Abstract

Background

Health education alone has a limited impact on HIV prevention programs, possibly because it does not systematically target social and cognitive factors that affect condom use.

Objectives

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness and methodological quality of HIV prevention interventions, which targeted factors related to social cognitive models (SCM) in the Sub-Saharan context.

Method

Ten online databases were searched using prespecified terms. Data extraction and quality assessment (on a 0–8 scale) were carried out and study results were critically described.

Results

Eight studies meeting the inclusion criteria were identified and reviewed. Three interventions showed significant effects on condom use. The most targeted SCM factors were communication skills and self-efficacy. The average methodological quality score was 5.75.

Conclusion

There is a need to use other intervention methods targeting SCM determinants of condom use and to improve the quality of the assessment tools, to increase condom use towards HIV prevention.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

HIV is one of the deadliest infections exist, mainly in the Sub-Sahara. In recent years, development was achieved in the shape of medical means. Alongside these efforts, other means were used in the prevention phase through education and behavior change.

Nevertheless, analyzing the efforts to encourage healthy behavior when it comes to HIV prevention show that the use of condom as the main tool for HIV prevention is still not used due to several barriers.

A major barrier to adopt healthy behavior and use condoms are social and cognitive elements. These elements, such as social pressure and attitude toward the condom decreasing the probability to use condoms.

Reviewing interventions conducted in the Sub-Sahara, which were using validated models relied on social cognitive components, will expose the need to enlarge the use of these models in order to increase condom use.

Conflict of interest

Author A declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author B declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author C declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author D declares that he has no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

1. Introduction

Studies show that the prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is declining, with exceptions in East Europe and Central Asia among drug users, in young women in Sub-Saharan Africa, and young men who have sex with men (Beyrer & Abdool Karim, Citation2013). In parallel to these trends, the introduction of Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART) has reduced the mortality from HIV in some African countries (Chihana et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, a major factor in the efforts to prevent HIV infection is the need to increase protected sex, including condom use. Numerous studies have investigated the factors associated with condom use, which we shall now review.

1.1. Analysis of factors associated with condom use

The topic of factors associated with condom use has been extensively investigated and can be grouped in accordance with theories supported by empirical evidence.

Taking a theoretical approach, the identified factors can be mapped onto elements of two social cognitive models (SCM): The Health Belief Model (HBM; Rosenstock, Citation1974) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, Citation1991). Briefly, the HBM states that people’s perception about the susceptibility and severity of a disease, together with barriers for adopting preventive behaviors and their perceptions of benefiting from them, predict their eventual adoption of health behaviors. Focusing on the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) context, these barriers include perceived health problems resulting from condom use, hindered sexual interest, perceived effectiveness of condoms, and perceived reduced masculinity or sexual performance when condoms are used (Higgins, Hoffman, & Dworkin, Citation2010; Khan, Hudson-Rodd, Saggers, Bhuiyan, & Bhuiya, Citation2005; Sunmola, Citation2005). Further barriers include negative social stigma concerning condoms (Brüll, Ruiter, Wiers, & Kok, Citation2016; Janepanish, Dancy, & Park, Citation2011; Lammers, van Wijnbergen, & Willebrands, Citation2013), lack of privacy in purchasing condoms (Abdul-Kabir, Otupiri, & Opare, Citation2007; Roth, Satya, & Bunch, Citation2001), and communication factors such as condom use negotiation self-efficacy (Crosby et al., Citation2013; Jama Shai, Jewkes, Levin, Dunkle, & Nduna, Citation2010; Sayles et al., Citation2006). Additional barriers include the perception of inter-personal distrust if a condom is suggested (Goodman, Harrell, Gitari, Keiser, & Raimer-Goodman, Citation2016). In a study on 223 people in Kisumu, Kenya, barriers were the only significant correlate of condom use (Volk & Koopman, Citation2001).

The TPB posits that people’s attitudes about health behaviors, their perceived social norms and behavioral control over adopting a behavior, all predict people’s intention and eventual adoption of health behavior. Concerning condom use, Eggers et al. (Citation2016) recently found in three SSA regions that various elements of the TPB predict mostly intentions and to a lesser extent actual condom use(Brüll et al., Citation2016; Crosby et al., Citation2013; Jama Shai et al., Citation2010; Janepanish et al., Citation2011; Sayles et al., Citation2006; Goodman et al., Citation2016).

Further factors associated with condom use, unrelated to SCM include demographic background and knowledge. Demographic correlates include marital status, income (Janepanish et al., Citation2011), price, gender, and ethnicity (Bogart et al., Citation2011; Essien et al., Citation2010; Sunmola, Citation2005; Versteeg & Montagu, Citation2008), and relationship status (Abraham, Sheeran, & Henderson, Citation2014). Knowledge factors include, for instance, knowing one’s own HIV status (Cherutich et al., Citation2012).

The main conclusions of the studies reviewed above are that social and cognitive barriers (misperceptions) should be targeted within programs and interventions in order to improve their potential success to significantly increase condom use. Moreover, there is a need to test the effectiveness of the SCM interventions alone, a test, which was not conducted in the review mentioned above (Wariki et al., Citation2012). As advocated by others, it is possible that multiple types of interventions may be needed to target SCM elements for increasing condom use (Hope, Citation2003; Kaufman, Cornish, Zimmerman, & Johnson, Citation2014; Ndabarora & Mchunu, Citation2014).

1.2. The limits of educational interventions for increasing condom use

Studies show that persistent condom use reduces the risk of contracting HIV. Specifically, in a systematic review of 14 studies, constant use of condoms was associated with an 80% reduction of HIV risk (Weller & Davis-Beaty, 2002); hence, this is a major form for preventing HIV, worldwide.

A major systematic review of studies done between 1980 and 2011 on condom use practice in SSA (Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2012) emphasized the need to understand the factors associated with male condom use in SSA. Maticka-Tyndale’s review points out the evident complexity of how male condom use is related to social and interpersonal dynamics, together with the definitions and boundaries of cultural and structural conditions. These boundaries highlight the influences of poverty, interpersonal relationships, and information, beliefs, and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS and towards condom use. Furthermore, her review’s conclusions, together with previous studies, show that education alone had little impact or no statistically significant effects on condom use (Gallant & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2004). A crucial possible reason for the failure of health education programs to increase condom use is that education and awareness alone do not systematically target social cognitive factors that play major roles in condom use, as we shall now see.

1.3. Effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions

Past systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining the effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions conducted with populations at risk, and in SSA youth specifically, showed a paucity of high quality studies and generally low effectiveness of interventions (Johnson, Michie, & Snyder, Citation2014; Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri, Citation2007; Magnussen, Ehiri, Ejere, & Jolly, Citation2004; Paul-Ebhohimhen, Poobalan, & Van Teijlingen, Citation2008; Speizer, Magnani, & Colvin, Citation2003). Further, reviews point to suboptimal study design, such as lack of a control group (Michielsen et al., Citation2010).

