Abstract

We present lessons learned from conducting a limited pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an indigenously developed positive psychology intervention. This RCT essentially examines the efficacy of a competencies enhancing Internet-delivered intervention for Indian students. A total of 212 participants signed up for the semi-automated, text-based and self-guided program and filled program relevant competency measures (viz. emotional intelligence, stress, time and self-management) at pre-assessment and post-assessment. Results suggest that student participants (n = 75) randomly allocated to the experimental group of the trial have improved competencies of emotional intelligence, time, stress and self-management at post-test in comparison to the ones allocated to placebo (n = 56) and control conditions (n = 46). We deliberately used paired sample t-tests to check for significant differences in each of the components before and after the intervention. Our attrition rate was ranging from 21% to 59%, whereas the adherence rate was ranging from 35% to 48% for the four-phased process. Contrarily, the attrition rate for placebo (16%) and control groups (8%) were considerably low as compared to the experimental group. Overall, despite variable effect sizes, the prototypical psycho-educational program appeared feasible for enhancing students’ well-being in an Indian context.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The field of Internet and mobile-based interventions is a relatively new domain and studies utilizing the power of these technologies are limited to the Western world. As such, the Internet or mobile application-based interventions have been an unexplored phenomenon in the eastern countries, especially the South-Asian region, including India. Most of the available studies have used these technologies as the medium to prevent and treat clinical pathologies and a section of such attempts has also focused on well-being promotion and enhancement. In fact, this pioneering attempt present lessons learned from conceptualizing a wellness promotion intervention in the Indian milieu and it essentially demonstrates how to design and deliver culturally ubiquitous Internet-based interventions. Obviously, it aims to further motivate researchers to explore this domain in an ever-progressing digital age and simultaneously lay foundation for electronic Health (eHealth) and mobile Health (mHealth) in South Asian region with an exclusive focus on the Indian subcontinent.

1. Introduction

Internet as a delivery modality claim to have the potential for unmatched impact on the conduct of empirical psychological research and it has revolutionized the whole paradigm of online behavioural sciences (Calvo, Vella-Brodrick, Desmet, & Ryan, Citation2016; Christensen & Griffiths, Citation2002; Gosling & Johnson, Citation2010; Kraut et al., Citation2004). A plethora of research in terms of such psychological paradigms, typically targeting mental or behavioural health problems have had accumulated a great deal of knowledge about the science and practice of Internet interventions (e.g. Amichai-Hamburger, Citation2008; Ritterband & Tate, Citation2009). On a closer inspection, a majority of constructs dominating the field of web-based interventions belong to the domain of clinical psychology involving clinical population (see Ebert, Cuijpers, Muñoz, & Baumeister, Citation2017 for a review). Indeed, this has resulted in an expansion of literature on various pathological symptoms; their diagnosis, prevention, and treatment (see Portnoy, Scott-Sheldon, Johnson, & Carey, Citation2008 for a meta-analysis). Besides, many reviews of the existing literature on Internet interventions highlight the significance, success, and utilization of Internet/ICT in delivering large-scale, pervasive and cost-effective mental health services (Drigas, Koukianakis, & Papagerasimou, Citation2011; Ritterband et al., Citation2003).

In contrast, the area of “well-being” or “wellness” promotion is less explored and to some extent limited research in this domain has thwarted the growth prospects of positive psychological interventions (see Bolier et al., Citation2013; Sin & Lyubomirsky, Citation2009 for a meta-analysis). Of all the significant wellness promotion attempts, a pioneering Internet-based positive psychological study by Seligman, Steen, Park, and Peterson (Citation2005) has captured the essence of wellness promotion among non-clinical population. Schueller and Parks (Citation2012) replicated Seligman et al.’s (Citation2005) study again in the United States to validate their method of dissemination. Mongrain and Anselmo-Matthews (Citation2012) in yet another replication have concluded that increasing the number of strategies or theoretical constructs tend to increase usage (and practice) of program exercises by research participants. Furthermore, another prominent study in the Australian context is an extension of Seligman et al.’s (Citation2005) study, wherein Mitchell, Stanimirovic, Klein, and Vella-Brodrick (Citation2009) emulate their most effective 1-week intervention to create a three-week web-based intervention. Mitchell et al.’s (Citation2009) study found significant improvement in using your strengths group for the cognitive component of subjective well-being. Overall, in addition to these phenomenal studies, some recent studies highlight the success and significance of web-based interventional attempts without having any emphasis on cultural ubiquity (e.g. Eysenbach, Vella-Brodrick, Grohol, & Manicavasagar, Citation2014; Kushlev et al., Citation2018; Miller & Duncan, Citation2015; Proyer, Wellenzohn, Gander, & Ruch, Citation2015; Yarosh & Schueller, Citation2017). It should also be noted that none of the wellness promotion interventions utilizing non-clinical population claims or even highlight the idea of cultural ubiquitousness in a sense that adapting or replicating these studies would bring anticipated outcomes in different cultures.

Although the term “well-being” or “wellness” bear a similar connotation, literature suggests that well-being is a multidimensional construct and relates to several components ranging from subjective, psychological, social, cognitive, economic to intrapersonal and interpersonal factors (cf. Myers et al., Citation2017; O’Connell, O’Shea, & Gallagher, Citation2015). In a way this relationship further informs the field of theory-inspired psychological interventions, which aims to eventually promote wellness (Lippke & Ziegelmann, Citation2008; Maddux, Citation2008). Importantly, wellness or well-being promotion agenda put forth strong emphasis on practicing Cognito-behavioural tasks pertaining to chosen intentional activities (cf. Layous, Citation2018), which then act as an effective mechanism to raise well-being levels or wellness (e.g. Cohn & Fredrickson, Citation2010; Mazzucchelli, Kane, & Rees, Citation2010). Research suggests that the ultimate goal of all interventional agenda is to enhance the state of being while attempting to create positive change and or improve/enhance knowledge; ability, awareness, and understanding (see Barak, Klein, & Proudfoot, Citation2009). Owing to this reasoning, we use “well-being” and “wellness” interchangeably for our wellness promotion study, which may eventually translate well in other cultures.

2. The current study

Although very few interventional attempts emphasize the notion of cultural appropriateness (Layous, Lee, Choi, & Lyubomirsky, Citation2013), there is an obvious need of studies that possess cultural ubiquity and the ability to enable diverse ethnic groups (cf. Recabarren, Nussbaum, & Leiva, Citation2007). Regarding the current study, we do not resort to replicate the interventional attempts but make an active effort over and above to corroborate the implied understanding of web-based well-being or wellness promotion interventions. Apparently, this has been done a priori via active manipulation of context relevant variables while following a more or less similar methodological approach (see Davies, Morriss, & Glazebrook, Citation2014 for a meta-analysis). We adopt a mixed approach to conceptualize the program herein referred to as “Student Well-being Enhancement Program” [SWBEPFootnote1] (Singh & Choubisa, Citation2009).

