Abstract

The International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCWeB) uses a psychometric scale measuring the psychological well-being of children named the Children’s Worlds Psychological Well-Being Scale (CW-PSWBS). The CW-PSWBS has been used in 35 countries involved in the third wave of this international project, which includes a representative sample of West Java. This study aims to analyze the adaptation of the CW-PSWBS for use in Indonesia and validate the adapted Bahasa Indonesian version. A representative sample of 12-year-old students in West Java (N = 7,951; 49% boys; 51% girls) was obtained through cluster random sampling. The adaptation process involved several steps, including translation, a focus group discussion to test the legibility of the translated items, revising the translated items, piloting the revised-translated items, and back-translating. The next step involved testing the fit of the psychometric scale using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). A multi-group CFA was used to test the gender metric and scalar invariance of the scores. The results showed that the CW-PSWBS displays excellent fit and is a robust instrument for measuring psychological well-being in Indonesian children. Metric and scalar invariance were supported, meaning all statistics are comparable between genders, and different answering styles between boys and girls are not suspected.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study tests an instrument in Bahasa Indonesia to assess children’s well-being in a representative sample of West Java boys and girls. Results showed that this instrument is robust for measuring psychological well-being in Indonesian children and may be used by any Indonesian researcher or professional in the future to obtain reliable data.

1. Introduction

The International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCWeB or “Children’s Worlds”) is a pioneer, collecting solid and representative data worldwide in as many countries as possible on children’s lives and their perception and evaluation of their lives (Ben-Arieh, Citation2019; Casas, Citation2019). The ISCWeB project aims to improve knowledge about children’s well-being, including children’s voices in the research and policy discourses, and raise awareness among children, parents, policymakers, and the general public to enable better policies and services for children (Ben-Arieh, Citation2019; Casas, Citation2019). The first wave of ISCWeB was conducted in 14 countries in 2010–2011, and about 34,500 children participated in the study (Ben-Arieh, Citation2019). The second wave was conducted in 2013–2014 in 18 countries, and about 60,000 children participated (Ben-Arieh, Citation2019).

There were 35 countries involved in the third wave of ISCWeB between 2017–2018. They were Albania, Algeria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Croatia, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Malaysia, Malta, Namibia, Nepal, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Taiwan, UK (England), UK (Wales), and Vietnam (Rees et al., Citation2020). In the third wave of data collection, Children’s Worlds included four subjective well-being multi-item psychometric scales: the Children’s Worlds Subjective Well-Being Scale (CW-SWBS), the Children’s Worlds Domain-Based Subjective Well-Being Scale (CW-DBSWBS), the Children’s Worlds Positive and Negative Affect Scale (CW-PNAS), and the Children’s Worlds Psychological Well-Being Scale (CW-PSWBS). Casas and González‑Carrasco (Citation2021) analyzed the comparability of these scales among the 35 countries involved in the third wave of the Children’s Worlds project.

Indonesia was involved in the third wave of the ISCWeB in a collaborative work between Universitas Islam Bandung (Unisba) and UNICEF Indonesia, supported by Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional (BAPPENAS) and Biro Pusat Statistik (BPS) (Borualogo & Casas, Citation2019). This ISCWeB project in Indonesia is essential since this is the first work to investigate children’s well-being in the country and could bring a new perspective to policymakers toward improving children’s well-being.

One of these scales, the CW-SWBS, had already been adapted in the Indonesian context (Borualogo & Casas, Citation2019), suggesting it is a robust measure of subjective well-being of Indonesian children 8 to 12 years old (Borualogo, Citation2021; Borualogo & Casas, Citation2021a, Citation2021b, Citation2021c). The CW-SWBS has also been used for older middle school and high school students 13–18 years old (Bambang & Borualogo, Citation2021; Abidin & Borualogo, Citation2020; Hartita & Borualogo, Citation2021; Hidayah & Borualogo, Citation2021; Nuraripiniati & Borualogo, Citation2020; Rahma & Borualogo, Citation2021; Rakhmadianti et al., Citation2021; Ramadhanti & Borualogo, Citation2020; R. T. Firdaus & Borualogo, Citation2020) and children living in residential care (A. Firdaus & Borualogo, Citation2021; Ilhamsyah & Borualogo, Citation2020; Wargahadibrata & Borualogo, Citation2021). In the involvement with ISCWeB, Indonesia has not yet adapted the CW-PSWBS, and this is the aim of the present study.

