Abstract

Competency-based assessment plays an important role in the development of learners’ education as it enables them to demonstrate their expertise and readiness for professional life. The competencies of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients in remote and underprivileged areas reflect the learning outcomes that teacher education institutions should achieve to meet the basic needs of community schools in these areas. The competency-based assessment model developed utilizes real-life scenarios from the teaching environment of community schools in remote and underprivileged areas to create simulations in which student teachers can apply their existing problem-solving skills. The aim of this study is to develop a competency-based assessment model for third-year student teachers in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program. The study found that the competency-based assessment model for these students consists of the following elements: (1) assessment of scholarship students’ competencies, with assessors taking on two interrelated roles: Coaching and Evaluation; (2) a simulated, situation-based competency-based assessment activity; and (3) data on student competencies along with individual development strategies. The quality assessment of this competency-based assessment model for the third-year students found it to be of the highest quality regarding authenticity, cognitive complexity, meaningfulness, directness, comparability, transparency, fairness, cost and benefit, educational consequences, and reproducibility of decisions.

1. Introduction

The rapid advances and changes in science and technology have led to growing inequalities in various areas. A difficult issue in education is the rapid and increasing spread of educational inequality, particularly in developing countries. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, Citation2018) has set a priority goal for the 21st century: to ensure well-being for all citizens, which is essentially based on equitable access to education. Therefore, education plays a central role in developing knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that enable citizens to actively participate in the development of their country and benefit from an inclusive and sustainable future. The concept of competency-based education (CBE) is aligns with the current changing situation, which should respond to the complex needs of society. Future-ready learners will need to have both foundational knowledge and specialized knowledge. The acquisition of knowledge has to go hand in hand with the ability to think in associative thinking, creative thinking and systematic thinking. Learners are able to use knowledge and understanding to foster thought processes such as critical thinking, creativity and self-regulation, as well as social and emotional skills such as empathy, self-efficacy, and collaboration (Clark & Estes, Citation1999; Hoogveld, Citation2003; Levine & Patrick, Citation2019; Niu et al., Citation2021; Schilling & Koetting, Citation2010).

The training and development of teachers to become highly qualified individuals is should be pursued seriously and continuously. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2560 (2017), emphasizes the development of the teaching profession and education reform through the enactment of national education laws, section 258 clause (3), which prescribes ‘having a mechanism and a system for producing, screening and developing teaching professionals and instructors to engender a spiritual mindset of being a teacher, to possess genuine knowledge and competence…’ (Office of the Constitutional Court, Citation2020). Darling-Hammond (Citation2017) and Elstad (Citation2023) show that teachers have a pedagogical responsibility in managing learning as creators of academic and professional excellence. Therefore, those who want to become teachers have to undergo teacher education training which focuses on the teaching profession and aims to make student teachers experts in learning management.

That is, student teachers need to develop their knowledge, teacher spirituality, and practical skills in an integrated way, based on real-life situations, in order to be able to design learning experiences that enhance their subject knowledge. Furthermore, teacher education is the starting point for successful professional practice of teachers in the context of the transition to a digital system, including societal expectations of teacher performance. Therefore, teacher preparation and development are critical components that impact teacher education. In developed countries, there is a system for producing teachers and promoting the profession that starts with the recruitment process for student teachers, the production of teachers, appointment and support for career advancement. Finland, for example, fully funds teacher training and students receive living expenses during their studies. Every student teacher receives a consistently high-quality education (Hansén et al., Citation2023).

In addition, Darling-Hammond (Citation2017) suggested the following strategies for teacher production: (1) recruiting student teachers with high ability, guaranteeing a salary, and providing subsidies for their education, as practiced in Finland and Singapore; (2) linking theoretical knowledge and practice through teacher education curricula, as in Finland, Canada, Australia, and the United States; (3) employing professional teaching standards to emphasize learning and assessment of knowledge, skills and important attributes; (4) continuous development of professional teachers, where teachers in Finland are involved in curriculum design and development and assessment of learning, which is an important professional role.

The OECD (Citation2018) proposed a framework for the development of education for all in the future (up to 2030) and discussed the role of stakeholders in teacher production of teachers. It was mentioned that teachers should be encouraged to apply their knowledge, skills and professional expertise in teaching practices within curricula that have been updated to adapt to changing societal norms and to meet students’ individual learning needs. Blömeke, Olsen & Suhl (Citation2016) and Skourdoumbis (Citation2017) have shown that much of the research to date has concluded that when educational management adapts to social and economic changes, the quality of teaching is related to student achievement, motivation to learn and other educational outcomes. One such change is the introduction of CBE to address educational inequalities, focusing on the development of competencies in learners, which may vary depending on the local context. In practice, however, every educational institution and teacher has to deal with the challenges of traditional teaching methods in the education system.

While teachers play an important role in designing, developing, and improving a CBE system, they should develop teaching designs that are aligned with CBE to keep up with the changes, and they need to collaborate with the community to facilitate collective learning (Casey, Citation2018; Voogt & Roblin, Citation2012). In developing appropriate teaching methods for CBE management, the first aspect is that teachers need to create challenging tasks for learners. These tasks promote learning by integrating knowledge and practice for application in problem solving. When learners successfully solve these tasks, the process leads to real learning (Clark & Estes, Citation1999; Hoogveld, Citation2003). The quality of teachers, their professionalism and the act of teaching itself are often seen as problems that need to be solved (Scott & Freeman-Moir, Citation2000), with educational issues being framed as ‘policy problems that require solutions’ (Bennett, Citation2019; Skourdoumbis, Citation2017).

Levine and Patrick (Citation2019) indicate that CBE should be: (1) learners are involved in making important decisions about their learning experiences, focusing on how learning experiences can be created, how knowledge can be applied and how learning outcomes can be continuously recognized. (2) assessment is seen as a positive learning experience and assessment outcomes contribute to improving learners’ competencies, enabling teachers to provide timely evidence of learning and improve teaching practices. (3) learners are encouraged to learn at appropriate times and in ways that meet their individual learning needs. (4) learners’ progress depends on the results of assessments. (5) learners follow their individual learning path. (6) teaching strategies aim to ensure educational equity for all learners. (7) competencies are measurable, clear, transparent, assessable and interpretable based on knowledge, skills and attributes.

Hartig et al. (Citation2008) found that there is a need to assess competencies on an individual and group basis in all sectors, defining competencies as complex structures that are highly relevant to complex problem-solving abilities in real-life situations. The assessment of competencies therefore requires the development of models and need to go through the evaluation of the reliability of the measured competency values. The development of theoretical models for assessment and the practical application of the results of competence represent a challenge for research in psychology and education. Furthermore, Shavelson (Citation2010) pointed out that an individual’s competencies are integrated as they attempt to respond to real-world situational problems. Complex competencies change over the course of performance, and once partial goals are achieved, new goals are set.