Importantly, few interventions included in past reviews targeted specifically social cognitive factors. These specific interventions aimed to alter misperceptions about a behavior, one’s self-efficacy and control over performing it or to change social norms concerning the behavior. For instance, a study in SSA students whose intervention targeted SCM factors showed that an HIV risk-reduction intervention led participants to report less unprotected vaginal intercourse and more frequent condom use than control participants (Heeren, Jemmott, Ngwane, Mandeya, & Tyler, Citation2013). Another study examined the effectiveness of the Malawi BRIDGE Program, which used social and behavior change elements to increase HIV testing and condom use. That study clearly underlined the importance of increasing communication skills, self-efficacy, and risk perception (Berendes & Rimal, Citation2011), all are elements of SCM (Kaufman et al., Citation2014). A recent meta-analysis, which included different types of interventions including those targeting SCM, found that these interventions as a whole reduced sexually transmitted infections (STI) (Wariki et al., Citation2012). However, that review did not focus solely on interventions focusing on SCM components.

To the best of our knowledge, no review has systematically evaluated the effectiveness of interventions that targeted specifically components of SCM, including personal barriers and social determinants, on condom use, in SSA populations.

1.4. Purpose of review

The aim of this study was to fill this gap and to systematically review the research addressing the effectiveness of interventions, which targeted social cognitive factors, on condom use. We specifically focused on samples from the general population of SSA, excluding high-risk populations, because the latter have unique SCM characteristics. Moreover, samples from the general population have not been sufficiently investigated.

2. Method

2.1. Inclusion criteria

Selection criteria included: (1) Interventions targeting at least one element of Social Cognitive Models of behavior change. These included interventions which taught communication skills, because these are solutions for overcoming impeding social norms in this context, which could otherwise reduce condom use, or studies teaching skills to increase self-efficacy for negotiating about and using condoms; (2) A control group, with/without randomization; (3) HIV Negative participants; (4) Sub-Saharan samples; (5) A sample from a population that is not at high-risk, such as men who have sex with men (MSM), female sex workers (FSWs), alcohol or drug users (IDUs), or sero-concordant couples; The present review excluded such samples because we were aiming to review studies from the general population, due to the different cognitive barriers these groups have and since in many SSA countries, the spread of HIV reaches epidemic levels in the general population; (6) Explicitly assessing condom use behavior rather than only intentions or attitudes concerning condoms; (7) Studies which were published since 2000, because interventions prior to this period focused primarily on knowledge and attitude change (Harrison, Newell, Imrie, & Hoddinott, Citation2010); and (8) Articles in English alone. Of note, since many SSA countries also use French as an official language, an additional search was conducted, using similar keywords in French yielded no new trials meeting our criteria.

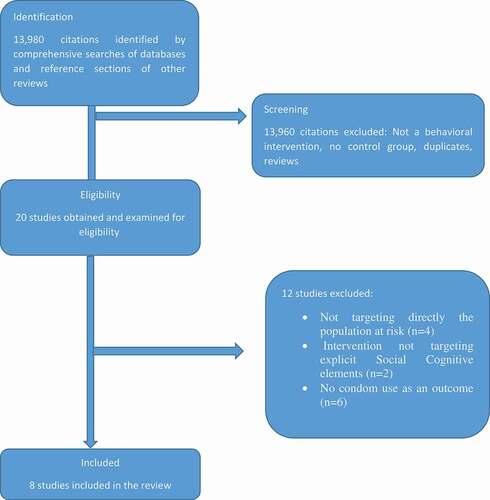

The systematic search and inclusion of studies were in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (www.prisma-statement.org; See Figure ).

Figure 1. Searching flow chart of reviewed intervention studies in accordance with PRISMA searching method (Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis).

A search of computerized databases indexing medical and social scientific literature was conducted, using the search engines EMBASE, Social Science Citation Index, PsychInfo, AIDSline, Pubmed, and Google Scholar. The following keywords were used in a variety of combinations using both “or” and “and” in the searching process: “intervention”, “condom use”, “barriers”, “Africa”, “Sub-Sahara”, “trust”, “embarrassment”, “self-efficacy”, “communication skills”, “cognitive model”, “social cognitive model”,and “HIV”. An example of results of a search tree conducted in Google Scholar is as following: The search words included “intervention”, “condom use”, “sub saharan Africa”, “barriers”, “control group” and “cognitive model”. This search yielded 40 citations of which 4 were deemed as relevant. These researches were eventually excluded due to irrelevancy to our review (e.g. not in SSA, high-risk population). A total of 13,980 titles were identified. The first selection was based on the title and on the abstract, and if both were debatable, the researchers read the full text of retained articles. In case of several publications concerning the same intervention study, we chose the latest or the one which provided the relevant data. In accordance with the inclusion criteria below, 20 articles remained and were double screened by two of the authors (EL, YG). Finally, eight studies fully met the inclusion criteria and were selected for this review (see Figure ).

2.2. Quality assessment

We created a score to assess the methodological quality of the reviewed studies using five criteria. The quality items were summed to yield a methodological quality score for each study as following: (1) Was the sample randomly selected from its population or was there an attempt to test its representativeness? 0-None. 1-One of the above. (2) Were the measures reliable and valid? 0-None, 1-Valid or Reliable, 2-Both. (3) Were groups randomly assigned, and were either cluster/stratified randomization or matching and randomization performed? 0-None of the above, 1-Randomization, 2- cluster/stratified randomization or matching + Randomization. (4) Were groups compared on background and baseline measures after randomization? 0-No, 1-Yes. (5) Were adequate statistical analyses used? 0-No, 1-Yes (Paired T-test, ANOVA or Logistic Regression), 2-there was also adjustments for confounders. Total methodological quality scores ranged from 0 to 8.

These items were derived from previously existing quality assessment scales (e.g. Gardner, Machin, & Campbell, Citation1986; Moher et al., Citation1995). Since some of the items were not relevant to the present review, we chose the relevant ones, which serve best the present-reviewed studies.

3. Results

The systematic search yielded eight intervention studies only. These included a total sample size of 19,745 participants, and the range of the sample size was 176–12,139. The mean sample size was 2468 participants. We have presented the studies chronologically by the year they were published.

Table 1. Researches reviewed.

