Abstract

The purpose of this cross-sectional web-based study was to assess the prevalence of perceived stress among dental faculties of Government Dental Colleges across the state of Kerala, India, during the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has a huge impact on both physical and psychological well-being of persons all over the world. Human transmission of this disease occurs mainly through droplet inhalation and hence, direct contact with mucous membranes and saliva is considered risky. The study was conducted using a five-point scale PSS10 (Perceived Stress Scale) questionnaire. Comparison between study groups (gender and age group) with continuous variables (PSS score) was done using independent t test. The chi-square test was used to compare the age group and gender with PSS categories; low, moderate and high. The mean PSS score of the respondents was 17.43 ± 6.45 with a range from 2 to 35 with women having higher mean stress scores (18.15 ± 6.54) compared to men (16.46 ± 6.24). Participants aged 40 years and less reported higher PSS scores (18.60 ± 6.40) compared to the older age group (16.14 ± 6.30). Since varying amounts of stress are present in different groups, etiology of perceived stress and measures to control it may be investigated in the future so as to avoid stress-related crisis in the health sector. Effective stress management measures like mindfulness are highly recommended.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

COVID-19 came as a lightening surprise and was a unique enigma for the entire mankind. Even the scientific community was perplexed about its natural course, impacts in the health sector, societal implications and consequences on the mental health of people. Economy can be revived and health can be re-established, but psychological effects are difficult to reverse. Researches on psychological implications could play a pivotal role in re-establishing the damaged societal equilibrium. This research tries to explore the perceived stress level among the teachers of Government Dental Colleges of Kerala, one of the states with highest population density in the republic of India. The study reveals elevated perceived stress levels among them, although they are one of the most literate communities. The pandemic will adversely affect the life of each and every section of the society. This article will provide invaluable insights into this and will motivate the scientific community to conduct similar studies in all domains of life.

1. Introduction

Stress often arises as the response of an individual to various stimuli occurring in their internal and external environment. The level of stress depends upon various factors like perception of the individual, capacity of a person to deal with certain situations, etc. (Resources, Citation2019). Continuous exposure to stress results in anxiety, tension, lack of concentration and various health-related problems. Eventually, it may even lead to depression or anxiety disorders. Stressful environments may also lead to sleep problems, accidents, increased use of alcohol and other narcotics, eating disorders and so on.

Perceived stress is the feeling of individuals about general stressfulness of their life in a given time period and their ability to deal with such problems or difficulties (Liu et al., Citation2020). The perceived stress scale (PSS) is the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring the degree to which situations in a person’s life are measured as stressful (Cohen et al., Citation1983).

Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a pandemic that has been having a huge impact on both physical and psychological well-being of persons all over the world. It was first identified in late December 2019 when clusters of pneumonia of unknown etiology started appearing in the city of Wuhan in China. The disease then started to spread beyond Wuhan to all regions of China and later worldwide. As of September 2020, globally, more than 30.6 million cases were confirmed and 950,000 deaths were reported to WHO (Adhershitha et al., Citation2020). The clinical features apart from stress include fever, cough, shortness of breath, muscle pain, confusion, headache, sore throat, rhinorrhoea, chest pain, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting. Human transmission of this disease occurs directly through sneezing, coughing and droplet inhalation or by direct contact with mucous membranes and saliva (Khurshid et al., Citation2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be perceived as a significant stressor for many people. A systematic review of the impact of the pandemic on mental health in general population shows that there is an unprecedented threat to the mental health of the people (Jiaqi et al., Citation2020). Continuous exposure to distress will lead to a decline in psychological health of individuals (Weinberg & Cooper, Citation2011).

The COVID-19 pandemic may have a psychological impact on healthcare workers as well. There is a great chance for healthcare workers in developing both physical and mental health-associated problems due to occupational exposure with COVID-19 patients (Shaukat et al., Citation2020). In China, around 3000 healthcare workers have been reported COVID-19-positive, more than 22 of them lost their lives and there are reports of family transmission as well (Adams & Walls, Citation2020). According to Indian Medical Association (IMA), COVID-19 data as on 16 September 2020, 2238 doctors in India were infected with the disease and out of them 382 lost their lives. Later, on 2nd of October 2020, IMA updated their data indicating that 515 doctors had lost their lives. Prolonged use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) causes various discomforts and results in headache and chronic fatigue among health care workers. Those with pre-existing headaches are more prone to such PPE-induced headaches (Ong et al., Citation2020) (Zaheer et al., Citation2020). These physical symptoms may be psychological distress (Lam et al., Citation2009). Stressful conditions in which doctors and other healthcare workers are repeatedly exposed may lead them to depression and burnout (Uzma et al., Citation2020).

