Abstract

Thich Quang Duc was a Buddhist monk protesting in South Vietnam, when his image captivated the world. Malcolm Browne won the World Press Photo of the Year in 1963 photographing Duc committing an act of self-immolation, burning to death. Current research into mindfulness and meditation gives neuroscientists, scientists, and clinicians a glimpse into the physiology, structure and function of the brain of expert meditators such as Duc. A growing body of literature indicates that basic breathing techniques and meditation can alter cortical structures with very little training. Structural and functional MRI has revealed the anterior cingulate and insular cortex are altered in functioning due to meditation and mindfulness practice. Continued research into mindfulness and expert meditators should help us gain a greater understanding into how a monk like Duc was able to commit such a powerful behavioral act, becoming the monk on fire.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The present review examines the scientific literature concerning expert meditators and practitioners of mindfulness. The review highlights and focuses on Thich Quang Duc, an expert practitioner and Buddhist monk from South Vietnam. The image of Duc captivated the world and the self-immolation act of Duc deserves a thorough examination to understand the physiological and neurological processes that enable this behavior to occur. Meditation and mindfulness behaviors empower practitioners to alter the mind, for example by changing an individual’s ability to withstand pain. The manuscript is a synopsis of the scientific literature since the early 1800’s concerning physiology and current structural-functional studies using MRI in meditation and mindfulness. Future research into the brain-behavior sciences of expert meditators like Duc will allow us to gain a greater understanding of the mind.

“All beings are to be redeemed from the illusion which is the fountain of their troubles. None is to be compelled to assume irrationally an alien set of duties or other functions than his own. Spirit is not to be incarcerated perpetually in grotesque and accidental monsters, but to be freed from all fatality and compulsion. The goal is not some more flattering incarnation, but escape from incarnation altogether. Ignorance is to be enlightened, passion calmed, mistaken destiny revoked; only what the inmost being desiderates, only what can really quiet the longings embodied in any particular will, is to occupy the redeemed mind.”

The Life of Reason, by George Santayana (1905), a passage on charity with widespread meanderings and excogitating on Buddhism.

1. Introduction

On June 11th, 2013 we honored the 50th year anniversary of Thich Quang Duc’sFootnote1 self-immolation on 11 June 1963, in Saigon, South Vietnam (Figure ). The venerable act of Duc resulted in Malcolm Browne winning the World Press Photo of the Year in 1963, contributed to his Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1964 (Browne, Citation1968, p. 262; Citation1993, p. 12), and provoked responses from President JFK to re-evaluate the Vietnam Situation (Pyle & Ilnytzky, Citation2012). A video of Duc’s self-immolation can be found online (Youtube, see supplementary Video). Throughout the entire act, Duc displays no movement and makes no sound, simply existing for those moments. The image of Duc has captivated me since I was a child and saw the image on the album of Rage Against the Machine in 1992Footnote2. The self-immolation of Duc deserves a thorough examination to understand the physiological and neurological processes that enable this behavior to occur. As a studying neuroscientist (Manno, Citation2009, Citation2016—my first foray into Indology; Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Manno et al., Citation2018; Dong et al., Citation2018; Lau, Manno, Dong, Chan, & Wu, Citation2018), it is difficult for me to imagine the sensations of being burned to death or how it’s possible to undertake such an act. I know my actions and my responses would be very different from this monk, but why? More importantly, how is the self-immolation behavior/act possible?

Figure 1. The self-immolation of Duc on June 11th, 1963 in Saigon, South Vietnam photographed by Malcolm Browne.

In the present review I hope to weave together Duc’s self-immolation and contemporary neuroscience research to explain how the brain functions during intense meditation. While there have been several reviews on meditation and mindfulness, there has been no review discussing the theoretical foundations of expert meditators (i.e., Duc); furthermore, no history of expert meditation has been published in a peer-reviewed journal.Footnote3 I endeavor to attempt both, dovetailing into the history of meditation and mindfulness in an attempt to explain the behavior of Duc. The first aspect of the article reviews the history of meditation science published in peer-reviewed journals (starting in the early 1800’s) where authors discussed “human hibernation”. This is followed by research in physiology (pulmonary and cardiovascular effects) which occurred from the 1960’s to 1990’s. I then move into contemporary neuroscience research which uses MRI, fMRI, and EEG. Essentially the review is divided into: (1) historical developments of expert meditators (early articles consisting of hostility, derogatory comments, and dubious explanations of meditation), (2) the beginnings of meditative science (corresponding largely to physiology experiments, read Wallace, Citation1970—breathing and heart rates of monks: how did Duc breathe while on Fire?), and (3) current neuroscience research (e.g. Davidson, Newberg, etc., how did Duc’s brain change with years of meditation to allow him to function in such a way as to calmly expire amidst the flames?). The review, due to the broad scope and historical nature is selective and confines itself to explaining the act of Thich Quang Duc meditating while on fire. Liberty is taken to make connections to Duc and examples are given to elaborate on the neurological underpinnings of meditative self-immolation.

The cornerstone of contemporary neuroscience is the detailed explanation of complex and intricate patterns of behaviour based on a painstaking description of the brain processes involved (Luria, Citation1976). When I peer into the behaviour of Duc I see the manifestation of one of the most profound behaviours observable in humans (Figure ).Footnote4 Volitional self-immolation, quiescent state during extreme pain, complete composure, the act consummating in death. To understand the behaviour of Duc, the history of meditative neuroscience with an emphasis on the Yogi, Samadhi, Fakir, and expert meditators is worth reviewing. The present discussion is not meant to be another review on meditative science, several articles have performed this task gauging our progress from physiology (pulmonary and cardiology effects) to neurobiology (Bishop, Citation2002; Cahn & Polich, Citation2006; Canter, Citation2003; Canter & Ernst, Citation2003; Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, Citation2009; Delmonte, Citation1984; Deshmukh, Citation2006; Dobkin, Citation2008; Gelderloos, Walton, Orme-Johnson, & Alexander, Citation1991; Hofmann, Grossman, & Hinton, Citation2011; Jedrczak, Miller, & Antoniou, Citation1987; Jevning, Wallace, & Beidebach, Citation1992; Keng, Smoski, & Robins, Citation2011; Lindberg, Citation2005; Meyer et al., Citation2012; Orme-Johnson, Citation2006; Ott, Norris, & Bauer-Wu, Citation2006; Rubia, Citation2009; Salmon et al., Citation2004; Salomons & Kucyi, Citation2011; Shapiro & Giber, Citation1978; Wallace & Benson, Citation1972; Woolfolk, Citation1975; Zeidan, Grant, Brown, McHaffie, & Coghill, Citation2012). The current article aims to discuss expert meditators such as Duc, attempting to gain an understanding into how meditation allows one to become a monk on fire.

2. The beginnings of meditation science

The history of the scientific investigation into the neuroscience of mindfulness, meditation, and ascetic monks possessing otherworldly abilities has its beginning in a series of correspondences published early in the 19th century in the journals The Lancet and Nature into what was termed “human hibernation” (Bushe, Citation1837; Busk, Citation1885; Carpenter, Citation1885; Hulk, Citation1885; Twedell, Citation1837). These learned men from a bygone era of science could not understand how a Yogi from India could be buried alive, and moreover upon digging them up “restored to consciousness” (Osborne, Citation1840; Busk, Citation1885, p. 316). They were baffled by what they thought was a “well known Indian trick” (Malcolmson, Citation1838; Hulk, Citation1885, p. 361; Carpenter, Citation1885, p. 408). Their perplexing attitude did nothing to reveal the nature of the meditative mind and behavior. They incredulously brushed meditation off, one author attributing it to the natural division of the world into “knaves and dupes” and apparently gentleman scholars (Bushe, Citation1837, p. 482). Another author indicating a tunnel being dug and the Yogi escaping for the interred period, only returning to reap the fame of being buried alive (Carpenter, Citation1885, p. 408; Hulk, Citation1885, p. 361; see also Bohemian Miners, Citation1892). While previous accounts of the monk “trance,” (Braid, Citation1845) as it was called, cannot be affirmed, current science into meditation is rooted in a strong tradition of empirical experimentation.

