Abstract

Flourishing has been an important topic of research prompting interest in psychometric assessment. However, the need for human emotions and functioning to be measured at a population level has resulted in different conceptual frameworks of flourishing. Eminent psychologists recognise the importance of both hedonic and eudaimonic approaches, which has contributed to an integrated well-being conceptualisation encompassed in the term “flourishing”. The aim of the systematic review is to identify and synthesise the available literature on adolescent flourishing. Based on a systematic search of the literature, 11 publications were included with study samples spanning across adolescents aged 13 to 19 years old. The data were synthesised using textual narrative synthesis. The findings of the studies revealed that there is limited empirical work on adolescent flourishing. Further, no single definition or conceptualisation of flourishing emerged from the literature. Methodologically, the studies included were predominantly quantitative with one mixed-methods study. Finally, only one study used a scale specifically adapted to measure adolescent flourishing. Future empirical research using qualitative techniques to explore and broaden our understanding of adolescents flourishing is needed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

While research in the hedonic tradition, focusing on children and adolescents’ subjective well-being, is well-established, less attention has been placed on the flourishing of children and adolescents. In particular, there is a lack of literature exploring various psychosocial and contextual factors that could impact on adolescent flourishing. Given the relation between mental health, protective factors, and objective indicators of success such as academic confidence, social support, physical health, resiliency, and school grades, it is crucial to understand the manner in which adolescent flourishing can be enhanced. The overall aim of this article is to conduct a systematic review to explore empirical research on adolescent flourishing.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Achieving optimal psychological well-being has been an important pursuit regarding human life. Although psychological research in the past has focused primarily on psychopathology, in recent years, the emergence of positive psychology has enabled research in areas such as happiness and well-being (Henderson & Knight, Citation2012). Within positive psychology, happiness and well-being are conceptualised as outcomes of a pleasant life and have received substantial theorisation and empirical exploration. It is the pursuit of positive emotions regarding the individual’s past, present, and future, while using their strengths and virtues to obtain satisfaction for a meaningful life (Seligman, Citation2003).

Table 1. Data extraction

From the literature on well-being the emergence of two distinct philosophical traditions is evident over the last three decades, namely hedonia and eudaimonia. Vittersø’s (Citation2004) broad definition of eudaimonia includes openness to experience as an aspect of positive psychological functioning, along with preference for complexity, curiosity, engagement/flow, personal growth, competence, meaning/purpose in life and self-actualisation (Vittersø, Citation2004); while hedonia refers to whether activities are experienced as being pleasant or associated with feelings of happiness (Vittersø et al., Citation2004). Flourishers are individuals who experience high levels of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., Citation2015). These distinctions between hedonic and eudaimonic traditions have been contested in recent years (Henderson & Knight, Citation2012). Despite the contention, scholars acknowledge the importance of both hedonic and eudaimonic approaches, which has contributed to an integrated well-being conceptualisation encompassed in the term flourishing (Huppert & So, Citation2009; Henderson & Knight, Citation2012). Flourishing has been an important topic of research prompting interest in psychometric assessment. However, the need for human affect and functioning to be measured at a population level has resulted in different conceptual frameworks of flourishing (Hone, Jarden, Scofield, & Duncan, Citation2014). The first contemporary use of flourishing was by Corey Keyes (Citation2002). Keyes (Citation2002) categorised individuals who flourish as being free of mental disorders, moderately mentally healthy, and not languishing. Huppert and So (Citation2009) further developed this definition and conceptualised a framework of flourishing, and developed the European Social Survey. Huppert and So (Citation2009) conceptualised flourishing as the experience of “life going well”. It is a combination of feeling good and functioning effectively, and is synonymous with a high level of mental well-being.

A number of theorists have also used the concept of “psychological well-being” (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001; Ryff, Citation1989) interchangeably with the concept of flourishing. The former is founded on the idea of universal human needs and optimal functioning (Diener et al., Citation2010). Owing to this, in the development of the Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., Citation2010), flourishing was evaluated in terms of emotional well-being but did not include the aspect of positive functioning. The most recent operationalisation of flourishing is the “PERMA-Profiler” which considers positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meanings and accomplishments (Seligman, Citation2011). Along with several well-being theories which have been developed in recent years, a number of measures have been developed to assess an individual’s psychological flourishing and affect (Diener et al., Citation2010). Internationally, governments are increasingly recognising the significance of measuring flourishing as an indicator of progress (Huppert & So, Citation2009). The identification of the characteristics of individuals, groups, and populations that contribute to high levels of flourishing can provide the basis for health promoters and policymakers to increase people’s ability to flourish (Huppert & So, Citation2009).

The advancement of flourishing is evident in social policy and legislation, reflected in international treaties such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (United Nations General Assembly, Citation1989). Among the key guiding principles of the UNCRC that advances children and adolescents’ flourishing are the “best interest of the child” and the rights and protection of each child. The UNCRC adopted the notion of adolescents as socially active agents in delivering new solutions to problems confronting them, and as a result, are consulted in the design and implementation of new solutions (United Nations General Assembly, Citation1989).

