Abstract

Mass fainting Illness (MFI) has occurred repeatedly for years in factory settings in Cambodia. This study examines factors related to MFI, such as worker ‘characteristics, organizational, psychosocial-work, and non-work factors, among Cambodian-factory workers. A factory-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 740 workers in October 2017 using structured questionnaires. Female workers and workers with longer duration of work had a higher-risk of MFI, but a lower-risk for those working in factory before and those absent due to occupational accident. Organizational determinants, such as workers employed in a shorter fixed-term, and those performing repetitive task and a low-skill work were significantly at a higher-risk of MFI, but a lower-risk for those performing a night/evening shift work. The study also showed that Psychosocial-work complaints, workers with less influence on their choice of co-workers, perceived a high temperature at work, and have little opportunity to work at their best had a lower-risk, but a higher-risk for those who lost jobs and those traveling by bicycles/walking to work. Overall, worker characteristics, organizational determinants, psychosocial-work complaints, and external-work factors were independent predictors explaining 31.8% of the overall-MFI prevalence.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Mass Fainting Illness (MFI) has received increased attention due to its frequent occurrence among intragroup-and-intergroup workers across factories in Cambodia. Many extensive investigations were conducted by the government body to identify contributed factors but failed to conclude any of risk factors. However, none of its preventive measures could be interrupted in each episode. This study is to identify risk factors predicting MFI and determine its prevalence and provide recommendations to improve occupational safety and health in workplace. The current study found that workers “characteristics, organizational determinants, psychosocial work complaints, and external-work factors were independently predicting 31.8% of the overall MFI prevalence. Understanding these risk factors from multidisciplinary fields, including the government body, employers, and workers is supporting and working towards interventions. Putting in place preventive measures and workers” health education program may reduce influencing factors and increase awareness of the impact of work on workers’ health and their participation.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

