Abstract

Aim: To describe the systematic development of an evidence-based, tailored, interactive web application for self-management of work-related stress, and to test usability issues regarding how to proceed through the programme.

Methods: Evidence from the fields of stress management, behaviour change and web-based interventions was the foundation for the theoretical framework and content. The next step was the development process of the web application and validation among experts and one possible end user. Last, a usability test with 14 possible end users was conducted.

Results: The web-application, My Stress Control (MSC), was built on a solid theoretical framework. It consists of 12 modules including: introduction, psychoeducation, ambivalence, stress management strategies, lifestyle change, and maintenance. Self-monitoring, goal-setting, re-evaluating goals, feedback, and prompting formulation of intention to change are central techniques supporting behaviour change. The usability test revealed difficulties in understanding how to proceed through the programme.

Conclusion: The development contributes to filling a gap in the literature regarding development of complex web-based interventions. MSC is dissimilar to existing programs in the field, considering the tailoring and multi-tracked opportunities. Although developed from the evidence in multiple fields, the web application would benefit from further development to support users in reaching the end module.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Stress is a major cause of sick leave in many Western countries. Work with stress management for those at risk of stress-related ill health is often restricted, due to a lack of healthcare resources. Web applications make stress management available for unlimited numbers of users, but there is a gap in the literature regarding development of complex web-based self-management programmes. We suggest a development process for tailored web-based self-management. A web-based programme, including tools identified in previous research as effective, can contribute to individuals’ learning about stress and to supporting long-term behavioural change to prevent stress from being harmful and leading to decreased health. The development process ended in the web-based programme My Stress Control. Although it was developed from current evidence in multiple fields, users had trouble reaching the end module. Thus, further development is essential to enhance the usability of the programme.

1. Introduction

In recent years, stress as a work life health issue has been highlighted in the majority of industrialised countries. Studies show that every fourth worker in Europe is exposed to work-related stress, defined as involving work situations with either high demands and low control, high work load and low reward or organisational injustice (Siegrist, McDaid, Freire-Garabal, & Levi, Citation2013). Stress can be defined as involving internal or external demands that are appraised to exceed an individual’s real or perceived resources (Lazarus, Citation1993). Stress-evoking demands such as perceived dissatisfaction with work, as well as high psychological and physical strain, are both associated with sick-listing (Sandmark, Citation2007). Sleeping disorders, anxiety and depression are also frequently associated with work-related stress (OECD, Citation2013), and work-related stress increases the relative risk for cardiovascular disease (Nyberg et al., Citation2013).

Even though work-related stress in many cases is a result of organisational or structural problems, individual stress management has been shown to lower the stress levels of employees (Timmerman, Emmelkamp, & Sanderman, Citation1998; Williams et al., Citation2017). Studies show that stress management intervention programmes are effective in reducing stress at a lower cost than individual face-to-face interventions, which can be expensive and resource demanding (Richardson & Rothstein, Citation2008). Due to the lack of resources within the health-care sector, especially when it comes to health promotion, digitalisation has become a huge developmental area, and websites and mobile and web applications which target behaviour change with respect to different health behaviours are common.

A review of 37 websites on health behaviour change for the prevention and management of chronic disease found several weaknesses in the programmes; few of them were theory-based or theory-driven, many were not individually tailored or evidence-based and few had an empirical basis for tailoring or an evaluation plan or possibilities for feedback (Evers, Prochaska, Driskell, Cummins, & Velicer, Citation2003). Even though the study by Evers et al. is relatively old, most current web-based self-management programmes for stress-related problems are still not tailored or highly interactive.

Many current web-based programmes for stress management commonly use one or only a few techniques for behavioural change and stress management, and few, if any, of the current programmes use a wider range of evidence-based techniques for stress management. Thus, they are difficult to tailor to the individual’s specific needs for stress management (Heber et al., Citation2013; Yamagishi et al., Citation2007). Studies have also reported low adherence to the web-based programmes in several areas (Kelders, Kok, Ossebaard, & Van Gemert-Pijnen, Citation2012). To overcome adherence problems, studies suggest that interactivity, feedback, and tailoring are important in attaining behaviour change (Carlbring et al., Citation2010; Heber et al., Citation2013; Webb, Joseph, Yardley, & Michie, Citation2010; Zetterqvist, Maanmies, Ström, & Andersson, Citation2003).