Adolescent well-being was initially conceived at both the national and international levels as “what follows from objective realities” such as rates of mortality, malnutrition, immunization, disease, etc. (Casas, Citation2011). Many governments have initiated numerous programmes by evaluating objective indicators such as poverty, access to primary health care services, safety, and education, with less focus on the subjective elements of adolescents’ well-being.

Understanding how to increase the flourishing of adolescents is therefore important given the empirical link between mental health, protective factors, and objective indicators of success (such as academic confidence, social support, physical health, resiliency, school grades) (Casas, Citation2011).

1.1. Rationale for the review

Research in the hedonic tradition focusing on children and adolescents subjective well-being (SWB) is well-established, however, less attention has been placed on the eudaimonic dimension of children and adolescents’ well-being. While recent literature with adults has explored the significance in incorporating both hedonic and eudaimonic components of well-being, encompassed in the concept of flourishing, there is a notable absence on empirical research on adolescent flourishing.

It is crucial to understand the manner in which adolescent flourishing can be enhanced. It is evident in the work of van Schalkwyk and Wissing (Citation2010) that adolescents’ own evaluation of their flourishing presents a valuable source of information for political decision-making and informing social policy.

A further motivation for the current review, emerging from the literature on hedonic well-being, is the concept of the “subjective well-being decreasing-with-age tendency”. While Petito and Cummins (Citation2000) were among the first to identify the tendency, more recent cross-cultural research conducted by Casas, Tiliouine, and Figuer (Citation2014) found children’s SWB to decrease between the ages of 13 to 20 years. These results align to those of other studies (see Goswami, Citation2013; Goldbeck, Schmitz, Nesier, Herschbach, & Henrich, Citation2007; Park, Citation2005). It is noteworthy that the period in which most dissatisfaction and lower SWB occurred was between the ages of 15–16 years (Goldbeck et al., Citation2007). A significant contribution to the debate is evident in a longitudinal study conducted by González-Carrasco et al. (Citation2016). They found that the SWB levels decreased from the ages of 11 to 12 years. While the evidence shows a “subjective well-being decreasing-with-age tendency” from the age of 12 into adolescence there is less consensus as to the mechanisms accounting for this phenomenon (Casas, Citation2016). While it can be attributed to “normal” developmental processes related to the physical, neurodevelopmental, psychological and social changes associated with the period of adolescence (World Health Organisation, Citation2019), described as a period of heightened turmoil and stress (Casey et al., Citation2010); there may be an underlying cultural influence. Given that lower levels of SWB in adolescence is associated with poor psychosocial outcomes it is imperative that the research provide more cogent theoretical, conceptual and empirical explanations. While some authors argue for an increased focus on the role of affect (Casas, Citation2016), others advocate for a stronger consideration of psychological (eudaimonic) well-being (see Fave, Brdar, Freire, Vella-Brodrick, & Wissing, Citation2011). The key point made by Fave et al. (Citation2011) is that research into child and adolescent well-being should include considerations of both the hedonic and eudaimonic traditions. This approach has however not been forthcoming in the literature with studies focused on either one or other tradition. Furthermore, those that have adopted this approach are constrained by the challenges related to how the concept has been conceptualised and operationalised (in the adult literature).

A systematic review provides a methodologically rigorous opportunity to evaluate the state of research on adolescent flourishing. The current review is the first to provide a systematic account of the empirical research on adolescent flourishing. In particular, the review focuses on synthesising how the research studies were conceptualised, the sampling strategy used and participants, the research context, data collection methods, theoretical grounding, and key findings.

1.2. Aim of the study

The overall aim of the study is to systematically review the empirical research on adolescent flourishing. The study further aimed to explore how adolescent flourishing has been conceptualised, and the advancements that have been made in terms of research on adolescent flourishing.

2. Method

2.1. Review question

What empirical literature exists on adolescents’ flourishing?

2.2. Research design

The current study uses a systematic review design. The aim of a systematic review is to map the key concepts and provide complete and exhaustive summaries of available literature underpinning a research area, main sources and types of evidence available (Khan, Kunz, Kleijen, & Antes, Citation2003).