In order to formulate and rationalize SWBEP, we intentionally chose highly effective strategies from a bunch of competencies that have shown proven credibility to enhance emotions and well-being, especially time management (e.g. Hoff Macan, Citation1994; Mancini, Citation2003; Woolfolk & Woolfolk, Citation1986), stress management (e.g. see Regehr, Glancy, & Pitts, Citation2012 for a review; Anstead, Citation2009; Bughi, Sumcad, & Bughi, Citation2006; Chiauzzi, Brevard, Thurn, Decembrele, & Lord, Citation2008; Eisen, Allen, Bollash, & Pescatello, Citation2008), emotional intelligence (e.g. Misra & McKean, Citation2000; Nelson, Low, & Vela, Citation2003) and self-management (e.g. Arensman et al., Citation2015; Kremers, Steverink, Albersnagel, & Slaets, Citation2006). In fact, all the four components taken for this study correspond to the major components of Emotional Skills Assessment Process (ESAP) model of college success (Nelson et al., Citation2003). Technically, the components of the ESAP model have shown empirical linkages to academic performance, health, achievement and well-being (both hedonic and eudemonic). Besides, the chosen components are also considered very relevant and their underlying mechanisms have shown to play significant role in enhancing well-being or wellness of the participants in different cultural contexts (cf. Eldeleklioglu, Yilmaz, & Guletkin, Citation2010; Macan, Shahani, Dipboye, & Phillips, Citation1990; Misra & McKean, Citation2000; Nonis, Hudson, Logan, & Ford, Citation1998). The selection of these components is further justified considering their perceived benefits and impact on both clinical as well as non-clinical samples.

Also, these components are found to be specifically relevant to the Indian students’ lives and have been extracted and tested in a classroom setting with a non-clinical student sample (see Singh & Choubisa, Citation2009). We schematically utilize the implied techniques (cf. Table ) for transforming the chosen components into an online, stepwise, text-based psycho-educational program containing simple offline and online exercises (see Choubisa, Citation2011 for details; Ajzen, Citation2006; Choubisa & Singh, Citation2011; Magyar-Moe, Citation2009; Mitchell, Vella-Brodrick, & Klein, Citation2010). Following which, it is hypothesized that a multicomponent intervention program might have a positive impact on the wellness or well-being levels of college students in a higher education scenario (see Papadatou-Pastou, Goozee, Payne, Barrable, & Tzotzoli, Citation2017 for a review).

Table 1. Module components and the relevant skills and techniques used for web transformation

Specifically, the rationale behind choosing college students’ as the target group is the fact that the student population is the most easily sought, most active on the Internet and constitutes a highly vulnerable population group (see Fusilier, Durlabhji, Cucchi, & Collins, Citation2005). The reason behind this might be the fact that the college student population desires to keep themselves abreast in their social networks, they use the Internet most often and consequently, they are more amenable to change in any direction (see Fusilier & Durlabhji, Citation2005). Additionally, it should also be noted that despite the presence of more than 462 million Internet users (with 34.8% penetration) in India (internetlivestats, 2016), no concrete evidence is available in terms of electronic health (eHealth) and mental health programs (illness prevention and wellness promotion viewpoints) in a developing milieu (for comparisons) and particularly in the Indian context. Since our main agenda is to present the validation account of a culturally appropriate intervention, we refrain from discussing the intricacies and complexities of Internet usage behaviour of people in the Indian subcontinent. However, we do see a tremendous potential in this line of research and speculate that a social-psychological inquiry with special reference to relevant factors would certainly unearth many interesting findings in this domain. We are positive that this pioneering futuristic attempt would help popularize the domain of eHealth to many unexplored territories, especially in rapidly growing economies such as India and China.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

We conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) utilizing a 3 (groups) × 2 (time) parallel group design for studying the impact of chosen variables on the student participants. The incoming participants were randomly allocated to any of the three groups, namely; experimental, placebo, and control, automatically through the SWBEP program.

3.2. Participants

A total of 220 student participants visited the SWBEP website and registered for the program after receiving the news widely circulated through word of mouth, advertisement and social networking sites. We used various dissemination strategies in a bid to popularize the program to a wider audience and to create awareness amongst the on-campus students. Out of the effective total, the majority (almost 92%) constituted on-campus students who were verbally motivated to spread the word about the program during their classroom interactions. On the contrary, only 8% of the student participants were from other universities who eventually dropped out from various stages of the program. Of all the participants who visited and signed up for the self-directed program and completed baseline assessment, one hundred seventy-seven (n = 177) is the combined effective total for our limited RCT. Although all these participants belonged to the pool of on-campus students, they were not coerced to register and complete the program at any time during the functionality of SWBEP. Seventy-five (n = 75), fifty-six (n = 56) and forty-six (n = 46) was the final number of participants in experimental, placebo and control group respectively. The web programming ensured that each of the four sessions (for experimental and placebo groups) are available to the participants in a time bound fashion following pre-assessment. The mean age of the participants in the experimental group was 23.62 (σ = 1.89) years. For the placebo and the control group, the mean age of participants was 22.36 (σ = 1.36) and 24.26 (σ = 1.98) years respectively. The male to female ratio in the case of the experimental group was 32.2% and 10.2% (57:18). The male and female ratio in the case of the placebo group was 24.3% and 7.3% (43:13) respectively, while it was 19.8% and 6.2% (35:11) in case of the control group. Though we captured demographic details such as educational qualification and geographical access points for each of the three groups, we checked significant differences between male and female participants [χ2 (2, n = 177) = .012, p = .994] with respect to gender differences. This non-significance in chi-square values suggests that the program was not differentiating between the two genders. Other chi-square values were not reported because the final sample was a homogenous sample consisting of on-campus undergraduate students who accessed intervention website from campus intranet. This homogeneity in the final sample is helpful in a way that it minimized the selection bias for our impact assessment; however, it also restricted us in calculating other demographic differences. We also obtained informed consent from all the self-directed participants and those who did not complete the full program were eventually excluded from the final data analysis.

3.3. Measures

We selected following standardized tools to measure the constructs at pre- and post-assessment. These tests were transcribed into an online version and then used for the SWBEP which, along with the intervention sessions were accessible only to the registered participants. The Cronbach alpha values of the web-transformed version of the scale at both times (pre-test values reported) were within acceptable range and reliable for this impact assessment.

3.3.1. Time management sub scale (skillset of ESAP)

The Emotional Skills and Assessment Process inventory (ESAP; Nelson et al., Citation2003) is a lengthy self-assessment instrument with an independent response format. It measures a variety of competencies and skill sets. Time management is the sub-dimension of intrapersonal competency set of the ESAP model and consists of about 12 items. The response to each item is independent of all others; the responses being more descriptive, sometimes descriptive, and not descriptive was scored 2, 1 or 0 respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha of the customized time management dimension was 0.81 (Time-1) for our sample.

3.3.2. Stress management sub-scale (skillset of ESAP)

Stress management consisted of 25 items and is also a part of the self-management competency set of the ESAP model. The ESAP inventory (ESAP; Nelson et al., Citation2003) was again used in part to serve this purpose. The items in the stress management skill set were chosen and they independently acted as a separate scale. The Cronbach’s alpha of the web adapted stress management dimension was 0.91 (Time-1) for our sample.

3.3.3. Wong and Law emotional intelligence scale (WLEIS; Wong & Law, Citation2002)

Wong and Law (Citation2002) developed the measure based on Davies, Stankov, and Roberts (Citation1998) summary of EI in the literature. It contains four domains that form the four subscales of the measure. The four constituent dimensions include self-emotions appraisal; use of emotion to facilitate performance; regulation of emotion and others’ emotion appraisal. There are 16 items in total for all the four dimensions. The Cronbach’s alpha for the whole inventory was 0.84 (Time-1) for our sample.

3.3.4. Brief self-report scale of self-management practices (BSRS)

The brief self-management scale (Williams, Moore, Pettibone, & Thomas, Citation1992) when originally developed and validated was entitled Lifestyle approach (LSA). It contains 22-items reflecting effective self-management strategies (e.g. I have written down my life goals, I make a list of things I want to do each day) where participants are instructed to indicate how similar each item was in their personal lifestyle by using the following Likert format: (a) very different from me, (b) somewhat different from me, (c) uncertain, (d) somewhat similar to me and (e) very similar to me. The constituent factors of LSA, namely; performance focus, goal-directedness, timeliness of task, organization of physical space, written plans and verbal report obtained upon factor analytic procedures from the original 48 item inventory was having acceptable psychometric properties (α = 0.76 at Time-1).

