Abstract

Disconnection from education and employment in youth termed Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET) has global attention. Major societal economic consequences and detrimental individual consequences follow disconnection. On the one hand, mental health problems are recognized as essential factors in disconnection, and on the other hand, youth clients within social welfare services face re-integrative initiatives with a vocational perspective. Psychosis and NEET are strongly associated with young help seekers inside mental healthcare services. In this systematic review, we investigate the occurrence of symptoms of psychosis among NEET status youth outside mental healthcare services to clarify if occurrence corresponds to the findings of NEET among help seekers with psychosis inside mental healthcare services. Based on literature search in the six databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Web of Science, SocIndex and Cochrane Library for NEETs measured for psychosis, we present findings from a narrative synthesis of two included studies and a total of 179 included participants. Our findings demonstrate sparse literature describing psychosis among NEETs, contrasting findings within mental healthcare settings. The results point to a research gap. Further research exploring unrecognized mental health needs with the focus of severe mental disorders as psychosis among the NEET population is needed. Joint interventions of welfare benefit system and mental health service are recommended to evolve initiatives for prevention and integration of the NEETs.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Major societal economic consequences follow disconnection from education and employment in the general youth population which globally is a societal challenge. Social disability is a hallmark symptom in schizophrenia and is suggested to be present in the initial phase of the disorder before more obvious psychopathology. A high prevalence of Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET) status, has been reported among first-episode psychosis samples, suggesting a connectedness between the vocational disengagement in youth and severe mental health problems. In this article, we report findings from reviewing the occurrence of psychosis among the NEET population. The results of the review reveal sparse knowledge of the occurrence of psychosis among the NEET population. These findings contrast the evidence found within mental healthcare settings of a high prevalence of NEET, among youth with psychosis, and point to a research gap with a need for further investigation of severe mental disorders among the NEET youth.

1. Introduction

Youth disconnection in transition from education to work-life has global attention (Benjet et al., Citation2012; Eurofound, Citation2012; Gutierrez-Garcia et al., Citation2018; Mendelson et al., Citation2018).

Young people failing to meet societal demands and facing exclusion from central socializing institutions face considerable individual consequences if not reintegrated (Bäckman & Nilsson, Citation2016; Co-operation OfE and Development, Citation2012). Further, lack of reintegration results in major economic consequences for society (Eurofound, Citation2012; Schultz-Nielsen & Skaksen, Citation2016). The term “Not in Education, Employment or Training” (NEET) in recent years has been adopted from economic policy literature into the scientific field of psychosocial research (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Benjet et al., Citation2012). NEET defines a group of young people disengaged from society, not in education, employment or training. The acronym covers a heterogenic group facing varying difficulties and being in different situations (Yates & Payne, Citation2007). Country context differences including cultural expectations of normative trajectories, opportunities in education and work-life and perceived reasons for being NEET are considered relevant when looking at NEET from a global perspective (Gutierrez-Garcia et al., Citation2018, Citation2017).

Current research has primarily been considering the societal economic loss with a considerable part of a generation standing outside the labour market (Eurofound, Citation2012). In the NEET population, nevertheless a seemingly heterogenic group, mental ill health is a central topic of concern and repeatedly recognized to play a vital role in youth disengagement across countries (Benjet et al., Citation2012; Power et al., Citation2015; Rodwell et al., Citation2018; Symonds et al., Citation2016). Young adults who receive temporary welfare benefits and are considered NEETs are found to report psychological distress as the most prevalent health problem (Sveinsdottir et al., Citation2018). Up to 70% of all new disability benefit recipients among young adults and across countries claim mental health problems as reasons for the economic support need (Co-operation OfE and Development, Citation2012). Association of NEET status and common mental disorders is reported consistently in cross-sectional and longitudinal designs in population-based studies (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Basta et al., Citation2019; Berry et al., Citation2019; Gariepy & Iyer, Citation2019; Symonds et al., Citation2016).

Identification of co-existence of disconnection from education and work-life among help seekers in mental health care has been suggested as a risk marker in mental illness trajectories (Cross et al., Citation2017). Help seekers in primary mental healthcare service in Australia (headspace) have been shown to be part of the NEET status youth in 19% of cases (O’Dea et al., Citation2014).

Psychosis and sign of severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia often emerge in adolescence, thereby affecting the youth population (Hafner & Nowotny, Citation1995; Kessler et al., Citation2007; Thomsen, Citation1996; Volkmar, Citation1996). Parallel to the identification of the crucial issues of the NEET youth, research in early intervention psychosis has identified disconnection from education and work alongside and preceding emergence of illness (Addington & Addington, Citation2005; Stilo et al., Citation2017). Significant rates of NEET status at mental healthcare service entry have been identified across countries among youth experiencing a first episode psychosis (Cotton et al., Citation2017; Maraj et al., Citation2019; Turner et al., Citation2009). In a review, it was reported that 40 to 50% at first contact to early psychosis services were not in school or employed and the rate rose from 60 to 70%, had there been a long prodrome (Marwaha & Johnson, Citation2004).