Harvey, Stuart, and Swan (Citation2000) included 1,080 participants from seven pairs of secondary schools in South Africa, which were randomized to receive either written information on HIV/AIDS or a Drama Program (experimental condition). The experimental intervention included three phases and participatory techniques. The first phase included qualified teachers, actors or nurses presenting a play incorporating issues surrounding HIV/AIDS. The second phase included running a drama workshop, and the third phase was a celebratory open day focusing on HIV/AIDS through drama, song, poetry, dance, and posters, all prepared and presented by the students. These phases targeted elements such as self-efficacy about preventive behavior, perceived norms, and misconceptions. There was a significant increase in condom use in the experimental group from 38.2% at baseline to 55% at follow up (p < 0.01), while in controls there was no significant change. However, this difference disappeared after adjusting for confounders such as age, gender, and sexual experience. Though the results appeared to be promising, they inform us of the role of confounders, and that researchers may wish to match for certain confounders between experimental and control groups, to methodologically rather than only statistically control for their effects. This study reached a medium methodological quality level.

James et al. (Citation2005) conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 1168 secondary school students in South Africa. The participants were randomly allocated to study conditions at the school level: ten schools served as controls and nine as the intervention group. The intervention included printed media about knowledge, attitudes, communication skills, and behavior related to STIs. It was conducted through reading materials, which provided accurate information to participants, aimed at reducing misconceptions regarding STIs. This enabled the researchers to expose the participants to real life situations, risks, and solutions in a manner that they could identify with. Moreover, it also aimed to engender positive attitudes towards safe sexual practices and to enhance self-efficacy and adoption of negotiation skills. A range of outcomes was assessed over three time periods: Baseline, 3 weeks, and 6 weeks after baseline. Results showed that there were no significant differences between groups in condom use at follow up. This study adopted a strong methodological procedure, thus scoring high on quality level. Also, the intervention clearly targeted SCM elements relevant to the TPB, including attitudes, social norms (via communication skills), and self-efficacy in negotiating about sexually sensitive issues.

Karnell, Cupp, Zimmerman, Feist-Price, and Bennie (Citation2006) conducted a pre-/post-test quasi-experimental design among 661 ninth-grade students in five randomly selected schools in South Africa, three of which were randomly assigned to the intervention group. The observation unit was the individual learner. The intervention included three components, which were delivered via several methods. The centerpiece included four recorded monologues of fictional teenagers describing their life and dilemmas concerning having sex. Four peer leaders were elected from each class to receive 2 days of training, and they were responsible for delivering discussions within their groups about the recorded material (thus using the “training the trainers” method). The final component of the intervention included lessons exposing the groups to specific techniques for resisting pressure to have sex. This reflects the social pressure element of SCM. The students then had to practice role-playing and exercises enhancing the ability to plan ahead and to avoid risky situations. The measurement was done through a survey, which included 106 questions. This survey measured sexually related behaviors and several variables hypothesized to mediate the relationship between the intervention and behavioral outcome. At a five-month follow up, an increase of 4.4% was reported in using condoms during the last intercourse within the intervention group, while the comparison group showed 2.2% of change. These differences were not statistically significant. This study had a few distinguished elements, such as high awareness of language barriers and the use of multiple types of intervention methods, in addition to addressing social pressures. However, it is possible that part of the reason the effects on actual condom use was weak is that not all participants were sexually active. Indeed, the intention to use condoms were significantly affected by the experimental intervention only among the sexually active participants. Another reason for the ineffectiveness could be that the social skills element may have not systematically addressed personal cognitive barriers and misbeliefs about condoms or did not train people in the proper use of assertiveness to reject social pressures, both which we shall discuss below. This study scored highly on methodological quality.

Visser (Citation2007) evaluated the impact of a peer education program among 1918 participants in South-Africa through a quasi-experimental design. The study employed a controlled pre-post-test design, including 13 schools in the experimental group and 4 schools in the control group. The experimental program aimed to delay the onset of sexual activity and promote condom use among sexually active learners aged between 13 and 20 years old. The intervention included peer educators mobilizing the involvement of participants in the promotion of health behavior. It was done through a variety of activities such as performed plays, awareness days using different kinds of cultural means, discussions, and guest speakers. The underlying messages built into these activities used explicit condom use as the desired outcome through targeting communication skills related to sex. Results showed a non-significant increase of condom use in both control and experimental groups. In the experimental group, students in the age group of 13–15 years old reported significantly greater condom use in the post-test than at pre-test. An important aspect of this research is the fact that it evaluated the program at two levels. The first level was the process, i.e., focusing on how the program was implemented and integrated into the schools. The second level, and more relevant to the current review, was an evaluation of the actual outcomes and impact of the interventions. Moreover, the program enabled the peer educators to choose the platform on which the messages were delivered, thus encouraging creativity and activism among the learners and instructors. However, since it was not an RCT, this study reached a medium methodological quality score only.

Pronyk et al. (Citation2008) conducted a matched RCT in 220 young female participants in rural South-Africa for over two years. The women in the intervention and control groups were matched on age and poverty status. The intervention included a poverty-focused micro-finance element. The latter included learning communication skills, which could theoretically address social norms and interpersonal barriers of condom use. At follow up, 55% of the experimental group reported unprotected sex compared to 78% of those in the control group, and these differences were statistically significant in adjusted analyses. This intervention included a long follow up of two years and combined methods of intervention: Microfinance and skills training. Moreover, qualitative data obtained via interviews, which covered issues of gender inequality, was then addressed by the intervention. One limitation of this study, related to the research question of this review, is that the intervention did not target social cognitive elements only, rather it targeted several issues at once including micro-finance. This does not enable us to determine to which extent the social skills element was responsible for the observed effects. Nevertheless, this study scored highly on methodological quality due to the use of a matched-RCT design. The matching enables to methodologically, rather than statistically control for baseline group differences, which could occur after randomization.

Smith et al. (Citation2008) evaluated the effects of the HealthWise program among 2383 participants, conducted in South Africa through randomly allocating four schools at the pilot study stage as the experimental group and four matched control schools at the full evaluation stage. This “random selection” is not akin to an RCT. Another school was added as a backup to the control, leading to nine schools in total. Finally, 2383 participants from 8th and 9th grades took part in the trial, and their mean age was 14. The experimental program included lessons targeting social-emotional skills such as decision-making and anxiety, as well as skills surrounding substance use and sexual risk such as relationships, condom use, and HIV myths. The measurement included an explicit question about condom use frequency within the sexually active group. Results showed no significant differences between experimental and control groups over time. However, the HealthWise program included multiple components and targets in addition to sexual behavior. This could have affected the specificity and thus magnitude of the program’s effects on condom use, the main outcome observed of this review. This study carried a strong methodological process, thus scoring highly at the quality level.