The first empirical discussions into meditative minds occurred at the end of the 19th century in the journals Science and Nature (Leumann, Citation1889; Health Matters, Citation1890, p177; Ley, Citation1890; Murray-AynsMurray-Aynsley, Citation1890; Müller, Citation1890; Leumann, Citation1890a; Leumann, Citation1890b). It was Max Müller who bridged an understanding by revealing in his article “Thought and Breathing” that the Sanskrit Yoga-sûtras (sutras) detailed a method called prāṇāyāma (for a review of pranayama see Nivethitha, Mooventhan, & Manjunath, Citation2016) where “the expulsion and retention of breath, as a means of steadying the mind” was central to meditation (Müller, Citation1890, p. 317).Footnote5 It was further astutely indicated that prāṇāyāma consisted of “postures which help him [the Yogi] to fix his mind on certain objects” and that the Yogi “ought to assume a firm and pleasant position, one requiring little effort” (Müller, Citation1890, p. 317) in order to meditate (Figure ). Müller’s article was a gateway into the basic posture-breathing techniques (Figure ) that are the mainstay of Yoga (i.e. meditation) practices, but what about the neurophysiological basis?

Figure 2. Taken from (Rele, Citation1927) of the Padmāsana posture, the legs crossed after the popular image of the Buddha, but slightly modified (Rele, Citation1927, p. 5).

An unknown author indicated in Mental Activity in Relation to Pulse and Respiration that “the blood circulation in the brain is an important factor in its healthy activity, and that the intermittent supply of the same recorded by the pulse, and the intermittent purification of the blood by the lungs in breathing, must also play important parts in the maintenance of mental action, are admitted by all physiologists, though our knowledge of the precise nature of these influences is very limited” (Mental Activity in Relation to Pulse and Respiration, Citation1889). This assertion was an incredible presentiment about the neurophysiological basis of yoga. Although not the prevailing idea, this scientist thought during the 19th century that the brain was the root of this behavior and it was respiration and cardiovascular effects that were the foundation of the behavior. Further, one author stated about meditation that “the use of deep and rapid respiration [could be used] as an anaesthetic,” inducing “to some extent loses [of] consciousness” (Health Matters, Citation1890, p. 177). An RB Pope discussed the opinion of Ernst Leumann a prominent scholar of India at the time (i.e. Indologist), concerning “the influence of blood circulation and breathing, on mind-life,” where a certain “parallelism between pulse acceleration and passion, the rush of ideas in fever” (Pope, Citation1890) appears to exist in meditators. Pope ends his article quoting Emanuel Swedenborg, “It is strange that this correspondence between the states of the brain or mind and the lungs has not been admitted in science” (Pope, Citation1890, p. 297). The discussion was largely of Professor Ernst Leumann’s previous work in Philosophische Studien (journal founded by Wilhelm Wundt) where he simultaneously determined the pulse and respiration rate of individuals (Leumann, Citation1889, Citation1890a, Citation1890b). This discussion was adeptly summarized by Müller’s thought on the practice:

“Here the commentator states that the expulsion means the throwing out of the air from the lungs in a fixed quantity through a special effort. Retention is the restraint or stoppage of the motion of breath for a certain limited time. That stoppage is effected by two acts—by filling the lungs with external air, and by retaining therein the inhaled air. Thus the threefold prāṇāyāma, including the three acts of expiration, inspiration, and retention or breath, fixes the thinking principle to one point of concentration. All the functions of the organs being preceded by that of the breath—there being always a correlation between breath and mind in their respective functions—the breath, when overcome by stopping all the functions of the organs, effects the concentration of the thinking principle to one object” (italics of the present author; Müller, Citation1890, p. 317).

Müller’s comments are accurate forecasts of the current understanding of meditation discussed below. Nevertheless, despite some progress moving forward, articles concerning the “Black Art” and “Indian Conjuring” discussing the magic and trickery of the yogis still abound the pages of scholarly journals (Caulk, Citation1897; Elliot, Citation1936). One of the authors imploring “Once again I would urge readers to look always for a natural explanation of any phenomenon, and when one is not forthcoming, to await the advent of more knowledge, confident that a normal and not a supernormal explanation is always forthcoming, provided that we have the requisite knowledge” (Elliot, Citation1936, p. 427).Footnote6 Naturally Science would have no problem ‘await[ing] the advent of more knowledge,” insofar as the present author knows, but the entire write-off these authors gave as their explanation of the yogi was likely due to their biased opinions of been “dupe[d]” by the deeds of conjurors tricking the “most sensible people” (Elliot, Citation1936). This aforementioned demeaning disposition appears to be the general consensus concerning meditation and mindfulness in the literature of the time.

Shortly thereafter, a series of correspondences in The Lancet attempted to account for a Yogi priest being sealed up in a concrete chamber, both airtight and watertight, for an extended duration (Vakil, Citation1950). The Samadhi Yogi was to “remain in a state of suspended animation and meditation or samadhi,” in their dry concrete tomb for 56 hours and then water was poured-in to fill the chamber for an additional 6 hours (Vakil, Citation1950, p. 871). The authors stated the obvious, the act “cannot be very simply explained,” (van Pelt, Citation1951) and unfortunately, most scholars chiming-in on the debate were more interested in the discrepancy concerning the number of gallons of water which filled the chamber (Greenfielid & Moncrieff, Citation1951), instead of attempting to explain the meditative behavior that the samadhi practiced. The Dr. RJ Vakil who originally reported the feat, apologized for the incorrect reporting of the amount of water filling the chamber, indicating the “point-which I did not explain correctly in the article-is that the priest was completely immersed, and no air-space remained,” (Vakil, Citation1951). It was reported an estimated 10,000 people witnessed the feat (Vakil, Citation1950), not unlike the contemporary feat of the performance artist David Blaine when he encased himself in a plexiglass box suspended 9 meters in the air for 44 days (Korbonits, Blaine, Elia, & Powell-Tuck, Citation2005; see Garbe, Citation1900 for an account in the 1890s). Although not airtight, the immobility and self-starvation is a feat in itself, leading to several issues concerning the “potential dangers of refeeding” (Korbonits, Blaine, Elia, & Powell-Tuck, Citation2007). It was not until the mid-1960’s did experiments into meditation take place and knowledge into these acts was forthcoming. It is worthy to note, that during the aforementioned period lacking the rigors of empirical science, a book was published attempting to describe Yogi practices in scientific terms (Rele, Citation1927. See Vasu Sris Chandra, Citation1895 and others for early). With detailed descriptions of postures and positions of Yogi during meditation, it is an invaluable primer text (Figure ). It appears to be fairly well-received during the period (Stephenson, Citation1928). Contemporary scientists test a hypothesis by rigorous methods and painstakingly exact description of details. It is here an understanding into the meditative mind of the monk is revealed and his behavior explained. Current science may give us a semblant glimpse into the mind of a profound individual such as Duc.

3. Foundations in physiology of meditation: pulmonary & cardiovascular effects

When the author was a youngster, his mother Helen gave him a book on brain and behavior (obviously where his career started) around the same time he discovered the photograph of Duc. In the section titled States of Mind,Footnote7 there is a photograph of an unnamed Samadhi Yogi from India.Footnote8 However, you can only see the hands of the Samadhi eerily emanating from the earth where this individual was buried alive up to their wrists (Figure ). The Samadhi had his head embedded in the earth, no air to fill his lungs and sand encased his body—how was this possible? How did the Samadhi survive? How did this individual breathe while buried alive is crucial to understanding how Duc breathed while on fire—both meditative acts requiring little intake of oxygen. Samadhi is a type of meditation which results in a significant reduction of heart rate (i.e. bradycardia) and breathing (i.e. bradypnea; Wallace & Benson, Citation1972). An emphasis on breathing is either central or an indirect byproduct of many meditation experiences. Breathing techniques lead to drastic physiological changes, not only in respiration, but in heart function and brain processes (Woolfolk, Citation1975). To understand the basis of Duc’s behavior during those last few moments of his life, we have to understand how he controlled his breathing.

Figure 3. Photograph of unnamed Samadhi Yogi from India, depicted from an unknown book of the Author’s childhood (FAM Manno). The picture is on pages 58 and 59 of this book with the chapter possibly titled as “States of Mind.” The caption reads: “Buried alive with his praying hands toward heaven, an Indian yogi is in a trance-like state that reduces his requirement for oxygen.” The author (FAM Manno) would be greatly in debt to the individual who helps him find the title of this book. The beginning of the chapter reads: “Waiting to be buried alive, the yogi sits in cross-legged meditation, half-lidded eyes staring at no one definable spot. University researchers check their watches, eager to demystify the demonstration of mastery over conscious functions. Eventually the ascetic senses that he is ready, rises, and walks with a sleepwalker’s gait to a pit in the ground. He will remain without oxygen for 45 minutes. And he will survive.” (Unknown book, Chapter; States of Mind, p. 59). Any and all help identifying this book would be appreciated.

