Abstract

This study elucidates how doctoral students perceive the challenges and impediments of their doctoral programs. In this study, the demands of doctoral programs are characterized as challenges that stimulate students’ potential and hindrances that threaten their well-being. Thirty-five full-time PhD students at various stages of their programme participated in semi-structured interviews as part of a qualitative study. The thematic analysis investigated students’ challenges and hindrances in their programs. Qualitative research identified three themes under challenge and hindrance demands: institutional, supervisory, and personal. The study developed six propositions based on transactional stress theory regarding challenge and hindrance demands. These propositions assist supervisors and doctorate educators in explaining the challenge and hindrance demands framework in a doctoral program context. Demands, such as ambiguity in doctoral research roles, inadequate resources for doctoral programs, and interpersonal conflict, threaten the well-being of doctoral students. Challenge demands such as workload, role responsibility, and role complexity support students’ potential growth and well-being. Furthermore, the present study offers three recommendations for enhancing the doctoral program: establishing an approachable institutional ecosystem, emphasizing the vital role of supervisors, and fostering work-life balance among students.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

A doctorate, a highly esteemed credential required for entry-level academic positions, is essential for enhancing the quality of research outcomes (Darley, Citation2021; Schmidt & Hansson, Citation2021; Skopek et al., Citation2022). To achieve this, regulatory bodies and educational institutions prescribe high-quality research requirements (Darley, Citation2021). Doctoral students must develop proficiency in complex concepts and theoretical frameworks, familiarize themselves with extensive literature, acquire hands-on experiences with research techniques and procedures, and contribute novelty to their chosen field of study (Ryan et al., Citation2021). Research conducted in OECD member countries over the past decade has revealed that doctoral students experience more chronic stress than other populations, increasing their risk of developing anxiety and depression (Cornwall et al., Citation2019; Pervez et al., Citation2021). For instance, Levecque et al. (Citation2017) indicated that 32% of scholars in Belgium are likely to have at least two psychiatric disorders, while 41.9% of PhD students in France reported feeling stressed and anxious (Marais et al., Citation2018). Additionally, 26.7% of scholars in India have depression disorders (Leethu et al., Citation2021), and 15.5% of PhD students in the UK report having suicidal thoughts (Milicev et al., Citation2023). These mental health issues among doctoral students impede their academic progress and prolong their completion time (Ryan et al., Citation2021).

Previous studies have identified specific factors that can affect the mental well-being of PhD students. These include the university’s general working procedures, lack of domain-specific expertise, lack of resources, supervision-related issues, student-related issues, an unresponsive academic community, ability to write critically, personal and professional life imbalance, pressure to publish, and financial insecurity. Levecque et al. (Citation2017) identified these factors as job demands students encounter in their study and research roles.

Management studies have investigated job demands from various perspectives and theoretical frameworks. One of the most promising ideas for explaining the demands of doctoral education is the challenge and hindrance demand framework. McCauley and Hinojosa (Citation2020) utilized this framework to comprehend the two facets of job demands in doctoral management programs: hindrances or unfavourable parts of the program’s demands and challenges or positive features. Notably, these two types of demands have opposing effects on engagement, psychological well-being, job performance, and psychological strain (Lin et al., Citation2014). The diverse demands of a PhD program stem from several factors, such as research projects, supervisors, advisory boards, peers, family influence, educational experiences, and individual choices (Hum, Citation2015).

The demands for doctorate programs are generally categorized as belonging to supervisors, institutions, or personnel, and they can significantly influence students’ well-being (Horta & Li, Citation2023; Jones-White et al., Citation2022). Although the requirements of PhD programs have previously been independently examined at each of these three levels, less attention has been paid to the nature of the program’s multilevel demands. This prior research has limited our understanding of how demands affect student engagement, exhaustion, and well-being. McCauley and Hinojosa (Citation2020) examined three doctoral program vignettes to determine the challenges and hindrances of the program: seminar design, mentorship, and professional development. However, this research was limited as it only considered institutional demands rather than supervisory or personal demands and did not employ a rigorous study methodology to assess the consequences of these demands on students’ well-being. To overcome these limitations, the current study focuses on the hindrances and challenges related to doctoral programs at the institutional, supervisory, and individual levels and how they affect students’ mental health. The study’s theoretical basis is predicated on the idea that doctoral students engage with peers, supervisors, and the university, resulting in various demands that present challenges and hindrances. The current study used a qualitative technique to investigate how scholars view the comprehensive demands of a PhD program that affect students’ well-being to address these concerns.

This study aimed to investigate how prevalent doctoral students perceive a variety of hindrances and challenges, as these data may be necessary in developing institutional policies that support students’ mental health. The current study aimed to uncover the different challenging demands that students can persevere through and effectively overcome, as these demands are likely to impact their well-being substantially. To ensure students finish the program on schedule, practitioners and institutions must identify the reasons hindering their progress and establish a more stable and supportive environment. This study offers a framework for the challenges and hindrances related to a PhD program that academic institutions and instructors should consider when creating a curriculum to enhance students’ mental health.

2. Background and theoretical foundation

2.1. Doctoral program demands

Using the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model and conservation of resources theory (COR), prior research has examined the effects of demands and resources on the well-being of doctoral students (Caesens et al., Citation2014; Sufyan & Ali Ghouri, Citation2020). These prior studies compared the demands of a PhD program to those of a work (or job) using the JD-R model to evaluate the demands and resources of a doctoral program. However, these studies did not consider any multilevel demands (Caesens et al., Citation2014; Sufyan & Ali Ghouri, Citation2020); instead, they focused solely on the influence of resources on students’ well-being. Ryan et al. (Citation2021) operationalized the job demands of doctoral education, including mastering complex concepts of the study, becoming a methodological expert, connecting research results to various stakeholders, demonstrating high levels of self-management skills, completing doctoral program requirements on time, minimal supervision, and publishing high-quality academic articles. Drawing on the Job Demands-Resources model and the position taken by Ryan et al. (Citation2021), we use the term "doctoral program demands" to refer to the demands experienced by students in their specific study and research roles. We define doctoral program demands as a group of tasks such as coursework, updating research skills, maintaining mentor groups, developing research networks, managing multiple roles, handling responsibilities, presenting at conferences, publishing in quality journals, and writing theses during their research tenure to achieve institutional and individual goals.