2.3. Article search

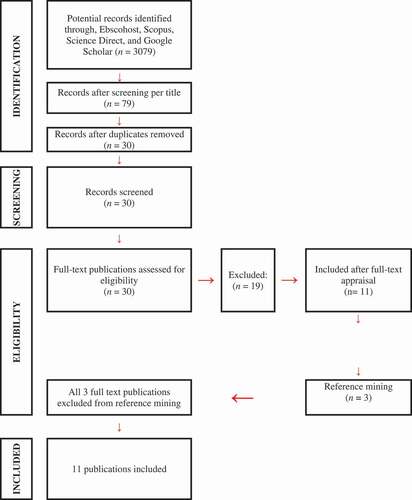

A comprehensive search was conducted between April and October 2018 using the following databases: ScienceDirect; EbscoHost (CINAHL, PsycArticles, Medline, SocIndex and Academic Search Complete); Scopus; and Google Scholar. The searches were conducted using the library resources at the University of the Western Cape. The time frame for the review were articles published between 2008 and 2018. The keywords used in the review included: “flourishing”, “flourishing and adolescents”, “flourishing and young people”, and “flourishing and children”. Each stage of the search process namely, title search, abstract search, and full-text appraisal was conducted by a three-member review team, to limit bias for publication inclusion. Reviewers searched independently and results were recorded in a title/abstract extraction sheet for discussion. First and second-stage screening of titles and abstracts were based on their relevancy to the research question, their study design, and population. Based on the initial screening, selected full-text publications were obtained and the same systematic process was conducted to determine eligibility. Due to the limited number of eligible publications at the final stage of review, reference mining was used to identify additional publications. This search yielded three additional publications for final inclusion. Finally, eligibility of publications for inclusion in the systematic review were appraised by each reviewer individually using a standardised appraisal tool. Results were then compared and consensus reached for final inclusion in the systematic review.

2.4. Inclusion criteria

For the purposes of this systematic review, the criteria for final inclusion in the study were as follows: (i) publications in the English language only, (ii) publication dates ranging from 2008 to 2018, (iii) studies that reported on adolescents flourishing (ages 12 to 19 years old), (iv) peer-reviewed publications, (v) and empirical studies.

2.5. Exclusion criteria

Publications were excluded on the basis of the following: (i) publications focussed on adults, (ii) and studies that did not fall within the stipulated time frame.

2.6. Quality assessment

Daudt, van Mossel, and Scott (Citation2013) suggests that quality assessment is a necessary component and should be performed using validated tools. The selection of studies included in the review was assessed by utilising an adapted version of the Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Studies and the Evaluation Tool for Quantitative Research Studies (Long & Godfrey, Citation2004). The assessment was crucial in evaluating the quality and methodological rigour of the included publications. These appraisal tools were developed to assist researchers with the critical appraisal of research studies as a template consisting of key questions to analysing the core areas of each publication (Long, Godfrey, Randall, Brettle, & Grant, Citation2002). Given that many of the sections overlapped, the aspects specific to each methodological framework were removed. The remaining review areas, which were common to both tools and applicable to both qualitative and quantitative studies were maintained, namely: study overview, study setting, sample, and ethics, and policy and practice implications. For each publication obtained during the search process, the quality appraisal tool was applied to assess the quality of the publication (Long et al., Citation2002).

2.7. Data extraction

The data extraction table was developed to provide an overview of the studies and highlight key areas. It included the following headings: authors; aim; sample size; design; and key findings (see Table ).

2.8. Data synthesis

Data were synthesised using the textual narrative synthesis approach as proposed by Lucas, Baird, Arai, Law, and Roberts (Citation2007). When comparing textual narrative synthesis with thematic synthesis, Lucas et al. (Citation2007) found that the former enables the identification of heterogeneity between studies, as well as concerns involving quality appraisal. This synthesis technique enables the researcher to organise studies into homogeneous groups. Using this synthesis method, the studies included in the review were grouped into five main categories: conceptualisation; context; content; method; and theory.

3. Results

3.1. Article procedure

A three-step strategy was used in the review. The initial search yielded a total of 3079 potential publications across all databases (EbsoHost = 263; ScienceDirect = 921; Scopus = 245; Google Scholar = 1650). During the title search, all 3079 publications were screened by the members of the team. A total of 79 publications were included for abstract appraisal. Once all duplicates were removed, 30 publications were included for full-text appraisal, thereafter 11 met the criteria for final inclusion in the study. Based on reference mining, three potential publications were identified based on a title search, however, all three publications were excluded. Therefore, a total of 11 publications were included in the review. A flowchart of the process is presented in Figure .

3.2. Scope and focus of research

Using textual narrative synthesis (Lucas et al., Citation2007), the following key categories were identified: 1. Conceptualisation of adolescent flourishing; 2. Context; 3. Content (foci of the studies); 4. Method; and 5. Theory. These categories are discussed in detail in the following section.

3.3. General descriptions of the studies reviewed

The descriptions that follow are based on the following publications: i) Kwong and Hayes (Citation2017), ii) Reschly, Huebner, Appleton, and Antarramanion (Citation2008), iii) Kern, Benson, Steinberg, Steinberg, and Abdulaziz (Citation2016), iv) Huppert and So (Citation2009), v) Venning, Wilson, Kettler, and Eliott (Citation2012), vi) Orkibi, Hamama, Gavriel-Fried, and Ronen (Citation2018), vii) van Schalkwyk and Wissing (Citation2010), viii) Stough, Nabors, Merianos, and Zhang (Citation2015), ix) Skrzypiec, Askel-Williams, Slee, and Rudzinski (Citation2016), xi) Singh, Junnarka, and Jaswal (Citation2016) and xii) Lippman et al. (Citation2011). One of the studies were conducted in South Africa, one in Europe, five in the United States of America, three from Australia, and one study from Israel. All the studies focused on predictors, correlates, indicators, or key aspects of flourishing with adolescents.