3.1. Pulmonary effects: breathing rhythm

Meditative breathing is an altered behavioral form of normal breathing (i.e eupnea); therefore, it’s easiest to describe the process we all are very much accustomed to first (see reviews: Despopoulos & Silbernagl, Citation2003; Saladin, Citation2002; Scanlon & Sanders, Citation2010). During normal breathing, inhalation causes the inspirartory muscles to contract the diaphragm located below the lungs, moving it downward in concert with the contraction of the external intercostal muscles which reside on the chest wall, causing your chest to expand upward. As the pressure inside the lungs falls below that of the environment, corresponding to inhalation, air from the atmosphere enters and is taken up at the surface of the lungs. The lungs act as a gas exchanger, taking oxygen and riding the body of carbon dioxide. The process of venting used gases from the lungs, exhalation, occurs by relaxation of the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles. This results in a physical lowering of the chest and concomitant pressure increase inside the lungs, forcing the expired gases to exit (Despopoulos & Silbernagl, Citation2003; Saladin, Citation2002; Scanlon & Sanders, Citation2010). The breathing we normally experience (unconscious breathing, i.e. eupnea), possibly un-noticed throughout the day, is a physiological process under control by an area of the brain called the medulla.Footnote9 This area of the brainstem cyclically forces inhalation and exhalation. A network located in the ventrolateral aspect of the medulla called the pre-Bötzinger complex is the rhythm generating processor for breathing, called a central pattern generator network (Grillner, Citation2011). Without the pre-Bötzinger complex, respiratory rhythm generation and breathing cease. As would be surmised for each different distinct behaviour process, there is a different neural network involved. As an example, eupnea “normal breathing rhythm” has different properties than sighing and gasping (Garcia, Zanella, Koch, Doi, & Ramirez, Citation2011; dyspnea/orthopnea—Whited & Graham, Citation2019; Fukushi, Yokota, & Okada, Citation2019). By will, you can voluntarily control breathing, alternating its rhythm and rate, an ability central to meditation (Wallace, Citation1970). Sensors, such as the carotid body in the carotid artery of your neck report to the medulla internal levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide roaming in your blood (Morris et al., Citation2003). However, when a monk breathes it’s not an exaggeration of the normal process described, it’s quite different. There are few historical descriptions of the behavioral processes describing the physical actions of breathing during meditation in the scientific literature of monks or general meditators (Rele, Citation1927). The present author has seen breathing during meditation in both monks and common practitioners. The inhalations of a monk are not observed as deep breaths, causing the chest to expand upward. Rather, during meditation, inhalations become shallower, and progressively shallower still, the chest movement less and less pronounced, till no movement is discernable. The shallowing inhalations becomes so un-noticeableFootnote10 you may believe a monk is not physically breathing (we could call it vadupnea—Latin/Greek hybrid for the shallow breathing technique of monks, keeping some of the eu in good breathing).Footnote11 The shallow inhalations result in less volume of oxygen intake, in addition to decreases in carbon dioxide elimination (Jevning et al., Citation1992). Here, despite the body receiving less oxygen and ridding itself of less carbon dioxide, the number of physical breaths needed to achieve their respiratory needs decreases too, from 13 per minute during rest to 11 per minute, and even further during meditation (Wallace, Benson, & Wilson, Citation1971). Not only do individuals during meditation need less oxygen, they need fewer breaths to get what they require.Footnote12 Underscoring this point, one study reported a yogi being able to decrease their respiration to one breath per min for one hour (Miyamura et al., Citation2002).

Regulating breathing rhythm while meditating is a common practice, although several different forms and explanations exist (Allison, Citation1970; Farrow & Hebert, Citation1982; Sarang & Telles, Citation2006; Telles, Reddy, & Nagendra, Citation2000), the general empirical explanation of the process is fairly straightforward as described above. Breathing during meditation while on fire is difficult to explain. The present author cannot identify any sources in the literature concerning accounts of breathing while on fire.Footnote13 Even if Duc wanted to breathe, the oxygen surrounding him was probably consumed in the flames around his face long before his will to breathe would have been extinguished. Or did he not desire to breathe at all? The present author would argue Duc did not need to breathe while he was on fire. Moreover, Duc had regulated his breathing rhythmicity to the extent that his intake was significantly modified and minimal during meditation. Asserting this, the present author still finds it a difficult concept: Duc went into his act of self-immolation as a trained meditator, not needing to breathe, he had learned to breathe less, his body requiring less oxygen to live. Duc was so well adapted to meditating, that when on fire, he did not need to breathe or breathed so little the respiratory effects were inconsequential. In view of the brain controlling breathing, the respiration control network in the brain of a monk undergoes immense reconfiguration due to the experience of meditation altering the rhythmicity of natural breathing. One could argue Duc’s ventrolateral aspect of the medulla (the pre-Bötzinger complex), which was responsible for the breathing rhythm had its connectivity so profoundly altered by the half of century he practiced meditation, that while on fire his behaviour was no different than while meditating in the comfort of his vihara among his sangha. One could argue for Duc, the plasticity of the neural network for respiration has been drastically altered by the meditation experience aimed at controlling breathing rate (Morris et al., Citation2003). Furthermore, “respiratory memory”—patterning of the inspiratory-expiratory cycle, was fundamentally modulated from years of practice by the meditator manipulating their breathing (Morris et al., Citation2003, p. 1243). It’s apparent, neuroplasticity in the brain of Duc, due to the years of meditating significantly altered the structure of neurons and their resulting connections in the respiration control center, such that Duc did not breathe when on fire (Mitchell & Johnson, Citation2003). For those minutes while life persisted and he expired among the flames, one could argue Duc was breathing as he always breathed—very minimally (i.e. vadupnea). It would be worthwhile to model the respiratory network of the meditator to demonstrate the natural behavior variations of people who breathe differently (Rybak et al., Citation2004).

3.2. Cardiovascular effects: heart rate and rhythm

Yogis have claimed superhuman feats such as being able to stop the heart and manipulate the pulse. Although reducing the pulse rate, stopping the heart has been unsubstantiated (Wenger, Bagchi, & Anand, Citation1961). Nevertheless, the cardiovascular affects from meditation are profound, altering blood pressure (Nidich et al., Citation2009), aiding in the dissemination of stress-reducing neuro-hormones throughout the circulation (Michaels, Huber, & McCann, Citation1976), thwarting heart disease (Yeh, Davis, & Phillips, Citation2006), and changing blood flow and stress levels in breast cancer patients in as little as 8-weeks (Monti et al., Citation2012). Heart functioning is central to meditation. During meditation, extremely prominent heart rate oscillations become coincident with breathing rhythms. A prominent heart rate was considered a large amplitude oscillation ECG-derived signal related to breathing (Peng et al., Citation1999). This finding was found for both Chinese Chi (i.e. Qigong) as well as Kundalini Yogi meditation compared to healthy adults during metronomic breathing and spontaneous nocturnal breathing (Peng et al., Citation1999). Interestingly, these large amplitude ECG- signals were found in elite triathlonic athletes in the pre-race period (Peng et al., Citation1999). What is noteworthy, different meditation practices resulted in the “presence of intermittent, extremely prominent oscillations” which “appear to contradict a conventional notion of meditation as only a psychologically and physiologically quiescent (“homeostatic”) state” (Peng et al., Citation1999). Heart rate, normally a purely autonomic processes, during meditation is an active process influenced by the meditator. The heart rate affects due to meditation are widespread (Jevning, Anand, Biedebach, & Fernando, Citation1996), such as a reduction in general blood pressure in a group of persons with high normal systolic blood pressure (Barnes, Treiber, & Johnson, Citation2004). The breathing techniques in meditation emphasize relaxation, resulting in interactions between breathing and heart rate, such that “coherence” in cardiopulmonary functioning occurs (Peng et al., Citation2004). Meditation coherence of bodily functions likely underscores physiological uniformity for the whole body, a state that has been termed “hypometabolic integrated response” (Jevning et al., Citation1992). The ultimate ability of these affects is largely unknown, since studying advanced practitioners of meditation, such as Duc, is still in its infancy (underlying the support for more research; Hankey, Citation2006). We know meditation affects breathing, the way you breathe affects your heart beating, and the blood pumped by your heart causes salubrious results throughout the body and in the brain. How does simply breathing and lowering heart rate contribute to the behavior of self-immolation from the powerful mind of a monk? It appears to begin with posture.

