Abstract

Fundamental aspects of contemporary Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are linked to ancient philosophies like Stoicism and Buddhism and have evolved through three generational “waves” that can be traced to the early development of behaviorism. These “waves” are often referred to as Behavioral Therapy, Cognitive Therapy, and Mindful Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (MCBT). As the second wave transitioned into the third wave, prominent theorists rebranded principles and practices that were central to traditional CBT. This has generated confusion and miscommunication among researchers, therapists, and the public, which has hampered progress toward the widespread practice of effective, evidence-based treatment. Because no single branded theory is flexible enough to apply to the broad range of clients a typical practitioner serves, many psychotherapists resort to an “eclectic” approach. While combining elements from different protocols can be effective, this approach sacrifices the structure provided by the CBT theoretical paradigm and therefore lacks the integrity of evidence-based practice. To address these challenges, this paper proposes an organizing framework called the Trans-Theoretical Model for Mindful Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TM-MCBT). This model provides three crucial benefits: 1) a flexible and scientifically-grounded structure within which psychotherapists can choose the most relevant evidence-based interventions for their clients; 2) clarity to researchers as they attempt to establish what is happening, when it is happening, and how often; and 3) a common lexicon that enables providers, their clients, researchers, and the general public to continue to integrate the collective wisdom of the ages within contemporary evidence-based practices.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

My clinical experience, taken together with my research and decades-long work in public health have convinced me that mental health services must become a human right. To this end, my passion and appreciation for mental health advocacy and education continue to focus on eliminating the stigmatization of people suffering from mental illness, especially for those who can’t afford services. To further my efforts, I recently established the Alive and Well Foundation, Inc., which is committed to raising funds to pay for quality services for those who need them, without consideration for their ability to pay. My dedication to ensuring that everyone who needs it, receives quality care has motivated me to develop and promote the Trans-Theoretical Model for Mindful Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TM-MCBT) framework. This model and my new book, Wise Up, Change is Hard: 8 Science-Based Steps for Making it Stick, are intended to help mental health professionals, their clients, and the general public benefit from ancient principles and practices that have modern-day relevance and have been demonstrated to help individuals, couples, and families develop resilience and achieve personal fulfillment and authentic happiness.

1. Introduction and review of literature

Over the past several decades, a range of branded therapies based on the fundamental principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has emerged. They share the same core ideas but rename and reorganize them, disguising the significant commonalities between different approaches. This confuses both psychotherapists and patients, who struggle to identify meaningful distinctions between therapies and choose the most appropriate course of action. It also complicates the collective efforts of researchers to study the effectiveness of CBT. This paper proposes a flexible model that preserves the core concepts and original vocabulary of CBT while incorporating recent developments in its theory and practice. This Trans-Theoretical Model for Mindful Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TM-MCBT) model can serve as an umbrella that allows the many distinct “brands” of CBT to be considered as a group of closely related therapies.

To understand how the field arrived at this point and why such a model is valuable, it is necessary to examine the development of CBT over time. Its scientific, theoretical, and historical roots date back to the first generations of thinkers who sought to formalize the study of human thought and behavior. This began with William Wundt, who established the Institute for Experimental Psychology at the University of Leipzig, the first experimental laboratory dedicated to psychological research, in 1879. This marked the establishment of psychology as a scientific endeavor, but from the field’s earliest days, two divergent approaches emerged.

One, epitomized by Sigmund Freud, attempted to infer unobservable mental structures and processes from observable behavior. In 1886, Freud began his clinical practice in Vienna, Austria and developed the process of psychoanalysis, also known today as talk therapy (Freud, Citation1938). This approach relied on extensive conversation between the analyst and patient, usually focused on the patient’s childhood, and sought to identify the root cause of dysfunctional behavior. From a narrow sample of patients, Freud constructed extensive theories about the human psyche that were difficult, if not impossible, to test empirically or generalize to the population at large.

