Abstract

Student engagement needs to be context-specific to embrace holistic learning for increasingly diverse students in higher education. This paper presented a case study on the context-specific adaptation of a student engagement measure for a private university in Bangladesh. The adaptation process involved steps such as benchmarking theoretically sound student engagement measures, drawing on the opinions of academic experts, and statistical model fit analysis. A 34-item adapted Measure of Student Engagement in Higher Education (MSEHE) was tested with 953 undergraduate and postgraduate students from two disciplines. This process expanded the original five-component student engagement measure with new insights such as students engaging with integration of ideas from real-life problems. The MSEHE had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s standardised alpha = 0.61 to 0.91) and model fit (RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.933, NNFI = 0.923). All domains of student engagement in the MSEHE were positively and significantly correlated. Hierarchical regression analysis confirmed that the three domains of the MSEHE (i.e. cognitive, affective, and social engagement with teachers) can also predict student satisfaction. A systematic process of context-specific adaptation is critical for a pragmatic student engagement measure capable of directing the university toward achieving long-term goals such as implementing outcome-based education and having employable graduates.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Student engagement is a critical and relevant concept in global and contemporary contexts of higher education, as noted in several studies across countries in various geographical locations and cultures, such as Brazil, China, Ethiopia, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America (Assunção et al., Citation2019; Bowden et al., Citation2021; Cassidy et al., Citation2021; Moges et al., Citation2023; Sharif Nia et al., Citation2023). An appropriate measure of student engagement is pivotal in facilitating positive student outcomes, including academic achievement, successful program completion, lifelong learning skills, and a commitment to civic citizenship (Christenson et al., Citation2012; Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018; Öz & Boyacı, 2021). However, measuring student engagement is challenging. It involves capturing holistic learning outcomes for students, which necessitates an understanding of their behavioral, affective, social, and cognitive processes and gains (Cassidy et al., Citation2021; Evans et al., Citation2018). Additionally, any measure of student engagement should be grounded in a sound theoretical framework and rigorously assessed through psychometric evaluation (Zhoc et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the chosen measure must align with the specific higher education context and cater to the needs of various stakeholders, including national governments, employers, academics, and educational institutions (Cassidy et al., Citation2021; Evans et al., Citation2018).

Western countries now face a diverse student cohort, with increasing participation from foreign students (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Citation2018). As a preferred option in this market, universities in the West emphasize excellence in education through positive student engagement (Evans et al., Citation2018). In countries like Australia (Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching, 2021), the United Kingdom (Rowan & Neves, Citation2021), and the United States (Ewell & McCormick, Citation2020), national surveys of student engagement are well-established practices in higher education. East Asian universities in China and Taiwan also have increasingly diverse student cohorts, due in part to higher university student participation in line with local economic growth (Hou (Angela) et al., Citation2015; Zeng & Kapoor, 2021). While universities in East Asia also measure student engagement to vouch for quality of education, it has been highlighted that quality assurance assessments should be more sensitive to local needs (Xu et al., Citation2021; Hou (Angela) et al., Citation2015). In this respect, retesting the validity of theoretically sound student engagement measures and adapting it to the East Asian higher education context is encouraging (Zhoc et al., Citation2019).

Interestingly, universities in South Asia (including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) that have 18% of the global higher education student population also experience increasing student participation and diverse student cohort issues (Thirumoorthy, Citation2021; Tognatta, Citation2020). Regular assessments of student engagement in most South Asian countries lack the pace observed in Western higher education institutions. Some studies provide assessment of student engagement in South Asian countries (Siddiqui et al., Citation2019; Singh & Ningthoujam, Citation2020), but the relevant measures usually lack the foundation of a theoretically sound framework. There is, therefore, scope for greater discussion regarding the application of appropriate student engagement measures at South Asian universities (Mistry, Citation2021). Accordingly, this research focused on the challenges of measuring student engagement by investigating the question, ‘How to adapt a theoretically sound measure to define student engagement at a private university in Bangladesh, a South Asian country?’ The central research problem involved exploring how to assess and tailor a proven measure of student engagement, originally developed using proven theories in the West, to suit South Asia’s unique university environment (Bowden et al., Citation2021; Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). By addressing this research problem, this study provides knowledge that can be transferred to universities worldwide. In particular, this study provides a deeper understanding of student engagement through the use of context-specific and theoretically sound measures.

Similar to South Asian countries, the private sector of higher education in Bangladesh has grown, addressing the inadequate supply of education in public universities (Thirumoorthy, Citation2021). This growth corresponds positively to the ‘family household’ financial contribution to the children’s education in the country, which is the highest in Bangladesh among South Asian countries (UNESCO, Citation2022). Private universities in Bangladesh have several concerns that are common in the South Asian higher education context, such as an inadequate student-teacher ratio and an inability to produce employable graduates (Mistry, Citation2021; World Bank, Citation2019). At the same time, outcome-based education (OBE) policies promote the holistic assessment of student engagement in the strategies of private universities in Bangladesh (University Grants Commission Bangladesh, Citation2021). These policies reflect intent to achieve the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals related to quality and inclusive education (for example, SDG outcome 4.4 about relevant skills for decent work and SDG outcome 4.7 about education for sustainable development and global citizenship), thereby enhancing the significance of student engagement for governments and private education institutions in Bangladesh (Gómez Marcos et al., Citation2022). Hence, it is now critical that the private sector of higher education in Bangladesh operationalize student engagement with best practices that also align with the local context.

2. Literature review

2.1. Student engagement perspective

Decades ago, it became evident that student engagement functioned through the quality and quantity of student activities in academic learning (Astin, Citation1984; Pace & Kuh, Citation1998). The functioning of student engagement is related to a student’s integration into university life; for example, involvement with peers, teachers, staff, and extracurricular activities in educational institutes (Pascarella & Terenzini, Citation2005; Tinto, Citation1987). While student engagement functions in a sociocultural context, it differs in its antecedents and outcomes (Kahu, Citation2013; Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). This can be explained through multiple perspectives and frameworks, including the psychological perspective of student engagement in higher education (Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Kahu, Citation2013). From this perspective, student engagement reflects students’ internal psychosocial process of learning gains, as observed in Kahu’s (Citation2013) conceptual framework. Kahu (Citation2013) identified three components of student engagement, namely (1) affective, (2) cognitive, and (3) behavioral.