The assessment of competences therefore focuses on real tasks and teachers assess on the basis of learners’ responses to tasks based on their ability to demonstrate different competences and achieve the most effective outcomes. The process of competency assessment should therefore identify tasks, problems or stimuli that are thought to produce outcomes of complex problem solving. Competency assessment involves observing the individual’s behavior and responses to tasks after developing tools to observe problem-solving behavior. A constant question is whether the competence scores obtained are reliable and accurate. That is, whether or not the assessment results can be interpreted as reliable and accurate levels of performance based on the observed behaviors. Competency measurement or competency-based assessment (CBA) is a process that refers to measuring an individual’s or learner’s ability to effectively integrate knowledge, skills, and behaviors where they can bring knowledge, skills, and behaviors to the real world, then comparing assessment results to competence standards and interpreting the meaning of competence levels such as ‘adequate’, ‘sufficient’, ‘proper’, ‘suitable’, or ‘qualified’ to lead to improvement. Educators with competencies should be able to act knowledgeably in real educational situations (Ethel & McMeniman, Citation2000; Kelchtermans, Citation2007; Nessipbayeva, Citation2012; Niu et al., Citation2021; Russell et al., Citation2001).

However, the predominant method of assessment in education programs is summative assessment, which focuses primarily on the assessment of knowledge but often overlooks the importance of assessments that promote learning during the instructional process. Consequently, the results of these assessments do not provide learners with meaningful feedback, such as insights into their strengths, weaknesses, learning progress and potential strategies to improve their educational journey. This observation relates specifically to the Thai education context, where traditional summative assessments often emphasize the finality of assessment over developmental feedback. In other words, in the Thai educational context, there is a tendency for summative assessments to focus primarily on grading without providing comprehensive, developmental feedback that supports students’ continuous growth. This distinction emphasizes the need to integrate more formative assessment practices in the Thai education system to improve the overall learning experience and support student development more effectively. In the context of this research, Assessment for Learning (AfL) refers emphasizes the use of assessment to support and continuously improve student learning. In contrast to summative assessments that evaluate student learning at the end of an instructional period, AfL is formative and ongoing, providing students with regular feedback that helps them understand their learning progress, identify areas for improvement, and develop strategies to improve their knowledge and skills. This approach is in line with our aim to develop a competency-based assessment model that not only measures students’ competencies but also actively contributes to their learning and development.

In contrast, CBA focus on using the assessment results to support learners throughout their studies and ensure that they achieve the learning outcomes set out in the curriculum (Bok et al., Citation2013; Cizek, Citation2010; Glazer, Citation2014; Harrison et al., Citation2017; Ismail et al., Citation2022; Rezai et al., Citation2022). This approach requires a systematic process using mechanisms that facilitate understanding of what learners are acquiring. Integrated learning means that different skills are strategically combined to solve complex problems. Collecting and analyzing evidence from the learning process allows curricula to systematically observe and critically evaluate learners’ actions during instruction through continuous and thoughtful learning processes. This assessment mechanism helps learners recognize their developmental progress and accept their own abilities, while individualized tracking of learning progress provides insight into outcomes derived from practical application.

The competencies of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients play a critical role in defining the learning outcomes that teacher education institutions participating in the project need to achieve in order to produce ‘ready-to-teach’ educators. These competencies must be aligned with the needs of schools in remote and underprivileged areas in different regions of Thailand: North, Northeast, Central, East, West and South. The competencies include knowledge, academic skills, teacher spirituality, and practical skills in the teaching profession and community development. However, the current assessment of these competencies focuses only on knowledge and practice (Equitable Education Fund, Citation2022), which does not fully assess the spirit of teaching in the context of remote community schools. Effective competency assessment should use scenarios that simulate complex, real-life situations in remote settings and challenge student teachers to demonstrate their problem-solving skills by combining knowledge, teacher spirituality, and practical skills. The assessment tool developed by the research encompasses all these aspects and measures knowledge, academic skills, teacher spirituality, and practical skills required for the teaching profession and community development.

The Equitable Education Fund (EEF) has launched the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program, which aims to create educational opportunities for students in remote areas by training a new generation of teachers to improve the quality of schools in their home communities. This initiative focuses on giving impoverished but capable students with teacher spirituality to pursue a quality higher education in education. It aims to address the common problems of teacher shortages and high attrition, stimulate the creation of new learning management models in teacher training institutions, and improve the efficiency of teacher production and development systems. This approach is tailored to the specific circumstances of different areas and meets the overall needs of Thailand. It is expected that the introduction of these new teachers in remote schools will mitigate educational disparities and promote sustainable local development. Currently, the project is supporting 16 institutes in different regions of Thailand, with the first cohort having started in 2020 and the third to follow by 2022. These institutes offer specialized Bachelor of Education degree programs in early childhood education and primary education that promote specific competencies and attitudes to prepare students for their future employment in schools. However, in order to achieve the project’s objectives in terms of curriculum, teaching management and developing learners to a high standard of knowledge and professional experience (Equitable Education Fund, Citation2022), it is essential to monitor the core competencies, 21st century skills and specific competencies, and attitudes of the scholars. This process requires that teacher training institutes implement evaluation methods to track and promote alignment with project goals.

For the above reasons, the researchers are interested in developing a model to assess the competency base of third year students in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program. This initiative aims to develop a competency assessment model that will provide individualized profile on the competencies of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients. The aim is to use the assessment results for the development of these third-year students and to ensure that their competencies are in line with the objectives of the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program. This program aims to improve educational opportunities for students in remote areas, develop a new generation of teachers who are committed to their home communities, and play a vital role in improving the quality of schools in the communities, ultimately contributing to the development of the country’s human resources.

1.1. Research questions

This study aimed to develop a model to assess the competency base of third year students in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program, and using the following research questions:

What set of competency-based assessment can be developed for third-year students receiving scholarships from the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program?

How can a competency assessment model be developed for third-year students receiving scholarships from the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program?

What is the quality of the developed competency assessment model for third-year students receiving scholarships from the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program?

1.2. Research objectives

To develop a set of competency-based assessment for third-year students receiving scholarships from the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program.

To develop a competency assessment model for third-year students receiving scholarships from the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program.

To examine the quality of the competency assessment model for third-year students receiving ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program.

2. Literature review

2.1. Competency-based education

Competency-based education (CBE) is an approach to instruction that focuses on a personalized approach to education to ensure that each student acquires competencies by spending the necessary time on teacher-directed learning activities, regardless of how long the learning process may take for the individual (Le et al., Citation2014; Surr & Rasmussen, Citation2015; Surr & Redding, Citation2017). CBE sets learning goals that match the potential of individual learners, with each learner being responsible for achieving the learning goals set. The aim of the teaching process is for all learners to achieve these learning objectives. This requires teachers to provide individualized learning opportunities and support, allow learners to learn at different times and in different places, and use assessment for learning when learners are ready and to monitor progress over time. Surr and Redding (Citation2017) state that the key features of CBE are that (1) learners achieve mastery of competencies without instructors having to worry about time constraints, (2) learners are empowered through the development of clear, measurable and demonstrable competencies, (3) assessments are meaningful to learners and contribute to the creation of positive learning experiences, (4) learners are supported in developing competences at the right time and differentiated according to individual needs, and (5) learning outcomes are considered on the basis of the competences developed by learners, including the ability to apply knowledge and the development of knowledge alongside competences.