The other approach emphasized rigorous, empirical research, focusing on measuring and manipulating observable behavior without making unsubstantiated inferences about the inner processes behind it. Among the founders was James McKeen Cattell, who became the first professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania in 1888 and published Mental Tests and Measurements, marking the advent of psychological assessment (Cattell, Citation1890). Soon after, William James (Citation1890) published the Principles of Psychology, one of the most prominent books in modern psychology, which argues that “psychology is the science of mental life” (p. 3). Around the same time, Alfred Binet advanced the study of psychodiagnosis and Ivan Pavlov published his work on classical conditioning. From these foundations grew the movement towards the evidence-based psychotherapy that became known as CBT.

1.1. First-wave CBT

Although there were hints of science during the early phases of psychology, the practice was mostly “smoke and mirrors” until the early- to mid-20th century, when John B. Watson became interested in Pavlov’s work and went on to establish the school of Behaviorism (Seligman, Citation2004). At around the same time, B. F. Skinner began to popularize behaviorism and the importance of grounding psychology in science. To this end, Skinner developed both behavior analysis and operant conditioning and established a school of experimental research psychology.

Joseph Wolpe, a South African psychiatrist, learned from the work of Watson and Skinner. Wolpe’s contemporary reciprocal inhibition techniques, like systematic desensitization, further revolutionized behavioral therapy and the importance of scientific rigor in psychotherapy (Wolpe, Citation1968). Taken together, the works of Watson, Skinner, and Wolpe mark the point in history when the field of psychology began to employ well-defined and strictly validated scientific principles aimed at understanding how to reduce problematic manifestations of behavior (Hayes, Citation2004). Their works also make up what is often termed the “first wave” of CBT.

1.2. Second-wave CBT

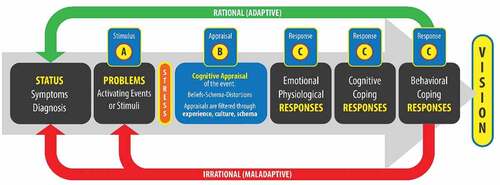

The second wave leading to contemporary CBT theories continued the focus on integrating science into psychology. Cognitive therapy scholars benefitted from the collective wisdom of ancient Stoic philosophers, such as Seneca, Epictetus, and Emperor Marcus Aurelius, as evident in the writings and theories of the two most prominent cognitive psychotherapists. Albert Ellis (Citation1958) was influential for the development of the action-oriented Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy and the ABC Technique of Irrational Beliefs, which proposed interventions during three stages: an activating event, a perceived belief about the event or adversity, and the consequential feeling or behavioral response. Similarly, Aaron T. Beck (Citation1976) coined the term Cognitive Therapy to describe the process of resolving problems by modifying dysfunctional thinking and behavior. These therapeutic models paved the way for other significant contributions that helped clients improve their wellbeing by recognizing and reformulating irrational beliefs.

Several other prominent theorists and practitioners popularized Cognitive Therapy during this time. David Burns, a psychiatrist and student of Aaron Beck, published an influential bestselling book titled book called Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy (Burns, Citation1980). Donald Meichenbaum is known for his development of cognitive-behavioral modification and his book, Cognitive Behavior Modification: An Integrative Approach (Meichenbaum, Citation1977). Independent of the clinicians, Richard Lazarus focused on the research of emotions and coping and developed the theories of Cognitive Appraisal Theory of Emotion and the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984).

1.3. Third-wave CBT

The third-wave CBT theorists borrowed liberally from Buddhism to empower clients to become more mindful and accepting of their thought patterns. The concept of mindfulness as an intervention can be traced to the ancient Indian Vipassana meditation technique (Sharma et al., Citation2012). This type of meditation involves remaining psychologically present with what happens around you and then consciously and reflectively responding (Sharma et al., Citation2012). As a result of the integration of Buddhist principles into psychological interventions, clients could modify their behavior, restructure their cognitions, and regulate their emotions to achieve their goals. For example, Zindel Segal developed Mindfully Based Cognitive Therapy, Steven Hayes created Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to embrace thoughts and feelings, Daniel Siegel encouraged awareness about Mindfulness, and Marsha Linehan created Dialectical Behavioral Therapy to transform negative thinking and patterns into positive behavioral changes (Hayes, Citation2004; Linehan, Citation1993; Segal et al., Citation2013; Siegel, Citation2018).