3.4. Procedure

Our procedure of the randomized control trial can be understood through the flow chart depicted in figure (see Figure ) which is in accordance with the CONSORT e-health guidelines and Internet research documentation standards (Mohr et al., Citation2010; Proudfoot et al., Citation2011). All self-directed participants gave consent while creating their login credentials. Using the login information, the participants were then asked to enter into SWBEP wherein a sequence of pre-assessment, intervention (online and offline exercises), followed by post-assessments were required to complete the creatively designed program (see Desmet & Sääksjärvi, Citation2016). It should also be noted that only after completing the four standardized questionnaires at pre-assessment, the participants were randomly allocated to any of the three groups. Apart from the delivery technique, we gave due consideration to the phenomenon of attrition and adherence, which often impacts the number of participants in such online interventions.

3.5. RCT: the intervention groups

3.5.1. Experimental group

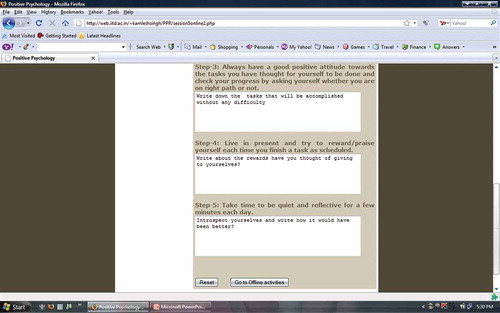

We constructed exercises for the time; stress; self-management and emotional intelligence in a theory inspired manner while adopting techniques from the reviewed literature (see Table ). The online and offline exercises drafted for SWBEP were creatively designed, operationalized and transformed for Internet delivery with a pre-post design methodology to assess the efficacy of even the intervention sub-components (e.g. Magyar-Moe, Citation2009). All the sessions were derived from theoretical constructs and were tailored into stepwise, text-based, psycho-educational tasks and exercises bearing a potential to enhance the well-being of student participants. The steps of the sessions were of simple instructional nature having a textbox option to write in the responses (e.g. Exhibit ). All the sessions were Internet delivered over a period of a month with a gap of one week in between every consecutive session. Each session started with a specially designed pre-session questionnaire that consisted of some session-specific items to be responded before and after an exercise was attempted (cf. Appendix B). This strategy was helpful in having an idea about impact assessment of each component of the intervention module.

We constructed the items in a manner that two general questions asked participants superficially about their concurrence with the exercise tasks while three to five specific items were of deep probing nature having suitable response anchors (see DeCoster, Citation2005). The general questions because of their simple nature were constructed with a 7-point rating scale (ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 7) to tap the threshold to a finer level of abstraction. The specific questions constructed were rated on a 5-point Likert scale with different, yet suitable response anchors (ranging from very much unlike me = 1 to very much like me = 5 etc.). These questions were constructed using the standardized methodology and we even assessed their psychometric properties before finally integrating them into SWBEP.

Both these types of pre-session items were meant to be responded at a single web page whereby our database was caching all these responses. After responding to these specific items, participants completed online exercise tasks consisting of sequential steps (see Choubisa, Citation2011; Magyar-Moe, Citation2009) weaved from the underlying constructs wherein participants provided subjective responses in the textboxes on appropriate web pages accessible exclusively to them. For instance, the first session of the experimental group was composed of five steps of engaging online exercise and tasks (see Exhibit for a snapshot). The offline tasks were rather general instructions related to the online tasks whereby the participant was required to practice the tasks during the waiting periods (see Figure ).

We requested participants through email reminders to log back again at the end of each wait-period to complete the subsequent sessions. It is at this stage that the session specific items of the previous exercise were repeated (review of sessions, general and specific items together) to move ahead in the SWBEP. E-mail reminders were a regular feature of the program that instructed and guided the participants to complete the remaining sessions as and when they were ready. This whole process was repeated throughout the length of the entire program for each of the four sessions (except the incurring gap of seven days) where the participants were required to practice the exercise tasks in an offline mode.

3.5.2. Placebo group

A major difference between the online tasks of the placebo and experimental group was that placebo tasks had one-point agenda and were devoid of any sequential steps. The waiting period of seven days was the only similar feature between the experimental and placebo sessions. The placebo sessions were exclusively based on positive psychological principles of savouring (see Bryant & Veroff, Citation2007) having the potential to evoke positive emotions and influence well-being. The online tasks were simple questions related to participants’ likes, dislikes, memory, positive emotions etc. The four sessions of the placebo group were as follows.

3.5.2.1. Placebo session one

Session one consisted of a simple question wherein the user allocated to this group was asked to write about the past memories and about something interesting happened in his/her life. The response was to be given in a textbox that was embedded within the question. Our website programming restricted the user so as not to use more than 250 characters in the text box. After making the response, the user could log out and was recalled back via email reminders for the second session. There were no offline instructional tasks for the placebo sessions.

3.5.2.2. Placebo session two

In the second session of the placebo online exercise, the participants were asked to write the names of five old friends from the eighth standard of their school. The response was to be given in the textbox that was accessible only to the participant.

3.5.2.3. Placebo session three

Participants who completed the previous two sessions were able to reach the third session after 21 days of beginning the program. In this session, the respondents were asked to write the names of five popular faces of their choice in the textbox irrespective of their likes and dislikes.

3.5.2.4. Final placebo session

Fourth and the final session were supposed to be concluded in conjunction with the post-testing questionnaires. In this session, the respondents were supposed to write the names of any five places which they have visited (and liked the most) in the textbox space. These tasks were included as placebo exercises because of their savouring effect on the participants although they did not belong to any category of empirically formulated and documented positive psychological interventions.

3.5.3. Control group

On the other hand, upon random allocation to the control group, the user must wait for 28 days, which was made equivalent to the number of days required to complete the remaining two sessions. For example, if two participants have logged on to the website on the same date and each one of them have been allocated to a separate group (one to experimental and another one to control) then the programming algorithm ensured that the time of completion of all the four sessions, which amounts to be 28 days (7 × 4) was kept as the waiting period to reach the post-test assessment stage in the control phase. This duration was accepted as the standard time gap between pre and post testing of the complete intervention module. Therefore, the participants allocated to this group completed only the standardized questionnaires twice with a gap of 28 days and were not given any online or offline tasks and exercises. The participants were also sent e-mail reminders (like other groups) at appropriate time intervals so that they can complete the post-assessment questionnaires and eventually the program. More important, no fee for participation was charged from any of the participants during the deployment of SWBEP.

4. Attrition and adherence

Attrition herein and in general has been defined as non-completion of the intervention module and dropping out from the study prematurely whereas adherence is the exact opposite and refers to sticking on to a program till the very end. In the present study, all participants completed baseline (pre-testing) questionnaires in full and then moved towards the subsequent stages of the intervention module. We evaluated data of only those participants who completed all the pre- and post-test measures. In our RCT, of all the registered participants, a total of 104 participants got allocated to the experimental group as per the allocation algorithm, a total of fifty (n = 50) participants got allocated to the control group and sixty-six (n = 66) participants got allocated to the placebo group (see Figure ). In terms of allocated participants, the rate of adherence in the experimental group was 93.26% (from pre-testing to the first session), 82.69% (from first to the second session), 75.96% (from second to the third session) and 72.11% (from third to final session). The rate of adherence in the experimental group in terms of the total number of participants was 47.27% (pre-test to first), 44.89% (first to second), 39.09% (second to third) and 35.90% (from third to fourth) of the total participants. The average rate of attrition in terms of participants allocated to the experimental group and the total number of participants was calculated to be 21.48% and 58.42% respectively. The rate of attrition from pre-test to post-test in the case of experimental group was calculated to be of the order of 27.89%.

