?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Work engagement is a state in which workers show high levels of vigor, dedication, and absorption to and in their work and have been associated with several positive life outcomes. Job crafting describes a set of pro-active behaviors in which individuals alter their work behaviors and environments. It is thought increased job crafting may be associated with increased work engagement. In order to estimate the effect of job crafting on work engagement and control for reverse causation, we performed a random-effects meta-analysis focused on repeated data designs (e.g., longitudinal, daily diary, RCT). We found a considerable positive association between job crafting and later work engagement (standardized effect size of d = 0.37, 95%CI = [0.16, 0.58]). We conclude the paper with a general discussion of the state of job crafting research, limitations, and a call for large randomized controlled trial interventions.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

A sense of engagement at work is something that most employees desire. A possible means to attaining that may involve what has come to be called job-crafting. Job crafting is an approach by which employees, or anyone working, can intentionally structure their activities, thoughts, understanding, and interactions to bring about more efficient work, better relationships, and a deeper sense of meaning. It is an activity that one can costlessly carry out oneself. It is a bottom-up approach that can be carried out with just about any type of work or task or job, at any level. Evidence from numerous studies now indicates that those who practice job crafting are, over time, more likely develop a greater sense of engagement at work. Further development of easy, fast, simple-to-use tools to guide people through the job-crafting process could be of tremendous benefit and facilitate a greater sense of work engagement.

We spend a considerable portion of our lives at work and doing work. How we go about doing our work and our state of mind at work (e.g., our relationship to work) may have an impact on our health, well-being, and ultimately our flourishing (VanderWeele, Citation2017). As such, finding and supporting ways whereby individuals could positively improve their work experience may also help improve flourishing.

In the present work, we focused on one widely used outcome measure, work engagement, that has been found to be associated with a variety of positive outcomes such as less burnout and better general health (Halbesleben, Citation2010). Work engagement is defined as the “active, positive work-related state that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption.” (Bakker, Citation2011). It has been argued that all three aspects (vigor, dedication, and absorption) must be present for the state to be work engagement, which is one of the reasons why it differs from other states such as flow or job satisfaction. Work engagement has been associated with increased work-related outcomes such as work performance (Bakker, Citation2011) as well as non-work-related outcomes such as better overall health (Halbesleben, Citation2010). Furthermore, work engagement in many ways appears to be congruent with some of the domains of flourishing beyond the obvious material and financial ones to also include ones such as meaning and purpose (VanderWeele, Citation2017). To quote from Bakker et al. (Citation2011): “In essence, work engagement captures how workers experience their work: as stimulating and energetic and something to which they really want to devote time and effort (the vigour component); as a significant and meaningful pursuit (dedication); and as engrossing and something on which they are fully concentrated (absorption; Bakker et al., Citation2011).”

One possible way to increase work engagement that has been proposed in the literature is job crafting. Job crafting describes behavior that employees, by their own initiative, engage in whereby they alter aspects of their job and work environment (Demerouti, Citation2014). Although jobs come with instructions on what to do, there are still degrees of freedom during the workday. In other words, how an employee allocates their time and energy to do the job is not wholly specified. It is in these degrees of freedom that job crafting as a behavior lives.

Wrzesniewski and Dutton first described and defined job crafting as a set of three behaviors that they argued helped to increase meaning in employees’ lives by providing them—the employees—a means of control (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001). They describe employees who craft their jobs by going beyond what was required of them or outside the confines of their job description. The three ways they described that employees could craft their jobs were structural (or task), social (or relational), and cognitive (or meaning). Employees can structurally craft their jobs by changing how they do their job tasks. Employees can socially craft their jobs by changing how they interact with others (e.g., fellow employees, customers). Employees can cognitively craft their jobs by changing how they view their jobs (e.g., finding new meaning in their work). For example, a janitor could structurally craft their job by changing the order of doing the required cleaning (e.g., what floor of the building to clean first). The same janitor could socially craft their job by changing how they interact with others (e.g., being friendly and personable with others in the building). And they could cognitively craft their job by seeing what they do in a larger perspective. For example, a janitor at a hospital is not just a person who cleans but is an essential element of the hospital functioning well.

Following Wrzesniewski and Dutton, researchers were primarily concerned with how job crafting affected the meaning of work and found that many employees related a greater sense of self, job-satisfaction, and being from their job crafting (Wrzesniewski et al., Citation2013). This line of research hypothesized that workers via their job crafting could increase their person-job fit and thereby increase meaning derived from their work (Berg & Dutton, Citation2013). In addition to meaning, the following decade saw many reports where job crafting was associated with a variety of positive outcomes including work engagement, motivation, health, and job performance (Demerouti, Citation2014). However, the studies in this period often used cross-sectional designs and therefore were not able to provide evidence for causation or rule out reverse causation (Demerouti, Citation2014; VanderWeele et al., Citation2016).

A second avenue of job crafting research was opened when job crafting was reframed in terms of job demands resource (JDR) theory (Tims & Bakker, Citation2010). Tims and Bakker did so in part because there was not yet a validated job crafting scale. These authors were also concerned that the previous language of job crafting was too general and prohibited further quantification.

In short, job demands resource theory combines stress and motivation research and hypothesizes that an employee, during the course of their work, faces certain demands and has access to certain resources (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2014; Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2011). Job demands are parts of a job that require sustained effort (e.g., cognitive or physical effort). It was hypothesized that job demands, through expanded effort, are associated with costs (e.g., cognitive, physical). Job resources cover the same areas as job demands but resources are used to complete a job (or task), reduce demand costs, and/or help to increase an employee’s “person” (e.g., learning). Furthermore, it is theorized that demands may cause health impairments and resources aid motivation.