Mathews et al. (Citation2012) conducted an RCT among a total of 80 schools from three cities (two in South Africa and one in Tanzania). The schools were matched on demographic background characteristics. The participants were 12–14-year-old young adolescents. The intervention included 11–17 h of classroom sessions delivered by teachers, where each session involved a presentation, group discussion, and role-plays. The contents of the lessons included topics such as general knowledge about STIs, gender roles, and condom use. Moreover, it also included aspects from SCM such as personal skills and negotiation skills, decision-making relevant to perceived risks and benefits, self-efficacy, as well as myths and misconceptions about HIV or condom use. The assessment included reports of sexual behavior and hypothesized mediators such as knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy. The main behavioral outcome was self-reported condom use. After adjusting for baseline characteristics, no significant group effect was shown at follow up (OR = 0.85, 0.58 to 1.26). This study included a few unique elements. First, the number of participants was much higher than in all the other studies. Despite the large sample size, no statistically significant effect was found on the primary outcome. This suggests that the intervention may had not been strong enough to affect this outcome. Second, conducting the research in two countries and using long term follow ups (up to 15 months in Cape Town) makes this study unique on one hand, but could have weakened the intervention effects on the other hand due to differences between the countries in culture, economy and structure, and the long follow-up which could have diluted any existing earlier effects. One important limitation was the use of different methods of data collection (i.e., paper and pencil or electronically) which reflects inconsistent methods and could have masked some of the effects or had reflected different socio-economic sub-groups. Regardless of this limitation, this study achieved the highest quality score among the studies reviewed here. Because of this, its lack of effects on condom use is a valid and reliable finding, and this raises serious doubts concerning the effects of such interventions on condom use.

Heeren et al. (Citation2013) conducted an RCT among 176 university students in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, between the ages of 18–24 years old. The interventions included eight sessions of 45 min each and involved interactive exercises. The experimental HIV risk-reduction intervention included explicit use of aspects related to SCM, mainly self-efficacy. The researchers stressed that social cognitive theory was the guideline of the research, and this was also manifested by explicitly using detailed questions in the measurement tool targeting behavioral change. Participants in the experimental HIV risk-reduction intervention reported fewer days on which they had unprotected sexual intercourse than did the participants in the control group. Moreover, participants in the experimental group were significantly more likely to report more frequent condom use during sex than those in the control group. The researchers analyzed the Intervention x Nationality interaction, revealing that the intervention led to a greater reduction in unprotected intercourse among the non-South African students in comparison to South African students, enabling a comparison of the effects of the interventions within and across cultures. This trial reached a medium quality score on methodology, mainly because the researchers performed only a partial randomization process and only a partial representativeness process.

4. Discussion

This article reviewed intervention studies aimed at increasing condom use in the Sub-Sahara, in which the interventions targeted elements of main SCM known to strongly affect condom use. In total, eight such studies meeting our relatively strict inclusion criteria were identified and reviewed. Three trials found that the experimental interventions showed significant results (Harvey et al., Citation2000; Heeren et al., Citation2013; Pronyk et al., Citation2008), which had several interesting characteristics. Each of them targeted a different population (women, secondary school students, and university students). Two of them (Heeren et al., Citation2013; Pronyk et al., Citation2008) had the smallest sample sizes compared to all other intervention studies, while the third study (Harvey et al., Citation2000) had the fourth smallest sample size. Having small sample sizes could have biased the results in favor of positive extreme scores. On the other hand, detecting statistically significant group effects in small samples can also indicate that the experimental interventions of those studies had relatively large effect sizes. Within the studies reviewed, four reported measurement of effect size (James et al., Citation2005; Pronyk et al., Citation2008; Smith et al., Citation2008; Visser, Citation2007). Heeren et al. (Citation2013) was reporting that due the nature of the trial (a pilot study), it had a statistical power to detect only relatively large effects, rather than typical effect sizes.

In addition, these three studies included a qualitative component within its data collection, which may have helped to guide the actual interventions and tailor them to the participants. Two important common components in these studies were the facts that these interventions included multiple phases together with a variety of intervention tools. These tools included the use of different delivery methods such as art, celebratory days, and a general wider involvement of the participants in the intervention, thus having participants take an active part. One example is peer-educators who were requested to initiate programs within their community, beyond one intervention session. Though these trials had significant results, they scored relatively below the average on methodological quality (5.75). This suggests that our confidence in these studies’ significant results may be compromised by their limited methodologies. Despite these limitations, it is possible that in order to obtain significant effects on condom use, interventions may require using a variety of tools together with greater community involvement. The engagement of the participants as active rather than passive learners might increase the adherence to healthy behaviors. Finally, when searching for a unique SCM component within these three interventions, that might have contributed to their significant effect compared to the other interventions, no such component could be identified. Of relevance, one study (excluded from this review due to lack of a control group) found that a psychological intervention (BRIDGE) affected both self-efficacy and condom use (Kaufman et al., Citation2014).

Observing the specific SCM factors targeted in the studies reviewed above, we found that communication skills were the most targeted factor. Five studies targeted this element (James et al., Citation2005; Karnell et al., Citation2006; Pronyk et al., Citation2008; Smith et al., Citation2008; Visser, Citation2007). Four studies targeted self-efficacy (Harvey et al., Citation2000; Heeren et al., Citation2013; James et al., Citation2005; Mathews et al., Citation2012). Negotiation skills were targeted by three studies (James et al., Citation2005; Karnell et al., Citation2006; Mathews et al., Citation2012).

Three targeted misconceptions (Harvey et al., Citation2000; Mathews et al., Citation2012; Smith et al., Citation2008). Perceived risk was targeted by two studies (Harvey et al., Citation2000; Mathews et al., Citation2012). In two of the three interventions that showed significance, self-efficacy was targeted. Nevertheless, we did not find any consistent pattern, which can highlight whether targeting a certain SCM factor within a certain intervention method can contribute to significant results. This also could have resulted from the methodological heterogeneity between studies.

Gender as an important component within the HIV context was examined through the review. All the studies in this review included gender as a demographic variable. Beside Pronyk et al. (Citation2008), which targeted specifically women, two other studies with interesting findings related to gender should be mentioned in this context. James et al. (Citation2005) found that the attitude towards persons infected with sexually transmitted infections or HIV/AIDS was significantly positively changed over time among males, but not among females, due to the intervention. Karnell et al. (Citation2006) found that females in the intervention group became more confident about their ability to refuse sex than females from the comparison group. Though based only on two studies, these results suggest that the effects of SCM interventions may differ according to gender. In males, SCM interventions may affect attitudes, while in females it affected refutation self-efficacy in the social and sexual context. Such gender differences need to be examined systematically in future studies.

Visser (Citation2007) stressed the importance of gender role in interventions targeting condom use and analyzed the findings in light of gender differences. Results of a meta-analysis of 18 non-SCM programs targeting reported condom use at last sexual encounter showed significant increases among males, while only three of these programs showed an impact on young women (Michielsen et al., Citation2010). Soskolne and Maayan (Citation1998) found that the correlates of condom use in multivariate analyses were different between men and women. It is possible that SCM interventions need to focus on different elements of SCM in men versus women. To do so, such interventions should include sufficient formative research to explore how gender roles and SCM factors affect sexual relationships in the given context in men and women separately (Kaufman & Pulerwitz, Citation2019).

