Abstract

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by intense emotions, self-harm, unstable self-image, and risky behaviors, which impede wellness and interfere with occupational participation. However, literature on occupational participation of people with BPD is scarce and has mostly focused on women. This study explores and elucidates intersections of occupational participation and BPD in a sample of mostly male veterans in order to identify potential ways occupational therapists and other health professionals can support wellbeing for this population. Grounded theory analysis was conducted on data collected using the Indiana Psychiatric Illness Interview (IPII), a semi-structured interview designed to elicit illness personal narratives. Analysis yielded three main themes—influencing environment, internal experience, and occupation—and several subthemes including being abused, arising problems, feeling neglected, feeling victimized, escape, self-segregating, positive change, participating/engaging, and substance abuse. Occupations both influenced and were influenced by the environment and internal experiences. Environments appeared to influence internal experience, but internal experiences did not influence environments directly. Rather, internal experiences impacted a person’s occupations which, in turn, impacted their environments. Participants’ occupational lives revealed, as expected, several subthemes depicting negative and/or isolating experiences. However, participants’ occupations directly impacted both their environmental contexts and internal experiences, suggesting occupational performance may be a powerful mechanism of change for this population. Findings offer promise that occupational therapists could facilitate health-promoting occupational participation which, in turn, may result in more positive and health-promoting environments and internal experiences.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper explores the occupational lives of people with borderline personality disorder. Participants were mostly male veterans, many who had additional mental health diagnoses and/or substance abuse. We found that occupations, which are defined as meaningful activities, can shape people’s internal felt experiences and can also shape people’s environments. For this reason, occupational therapy may be of critical importance to help people with borderline personality disorder reshape their lives in ways that can support wellness.

1. Introduction

The American Occupational Therapy Association defines “occupations” as meaningful life activities that provide sources of enjoyment and motivation; they shape a person’s roles, habits, routines, and identity, and are essential to human health and wellbeing. (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2014). Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a complex diagnosis that lacks a simple definition (Gagnon, Citation2017), but has been characterized by several symptoms that disrupt, alter, or interfere with occupational participation, such as fear of abandonment, unstable relationships, suicidal thoughts and behavior, poor self-image and self-esteem, and marked impulsivity (National Alliance on Mental Illness, Citation2017). Symptoms can begin early in life, and continue to manifest over time (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Symptoms such as fear and poor self-esteem may prevent people from engaging in occupations, resulting in occupational deprivation (Whiteford, Citation2000). Symptoms such as impulsivity may manifest as substance misuse, self-harm behaviors, and/or other problematic occupations (Wasmuth et al., Citation2014).

It is well known that interrupted or altered participation in occupations can have devastating consequences for health and wellness (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2014). But despite the fact that symptoms of BPD are known to impact occupational participation, literature on the occupational lives of people with BPD is lacking, indicating a critical need for more knowledge in this area. Moreover, literature on BPD consists of samples of mostly women. Thus, a better understanding of the occupational lives of men with BPD is needed. Research on how men with BPD construct and experience their occupational lives as well as how their BPD symptoms influence and are influenced by occupational participation is needed to inform occupational therapists and other health-care providers on how to most effectively support the health of this population. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to explore and elucidate intersections of occupational participation and BPD in a sample of mostly men to provide insight into how health-supporting occupational participation may be facilitated. Our specific objectives were to (1) pinpoint ways in which occupations are compromised by BPD; (2) elucidate ways in which aspects of BPD become occupations for individuals; and (3) articulate key areas in which occupational therapists could support health for people with BPD, based on information from objectives one and two.

This study will review the literature on the diagnosis of BPD and common comorbidities, interventions for BPD (including literature related to occupation and/or occupational therapy, and literature addressing the observed gender disparity within BPD research). Following the literature review, we detail our data collection and analysis methodology, present resulting themes, and discuss those themes as they apply to current clinical practice.

2. Literature review

In the 1970s, BPD was distinguished as its own diagnosis and listed in the DSM-III. However, the validity of the diagnosis was questioned due to how similar it was to other mental health illnesses such as depression and schizophrenia. In response, numerous studies were published in the 1980s that began to distinguish BPD from other mental health disorders, particularly schizophrenia (Gunderson, Citation2009).

BPD and schizophrenia may both relate to childhood trauma and emotional abuse, and both disorders have been characterized by a lack of motivation and emotional regulation which interfere with meaningful occupational engagement (Reitan, Citation2013). A qualitative study by Pearse et al. (Citation2014) examined psychotic symptoms of BPD. Twenty-four of the 30 participants reported experiencing psychotic symptoms at some point in their lifetimes, 18 of which were unrelated to other comorbid disorders. Of these 18, auditory hallucinations were the most common, experienced by 15 participants. Visual hallucinations, delusions, tactile hallucinations, and olfactory hallucinations were also reported but less common. Regarding auditory hallucinations, most voices were reportedly negative and experienced as an internal struggle. While both BPD and schizophrenia can present with hallucinations and paranoia, Kingdon et al. (Citation2010) suggests that people with schizophrenia experience more frequent hallucinations. Both diagnoses can affect a person’s sense of self and increase dissociative and emotionally withdrawn actions, but studies indicate these symptoms are often more pronounced in people with schizophrenia, and that hallucinations are more agonizing and intrusive in people with schizophrenia than in those with BPD (Reitan, Citation2013).

Literature suggests that levels of reported childhood trauma are notably high in people with BPD (Kingdon et al., Citation2010). Those with BPD are also 40 to 50 times more likely to attempt suicide than the general population (Stone, Citation2016). In addition, self-harm is common in people with BPD (Rossouw & Fonagy, Citation2012; Stone, Citation2016). The DSM-5 lists nine criteria for BPD; a person must meet five to be diagnosed. The criteria include

1. Frantic efforts to avoid real or imaginative abandonment

2. A pattern of unstable or intense interpersonal relationships that fluctuate between extremes of idealization and devaluation

3. Identity disturbance: persistently unstable self-image or sense of self

4. Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging

5. Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, threats, or self-mutilating behavior

6. Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood

7. Chronic feeling of emptiness

8. Inappropriate, intense anger, and inability to control it

9. Short, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013, p. 663)

Most studies have found that by the time a person is in their thirties, the symptoms of BPD have decreased with or without intervention. However, longitudinal studies of people with BPD are rare; comparative intervention studies at a given point in time are much more prevalent in the literature (Stone, Citation2016).

2.1. Comorbidity

Borderline personality disorder is most commonly found to have comorbidity with Axis I disorders, including mood disorders, substance use disorders, adjustment disorders, dissociative disorders, eating disorders, and other behavioral and emotional disorders that develop in childhood and adolescence (Kaess et al., Citation2012). The most common comorbidities included depression and anxiety (Tomko et al., Citation2014). Comorbid diagnoses with Axis II disorders such as avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders are also common (Kaess et al., Citation2012).

According to Frías and Palma (Citation2014), people with borderline personality disorder are significantly more likely to also have a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than the general population. A comorbid diagnosis of BPD and PTSD amplifies psychopathological and psychosocial impairments seen in BPD alone. Some have suggested BPD and PTSD comorbidity is a manifestation of two results of a common childhood trauma (Frías & Palma, Citation2014). Boritz et al. (Citation2016) found that patients with comorbid BPD and PTSD reported higher psychological distress before and after treatment compared to those with a diagnosis of BPD alone.