The rate of adherence in case of the placebo group was of the order of 96.96% (pre-test to first), 89.39% (first to second), 86.36% (second to third) and 84.84% (from third to final session) respectively. The average rate of adherence in the placebo group from pre-test to post-test was about 84%. The rate of attrition in the placebo group was around 16%. Moreover, the rate of adherence in case of the control group was calculated to be of the order of 92%, whereas the rate of attrition for the group during a pre-post interval was around 8%.

These differential effects as seen in the adherence and attrition rates showed a general degenerative pattern which was consistent with other studies (for, e.g. Abbott, Klein, Hamilton, & Rosenthal, Citation2009; Parks, Citation2009). To draw a comparative picture, the rate of attrition was about 29% at six months for Seligman et al.’s (Citation2005) study and it was around 69.8% at post-testing and 83% at three months follow up in case of Mitchell et al.’s (Citation2009) study. Since our study was a preliminary study, SWBEP did not have any follow-ups. Therefore, calculation of significant differences from a longitudinal perspective was not possible for this limited RCT.

5. Results and analysis

Participants were self-directed youth registered for the program. Only the ones (n = 177), who have completed all the sessions of their respective groups were finally included in the analyses. To check the random allotment of participants in the three groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on overall scale scores of all the four pre-treatment measures. No significant differences between any of the four parameters namely stress management [F (2,174) = 2.02, p = .139], emotional intelligence [F (2,174) = 1.74, p = .179], time management [F (2,174) = 1.21, p = .301] and self-management [F (2,174) = 1.83, p = .164] confirmed the random allotment of participants in the program. These non-significant f-ratios constituted our baseline and eventually suggested that participants were at same levels, irrespective of their allocation to the experimental groups. As far as micro-level descriptors for demographic information are concerned, information related to gender, age, education and the geographical location was also captured, but, as explained earlier, we report only gender differences [χ2 (2, n = 177) = .012, p = . 994] for our final homogenous dataset.

We calculated paired sample t-tests between the matched scale scores obtained at Time-1 and Time-2 for each of the three groups separately to check the inferential statistics that reflect the efficacy of the intervention procedure. We deliberately restricted our analysis to within-group comparisons (vis-a-vis simultaneously reporting between-group differences) because we were more interested predominantly in knowing the effectiveness (impact assessment) of individual intervention components of the creatively conceived experimental group. The t-values for the experimental group (see Table ) were significant for the overall program indicating a positive impact and success of the program.

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, Cronbach Alpha’s and t-values of the measures used in pre- (Time-1) and post- (Time-2) intervention module for experimental group (n = 75)

We found significant differences in the t-value for overall self-management, which simply suggests that the participants became better at managing themselves after doing the experimental exercises. This overall significance of the first session of the experimental group [t (74) = 3.43, p < .001; d = 0.26] was supplemented by a significant increase in the values of some of the encompassing sub-components. For instance, apart from the cumulative scale scores of overall self-management, the sub-componential scores were also subjected to paired sample t-tests. The sub-components of overall self-management, especially timeliness of task accomplishment [t (74) = 2.69, p < .005], organization of physical space [t (74) = 3.12, p < .001], written plans for change [t (74) = 2.24, p < .01] and verbal support [t (74) = 1.86, p < .05] were significant and showed that there was a marked improvement in these skills or competencies when participants completed the exercises and tasks (see Table ).

Table 3. Paired sample t-test between pairs of pre- and post-standardized measures and the general and specific item measure before and after the intervention in the experimental group: (n = 75)

The t-values for emotional intelligence and its sub-components revealed marked improvement from the baseline assessment. The overall t-value for emotional intelligence was significant [t (74) = 5.51, p < .001, d = 0.50] suggesting its positive impact on the participants. Even the constituent dimensions of emotional intelligence, namely self-emotions appraisal [t (74) = 3.68, p < .001], use of emotion [t (74) = 3.74, p < .001], regulation of emotion [t (74) = 3.94, p < .001] and other’s emotions appraisal [t (74) = 3.26, p < .001] were significant. These positive results indicate that participants became more emotionally intelligent after doing the SWBEP exercises crafted for enhancing emotional intelligence. Our third component of the SWBEP program viz. time management was also significant [t (74) = 5.39, p < .001 (one-tailed), d = 0.65] in its impact and had the highest effect size with reference to the remaining three components. The significance and success of time management dimension might be attributed to the fact that participants were better able to manage their time following the step-wise diary maintaining intervention. Though the final session on stress management was also significant [t (74) = 6.61, p < .001 (one-tailed), d = 0.64], the effect size was medium for this component as per standards (Cohen, Citation1988). Overall, the significant effect in all the four components of the experimental group suggests that participants got apparent benefits after going through the online and offline intervention exercises and tasks. However, the nature of the benefits is a separate line of inquiry and further qualitative investigations would help uncover them.

As far as placebo and control group are concerned, there were no significant differences in score values before and after the participants completed the program in either of the cases. Even, the effect sizes were negligibly small in comparison to the experimental intervention group. For instance, some of the standardized sub-componential scores like written plans for change and verbal support of the self-management dimension have shown negligible improvement in terms of mean scores following the placebo exercises, but the overall effect was non-significant (see Table ). This negligible and non-significant difference prompts one to conclude that the content of the intervention design seems to vary in experimental and placebo groups which can be further validated through multiple between-group comparisons.

Table 4. Means, standard deviations, t-values and effect sizes of the measures used at Time-1 and Time-2 of intervention module for placebo group (n = 56)

The pre-post differences in the means as calculated by the paired t-tests in the case of the control group were all non-significant for the given standardized measures. The values for all the measures at both the times were not deviating much from the mean and this signified no improvement from the baseline level. This further corroborated the fact that the group was acting like a true control group because of its potentially non-significant impact on the enrolled participants (see Table ).

Table 5. Means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha, t-values and effect sizes of the measures used at Time-1 and Time-2 of intervention module for control group (n = 46)

Overall, to provide a comparative picture of the impact assessment the mean difference after the intervention in the scale values have been plotted as stacked line graphs for each component across the three groups (see Figure ).

Figure 2. Stacked line graphs showing intervention effect of components across groups.

Notes: Top left: Intervention effect of self-management skill across groups; top right—intervention effect of emotional intelligence skills across the groups; bottom left—intervention effect of time-management skills across groups; bottom right—intervention effect of Stress management skills across groups before and after the intervention.

6. Discussion

The results of the limited trial lend support to the fact that well-being enhancing competencies can be schematically manipulated through intentional activities and exercises (see Fordyce, Citation1977, Citation1983; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, Citation2005). The skills and competencies such as self-management, stress management, time management and emotional intelligence have been validated and found to be highly relevant to the lives of Indian college students. The encouraging results obtained in the current research points to the overall conclusory evidence that well-being can potentially be enhanced by practicing such positive psychological exercises and tasks. However, the best part is the fact that these were delivered using modern web-based technology (ICTs) in a developing world scenario (García, Ahumada, Hinkelman, Muñoz, & Quezada, Citation2004). As far as the methodology and implications of this research are concerned, this would most likely be a pioneering study in the area of online wellness promotion in a developing milieu, especially India (see Mehrotra, Citation2011 for a review).