These findings may strengthen the claim for using a variety of intervention types possibly tailored to each gender, as in one intervention discussed above. Moreover, these findings suggest that beside interventions targeting empowerment of negotiation skills and self-efficacy among females, researchers should also look for components which encourage males to change behavior and attitudes concerning condom use.

As seen in the flow chart of Figure , several other relevant intervention studies were found but were excluded due to not meeting our inclusion criteria. These included studies in which it was unclear whether the experimental intervention explicitly used elements from an SCM due to insufficient information. Additionally, some studies lacked clarity about the nature and existence of a control group. Though we had approached the authors of these studies, we failed to receive clear answers. The frequent methodological limitations were mainly the partial randomization process or lack of adequate statistical adjustments for possible baseline group differences on confounders. One manner for overcoming such baseline group differences beyond simple randomization is to perform a matched-RCT, which directly addresses such issues and may better detect group differences, even in small samples (e.g. Gidron, Davidson, & Bata, Citation1999). One of the trials reviewed above indeed used a similar matching procedure (Pronyk et al., Citation2008). Given the importance of gender in this context, we recommend to perform RCT and matching on gender.

It is clear that the interventions that were included in this review did not produce clear significant effects on condom use. Hence, it is difficult to determine whether targeting SCM elements is effective in increasing condom use within the Sub-Saharan context. Intervention studies targeting TPB factors (SCM) in high-income countries (Albarracín et al., Citation2005; Asare, Citation2015; Espada, Morales, Guillén-Riquelme, Ballester, & Orgilés, Citation2016; Gredig, Nideroest, & Parpan-Blaser, Citation2006), have also been conducted.

The interventions tailored to the SSA context face methodological challenges and require adjustments to the sociological and cultural contexts. These may include addressing culture-specific barriers, of importance to the HBM and SSA specific social norms of importance to the TBM. It is also possible that the studies reviewed above did not sufficiently strongly target SCM elements, thus yielding few positive results. Below, we will propose a method for possibly achieving this aim.

There is a need to expand and conduct more intervention studies targeting SCM elements within the SSA context with improved methodologies.

4.1. Implications for further research

None of the trials reported clinical effects of the interventions, such as HIV and STI infection. Clearly, interventions aim to affect these clinical outcomes, through reducing the risk of infection via condom use. Yet, the reviewed studies primarily aimed at altering behaviors to achieve prevention rather than aiming at clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, future intervention studies should consider adding clinical outcomes to their protocols.

Future interventions should consider qualitative tools such as focus groups or interviews to guide the understanding of the cognitive or social barriers people face about condom use. These can be supplemented by using standardized scales for assessing barriers concerning condom use such as the Saint Lawrence scale (St. Lawrence et al., Citation1999). We also recommend promoting community engagement in the intervention by using members of the community as active members of the intervention team. Alongside these recommendations, future studies should use multiple intervention “vehicles” to target a variety of barriers such as lessons, art, celebratory days, etc., as done in the study by Visser (Citation2007). Interventions should also be conducted during more than one phase to possibly have stronger and long-term effects.

Some of the studies measured the effectiveness of existing intervention programs such as the HealthWise program in South Africa (Smith et al., Citation2008) or the SATZ program both in South Africa and Tanzania (Mathews et al., Citation2012). This trend of evaluating and measuring the effectiveness of existing programs should continue in order to look for consistent improvement relied on evidence and possible adaptation to culture-specific needs.

Generally, we recommend to use more sensitive measurement tools, which are inquiring about the frequency of condom use, rather than categorical questions with YES/NO answers related to the last intercourse. Questioning about the frequency requires a higher cognitive effort from the participant, thus engaging the participants more. This also increases the sensitivity of the measure, thus increasing the statistical power to detect possible effects. Moreover, by doing that, researchers can track and monitor more easily the factors that are affecting the behavior change throughout the intervention process as it progresses with time. In addition, self-reporting about condom use carries multiple types of biases related to social desirability, particularly in the Sub-Saharan context. To partially overcome this important issue, the indirect condom use test (I-CUTE) was recently developed. This structured visual semi-projective test was found to be inversely correlated with condom use barriers and to be unrelated to social desirability (Levy, Gidron, & Olley, Citation2017).

Two studies which were excluded due to the fact that they did not meet the criteria of the current review, used superior methodology (e.g. strong randomization processes, which included cluster and matching) compared to most included studies and are recommended as a positive example for future trials (Thurman, Kidman, Carton, & Chiroro, Citation2016; Atwood et al., Citation2012).

Of the eight intervention studies described, six were conducted in schools. This selection bias could reflect higher accessibility to children and youth in educational settings and the relevance of HIV prevention to the educational context. In addition, all of the identified trials were conducted in South Africa. Two of them (Heeren et al., Citation2013; Mathews et al., Citation2012) included additional samples outside of South Africa as well (21.83% from the total sample size). These characteristics are limiting our ability to generalize the findings observed here to other Sub-Saharan populations, with different social and cultural factors and medical services, all affecting condom use. We recommend to widen the samples to other populations and to consider gender issues, and students and adults as specific samples.

Of greatest importance is the need to consider changing or strengthening the type of interventions, in order to actually change condom use behavior. It is possible that the studies reviewed above did not sufficiently alter social pressures and cognitive misbeliefs people have about condom use. We recommend to adopt the Psychological Inoculation (PI) method because it precisely targets these two topics relevant to SCM. The PI method includes exposure of people to challenging sentences (“the vaccine”) which reflect the person’s cognitive distortions and external social pressures he or she face about condom use, which people then have to systematically reject (“antibody response”). PI was found to prevent smoking, joining a driver that consumed alcohol and to reduce driving hostility and simulated accidents (Duryea, Ransom, & English, Citation1990; Gidron, Slor, Toderas, Herz, & Friedman, Citation2015). Furthermore, a pilot study found that PI significantly reduced condom barriers and increased condom negotiation self-efficacy in Nigerian women with HIV while an education control did not have such effects (Olley, Abbas, & Gidron, Citation2011). A recent larger study conducted among 59 students found a significant increase in the tendency to use a condom. This was followed by a smaller matched RCT (n = 22) showing PI to reduce condom use barriers (Levy et al., Citation2019). That study included the new validated indirect condom use test (I-CUTE; Levy et al., Citation2017) and a fully computerized version of PI without the need of counselors. Those results must be replicated in larger samples and then tested in relation to actual prevention of HIV infections.

Using such intervention methods within the Sub-Saharan context can widen the toolbox of researchers and communities towards HIV prevention both at the individual level and at the broader community and country levels.

Three major limitations occurred in the studies reviewed above concerning their theoretical basis. First, the theoretical basis of several interventions was lacking or not sufficiently explained. Second, the interventions were not only derived from SCM or solely targeting SCM components. Heeren et al. (Citation2013), Karnell et al. (Citation2006), and James et al. (Citation2005) are the only studies which explicitly based part of their intervention on SCM. Third, in some of the studies, the intervention was not clearly detailed in the article, limiting its replicability. These issues limit our ability to attribute the interventions’ effects on SCM only.