The demand for doctoral programs to enhance the quality of research students’ performance is increasing. The literature employs various terms such as "issues," "factors," "crisis," "obstacles," and "experience" (Darley, Citation2021; Skopek et al., Citation2022) to describe these demands. However, these studies did not categorize demands from various sources, including institutions, student supervisors, and personal pressure. Only a few studies have independently recognized program requirements without considering the overall structure of the doctoral program. Hence, it is vital to investigate the various demands at program institutions’ level of support in structuring their doctoral programs and uncover whether these demands motivate or hinder doctoral students.

2.2. Challenge and hindrance demand framework

The differentiation of job demand features into challenge and hindrance demands is based on the transactional stress theory (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), coined by Cavanaugh et al. (Citation2000). Transactional stress theory explains that doctoral students’ interaction with their program environment shapes how they perceive a situation, categorizing it as either hindering or challenging. According to Lepine et al. (Citation2005), challenge demands provide opportunities for personal growth and achievement, whereas hindrance demands impede these outcomes and lead to distress. A challenging work environment offers opportunities to satisfy basic psychological needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy. This motivates individuals to invest more energy and effort, ultimately contributing to their well-being. By contrast, hindrance demands are perceived as threatening constraints that undermine well-being. For example, PhD students might view program demands as challenges to overcome with supportive resources or hindrances to retaining their research interests and feelings beyond their ability to handle them.

When a doctoral student perceives the demands of a program to be hindrances, they may experience adverse results, such as increased withdrawal behaviours, reduced job satisfaction, decreased performance, and well-being. These hindrance demands include resource inadequacy, interpersonal conflict, role ambiguity, organizational politics, and administrative hassles (Lepine et al., Citation2005). In contrast, challenging demands in the work environment led to positive consequences such as job engagement, increased performance, interest in learning, and well-being. These challenges result from time pressure, pace of work, pressure to complete tasks, job responsibility, complexity, and workload. Hindrance demands are negatively associated with study engagement and performance and positively associated with depression and anxiety. Conversely, challenge demand results in inverse relationships. Doctoral education inevitably includes stressors; the "student" appraises them as hindrances or challenges.

Considering the above discussion, we formulated two central research questions:

What challenges do full-time doctoral students face in contributing to their well-being?

What hindrance demands among full-time doctoral students impede their well-being?

This study used a qualitative approach to explore the framework of challenge and hindrance demands in the context of doctoral programs. Thematic analysis, derived from semi-structured interviews with doctoral students, was employed to identify patterns, themes, relationships, and insights of doctoral education that stem from the theoretical challenges and hindrances of the framework.

3. Method

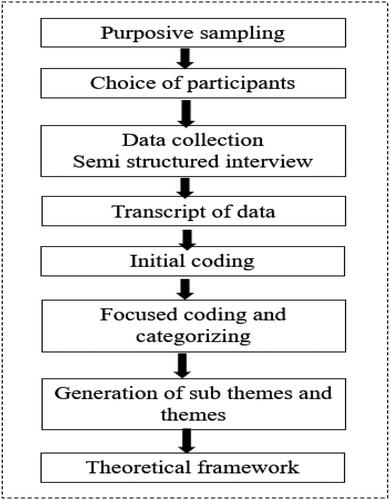

The exploratory qualitative approach served as the foundation for developing the study assessment framework designed to evaluate the demands of the doctoral program. Semi-structured interviews with full-time social sciences and humanities doctoral students were employed using a qualitative approach. We developed a theoretical framework using a thematic analysis approach.

3.1. Qualitative research design

This study employed the interpretive paradigm (Thanh & Thanh, Citation2015) to examine the experiences of doctoral students in their program journey. Using thematic analysis principles (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), we analyzed the qualitative data by code development, reviewing the codes, comparing participant data and codes, identifying the patterns and themes from the codes, naming the themes, and ensuring the trustworthiness of the study (Nowell et al., Citation2017). The findings from the interviews provide insights into how doctoral students perceive their program, which includes the institutional, supervisory, and personal demands they face.

3.2. Purposive sampling

This study used a purposive sample design to gain insights into the differentiated demands of social sciences and humanities doctoral students. This sampling method required a range of participants with in-depth knowledge of the research topic. This approach ensures information saturation among selected doctoral students (Palinkas et al., Citation2015). We employed purposive sampling techniques to ensure that the participants were from various stages of their PhD education and possessed diverse characteristics (such as gender, year of registration, multiple disciplines, university type, marital status, teaching workload, scholarship status, and age). Zakariya and Wardat (Citation2023) identified the different types of demands experienced by teachers that influence their well-being. Hence, we have considered doctoral students studying in various stages of their program to report their challenges and hindrance demands. Participants’ characteristics are presented in .

Table 1. Demographical summary of the participants.

3.3. Choice of participants

The present study began by selecting universities based on their rankings in India’s National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF), from which participant data were procured. The universities chosen were accredited by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC), an Indian accrediting authority. In India, full-time doctoral programs are accessible at four types of universities: central, private, state-owned, and deemed to be universities. These universities deliver doctoral education with slight modifications in program design across various disciplines, including program duration, obligatory academic publications, coursework requirements, teaching workload, and administrative duties (Cornwall et al., Citation2019; Hum, Citation2015).

Thirty-nine research students from a particular state in India were interviewed; they were enrolled in any of the four universities accredited by the NAAC and ranked among the top 100 NIRF. The study interviewed social science and humanities doctoral students by considering a list from the OECD discipline. Hence, the study included doctoral scholars pursuing their studies in business and management, economics, commerce, education, psychology, political science, public administration, law, sociology, econometrics, philosophy, and journalism (OECD, Citation2023). Typically, full-time scholars take three to four years to complete a doctoral degree in the social sciences and humanities. Four students declined to record their views on the audio-recording instrument.

Consequently, interview recordings of thirty-five students were considered for thematic analysis. Interviewing the 33rd PhD candidate brought us to the point of data saturation as the pattern of collected data began to repeat itself, and no new information beyond the elements of the theoretical category was discovered. However, three additional students were interviewed to ensure accurate outcomes.