Holmes et al. (2021) and Le et al. (Citation2014) describe that in the CBE approach, learners are not only seen as recipients of knowledge, but as co-producers of knowledge. Le et al. (Citation2014) have identified three core components of CBE: (1) Competence acquisition: advancement in competency levels occurs only when a learner demonstrates proficiency based on clearly defined and measurable knowledge standards, ensuring that all learners meet the same educational standards. (2) Progression of learning: each learner progresses at a different pace and trainers must give learners the opportunity to demonstrate their competencies more than once. (3) Instruction: learners are supported in learning that is tailored to their individual needs to engage with more challenging content. Instructional materials are designed to promote and motivate learning and ensure that engaged learners can achieve their competencies.

In terms of the effective implementation of competency-based education, it is essential to consider both the holistic development of students and the strategic design of curricula. Roegiers (Citation2016) suggested that for the effective implementation of competency-based education (CBE), educational institutions at all levels must be prepared to take specific actions. First, student exit profile, which is an important indicator of their ability to integrate and harmonize their knowledge, skills and competencies acquired in the educational process, is clarified. This includes: (1.1) general information about the learning process that promotes ‘metacognition’ in a diverse cultural environment; (1.2) knowledge, practices, and attitudes that reflect individual expertise; and (1.3) problem-solving skills in complex situations where students must address problems in accordance with evolving economic, social, and cultural structures. This information should reflect students’ potential in terms of ‘learning through practical problem solving’ in an ever- changing environment. Secondly, the development of competency-based curricula is essential. This includes: (2.1) Curriculum designers grouping new course content in accordance with academic disciplines and according to student exit profile. Core content to be included in the curriculum should include: (1) actionable knowledge and procedural skills relevant to job-specific tasks; (2) life skills such as socio-emotional and interpersonal skills that are essential for daily life interactions and the promotion of ‘social coexistence’, e.g. civic education, peace and ethics; and (3) cross-cutting skills that are adaptable to the multiple and diverse professional tasks that result from interdisciplinary learning.

Designing competency-based education (CBE) includes several key components: (1) Identifying end competencies that drive change and align with graduate expectations. These expectations may come from predetermined outcomes, such as those set by accrediting bodies and professional organizations, or specific competencies that vary by discipline. (2) Define measurable sub-outcomes that students can practically achieve and learning objectives that are tailored to allow flexibility in achieving these end competencies. (3) Establish a continuous assessment process in which the assessment principles based on competence-based curricula serve as mechanisms for continuous competence development. This includes assessments before, during and after learning. Pre-learning assessments help teachers to design individual learning approaches and workload, while assessments during the learning process serve as monitoring tools to support and improve learning and allow adjustments to instructional methods. Post-learning assessments should not rely solely on written tests, but should include a variety of methods aligned to the competencies outlined in the curriculum (Schuwirth & Van der Vleuten, Citation2011). The aim of CBE is to develop core competencies that enable students to apply academic knowledge in practical situations. Therefore, the assessment during the learning process should be an ‘assessment for learning’ while the assessment at the end should be an ‘assessment of learning’ using methods that test the application of academic knowledge in simulated or real-life situations by authentic assessment. (4) Create an enrichment program that takes place as often as possible in a variety of real-life situations. These activities should be based on the theoretical foundations and include practical exercises that enrich the learners’ experiences. (5) Define the learning management process and assessment procedures that are comprehensive and integrate knowledge, skills and attitudes. This principle can be explained as follows: Upon completion of a competency-based curriculum, learners will be able to perform tasks effectively as they simultaneously develop theoretical knowledge, practical skills and work attitudes. In this context, knowledge, skills and attitudes need to be incorporated into the design of the curriculum, learning processes and assessment methods. (6) Establish a support mechanism that encourages learners to be responsible for their self-assessment and self-regulation. (7) Establish the role of teachers as coaches and experts and (8) Create a system that promotes acceptance and a positive attitude towards ‘lifelong learning’ (Mulder, Citation2012).

Andrade (Citation2020) examined teaching strategies aimed at empowering tertiary students to achieve career success through the use of cross-cutting skills such as communication, critical thinking, teamwork, problem solving, and collaboration. This research process was conducted using High-Impact Practice (HIP) guidelines to promote learner professional success. The goal of HIPs is to design curricula that emphasize learner engagement, curriculum implementation, and assessment according to high-impact practices. Andrade (Citation2020) pointed out that employers are looking for employees who have cross-cutting skills, particularly in the areas of communication, teamwork, ethical decision-making, analytical thinking and the ability to apply knowledge to real-life situations. This means that higher education institutions need to prepare learners for these skills. This study presents examples of curriculum development that promote cross-cutting skills, such as organizational behavior courses that are beneficial to undergraduate business majors. The curriculum development process follows high-impact practices (HIPs), which aim to design curricula that focus on learner engagement, implementation, and assessment based on high-impact practices. The components of curriculum design include (1) the design of assignments that involve collaboration between curriculum and business, (2) an electronic portfolio system, (3) the development of collaborative projects between educational institutions and businesses, (4) peer review of assigned work, (5) grading criteria, and (6) outcomes assessment.

2.2. Competency-based assessment

The concept of competence in relation to the roles and responsibilities of agencies involved in psychology was not initially clearly defined. McClelland (1973) suggested that ‘competency tests are more important than intelligence tests’ and he criticized intelligence diagnostics by stating that research in education and psychology needs concepts and assessment that take into account the situation and context of an individual’s actions. Competency-oriented diagnostics are about testing expectations for application in real-life situations and can predict differences in performance outcomes under different circumstances. He defines competence as the qualities required to perform a particular action successfully. However, he did not specify a particular theory (cited in Klieme et al., Citation2008). The key feature of the competence concept is therefore its relevance to real life. Bandura (Citation1977), a social psychologist, concluded that ‘there is a clear difference between the possession of knowledge and skills and the ability to apply knowledge effectively in a variety of situations under ambiguous and unpredictable circumstances’.

Connell et al. (Citation2003) describe competencies as ‘realized skills’, while Weinert (Citation2001) refers to key competencies as broad characteristics, such as linguistic competencies and meta-competencies that facilitate the use of specific skills, including strategies for thinking, learning, planning, work-related knowledge and understanding one’s strengths and weaknesses. Klieme et al. (Citation2008) mentioned that the educational organization that has adopted the concept of competencies for educational assessment is the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The OECD (Citation2003) emphasized the importance of international educational assessment by establishing a framework for the assessment of learners based on the outcomes of schooling, where the content of learners’ assessment is not based on the scope of subject content specified in the curriculum of educational institutions.