3.3.1. Conceptualisation of flourishing

This category explored how adolescent flourishing has been conceptualised in the 11 publications included in the review. A key finding in this category was that well-being encompasses positive mental and physical health. Lippman et al. (Citation2011) state that if we want adolescents to flourish we need to have a clear consensus on the definition of flourishing. They conceptualise flourishing as thriving and focusing on positive aspects of well-being. For Lippman et al. (Citation2011), good measurement of flourishing contributes to strategies that increase our understanding of the value of investing in efforts to achieve positive outcomes.

Based on the definition of Lippman et al. (Citation2011), Kwong and Hayes (Citation2017) conceptualised flourishing as thriving and as a “building block” of positive well-being. They identified various aspects of flourishing within the period of infancy and childhood which include: healthy attachment relationships; curiosity and interest in learning; the ability to regain equilibrium after an upset; and expressions of joy or happiness (Kwong & Hayes, Citation2017). For adolescents, the aspects of flourishing include: personal attitudes or beliefs; positive interpersonal relationships; and task-related characteristics, such as diligence and initiative (Kwong & Hayes, Citation2017). It is important to note that flourishing, as an outcome measure, may serve as a possible mediator between adverse family experiences and health issues in adulthood (Kwong & Hayes, Citation2017).

Similarly, both Huppert and So (Citation2009), and Kern et al. (Citation2016) defined flourishing as the experience of life going well, feeling good, and functioning effectively. Orkibi et al. (Citation2018) conceptualise flourishing as a skill of self-control that is pertinent for fostering personal and interpersonal growth. They also asserted that adolescents’ self-control skills is associated with their positivity ratio directly and indirectly, through perceived sense of social support from parents as well as classmates. For Stough et al. (Citation2015) flourishing represents positive mental health and living within an optimal range of human functioning.

3.3.2. Context

The studies reviewed were conducted in various contexts. Most of the studies were conducted in developed contexts, and predominantly within middle and high-income neighbourhoods. The study conducted in Europe (see Huppert & So, Citation2009) was based in three regions; within each region broad similarities in terms of their culture and governance were shared. The three regions were: Northern Europe (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden) Western Europe (Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom), and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Estonia, Russian Federation, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine). The South African study (van Schalkwyk & Wissing, Citation2010) was conducted in three secondary schools with varying socio-economic environments. Studies within the USA (Kwong & Hayes, Citation2017; Reschly et al., Citation2008; Stough et al., Citation2015) were conducted in urban areas, and in Australia, schools from urban and rural areas were included (Skrzypiec et al., Citation2016).

3.3.3. Content (focus of the study)

The studies reviewed had varying foci. Kwong and Hayes (Citation2017) focused specifically on adverse family experiences and the effect it has on children and adolescents flourishing. A key finding of the study was that adverse family experiences have negative social and behavioural developmental consequences on children and adolescents. It was also found that children, between the ages of 6 and 17 years, experiencing adverse family circumstances have lower levels of flourishing. This is important in understanding how this relationship can help guide public health efforts and inform policy. Kwong and Hayes (Citation2017) state that flourishing encompassed three areas: firstly, the capability to remain in control when challenged; secondly, the interest in learning new things; and thirdly, the ability to follow through with plans. These three areas are essential components of children’s well-being and the inability to successfully demonstrate these qualities may have consequences perpetuating into adolescence and adulthood. For example, a lack of interest in learning and inability to follow through with plans may hamper a child’s ability to succeed academically, ultimately lead to decreased economic productivity which is associated with lower levels educational attainment (Kwong & Hayes, Citation2017). They also state that adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse, has a negative impact on the well-being of adolescents. Lippman et al. (Citation2011) introduced the Flourishing Children Project which focused on the development of positive indicators for measuring adolescent flourishing. Lippman et al. (Citation2011) suggest that providing a statistical overview on problem behaviours of adolescents can assist governments, schools and organisations to develop interventions to address and enhance flourishing. In doing so, Lippman et al. (Citation2011) state that this can further assist policy-makers and organisations identify and develop strengths that lead to positive outcomes for adolescents.

Reschly et al. (Citation2008) explored how experiencing positive emotions more frequently increases flourishing in adolescents. They found that the frequent experience of positive emotions in school, relates to broadened cognitive (i.e., problem solving) and behavioural (i.e., social support seeking) coping strategies. Additionally, the association between positive emotions and several student engagement variables was partially mediated by coping strategies. Kern et al. (Citation2016) developed the Engagement, Perseverance, Optimism, Connectedness, and Happiness (EPOCH) measure of adolescent well-being. They indicate that key EPOCH aspects may foster well-being and positive outcomes in adulthood. The study by Huppert and So (Citation2009) focused on a conceptual framework which associates high well-being with positive mental health. In a study conducted by Venning et al. (Citation2012), the Complete State Model of Mental Health was used to describe the prevalence of “flourishing, languishing, struggling, and floundering” in life with a sample of Australian adolescents.