Furthermore, concurrent with and mostly independent of the third wave evolution of CBT, James Gross developed a highly relevant theory of emotional regulation. As with the writings of both second and third wave theorists, Gross pointed to the need to track how individuals are stimulated by stress-inducing situations, the appraisal that immediately follows these stimuli, and the ensuing responses (J. J. Gross, Citation2001; J.J. Gross, Citation1998).

1.4. Resolution to challenges of third-wave CBT

As the transition took place from second- to third-wave CBT theories, prominent theorists began to rebrand traditional CBT. Examples include Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which is based on the Relational Frame Theory (Hayes, Citation2004), Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (Linehan, Citation1993), Schema Therapy (Young et al., Citation2003), and T.E.A.M. therapy (The Feeling Good Institute, Citation2018). All of these are fundamentally similar to theories developed by Skinner, Ellis, Beck, and Meichenbaum (A. C. Gross & Fox, Citation2009). This proliferation of CBT-based therapy brands has generated three major problems for practitioners, researchers, and the public.

The first is the lack of a common lexicon, which complicates communication for anyone seeking to understand, teach, or debate CBT. For new psychotherapists, the proprietary language associated with each therapy brand masks the similarities as well as the meaningful differences between approaches. It impedes therapists’ mastery of the skills necessary to support clients in achieving sustainable success. This presents a significant risk to clients, particularly given that CBT-based therapies are time-limited and require a collaborative therapeutic relationship to target and change the beliefs, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. The confusing vocabulary also makes it more difficult for clients to make informed choices about what type of therapy to seek and from whom.

The second problem is difficulty moving our scientific understanding of psychotherapy forward. Significant effort has gone into synthesizing the field’s empirical findings in recent years, but the outcome remains murky and highly controversial (Cuijpers et al., Citation2020; Hofmann, Citation2020). With so many different brands of therapy, there are relatively few studies of each one, and their results are difficult to compare or generalize. Most studies show similar effect sizes, but with no standardized approach or vocabulary, is it unclear whether different therapies are targeting the same underlying psychological mechanisms. Publication bias also becomes a serious problem, since many researchers have a vested interest in the success of a given brand of therapy.

In addition, although many of the contemporary “brands” of psychotherapy have been effective in research studies, their protocol-based nature is not amenable to evolution over time. It has long been understood that static theories remain relatively inflexible in their ability to account for the complexities of each unique client case and the state-of-the-art advances in behavioral science and psychotherapy (Cole et al., Citation1993). In other words, even though many evidence-based psychotherapies like Dialectical Behavioral Therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy have proven useful in providing a structured approach to intervention development, their structure can become self-defeating in the face of advancing developments in the field that better account for previously unexplained variance in client outcomes.

The third problem is psychotherapists’ use of an eclectic approach that risks departing from evidence-based practice. No single branded therapy is universally applicable, and most therapists see a wide variety of problems every day (Feeling Good, (Citation2020). 047). So, many end up applying a mixed bag of intervention tools and techniques that seem relevant to the client at hand. This so-called “eclectic approach” has been encouraged by some prominent practitioners, such as David Burns, who has created an e-book entitled Tools, Not Schools, of Therapy. However, by removing intervention techniques from the larger theories in which they were intended to function, therapists sacrifice the foundation of empirical evidence on which the theories rest. They also risk misunderstanding those techniques and applying them in ways that compromise their effectiveness.

To ensure that clients master the skills they need to overcome their challenges, interventions must be based on scientifically sound foundations that adequately impact the root causes of clients’ problems. Furthermore, they should be flexible enough to accommodate advancements in behavior modification techniques. Most importantly, therapists should not feel obligated to adhere to any one particular model. No single approach is universally applicable, hence the ongoing evolution of CBT. The Trans-theoretical Model for Mindful Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TM-MCBT) addresses this dilemma. As described in the remainder of the paper, this model is an organized, systematic, and flexible structure that incorporates first, second, and third wave CBT theories and, in many ways, lays the groundwork for a 4th wave of comprehensivelly based and systematically delivered approaches to evidence-based care.