This instrument was developed (Casas & González‑Carrasco, Citation2021) based on Ryff’s (Citation1995) concept of psychological well-being (PWB). There are multiple ways to conceptualize and measure well-being (Ryff et al., Citation2021). Ryff et al. (Citation2021) explained two approaches, hedonic and eudaimonic, where each approach focuses on a different aspect of well-being. The hedonic approach studies what makes life experiences pleasant and unpleasant, and the components include life satisfaction and positive and negative affect (Ryff et al., Citation2021). The eudaimonic approach emphasizes human potential to live well and fully; it includes six key dimensions that are fundamentally about well-being as challenged thriving (Ryff et al., Citation2021).

Ryff (Citation1995) proposed three theoretical guidelines for understanding the meaning of psychological well-being: developmental psychology, clinical psychology, and mental health. Life span developmental psychology explains developmental aspects of individuals that are conceived as progressions of continued growth across the life course. Clinical psychology offers multiple formulations of well-being, while mental health includes the formulation of positive criteria of mental health and positive function in later life (Ryff, Citation1995).

Based on these three theoretical perspectives, Ryff (Citation1995) constructed the key dimensions of psychological well-being: self-acceptance, positive relationships with other people, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. Self-acceptance consists of having a positive attitude toward oneself and being aware of one’s limitations (Ryff et al., Citation2021). Positive relationships with other people could be seen in how individuals seek to develop and maintain warm and trusting interpersonal relationships (Ryff et al., Citation2021). Autonomy regards a sense of self-determination and personal authority in which individuals sustain their individuality in diverse social contexts (Ryff et al., Citation2021). Environmental mastery is about the ability of the person to empower the environment to meet their needs and desires (Ryff et al., Citation2021). Individuals are also able to find meaning in their endeavors and challenges, which is known as another key dimension: purpose in life (Ryff et al., Citation2021). The last key dimension includes making the most of personal talents and capacities for personal growth (Ryff et al., Citation2021). These six dimensions, taken together, form PWB, which Ryff (Citation1995, p. 99) defined as “positive evaluations of one’s self and one’s life, a sense of continued growth and development as a person, the belief that life is purposeful and meaningful, the possession of good relationships with other people, the capacity to manage one’s life and the surrounding world effectively, and a sense of self-determination.”

The eudaimonic approach to measure well-being includes six key dimensions, fundamentally as challenged thriving (Ryff et al., Citation2021). Each key dimension (self-acceptance, positive relations with others, environmental mastery, autonomy, purpose in life, and personal growth) articulates different challenges individuals encounter as they strive to function positively (Ryff et al., Citation2021). Ryff’s (Citation1995) original scale of PWB for use in adults consists of 20 items per dimension and includes a total of 120 items. There are several versions of the scale with a diverse number of items: 84, 54, 42, and 18 items (Henn et al., Citation2016).

Studies have shown gender differences in certain aspects of PWB, particularly in the results of mental health studies (Ryff, Citation1995). Women consistently rate themselves higher on positive relationships with others compared to men. Women also tend to rate higher on personal growth than men. The other four aspects of PWB showed no significant differences between gender (Ryff, Citation1995).

In the third wave of ISCWeB involving 35 countries, the Cronbach’s alpha for CW-PSWBS was 0.84 for the overall 12-year-old age group using the pooled sample (Rees et al., Citation2020). Studies also showed that CW-PSWBS displays an excellent fit for using in-country analysis (Casas & González‑Carrasco, Citation2021). However, CW-PSWBS cannot be used to compare PWB of children between countries (Casas & González‑Carrasco, Citation2021; Nahkur & Casas, Citation2021).

2. Aim of the study

Indonesia has a national language that is used by all habitants in the entire country and the CW-PSWBS had not been adapted and validated in this language. Therefore, the aims of this study are twofold: to adapt the CW-PSWBS into the Indonesian context and to test the validity and reliability of the CW-PSWBS using a representative sample of Indonesian children about 12 years of age.

3. Methods

3.1. Samples

The ISCWeB project in Indonesia involved elementary students (N = 22,616) in grades 2, 4, and 6 from 27 districts in West Java Province. However, only children in grade 6 (N = 7,951; 49% boys; 51% girls) were administered the CW-PSWBS because its abstract wording made it too complex for younger children.

The study used stratified cluster random sampling, which included 267 schools. The stratification was applied based on type and rank of school, while the cluster was applied based on the 27 districts in West Java. The ten chosen schools in each district were stratified by public and private and religious-based and nonreligious-based schools. In each school, all students at grade 6 were participated in the study.

3.2. Ethical approval

The ethical approval was gained from the ethical committee at the at the Universitas Padjadjaran number 83/UN6.C1.3.2/KEPK/PN/2017. The research team also gained permission from the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Religion at the provincial level of West Java.

The written parent consent was obtained. Children were also informed that they were free to answer or not answer the questions, and their data would be treated confidentially.

