Abstract

This study examines challenges faced by middle-level social studies teachers in West Gojjam, Ethiopia, while implementing the Constructivist Teaching and Learning Approach (CTLAT). 178 social studies teachers were randomly selected and eight were chosen using maximum variation sampling based on characteristics such as teaching experience, female representation, school location, and willingness to observe the classroom. Findings indicate a lack of commitment, resource scarcity, teacher and student pedagogical preferences, and inadequate training. Additional obstacles, including teachers’ deficiencies in constructivist skills, student preference for note-taking, and a lack of accountability, affected the practice of CTLA. The study emphasizes that institutional, teacher, student, parent, and curriculum-related challenges significantly affect the implementation of CTLA in social studies classrooms. To overcome these challenges, teachers are encouraged to adopt constructivist techniques and stay informed through reading, professional development, and sharing experiences. The study concludes with a request for educational institutions and stakeholders to prioritize and emphasize CTLA adoption.

Introduction

Education, recognized as the means of transmitting culture, plays a pivotal role in societal advancement (Spiel et al., Citation2018). It serves as an agent for critical thinking, propels scientific progress, and contributes to sustainable development (Sayed & Ahmed, Citation2015). The recent education policy in Ethiopia underscores the importance of imparting both indigenous knowledge and scientific discoveries to future generations, fostering innovation and creativity. To fulfill educational objectives, teachers are urged to embrace diverse and appropriate teaching methodologies, with the constructivist approach being a notable inclusion (MoE, Citation2022a).

The constructivist approach to learning, as articulated by Dewey, Vygotsky, and Piaget, emphasizes that learning can facilitate individuals by providing meaningful and relevant information (Devi, Citation2019; Gordon, Citation2009; Pardjono, Citation2016). Dewey (Citation1958) underscored education rooted in real-life contexts, promoting continuous growth and practical engagement with the world, while Lev Vygotsky and Cole (Citation1978) highlighted the importance of dialogue, collaboration, and interaction with knowledgeable peers in knowledge acquisition, emphasizing communication and cultural tools. Piaget stressed the active role of learners in constructing understanding through hands-on experiences and continuous exploration of their surroundings (Ackermann, Citation2004). These educational theorists argue the traditional notion of passive learning, in which knowledge is simply passed from educator to student. Instead, they contend for active and constructivist learning environments where students are actively involved, socially engaged, and intellectually motivated to construct meaningful understanding from their experiences (Gray & MacBlain, Citation2015).

Constructivist teaching environments are specifically designed to support active learning processes. Honebein (Citation1996) outlines goals for designing such environments, including providing experiences that bridge knowledge construction, promoting learner autonomy, and facilitating authentic tasks that mirror real-life challenges. These environments encourage students to engage actively with content, collaborate with peers, and apply their learning to solve practical problems. Von Glasersfeld (Citation2012) further elaborates on the constructivist approach, emphasizing its focus on student-centered learning and the importance of facilitating students’ understanding rather than merely transmitting information.

This approach necessitates that teachers act as guides and facilitators, providing scaffolding that supports students’ independent learning journeys. Learning, according to Von Glasersfeld (Citation2012), involves much more than a simple stimulus-response process; it requires self-regulation and the creation of conceptual frameworks through reflection and abstraction. Effective problem-solving, therefore, does not stem from merely recalling memorized "correct" answers. Instead, it involves viewing a problem as a personal challenge or a barrier to achieving a specific goal, thus fostering deeper engagement and understanding.

Recent studies have also explored the integration of constructivism with modern educational frameworks. Triantafyllou (Citation2024) discusses the relationship between fundamental pedagogical concepts of constructivism and the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework, highlighting the importance of aligning instructional strategies with technological advancements to enhance learning outcomes. Additionally,Triantafyllou (Citation2022b) provides insights into the creation of constructivist learning environments that support student-centered learning and the development of critical thinking skills.The constructivist approach to learning emphasizes that learners construct knowledge through their experiences and reflections, making learning an active and contextualized process (Bada & Olusegun, Citation2015; Honebein, Citation1996; Shah, Citation2019; Von Glasersfeld, Citation2012). This theoretical framework posits that understanding is built through interaction with the world and the integration of new information with existing cognitive structures. Constructivist teaching methods highlight the importance of active engagement, encouraging learners to explore, question, and connect concepts to their personal experiences and prior knowledge (Applefield et al., Citation2000). Constructivists argue that individuals construct knowledge and meaning through their experience (Bada & Olusegun, Citation2015; Hein, Citation1991). This teaching and learning approach prioritizes the learner’s role over the teacher’s input (Zhu et al., Citation2011). In constructivist settings, students are encouraged to discuss, analyze, and present their ideas, fostering an environment that emphasizes critical thinking, creativity, active inquiry participation, personal relevance, and shared control over learning (Carlson & Wiedl, Citation2013). Students can create knowledge from their daily lives by acquiring such skills (Taylor et al., Citation1997; Triantafyllou, Citation2022a).

Constructivist teaching and learning techniques are effective in addressing real-world challenges by promoting critical thinking and problem-solving. These methods enable learners to apply knowledge in diverse and practical contexts (Akpan & Beard, Citation2016; Honebein, Citation1996; Mbise & Lekule, Citation2023; Stauffacher et al., Citation2006). Constructivist strategies often include collaborative learning, project-based activities, and inquiry-based tasks, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter and enhancing the retention of knowledge (Alexander, Citation1999). These methods create an immersive teaching and learning environment through interactive approaches that allow students to explore their emotions, thoughts, and problem-solving strategies (Zajda & Zajda, Citation2021). Constructivist strategies provide learners with essential skills and long-term understanding through active participation in curriculum-based and extracurricular activities (Charmaz, Citation2020).

The prevailing education curriculum worldwide strongly advocates 21st-century CTLA (Orakcı, Citation2020). Similarly, in Ethiopian schools, the middle-level social studies curriculum aims to enhance students’ critical thinking skills regarding phenomena, processes, and spatial patterns, as well as their ability to make informed judgments about evolving environments and understand the impact of values on the environment(MoE, Citation2022b). It emphasizes the application of social studies knowledge in daily life and fosters a deeper understanding of societal dynamics and environmental stewardship. This underscores the importance of social studies in preparing students for the 21st century, equipping them with essential skills for a diverse workforce and responsible citizenship (Kwegyiriba et al., Citation2021). However, teachers often deviate from the conceptual ideals of the constructivist approach in their practical implementation, as noted by Sarbah (Citation2020). In many developing countries, including Ethiopia, the teaching methods utilized in social studies classes are inadequate for facilitating students’ learning of issues relevant and applicable to their real lives. For instance, Ayerteye et al. (Citation2019) revealed that numerous social studies teachers in Ghana fail to utilize fundamental materials and methods, resulting in learners missing out on both in-class and extracurricular activities such as field trips and project work. This issue is also widespread in the Ethiopian education system; many teachers, including those in social studies, predominantly convey ample information and numerous facts to students without employing more interactive teaching methods (Dejene et al., Citation2018; MoE, Citation2018b).