In Kahu’s (Citation2013) framework, student engagement functions through the three components mentioned above and processes the impact of structural and psychosocial influences on academic and social outcomes (Kahu, Citation2013). Accordingly, the functioning of student engagement is open to the cultural lens of the students’ and universities’ respective structural and psychosocial influencers, such as students’ family backgrounds, students’ self-efficacy, universities’ teaching practices, and societal values of the context where the university is located (Kahu, Citation2013; Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). The concept of student engagement has been influenced by the society’s orientation to cultural dimensions according to Hofstede (Morera & Galván, Citation2019), a student’s sense of autonomy as a learner (Yasmin & Sohail, Citation2018), educational background (Nahar et al., Citation2022), and context-specific problem-solving teaching practices (Loukomies et al., Citation2022) in different cultural contexts. Recent literature has identified about 15 different measures of student engagement that cater to higher education in different countries, such as Australia, Brazil, China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Portugal, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America (Trolian, Citation2023). Hence, this literature provided theoretical and empirical evidence to seek a deeper understanding of the assessment and adaptation of student engagement measures at a private university in Bangladesh.

Re-use of proven student engagement measures from the West is encouraged so that the private universities in Bangladesh can gain a holistic understanding of the concept according to the proven theories from the West (Buntins et al., Citation2021). However, proven measures cannot simply be applied as they are. Previous studies have shown the need to adapt proven measures to context-specific needs; for example, the nature of the education program or scope of engagement beyond the classroom differs in the new context (Kim et al., Citation2022; Marcionetti & Zammitti, Citation2023). There is also evidence that an adapted, theoretically sound student engagement measure allows for a comparable assessment of the concept of student engagement measures between countries in the same region (Assuncao et al., 2020).

2.2. Five-component model of student engagement

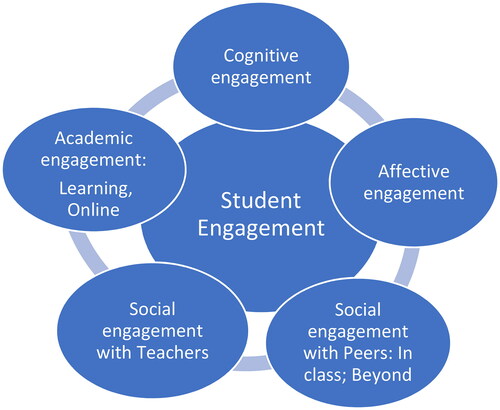

The concept of student engagement is often depicted using five-component models (Zhoc et al., Citation2019). Zhoc et al. (Citation2019) presented one such five-component student engagement model. This model was consistent with Kahu’s (Citation2013) conceptual framework of student engagement and Finn and Zimmer (Citation2012) four-component student engagement model. Value addition to the five-component model explained how academic engagement, engagement with teachers, and engagement with peers are expansions of the behavioral component. In this model, the five components of student engagement were academic, cognitive, affective, social engagement with peers, and social engagement with teachers (Zhoc et al., Citation2019). This study thus conceptualized student engagement using the five-component model. This was a rational decision as the five-component model reflected the most fine-tuned concepts of student engagement. Moreover, the model covered aspects such as social engagement with peers and class participation, which have also appeared in previous student engagement studies conducted in South Asia (Siddiqui et al., Citation2019; Singh & Ningthoujam, Citation2020).

Furthermore, the authors of this paper defined each of the five components of student engagement, benchmarking the research by Zhoc et al. (Citation2019) against other studies that widely applied student engagement measures, such as the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) measure (Indiana University School of Education, 2021; Zilvinskis et al., Citation2017), and the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI) (Assuncao et al., 2020; Sinval et al., Citation2021). At a conceptual level, the NSSE measure follows the behavioral perspective of student engagement, unlike the psychological perspective of the chosen five-component model by Zhoc et al. (Citation2019). The USEI conceptualizes student engagement as the opposite of burnout and offers contemporary elements of affective engagement. Therefore, the authors could access a broad set of items to operationalize student engagement by placing these three measures side-by-side. For example, Zhoc et al. (Citation2019) provided a broad focus on the elements of peer-to-peer engagement but missed the depth of behavioral academic engagement elements in the NSSE measure. Benchmarking the literature facilitated the addition of contemporary themes of student engagement relevant to the context of the chosen private university in Bangladesh. Below is a description and illustration () of the five components of student engagement used in this study.

2.2.1. Academic engagement

The notion that supports this component is that student engagement functions through students’ efforts to learn within a time-sensitive process (Astin, Citation1984; Kahu, Citation2013). The component consists of students’ behavioral responses regarding face-to-face classes and the use of online technologies such as Canvas, Moodle, Google Classroom, and so on for the achievement of the ‘minimum threshold level of learning’ (Zhoc et al., Citation2019, 224). The sub-component of online engagement concerns the extent of the use of online education resources, such as email, Facebook, and web-based resources (for example, MIT open courseware, Stanford online, and tools such as Padlet, Jamboard, and Prezi) for study.

2.2.2. Cognitive engagement

This component explains a student’s psychological investment for the achievement of higher-order learning (Zhoc et al., Citation2019; Zilvinskis et al., Citation2017). In line with Kahu’s (Citation2013) student engagement framework, this component is associated with deep learning, which is a state of learning in which a student draws satisfaction from an enduring commitment to intellectual challenges in the study (Indiana University School of Education, 2021; Zhoc et al., Citation2019). Examples of the indicators of this component are students’ enjoyment of intellectual challenges in the course (Zhoc et al., Citation2019), psychological investment in integrating ideas from different sources (Indiana University School of Education, 2021), and reflective learning from researching real-life problems (Indiana University School of Education, 2021).

