneurship research (Chapter 8). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ripollés, M., & Blesa, A. (2024). The role of teaching methods and students’ learning motivation in turning an environmental mindset into entrepreneurial actions. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(2), 100961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2024.100961

- Rodriguez, S., & Lieber, H. (2020). Relationship between entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial mindset, and career readiness in secondary students. Journal of Experiential Education, 43(3), 277–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825920919462

- Roeslie, S. H., & Arianto, R. F. (2022). Impact of entrepreneurial culture, entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial mindset, on entrepreneurial intention. Budapest International Research and Critics Institute-Journal (BIRCI-Journal, 5(2), 12581–12594. https://doi.org/10.33258/birci.v5i2.5101

- Saptono, A., Wibowo, A., Narmaditya, B. S., Karyaningsih, R. P. D., & Yanto, H. (2020). Does entrepreneurial education matter for Indonesian students’ entrepreneurial preparation: The mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset and knowledge. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1836728. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1836728

- Sitaridis, I., & Kitsios, F. C. (2022). Gendered personality traits and entrepreneurial intentions: Insights from information technology education. Education + Training, 64(7), 1018–1034. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-12-2020-0378

- Steenkamp, A., Meyer, N., & Bevan-Dye, A. L. (2024). Self-esteem, need for achievement, risk-taking propensity and consequent entrepreneurial intentions. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajesbm.v16i1.753

- Stefanovic, I., Prokic, S., & Rankovic, L. (2010). Motivational and success factors of entrepreneurs: The evidence from a developing country. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta u Rijeci/Proceedings of Rijeka School of Economics, 28(2), 251–269. https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/93452

- Taherdoost, H. (2018). A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manufacturing, 22(2), 960–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.03.137

- The World Bank Group. (2020). Sub-Saharan Africa: Tertiary education (pp. 1–12). https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/908af3404023a2c31ef34853bba4fe60-0200022022/original/One-Africa-TE-and-COVID-19-11102021.pdf

- Uvarova, I., Mavlutova, I., & Atstaja, D. (2021). Development of the green entrepreneurial mindset through modern entrepreneurship education. IOP Conference Series, 628(1), 012034. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/628/1/012034

- Valencia-Arias, A., Arango-Botero, D., & Sánchez-Torres, J. A. (2022). Promoting entrepreneurship based on university students’ perceptions of entrepreneurial attitude, university environment, entrepreneurial culture and entrepreneurial training. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 12(2), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-07-2020-0169

- Varamäki, E., Joensuu, S., Tornikoski, E., & Viljamaa, A. (2015). The development of entrepreneurial potential among higher education students. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 22(3), 563–589. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-02-2012-0027

- Walia, A., & Chetty, P. (2020). The economic theories of entrepreneurship. Project Guru. https://www.projectguru.in/the-economic-theories-of-entrepreneurship/

- Wang, C. L., & Ahmed, P. K. (2004). The development and validation of the organisational innovativeness construct using confirmatory factor analysis. European Journal of Innovation Management, 7(4), 303–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601060410565056

- Ward, A., Hernández-Sánchez, B. R., & Sánchez-García, J. C. (2019). Entrepreneurial potential and gender effects: the role of personality traits in university students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02700

- Zimstat. (2022). 2022 first quarter labour force survey (pp. 1–34). https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/2022_First_Quarter_QLFS_Report.pdf