Three essential factors have been identified to take into account when developing web-based self-management programmes supporting behaviour change: the theoretical framework of the programme, how evidence-based behaviour change techniques are incorporated into the programme and how the programme is delivered (Webb et al., Citation2010). Studies which report the use of theory when developing web-based programmes to support behaviour change show larger effects than studies which are not theory-based (Webb et al., Citation2010). Regarding programme delivery, fully automated self-management programmes have been shown to have positive effects on perceived stress (Williams, Hagerty, Brasington, Clem, & Williams, Citation2010). Compared to the more common therapist-guided programmes, more is demanded with respect to technical solutions and the pedagogical design in a fully automated programme (Hedman, Carlbring, Ljótsson, & Andersson, Citation2014). Interventions which are automated and thus available without contact with a therapist can be completed without clinical assessment and therefore reach a large population at a low cost (Hedman et al., Citation2014). The related costs are usually lower for automated programmes than for face-to-face interventions, but the drop-out rate is often higher in programmes involving no contact with therapists (Kelders, Citation2012 ; Van Straten, Cuijpers, & Smits, Citation2008).

Earlier research has not clearly described how behaviour change techniques are incorporated into stress management programmes. Coding the included behaviour change techniques according to the Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy could clarify the content of a programme and thus contribute to the transparency of the intervention (Michie et al., Citation2013). The taxonomy was developed to standardise definitions of behaviour change techniques used in interventions to more easily identify techniques contributing to effective interventions (Abraham & Michie, Citation2008).

There is a need for advanced web-based self-management programmes founded on current evidence to prevent stress-related health problems. However, way to take such development from an idea to a ready-to-use product, where evidence within the field regarding content, tailoring, interactivity and individual feedback are taken into account, have not been described in the literature. Thus, the aim of this study was to describe the systematic development of an evidence-based, tailored, interactive web application for the self-management of work-related stress. The aim was also to test the application’s usability with respect to how to proceed through the programme.

2. Development of the web application

2.1. Methods

The development process (described in a flowchart, Figure ) involved three phases. Steps 1–3 represent phase I, steps 4–7 represent phase II and steps 8–10 represent phase III.

2.1.1. Phase I

Phase I (steps 1–3) was founded on a state-of-the-art literature review (Grant & Booth, Citation2009) of current evidence in the fields of stress management, behaviour change, and web-based behaviour change in order to decide upon the theoretical framework and content for the programme. In steps 1 and 2, scientific papers and books which were prominent in the fields were identified (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; Michie, Abraham, Whittington, McAteer, & Gupta, Citation2009; Webb et al., Citation2010). Based on these works, further searches were conducted.

Based on the evidence found, discussions within the research team led to decisions on the theoretical framework and on which stress management strategies and behaviour change techniques could be feasible in a web-based self-management programme.

Step 3 included the development of tailoring to meet individuals’ specific needs for stress management. A tailoring tool, the 32-item Symptoms of Stress Survey (SySS), was developed for this purpose. The SySS was informed by the Calgary Symptoms of Stress Inventory (Carlson & Thomas, Citation2007), the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire (Nordin, Åkerstedt, & Nordin, Citation2013), the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamark, & Mermelstein, Citation1983; Cohen & Williamson, Citation1988) and literature relevant to each stress management technique. The members of the research group worked individually and connected the stress-related symptoms from the SySS to the stress management strategies. A consensus within the research group was reached regarding the connecting of stress management strategies to the respective symptoms in the SySS.

2.1.2. Phase II

Phase II (steps 4–7) was the development process for a web application through which the programme for stress management strategies and behaviour change techniques could be delivered to users in a tailored manner. This phase also included the design of ways to present the content. A programmer, a web designer, an illustrator, and the interdisciplinary research team (experts in behaviour change, stress management, and information design) were all involved in the design process.

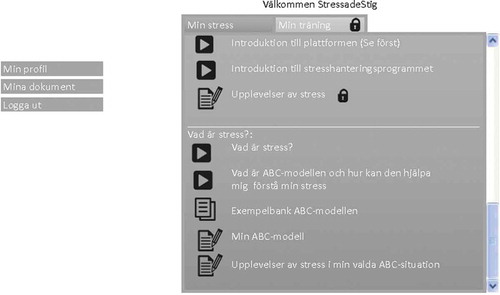

In order to achieve an overview of the algorithms, a conceptual model of the programme structure was developed (step 4). This model also made it easier to decide upon the logical order of the content and how to integrate the tailoring. The conceptual model was also the basis for a paper version of the web application, which showed all the functions of the future web application, such as a skeleton of menus, buttons, and where the assignments, tailoring and films would be found (step 5). The paper version (example in Figure ) was tested within the research team. It was also the instruction for ordering the application from a programmer. During the programming process, the programme structure was adjusted, and visual elements were discussed within the team, primarily with the expert in information design (the third author), and they were revised to create a programme which would promote intuitive use of the web application.

Figure 2. A paper version of the programme designed in Power Point (an example showing the psychoeducation section) (in Swedish). In the left column, a menu for personal information. In the right column, divided into two tabs, my stress (Min Stress) and my exercises (Min Träning).