The field of medicine and dentistry is facing a lot of challenges since the outbreak of COVID-19 (Paul, Citation2020). Even the regular teaching practices of medical and dental colleges have been affected. Dental faculties need to be more concerned about their student’s safety, patient’s safety and their own safety. Dental treatment procedures involve close contact with the patient and most of the common procedures are aerosol generating (Izzetti et al., Citation2021). Such aerosols will linger in the atmosphere for 10 minutes following a dental procedure and have the potential risk of spreading the infection (Imran et al., Citation2021) . In a study conducted on eleven COVID-19 patients in a Hong Kong hospital, consistent presence of coronavirus was reported in the saliva of patients from the first day of hospitalization. It has also been reported that the virus is found in the ACE 2 receptors of tongue, floor of the mouth and other oral structures. (Khurshid et al., Citation2020) (Xu et al., Citation2020). Dental professionals are thus required to modify many of their activities in order to reduce their professional contagion risk (Izzetti et al., Citation2021). Aerosol reduction and infection control protocols need to be implemented. Measures like initial virus screening, identification of urgent clinical conditions and promoting telemedicine to reduce the chances of cross infection, ensuring adequate safety precautions like use of personal protective equipment (PPE), minimizing invasive treatment, use of high speed suction, etc. are to be followed to reduce the risk of infection (Cianetti et al., Citation2020). Antiviral agents such as mouth washes also help in reducing viral load in mouth and subsequently in aerosols, thereby reducing the potential risk of cross infection (Imran et al., Citation2021). A global study evaluating knowledge and attitude of dental health professionals revealed that a majority of them have insufficient knowledge regarding the fundamental aspects for implementing disinfection protocols to reduce the spread of COVID-19. At the same time, they showed a positive attitude towards disinfection against virus (Sarfaraz et al., Citation2020).

As per latest statistics by Ministry of Health and Family Welfare dated 07/10/2020, 87,823 cases and 884 deaths have been reported in the state of Kerala. COVID-19 duties are being entrusted to doctors from all disciplines working in the Government sector including dental faculties and very few studies have examined their perceived stress levels.

The aim of this research was to find the prevalence of perceived stress among dental faculties of Government dental colleges in the state of Kerala, India. Null hypothesis for this study was that the Covid-19 pandemic did not result in perceived stress among dental faculties.

2. Materials and methods

A cross-sectional web-based survey was conducted during the month of October 2020 using Google forms among dental faculties of all the five Government Dental Colleges across Kerala and a total of 162 faculties participated in this study. Since it was a population study, all the faculties were included. The sole exclusion criterion was the unwillingness to participate in the survey. The questionnaire in English () included demographic details such as Name, Place of institution, Age and Gender. For assessing the perceived stress of respondents during the COVID-19 pandemic, 10 questions of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS10) were used (Chan & La Greca, Citation2020). Questions were answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 5. Question numbers 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 10 in the PSS10 were scored from 0 to 4, whereas 4, 5, 7 and 8 were scored reversely, from 4 to 0 (Cohen et al., Citation1983).

Table 1. Questionnaire

2.1. Statistical analysis

Observed data were coded, tabulated and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Descriptive data were reported as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency and percentages for categorical variables. The perceived Stress score for an individual was calculated by adding the scores for each of the 10 questions. They were further categorized into low perceived stress (0–13), moderate perceived stress (14–26) and high perceived stress (27–40). Comparison between study groups (gender and age group) with continuous variables (PSS score) was done using an independent t test. The chi-square test was used to compare the age group and gender with PSS categories; low, moderate and high. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

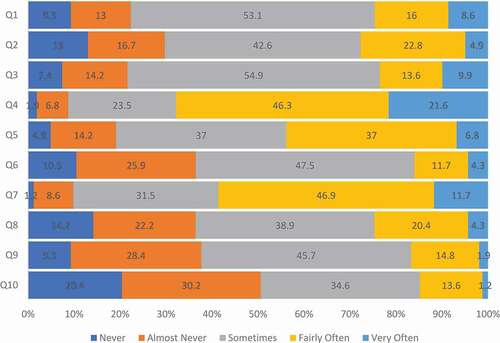

Out of the total respondents, women constituted 57.4% of the study sample. The mean age of the study participants was 40.28 ± 8.96 years with a range from 23 to 61 years. The mean PSS score of the respondents was 17.43 ± 6.45 with a range from 2 to 35. Aggregate responses of the study participants for each question in the PSS scale questionnaire are given in and the questions are given in .