In 2012, Tims et al. published a scale for job crafting using JDR theory (Tims et al., Citation2012). Tims et al. found that four factors fit their data the best in contrast to the proposed original three divisions. These four factors (often referred to as dimensions) were “(1) increasing structural job resources (i.e., crafting more autonomy, variety, opportunities for development), (2) increasing, social job resources (i.e., crafting more social support, feedback, coaching), (3) increasing challenging job demands (i.e., crafting involvement in new projects), and (4) decreasing hindering job demands (i.e., crafting fewer emotional and cognitive demands).” (Tims et al., Citation2015). Tims et al. (Citation2012) also found that there was a significant correlation between proactive personality and job crafting, but that proactive personality and the four job crafting factors were distinct from each other. It is this scale, or a reduced version of it, that is most often used in the studies that we examine in this meta-analysis.

This reformulation retained the key insight of job crafting: its focus on how a person proactively adjusts aspects of their work environment and their interaction therewith. That is, the person takes it upon themselves to do the crafting; there is no intervention from management or requirement within their ordinary job description to perform these activities (Demerouti, Citation2014). Both formulations of job crafting emphasize this active approach; there is no passive job crafting. For a fuller accounting of this history (see Zhang & Parker, Citation2019).

To summarize, work engagement is associated with improvement in work and non-work related outcomes and, therefore, may likely be associated with dimensions of overall human flourishing. There is evidence in the literature that job crafting could contribute to (or increase) work engagement and as such could potentially provide an avenue to increased flourishing. While the transitive logic of this is straightforward the base relationships must still be proven. One potential issue is that the available evidence of job crafting to work engagement is largely drawn from cross-sectional data, as are the recent meta-analyses (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, Citation2019; Rudolph et al., Citation2017). In order to further investigate the suspected linkage, we aimed to provide stronger evidence that the association between job crafting and work engagement might be causal. In order to do this, we performed a literature search and random effects meta-analysis of job crafting association with work engagement aimed at assessing repeated data designs, such as longitudinal and intervention studies, in order to be able to control for the possibility of reverse causation. We also investigated possible publication bias.

1. Methods

1.1. Literature search

We conducted a literature search using PSYCHinfo. Given that our purpose in this study is to estimate the association between job crafting and work engagement, we limited our search to studies that used some form of repeated data measurements such as longitudinal, daily diary, or randomized controlled trials and that were published in English. We limited our search to the years 2008 to 2019 and to articles published in English. We performed the search the week of 17 June 2019. The first author did article screening and assessment.

1.2. Literature search results

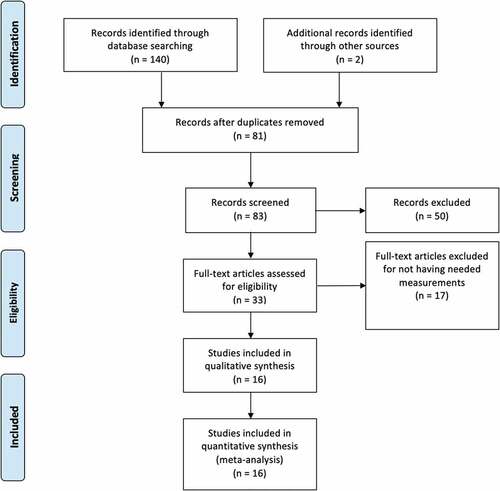

We sought to find articles that detailed studies on the association of job crafting to work engagement that used either longitudinal or RCT methods and were published in English. We performed a literature search using PSYCHInfo databases (See Figure for PRISMA flow chart). First, we used the most restrictive query (“SU job crafting AND SU work engagement”, where SU indicates searching by subject keywords) with a methodology filter set to “longitudinal”, which returned eight results. Finding few studies, we expanded the search by removing the methodology filter. The new query (“SU job crafting AND SU work engagement”) returned 52 results. Finally, we removed the filter for subject keywords (i.e., “SU”) on the query (“job crafting AND work engagement”) and found 80 results.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart. We initially found 140 results from database searches (see Table for queries used). Initial record screening left 33 articles for a full reading that appeared to have used either longitudinal or RCT designs. On a full reading, we excluded 17 articles because the articles did not have the needed measurements. We were left with 16 studies all of which we used for this meta-analysis

Table 1. Search terms used and number of search results

After de-duplication, we were left with 81 articles. We then screened the articles by reading titles, abstracts, and subject keywords to check for methodology used (i.e., articles had to have been either a longitudinal or an RCT study otherwise we removed the article) and to make sure that work engagement was measured. We removed one article because another article was a correction to the original article. We removed another article because the text was in Chinese and could not be read. We removed another 46 articles that did not meet the methodology requirement. We were left with 33 articles that passed the basic screening. We then performed a full-text reading of the remaining articles that led to removing additional 18 articles. These 18 articles were removed because they did have the sought after measurements (i.e., job crafting at baseline and work engagement at follow-up). For example, one study, Dubbelt et al. (Citation2019) could not be used because it measured only two (vigor and dedication) of the three Utrecht work engagement subscales unlike the other studies that included all three areas (i.e., absorption, vigor, and dedication).