2.2.3. Affective engagement

The foundational notion of this component is that student engagement takes shape through a student’s integration into university life (Pascarella & Terenzini, Citation2005; Tinto, Citation1987) in particular, the emotional feeling of connectedness to the educational institute ‘as a place and a set of activities worth pursuing’ (Zhoc et al., Citation2019, p. 226), and enthusiasm for belonging to student life (Kahu, Citation2013; Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). Examples of indicators in this component are the feeling of belonging to the university community (Zhoc et al., Citation2019), the feeling of enjoyment at the university campus (Zhoc et al., Citation2019), and the feeling of accomplishment for being involved in university activities, such as extracurricular activities (Assuncao et al., 2020).

2.2.4. Social engagement with peers

This component aligns with the notion that student engagement functions through academic and social integration with peers (Pascarella & Terenzini, Citation2005, Tinto, Citation1987). The component is considered ‘behavioral’ in the student engagement framework of Kahu (Kahu, Citation2013; Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018), corresponding to students’ interaction with peers. Engagement with peers at an academic level occurs in class and consists of indicators such as participation in group assignments and problem-solving with peers for course matters (Zhoc et al., Citation2019). Additional social integration with students can occur beyond the classroom, comprising indicators such as involvement in extracurricular activities with other students at the university (Zhoc et al., Citation2019).

2.2.5. Social engagement with teachers

This component acknowledges the role of a teacher in integrating a student into university life (Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018; NSSE, 2016; Pascarella & Terenzini, Citation2005; Zhoc et al., Citation2019, Kahu, Citation2013). This component materializes with the teacher’s interaction with students about matters ranging from academic learning to personal development. Examples of indicators of this component are teachers making real efforts to understand students’ difficulties (Zhoc et al., Citation2019), teachers being keen to discuss students’ progress (Zhoc et al., Citation2019), and teachers encouraging discussions about students’ personal development (Indiana University School of Education, 2021).

3. Present study setting

There are 53 public, 109 private, and 3 international universities in Bangladesh. The total number of students in tertiary level institutions in 2021 was 1.23 million (BANBEIS, 2021). Since the birth of Bangladesh in 1971, the number of universities increased from 6 to 165. The gross enrolment ratio in higher education in 2021 was quite low (20.19) compared to that in developed countries (BANBEIS, 2021). According to a 2019 World Bank report, female enrolment at the tertiary level was around 38% in Bangladesh, considerably lower than in other South Asian countries, such as India (46%) and Sri Lanka (60%) (World Bank, Citation2019). The country faces many concerns that are common in the South Asian higher education context, such as inadequate student-teacher ratios, the inability to produce employable graduates, teaching practices that promote rote learning, and insufficient research expenditure (Mistry, Citation2021; World Bank, Citation2019).

In the current study, students from postgraduate and undergraduate levels from two disciplines, the School of Business and Economics (SBE) and the School of Engineering and Physical Sciences (SEPS), participated. In any given year, the SBE and SEPS provide more than 60% of the total student cohort at the university. The selected private university sits at 1001–1200 and 215 by Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) World and Asia University rankings in 2022, respectively (QS Asian University Ranking, Citation2022; QS World University Rankings, Citation2022). This university belongs to the fee-paying private higher education sector with resource conditions and quality assurance processes superior to those of the general public education sector in South Asia (Naveed & Sutoris, Citation2020).

This university is an appropriate context for student engagement investigations for several reasons. The vision of the university is to remain a center of excellence and achieve accreditation from local professional accreditation bodies, such as the Institute of Architects (IAB), and international bodies, such as the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs (ACBSP), USA. Hence, the university conforms to national and international quality assurance standards that genuinely account for student engagement. The university also follows the OBE, which plays a crucial role in correlating its mission, educational program objectives, specific course outcomes, and overall effectiveness programs (Craig, Citation2016).

All teachers at this university have at least one postgraduate degree from universities in developed countries, and most have international teaching and related experiences. This international exposure helps academics adopt innovative teaching methods, including various combinations of lectures, assignments, class tests, workshops, presentations, case analyses, field visits, and research initiatives. Furthermore, participation in co-curricular and extra-curricular activities such as sports, cultural performance, and social services is a key tool for students’ personal development and engagement. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this university quickly shifted to different teaching platforms, such as Google Classroom and CANVAS, a technological infrastructure comparable to that of universities in Western countries. The chosen university has a context of student engagement comparable to that of Asian and global universities. Hence, this study attempted to generate learning for Asian and global universities in order to understand ‘how to adapt a theoretically sound measure to define student engagement at a private university in Bangladesh.’

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Research design

This study applied a cross-sectional survey design (Creswell, Citation2014), using an online survey to capture a snapshot of students’ perceptions of engagement and satisfaction at the chosen university. This design is consistent to that of the earlier student engagement literature (Assuncao et al, 2020; Zhoc et al., Citation2019).

4.2. Research participants

All participants were students enrolled in SBE and SEPS disciplines at the university. Among the final sample of 953 students, 592 (62.0%) and 361 (28.0%) were from the SBE and SEPS disciplines, respectively. provides the respondent profiles. Of the respondents, 34.1% were female and 65.9% were male. This was similar to the national figure, where 38.0% of the population is female and 62.0% male (World Bank, Citation2019).

Table 1. Profile of student respondents.

4.3. Data collection

The information, communication, and technology (ICT) division of the university circulated the survey via email to all eligible students for voluntary and confidential participation in the study. The survey had reached 12,438 enrolled SBE and SEPS students with active university email accounts in June 2021. In one month, 967 students responded, reflecting a response rate of approximately 8%. This survey response rate was acceptable given that the survey took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, when students were prone to fatigue with online communication. The final sample size was 953 after deleting 14 responses with more than 70% missing data.