In addition, it has been suggested that the economic inactivity in young adults often precedes recognition of mental illness and that there is a scarcity of screening or monitoring within the economically inactive population for these emerging problems (Scott et al., Citation2013).

The NEET youth has been stated to be a priority area for labour market policy, with employment and earnings found to be the most commonly measured intervention outcomes (Mawn et al., Citation2017). The key concepts for inactive young adults in the Nordic countries, which are characterized by extensive welfare systems and little economic inequality, are activation strategies with activity as education and alternatively work-related activity (Reneflot & Evensen, Citation2014). Consequently, the NEET population is dealt with primarily within the welfare benefit system, with the focus on vocational reintegration and not with the focus of mental health needs.

As a result, and in addition to findings in first-episode psychosis literature with high rates of NEET status in help-seeking young adults, it is hypothesized that a subgroup within the NEET population in fact has severe mental health problems, as symptoms of psychosis, which requires attention. We aimed to identify the occurrence of psychosis among the NEET population outside mental healthcare services and to identify if the presence of symptoms of psychosis could be quantified among the NEET status youth.

2. Method

The Systematic Review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al., Citation2009). The systematic review protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (ID: CRD42020161689; (CitationPROSPERO).

2.1. Study selection

All types of studies were included with no restriction of study design and independently of presenting a comparator or control group.

Inclusion was restricted to studies presented in English, and the publication date of studies to be included was restricted to year 1999 and onwards, as the term NEET was first presented in a report by the Social Exclusion Unit in Great Britain in the year 1999 (Unit, Citation1999).

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were conducted on NEET-status youth, defined as not in education, employment or training, with no limitations of duration of state and no restriction of scale or criteria used for the measure. The term NEET did not need to be used explicitly. Examples of descriptions where the term NEET was not used and where the study population was still considered relevant for inclusion in the review were as follows: “Not in school or employment” or “vocational and academic disengaged”. Inactivity in both education and employment should be described to meet eligibility criteria for inclusion.

Youth was defined as an age range from 16 to 34 years old, and studies were considered eligible for inclusion if more than half of the population was in this age range or if the terms youth or young adults were used explicitly to describe the study population, then as defined by the authors.

To meet eligibility for inclusion, measure of psychosis had no restriction of quality or methodology used for the measure. The measure could be symptoms described as psychosis by the authors or an allocated diagnosis of any recognized diagnostic criteria or diagnoses systems and included the diagnostic schizophrenic spectrum psychosis, affective psychosis and substance-induced psychosis.

Studies were excluded if the population of NEET was found in samples of patients in mental healthcare settings or samples of patients suffering from psychosis. Additionally, studies were excluded if a measure of psychosis was not assessed or addressed.

2.3. Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Web of Science, SocIndex and Cochrane Library up to June 8, 2020. The complete search strategy is available on PROSPERO. The search strategy combined terms relating to or describing the condition of NEET and severe mental disorder with database-specific filters and conducted using “AND/OR” operators. The search strategy combined the terms and keywords related to three clusters: youth, disengagement and psychosis. Reference lists of eligible studies and review articles were searched to identify studies that met inclusion criteria. Grey literature was sought by use of the internet resource Google Scholar.

The titles and abstracts of identified records were exported into the reference citation manager Endnote and imported into the data management software Covidence and duplicates were removed (CitationCovidence systematic review software). Two reviewers carried out the title and abstract screening followed by full-text screening independently (LL, JBF/LSB). Disagreement over the eligibility of studies was resolved by consensus through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer where consensus was not reached.

2.4. Data extraction and synthesis

Authors were contacted in cases where required data were not reported to clarify if data meeting inclusion criteria could be supplied. In all, authors of 16 records were contacted and three authors replied to the query, and all were unable to provide additional data.

Two reviewers extracted data independently. A data extraction form based on the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group’s data extraction template was used. The summary measures were not restricted and prevalence rates were used. Risk of bias in individual studies was assessed using the AXIS appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (Downes et al., Citation2016) and The Newcastle-Castle Ottawa Scale for case–control studies (Wells et al.,). Due to the absence of data examining the strength of the relationship between NEET status and psychosis and heterogeneity in the included studies, a meta-analysis could not be performed. Accordingly, a narrative synthesis was provided.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

A total of 6135 records were retrieved. 1402 duplicates were removed, and after title and abstract screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria, 183 records were full-text screened. Two studies fulfilled eligibility criteria for inclusion in the review; the PRISMA diagram is displayed in Figure .

3.2. Description of included studies

The two included studies were both conducted in western countries and published in 2010 and 2018, respectively.