The significance of constructivist teaching and learning has been consistently underscored by international scholars of Ayaz and Sekerci (Citation2015) and Brame (Citation2017), as well as by Ethiopian experts and regional policy documents, guidelines, and strategies. Notably, educational policy documents MoE (Citation2023) advocate for the enhanced application of the constructivist teaching approach in classroom instruction. The latest education and training policy underscores the importance of teachers employing efficient teaching methods to engage students actively in teaching and learning. This policy introduces various strategies for implementing innovative reforms to enhance teacher effectiveness, addressing concerns related to learners’ capabilities (MoE, Citation2023). Inspired by the notion that teachers should foster effective methods encouraging problem-solving and the creation of enduring knowledge in the teaching and learning process, the policy seeks to shape teachers’ perspectives. Nevertheless, a challenge persists as many teachers rely on test-taking strategies that promote rote learning, influenced by the emphasis placed on passing both classroom and national examinations (MoE, Citation2022a).

Global research attempted to identify obstacles to the successful implementation of constructivist teaching. For example, Rosenfeld and Rosenfeld (Citation2006) identified administrative support, teacher exchange ideas, curriculum material availability, and professional development as factors that influence CTLA implementation, either directly or indirectly. Krahenbuhl (Citation2016), reported that students’ autonomy, involvement in the teaching process, and previous experience with CTLA all influence its adoption. Similarly, Cook et al. (Citation2002) found that the difference between theory and practice in CTLA teacher training programs influences in-service teachers’ classroom practices.

Recent local research indicates that a significant portion of teachers hold a favorable view of CTLA and understand its principles (Dagnew, Citation2017; Melesse & Jirata, Citation2016; Tadesse et al., Citation2022). However, the available local empirical data suggests that the constructivist approach is not widely adopted by teachers in the teaching-learning process. Research conducted by Melesse and Jirata (Citation2016) and Dagnew (Citation2017) found that a considerable proportion of teachers tend to rely on traditional teaching methods. These studies identified obstacles that impede the successful implementation of constructivist teaching, such as teachers’ insufficient commitment, large class sizes, limited time for active learning, educators’ lack of proficiency in constructivist teaching strategies, and a shortage of educational materials.

The annual assessment report from the West Gojjam Education Bureau in Bureau (Citation2022) emphasized that the majority of teachers primarily concentrate on delivering knowledge and skills to students. The national survey, commissioned by the Ministry of Education in 2018 to develop a roadmap for the Ethiopian education system, highlighted a deficiency in teachers’ proficiency in integrating knowledge, skills, and values. The prevailing approach observed in classroom teaching and learning situations at all levels of schooling relies heavily on traditional pedagogies, including lecturing and, to some extent, group work (MoE, Citation2018a).

Many teachers did not actively employ constructivist methods and did not assume roles as facilitators, organizers, and consultants in guiding students’ learning. Most prior research has focused more on secondary and tertiary levels of education, with limited exploration of the status of active and constructive learning in Ethiopian middle schools. Previous studies also did not investigate deeply the challenges faced by social study teachers in implementing the CTLA at the middle school level and did not examine the impact of teachers’ teaching experience on the challenges faced during classroom instruction. The previous studies often examined the old curriculum.

Hence, the objective of this research is to identify the main difficulties encountered by middle-level school social studies teachers in West Gojjam, Ethiopia, about the new curriculum. Additionally, the study investigates how teachers’ teaching experience influences the challenges faced in implementing constructivist teaching practices. This study intends to answer the following research questions:

Q1. What are the significant challenges faced by teachers while practicing the CTLA social studies education?

2. Q2. Does the level of teaching experience, categorized as > 5 years, 5-10 years11-15 years16-20 years, and more than 20 years, have a statistically significant impact on the challenges encountered by social studies teachers when implementing CTLA?

Definitions of key terms

The constructivist teaching-learning approach involves: It refers to students actively constructing knowledge from their experiences through practices such as group work, projects, role-playing, field trips, discussions, and problem-solving activities.

Practices of constructivist teaching approach: - is about the actual activities and engagements that social studies teachers have with the constructivist teaching component in the classroom.

Challenges of the constructivist teaching approach:- these are factors that hinder the implementation of the constructivist learning approach in social studies education.

Years of teaching experience: It indicates the length of time that social studies teachers revealed having taught in middle-level schools during the data collection period. Participants in this study were tasked with indicating their teaching experience by choosing from the provided categories: "less than 5 years (beginner teachers)," "5-10 years (junior teachers)," "11-15 years (senior teachers," "16-20 years associate teachers)," and "more than 20 years (leader teachers).

Research design

The study aimed to identify the primary challenges of middle-level school social studies teachers when implementing CTLA. Survey research design was employed to achieve this study objective. This approach is essential for assessing the difficulties these teachers encounter in the teaching-learning process.

Sample size and sampling techniques

The study utilized a multistage sampling approach to gather survey data. This method involves selecting samples from a population using progressively smaller groups (units) at each stage, commonly employed for data collection from large, geographically dispersed groups (Sedgwick, Citation2015). First, the sample districts were chosen from the West Gojjam Administrative Zone. Six districts were randomly selected from the sixteen existing within this zone. Next, schools were selected from these districts found.

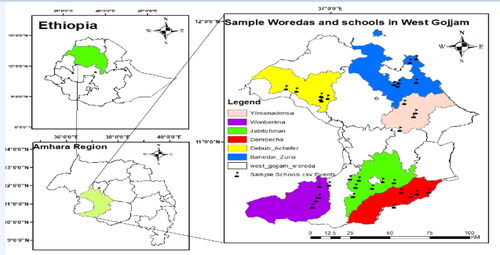

There are 235 middle-level schools within these six districts, and 36 schools, constituting 15% of the total, were selected using proportional random sampling due to unequal school numbers in the districts (refer to ). Following this, all teachers employed in the 36 selected schools (totaling 215) were deemed eligible for participation in the study using the most comprehensive available sampling method. However, only 178 teachers responded accurately to and returned the questionnaire, yielding an acceptable questionnaire return rate of 82.8% (Holtom et al., Citation2022).