4.4. Survey instrument

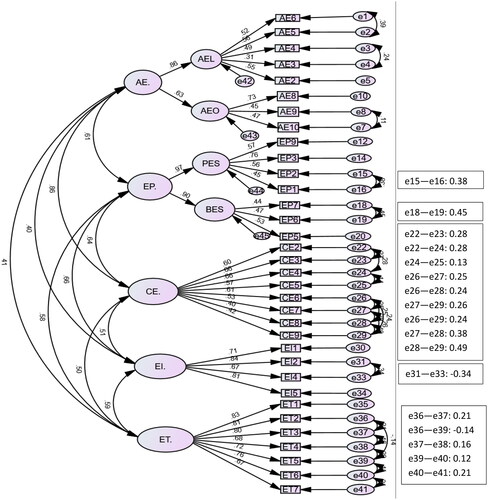

The survey covered 41 items rated on a 1–5 Likert scale. Of these, 40 items concerned a five-component measure of student engagement. The remaining items concerned students’ satisfaction with the university’s learning experience. The 40 items of student engagement were (1) academic (NSSE, 2013; Zhoc et al., Citation2019), which had ten items (refer to items AE1-10 in ); (2) cognitive (Assunção et al., Citation2019; NSSE, 2013; Zhoc et al., Citation2019), which had nine items (refer to items CE1-9 in ); (3) affective (Assunção et al., Citation2019; Zhoc et al., Citation2019), which had five items (refer to items AF1-5 in ); (4) social engagement with peers (Zhoc et al., Citation2019), which had nine items (refer to items EP1-9 in ); and (5) social engagement with teachers (NSSE, 2013; Zhoc et al., Citation2019), which had seven items (refer to items ET1-7 in ). Additionally, the survey included close-ended questions to collect students’ study and demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, family income, percentage of study completion, study discipline (SBE vs. SEPS), and level of study (undergraduate and postgraduate).

Table 2. Internal consistency of student engagement measures (SEM).

4.5. Ethical considerations

The survey circulation included a participant information sheet (PIS) according to the research protocol approved by the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/OR-NSU/IRB/1129). The PIS included the necessary information about the ethical conduct of the research. For example, participants were informed about the purpose of the survey, the self-reporting procedure, voluntary and confidential participation in the survey, the deadline to return the survey, and access to the university’s counselling support when participants became distressed while filling out the survey. Based on the approved research protocol, the online surveys returned by the participants reflected implied consent for the study.

4.6. Process of context-specific adaptation of the student engagement measure

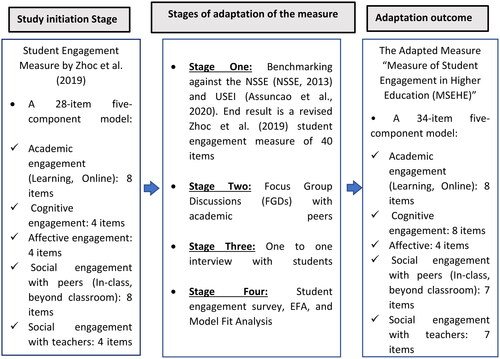

In this study, the chosen student engagement measure (Zhoc et al., Citation2019) underwent an adaptation process to arrive at a suitable measure for the research context in terms of content, language, and structure (Siddiqui & Fitzgerald, 2009; Watson et al., Citation2008). depicts an overview of the context-specific adaptation process that resulted in the measure of student engagement in higher education, that is, the MSEHE. As shown in the ‘study initiation stage’ box (), the adaptation process began with a 28-item pool that was drawn from Zhoc et al. (Citation2019) five-component student engagement model. Each stage in the adaptation process was designed to enhance the validity of the research outcome, particularly, the adapted measure of student engagement, that is, the MSEHE.

4.6.1. Validity

In stage one (), the benchmarking exercise involving Zhoc et al. (Citation2019) measure, the NSSE (NSSE, 2016), and USEI (Assunção et al., Citation2019), were conducted by the four authors of this study, each with a minimum of five years of teaching experience at the selected university. This exercise provided subject experts’ reviews to enhance the content validity of the adapted measure. That is, the measure was checked for coverage of the required subject matter in the student engagement domains (Coates, Citation2008).

Stage two () involved conducting focus group discussions (FGDs) with other academics with a minimum of two years of teaching experience at the selected university. Thirty academics, including nineteen males and 11 females, participated in the FGDs, discussing how a measure should have a certain language and structure to capture the domains of student engagement at the selected university. Stage three () covered consultations with seven students in a one-to-one in-depth interview to assess whether the measure had a suitable structure and language to capture student engagement. The research team recruited students from SBE and SEPS on a convenience basis. All the participants participated in the FGDs and interviews on a voluntary basis. The completion of stages two and three enhanced the face validity of the adapted measure, that is, the measure’s practical appearance to the targeted users regarding the assessment of student engagement (Kemper, Citation2020).

Stage four () involved surveying the updated measures with students, analyzing the survey data for exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and structural equation modelling. Both tests checked for aspects of construct validity (Ginty, Citation2013) of the adapted measure. Factor analysis was used to explore the relationship between each of the five components of the student engagement model. This involved running the principal component option in SPSS (version 28), forcing the relevant items into a single fixed factor, as identified in the benchmarking exercise in stage one. That is, the EFA explored five factors according to the five-component student engagement model (refer to Section 2), with ten items in academic engagement, nine items in cognitive engagement, five items in affective engagement, nine items in social engagement with peers, and seven items in social engagement with teachers.

The final task in stage four of the adaptation process was structural equation modelling for model fit analysis in the Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) software. This analysis examined whether the actual data of the 37-item measure supported a multidimensional model of student engagement consisting of interrelated components of academic, cognitive, affective, and social engagement with teachers and peers (Ginty, Citation2013).

4.7. Data analysis

This study applied three main analyses to assess the strengths of the adapted measures. First, as shown in , each of the five updated components of the 34-item student engagement measure (i.e. MSEHE) was assessed for internal consistency using SPSS (Version 28). The test assessed the components to be reliably consistent if the coefficient value of Cronbach’s standardized alpha (CSA) was at least 0.7 (Civelek, Citation2018) ( and ). Furthermore, the five components of the MSEHE were checked for associations between components using a two-tailed Pearson correlation test (). Additionally, a hierarchical regression analysis was used to assess whether the five updated components of student engagement could predict student satisfaction ().

Table 3. The fit indices of the student engagement measure.

Table 4. Correlations between the five components of MSEHE.

Table 5. Hierarchical regression of MSEHE components on student satisfaction.

Hierarchical regression involved two models with two blocks of independent variables. Model 1 () tested how student demographics and study characteristics (i.e. age, gender, family income, percentage of study completion, study discipline of SBE vs. SEPS, and undergraduate and postgraduate levels of study) predicted student satisfaction. Model 2 () tested how the five updated student engagement components, in addition to the student characteristics in the first model, could predict student satisfaction. The movement of the adjusted R2 and F between the two models clarified how the student engagement components could predict student satisfaction despite the influence of student characteristics.