Rates of BPD co-occurring with substance use disorder (SUD) are estimated to be as high as 65% (Pennay et al., Citation2011). A ten-year longitudinal study (Zanarini et al., Citation2011) found that substance abuse prevalence among people with BPD is about five times that of the general population. Moreover, people with BPD were 65% more likely to report drug dependence than people with an Axis II disorder. However, more than 90% of people with BPD and substance abuse experienced remission ten years later. This study also found that new drug and alcohol abuse in patients with BPD was uncommon (Zanarini et al., Citation2011). One could speculate that substance misuse and BPD arise together for some, or that substance misuse may precede BPD as a means of coping with childhood trauma and adversity, and could impact emotion regulation and development of coping skills, thus contributing to the development of BPD symptoms.

2.2. Interventions for borderline personality disorder

Studies suggest that, while many medications have been developed to address BPD symptoms, medication alone does not help long-term recovery and should be bolstered with other interventions specifically tailored to the person and his or her symptoms (Borderline Personality Disorder, Citation2016). Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) focuses on the relationship between the person and health-care professional through patient-centered skill-building, psychotherapy and a team approach (Bendics et al., Citation2012). It also includes education on balancing life changes, and is typically performed over a one-year period (O’Connell & Dowling, Citation2014). Dialectical behavioral therapy has been suggested to improve attitudes toward daily experiences (Bendics et al., Citation2012). King et al. (Citation2019) found DBT increased positive affect and decreased negative affect in patients with BPD both within and across DBT sessions in a sample of 73. Wetterborg et al. (Citation2018) point out that while effective treatments for women with BPD have been developed, little research has examined effective treatments for men. In their study of 30 men with BPD and antisocial behavior, DBT significantly reduced self-harm, verbal and physical aggression, and criminal offending rates, suggesting the need for future, more rigorous studies of DBT for men with BPD.

Similar to DBT, emotional regulation training (ERT) consists of learning techniques to control strong emotions by way of healthy coping skills. Limited research suggests ERT may facilitate long-term change in people with BPD (Schuppert et al., Citation2012). Other studies suggest metacognitive training for people with BPD results in improvements in self-confidence, empathy, taking others’ perspectives, and coping (Schilling et al., Citation2015; Citation2018).

2.3. Occupations and borderline personality disorder

Occupational therapy emphasizes the importance of occupational balance. Occupational therapy is defined as “the therapeutic use of everyday life activities (occupations) with individuals or groups for the purpose of enhancing or enabling participation in roles, habits, and routines in home, school, workplace, community, and other settings,” (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2014). Occupation refers to any meaningful activity, not just the person’s vocation. Few studies have examined relationships between occupations and BPD. One study examined the occupation of sleep in patients with BPD, finding people with BPD often have sleep difficulties and/or used sleep to cope with symptoms (Wood et al., Citation2015). Although sleep is an important occupation for everyone (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2014), symptoms of BPD can be amplified by lack of sleep, making it a high priority for those with a diagnosis of BPD. This study found that establishing routines was helpful in developing healthy sleep patterns. However, findings were drawn from a very small sample and are not necessarily generalizable to the wider BPD population (Wood et al., Citation2015).

Another study found that women with BPD had few organized daily occupations (Falklof & Haglund, Citation2010). While this study also had a very small sample, it may offer preliminary insight into the occupational lives of those with BPD. For example, when discussing their lives, participants in this study were much more likely to give examples of incompetence in performance than they were competence in performance. Participants reported that goal setting was viewed negatively because of prior failures in accomplishing desired occupations and/or meeting goals. Participants reported frequently feeling shame and unhappiness when trying to manage their occupational lives (Falklof & Haglund, Citation2010). Overall, this study emphasized that women with BPD had difficulty adapting to daily life and organizing daily occupational routines (Falklof & Haglund, Citation2010).

2.4. Gender and BPD

The DSM-5 suggests that only 25% of those with a BPD diagnosis are men (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013, p. 66). However, some have suggested a tendency to diagnose more women with BPD than men may indicate a gender bias among clinicians (Sansone & Sansone, Citation2011). The gender difference in diagnosis, others suggest, may also be due to women being more likely to seek help regarding psychological needs (Skodol & Bender, Citation2003). Regardless, little is known about the experiences of men with BPD. Most empirical studies of BPD interventions have a primarily female sample. However, several studies have examined gender differences in people with BPD using a more gender-diverse sample. Silberschmidt et al. (Citation2015) examined both self-reported and clinical measures of BPD symptomology in a sample of 720 people with BPD, 211 of which were men, to extend knowledge about gender differences. They found that many gender differences present in the general population were absent in people with BPD, including no differences in aggression, suicidality, substance abuse, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder, and attenuated differences in PTSD and major depression. Busch et al. (Citation2016) used the Multi-source Assessment of Personality Pathology (MAPP) to assess prevalence and symptom severity of BPD across gender. They found men with BPD to be just as prevalent as women despite the disparity of research on men with BPD. Regarding self-report symptomology data, men reported higher BPD symptomology and severity, indicating a difference in gender perspectives regarding BPD. However, informant reports did not differ between men and women, suggesting symptomology to be similar across gender despite differences in gender perspectives. With increasing visibility of transgender and gender-diverse people, more research is also needed on the prevalence and symptomology within this population, particularly because stigma-related stressors experienced by gender minorities may contribute to behaviors or symptoms that could mirror BPD diagnostic criteria (Goldhammer et al., Citation2019).

3. Methodology

This study used existing data from a larger study looking at metacognition and function in people with BPD. All procedures were approved by Indiana University and Veterans Affairs institutional review boards. Participants for this larger study were recruited via clinician referral. To be included in this study, participants had to be patients at the VA Medical center, receiving services for BPD. Patients under 18 and pregnant women were excluded.

3.1. Participant characteristics

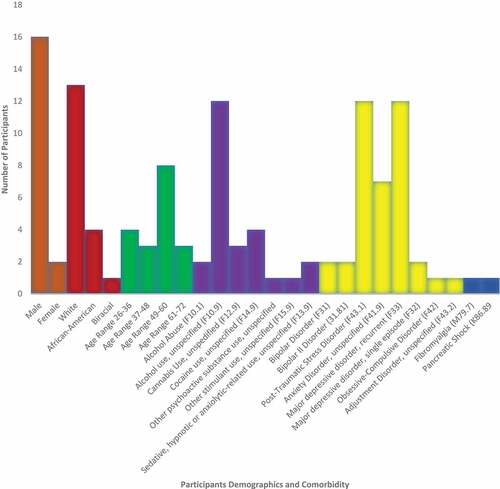

Participant ages ranged from 26 to 67 and included 18 mostly male veterans (2 women and 16 men). The ethnicities of the participants are as follows: 72% Caucasian, 22% African American, and 6% Interracial. Substance use or misuse was common among participations. Two (11.11%) had a diagnosis of alcohol abuse, and 12 (66.67%) had documented alcohol use. Three (16.67%) had a diagnosis of cannabis use, 4 (22.22%) had a diagnosis of cocaine use, 1 (5.56%) had documented benzodiazepine use, 1 (5.56%) had documented methamphetamine use, and 1 (5.56%) had documented opioid use. Of the 18 participants, all but one (94.44%) had an Axis I diagnosis. Two (11.11%) had bipolar disorder and 2 (11.11%) had bipolar II disorder. Twelve participants (66.66%) had PTSD, 7 (38.89%) had an anxiety disorder, 12 (66.67%) had a major depressive disorder, and 2 (11.11%) had been diagnosed as having a major depressive episode. One (5.56%) had obsessive-compulsive disorder, and 1 (5.56%) had adjustment disorder. Four participants (22.22%) also had Axis III disorders including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (two participants), pancreatic shock (one participant), and fibromyalgia (one participant). Participant characteristics are listed in Figure .