3.4. Data collection and procedure

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted to gather the qualitative data. According to DeJonckheere and Vaughn (Citation2019), this method enables the researcher to collect unstructured data, explore participants’ opinions, feelings, and beliefs regarding a specific topic, and delve deeply into private and sensitive matters. At the start of each interview, an overview of the study was provided, and participants’ consent was obtained, ensuring that their responses would remain confidential and anonymous (see Appendix 1). To protect participants’ anonymity, this study utilized deductive disclosure (University Grants Commission, Citation2019), and pseudonyms were employed throughout the thematic analysis (Kaiser, Citation2009) to safeguard the privacy of the link between the data and identifiable participants. Most participants were interviewed on campus, and audio recordings of the 20-to 45-minute interviews were conducted with their permission.

The interview manual is divided into two sections. The first section collected demographic information to understand better the participants’ educational backgrounds, including gender, university type, year of PhD registration, age, family status, availability of scholarship facilities, and teaching workloads per week after coursework. The second section employed eight questions to extract descriptive responses from the interviews. The first three questions were designed to help interviewees feel comfortable. The subjects of the following two questions were the interviewees’ professional background, the institution’s requirements for completing the PhD program in their respective universities, and their status in the program. The following two questions captured their challenges and hindrances throughout the program journey. As the interview concluded, the participants’ suggestions were requested (see ).

3.5. Thematic analysis

To facilitate precise coding, the first author transcribed the digital audio-recorded data rather than summarising it. Atlas.Ti (version 7) software was used to organize, analyze, and interpret the transcript data. Unique codes were assigned to each transcript to convey the meaning of the communicated patterns.

To ensure the qualitative credibility of the data, the researchers carefully examined the communication patterns during the initial and focused coding processes. All authors were involved in data analysis, which led to a deeper understanding of the data. Guidelines for theoretical sampling were followed to increase the breadth and depth of ideas regarding the challenges and hindrances faced by doctoral students. Group coding was conducted by identifying responses that reflected the study’s research issues and had similar meanings.

A comparative approach was utilized to observe the emergence of data generation and collection. The theory of doctoral program demand was developed using codes, group codes, and subsequent themes. The coded segments and new codes were compared and discussed at each stage until the authors agreed. Themes, codes, and subcodes were obtained from literature and qualitative analysis, as shown in .

Table 2. Themes and codes obtained from literature and qualitative analysis.

Theme 1: Hindrance demands.

Theme 2: Challenge demands.

3.6. Generation of themes

The study utilized a qualitative thematic analysis to identify three primary themes—institutional, supervisory, and personal demands—by examining challenges and hindrances. These themes were derived by identifying fundamental concepts within the challenge and hindrance demands framework. The interview quotes were coded and categorized into codes, subthemes, and themes, as exemplified in (annexure) by representative responses from doctoral students. The thematic analysis employed to develop the theory of demand for doctoral programs is shown in .

3.7. Findings of qualitative analysis

3.7.1. Hindrance demands

Pervez et al. (Citation2021) stated that doctoral students encounter demands from various sources, including institutional, supervisory, and personal, which can either facilitate or impede their progress. These demands may lead to either beneficial or detrimental outcomes. However, when demands are hindering, they can deplete students’ psychological energy, diminish their engagement and motivation, and negatively affect their well-being. McCauley and Hinojosa (Citation2020) identified the hindrances students must overcome, such as unclear requirements, organizational politics, conflicting feedback, program or policy issues, and abusive supervision. In the present qualitative interview, several hindrances were uncovered, including uncertain program policy, work-life imbalance, financial strain on families, incompatibility between supervisors and students regarding competence and behaviour, and limited institutional resources for research.

3.7.1.1. Institutional hindrance demands

3.7.1.1.1. Uncertain program structure and policy

The participants in our qualitative study indicated that a lack of clarity in institutional research policies and infrastructure negatively impacted their well-being. They identified various factors, including the uncertain duration of programs, insufficient coursework content, inadequate credit and program completion requirements, unclear academic publication criteria, excessive administrative workload, discrepancy between teaching workload and study area, and delay in thesis evaluation, as obstacles to doctoral well-being.

One participant responded, "In our university, there is no fixed time for PhD completion: in a few departments, it is said to be three or four years; it needs even five or eight years in other departments. The department has no uniformity; therefore, we cannot fix anything. It is a minimum of five years in management."

These findings underscore the ambiguity surrounding the role of doctoral scholars in research, which hinders their ability to acquire knowledge and develop themselves as researchers.

3.7.1.1.2. Absence of research infrastructure

Numerous interviewees indicated that there were insufficient learning resources and methodologies, restricted access to specific software crucial for data analysis, inadequate finance and economic databases, minimal and irrelevant feedback from domain experts during advisory committee meetings, limited prospects of obtaining a fellowship due to intense competition, and scarce funding for conferences and publications. These institutional obstacles hinder students’ progress in their PhD journey and exacerbate the negative consequences on their well-being. The scholars highlight the limitations of research infrastructure as follows:

Researchers are expected to use new methodological tools to gain visibility, thus enabling them to publish in top journals. However, students were left to learn these research tools. In addition, institutions do not provide any support for gaining access to sophisticated research tools. Even my study requires sophisticated software for analysis, so now I must check for other alternatives.

3.7.1.2. Supervisory hindrance demands

3.7.1.2.1. The lack of supervisor- students’ competencies fit

For the success of doctoral students, their supervisors must possess the necessary qualifications, competencies, and academic supervisory skills, as Jackman and Sisson (Citation2022) emphasized. A person-environment fit between supervisors’ and students’ competencies is essential for a successful research journey (Parker-Jenkins, Citation2016). Our study revealed that multiple participants were dissatisfied because of a lack of supervisor competencies in guiding and fostering them as independent researchers, highlighting the inadequacy of available resources. The ineffective leadership style of supervisors can burden students and hinder their access to necessary resources.

A participant described the lack of supervisor resources: "I am from a technical background, and my management research area is Initially, I had a topic in my mind, but I altered it because my supervisor is from an unfamiliar area."

3.7.1.2.2. Inadequate interpersonal relationship style

Insufficient resources and inadequate interpersonal relationships can negatively impact the well-being of doctoral students. Research supervisors who engage in bullying, verbal abuse, and public humiliation can hinder student progress, as evidenced by Janssen et al. (Citation2020) and Hunter and Devine (Citation2016). The participants in our study emphasized the need for supervisors to be more explicit and precise in their responsibilities to promote advancement. Supervisors’ constant disapproval and discouraging behaviour prevented them from presenting their best research performance. Thus, it contributes to interpersonal conflict and negatively impacts morale and motivation.