However, it assesses whether learners are prepared for the demands and challenges of future life and how it should be. OECD policy makers have set guiding questions for the assessment, which are: What can graduates be shown to be capable of? What role can learners play as creative citizens in society? In doing so, the OECD goes beyond the framework of curricula and the limitations of traditional competency models, where assessment is not limited to knowledge and skills in specific subjects or derived from psychological theories of general cognitive abilities. Instead, the OECD takes a functional perspective and asks educational institutions whether graduates are prepared to meet the needs and challenges of future life. The characteristics used to cope with these needs and unforeseen tasks are referred to as life skills or transversal skills. in 1998, the OECD established the framework for the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) to assess competencies. Thus, PISA defines mathematical literacy as ‘an individual’s ability to formulate, apply and interpret mathematics in a variety of contexts, including the ability to reason mathematically and to use mathematical concepts, procedures, facts and tools to describe, explain and predict phenomena in order to make the informed judgments and decisions required of constructive, concerned and reflective citizens’ (OECD, Citation2003, p. 24).

Following the definitions of reading and scientific literacy, which are relevant for application in everyday life and concrete work situations, and in response to the competency-based approach developed from the objectives of PISA, Weinert (cited in Klieme et al., Citation2008, p.9) proposed a concept of competencies to be used in large-scale educational assessments. The competencies to be assessed should be defined by the situations and tasks in which learners need to practice and acquire proficiency. In addition, assessment can be conducted by exposing learners to real work scenarios (or potentially simulated situations that closely resemble real contexts).

2.3. Challenges and strategies for effective competency-based education

The OECD (Citation2003) discussed the challenges associated with the measurement and assessment of competencies, including:

1. Knowledge and understanding of the structure of competencies

The structure of competencies is complex and adaptable depending on context, which leads to significant considerations when developing assessment tools. A key question is what model should be used to develop these tools and how we should interpret the meaning of competencies. The initial challenge in developing a competency assessment model lies in the variability of the competency assessment framework across different relevant contexts, such as individual characteristics and workplace situations. Consequently, the specific elements related to individuals and situations should be taken into account in order to define the competence structure for assessment purposes. Therefore, competence assessment requires a foundation in basic research on the structure of competences, competence levels and the theoretical and empirical development of competences underpinned by integrative and interdisciplinary research.

2. The competence-based assessment approach from a psychological perspective

The assessment of competence bases from the perspective of psychometrics involves ‘the encounter of the individual with the objects’ and emphasizes the interplay between theoretical structures and the results of empirical assessment. Psychometrics emphasizes that each assessment is determined on the basis of the effectiveness of the test situation. Given the complexity of competency structures, the competency-based assessment model in psychometrics must adhere to certain criteria. For example, assessors must be able to aggregate and integrate all relevant characteristics of a competent person in order to define the structure of the person being measured. Due to the complex nature of competence structures, item response theory forms the basis of a model that brings together the unique characteristics of each person and situation. This approach emphasizes the need for a nuanced understanding of both the theoretical framework and the practical implications of assessing competence in psychometric contexts.

3. The concepts and instruments used in the assessment

In the field of educational assessment, tools such as observation templates and direct observations by teachers play a crucial role in the assessment of competences, especially due to their direct interaction with learners. Given the complexity of competency structures, teachers should adapt and further develop these concepts and measurement tools to ensure that they accurately reflect real-life scenarios. Integrating technology into assessment methods not only allows for the creation of complex stimuli for immediate learner response, but also opens up opportunities to develop new assessment paradigms that provide more empirical data. This approach pushes the boundaries of traditional methods, as technology-enhanced assessments allow for the simulation of dynamic and complex situations that may not be adequately captured by traditional means.

4. The recognition and application of assessment results

The success of decision making and the improvement of educational management essentially depends on accurate and precise competence assessment. Such assessments can have various practical purposes, e.g. at the individual level, where they enable tailored learning support by educators for each learner. The results of individual assessments help to inform decisions about further education and future careers. In addition, an ongoing challenge is to define assessment formats, measurement rules and procedures that provide information aligned to specific objectives. Assessments that promote individualized learning should provide clear conclusions about the personal learning process and identify the learner’s strengths and weaknesses in relation to the curriculum. These insights can support personalized teaching and learning and improve instructional methods. Teachers can monitor learners’ understanding and learning efficiency through diverse means such as classroom discussions, homework and formal tests. These processes serve as individualized diagnostics to understand each student’s learning process and problem-solving abilities, as well as to identify misconceptions. Tailored feedback is to support the learning process as it provides individualized guidance that is tailored to each learner’s unique educational journey.

A major challenge in this context is the development of instruments that accurately assess educational competency and reflect educational objectives, and the interpretation of these results in relation to the curriculum. The impact of educational assessment on teaching methods and content is profound. Teachers can use the personal data collected in the classroom to evaluate their teaching methods and identify the specific instructional needs of learners. Detailed contextual information about students’ learning progress is essential for teachers to improve their instructional effectiveness. Some research suggests that diagnostic data obtained from state assessments is often not detailed enough to be used to promote individualized learning experiences for students.

Competency-based curricula need to develop new assessment processes. Innovation and complex coordination are needed to obtain a set of assessment tools that are consistent and appropriate to comprehensively capture learners’ competencies. One of the most important expectations of educational stakeholders is for learners to gain experience in the real world or workplace. Entrusting them with the performance of tasks in real-life situations or in the workplace is tantamount to making them part of a team to facilitate learning through the effective application of the knowledge, skills and attitudes acquired in the curriculum in their work.

Furthermore, assessment in real-life situations or actual workplaces that are complex is very important. This is because learners need to apply their knowledge, skills and attitudes in different contexts, and assessments are mostly conducted by workplace staff who may or may not have knowledge and experience in CBA. Effective field assessments need to be developed so that teachers, workplaces and learners can track the progress of existing competencies during their training in the program. The goal is to provide learners with accurate feedback on their development and to use assessment results to support decisions about passing or failing the program. Assessments should critically examine the competencies developed by learners. The techniques used for assessment should establish a link between the teaching processes and assessment, with the main aim of examining learning development throughout the course and ensuring that learners achieve the desired competencies according to the curriculum objectives. The clarity of the link between assessment and learning organization will facilitate learners’ experience of a coordinated and effective learning process. Assessment of competencies refers to the collection, analysis and interpretation of evidence from assessments and the use of the results to develop teaching methods. In teaching, the use of AfL in the classroom is extremely important (Lee, Citation2011; Van der Vleuten et al., Citation2017). Research on the use of AfL by teachers has shown improvements in learners’ competencies (Baartman, & Gulikers, Citation2017; Calenda & Tammaro, Citation2015; Kippers et al., Citation2018; Schuwirth & Van der Vleuten, Citation2011; Wolterinck et al., Citation2022).

2.4. Assessment for learning (AfL)

Assessment for Learning (AfL), as defined by Black and Wiliam (Citation2003), Black et al. (Citation2003) and Earl (Citation2003), involves a shift from traditional summative assessment, which summarizes student learning at the end of a period of education, to formative assessment, which involves assessment during the learning process. This shift is from simply assessing learning outcomes to gaining insights that can enhance student learning. In implementing AfL, teachers collect a variety of data to improve learning, such as insights from classroom observations, student work, questions asked in class, and student-teacher interactions. Any method that provides useful data for teaching and learning planning can be used. The results of these assessments highlight the strengths and weaknesses of individual students and provide feedback to support learning. AfL takes place during the learning process, with teachers supporting students, and can significantly increase students’ learning effectiveness.