Figure 1. Sample woredas and schools.

The above graphic representation illustrates the geographical coordinates of West Gojjam Sample woreda and the strategic placement of sample schools within the study area, providing a visual reference for the locations under investigation.

For the qualitative phase of the study, the maximum variation sampling method was employed. Maximum variation sampling is a purposive sampling technique used in qualitative research to collect a diverse range of points of view and experiences within a study. The goal is to find and select cases that represent the extremes of the dimensions of interest (Creswell, Citation2014). In this study, the sampling involved selecting social studies teachers with diverse characteristics, substantial teaching experience, and balanced representation of genders, as well as rural and urban settings. Eight teachers who met these criteria and were willing to participate in classroom observations were chosen for the qualitative case study.

Data collection tools

The study aims to investigate the main challenges teachers face when implementing a constructivist approach to teaching and learning. The research used quantitative and qualitative data-gathering methods: surveys and interviews.

Questionnaire: This is used to gather data from social studies educators about the challenges they face when adopting the constructivist approach.

The questionnaire consisted of 20 Likert-type statements, with five response options ranging from "Not Very Serious" (1) to "Extremely Serious" (5). The survey questionnaires were derived from literature studies by (Dagnew, Citation2017; Degago & Kaino, Citation2015; Melesse & Jirata, Citation2016; Moskal et al., Citation2016).

Interview: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with social studies teachers to obtain insights into the factors influencing the implementation of constructivist teaching and learning. The questions were designed to explore the obstacles to the engagement of CTLA, and the study used a semi-structured format with six specific items.

Classroom Observation: In this study, a non-participant observation was employed. The researchers investigate the factors influencing the implementation of the constructivist teaching and learning approach in social studies education. The researchers investigate the factors influencing the implementation of the constructivist teaching and learning approach in social studies education. The observation guide encompassed various aspects, including challenges related to teaching resources, the nature (environment) of the classroom, assessment techniques, teaching and learning methods, and the roles of teachers and students.

In two rounds of observations over eight weeks, each participant teacher observed twice to identify challenges in constructivist practices. Detailed notes were taken on teachers’ approaches to student information acquisition, assessment techniques, available learning resources, and the roles of both teachers and students. Subsequently, the researchers compiled their observations based on the observation guide. Finally, they collectively identified the main challenges related to institutional factors, teachers, and students.

Data analysis

A combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies was applied to analyze the data. The research explored the challenges hindering the adoption of CTLA among social studies teachers. The quantitative analysis involved the use of descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, and percentage, along with inferential statistics such as the one-sample t-test and one-way ANOVA to quantitatively examine the challenges. On the contrary, qualitative data from interviews were analyzed thematically.

Results findings

Major challenges of implementing the constructivist teaching-learning approach

The purpose of this study was to investigate the significant challenges that teachers encountered when implementing the CTLA. A total of 21 items were gathered and examined to identify the significant problems that impede the application of the constructivist teaching style.

These items included nine questions about institutional factors, five questions concerning teachers, and seven about students. However, during the data screening phase, one item from the institutional factors category was removed because it had the lowest communality value (0.235) and the lowest loading (0.298) on its respective dimension. According to Field (Citation2013) factor loading, values less than 0.4 are not acceptable. The analysis involved aggregating the total number of respondents who rated 1 (not extremely serious) and 2 (not serious), indicating the absence of significant challenges, and the total number of respondents who rated 5 (extremely serious) and 4 (very serious), indicating the presence of the most significant challenges.

Furthermore, a one-sample t-test was utilized to determine whether the mean obtained for any subscale showed a statistically significant deviation from the expected mean (3.0). Each item presented the observed and predicted mean values of social studies teachers to identify any notable variations. The significant challenge is implied if the grand mean exceeds the predicted mean; the least significant challenge is implied if the grand mean drops below the expected mean. The objective of the study was achieved by collecting data from teachers, learners, and institutions. The subsequent quantitative analysis focused on each of the variables outlined below.

Institution related challenges

The survey for teachers consisted of nine items designed to evaluate the factors that might impact their adoption of a constructivist approach to teaching in their specific context. As shown in , institutional factors are identified as causing hindrances to the proper implementation of the CTLAs. For instance, 61.3% of the responding teachers indicated a lack of learning resources (syllabus, teacher’s guide textbooks, etc.) as their most significant challenge.

Table 1. Challenges faced by institutions in implementing CTLA.

The observed mean of this item was greater than the expected mean (3.70 > 3.00), which indicates that the item is a significant challenge. Around 62.9% of the responding teachers also confirmed that the absence of workshops and training programs is a significant challenge that affected the implementation of CTLA.

The observed mean for this was also higher than the expected mean (3.59 > 3.00), stipulating that the item is a significant challenge. Another 56.2% of respondent teachers revealed that the lack of school commitment is a significant challenge to CTLA implementation.

Correspondingly, an observed mean greater than the expected mean (3.52 > 3.00) showed that the item is a significant challenge. Some 52.2% of the responding teachers agreed again that the lack of shared exchange of teaching strategies and experiences among teachers poses the most significant challenge affecting the implementation of the CTLA.

The data in shows likewise that 31.5% of the responding teachers affirmed the teaching methods recommended in the new social study curriculum are more content-oriented and pose a significant challenge to the implementation of CTLA. However, an observed mean less than the expected mean (2.91 < 3.00) indicated that the nature of the new textbook curriculum does not pose a significant challenge and influenced classroom instructions. Moreover, the above table shows the suggested teaching method in the updated curriculum, the allocated time for content coverage, and the classroom environment’s nature were not major obstacles to implementing CTLA.

Teacher related challenges

shows the teacher-related challenges encountered during the implementation of CTLA in social study education. In this regard, 58.4% of the studied teachers reported that the lack of devotion taking proper training CTLA during teacher education college and in-services training programs has hampered its proper implementation in social study classrooms. The corresponding observed mean for this variable was found to be higher than the expected mean (3.60 > 3.00), indicating that the variable is significant. From the data in , it is checked that 60.1% of the responding teachers agreed the lack of teacher commitment to implement the CTLA in teaching is the most significant challenge in the study areas.

Table 2. Challenges related to teachers in CTLA implementation.