Reissner et al. included 165 participants in a cross-sectional study design (Reissner et al., Citation2011). Ramsdal et al. used a qualitative and case–control design and included seven participants in both the case and the control group, with the control group consisting of college students (Ramsdal et al., Citation2018).

Study populations of the included studies of Reissner et al. and Ramsdal et al. were not explicitly termed NEETs, nevertheless fulfilled criterion as NEET populations with an age range of 16–25 and 18–25 years, respectively, and both studies recruited participants from clients in public welfare systems and dependent on welfare benefits. Additionally, Ramsdal et al. described the study population as “Long-term dropout from school and work” and states in the thesis of the first author that “None of them was currently employed in regular jobs or re-enrolled in regular high school programs” (Ramsdal, Citation2018). Reissner et al. likewise describes the study population as “failure in the transition periods from adolescence to adulthood and from school to work”. Reissner et al. recruited participants in a vocational centre and Ramsdal et al. in The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration.

The participants in Ramsdal et al. were neither in school nor in regular employment 2 to 5 years after dropout of high-school. Reissner et al. did not have a duration of disengagement as a criterion. The participants were on average 19 (SD 2.2) years old when first contacting the vocational service due to unemployment and had an average age of 21 (SD 2.1) years at participation in the study; see study characteristics in Table .

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

The included studies described mental health problems among disengaged young adults, with both studies investigating mental health problems by in-person interview using validated instruments screening for mental disorders according to DSM-IV/ICD-10 diagnostic manuals. Reissner et al. had psychiatric diagnoses as outcome measures, whereas the outcome in Ramsdal et al. was dropout among cases with mental disorders as exposure. Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers —psychologists or psychiatrists.

The diagnostic assessment in Reissner et al. was conducted through four sessions with the use of the instruments Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-I and SCID-II), with the focus of axis-I syndromes and axis-II personality disorders. The measure of psychosis was fulfilling DSM-IV diagnoses schizophrenia and other psychotic disorder according to SCID-I.

Ramsdal et al. investigated present mental disorder by using the screening tool Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) at one session described to account for about a 35-min interview. The measure of psychosis was assessed by screening questions for psychotic disorder according to the instrument.

3.3. Outcome of psychosis in the included studies

In all, Reissner et al. reported psychosis by description of assessment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorder among five participants (3%).

Ramsdal et al. did not report any participants to have psychosis, neither in the case group nor in the control group, see, Table .

Table 2. Interviews and measure of psychosis in included studies

3.4. Additional study findings

Overall, both studies reported a high prevalence of mental disorders when assessed by the instruments used. Reissner et al. reported criteria fulfilled for mental disorders according to DSM-IV in 98% of the 165 included participants. Among these, an overweight of externalizing disorders was found with 58.2% of the disengaged young adults reported to meet diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder when assessed with SCID-II.

In Ramsdal et al. in all, 13 diagnoses were found present among the seven disengaged participants, with five of the disengaged participants fulfilling criteria for more than one axis-I mental disorder. Four of the seven interviewed disengaged young adults were described to report the mental health problems to play a significant part in the school dropout events.

3.5. Quality assessment

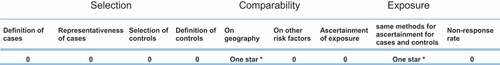

Assessment of risk of bias in individual studies showed a risk of selection bias in the included studies. One star was assigned to Ramsdal et al. in the exposure area and no stars in selection and comparability areas (Wells et al.,), see, Figure . In Reissner et al., there was an additional risk of information bias, as 49 persons were excluded after inclusion due to missing follow-up, see Figure .

4. Discussion

After a systematic literature search, only two studies were eligible for inclusion in our review. There was heterogeneity in designs and outcome measures in the included studies. Reissner et al. found the prevalence of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders among the 165 disengaged young adults recruited from a job counselling centre to be 3%. Ramsdal et al. did not identify psychotic disorder among participants investigated for mental disorders, neither in the study population of long-term school dropout young adults nor in the control group of college students. Both included studies pointed to mental health problems as central factors of being NEET.

The design of Ramsdal et al. was overall qualitative, and the case–control study had a small sample size not fit for statistical comparison (Ramsdal et al., Citation2018). As a result, no quantitative conclusions can be drawn from not finding psychosis among the NEET population in the study by Ramsdal et al. The prevalence of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders of 3% identified in the study of Reissner et al. is equivalent to the prevalence in community samples (Van Os et al., Citation2009; Wittchen et al., Citation2011). Yet, Reissner et al. did not include a comparison group in the study, and the assessed mental health problems among the disengaged youth could not be compared to a non-NEET status counterpart.

Both included studies identified a difficulty of recruitment in the group of disengaged youth.

Ramsdal et al. recruited participants through a contact person at the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration, and due to no descriptions of the total sample of clients eligible of participation, it was unclear whether the group of disengaged young adults interviewed was representative to the population of clients in the service (Ramsdal, Citation2018).

