Abstract

Research on workplace fun has neither identified the processes through which its positive impact is achieved nor the mechanisms that facilitate it. In the present study we examined the protecting role of five workplace fun dimensions with regard to need for recovery from work, turnover intentions, and chronic social stressors and the mediating role of vigor, dedication and absorption (work engagement). We also explored workplace fun under conditions of high, medium and low trust. The study was a cross-sectional survey. Four hundred and thirty-three employed individuals working in various professions in Greece participated by filling in an online questionnaire. Convenience sampling was used. A series of hierarchical regression analyses and mediation and moderation analyses showed that work engagement dimensions (vigor, dedication, and absorption) mediate the impact of organic workplace fun and management support for fun on turnover intentions, chronic social stressors and need for recovery from work. A significant interaction effect of trust for the relationship between different types of workplace fun and the outcomes measured was found. Our study shows that the relationship of workplace fun with favorable outcomes can be explained by fluctuations in work engagement and is stronger when trust levels are sufficient.

Public interest statement

Organisations frequently invest in expensive fun initiatives to help increase productivity and boost well-being. Our research found that although workplace fun, specifically pure organic fun and management support for fun, had an impact on desirable workplace outcomes (need for recovery from work, turnover intentions, chronic social stressors), this could be explained through the increased engagement experienced. We also found that in the cases of low and medium levels of trust, pure organic fun and management for fun helped decrease the levels of turnover intentions, but in high levels of trust, fun dimensions increased turnover intentions. The same pattern was observed for the relationship of special fun events and management support for fun with need for recovery from work. Thus, fun initiatives may have the opposite result possibly through cynicism and not have an increased impact on workplace outcomes if work engagement is hindered.

Fun in the workplace is a relatively new construct in organizational psychology. To date the majority of research on fun at work has related types of fun like organic, organized and managed to only a small number of organizational variables like work engagement, job satisfaction and turnover intentions (e.g., Fluegge-Woolf, Citation2014; Tews et al., Citation2014).The mechanisms through which these results are achieved and the circumstances that can facilitate these processes are not yet fully understood (Michel et al., Citation2019). Thus, there is a need to further study the outcomes of workplace fun, and understand the explaining mechanisms that are involved.

1. The current study

The aim of the present study was to examine the impact of workplace fun on desirable outcomes and explore the factors that mediate and moderate these relationships.

In order to explore the relationship of workplace fun with desirable outcomes we utilized the suggestion of several researchers in the field, and conceptualized workplace fun as a job resource (Fluegge, Citation2008; Georganta, Citation2012; Georganta & Montgomery, Citation2016; Tews et al., Citation2013). Our conceptualization of job resources is rooted in the Job Demands-Resources Model (Demerouti et al., Citation2001), which is a model used to describe the variables that have an impact on wellbeing in the workplace. According to this model, job resources are described as the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are functioning through work engagement in achieving work goals, reducing job demands or stimulating personal growth, learning, and development (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2004). Conceptualized as a job resourse, we hypothesized that workplace fun may function as a preventive or protective mechanism affecting outcomes in a positive way (Georganta & Montgomery, Citation2016). Specifically, in this study we explord the role of workplace fun with regard to turnover intentions, chronic social stressors and need for recovery from work, as these are three key outcomes that impact the modern workplace.

This process though is not direct. We hypothesized that work engagement will be vital in the relationship between fun and desirable outcomes, as it is an important process that explains relationships between variables in the context of the Job Demands-Resources Model. If workplace fun is indeed a factor that can have a positive impact on these outcomes and ameliorate their development, we assume that this will confirm its protecting role and will be explained via the path of work engagement.

Furthermore, we explored workplace fun in relation to trust. According to the literature, whether workplace fun is supported by management is considered an important factor that can have a significant impact on positive outcomes (Tews et al., Citation2013). At the same time there is a critical view in the literature in terms of the effects of managed fun that highlights the risk of employees perceiving management initiatives with cynicism (e.g., Fleming, Citation2005). Based on this, we aimed to explore whether fun will impact differently on turnover intentions, chronic social stressors and need for recovery from work, under different conditions of organizational trust (high, medium and low).

In the present study we measured the whole spectrum of fun activities as depicted in the literature using a self-constructed tool synthesizing existing measures of workplace fun and results of previous qualitative studies on the topic. Thus, we were able to test multiple associations contributing to a more efficient understanding of the impact of various types of fun on desirable outcomes. The study is split into two sections; first we developed the conceptualization of fun activities as a construct and conducted a factor analyses and second, we tested structural relations between fun dimensions and desirable outcomes.

1.1. Section one: what is workplace fun?

A review of the various definitions of workplace fun highlights the diversity regarding the conceptualization of the phenomenon. For example, Ford et al. (Citation2003) define a fun work environment as one that “intentionally encourages, initiates, and supports a variety of enjoyable and pleasurable activities that positively impact the attitude and productivity of individuals and groups” (p. 22). McDowell (Citation2004, p. 9) conceptualized a fun climate as one that constitutes of activities like socializing with co-workers, celebrating at work, and having personal freedoms at work and noted that whether such activities are supported by management, is also an important indicator. Strömberg et al. (Citation2009) view workplace fun as a cluster of humor rituals like joke telling, physical joking practices, clowning, and nicknaming; they found that employees used these practices to intentionally create a fun workplace and have labelled these behaviors as organic fun to differentiate it from organized fun or managed fun, which has to do with activities like celebrations, social events, competitions and community involvement (e.g., Chan, Citation2010; Ford et al., Citation2003).

So far two clusters of fun types have been suggested and used in the literature; organic fun or coworker socializing and managed fun or fun activities (McDowell, Citation2004; Tews et al., Citation2014). Organic fun has to do with fun activities and behaviors stemming from the employees themselves, while managed fun has to do with fun activities initiated by the organization’s management. Measurement has focused on the perceived frequency of fun activities, either organic or managed, but so far there is no study to our knowledge that has studied the whole spectrum of fun activities as depicted in the literature, that includes a broader range of fun activities and a more detailed distinction between those already identified in the literature.