5. Results

5.1. The 34-item MSEHE

provides the item description, number of items, CSA score, and items dropped from and added to the adapted MSEHE measure. At the end of stage one, Zhoc et al. (Citation2019) 28-item student engagement scale was expanded to 40. For example, the authors broadened the sub-component of academic engagement learning with items about asking questions in class and participating in class presentations (e.g. items AE5 and AE6 in ) (NSSE, 2013). Similarly, the component of cognitive engagement was expanded by items on intellectual stimulation and integration of ideas from real-life problems (e.g. items CE6 and CE9 in ) (NSSE, 2013). These items were associated with higher-order cognitive and workplace-relevant skills, which are reportedly lacking among university graduates in Bangladesh (World Bank, Citation2019).

At the end of the FGD with academic peers (stage two in ), the authors updated the measure with certain language adaptations. For example, the term ‘academic’ was changed to ‘faculty member’ to align with the language used by academics and students at the selected university. The academic peers also discussed how student class attendance is an area needing improvement and should be well captured in the student engagement measure. During interviews with students (Stage three in ), the students suggested modifying the content of certain items or adding clarification texts for a better understanding of the items. For example, an item in the component of social engagement with peers inquired about students’ interest in extracurricular activities. This item was rephrased to reflect students’ interest in supporting peers by attending the university’s extracurricular activities.

During the EFA analysis (Stage four in ), all items, except item four, were found to group in the respective component with a minimum factor loading of 0.4 and above (J. Hair et al., Citation2006). The authors dropped these items from the measure, except for the item ‘I rarely skip classes’ (Item AE3 in ). This item is theoretically relevant to academic learning (Astin, Citation1984; Zhoc et al., Citation2019) and was identified as an area needing improvement by university academic peers (Stage two in ). The excluded items were listed as AE1, CE1and EP8 . Following this task, the number of items in the student engagement measure decreased to 37.

During structural equation modelling (Stage four in ), the initial results showed a lower value of model indices; for example, the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) were below 0.9 (Bentler, Citation1990). Moreover, the output of the modification indices (MI) confirmed that a few items contributed to high error variances. Adjustments to the model were made by establishing covariance between items with high MI values that belonged to the same component as student engagement (Bentler, Citation1990; Civelek, Citation2018). Furthermore, three items (AE7, EP4, and AF3 in ) with high MI values were identified as redundant and excluded from the measure. A consultation among the authors concluded that these were non-essential items for the conceptualization of student engagement at this university. The first item about using social media to contact peers may not be considered an academic task. The model still had more items with a high error variance, but the authors did not find any other items to be non-essential. Accordingly, further fine-tuning of error variance in the model has not yet been attempted.

Upon completion of the four-stage adaptation process (), the authors arrived at the outcomes of the MSEHE. That is, a 34-item, five-component model with a stable factorial structure defined student engagement at university.

5.2. Strength of MSEHE

The CSA values for cognitive, affective, and social engagement with teachers were higher than 0.8 (), which indicates that these three components are internally consistent (Civelek, Citation2018). On the other hand, the CSA values for the subcomponents of academic engagement and peer engagement beyond the classroom were lower than the recommended cutoff point (0.7 for internal consistency) (Civelek, Citation2018).

reports the model fit analyses of the MSEHE. This result is tenable with the RMSEA value less than 0.8 and CFI and NNFI values above 0.9 (Bentler & Bonett, Citation1980; Civelek, Citation2018). This confirms that the concept of student engagement at the studied university is defined by the components of academic, cognitive, affective, social engagement with peers, and social engagement with teachers. As shown in , the MSEHE has item-wise factor loadings between 0.31 and 0.84.

shows that each of the five MSEHE components was significantly and positively interrelated. The top four high-level associations were noted between the sub-components of peer engagement (r = 0.49, p < .01), affective engagement, and social engagement with teachers and peers (r = 0.49, p < .01), and between academic engagement learning and cognitive engagement (r = 0.48, p < .01). Cognitive engagement had a moderate level of association with all other components of student engagement (Cohen, Citation1988).

presents the results of hierarchical regression analysis. In Model 2, as the components and subcomponents of student engagement were added, the explanation of the variance in student satisfaction increased to 52.5%. There was a statistically significant increase in F-value (149.4; p<.001) and adjusted R2 (0.3% to 52.5%) from Model 1 to Model 2. Furthermore, the components of cognitive, affective, and social engagement with teachers were significant predictors of student satisfaction, irrespective of the students’ demographic, and study characteristics. Of these three components, the highest levels of influence came from social engagement with teachers (t-value = 15, p < 0.001) and affective engagement (t-value = 14.5, p < 0.001). Students scored their level of social engagement with teachers as having the lowest mean value (3.3 out of 5). In the component of engagement with peers, only the subcomponent of peer engagement beyond the classroom was a significant but negatively associated predictor of student satisfaction (t-value = −3.3; p = 0.001).

6. Discussion

Following the widely accepted psychological perspective of engagement through a five-component model (Kahu, Citation2013; Zhoc et al., Citation2019), this study defined student engagement at a private university in Bangladesh. This study arrived at a contextually suitable student engagement measure, namely the MSEHE, which includes the domains of academic, cognitive, affective, and social engagement with teachers, and social engagement with peers.

In this study, the adaptation process of the student engagement measure consisted of certain common procedures like those used in previous relevant studies (Marcionetti & Zammitti, Citation2023; Mistry, Citation2021; Zhoc et al., Citation2019). A statistical analysis of the psychometric properties was conducted to confirm the validity of the measure, which was similar to that used in previous studies. Additionally, this study has applied several innovative procedures during the adaptation process, such as prioritisation of endorsement of academics at the university studied. For example, an item on students not skipping classes was retained in the measure despite not having an acceptable factor loading. This decision was justified because academics in the research context endorse this item as critical to improving learning.