Furthermore, The OECD (Citation2008) emphasizes the importance of assessment for learning and makes the following points:

Assessment for learning promotes lifelong learning goals through education policy at national and regional levels. It serves as a critical mechanism that enables lifelong learning by improving student achievement and allowing teachers to better design learning experiences. These assessments help to ensure that classroom outcomes are the same for all students and that different needs and learning conditions are taken into account. In addition, the information gained from such assessments helps teachers to provide guidance and feedback and encourages the development of ‘learning to learn’ skills,’ which are essential in the rapidly advancing information society.

Assessment for learning is critical to improving overall student achievement. Both quantitative and qualitative research on assessment for learning shows that it is one of the most important assesses for promoting skills.

Promoting educational equity: A study by Black and Wiliam (Citation2003) on the effectiveness of assessment for learning found that in educational settings with high numbers of ‘educationally disadvantaged’ learners, the use of assessment for learning led to higher student achievement. This is due to the focus on accommodating individual differences and promoting a learning culture that values these differences.

Sambell et al. (Citation2012) suggested the following approaches to conducting Assessment for Learning (AfL): (1) Authentic assessment involves assessment through meaningful tasks linked to real-life contexts that require learners to apply professional skills and knowledge acquired through practical experience; (2) Balanced summative and formative assessments; (3) Creating opportunities for practice and rehearsal that allow learners to develop their competencies before undergoing summative assessments; (4) Designing formal feedback to promote learning, which includes both written and oral feedback; (5) Designing informal feedback, i.e. feedback during peer and teacher collaborative work; (6) Developing learners as self-assessors and lifelong learners who need to assess their own progress and use this to develop their metacognitive skills.

2.5. Formative assessment and feedback

Formative assessment and feedback play a vital role in the educational process. Irons and Elkington (Citation2021) state that formative assessment should be employed in classroom management so that teachers can use the data gained from assessments to provide feedback to learners. Formative assessment is a pre-planned process used by both learners and teachers during lessons that involves integral and continuous assessment using a variety of assessment methods. The aim is to use the results as evidence of learner achievement and to improve learning outcomes to help learners become self-directed. In addition, Lu et al. (Citation2021) emphasize the important role of feedback in teaching as they consider it to promote learning. Feedback also helps learners to recognize the knowledge and skills they need to improve. The importance of feedback in CBE is highlighted as it is used to develop competencies and learners recognize that feedback is a crucial part of learning as it can be used to check their understanding and learning progress through formative assessment and feedback. Therefore, learners should be supported in their learning by repeatedly practicing skills to enhance learning, develop knowledge and improve competencies. The levels of feedback are categorized into four types: (1) task feedback/corrective feedback/outcome knowledge, which focuses on the success of a task and its correction and includes accuracy, neatness, or other criteria related to task performance, clarifying and reinforcing understanding of how well an assigned task is performed, and distinguishing between correct and incorrect answers or tasks; (2) process feedback, which provides advice on more effective information seeking and strategies for task production; (3) self-regulation feedback, which focuses on how learners monitor, manage and control their learning to achieve their learning goals, focusing on feedback on metacognition and evaluation of strategies used; and (4) self-feedback, in which learners reflect on their strengths and weaknesses in the process or outcomes of a task against set criteria (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007).

Shute (Citation2008) identified different types of feedback for learners, including: (1) No feedback: this is when the learner is asked a question and is expected to respond without knowing whether the answer is correct; (2) Verification/knowledge of results/knowledge of outcome: this type of feedback informs learners about the accuracy of their answers, e.g. whether they are correct or incorrect, or gives an overall percentage that is correct; (3) Correct/knowledge of correct answer: this feedback gives the correct answer to a specific task without additional information; (4) Try again/repeat-til-correct: this feedback informs the learner of an incorrect answer and allows one or more attempts to answer correctly; (5) Error flagging/error search: this highlights errors in a solution without giving the correct answer; (6) Verbose: a general term for feedback that includes explanations of why a particular answer was correct or incorrect and may allow the learner to repeat part of the instruction. It may or may not contain the correct answer; (7) Attribute isolated: an elaborated form of feedback that presents information that focuses on the central attributes of the concept or skill being studied; (8) Topic-related feedback: elaborated feedback that provides information on the topic being studied and may include a review of the material; (9) Response contingent: elaborated feedback that focuses on the learner’s specific response and explains why an incorrect response is incorrect and the correct response is correct without conducting a formal error analysis; (10) Cues/prompts: elaborated feedback that steers the learner in the right direction, e.g. a strategic hint about what to do next, or providing a worked example or demonstration without explicitly presenting the correct answer; (11) Errors/misconceptions: elaborated feedback that requires error analysis and diagnosis and provides information about specific errors or misconceptions, explaining what is wrong and why; (12) Informative tutorial: combines review feedback, error flagging, and strategic hints on how to proceed, usually without stating the correct answer.

2.6. Community-based teacher training

Teachers are expected to work with communities. This requires teacher education that prepares student teachers for such engagement (Harfitt, Citation2018; White & Kline, Citation2012). Yuan (Citation2017) described that teaching teachers about cultural diversity and promoting cultural awareness is an essential aspect of the educational curriculum. A major effort that needs to be made in the training of early childhood educators is to improve the content on cultural diversity. Mattsson et al. (Citation2011) pointed out that the use of practicum models in teacher education, administered by different universities that vary according to national, regional and local contexts, entails the allocation of different resources in terms of personnel, time, equipment and finances. Curricula differ and procedures for assessing curricula and knowledge of professional practice vary.

The models of pre-service student teaching practicum experience can be summarized as follows: (1) The master-apprentice model, in which student teachers learn from professionals, with professors and peers expected to provide valuable knowledge and practices for learning and development. (2) The laboratory model, in which universities have special units (Training School for Practicum Learning) that emphasize practical learning, and student teachers are trained by professional teachers in a pedagogical environment. (3) The partnership model, a form of collaboration between universities and selected local schools in which local schools provide hands-on learning opportunities and mentorship by qualified local teachers. (4) The community development model, popular in rural areas, in which teacher sneakers are expected to teach new concepts and methods to schools and teachers who want to improve their teaching standards, with student teachers participating in school development and learning the profession through real-world problems. (5) The integrated model where student teachers are trained under a college-community shared responsibility agreement. (6) The case-based model, which is inspired by medical training, focuses on training student teachers through comprehensive practice to improve learning analysis and interpretation skills through research, theory and experience. (7) The platform model, which provides flexibility to meet the needs and interests of individual student teachers in terms of field experiences. (8) The community-of-practice model, which is based on a culture of inquiry to promote learning from the community and provide student teachers with experience, competence and confidence in professional practice. (9) The research and development model based on collaboration between universities and communities to improve related research and school development. Harfitt (Citation2018) examined effective teachers and professional development practices within communities and found that community collaboration is critical to the management of experiential learning, with new teachers engaging in professional development through community-oriented teaching innovations, suggesting that institutions can utilize these models for student teacher training and preparation, with community partners serving as ‘co-teachers’.