3.2. Measures

Data were collected using the Indiana Psychiatric Illness Interview (IPII), a semi-structured interview designed to elicit illness narratives (IPII; Lysaker & Lysaker, Citation2002). The IPII consists of four sections that take between 30 and 60 minutes to complete. The first section is a general free narrative. This section allows the individual to discuss their life experiences openly and helps establish rapport with the interviewer. The second section is an illness narrative. This section takes a deeper look into the individual’s perceptions of his or her mental illness. The third section evaluates the individual’s perception of the illnesses’ control on his or her life and how well he or she manages illness. The fourth section examines the individual’s thoughts about the future and aims to see what will remain the same and what will change as a result of changing interpersonal and psychological functioning (Roe et al., Citation2008).

3.3. Research design

This study utilized a grounded theory approach. Grounded theory is an inductive approach that can be useful when existing theories or knowledge on a topic are lacking or preventing new insight. Given the limited knowledge on the occupational lives of people with BPD, grounded theory may be helpful for discovering new information in this area. Furthermore, grounded theory has been described as particularly useful for researchers studying self, identity, and meaning (Charmaz & McMullen, Citation2011). The grounded theory process involves using rich qualitative data to identify themes; the coding process begins very generally and then gradually becomes increasingly precise (Charmaz, Citation2014). Constructivist grounded theory rejects the idea of “neutral observer” and instead emphasizes that researchers are situated in sociopolitical contexts that shape their perspectives and understandings of data. Thus, grounded theory requires researchers to engage in reflexivity through the use of memos (informal notes about observations, perspectives of the researcher, and nuanced details about the context of the interview conversation) and data checking throughout the analytic process.

The research team consisted of four doctoral occupational therapy students, their faculty research advisor, and a psychologist/researcher. The faculty advisor is a licensed/registered occupational therapist with expertise in mental health and grounded theory analysis. This study was completed in partial fulfillment of an occupational therapy doctoral capstone project.

3.4. Data analysis

Dedoose Version 8.0.35 (Citation2018) version 8.0.35 was used for data analysis. Eighteen transcribed and de-identified interviews of veterans with BPD were analyzed by the research team using the following steps outlined by Charmaz (Citation2014).

3.4.1. Initial coding

The research team first performed line-by-line coding on the first page of one transcript as a group. This involved reading each line of the transcript and assigning a code to each meaningful text unit. This process allows researchers to stay open to the data and prevents any themes from being overlooked (Charmaz, Citation2014). Memos were taken to note the researchers’ thoughts during the coding process. After performing line-by-line coding on each page of the first transcript as a group, the researchers established an initial codebook to use when looking at further transcripts, with the knowledge that codes would be continually edited throughout the data analysis process. The initial codebook was established by examining the line-by-line codes and establishing themes based on these codes.

3.4.2. Focused coding

During this stage, significant codes identified in initial coding are applied to large amounts of data in order to determine the accuracy of the codes identified. New ideas continue to arise in this process and the codes in this stage are defined as necessary (Charmaz, Citation2014). As the codes are refined, they are applied to previously coded data. To complete focused coding, codes and deidentified transcripts were entered into Dedoose (version 8.0.35) and the research team split into two groups. Using the codebook, groups coded five transcripts total, coming together after each transcript to discuss the codes as an entire group as well as memos the researchers wrote during the coding process. During this process, each team read the codes they used for a specific portion of text, and upon agreeing on a code unanimously, it was added to a final version of the transcript. Discrepancies were resolved by consulting with the faculty mentor member of the research team.

3.4.3. Axial coding

The third step of grounded theory coding is axial coding, which is described as a way of sorting and synthesizing data (Charmaz, Citation2014). Axial coding is used to help researchers answer questions about the data and begin to understand relationships among the themes (Charmaz, Citation2014). The research team reviewed all of the coded transcripts in pairs, examining the data and memos for each unique code and looking for themes and subthemes within each code. This allowed the researchers to gain a better understanding of each code’s meaning and the ways in which data for each code presented. Researchers looked for similarities and differences in how data for a specific code presented among individual participants.

3.4.4. Theoretical coding

The final coding stage of grounded theory is theoretical coding, which is a means of identifying relationships between the codes and is a step beyond axial coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). The researchers used themes found in focused and axial coding to determine relationships among the main codes. These relationships were then put into a figure in order to visually demonstrate observed relationships. In this stage of the coding process, some codes were combined, moved, or renamed in order to best describe the data. The findings of theoretical coding sculpted the theory derived from this research.

3.4.5. Trustworthiness

Investigator triangulation was used in this study to increase the trustworthiness of findings and methodology. Investigator triangulation involves using two or more researchers in a study to interpret the data in order to minimize biases (Carter et al., Citation2014; Denzin, Citation1973). This study utilized a primary investigator and four secondary investigators to interpret the data and develop themes throughout the research process.

3.5. Findings

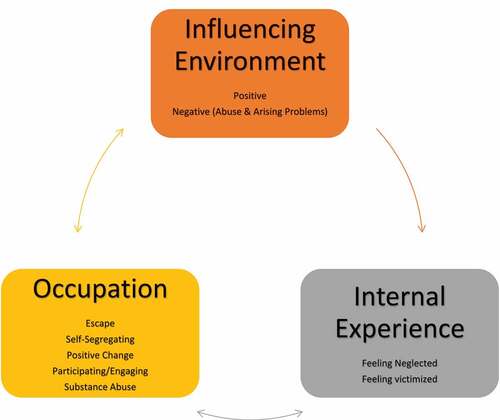

This grounded theory analysis resulted in the following main themes: influencing environment, internal experience, and occupation. Each main theme is accompanied by subthemes: being abused, arising problems, feeling neglected, feeling victimized, escape, self-segregating, positive change, participating/engaging, and substance abuse. These themes can be found in Figure . Below are the descriptions of data contributing to these themes and the resulting theory.

3.6. Themes

3.6.1. Influencing environment

The theme “influencing environment” describes data revealing the positive and negative ways participants’ current lives were shaped by past experiences. Data reflecting a positive environment included references to social environment (family and children), and/or physical home or shelter. For example, one participant noted: “We were kind of living with my grandparents at the time so I remember a kind of stability there. There was always breakfast. There was always kids to play with … there’s toys. It was a good place to live.” This excerpt demonstrates how a positive environment produced “stability” and fulfillment of needs such as food and “kids to play with”. Receiving positive love, attention and help from parents growing up influenced and sometimes counter-acted negative feelings. As one participant recalled:

I didn’t have any confidence anymore and my dad spent every night working with me and because math was his big deal we spent a lot of time with math and science. He was chief of training for the fire department and they have to do a lot of math and he would bring their tests home and have me do some of the problems there. He had a way of guiding me to answers … not giving me answers but being a true tutor that helps you see the path to get there. … He would get really excited, he would say, “oh, Wow! Some of the guys in the class weren’t even able to get this one!” So … probably for that … you know a lot of those reasons that I enjoyed the math and science tremendously.