The principal advantage of this approach is that it combines the flexibility of an eclectic approach with the structure of a theory. Moreover, it does not restrict mental health professionals to one approach in the process of determining the tools and techniques that are most relevant to their clients’ needs. Instead, the proposed framework encompasses the discussed CBT principles in a way that is both thorough and comprehensive. TM-MCBT explicitly facilitates the interventions of choice across the model, so that researchers can establish what is happening, when it is happening, and how often within the framework of the model. In other words, in the process of developing interventions using the model, the psychotherapist effectively creates and intervenes “theories of action” or “logic models” that carefully explicate the course of action outlined in the TM-MCBT treatment plan. As a result, practitioners have the flexibility to select the best practices from evidence-based theories and apply these practices within the structure of the TM-MCBT, while at the same time, researchers can observe whether or not the intervention was delivered as planned.

2. The TM-MCBT model development

As discussed, the TM-MCBT is an organizing framework that incorporates evidence-based principles and practices that support CBT. It is trans-theoretical because it incorporates multiple theoretical models that have been used to formulate evidence-based treatment, including the ABC Technique of Irrational Beliefs (Ellis, Citation1958), the Cognitive Appraisal Theory of Emotion (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), the Cognitive Triad Model (Beck, Citation1976), and the Process Model of Emotion Regulation (J.J. Gross, Citation1998).

The TM-MCBT is also trans-diagnostic because it relies on identifying the root causes of the presenting problems rather than using criterion-referenced diagnostic categories. Once these causes are identified, the same organizing framework that is used to identify the clients’ problems and corresponding diagnosis, guides the practitioner in the process of selecting and integrating evidence-based tools and techniques that address the root causes of the identified problems.

Furthermore, as a part of the psycho-education process that is a necessary component in a standard course of evidence-based CBT, the practitioner teaches the TM-MCBT to the clients, who learn to systematically identify the source of their problems and better understand why specific interventions are selected to address these issues. The practitioner assigns “homework” so that the clients successfully master the skills for continued sustainable success.

3. Theoretical conceptualization of TM-MCBT

As displayed in Figure , every stage in the TM-MCBT requires learning and practicing mindfulness, which has been defined as learning to become aware of and pay attention to what is happening in your mind, your body, and your environment. Specifically, as it relates to implementing the TM-MCBT, clients must practice mindfulness and acceptance skills as they learn to become aware of the details regarding:

Their personal status;

Their goals and value-based aspirations (personal vision);

Their problems (activating experiences and stimuli);

How their problems induce stress;

The amount of stress they are experiencing;

Ways to mitigate stress;

The cognitive appraisal that happens when they are activated by their stress-inducing problems;

The emotional and physiological responses they experience as a consequence of their problems and cognitive appraisals;

Their cognitive and behavioral coping responses;

The personal and therapeutic goals and vision; and,

Their ability to utilize the experiences of thoughts and actions as feedback on their path to progressing towards achieving their goals and vision.

3.1.a. Stage 1a: personal status (symptom diagnosis)

The Personal Status stage of the model involves the symptom diagnosis as the psychotherapist examines the overall status of their client. The therapist uses the qualitative and quantitative data collected from the personal interview and the administration of valid and reliable instruments to (a) determine whether clients meet diagnostic criteria for any psychiatric disorders, and (b) describe the Mental Status, Symptoms, Impairments in Daily Functioning; Principal Diagnosis; Provisional Diagnosis, Rule Outs, and V-Codes. Fundamentally, the components of this stage provide a baseline that can serve as a reference point across the therapeutic process to quantify the progress.

Stage 1a also involves the psychotherapist introducing the clients to the fundamental skill of mindfulness. They learn to monitor their own status using subjective measures that relate to how well they are progressing toward their personal and therapeutic goals. This begins the process of building the clients’ self-awareness, which grows over the course of therapy.