2.7. Teacher production project to solve the problem of teacher production and development in Thailand

The New Generation Teacher Development Project to improve the quality of community schools or the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ Program

Equitable Education Fund: EEF (Citation2022) was established under the Equitable Education Fund Act, B.E. 2561 (2018), in Article 45(6) of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, which provides for the establishment of a fund to assist those who lack financial resources, to reduce inequalities in education, to improve the quality and efficiency of teachers, and to allocate state funds to the EDF. This has enabled the launch of projects to create educational opportunities for students in remote areas, such as the New Generation of Teachers to Improve the Quality of Community Schools or the KRU RAK THIN Program. The main principles of the project are: (1) promoting the fact that impoverished students with potential and the will to teach obtain a high-quality bachelor’s degree in education and return to teach in schools in their remote areas, focusing on education management that truly meets the needs of the community; (2) supporting the development of small schools in remote areas that need to improve quality from the beginning of the project, facilitating the joint learning of teachers and students; (3) supporting the adaptation of teaching and learning processes in teacher training and development institutions.

The results achieved will be able to bring about systemic changes in the country’s education system. The aim of the project is to provide underprivileged students with potential, good academic performance and teaching spirit the opportunity to acquire and complete a high-quality bachelor’s degree in education. The program equips them with the skills and readiness for 21st century learning and ensures that within 10 years they are deployed as new teachers in around 1,500 small schools in remote districts. This will reduce inequality in education and improve opportunities, impacting local development and addressing the issue of teacher shortages and frequent transfers. In addition, institutions will be supported in the design and development of new learning management systems, leading to a transformation of the future role of teachers and improving the efficiency of education administration. This approach will ensure that teacher training and development is tailored to the context of the area.

The qualifications of the teacher training institutions participating in the program include: (1) they are a public or private institution of higher education offering undergraduate degree programs in education, particularly in faculties of education specializing in elementary or early childhood education; (2) they are located in provinces where there are remote (protected) schools to which the scholars will be assigned and allocated after graduation in 2024; (3) they have dormitories for the scholars that are well supervised and conducive to learning; (4) they have remote schools as a network for professional practice. The characteristics of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ graduate teachers include: (1) they have the basic competencies of the teaching profession, including multi-grade classroom management, nurturing students with different potential, academic competencies, the spirit of teaching, and ethical moral values; (2) they have the 21st century skills; and (3) attitudes and specific competencies for returning to schools in remote communities, such as commitment to community development, responsibility to self and others, resilience under difficult conditions, sufficient life experience, adaptation to different situations, and the ability to create learning innovations through the combination of theoretical knowledge and practical application that benefit the schools where they are assigned and their home communities.

The Office of the Ministry of Higher Education et al. (Citation2016) launched the Teacher Production for Local Development project (2016–2029) as an initiative aimed at achieving selective selection of teachers through the provision of scholarships and/or job guarantees. The selection process involves a centralized system that simultaneously selects outstanding individuals nationwide to participate in this limited enrollment teacher production program. Successful candidates are guaranteed a teaching position in their home country upon graduation. During the program, collaboration is organized between the producing institutions and the employing schools to facilitate the adaptation of graduates to their school environment and ensure their success as teachers who will contribute to the development of their local areas. Higher education institutions with expertise and potential will be selected as teacher training centers under this project, with a focus on regional needs, especially in regions with significant teacher shortages that receive annual state funding. The project aims to (1) train a limited number of teachers in areas and regions where there is a shortage and critical need for primary and vocational education in Thailand, supported by research foundations; (2) train teachers with academic knowledge, professional expertise and a professional teaching ideology, using curricula and training processes that emphasize practical application and intensive training; (3) develop schools under the Basic Education Commission (OBEC) and the Office of the Vocational Education Commission (OVEC) in Bangkok and the Non-Formal and Informal Education Promotion Office (NFE) through a networked practice teaching process between faculties of education and schools.

The literature review indicates that CBE is a major challenge for universities. CBE needs to be rigorous and affordable while providing learners with a highly personalized and efficient means of earning a degree. This need leads to the adaptation of assessment processes that align with the principles of CBE, namely competency-based assessment (CBA). The aim of CBE is to develop learners’ basic and specific competencies required to solve complex and challenging tasks in the real world. CBA should include the following: (1) the identification of transformative endpoint competencies that lead to change and meet graduate expectations, possibly derived from predetermined outcomes such as accrediting body and professional association expectations or competencies that vary by discipline; (2) the definition of pragmatic sub-outcomes that learners can achieve, and the purpose of teaching and learning arrangements that enable learners to achieve the end-point competencies flexibly; (3) the design of assessment processes that aim to use these assessments as mechanisms for continuous monitoring of competence development, which should include multiple and comprehensive assessment structured around the defined competencies in the curriculum. Authentic assessments should be used for methods that assess the application of academic knowledge in simulated or real-life situations; (4) Specify learning activities that take place in as diverse real-life situations as possible. These activities should include theoretical learning activities and additional practical learning activities that extend learners’ practical experience; (5) Define comprehensive learning management and assessment processes that integrate knowledge, skills and attitudes. This principle states that upon completion of a competency-based program, learners will be able to perform tasks while developing theoretical knowledge, practical skills and work attitudes. In this regard, knowledge, skills and attitudes must be taken into account when designing curricula, learning processes and assessments; (6) Create a system that encourages learners to take responsibility for their learning and self-assessment; (7) Define the role of the trainer as coach and expert, and (8) create mechanisms to promote acceptance and a positive attitude towards lifelong learning.

2.7.1. Current study

The purpose of this study was to develop and examine the quality of the competency assessment model in order to create a high quality model for assessing individual competency profiles of KRU RAK THIN teachers. These are teacher training institutes that can be used to fully develop the competencies of KRU RAK THIN teacher students in their final year of study. These competencies are in line with the objectives of the KRU RAK THIN project, which aims to provide educational opportunities for economically disadvantaged students living in remote areas to become fully operational teachers in community schools in these areas. The current study was conducted with third-year student teachers who are in the middle of their studies and need to complete a professional practice in community schools in remote areas after graduation. Competency assessment is based on an approach to assessing learning that focuses on using assessment results to provide meaningful feedback to learners on, for example, strengths, weaknesses, developmental progress and individualized strategies to increase competency. Therefore, learning assessment involves gathering evidence from participation in complex and challenging simulated teaching activities in the context of remote schools. The assessment will be carried out using different methods in combination with coaching. The developed model will guide teacher training institutes in the systematic assessment of competencies together with student teachers, thus promoting continuous learning processes and critical reflection of their practice. This assessment mechanism helps students to recognize their learning development, accept their competences and includes individual competency development protocols to identify strengths and weaknesses.