Parallel to the development of the web application, all text material, for audio recording, films and stress management assignments was developed. The texts were based on the evidence from phase I and were revised by an expert in informational design and gender studies (the third author) (steps 7–8). One focus of the text design was to avoid stereotyping or reasserting heteronormative stereotypes (Eriksson & Göthlund, Citation2012; Robinson & Johnsson, Citation1997) in order to enhance the acceptability of the programme, but the main focus was on comprehensive text design and the creation of texts easy to read. Sixteen audio recordings were prepared, and 14 short films were developed and combined with sound recordings. An expert in informational design produced the four most central films: 10 of the 14 films were developed by the first and third authors. The images included in the films were also chosen with the aim of avoiding heteronormative stereotyping.

The graphics were designed based on information design principles (Mollerup, Citation2015). Several discussions within the research group and with the programmer and a web designer, led to the selection of the final graphics, colours and font.

2.1.3. Phase III

The Taxonomy for Behavior Change Techniques was used to code the content of behaviour change techniques to clarify how and where they were incorporated and to enhance the transparency of the programme for presentation purposes (step 8) (Michie et al., Citation2013).

In order to validate the content, progress and structure of the programme, it was presented to four experts in occupational health and rehabilitation (Step 9). The experts were asked whether anything was missing or left out and whether the structure of the programme was relevant. Each expert answered independently, and their comments were categorised into two categories: relevant or not relevant. The occupational health experts had different expertise: one licensed psychologist, one manager of one of the county council’s occupational health unit, one CEO of a private company delivering occupational health services and also responsible for the work environment and health section of the company, and one health strategist at a private company.

A possible end user was given access to the first version of the programme and was instructed to click through the programme while the first author was present and note whether anything needed to use the programme was difficult to understand (step 10). The remaining bugs were identified and rectified.

2.2. Results for development of the web application

For the content of MSC regarding the theoretical framework, stress management strategies, tailoring, and behaviour change techniques coded according to the behaviour change taxonomy (Michie et al., Citation2013) see Table .

Table 1. Structure of My Stress Control (MSC) and content regarding how information is presented, stress management strategies, life-style change and behaviour change techniques included as well as coding according to the behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) (Michie et al., Citation2013)

2.2.1. Integration of theories in MSC

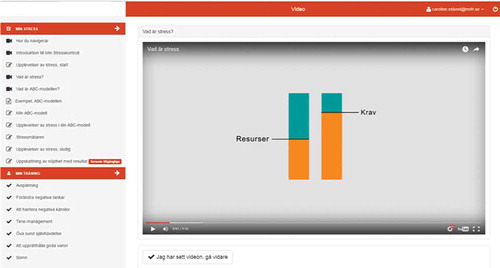

Three theories stand out in being used in successful web-based behaviour change interventions (Webb et al., Citation2010); these include Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) (Bandura, Citation1989), the Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behaviour (TRA/TPB) (Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, Citation1992), and the Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change (TTM/SoC) (Prochaska & DiClemente, Citation1992; Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, Citation2008). For the theoretical frame of programmes with a focus on stress, the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (TSC) (Folkman, Citation1984; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984) was also identified as important. TSC is a framework for understanding stress and coping and how they interact, with the main constructs being stress, primary and secondary appraisal, and coping. SCT links the individual, the behaviour and the environment in a reciprocal manner and can be seen as a more overarching theory for MSC. SCT is the basis for the psychoeducation module (see Table ), educating the user in how the resources of an individual and the physical and social environment and behaviour interact. SCT is also the foundation for the functional behavioural analysis in MSC. In this analysis, the Antecedent-Behaviour-Consequence Model (the ABC Model) supports the user in identifying social or physical antecedents triggering stress and in reflecting upon their own behaviour and the consequences the situation leads to. Self-efficacy is a central concept within SCT (Bandura, Citation1982). The stress management techniques learned for coping with stressful situations go through a gradation from those used at an easier level of performance where self-efficacy can be expected to be higher, to those used in situations where stress is prominent and self-efficacy may need to be increased. Central in TRA/TPB is identifying key behavioural beliefs and controlling those beliefs as determinants of behavioural intention (Madden et al., Citation1992). In MSC, increasing perceived control over new behaviour is central. Behavioural beliefs are addressed in the introduction films for each module. TTM and SoC provide tools for behaviour change in order to help the user transfer from stage to stage towards the maintenance of behaviour change, and SoC is also a tool to tailor the interventions according to the user’s readiness to change (see Table ).

2.2.2. Tailoring

Regarding the development of the tailoring tool, SySS, there was 100% consensus for three of the 32 items within the four-person research team regarding how the members connected the symptoms of stress to the stress management strategies. For the rest of the items of SySS, three of the members of the research team agreed regarding the connection of symptoms to a particular stress management strategy. For the details of tailoring in the programme, see Table .