3.1.b. Stage 1b: developing a personal, value-based Vision

Although Stage 1b, Vision, is placed on the far-right side of Figure , it is addressed simultaneously with Stage 1a. At the same time that the psychotherapist is discerning the diagnostic status of the clients, the psychotherapist helps them clarify their values and develop a personal vision of what the client wants to:

BE (calm, successful, thin, on time, confident, faithful, disciplined, fun, trustworthy, etc.),

DO (graduate from college, get married, travel around the world, write a book, etc.), and

ACQUIRE (own a new car or home, get a great job, etc.)

This stage is positioned on the far-right side of the model because it helps the psychotherapist and their clients see that everything the client thinks (cognitive coping responses) and does (behavioral coping responses) to mitigate the stress caused by their problems should align with their ultimate vision. It provides the clients with a purpose and direction that can be used to determine whether or not the things they choose to think and do in response to their life experiences are adaptive or maladaptive in achieving their value-based vision. This is similar to the emphasis on value components highlighted in Steven Hayes’ Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Hayes, Citation2004).

Therefore, this stage provides standards both the psychotherapist and the clients can use to hold the clients accountable and help them live more authentically. A critical activity in this stage is repeated internalization of the vision by the client, using a meditation process that can involve visual aids and music. This further develops the clients’ mindfulness skills by repeatedly focusing their attention on their deepest values and most cherished goals.

In summary, mastering this step requires the clients to mindfully: 1) clarify values, 2) create a personal, value-based vision that represents what they want to feel, acquire, do more or less of, and become, and 3) align their thoughts and actions with this vision.

For example, if a female client’s vision is to graduate from a university, anytime she thinks or does things that undermine this goal, she is acting out of alignment or, as Figure suggests, she is thinking and acting irrationally —maladaptively.

3.2. Stage 2: problems (activating events or stimuli)

Problems represent activating events that may trigger stress, such as the death of a loved one, a rape, or a painful fall. Problems are also those people, places, and things (stimuli) that we encounter daily that cause stress. They come in all sizes, from small to very large. From a psychological perspective, problems are those stimuli we register in our minds as discrepancies between the way things are and the way we would like them to be. In a broad sense, a problem exists when we become aware of a significant difference between what actually is and what is desired.

For example, if you wake up with pain in your shoulder and you do not want to experience pain, you have a problem. If the undesirable pain is severe, the discrepancy between your desire to be “pain-free” is significant. Therefore, you have a big problem, which causes stress and motivates you to make coping decisions. Any coping decisions you make—thoughts or behaviors you engage in—that do not align with your goal of eliminating your shoulder pain are irrational and maladaptive.

When working with clients, it is essential to remember that the stimuli labeled or perceived as problems may be different for each person. What is perceived as a problem for one individual may be quite different from what is considered problematic to that person’s spouse, friend, child, or neighbor. For example, an extrovert may love to be the center of attention in public settings, while a shy introvert may be terrified of such a situation. Similarly, some people love to exercise while others hate to sweat. Some people desire great wealth, while others are satisfied with relatively smaller means. Some parents expect perfection from their children, while others are happy if their children are not incarcerated.

Therefore, to successfully navigate the Problems stage, the psychotherapist helps the clients learn to 1) mindfully identify problems (activating events or triggers), 2) consider how the problems will impact personal vulnerabilities and resilience, 3) distinguish between problems that are caused by life-events versus problems that are self-induced (e.g., ruminating about not being good enough), 4) reduce or eliminate self-induced problems, 5) learn and apply impulse control techniques that mitigate the emotional impact of personal problems, and 6) ultimately learn to use problems to become stronger.

This involves teaching clients to apply their growing mindfulness skills in the stressful moments of their daily lives. This is a crucial step—practicing mindfulness is more challenging when one is experiencing emotional or physical distress, but it is under these conditions that it is most necessary and provides the greatest benefits. To this end, the psychotherapist helps the client think through the following questions related to the problems:

Who are the people and/or the places, situations, and things that activate you?

How can you avoid, prevent, or change these things?

What is a specific problem you need to work on?

What thoughts can you think about or do to reduce your self-induced problems?