1. Introduction

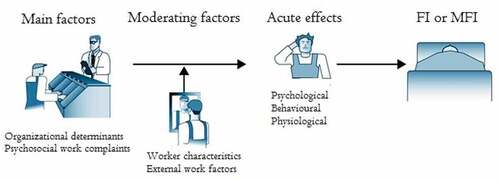

Fainting (or syncope) is unconsciousness due to temporary insufficient cerebral circulation and occurs repeatedly as a consequence of psychological factors, such as life-threatening or stressful conditions (Moya et al., Citation2009). Mass Fainting Illness (MFI), previously known as Mass Psychogenic Illness (MPI) or Mass hysteria, has been found in many settings where large groups of people gather, such as schools, towns/villages, family groups, factories, institutions, and hospitals (Boss, Citation1997; Chowdhury & Brahma, Citation2005; Clements, Citation2003; Shakya, Citation2005). Psychological determinants can play a role in the risk of physical symptoms, and even fainting, excessive workload along with time pressure to a deadline and the subsequently threatening-induced layoff, from two or more people working closely within an intragroup and intergroup, but no organic disorders have been identified (Colligan & Murphy, Citation1979; Lee & Tsai, Citation2010; Tarafder et al., Citation2016). Researchers have found no congruence with determinant factors explaining this phenomenon. However, two common reasons for syncope in the medical domain may be caused by psychogenic disorders, e.g., certain life events or barriers (Moya et al., Citation2009) and somatoform disorders that often occur in occupational settings, which account for physical symptoms but cannot explain the cause (santé Omdl, Organization WH, WHO, Citation1992). Most scientists have specified that repeated outbreaks of MPI or Mass hysteria are due to prevailing job stressors, consisting of two syndromes, mass anxiety characterized by repeated effects of acute anxiety frequently seen in schoolchildren, and motor behaviour often triggered in groups but found in any age, with precipitating factors in the environment (RE Bartholomew & Sirois, Citation2000; Broderick et al., Citation2011; Wessely, Citation1987). Fear-induced fainting is also found in group interactions, which lead to an immediate and acute response, such as blood phobia (Bracha, Citation2004). A toxic environment by-products comprised chemical odours or gases may have underlying life-threatening effects (R Bartholomew & Wessely, Citation1999; Page et al., Citation2010). Several studies on working environmental measurements by an occupational hygienist found that no high-dose threshold levels existed in the workplace (Colligan et al., Citation1979; House & Holness, Citation1997; Jones et al., Citation2000). Additionally, Joint ILO/WHO explicitly specified that individual capability, working conditions, working environments, including monotonous tasks, physical stress, personal relations, and management practices at work, and external work factors and job satisfaction contributed to triggering events such as MFI (Health JIWCoO, Citation1986). According to the NIOSH job stress model (Murphy & Schoenborn, Citation1993), job stressors are job demands (workload and job control), organizational determinants (workers’ role, management practice, job security, and interpersonal relations), and physical stress (noise, fire and burn from heat). Additionally, those factors interacting with moderating factors, such as individual and contextual factors, contribute to the occurrence of health outcomes, such as psychological, physiological, and behavioural illnesses. Other psychosocial hazards at work were described, such as job content, work organization and management, and organizational and environmental conditions in which these stress reactions become, if there is prolonged exposure, psychological and physical stressors (Leka et al., Citation2010). The concept of the job demand and control model initiated by Robert Karasek, known as the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ), explained that a high strain job, which resulted from both a high job demand and low job control, led to psychological strain and physical illness (Stellman, Citation1998). Studying job strain predicted mental strain, which resulted in the risk of mental strain caused by low job control and excessive job demands, and low job dissatisfaction (Karasek, Citation1979). Other factors, such as job demands and job control, led to the highest anxiety and depression attributed to both the high job demand and the low job control, but the highest job satisfaction and the life satisfaction were correlated with the high job demands and the high control and the high depersonalization and the high emotional exhaustion (Dollard et al., Citation2000; Xie, Citation1996). Another study found a mutual association between JDC/JDCS (job demand control and support) and the psychological well-being (Häusser et al., Citation2010). Psychosocial health complaints, including headache, overall fatigue, stomach-ache, sleeping problems, anxiety, muscle pain, and fainting, were caused by psychosocial risk factors at work. A previous study found that monotonous and repetitive work, known as psychosocial work complaints, contributed to health outcomes (Andersen et al., Citation2002).

Mass Fainting Illness has received increased attention due to its frequent occurrence among workers across factories in Cambodia. Several hundreds of workers experienced MFI along with dizziness, nausea, and weakness. These events occurred in intragroups and intergroups of workers one or two times a day with or without reporting, in a manner that was difficult to keep track of all of the fainting cases after each episode. According to the National Social Security Fund (NSSF, MoLVT) reporting from 2011 to 2017, the crude data of the number of factories and workers that had experienced MFI were 12, 24, 15, 34, 32, 18, and 22 and accounted for 1973, 1686, 823, 1806, 1806, 1160, and 1603, respectively. Garment and footwear factories had a higher risk of MFI across factory settings in Cambodia (McMullen, Citation2013). To deal with these problems, the government body has conducted many extensive investigations that were intended to identify contributed factors but failed to conclude any of the risk factors. However, precipitating factors existed in the workplace, such as individual characteristics, organizational factors, psychosocial-work factors and external-work factors, are not excluded. Among several job stress models, the Joint ILO/WHO is known as comprehensive development of knowledge, which indicated underlying various health consequences, mainly focusing on the individual characteristics, the organizational factors, the physical work environmental factors, the psychological well-being, the external work factors, and the job satisfaction. The extent of the findings in this study would be compared with that model. Therefore, the present study examines factors predicting MFI, such as workers ‘characteristics, organizational determinants, psychosocial work complaints, and external work factors, and determines the entire prevalence of MFI among factory workers.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 740 workers (659 women, 81 men) in October 2017, completed with using structured questionnaire. The factory workers aged ranging from 17 to 52 years, those who were employed in factories, agreed to participate in the study by signing an informed consent.