The observed mean is greater than the expected mean (3.57 > 3.00) indicating that lack of teacher commitment is a significant challenge to implement the CTLA in the social-study classrooms. Another group of teachers (53.3%) revealed lack of teacher pedagogical preference has posed a significant challenge to implement the CTLA in the social study classrooms. The observed mean for this variable appears greater than the expected one (3.38 > 3.00) lack of pedagogical preference is a significant challenge in social studies education. In another context, the lack of prepared teaching materials and use of facilities resources teachers is identified as being among the most significant barriers to applying the CTLA by more than 40.5% of the teachers. The observed mean consistently outperformed the predicted mean (3.30 > 3.00), suggesting that the lack of prepared teaching materials and use of facilities resources teachers is a major difficulty in CTLA practice. Contrary to the above-mentioned challenges, confidentiality on the mastery of the subject matter is calculated not a serious problem. The grand mean of this variable was found to be lower than the projected mean (2.89 < 3.00), demonstrating that the item subject matter mastery does not pose a significant barrier to the strategy ().

Student related challenges

As can be demonstrated in , the lack of adequate background in CTLA on the part of the students is identified by 60.6% of the participating teachers as a significant factor impacting the execution of the CTLA. The observed mean for this variable is greater than the anticipated average (3.83 > 3.00), indicating that the background of students in the desired lecture note has substantially impacted the CTLA application.

Table 3. Challenges related to students in CTLA implementation.

About 56.2% of the respondent teachers also confirmed that a lack of desire to learn cooperatively on the part of the students is posing a serious challenge. The corresponding observed mean of this variable outscored the expected mean (3.76 > 3.00) affirming that the lack of lack of willingness to learn cooperatively on CTLA is a significant challenge to implement in the classroom.

The data in shows likewise 57.3% and 48.8% of the respondents affirmed that students’ pedagogical preference and lack of courage to take responsibility for learning are the significant challenges in the implementation of classroom instruction respectively. Correspondingly, observed means of students’ pedagogical preference and lack of courage to take responsibility for learning greater than the expected mean (3.61 > 3.00) and (3.47 > 3.00) respectively, showed that the items are significant challenges in the implementation of CTLA.

In contrast to the above-discussed issues, students’ relations with teachers, peer relationships, and the number of students implementing CTLA were found to have lower observed averages compared to the expected mean scores (2.85 < 3.00, 2.53 < 3.00 and2.52 < 3.00), respectively). This suggests that these variables could not pose a significant challenge to the CTLA in classroom implementation.

Presentation and analysis of data obtained through observation and interview

The study intended to answer the question, "What are the major challenges social studies teachers’ faces when implementing a constructivist teaching approach?"

To address this question, teachers responded to semi-structured interviews. As a consequence of the inquiry, five themes emerged regarding teachers who had challenges using a constructivist teaching method. These included issues for the institution, teachers, students, parents, and the curriculum.

Challenges related to the institution

As depicted in , sex out of eight participants, fell into this particular group. Within this category, the primary obstacles encountered by teachers employing constructivist pedagogy included insufficient resources such as textbooks, teacher guides, and syllabi. The challenges also encompassed the school’s rigorous assessment methods and schedule, a lack of ongoing pedagogical training related to the new curriculum, limited engagement in continuous professional development, wastage of learning days, and prioritization by the principal of student enrollment quantity over the quality of the learning process were identified as the most influencing factors affecting the implementation of the constructivist approach related to the institution.

Table 4. Participants’ responses to challenges encountered in the practice of CTLA.

Regarding unused time learning days, seven out of eight participants’ teachers pointed out their school (institution) experience as follows. There are just three periods of social studies education every week. Schools spent no more than eight months of the academic year teaching and learning activities for a total of 96 periods for this subject. However, six tests, two final exams, cultural holidays, and several periods of more than 30 were unused. It suggested that just 44 hours, or less than two days out of 365 days a year, were available for using teaching and learning approaches in social studies education, limiting CTLA implementation.

In alignment with the previously mentioned points, a participant articulated the following obstacles to the implementation of CTLA:

I took pedagogical training in the CPD (Continuous Professional Development) course years ago and have not received any further training since then. I am currently updating my knowledge independently, which is not ideal. It is essential to have training at least every year, given the dynamic nature of changes in the 21st century.

The school has established a predetermined timetable for assessing teaching and learning. Each term includes three written tests and two final exams at the end of the semester. The school principals oversee the administration of these tests according to the school schedule and closely supervise teachers to guarantee the inclusion of topics from the textbook. Consequently, because I am worried about covering all of the subjects in the textbook, I favor the traditional approach to teaching over the active constructionist method.

The study finding suggests that teachers need essential prerequisites, such as comprehensive training on 21st-century CTLA pedagogy methods of teaching, assessment techniques, and its principles.

Challenges related to teachers

As illustrated in , five out of the eight teachers participating in the interview fell into this category. This group perceives that the primary challenges encountered by teachers in implementing constructivist pedagogy emanate from their inclination to lecture as a convenient means of presenting a significant amount of information to students.

Another obstacle affecting the adoption of CTLA among these teachers is their fear of not covering the curriculum and a lack of commitment. These teachers frequently prefer lectures due to concerns about ensuring comprehensive coverage of the course content. They are reluctant to embrace active learning methods, fearing that these methods may not adequately address all the required material. Regarding this matter, one teacher articulated:

I prefer to choose lectures frequently due to concerns about ensuring comprehensive coverage of the course content. There is a reluctance to embrace active learning methods, driven by the fear that these methods may not adequately address all the required material.

In general, teachers generally adopt an isolated approach to teaching, engaging in limited interaction with their colleagues. Teaching is perceived as an individual effort, which leads to a lack of a collaborative culture where ideas and experiences are shared. This absence of collaboration negatively impacts the implementation of CTLA.

Challenges related to students

As depicted in the above, seven out of the eight teachers engaged in the interview perceived that challenges associated with students constituted the main hindrance to the practice of CTLA. These teachers perceived that the main difficulties faced by social studies teachers in implementing CTLA were linked to student tendencies, such as heavy reliance on lecture notes and the perception of teachers as the sole sources of knowledge. Consequently, this led to students expecting everything from the teachers. Another challenge that affected the implementation of CTLA among students was the prevalent perception that a good teacher should provide concise and clear notes and consider classroom group work as a waste of time activities. There was also a general reluctance among students to take responsibility for their learning.

In confirmation of the earlier point, a participant articulated the following:

Students seem to have a misconception that student-centered learning (the constructivist teaching and learning approach) is a waste of time. They believe that the teacher is merely trying to save their own time and energy by adopting such techniques. Students opine that a good teacher is the one who lectures for the entire class duration. They consider it a sign of a good teacher if the teacher regularly lectures.