Specifically, organic fun can include activities with playful characteristics like playing around and poking, as well as activities like sharing each other’s stories and joking that gravitate more towards the socializing pole than the playfulness one. Furthermore, previous studies (Georganta & Montgomery, Citation2019) have found that employees perceived gossiping as fun. As gossip is a very distinct form of sharing stories, we suggest that it should be measured distinctly from other forms of socialization. Gossip reflects small talk and using satire in the interactions which can have a positive impact on individual outcomes (Brady et al., Citation2017; Hobfoll et al., (Citation2018, Citation2019). On the other hand, literature suggests that gossip has mixed results and can have both a positive and a negative impact in organizations (Tan et al., Citation2021).

Also, socializing with co-workers outside of work, has been conceptualized both as personal freedoms and organic fun. But in line with Georganta and Montgomery (Citation2019) we suggest that this could be a form of fun that could be conceptualized inside the boundaries of both organic and managed fun (McDowell, Citation2004). A new district type of fun, called organized fun (Georganta & Montgomery, Citation2019), could reveal a potentially distinct impact on desirable outcomes as it has the unique characteristic of both detaching from work itself and still remaining connected with its processes.

Managed fun can also be divided into sub-categories as there are studies that have looked into managed fun as activities celebrating events and milestones (McDowell, Citation2004) and studies that present managed fun as recreation activities, like trips and contents. Chan (Citation2010) suggested that different activities are oriented towards different targets, either individual or group ones and have distinct goals in terms of desirable outcomes like increasing sense of belonging or building good relationships.

Furthermore, the literature suggests measuring workplace fun in a more holistic way depicting the culture of the organization in relation to fun. Thus previous studies have measured management support for fun (Tews et al., Citation2014), and global fun and personal freedoms (McDowell, Citation2004) as a way to study organization level attitudes towards the phenomenon and the concept of culture of fun.

The above conceptualizations show that there is a variety of activities and behaviors that can be considered fun in the workplace, but the literature so far does not offer a clear distinction regarding the functionality of each type of fun. A a series of studies from Fleming and his colleagues (2005; Fleming & Sturdy, Citation2011; Fleming et al., Citation2009) though indicate that not all types of workplace fun have the same effects on outcomes.

The present study aimed to develop and use a multidimensional measure of fun as there is no measurement so far that measures all aspects of workplace fun.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure and sample

We collected data using an online questionnaire platform and utilizing a convenience sampling method. The link for the study’s online questionnaire was shared in several social media sites and was published for the wider public through a well-known online newspaper. This online approach to recruiting participants limits our ability to identify non-responders or to assess the response rate.

2.2. Participants

Four hundred and thirty three employed individuals participated in this study (N = 433, Mage = 37.14, SDage = 9.26, 60% women). All participants were Greek, 40% were single and 44% were married, 50% were professionals and technicians and associate professionals and 45% were clerical support and services and sales workers (International Labor Organization, Citation2008).

2.3. Measures

Workplace fun: As already noted in the introduction, no previous research has studied the whole spectrum of fun activities as depicted in the literature. Therefore, to provide a comprehensive assessment of workplace fun, we used a self-constructed tool synthesizing existing measures of workplace fun from the literature and data derived from 34 individual interviews which were conducted as part of a previous qualitative study (Georganta & Montgomery, Citation2019). Our final workplace fun questionnaire contained 20 items and five subscales (i.e., Pure Organic Fun, Fun Special Events, Management Support for Fun, Gossip, Personal Freedoms).

In this paragraph we will explain the procedure and main steps in developing the questionnaire. We started with two validated questionnaires that measured the following elements of workplace fun; celebrating fun, global fun, personal freedoms and socializing with co-workers (McDowell, Citation2004) and experienced fun (Karl et al., Citation2007). Specifically, we used all six items from the Socializing with co-workers dimension, five items from the Celebrating dimension, five items from the Personal Freedoms dimension, and two items from the Global Fun dimension of McDowell’s (2005) Fun at Work Climate Scale. We also used the three items developed by Karl et al. (Citation2007) to measure the level of fun experienced at work. In order to more comprehensively measure the phenomenon of fun, we used the results of two qualitative studies that identified workplace fun activities that were not included in the already existing questionnaires. These activities reflected organic fun and social oriented workplace fun (Chan, Citation2010; Strömberg et al., Citation2009). Specifically, we have extracted seven concepts from Strömberg et al.’s (Citation2009) analysis of the nature of humour among workers to create seven items depicting organic fun activities in the workplace. Also, we used four examples of the Social-oriented workplace fun category of Chan’s (Citation2010) four “S”s Workplace Fun Framework to generate four items measuring Fun Special Events. Finally, we added ten self-constructed items based on the results of the individual interviews mentioned above (Georganta & Montgomery, Citation2019). The data collected from the interviews revealed ten items describing workplace fun behaviours not included in already published questionnaires, that further enriched the above measurements. The new items developed, were piloted and refined in terms of understanding and relativeness. These items reflected activities and behaviors related to fun events, management support for fun, organic fun and personal freedoms.

Participants were asked to rate how often the activities occurred in their workplace using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 2 = A few times a year or less, 3 = Once a month, 4 = A few times a month, 5 = Once a week, 6 = A few times a week, 7 = Every day). The 7 point Likert scale was chosen in order to better capture the variability in responses, and is recommended as the optimal size scale in survey research (Preston & Colman, Citation2000). This procedure resulted in an initial 42 item questionnaire (see, Georganta, Citation2017, pp. 108–111 for a detailed description).