4.2. Limitations of the review

The main limitation of this review is the small number of identified trials. This could be explained by a few reasons. First, since some of the reviewed studies were not explicitly SCM derived, our search terms may have not identified other trails who used other terms in their interventions. Second, there were additional studies using SCM; however, their methodologies did not meet our inclusion criteria (e.g. no control group). Third, our research was looking for published papers in English or French alone due to linguistic constraints of the researchers. Studies published in other languages could have been missed.

The small number of trial was probably also due to the exclusion of studies focusing on groups at high-risk, such as FSWs, MSM, and IDUs. This exclusion was done because our primary objective was to look for barriers from the general population in order to understand better, what might be the effective prevention methods used in the lower risk population. The high-risk population requires additional and unique prevention methods compared to the general population (Chen et al., Citation2007; Smith, Tapsoba, Peshu, Sanders, & Jaffe, Citation2009).

During the search process, we used the geographical terms- “Africa” and “Sub-Sahara” rather being specific with countries’ names. The main reason for that is the assumption that a study which described an intervention in a Sub-Saharan country would mention in the article the terms “Africa” or “Sub-Sahara”.

While SCM are important, their elements do not explain much variance in actual condom use, as reported in a review (Bennett & Bozionelos, Citation2000). Other theories may need to consider additional reasons for condom non-use, such as gender and sexuality dynamics. Indeed, ways in which gender and sexuality dynamics operate in conjunction with socio-demographic issues such as poverty or accessibility to education can produce vulnerability to HIV infection through barriers to condom use (Auerbach et al., Citation2011; Hallman, Citation2005; Krishnan et al., Citation2008; Obermeyer, Citation2006; Robert, Citation2003; Visser, Citation2007). Thus, it is possible that targeting SCM alone is insufficient to yield a more robust and lasting effect on condom use. To achieve such effects, interventions should include economic and societal considerations in accordance with local values. Given the gender dynamics concerning condom use and HIV risk in SSA, future studies may also wish to conduct different interventions for separated by gender. These could consider SCM targets that are appropriate for each gender in SSA.

An additional angle to consider is derived from cognitive neuroscience, namely, executive function (decision-making, inhibitions, and working memory). Hall, Fong, Epp, and Elias (Citation2008) found a synergistic interaction between the intention and executive function in predicting health behaviors. Future interventions may wish to add tools for increasing executive function to their protocols.

5. Key research activities

Interventions targeting social-cognitive determinants of male condom use in low-risk Sub-Saharan populations: A Systematic Review.

Our group combines varied topics of research and encompasses heterogenetic backgrounds and fields. The main research of each researcher is different from the other, while the main common interest is health promotion, mainly through behavior.

Our expertise includes psychology, gender, anthropology, sociology, health, and medicine. The conjunction of these domains enables us to look for interdisciplinary approaches to existed challenges.

Separate developed research by members of the group includes, for instance, gender minorities at health-related risks, psycho-neuro-immunology, social cognitive models among other topics.

HIV as a medical phenomenon and the efforts to tackle it require vast approaches used to address. The systematic review we have conducted is looking into a gap we have identified in HIV prevention efforts, thus offering further ways to decrease its spread.

Abbreviations

| ART | = | Anti-Retroviral Therapy |

| FSW | = | Female Sex Workers |

| HBM | = | Health Belief Model |

| HIV | = | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| I-CUTE | = | Indirect Condom Use Test |

| IDU | = | Injected drug user |

| MSM | = | Men who have Sex with Men |

| PI | = | Psychological Inoculation |

| PRISMA | = | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| RCT | = | Randomized control trial |

| SCM | = | Social Cognitive Model |

| SSA | = | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| STI | = | Sexually Transmitted Infection |

| TPB | = | Theory of Planned Behavior |

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdul-Kabir, M., Otupiri, E., & Opare, D. (2007). Barriers to condom use among the youth in a municipal town in Ghana. Journal of the Ghana Science Association, 9(2), 76–17.

- Abraham, C., Sheeran, P., & Henderson, M. (2014). Exploring the relationship between socioeconomic status and cognitions in modelling antecedents of condom use. European Health Psychologist, 16(S), 372.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

- Albarracín, D., Gillette, J. C., Earl, A. N., Glasman, L. R., Durantini, M. R., & Ho, M. H. (2005). A test of major assumptions about behavior change: A comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 856–897. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856

- Asare, M. (2015). Using the theory of planned behavior to determine the condom use behavior among college students. American Journal of Health Studies, 30(1), 43.

- Atwood, K. A., Kennedy, S. B., Shamblen, S., Tegli, J., Garber, S., Fahnbulleh, P. W., … Fulton, S. (2012). Impact of school-based HIV prevention program in post-conflict Liberia. AIDS Education and Prevention, 24(1), 68–77. doi:10.1521/aeap.2012.24.1.68

- Auerbach, J. D., Parkhurst, J. O., & Cáceres, C. F. (2011). Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Global Public Health, 6(sup3), S293–S309.

- Bennett, P., & Bozionelos, G. (2000). The theory of planned behaviour as predictor of condom use: A narrative review. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 5(3), 307–326. doi:10.1080/713690195

- Berendes, S., & Rimal, R. N. (2011). Addressing the slow uptake of HIV testing in Malawi: The role of stigma, self-efficacy, and knowledge in the Malawi BRIDGE project. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 22(3), 215–228. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2010.08.005

- Beyrer, C., & Abdool Karim, Q. (2013, Jul). The changing epidemiology of HIV in 2013. Current Opinion in HIV AIDS, 8(4), 306–310. doi:10.1097/COH.0b013e328361f53a

- Bogart, L. M., Skinner, D., Weinhardt, L. S., Glasman, L., Sitzler, C., Toefy, Y., & Kalichman, S. C. (2011). HIV/AIDS misconceptions may be associated with condom use among black South Africans: An exploratory analysis. African Journal of AIDS Research, 10(2), 181–187. doi:10.2989/16085906.2011.593384

- Brüll, P., Ruiter, R. A., Wiers, R. W., & Kok, G. (2016). Identifying psychosocial variables that predict safer sex intentions in adolescents and young adults. Frontiers in Public Health, 4,74.