This research highlights a shift from the conventional wellness promotion paradigm, which has not moved beyond validating certain positive psychological exercises (see Mitchell et al., Citation2009; Seligman et al., Citation2005). For instance, the most commonly found positive exercises, which are tested through RCTs have been restricted to writing letters of gratitude (Boehm, Lyubomirsky, & Sheldon, Citation2011; Lyubomirsky, Dickerhoof, Boehm, & Sheldon, Citation2011; Seligman et al., Citation2005), counting one’s blessings (Emmons & McCullough, Citation2003; Froh, Sefick, & Emmons, Citation2008), practicing optimism (King, Citation2001; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, Citation2006), performing acts of kindness (Dunn, Aknin, & Norton, Citation2008; Sheldon, Boehm, & Lyubomirsky, Citation2012), meditating on positive feeling towards others (Fredrickson, Cohn, Coffey, Pek, & Finkel, Citation2008) and using one’s signature strengths (Seligman et al., Citation2005). It seems that there have been only a handful of such positive psychological interventions that constitute the repository of these scientifically documented strategies. The implication of this review gives us a lesson that it would be legitimate to call our program “SWPP” (Students Wellness Promotion Program) considering our arguments with respect to ‘well-being’ and ‘wellness’.

Although the main aim of this research is not to replicate the existing positive psychological interventions, it is an ambitious attempt to use the methodology adopted by the existing studies to come up with a context relevant wellness promotion intervention having comparable capabilities and powers (see Dalal & Mishra, Citation2006). Even, the pioneering well-being enhancement intervention viz. ‘the fundamental happiness program’ consisted of nine specific lifestyle activities and competencies which acted as predictors of well-being of the community college students (Fordyce, Citation1977, Citation1983). In effect, we chose the context of the current study while drawing empirical support from both these pioneering programs.

The results obtained for the experimental groups robustly support the fact that participants who are actively involved in online and offline exercises have improved cognitions of their own skills and competencies. The small to moderate effect size for all the four competencies as compared to the moderate effect size of Seligman et al.’s (Citation2005) study further suggests the plausibility of the exercises included in the current intervention. Since well-being is assumed to be a derived construct resulting from enhanced skill-set and competencies, we did not utilize explicit measures of well-being and employ construct specific standardized measures. The non-significant statistical values and very low effect sizes in case of control group indicates that practicing cognito-behavioural exercises ‘in-principle’ seems more beneficial. Overall, leaving some caveats, we conclude that a text-based, self-directed and competencies enhancing wellness promotion program can be potentially advantageous and feasible.

7. Limitations and implications

As outlined before, the current research is an overly ambitious and meticulous exploration of developing a contextual and culturally relevant wellness promotion intervention program. Yet, there were certain limitations to the current research and we present our experiential learning along with other relevant issues. First, the exploration of the incorporated competencies or constructs from a standpoint of the well-being or wellness enhancing models seems to be limited from a research perspective. So, it is highly recommended that the identification and selection of constructs (be it skills or competencies) should be done very carefully. It is due to this reason the research on these issues demands an in-depth exploration and elaboration of the positive activities (cognito-behavioural intentional activities) viewpoint. Hence, it is also limited from a data-analytical perspective. Second, to enrich this domain of wellness promotion, there is a contextual need to incorporate a variety of other factors or alternatively the skills that supposedly possess a direct or indirect connection with well-being. This process will eventually help in articulating a theoretically sound intervention module that would be even more empowering to the participants. However, the biggest threat at this point is that the practice of psychology using modern Internet technology has been limited to superficial levels in most of the developing nations where only some scholars have written about the mere speculative state of this relationship and its probable consequences (e.g. Singh, Citation2003). Third, owing to deficiency of scientific studies (Online PPIs), the relative impact assessment of the current program became very difficult. This resultant paucity threatens the idea of generalizability of the enthusiastically positive results obtained in the current study. Fourth, many factors such as personality, anxiety, depression, interest, etc. were not taken into consideration for our proposed intervention module, which might have acted as intervening or confounding variables in our case. We strongly believe that individual difference factors must be considered in positive psychology interventions (see Antoine, Dauvier, Andreotti, & Congard, Citation2018). Fifth, since, follow up(s) after the post-assessment was not incorporated in the research design, its absence has again limited the scope and generalizability of the current research in terms of longitudinally predicting the magnitude of the obtained indices. In addition, between-group differences that control the family wise and group-wise error rates (cf. Benjamin & Hochberg, Citation1995) were not calculated for our experimental groups. Although in ideal situations, ANCOVA (including a MANCOVA based full factorial model) for each outcome variable and controlling for Time-1 scores in our case with a priori or post hoc contrasts and interactions (Bonferroni, Tukey’s HSD etc.) would have addressed this issue. Nonetheless, it should also be noted that addressing all the issues (such as Type-1 error generated through multiple comparisons) does not guarantee satisfactory resolution, including the way the results in trials are reported and interpreted (cf. Bland & Altman, Citation2011; Boutron, Dutton, Ravaud, & Altman, Citation2010; Gelman, Hill, & Yajima, Citation2012). And, lastly, a major threat to the accuracy of such design is the problem of attrition and the resultant biases that can potentially disrupt the randomization process (cf. de Bruin, Citation2015). Although this can seriously compromise the accuracy of the outcome results, intent to treat (Gross & Fogg, Citation2004) statistics or a suitable higher order statistic should be calculated in ideal situations. Therefore, howsoever promising it seems, the findings from this study cannot be universally generalized. This may be because the results of the impact assessment are deduced on the basis of only seventy-five (n = 75) self-directed students, a majority of whom were on-campus students. The aforementioned figure is a negligible proportion of the total number of 29.42 million college students enrolled in India (UGC Annual Report, Citation2016). Overall, irrespective of its limited generalizability, the study does not have broad implications whereby it can be said with utmost confidence that such programs (SWBEP) will work for all categories and all types of college students.

8. Conclusion and suggestions

Although we report some interesting positive findings in the current study, the reasons for this should also be explored and further explorations, extensions, and replications of this study or new variants of such attempts should be carried out with an even bigger sample (see Oliver & MacLeod, Citation2018 for an intervention in work settings). We believe that the scope and credibility of the hypothesized rationale would be further justified if a heterogeneous sample is taken into consideration for future attempts and then full factorial models are developed. Thus, we suggest that more such efforts, including replications and extensions, is the need of the hour in order to introduce the idea of ubiquity and make positive psychology based interventions a universally accepted phenomenon across developing nations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank, first and foremost, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for financially supporting the first author for his doctoral research that eventually culminated in this study. The authors would also like to thank the staff at IIT Delhi, especially at the computer services centre for helping them in safekeeping, proper functioning, maintaining and broadcasting the website of our interventional program. Also, the authors would like to thank two brilliant students (Mr Anupam Amar and Mr Amritanshu Nanda) for helping meticulously in coding and designing the website of the program. The authors strongly believe that without the technical help of these wonderful technology students and staff, they would not have accomplished this mission. Furthermore, an earlier version of the article was presented as a poster by the authors in the Second World Congress on Positive Psychology.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rajneesh Choubisa

The authors have been actively involved in promoting positive psychology research in India. As a matter of fact, the authors are founding members of the National Positive Psychology Association (NPPA) which is a registered body based at New Delhi. Second Author is also the board member of International Positive Psychology Association (IPPA) and has published extensively on positive psychology constructs. The detailed credentials of the authors are available on the website of NPPA. Its URL is http://nppassociation.org/.

Notes

1. The website program code and page wise detailed content are available with authors. See Appendices A and B for assessment insights.

References

- Abbott, J., Klein, B., Hamilton, C., & Rosenthal, A. (2009). The impact of online resilience training for sales managers on wellbeing and performance. e-Journal of Applied Psychology, 5(1), 89–95. doi:10.7790/ejap.v5i1.145

- Ajzen, I. (2006). Retrieved from http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.intervention.pdf

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (Ed.). (2008). Technology and well-being. UK: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (UK).