2.2. Sampling and sample size

The sample size was calculated, using an expected MFI of 8% with 23% allowable error and 1.7 precision. A total of 740 workers were recruited from 4 factories (1 Phnom Penh City, 2 Kandal province, and 1 Kampong Speu Province) with 36 workers in each operative section (5/12 working operative sections of the garment factory were at higher risk). There were 8 factories that experienced MFI located in two provinces and Phnom Penh Capital city. A two-stage cluster sampling with the probability proportional to size (PPS) of workers in each factory was applied to recruit the study population (Lemeshow et al., Citation1990).

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Characteristics of workers

Worker characteristics include age, gender, marital status, education, monthly income, family members dependent on their incomes, and the variables concerning the types of occupations, such as the working duration, working in a factory before, a number of working hours per week, the employment contracts, smoking, the absence from work and the reasons, and the measuring weight for the height index (-BMI). Several questions were also on the presence of long-term diseases, such as gastritis/stomach ache, an insomnia, emotional problems, back pain/arthritis, the lung disease, the heart disease, the high blood pressure, and the kidney disease.

2.3.2. Organizational determinants

Organizational determinants are defined as interacting combinations of such elements with or without other existing factors, such as psychosocial work complaints, individual and external factors, may lead to the ill health. There were made to assess elements, such as job content, the work paced and workload, working arrangements, working developments, the management practice at work, the role of workers and the sexual harassment and the physical violence at work.

2.3.3. Psychosocial work complaints

Psychosocial-work complaints refer to interactions between/among the job intensity (or high job demands), job controls, physical work environments, the psychological well-being and the job satisfaction underlying moderating factors resulting in the health consequences. These were measured via the job intensity (two items), the job control and support (seven items), the physical work complaints (17 items), the psychological well-being (5 items), and the job satisfaction (8 items). The response options for each item varied on 5 Likert rating scales from 1 almost always to 5 almost never. The scoring of each question was computed from a total score in each item and then classified into two groups: the scoring below average or equal with the lowest score was coded as a high-risk condition while a low-risk conditions were coded with the scores above average. All items were also computed using Cronbach’s alpha to measure the internal consistency of its reliability; the overall score was 0.763 (data not shown).

2.3.4. External work factors

External work factors (or non-work factors) refer to the work-fitted family demands and the extra activities as well as the mode of transportation and its common use. Workers were also asked to indicate whether they experienced conflicts with family demands, leisure activities and travelling from home to work and back (Yes or No).

2.3.5. Mass fainting illness

Mass Fainting Illness or workers with Mass Fainting Illness is defined as workers who experienced unconsciousness (or unable to move) or dizziness were affected at least one time within the last 6 months before the interview. Those who did not report form of the MFI were assigned as the healthy workers.

Face-to-face interviews with using a structured questionnaire were conducted. The validated questionnaire was freely available existence in the previous study (Parent-Thirion, Citation2007), which was modified and used for identifying factors predicting MFI existed mainly in factory settings. Additionally, this questionnaire was prepared bilingual in English and the Cambodian language and then translated back to English after complete data collection at the fieldworks.

Ethics approval was obtained from Thammasat University Ethics Committee as COA N0 330/2560 and from the National Ethics Committee for Health Research, Cambodia, and Code N0 080 NECHR. Written informed consent from all respondents was obtained before the interviews.

2.3.6. Statistical analysis

Workers who reported MFI due to the psychosocial work complaints and the organizational determinants were compared with workers who did not report a form of MFI. Descriptive data analysis – such as Count, per cent, mean, median, mode and standard deviation – were computed to describe each variable. Simple binary logistics were used to determine the predicting factors of the MFI. All significant variables in these univariate analyses (Chi-square test; p-values<0.05) were selected for further analysis of the multiple logistic regression. Both crude and the adjusted odds ratios (COR and AOR) with the 95% confident interval (CI) were performed. Workers who had missed the response to the answer question data were not included. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0-United States).