What thoughts can you think about when you are experiencing a problem that will reduce the stress caused by the problem and help you effectively solve the problem?

3.3. Stage 3: stress

Stress is a normal human response to problems. When people, places, or things are not the way we want them to be, we experience stress, which is usually painful and motivates us to respond to the problem. Stress is a natural part of life, starting from birth, and it can be an essential motivator to escape from a dangerous situation or to help a person remain energetic and alert. However, when stress is disproportionate to the threat presented by a given problem, or if it remains elevated even when the threat is absent, it inhibits rather than motivates problem-solving. Over time, this unhealthy stress can cause permanent physical and emotional damage.

In this stage, the psychotherapist teaches the clients to manage their stress so that it does not cause chronic psychological or physical pain. Intolerable stress causes clients to experience urges, impulses, and temptations to think or do things to reduce the pain immediately. These thoughts and actions are called coping decisions, and quick-fix solutions often have long-term costs. The goal of this stage is to reduce stress to healthy, tolerable levels so that it does not overwhelm the client’s ability to make healthy thoughtful choices.

Successfully mastering the Stress stage requires the psychotherapist to help the clients become mindful of the stress in their lives by 1) inoculating themselves to stress, 2) observing how much stress they are experiencing, 2) considering stress-related symptoms they are experiencing, 3) identifying the root cause of their stress, and 4) learning to apply adaptive techniques that will dampen the client’s arousal, as they regulate their emotions and rationally manage their stress.

3.4. Stage 4: cognitive appraisal

Whenever you experience a problem, such as an activating event, you typically experience two levels of appraisal (J.J. Gross, Citation1998). These appraisals are automatic and many times outside of your awareness. Your first or primary appraisal is an assessment of the significance of the event and an assessment to determine whether the event is a threat or opportunity. You may assess whether there is danger and if the event relates to your goals. Your secondary appraisal considers your ability to cope or take advantage of the situation. Both appraisals are filtered through your experiences, culture, and core beliefs, known as interpretive schema.

Following J.J. Gross (Citation1998) Process Model of Emotion Regulation, the psychotherapist should first help the clients select an event that provokes an emotional response that may affect the clients’ well-being or ability to achieve goals (situational selection). The situation should be discussed in a way for there to be a modest potential to modify the emotional impact of aspects of the situation (situational modification). Next, the professional should work with the clients to select a focused aspect of the case to modify the emotional impact (attentional deployment). This would then follow by cognitively changing the way the clients interpret the event by identifying one of many meanings that can be attributed to a situation. This meaning should be associated with behavioral, experiential, and physiological responses. Then, the psychotherapist should collaborate with the clients to influence and modulate the emotional physiological, cognitive, and behavioral responses (response modulation, Stages 5–7).

In the Cognitive Appraisal stage, clients must extend their mindfulness to their automatic appraisals of the problems they experience. Mastering this requires 1) understanding what maladaptive schema, irrational core beliefs, and cognitive distortions are and, why they are essential, 2) using mindfulness techniques to determine whether or not they have any of these and, if yes, which ones, and 3) utilizing techniques to restructure the specific maladaptive schema, irrational core beliefs, and cognitive distortions that cause problems. Furthermore, restructuring these beliefs and schema requires 1) identifying the internal stories that reflect them, 2) creating new, more adaptive stories, and 3) practicing these new stories until they become automatic.

3.5. Stage 5: emotional and physiological responses

Once clients develop an awareness of their Cognitive Appraisal processes, they can begin to manage their responses to problems. Emotional and physiological responses are typically perceived first, and addressing them first makes it easier to manage subsequent thoughts and behavior. Unlike Stage 3, which focused on reducing stress symptoms to avoid getting overwhelmed and to enable mindfulness, the goal of this stage is to identify and modify specific emotions.

To master this stage, clients must become mindful of the content and causes of their emotions. The psychotherapist will teach them to 1) notice and describe the emotional distress they experience, 2) identify what is causing these symptoms, 3) understand how to prevent the causes of the distress, 4) learn emotional regulation skills to inhibit or modulate negative emotional and physical symptoms, and 5) learn emotional and physiological regulation skills to help tolerate short-term or long-term emotional or physical pain.