2.2.3. Structure of the web application

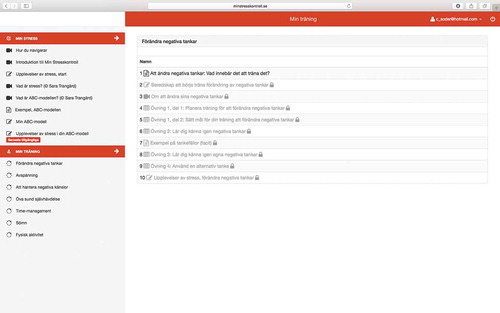

The conceptual model clarified the possible algorithms in the programme and the basis for the paper version (see Figure for an example). The model, in combination with discussions with the web-designer, programmer and expert in informational design, resulted in the structure of MSC (exemplified by one specific stress management module in Figure ). The structure of MSC, the content and the behaviour change techniques included in each module are shown in Table .

Figure 3. A screen dump from the change negative thinking module as an example of the structure (in Swedish). In the left column, the two tabs my stress and my exercises are placed under two menus. Overview function of current module in the centre. Personal information in a drop-down menu in the top right corner. This screen dump shows the introduction and psychoeducation under my stress (Min Stress) and shows the available stress management strategies under my exercises (Min Träning).

3. Validation of the content and structure by experts and a possible end-user

The occupational health experts had no objections to or suggestions for revisions to the programme content, progress or structure. Everything was regarded as necessary and relevant.

The first test of the programme with a single end user resulted in clarifications to the programme and the development of text in the introduction module on how to handle the programme.

3.1. Discussion for development of the web application

The development of MSC resulted in an information-rich, tailored and interactive web-based stress management programme based on evidence from multiple fields. The interactivity in MSC includes questionnaires, interactive activities, action planning, self-monitoring, tailored feedback and tasks to complete offline between sessions. The web application reacts to the users’ answers and choices in assignments and tailors the programme for each user. The users receive feedback with examples on how to solve some of the assignments related to specific stress management strategies after completing them. MSC is not similar to any existing programme in the stress management field, considering the tailoring and multi-tracked opportunities. It is built on a solid theoretical framework. The most central behaviour change techniques, integrated in every module, self-monitoring, goal-setting, re-evaluation of goals, feedback, and to prompt formulation of intention to change have also shown highest evidence in previous research (Michie et al., Citation2009). The information is provided in texts, films and audio recordings and is developed with a focus on text design and to not reassert stereotypes.

In contrast to earlier programmes, intervention transparency in the MSC is clarified by coding the behaviour change intervention (Michie et al., Citation2013). Additionally, the presentation of the structure of MSC (Table ) also enhances the transparency of this programme.

Despite existing guidelines, there has been a research gap with respect to a description of the development of behaviour change interventions, from idea to web-based product. Moreau, Gagnon, and Boudreau (Citation2015) described an application and adjustment of a programme-planning model (Kreuter, Farrell, Olevitch, & Brennan, Citation2000; Kreuter, Strecher, & Glassman, Citation1999) in a web-based behaviour change intervention in physical activity for adults with type 2 diabetes. The study by Moreau et al. proposed a model for developing web-based self-management programmes to handle health-related behaviour change, similar to that in our study, confirming the process we used. Nevertheless, to the development process our study adds the way in which a conceptual model of a programme is used as a basis for a paper version of a complete programme. In computer science paper prototypes are a well-known step in the design process (Virzi, Sokolov, & Karis, Citation1996). The development of a conceptual model of the flow through the programme and the availability of a paper version can guide other developers in using a less resource-demanding model in developing future web-based interventions. A paper prototype can also help identify problems early in the process.

From an ethical perspective, delivering web-based interventions in the area of mental health could be considered a challenge; thus, security also needed to be addressed during the development process. To prevent information being monitored by a third party, the information sent to and from the user should be encrypted according to SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) security mechanisms. Another ethical issue arises from the fact that symptoms of clinical depression and anxiety may overlap with stress. Persons with high scores on Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) may need other support, due to their more vulnerable condition. The screening in MSC ensures that the users are experiencing levels of stress that do not present clinical signs of depression or anxiety, for which the programme was not developed. HADS has the advantage of being one among few instruments for depression and anxiety which is validated for samples without a psychiatric diagnosis, thus it is reliable to be used for the present purpose.

The decisions made regarding the theoretical framework, the behaviour change techniques and the choices of how to deliver the programme were central to the development process and in agreement with previous research (Kelders et al., Citation2012; Michie et al., Citation2009; Webb et al., Citation2010). For example, studies reporting the use of the TRA/TPB show larger effects on behaviour change than those using other theories (Webb et al., Citation2010).