3.3. Procedures

Self-administered data collection using paper and pencil was conducted in classrooms. A teacher and two skilled enumerators were present in every classroom during the data collection process to answer any questions that might arise.

3.4. The instrument

The Children’s Worlds Psychological Well-Being Scale (CW-PSWBS) is a six-item psychometric scale measuring psychological well-being (Casas & González‑Carrasco, Citation2021). The instruction is, “Please say how much you agree with each of the following sentences about your life as a whole.” The items are: (1) “I like being the way I am,” (2) “I am good at managing my daily responsibilities,” (3) “People are generally friendly towards me,” (4) “I have enough choice about how I spend my time,” (5) “I feel that I am learning a lot at the moment,” and (6) “I feel positive about my future.” The CW-PSWBS uses an 11-point scale from 0 to 10, where 0 = Do not agree (Sama sekali tidak setuju) and 10 = Totally agree (Sangat setuju).

3.5. Procedure of translating and adapting the scale

The process of adapting and validating the CW-PSWBS included several steps following guidance from F. Van de Vijver and Hambleton (Citation1996) and F. J. R. Van de Vijver and Poortinga (Citation2004) that had also been used for adapting the CW-SWBS (Borualogo & Casas, Citation2019) in Indonesia.

First, the research team learned about the blueprint of the scale and analyzed the meaning of each item in English. This first step included several online meetings and discussions with the Children’s Worlds team, developers of the CW-PSWBS. After fully understanding the meaning of each item, the research team translated the original English version of the CW-PSWBS, considering the Indonesian context and avoiding translating the items only literally.

In the second step, the research team conducted a focus group discussion with sixth grade students to discuss the translated scale and to test the legibility of the items. The research team checked children’s understanding of the instructions and the wording of the items. The research team also requested children’s suggestions on changing the wording when needed (Borualogo et al., Citation2019).

In the third step, the research team analyzed children’s suggestions for the wording of each item and carefully changed the wording based on the suggestions. The item “I feel that I am learning a lot at the moment,” which was translated into “Saya merasa bahwa saya sedang belajar banyak hal pada saat ini,” was understood by children as learning at school. Based on children’s suggestions, we changed the sentence into “Saya merasa bahwa saya belajar banyak hal saat ini,” which was back-translated into “I feel that I learn a lot of things these days.” The research team then revised the translated Indonesian version.

In the fourth step, the research team piloted this revised Indonesian version of the scale to sixth grade students (N = 139; 55.4% boys; 44.6% girls). The Cronbach’s alpha was .809.

In the fifth step, the piloted Indonesian version of the scale was sent to professional English editors who were not familiar with the scale. The professional English editors back-translated the piloted Indonesian version into English.

In the sixth step, the back-translated version of CW-PSWBS was sent to the Children’s Worlds coordinator team to be reviewed. The Children’s Worlds team reviewed the back-translated version, stated that the items in the back-translated version were similar enough to the original version, and approved it. The original English version, the Indonesian version, and the back-translated version of the CW-PSWBS can be found in the Appendix.

3.6. Data depuration

Following suggestions from Casas and González‑Carrasco (Citation2021), children who did not answer three or more items were excluded from the analysis. Scores of the children who did not answer one or two items were substituted by means of multiple imputations using regression as implemented by the SPSS25. For grade 6, 134 cases were excluded because of incomplete data.

3.7. Data analysis

To analyze the validity and reliability of the Indonesian version of the CW-PSWBS, the research team used Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Cronbach’s alpha. Multi-group CFA was also used to check for answering styles between genders to ensure there was no problem with gender comparability.

In the first step of data analysis, we assessed the validity of the factorial structure of the CW-PSWBS by testing different CFA models using AMOS23 with maximum likelihood estimation. The CFA was conducted using the pooled sample to test model fit. In the second step, a multi-group CFA was conducted to test measurement invariance across gender.

As recommended by Casas (Citation2017) and Casas and González‑Carrasco (Citation2021), the following fit indices have been adopted: the CFI (Comparative Fit Index), the RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), and the SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual). Following Arbuckle (Citation2010) and Byrne (Citation2010), fit indices resulting higher than .950 for the CFI and below .05 for RMSEA and SRMR were considered excellent.

To compare statistics across gender, the analysis required measurement invariance analysis. Three steps were followed: (1) configural invariance (unconstrained variables), (2) metric invariance (constrained factor loadings), and (3) scalar invariance (constrained factor loadings and intercepts). Metric invariance allows for a meaningful comparison of correlation and regressions, while scalar invariance allows for a meaningful comparison of the latent means (Savahl et al., Citation2020). When any constraint is added to a model, a change in the CFI of more than .01 is considered unacceptable (Chen, Citation2007; Cheung & Rensvold, Citation2001). Because SWB data usually depart from normality, the bootstrap method using maximum likelihood is used to compute standard errors.