We conducted exploratory factor analysis to delineate the core factors in our measure of workplace fun. In order to perform these analyses we used the IBM SPSS 20 Statistical Package. A principal axis factor analysis of the 42 items with oblique rotation (direct oblimin) was employed as we needed to estimate the underlying factors. Based on the literature on the topic correlation between factors should be permitted. Factor analysis was chosen as it represents the most high quality decision when the purpose is to understand the latent variables that account for relationships among the measured variables (Conway & Huffcutt, Citation2003) while accounting for measurement error (Schmitt, Citation2011).

2.4. Results of factor and parallel analyses

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis (KMO = .89). An initial analysis was run to obtain eigenvalues for each factor in the data. Nine factors had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1. In order to make the best possible decision for factor retention we decided to further conduct a parallel analysis (Horn, Citation1965). Parallel analysis is considered the most accurate method for determining the number of factors to retain (Fabrigar et al., Citation1999). For the Parallel Analysis we used the guide provided by Hayton et al. (Citation2004). Parallel analysis indicated that only 5 factors should be retained (the eigenvalues of factors from the actual data that exceed the random and the 95th percentile eigenvalues from the simulation can be considered to be actual factors present in the dataset). The final solution retained 20 items and is presented in Table .

Table 1. Pattern Matrix, Summary of exploratory factor analysis results for the Workplace Fun Questionnaire (factor loadings over .40)

3. Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop a questionnaire measuring workplace fun that integrates a variety of activities and attitudes towards the phenomenon. The results support the allocation of 20 items to five dimensions; (1) pure organic fun (2) special events (3) management support for fun, (4) gossip and (5) personal freedoms. A more complex factor structure could not be retained.

Pure organic fun comprises of behaviors that arise spontaneously, and evolve among individuals without employment of any factors external to the directly interacting parts. Fun special events is a factor related to activities organized by the organization aiming mainly for employee recreation or community benefit. The gossip factors refers to discussing and satirizing colleagues or events that take place in the workplace. Two factors refer to organizational level attitudes towards fun. First, management support for fun refers to attitudes towards workplace fun help by the supervisor. Second, personal freedoms refers to activities that employees can engage to while working. These activities are not directly related to workplace fun, but they can indirectly nurture fun activities. These five dimensions offer a more detailed operationalization of fun allowing research to explore the distinct impact of each factor on desirable outcomes.

3.1. Section two: the protective role of workplace fun

3.1.1. The job-demands and resources model

Workplace fun was conceptualised as a job resource in the context of the Job Demands-Resources Model. The JD-R Model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007; Demerouti et al., Citation2001) is a model used to predict employee burnout and engagement. In its core the model describes job strain as the result of a disturbance of the equilibrium between the demands employees are exposed to and the resources they have at their disposal. According to the model, every work environment has unique characteristics that stem from differences based on the differences among occupations, organizations or groups. These unique characteristics and their interaction are weighted by the individual; when demands are perceived as higher than resources, a health impairment process may be activated leading to increased burnout levels. When resources are plentiful then a motivational process may be activated leading to increased work engagement.

Job resources can refer, among others, to interpersonal and social relations. These types of resources can involve interactions between supervisors and co-workers or among peers, as well as perceived support and a psychologically safe climate. These types of resources can fulfill the basic needs (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000) for relatedness (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007; Demerouti et al., Citation2001) and can have a positive impact on employee wellbeing (Lesener et al., Citation2019). Workplace fun involves a numbers of activities that create a positive work environment (Jyoti et al., Citation2022; Michel et al., Citation2019; Tetteh et al., Citation2022) and thus can be considered a job recourse that can lead to positive outcomes in the workplace by activating the motivational process or by interacting with job demands and inhibiting their negative impact.

Section two of the present study will explore relations and interactions between workplace fun and a series of individual and organizational outcomes showcasing the protecting role of workplace fun.

3.2. Employee turnover and workplace fun

Employee turnover, defined as “the departure of an employee from the formally defined organization” (March & Simon, Citation1958), has grown in complexity with a large pool of predictors used to study the phenomenon (Holtom et al., Citation2008), while many new theories and concepts have evolved over a period of time. Its antecedents and its implications for performance have been widely studied in the human resource management literature (e.g., Hancock et al., Citation2013). In the case of workplace fun, in a series of studies from Tews and his colleagues (Tews et al., Citation2013; Tews et al., Citation2014) a negative relation between management support for fun and turnover and socializing with co-workers and turnover was found. Other studies have linked workplace fun to desirable organizational outcomes that can decrease turnover intentions, especially to job satisfaction (e.g., Peluchette & Karl, Citation2005). Also, Karl and Peluchette (Citation2006) have found that experiencing workplace fun could be linked to lower absenteeism. Some fun activities and management support for fun have been found to be related to affective commitment (Tews et al., Citation2013) which is also considered an important indicator of turnover (Meyer et al., Citation2002). Thus, we can expect that fun activities may decrease turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 1: Workplace fun dimensions (pure organic fun, fun special events, management support for fun, gossip and personal freedoms) will be negatively related with turnover intentions.

4. Chronic social stressors

Social stressors consist of social animosities, conflicts with co-workers and supervisors, unfair behavior, incivility and a negative group climate. Dormann and Zapf (Citation2002) have found a relationship between social stressors and social animosities at work with irritation and depressive symptoms. Social or interpersonal stressors are important predictors of other psychological strain variables as shown in the studies of Keashly et al. (Citation1997), and Zapf et al. (Citation2001). Thus we can hypothesize that workplace fun will be negatively related with chronic social stressors, as workplace fun is considered a phenomenon related to positive interpersonal relations (Fluegge-Woolf, Citation2014).

Hypothesis 2: Workplace fun dimensions (pure organic fun, fun special events, management support for fun, gossip and personal freedoms) will be negatively related with chronic social stressors.