Orkibi et al. (Citation2018) tested a model positing that adolescents’ self-control skills is associated with their positivity levels depending on their perceived social support from parents and classmates. They found that adolescents who displayed self-control skills had an increased likelihood of flourishing. Further, increased social support was found to influence their positivity ratio, ultimately leading to flourishing. Orkibi et al. (Citation2018) also indicated that social support plays a pivotal role during dramatic life changes such as adolescence. The findings also evince that social belonging is also an important aspect of adolescent’s well-being. The experience of social rejection, social isolation and perceived lack of social support were also found to contribute to loneliness (Orkibi et al., Citation2018). They state that even though adolescents face many life obstacles (i.e. demands, changes, and distress), the need or desire to cope throughout is pertinent. Orkibi et al. (Citation2018) posit that given the rapid and intense changes of the period of adolescence and the empirical evidence indicating that positive emotions fosters well-being, it is of utmost importance to investigate how adolescents’ personal and interpersonal resources may facilitate their well-being.

Using a mixed-methods study, van Schalkwyk and Wissing (Citation2010) aimed to explore the psychosocial well-being of adolescents using interviews and surveys. They found that adolescents’ understanding of flourishing included the following themes: purposeful living and meaning; positive relationships; role-models; self-confidence and self-regard; constructive life-style; constructive coping; and positive emotions. Conversely, adolescents’ understandings of languishing included broken relationships, unsupportive family, conflict, and negative relations. The study also revealed that 58% of adolescents were not flourishing. This finding coincides with that of Keyes (Citation2002) which suggests that flourishing decreases in adulthood. Further, this echoes the assertion by Huppert and So (Citation2009) that flourishing is more than merely the absence of mental disorders. van Schalkwyk and Wissing (Citation2010) identified that themes taken from qualitative data, corresponded to themes found in quantitative data such as: relationships, ego-resiliency and autonomy, zest for life and the importance of positive affect. Important to note is that adolescents who are continually exposed to negative conditions (poverty, crime, high-risk behaviour) may result in higher levels of languishing (van Schalkwyk & Wissing, Citation2010).

Stough et al. (Citation2015) conducted a study to explore whether adolescents with epilepsy flourish less than adolescents without epilepsy. They posit that support groups increase the flourishing of adolescents. On the other hand, the study indicated that adolescents who received positive support from parents (i.e. parents displayed less anger/harsh parenting) displayed higher flourishing outcomes (Stough et al., Citation2015). For adolescents who have epilepsy, Stough et al. (Citation2015) posit that in providing patient care, support groups are crucial in the flourishing of these adolescents.

Skrzypiec et al. (Citation2016) administered a questionnaire assessing social, emotional, and psychological well-being among a sample of adolescents with special educational needs. A key finding from the study indicates that the design and implementation of support structures to improve the well-being and school satisfaction of students with Self-Identified Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) requires further attention. Singh et al. (Citation2016) conducted a study validating the Flourishing Scale and the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience with a sample of adolescents in India. This was the only identified study that used and adapted a single measure to assess adolescent flourishing. The scales were also found to have good psychometric properties in India. Both (Flourishing Scale and SPANE) scales showed single-factor structure of the FS and two-factor structure of SPANE, high internal consistency and satisfactory convergent validity.

Venning, Wilson, Kettler, and Elliot (Citation2012) conducted a study with a sample of adolescents aged 13–17 years. The results of the study found that 42% of the adolescents were flourishing in life and 5% were languishing. The adolescents indicated that health-risk behaviour led to languishing. The results also indicate that the majority of adolescents who were languishing engaged in risky behaviour such as smoking, drinking, and negative relationships (Venning et al., Citation2012). Venning et al. (Citation2012) posit that personal attitudes or beliefs, positive interpersonal relationships, and characteristics such as diligence are all associated with flourishing. They state that adolescents who are flourishing in life are free from mental illness, and display high levels of emotional well-being (hedonia) and high levels of positive functioning (psychological and social well-being).

3.3.4. Method

Most of the studies reviewed employed quantitative methods and one study utilised a mixed-methods approach. In terms of instrumentation, Reschly et al. (Citation2008) used the Positive and Negative Affect Scale-Children, Self-Report Coping Scale, and the Student engagement Instrument, with a sample of 293 students from south-eastern USA. They made use of correlation and regression analysis to analyse the findings of the study. The study conducted by Lippman et al. (Citation2011) made use of a mixed-methods approach. The qualitative study included a sample of both adolescents (n = 68) and parents (n = 23) from 15 cities across the USA. The data were analysed by means of narrative synthesis and the quantitative component of the study used descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis.

Orkibi et al. (Citation2018) conducted a study with 807 adolescents. The scales used in the study included: the Positive and Negative Affect Scale-Children; Self-control Scale; and the Child and Adolescent Support Scale. They made use of structural equation modelling and confirmatory factor analysis. Stough et al. (Citation2015) conducted a study with 23 799 adolescents, using a self-developed 3-item scale on flourishing employing a telephone survey. They made use of a t-test and regression analysis to analyse the study findings. The study conducted by Skrzypiec et al. (Citation2016) with a sample of 1983 adolescents and made use of the Social, Emotional and Psychological Well-Being Scale, Global Self-Concept Scale, and the Connor- Davidson Resilience Scale. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to analyse the data.

van Schalkwyk and Wissing (Citation2010) conducted a survey with a sample of 665 adolescents. The scales used in the survey included: the Mental Health Continuum- Short Form (MHC-SF); Ego Resiliency Scale (ERS); Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS); and the Affectometer 2- Short Version (AFM). The study by Venning et al. (Citation2012) utilised a survey design with a sample of 3913 adolescents aged 13–17 years old. The following scales were included in the survey: Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS); Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS); and Social Well-Being Scale (SWBS). To analyse the data a chi-square and sub-analysis was conducted.