4. Results

The comparison between the original English version of the scale, the Indonesian version and the English back-translation are presented in the Appendix.

Table presents descriptive statistics for each item by gender. The mean scores of the items were slightly higher for girls than for boys, except for the item “I have enough choice about how I spend my time.” The item “I am good at managing my daily responsibilities” displayed the lowest mean score for boys. Significant gender differences were observed on three items: “I like the way I am,” “People are generally pretty friendly towards me,” and “I feel that I am learning a lot at the moment.” All correlations between the items were above .36 and significant.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for CW-PSWBS

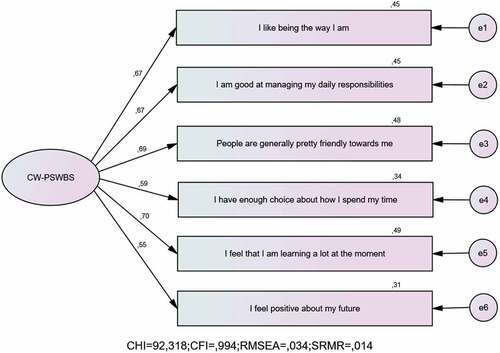

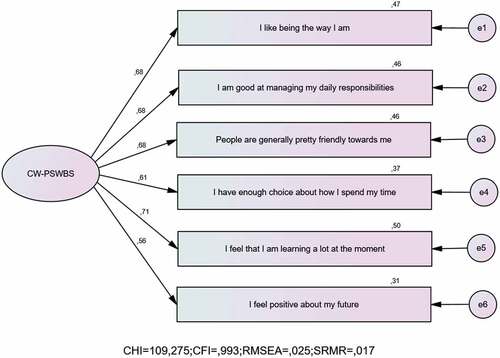

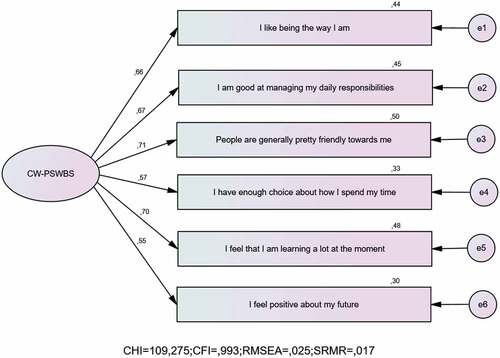

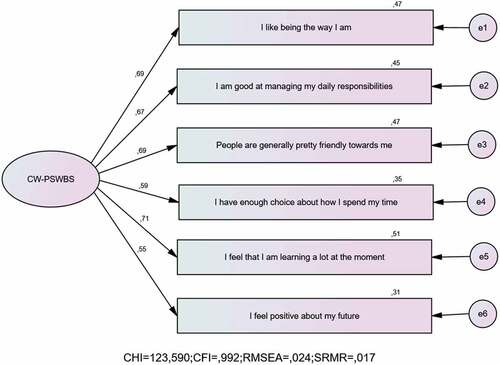

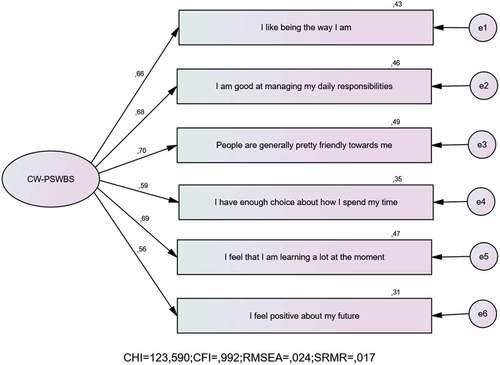

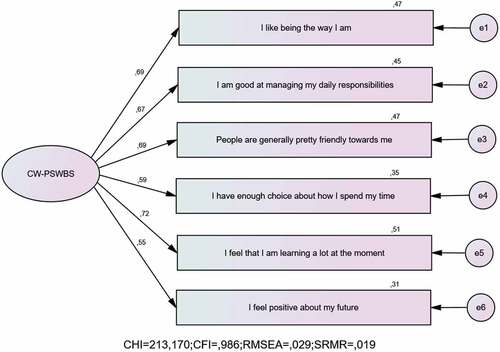

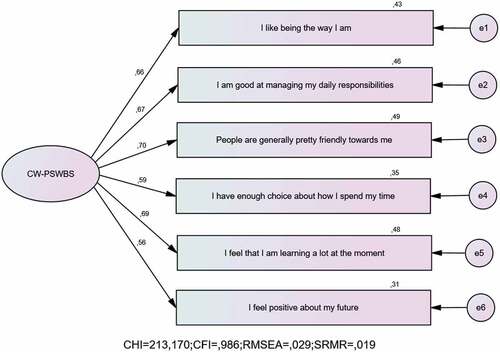

Table shows that the initial model with the pooled sample displays excellent fit, suggesting that the factorial structure is good. The multi-group unconstrained model (Model 2), the multi-group model with constrained loadings (Model 3), and the multi-group model with constrained loadings and intercepts (Model 4) all displayed excellent fit, and no statistics displayed a decrease larger than <.01 when any additional constraint is included. Therefore, results suggest that correlation, regressions, and mean scores are comparable among genders because no different gender answering styles have been identified. Cronbach’s alpha was .809.

Table 2. Fit statistics for the different models here analyzed

CFA using maximum likelihood estimation was run to test the fit of the pooled model and the multi-group models by gender. Results presented excellent fit (Table and figure ). Metric and scalar invariance were tested by constraining the factor loadings and intercepts and were supported by the results obtained because with any additional constraint, none of the indexes increased more than .01, suggesting there was no different answering style between genders (Table ). Model 2 for multi-group by gender unconstrained was presented in Figure (for girls) and Figure (for boys). Model 3 for multi-group by gender constrained loadings was presented in Figure (for girls) and Figure (for boys). Model 4 for multi-group by gender constrained loadings and intercepts was presented in Figure (for girls) and Figure (for boys).

Table displays the standardized regression weight using bootstrap for boys’ and girls’ models. Standardized estimates show adequate loadings for all items on the model by gender, ranging between .553 and .715 for girls and between .555. and .698 for boys. The effect of each item on the latent variable CW-PSWBS was higher among boys than among girls, except for item number 1 (“I like being the way I am”) and number 5 (“I feel like I am learning a lot at the moment”).