The stress definition by Lazarus (Citation1993) is still widely used and has been given a prominent position in contemporary works (e.g. Lovallo, Citation2016). The operationalisation of stress in PSS-14 (Cohen et al., Citation1983; Cohen & Williamson, Citation1988) is coherent in relation to Lazarus’s definition. Also, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) is widely used in research on stress management (e. g. Brinkborg, Michaneck, Hessel, & Berglund, Citation2011).

Regarding the included stress management strategies, the strength of the evidence varies. Some strategies’ effects have been studied in meta-analyses, for example pleasant activity scheduling (Mazzucchelli, Kane, & Rees, Citation2010), whereas others have a less evidence, for example assertiveness training (Galassi & Galassi, Citation1978; Imamura et al., Citation2014). In a recent meta-analysis of employee burnout, it was found that high-quality studies on interventions are scarce and that the interventions need to be more tailored than existing interventions (Maricutoiu, Sava, & Butta, Citation2014). One further problem is that there is no consensus in the literature on how to label different stress management strategies (Ong, Linden, & Young, Citation2004). For example, mindfulness includes cognitive restructuring and relaxation techniques. This makes it difficult to compare stress management interventions in order to decide upon the most effective strategies.

MSC focuses on the individual and his or her coping strategies and does not focus on the organisational aspects, which has also been in association with risk factors for developing stress (Siegrist et al., Citation2013). However, the organisational perspective is discussed in the psychoeducation module, and the users are informed of how stress-related problems can evolve from organisational injustices and poor work-related environments.

The aim to tailor the intervention led to the development of the SySS that steers users towards stress management strategies relevant to the symptoms of stress for each user. There is a lack of evidence regarding which types of skills or stress management strategies are most efficacious for different stress-related symptoms. However, it is argued that more physical symptoms should be tackled with muscularly oriented methods, and cognitive and emotional symptoms should be addressed with strategies including components closer to cognitive and behavioural approaches (Lehrer, Carr, Sargunaraj, & Woolfolk, Citation1994). Because of the limited evidence for tailoring stress management strategies based on stress symptoms, certain techniques will be recommended to the users, but the users will also have the opportunity to choose from all strategies in the programme. A limitation in the tailoring was that the SySS’s psychometric properties have not been studied. Nevertheless, the SySS is built on reliable and valid instruments (Cohen, Citation1983 ; Carlson & Thomas, Citation2007; Nordin et al., Citation2013). The face validity of the SySS was investigated through connecting the stress management strategies to the symptoms by the research group. The conformity was high in the decisions about which symptoms were connected to which stress management strategies. Users’ experiences of the tailoring will be studied when evaluating MSC. The use of the TTM and, more specifically, of the SoC for further tailoring was influenced by a review (Knittle, De Gucht, & Maes, Citation2012) in which self-management programmes were described as ideally including a motivation and intention formation stage, a stage of active goal pursuit, and a stage for maintenance. The condensing of the SoC into these stages in MSC also made the tailoring more manageable in terms of the potential number of tracks for each user.

The use of a programme can lead to behaviour change and symptom improvement through different mechanisms of change, and behaviour change can be sustained through treatment maintenance (Ritterband, Thorndike, Cox, Kovatchev, & Gonder-Frederick, Citation2009). MSC supports the user in learning stress management strategies relevant to the person’s specific stress-related problem, which might also produce positive emotions towards the programme. Positive emotions towards web-based interventions have been described as being important for adherence (Ludden, Van Rompay, Kelders, & Van Gemert-Pijnen, Citation2015). The fact that the programming was done using a responsiveness design (Marcotte, Citation2014) can also enhance the availability for users, as they can work in the programme on several devices, thus positively affecting adherence. MSC is an extensive programme and can be considered overwhelming for users; this may have an adverse effect on stress levels and also on adherence. Therefore, it is clarified in the programme that the modules, the films and the web-based assignments are not mandatory for completion of the programme

4. Usability test

In the final step, 15 possible end users were given access to the final version of the programme so the usability of the platform could be studied. More specifically, what was studied was whether the possible end users understood how to proceed to the programme end.

4.1. Methods

The possible end users were recruited from the staff at a university. They received oral and written information about the aim of the study, were given the change to ask questions about the study and were given access to the programme after they signed an informed consent. The possible end users were instructed to proceed through the programme at a more rapid speed than what the programme had originally been designed for. Inclusion criteria for the participants in the usability test were a perceived stress score measured with PSS-14 (Cohen et al., Citation1983; Cohen & Williamson, Citation1988), of 17 or higher (Brinkborg et al., Citation2011), being employed, being 18–65 years old, being able to speak and understand the Swedish language and consented to take part in the study. Exclusion criteria included currently being on sick-leave or scoring 11 or more on either of the subscales on the HADS (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983). The study participants were monitored by the first author through an administration tool in the web application regarding how far in the programme they came. After they finished participation the participants were also asked whether they had reached the final module of the programme.