3. Method

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ramkhamhaeng University for research involving human subjects (IRB No. 66/0010). The teachers in the remote area schools, the professors of the education curriculum, and the scholars gave their written consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

This research process comprises three distinct phases, each with its own unique research methodology, as follows:

Phase 1 involves the development of a prototype for the assessment model to assess the competency base of students who receive scholarships as part of the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program.

The Phase 1 research framework aims to develop an in-depth understanding of significant events related to teachers’ professional practice in schools in remote, underprivileged communities. This endeavor is part of the design and development of a prototype assessment of student competencies funded under the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program. Components include a prototype for an instrument to assess the competencies of these students and a prototype for a set of competency-based activities tailored to simulated scenarios. In this phase, the research team applies analytical analysis to draw conclusions from these significant events. The insights gained are then used to design activities that accurately reflect the real-life professional context of teachers in these remote community schools to ensure that interpretations match actual working conditions.

In this research, the integration of Assessment for Learning (AfL) principles is one of the important elements of the competency-based assessment model developed for the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program. The methodology includes various formative assessment techniques designed to provide students with continuous and actionable feedback. These techniques include regular reviews through quizzes, reflection journals, peer reviews, and teacher observations. Each assessment activity is followed by detailed feedback sessions in which students are given specific guidance on their strengths and areas for improvement. Teachers play a crucial role in promoting AfL by giving students the opportunity to reflect on their learning, self-assess, and set personal learning goals. This process ensures that assessment is not just a measure of learning outcomes, but an important component of the learning process itself, helping students to develop their skills more effectively.

Key informants of the study include:

Fifteen teachers working at schools where the first cohort of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients will be deployed after graduation. These schools are located in different regions of Thailand, including the north, northeast, center, east, west and south.

Fifteen faculty members from the Bachelor of Education program who specialize in early childhood education and primary education and are affiliated with the institutions from which the first cohort of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients are drawn. These faculty members come from the same regions as the schools.

3.1. The outcome of Phase 1

The results of the first phase of the study are:

Conclusions drawn from the events gathered through data collection in the residential areas and information obtained through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions.

A framework for assessing the competency base of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients.

Prototypes of activities based on simulated scenarios.

Prototypes of assessment tools for assessing the competence base of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients.

Prototypes of models for the assessment of the competence base of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients.

In the second phase, the study focuses on the quality of the prototype for assessing the skills base of students who are sponsored under the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program. In this phase, the prototype will be implemented on a trial basis before it is used to assess participants in the research study.

Key informants for this phase include:

Eleven experts who assess the prototype’s competency base for the grantees. These experts specialize in the following areas:

1.1 Curriculum and instruction in early childhood and primary education.

1.2 Educational assessment and evaluation.

1.3 Special education.

1.4 Educational psychology.

1.5 In-depth understanding of the main objectives of the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program.

Twenty-three first generation students from the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program at Rajabhat University Kanchanaburi.

3.2. The outcome of Phase 2

The prototype student competency assessment model for ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients is of high quality in terms of content validity as reviewed by experts in curriculum and instruction, educational measurement, special education, and school psychology. It has an item-objective congruence (IOC) index of 0.80 to 1.00. The evaluation of this prototype assessment suite, which was implemented after the testing phase, includes: (1) A set of instruments to measure knowledge and skills, in which the item difficulty index ranges from 0.22 to 0.80 and the item discrimination index ranges from 0.20 to 0.66, with reliability index of 0.80. (2) A set of instruments to assess teacher spirituality, which have a reliability value of 0.85 and the rater agreement index of 0.89. (3) A set of instruments for assessing teacher performance skills, with a reliability score of 0.86 and the rater agreement index of 0.89. (4) A manual for organizing activities based on simulated scenarios, focusing on accuracy, clarity, and completeness, with an IOC index ranging from 0.80 to 1.00.

Phase 3 involves the development and evaluation of the competency assessment model for students participating in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program.

Key informants:

Seven experts were involved in the review of the competency assessment model for the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients.

Research participants:

117 students from the first cohort of the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program, representing four educational institutions, participated in this research phase.

3.3. The outcome of Phase 3

The outcome of Phase 3 includes the development of a high-quality competency assessment model for students in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program. This model is characterized by its practical relevance, complexity of thinking, meaningfulness of assessment for learners, directness, reproducibility of decisions, comparability, transparency, fairness, cost and benefit, and overall impact of the assessment process.

4. Results and discussions

This section addresses two important issues: the quality of the competency assessment model for third-year students in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program and the quality of the competency assessment model for third-year students in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program.

4.1. The development of a competency assessment model for third-year students participating in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program

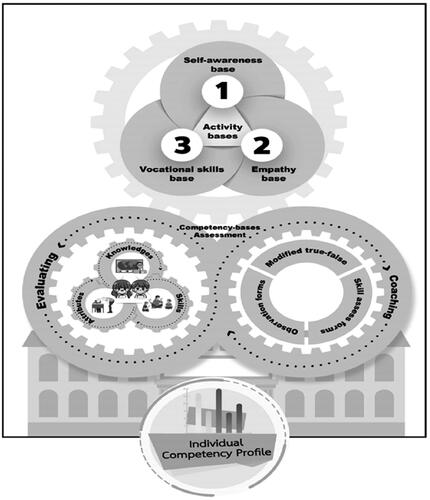

The model for assessing the competencies of third-year students who receive a scholarship as part of the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program is shown in . This model is based on the principles and processes of a developed assessment format based on the assessment for learning framework. It emphasizes the use of assessment results to reinforce the competencies developed as part of AfL. The goal of the model is to ensure that student outcomes are aligned with curriculum expectations and the goals of the Educational Equity Fund. These outcomes include integrated learning that encompasses academic knowledge and skills, the teacher spirituality, and practical skills for the teaching profession and community development in remote and underprivileged areas.

The system and mechanisms developed support students in understanding and utilizing their learning through an integrated process that strategically connects knowledge, experiences, and diverse skills based on a commitment to solving complex teaching challenges. This includes collecting and analyzing evidence of learning that enables teacher education institutions to assess student competencies during instruction. This is done through testing, observation, recording, feedback and systematic interpretation of assessment results in conjunction with learning management.

Immediate learning outcomes for fellows include thoughtful engagement with complex pedagogical challenges in community schools in remote areas. This assessment mechanism helps students recognize their developmental progress through supervised monitoring, self-assessment and acceptance of their abilities. In addition, recorded data is used to track students’ individual development, providing insight into the outcomes of practical implementation.