5. Need for recovery from work

Need for recovery from work refers to a person’s desire to be temporarily relieved from work demands in order to replenish internal resources (Sluiter et al., Citation1999) and it is characterized by a temporal reluctance to continue with the present demands or to accept new ones (Sonnentag & Zijlstra, Citation2006). A high need for recovery from work implies that work demands that employees face lead to increased strain. Georganta and Montgomery (Citation2016) suggested that if during the work day the employees experience fun, these experiences could act as a resource, replenish the employees’ vigor and decrease the need for recovery from work. Thus we assume that workplace fun would reduce the need for recovery from work.

Hypothesis 3: Workplace fun dimensions (pure organic fun, fun special events, management support for fun, gossip and personal freedoms) will be negatively related with need for recovery from work.

6. Workplace fun and work engagement

Literature so far has established a direct connection between workplace fun and work engagement. Plester and Hutchison (Citation2016) were one of the first scholars to link workplace fun with work engagement; through an ethnographic approach that generated rich qualitative data on the issue, they suggested that task related fun enables employees to enjoy their roles and at the same time the opportunity to pause their tasks for a while and have fun with their coworkers creates a workplace climate that is enjoyable too. Schaufeli and Bakker (Citation2004) defined work engagement as a “positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind”. Work engagement comprises of its core components vigor (i.e., energy, persistence, and willingness to exert effort), dedication (i.e., enthusiasm, inspiration, and perceptions of significance), and absorption (i.e., full concentration and immersion in one’s work). But, consistent with the Job Demands and Resources model, we can hypothesize that work engagement (measured using these three distinct dimensions; vigor, dedication and absorption) not only will be a positive outcome of workplace fun, but that it will function as an explanatory mechanism for the effects of workplace fun dimensions on other outcomes. We can hypothesize the following:

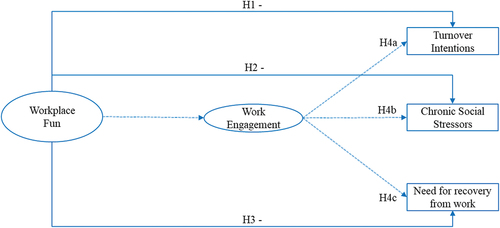

Hypothesis 4a: Work engagement (vigor, dedication, absorption) will mediate the relationship between workplace fun dimensions and turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 4b: Work engagement (vigor, dedication, absorption) will mediate the relationship between workplace fun dimensions and chronic social stressors.

Hypothesis 4c: Work engagement (vigor, dedication, absorption) will mediate the relationship between workplace fun dimensions and need for recovery from work.

6.1. The relation between workplace fun and trust

The benefits of trust within organizational settings have been widely studied (e.g., De Jong et al., Citation2016). According to Kramer (Citation2010) positive expectations about others lead to positive behaviors when interacting with them and in a cyclical way the positive behaviors towards the other can lead to positive expectations; hence, a cycle of positive expectations and actions is created and reinforced. The literature on workplace fun has cautioned against an excessively managerial perspective on fun. Several studies have showed that some employees perceived managed fun initiatives as patronizing (e.g., Fleming, Citation2005; Fleming & Sturdy, Citation2011; Plester et al., Citation2015) or that they aimed at results other than the employees’ wellbeing (Waren & Fineman, Citation2007). Karl et al. (Citation2005) have also found that employees’ attitudes regarding the appropriateness and salience of workplace fun were related to trust. Taking into consideration the above, we understand that managed fun has the potential to result in adverse outcomes, as it may be viewed as a burden rather than a resource. Thus we assume that trust can play an important role in the way workplace fun is perceived. Specifically we propose that organizational trust will be related to perceived workplace fun. Plester and Hutchison (Citation2016) found that workplace fun can contribute to better relationships in the workplace by increasing the feelings of psychological safety through camaraderie, a concept that is built on relationships characterized by trust. Furthermore managed fun resulting in negative outcomes is possible when the initiative does not reflect the values of the organization or when management is not perceived as benevolent. Opposite results might be generated if respect and dignity are not part of the equation (Fleming, Citation2005; Owler et al., Citation2010) or when the needs of the employees are not taken into consideration (Everett, Citation2011). Thus, we hypothesize that the levels of trust (a phenomenon contingent to the above) will play an important role in the explored relationships, as per below:

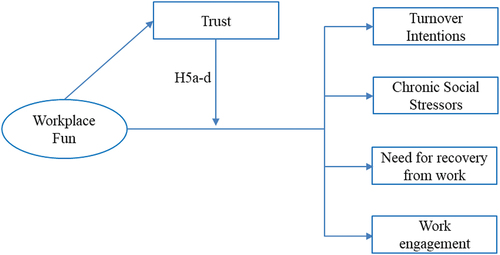

Hypothesis 5a: Trust will moderate the effects of workplace fun dimensions (pure organic fun, fun special events, management support for fun, gossip and personal freedoms on turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 5b: Trust will moderate the effects of workplace fun dimensions (pure organic fun, fun special events, management support for fun, gossip and personal freedoms on chronic social stressors.

Hypothesis 5c: Trust will moderate the effects of workplace fun dimensions (pure organic fun, fun special events, management support for fun, gossip and personal freedoms on need for recovery from work.

Hypothesis 5d: Trust will moderate the effects of workplace fun dimensions (pure organic fun, fun special events, management support for fun, gossip and personal freedoms on work engagement (vigor, dedication, absorption).

We depict the mediation and moderations effects in Figures respectively.

7. Methods

In this survey we assessed workplace fun, turnover intentions, chronic social stressors, need for recovery from work, vigor, dedication, absorption, trust and demographic information.

Procedure, sample and participant information can be found in section one of this paper.

7.1. Measures

Workplace fun: Information for this measurement can be found in section one of this paper.

Turnover intentions: Turnover intentions were assessed with the following two questions; (1) “I am actively searching for another job” rated with a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Completely disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Completely agree) and (2) “How often do you think that you want to quit your job” rated with a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 2 = A few times a year or less, 3 = Once a month, 4 = A few times a month, 5 = Once a week, 6 = A few times a week, 7 = Every day).