Negative environmental influences described problematic family histories leading to current life struggles, or negative military experiences. One participant stated,

I remember when I was 10 and they picked my sister up basically for prostitution … the judge had ordered her to seek psychiatric counseling and the center she went to, they got ahold of my parents and said they wanted to see the whole family for counseling and my mom and dad refused, and I think partly it was because my mom was afraid that the abuse that she had … I don’t know, I mean it was odd, I don’t remember my sisters going through what I did, but they could have had it but, I don’t remember … there was enough abuse by the time I was 10 that she didn’t want anyone going to the counseling talking to anyone about it.

The impact of negative environmental influences is further described in the following subtheme.

3.6.1.1. Being abused

The subtheme “being abused” was used when a participant described some form of physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual abuse, including bullying and being unfairly punished or persecuted. Almost all of the abuse that participants described occurred during childhood, and all abusers were authority figures, except in instances of “bullying.” When a participant described being bullied, it was always by peers. All but one described the bullying as happening in childhood, during their school years. One participant described:

There were a group of like 5 kids that I don’t know why but they were allowed to pick on me every day on the playground and in class. I remember that whoever would sit behind me used to flick my ears when the teacher wasn’t look and they would actually like hit me on the playground and harass me and torment me every day … that happened every day for 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th and nothing was ever done about it and it was odd.

The outlier was an instance of being bullied by other soldiers while in the military. This participant said:

I started getting bullied and like I had never been bullied in my entire life but I really got bullied there. And I couldn’t figure out why I was getting bullied but I’m not someone you bully. I’ve never been someone you bully. I will never confront you head on. I’ll never fight you, I’ll never go to jail for it. I was cornered by four of my peers and, during the assault, I had cigarettes extinguished in my eyes.

The majority of the instances of bullying were manifested through physical bullying, but there were some manifestations of psychological bullying as well through threats, spreading rumors, and being excluded from participating and engaging with peers. This was the case for one participant who tried to join after school curricular activities:

I remember walking in on one of those clubs wanting to join and I got locked out. And it wasn’t like they were being polite locked out it was viciously locked out and that set a tone for me for a long time.

In all instances of bullying, participants felt unwanted by their peers and were afraid to try to connect with peers.

Psychological or emotional abuse, sometimes in the form of neglect, occurred in childhood or adolescence and always involved family members. One of the participants said: “Eleven years old on … even to this day … it’s turned to verbal abuse or criticism, always. Everyone … dad was super critical of everything, especially me and not … never was able to satisfy him … never lived up to any of his expectations.” Another participant described psychological and mental abuse:

And this is when the abuse kinda started. Like I don’t wanna say it was sometimes … it was some sort of physical abuse at that point … He never let us come in the house for dinner. He was like ‘just eat out of the garden, it’s healthier.’ I always thought that was an abusive thing to do, but some people don’t see it that way. He yelled a lot; he was demoralizing; called you fat or worthless or he always for some reason thought I was gonna be gay. He always had that assumption and I just really resent that fact. One time he made us sleep outside for an entire week with just a poncho, and got fed out the back door … things like that.

Multiple participants reported experiencing physical abuse more than once in their life, usually recalling several specific attacks. One participant described:

When I was younger, or at some point, I think somebody tried to suffocate me because now I have issues with plastic bags and making sure that plastic bags are tied up in knots so that no one can accidentally get it put over their head.

While another described: “The discipline being in the form of what would be considered now, beatings. They say I was a mischievous child so I experienced a lot of physical beatings which I was told was a form of love.” One person described the culture of the neighborhood he grew up in as contributing to physical abuse:

A lot of emphasis was placed on who you were as far as your sexual prowess. Very limited worldview … racism played a factor, discrimination played a factor. Also, police brutality played a factor in my life.

Most of the participants who reported sexual abuse expressed these memories as being hazy, almost dreamlike. One participant reported thinking of the abuse every day:

I have memories, real fragmented memories, of being molested by a Priest in church and possibly in the Priest’s home, the rectory. I believe I was in there at least once and obviously I would have been molested if I was in there. I’ve had just a few dreams about that but nothing concrete; nothing, you know, that a specific Priest, or I can’t give a date or anything like that but I know it happened and in fact it’s odd I still think about the Priest almost every day. I think about him and that was a long time ago … so obviously I think something happened that I would still think of him.

In a couple of the instances sexual abusers were military personnel:

While I was waiting for my leg to heal … is when … the guy who had been my trainer when I first got to base … my aircraft trainer had raped me and then … I didn’t think it was a rape because I was racing bicycles … I went to my massage therapist who was also a social worker and she took one look at me and said there’s something wrong … we’re not doing a massage today, we’re going to talk. She was the one that told me I was raped … and I said no I wasn’t because I had all these classes in basic training where they show you someone jumps out from behind the bushes but she got me to understand that it was a rape … and it was four days later and I knew that I couldn’t have any resolution with (inaudible).

One participant was abused by her brother and his brother’s friend:

I was about 11 or 12 and uh … I was forced you know, through threats, to give him oral sex and his friend, too. I was three years younger than him and much weaker than him … he often told me he was going to kill me. I felt he hated me. And everyone wanted me to be like … he was an overachiever.

Another described being molested by a family member and again by a babysitter:

In particular, one guy was a child molester that I unfortunately had the situation of allowing him into our family. He molested me and molested two of my younger sisters. Raped me, had me have sex with other gentleman, and that went on for several years. We thought that there was something wrong with us, of course. We weren’t the only ones going through it, and it wasn’t right, but there was nothing we could do about it. It was not my only time being raped however; I was raped by a babysitter. A female babysitter that was about four years older than I was while my mother was at work. This was between her boyfriends and she taught me certain things about making love with a woman … being raped by two different genders definitely had a bearing on my sexual and love life.

A commonality among participants being abused, as evident in the above excerpts, was a sense of disempowerment resulting from a lack of support or ability to fight back or address the problem.

3.6.1.2. Arising problems

Many of the traumatic experiences described in the previous theme were described as contributing to arising problems identified in participants’ adult lives, which occurred in very similar ways across multiple participants’ transcripts. The main problems seen were (1) early or rushed marriages which ended in divorce and legal trouble (e.g. burglary, assault, illegal firearms); (2) living unstable lives post-military deployment (e.g. job loss, family troubles, domestic abuse, homelessness); (3) unexpected pregnancies; (4) problematic substance use; (5) unstable relationships and affairs; (6) emotional breakdowns during employment; (7) rising mental illness symptoms (e.g. poor emotional regulation) and associated hospitalizations and doctor visits; and (8) feeling misunderstood or “separate” from others. Often these problems were interrelated, creating a snowball effect of arising problems. Illustrating this, one participant stated:

I signed a piece of paper ending my military career and I still have a couple years left but inevitably I wasn’t allow to stay in past the contract date because I didn’t move to Hawaii … that’s when I started abusing alcohol … and in that one year … I’ve dealt with so much life and death … I lost 100,000 USD dollars … my house, I lost the house that I bought and built … my kids, my wife, my family and … a lot of my family did not understand me.