4.2. Results of the usability test

Fifteen persons agreed to test the usability of the programme. One person was excluded due to high scores on HADS. Regarding the 14 remaining participants, 7 ended their participation before finishing the programme. The reasons for ending participation early included a lack of time and the extensiveness of the programme (four persons), sick leave (two persons) and an unknown reason (one person). The participants went through the programme over approximately 7–9 weeks. Of the remaining seven participants, three finished the programme and reached the final module. However, four participants did not receive the final module; these four persons did not understand that there were more modules available which could be reached by completing certain assignments. The two persons who quit the programme due to sick leave were considered to have fulfilled the exclusion criteria. The actual dropout rate was than 42% (5 persons of the remaining 12). The results clearly indicate that details in the programme and platform need to be further developed in order to enhance the usability of the programme.

4.3. Discussion for the usability test

One focus during the development of MSC was to find strategies to prevent dropping out from the programme and to help participants adhere to new behaviours using techniques identified as supporting behaviour change (Michie et al., Citation2009). The dropout rate was high, although somewhat lower than reported in earlier studies (Kelders et al., Citation2012) where an average of 50% of the participants did not complete the interventions.

In four of 14 cases, the possible end users working with the programme had trouble finding their way through it, although the focus for the design of the programme elements was simplicity (Mollerup, Citation2015). In this case simplicity means that using and understanding the visual elements on the platform should be intuitive and thus that the platform should be easy to understand without instructions in how to use it (Mollerup, Citation2015). At some point, this was not enough. Thus, the programme must be further developed to enable the users to more easily understand the structure of the programme. Having an understanding of the programme structure could facilitate the users in adhering to the programme and should therefore be further developed.

5. Conclusion development process and usability test

MSC is a unique programme in the stress management field, but it must be further developed. However, the development process contributes to filling a gap in the literature regarding how to develop evidence-founded, complex web-based interventions for stress management on the web. This study could guide researchers in the area of web-based intervention development regarding how to accomplish such developmental processes. Although developed from the evidence in multiple fields, the web-application would benefit of further development to support users to reach the end module.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interest. This study was reviewed and approved by the regional ethics committee in Uppsala, Sweden, January 20th, 2016 (Dnr 2015/555).

Cover image

Source: Author.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank Olle Hällman for his contributions to this project regarding the programming and participation in the designing of visual elements as well as for his thoughtful comments on the content. The research team would also like to thank Sara Trangärd for her contributions regarding the four most central films included in the web application and for her input and knowledge of design principles that was used in all films included in the web application.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Caroline Eklund

This study was conducted by a multidisciplinary research team. The first and last authors are physiotherapists working within the field of behavioural medicine. Caroline Eklund is a PhD student whose main interest is in supporting individuals performing health-related behaviour change where various stressors hinder starting a new behaviour.

Anne Söderlund is a professor in physiotherapy whose main focus is on behaviour change when the stressor is persistent pain.

Magnus L. Elfström is a licensed psychologist and associated professor in psychology. One of his research fields is stress management.

Yvonne Eriksson is a professor in information design. Her research areas are visual communication, with a focus on perceptual and cognitive processes involved in interpretation of visuals, and gender issues related to visual studies. This study is part of a wider project to develop and evaluate a web-based self-management programme for the handling of work-related stress.

References

- Abraham, C., & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27(3), 379–387. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184.

- Brinkborg, H., Michaneck, J., Hessel, H., & Berglund, G. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of stress among social workers: A randomized controlled trial. Behaiour Research and Therapy, 49(6–7), 389–398. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.009

- Carlbring, P., Maurin, L., Törngren, C., Linna, E., Eriksson, T., Sparthan, E., … Andersson, G. (2010). Individually-tailored, internet-based treatment for anxiety disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behaiour Research and Therapy, 49(1), 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.002

- Carlson, L. E., & Thomas, B. C. (2007). Development of the calgary symptoms of stress inventory (C-SOSI). International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 14(4), 249–256. doi:10.1080/10705500701638484

- Cohen, S., Kamark, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

- Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. M. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the united states. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.) The social psychology of health. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Eriksson, Y., & Göthlund, A. (2012). Möten med bilder - Att tolka visuella uttryck (Vol. 2:1). Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

- Evers, K., Prochaska, J., Driskell, M. M., Cummins, C., & Velicer, W. (2003). Strengths and weaknesses of health behavior change programs on the Internet. Journal of Health Psychology, 8(1), 63–70. doi:10.1177/1359105303008001435

- Folkman, S. (1984). Personal control and stress and coping process. A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 122–147.