During the reading, we found two articles that were cited that met our criteria that were not found in the initial database search (Petrou et al., Citation2016; Vogel et al., Citation2015; both as cited in Petrou et al., Citation2017).

In total, this left 16 articles of which 12 were longitudinal studies and 4 were randomized controlled trials of a job crafting intervention (See Table ).

Table 2. Description of job crafting scales and statistical methods used by article

Job crafting inventories used were generally based upon the scale developed by Tims et al. (Citation2012). See Table for a list of scales used as well as the components measured and reported by the article. Some articles used or reported shortened versions of the scale in which one or more components were omitted or multiple components were collapsed into one. A standard shortening that appeared was one that originates in Petrou et al. (Citation2012). This shortened version had just three factors: seeking resources, seeking challenges, and reducing demands. In other words, Tims et al. (Citation2012) seeking structural and social resources are combined into a single seeking resources factor in this shortened version. Sakuraya et al. (Citation2016) used a scale developed by Sekiguchi et al. (Citation2014). Vogel et al. (Citation2015) used Leana et al. (Citation2009) job crafting scale, which is just a single item inventory. Given the sample size in this meta-analysis and data available from the articles, we did not look at the effects of the scale used.

All studies used in this analysis used the full Utrecht Work Engagement Scale to measure work engagement.

1.3. Data extraction and transformation

The first author did data extraction, entry, and analysis. R code that contains the extracted values, transformations, meta-analyses, secondary analyses, and figure code is available in the supplementary materials.

The research that we found used a variety of statistical methods including structural equation modeling (SEM), ANOVA methods, and multiple-regression (See Table for statistical techniques that each study used as well as the R files in the supplemental materials). In order to be able to use the available research we first needed to transform the various reported results into the same effect size measure. Below, we outline our general data extraction and transformation strategies. R script files available as supplementary materials include a file that contains the values as they appear in the original research as well as the transformations and annotations about what was done (job_crafting_meta_data.R).

For studies that used SEM analyses, we computed the total path coefficient. To do this, we took the product of the path from individual job crafting measures to the outcome variable (i.e., work engagement). We then summed these paths. For individual job crafting measures, we did as above just for those paths that went from the job crafting measure of interest (e.g., seeking social resource) to work engagement.

Of the SEM studies, one study (Bakker & Oerlemans, Citation2019) reported unstandardized SEM coefficients. In order to standardize the total job crafting effect, we standardized the individual paths from the job crafting dimensions to work engagement by multiplying the estimated path coefficient by the ratio of the estimated standard deviation of job crafting divided by the estimated standard deviation of work engagement at the final time point. For secondary analyses looking at individual job crafting dimensions, we standardized by multiplying the path coefficients by the individual estimated job crafting standard deviation divided by the estimated work engagement standard deviation at the final time point (See R code in supplementary materials for exact calculations).

For articles that used regression analyses, the general strategy was to use the standardized regression coefficient, if present. Otherwise, we sought to standardize the reported coefficient as , where

was the regression coefficient of interest and

were the estimated standard deviations of the job crafting components at the first measured time point and work engagement at the last measured time point. As with the unstandardized SEM above, for the total job crafting effect we used the estimated job crafting standard deviation and for the individual dimensions we used the associated individual-estimated standard deviation (See R code in supplemental materials for exact calculations). As with SEM studies, for total job crafting, we summed the standardized effect of the individual job crafting effects. For individual job crafting components, we used just the relevant individual job crafting coefficients.

We needed to estimate beta values for three studies (Mäkikangas, Citation2018; Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b) as they did not report the needed regression coefficients for the variables of interest. We could do this because they did report correlation matrices. To calculate the effect size, we first estimated a beta from the correlation tables as where cov(x,y) is the covariance between job crafting at the first measured time point and work engagement at the final measured time point and var(x) is the variance of job crafting at the first time point. We then computed the standardized effect as with other regression analyses described above.

We then translated these computed effect sizes (d) to r in order to be used in metafor by,

We used r because the reports often lacked the necessary information to be able to use the d directly (Borenstein et al., Citation2009).

1.4. Meta-analytic technique and statistics

We followed standard meta-analysis practices (Borenstein et al., Citation2009; Viechtbauer, Citation2010). All analyses were done in R (v3.5.1). Meta-analyses were done using the metafor library (Viechtbauer, Citation2010). After having calculated the individual effects for each study, we next calculated the effect size data frame using metafor’s escalc function with the measure option set to “ZCOR” and the method set to “REML”. The random effects model was fit using metafor’s rma function with the method option set to “REML”. This produced a random effect model where the resulting units were Fisher Z-transformed correlation coefficients (ZCOR). Results are presented as ZCOR (or zcor in the text) values. These values can be converted to r by and from there can be converted to Cohen’s d by

. As part of the meta-analysis, we also tested for heterogeneity and report the results.

With data sets, such as the present one where experimental design as well as statistical analysis vary between the underlying studies there is concern that a design or analysis may moderate the findings. In order to check for this, we estimated mixed effects models with several four moderators: time lag (in days), sample size, experiment design, and analysis type. For experimental design, we coded studies as either intervention or not. For analysis type, we coded studies as having used SEM or not.

We estimated the proportion of scientific meaningful effects expected for future studies (Mathur & VanderWeele, Citation2019a). We set the scientific values of interest at d = 0.2 and d = −0.2. We performed these analyses in R using the EValue library (Mathur & VanderWeele, Citation2019a).