The example above illustrates that students often rely on lecture notes rather than independently deriving meaning and concepts from the material. This behavior is reinforced by classroom observations, where teachers frequently wrote notes on the blackboard, and students’ main activity was copying these notes.

Challenges associated with parents

As shown in , three out of the eight participants interviewed are categorized under this heading. Within this subgroup, teachers recognize that the main obstacles encountered in implementing CTLA arise from parents’ preference for their children to achieve high scores in traditional paper and pencil tests.

This inclination has prompted teachers to adopt a more conventional approach rather than embracing the methods of constructivist teaching and learning.

Challenges related to the curriculum

It’s evident from the that four out of eight participants in the interview fall into a category that highlights the main challenges faced by teachers in implementing (CTLA) in the classroom. The challenges include: Teachers in this category perceived the difficulties in implementing CTLA due to a lack of awareness about the new curriculum or syllabus. This lack of knowledge may lead to misalignment between teaching practices and the updated educational guidelines. Participants noted that they hadn’t received proper training on the new curriculum. This lack of training hinders teachers’ ability to incorporate CTLA principles into their teaching methods. Some teachers in this group face the challenge of teaching subjects for which they have not received formal training.

For instance, teachers with degrees in history may find themselves teaching geography and vice versa. Those who graduated in history without taking geography courses might end up teaching social studies, which encompasses geography and history.

In line with the aforementioned, a participant expressed the following viewpoint:

I have been delivering lessons based on the new curriculum without formal training. This academic year, I am teaching seventh-grade social studies, which predominantly covers geography and history for grades 7 and 8. Despite my academic background in geography and environmental studies, I did not take any history courses in my teacher education. Nevertheless, I have been assigned to teach social studies, which includes both geography and history. To address the historical component, I rely on personal reading efforts and seek assistance from others. Consequently, I have encountered challenges in implementing a constructivist teaching and learning approach, especially in the history part of social studies.

Teaching experience and teachers’ views of CTLA practice

The study examined the influence of teachers’ years of experience on their faced challenges in CTLA practice through a one-way analysis of variance between groups. Participants were divided into five groups according to their years of teaching experience: Group 1 (<5 years), Group 2 (5-10 years), Group 3 (11-15 years), Group 4 (16-20 years), and Group 5 (more than 20 years). Using a one-way ANOVA between groups, the researchers investigated how teachers’ years of experience influence the challenges they confront when applying CTLA.

shows that challenges related to students and teacher related challenges were significant when all three variables were treated as dependent variables, with teaching experience as the independent variable (F(4,173) = 4.279, P < 0.05, and F(4,173) = 3.858, P < 0.05), respectively. On the other hand, there was no significant difference in obstacles associated with CTLA implementation across teachers’ years of experience (F(4,173) = 0.329, P > 0.05). Following the completion of the ANOVA test and the identification of significant differences among the compared groups, a Post Hoc analysis of the F-test was performed to determine which groups exhibited notable distinctions.

Table 5. Mean, Standard Deviation, one-way ANOVA, and t-test results of variables.

The findings of the Post Hoc analysis regarding challenges associated with students and those related to teachers, categorized by teachers’ years of teaching experience, are summarized in . Each participant group was compared to the remaining groups, with differences in group means and corresponding p-values provided for each comparison. The post-hoc test results revealed that teachers with 11–15 years of experience face significantly more teacher-related challenges compared to those with 16–20 years of experience. However, there is no significant difference in teacher-related challenges between teachers with 11–15 years of experience and other group-experienced teachers. The posthoc test results also revealed teachers with 11–15 years of experience perceived significantly fewer student-related challenges than those with below 5 years of experience. However, there is no significant difference in student-related challenges between teachers with 11–15 years of experience and other group-experienced teachers.

Table 6. Results of a post-hoc test on challenges for teachers and students based on teaching experiences.

Discussion

The primary objective of this research was to identify the significant obstacles encountered by middle-level social studies teachers while incorporating constructivist teaching and learning approaches in middle school social studies classrooms. Additionally, the study aimed to assess whether there were noteworthy variations in the challenges experienced by teachers depending on their level of teaching experience. To fulfill the primary objective two specific research questions were formulated. The subsequent section provides an analysis of the findings related to these two research questions.

The first question was designed to highlight the key challenges that social studies teachers encounter when implementing CTLA. Participants in this investigation revealed that impediments to CTLA implementation arise from various factors, encompassing issues with the institution (school administration), students, parents, and curriculum policy. Participants in the quantitative analysis identified several obstacles to the utilization of CTLA in social studies classrooms. Among these challenges were the absence of CTLA workshops and training, the scarcity of educational materials, and the inadequate dedication of the institution.

The mean scores for these challenges were substantially higher than the predicted mean of 3.00, indicating that the ability of teachers to apply CTLA is severely hampered by these institutional challenges. The quantitative findings concerning institutional concerns are consistent with the interview responses, with six out of eight participants considering these challenges as impeding the implementation of CTLA in social studies instruction. Based on interviews, it was found that the primary challenges faced by teachers implementing constructivist pedagogy were a lack of essential materials, including teacher guides, textbooks, and syllabi, in addition to a lack of understanding and preparation surrounding the new curriculum. The findings of this study indicated that the institution(s) did not create a favorable environment for the application of CTLA in social studies education in middle-level schools. The mentioned findings are consistent with previous studies (Ahmad et al., Citation2021; Amare, Citation2019; Corkin et al., Citation2017; Dagnew, Citation2017; Prawat, Citation1992), which also found that insufficient teaching materials and training negatively impact classroom teaching and learning. This also corresponds with prior research by Rosenfeld and Rosenfeld (Citation2006), which highlighted that limited participation in professional development activities hinders teachers’ acquisition of new skills for effective teaching.

Interview participants revealed that unused periods lost due to tests, exams, and holidays, affect significantly hindered the implementation of CTLA in social studies education. The findings are consistent with previous studies by Nyamekye et al. (Citation2023), who found limited resources and time constraints affect the implementation of pedagogy. The results of this study informed us that education quality can potentially reached and improved by focusing more on teaching materials as well as making more effective use of academic time for classroom instruction. Furthermore, the classroom observations confirmed the quantitative and interview findings that teachers encountered difficulties due to a lack of learning materials and a failure to use instructional materials. These issues have subsequently impacted the quality of their classroom instruction. The aforementioned finding is also consistent with previous studies by Takele (Citation2020) who found that inadequate teaching and learning materials influence the implementation of constructivist teaching strategies.