Whether the specific practice of meditation emphasizes breathing or not, the meditative effects are largely the same and the behavior to achieve it, nearly identical (Cahn & Polich, Citation2006). How would you begin to meditate? Would you change your posture? Of course you would. The relaxed position is central to meditation (Figure ). A comfortable posture is of utmost importance. Practitioners begin meditation by sitting in a self-referentially relaxed position. This can mean different postures for different people. The position is comfortable enough to allow a long period of no movement, but not so comfortable that it induces sleep, which is not the state of consciousness someone meditating is attempting to achieve. Sitting is preferred, and some meditators conform to the Lotus-position, legs crossed and pulled towards the torso with ankles overlapping one another in your lap, or a variation on a theme of the sitting position. Lying down might be too somnorific, enticing you to sleep. The warm embrace of where-ever you would probably want to lie-down, invites you to doze-off, whereas if you were to lie on a hardened surface you might feel better able to meditate, but likely less comfortable. Standing up might cause too much arousal. As an example, whereas Duc practiced Mahayana Buddhism, which emphasized developing Samadhi, a form of consciousness orienting one’s attention and concentration to self and universal harmony (Deshmukh, Citation2006; Ramamurthi, Citation1995), other forms such as Transcendental MeditationFootnote14 emphasize a process of allowing consciousness to be drawn to `subtler forms of thought` (Lansky & St Louis, Citation2006). The diversity of practices is only limited by the number of practitioners, individual preferences, prior experiences with meditation, and body posture, or how to sit during meditation (Cardoso, de Souza, Camano, & Leite, Citation2004). The brain processes and behaviors ubiquitous to all forms of meditation appear to include components of relaxation (Cahn & Polich, Citation2006), attention (Tang, Rothbart, & Posner, Citation2012), consciousness (Dietrich, Citation2003), and position of self in reference to the environment (Tagini & Raffone, Citation2010). The cumulative effect is promotion of an individual`s health and wellness (Bishop, Citation2002; Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, Citation2004; Rubia, Citation2009).

The respiration effects (pulmonary effects and breathing rhythm), cardiovascular effects (heart rate and rhythm) and posture form the current foundations of meditation science. The future of meditation and mindfulness is how the brain can alter these aforementioned neurophysiological functions. The process of how meditation and mindfulness enable things to occur is difficult to explain. Yogis with extraordinary meditation abilities have been buried alive for over an hour in air-tight boxes—surviving unfazed (Anand, Chhina, & Singh, Citation1961; Yoga, Citation1961; Yoga, Citation1962; Trimble, Citation1962; Karambelkar, Vinekar, & Bhole, Citation1968; Figure ). Yogis can control their respiration and heart rate to require a fraction of the number of breaths and volume of oxygen compared with normal individuals. Extreme exercise of control over their bodies is exemplified by the “coherence” of cardiac and respiratory functions, coinciding in unison. Most importantly, the brains of meditative practitioners, which allow them to carry-out these behaviors, are structurally (Lazar et al., Citation2005) and functionally (Brefczynski-Lewis, Lutz, Schaefer, Levinson, & Davidson, Citation2007) different from our own—if you’re a non-meditator. Nevertheless, their state of mind, albeit altered, may not be so different from us normal humans after all, with meditation practice closing the brain-gap (Allen et al., Citation2012; Monti et al., Citation2012). All who desire may one day be a monk on fire. If this is not your ultimate aspiration, no worry, meditation still changes your brain (Zeidan et al., Citation2011), even after a short time practicing (Keng et al., Citation2011), and it starts with respiration and cardiovascular changes.

4. Beginning of structure-function correlates of the meditative mind

For meditators, several areas of the brain are related functionally to attentional processes or structurally altered due to decades of meditation. The brain and mind of a monk will be divided into three research avenues currently pursued, structures of interest, functioning, and pain sensation. Here, the following topics will be discussed: physiology, brain structure and function, pain, awareness, attention, and consciousness. For Duc, these structural-functional alterations reached their pinnacle as he was able to perform his normal meditative behavior under the extreme conditions of self-immolation.

4.1. Structural alterations elicited from meditation

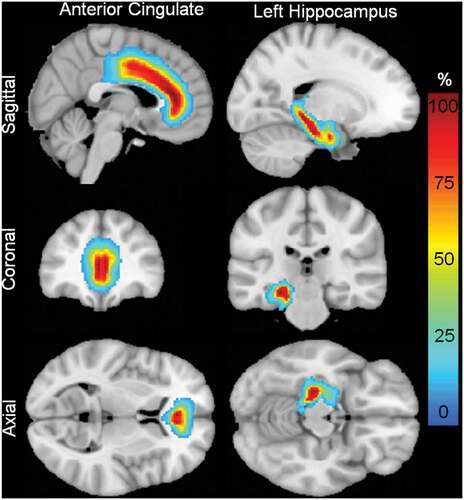

The cortex of typical people who had practiced meditation for around 9 years, for at least 40 min every day, had several differences from non-meditators (Lazar et al., Citation2005). The benchmark study analyzed cortical thickness which is a ratio of gray matter to white matter and found the right anterior insula, right middle & superior frontal sulci (Brodmann area 9), left superior temporal gyrus (i.e. auditory cortex), and the fundus of central sulcus somatosensory cortex (Brodmann area 3a) where generally thicker in meditators (i.e. more gray matter; Lazar et al., Citation2005). The most prominent and significant difference between meditators and non-meditators was the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula (Hölzel et al., Citation2008; Figure ). These areas are central to pain processing, attention and introception or the bodily and visceral awareness of oneself, with thicker areas of the cortex (gray matter) in individuals who have been meditating longer. Interestingly, the anterior cingulate cortex is connected to the somatosensory area, prefrontal cortex and periaqueductal gray, forming part of the “ACC–fronto–PAG pathway” (Bushnell, Ceko, & Low, Citation2013). The authors of the review indicate: “huge inter-individual as well as intra-individual differences in pain perception depend on the context and meaning of the pain. [Here,] much of this variation can be explained by the interplay between afferent nociceptive signals to the brain and descending modulatory systems that are activated endogenously by cognitive and emotional factors” (Bushnell et al., Citation2013). For a Monk like Duc, a descending modulatory input (the change to his higher cortical areas) allowing the attenuation of the nociceptive/pain signal would have been his training as a meditator. Studies of functional connectivity have indicated stronger coupling in experienced meditators in the ACC–fronto–PAG pathway, which has been suggested to indicate increased cognitive control of functioning in these regions (Brewer et al., Citation2011; Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, Citation2015). The training of Duc likely altered the efferent (from brain to body) pain pathway, allowing him to top-down modulate his perception and expectation to the pain stimulus (the afferent input—pain-to-brain).

Figure 4. Probabilistic map of finding the bilateral anterior cingulate gyrus and left hippocampus. Colorbar represents 0 to 100% probability.

These alterations are extremely relevant to an expert meditator such as Duc who had practiced meditation for over 50 years. Duc’s brain had changed profoundly in its structure due to the innumerable hours meditating over the half a century he lived. In this regard, several studies have found age-dependent effects associated with length and time of meditation. For example, gray matter concentration in the left inferior temporal gyrus was predicted by the amount of meditation training (Hölzel et al., Citation2008), and a notable difference in the age-related decline of cerebral gray matter volume was found in the putamen between regular Zen meditators and control subjects (Pagnoni & Cekic, Citation2007). A primary area of the brain determined to be altered due to meditation has been the anterior cingulate and areas of the insular cortex (Craig, Citation2009; Figure ). A subsequent study found the anterior cingulate cortex, bilateral parahippocampal gyrus, anterior insula, and bilateral lower leg area in primary somatosensory cortex, and hand area right hemisphere (Grant, Courtemanche, Duerden, Duncan, & Rainville, Citation2010; See Figure for posture) were significantly changed in meditators. These studies provide a basic understanding of how a behavioral practice such as meditation can alter the brain in individuals who practice consistently and continuously for a long duration. Duc was an expert meditator with over half a century of experience, meditating countless hours a day. The structure of the brain provides us a basic understanding for how it may function, an underlying framework and it is the functioning of Duc’s brain that allows the behavior we know him by, volitional self-immolation—the will and ability to set oneself on fire.