- Anstead, S. J. (2009). College students and stress management: Utilizing biofeedback & relaxation skills training ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Brigham Young University. Retrieved from: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/.

- Antoine, P., Dauvier, B., Andreotti, E., & Congard, A. (2018). Individual differences in the effects of a positive psychology intervention: Applied psychology. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 140–147. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.024

- Arensman, E., Koburger, N., Larkin, C., Karwig, G., Coffey, C., Maxwell, M., … Alexandrova-Karamanova, A. (2015). Depression awareness and self-management through the internet: Protocol for an internationally standardized approach. JMIR Research Protocols, 4(3), e99. doi:10.2196/resprot.4358

- Barak, A., Klein, B., & Proudfoot, J. G. (2009). Defining internet supported therapeutic interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38, 4–17. doi:10.1007/s12160-009-9130-7

- Benjamin, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300.

- Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (2011). Comparisons against baseline within randomized groups are often used and can be highly misleading. Trials, 12, 264. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-264

- Boehm, J. K., Lyubomirsky, S., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). A longitudinal experimental study comparing the effectiveness of happiness-enhancing strategies in Anglo Americans and Asian Americans. Cognition & Emotion, 25, 1263–1272. doi:10.1080/02699931.2010.541227

- Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 119–139. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

- Boutron, I., Dutton, S., Ravaud, P., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically non-significant results for primary outcomes. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(20), 2058–2064. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.651

- Bryant, F., & Veroff, J. (2007). Savoring: A new model of positive experience. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bughi, S. A., Sumcad, J., & Bughi, S. (2006). Effect of brief behavioral intervention program in managing stress in medical education from two southern California universities. Medical Education Online, 11–17. Retrieved from www.med-ed-online.net/index.php/meo/article/download/4593/4772

- Burt, C. D. B., & Kemp, S. (1994). Construction of activity duration and time management potential. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 8, 155–168. doi:10.1002/acp.2350080206

- Calvo, R. A., Vella-Brodrick, D., Desmet, P., & Ryan, R. (2016). Editorial for “Positive computing: A new partnership between psychology, social sciences and technologists”. Psychology of Well-Being, 6, 10. doi:10.1186/s13612-016-0047-1

- Chiauzzi, E., Brevard, J., Thurn, C., Decembrele, S., & Lord, S. (2008). MyStudentBody-stress: An online stress management intervention for college students. Journal of Communication: International Perspectives, 13(6), 555–572. doi:10.1080/10810730802281668

- Choubisa, R. (2011). Enhancing college students’ well-being through a web-based intervention module: An empirical investigation ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi.

- Choubisa, R., & Singh, K. (2011). A confirmatory randomized control trial of well-being related skills enhancing internet intervention module for college students. In Second world congress on positive psychology, poster abstracts (P-148). doi:10.1037/e537902012-148

- Christensen, H., & Griffiths, K. M. (2002). The prevention of depression using the internet. Medical Journal of Australia, 177, S122–S125. Retrieved from https://researchers.anu.edu.au/publications/32047

- Claessens, B. J. C., Eerde, W. V., & Rutte, C. G. (2007). A review of the time management literature. Personnel Review, 36(2), 255–276. doi:10.1108/00483480710726136

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cohn, M. A., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). In search of durable positive psychology interventions: Predictors and consequences of long-term positive behavior change. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(5), 355–366. doi:10.1080/17439760.2010.508883

- Dalal, A., & Mishra, G. (2006). Psychology of health & well-being: Some emerging perspectives. Psychological Studies, 51(2–3), 91–104.

- Davies, E. B., Morriss, R., & Glazebrook, C. (2014). Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(5), e130. doi:10.2196/jmir.3142

- Davies, M., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. D. (1998). Emotional intelligence: In search of an elusive construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(4), 989–1015. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.989

- de Bruin, M. (2015). Risk of bias in randomized controlled trials of health behaviour change interventions: Evidence, practices and challenges. Psychology & Health, 30(1), 1–7. doi:10.1080/08870446.2014.960653

- DeCoster, J. (2005). Scale construction notes. Retrieved from http://www.stat-help.com/notes.html

- Desmet, P. M. A., & Sääksjärvi, M. C. (2016). Form matters: Design creativity in positive psychological interventions. Psychology of Well-Being, 6, 7. doi:10.1186/s13612-016-0043-5

- Drigas, A., Koukianakis, L., & Papagerasimou, Y. (2011). Towards an ICT-based psychology: E-psychology. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 1416–1423. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.045

- Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687–1688. doi:10.1126/science.1150952

- Ebert, D. D., Cuijpers, P., Muñoz, R. F., & Baumeister, H. (2017). Prevention of mental health disorders using internet- and mobile-based interventions: A narrative review and recommendations for future research. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 116. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00116

- Eisen, K. P., Allen, G. J., Bollash, M., & Pescatello, L. S. (2008). Stress management in the workplace: A comparison of a computer-based and an in-person stress-management intervention. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 486–496. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2007.02.003

- Eldeleklioglu, J., Yilmaz, A., & Guletkin, F. (2010). Investigation of teacher trainees’ psychological well-being in terms of time management. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 342–348. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.022

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 84, 377–389. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

- Eysenbach, G., Vella-Brodrick, D., Grohol, J., & Manicavasagar, V. (2014). Feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based positive psychology program for youth mental health: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(6), e140. doi:10.2196/jmir.3176

- Fordyce, M. W. (1977). Development of a program to increase personal happiness. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 24(6), 511–521. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.24.6.511

- Fordyce, M. W. (1983). A program to increase happiness: Further studies. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(4), 483–498. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.30.4.483

- Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062. doi:10.1037/a0013262

- Froh, J. J., Sefick, W. J., & Emmons, R. A. (2008). Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 213–233. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005

- Fusilier, M., & Durlabhji, S. (2005). An exploration of student internet use in India: The technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Campus Wide Information Systems, 22(4), 233–246. doi:10.1108/10650740510617539

- Fusilier, M., Durlabhji, S., Cucchi, A., & Collins, M. (2005). A four country investigation of factors facilitating student internet use. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 8(5), 454–464. doi:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.454

- García, V., Ahumada, L., Hinkelman, J., Muñoz, R. F., & Quezada, J. (2004). Psychology over the internet: Online experiences. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 7(1), 29–33. doi:10.1089/109493104322820084

- Gelman, A., Hill, J., & Yajima, M. (2012). Why we (usually) don’t have to worry about multiple comparisons. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 5, 189–211. doi:10.1080/19345747.2011.618213

- Gosling, S. D., & Johnson, J. A. (2010). Advanced methods for conducting online behavioral research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Gross, D., & Fogg, L. (2004). A critical analysis of the intent-to-treat principle in prevention research. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 25, 475–489. doi:10.1023/B:JOPP.0000048113.77939.44

- Hoff Macan, T. (1994). Time management: Test of a process model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(3), 381–391. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.381

- Howard, F. (2008). Managing stress or enhancing wellbeing? Positive psychology’s contributions to clinical supervision. Australian Psychologist, 43(2), 105–113. doi:10.1080/00050060801978647

- King, L. A. (2001). The health benefits of writing about life goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 798–807. doi:10.1177/0146167201277003

- Kraut, R., Olson, J., Banaji, M., Bruckman, A., Cohen, J., & Couper, M. (2004). Psychological research online: Report of Board of Scientific Affairs’ advisory group on the conduct of research on the internet. The American Psychologist, 59(2), 105–117. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.105

- Kremers, I. P., Steverink, N., Albersnagel, F. A., & Slaets, J. P. J. (2006). Improved self-management ability and well-being in older women after a short group intervention. Aging & Mental Health, 10, 476–484. doi:10.1080/13607860600841206

- Kushlev, K., Heintzelman, S. J., Kanippayoor, J. M., Leitner, D., Lutes, L. D., Wirtz, W., & Diener, E. (2018, April). Delivering happiness online: A randomized controlled trial of a web platform for increasing subjective well-being. In Proceedings of technology, mind, and society (APAScience’18), Washington, DC, USA (2 p).