We also conducted sensitivity analyses to estimate the magnitude difference in the probability of affirmative studies (those supporting the observed effects) would need to be compared to nonaffirmative studies (those not supporting the observed effect) in order to attenuate the observed effect (Mathur & VanderWeele, Citation2019b). We used the R package PublicationBias in order to do these analyses.

2. Results

We used 15 of the 16 studies that met our criteria for the main meta-analysis because Tims et al. (Citation2013) and Tims et al. (Citation2015) both used the same data set but performed different analyses looking at different outcomes. We decided to use Tims et al. (Citation2013) for analysis because it explicitly looked at work engagement as the outcome whereas in the 2015 article work engagement is on the path to other outcomes in their SEM analysis. Values are presented to the hundredths place unless otherwise required.

2.1. Combined job crafting effect

Meta-analysis was used to estimate the combined total effect of job crafting on work engagement across all job-crafting dimensions reported in the underlying research (e.g., structural resources, social resources, challenging demands, hindering demands). We estimated that job crafting was associated with increased work engagement (See Figure ); zcor = 0.18, SE = 0.05, Z = 3.53, p = 0.004, 95%CI = [0.08, 0.28]). This can be converted to a standardized effect size of d = 0.37 (95%CI = [0.16, 0.58]). There was significant heterogeneity amongst the included studies (τ2 = 0.03 (SE = 0.02), I2 = 90.41%, H2 = 10.43, Q(df = 14) = 120.05, p < 0.001). This is not surprising given the small sample and the variety of methods used (e.g., daily diary, multiple-year panels; See Table ). See Table for total effect of job crafting on work engagement effect sizes, sample sizes, and time lags by article and Table for a summary of results.

Figure 2. Forest plots of random effects meta-analyses for (a) the full model and (b) minus hindering demands. Studies used are listed as first author and date. Reported effect size is Fisher’s Z-transformed correlation coefficient (ZCOR)

We calculated the proportion of studies that we would expect to have effect sizes above d = 0.2 or below d = −0.2. We found that we would expect the proportion of subsequent similar studies with effect sizes d > 0.2 to be 0.46 (95%CI = [0.24, 0.68]) and the proportion of studies with effect sizes d< −0.2 to be 0.02 (95%CI = [0, 0.07]).

Examination of the forest plot (Figure )) showed differences of effects between studies as well as differences in precision between studies. In order to address this, we did a series of secondary analyses.

We estimated mixed-effects models with moderators to check to see if sample size, time lag, experimental design (coded as intervention or not), and analysis method used (coded as SEM or not) had a significant influence. A full interaction model with sample size, time lag, design, and method was not significant (QM(df = 11) = 2.05, p = 1.00). We also estimated models for each moderator individually. The moderators in these models were not significant (Experimental Design: QM(df = 1) = 0.03, p = 0.85; Analysis Method: QM(df = 1) = 0.09, p = 0.77; Time Lag: QM(df = 1) = 2.42, p = 0.12; Sample Size: QM(df = 1) = 1.33, p = 0.25).

We performed sensitivity analyses to estimate the n-fold times that publications in favor of the hypothesis (in this case the observed effect) would need to be published relative to studies not in support of the hypothesis in order to attenuate the observed value to zero (Mathur & VanderWeele, Citation2019b). This value is referred to as the S-Value and in this case was infinite. In other words, the estimate (or lower 95% confidence interval bound of the estimate) could not be made to be equal to or less than zero. Illustrative of this result is the fact that if we assumed that the literature was biased 200 to 1 in favor of affirmative versus nonaffirmative publications being published the resulting effect would still estimate a positive effect with associated confidence intervals above the null (zcor = 0.08, SE = 0.02, p = 0.001, 95%CI = [0.04, 0.12]). Even if one was to meta-analyze only the “non-affirmative” studies (i.e. those that were not “statistically significant” or that were “statistically significant” but with effect sizes in the opposite direction) one would obtain a positive meta-analytic estimate with associated confidence intervals above the null (zcor = 0.05, SE = 0.02, Z = 3.22, p = 0.001, 95%CI = [0.02, 0.08]).

2.2. Total job crafting effect without hindering

When examining the individual articles, we noted that reducing hindering job demands was often negatively correlated with work engagement. As a secondary analysis, we removed the hindering effects from the summed values. This new analysis included eleven articles (Bakker & Oerlemans, Citation2019; Demerouti et al., Citation2015; Harju et al., Citation2016; Kooij et al., Citation2017; Mäkikangas, Citation2018; Petrou et al., Citation2012, Citation2016, Citation2017; Tims et al., Citation2013; Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The estimated effect size was slightly larger (See Figuress ); zcor = 0.21, SE = 0.06, Z = 3.68, p = 0.0002, 95%CI = [0.10, 0.32]). There was significant heterogeneity across the included studies (τ2 = 0.03(SE = 0.02), I2 = 88.92%, H2 = 9.03, Q(df = 10) = 95.27, p < 0.0001]). We estimated the proportion of future similar studies we would expect to have effect sizes above d = 0.2 to be 0.53 (95%CI = [0.27, 0.78]) and for effect sizes d<-0.2 we estimated the proportion to be 0.01 (95%CI = [0, 0.04]).

2.3. Individual job crafting component effects

Apart from the above main effect, we were also interested in if individual dimensions of job crafting were likely to be associated with increased work engagement. Not all studies reported values for each of the individual dimensions that were measured (i.e., either from Tims et al. (Citation2012) four factors or Petrou et al. (Citation2012) three factors). Some studies used only a single total job crafting value for analysis. Other studies may have used individual dimensions but did not report values for statistically non-significant results (i.e., those with a p-value greater than 0.05). Due to these issues, we estimated only random effects meta-analytic point estimates and confidence intervals.