- Galassi, M. D., & Galassi, J. P. (1978). Assertion: A critical review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15(1), 16–29. doi:10.1037/h0085834

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Häfner, A., & Stock, A. (2010). Time management training and perceived control of time at work. The Journal of Psychology, 144(5), 429–447. doi:10.1080/00223980.2010.496647

- Heber, E., Ebert, D. D., Lehr, D., Nobis, S., Berking, M., & Riper, H. (2013). Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a web-based and mobile stress management intervention for employees: Design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 13(655). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-655

- Hedman, E., Carlbring, P., Ljótsson, B., & Andersson, G. (2014). Internetbaserad psykologisk behandling - Evidens, indikation och praktiskt genomförande. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Imamura, K., Kawakami, N., Furukawa, T. A., Matsuyama, Y., Shimazu, A., Umanodan, R., & Kasai, K. (2014). Effects of an internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT) program in Manga format on improving subthreshold depressive symptoms among healthy workers: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 9(5), e97167. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097167

- Jacobson, E. (1987). Progressive Relaxation. The American Journal of Phychology, 100(3–4), 522–537. doi:10.2307/1422693

- Kelders, S. M., Kok, R. N., Ossebaard, H. C., & Van Gemert-Pijnen, J. E. (2012). Persuasive system design does matter: A systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(6), e152. doi:10.2196/jmir.2104

- Knittle, K., De Gucht, V., & Maes, S. (2012). Lifestyle- and behaviour-change interventions in musculoskeletal conditions. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 26(3), 293–304. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2012.05.002

- Kreuter, M., Farrell, D., Olevitch, L., & Brennan, L. (2000). Tailoring health messages: Customizing communication with computer technology. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Kreuter, M. W. K., Strecher, V. J., & Glassman, B. (1999). One size does not fit all: The case for tailoring print materials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 21(4), 276–283. doi:10.1007/BF02895958

- Kushnir, T., Malkinson, R., & Ribak, J. (1998). Rational thinking and stress management in health workers: A psychoeducational program. International Journal of Stress Management, 5(3), 169–178. doi:10.1023/A:1022941031900

- Lazarus, R. (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55(3), 234–247.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY, US: Springer.

- Lehrer, P. M., Carr, R., Sargunaraj, D., & Woolfolk, R. L. (1994). Stress management techniques: Are they all equivalent, or do they have specific effects? Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 19(4), 353–401.

- Lindegård, A., Jonsdottir, I. H., Börjesson, M., Lindwall, M., & Gerber, M. (2015). Changes in mental health in compliers and non-compliers with physical activity recommendations in patients with stress-related exhaustion. BMC Psychiatry, 4(15), 272. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0642-3

- Lindwall, M., Gerber, M., Jonsdottir, I. H., Börjesson, M., & Ahlborg, G. (2013). The relationships of cange in physical activity with change in depression, anxiety and burnout: A longitudinal study of Swedish healthcare workers. Health Psychology, 33(11), 1309–1318. doi:10.1037/a0034402

- Lovallo, W. R. (2016). Stress and health: Biological and psychological interactions (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Ludden, G., Van Rompay, T., Kelders, S. M., & Van Gemert-Pijnen, J. E. (2015). How to increase reach and adherence of web-based interventions: A design research viewpoint. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(7), e172. doi:10.2196/jmir.4201

- Madden, T. J., Ellen, P. S., & Ajzen, I. (1992). A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(1), 3–9. doi:10.1177/0146167292181001

- Marcotte, E. (2014). Responsive web design (2nd ed.). New York: NY, US: A Book Apart.

- Maricutoiu, L. P., Sava, F. A., & Butta, O. (2014). The effectiveness of controlled interventions on employees’ burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal Fo Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(1), 1–27.

- Mazzucchelli, T. G., Kane, R. T., & Rees, C. S. (2010). Behavioral activation interventions for well-being: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(2), 105–121. doi:10.1080/17439760903569154

- Michie, S., Abraham, C., Whittington, C., McAteer, J., & Gupta, S. (2009). Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: A meta-regression. Health Psychology, 28(6), 690–701. doi:10.1037/a0016136

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., … Wood, C. E. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

- Mollerup, P. (2015). Simplicity: A matter of design. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

- Moreau, M., Gagnon, M. P., & Boudreau, F. (2015). Development of a fully automated, web-based, tailored intervention promoting regular physical activity among insufficiently active adults with Type 2 diabetes: Integrating the I-Change model, self-determination theory, and motivational interviewing components. JMIR Research Protocols, 4(1), e:25.