Chronic Social Stressors: Chronic interpersonal tensions with colleagues (e.g., conflicts, personal animosities, or unfair behavior) were assessed with a scale created by Frese and Zapf (Citation1987). Participants rated 17 items using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). An example item is “With some colleagues there is often conflict”.

Need for recovery from work: Need for recovery from work was assessed with the translated Van Veldhoven (Citation2003) version of the Van Veldhoven and Meijman Dutch questionnaire for the Questionnaire on the Experience and Evaluation of Work (VBBA) (1994). The questionnaire consists of 11 items. The participants were asked to report the frequency of symptoms using a 4-point scale (1 = never, 4 = Always). An example item is “I find it difficult to relax at the end of a working day”.

Work Engagement: Engagement was assessed with the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002). The measurement consists of three subscales, vigor (6 items), dedication (5 items) and absorption (6 items) which were measured with a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 2 = A few times a year or less, 3 = Once a month, 4 = A few times a month, 5 = Once a week, 6 = A few times a week, 7 = Every day). Reliability for the total measurement was Cronbach’s α = 0.95. An example item is “When I get up in the morning I feel like going to work”.

Trust: Trust was assessed with the scale developed by Nyhan and Marlowe (Citation1997). The scale consists of 4 items. The participants were asked to report their level of trust using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Nearly zero, 2 = Very low, 3 = Low, 4 = Moderate, 5 = High, 6 = Very high, 7 = Near 100%). An example item is “The level of trust between supervisors and workers in this organization is”.

8. Results

8.1. Analysis strategy

To test hypotheses 1–3 first we conducted a series of hierarchical regression analyses using the IBM SPSS 20 Statistical Package. To test hypotheses 4a-4c we conducted a mediation analysis and to test hypotheses 5a to 5d we conducted a moderation analysis. For both the mediation and moderation analyses we used the method provided by Preacher and Hayes (Citation2004) and the SPSS PROCESS macro provided by Hayes (Citation2012).

Hypotheses 1–3

In Table the means, standard deviations, correlation coefficients and Cronbach’s alpha statistics of the variables included in the study are depicted.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, Correlation coefficients and Cronbach’s α

Hypotheses 1–3 can be partially accepted. As depicted in Table Pure Organic Fun and Management Support for Fun, significantly predicted variance in Turnover Intentions. Gossip also predicted variance in Turnover Intentions but with a positive valence. Age remained a significant predictor of variance in Turnover Intentions, in step 2 (H1). Pure Organic Fun and Management Support for Fun significantly predicted variance in Chronic Social Stressors, while Special Fun Events and Gossip predicted variance in Chronic Social Stressors but with a positive valence (H2). Pure Organic Fun significantly predicted variance in Need for Recovery from Work while Gossip predicted variance in need for recovery from work with a positive valence (H3).

Hypotheses 4a-c

Hypotheses 4a-c were partially supported. As depicted in Table there were significant indirect effects only of Pure Organic Fun and Management support for fun on Turnover intentions and Chronic Social Stressors through Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption. Also, there were significant indirect effects of Management support for fun on Need for recovery from work through Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption.

Hypotheses 5a-d

Hypotheses 5a-d can be partially accepted. We found a significant interaction effect of trust for pure organic fun and turnover intentions (b = .13, 95% CI [.048, .211], t = 3.11, p < .05, R2 = .17) and management support for fun and turnover intentions (b = .11, 95% CI [.007, .205], t = 2.11, p < .05, R2 = .18; see, Figures for the simple slopes graphs) (H5a).

Figure 3. Simple slopes equations of the regression of turnover intentions on pure organic fun at three levels of trust.

Figure 4. Simple slopes equations of the regression of turnover intentions on management support for fun at three levels of trust.

Table 3. Linear models of predictors of turnover, chronic social stressors, need for recovery from work, vigor, dedication, absorption and trust based on 1000 bootstrap samples

Table 4. Significant results of mediation analyses

Also, there was a significant interaction effect of trust only for the relationship between management support for fun and chronic social stressors (b = .08, 95% CI [.024, .135], t = 2.83, p < .05, R2 = .50; see, Figure for the simple slopes graphs) (H5b). In terms of need for recovery from work, there was a significant interaction effect of trust only for the relationship with Fun Special Events (b = .14, 95% CI [.057, .226], t = 3.28, p < .001, R2 = .10) and management support for fun (b = .05, 95% CI [.008, .091], t = 2.32, p < .05, R2 = .09; see, Figures for the simple slopes graphs) (H5c). There was no significant interaction effect of trust for the relationships between workplace fun and vigor, dedication or absorption (H5d). A summary of simple slopes analyses is depicted in Table .

Figure 5. Simple slopes equations of the regression of chronic social stressors on management support for fun at three levels of trust

Figure 6. Simple slopes equations of the regression of need for recovery from work on fun special events at three levels of trust

Figure 7. Simple slopes equations of the regression of need for recovery from work on management support for fun at three levels of trust

Table 5. Summary of simple slopes analyses

9. Discussion

In this study we found that pure organic fun and gossip were significant predictors of turnover intentions, chronic social stressors, need for recovery from work, work engagement and trust. Management support for fun predicted all variables except from need for recovery from work. Fun special events predicted chronic social stressors and dedication. Furthermore, we found a significant indirect effect of pure organic fun on turnover intentions and chronic social stressors through vigor, dedication and absorption. We also found a significant indirect effect of management support for fun on turnover intentions, chronic social stressors, and need for recovery through the same three dimensions of work engagement. These two results confirm our hypothesis that the relationship between workplace fun and desirable outcomes is mediated by work engagement.