3. Results

Among 740 factory workers, only 31.8% had an MFI incident within the last 6 months. The majority (89%) were the female workers, and the average age was 26 years (SD = 6.20). Most workers had a lower education, reporting that they had the completed primary school (45.9%) and the secondary school (40.8%). Workers earned 188 US dollars on average per month, and their working duration was over 4 years on average (). Factors significantly associated with MFI for the crude analysis (p-values <0.05) were included in the multivariate logistic regression. Workers “characteristics showed that the female workers had a higher risk of the experiencing MFI (OR = 3.93 95% CI = 1.97–7.83) compared to the male workers, but workers who had worked in a factory before had a lower risk of MFI (OR = 0.60 95% CI = 0.41–0.86). Regarding the duration of work, workers who had a longer total -working duration had a higher risk of MFI (OR = 1.85 95% CI = 1.04–3.29); this was somewhat reduced from OR = 1.90 to OR = 1.85 after adjusting for the other variables. The majority of workers who reported an absence from work for various reasons; workers who were absent due to the occupational accident (OR = 0.08 95% CI = 0.05–0.16) had a lower risk of MFI while there was not a significant association with workers who were absent due to the health problems (OR = 0.57 95% CI = 0.32–1.02). Regarding the main occupations held among factory workers, workers employed on a shorter fixed-term employment had a higher risk of MFI (OR = 1.92 95% CI = 1.22–3.01) compared to those who reported the other employment. Regarding job contents, workers performing with a repetitive work 30 seconds-1 minute (OR = 1.86 95% CI = 1.02–3.39) and workers with a low working skills (OR = 1.81 95% CI = 1.26–2.61) had a higher risk of MFI while workers with a night/evening shift work had a lower risk (OR = 0.17 95% CI = 0.05–0.64). Significantly identified that Psychosocial work complaints were known as predicting factors included workers who had a less influence on their choice of the working partners (OR = 0.65 95% CI = 0.43–0.97), workers who were at a low-risk of the high temperatures at work (OR = 0.58 95% CI = 0.41–0.83), Workers with a low opportunity to work at their best (OR = 0.59 95% CI = 0.43–0.82) had a lower risk of MFI. However, workers with a low risk of a lost job in the next 6 months had a higher risk of MFI (OR = 1.71 95% CI = 1.19–2.46) compared to those who did face a high risk of a lost job. Additionally, workers who travelled by bicycle/walked to work had a significantly higher risk of MFI (OR = 2.07 95% CI = 1.37–3.13) compared to those who travelled to work by other means. Regarding the impact of work on the workers health in the last 12 months, workers who reported an illness had a lower risk of MFI (OR = 0.49 95% CI = 0.30–0.79) compared to those who did not report an illness. Common physical symptoms significantly associated with MFI that were included the lung disease/asthma (OR = 0.41 95% CI = 0.23–0.74), the heart disease/high blood pressure (OR = 0.26 95% CI = 0.11–0.60), and the kidney disease (OR = 0.24 95% CI = 0.09–0.66), as detailed shown in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of 740 workers with MFI

Table 2. Factors associated with MFI (n = 740)