My supervisor sometimes mistreats and insults me; he always disagrees with what I have planned for and executed. He is changing his communication version now and then, which makes it difficult for me to figure out his statement’s actual or internal meaning.

3.7.1.3. Personal hindrance demands

3.7.1.3.1. Family financial demands

According to Katz (Citation2018) and Szkody et al. (Citation2023), recipients of research assistantships and fellowships have higher completion rates and shorter times to a degree than students who do not receive such assistance. However, universities or government scholarships for doctoral students studying management, the humanities, and social sciences are limited compared to other disciplines (Neumann, Citation2007). Despite a compound annual enrolment growth rate of 10.7% over the past five years (Government of India, Citation2021), the government or institutions have not increased the number of fellowships or stipends. As a result, many doctoral students self-fund their studies, which can affect their ability to pursue primary life goals, such as getting married, starting a family, managing household expenses, travelling, covering medical costs, and purchasing a car or home. Several interviewees reported that their financial concerns significantly hindered their ability to achieve these goals. The participant said, "For the first three years, we get a stipend of approximately $315, which we need to manage conferences and journal publications. My family and parents depend on me. I have already reached 32 years with a small stipend. I recently married, and our family maintenance expenditure is increasing; staying in a rented home, travel, and daily expenses greatly stress me."

3.7.1.3.2. Work-family conflict

Students who live with their families often feel less like they belong because of the weight of their family responsibilities, which exacerbates the stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms brought on by their constant workload (Jones-White et al., Citation2022). In the interviews, participants divulged that they were obligated to fulfil numerous familial duties, such as nurturing children and elderly parents, performing daily domestic chores, paying heed to family members, and overseeing their partners’ careers. However, the obligations associated with their PhD studies consume substantial family time, leading to work-life conflicts. Consequently, students encounter difficulties managing their familial and research responsibilities. Moreover, the participants discussed their conflicts with their partners as they attempted to balance their obligations and complete their doctoral degrees.

I have a five-year-old daughter, and my work gets affected if she is ill. I spend time on my research, so I cannot spend time with her. My husband stays far from his mother and works as a marketing executive. My daughter is now not feeling well, and she meets her father once every 15 days, even though he is busy with his career. After registering for my doctoral research, I came to my mother’s place so my daughter could stay with me. So, there is always a fight between my husband and me to discharge the responsibility towards my daughter.

3.7.2. Challenge demands

Challenge demands can exert considerable pressure, yet students’ commitment to academic excellence is a potent stimulus. Moreover, the challenge seeks to augment students’ well-being and academic engagement. The following section classifies challenge demands into three discrete subcategories.

3.7.2.1 Institutional challenges

3.7.2.1.1. Workload of program

Despite the significant challenges and limitations associated with pursuing a doctoral degree, including managing competing demands for time and energy, students can enhance their expertise and proficiency by leveraging accessible resources (Cornwall et al., Citation2019; Horta & Li, Citation2023). Most participants acknowledged that they must juggle a wide range of responsibilities. Indeed, after enrolling in their programs, they must select a research topic, review academic literature, learn various data analysis techniques, present their findings at conferences, work as teaching assistants, publish their research in esteemed journals, and complete their theses. Although these tasks demanded exceptional time management skills from students, they viewed them as opportunities to develop their abilities and contribute to the academic community. Participants reported using the resources provided by their institutions, such as mentoring and support from faculty advisors, access to research funding, and facilities for participation in workshops and seminars, to help them achieve their goals and overcome the challenges they faced.

Initially, we explored a few topics, and it took us approximately three to four months to develop the last topic. Later, I took more time to identify these variables. Then, finally, I took almost a year to develop the last proposal.

3.7.2.1.2. Difficulties in academic writing and publication

The global educational environment, marked by the "publish or perish," presents an overwhelming and stress-inducing landscape for researchers. This environment significantly contributes to burnout (Haven et al., Citation2019; Tijdink et al., Citation2013). Here, research participants reported encountering various publisher-related issues, such as rejection, extended revision processes, divergent opinions, and reviewer comments. Even students contend with writing a journal article without prior training, selecting an appropriate journal that matches the scope of the manuscript, and utilizing the correct methodology to present the research findings. As mentioned, the interviewees expressed dissatisfaction with the institutions that mandated publication training. Although the publication process can be challenging, it can be navigated more effectively with the adequate resources provided by institutions or specialists.

Learning to write for publication is one part. The other side faces challenges related to the publishing process. The pressure to face the rejection of our articles, the longer review duration, the waiting time for confirmation of acceptance, and its eventual publication take a heavy toll on us. It is challenging to identify the journals in which our study fits itself for its publication in the future.

3.7.2.2. Supervisory challenges

3.7.2.2.1. Work pressure on supervisors

The importance of frequent communication between students and research supervisors is highlighted by research conducted by Jackman and Sisson (Citation2022) and Parker-Jenkins (Citation2016), which indicates that the quality of research is notably high in such cases. However, many participants in our study reported that their supervisors had multiple responsibilities, including simultaneously supervising numerous scholars, teaching at various institutions, managing administrative tasks at their institutions, and providing academic advice at innumerable institutions. These responsibilities can challenge students to pick up on their supervisors’ research and scholarly traits. Nonetheless, supervisors’ networking and teamwork helped students overcome these obstacles.

My supervisor has multiple roles in our institution. For example, he is the chairperson of the Board of Studies, offers talks and chair sessions at most conferences, and conducts research at other universities. He had six doctoral students working under him as full-time university students. Therefore, it is very challenging for me to get support from him; sometimes, my supervisor and I sit for discussions late at night, until midnight.

3.7.2.2.2. Emotional and technical support imbalance

Doctoral supervisors can mentor students by providing technical and emotional support (Janssen et al., Citation2020). Few interviewees expressed satisfaction with their supervisors’ emotional support in acknowledging their family concerns and research competencies, which is consistent with Wang et al. findings. The student’s performance is enhanced by the research supervisor’s various roles as a mentor, subject matter expert, and network builder with other academic institutions.