As trust plays an important role in organizations and different levels of trust might affect the perception of fun from a positive experience to a coercive task we found that for different levels of trust, fun categories had different results. Specifically, trust was examined as a moderator of the relations between workplace fun and turnover intentions, chronic social stressors, need for recovery from work and work engagement. We found that in the cases of low and medium levels of trust pure organic fun was helpful in decreasing the levels of turnover intentions, but in high levels of trust fun dimensions were found to increase turnover intentions. The same relationship is observed for management for fun. The same pattern is observed for the relationship of special fun events and management support for fun and need for recovery from work. In terms of chronic social stressors there were significant interaction effects of management support and chronic social stressors in different levels of trust but there was no difference in terms of valence, i.e. management support for fun decreased chronic social stressors in all three levels of trust.

9.1. Fun functions through engagement

According to the Job Demands and Resources model, fun as a job resource will impact on positive outcomes through work engagement. Our study supports previous findings on the impact of fun on work engagement (Plester & Hutchison, Citation2016; Tsaur et al., 2019) and found further support that work engagement is an important process that can explain the relationship found between management support for fun, and pure organic fun with turnover intentions, chronic social stressors and need for recovery from work. Work engagement is an important factor in the workplace as it has been connected with perceived health, well-being, and positive social relationships (Schaufeli et al., Citation2008) and the vigor component has proven to be especially important in explaining why employees give effort at work (Robinson et al., Citation2004).

9.2. The role of trust

Trust was taken into consideration very early in the history of studying workplace fun, as a series of studies showed that low levels of trust in the organizations’ intentions for promoting workplace fun can lead to cynicism (Fleming, Citation2005; Fleming & Sturdy, Citation2011; Plester et al., Citation2015). The negative side of workplace fun was evident in this study. If we would like to analyze the concept a bit deeper, being able to have fun in the workplace entails feeling free and safe to express oneself and reveals a background of trust. There is an interesting paradox concerning the experience of fun. Making “fun” of someone can be enjoyable and bonding for the actor and their co-actors but might have negative consequences for the person receiving the fun comments or being the epicenter of the negative jokes. This highlights an issue to take into consideration, that is, that the line between bullying and fun can be a thin one. In order to understand the negative side of fun, important issues regarding fun need to be disentangled, especially regarding organic fun and its manifestations, as they are those inherent to human nature. Different behaviors that entail organic and organized fun should be recognized. Most importantly, the emotions that follow the experience of organic versus organized fun should be distinguished.

10. Different types of fun

10.1. Managed fun

Our study also offers an insight into the distinct functions of the various types of workplace fun. The results confirm that managed fun in the form of special fun events or fun related freedoms does not have a significant impact in organizational outcomes. As the literature so far suggested, managed fun has limited impact due to its sometimes forced character and as Plester et al. (Citation2015. p. 383–384) noted “intentionally attempting to create workplace fun runs the risk of backfiring, chasing fun away and creating instead discomfiture, ridicule and dismay”. Only one fifth in Plester et al.’s (Citation2015) study’s respondents claimed to enjoy this category of fun and the negative comments for workplace fun that were mentioned were mostly for this category. Waren and Fineman (Citation2007) found that fun activities were interpreted and experienced by the employees in ways that contradict a simple analysis of fun; some participants debunked or subverted the instruments of fun, while for others the very existence of a fun program seemed to contribute to their feelings of wellness, and being valued. Also, Fleming (Citation2005) argues for a model of fun that does not compromise dignity and respect, (2005, p. 300). In this context “fun” emerges unpretentiously out of a culture of basic assumptions that rest support and ownership with each individual employee. Our study offers an insight into these relationships by showing the moderating role of trust.

10.2. Gossip

While we could hypothesize positive effects of such interactions, in our study we found only a negative impact. The most observable negative aspects of gossip is the damage it can do to relationships and to the reputations of other persons and their stature in the workplace (Kurland & Pelled, Citation2000) and it has been connected with the turnover of valued employees (Danziger, Citation1988), which was confirmed by this study too. Several types of fun, like small talk, that includes gossip, may be developed out of the employees’ frustration and their need to control a situation. Negative gossip that might come out of these talks could be a maladaptive way of controlling the demands of a workplace. In a recent study, negative gossip was positively associated with burnout, in terms of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and negatively related to work engagement (Georganta et al., Citation2014). Gossip can be used to express some of the deepest emotions about others (Waddington, Citation2005) and it has been considered as a form of emotional support and a way to relieve stress (Waddington et al., Citation2005).

10.3. Management support for fun

Management support for fun was measured in this study, as one variable that reflects underlying assumptions (Owler et al., Citation2010), of the organization towards fun. As expected, underlying assumptions are the most important and consistent predictor of workplace fun. Leadership style and support is crucial for encouraging workplace fun. The literature suggests that a “transformational leadership” style is effective for managing employees (Bass, Citation1999). Such a leader provides a clear vision, inspires and motivates, offers intellectual challenges, and shows real interest in the needs of the workers. This kind of leader elevates the personal status of workers through his or her ability to demonstrate humility, values, and concern for others, which is the benevolent leadership style that can enhance the impact of fun. The result for this leadership style in workplace fun is often that employees develop greater trust in management and perceive fun initiatives as management efforts to support their wellbeing while respecting them, both of which are factors that are strongly associated with the effectiveness of workplace fun.

11. General discussion

This is one of the first attempts, to our knowledge, to include such an inclusive view of fun and enhances previous work on the topic that uses mainly measurements of organic and managed fun. Our study has used a newly developed 20-item questionnaire measuring fives dimensions of workplace fun; (1) pure organic fun (2) special events (3) management support for fun, (4) gossip and (5) personal freedoms. The impact of these five dimensions on employee turnover, chronic social stressors and need for recovery from work was explored, confirming our hypothesis that workplace fun can function as a job recourse. Further, we found support for our mediation hypotheses indicating that workplace fun functions through work engagement and our moderation hypotheses showed that fun can have an important impact when levels of trust are low.