4. Discussion

Our results revealed that 31.8% of workers experienced MFI in the last 6 months. This magnitude is consistent with the study of the Stress-induced Mass Psychogenic Illness (MPI) in the industrial workers at 33% (Hall & Johnson, Citation1989). Other studies found an 18% prevalence of MFI in a study of MPI in an electronics plant (Colligan et al., Citation1979) and a higher prevalence of 56.8% of Mass Hysteria among adolescent female students in Taiwan (Chen et al., Citation2003; Colligan & Murphy, Citation1979). Our study indicated that 89% were the female workers, and their risk of MFI was increased compared to the male workers. This result is consistent with the experimental study conducted by William (Lorber et al., Citation2007) and similar to other studies on the risk of MPI in the schools with the 90% female students (Olkinuora, Citation1984; Tarafder et al., Citation2016). The study presented that workers who ever worked in a factory had a higher risk of MFI compared to those working in a factory for the first time. This finding might be due to the effects of the working and environmental determinants that may exist in the workplace and particularly the coping with each behaviour. Additionally, those who worked for a long period of over 7 years had a significantly increased risk of MFI compared to those working for a short period of less than 2 years. The study also found that 75% of workers were absent from work in the past, mainly due to illness (60.5%). This finding might be related to the impact of their work underlying the psychosocial work complaints and the organizational factors. Absence due to illness or the occupational injuries was related to the psychosocial work complaints. The study found that workers’ absences due to occupational accidents were associated with a higher risk of MFI than those who did not have absences. This result is similar to the result from the study on absences attributed to psychosocial work complaints (Otsuka et al., Citation2007; Voss et al., Citation2001) but did not include a risk of MPI. Repetitive tasks, considered a job stressor of psychosocial hazards at work, if prolonged, may contribute to the effects of the psychosocial and the physical stress (Leclerc et al., Citation2001). The study revealed that 75.2% of workers performed a monotonous work; of which 98% performed the repetitive work (data not shown) for 2–4 years (47.3%). Our results found that workers performing repetitive work for 30 seconds-1 minute that were significantly correlated with the risk of MFI. This finding is consistent with the report of MPI (Hall & Johnson, Citation1989). Our study also indicated that workers with the low working skills (further needed training) were associated with a higher risk of MFI because they reported 56.2% of tasks needed in the different skills, and they had neither attended the training nor had received on-the-job training. This finding is consistent with a report of MPI among fish packaging employees (House & Holness, Citation1997). Night/evening shift work is a non-standard schedule with psychosocial risk factors if prolonged, can result in the negative health outcomes (Deng et al., Citation2018; Merkus et al., Citation2012; Yang et al., Citation2016) such as the physical stress, the depression, the heart disorder, and the gastritis. Physical arousal such as MFI might be provoked in cases of the acute responses to the poor psychosocial work determinants in the working environments, the excessive workload and the low job control. In our study, a night/evening shift work was associated with a higher risk of MFI. The study found that workers agreed that a less influence on their choice of the co-workers, and those having little opportunity to work at their best were factors associated with a higher risk of MFI. Restricting the choice of working partners and not offering the opportunity to workers led to work-related stress. Our study found that most workers reported neither assistance from their co-workers if needed nor influencing their co-workers at rates of 55.1% and 80.4%, respectively, but these variables are not associated.

Poor ventilation under certain circumstances generates a high temperature, which can cause a loss of the concentration, the boredom and the exhaustion, resulting in a physical stress or a discomfort (Magnavita et al., Citation2011). Our study showed that workers agreed that a high temperature at work was significantly contributed to the risk of MFI. This result is consistent with MPI in the electronic workers (Colligan et al., Citation1979). Being laid off from a job and the job insecurity vary from the factory to the factory. Our result found that job lay-offs in the next 6 months were associated with the risk of MFI. Workers who employed on a shorter fixed-term employment and with a low working skills potentially face job lay-offs, reporting 61.8% and 31.3%, respectively. Our result also found that workers who travelled by walking/bicycling to work had a significantly higher risk of MFI than those who travelled to work by other means. This finding might be due to increased the fatigue while performing the jobs at home, such as 82.6% who reported the cooking and the housing work and 70.3% who reported caring for the elderly (data not shown), but these variables were not associated with MFI. In this study, the existing health conditions that were significantly contributed to the risk of MFI.

By definition (ICD-10), MFI is defined as a somatoform disorder due to the psychological factors or the life-induced threatening. For instance, poor working conditions and working environments existed in the workplace are likely contributed, while the occupational safety and health (OSH) regulations are concurrently confined to be carrying out. Regarding occurring MFI, the main factors, underlying moderating factors, may develop adverse health effects. All of those factors may vary among factory settings or countries; however, the MFI case is rarely found in other countries. Many factors that were found significantly different from the other studies, which are included workers who ever worked in a factory; workers who had worked for a long period (over 7 years); those who were absent from work by the occupational accidents; and those who were existed the health conditions. Additionally, workers performed with a night/evening shift work, perceived a less influence on their choice of the co-workers, received a little opportunity to work their best, and perceived a lost job in the next 6 months. Therefore, prediction factors of MFI included the psychosocial work complaints, the organizational determinants, the external work factor and the workers’ characteristics as independently predicting factors explaining this phenomenon. This profile was consistent with a report of MFI, indicating that such work could be stressful or life-threatening.