4.2. Reduced pain sensitivity in meditators: functioning of the meditative mind

How did Duc deal with the pain of being burned alive? A monk practicing meditation alleviates pain by orienting their consciousness and focus of attention (Zeidan et al., Citation2012).Footnote15 One would think away from the object causing the pain, right? Wrong. Mindfulness practitioners are able to reduce pain by increasing their awareness to the unpleasant stimuli (Gard et al., Citation2012). In Zen meditation, a reduction in activation was found in executive/evaluative areas such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus (Figure ) while an increase in activation was found in the anterior cingulate (Figure ) and insular cortex, resulting in practitioners viewing painful stimuli more neutrally (Grant, Courtemanche, & Rainville, Citation2011). Here it was revealed that increased insula activation during mindfulness was correlated to a reduction in pain unpleasantness, suggesting the region is involved with pain attenuating effects. During the process of focusing a meditators attention, the lower sensitivity to pain and the ability to modulate intense pain correlates with slowing of the respiratory rate and increases with greater meditation experience (Grant & Rainville, Citation2009). Pertinent to these studies, with only 4 days of meditation training at 20 minutes per day, the presentation of a painful stimulus to meditators was significantly reduced. Moreover, a correlation was found between thickness in the inferior occipito-temporal visual cortex and change in respiration rate (Lazar et al., Citation2005). With the structural-functional studies, it is important to note that respiration and breathing are central themes to revealing how expert meditators achieve feats such as Duc.

Underscoring the importance of meditation experience and respiration induced brain alterations, another important contemporary example, is the Wim Hof method of meditation (WHM). The WHM of breathing consists of cyclic hyperventilation followed by breath retention, and ice-cold water immersion, which has been proposed to attenuate the immune response (Kox et al., Citation2014). In a benchmark study, participants were trained for 10 days in the WHM and subsequently injected with a bacterial endotoxin (Escherichia coli endotoxin) inducing temporary fever, headache and shivering (Kox et al., Citation2014). Here it was found, trained individuals increased the release of epinephrine, which in turn led to increased production of anti-inflammatory mediators and dampening of the proinflammatory cytokine response elicited by the endotoxin (Kox et al., Citation2014). To correlate this with Duc, it is possible his marked ability to withstand pain was related to a dampened response to a painful stimulus. The remarkable aspect of the above study (Kox et al., Citation2014) was the short duration of training in meditation and breathing techniques (Tang et al., Citation2007), elicited profound sympathetic nervous system and immune system modulation.Footnote16

Functionally this means the brain can change with very little training. Being able to withstand extreme pain is fundamental toward understanding how Duc sat calmly and composed while his life expired amidst the flames. Using fMRI, reduction in pain unpleasantness and pain intensity was revealed in meditators (Zeidan et al., Citation2011). The pain tolerating ability of Duc had to be very high. The feeling of gasoline over your body permeating your clothes, burning your skin must be like drowning in a bath of super-heated butter. The hot butyraceous (butter-like) feeling on your finger burned by a cooking pan is probably the closest one has been, and stayed alive, to being inundated by gasoline, and burned alive. Duc had to endure much more pain than this example. His entire body was covered by flames and he is seen falling over in the video a few minutes after the onset. Years of practice, numerous hours a day prepared him for this ultimate fate. Interestingly, pain intensity ratings by meditators were associated with increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula as seen by functional MRI (Zeidan et al., Citation2011). These regions were identical to the regions seen to change structurally in meditators versus non-meditators (Lazar et al., Citation2005). Although the meditators of Zeidan et al. (Citation2011) were novice to meditation, a subsequent study (Brefczynski-Lewis et al., Citation2007) has found drastic differences between expert meditators and novices. Slight variations in expert meditator experience, such as those with 19,000 hours of practice are considerably different from those with 44,000 hours of practice (Brefczynski-Lewis et al., Citation2007). There are also differences associated with different meditation techniques (Perlman, Salomons, Davidson, & Lutz, Citation2010). With over 50 years of meditative practice, the structure and functioning of Duc’s brain underscores how he carried out such a profound action. Underscoring pain tolerance, a yoga master claimed that during meditation he could not feel pain when shot with a laser applied to the back of their foot while his brain was imaged separately with functional MRI (fMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG). Recording with fMRI or MEG during meditation revealed weak or absent levels of activation from primary pain areas such as the thalamus, secondary somatosenory cortex, and cingulate cortex (Kakigi et al., Citation2005). The lower sensitivity to unpleasant stimuli has been associated with a thicker gray matter cortex in pain-related brain regions including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and hours of experience predicted gray matter bilaterally in the lower leg area of the primary somatosensory cortex as well as the hand area in the right hemisphere (Grant et al., Citation2010). If we could peer into the brain and mind of Duc, what would we see? I imagine we would see a highly differentiated brain structure with a tremendous ability to modulate the structure’s functioning and this is related to the half century of meditative practice. These changes, coupling executive and sensory processes are associated with an immense ability to withstand pain. Continued research in brain structural-functional studies will hopefully reveal how expert meditators seemingly perform tasks such as Duc’s self-immolation.

5. Conclusions

Contemporary scholars argue Duc’s self-immolation was the culmination of the Buddhist Crisis in South Vietnam (Solheim, Citation2008; Halberstam & Singal, Citation2008, p127). Duc’s venerable act was followed by the CIA-backed coup d’état of General Dương Văn Minh on 1 November 1963, and subsequent assassination of president Ngo Dinh Diem in the following days (Solheim, Citation2008; Halberstam & Singal, Citation2008, p. 127). Political events aside, the self-immolation behavior of Duc captivated the world and is emblematic of a cultivated mind-state. Duc’s act was the epitome of a profound behavior, able to be elicited with careful practice, volition, and experience. The state of mind cultivated allowing the self-immolation behavior is what draws onlookers to Duc. We respectfully wonder, we are held captive, and our memory is entranced by his image. How is it possible for Duc to willingly undergo such an act? Neuroscientists are beginning to understand it’s the brain’s structure and function altered due to numerous hours of meditation that enabled Duc to become the Monk on Fire. No other image has captivated the author more than that of seeing Duc motionless, soundless, and in a state of equanimity as he burned to death. While we may never know why Duc set himself on fire or be able to ascertain definitively the how surrounding the behavior, physiology, structure/function neural correlates and psychology of Monks, the author believes the meaning of the Monk on Fire is much more accessible and clear. The meaning is easily discernable from the image and understandable to everyone that sees Duc expire among the flames: motionless and quiescence were his fundamental meaning and behaviour. As Duc expired among the flames, the behavioural act of with-during pain without sacrificing composure, and foremost His silent and motionless actions—while most of us probably could not light the match, and those who would, immediately experience regret about their decision—Duc seems peacefully calm and collected about his decision while he died. This is a profound and utmost powerful concept and causa causans for being: motionless and quiescence was the fundamental meaning expressed by the burning monk. In this day in age, where actions possess more efficacy to the point when they are loud and full of motion, in an era where heady gestures are deemed more appropriate than restrained composure, and where war is as omnipresent as ever, despite us being privy to 50 years of atrocities from the days of Duc thenceforth, I suggest it’s imperative, nah an absolute requirement, we ruminate on the burning monk. When we fully understand the burning monk, we might attempt preventing the horrific events fomenting such extreme actions. I argue this is the result of the burning monk—simply to grasp the monk on fire, Duc.

“The sequences and conjoined arrays of qualia entailed by this neural activity are the higher-order discriminations that such neural events make possible. Underlying each quale are distinct neuroanatomical structures and neural dynamics that together account for the specific and distinctive phenomenal property of that quale. Qualia thus reflect the causal sequences of the underlying metastable neural states of the complex dynamic core. The relationship of entailment between these neural states and the corresponding states of consciousness has the property of fidelity … The qualia that constitute these discriminations are rich and subtle. The fact that it is only by having a phenotype capable of giving rise to those qualia that their ‘‘quality’’ can be experienced is not an embarrassment to a scientific theory of consciousness. Looked at in this way, the so-called hard problem is ill posed, for it seems to be framed in the expectation that, for an observer, a theoretical construct can lead by description to the experiencing of the phenomenal quality being described. If the phenomenal part of conscious experience that constitutes its entailed distinctions is irreducible, so is the fact that physics has not explained why there is something rather than nothing.”

Gerald M. Edelman (Citation2003), intellectualizing consciousness.