My supervisor is conventional. The patient provided only peripheral guidance. He did not read whatever I had fully sent or read my article. However, he read the abstract and conclusions appropriately. He does not interfere much with my work, although he ensures I am still working. Initially, I faced problems adjusting to him. I call him or meet him once in 15 days.

3.7.2.3. Personal challenges

3.7.2.3.1. Multiple and continuous roles

Undertaking a doctoral degree involves constant education and instruction shaped by many roles and obligations, necessitating considerable devotion and perseverance on the part of the students. The interviewees stated that they attended online or in-person training sessions on the diverse methodologies offered by various institutions. To alleviate their feelings of anxiety and psychological distress, participants believed that their obligations towards research networking and competencies ought to be reinforced throughout their doctoral journey.

Apart from the coursework, I have attended several training programs on publishing articles, data analysis, research method, research ethics, reference management, etc., that helped me better understand the topic.

3.8. Development of a theoretical framework

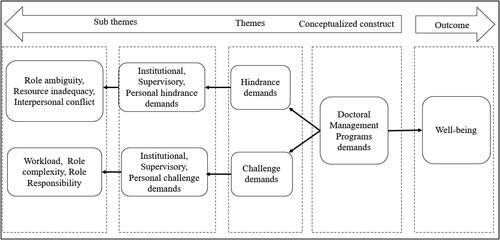

A theory of differentiated demand for doctoral programs was developed using a qualitative research design. This theory posits that doctoral students face two main job demands: challenges and hindrances. Drawing on the zone of proximal development proposed by Vygotsky (Citation1978), a proposition was developed to address the challenges and hindrances of the doctoral program. This proposition emphasizes the importance of building a foundation for student competencies as a source of motivation for completing doctoral challenges. Based on qualitative research, the study’s findings are connected to the demands of the differentiated doctoral program, providing a concise and focused summary of the critical relationships and perspectives of the challenges and hindrances of doctoral program demands. We generated a theoretical framework from the thematic analysis of the interview data, as shown in .

The proposed proposition demonstrates how the qualitative research conclusions are supported by the data, thus enhancing the rigour and credibility of the study. Using a thematic analysis approach, the demands of doctoral research challenges were defined as those that encouraged, inspired, and motivated doctoral students to conduct research and generate high-quality research output. However, the hindrances of the doctoral program hamper and restrict doctoral students’ research. Cavanaugh et al. (Citation2000) used the challenge hindrance demands framework to thematically analyze and derive the concept of doctoral program challenge demands, including research workload, complexity, and responsibility. Similarly, insufficient resources for doctoral research, role ambiguity, and interpersonal conflict were grounded in subcategories of doctoral research hindrances.

3.8.1. Propositions

This theory proposes six essential hypotheses.

Institutional hindrances: Doctoral students may experience hindrances in their research endeavours if the university or department lacks a comprehensive framework for doctoral programmes. These hindrances include inadequate coursework with inefficient evaluation, an unclear structure for the doctoral program, and a lack of student advisory and counselling services. Furthermore, inadequate workspace infrastructure, insufficient scholarship opportunities, and deficient stipends are examples of limited institutional resources that reflect the inadequacy of resources in the doctoral program structure. Upon closer examination of these "institutional hindrances," it becomes evident that a lack of academic resources and ambiguity in research policies contributes to inadequate doctoral research, negatively impacting scholars’ well-being. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Proposition 1: The well-being of doctoral students is hindered by the ambiguity of the doctoral research role and the insufficient institutional resources provided for the doctoral program.

Supervisory hindrances: Doctoral students often confront significant hindrances in sustaining healthy relationships with their supervisors throughout their doctoral journeys. These challenges may include abusive supervision, harassment, comparison with other scholars, criticism, humiliation, unrealistic expectations, and disparities in academic credibility. Moreover, differences in competencies, leadership styles, and psychological traits can lead to inadequate supervisory resources. This "supervisory hindrance" in the student-supervisor relationship can impede the doctoral path. Thus, we propose the following research hypothesis:

Proposition 2: The adverse consequences for doctoral students’ well-being are exacerbated by heightened interpersonal conflict between students and supervisors and a dearth of supervisor support.

Personal hindrances: Rigorous and persistent demands of the doctoral program may lead to time constraints for students, which can cause challenges in managing their work and personal lives. PhD students can experience a range of issues, including difficulty fulfilling family responsibilities, limited social life, and insufficient time for study, all of which can contribute to work-life conflict. Additionally, the scarcity of resources available to students, such as financial constraints related to family obligations, research expenses, and publishing fees, can exacerbate this situation. Our study also highlights students’ barriers, such as the challenge of prioritizing family time, financial limitations, and a lack of emotional and financial support from family members. Based on these findings, we propose the following hypotheses:

Proposition 3: Work-life conflict and resource depletion result from an imbalance between family responsibilities and the demands of the doctoral program, as well as a shortage of financial resources, which can negatively impact the well-being of students.

Institutional challenges: In doctoral programs, students must undertake extensive research responsibilities and complete them within a specified time frame. To facilitate their learning, it is recommended that instructors employ Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) to design training programs that motivate students to acquire new skills and knowledge. Students will enhance their acquisition of research techniques by working independently and setting achievable goals. Although adding these skills takes time and effort, institutions can overcome these challenges by collaborating with experts, as demonstrated by the ZPD. Furthermore, institutions can improve student engagement and well-being by recognizing and addressing the "institutional challenges" such as duration, complexity, and level of responsibility. Based on this, we propose the following.

Proposition 4: The greater the complexity of a doctoral program, the more beneficial it is for students’ well-being.

Supervisory challenges: The success of a doctoral program is contingent upon the compatibility between the student and their supervisor, as the absence of this relationship can harm students’ well-being. On the other hand, the student’s zeal for learning alleviates the program’s complexity and necessitates extraordinary dedication. Our qualitative research and previous studies suggest that overcoming "supervisory challenges" equips students with the skills to become autonomous researchers and prepares them for future endeavours. Doctoral candidates can achieve this objective under the guidance of their supervisors or in collaboration with more seasoned professionals.

Proposition 5: The higher the supervisor’s capacity to manage the duties and workload associated with their role, the more favourable the scholar’s well-being will be.