Our results support those of previous studies that show that fun can function as a job resource thus activating a motivation process through work engagement as well as protecting against job demands.

11.1. Limitations and suggestions for future research

The cross-sectional design of our study means it is difficult to attribute causality between the variables. While the design of the study does not allow for causal interpretations, findings highlight the link between fun and engagement. This relationship should be further explored by future studies using longitudinal designs. In addition more research is needed to identify which specific dimensions of fun are affected and affect organizational variables, which mediators explain them and which moderators might have an impact. This study assessed workplace fun using a more comprehensive measure that was a collation of previous questionnaires on the topic and of new items developed for this study. Our new measure is a strength of the study and utilized a factor identification technique (i.e., parallel analysis) that is highly recommended but rarely used in psychology. However, future research should focus on establishing a questionnaire that encompasses the multidimensional nature of fun for further use. All constructs were assessed via self-reports, which raises concerns that results may have been biased by common method variance. Given the recent emphasis on the role of enjoyment and positivity in the workplace, future studies should consider workplace fun within that framework while including team related variables as potential correlates for workplace fun both in traditional and hybrid workplaces.

12. Conclusions

Workplace fun emerged as a job resource, contributing with a significant positive impact on and through work engagement. Our results suggest that higher levels of positive fun interactions with colleagues create a positive environment where engagement can flourish. This is especially relevant given the shift toward team‐based work environments (LePine, Citation2003) taking into consideration that engagement and positive mood can cross over from one person to another (Fredrickson, Citation2001). Management can benefit from this interpersonal transmission by promoting positive interactions by setting up social events which may help this transfer. But perceived superficiality of expensive “fun at work” initiatives, particularly when other requests were not granted, as evident in this paper will not lead to desirable results. The results of this study show which types of fun can lead to desired results but more importantly highlights the path to them through increased vigor and trust revealing that workplace fun can have a significant impact on work engagement and turnover intentions, outcomes which are greatly sought by today’s employers as a means to increase performance and reduce retention. Caution should be taken thus to the organization’s intentions when promoting workplace fun activities, as initiatives can lead to cynicism when not employee centered. Trust is a precondition for fun initiatives to be considered appropriate and at the same time fun can help build trust in co-workers, supervisors and the organization. Finally, the results show that bottom up approaches combined with management support should have significant impact in terms of creating a work environment in which people can have fun while trusting each other.

correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katerina Georganta

Katerina Georganta (22 June 2017). Workplace Fun. Retrieved from osf.io/xcktm

References

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(, 1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398410

- Brady, D. L., Brown, D. J., & Liang, L. H. (2017). Moving beyond assumptions of deviance: The reconceptualization and measurement of workplace gossip. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000164

- Chan, S. C. H. (2010). Does workplace fun matter? Developing a useable typology of workplace fun in a qualitative study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(4), 720–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.03.001

- Conway, J. M., & Huffcutt, A. I. (2003). A review and evaluation of exploratory factor analysis practices in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 6(2), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428103251541

- Danziger, E. (1988). Minimize office gossip. Personnel Journal, 671, 31–34.

- De Jong, B. A., Dirks, K. T., & Gillespie, N. (2016). Trust and team performance: A meta-analysis of main effects, moderators, and covariates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(8), 1134–1150. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000110

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (2002). Social stressors at work, irritation, and depressive symptoms: Accounting for unmeasured third variables in a multi-wave study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317902167630

- Everett, A. (2011). Benefits and challenges of fun in the workplace. Library Leadership and Management, 25(1), 1–10.

- Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272

- Fleming, P. (2005). Workers’ playtime? Boundaries and cynicism in a “culture of fun” program. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(3), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886305277033

- Fleming, P., & Sturdy, A. (2011). ‘Being yourself’ in the electronic sweatshop: New forms of normative control. Human Relations, 64(2), 177–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710375481

- Fleming, P., Sturdy, A., & Bolton, S. (2009). Just be yourself!” Towards neo-normative control in organisations? Employee Relations, 31(6), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450910991730

- Fluegge, E. R. (2008), “Who put the fun in functional? Fun at work and its effects on job performance”, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Florida.

- Fluegge-Woolf, E. R. (2014). Play hard, work hard. Management Research Review, 37(8), 682–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-11-2012-0252

- Ford, R. C., McLaughlin, F. S., & Newstrom, J. W. (2003). Creating and sustaining fun work environments in hospitality and service organizations. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 4(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1300/J171v04n01_02

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). “The role of positive emotions in positive psychology”, The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Frese, M., & Zapf, D. (1987). Eine Skala zur Erfassung von Sozialen Stressoren am Arbeitsplatz [A scale measuring social stressors at work]. Zeitschrift fur Arbeitswissenschaft, 41(3), 134–141.

- Georganta, K. (2012). Fun in the workplace: A matter for health psychologists? The European Health Psychologist, 14(2), 41–45.

- Georganta, K. (2017), “Fun and positive experiences in the workplace: Effects on job burnout, need for recovery and job engagement”, Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Macedonia.

- Georganta, K., & Montgomery, A. (2016). Exploring fun as a job resource: The enhancing and protecting role of a key modern workplace factor. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 1(1–3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-016-0002-7

- Georganta, K., & Montgomery, A. (2019). Workplace fun: A matter of context and not content. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 14(3), 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-06-2017-1541

- Georganta, K., Panagopoulou, E., & Montgomery, A. (2014). Talking behind their backs: Negative gossip and burnout in hospitals. Burnout Research, 1(2), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2014.07.003

- Hancock, J., Allen, D., Bosco, F., McDaniel, K., & Pierce, C. (2013). Meta-Analytic review of employee turnover as a predictor of firm performance. Journal of Management, 39(3), 573–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311424943

- Hayes, A. F. (2012), “PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable moderation, mediation, and conditional process modeling”, available at http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed 10 December 2019)

- Hayton, J. C., Allen, D. G., & Scarpello, V. (2004). Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 7(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428104263675