Supplymental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (17.4 MB)Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Francis A. Manno Jr., Helen D. Manno and Sinai Hernandez-Cortes Manno for all their support. The author thanks Drs. Condon Lau and Shuk Han Cheng for their academic involvement.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Francis A.M. Manno

Dr. Francis A.M. Manno studied biology and psychology (A.B.) at a small liberal arts school in Virginia (VWC), molecular biology at New York University (MSc), Scuba Diving in México and has a Master Captains License from the USCG. He completed his first Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Neuroimaging and a second PhD in Physics and Applied Materials Sciences. Dr. Manno is directing a multisite collaboration concerning the genetic alterations related to the cortical manifestations in hearing loss. Dr. Manno is interested in sensory processes that go awry, the interpretation of uncertainty/errors, and the properties/propagation of waves in systems. The present article was written to gain a greater understanding into the neurobiology of meditation and mindfulness, with an emphasis on Duc.

Notes

1. Written without the Vietnamese tonal accents and diacritics (Thích Quảng Đức).

2. It was around the summer of 1996 when I came across the Rage album for the first time. I was a near fourteen-year-old washing windows on the Outer Banks, North Carolina for a summer job and staining cedar shingles at my Fathers business. One thing was certain: Rage chose the album cover well. I droned out to the music of Rage during my mindless work. The progressive-left leaning Rage seamlessly weaved metal-rock and rap lyrics that flowed like waves of fire off the body of Duc. High-amplitude power chords chasing frequented bass beats and stanzas describing scenes from the Zapatista movement in Chiapas, Mexico to Noam Chomskian realpolitik, established reasons of suffering relatable to Duc’s action. You could peer into the eyes of Duc on the album cover, photographed by Malcolm Browne, and see the same empathy and sentiment Rage was conveying in their music. As a youth, I could not understand how Duc could calmly set himself on fire—I did not understand the behaviour-brain relations behind self-immolation. As an adult studying behavioural neuroscience, I am confident the meditative mind of Duc and his behaviour of self-immolation are explainable—all is revealed by the brain.

3. One reviewer has noted: “Furthermore, there is currently debate over the accuracy and reliability of studies that purport to investigate ‘expert meditators’ because there are no concrete grounds for discerning whether a meditator is an expert. Simply because a person has practiced meditation for 20 years does not mean they are an expert (they could have been practising incorrectly for 20 years). Likewise, simply because a person is deemed to be the head of a particular Buddhist school does not by default demonstrate they are advanced in meditation. The manuscript makes no reference to this ongoing debate.” This is true, but to digress does nothing to explain the behavior of self-immolation. That these behaviors exist, is cause enough as a scientist to explain them. Whether the monk Duc was an expert or not does not change the behavior of self-immolation. The article attempts to explain a complex behavior based on neurological underpinnings. If self-immolation requires being an expert, then Duc was surely expert. If self-immolation does not necessitate being an “expert” than the reviewer could perform it.

4. One reviewer has astutely indicated: “ … some Buddhist schools would condemn that act [behavior] as constituting a form of religious extremism, attachment to political and/or moral ideals, and thus in direct opposition to the very principles of non-attachment and non-violence (including to oneself) that underlie Buddhist practice.” This is true, but it does nothing to explain the behavior. As a neuroscientist we are tasked with explaining the neurobehavioral foundations that allow self-immolation to occur. Just like extremism, politics, religion, racism, morality, etc.,—complex behaviors, it is our duty as neuroscientists to formulate the biological background which enables these behaviors to occur. Great past examples include assessing Einstein’s brain to ascribe his abilities in mathematics and physics (Falk, Citation2009; Witelson, Kigar, & Harvey, Citation1999) or the methods of interrogation and indoctrination to understand menticide (Hinkle & Wolff, Citation1965).

5. The Sacred Books of the East: Buddhist Mahâyâna Texts Volumes. (1894). Edited by Friedrich Max Müller, Translated by Edward Byles Cowell. See the entire series edited by Max Müller. The Sacred Books of the East series printed by the Oxford University Press between 1879 and 1910. Found on the Internet Sacred Text Achieve (https://www.sacred-texts.com/sbe/).

6. It is worthy to note that RH Elliot wrote a book, The Myth of the Mystic East on “Indian Conjuring” and debunking the “Rope Trick” (Elliot, Citation1934, Elliot R.H, Citation1936; Obituary for Elliot, R. H. (Citation1936)). The book was reviewed as derogatory in the present day (Siegel, Citation1991, p. 200).

7. Unfortunately, the author of the present manuscript cannot seem to find the name of the book and only has a PDF of two pages from the chapter (saved by his Mother Helen) with the unnamed Samadhi Yogi. Any and all help identifying this book would be greatly appreciated. Please see figure for more details (Figure ).

8. Yoga meaning union has a general definition: A higher consciousness achieved through a rested and relaxed body and mind (yogi—yoga practitioner; Wallace & Benson, Citation1972). Samadhi is considered by practitioners a higher meditative form in which they become oblivious to both internal and external environmental stimuli, allowing them to reach a state of ecstasy (i.e. mahanand). Page 503, from (Tart, Citation1969).

9. The sport of breadth-holding is a defined science (Parkes, Citation2006). The world record is held by Stéphane Mifsud of France at 11 min 35 sec. Breadth-holding and meditative breathing are two distinct behavioural activities/practices.

10. See the final scenes of Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1993 film Little Buddha, where the Monk expires while meditating.

11. Find a monk or someone meditating, put your fingers discretely under their nose, sometimes you can feel air. If not, I assure you they are still breathing, but have regulated their intake to a minimum. If you didn’t get swatted away by the “fingers under a monk’s nose experiment,” … take a deep breath and walk slowly away, before you do. Try someone else to enlarge your sample size if bravery abounds you.

12. For some meditators their is a genetic component. A recent study assessed Tibetan highland individuals compared to Chinese and Japanese lowland populations to determine if high-altitude adaptation in Tibetans resulted from local positive selection on distinct genes (Simonson et al., Citation2010). The study found “positively selected haplotype of EGLN1 was significantly associated with the decreased hemoglobin phenotype that is unique to this highland population” (Simonson et al., Citation2010). Two genes identified in Tibetans were particularly interesting, EGLN1 and EPSI1—downstream. EGLN1 has been previously shown to be under selection in Andeans (Bigham et al., Citation2009). EPSI1 and EGLN1 are genes are in the Panther-defined pathway “hypoxia response via activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)” (Mi, Guo, Kejariwal, & Thomas, Citation2007). This pathway is a major transcriptional regulator of oxygen homeostasis (Semenza, Citation2010). Interestingly, EGLN1 showed a significant negative correlation with hemoglobin concentration. The authors stated “EGLN1 targets two HIFα proteins for degradation under normoxic conditions, decreasing the transcription of HIF-regulated targets such as EPO, the erythropoietin gene whose product induces red blood cell (RBC) production.” Here we have digressed; nevertheless, monks who need less oxygen due to their oxygen regulation endophenotype associated with high-altitude selection, have inherited (italic for gene) the need for less oxygen.

13. Please inform the author if literature exists of breathing while on fire. Excluding the utilization of respiratory devices, such as that by firefighters.

14. Largely brought to the West by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Traditionally, yoga was a venture of ascetics in the East.

15. Consciousness was a difficult subject to include in the review, due to the lack of research. Some would argue the following concerning expert consciousness: Tibetan Buddhist monks meditating and Carmelite nuns having a mystical experience activate similar brain areas (Beauregard & Paquette, Citation2006; Newberg et al., Citation2001), despite in their aspects of consciousness, Buddhists having the object of “nothing” and Carmelite nuns having a subject of “something” as the focal point of their state. Interestingly, this line of reasoning would provide support for the Fischerian Varieties of Consciousness (Fischer, Citation1971; see Figure ). The Buddhist monks depart on the perception-meditation continuum of increasing trophotropic arousal reaching a hypoaroused state, whereas the Carmelite nuns depart on the perception-hallucination continuum of increasing ergotropic arousal reaching a hyperaroused state, theoretically. The monk Duc may have become hypoaroused, inducing a state of consciousness where he departed from “I”, allowing attainment/fulfillment of his “self”. Here, both Monk and Nun states depart from “I,” of the physical environment moving toward the “Self” of the inner state of consciousness (Fischer, Citation1971). Incorporating the Fischerian Varieties of Consciousness (Fischer, Citation1971), the Tartian states of consciousness experience (Tart, Citation1969, Citation1972) and consumption of exogenous substances (entheogen - peyote (Lophophora williamsii), empathogen/entactogen - ecstasy (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine), and hallucinogens, etc: Nichols, Yensen, Metzner, & Shakespeare, Citation1993).