Personal challenges: Due to the complexity and significant responsibilities of the doctoral program, students may feel compelled to adopt a workaholic attitude that fosters creativity and enhances their academic self-efficacy. Motivation, performance, and overall well-being will likely increase when a program’s demands are perceived as goal-oriented and manageable. By immersing themselves in intensive research methodologies, analyzing diverse research techniques and tools, and developing proficiency in academic writing skills, students can fulfil their basic psychological needs, such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Our qualitative analyses indicated that personal challenges in adapting to the program and acquiring new skills can improve student performance and well-being. Consequently, we propose the following hypotheses:

Proposition 6: The greater the emphasis on learning the various responsibilities of the doctoral research program, the higher the students’ well-being.

4. Discussion and implications

This study aimed to ascertain the prerequisites of a doctoral program for full-time doctoral students through a qualitative examination. The investigation findings were classified into three categories based on thematic analysis: institutional, supervisory, and personal demands. Significantly, this study is the first to present evidence for the two-factor model of differentiated job demands within doctoral program demands.

4.1. Theoretical contributions and implications

This study makes two critical theoretical contributions.

Students’ appraisal of the challenges and hindrances of the PhD program: Evaluations of doctoral students’ programs are rooted in Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) transactional stress theory. According to this theory, this study considered how students evaluated their experience in the doctoral program and interacted with the demands on multiple occasions. Participants narrated several instances that exemplified the challenges and hindrances they encountered in their programs. In response to the first research question, the students discussed their perceptions of the demands of their program, which included limited resources for research, uncertainty in the program structure, and conflicts with supervisors and family members that they had to resolve independently. Participants perceived these demands as frightening because of insufficient support resources.

Regarding the second research question, students perceived demands as challenges that motivated them and provided an alternative resource to complete the task, such as time-bound workloads, complexity of doctoral programs, and responsibilities. They explained that these challenging demands were more conducive to fostering learning and motivating students. The participants used examples to illustrate institutional policy challenges, supervisor counselling, and individual stress. We recommend that doctoral educators employ the vignettes described above to develop student-centred teaching philosophies that capitalize on challenges and minimize hindrance demands.

Availability of supporting resources: The demands of doctoral programs are more likely to be perceived as challenges when students feel they are being addressed with appropriate resources. To maintain lower stress levels, doctoral students are motivated to build, preserve, and develop current resources and track the acquisition of new resources in various ways according to the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989), which was supported by our study. Resources, such as training in different research methodologies, stress management workshops, peer collaboration opportunities, knowledge of publication requirements, academic writing proficiency, leadership, and emotional mentorship from a supervisor, play a significant role in how students assess and adapt to demands. These resources likely help students manage contextual demands effectively, and they can rely on them to mitigate the negative consequences of excessive demands. The support provided to students in terms of professional, emotional, and social support enhances their psychological well-being and helps them balance their professional academic demands and personal lives.

Learning through Zone of proximal development (ZPD): The ZPD theoretical framework outlines the range of tasks that a learner cannot independently accomplish with the aid of a mentor. This framework provides valuable insights into the learning process of PhD candidates who are perpetually encouraged to broaden their knowledge and expertise. By applying the tenets of this framework in practical settings, supervisors and academic institutions can help students achieve their academic goals and make significant contributions to their field of study. For instance, supervisors may assign additional readings to help students comprehend challenging theoretical concepts, present information differently, or enable them to collaborate with an experienced colleague who can offer guidance. If students contend with organizing their thoughts in their dissertation, the supervisor can provide feedback on their writing process, helping them outline their chapters as they write or connect them with a writing tutor. Doctoral students who are overwhelmed by their workload and struggle to meet deadlines can seek support from their supervisors in devising a time management plan, breaking down large tasks into smaller ones, or finding a counsellor who can teach them stress management techniques. Students can also benefit from ZPD by enhancing their metacognitive and self-awareness skills, indispensable to lifelong learning. By discerning the optimal learning styles of their students, academic institutions can create more efficient teaching and learning strategies that elevate their PhD standards. Moreover, institutions can cultivate a nurturing and collaborative learning environment where students are inspired to reach their utmost potential.

4.2. Practical implications

Our study has three critical implications for the doctoral program.

Approachable institutional ecosystem to facilitate doctoral research: A doctoral degree’s accomplishment depends primarily on institutional factors. Financial security is a significant concern for several doctoral students. Institutions might look at increasing funding for doctoral research by offering scholarships and fellowships from private government partnerships. Moreover, increasing the benefits of living stipends based on the cost of living, scholars’ childcare support, article publishing charges, and financial support to attend international seminars and conferences can significantly reduce financial hindrances. Second, institutions should ensure clear, consistent, and achievable doctoral programme demands. The program framework should be presented more transparently, including stages of the doctoral program and meeting deadlines, study subjects and attainment of credits during coursework, research publication guidelines and requirements, and the dissertation format. Doctoral students should be actively guided by their institutions to meet regularly with their advisors to discuss progress and challenges, collaborate with interdisciplinary and international domain experts to gain diverse perspectives and expertise for their research and schedule frequent meetings with subject experts at other learning institutions to ensure that their research problems are addressed effectively. Third, institutions can help their doctoral students with professional advancement by organizing training sessions on data analysis, scientific article writing, time management, and research methodologies. Furthermore, institutions allow students to access licensed research databases and administer research instruments. Institutions may organize formal and informal mentorship programs, research writing workshops, and career service workshops on resume writing and interview skills to empower students for success within and beyond academia.

Fourth, institutions ensure students’ mental well-being by organizing meditation or yoga sessions. In addition, institutions can make more mental health services available to students who need them the most and provide wellness programs on campus that promote healthy living. Institutions should enhance stress management or mindfulness training to equip doctoral students with additional stress management methods. Finally, institutions can cultivate a supportive doctoral student community by organizing interdepartmental social events to foster connections and a sense of belonging among doctoral students. Institutions can support student-led teams through faculty involvement and the creation of peer mentorship programmes. Institutions should provide dedicated spaces within the university environment where doctoral students can connect, offer support, and celebrate each other’s achievements.