- Chen, L., Jha, P., Stirling, B., Sgaier, S. K., Daid, T., & Kaul, R.; International Studies of HIV/AIDS (ISHA) Investigators. (2007). Sexual risk factors for HIV infection in early and advanced HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic overview of 68 epidemiological studies. PloS One, 2(10), e1001. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001001

- Cherutich, P., Kaiser, R., Galbraith, J., Williamson, J., Shiraishi, R. W., Ngare, C., … Graham, S. M. (2012). Lack of knowledge of HIV status a major barrier to HIV prevention, care and treatment efforts in Kenya: Results from a nationally representative study. PloS One, 7(5), e36797. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036797

- Chihana, M., Floyd, S., Molesworth, A., Crampin, A. C., Kayuni, N., Price, A., … French, N. (2012). Adult mortality and probable cause of death in rural northern Malawi in the era of HIV treatment. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 17, e74–e83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02929.x

- Crosby, R. A., DiClemente, R. J., Salazar, L. F., Wingood, G. M., McDermott-Sales, J., Young, A. M., & Rose, E. (2013). Predictors of consistent condom use among young African American women. AIDS and Behavior, 17(3), 865–871. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-9998-7

- Duryea, E. J., Ransom, M. V., & English, G. (1990). Psychological immunization: Theory, research, and current health behavior applications. Health Education Quarterly, 17(2), 169–178.

- Eggers, S. M., Aarø, L. E., Bos, A. E., Mathews, C., Kaaya, S. F., Onya, H., & de Vries, H. (2016). Sociocognitive predictors of condom use and intentions among adolescents in three sub-saharan sites. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(2), 353–365. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0525-1

- Espada, J. P., Morales, A., Guillén-Riquelme, A., Ballester, R., & Orgilés, M. (2016). Predicting condom use in adolescents: A test of three socio-cognitive models using a structural equation modeling approach. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 35. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2702-0

- Essien, E. J., Mgbere, O., Monjok, E., Ekong, E., Abughosh, S., & Holstad, M. M. (2010). Predictors of frequency of condom use and attitudes among sexually active female military personnel in Nigeria. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ), 2, 77.

- Gallant, M., & Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2004, Apr). HIV prevention programs for African youth. Social Science& Medicine, 58(7), 1337–1351. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00331-9

- Gardner, M. J., Machin, D., & Campbell, M. J. (1986). Use of check lists in assessing the statistical content of medical studies. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 292(6523), 810–812. doi:10.1136/bmj.292.6523.810

- Gidron, Y., Davidson, K., & Bata, I. (1999). The short-term effects of a hostility-reduction intervention on male coronary heart disease patients. Health Psychology, 18(4), 416. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.18.4.416

- Gidron, Y., Slor, Z., Toderas, S., Herz, G., & Friedman, S. (2015). Effects of psychological inoculation on indirect road hostility and simulated driving. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 30, 153–162. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2015.01.012

- Goodman, M. L., Harrell, M. B., Gitari, S., Keiser, P. H., & Raimer-Goodman, L. A. (2016). Self-efficacy mediates the association between partner trust and condom usage among females but not males in a Kenyan cohort of orphan and vulnerable youth. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 20(2), 94–103.

- Gredig, D., Nideroest, S., & Parpan-Blaser, A. (2006). HIV-protection through condom use: Testing the theory of planned behaviour in a community sample of heterosexual men in a high-income country. Psychology and Health, 21(5), 541–555. doi:10.1080/14768320500329417

- Hall, P. A., Fong, G. T., Epp, L. J., & Elias, L. J. (2008). Executive function moderates the intention-behavior link for physical activity and dietary behavior. Psychology & Health, 23(3), 309–326. doi:10.1080/14768320701212099

- Hallman, K. (2005). Gendered socioeconomic conditions and HIV risk behaviours among young people in South Africa. African Journal of Aids Research, 4(1), 37–50.

- Harrison, A., Newell, M. L., Imrie, J., & Hoddinott, G. (2010). HIV prevention for South African youth: Which interventions work? A systematic review of current evidence. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 1. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-102

- Harvey, B., Stuart, J., & Swan, T. (2000). Evaluation of a drama-in-education programme to increase AIDS awareness in South African high schools: A randomized community intervention trial. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 11(2), 105–111. doi:10.1177/095646240001100207

- Heeren, G. A., Jemmott, J. B., III, Ngwane, Z., Mandeya, A., & Tyler, J. C. (2013). A randomized controlled pilot study of an HIV risk-reduction intervention for sub-Saharan African university students. AIDS and Behavior, 17(3), 1105–1115. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0129-2

- Higgins, J. A., Hoffman, S., & Dworkin, S. L. (2010). Rethinking gender, heterosexual men, and women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 435–445. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.159723

- Hope, R. K. E. M. P. E. (2003). Promoting behavior change in Botswana: An assessment of the peer education HIV/AIDS prevention program at the workplace. Journal of Health Communication, 8(3), 267–281. doi:10.1080/10810730305685

- Jama Shai, N., Jewkes, R., Levin, J., Dunkle, K., & Nduna, M. (2010). Factors associated with consistent condom use among rural young women in South Africa. AIDS Care, 22(11), 1379–1385. doi:10.1080/09540121003758465

- James, S., Reddy, P. S., Ruiter, R. A., Taylor, M., Jinabhai, C. C., Van Empelen, P., & Van Den Borne, B. (2005). The effects of a systematically developed photo-novella on knowledge, attitudes, communication and behavioral intentions with respect to sexually transmitted infections among secondary school learners in South Africa. Health Promotion International, 20(2), 157–165. doi:10.1093/heapro/dah606

- Janepanish, P., Dancy, B. L., & Park, C. (2011). Consistent condom use among Thai heterosexual adult males in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS Care, 23(4), 460–466. doi:10.1080/09540121.2010.516336

- Johnson, B. T., Michie, S., & Snyder, L. B. (2014). Effects of behavioral intervention content on HIV prevention outcomes: A meta-review of meta-analyses. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 66, S259–S270. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000235

- Karnell, A. P., Cupp, P. K., Zimmerman, R. S., Feist-Price, S., & Bennie, T. (2006). Efficacy of an American alcohol and HIV prevention curriculum adapted for use in South Africa: Results of a pilot study in five township schools. AIDS Education & Prevention, 18(4), 295–310. doi:10.1521/aeap.2006.18.4.295

- Kaufman, M. R., & Pulerwitz, J. (2019). When sex is power—Gender roles in sex and their consequences. In C. R. Agnew & J. J. Harman (Eds.), Power in close relationships. Cambridge University Press.

- Kaufman, M. R., Cornish, F., Zimmerman, R. S., & Johnson, B. T. (2014). Health behavior change models for HIV prevention and AIDS care: Practical recommendations for a multi-level approach. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 66(Suppl 3), S250. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000236

- Kaufman, M. R., Rimal, R. N., Carrasco, M., Fajobi, O., Soko, A., Limaye, R., & Mkandawire, G. (2014). Using social and behavior change communication to increase HIV testing and condom use: The Malawi BRIDGE project. AIDS Care, 26(sup1), S46–S49. doi:10.1080/09540121.2014.906741

- Khan, S. I., Hudson-Rodd, N., Saggers, S., Bhuiyan, M. I., & Bhuiya, A. (2005). Safer sex or pleasurable sex? Rethinking condom use in the AIDS era. Sexual Health, 1(4), 217–225. doi:10.1071/SH04009

- Kirby, D. B., Laris, B. A., & Rolleri, L. A. (2007). Sex and HIV education programs: Their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(3), 206–217. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.143

- Krishnan, S., Dunbar, M. S., Minnis, A. M., Medlin, C. A., Gerdts, C. E., & Padian, N. S. (2008). Poverty, gender inequities, and women's risk of human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 101–110.