Concerning challenges faced by social studies teachers, the quantitative analysis identified a lack of teacher commitment to practicing CTLA, a lack of devotion to having taken proper training in Teacher College, issues with in-service training programs, teachers’ pedagogical preference and a lack of prepared teaching materials as primary challenges affecting the implementation of CTLA. The mean scores for these issue items surpassed the hypothesized mean of 3.00, indicating that these challenges sourced from teachers themselves significantly affect teachers’ ability to implement CTLA in social studies classrooms. The quantitative findings resonate with the interview responses, where five out of eight participants perceived that teacher-related challenges affect the implementation of CTLA. The outcomes of participant interviews revealed that the primary challenges faced by teachers stemmed from their tendency to rely on lecturing as a convenient method for presenting substantial information to students affecting the implementation of CTLA. Moreover, concerns were raised about the fear of not being able to cover the curriculum and a lack of commitment to practicing CTLA. This outcome is consistent with a prior study by Letina (Citation2022), which identified teachers’ inclination toward the traditional/lecture method as a significant factor affecting effective classroom instruction.

The mentioned finding also aligns with a previous study by Essien et al. (Citation2016) which concluded that less participation and absence of participate in-service training, workshops, and seminars hampers teachers in acquiring new knowledge and skills for their day-to-day activities in social studies education.

Classroom observation supported the quantitative data and interview findings, demonstrating that teachers did not promote or encourage students throughout classroom instruction. Teachers primarily wrote notes on the chalkboard, while students copied these notes into their exercise books. Group work was attempted, although it was short in duration and led by the teachers.

These observations show that teacher-related factors impede the adoption of (CTLA) in social studies teaching and learning. However, this finding is inconsistent with (Von Glasersfeld, Citation2012) who advocated that teachers need to facilitate, support, and scaffold students’ learning.

This finding demonstrated that teachers were neglecting their pedagogical responsibilities, failing to adequately encourage, support, and facilitate students in the teaching and learning process. This oversight underscored a crucial gap in effective educational practices, highlighting the need for teachers to actively engage in fostering a conducive learning environment where students can thrive and grow academically.

The survey data highlighted student-related challenges affecting the implementation of CTLA in social studies. These challenges include students’ limited background in CTLA, their pedagogical preferences, reluctance to learn cooperatively, and lack of initiative in taking responsibility for their learning. The mean scores for these issues, which exceed the hypothesized mean of 3.00, indicate significant obstacles for teachers. Similarly, findings from participant interviews and classroom observations revealed that the primary difficulties faced by social studies teachers in implementing CTLA were associated with student behaviors, such as relying on lecture notes and perceiving teachers as the sole sources of knowledge. This finding aligns with a prior study by Telore and Damtew (Citation2023), which identified students’ preferences for learning styles and their perception of teachers as significant challenges affecting the implementation of CTLA.

The study identified challenges related to parents and the curriculum that hinder the implementation of CTLA among social studies teachers. During interviews, participants mentioned that parental expectations for high exam results through traditional paper and pencil testing exert pressure on teachers, leading to reluctance to adopt CTLA in their instruction. Furthermore, the lack of training and awareness regarding the new curriculum in social studies also poses challenges to the effective implementation of CTLA. Some respondents highlighted receiving inadequate coursework during their teacher training. For example, a few participants mentioned not having taken any history courses during their Teacher Education College. However, despite this, they were assigned to teach social studies, which includes Geography and History. This mismatch impacts their ability to effectively implement CTLA. On the other hand, a study conducted by Orchard and Winch (Citation2015) found that for teachers to deliver effective teaching, they need to have adequate knowledge and training in the subject matter they teach.

The second research question aims to determine whether there is a statistically significant variation in the challenges experienced by social studies teachers depending on their teaching experience. The findings indicated a statistically significant difference in challenges related to both the students and the teachers related challenges when all three variables were considered as dependent variables and teaching experience was considered as the independent variable F(4,173) = 4.279, P < 0.05, and F(4,173) = 3.858, P < 0.05), respectively. The Post hoc test findings demonstrated considerable variances in teacher insight regarding the problems involved with CTLA practice. Teachers with 11-15 years of teaching experience perceived more significantly teacher-related challenges than those with 16-20 years of experience teachers. In addition, the post-hoc analysis found significant differences in student-related challenges between teachers with 11-15 years of teaching experience and those with less than 5 years of teaching experience. Teachers with 11-15 years’ experience perceived fewer student-related challenges to implementing CTLA in social studies classrooms. This result is in line with a prior study by Makoa and Segalo (Citation2021), which found that novice (beginner) teachers faced more challenges originating from themselves than groups of teachers. The result is also consistent with earlier studies by O'connor and Fish (Citation1998), who found that novice teachers had significantly lower levels of classroom flexibility and practiced a more limited range of functions compared to more experienced teachers .This result indicated that novice teachers, due to being new to the school environment, teaching and learning practices, and having less experience in understanding students’ backgrounds and socioeconomic contexts, perceived more challenges in implementing CTLA compared middle-experienced and highly experienced teachers.

Conclusion

Despite the issue of the constructivist teaching and learning approach being vividly addressed in the Ethiopian middle-level education social studies curricula Teferra et al. (Citation2018), the implementation of this approach by social study teachers is insufficient.

The conventional teaching-learning process is more prevalent than the constructivist approach, leading to a misalignment with the new education policy and the social studies curriculum framework (MoE, Citation2023). Teachers stray from employing the constructivist teaching and learning approach due to obstacles associated with institutional policies, the teachers themselves, the students, the parents, and the curriculum, which impedes the proper application of CTLA. Regarding teachers’ years of experience, teachers who have been teaching for 11-15 years noticed significant disparities in challenges related to students that have a greater impact on the practice of the constructivist approach to teaching and learning compared to teachers with 5-10 years of experience.

The limited utilization of CTLA techniques indicates a prevailing preference among teachers for the traditional concept-based approach, potentially resulting in various challenges. Since the findings are confined to social study teachers (grades 7-8), their applicability to other teacher groups and variables is limited. Consequently, further research is necessary to explore teachers’ perceptions and practices of CTLA and the relationship between the implementation of CTLA components and various teacher characteristics.