The findings confirmed a satisfactory model fit for the MSEHE and identified the interdependency between the five student engagement domains. The MSEHE had item-wise factor loadings ranging from 0.31 to 0.84, and domain-wise CSA scores between 0.61 and 0.91. These findings correspond to those of previous studies of the adapted student engagement measure by Zhoc et al. (Citation2019) in East Asian and European higher education contexts (Marcionetti & Zammitti, Citation2023; Zhoc et al., Citation2019). It is notable that the factor loading of a specific academic engagement item, ‘I rarely skip classes,’ was reported at 0.31, 0.42, and 0.48 in this study and in those conducted in East Asian and European higher education, respectively (Marcionetti & Zammitti, Citation2023; Zhoc et al., Citation2019). Cognitive, affective, and social engagement with teachers were found to be positively associated with and predictive of student satisfaction. By contrast, Zhoc et al. (Citation2019) found that all five domains of student engagement were positively associated with and predictive of satisfaction.

6.1. Implications

The findings of this study imply that the context-specific adaptation of a theoretically sound measure provides a pragmatic understanding of student engagement. The MSEHE shares the same theoretical underpinnings as the five-component student engagement measures applied in previous studies (Marcionetti & Zammitti, Citation2023; Zhoc et al., Citation2019). However, in Bangladesh, the composition of certain domains in the MSEHE has been shaped differently. For example, the academic engagement domain in MSEHE includes contemporary practices, such as students asking questions in class and participating in class presentations. Similarly, the cognitive engagement domain in the MSEHE covers additional concepts related to student motivation for research and connecting their studies to societal issues. Through these domains, MSEHE has the potential to address unique challenges in the Bangladeshi education context, such as rote learning teaching practices and the lack of graduates with employability skills (World Bank, Citation2019).

Another implication of this study is that the domains of student engagement are avenues for achievement of student satisfaction. It is possible that, in some contexts, certain domains of student engagement may not be as influential as others. In this study, only three of the five domains of student engagement (affective, cognitive, and social engagement with teachers) were significantly associated with student satisfaction. However, as the five domains of student engagement are interdependent, universities must maintain a positive stance in all domains to capture the holistic learning of students (Evans et al., Citation2018, Cassidy et al., Citation2021). This clarifies that universities in Bangladesh, with similar student demographics and study disciplines as those of the study university, should simultaneously work on multiple domains of student engagement for effective and positive results in engaging students.

Interestingly, this study found that academic engagement and engagement with peers in class did not influence student satisfaction. This could be related to the relatively low factorial stability of certain items such as the academic engagement item about class attendance and the social engagement items about working with peers regarding course problems. Previous studies have reported low factorial stability for certain academic engagement items, such as students’ class attendance and the timely completion of assessments (Assuncao et al, 2020; Marcionetti & Zammitti, Citation2023; Zhoc et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, there is evidence that academic and social engagement is subject to students’ gender and ethnicity (Kinzie et al., Citation2007; Trolian, Citation2023). All these imply that there is room for greater understanding of the concepts and functions of academic engagement and social engagement with peers. Future study about how these two domains in the MSEHE operate in a male-dominant student cohort in Bangladesh, as opposed to female-dominant student cohorts in the Western education context (Universities Australia, Citation2019), could uncover insights into student engagement and gender equity in higher education contexts. Moreover, this study can generate interest for future studies about what barriers exist in the practise of these domains in the Bangladeshi private university context.

6.2. Recommendations

Based on the findings and implications stated above, it is recommended that higher education in Bangladesh prioritizes the effective understanding, measurement, and practices of student engagement. Otherwise, it will be difficult for the university under study and other similar universities to offer either holistic learning to students (Cassidy et al., Citation2021; Evans et al., Citation2018) or move effectively towards OBE (Thirumoorthy, Citation2021).

Academics should plan teaching interventions that offer holistic learning to students by focusing on the five domains of student engagement. For example, educators could plan a group assessment that covers an intellectually stimulating topic for students (cognitive and social engagement with peers), which is well discussed inside class (academic and social engagement with teacher) and can be conducted in the university campus environment (affective engagement).

Policymakers promoting OBE in higher education in Bangladesh would also benefit from tracking the outcomes associated with the five domains in MSEHE. This tracking can occur in various ways, including promoting the regular assessment of student engagement domains in MSEHE. Additionally, there should be adequate resources to support student engagement practices, particularly as educational institutions in Bangladesh and South Asia struggle to maintain an appropriate student-teacher ratio (Mistry, Citation2021; World Bank, Citation2019). The authors of this paper note that the domain of social engagement with teachers now entails deeper concepts, such as students’ desire for teachers to take interest in their personal development. Accordingly, universities in Bangladesh, as well as South Asia, will need to rigorously manage the resource situation to facilitate appropriate social engagement between teachers and students.

6.3. Limitations

The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic when the university campus was inaccessible, and all classes were conducted online. It is likely that the pandemic has impacted students’ perceptions of student engagement, particularly in areas of engagement with teachers and peers, both inside and outside the classroom. However, this study did not attempt to distinguish between the impact of the pandemic and the students’ perceptions. The authors of this paper would encourage future studies on whether the conceptualization of student engagement should have different components during a crisis environment like COVID-19.

The other limitation of the study is that data were collected through a self-report survey from a private university in Bangladesh, covering only two disciplines and a sample size corresponding to an 8% response rate. It could be possible that the five domains of student engagement evident in this study only apply to students from disciplines of the SBE and SEPS. Accordingly, readers should be cautioned to carefully apply the findings of this study to similar educational contexts, study disciplines, and student cohorts. Investigating student engagement at a single university may be preferred to avoid too simplistic generalization of the concept (Kahu, Citation2013). However, it would be beneficial to assess the stability of the updated five-component model of student engagement proposed in this study through future studies with broader coverage of study disciplines and larger student sample sizes at a university.