For increasing structural resources (six studies: Bakker & Oerlemans, Citation2019; Mäkikangas, Citation2018; Petrou et al., Citation2017; Tims et al., Citation2013; Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b) we estimated a positive association (See Figure ); zcor = 0.18, SE = 0.05, Z = 3.66, p = 0.0003, 95%CI = [0.08, 0.28]).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis results of job crafting resource components. (a) Structural Resources. (b) Social Resources. Studies used are listed as first author and date. Reported effect size is Fisher’s Z-transformed correlation coefficient (ZCOR)

For increasing social resources (six studies: Bakker & Oerlemans, Citation2019; Mäkikangas, Citation2018; Petrou et al., Citation2017; Tims et al., Citation2013; Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b) we estimated a positive association with work engagement (See Figuress ); zcor = 0.10, SE = 0.04, Z = 2.59, p = 0.01, 95%CI = [0.03, 0.18]).

For Increasing challenging demands (eight studies: Demerouti et al., Citation2015; Harju et al., Citation2016; Mäkikangas, Citation2018; Petrou et al., Citation2017, Citation2012; Tims et al., Citation2013; Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b) we estimated a positive association (See Figure ); zcor = 0.05, SE = 0.02, Z = 2.45, p = 0.01, 95%CI = [0.01, 0.08]).

Figure 4. Meta-analysis results of job crafting demands components. (a) Challenging Demands. (b) Hindering Demands. Studies used are listed as first author and date. Reported effect size is Fisher’s Z-transformed correlation coefficient (ZCOR)

For decreasing hindering demands (six studies: Bakker & Oerlemans, Citation2019; Demerouti et al., Citation2015; Mäkikangas, Citation2018; Petrou et al., Citation2016; Tims et al., Citation2015; Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017b) we estimated a negative association with an upper CI that included the null of zero (See Figure ); zcor = −0.03, SE = 0.03, Z = −1.10, p = 0.27, 95%CI = [−0.09, 0.03]). For the hindering analysis, it was necessary to use the Tims et al. (Citation2015) because the earlier Tims et al. (Citation2013) of the same data that was used for the above analyses did not report the needed values for the hindering exposure.

3. Discussion

Work presents an opportunity for human flourishing by being both a setting (i.e., the workplace) in which our lives take place as well as an action that we do (i.e., we work). It stands to reason that how we work, and not just the work that we do, could be related to a host of outcomes including work engagement and overall flourishing. In this report, we focused on one outcome known as work engagement, which is a state of vigor, dedication, and absorption with respect to one’s work (Bakker, Citation2011) and has been found to be correlated with desirable outcomes such as less burnout and better general health (Halbesleben, Citation2010). If work engagement is broadly related with a host of positive outcomes, then finding behaviors (as well as interventions) that may improve work engagement is important. To that end, in this report, we looked at job crafting as a proposed means by which individuals could increase their work engagement and perhaps by extension their overall flourishing.

Job crafting is an important set of observations and theories on how persons work and find meaning in their jobs. Wrzesniewski and Dutton (Citation2001) first described how employees crafted their jobs in three general ways (structural, social, and cognitive) in order to create meaning. Since then, there has been over 15 years of research on the topic, but only in the past several years have data beyond cross-sectional studies been done (e.g., longitudinal and intervention studies) that resulted from a reformulation of job crafting in terms of job demands resource theory. Still, the vast majority of the research has been cross-sectional (Demerouti, Citation2014), including two recent meta-analyses that include numerous cross-sectional studies (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, Citation2019; Rudolph et al., Citation2017) and a qualitative review (Lazazzara et al., Citation2019).

In this article, we reported results of a literature search that focused on studies with repeated data (e.g., longitudinal studies, randomized controlled trials). We found 16 articles that matched our criteria of which four were interventions (See Table for list of methodology by study) and performed random effects meta-analyses. We estimated a positive association of total job crafting on work engagement (Figure ); zcor = 0.18, 95%CI = [0.08, 0.28]). For studies with a similar setting, we would expect 46% (0., 95%CI = [24%, 68%]) of them to have an effect size of greater than d = 0.2. The results seemed reasonably robust to potential publication bias.

We performed mixed-effects meta-analysis with sample size, time lag (in days), experimental design (coded as intervention or not), and analysis method (coded as SEM or not) as moderators. Results of a full interaction model as well as four separate models (one for each of the individual moderators) were not statistically significant.

Removing the hindering demands component of job crafting, which was often negatively correlated with work engagement in the underlying articles, increased the effect size estimate as well as widened the confidence intervals (Figure ). This increased uncertainty in the effect could be driven by the differences in the study designs used or by having fewer studies and warrants future research (Table ).