Table 3. Standardized Regression Weights, Constrained Loading, and Intercepts

5. Discussion

Studies on PWB using Ryff’s scale of PWB in Indonesia have mostly focused on adults (Dannisworo & Amalia, Citation2019) and used an extended version of the scale with 18 to 86 items (Hardjo & Novita, Citation2015; Rachmayani & Ramdhani, Citation2014). Studies on adolescents’ PWB in Indonesia also used an extended version of Ryff’s scale of PWB with 42 items (Nugroho, Citation2019). However, empirical studies in the eudaimonic approach are still scarce. The adaptation and validation of Ryff’s scale of PWB for use in the Indonesian context with an adolescent sample are still unclear, and the number of items is quite a lot.

Because of the abstract concept of the eudaimonic approach to measuring well-being among children, the ISCWeB developed six items of the CW-PSWBS based on Ryff’s (Citation1995) conceptualization of PWB to make them suitable for children age 12 years old. It is important to have brief validated scales available for cross-cultural research to allow more scales to be included in the questionnaires and avoid the children getting tired. The CW-PSWBS has been tested in wave 2 and wave 3 of the ISCWeB involving 35 countries. Results from wave 2 and wave 3 showed that the CW-PSWBS does work in each country to measure PWB of children 12 years old (Nahkur & Casas, Citation2021). Since Indonesia has been involved in the ISCWeB, it was necessary to adapt and validate the CW-PSWBS into Bahasa Indonesian.

Studies on children’s well-being in Indonesia have been increasing since Indonesia participated in the ISCWeB data collection. The CW-PSWBS was never used in studies in Indonesia before. Therefore, this study aims to validate CW-PSWBS for use in Indonesia. Through a careful process of adapting the scale following guidance from F. Van de Vijver and Hambleton (Citation1996) and F. J. R. Van de Vijver and Poortinga (Citation2004), the original English version of the CW-PSWBS was adapted into Indonesian. The back-translated version of the items showed similarity with the original version of CW-PSWBS and was approved by the Children’s Worlds team, developers of the original English version.

To validate the Indonesian version of the CW-PSWBS, we tested the scale using a representative sample of 12-year-old children in 27 districts in West Java with a large sample size (N = 7,951). Correlation between all items is significant. A CFA of CW-PSWBS using the pooled sample showed an excellent fit structure. Therefore, this version of the CW-PSWBS in Bahasa Indonesian can be used in a reliable and valid way to assess the PWB of Indonesian children.

Multi-group models were used to test metric and scalar factor invariance between genders by constraining factor loadings and intercepts. The results showed no different answering styles between boys and girls. Correlation, regressions, and means show to be comparable between the two genders.