7. Conclusion

This study adopted a theoretically sound measure to define domains of student engagement at a private university in Bangladesh. A systematic adaptation process was shown to lead to a context-suitable measure to facilitate improved student engagement at the study university. To the best of our knowledge, such scholarly exercises at a private university in Bangladesh have not been previously reported. This study highlights that, while the theory of student engagement in higher education can be conceptualised with some common components (such as academic, cognitive, affective, and social engagement with peers and teachers), the construct of each domain of student engagement needs to be context-specific. The proposed measure of student engagement (i.e. MSEHE) in this study covers contextually suitable aspects, such as high-impact learning through class presentations and researching societal issues of concern. Thus, MSEHE reflects the amended five domains of student engagement, which can guide universities in addressing the need for engaging students and having employable graduates in Bangladesh.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nazlee Siddiqui

Nazlee Siddiqui is an Adjunct Associate Professor of the Department of Management at North South University. She has an extensive portfolio of services management research, inclusive of $3 million worth of collaborative grant with State and Federal Australian health bodies and more than 750 citations on Google Scholar and peer-reviewed publications. Nazlee has more than 15 years of university teaching experience in Australia and Bangladesh. In 2018, she received a University of Tasmania teaching merit certificate for the application of teaching philosophy in industry-relevant education.

Nazmun Nahar

Nazmun Nahar is the Director of the Institutional Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) of North South University (NSU) since its inception in 2016 and a member of the National Program Review Team formed by the Bangladesh Accreditation Council. She is also a Professor of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at NSU. Dr. Nahar is a fellow of the Institution of Engineers, Bangladesh (IEB), with a specialization in integrated stormwater management, watershed planning, and design of Best Management Practices (BMP) and Low Impact Development (LID) measures. She has over 20 years of experience in research, industry, and academia.

Mohammad Sahadet Hossain

Mohammad Sahadet Hossain is currently the Chairman and Professor at the Department of Mathematics and Physics of North South University (NSU). Dr. Hossain was the founding Additional Director (2016–2019) and later the Coordinator of IQAC at NSU. He is a member of the Core Team of the local program review committee formed by the Quality Assurance Unit (QAU) of UGC, Bangladesh. Dr. Hossain is a researcher in the field of control theory and model reduction, a very renowned field of engineering, mathematics, and application. He worked at the International Max Planck Institute for Dynamics of Complex Technical Systems at Magdeburg, Germany as a Postdoc research scientist.

Ahmed Tazmeen

Ahmed Tazmeen is an Associate Professor in the Department of Economics of North South University (NSU) and the immediate past chairman of the department. He was the founding Additional Director and later Coordinator of the Institutional Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) of NSU. Since May 2019, he has been serving as the national consultant of the International Labour Organization (ILO)’s Skills 21 team that is drafting the Bangladesh National Qualifications Framework (BNQF) involving all the sectors of education in Bangladesh. Dr. Tazmeen holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Manitoba (U of M), Canada. He is certified by the U of M as a teacher of higher education and was given a teaching excellence award by the same university. Dr. Tazmeen is currently serving as the Registrar of NSU.

Khawaja Sazzad Ali

Khawaja Sazzad Ali is a current Master of Science in Economics student at North South University. He previously completed his Bachelor’s degree in business administration, majoring in Finance and Marketing. His focus lies in leveraging economic models and statistical techniques to analyze complex systems and develop evidence-based policies for sustainable growth. His research areas include applied econometrics, development economics, and behavioral economics.

References

- Assunção, H., Lin, S.-W., Sit, P.-S., Cheung, K.-C., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Smith, T., Maloa, B., Campos, J. Á. D. B., Ilic, I. S., Esposito, G., Francesca, F. M., & Marôco, J. (2019). University student engagement inventory (USEI): Transcultural validity evidence across four continents. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2796–2796. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02796

- Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 25(4), 297–308.

- Bangladesh Education Statistics. (2021). Bangladesh bureau of educational information and statistics (BANBEIS), Ministry of Education, April 2022.

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

- Bowden, J. L.-H., Tickle, L., & Naumann, K. (2021). The four pillars of tertiary student engagement and success: A holistic measurement approach. Studies in Higher Education, 46(6), 1207–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1672647

- Buntins, K., Kerres, M., & Heinemann, A. (2021). A scoping review of research instruments for measuring student engagement: In need for convergence. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 2, 100099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100099

- Cassidy, K. J., Sullivan, M. N., & Radnor, Z. J. (2021). Using insights from (Public) services management to improve student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 46(6), 1190–1206. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1665010

- Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer.

- Civelek, M. E. (2018). Essentials of structural equation modeling. Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska.

- Coates, H. (2008). Attracting, engaging and retaining: New conversations about learning.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Academic.

- Craig, R. (2016). Promoting student engagement through outcomes-based education in an EAL environment. International Journal for 21 Century Education, 3(2), 49–59.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

- Evans, C., Kandiko Howson, C., & Forsythe, A. (2018). "Making sense of learning gain in higher education higher. Education." Higher Education Pedagogies, 3(1), 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2018.1508360

- Ewell, P. T., & McCormick, A. C. (2020). The National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) at twenty. Assessment Update, 32(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/au.30204

- Finn, J. D., & Zimmer, K. S. (2012). Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer.

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

- Ginty, A. T. (2013). Construct validity. In M. D. Gellman and J. R. Turner (Eds.),” Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 487–487). Springer.

- Gómez Marcos, M., Ruiz Toledo, M., & Ruff Escobar, C. (2022). Towards inclusive higher education: A multivariate analysis of social and gender inequalities. Societies, 12(6), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060184

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hou (Angela), Y. C., Morse, R., Ince, M., Chen, H. J., Chiang, C. L., & Chan, Y. (2015). Is the Asian quality assurance system for higher education going glonacal? Assessing the impact of three types of program accreditation on Taiwanese universities. Studies in Higher Education, 40(1), 83–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.818638

- Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505

- Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197

- Kemper, C. J. (2020). Face validity. In Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K. (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of personality and individual differences. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_1304

- Kim, S. Y., Westine, C., Wu, T., & Maher, D. (2022). Validation of the higher education student engagement scale in use for program evaluation. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/15210251221120908

- Kinzie, J. L., Thomas, A. D., Palmer, M. M., Umbach, P. D., & Kuh, G. D. (2007). Women students at coeducational and women’s colleges: How do their experiences compare? Journal of College Student Development, 48(2), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2007.0015

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, University Press.