The Fischerian varieties of consciousness: Perception-hallucination continuum of increasing ergotropic (sympathetic dominate) arousal (left) and perception-meditation continuum of increasing trophotropic (parasympathetic dominate) arousal (right). These levels of hyperarousal and hypoarousal are interpreted by humans as normal, creative, psychotic, and ecstatic states (left) and Zazen and samadhi (right). The loop connecting ecstasy and samadhi represents the rebound from ecstasy to samadhi, which is observed in response to intense ergotropic excitation. The monk Duc may have been rebounding in ‘self” due to modulation of the anterior cingulate cortex (Devinsky, Morrell, & Vogt, Citation1995). From Fischer, Science. (Citation1971):174:897. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

16. For example, one reviewer has expressed the desire to “[discuss] psychophysiological self control through the lens of the autonomic nervous system.” In this regard, and not delving to far, the entropic brain hypothesis was recently proposed (Carhart-Harris et al., Citation2014). This theory is a correlation between states of consciousness, where consciousness is entropy in suppression/expansion. Entropy here is a measure of the disordered brain state, is suppressed in normal waking consciousness and therefore, relieved of its constraints (expansion) in altered states of consciousness such as taking LSD, thus displaying a higher state of entropy (disorder). The authors utilize the entropy hypothesis much like a set-point (as in homeostasis, the Bernard-Cannon sense | Cacioppo, Tassinary, & Berntson, Citation2007. p433; Kandel, Schwartz, & Jessel, Citation2000. p1000) affected along the X-Y axis of high entropy states (altered states of consciousness such as in the psychedelic experience), midpoint of normal waking consciousness, and low entropy states (such as in coma). The Bernard-Cannon relation (and finally the autonomic nervous system delve) could be thought of as in the fight-or-flight response (sympathetic nervous system)/rest-and-digest/feed-and-breed (parasympathetic nervous system), but more subtle activities in meditation and mindfulness. We could argue the setpoint for a meditator/practitioner of mindfulness is altered compared to controls (Figure ). Since these are newer theories, we will not digress further.

References

- Allen, M., Dietz, M., Blair, K. S., van Beek, M., Rees, G., Vestergaard-Poulsen, P., … Roepstorff, A. (2012, October 31). Cognitive-affective neural plasticity following active-controlled mindfulness intervention. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 32(44), 15601–21. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2957-12.2012

- Allison, J. (1970, April 18). Respiratory changes during transcendental meditation. Lancet, 1(7651), 833–834. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(70)92427-x

- Anand, B. K., Chhina, G. S., & Singh, B. (1961, January). Studies on Sri Ramanand Yogi during his stay in an air-tight box. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 49(1), 82–89. PMID: 23168716.

- Barnes, V. A., Treiber, F. A., & Johnson, M. H. (2004, April). Impact of transcendental meditation on ambulatory blood pressure in African-American adolescents. American Journal of Hypertension, 17(4), 366–369. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.12.008

- Beauregard, M., & Paquette, V. (2006). Neural correlates of a mystical experience in Carmelite nuns. Neuroscience Letters, 405, 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.060

- Bigham, A. W., Mao, X., Mei, R., Brutsaert, T., Wilson, M. J., Julian, C. G., … Shriver, M. D. (2009, December). Identifying positive selection candidate loci for high-altitude adaptation in Andean populations. Human Genomics, 4(2), 79–90. doi:10.1186/1479-7364-4-2-79

- Bishop, S. R. (2002, January–February). What do we really know about mindfulness-based stress reduction? Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(1), 71–83. doi:10.1097/00006842-200201000-00010

- Bohemian Miners. (1892). Buried alive for seventeen days. The Lancet, 140, 264. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)86190-0

- Braid, J. (1845). Queries respecting the alleged voluntary trance of fakirs in India. The Lancet, 46, 325–326. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)87718-2

- Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., Lutz, A., Schaefer, H. S., Levinson, D. B., & Davidson, R. J. (2007, July 3). Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(27), 11483–11488. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606552104

- Brewer, J. A., Worhunsky, P. D., Gray, J. R., Tang, Y. Y., Weber, J., & Kober, H. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 20254–20259. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112029108

- Browne, M. W. (1968). The new face of war (pp. 262). Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Browne, M. W. (1993). Muddy boots and red socks: A reporter’s life (pp. 12). New York, NY: Times Books.

- Bushe, C. K. (1837, March 26). Human hibernation. Nature, 31, 482. doi:10.1038/031482b0

- Bushnell, M. C., Ceko, M., & Low, L. A. (2013, July). Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 14(7), 502–511. doi:10.1038/nrn3516

- Busk, K. (1885, February 05). Hibernation. Nature, 31, 316–317. doi:10.1038/031316e0

- Cacioppo, J. T., Tassinary, L. G., & Berntson, G. (2007). Handbook of psychophysiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cahn, B. R., & Polich, J. (2006, March). Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 180–211. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180

- Canter, P. H. (2003). The therapeutic effects of meditation. BMJ, 326, 1049–1050. doi:10.1007/bf03040500

- Canter, P. H., & Ernst, E. (2003, November 28). The cumulative effects of transcendental meditation on cognitive function–A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift, 115(21–22), 758–766. doi:10.1007/bf03040500

- Cardoso, R., de Souza, E., Camano, L., & Leite, J. R. (2004, November). Meditation in health: An operational definition. Brain Research. Brain Research Protocols, 14(1), 58–60. doi:10.1016/j.brainresprot.2004.09.002

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Leech, R., Hellyer, P. J., Shanahan, M., Feilding, A., Tagliazucchi, E., … Nutt, D. (2014, February 3). The entropic brain: A theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 20. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020

- Carpenter, W. B. (1885). Human hibernation. Nature, 31, 408. doi:10.1038/031408b0

- Caulk, W. B. (1897). Black art. Scientific American, 8, 123. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican08211897-123

- Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009, August). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005

- Craig, A. D. (2009, January). How do you feel — Now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 10(1), 59–70. doi:10.1038/nrn2555

- Delmonte, M. M. (1984, November). Electrocortical activity and related phenomena associated with meditation practice: A literature review. The International Journal of Neuroscience, 24(3–4), 217–231. doi:10.3109/00207458409089810

- Deshmukh, V. D. (2006, November 16). Neuroscience of meditation. Scientific World Journal, 6, 2239–2253. doi:10.1100/tsw.2006.353

- Despopoulos, A., & Silbernagl, S. (2003). Color Atlas of Physiology. (5th ed., pp. 106–137). Thieme. Chapter 5 Respiration. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag.

- Devinsky, O., Morrell, M. J., & Vogt, B. A. (1995, February). Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain, 118(Pt 1), 279–306. doi:10.1093/brain/118.1.279

- Dietrich, A. (2003, June). Functional neuroanatomy of altered states of consciousness: The transient hypofrontality hypothesis. Consciousness and Cognition, 12(2), 231–256. doi:10.1016/s1053-8100(02)00046-6

- Dobkin, P. L. (2008, February). Mindfulness-based stress reduction: What processes are at work? Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 14(1), 8–16. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.09.004

- Dong, C. M., Leong, A. T. L., Manno, F. A. M., Lau, C., Ho, L. C., Chan, R. W., … Wu, E. X. (2018). Functional MRI investigation of audiovisual interactions in auditory midbrain. 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). doi:10.1109/embc.2018.8513629

- Edelman, G. M. (2003). Naturalizing consciousness: A theoretical framework. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(9), 5520–5524. doi:10.1073/pnas.0931349100

- Elliot, R. H. (1934). (Elliot, Lieut.-Colonel Robert Henry 1864-1936). The Myth of the Mystic East. Edinburgh and London: WM. Blackwood & Sons Ltd.