Figure 5. Meta-analysis results. (a) Results of meta-analysis for the full model (Full) and the model without hindering demands (NoHind). (b) Individual job crafting factor results for structural resources (Str), social resources (Soc), challenging demands (Cha), and hindering demands (Hin) factors. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals

We also estimated random effects meta-analytic effects on the four underlying components of the job crafting scale: structural, social, challenging, and hindering (Figure –). Estimates for three of the dimensions (structural, social, challenging) were positive with confidence intervals that did not include the null (Structural: zcor = 0.18, 95%CI = [0.08, 0.28]; Social: zcor = 0.10, 95%CI = [0.03, 0.18]; Challenging: zcor = 0.05, 95%CI = [0.01, 0.08]). The estimate for hindering demands was negative and included the null (zcor = −0.03, 95%CI = [−0.09, 0.03]). This analysis and distinguishing between job crafting dimension relative strength is complicated by the fact that not all studies used and/or reported the same scale and components. We conclude that results are suggestive that the route of action from job crafting to work engagement is primarily driven via social and structural job resource pathways with the possible addition of challenging demands, although with a smaller effect, but that additional research is needed on this question.

The current meta-analysis results and the individual studies point to job crafting influencing work engagement. In particular, it appears that there may be an ordering of effect size from structural to social, and then challenging demands (Figure ). This is important as work engagement is sometimes viewed as an end itself and there is evidence that it is significantly associated with many other positive outcomes such as job performance (Bakker, Citation2011). This is also important as it provides guidance on which aspects of job crafting could be emphasized in future interventions.

Our estimates here do differ from those of a recent meta-analysis (Rudolph et al., Citation2017) that included cross-sectional data whereas we limited our analysis to repeatedly sampled data such as longitudinal and randomized controlled trials. Rudolph et al. (Citation2017) estimate of total job crafting effect on work engagement was d = 1.01 (converted from their original reported value of rc = 0.450), which is almost three times larger than our estimate of d = 0.37. We do find the same pattern of associations between job crafting components and work engagement. Both our estimates and theirs do agree with respect to hindering demands being negatively correlated (rc = −0.09), although our estimate is null. The difference between the magnitude of our estimates may be due to their inclusion of cross-sectional data, which can reflect associations due also to reverse causation (e.g., work engagement causing job crafting) and may thus overestimate true effects. This is a valuable point and reinforces the need for longitudinal and preferably randomized controlled trials in this literature. The difference may also be due to the differing methodologies used in the underlying studies in our current analysis although mixed effect meta-analysis did not detect significant moderators.

A different meta-analysis divided job crafting behavior into promotion-focused crafting (e.g., increasing challenging demands) and prevention-focused crafting (e.g., decreasing hindering demands) (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, Citation2019). The researchers looked at both cross-sectional as well as longitudinal data sets in separate analyses. For the cross-sectional data, the researchers found a significant positive relation between both forms of job crafting and work engagement (SEM coefficients: promotion = 0.28; prevention = −0.12). They also found significant relationships that were much smaller in the longitudinal data set (SEM coefficients: promotion = 0.11; prevention = −0.03). These results, coupled with our present analyses, reinforce the conclusion that the cross-sectional literature has substantially overestimated the effect of job crafting on at least work engagement and perhaps other outcomes too. There is evidence for an effect, but this can only be established more definitively, with reasonable estimates obtained, through more rigorous longitudinal designs.

3.1. Limitations

3.1.1. Studies, study designs, & statistics

We found six interventions in our literature search of which four had the necessary required variables and were included in our analysis.

Two of the four used interventions reported significant results. Van Wingerden et al. (Citation2017a) used an intervention based on the Michigan workbook that took several days to complete. They found an improvement in job crafting behaviors following the interventions (reported as η2 = 0.043 and converted to d = 0.42) as well as an improvement in work engagement (reported as η2 = 0.031 and converted to d = 0.36). Sakuraya et al. (2016) found a significant improvement in job crafting (d = 0.47) and work engagement (d = 0.26). Sakuraya et al. used a shorter intervention (2 sessions of 120 min separated by 2 weeks) than Van Wingerden et al. (Citation2017a). The subject populations were also different between the two groups. Van Wingerden et al. (Citation2017a) looked at teachers while Sakuraya et al. (2016) looked at managers at a private company as well as managers at a private psychiatric hospital in Japan.

There were two additional interventions that we found (Dubbelt et al., Citation2019; Gordon et al., Citation2018) but did not include in the meta-analysis.

Gordon et al. (Citation2018) were not included in the meta-analysis because the intervention designs limited subjects’ ability to freely develop job crafting plans. The intervention consisted of a three-hour workshop that trained subjects on job crafting. The subjects then created a personal job crafting plan that appears to be more constrained than other plans created in other interventions. For example, in study 2 subjects were told that on weeks 1 and 3 of the intervention they were to craft seeking resources. Subjects also received a weekly reminder of their plan. This level of top-down control (detailing type of crafting to be done as well as regular reminds of such) stands in contrast to the bottom-up worker-centric ideal of job crafting. Still, Gordon et al. (Citation2018) did find a significant impact on their job crafting intervention with increased job crafting associated with increased work engagement increased job crafting and work engagement.

Dubbelt et al. (Citation2019) used two of the three subscales of the work engagement measure and was not included for that reason. Dubbelt et al. (Citation2019) also used a workshop style intervention following the aforementioned studies. The researchers found that following the intervention, subjects increased seeking resources behavior and also decreased seeking demands behavior. They also found that it was the increase in seeking resources that accounted for increased work engagement (as measured by two of the three work engagement subscales).

The difference in intervention results could be due to any number of factors that differ across studies such as different subject populations, sampling sizes, or specific intervention techniques (e.g., Gordon et al. (Citation2018) were in weekly contact with subjects). Given our estimated effect size of job crafting on work engagement, the sample sizes would need to be much larger than those that were used in order to detect significant changes. Interventions ought to also incorporate a wider variety of populations in order to tease out any such population effects.