It can be observed that the principles and processes of the developed CBA model are in line with the research findings of Khatri et al. (Citation2020), who developed an interactive model for real-time competency assessment for career decision-making. The real-time model emphasizes the promotion of learners learning. Using assessment tools, learning is analyzed and used to improve learning efficiency. The model can identify learners’ true career interests to help them make career choices and enable them to recognize their true abilities. This is in line with Wolterinck et al. (Citation2022) who investigated methods to support teachers in using assessments to develop their AfL. The study shows that teacher competencies are complex; teachers need to integrate teaching skills, knowledge and attitudes to achieve effective teaching. The results of using AfL show that teachers can assess and improve their teaching. Teachers are able to analyze students’ learning processes and better reflect on their actions. Furthermore, this is consistent with Mulder’s (Citation2012) suggestion that CBA of educational institutions requires the implementation of continuous assessment processes. This is because the assessment principles aligned to a competency-based curriculum are intended to serve as mechanisms for tracking and developing competencies and include pre-learning, during-learning and post-learning assessments. Pre-learning assessments allow teachers to adapt teaching methods and define tasks that promote learning for individual learners. Assessments during the learning process serve as mechanisms to guide, monitor and improve learning and allow teachers to adapt teaching processes. Post-learning assessment should not rely solely on written tests, but should include varied and comprehensive assessments that are aligned with the competencies described in the curriculum.

In addition, the development of core competences aims to enable learners to apply academic knowledge in real life situations. Therefore, assessment principles should include the ability to apply knowledge in simulated or real-life scenarios. Consequently, assessment during the learning process should be conducted as ‘assessment for learning’, which is consistent with the notion that the importance of assessment for learning is to (1) promote lifelong learning goals among learners, as assessment results help educators to design learning experiences that meet the diverse needs of learners, (2) improve learner achievement (OECD, Citation2008), and (3) promote educational equity. The study by Black and Wiliam on the effectiveness of assessment for learning cited in OECD (Citation2008) found that in educational contexts with high numbers of ‘educationally disadvantaged’ learners, the use of assessment for learning by educators led to higher learner achievement. This is attributed to the fact that the focus of Assessment for Learning is on taking into account individual learning differences and the cultural learning context of learners.

When considering the discussion of research findings on the topic at hand, section 2 of the developed model comprises three main components. These are the assessment of competencies of students receiving scholarships from the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program, the basis for activities in simulated scenarios, and individualized profile on the competencies of ‘KRU RAK THIN’ scholarship recipients and personalized support strategies with several key components. The first component is the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ project’s assessment of grantee competencies. This is an assessment process aimed at supporting the improvement of students’ competencies (Assessment for Learning: AfL), with assessors performing two interlinked roles: coaching and assessing the competencies that emerge during participation in simulated teaching activities. The competencies assessed include (1) academic knowledge and skills related to the management of early childhood education and primary education, inclusive education, and the management of multi-grade classes in elementary school, which are assessed prior to participation in the activities with modified true-false items and essay test with scoring rubrics; (2) the teacher spirituality, which includes emotional and mental stability, empathy in curiosity, working responsibility in the school and community, social adjustment, attitude in commitment to community development, higher-order thinking, attitude towards working in a multicultural environment, and attitude in communication, and is assessed during participation in simulated teaching activities using observation forms and scoring rubrics, with assessors observing at least twice and using the first observation to support personal coaching for student teachers and to track progress of teacher spirit from previous cases; (3) Teaching practice, including learning experiences provision for early childhood with creating educational innovation, curiosity, building working responsibility in the school and community, commitment to community development, designing the development of innovative learning management suitable for the target school, higher-order thinking skills to handle complex problem solving, communication skills and multicultural teamwork, and multi-grade classroom management in primary levels, assessed while participating in simulated teaching activities with observation forms and scoring rubrics, with assessors observing teaching practice at least twice, using the first observation to provide personalized coaching to student teachers and to track progress in teaching practice from previous cases.

The second component involves teacher activities in simulated scenarios. These are designed to assess the competencies of the fellows under real-life conditions that accurately reflect the teaching environment in remote and underprivileged areas of Thailand. The design of these scenarios covers both the teacher spirituality and the practical skills required for the profession, including emotional and mental stability, empathy, attitude in curiosity, working responsibility in the school and community, social adjustment, attitude in commitment to community development, higher-order thinking, attitude towards working in a multicultural environment, attitude in communication, management of early childhood experiences in conjunction with innovative learning methods, curiosity, building working responsibility in the school and community, commitment to community development, designing the development of innovative learning management suitable for the target school, higher-order thinking skills to handle complex problem solving, communication skills, multicultural teamwork, and multi-grade classroom management in primary levels.

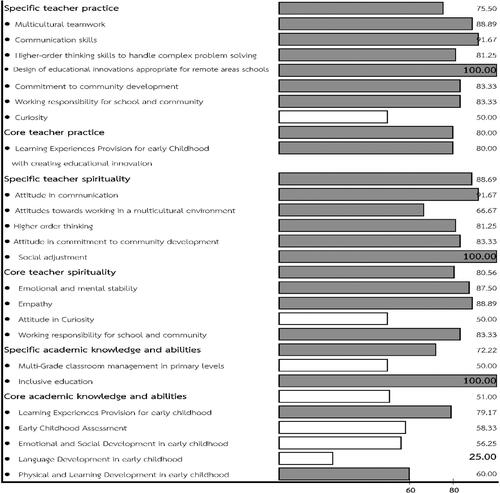

The third component, relating to the reporting of student competencies and tailored support strategies (see ), shows the alignment of the assessment format for scholarship students’ competencies in the third year of the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program with the frameworks proposed by the OECD (Citation2008), Jones (Citation2005), Hartig et al. (Citation2008), Klieme et al. (Citation2008), and Van der Vleuten et al. (Citation2017). These sources emphasize that educational institutions face the challenge of developing mechanisms for accurate and reliable assessment of competency-based curricula. The process involves:

Figure 2. An example of the competency data of the first scholarship recipients in the ‘KRU RAK THIN’ program.

Understanding the competency structures: educational institutions should establish the basic model for developing assessment tools and interpret the competencies accordingly. The main challenge in developing a competency assessment model is to define a flexible framework that takes into account relevant contextual factors such as individual characteristics and workplace situations.

Psychometric assessment models: This aspect concerns the ‘interaction of persons with objects’ and emphasizes the relationship between theoretical structures and empirical assessment results. Marks are awarded on the basis of the effectiveness of the test situation. Given the complexity of competency structures, psychometric assessment models must meet certain criteria, including capturing all relevant characteristics of the individuals whose competencies are being assessed.

Concepts and instruments for measurement: Non-standardized assessments and observation of learning processes, such as teacher observation, are directly involved in competence assessment. Due to the complex structural nature of competencies, it is necessary to adapt and develop concepts and measurement tools that accurately reflect real-life situations.

Recognition and utilization of assessment results: The success of educational management decisions and improvements depends on accurate and precise competency assessments. The objectives of these assessments can vary, for example at an individual level where assessments help to personalize the learning support provided by sneakers. The results of individual assessments play an important role in decisions about further education and future career paths. Shavelson (Citation2010) points out that individuals’ competencies are integrated as they strive to respond to real-world problem-solving situations. Complex competencies develop over the course of task performance, and as sub-goals are achieved, new goals are set. Therefore, competency assessment focuses on real-world tasks and teachers assess learners’ responses to tasks based on their ability to draw on different competencies and achieve the most effective outcomes.