Another participant stated; “I got my girlfriend pregnant when I was 19 and she was 17, had got married right after she graduated high school. Had a baby, that didn’t work out.” As seen in other transcripts, arising problems were interrelated. Another participant described how his problems arose after returning from the military,

I just was in and out of the hospital, and one of the hospitalizations I met this woman [name]. I divorced [name]. [name] and I left town and went up to [location] … We got married. I got social security disability and got like 25,000 USD in back pay for that and I won a workman’s comp claim and got 70,000 USD for that and we blew a hole through the [inaudible] …

3.6.2. Internal experience

Data comprising “internal experience” detail the thoughts, feelings, and emotions of participants. Although data may in part describe emotional counterparts of the experiences documented in the previous theme, they also reflect the nuances of how participants perceived, interpreted, and internalized events. Participants described feeling neglected and/or victimized.

3.6.2.1. Feeling neglected

All accounts of feeling neglected took place during childhood. Many of the participants did not or could not verbalize reasons they felt neglected, but half stated that they didn’t feel loved:

I think I have memories of actually being in my mother’s womb and things being very chaotic … very disturbing, very uncomfortable. I’ve just recalled feelings of that and when I was a child I felt that my mother never really liked me or wanted me. I never felt a part of the family.

One participant explained:

I never received the attention I should have. I didn’t receive the love I should have. I didn’t receive the accolades I should have. I never received what I feel most children deserve to receive and … trying to compensate today by loving myself where I didn’t receive love … paying attention to myself … listening to myself … being good to myself in those areas that I felt I was shortchanged … and it just seems like the whole family was against me … like I was some type of alien … it was just wild.

3.6.2.2. Feeling victimized

Feelings of victimization arose while at work, in the military, or in school. “Feeling victimized” does not imply that related occurrences were not antagonistic or discriminatory; rather, these data reveal the internal responses to such situations. Similar to data in the previous theme, participants commonly lacked a sense of empowerment to respond effectively to problems. The data comprising this theme enrich data in the theme of “influencing environment” by illustrating not only the problematic events but also the feelings accompanying them and the participants’ lack of power and self-efficacy in these situations. One of the participants discussed how he felt victimized while in school, “I sold out my priesthood ‘cause I went from catholic school to public school ‘cause catholic school flunked me out on purpose.” Another participant described his feelings of victimization in the work setting,

The more they kept telling me you need to start getting things done or you’re going to end up in the bottom 10%, the less I was able to accomplish. Then they put me on a personal improvement plan saying that, “here are the things that you have to do. You have four weeks to do these. If you don’t get them done, we’ll let you go. If you do get them done, we’ll take you off the performance plan. You still have to do all the other work that you’re supposed to be doing right now.” Either one of those would have been full-time. It just … it felt like I got set up … so I got fired from there.

This quote reveals how work-related demands and conditions felt like a personal attack, perhaps seeming unfair or un-accomplishable, and thus the participant felt victimized.

3.6.3. Occupation

The following data, categorized under the theme “occupation,” illustrate the performance patterns of participants and are further delineated by several subthemes. In general, the subtheme “participating and engaging” illustrates the occupations of this study’s participants. Some participants specifically describe new occupational endeavors that provided positive change. Others used occupations as a way to either escape problems (this included instances in which participants escaped through substance use) or to distance themselves from people or circumstances. The latter instances were categorized under the subtheme “self-segregation.”

3.6.3.1. Participating and engaging

Most participants described military involvement as their main occupation. Others described participation in school and work. Notably, many descriptions of participation at school were negative; therefore, most participants did not continue their education. Instead, they either began working or joined the military.

Most participants described engaging in work, not as particularly meaningful but rather, as something to do:

After [location] I came back to [location] and I worked at a correctional facility for maybe two years. I ended up as case manager at the correctional facility. That was 2010. I poured concrete one summer with my good buddy, just really for something to do.

Notably, many of the work experiences were short-lived and participants discussed frequently changing jobs. For example:

I work as an appliance technician and I pretty much liked the job. It was okay. But after a year the guy let me go and I got another job working with the T.V. shop that was adding appliances to their lineup and they hired me to do the appliance technician.

While participants did not describe deriving much meaning from their work, they also did not report non-military work to be a negative experience. Participation in the military, with a few exceptions, was largely reported as troublesome:

I ended up staying in the worst place on God’s green earth. Fort [inaudible] will change anybody. I don’t know how the military has not caught on that we probably shouldn’t leave people out in the middle of nowhere and work them as much as they do and not expect people to come out absolutely bat shit crazy.

As an exception, one participant explained the occupation of being in the military and how it was meaningful and gave purpose:

So when I was 17 I had my mom sign the paper so I could join the Army and I left when I was 18 … I kind of felt like my calling … I think it kind of has to be your calling to do something like that … it’s not something you would do randomly because know you are going to Iraq and Afghanistan so … it was important to me … I did that … I did very well in the military … I went to the board as a staff sergeant when I was 21 … I felt like I was better than most people at what I did, just because it was something that came more naturally to me than other jobs or other skills … it was just my thing … I was good at it.

3.6.3.2. Positive change

All of the instances categorized in this theme described participants’ life changes such as joining the military, quitting the military, getting a growth spurt, and becoming a better student. Many participants joined the military with the goal of changing their lives for the better, and the initial occupational participation of being in the military was experienced as positive: “I went to the army, volunteered to go to desert storm, desert shield. Everything was great while I was there.” One participant experienced a positive change when he quit the army “got out to [location], threw my Army coat in the garbage can, took the first breath of my life.” One participant experienced a break-up and then spent some time participating in new occupations,

I’m back, we broke-up, I was really … I spent the next year really getting my life together, saved up money, bought a new car, and lived in a really tiny house so I could save my money and did a lot of overtime and I just didn’t really have any girls in my life at that time for like a year. I’d go to the gym and like go out with, you know, somebody after we’d worked out or something … but never turned into anything other than just friends.

Most of the participants verbalized that they could, “finally live,” or “life was good,” or “I got my life together” as the reason(s) new occupations fostered positive life changes.

3.6.3.3. Escape

Most participants who described “escape” occupations were physically leaving a bad living situation, whether it was extreme (such as abuse) or mild (not liking the town or neighborhood that he or she lived in). One participant described fleeing to the military after a break up: “She broke up with me and so I joined the AirForce.” The participants who escaped due to not liking the town they lived described their neighborhoods as slum neighborhoods: “From that point on, I thought about getting away from the house, so I did. I enlisted in the marines.” One participant left his neighborhood to “find more opportunities,” and started attending college. However, when people described occupations as a means for escape, many of the occupations people escaped to were short lived, as evidenced by the following quote: “and I got out of there pretty quickly and moved to the big city in [location], which was after I started college … and quit my freshman year.”

3.6.3.4. Substance use

Some participants escaped negative feelings or circumstances through substance use, whereas others used substances as a recreational/leisure occupation. Most of the excerpts categorized in this theme illustrate participants’ efforts to escape negative feelings or experiences via alcohol. These data are accompanied by descriptions of negative consequences of alcohol use. Many also reported marijuana use, but these data reflected routine use without negative consequences or using marijuana to escape. Data frequently illustrated a link between alcohol abuse and the military—particularly negative events that occurred while in the military. One individual highlighted the extent of his alcohol use:

I drank heavily; I was drunk every day in the box. I had a flask on me every time. I drove drunk. I drove tanks drunk. I was a recluse. At this point I didn’t care who I hurted … I wanted to hurt somebody … I was suicidal. I was like ‘please shoot me ‘cause I’m not ever going to kill myself but at the same time I don’t care if someone else does it.’ If I’m going to go down, I’m going down in a blaze of glory … I guess is what they call it. I don’t really call it glory ‘cause it’s not really glory. I’m going down in a blaze, I guess.