Likewise, Reissner et al. recruited the NEET group within the public welfare system in a vocational service by referral from case managers. The case managers identified participants who they suspected to require mental health attention, which constituted a highly selected study population stated not to be representative of the total group of young adults seen in the vocational centre.

Taken together, recruitment of the study populations in the included studies depended on assessment by public welfare caseworkers. Hence, it cannot be ruled out that selection of participants by non-mental health professionals might influence the findings of mental health issues.

In both studies, the measure of psychosis was represented as part of interviews with broad diagnostic screening and was not the focus of either study. Reissner et al. identified an overweight of externalizing disorders, a distribution of mental disorders that cannot be substantiated from other studies investigating mental disorders among NEET youth. One explanation for the notable outcome could be the use of the SCID-II interview, which to our knowledge, has not been used in the literature as an instrument to explore mental health problems among NEET youth. Accordingly, there could be a methodological factor attributing to the differing results found in Reissner et al. when compared to other NEET population studies; the identification of a specific diagnostic group could be a result of the use of an instrument designed with this diagnostic focus (Michael, Citation1997).

The measure used in Ramsdal et al. to evaluate mental disorders was based on a brief structured instrument, which might not be suitable for the identification of symptoms of emerging psychosis (Nordgaard et al., Citation2012).

Methodological limitations in detecting psychosis by the instruments used in the included studies could have affected the findings in relation to our hypothesis. Nevertheless, disregarding the methodological considerations, the results were limited in the included studies as were the overall identified studies concerning the topic of psychosis among NEET youth,and the hypothesis of the presence of symptoms of psychosis if searching among the inactive youth outside mental healthcare setting could not be confirmed in the present study.

In the psychiatric research field of first-episode psychosis, high prevalence of NEET status among young adults experiencing first-episode psychosis is evident and well described (Cotton et al., Citation2017; Maraj et al., Citation2019; Turner et al., Citation2009). Hence, there seems to be a paradox in the evidence of the high prevalence of NEET status among help seekers in mental healthcare setting experiencing psychosis and the absence of literature describing the opposite directionality association within the NEET youth outside mental healthcare setting.

The majority of studies exploring mental health issues among NEET youth are population-based studies using acknowledged instruments adapted to be used in surveys as self-reports or using structured interviews to screen for disorder groups, and the interviews are often carried out by non-clinician researchers (Baggio et al., Citation2015), Berry et al., Citation2019). This frame of research could be questioned in its ability to explore severe psychopathology as psychosis (Nordgaard et al., Citation2019; Stanghellini et al., Citation2012).

Consequently, there could be an overall methodological inability to identify symptoms of psychosis among community samples of the NEET population. This inability could explain the sparse literature describing severe mental disorders among NEETs.

Prevention and reintegration initiatives of the NEET group are of great societal interest (Eurofound, Citation2017), and therefore identification of causal explanations of NEET status has repeatedly been a topic of interest in the research field (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Fergusson et al., Citation2001). A causal discussion occurs both in unemployment and focused NEET literature (Scott et al., Citation2013). In longitudinal studies, NEET status in young adults is shown to be associated with mental disorder in childhood and adolescence, with the primary variables of mental disorders being common mental disorders, substance use and conduct disorder (Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Power et al., Citation2015; Rodwell et al., Citation2018). In addition, studies have found concurrent mental health problems of mood disorders and substance use disorder in NEET status young adults even when controlling for childhood and adolescent mental health problems (Gutierrez-Garcia et al., Citation2017) and for pre-existing mental health vulnerability (Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Sellstrom et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, investigation of the opposite causal direction has shown an increased risk of being admitted to hospital due to depression 1 year following registration as economically inactive young adult compared to the economically active young adults (Sellstrom et al., Citation2011). In summary, a bidirectional or multifactorial causal explanation seems to remain in the association of NEET and mental health problems (Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, mental health attention seems crucial to support the transition into work or further education in the NEET population.

The primary professionals in contact with a vulnerable group of young adults in need of mental health attention being case managers in vocational counselling services lead to the concern that young people, with the central problem of mental ill health, are met by caseworkers with the focus of vocational support, unequipped to identify the mental illness among the NEET population. Integration of treatment and vocational rehabilitation among young adults with recognized severe mental disorders has shown effective in vocational recovery after a first-episode psychosis with the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) approach (Killackey et al., Citation2019; Nuechterlein et al., Citation2020). More studies have found evidence that there is a motivation for vocation among people experiencing first-episode psychosis (Rinaldi et al., Citation2010), even in societies characterized by generous welfare systems, as in Scandinavian countries, where the financial incentive might be limited (Christensen et al., Citation2019; Gammelgaard et al., Citation2017). Reissner et al. suggest the approach of “case-related feedback” to enhance insight of psychiatric perspective of individuals seen primarily in vocational services (Reissner et al., Citation2011), thereby using interdisciplinary integration alike the Individual Placement and Support approach.