- Loukomies, A., Petersen, N., Ramsaroop, S., Henning, E., & Lavonen, J. (2022). Student teachers’ situational engagement during teaching practise in Finland and South Africa. The Teacher Educator, 57(3), 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2021.1991539

- Marcionetti, J., & Zammitti, A. (2023). Italian higher education student engagement scale (I-HESES): Initial validation and psychometric evidences. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2023.2241031

- Mistry, J. (2021). The construct validity of student engagement in selected Indian business schools: A confirmatory factor analysis approach. SN Social Sciences, 1(12), 292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00298-0

- Moges, B. T., Assefa, Y., Tilwani, S. A., Azmera, Y. A., & Aynalem, W. B. (2023). Psychosocial role of social media use within the learning environment: Does it mediate student engagement? Cogent Education, 10(2), 2276450. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2276450

- Morera, I., & Galván, C. (2019). Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in the educational context. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The value of education and health for a global, transcultural world. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (vol. 60., pp. 298–306). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.38

- Nahar, N., Siddiqui, N., Hossain, M. S., Tazmeen, A., & Ali, K. S. (2022). Path to outcome based higher education in Bangladesh: An analysis of student engagement and socio-demographic factors [Paper presentation]. IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Tunis & Tunisia. pp. 344–350, https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON52537.2022.9766558

- Naveed, A., & Sutoris, P. (2020). Poverty and education in South Asia. In P. M. Sarangapani and R. Pappu (Eds.), Handbook of education systems in South Asia. (pp. 1–23). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3309-5_33-1

- Pace, C. R., & Kuh, G. D. (1998). College student experiences questionnaire:” CSEQ. Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research and Planning, School of Education.

- Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research.," Vol. 2. Jossey-Bass, an Imprint of Wiley.

- QS World Asia University Rankings. (2022). QS Asia University Rankings. Retrieved from https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/asian-university-rankings/2022

- QS World University Rankings. (2022). QS top universities. Retrieved from https://www.topuniversities.com/qs-world-university-rankings

- Rowan, A., & Neves, J. (2021). UK engagement survey 2021. AdvanceHE.

- Sharif Nia, H., Marôco, J., She, L., Khoshnavay Fomani, F., Rahmatpour, P., Stepanovic Ilic, I., Mohammad Ibrahim, M., Muhammad Ibrahim, F., Narula, S., Esposito, G., Gorgulu, O., Naghavi, N., Pahlevan Sharif, S., Allen, K.-A., Kaveh, O., & Reardon, J. (2023). Student satisfaction and academic efficacy during online learning with the mediating effect of student engagement: A multi-country study. PLoS One, 18(10), e0285315. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285315

- Siddiqui, N., Miah, K., & Ahmad, A. (2019). Peer to peer synchronous interaction and student engagement: A perspective of postgraduate management students in a developing country. American Journal of Educational Research, 7(7), 491–498. ISSN 2327-6126 (2019) https://doi.org/10.12691/education-7-7-9

- Singh, T., & Ningthoujam, S. (2020). Precursors of student engagement in Indian Milieu. Theoretical Economics Letters, 10(01), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2020.101007

- Sinval, J., Casanova, J. R., Marôco, J., & Almeida, L. S. (2021). University student engagement inventory (USEI): Psychometric properties. Current Psychology, 40(4), 1608–1620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0082-6

- Thirumoorthy, G. (2021). Outcome based education is need of the hour. International Journal of Research -GRANTHAALAYAH, 9(4), 571–582. https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v9.i4.2021.3882

- Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. The University of Chicago Press.

- Tognatta, N. (2020). COVID-19 impact on tertiary education in South Asia. COVID-19 coronovirus response. World Bank Group. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/150411590701072157/COVID-19-Impact-on-Tertiary-Education-in-South-Asia.pdf

- Trolian, T. (2023). Student engagement in higher education: Conceptualizations, measurement, and research, 1–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32186-3_6-1

- UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report. (2022). “South Asia: Non-state actors in education: Who chooses? Who loses?” https://www.unesco.org/gem-report/en/articles/private-education-has-grown-faster-south-asia-any-other-region-world-report-shows.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2018). Education data, UIS database. http://data.uis.unesco.org/. [Accessed 12 September 2022]

- Universities Australia. (2019). Higher education: Facts and figures. Retrieved from https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/190716-Facts-and-Figures-2019-Final-v2.pdf

- University Grants Commision. (2021). Strategic plan for higher education in Bangladesh: 2018–2030. Available at: http://www.ugc.gov.bd/en [Accessed 3 December 2021].

- Watson, D., O'Hara, M. W., Chmielewski, M., McDade-Montez, E. A., Koffel, E., Naragon, K., & Stuart, S. (2008). Further validation of the IDAS: Evidence of convergent, discriminant, criterion, and incremental validity. Psychological Assessment, 20(3), 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012570

- World Bank. (2019). Bangladesh tertiary education sector review 2019. (AUS0000659). The World Bank Publications, the World Bank Group.

- World Bank. (2019). Graduate employability of affiliated colleges - New evidence from Bangladesh: Graduate tracking survey on affiliated colleges of Bangladesh National University. (AUS0000633). The World Bank Publications, the World Bank Group.

- Xu, X., Rose, H., & Oancea, A. (2021). Incentivising international publications: Institutional policymaking in Chinese higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 46(6), 1132–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1672646

- Yasmin, M., & Sohail, A. (2018). Socio-cultural barriers in promoting learner autonomy in Pakistani Universities: English teachers’ beliefs. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1501888. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1501888

- Zheng, J. J., & Kapoor, D. (2021). State formation and higher education (HE) policy: An analytical review of policy shifts and the internationalization of higher education (IHE) in China between 1949 and 2019. Higher Education, 81(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00517-2

- Zhoc, K. C. H., Webster, B. J., King, R. B., Li, J. C. H., & Chung, T. S. H. (2019). Higher education student engagement scale (HESES): Development and psychometric evidence. Research in Higher Education, 60(2), 219–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9510-6

- Zilvinskis, J., Masseria, A. A., & Pike, G. R. (2017). Student engagement and student learning: Examining the convergent and discriminant validity of the revised national survey of student engagement. Research in Higher Education, 58(8), 880–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9450-6