Kwong and Hayes (Citation2017) used an instrument that included self-developed positive health items and flourishing items. They conducted a telephone survey with adolescents 18 years and above. They made use of a sub-analysis to analyse the data. Huppert and So (Citation2009) conducted the European Social Survey with a sample of 43,000 people aged 15 and above. They analysed the data by means of correlation, exploratory factor analysis, and structural equation modelling. Kern et al. (Citation2016) conducted a study with 4500 adolescents by using the EPOCH measure of well-being. Confirmatory factor analysis and correlation was used to analyse the data. Singh et al. (Citation2016) conducted a scale validation study with a sample of 4200 adolescents. The data were analysed using exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis to assess the validity of the scales used.

3.3.5. Theory

It was found that only three of the studies reviewed were conceptualised using a theoretical framework. The study conducted by Reschly et al. (Citation2008) used Fredrickson’s Broaden and Build theory. They postulate that the experience of frequent positive emotions serves as a catalyst of well-being. Orkibi et al. (Citation2018) conceptualised the study by drawing on Bowlby’s Theory of Attachment (Citation1988). The theory claims that positive emotions expand awareness, cognition, and behavioural repertoires which ultimately lead to well-being. While Lippman et al. (Citation2011) used Krosnick’s Satisficing Theory, in relation to the development of survey questions, they did not conceptualise flourishing within a particular theoretical framework. The rest of the studies did not clearly indicate a theoretical framework. It is important to note that none of the reviewed publications located their studies within contemporary theories of well-being. Further refinement and application of theoretical frameworks when conducting research on adolescent flourishing should be advanced.

3.4. Discussion and conclusion

The aim of the study was to provide a systematic review of literature from 2008 to 2018, to explore how adolescent flourishing has been conceptualised, and the advancements that have been made in terms of research on adolescent flourishing.

A summary of the findings reveal important information in a number of areas. Adolescents experience psychological well-being when living life with a purpose and having positive relationships (van Schalkwyk & Wissing, Citation2010), and adolescents who displayed self-control skills had an increased likelihood of flourishing (Orkibi et al., Citation2018). It also emerged from the literature that engagement, perseverance, optimism, connectedness and happiness were aspects found to foster flourishing and positive outcomes in adulthood (Kern et al., Citation2016). It was evident that positive emotions and outcomes appear to be influenced by personal and environmental resources (Reschly et al., Citation2008). Notably, adolescents who are continually exposed to negative conditions such as poverty, crime, and engage in high-risk behaviour, contributes to a sense of languishing (van Schalkwyk & Wissing, Citation2010). The results further indicate that the majority of adolescents who were languishing were likely to engage in risky behaviour (Venning et al., Citation2012). It was found that adverse family and childhood experiences, such as abuse, has a negative impact on adolescents’ well-being and their ability to flourish (Kwong & Hayes, Citation2017). However, despite the relation between adverse family experiences and difficulties in positive development, some children were still able to flourish owing to various support structures (Kwong & Hayes, Citation2017; Stough et al., Citation2015).

One of the key findings of the review was that adolescent flourishing is conceptualised in various ways in the literature. While in the past flourishing was conceptualised and explored in terms of one philosophical component (hedonia or eudaimonia) (Huppert & So, Citation2009), more recently, research indicates that the conceptualisation of flourishing should include both components as is evident in the definition put forward by Huppert and So (Citation2009). They define flourishing as the experience of life going well, functioning effectively, and having a high level of mental well-being. They used robust and comprehensive ways to develop an operational definition of flourishing, such as the use of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) classification systems (see Huppert & So, Citation2009). Further, these authors also utilised existing measures as indicators to identify the “features of flourishing”. Many of the studies included in the review have indicated how flourishing has been conceptualised. However, with the exception of the study by Huppert and So (Citation2009) there was not a clear indication of the hedonic and eudaimonic contribution towards the conceptualisation. The construct of flourishing was often used as a generic term to refer to either overall positive well-being or used as a proxy for eudaimonic well-being. Often there was no clear indication of the hedonic component and its contribution to how flourishing has been conceptualised. It appears that the construct is often vaguely conceptualised which has implications for how it is operationalised, and ultimately how it is measured. This has resulted in the use of measuring instruments which are not fully aligned to the construct, and often only measures one component of flourishing. The lack of valid measuring instruments to assess adolescent flourishing is further evidence of this contention. Further to that, none of the studies highlighted the importance of conceptualising flourishing in terms of adolescents’ own perceptions and understandings.