Study limitations

This study has highlighted the obstacles faced in implementing the constructivist approach to teaching and learning in middle-level schools in Ethiopia. However, the research’s scope was restricted to only middle school social studies teachers from a single administrative zone in the Amhara region of Ethiopia. Therefore, the findings of this study are specific to the West Gojjam administrative zone and may not be generalizable to other parts of the country. Furthermore, this study did not involve other significant stakeholders, such as school administrators and experts, which limited the depth of investigation into the challenges associated with adopting the constructivist approach in social studies.

Additionally, the research did not take into account influential factors, such as teacher job satisfaction, which could potentially impact the adoption of the constructivist approach in social studies classrooms.

Authors’ contributions

Solomon Tsehay, a DEd (Doctor of Education) student at Bahir Dar University in Ethiopia, identified research gaps, collected and evaluated data, and created a literature review. Mehretie Belay advised on the whole effort, particularly the analysis, and reviewed and helped to produce the manuscript. Amera Seifu assessed both the study’s instrument and the article. Mehretie Belay and Amera Seifu advised Solomon Tsehay on his DEd studies. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

The availability of data and materials

Upon a reasonable request, the corresponding author will release the datasets used or analyzed in the current study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Solomon Tsehay

Solomon Tsehay, a Doctor of Education candidate in Geography and Environmental Studies Education at Bahir Dar University in Ethiopia, has more than 25 years of teaching experience in middle and secondary schools, as well as considerable involvement in teacher college education. He conducts applied and action research at teaching colleges and primary schools.

Mehretie Belay

Mehretie Belay, an Associate Professor of Geography at Bahir Dar University in Ethiopia, has years of teaching experience and made substantial scholarly contributions, particularly in geography, environmental challenges, and education (has over 20 publications). He wants to improve his research and consulting skills.

Amera Seifu

Amera Seifu, a Professor of Curriculum and Instruction at Bahir Dar University, has extensive teaching and research expertise, with publications covering education, curriculum, reflection, and instructional design.

References

- Ackermann, E. K. (2004). Constructing knowledge and transforming the world. In M. Tokoro, & L. Steels (Eds.), A learning zone of one’s own: Sharing representations and flow in collaborative learning environments (Part 1, Chapt 2. pp. 15–37). Amsterdam, Berlin, Oxford, Tokyo, Washington, DC: IOS Press.

- Ahmad, A., Khan, I., Ali, A., Islam, T., & Saeed, N. (2021). Implementation of constructivist approach in teaching English grammar in primary schools. Ilkogretim Online, 20(5), 2803–2813.

- Akpan, J. P., & Beard, L. A. (2016). Using constructivist teaching strategies to enhance academic outcomes of students with special needs. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(2), 392–398. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2016.040211

- Alexander, J. O. (1999). Collaborative design, constructivist learning, information technology immersion, & electronic communities: a case study. Interpersonal Computing and Technology: An Electronic Journal for the 21st Century, 7(1–2), 1–28.

- Amare, Y. (2019). Perceptions, practices and challenges of active learning strategies utilization at Yilimana Densa Woreda Secondary teachers’ schools [MSc Thesis Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia] (Unpublished master's thesis).

- Applefield, J. M., Huber, R., & Moallem, M. (2000). Constructivism in theory and practice: Toward a better understanding. The High School Journal, 84(2), 35–53.

- Ayaz, M. F., & Sekerci, H. (2015). The effects of the constructivist learning approach on student’s academic achievement: a meta-analysis study. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 14(4), 143–156.

- Ayerteye, E. A., Kpeyibor, P. F., & Boye-Laryea, J. L. (2019). Examining the use of Teaching and Learning Materials (TLM) methods in basic school level by socials studies teachers in Ghana: A tracer study. Journal of African Studies and Ethnographic Research, 1(1), 54–65.

- Bada, S. O., & Olusegun, S. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 5(6), 66–70.

- Brame, C. J. (2017). Effective educational videos: Principles and guidelines for maximizing student learning from video content. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(4), es6. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125

- Bureau, W. G. E. (2022). West Gojjam zone educational official report West Gojjam Zone Educational Bureau.

- Carlson, J. S., & Wiedl, K. H. (2013). Cognitive education: Constructivist perspectives on schooling, assessment, and clinical applications. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 12(1), 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.12.1.6

- Charmaz, K. (2020). “With constructivist grounded theory you can’t hide”: Social justice research and critical inquiry in the public sphere. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(2), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419879081

- Cook, L. S., Smagorinsky, P., Fry, P. G., Konopak, B., & Moore, C. (2002). Problems in developing a constructivist approach to teaching: One teacher’s transition from teacher preparation to teaching. The Elementary School Journal, 102(5), 389–413. https://doi.org/10.1086/499710

- Corkin, D. M., Ekmekci, A., & Coleman, S. L. (2017). Barriers to implementation of constructivist teaching in a high-poverty urban school district. Engage, Explore, and Energize Mathematics Learning, 57–64.

- Creswell, J. D. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.), Sage Publications Ltd.

- Dagnew, A. (2017). The practice and challenges of constructivist teaching approach in Dangila district second cycle primary schools, Ethiopia. British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural Science, 19(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJESBS/2017/30827

- Degago, A. T., & Kaino, L. M. (2015). Towards student-centred conceptions of teaching: the case of four Ethiopian universities. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(5), 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1020779

- Dejene, W., Bishaw, A., & Dagnaw, A. (2018). Pre-service teachers’ conceptions of teaching and learning and their teaching approach preference: Secondary teacher education in focus. Bahir Dar Journal of Education, 18(2), 174–193.

- Devi, K. S. (2019). Constructivist approach to learning based on the concepts of Jean Piaget and lev Vygotsky. The NCERT and no matter may be reproduced in any form without the prior permission of the NCERT. Journal of Indian Education, 44(4), 5–19.

- Dewey, J. (1958). Experience and nature (Vol. 471). Courier Corporation.

- Essien, E. E., Akpan, O. E., & Obot, I. M. (2016). The influence of in-service training, seminars and workshops attendance by social studies teachers on academic performance of students in junior secondary schools in Cross River State. Nigeria. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(22), 31–35.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage.

- Gordon, M. (2009). Toward a pragmatic discourse of constructivism: Reflections on lessons from practice. Educational Studies, 45(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131940802546894

- Gray, C., & MacBlain, S. (2015). Learning theories in childhood. Sage.

- Hein, G. E. (1991). Constructivist learning theory. Institute for Inquiry. http://www.exploratorium.edu/ifi/resources/constructivistlearning.htmls.