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Holtom, B. C., Mitchell, T. R., Lee, T. W., & Eberly, M. B. (2008). Turnover and retention research: A glance at thepast, a closer review of the present, and a venture into the future. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 231–274. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520802211552

- Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289447

- International Labor Organization (2008), International standard classification of occupations, available at http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/isco08/index.htm (accessed 10 December 2019)

- Jiang, L., Xu, X., & Hu, X. (2019). Can gossip buffer the effect of job insecurity on workplace friendships? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071285

- Jyoti, J., Dimple, & Dimple, D. (2022). Fun at workplace and intention to leave: Role of work engagement and group cohesion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(2), 782–807. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2021-0704

- Karl, K. A., & Peluchette, J. V. (2006). Does workplace fun buffer the impact of emotional exhaustion on job dissatisfaction? A study of health care workers. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 7(2), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051811431828

- Karl, K., Peluchette, J., Hall-Indiana, L., & Harland, L. (2005). Attitudes toward workplace fun: A three sector comparison. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 12, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190501200201

- Karl, K. A., Peluchette, J. V., & Harland, L. (2007). Is fun for everyone? Personality differences in healthcare providers’ attitudes toward fun. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 29(4), 409–447. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25790702

- Keashly, L., Hunter, S., & Harvey, S. (1997). Abusive interaction and role state stressors: The relative impact on student residence assistant stress and work attitudes. Work and Stress, 11(2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379708256833

- Kramer, R. M. (2010). Collective trust within organizations: Conceptual foundations and empirical insights. Corporate Reputation Review, 13(2), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2010.9

- Kurland, N., & Pelled, L. H. (2000). Passing the word: Toward a model of gossip and power in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 25(2), 428–438. https://doi.org/10.2307/259023

- LePine, J. A. (2003). Team adaptation and postchange performance: Effects of team composition in terms of members’ cognitive ability and personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.27

- Lesener, T., Gus, B., & Wolter, C. (2019). The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work and Stress, 33(1), 76–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1529065

- March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. John Wiley.

- McDowell, T. (2004), “Fun at work: Scale development, confirmatory factor analysis, and links to organizational outcomes”, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Alliant International University.

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

- Michel, J. W., Tews, M. J., & Allen, D. G. (2019). Fun in the workplace: A review and expanded theoretical perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 29(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.03.001

- Nyhan, R., & Marlowe, H. (1997). Development and psychometric properties of the organizational trust inventory. Evaluation Review, 21(5), 614–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X9702100505

- Owler, K., Morrison, R., & Plester, B. (2010). Does fun work? The complexity of promoting fun at work. Journal of Management and Organization, 16(3), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.16.3.338

- Peluchette, J. V., & Karl, K. A. (2005). Attitudes toward incorporating fun into the health care workplace. The Health Care Manager, 24(3), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1097/00126450-200507000-00011

- Plester, B., Cooper-Thomas, H., & Winquist, J. (2015). The fun paradox. Employee Relations, 37(3), 380–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2013-0037

- Plester, B., & Hutchison, A. (2016). Fun times: The relationship between fun and workplace engagement. Employee Relations, 38(3), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-03-2014-0027

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments and Computers, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

- Preston, C. C., & Colman, A. (2000). Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychologica, 104(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-6918(99)00050-5

- Robinson, D., Perryman, S., & Hayday, S. (2004), “The drivers of employee engagement—Report 408 [White Paper]”, London: Institute for Employment Studies. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/408.pdf (accessed 10 December 2019).

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. The Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

- Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout and engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57(2), 173–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00285.x

- Schmitt, T. A. (2011). Current methodological considerations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(4), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282911406653

- Sluiter, J. K., van der Beek, A. J., & Frings-Dresen, M. H. (1999). The influence of work characteristics on the need for recovery and experienced health: A study on coach drivers. Ergonomics, 42(4), 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/001401399185487

- Sonnentag, S., & Zijlstra, F. (2006). Job characteristics and off-job activities as predictors of need for recovery, well-being, and fatigue. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 330–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.330

- Strömberg, S., Karlsson, J. C., & Bolton, S. (2009). Rituals of fun and mischief: The case of the Swedish meatpackers. Employee Relations, 31(6), 632–647. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450910991776

- Tan, N., Yam, K. C., Zhang, P., & Brown, D. J. (2021). Are you gossiping about me? The costs and benefits of high workplace gossip prevalence. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(3), 417–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09683-7

- Tetteh, S., Dei Mensah, R., Opata, C. N., & Mensah, C. N. (2022). Service employees’ workplace fun and turnover intention: The influence of psychological capital and work engagement. Management Research Review, 45(3), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-12-2020-0768

- Tews, M., Michel, J. W., & Allen, D. (2014). Fun and friends: The impact of workplace fun and constituent attachment on turnover in a hospitality context. Human Relations, 67(8), 923–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713508143

- Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., & Stafford, K. (2013). Does fun pay? The impact of workplace fun on employee turnover and performance. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(4), 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965513505355

- Van Veldhoven, M. (2003). Measurement quality and validity of the ”need for recovery scale”. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(90001), i3–i9. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i3

- Waddington, K. (2005). Behind closed doors the role of gossip in the emotional labour of nursing work. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 1(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWOE.2005.007325

- Waddington, K., Fletcher, C., & Mark, A. (2005). Gossip and emotion in nursing and health-care organizations. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 19(4/5), 378–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777260510615404

- Waren, S., & Fineman, S. (2007). “Don’t get me wrong it’ s fun here but: Ambivalence and paradox in a ‘fun’ work environment”. In R. Westwood & C. Rhodes (Eds.), Humour work and organization (pp. 92–112). Routledge.

- Zapf, D., Seifert, C., Schmutte, B., Mertini, H., & Holz, M. (2001). Emotion work and job stressors and their effects on burnout. Psychology & Health, 16(5), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440108405525