Regression weights of the items of the CW-PSWBS on its latent variable are high and rather homogeneous for both genders. However, the highest observed regression weight is for the item “I feel like I am learning a lot at the moment” among girls, while among boys, it is for the item “People are generally pretty friendly towards me.” For Indonesian girls, attaining academic achievement is important to establish their position in society. In a patriarchal culture, Indonesian girls are not allowed to be dominant in society. Therefore, attaining good academic achievement becomes important in their lives and gives them a feeling of controlling their lives in the way society allows. Very frequently in Indonesian schools, students in the top/high rank of the class are girls. A study in Indonesia showed that female college students are more engaged in their learning process and conducting their work than male college students (Wijaya et al., Citation2020). For Indonesian boys, being accepted socially is especially important to show that they have many friends.

The lowest regression weights among both genders are for the item “I feel positive about my future” (Table ). For both genders, this lowest regression weight suggests that this item is less important than the others for the PWB of Indonesian children, probably because Indonesian children feel uncertain and negative about their futures. In a cross-country study comparing CW-PSWBS, “I feel positive about my future” also made the lowest contribution in six countries (Algeria, Italy, Malta, South Africa, South Korea, and Spain) of wave 2 of the Children’s Worlds survey (Nahkur & Casas, Citation2021).

Girls reported higher levels of PWB than boys for five out of six dimensions, the exception being “I have enough choice about how I spend my time,” but this difference is non-significant. Significant gender differences were observed in only three dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relationships, and personal growth (Table ). These significant differences may indicate diverse gender trajectories to achieve PWB in Indonesia. These results are aligned with Ryff et al.’s (Citation2021) findings on adult women, who rated higher than adult men on positive relationships and personal growth. Several studies on adult women and men showed consistent results that women rated themselves higher in positive relationships and tended to score higher on personal growth (Chraif & Dumitru, Citation2015; Matud et al., Citation2019; Sun et al., Citation2016). However, no previous studies have been found that identify gender differences for the PWB dimensions using adolescents’ samples.

Regarding the regression weights (Table ), the dimension of self-acceptance (“I like being the way I am”) and personal growth (“I feel that I am learning a lot at the moment”) appear to be more important for Indonesian girls than for Indonesian boys. Capacity for accepting themselves is important for girls, as well as continuing their personal development. As for Indonesian boys, viewing themselves as independent is important in that they also feel capable of taking active roles and getting what they need from the environment. Having a purpose in life and knowing the life direction is also more important for Indonesian boys than girls. Boys also perceive the importance of having positive relationships with others.

Gender differences between adults and adolescents should be investigated in more detail in the future. It is also important to investigate whether the PWB scores change over time as adolescents get older.

6. Conclusion

The CW-PSWBS has been adapted into the Indonesian context and showed excellent fit. Therefore, this psychometric scale can be used for research in Indonesia for children and adolescents 12 years old and older.

Hopefully, this study will also raise awareness among Indonesian researchers interested in conducting studies of children’s PWB to use the CW-PSWBS for their research.

6.1. Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations. Participants of this study were adolescents who go to school, and the study does not cover groups of adolescents who do not go to school, have been excluded from school, have special needs, or are home-schooled. Therefore, it might be interesting to include these groups of adolescents in future studies.

Although this study used a representative and large sample, it was conducted only in West Java. Future studies should include other provinces in Indonesia, using Bahasa Indonesian or local languages.

The CW-PSWBS has not been tested in longitudinal studies with adolescent samples. Therefore, having an adapted and validated brief version available for as many languages as possible opens new opportunities for future studies with adolescents to investigate the effect of age on the PWB.

Opree et al. (Citation2018) developed two versions of the Psychological Well-Being Scale for Children (PWB-c) based on Ryff’s (Citation1995) conceptualization of PWB, one with 24 items and another with 12 items designed to be used for children age 8 to 12. It might be interesting in the future to examine Indonesian children’s PWB using PWB-c (Opree et al., Citation2018) and to investigate the comparative psychometric properties of CW-PSWBS and PWB-c using Indonesian children’s samples.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to all enumerators who had helped on data collection and to all participating schools and children.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ihsana Sabriani Borualogo

Ihsana Sabriani Borualogo graduated from the Doctorate Program of Psychology at the Faculty of Psychology in Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. She is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Universitas Islam Bandung in West Java, Indonesia. Ferran Casas is PhD on Social Psychology of the University of Barcelona and senior researcher and Emeritus Professor of the University of Girona, Spain while at present he is Visiting Permanent Professor at the Universidad de Desarrollo (Chile) and at the Doctoral Program on Education and Society at Universidad Andrés Bello, Chile. Both of them are principal country investigators of the Children’s Worlds international research project (www.isciweb.org) supported by International Society for Child Indicators (ISCI) and by the Jacobs Foundation (Switzerland).