4.1. Limitations

This study has a few limitations. Variables in this study were not significant factors or were not reported as common problems, such as the physical violence and the sexual harassment at work. These problems might not receive attention in their workplaces. However, this tool was a modified questionnaire and used to determine that the psychosocial work complaints and the organizational determinants were predicting factors of MFI. Most importantly, the impact of mental health was not included. Instead, the impact of work on health has been contributed to the risk of MFI in this study. However, the study suggests that investigating mental health disorders is necessary.

5. Conclusion

The study found that female workers and those working for a long period had a higher risk of MFI. Workers employed for a shorter fixed-term, those who performed the repetitive work and had the low working skills had a higher risk of MFI. Psychosocial work complaints were significantly determined that workers reported a less influence on their choice of the co-workers, perceived a high temperature at work and have a little opportunity to work at their best had a lower risk of MFI while those who faced losing a job in the next 6 months had a higher risk. External-work factors recognized as precipitating factors were indicated that workers who travelled by bicycling/walking to work had a higher risk of MFI compared to those who were travelled to work by other means. In short, certain workers' characteristics, organizational determinants, psychosocial-work complaints, and external-work factors were independent predictors explaining 31.8% of the overall-MFI prevalence.

A multi-level approach immediately focuses on identifying these risk factors and working towards interventions. Encouraging and promoting national policy and OSH regulations as well as multidiscipline professionals, such as occupational hygienists and occupational physicians, are warranted. Most importantly, putting in place the preventive measures and the workers health education programme is more important for mitigating and preventing from risk factors in the workplace as well as working towards increasing awareness of the impact of work on workers health and their participation.

Author contributions

Maly PHY, Twisuk PUNPENG, Chaweewon BOONSHUYAR, and Thanu CHARTANANONDH have made substantial contributions to the conception, design, and acquisition of the data.

Maly PHY and Chaweewon BOONSHUYAR have made substantial contributions to the analysis and the interpretation of the data.

Maly PHY, Twisuk PUNPENG, and Chaweewon BOONSHUYAR have been involved in drafting the manuscript.

Maly PHY, Twisuk PUNPENG, and Chaweewon BOONSHUYAR have been involved in revising it critically for the important intellectual content.

All authors have given the final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the research assistants, the readers, the translators, and the participants. I would like to express my profound gratitude to Thammasat University for full financial support of my study in Thailand.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maly Phy

Maly Phy, MD, MPH, is a senior technical officer at the Department of Occupational Safety and health, Cambodia, where he has worked since 2013. Currently, he is a Doctoral Candidate in Occupational Health at Thammasat University. He also teaches in Occupational Health at the School of Public Health, NIPH, and the University of Health Science-BPH. Prior to his current position, he performed over nineteen-year for Ministry of Health, working experiences with Quality Health Assurance in Hospital Department, and Kampot Provincial Health Department, Angkorchey-OD was accounted as Vice-chief of Health Centers.

Twisuk Punpeng, DSc., is a deputy dean for Administrative Affairs at Thammasat University. He is interested in teaching quality of work life and Occupational and Environmental Toxicology.

Chaweewon Boonshuyar, MSc, is an assistant professor at Thammasat University, Mahidol University and Chulalongkorn University. She is interested in teaching Bio-statistics.

Thanu Chartananondh, MD, is a psychiatrist at Thammasat University Hospital. He works as a psychiatric physician in the Department of Psychiatry.