A high proportion of NEET status in first-episode psychosis can be accounted for by the symptoms in the early phases of psychosis of functional deterioration with changes in engagement in the surroundings of the patient, ability to maintain social functioning and academic decline (Hafner et al., Citation1999; Larsen et al., Citation2004). The hardship in capturing young adults with psychosis among NEETs could be the discrete positive clinical symptomatology in the early phase of illness when social decline presides what is more obvious psychopathology in psychosis (Bowman et al., Citation2020). Functional impairment in adolescents experiencing state 0–1a in the clinical stating model of risk states of mental disorders are seen to affect educational attainment and school dropout and is hypothesized to be linked to risk states of psychosis (Bowman et al., Citation2020). Likewise, identified elevated depressive score level in co-occurrence with NEET is suggested to be a risk factor for the emergence of serious mental health problems (Berry et al., Citation2019), and reporting anxiety and depression in the NEET population could be seen as important warning signs or as risk factors of psychosis (Hafner et al., Citation1999). Transition to psychosis in a high-risk sample has shown a significantly greater decline in social role function in the year prior to help-seeking, measured as performance and amount of support needed in one’s specific role (i.e., school, work), compared to the young adults who did not undergo transition (Carrion et al., Citation2019). Additionally, NEET status has been identified as a predictor of transition to psychosis (Cross et al., Citation2017).

NEET as well as an interaction between unemployment and social isolation has been found to be associated with prolonged duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode psychosis (Iyer et al., Citation2018; Reininghaus et al., Citation2008; Turner et al., Citation2009). Not addressing symptoms of psychosis can have crucial consequences for the clinical course, with empirical evidence of symptom complexity and poor prognosis to be related to the duration of untreated psychosis (Marshall et al., Citation2005). Hence, early identification and treatment of psychosis are paramount (Scott et al., Citation2013).

Vague causational explanations and insufficient understanding of the psychopathological quality and severity of mental health problems among NEETs make focus for prevention and initiatives for reintegration difficult (Scott et al., Citation2013), and additionally, a dearth of research examining mental health outcomes in intervention studies of NEETs has been identified (Mawn et al., Citation2017).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This systematic review has several strengths. We followed the PRISMA guidelines and we registered the protocol in PROSPERO when conducting this systematic review (Liberati et al., Citation2009). We conducted extensive searches of relevant databases. Two review authors, working independently, selected trials for inclusion and extracted data. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with team members. We assessed the risk of bias in included studies by using the AXIS appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies and The Newcastle-Castle Ottawa Scale for case–control studies. As a result, we think our approach has led to the best possible gathering of relevant literature on the topic.

The limitations of the review was the limited number of studies found eligible for inclusion after the systematic literature search. The studies were heterogenic in design, and the data was not fit for conducting a meta-analysis. Accordingly, the results are based on a narrative synthesis. Recruitment of NEET young people for comprehensive investigation is challenging (Berry et al., Citation2019; Ramsdal et al., Citation2018; Russell, Citation2013). As a result, there was a risk of selection bias in both included studies, which was reported by the authors and could have consequences for the interpretation of the results.

In conclusion, evidence from first-episode psychosis literature in regards to a high prevalence of NEET status in this group adheres to the hypothesis of the presence of psychosis among NEET youth. Nevertheless, this assumption could not be confirmed by the existing literature. The evidence of social impairment in the illness trajectory of psychosis contrasts the absence in the literature field, which points to a research gap.

The existing evidence of mental health problems among the NEET population leads to a concern that caseworkers with the focus of vocational support are the primary professionals in contact with the disengaged youth and unequipped to identify untreated severe mental disorder.

Causal considerations point to a bidirectional association of NEET status and mental health problems, and Individual Placement and Support literature has shown evidence of an effect of integrative vocational rehabilitation in mental health care setting in first-episode psychosis.

Further research exploring unrecognized mental health needs with the focus of severe mental disorders as psychosis among the NEET population is needed. Intervention studies with an integrative approach of welfare benefit system and mental health care system will be of greatest importance to evolve initiatives of prevention and reintegration of the NEET population.

Availability of data and material

The complete search strategy is available on PROSPERO ID: CRD42020161689. The data retrieved from Covidence are available from corresponding author upon request.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Joshua Buron Feinberg (JBF) for his contribution to the work with design of the study and for his contribution in the record screening process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Line Lindhardt

Line Lindhardt is an MD, fellow in psychiatry, and PhD candidate affiliated to the University of Copenhagen. The scope of her research is early detection of psychosis in youth. Her research focuses on exploring the link between social disconnection in the general youth population and the social disability in early phase psychosis.