References

- Abidin, H. M., & Borualogo, I. S. (2020). Pengaruh kepuasan pertemanan terhadap subjective well-being pada siswa SMP korban perundungan. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 128–17. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/22329/pdf

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2010). IBM SPSS® Amos™ 19 User’s guide. Amos Development Corporation.

- Bambang, S. S., & Borualogo, I. S. (2021). Pengaruh interaksi dengan teman terhadap subjective well-being anak dan remaja di masa pandemi COVID-19. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 245–249. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/28297

- Ben-Arieh, A. (2019). The well-being of the world’s children: Lessons from the international survey of children’s well-being. In D. Kutsar & K. Raid (Eds.), Children’s subjective well-being in local and international perspectives. Statistikaamet (pp. 18–29) . https://www.stat.ee/sites/default/files/2020-07/Childrens_Subjective_Well-Being_in_Local_and_International_Perspectives.pdf

- Borualogo, I. S. (2021). The role of parenting style to the feeling or adequately heard and subjective well-being in perpetrators and bullying victims. Jurnal Psikologi, 48(1), 96–117. https://doi.org/10.22146/jpsi.61860

- Borualogo, I. S., & Casas, F. (2019). Adaptation and validation of the children’s worlds subjective well-being scale (CW-SWBS) in Indonesia. Jurnal Psikologi, 46(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.22146/jpsi.38995

- Borualogo, I. S., & Casas, F. (2021a). Subjective well-being of bullied children in Indonesia. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16(2), 753–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09778-1

- Borualogo, I. S., & Casas, F. (2021b). Subjective well-being of Indonesian children: A perspective of material well-being. Anima, 36(2), 204–230. https://doi.org/10.24123/aipj.v36i2.2880

- Borualogo, I. S., & Casas, F. (2021c). The relationship between frequent bullying and subjective well-being in Indonesian children. Population Review, 60(1), 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1353/prv.2021.0002

- Borualogo, I. S., Gumilang, E., Mubarak, A., Khasanah, A. N., Wardati, M. A., Diantina, F. P., Permataputri, I., & Casas, F. (2019). Process of translation of the children’s worlds subjective well-being scale in Indonesia. Proceedings of the Social and Humaniora Research Symposium (SoRes 2018). Bandung, West Java, Indonesia, 307, Atlantis Press, 180–183. https://doi.org/10.2991/sores-18.2019.42

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315757421

- Casas, F. (2017). Analysing the comparability of 3 multi-item subjective well-being psychometric scales among 15 countries using samples of 10 and 12-Year-Olds. Child Indicators Research, 10(2), 297–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9360-0

- Casas, F. (2019). Introduction to the special section on children’s subjective well-being. Child Development, 90(2), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13129

- Casas, F., & González‑Carrasco, M. (2021). Analysing comparability of four multi-item well-being psychometric scales among 35 countries using children’s worlds 3rd wave 10 and 12-year-olds samples. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1829–1861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09825-0

- Chen, F. F. (2007). The sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org.10.1080/10705510701301834

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2001). The effects of model parsimony and sampling error on the fit of structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 4(3), 236–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/%2F109442810143004

- Chraif, M., & Dumitru, D. (2015). Gender differences on wellbeing and quality of life at young students at psychology. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 180, 1579–1583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.310

- Dannisworo, C. A., & Amalia, F. (2019). Psychological well-being, gender ideology, dan waktu sebagai prediktor keterlibatan ayah. Jurnal Psikologi, 46(3), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.22146/jpsi.35192

- Firdaus, R. T., & Borualogo, I. S. (2020). Pengaruh pola asuh terhadap subjective well-being pada dua kelompok perundungan. Prosiding Psikologi, 6(2), 920–926. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/24689/pdf

- Firdaus, A., & Borualogo, I. S. (2021). Studi komparasi kepuasan pertemanan dan subjective well-being saat COVID-19 remaja panti asuhan di Bandung. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 327–333. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/28330/pdf

- Hardjo, S., & Novita, E. (2015). Hubungan dukungan sosial dengan psychological well-being pada remaja korban sexual abuse. Analitika, 7(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.31289/analitika.v7i1.856

- Hartita, F. Y., & Borualogo, I. S. (2021). Persepsi didengarkan secara adekuat terhadap subjective well-being di masa pandemic COVID-19. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 278–283. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/28313/pdf

- Henn, C. M., Hill, C., & Jorgensen, L. I. (2016). An investigation into the factor structure of the Ryff scales of psychological well-being. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 42(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v42i1.1275