The critical role of supervisors: Doctoral students may have difficulty maintaining positive relationships with their supervisors. To deal with this problem, supervisors need proper training to build research skills and mentor their doctoral students effectively. For a successful one-on-one mentorship relationship, supervisors should establish a clearly stated doctoral requirement, provide continuous constructive feedback, and provide guidance to motivate or encourage their students. This relationship is nurtured by providing training and being an excellent interpersonal communicator while simultaneously being willing to collaborate with others or maintain positive working relations within one’s discipline. Continuous and honest communication between supervisors and students assists in adjusting to the research culture, providing technical and emotional support, and improving professional growth. To help doctoral students achieve professional growth, supervisors may also promote students’ networks with professionals in their specializations and encourage them to attend technical seminars.

The supervisors remain updated in the latest research. Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools include access to powerful academic search engines, text summarization tools that condense lengthy papers, concept generation tools, data analysis, writing assistance, and citation management with AI integration. The study’s conclusion adds to the importance of student collaboration, which allows them to be successful in their study since they are guided by their supervisors, who are equally mentors to the students.

Students’ coping mechanisms and resilience strategies: The rigorous requirements and complexity of the doctoral program necessitate significant investment in personal space and time. At this stage, students are emotionally obligated to fulfil their familial responsibilities. Doctoral students who embrace problems in their PhD programs as challenges cultivate growth attitudes and are typically more resilient. This enables them to reinterpret the challenges as opportunities for achievement and mental health. Students can build excellent time management skills to prioritize tasks, create realistic objectives, and effectively manage their workload by following up with academic schedules and time management tools. To balance their academic obligations with their personal lives and improve their mental health, students must partake in physical activity, a balanced diet, meditation, or quality time with loved ones. Cultivating a healthy support system with colleagues, advisors, mentors, family, and friends offers guidance, emotional support, and feelings of belonging. This network may support doctoral students, recognize their accomplishments, and guide them through challenges.

Furthermore, doctoral students must establish their constraints and maintain a work-life balance. Students who plan time for hobbies and social activities report being more focused and feeling better. Students must also use university resources, such as writing groups, stress management or time management programs, and mental health counselling services to receive additional support. For tasks such as data collection, writing for academic journals, dissertation writing, employing advanced data analysis tools, leveraging reference management software, incorporating applicable AI research tools at different stages of their studies, scheduling specific writing times, and using writing strategies such as freewriting, students must learn how to manage their research and personal time (AlAli & Wardat, Citation2024). Students should ask their advisors, supervisors, committee members, faculty, and peers for constructive feedback and direction on any opportunities or challenges. Along the way, students may recognize essential milestones in their research work as a source of inspiration and reminder of a more comprehensive picture.

4.3. Limitations and directions for future research

The present study has been subject to several limitations, which have been noted. First, the research has predominantly concentrated on the demands of the doctoral program and its influence on students’ well-being. However, this study did not examine the relationship between the availability of resources and students’ well-being. Future studies should explore this relationship in greater depth. Second, the study did not fully address the need for a suitable scale to represent the demands of the doctoral program. Future investigations could aim to develop a scale that considers the proposition made in this study to capture the demands of a doctoral program. Third, this study did not examine the moderating or mediating factors that influenced or constrained doctoral research. Future research could explore the internal resources of doctoral students to promote their well-being. Longitudinal research designs can be employed to investigate differential effects on well-being and moderating resources. Fourth, the focus of the study is limited to India, while the four types of universities mentioned have distinct requirements for doctoral education. Future research could disregard the findings of this study to generalize to a larger sample size, as many OECD nations face similar mental health issues among their PhD candidates.

5. Conclusion

The main aim of this study was to investigate how doctorate students perceive the hindrances and challenges they face in their programs and how these demands impact their overall well-being. This was achieved by employing transactional stress theory. The study utilized a qualitative research methodology and categorized the challenges into three groups: those related to the institution, those related to supervision, and those related to personal circumstances. Thematic analysis principles were used to analyze the students’ perceptions of the demands of their doctoral programs. The study’s six propositions offer theoretical support to educators and supervisors. Doctoral student well-being is threatened by a lack of clarity in their doctoral research roles, insufficient resources for doctoral programs, and interpersonal conflicts between students and their supervisors or families. Challenges such as workload, role responsibility, and role complexity can promote student growth and well-being if managed effectively. Finally, this study provides essential recommendations for supervisors and educators to support the well-being of doctoral students.

Supplementary file.docx

Download MS Word (32.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vrinda Acharya

Vrinda Acharya is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Commerce, MAHE, Manipal. Her research interests include education psychology, stress management, Artificial intelligence, higher education, well-being, and human resources.

Ambigai Rajendran

Dr Ambigai Rajendran is an Associate Professor with the Department of Commerce, MAHE, Manipal. Her interests include interdisciplinary research, digital behavioural studies, and women and child studies.

Nandan Prabhu

Nandan Prabhu is an Associate Professor at T.A. Pai Management Institute (TAPMI), Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), Manipal. His teaching interests are corporate valuation, financial statements analysis, financial accounting, and financial management. He has 40 publications, including accepted and forthcoming papers in leadership, managerial psychology, and corporate finance journals. His current research focuses on mindfulness in the workplace, organizational politics, team effectiveness and corporate governance. He has conducted over 30 faculty development programs on writing research papers. He has participated as a panelist in the academic conferences held at several management institutes.

Aneesha Acharya K

Aneesha Acharya K is currently working as an Assistant Professor (Sr. Scale) in the Department of Instrumentation and Control Engineering, MIT, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. He has around 13 years of experience in the field of teaching and research. He holds a PhD in Hand Rehabilitation from Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. He has eight publications in peer reviewed journals. His area of interest is Biomedical Instrumentation and qualitative research.