A gender-wise analysis was carried out based on PSS scores and categories of stress. It was observed that women had higher mean stress scores (18.15 ± 6.54) compared to men (16.46 ± 6.24), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.178). Participants aged 40 years and less reported higher PSS scores (18.60 ± 6.40) compared to the older age group (16.14 ± 6.30) and the differences were statistically significant (p = 0.015) (.).

Table 2. Comparison of mean PSS scores among study groups

67.3% of the participants exhibited moderate level of perceived stress. 25.9% showed only mild perceived stress levels, whereas 6.8% manifested high levels of stress. Comparison of different categories of perceived stress revealed that 60.9% of total men and 72.0% of total women participated in the study had moderate perceived stress levels. 33.3% and 20.4% of total men and women showed mild perceived stress. Among the total men and women, only 5.8% and 7.5% showed high perceived stress. But there was no statistically significant difference between the genders (p = 0.178). An analysis of categories of stress based on age showed that 33.8% of participants aged greater than 40 years had mild levels of stress, while only 18.8% of the younger age group (≤ 40 years) shows mild stress. 62.3% of the participants aged greater than 40 years had moderate levels of perceived stress, while the value was 71.8% among the younger age group. Regarding high-stress group, the values were 3.9% and 9.4% for greater than 40 years age group and younger age group, respectively. However, the differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.054) (.).

Table 3. Comparison of PSS categories among study groups

4. Discussion

The two major challenges faced by dental faculties in the present scenario are potential risk of spreading the infection as a result of close interaction with patients and difficulty in teaching the practical aspects of dentistry when classes are restricted to online platforms. A survey on undergraduate dental students revealed their dissatisfaction towards teachers’ ability to deliver online lectures and their difficulty in adjusting to online learning (Sarwar et al., Citation2020). A study on perceived COVID-19 risk on dentistry showed that COVID-19 has affected the well-being of dental professionals all over the world (Gambarini et al., Citation2020).

Some level of perceived stress was exhibited by all the members of the present study group. 67.3% of the total respondents were having moderate levels and 6.8% of them were having high levels of perceived stress. These indicate that the unique demands of the disease (COVID-19) have contributed towards perceived stress in dental faculties. A study conducted in Wuhan, China, during the pandemic has demonstrated moderate to severe levels of stress in health care workers (Du et al., Citation2020).

A comparison based on genders showed that the average stress level was higher in women, although the difference was not statistically significant. Further comparison of different categories of stress (mild, moderate and high) revealed that among respondents with moderate and high levels of stress, percentage of women stood higher. The difference here too was not statistically significant. This finding is in agreement with many of the previous studies, which revealed higher perceived stress levels in women (Flores et al., Citation2008) (Meira et al., Citation2020). An article on COVID-19 has also indicated the increased care burden of women during the pandemic (Power, Citation2020). More research is required to find the effect of COVID-19 on the perceived stress level of female dental faculties.

The study participants aged 40 years and less showed higher level of stress compared to those who are above 40 years and the difference was statistically significant. Many previous studies have demonstrated that the level of perceived stress decreases with age (Sheldon & Williamson, Citation1988) (Hamarat et al., Citation2001). A previous research on the role of adult age and global perceived stress showed that the daily stressors experienced by the younger adults is substantially greater than those experienced by the older adults (Stawski et al., Citation2008). More COVID-related duties and online classes have been entrusted to the junior doctors in Government Dental Colleges of Kerala. Therefore, the senior faculties might have reduced stressor exposure. Future investigations are advisable to justify the age-wise discrepancies found in the present study.

Updated knowledge on various strategies for prevention and disinfection against the transmission of Coronavirus Disease is required for every dental professional. Unless if there is an emergency situation, dental treatments should be given only to those patients with a COVID-negative laboratory test result and those with no symptoms (Azim et al., Citation2020). These can reduce the stress in them. Interventions to reduce occupational stress such as stress management training including relaxation methods like practicing of mindfulness also have to be implemented.