- Elliot, R. H. (1936, September 12). Indian conjuring. Nature, 138, 425–427. doi:10.1038/138425a0

- Elliot, R. H., & Lieut-Colonel, R. H. (1936). Elliot Death. Nature, 138, 913–914. doi:10.1038/138913b0

- Falk, D. (2009, May 4). New information about Albert Einstein’s brain. Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience, 1, 3. doi:10.3389/neuro.18.003.2009

- Farrow, J. T., & Hebert, J. R. (1982, May). Breath suspension during the transcendental meditation technique. Psychosomatic Medicine, 44(2), 133–153. doi:10.1097/00006842-198205000-00001

- Fischer, R. (1971). A cartography of conscious states: The experimental and experiential feature of a perception-hallucination continuum. Science, 174, 897–904. doi:10.1126/science.174.4012.897

- Fukushi, I., Yokota, S., & Okada, Y. (2019, July). The role of the hypothalamus in modulation of respiration. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology, 265, 172–179. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2018.07.003

- Garbe, R. (1900). On the voluntary trance of Indian Fakirs. Monist, 10(4), 481–500. doi:10.5840/monist190010432

- Garcia, A. J., 3rd, Zanella, S., Koch, H., Doi, A., & Ramirez, J. M. (2011). Chapter 3–Networks within networks: The neuronal control of breathing. Progress in Brain Research, 188, 31–50. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53825-3.00008-5

- Gard, T., Hölzel, B. K., Sack, A. T., Hempel, H., Lazar, S. W., Vaitl, D., & Ott, U. (2012, November). Pain attenuation through mindfulness is associated with decreased cognitive control and increased sensory processing in the brain. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991), 22(11), 2692–2702. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhr352

- Gelderloos, P., Walton, K. G., Orme-Johnson, D. W., & Alexander, C. N. (1991, March). Effectiveness of the Transcendental Meditation program in preventing and treating substance misuse: A review. The International Journal of the Addictions, 26(3), 293–325. doi:10.3109/10826089109058887

- Grant, J. A., Courtemanche, J., Duerden, E. G., Duncan, G. H., & Rainville, P. (2010, February). Cortical thickness and pain sensitivity in zen meditators. Emotion, 10(1), 43–53. doi:10.1037/a0018334

- Grant, J. A., Courtemanche, J., & Rainville, P. (2011, January). A non-elaborative mental stance and decoupling of executive and pain-related cortices predicts low pain sensitivity in Zen meditators. Pain, 152(1), 150–156. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.006

- Grant, J. A., & Rainville, P. (2009, January). Pain sensitivity and analgesic effects of mindful states in Zen meditators: A cross-sectional study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(1), 106–114. doi:10.1097/psy.0b013e31818f52ee

- Greenfielid, A. D. M., & Moncrieff, R. W. (1951). Endurance feat by a yogi priest. The Lancet, 257(6645), 56–57. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(51)93534-9

- Grillner, S. (2011). Chapter 13–On walking, chewing, and breathing–A tribute to Serge, Jim, and Jack. Progress in Brain Research, 188, 199–211. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53825-3.00018-8

- Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004, July). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00573-7

- Halberstam, D., & Singal, D. J. (2008). Chapter 8 The buddhist revolt begins. In The making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam during the Kennedy Era (pp. 127). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hankey, A. (2006, December 3). Studies of advanced stages of meditation in the Tibetan buddhist and vedic traditions. I: A comparison of general changes. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : eCAM, 3(4), 513–521. doi:10.1093/ecam/nel040

- Health Matters. (1890). Thought and respiration. Science, 15, 177. doi:10.1126/science.ns-15.371.177

- Hinkle, L. E., & Wolff, H. G. (1965). Communist interrogation and indoctrination of “Enemies of the States”: Analysis of methods used by the communist state police (A special report). AMA Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry, 76(2), 115–174. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1956.02330260001001

- Hofmann, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. (2011, November). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1126–1132. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.003

- Hölzel, B. K., Ott, U., Gard, T., Hempel, H., Weygandt, M., Morgen, K., & Vaitl, D. (2008, 3). Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxel-based morphometry. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Mar(1), 55–61. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm038

- Hulk, A. H. (1885, February 19). Human Hibernation. Nature, 31, 361. doi:10.1038/031361a0

- Jedrczak, A., Miller, D., & Antoniou, M. (1987). Transcendental meditation and health: An overview of experimental research and clinical experience. Health Promotion International, 2(4), 369–376. doi:10.1093/heapro/2.4.369

- Jevning, R., Anand, R., Biedebach, M., & Fernando, G. (1996, March). Effects on regional cerebral blood flow of transcendental meditation. Physiology & Behavior, 59(3), 399–402. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(95)02006-3

- Jevning, R., Wallace, R. K., & Beidebach, M. (1992, Fall). The physiology of meditation: A review. A wakeful hypometabolic integrated response. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 16(3), 415–424. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80210-6

- Kakigi, R., Nakata, H., Inui, K., Hiroe, N., Nagata, O., Honda, M., … Kawakami, M. (2005, October). Intracerebral pain processing in a Yoga Master who claims not to feel pain during meditation. European Journal of Pain (london, England), 9(5), 581–589. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.12.006

- Kandel, E., Schwartz, J., & Jessel, T. (2000). Principles of neural science (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional.

- Karambelkar, P. V., Vinekar, S. L., & Bhole, M. V. (1968, August). Studies on human subjects staying on an air-tight pit. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 56(8), 1282–1288. PMID: 5711607.

- Keng, S. L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011, August). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006

- Korbonits, M., Blaine, D., Elia, M., & Powell-Tuck, J. (2005, November 24). Refeeding David Blaine–Studies after a 44-day fast. The New England Journal of Medicine, 353(21), 2306–2307. doi:10.1056/nejm200511243532124

- Korbonits, M., Blaine, D., Elia, M., & Powell-Tuck, J. (2007, August). Metabolic and hormonal changes during the refeeding period of prolonged fasting. European Journal of Endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies, 157(2), 157–166. doi:10.1530/eje-06-0740

- Kox, M., van Eijk, L. T., Zwaag, J., van den Wildenberg, J., Sweep, F. C., van der Hoeven, J. G., & Pickkers, P. (2014, May 20). Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(20), 7379–7384. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322174111

- Lansky, E. P., & St Louis, E. K. (2006, November). Transcendental meditation: A double-edged sword in epilepsy? Epilepsy & Behavior : E&B, 9(3), 394–400. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.04.019

- Lau, C., Manno, F. A. M., Dong, C. M., Chan, K. C., & Wu, E. X. (2018). Auditory-visual convergence at the superior colliculus in rat using functional MRI. 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). doi:10.1109/embc.2018.8513633

- Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T., … Fischl, B. (2005, November 28). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport, 16(17), 1893–1897. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19

- Leumann, E. (1889). Die Seelenthätigkeit in ihrem Verhältniss zu Blutumlauf und Athmung. Philosophische Studien, 5, 618–631. [Leumann, Ernst. 1889. The soul’s activity in relation to blood circulation and respiration. Philosophical Studies 5: 618-631]. Retrieved from https://vlp.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/references?id=lit4173&page=p0618

- Leumann, E. (1890a). Breathing. Nature, 41, 209–210. doi:10.1038/041207a0

- Leumann, E. (1890b, January). Review. The American Journal of Psychology, 3, 135. doi:10.2307/1411570

- Ley, C. W. (1890). Thought and breathing. Nature, 41, 317. doi:10.1038/041317b0

- Lindberg, D. A. (2005, November–December). Integrative review of research related to meditation, spirituality, and the elderly. Geriatric Nursing (new York, N.Y.), 26(6), 372–377. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2005.09.013.

- Luria, R. A. (1976). The working brain: An introduction to neuropsychology. London: Basic Books, Penguin Books.

- Malcolmson, J. G. (1838). The man buried alive for a month in India. Lancet. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(02)95648-5/fulltext doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)95648-5

- Manno, F. A. M. (2009, July). Pupillometry in mice: Sex and strain-dependent phenotypes of pupillary functioning. Optometry and Vision Science : Official Publication of the American Academy of Optometry, 86(7), 895–899. doi:10.1097/opx.0b013e3181adfde9

- Manno, F. A. M. (2016). Investigating the demography of India with a structural break test. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 773. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0720-8

- Manno, F. A. M., & Lau, C. (2018b, December). The pineal gland of the shrew (Blarina brevicauda and Blarina carolinensis): A light and electron microscopic study of pinealocytes. Cell and Tissue Research, 374(3), 595–605. doi:10.1007/s00441-018-2897-8

- Manno, F. A. M., Lively, M. B., Manno, S. H., Cheng, S. H., & Lau, C. (2018a, October). Health risk communication message comprehension is influenced by image inclusion. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 41(4), 157–165. doi:10.1080/17453054.2018.1480321

- Manno, F. A. M., Manno, S. H. C., Ahmed, I., Liu, Y., Cheng, S. H., & Lau, C. (2018). One Patient, two patient, three patient, four-when patients are counted, but not accounted for: Pseudoreplication in medicine. 9th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME). doi:10.1109/itme.2018.00065

- Mental Activity in Relation to Pulse and Respiration. (1889). Science, 14, 347–348. doi:10.1126/science.ns-14.355.347