References

- AlAli, R., & Wardat, Y. (2024). How will ChatGPT shape the teaching learning landscape in future? Journal of Educational and Social Research, 14(2), 336. https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2024-0047

- Ali, F., Shet, A., Yan, W., Al-Maniri, A., Atkins, S., & Lucas, H. (2017). Doctoral level research and training capacity in the social determinants of health at universities and higher education institutions in India, China, Oman, and Vietnam: A needs survey. Health Research Policy and Systems, 15(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0225-5

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Caesens, G., Stinglhamber, F., & Luypaert, G. (2014). The impact of work engagement and workaholism on well-being-the role of work-related social support. Career Development International, 19(7), 813–835. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-09-2013-0114

- Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65

- Cornwall, J., Mayland, E. C., van der Meer, J., Spronken-Smith, R. A., Tustin, C., & Blyth, P. (2019). Stressors in early-stage doctoral students. Studies in Continuing Education, 41(3), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1534821

- Darley, W. K. (2021). Doctoral education in business and management in Africa: Challenges and imperatives in policies and strategies. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(2), 100504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100504

- DeJonckheere, M., & Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Semi-structured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigor. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), e000057. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Government of India. (2021). All India Survey on Higher Education 2020-21. https://aishe.gov.in/aishe/BlankDCF/AISHE Final Report 2020-21.pdf

- Haven, T. L., de Goede, M. E. E., Tijdink, J. K., & Oort, F. J. (2019). Personally perceived publication pressure: Revising the Publication Pressure Questionnaire (PPQ) by using work stress models. Research Integrity, and Peer Review, 4(1), 1–9.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513

- Horta, H., & Li, H. (2023). Nothing but publishing: The overriding goal of PhD students in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau. Studies in Higher Education, 48(2), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2131764

- Hum, G. (2015). Workplace learning during the science doctorate: What influences research learning experiences and outcomes? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 52(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.981838

- Hunter, K. H., & Devine, K. (2016). Doctoral students’ emotional exhaustion and intentions to leave academia. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 11(2), 035–061. https://doi.org/10.28945/3396

- Jackman, P. C., & Sisson, K. (2022). Promoting psychological well-being in doctoral students: A qualitative study adopting a positive psychology perspective. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 13(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-11-2020-0073

- Janssen, S., Van Vuuren, M., & de Jong, M. D. T. (2020). Sensemaking in supervisor-doctoral student relationships: Revealing schemas on the fulfilment of basic psychological needs. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2738–2750. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1804850

- Jones-White, D. R., Soria, K. M., Tower, E. K. B., & Horner, O. G. (2022). Factors associated with anxiety and depression among US doctoral students: Evidence from the gradSERU survey. Journal of American College Health, 70(8), 2433–2444. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1865975

- Kaiser, K. (2009). Protecting respondent confidentiality in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 19(11), 1632–1641. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309350879

- Katz, R. (2018). Crises in a doctoral research project: A comparative study. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 211–231. https://doi.org/10.28945/4044

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Leethu, L. T., Hense, S., Kodali, P. B. B., & Thankappan, K. R. (2021). Prevalence and underlying factors of depressive disorders among PhD students: A mixed-method study in the Indian context. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 14(4), 1704–1717. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-04-2021-0131

- Lepine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & Lepine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 764–775. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.18803921

- Levecque, K., Anseel, F., De Beuckelaer, A., Van der Heyden, J., & Gisle, L. (2017). Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Research Policy, 46(4), 868–879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.02.008

- Lin, W., Ma, J., Wang, L., & Wang, M. (2014). A double‐edged sword: The moderating role of conscientiousness in the relationships between work stressors, psychological strain, and job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1949

- Marais, G. A., Shankland, R., Haag, P., Fiault, R., & Juniper, B. (2018). A survey and a positive psychology intervention on French PhD student well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 109–138. https://doi.org/10.28945/3948

- McCauley, K. D., & Hinojosa, A. S. (2020). Applying the challenge-hindrance stressor framework to doctoral education. Journal of Management Education, 44(4), 490–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562920924072

- Milicev, J., McCann, M., Simpson, S. A., Biello, S. M., & Gardani, M. (2023). Evaluating mental health and wellbeing of postgraduate researchers: Prevalence and contributing factors. Current Psychology, 42(14), 12267–12280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02309-y

- Neumann, R. (2007). Policy and practice in doctoral education. Studies in Higher Education, 32(4), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701476134

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691773384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Website: Education Classifications. (2023). https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Parker-Jenkins, M. (2016). Mind the gap: Developing the roles, expectations, and boundaries in the doctoral supervisor–supervisee relationship. Studies in Higher Education, 43(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1153622

- Pervez, A., Brady, L. L., Mullane, K., Lo, K. D., Bennett, A. A., & Nelson, T. A. (2021). An empirical investigation of mental illness, impostor syndrome, and social support in management doctoral programs. Journal of Management Education, 45(1), 126–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562920953195

- Rönkkönen, S., Tikkanen, L., Virtanen, V., & Pyhältö, K. (2023). The impact of supervisor and research community support on PhD candidates’ research engagement. European Journal of Higher Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2023.2229565

- Ryan, T., Baik, C., & Larcombe, W. (2021). How can universities better support the mental well-being of higher-degree research students? A study of students’ suggestions. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(3), 867–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1874886

- Schmidt, M., & Hansson, E. (2021). "I didn’t want to be a troublemaker" – Doctoral students’ experiences of change in supervisory arrangements. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 13(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-02-2021-0011

- Skopek, J., Triventi, M., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2022). How do institutional factors shape PhD completion rates? An analysis of long-term changes in a European doctoral program. Studies in Higher Education, 47(2), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1744125

- Sufyan, M., & Ali Ghouri, A. (2020). Why fit in when you were born to stand out? The role of peer support in preventing and mitigating research-related stress among doctoral researchers. Social Epistemology, 34(1), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2019.1681562

- Szkody, E., Hobaica, S., Owens, S., Boland, J., Washburn, J. J., & Bell, D. (2023). Financial stress and debt in clinical psychology doctoral students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 835–853. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23451

- Thanh, N. C., & Thanh, T. T. (2015). The interconnection between interpretivist paradigm and qualitative methods in education. American Journal of Educational Science, 1(2), 24–27.

- Tijdink, J. K., Vergouwen, A. C., & Smulders, Y. M. (2013). Publication pressure and burn out among Dutch medical professors: A nationwide survey. PloS One, 8(9), e73381. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073381

- University Grants Commission. (2019). Academic integrity and research quality. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.ugc.ac.in/e book/Academic%20and%20Research%20Book_WEB.pdf

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wang, F., Zeng, L. M., Zhu, A. Y., & King, R. B. (2023). Supervisors matter, but what about peers? The distinct contributions of quality supervision and peer support to doctoral students’ research experience. Studies in Higher Education, 48(11), 1724–1740. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2212024

- Zakariya, Y. F., & Wardat, Y. (2023). Job satisfaction of mathematics teachers: An empirical investigation to quantify the contributions of teacher self-efficacy and teacher motivation to teach. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-023-00475-9