However, the study has some limitations. The present study did not consider the years of clinical practice and experience of the participants in teaching. Furthermore, the study was limited to the state of Kerala and similar studies need to be carried out on a global basis for ensuring generalizability.

5. Conclusion

The main purpose of this study was to find prevalence of perceived stress in dental faculties during COVID-19 pandemic. The study demonstrated the existence of perceived stress among the respondents. The study also indicated gender-wise and age-wise disparities in the level of perceived stress. Reasons for stress and the measures to overcome such problems need to be investigated. Further research in this area may help to suggest effective ways to overcome stress during such crisis. Periodic evaluation of stress using PSS10 or similar validated questionnaires is highly recommended and various stress management measures like exercise, meditation and mindfulness may be suggested for people with elevated perceived stress levels to overcome the potential threat to their mental health. Strict implementation of the measures to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection in the dental office, especially the initial virus screening and proper disinfection of work environment, can also reduce the stress drastically. All available resources must thus be utilised safely and efficiently.

Acknowledgements

I am extremely grateful to all the doctors for their co-operation during the data collection. Many thanks to Dr.Prasanth Viswambharan (Associate Professor) and Dr.A.R.Adhershitha (Assistant Professor), Government Dental College, Alappuzha, Kerala, India, for their overwhelming help throughout the research process.

Data availability statement

For accessing the data in public open-access repository please visit https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/82yg6g7cdz/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laxmi Suresh Babu

Primary author, Laxmi Suresh Babu is an Engineer by profession, later diversified her interest in Management. She is currently pursuing her Ph.D in Management in Noorul Islam University, India, and her research is on emotional intelligence of Dental Faculties. The pandemic motivated her to investigate into the perceived stress levels prevailing among her intended study population because elevated stress levels can affect the emotional intelligence level. Before this study, she has done enough literature reviews and the inferences were published as a review article titled “Emotional Brain-A Unique Intelligence at Work” in International Journal of Management. Dr.M.Janarthanan Pillai (Ph.D in Entrepreneurship) with 30 years of teaching experience and 45 publications is the HOD of Management Studies. Dr.K.A.Janardhanan (PhD in HRM and Public Administration), with 30 years of teaching experience and 120 publications, is the Dean of the department. Both of them have contributed towards critical revision of this article.

References

- Adams, J. G., & Walls, R. M. (2020). Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(15), 1439–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3972

- Adhershitha, A., Viswambharan, P., & Rodrigues, S. (2020). Awareness and attitude toward COVID-19 among the students of a rural tertiary care center and dental college: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Preventive and Clinical Dental Research, 7(4), 99. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpcdr.ijpcdr_46_20

- Azim, A. A., Shabbir, J., Khurshid, Z., Zafar, M. S., Ghabbani, H. M., & Dummer, P. M. H. (2020). Clinical endodontic management during the COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review and clinical recommendations. International Endodontic Journal, 53(11), 1461–1471. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13406

- Chan, S. F., & La Greca, A. M. (2020). Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine (pp. 1–2). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6439-6_773–2

- Cianetti, S., Pagano, S., Nardone, M., & Lombardo, G. (2020). Model for taking care of patients with early childhood caries during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113751

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Du, J., Dong, L., Wang, T., Yuan, C., Fu, R., Zhang, L., Liu, B., Zhang, M., Yin, Y., Qin, J., Bouey, J., Zhao, M., & Li, X. (2020). Psychological symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, 67, 144-145. General Hospital Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.011

- Flores, E., Tschann, J. M., Dimas, J. M., Bachen, E. A., Pasch, L. A., & De Groat, C. L. (2008). Perceived discrimination, perceived stress, and mental and physical health among Mexican-origin adults. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30(4), 401–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986308323056

- Gambarini, E., Galli, M., di Nardo, D., Miccoli, G., Patil, S., Bhandi, S., Giovarruscio, M., Testarelli, L., & Gambarini, G. (2020). A survey on perceived covid-19 risk in dentistry and the possible use of rapid tests. Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 21(7), 718–722. https://doi.org/10.5005/JP-JOURNALS-10024-2851

- Hamarat, E., Thompson, D., Zabrucky, K. M., Steele, D., Matheny, K. B., & Aysan, F. (2001). Perceived stress and coping resource availability as predictors of life satisfaction in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Experimental Aging Research, 27(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/036107301750074051