Methodologically, the reviewed studies used quantitative and mixed-methods frameworks. The focus and scope of the quantitative studies in terms of adolescent flourishing were clearly stipulated. The review of the literature revealed that there is no standardised and validated scale to assess adolescent flourishing, which is in line with the contention made by Kwong and Hayes (Citation2017). This resonates with a previously mentioned point in relation to the lack of conceptual clarity and operationalisation of the construct. Given this, it was found that many studies employed the use of several measurement instruments to assess adolescent flourishing (see Huppert & So, Citation2009; Kwong & Hayes, Citation2017; Lippman et al., Citation2011; Orkibi et al., Citation2018; Reschly et al., Citation2008; Singh et al., Citation2016). However, there was one study that adapted Diener’s Flourishing Scale for use with adolescents in India (Singh et al., Citation2016) Lippman et al. (Citation2011) suggest that providing a statistical overview on problem behaviours of adolescents can assist governments, schools and organisations to develop interventions to address and enhance flourishing. Further adaptation of existing flourishing measures for use with adolescents or the development of new flourishing measures is recommended.

Considering global advocacy for children’s rights in countries that have adopted the UNCRC (Citation1989), there is a need for more studies to include methods which enable adolescents to express their own understanding and perceptions of flourishing (Lippman et al., Citation2011). Given that the studies in this review were predominantly quantitative, more studies using qualitative techniques to explore adolescent flourishing is necessary. Qualitative research can address questions such as: How do adolescents make sense of flourishing? What does flourishing mean to adolescents based on their own perspective? What do adolescents need to flourish? And how do social and contextual realities influence adolescents flourishing? These are critical questions that require further exploration. Moreover, as the majority of the studies were conducted in developed contexts it highlights the need for future research in developing contexts. Further to that, cross-cultural studies involving adolescents from diverse socio-economic contexts are recommended. To that end, the development and adaptation of instruments to measure flourishing are needed, which would subsequently require validation studies across diverse contexts. Throughout the review process it is noteworthy that empirical studies on adolescent flourishing is still in its infancy with most of the reviewed studies using small samples. Moving forward, it is crucial for large-scale, population-based studies to be conducted which would allow for a more advanced interrogation of the correlates and determinants of adolescent flourishing, taking specific note of the adolescents specific social context. Finally, there is an increasing need to advance empirical studies to look beyond adolescent life satisfaction and well-being, to include both hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions, which would allow for more holistic approach and comprehensive understanding of the quality of life of children and adolescents (Adams et al., Citation2019; Henderson & Knight, Citation2012). Here it would be important to explore the nature of the relation between the hedonic and eudaimonic components and how it can be integrated into a meaningful framework which could address pragmatic concerns in relation to flourishing (Henderson & Knight, Citation2012).

In conclusion, it is important to note that there were a limited number of evidence-based studies conducted on adolescent flourishing and there is a need for further empirical research, both qualitative and quantitative. Given the concerns raised in relation to the conceptualisation of the construct of flourishing, it is recommended that further engagement at a theoretical level be advanced. To this end, further interrogation of Seligman (Citation2011) theory of flourishing may prove a useful point of departure.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Heidi Witten

Heidi Witten is a PhD candidate at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), Cape Town, South Africa. She obtained her Honours (Psychology) and M.A. (Research Psychology) degree at the UWC. Her research interests include children and adolescent’s well-being and flourishing.

References

- Adams, S., Savahl, S., Florence, M., Jackson, K., Manuel, D., Mpilo, M., & Isobell, D. (2019). Training emerging researchers in constrained contexts: Conducting quality of life research with children in South Africa. In G. Tonon (Ed.), Teaching quality of life in different domains (pp. 1–32). Dortrecht: Springer.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664–16. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

- Casas, F. (2011). Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indicators Research, 555–575. doi:10.1007/s12187-010-9093-z

- Casas, F. (2016). The decreasing-with-age subjective wellbeing trend: New data and new challenges for research and education. Conference Paper for the Global Summit on Childhood, Costa Rica.

- Casas, F., Tiliouine, H., & Figuer, C. (2014). The subjective well-being of adolescents from two different cultures: Applying three versions of the PWI in Algeria and Spain. Social Indicators Research, 115(2), 637–651. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0229-z

- Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., Levita, L., Libby, V., Pattwell, S. S., Ruberry, E. J., … Somerville, L. H. (2010). The storm and stress of adolescence: Insights from human imaging and mouse genetics. Developmental Psychobiology, 52(3), 225–235. doi:10.1002/dev.20447

- Daudt, H. M. L., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(48), 1–9. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-1

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Pietro, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., … Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

- Fave, D., Brdar, I., Freire, T., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Wissing, M. P. (2011). The eudaimonic and hedonic components of happiness: Qualitative and quantitative findings. Social Indicators Research, 100, 185–207. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9632-5

- Goldbeck, L., Schmitz, T. G., Nesier, T., Herschbach, P., & Henrich, G. (2007). Life satisfaction decreases during adolescence. Quality of Life Research, 16, 969–979. doi:10.1007/s11136-007-9205-5