References

- Andersen, J. H., Kaergaard, A., Frost, P., Frølund Thomsen, J., Peter Bonde, J., Fallentin, N., Borg, V., & Mikkelsen, S. (2002). Physical, psychosocial, and individual risk factors for neck/shoulder pain with pressure tenderness in the muscles among workers performing monotonous, repetitive work. Spine, 27(6), 660–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200203150-00017

- Bartholomew, R., & Wessely, S. (1999). Epidemic hysteria in Virginia: The case of the Phantom Gasser of 1933-1934. Southern Medical Journal, 92(8), 762–769. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007611-199908000-00003

- Bartholomew, R. E., & Sirois, F. (2000). Occupational mass psychogenic illness: A transcultural perspective. Transcultural Psychiatry, 37(4), 495–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346150003700402

- Boss, L. P. (1997). Epidemic hysteria: A review of the published literature. Epidemiologic Reviews, 19(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017955

- Bracha, H. S. (2004). Freeze, flight, fight, fright, faint: Adaptationist perspectives on the acute stress response spectrum. CNS Spectrums, 9(9), 679–685. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852900001954

- Broderick, J. E., Kaplan-Liss, E., & Bass, E. (2011). Experimental induction of psychogenic illness in the context of a medical event and media exposure. American Journal of Disaster Medicine, 6(3), 163. https://doi.org/10.5055/ajdm.2011.0056

- Chen, C.-S., Yen, C.-F., Lin, H.-F., & Yang, P. (2003). Mass hysteria and perceptions of the supernatural among adolescent girl students in Taiwan. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(2), 122–123. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NMD.0000050941.22170.A5

- Chowdhury, A., & Brahma, A. (2005). An epidemic of mass hysteria in a village in West Bengal. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 47(2), 106. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.55956

- Clements, C. J. (2003). Mass psychogenic illness after vaccination. Drug Safety, 26(9), 599–604. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200326090-00001

- Colligan, M. J., & Murphy, L. R. (1979). Mass psychogenic illness in organizations: An overview. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 52(2), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1979.tb00444.x

- Colligan, M. J., Urtes, M.-A., Wisseman, C., Rosensteel, R. E., Anania, T. L., & Hornung, R. W. (1979). An investigation of apparent mass psychogenic illness in an electronics plant. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 2(3), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00844926

- Deng, N., Kohn, T. P., Lipshultz, L. I., & Pastuszak, A. W. (2018). The relationship between shift work and men’s health. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 6(3), 446–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.11.009

- Dollard, M. F., Winefield, H. R., Winefield, A. H., & De Jonge, J. (2000). Psychosocial job strain and productivity in human service workers: A test of the demand‐control‐support model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(4), 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900167182

- Hall, E. M., & Johnson, J. V. (1989). A case study of stress and mass psychogenic illness in industrial workers. Journal of Occupational Medicine.: Official Publication of the Industrial Medical Association., 31(3), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-198903000-00010

- Häusser, J. A., Mojzisch, A., Niesel, M., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Ten years on: A review of recent research on the job demand–control (-support) model and psychological well-being. Work and Stress, 24(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678371003683747

- Health JIWCoO. (1986). Psychosocial factors at work: Recognition and control. International Labour Organisation.

- House, R. A., & Holness, D. L. (1997). Investigation of factors affecting mass psychogenic illness in employees in a fish‐packing plant. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 32(1), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199707)32:1<90::AID-AJIM11>3.0.CO;2-1

- Jones, T. F., Craig, A. S., Hoy, D., Gunter, E. W., Ashley, D. L., Barr, D. B., Brock, J. W., & Schaffner, W. (2000). Mass psychogenic illness attributed to toxic exposure at a high school. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(2), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200001133420206

- Karasek, R. A., Jr. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392498

- Leclerc, A., Landre, M.-F., Chastang, J.-F., Niedhammer, I., Roquelaure, Y., & Work, S. (2001). Upper-limb disorders in repetitive work. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 24(4), 268-278. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.614