References

- Addington, J., & Addington, D. (2005, June 15). Patterns of premorbid functioning in first episode psychosis: Relationship to 2-year outcome. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112(1), 40–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00511.x

- Baggio, S., Iglesias, K., Deline, S., Studer, J., Henchoz, Y., Mohler-Kuo, M., & Gmel, G. (2015, January 27). Not in education, employment, or training status among young Swiss men. Longitudinal associations with mental health and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), 238–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.006

- Basta, M., Karakonstantis, S., Koutra, K., Dafermos, V., Papargiris, A., Drakaki, M., Tzagkarakis, S., Vgontzas, A., Simos, P., & Papadakis, N. (2019). NEET status among young Greeks: Association with mental health and substance use. Journal of Affective Disorders, 253 (2019–06–15) , 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.095

- Benjet, C., Hernandez-Montoya, D., Borges, G., Méndez, E., Medina-Mora, M. E., & Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. (2012, July 27). Youth who neither study nor work: Mental health, education and employment. Salud Pública de México, 54(4), 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0036-36342012000400011

- Berry, C., Easterbrook, M. J., Empson, L., & Fowler, D. (2019, March 30). Structured activity and multiple group memberships as mechanisms of increased depression amongst young people not in employment, education or training. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(6), 1480–1487. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12798

- Bowman, S., McKinstry, C., Howie, L., & McGorry, P. (2020, February 07). Expanding the search for emerging mental ill health to safeguard student potential and vocational success in high school: A narrative review. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(6), 655–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00344-0

- Bäckman, O., & Nilsson, A. (2016). Long-term consequences of being not in employment, education or training as a young adult: Stability and change in three Swedish birth cohorts. European Societies, 18(2), 136–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2016.1153699

- Carrion, R. E., Auther, A. M., McLaughlin, D., Olsen, R., Addington, J., Bearden, C. E., Cadenhead, K. S., Cannon, T. D., Mathalon, D. H., McGlashan, T. H., Perkins, D. O., Seidman, L. J., Tsuang, M. T., Walker, E. F., Woods, S. W., & Cornblatt, B. A. (2019). The global functioning: social and role scales-further validation in a large sample of adolescents and young adults at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 45(4), 763–772. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby126

- Christensen, T. N., Wallstrom, I. G., Stenager, E., Bojesen, A. B., Gluud, C., Nordentoft, M., & Eplov, L. F. (2019, September 5). Effects of individual placement and support supplemented with cognitive remediation and work-focused social skills training for people with severe mental illness: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(12), 1232–1240. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2291

- Co-operation OfE and Development. (2012). Sick on the job?: Myths and realities about mental health and work (p. 212). OECD.

- Cotton, S. M., Lambert, M., Schimmelmann, B. G., Filia, K., Rayner, V., Hides, L., Foley, D. L., Ratheesh, A., Watson, A., Rodger, P., McGorry, P. D., & Conus, P. (2017). Predictors of functional status at service entry and discharge among young people with first episode psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(5), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1358-0

- Covidence systematic review software. Veritas health innovation. www.covidence.org.

- Cross, S. P. M., Scott, J., & Hickie, I. B. (2017, September 30). Predicting early transition from sub-syndromal presentations to major mental disorders. BJPsych Open, 3(5), 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.117.004721

- Downes, M. J., Brennan, M. L., Williams, H. C., & Dean, R. S. (2016, December 10). Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open, 6(12), e011458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

- Eurofound. (2012). NEETs – Young people not in employment, education or training: Characteristics, costs and policy responses in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Eurofound. 2017. Long-term unemployed youth: Characteristics and policy responses, Publications Office of theEuropean Union.

- Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Woodward, L. J. (2001, July 7). Unemployment and psychosocial adjustment in young adults: Causation or selection? Social Science & Medicine, 53(3), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00344-0

- Gammelgaard, I., Christensen, T. N., Eplov, L. F., Jensen, S. B., Stenager, E., & Petersen, K. S. (2017). “I have potential’: Experiences of recovery in the individual placement and support intervention. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 63(5), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764017708801

- Gariepy, G., & Iyer, S. (2019, January 01). The mental health of young Canadians who are not working or in school. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(5), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718815899

- Goldman-Mellor, S., Caspi, A., Arseneault, L., Ajala, N., Ambler, A., Danese, A., Fisher, H., Hucker, A., Odgers, C., Williams, T., Wong, C., & Moffitt, T. E. (2016, January 23). Committed to work but vulnerable: Self-perceptions and mental health in NEET 18-year olds from a contemporary British cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(2), 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12459

- Gutierrez-Garcia, R. A., Benjet, C., Borges, G., Méndez Ríos, E., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2018, December 26). Emerging adults not in education, employment or training (NEET): Socio-demographic characteristics, mental health and reasons for being NEET. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6103-4

- Gutierrez-Garcia, R. A., Benjet, C., Borges, G., Méndez Ríos, E., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2017, May 22). NEET adolescents grown up: Eight-year longitudinal follow-up of education, employment and mental health from adolescence to early adulthood in Mexico City. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(12), 1459–1469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1004-0