- González-Carrasco, M., Casas, F., Viñas, F., Malo, S., Gras, M. E., & Bedin, L. (2016). What leads subjective well-being to change through adolescence? An exploration of potential factors. Child Indicators Research, Advance on-line publication. doi:10.1007/s12187-015-9359-6

- Goswami, H. (2013). Children’s subjective well-being: Socio-demographic characteristics and personality. Child Indicator Research, 7(1), 119–140. doi:10.1007/s12187-013-9205-7

- Henderson, L. W., & Knight, T. (2012). Integrating the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives to more comprehensively understand well-being and pathways to well-being. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 196–221. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.3

- Hone, L. C., Jarden, A., Schofield, G. M., & Duncan, S. (2014). Measuring flourishing: The impact of operational definitions on the prevalence of high levels of wellbeing. International Journal of Well-being, 4(1), 62–90. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v4i1.4

- Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2009). Flourishing across Europe: A conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110, 837–861. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

- Kern, M. L., Benson, L., Steinberg, E. A., Steinberg, L., & Abdulaziz, K. (2016). The EPOCH measure of adolescent well-being. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), 586–597. doi:10.1037/pas0000201

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207–222. doi:10.2307/3090197

- Khan, K. S., Kunz, R., Kleijen, J., & Antes, G. (2003). Five steps to conducting a systematic review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96(3), 118–121. doi:10.1258/jrsm.96.3.118

- Kwong, T. Y., & Hayes, D. K. (2017). Adverse family experiences and flourishing amongst children ages 6–17 years: 2011/12 National survey of children’s health. Child Abuse and Neglect, 70, 240–246. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.016

- Lippman, L. H., Moore, K. A., Guzman, L., Ryberg, R., McIntosh, H., Ramos, M. F., … Kuhfeld, M. (2011). Flourishing children defining and testing indicators of positive development. London: Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York.

- Long, A. F., & Godfrey, M. (2004). An evaluation tool to assess the quality of qualitative research studies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 7(2), 181–196. doi:10.1080/1364557032000045302

- Long, A. F., Godfrey, M., Randall, T., Brettle, A. J., & Grant, M. J. (2002). Developingevidence based social care policy and practice: Part 3: Feasibility of undertakingsystematic reviews in social care (Project report). Leeds, England: University of Leeds, Nuffield Institute for Health.

- Lucas, P. J., Baird, J., Arai, L., Law, C., & Roberts, H. M. (2007). Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7(4), 1–7. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-4

- Orkibi, H., Hamama, L., Gavriel-Fried, B., & Ronen, T. (2018). Pathways to adolescents’ flourishing: Linking self-control skills and positivity ratio through social support. Youth and Society, 50(1), 3–25. doi:10.1177/0044118X15581171

- Park, N. (2005). Life satisfaction among Korean children and youth. A developmental perspective. School Psychology International, 26(2), 209–223. doi:10.1177/0143034305052914

- Petito, F., & Cummins, R. A. (2000). Quality of life in adolescence: The role of perceived control, parenting style, and social support. Behaviour Change, 17(3), 193–207. doi:10.1375/bech.17.3.196

- Reschly, A. L., Huebner, T. S., Appleton, J. J., & Antarramanion, S. (2008). Engagement as flourishing: The contribution of positive emotions and coping to adolescents’engagement at school and with learning. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 419–431. doi:10.1002/pits.20306

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25–41.

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful aging. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12, 35–55. doi:10.1177/016502548901200102

- Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Pieterse, M. E., Drossaert, C. H. C., Westerhof, G. J., de Graaf, R., Ten Have, M., … Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2015). What factors are associated with flourishing? Results from a large representative national sample. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1–20. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9647-3

- Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. NY: Free Press.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Authentic Happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

- Singh, K., Junnarka, M., & Jaswal, S. (2016). Validating the flourishing scale and the scale of positive and negative experience in India. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 19(8), 943–954. doi:10.1080/13674676.2016.1229289

- Skrzypiec, G., Askel-Williams, H., Slee, P., & Rudzinski, A. (2016). Students with self-identified special educational needs and disabilities (si-SEND): Flourishing orlanguishing! International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 63(1), 7–26. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2015.1111301

- Stough, C. O., Nabors, L., Merianos, A., & Zhang, J. (2015). Short communication: Flourishing among adolescents with epilepsy: Correlates and comparison to peers. Epilespy Research, 117, 10–15.

- United Nations General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3. Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html

- Venning, A., Wilson, A., Kettler, L., & Elliot, J. (2012). Mental health among youth in South Australia: A survey of flourishing, languishing, struggling, and floundering. Australian Psychological Society, 48, 299–310. doi:10.1111/j.1742-9544.2012.00068.x

- Vittersø, J. (2004). Flourishing versus self-actualization: Using the flow-simplex to promote a conceptual, clarification of subjective quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 65, 299–331. doi:10.1023/B:SOCI.0000003910.26194.ef

- van Schalkwyk, I., & Wissing, M. P. (2010). Psychosocial well-being in a group of South African adolescents. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 20(1), 53–60. doi:10.1080/14330237.2010.10820342

- World Health Organisation. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/development/en/