- Imran, E., Khurshid, Z., Adanir, N., Ashi, H., Almarzouki, N., & Baeshen, H. A. (2021). Dental practitioners’ knowledge, attitude and practices for mouthwash use amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 14, 605–618. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S287547

- Izzetti, R., Gennai, S., Nisi, M., Barone, A., Giuca, M. R., Gabriele, M., & Graziani, F. (2021). A perspective on dental activity during COVID-19: the Italian survey. Oral Diseases, 27(S3), 694–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13606

- Jiaqi, X., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., M., W., Lui, L., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population_ A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

- Khurshid, Z., Asiri, F. Y. I., & Al Wadaani, H. (2020). Human saliva: non-invasive fluid for detecting novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072225

- Lam, M. H.-B., Wing, Y.-K., Wai-Man Yu, M., Leung, C.-M., Ma, R. C., Kong, A. P., So, W., Yuk Fong, S. Y., & Lam, S.-P. (2009). Mental Morbidities and Chronic Fatigue in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Survivors. Arch Intern Med, 169(22), 2142–2147. PMID: 20008700. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.384

- Liu, S., Lithopoulos, A., Zhang, C.-Q., Garcia-Barrera, M., & Rhodes, A., R. (2020). 7 Personality and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic_ Testing the mediating role of perceived threat and efficacy _ Enhanced Reader.pdf. Elsevier Public Health Emergency Collection

- Meira, T. M., Paiva, S. M., Antelo, O. M., Guimarães, L. K., Bastos, S. Q., & Tanaka, O. M. (2020). Perceived stress and quality of life among graduate dental faculty. Journal of Dental Education, 84, 1099–1107. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12241

- Ong, J. J. Y., Bharatendu, C., Goh, Y., Tang, J. Z. Y., Sooi, K. W. X., Tan, Y. L., Tan, B. Y. Q., Teoh, H. L., Ong, S. T., Allen, D. M., & Sharma, V. K. (2020). Headaches associated with personal protective equipment – A cross-sectional study among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. Headache, 60(5), 864–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13811

- Paul, C. (2020). 24 dentistry and coronavirus.pdf. Britsh Dental Journal, 228(7), 503–505. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-1482-1

- Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy, 16(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561

- Resources, H. (2019). Role Stress in the Indian Industry : A Study of Banking Organisations Author (s): Farooq A. Shah Source : Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 38, No. 3 (Jan ., 2003), pp. 281–296 Published by : Shri Ram Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources. 38 (3), 281–296

- Sarfaraz, S., Shabbir, J., Mudasser, M. A., Khurshid, Z., Al-Quraini, A. A. A., Abbasi, M. S., Ratnayake, J., & Zafar, M. S. (2020). Knowledge and attitude of dental practitioners related to disinfection during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare, 8(3), 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030232

- Sarwar, H., Akhtar, H., Naeem, M. M., Khan, J. A., Waraich, K., Shabbir, S., Hasan, A., & Khurshid, Z. (2020). Self-reported effectiveness of e-learning classes during COVID-19 pandemic: A nation-wide survey of Pakistani undergraduate dentistry students. European Journal of Dentistry, 14(S1), S34–S43. https://doi.org/10.1055/s–0040–1717000

- Shaukat, N., Ali, D. M., & Razzak, J. (2020). Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: A scoping review. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5

- Sheldon, C., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. T He Social Psychology of Health, 31–67.

- Stawski, R. S., Sliwinski, M. J., Almeida, D. M., & Smyth, J. M. (2008). Reported exposure and emotional reactivity to daily stressors: the roles of adult age and global perceived stress. Psychology and Aging, 23(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.52

- Uzma, U., Ansari, A., Siraj, A., Khan, S., & Tariq, H. (2020). Expectations and Fears of doctors. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(COVID19-S4). https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.264 3

- Weinberg, A., & Cooper, C. (2011). Stress in turbulent times. Published by Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230306172

- Xu, X., Chen, P., Wang, J., Feng, J., Zhou, H., Li, X., Zhong, W., & Hao, P. (2020). Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Science China. Life Sciences, 63(3), 457–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5

- Zaheer, R., Khan, M., Tanveer, A., Farooq, A., & Khurshid, Z. (2020). Association of personal protective equipment with de novo headaches in frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Dentistry, 14(S1), S79–S85. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1721904