This excerpt shows the overall negativity surrounding both military and alcohol use. Another participant discussed the connection between alcohol and suicide: “I was gonna kill myself. I had a gun in my mouth and I was gonna pull the trigger and I was drunk.”

One participant highlighted their use of marijuana as a form of escape:

I got out of the Army in February of this year … as soon as I got out I started smoking pot to numb myself, which it did. It helped, but you can’t function properly as a human when you’re stoned out of your mind … when you have responsibilities and children and things like that … but, it numbed me enough to prolong the pain that I couldn’t handle and it worked for that and I quit smoking in July and I’ve been … I haven’t smoked since that. I’ve had a few incidents with alcohol. One of them, I ended up in the hospital here. I woke up in the ER a few weeks ago because I drank too much and I just woke up here and didn’t know how I got here or anything.

3.6.3.5. Self-segregation

The data suggested that participants used some occupations (or embraced avoidance of occupational participation) to segregate or distance themselves from others or from troubling circumstances. While similar to data describing escape, the data categorized in this theme specifically illuminated how people separated themselves from life and/or other people as a whole, rather than just escaping a specific troubling set of circumstances. For example, one participant discussed how his feelings about people affected his participation in everyday life stating, “Didn’t want to do nothing because I didn’t want to be like everybody else.” Another participant segregated himself by staying in his home, “I didn’t leave my house unless I absolutely had to, meaning I had to be almost completely out of cigarettes and food in order for me to leave my house.” One other participant discusses his purposeful segregation from his family by stating, “My family, is absolutely distanced from me as I could possibly make them.”

3.7. Resulting theory

Figure illustrates the three main themes (in large font) established via grounded theory analysis: “influencing environment,” “occupation,” and “internal experience.” Beneath each main theme, subthemes are listed in small font. The arrows in Figure indicate the ways in which the themes were interrelated, according to the data.

3.7.1. Occupation and environment

The bidirectional blue arrow illustrates the two-way interaction observed in the data between the participants’ occupations and their environments. Data illustrated how a negative environment could impact a person’s ability to engage in occupations that were meaningful—environments often limited access to a range of occupations and thus inhibited participants’ abilities to create occupational lives that were engaging, meaningful, and sustainable. Lack of meaningful participation and/or participation in unsatisfying occupational lives fed into negative environmental dynamics, as is the case for this participant:

No matter how hard I work, it would always go to [stepfather’s] gambling problems. I resent. I saved up all this money to buy a really nice car and he stole my money and stuck me with this junker and said I should be happy about that.

This participant did not derive any meaning from his work, aside from the potential payoff, which was not achieved due to his negative environment. An environment with more occupational opportunities may have allowed the participant to find work that was intrinsically motivating. Additionally, an environment that was safe would have allowed him to use his earnings as he desired. Instead, the participant described having to work extra jobs to fund his stepfather’s gambling habit while also being unable to purchase a nice car. By contrast, another participant describes how a supportive environment fostered his ability to engage in stable routines that included meals and play. Illustrating a bi-directionality, the activities of shared meals and play were described as factors contributing to the sense of stability in the environment:

We were living with my grandparents at the time so I remember a kind of stability there. There was always breakfast. There was always kids to play with um there’s toys. It was it was a good place to live.

Another participant noted: “We have a seven-year old daughter together. Her name is [name] and she is the light of my life. She is my motivator. She keeps me going.” For this participant, having a child contributed to the participant’s motivation to create a positive family environment that was, in turn, uplifting, motivating, and supported the participant’s ability to engage in the role of parent. Being a parent, however, was also described as creating environmental demands that another participant was not equipped to handle:

She and I fought a lot and I started to become violent at that point. I was very violent to both my sisters. I couldn’t cope with the fact that I needed … I had to budget for the food, I had to make sure the shopping got done and the house got cleaned, the cars got taken care of.

This participant’s relationships with his siblings were strained due to the demands of being a parent; thus, the occupational role of parent had a negative impact on his social environment. For this participant, the occupation of being a parent created a stressful environment that consisted of social stressors and occupational demands that the participant could not handle.

3.7.2. Occupation and internal experience

The bidirectional grey arrow illustrates a two-way interaction observed in the data between clients’ occupations and their internal experiences. Clients’ occupational choices impacted their internal experiences. In turn, internal experiences shaped their participation in occupations. This included what occupations participants chose to engage in as well as how they participated (e.g. short-lived, self-harming, a means of escape). For example, some participants described changes in their ability to meaningfully engage in occupations following loss of loved ones, illustrating how the internal experience of grief resulted in reduced occupational participation: “About three months after he [the father] died, I started not being able to function at work” and how lack of participation in life contributed to ongoing or increasing feelings of sadness. Many other participants described how internal experiences of fear, sadness, and anxiety led to using occupations as a form of escape, or resulted in avoidance of occupations all together. Lack of meaningful participation in occupation negatively impacted participants' internal experiences, illustrating the two-way relationship between occupations and internal experience. The clearest and most prevalent example of this was seen in participants' descriptions of avoiding family and drinking compulsively to cope with grief which, in turn, led to additional grief.

The unidirectional orange arrow illustrates that clients’ environments impacted how they experienced life events internally, but that, according to the data, their internal feelings did not directly alter their external environments. One participant described:

I have one older brother. He is three years older than me. I would say we were fairly close; now we are not quite as close anymore, but it is just more because of geographical and … adults, you get busy when you have kids and stuff like that.

This quote shows how the environment, in this case, the geographical location, had an effect on the participant’s ability to connect with his brother, but his internal feelings about the lack of connection were not followed by any related environmental or occupational changes. Figure indicates that individuals’ internal experiences did not directly influence their environments but rather, that internal experiences did influence environments through occupation. In other words, a person’s internal experiences impacted their occupational choices and resulting occupational lives which, in turn, shaped their environments.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the occupational lives of people with BPD in order to identify potential ways occupational therapists and other health-care professions could support wellness for this population. Our objectives were to (1) pinpoint ways in which occupations are compromised by BPD; (2) elucidate ways in which aspects of BPD become occupations for individuals; and (3) articulate key areas in which occupational therapists could support health for people with BPD, based on information from objectives one and two.

4.1. Objective 1 Vignette: how BPD compromised occupational participation and engagement

Participants from this study reported difficulty sustaining relationships and that this difficulty was often related to their BPD symptoms such as extreme emotions and coping with self-harm and substance use. In addition to difficulty sustaining relationships, the participants of this study often reported difficulty keeping jobs. Participants frequently reported dropping out of school and engaging in criminal behavior.

Additionally, both previous literature and findings from this study emphasized the impact of negative, abusive, and/or traumatic environments on psychological development and, in this study, on developing symptoms of BPD, particularly in men. Thus, it is critical to address problematic environmental influences that contribute to the extremely distressing internal experiences within this population.