- Norcross, J. C., Krebs, P. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (2011). Stages of Change. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 143–154. doi:10.1002/jclp.20758

- Nordin, M., Åkerstedt, T., & Nordin, S. (2013). Psychometric evaluation and normative data for the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire. Sleep and Biological Rhytms, 11(4), 216–226. doi:10.1111/sbr.12024

- Nyberg, S. T., Fransson, E. I., Heikkilä, K., Alfredsson, L., Casini, A., Clays, E., … Kivimäki, M. (2013). Job strain and cardiovascular disease risk factors: Meta-analysis of individual-participant data from 47,000 men and women. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e67323. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067323

- OECD. (2013). Mental health and work: Sweden. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264188730-en:

- Ong, L., Linden, W., & Young, S. (2004). Stress management what is it? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(1), 133–137. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00128-4

- Paech, J., Luszczynska, A., & Lippke, S. (2016). A rolling stone gathers no moss - the long way from good intentions to physical activity mediated by planning, social support and self-regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(7), 1024. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01925

- Ponce, A. N., Lorber, W., Paul, J. J., Esterlis, I., Barzvi, A., Allen, G. J., & Pescatello, L. S. (2008). Comparisons of varying dosages of relaxation in a corporate setting: Effects on stress reduction. International Journal of Stress Management, 15(4), 396–407. doi:10.1037/a0013992

- Prochaska, J., & DiClemente, C. (1992). Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Progress in Behavior Modification, 28, 184–218.

- Prochaska, J., Redding, C., & Evers, K. (2008). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In K. Glanz, B. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education - Theory, research, and practice (Vol. 4). San Francisco, CA: John Wile & Sons, Inc.

- Richardson, K. M., & Rothstein, H. R. (2008). Effects of occupationeal stress management intervention programs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(1), 69–93. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.69

- Ritterband, L., Thorndike, F., Cox, D., Kovatchev, B., & Gonder-Frederick, L. (2009). A behavior change model for internet interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38(1), 18–27. doi:10.1007/s12160-009-9133-4

- Robinson, M. D., & Johnsson, J. T. (1997). Is it emotion of is it stress? Gender stereotypes and the perception of subjective experience. Sex Roles, 36(3/4), 235–258. doi:10.1007/BF02766270

- Sandmark, H. (2007). Work and family: Associations with long-term sick-listing in Swedish women - a case-control study. BMC Public Health, 11(7), 287. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-287

- Siegrist, J., McDaid, D., Freire-Garabal, M., & Levi, L. (2013). Declaration of the Santiago de Compostela conference, July 18. Paper presented at the Economy, Stress and Health, University of Santiago de Compostela

- Thiart, H., Lehr, D., Ebert, D. D., Berking, M., & Riper, H. (2015). Log in and breathe out: Internet-based recovery training for sleepless employees with work-related strain - results of a randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health, 41(2), 164–174. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3478

- Timmerman, I. G. H., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., & Sanderman, R. (1998). The effects of a stress management training program in individuals at risk in the community at large. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(9), 863–875.

- Van Daele, T., Hermans, D., Van Hudenhove, C., & Van Den Bergh, O. (2012). Stress reduction through psychoeducation: A meta- analytic review. Health Educ Behav, 39(4), 474–485. doi:10.1177/1090198111419202

- Van Straten, A., Cuijpers, P., & Smits, N. (2008). Effectiveness of a web-based self-help intervention for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 10(1), e7. doi:10.2196/jmir.954

- Virzi, R. A., Sokolov, J. L., & Karis, D. (1996). Usability problem identification using both low- and high-fidelity prototypes. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

- Webb, T., Joseph, J., Yardley, L., & Michie, S. (2010). Using the internet to promote health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of felivery on efficacy. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(1), e4. doi:10.2196/jmir.1587

- Welbourne, J. L., Eggerth, D., Hartley, T. A., Andrew, M. E., & Sanches, F. (2007). Coping strategies in the workplace: Relationships with attributional style and job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(2), 312–325. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2006.10.006

- West, D. J., Horan, J. J., & Games, P. A. (1984). Component analysisi of occupational stress inoculation applied to registered nurses in an acute care hospital setting. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(2), 209–218. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.31.2.209

- Williams, A., Hagerty, B. M., Brasington, S. J., Clem, J. B., & Williams, D. A. (2010). Stress Gym: Feasibility of deploying a web-enhanced behavioral self-management program for stress in a military setting. Military Medicine, 175(7), 487–493.

- Williams, S. P., Malik, H. T., Nocolay, C. R., Chaturvedi, S., Darzi, A., & Purkayastha, S. (2017). Interventions to improve employee health and well-being within health care organizations - a systematic review. Journal of Healthcare Risk Management. doi:10.1002/jhrm.21284

- Yamagishi, M., Kobayashi, T., Kobayashi, T., Nagami, M., Shimazu, A., & Kageyama, T. (2007). Effect of web-based assertion training for stress management of Japanese nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 15(6), 603–607. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00739.x

- Zetterqvist, K., Maanmies, J., Ström, L., & Andersson, G. (2003). Randomized controlled trial of Internet-based stress management. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 32(3), 151–160. doi:10.1080/16506070302316

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Journal, 67(6), 361–370. doi:10.1111/acp.1983.67.issue-6