In general, the studies reviewed here, sample sizes varied from a low of 42 (Sakuraya et al., 2016) to a high of 1,630 (Harju et al., Citation2016) and there were generally no power analyses done to determine if the sample sizes used were large enough to detect the hypothesized effects. This may have greatly hindered some of the studies’ results that reported no substantial evidence for the effects of certain job crafting behaviors. This reinforces the need for meta-analysis. Given that our meta-analysis shows that the total job crafting effect is expected to be modest, large sample sizes are needed. There is also a wide variety of time lags used (cf. Figure 6, Table ). More research is needed to estimate the time course of which job crafting interventions might work and the effect of job crafting to work engagement.

Table 3. Total effect of job crafting on work engagement effect sizes, sample sizes, and time lags by article

Table 4. Summary of results

Finally, researchers would sometimes combine the individual job crafting measures into a single variable for analysis. Other times researchers kept the factors separated. There was generally relatively little reasoning as to why either choice was made or how it might have affected the analysis. We recommend based upon our estimates that show differing effects of the individual job crafting dimensions on work engagement that researchers in the future use both a composite score as well as the individual measures and report all results.

3.2. Personality

We found that the job crafting literature generally did not control for personality. There is some evidence in the literature that personality may be correlated with job crafting (Bell & Njoli, Citation2016; Randall et al., Citation2014). In one study, Bipp and Demerouti (Citation2015) found that those who scored high in approach temperament sought more resources and challenges and less demands than those who scored high in avoidance temperament. In a recent meta-analysis, Rudolph et al. (Citation2017) also estimated that there were positive correlations between the big five personality dimensions and job crafting behaviors. There is also evidence that personality may be related to work engagement (Janssens et al., Citation2019).

Given that job crafting may be viewed as a proactive behavior it would not be surprising if personality was a confounding variable for which control ought to be made. This is true even though Tims et al. (Citation2012) when developing their scale concluded that proactive behavior was a separate factor from their four job crafting factors. Therefore, it could be a concern that the small effects that we did find might be partially attributable to personality instead of job crafting, as such. We urge researchers to account for personality going forward.

3.3. Future directions

Even with these critiques, we found considerable evidence that there is a positive association of job crafting on work engagement.

Researchers and the larger community would be well served by large-scale randomized controlled trials of interventions to promote job crafting, which would provide the proper experimental design to test if job crafting can be manipulated and if so in what conditions and with what “dosage”. Furthermore, trials would provide business leaders and policy-makers confidence in this behavior and interventions. There are already published interventions available including a workbook from the initial theorists (http://positiveorgs.bus.umich.edu/cpo-tools/job-crafting-exercise/), which was used in two interventions (Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

The interventions that were used all were based upon a workshop model that is costly in terms of resources and time. It is known that interventions that merely require the subject to reflect on and write down reflections relating to the outcome variable are quite successful. For example, interventions meant to increase gratitude have the subject reflect on and write down things for which they are grateful for a certain number of days (Cunha et al., Citation2019). We see no reason that a shorter intervention similar to that used for gratitude could not be implemented with job crafting. If such an intervention was to be shown to be effective, then the cost barrier for implementing job crafting would be significantly reduced.

While we looked at work engagement here and job crafting from a JDR perspective, this is perhaps some distance from Wrzesniewski and Dutton (Citation2001) original conception of job crafting as everyday behavior concerning meaning (Demerouti, Citation2014) and overall human flourishing. There may need to be a new synthesis of the JDR longitudinal studies and the original goals as well as possible extensions into human flourishing in general. Indeed, there is only one study that we found that was longitudinal and looked at meaning and which showed a possible positive relationship (Tims et al., Citation2016). There was also only one study, which we were not able to include, that presented a scale closer to the original conceptualization (Rofcanin et al., Citation2019), which found that relational job crafting was significantly related to work engagement.

Work is of course a very common human phenomenon and, given the relative accessibility of job crafting, its potential for enhancing the work experience for a substantial portion of society is very considerable indeed. The evidence suggested here indicates that large randomized trials to evaluate specific job crafting interventions would be worthwhile. If these trials were able to show that job crafting could increase work engagement, then perhaps it could a potent tool in the effort to improve work engagement and promote human flourishing.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Donald E. Frederick

Donald E. Frederick is an Associate and former post-doctoral fellow at the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science. Tyler J. VanderWeele is the John L. Loeb and Frances Lehman Loeb Professor of Epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Director of the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science.

References

- Bakker, A. B. (2011). An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 265–19. http://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411414534

- Bakker, A. B., Albrecht, S. L., & Leiter, M. P. (2011). Key questions regarding work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 4–28. 10.1080/1359432X.2010.485352

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In Wellbeing, C.L. Cooper (Ed.). http://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell019

- Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. (2019). Daily job crafting and momentary work engagement: A self-determination and self-regulation perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 417–430. 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.005

- Bell, C., & Njoli, N. (2016). The role of big five factors on predicting job crafting propensities amongst administrative employees in a South African tertiary institution. Sa Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(1), 11. http://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v14i1.702

- Berg, J. M., & Dutton, J. E. (2013). Purpose and meaning in the workplace, B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger Eds. American Psychological Association. http://doi.org/10.1037/14183-000

- Bipp, T., & Demerouti, E. (2015). Which employees craft their jobs and how? Basic dimensions of personality and employees’ job crafting behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(4), 631–655. http://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12089

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. http://doi.org/10.1002/9780470743386