- Layous, K. (2018). Malleability and intentional activities. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay. (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers. Retrieved from nobascholar.com

- Layous, K., Lee, H., Choi, I., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). Culture matters when designing a successful happiness-increasing activity: A comparison of the United States and South Korea. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 44, 1294–1303. doi:10.1177/0022022113487591

- Lippke, S., & Ziegelmann, J. P. (2008). Theory-based health behavior change: Developing, testing, and applying theories for evidence-based interventions. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57(4), 698–716. doi:10.1111/apps.2008.57.issue-4

- Lorig, K. R., & Holman, H. R. (2003). Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes & mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26(1), 1–7. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01

- Lyubomirsky, S., Dickerhoof, R., Boehm, J. K., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: An experimental longitudinal intervention to boost wellbeing. Emotion, 11, 391–402. doi:10.1037/a0022575

- Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111–131. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111

- Macan, T. H., Shahani, C., Dipboye, R., & Phillips, A. P. (1990). College students’ time management: Correlations with academic performance and stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 760–768. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.760

- MacLeod, A. K., Coates, E., & Hetherton, J. (2008). Increasing well-being through teaching goal-setting and planning skills: Results of a brief intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 185–196. doi:10.1007/s10902-007-9057-2

- Maddux, J. (2008). Positive psychology and the illness ideology: Toward a positive clinical psychology. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 54–70. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00354.x

- Magyar-Moe, J. L. (2009). Positive psychological interventions. In J. L. Magyar-Moe (Ed.), Therapist’s guide to positive psychology interventions (pp. 73–176). USA: Academic Press, USA. ISBN: 9780123745170.

- Mancini, M. (2003). Time management. USA: The McGraw Hill Companies Inc. doi:10.1036/0071425578

- Mazzucchelli, T. G., Kane, R. T., & Rees, C. S. (2010). Behavioral activation interventions for well-being: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 105–121. doi:10.1080/17439760903569154

- Mehrotra, S. (2011). Positive psychology research in India: A review and critique. Journal of Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 37(1), 9–26.

- Miller, R. W., & Duncan, E. (2015). A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing two positive psychology interventions for their capacity to increase subjective wellbeing. Counseling Psychology Review, 30(3), 36–46.

- Misra, R., & McKean, M. (2000). College students’ academic stress and its relation to their anxiety, time management and leisure satisfaction. American Journal for Health Studies, 16(1), 41–51.

- Mitchell, J., Stanimirovic, R., Klein, B., & Vella-Brodrick, D. (2009). A randomized controlled trial of a self-guided internet intervention promoting well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 749–760. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.02.003

- Mitchell, J., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Klein, B. (2010). Positive psychology and the internet: A mental health opportunity. e-Journal of Applied Psychology, 6, 30–41. doi:10.7790/ejap.v6i2.230

- Mohr, D., Hopewell, S., Schultz, K. F., Montori, V., Gotzche, P. C., Devereaux, P. J., … Altman, D. G. (2010). CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63, 1–37. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004

- Mongrain, M., & Anselmo-Matthews, T. (2012). Do positive psychology exercises work? A replication of Seligman et al. (2005). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 382–389. doi:10.1002/jclp.21839

- Myers, N. D., Prilleltensky, I., Prilleltensky, O., McMahon, A., Dietz, S., & Rubenstein, C. L. (2017). Efficacy of the fun for wellness online intervention to promote multidimensional well-being: A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science, 18, 984–994. doi:10.1007/s11121-017-0779-z

- Nelson, D., Low, G., & Vela, R. (2003). ESAP: Emotional skills assessment process. Interpretation and intervention guide. Kingsville, TX: Texas A&M University Kingsville.

- Nonis, S. A., Hudson, G. I., Logan, L. B., & Ford, C. W. (1998). Influence of perceived control over time on college student’s stress and stress-related outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 39(5), 587–605. doi:10.1023/A:1018753706925

- O’Connell, B. H., O’Shea, D., & Gallagher, S. (2015). Enhancing social relationships through positive psychology activities: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(2), 149–162. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1037860

- Oliver, J. J., & MacLeod, A. K. (2018). Working adult’s well-being: An online self-help goal-based intervention. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(1), 1–16. doi:10.1111/joop.12212

- Papadatou-Pastou, M., Goozee, R., Payne, E., Barrable, A., & Tzotzoli, P. (2017). A review of web-based support systems for students in higher education. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11, 59. doi:10.1186/s13033-017-0165-z

- Parks, A. C. (2009). Positive Psychotherapy: Building a model of empirically supported self-help ( Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Pennsylvania, PA, Dissertations available from ProQuest. AAI3363580. https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3363580.

- Portnoy, D. B., Scott-Sheldon, L. A. J., Johnson, B. T., & Carey, M. P. (2008). Computer delivered interventions for health promotion and behavioral-risk reduction: A meta-analysis of 75 randomized controlled trials, 1988-2007. Preventive Medicine, 47, 3–16. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.014

- Proudfoot, J., Klein, B., Barak, A., Carlbring, P., Cuijpers, P., Lange, A., … Andersson, G. (2011). Establishing guidelines for executing and reporting internet intervention research. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40(2), 82–97. doi:10.1080/16506073.2011.573807

- Proyer, R. T., Wellenzohn, S., Gander, F., & Ruch, W. (2015). Toward a better understanding of what makes positive psychology interventions work: Predicting happiness and depression from the person x intervention fit in a follow-up after 3.5 years. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 7(1), 108–128. doi:10.1111/aphw.12039

- Recabarren, M., Nussbaum, M., & Leiva, C. (2007). Cultural illiteracy and the internet. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10(6), 853–856. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.9940

- Regehr, C., Glancy, D., & Pitts, A. (2012). Interventions to reduce stress in university students: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148(1), 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.026

- Ritterband, L. M., Gonder-Frederick, L. A., Cox, D. J., Clifton, A. D., West, R. W., & Borowitz, S. M. (2003). Internet interventions: In review, in use, and into the future. Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 34(5), 527–534. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.34.5.527

- Ritterband, L. M., & Tate, D. F. (2009). The science of internet interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38, 1–3. doi:10.1007/s12160-009-9132-5

- Rout, U. R., & Rout, J. K. (2002). Stress management for primary health care professionals. USA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Schueller, S. M., & Parks, A. C. (2012). Disseminating self-help: Positive psychology exercises in an online trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(3), e63. doi:10.2196/jmir.1850

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. The American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

- Sheldon, K. M., Boehm, J. K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). Variety is the spice of happiness: The hedonic adaptation prevention (HAP) model. In I. Boniwell & S. David (Eds.), Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 901–914). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). Achieving sustainable gains in happiness: Change your actions, not your circumstances. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 55–86. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-0868-8

- Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 65(5), 467–487. doi:10.1002/jclp.20593

- Singh, K., & Choubisa, R. (2009). Effectiveness of self focused intervention for enhancing student’s well-being: An empirical investigation. Journal of Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 35, 23–32.