- Hafner, H., Loffler, W., Maurer, K., Hambrecht, M., & Heiden, W. A. D. (1999, September 10). Depression, negative symptoms, social stagnation and social decline in the early course of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 100(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10831.x

- Hafner, H., & Nowotny, B. (1995, January 01). Epidemiology of early-onset schizophrenia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 245(2), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02190734

- Iyer, S., Mustafa, S., Gariepy, G., Shah, J., Joober, R., Lepage, M., & Malla, A. (2018, August 11). A NEET distinction: Youths not in employment, education or training follow different pathways to illness and care in psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(12), 1401–1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1565-3

- Kessler, R. C., Amminger, G. P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., & Lee, S. (2007, June 07). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(4), 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c

- Killackey, E., Allott, K., Jackson, H. J., Scutella, R., Tseng, Y.-P., Borland, J., Proffitt, T.-M., Hunt, S., Kay-Lambkin, F., Chinnery, G., Baksheev, G., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., McGorry, P. D., & Cotton, S. M. (2019, September 27). Individual placement and support for vocational recovery in first-episode psychosis: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 214(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.191

- Larsen, T. K., Friis, S., Haahr, U., Johannessen, J. O., Melle, I., Opjordsmoen, S., Rund, B. R., Simonsen, E., Vaglum, P., & McGlashan, T. H. (2004, August 03). Premorbid adjustment in first-episode non-affective psychosis: Distinct patterns of pre-onset course. British Journal of Psychiatry, 185(2), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.185.2.108

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009, September 23). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339(jul21 1), b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

- Maraj, A., Mustafa, S., Joober, R., Malla, A., Shah, J. L., & Iyer, S. N. (2019). Caught in the “NEET Trap”: The intersection between vocational inactivity and disengagement from an early intervention service for psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 70(4), 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800319

- Marshall, M., Lewis, S., Lockwood, A., Drake, R., Jones, P., & Croudace, T. (2005, September 07). Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: A systematic review. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(9), 975–983. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975

- Marwaha, S., & Johnson, S. (2004, May 11). Schizophrenia and employment - a review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(5), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0762-4

- Mawn, L., Oliver, E. J., Akhter, N., Bambra, C. L., Torgerson, C., Bridle, C., & Stain, H. J. (2017, January 27). Are we failing young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of re-engagement interventions. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0394-2

- Mendelson, T., Mmari, K., Blum, R. W., Catalano, R. F., & Brindis, C. D. (2018, November 15). Opportunity youth: insights and opportunities for a public health approach to reengage disconnected teenagers and young adults. Public Health Reports, 133(1_suppl), 54S–64S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354918799344

- Michael, B. F. T. (1997). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). American psychiatric press.

- Nordgaard, J., Buch-Pedersen, M., Hastrup, L. H., Haahr, U., & Simonsen, E. (2019, August 28). Measuring psychotic-like experiences in the general population. Psychopathology, 52(4), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1159/000502048

- Nordgaard, J., Revsbech, R., Saebye, D. & Parnas, J. (2012, October 02). Assessing the diagnostic validity of a structured psychiatric interview in a first-admission hospital sample. World Psychiatry, 11 (3) , 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2012.tb00128.x

- Nuechterlein, K. H., Subotnik, K. L., Ventura, J., Turner, L. R., Gitlin, M. J., Gretchen-Doorly, D., Becker, D. R., Drake, R. E., Wallace, C. J., & Liberman, R. P. (2020, January 05). Enhancing return to work or school after a first episode of schizophrenia: The UCLA RCT of individual placement and support and workplace fundamentals module training. Psychological Medicine, 50(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718003860

- O’Dea, B., Glozier, N., Purcell, R., McGorry, P. D., Scott, J., Feilds, K.-L., Hermens, D. F., Buchanan, J., Scott, E. M., Yung, A. R., Killacky, E., Guastella, A. J., & Hickie, I. B. (2014, December 30). A cross-sectional exploration of the clinical characteristics of disengaged (NEET) young people in primary mental healthcare. BMJ Open, 4(12), e006378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006378

- Power, E., Clarke, M., Kelleher, I., Coughlan, H., Lynch, F., Connor, D., Fitzpatrick, C., Harley, M., & Cannon, M. (2015, March 01). The association between economic inactivity and mental health among young people: A longitudinal study of young adults who are not in employment, education or training. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 32(1), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2014.85

- PROSPERO. International prospective register of systematic reviews. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York.

- Ramsdal, G. H. (2018). Attachment problems and mental health issues among long-term unemployed youth who had dropped out of high school. University of Tromsoe.