4.2. Objective 2 Vignette: BPD-as-occupation

The symptoms of BPD such as drug use often became occupations for the participants. Many of the participants developed a role as a mentally ill person and incorporated this new role into their personal identity. They described their identities as “different” than their family members or peers. They identified as people who “couldn’t cope.” They described coping with isolation via drug use and that drug use was also just something they did with their time and something that dictated their finances—both their income and expenses. Although substance abuse is a symptom of BPD, it typically became an integral part of participants’ everyday social and financial life.

This is in line with prior research by Helbig and McKay (Citation2003), who examined substance abuse as an occupation and how occupation is affected by internal and external environments. The researchers concluded that negative environments can lead to occupational imbalance, deprivation, and alienation (Helbig & McKay, Citation2003), which was seen in this study’s participants. More recently, Wasmuth et al. (Citation2014) suggested that addiction is occupational in nature and that providing new occupations may facilitate drug abstinence and recovery in people with addiction and mental illness (Wasmuth et al., Citation2014; S. Wasmuth, Pritchard et al., Citation2016), providing relevant information for addressing the substance use of this study’s participants to escape or cope with troubling life experiences.

4.3. Objective 3 Vignette: how occupational therapists can support health for this population

Participants suggest that it is through occupations that internal experiences can become a catalyst for positive environmental change. Becoming a parent was highly motivating and allowed a participant to change his life. Getting a job was often described as a high point in participants’ lives where they felt productive and were better able to cope with symptoms. Many described enlisting in the army, marines, or air force as helpful initially. Several participants also described playing as a child, and how being engaged in play helped them cope with troubling circumstances in their surroundings.

Several studies have shown the positive impact that meaningful occupational participation can have on internal experiences of people facing numerous kinds of psychosocial challenges (Arbesman & Logsdon, Citation2011; Wasmuth et al., Citation2016). As such, our study suggests using occupations to promote positive internal experiences while also engendering environmental changes that can support and foster ongoing positive internal experiences for people with BPD.

Occupational therapists may positively influence the lives of people with BPD by promoting occupational engagement through social participation and occupations. This form of occupation-based intervention may help people with BPD create and sustain supportive environments. R. A. Sansone and Sansone (Citation2009) report that family intervention could be an effective way of addressing the social environment of individuals with BPD by encouraging family skills, social network building, and coping skills. Nouvini (Citation2017) also found that involving family of those with BPD in treatment can create a therapeutic relationship that can transfer over to all social relationships to create a more positive social environment. S. Wasmuth, Brandon-Friedman et al. (Citation2016) found that altering occupational routines supported positive environmental change and new role identification that fostered substance use disorder recovery.

4.4. Limitations

This study used a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz, Citation2014). A possible limitation of this is that data were interpreted outside the confines of an existing theoretical lens. However, doing so can lead to productive new insights (Hussein et al., Citation2014). Additionally, grounded theory typically involves the researchers re-interviewing participants during the data analysis process on an ongoing basis to verify and distinguish themes as they emerge. However, in this study, the researchers analyzed pre-existing data obtained from a single interview. Participants were not available for researchers to re-interview. However, the data collection tool used for this study is designed to provide rich, qualitative stories of personal experiences and provided researchers with lengthy narratives about participants’ life stories.

Additionally, most of our data were from veteran male participants who were primarily white, therefore illustrating themes that may be specific to this subpopulation. In other words, the composition of our sample might have influenced the results or their generalizability. As mentioned above, literature suggests that BPD affects more women more than men—as such, our study is both limited by its unusual sample and also adds to a gap in the literature regarding men’s experiences of BPD.

In this study, we provided broad theoretical information about relationships between occupational participation, environments, and internal experiences as they related to substance use. However, we did not analyze qualitative data as it related to specific participant conditions such as different substance use or abuse diagnoses and/or comorbid physical and mental health conditions. As such, this study is limited in its ability to elucidate how these conditions differentially impacted participants’ life experiences and vice versa.

4.5. Future research

It may be beneficial to conduct a mixed methods study that examines the qualitative experiences of people with BPD alongside quantitative factors such as age, race, employment status, metacognition and other functional cognition tests, and symptomatology. A study conducted by Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (Citation2004) compared the mixed methods approach to the traditional qualitative and quantitative approaches. Based on this research, they concluded that mixed methods can test grounded theory designs, provide more evidence to support conclusions, and can work in conjunction with qualitative and quantitative methods in order to improve the overall findings related to practice (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004, p. 21).

4.6. Future practice recommendations

Based on this study’s findings, it would be appropriate to add occupational therapists to the multidisciplinary team of practitioners working with people who have BPD. While some mental health settings employ occupational therapists, this is the exception, not the rule (Mahaffey et al., Citation2015). Moreover, as the World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out in their 2017 report Rehabilitation 2030: A Call for Action:

There is a substantial and ever-increasing unmet need for rehabilitation. In many parts of the world, however, the capacity to provide rehabilitation is limited or non-existent and fails to adequately address the needs of the population. With its objective of optimizing functioning, rehabilitation supports those with health conditions to remain as independent as possible, to participate in education, to be economically productive, and fulfil meaningful life roles. (WHO, Citationn.p.)

Integrating occupational therapists into interdisciplinary teams would facilitate future research on the effectiveness of comprehensive rehabilitation from a global perspective—that is, rehabilitation of the whole person in a multitude of contexts, and would aid the WHO’s call to action. Occupational therapists are equipped to deeply examine relationships between a person, their occupations, their environmental contexts, and their internal experiences. In other words, they add a holistic perspective to patient care that translates to and addresses the diversity among various cultures and localities. Mental health concerns including symptoms of BPD are a worldwide concern and are impacted by resources, policies, and social injustices (Chermak, Citation1990). Occupational therapists add to the comprehensiveness of care by helping patients utilize tools they are learning from a variety of providers—putting those tools to use into everyday occupations that have the potential to positively impact their internal experiences and environments. For example, occupational therapists may encourage patients to use a mindfulness activity or CBT training approach in real time to confront and/or respond differently to an environmental challenge, such as a socially unjust comment or action within an alienating environmental setting, thereby altering their environment and their internal experience within it. This study suggests that adding occupational therapists to promote comprehensive and global rehabilitation is essential to truly address the problems faced by people with BPD.

5. Conclusion

Data from this study suggest that people with BPD experience troubling environments and internal experiences. Moreover, we found that occupation is bidirectionally linked to both internal experience and environment, indicating that changing a person’s occupations has the potential to alter both. As such, our findings suggest occupational therapists may be uniquely situated to play a critical role in the recovery of people with BPD, and that their services should be considered alongside other evidence-based approaches for people recovering from BPD. Because occupation is linked to both troubling internal experiences and environments, it stands to reason that occupational therapists, by facilitating positive, meaningful participation in occupations, could improve the wellbeing of people with BPD. Recommendations for practice include (1) supporting people in positive leisure, work, social participation, and education experiences to establish affirming and positive environments for people with BPD and (2) facilitating exploration of and participation in activities (occupations) that are enjoyable and motivating to foster positive mood, emotion regulation, self-image, volition, and overall appraisal of relationships and events.