- Holtom, B., Baruch, Y., Aguinis, H., & A Ballinger, G. (2022). Survey response rates: Trends and a validity assessment framework. Human Relations, 75(8), 1560–1584. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211070769

- Honebein, P. C. (1996). Seven goals for the design of constructivist learning environments. In B. G. Wilson (Ed.), Constructivist learning environments: Case studies in instructional design (pp. 11–24). Educational Technology Publications.

- Krahenbuhl, K. S. (2016). Student-centered education and constructivism: Challenges, concerns, and clarity for teachers. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 89(3), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2016.1191311

- Kwegyiriba, A., Awudja, J. C., & Babah, P. A. (2021). Pedagogical approaches in the social studies instructional process in western region colleges of education. Ghana. Journal of Educational & Psychological Research, 3(1), 234–239.

- Letina, A. (2022). Teachers’ epistemological beliefs and inclination towards traditional or constructivist teaching. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 8(1), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijres.1717

- Makoa, M. M., & Segalo, L. J. (2021). Novice teachers’ experiences of challenges of their professional development. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 15(10), 930–942.

- Mbise, S., & Lekule, C. (2023). Strategies for promoting the practice of constructivist teaching and learning process in Tanzanian schools. East African Journal of Education Studies, 6(3), 226–240. https://doi.org/10.37284/eajes.6.3.1544

- Melesse, S., & Jirata, E. (2016). Teachers’ perception and practice of constructivist teaching approach: The case of secondary schools of Kamashi zone. Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal, 4(4), 194–199. https://doi.org/10.4314/star.v4i4.27

- MoE. (2018a). Ethiopian education development roadmap an integrated executive summary. Ministry of Education Education Strategy Center (ESC).

- MoE. (2018b). Ethiopian education development roadmap an integrated executive summary. Ministry of Education Education Strategy Center (ESC).

- MoE. (2022a). Ethiopian new curriculem grade 7 and 8 social studies education. Federa; Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

- MoE. (2022b). Middle level school (grade 7 – 8) social studies flowchart, minimum learning competencies and syllabus. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Education. Retrieved from Addis Ababa.

- MoE. (2023). Education and training policy yekatit. Addis Ababa.

- Moskal, A., Loke, S.-K., & Hung, N. (2016). Challenges implementing social constructivist learning approaches: The case of Pictation. ASCILITE Publications, 446–454. https://doi.org/10.14742/apubs.2016.805

- Nyamekye, E., Zengulaaru, J., & Nana Frimpong, A. C. (2023). Junior high schools teachers’ perceptions and practice of constructivism in Ghana: The paradox. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2281195. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2281195

- O'connor, E. A., & Fish, M. C. (1998). Differences in the classroom systems of expert and novice teachers. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA, Queens College of the City University of New York, USA.

- Orakcı, Ş. (2020). Paradigm shifts in 21st century teaching and learning. Information Science Reference.

- Orchard, J., & Winch, C. (2015). What training do teachers need?: Why theory is necessary to good teaching. Impact, 2015(22), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/2048-416X.2015.12002.x

- Pardjono, P. (2016). Active learning: The Dewey, Piaget, Vygotsky, and constructivist theory perspectives. Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan Universitas Negeri Malang, 9(3), 105376.

- Prawat, R. S. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning: A constructivist perspective. American Journal of Education, 100(3), 354–395. https://doi.org/10.1086/444021

- Rosenfeld, M., & Rosenfeld, S. (2006). Understanding teacher responses to constructivist learning environments: Challenges and resolutions. Science Education, 90(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20140

- Sarbah, B. K. (2020). RunnigHead: Constructivism learning approaches. Saint Paul's University. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28138.34241

- Sayed, Y., & Ahmed, R. (2015). Education quality, and teaching and learning in the post-2015 education agenda. International Journal of Educational Development, 40, 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.11.005

- Sedgwick, P. (2015). Multistage sampling. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 351, h4155. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4155

- Shah, R. K. (2019). Effective constructivist teaching learning in the classroom. Online Submission. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 7(4), 1–13.

- Spiel, C., Schwartzman, S., Busemeyer, M., Cloete, N., Drori, G., Lassnigg, L., Schober, B., Schweisfurth, M., & Verma, S. (2018). The contribution of education to social progress. In International Panel on Social Progress (Ed.), Rethinking Society for the 21st Century: Report of the International Panel for Social Progress (pp. 753–778). Cambridge University Press.

- Stauffacher, M., Walter, A. I., Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., & Scholz, R. W. (2006). Learning to research environmental problems from a functional socio‐cultural constructivism perspective: The transdisciplinary case study approach. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 7(3), 252–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370610677838

- Tadesse, T., Melese, W., Ferede, B., Getachew, K., & Asmamaw, A. (2022). Constructivist learning environments and forms of learning in Ethiopian public universities: testing factor structures and prediction models. Learning Environments Research, 25(1), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09351-4

- Takele, M. (2020). Practices and challenges of active learning methods in mathematics classes of upper primary schools. Journal of Education and Practice, 11(13), 26–40.

- Taylor, P. C., Fraser, B. J., & Fisher, D. L. (1997). Monitoring constructivist classroom learning environments. International Journal of Educational Research, 27(4), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(97)90011-2

- Teferra, T., Asgedom, A., Oumer, J., Dalelo, A., & Assefa, B. (2018). Ethiopian education development roadmap (2018-30). An integrated executive summary. Ministry of Education Strategy Center (ESC) Draft for Discussion: Addis Ababa.

- Telore, T., & Damtew, A. (2023). New challenges to the implementation of active learning methods at secondary schools in Kambata Tambaro zone, Ethiopia. JEES (Journal of English Educators Society), 8(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.21070/jees.v8i2.1773

- Triantafyllou, S. A. (2022a). Constructivist learning environments. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Advanced Research in Teaching and Education.

- Triantafyllou, S. A. (2022b). Game-Based Learning and interactive educational games for learners–an educational paradigm from Greece. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Modern Research in Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.33422/6th.icmrss

- Triantafyllou, S. A. (2024). A short paper about fundamental pedagogical concepts of constructivism theory in relation to TPACK framework. In: proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Research in Teaching and Education, 1(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.33422/icate.v1i1.1641.

- Von Glasersfeld, E. (2012). A constructivist approach to teaching. In Constructivism in education (pp. 3–15). Routledge.

- Vygotsky, L. S., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Zajda, J., & Zajda, J. (2021). Constructivist learning theory and creating effective learning environments. In Globalisation and education reforms: Creating effective learning environments (pp. 35–50) Springer.

- Zhu, X., Ennis, C. D., & Chen, A. (2011). Implementation challenges for a constructivist physical education curriculum. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 16(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408981003712802