- Hidayah, A. I., & Borualogo, I. S. (2021). Pengaruh relasi dalam keluarga terhadap subjective well-being anak dan remaja di masa pandemi COVID-19. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 272–277. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/28312/pdf

- Ilhamsyah, D. Y., & Borualogo, I. S. (2020). Pengaruh kepuasan pertemanan terhadap subjective well-being remaja panti asuhan. Prosiding Psikologi, 6(2), 230–238. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/22387/pdf

- Matud, M. P., López-Curbelo, M., & Fortes, D. (2019). Gender and psychological well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193531

- Nahkur, O., & Casas, F. (2021). Fit and cross-country comparability of children’s worlds psychological well-being scale using 12-year-olds samples. Child Indicators Research, 14(6), 2211–2247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09833-0

- Nugroho, Y. A. (2019). Hubungan antara dukungan sosial keluarga dengan psychological well-being pada narapidana anak di Lapas Klas 1 Kutoarjo. Cognicia, 7(4), 465–474. https://doi.org/10.22219/cognicia.v7i4.10218

- Nuraripiniati, N., & Borualogo, I. S. (2020). Pengaruh iklim sekolah terhadap subjective well-being siswa SMP di Kota Bandung. Prosiding Psikologi, 6(2), 159–164. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/22343/pdf

- Opree, S. J., Buijzen, M., & Van Reijmersdal, E. A. (2018). Development and validation of the psychological well-being scale for children (PWB-c). Societies, 8(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8010018

- Rachmayani, D., & Ramdhani, N. (2014). Adaptasi bahasa dan budaya skala psychological well-being. Prosiding Seminar Nasional Psikologi UMS, 253–268. https://hdl.handle.net/11617/6417

- Rahma, R. S., & Borualogo, I. S. (2021). Pengaruh persepsi rasa aman terhadap subjective well-being pada korban perundungan saudara kandung. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 266–271. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/28311/pdf

- Rakhmadianti, D., Kusdiyati, S., & Borualogo, I. S. (2021). Pengaruh resiliensi terhadap subjective well-being pada remaja di masa pandemi COVID-19. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 478–483. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/28407/pdf

- Ramadhanti, K., & Borualogo, I. S. (2020). Pengaruh persepsi rasa aman terhadap subjective well-being siswa SMP korban perundungan. Prosiding Psikologi, 6(2), 100–104. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/22306/pdf

- Rees, G., Savahl, S., Lee, B. J., & Casas, F. (2020). Children’s views on their lives and well-being in 35 countries: A report on the Children’s Worlds project, 2016–19. Children’s Worlds Project (ISCWeB). https://isciweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Childrens-Worlds-Comparative-Report-2020.pdf

- Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Direction in Psychological Science, 4(4), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772395

- Ryff, C. D., Boylan, J. M., & Kirsch, J. A. (2021). Eudaimonic and hedonic well-being: An integrative perspective with linkages to sociodemographic factors and health. In M. T. Lee, L. D. Kubzansky, & T. J. VanderWeele (Eds.), Measuring well-being: Interdisciplinary perspectives from the social sciences and the humanities (pp. 92–135). Oxford Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197512531.003.0005

- Savahl, S., Adams, S., Florence, M., Casas, F., Mpilo, M., Sinclair, D. L., Manuel, D., & Gugliandolo, M. C. (2020). Afrikaans adaptation of the children’s hope scale: Validation and measurement invariance. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1853010. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1853010

- Sun, X., Chan, D. W., & Chan, L. K. (2016). Self-compassion and psychological well-being among adolescents in Hong Kong: Exploring gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06011

- Van de Vijver, F., & Hambleton, R. K. (1996). Translating tests: Some practical guidelines. European Psychologist, 1(2), 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.1.2.89

- Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Poortinga, Y. H. (2004). Conceptual and methodological issues in adapting tests. In Hambleton, R. K., Merenda, P. F., Spielberger, C. D., (Eds). Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment (pp. 51–76). Psychology Press. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781410611758-7/conceptual-methodological-issues-adapting-tests-fons-van-de-vijver-ype-poortinga

- Wargahadibrata, R. M. M., & Borualogo, I. S. (2021). Pengaruh hubungan anak dan pengasuh terhadap subjective well-being anak panti asuhan. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 621–627. http://karyailmiah.unisba.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/28516/pdf

- Wijaya, T. T., Ying, Z., & Suan, L. (2020). Gender and self-regulated learning during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Jurnal Basicedu, 4(3), 725–732. https://doi.org/10.31004/basicedu.v4i3.422

Appendix

The English version and the Indonesian version of the CW-PSWBS Psychometric Scale