- Ramsdal, G. H., Bergvik, S., Wynn, R., & Walla, P. (2018). Long-term dropout from school and work and mental health in young adults in Norway: A qualitative interview-based study. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1455365. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1455365

- Reer, V., Rosien, M., Jochheim, K., Kuhnigk, O., Dietrich, H., Hollederer, A., & Hebebrand, J. (2011). Psychiatric disorders and health service utilization in unemployed youth. Journal of Public Health, 19(S1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-010-0387-x

- Reininghaus, U. A., Morgan, C., Simpson, J., Dazzan, P., Morgan, K., Doody, G. A., Bhugra, D., Leff, J., Jones, P., Murray, R., Fearon, P., & Craig, T. K. J. (2008, May 21). Unemployment, social isolation, achievement-expectation mismatch and psychosis: Findings from the AESOP study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(9), 743–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0359-4

- Reneflot, A., & Evensen, M. (2014). Systematic literature review unemployment and psychological distress among young adults in the Nordic countries: A review of the literature. International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12000

- Rinaldi, M., Killackey, E., Smith, J., Shepherd, G., Singh, S. P., & Craig, T. (2010, May 28). First episode psychosis and employment: A review. International Review of Psychiatry, 22(2), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261003661825

- Rodwell, L., Romaniuk, H., Nilsen, W., Carlin, J. B., Lee, K. J., & Patton, G. C. (2018, September 07). Adolescent mental health and behavioural predictors of being NEET: A prospective study of young adults not in employment, education, or training. Psychological Medicine, 48(5), 861–871. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002434

- Russell,L. (2013). Researching marginalised young people. Ethnography and Education, 8(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2013.766433

- Schultz-Nielsen, M. L., Skaksen, J.R. (2016). Den økonomiske gevinst ved at inkludere de udsatte unge study paper 39 (The Rockwool Foundation). https://www.rockwoolfonden.dk/app/uploads/2016/01/Study-paper-39_Final.pdf.

- Scott, J., Fowler, D., McGorry, P., Birchwood, M., Killackey, E., Christensen, H., Glozier, N., Yung, A., Power, P., Nordentoft, M., Singh, S., Brietzke, E., Davidson, S., Conus, P., Bellivier, F., Delorme, R., Macmillan, I., Buchanan, J., Colom, F., … Hickie, I. (2013, September 21). Adolescents and young adults who are not in employment, education, or training. BMJ, 347(sep18 1), f5270. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f5270

- Sellstrom, E., Bremberg, S., & O’Campo, P. (2011, December 25). Yearly incidence of mental disorders in economically inactive young adults. European Journal of Public Health, 21(6), 812–814. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq190

- Stanghellini, G., Langer, A. I., Ambrosini, A., & Cangas, A. J. (2012). Quality of hallucinatory experiences: Differences between a clinical and a non-clinical sample. World Psychiatry, 11(2), 110–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.007

- Stilo, S. A., Gayer-Anderson, C., Beards, S., Hubbard, K., Onyejiaka, A., Keraite, A., Borges, S., Mondelli, V., Dazzan, P., Pariante, C., Di Forti, M., Murray, R. M., & Morgan, C. (2017). Further evidence of a cumulative effect of social disadvantage on risk of psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 47(5), 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002993

- Sveinsdottir, V., Eriksen, H. R., Baste, V., Hetland, J., & Reme, S. E. (2018, October 18). Young adults at risk of early work disability: Who are they? BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6095-0

- Symonds, J., Dietrich, J., Chow, A., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2016, March 02). Mental health improves after transition from comprehensive school to vocational education or employment in England: A national cohort study. Dev Psychol, 52(4), 652–665. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040118

- Thomsen, P. H. (1996, September 01). Schizophrenia with childhood and adolescent onset–a nationwide register-based study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 94(3), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09847.x

- Turner, N., Browne, S., Clarke, M., Gervin, M., Larkin, C., Waddington, J. L., & O’Callaghan, E. (2009, March 04). Employment status amongst those with psychosis at first presentation. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(10), 863–869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0008-6

- Unit, S. E. (1999). Bridging the gap: New opportunities for 16-18 year olds not in education, employment or training (pp. 122). Stationery Office.

- van Os, J., Linscott, R. J., Myin-Germeys, I., Delespaul, P., & Krabbendam, L. (2009, July 09). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: Evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychological Medicine, 39(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708003814

- Volkmar, F. R. (1996, July 01). Childhood and adolescent psychosis: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(7), 843–851. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199607000-00009

- Wells, G., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (). The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analysis. Accessed 7 4 2022 http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp,).

- Wittchen, H. U., Jacobi, F., Rehm, J., Gustavsson, A., Svensson, M., Jönsson, B., … Steinhausen, H. C. (2011). The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 21(9), 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018

- Yates, S., & Payne, M. (2007). Not so NEET? A critique of the use of ‘NEET’ in setting targets for interventions with young people. Journal of Youth Studies, 9(3), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260600805671