- Singh, P. (2003). Internet and mental health. In N. K. Chandel, R. Jit, S. Mal, & A. Sharma (Eds.), Psychological implications of information technology (pp. 141–148). New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications.

- Singhvi, M., & Puri, P. (2008). Effects of preksha dhyan meditation on emotional intelligence and mental stress. Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 82–89.

- UGC. (2016). University Grants Commission, annual report (2016-2017). Retrieved from https://www.ugc.ac.in/stats.aspx

- Williams, R. L., Moore, C. A., Pettibone, T. J., & Thomas, S. P. (1992). Construction and validation of a brief self-report scale of self-management practices. Journal of Research in Personality, 26, 216–234. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(92)90040-B

- Wong, C., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly, 13, 243–274. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00099-1

- Woolfolk, A. E., & Woolfolk, R. L. (1986). Time management: An experimental investigation. Journal of School Psychology, 24, 267–275. doi:10.1016/0022-4405(86)90059-2

- Yarosh, S., & Schueller, S. M. (2017). “Happiness inventors”: Informing positive computing technologies through participatory design with children. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(1), e14. doi:10.2196/jmir.6822

Appendix A

Informed Consent

I agree to take part in the student well-being enhancement program delivered online by the researchers at Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. I completely understand that agreeing to take part in the above program means that I hereby endorse and I am willing to:

Complete a pre-test ad post-test interview schedule at the starting and preceding the termination of the above program.

Complete an internet-based well-being program by logging in at the requisite time intervals.

Participation in this program is voluntary and I can choose not to participate in part or all of the program or else can withdraw at any stage of the program without being penalized or disadvantaged in any manner. If one has been randomly assigned to the control condition, he may not get the benefits of the intervention program as per the hypothesis.

The information provided on my behalf will remain confidential and no information in part or whole whatsoever be provided to any person/institution/organization without my permission.

I understand that data from the web pages will be kept in a secured storage and will be accessible only to the research team. Further if any publications are out from the data my identity will be made anonymous (if at all documented) and remains disclosed.

I understand that if I complete the information and click on the ‘continue’ button below that I give away my consent to participate in the above program without any objections.

I am above 18 years of age and I consent to participating in this research program.

I AGREE

Brief Self-Report Scale of Self-Management Practices (BSRS)

Response Scale

Very different from me

Somewhat different from me

Uncertain

Somewhat similar to me

Very similar to me

Items:

In most situations, I have a clear sense of what behaviours would be right or wrong for me.

When confronted with many different things to do, I have difficulty deciding what is most important to do. (R)

After making a decision about what is most important to do at any given time, I easily get side-tracked from that activity. (R)

Once I decide what is most important to do at any given time, I start on that task right away.

I write down the pros and cons of any behaviour change I am considering.

I have difficulty judging how long it will take me to complete a task. (R)

I seldom analyze what I am saying to myself regarding problem areas in my life. (R)

I have written down my life goals.

When I begin a personal change project, I generally keep my plans to myself.

I keep my work space well organized.

I have a clear sense of what I most want to experience in my life.

I seldom ask for feedback from others about behaviours I need to change and how best to change those behaviours. (R)

I complete tasks at the time I say I’m going to complete them.

I seldom write down my yearly goals. (R)

I’m confused as to the kind of personal qualities I want to develop in my life. (R)

I have difficulty matching various tasks with my energy level. (R)

I subdivide big tasks into a series of smaller tasks.

I have little idea as to what I most want to achieve in my life. (R)

I actively work to make the place where I spend a lot of time more attractive.

I complete major tasks well in advance of deadlines.

When I deviate from my selected goal, I have a hard time getting back on track. (R)

My living space is quite messy. (R)

Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Self Report Measure

Response Scale:

Strongly Disagree

Slightly Disagree

Neither Agree not Disagree

Slightly Agree

Strongly Agree

Items:

I have a good sense of why I have certain feelings most of the time.

I have good understanding of my own emotions.

I really understand what I feel.

I always know whether or not I am happy.

I always know my friends’ emotions from their behaviour.

I am a good observer of others’ emotions.

I am sensitive to the feelings and emotions of others.

I have good understanding of the emotions of people around me.

I always set goals for myself and then try my best to achieve them.

I always tell myself I am a competent person.

I am a self-motivating person.

I would always encourage myself to try my best.

I am able to control my temper so that I can handle difficulties rationally.

I am quite capable of controlling my own emotions.

I can always calm down quickly when I am very angry.

I have good control of my own emotions.

Time Management Measure (Sub-scale of ESAP)

Response Scale and Scoring Procedure:

(2) Most likely or descriptive of you

(1) Sometimes like or descriptive of you and sometimes not.

(0) Least like or descriptive of you)

Items:

I organize my responsibilities into an efficient personal time schedule.

I set objectives for myself and then successfully complete them within a specific time frame.

I plan and complete my work on schedule.

If I were being evaluated in terms of job effectiveness, I would receive high ratings in managing my work day.

I waste very little time.

I know exactly how much time I need to complete assignments and projects.

I am an efficient and well-organized person.

I am able to manage my time in the present so that I am not pressured by always trying to catch up with things that I have not done in the past.

I am among the first to arrive at meetings or events.

I am on time for my appointments.

I effectively work on several projects at the same time with good results.

I control my responsibilities rather than being controlled by them.

Stress Management Measure (Sub-scale of ESAP)

Response Scale and Scoring Procedure:

(2) Most likely or descriptive of you

(1) Sometimes like or descriptive of you and sometimes not.

(0) Least like or descriptive of you

Items:

Even though I have worked hard, I do not feel successful.

I cannot find the time to really enjoy life the way I would like.

I am bothered by physical symptoms, such as headaches, insomnia, ulcers or hypertension.

When I see someone attempting to do something that I know I can do much faster, I get very impatient.

I am a tense person.

I find it really difficult to let myself go and have fun.

I am not able to comfortably express strong emotions such as fear, anger and sadness.

If I really relaxed and enjoyed life the way I wanted to, I would find it hard to feel good about myself.

Even when I try to enjoy myself and relax, I feel a lot of pressure.

I often want people to speak faster and find myself wanting to hurry them up.

I am able to relax at the end of a hard day and go to sleep easily at night.

I often feel that I have little control over what I think, feel and do.

I am unable to relax naturally, and tend to rely on other things (drugs, alcohol, tobacco etc.) to calm me down.

I feel tense and pressured by the way I have to live.

My family and friends often encourage me to slow down and relax more.

I am impatient with myself and others, and I am usually pushing to hurry things up.

I am under so much stress that I can feel the tension in my body.

My friends often say that I look worried, tense or uptight.

I effectively deal with tension, and I have learned a variety of healthy ways to relax.

On the job, I work under a great deal of tension.

I have been unable to break negative habits that are a problem for me (drinking, smoking, overeating etc.).

When I really relax and do absolutely nothing, I feel guilty about wasting time.

I have become extremely nervous and tense at times, and doctors have advised me to slow down and relax.

I seem to continually struggle to achieve and do well and seldom take time to honestly ask myself what I really want out of life.

I have developed relaxation techniques and practice them daily.

Appendix B

Session-Specific Questionnaires

Session on Self-Management

Rate yourself on the following items in terms of your agreement or disagreement during past week:

General items: (Two items on a 7-point Likert scale)

A. I can manage myself without any problem.

Strongly Disagree

Disagree

3 Slightly Disagree

Neither Agree nor Disagree

Slightly Agree

Agree

Strongly Agree

B. I utilize resources that are needed for a committed and motivated life.

Strongly Disagree

Disagree

3 Slightly Disagree

Neither Agree nor Disagree

Slightly Agree

Agree

Strongly Agree

Specific items: (Three to five items on a 7-point Likert scale)