- Cunha, L. F., Pellanda, L. C., & Reppold, C. T. (2019). Positive psychology and gratitude interventions: A randomized clinical trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00584

- Demerouti, E. (2014). Design your own job through job crafting. European Psychologist, 19(4), 237–247. http://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000188

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands–resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), 1–9. http://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2015). Productive and counterproductive job crafting: A daily diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 457–469. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0039002

- Dubbelt, L., Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2019). The value of job crafting for work engagement, task performance, and career satisfaction: Longitudinal and quasi-experimental evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 300–314. 10.1080/1359432X.2019.1576632

- Gordon, H. J., Demerouti, E., Le Blanc, P. M., Bakker, A. B., Bipp, T., & Verhagen, M. A. (2018). Individual job redesign: Job crafting interventions in healthcare. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 98–114. 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.002

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter eds, Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (102–117). Psychology Press.

- Harju, L. K., Hakanen, J. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). Can job crafting reduce job boredom and increase work engagement? A three-year cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95-96, 11–20. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.07.001

- Janssens, H., De Zutter, P., Geens, T., Vogt, G., & Braeckman, L. (2019). Do personality traits determine work engagement? Results from a Belgian study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(1), 29–34. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001458

- Kooij, D. T. A. M., van Woerkom, M., Wilkenloh, J., Dorenbosch, L., & Denissen, J J. A. (2017). Job crafting towards strengths and interests: The effects of a job crafting intervention on person-job fit and the role of age. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(6), 971–981.

- Lazazzara, A., Tims, M., & de Gennaro, D. (2019). The process of reinventing a job: A meta-synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 103267. 10.1016/j.jvb.2019.01.001

- Leana, C., Appelbaum, E., & Shevchuk, I. (2009). Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6), 1169–1192. http://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2009.47084651

- Lichtenthaler, P. W., & Fischbach, A. (2019). A meta-analysis on promotion-and prevention-focused job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 30–50. 10.1080/1359432X.2018.1527767

- Mäkikangas, A. (2018). Job crafting profiles and work engagement: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106, 101–111. 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.01.001

- Mathur, M., & VanderWeele, T. (2019b). Sensitivity analysis for publication bias in meta-analyses. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/s9dp6

- Mathur, M. B., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2019a). New metrics for meta‐analyses of heterogeneous effects. Statistics in Medicine, 2019a(38), 1336–1342. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8057

- Petrou, P., Bakker, A. B., & van den Heuvel, M. (2017). Weekly job crafting and leisure crafting: Implications for meaning-making and work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(2), 129–152. http://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12160

- Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1120–1141. http://doi.org/10.1002/job.1783

- Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). Crafting the Change: The Role of Employee Job Crafting Behaviors for Successful Organizational Change. Journal of Management, February 18, 1–27. http://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315624961

- Randall, R., Houdmont, J., Kerr, R., Wilson, K., & Addley, K. (2014). The links between the “Big Five” personality traits and job crafting. In Proceedings of the 11th European academy of occupational health psychology conference: looking at the past - planning for the future: Capitalizing on OHP multidisciplinarity. EAOHP. http://uir.ulster.ac.uk/29368/

- Rofcanin, Y., Bakker, A. B., Berber, A., Gölgeci, I., & Las Heras, M. (2019). Relational job crafting: Exploring the role of employee motives with a weekly diary study. Human Relations, 72(4), 859–886. 10.1177/0018726718779121

- Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138. http://doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2017.05.008

- Sakuraya, A., Shimazu, A., Imamura, K., Namba, K., & Kawakami, N. (2016). Effects of a job crafting intervention program on work engagement among japanese employees: a pretest-posttest study. Bmc Psychology, 4. doi: 10.1186/s40359-016-0157-9

- Sekiguchi, T., Jie, L., & Hosomi, M. (2014). Determinants of job crafting among part-time and full-time employees in Japan: a relational perspective. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/osk/wpaper/1426.html.

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1–9. http://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 230–240. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0032141

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2015). Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 914–928. http://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.969245

- Tims, M., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Job crafting and its relationships with person–job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 44–53. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.007

- van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2017a). Fostering employee well-being via a job crafting intervention. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 164–174. http://doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2017.03.008

- van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2017b). The longitudinal impact of a job crafting intervention. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(1), 107–119. http://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1224233

- Van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2015). The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Human Resource Management, 56(1), 51–67 n/a-n/a http://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21758.

- VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 114(31), 8148–8156. 10.1073/pnas.1702996114

- VanderWeele, T. J., Jackson, J. W., & Li, S. (2016). Causal inference and longitudinal data: A case study of religion and mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(11), 1457–1466. 10.1007/s00127-016-1281-9

- Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–48. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v36/i03/

- Vogel, R., Rodell, J. B., & Lynch, J. (2015). Engaged and productive misfits: How job crafting and leisure activity mitigate the negative effects of value incongruence. Academy of Management Journal, 59(5), 1561–1584. http://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0850

- Vogt, K., Hakanen, J. J., Brauchli, R., Jenny, G. J., & Bauer, G. F. (2016). The consequences of job crafting: A three-wave study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3), 353–362. http://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1072170

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. http://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2001.4378011

- Wrzesniewski, A., LoBuglio, N., Dutton, J. E., & Berg, J. M. (2013). Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. 281–302. http://doi.org/10.1108/S2046-410X(2013)0000001015

- Zhang, F., & Parker, S. K. (2019). Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 126–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2332