This research is unparalleled because it looks specifically at the occupational lives of men with BPD and suggests occupational therapy may facilitate meaningful change through occupation-based intervention. Intentional efforts at occupational participation may beneficially address the centrally troubling features of BPD including problematic self-image, self-harm, and risky or disaffirming environments.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the University of Indianapolis for their support in providing the space and time to complete this project, and Kasey Otte for her contributions in the early conceptual stages of this work. We would also like to acknowledge IUPUI’s support of Dr Wasmuth during the final stages of manuscript preparation, and Roudebush VA’s support of Dr Lysaker and the MERIT Institute team for sharing their data for this analysis.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sally Wasmuth

Dr Wasmuth’s background is in African-American Studies, Philosophical Studies of Biology, and Occupational Therapy. Her research focuses on translational and implementation science, particularly in the areas of occupation-based intervention for addictive disorders and dual-diagnosis. She is involved in several arts-based recovery initiatives, including the use of theatre as both a therapeutic intervention and a means of stimulating community conversations on critical topics including the opioid crisis and health-care inequities related to race. Dr Wasmuth’s research agenda focuses on elucidating experiences of marginalized populations, including those with severe mental illness, and developing and testing supportive, empowering, occupation-based interventions. This manuscript is part of a larger body of research comparing the occupational lives of people with a variety of psychosocial and physical health diagnoses.

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process 3rd ed. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68 (Suppl.1), S1-S48.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Arbesman, M., & Logsdon, D. W. (2011). Occupational therapy interventions for employment and education for adults with serious mental illness: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(3), 238–23. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.001289

- Bendics, J. D., Comotis, K. A., Atkins, D. C., & Linehan, M. M. (2012). Weekly therapist ratings of the therapeutic relationship and patient introject during the course of dialectical behavioral therapy for the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy, 49(2), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028254

- Borderline Personality Disorder. (2016, November 8). https://www.nimh.gov/health/topics/borderline-personality-disorder/index.shtml

- Boritz, T., Barnhart, R., & McMain, S. F. (2016). The influence of posttraumatic stress disorder on treatment outcomes of patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(3), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2015_29_207

- Busch, A. J., Balsis, S., Morey, L. C., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2016). Gender differences in borderline personality disorder features in an epidemiological sample of adults age 55–64: Self versus informant report. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(3), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2015_29_202

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE Publications.

- Charmaz, K., & McMullen, L. M. (2011). Five ways of doing qualitative analysis: Phenomenological psychology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, narrative research, and intuitive inquiry. InGuilford Press.

- Chermak, G. D. (1990). A global perspective on disability: A review of efforts to increase access and advance social integration for disabled persons. International Disability Studies, 12(3), 123–127. https://doi.org/10.3109/03790799009166266

- Dedoose Version 8.0.35. (2018). Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. www.dedoose.com

- Denzin, N. K. (1973). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Transaction Publishers.

- Falklof, I., & Haglund, L. (2010). Daily occupations and adaptation to daily life described by women suffering from borderline personality disorder. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 26(4), 354–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2010.518306

- Frías, Á., & Palma, C. (2014). Comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder: A review. Psychopathology, 48(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363145

- Gagnon, J. (2017). Defining borderline personality disorder impulsivity: Review of neuropsychological data and challenges that face researchers. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders, 1(3), 154–176. https://doi.org/10.26502/jppd.2572-519X0015

- Goldhammer, H., Crall, C., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2019). Distinguishing and addressing gender minority stress and borderline personality symptoms. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(5), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000234

- Gunderson, J. G. (2009). Borderline personality disorder: Ontogeny of a diagnosis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(5), 530–539. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121825

- Helbig, K., & McKay, E. (2003). An exploration of addictive behaviours from an occupational perspective. Journal of Occupational Science, 10(3), 140–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2003.9686521

- Hussein, M. E., Hirst, S., Salyers, V., & Osuji, J. (2014). Using grounded theory as a method of inquiry: Advantages and disadvantages. The Qualitative Report, 19(27), 1–15. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss27/3

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Kaess, M., von Ceumern-lindenstjerna, I., Parzer, P., Chanen, A., Mundt, C., Resch, F., & Brunner, R. (2012). Axis I and II comorbidity and psychosocial functioning in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology, 46(1), 55-62. https://doi.org/10.1159/00038715

- King, A. M., Rizvi, S. L., & Selby, E. A. (2019). Emotional experiences of clients with borderline personality disorder in dialectical behavior therapy: An empirical investigation of in-session affect. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 10(5), 468. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000343

- Kingdon, D. G., Ashcroft, K., Bhandari, B., Gleeson, S., Warikoo, N., Symons, M., Taylor, L., Lucas, E., Mahendra, R., Ghosh, S., Mason, A., Badrakalimuthu, R., Hepworth, C., Read, J., & Mehta, R. (2010). Schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder: Similarities and differences in the experience of auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and childhood trauma. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(6), 399–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e08c27

- Lysaker, P. H., & Lysaker, J. T. (2002). Narrative structure in psychosis: Schizophrenia and disruptions in the dialogical self. Theory & Psychology, 12(2), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354302012002630

- Mahaffey, L., Burson, K. A., Januszewski, C., Pitts, D. B., & Preer, K. (2015). Role for occupational therapy in community mental health: Using policy to advance scholarship of practice. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 29(4), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2015.1051689

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2017). Borderline personality disorder. National Alliance of Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Borderline-Personality-Disorder

- Nouvini, R. (2017). The role of family and society in borderline personality disorder treatment outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(10), suppl., S36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.142

- O’Connell, B., & Dowling, M. (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(6), 518–525. https://doi.org/10.111/ipm12116

- Pearse, L., Dibben, C., Ziauddeen, H., Denman, C., & McKenna, P. (2014). A study of psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(5), 368–371. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000132

- Pennay, A., Cameron, J., Reichert, T., Strickland, H., Lee, N. K., Hall, K., & Lubman, D. I. (2011). A systematic review of interventions for co-occurring substance use disorder and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41(4), 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/k.jsat.2011.05.004

- Reitan, A. (2013). Treating schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder differently. Global Neuroscience Initiative Foundation. http://brainblogger.com/2013/11/04/treating-schizophrenia-and-borderline-personality-disorder-differently/

- Roe, D., Hasson-Ohayon, I., Kravetz, S., Yanos, P. T., & Lysaker, P. H. (2008). Call it a monster for lack of anything else: Narrative insight in psychosis. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(12), 859. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31818ec6e7

- Rossouw, T. I., & Fonagy, P. (2012). Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(12), 1304–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018

- Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2009). The families of borderline patients: The psychological environment revisited. Psychiatry, 6(2), 19. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2719448/

- Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2011). Gender patterns in borderline personality. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 8(5), 16–20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3115767/

- Schilling, L., Moritz, S., Kother, U., & Nagel, M. (2015). Preliminary results on acceptance, feasibility, and subjective efficacy of the add-on group intervention metacognitive training for borderline patients. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 29(2), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.29.2.153

- Schilling, L., Moritz, S., Kriston, L., Krieger, M., & Nagel, M. (2018). Efficacy of metacognitive training for patients with borderline personality disorder: Preliminary results. Psychiatry Research, (April)262, 459–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.024

- Schuppert, M. H., Timmerman, M. E., Bloo, J., van Gemert, T. G., Wiersema, H. M., Minderaa, R. B., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., & Nauta, M. H. (2012). Emotion regulation training for adolescents with borderline personality disorder traits: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(12), 1314–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.002