- Lammers, J., van Wijnbergen, S. J. G., & Willebrands, D. (2013). Condom use, risk perception, and HIV knowledge: A comparison across sexes in Nigeria. HIV AIDS (Auckland), 5, 283–293.

- Levy, E., Gidron, Y., Deschepper, R., Olley, B., & Ponnet, K. (2019). Effects of a computerized psychological inoculation intervention on condom use tendencies in sub saharan and caucasian students: Two feasibility trials. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 7(1), 160–178. doi:10.1080/21642850.2019.1614928

- Levy, E., Gidron, Y., & Olley, B. O. (2017). A new measurement of an indirect measure of condom use and its relationships with barriers. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 14(1), 24–30. doi:10.1080/17290376.2017.1375970

- Magnussen, L., Ehiri, J. Ε., Ejere, H. O., & Jolly, P. Ε. (2004). Interventions to prevent HIV/AIDS among adolescents in less developed countries: Are they effective? International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 16(4), 303–324.

- Mathews, C., Aarø, L. E., Grimsrud, A., Flisher, A. J., Kaaya, S., Onya, H., … Klepp, K. I. (2012). Effects of the SATZ teacher-led school HIV prevention programmes on adolescent sexual behaviour: Cluster randomised controlled trials in three Sub-Saharan African sites. International Health, 4(2), 111–122. doi:10.1016/j.inhe.2012.02.001

- Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2012). Condoms in sub-Saharan Africa. Sexual Health, 9(1), 59–72. doi:10.1071/SH11033

- Michielsen, K., Chersich, M. F., Luchters, S., De Koker, P., Van Rossem, R., & Temmerman, M. (2010). Effectiveness of HIV prevention for youth in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials. Aids, 24(8), 1193–1202. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283384791

- Moher, D., Jadad, A. R., Nichol, G., Penman, M., Tugwell, P., & Walsh, S. (1995). Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: An annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Controlled Clinical Trials, 16(1), 62–73.

- Ndabarora, E., & Mchunu, G. (2014). Factors that influence utilisation of HIV/AIDS prevention methods among university students residing at a selected university campus. SAHARA-J, 11(1), 202–210. doi:10.1080/17290376.2014.986517

- Obermeyer, C. M. (2006). HIV in the Middle East. BMJ, 333(7573), 851–854.

- Olley, B., Abbas, M., & Gidron, Y. (2011). The effects of psychological inoculation on cognitive barriers against condom use in women with HIV: A controlled pilot trial. Sahara Journal, 8(1), 27–32. doi:10.1080/17290376.2011.9724981

- Paul-Ebhohimhen, V. A., Poobalan, A., & Van Teijlingen, E. R. (2008). A systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 1. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-4

- Pronyk, P. M., Kim, J. C., Abramsky, T., Phetla, G., Hargreaves, J. R., Morison, L. A., … Porter, J. D. (2008). A combined microfinance and training intervention can reduce HIV risk behaviour in young female participants. Aids, 22(13), 1659–1665. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328307a040

- Robert, R. M. J. (2003). Poverty and sexual risk behaviour among young people in Bamenda, Cameroon.

- Rosenstock, I. M. (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs, 2, 328–335. doi:10.1177/109019817400200403

- Roth, J., Satya, K. P., & Bunch, E. (2001). Barriers to condom use: Results from a study in Mumbai (Bombay), India. AIDS Education and Prevention, 13(1), 65–77.

- Sayles, J. N., Pettifor, A., Wong, M. D., MacPhail, C., Lee, S. J., Hendriksen, E., … Coates, T. (2006). Factors associated with self-efficacy for condom use and sexual negotiation among South African youth. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 43(2), 226. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000230527.17459.5c

- Smith, A. D., Tapsoba, P., Peshu, N., Sanders, E. J., & Jaffe, H. W. (2009). Men who have sex with men and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet, 374(9687), 416–422. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61118-1

- Smith, E. A., Palen, L. A., Caldwell, L. L., Flisher, A. J., Graham, J. W., Mathews, C., … Vergnani, T. (2008). Substance use and sexual risk prevention in Cape Town, South Africa: An evaluation of the HealthWise program. Prevention Science, 9(4), 311–321. doi:10.1007/s11121-008-0103-z

- Soskolne, V., & Maayan, S. (1998). HIV knowledge, beliefs and sexual behavior of male heterosexual drug users and non-drug users attending an HIV testing clinic in Israel. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 35(4), 307.

- Speizer, I. S., Magnani, R. J., & Colvin, C. E. (2003). The effectiveness of adolescent reproductive health interventions in developing countries: A review of the evidence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(5), 324–348.

- St. Lawrence, J. S., Chapdelaine, A. P., Devieux, J. G., O’Bannon, R. E., III, Brasfield, T. L., & Eldridge, G. D. (1999). Measuring perceived barriers to condom use: Psychometric evaluation of the condom barriers scale. Assessment, 6(4), 391–404. doi:10.1177/107319119900600409

- Sunmola, A. M. (2005, Feb). Sexual practices, barriers to condom use and its consistent use among long distance truck drivers in Nigeria. AIDS Care, 17(2), 208–221. doi:10.1080/09540120512331325699

- Thurman, T. R., Kidman, R., Carton, T. W., & Chiroro, P., Africa, S. (2016). Psychological and behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk: Evidence from a randomized control trial among orphaned and vulnerable adolescents in. AIDS Care, 28(sup1), 8–15. doi:10.1080/09540121.2016.1146213

- Versteeg, M., & Montagu, M. (2008). Condom use as part of the wider HIV prevention strategy: Experiences from communities in the North West Province. South Africa. Sahara-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 5(2), 83–93.

- Visser, M. J. (2007). HIV/AIDS prevention through peer education and support in secondary schools in South Africa. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 4(3), 678–694. doi:10.1080/17290376.2007.9724891

- Volk, J. E., & Koopman, C. (2001). Factors associated with condom use in Kenya: A test of the health belief model. AIDS Education and Prevention, 13, 495–508.

- Wariki, W. M., Ota, E., Mori, R., Koyanagi, A., Hori, N., & Shibuya, K. (2012). Behavioral interventions to reduce the transmission of HIV infection among sex workers and their clients in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database of System Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005272.pub3

- Weller, S. C., & Davis-Beaty, K. (2002). Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003255