- Lee, Y.-T., & Tsai, S.-J. (2010). The mirror neuron system may play a role in the pathogenesis of mass hysteria. Medical Hypotheses, 74(2), 244–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2009.09.031

- Leka, S., Jain, A., & Organization, W. H. (2010). Health impact of psychosocial hazards at work: An overview. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44428

- Lemeshow, S., Hosmer, D. W., Klar, J., Lwanga, S. K., & Organization, W. H. (1990). Adequacy of sample size in health studies. Chichester : Wiley. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41607

- Lorber, W., Mazzoni, G., & Kirsch, I. (2007). Illness by suggestion: Expectancy, modeling, and gender in the production of psychosomatic symptoms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 112–116. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3301_13

- Magnavita, N., Elovainio, M., De Nardis, I., Heponiemi, T., & Bergamaschi, A. (2011). Environmental discomfort and musculoskeletal disorders. Occupational Medicine, 61(3), 196–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqr024

- McMullen, A. (2013). Shop’til they drop: fainting and malnutrition in garment workers in cambodia. Labour behind the Label; Community Legal Education Centre: Phnom Penh, Cambodia. https://www.cleanclothes.org/resources/national-cccs/shop-til-they-drop (Accessed on Oct 2018).

- Merkus, S. L., Van Drongelen, A., Holte, K. A., Labriola, M., Lund, T., van Mechelen, W., & van der Beek, A. J. (2012). The association between shift work and sick leave: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 69(10), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2011-100488

- Moya, A., Sutton, R., Ammirati, F., Blanc, J., Michele B., ... Walma, J., Wieling, W. (2009). Guidelines: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): The task force for the diagnosis and management of syncope of the european society of cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal, 30(21), 2631. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

- Murphy, L. R., & Schoenborn, T. F. (1993). Stress management in work settings. DIANE Publishing.

- Olkinuora, M. (1984). Psychogenic epidemics and work. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 10(6), 501-504. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.2294

- Otsuka, Y., Takahashi, M., Nakata, A., Haratani, T., Kaida, K., Fukasawa, K., Hanada, T., & Ito, A. (2007). Sickness absence in relation to psychosocial work factors among daytime workers in an electric equipment manufacturing company. Industrial Health, 45(2), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.45.224

- Page, L. A., Keshishian, C., Leonardi, G., Murray, V., Rubin, G. J., & Wessely, S. (2010). Frequency and predictors of mass psychogenic illness. Epidemiology, 21(5), 744–747. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e9edc4

- Parent-Thirion, A. (2007). Fourth European working conditions survey. Office for official Publ. of the European Communities.

- santé Omdl, Organization WH, WHO. (1992). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines (Vol. 1). World Health Organization.

- Shakya, R. (2005). Epidemic of hysteria in a school of rural eastern Nepal: A case report. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 1(4), n4. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26416760

- Stellman, J. M. (1998). Encyclopaedia of occupational health and safety (Vol. 1). International Labour Organization.

- Tarafder, B. K., Khan, M. A. I., Islam, M., Mahmud, S., Sarker, H., Faruq, I., Miah, T., Arafat, Y. (2016). Mass psychogenic illness: Demography and symptom profile of an episode. Psychiatry Journal, 5 2016. http://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2810143

- Voss, M., Floderus, B., & Diderichsen, F. (2001). Physical, psychosocial, and organisational factors relative to sickness absence: A study based on Sweden post. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(3), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.58.3.178

- Wessely, S. (1987). Mass hysteria: Two syndromes? Psychological Medicine, 17(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700013027

- Xie, J. L. (1996). Karasek’s model in the People’s Republic of China: Effects of job demands, control, and individual differences. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1594–1618. https://doi.org/10.2307/257070

- Yang, H., Hitchcock, E., Haldeman, S., Swanson, N., Lu, M.-L., Choi, B., Nakata, A., & Baker, D. (2016). Workplace psychosocial and organizational factors for neck pain in workers in the United States. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 59(7), 549–560. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22602