3.6. Stage 6: cognitive coping responses

The thoughts a person uses to eliminate problem-induced stress and the associated pain are called coping thoughts or cognitive coping responses. These are the stories clients tell themselves to explain why the problem happened and to justify their interpretation of what it means. Rational coping thoughts improve clients’ status over the long term and help them achieve their vision, whereas irrational thoughts harm their wellbeing and often lead to more problems. In this stage, clients learn to be mindful of what they think in response to their problems. Their mindfulness grows to include the stories they tell themselves about stress-inducing situations, which enables them to challenge and alter irrational coping thoughts.

More specifically, for a coping thought to be rational it must 1) be logical and consistent with known facts and reality-based truth; 2) produce desired emotions; 3) help overcome current and future problems; 4) foster personal growth, development, and happiness; 5) encourage learning from the past, preparing for the future, and living in the present; 6) support personal and interpersonal goals, and 7) embrace an optimistic view of one’s self and future prospective.

3.7. Stage 7: behavioral coping responses

Rational coping thoughts tend to result in rational coping actions because when we think “better,” we feel “better,” and will consequentially perform “better.” Hence, as with coping thoughts, behavioral coping responses (or coping actions) are classified as either rational or irrational. Similar to rational coping thoughts, rational coping actions can be further clarified with specific criteria. To be rational, a behavior must 1) be grounded in reality to support their intended effects, 2) contribute to health promotion, well-being, personal growth, and emotional maturity, 3) increase happiness, 4) help clients feel the way they want to feel, and 5) facilitate achieving goals and realizing the personal vision.

As with irrational coping thoughts, irrational coping actions 1) are not logical, 2) do not help people overcome their problems, 3) are destructive, and/or 4) undermine personal goals. Furthermore, irrational coping actions are like short cuts to overcoming pain. Those who prefer these “quick fixes” to stress (e.g., drinking to relax, smoking marijuana to forget, quitting a job to escape an uncomfortable workplace, or retreating from a stressful situation—like giving a public presentation) tend to become emotionally weaker over time. Psychotherapists must help clients understand that the worst possible behavioral response they can do when they have an anxiety disorder is to retreat from people, places, and things that make them anxious. This is because although the retreat relieves the stress caused by the anxiety-provoking situation, at the same time, the retreat reinforces the irrational behavior the person is trying to overcome. Mindfulness is the primary skill that enables clients to recognize their irrational behavior patterns, prepare alternative rational responses, and maintain sufficient awareness to implement those rational responses when problems arise.

3.8. Relationship to other CBT-based models

The TM-MCBT outlined above incorporates the elements and processes at the core of all other “branded” therapies with roots in CBT. The advantage of this model is that it organizes these concepts in a flexible, generalizable way without dictating specific treatment techniques that must be used to reach the goals of a given stage. It is an elaboration of Albert Ellis’s ABC model, the fundamental theory behind CBT, into clinically useful stages. These stages represent what clients experience each time they confront a problem, and they also serve as clear steps that clients can master progressively. Within each stage, there are many options for effective therapeutic tools, which allows psychotherapists to choose the techniques that best fit a given client.

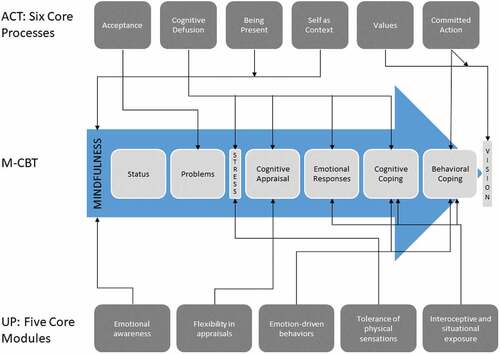

Figure illustrates how the TM-MCBT encompasses the core concepts in two other empirically-support therapies based on CBT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and the Unified Protocol (UP). While these therapies have demonstrable merit, the proliferation of branded variants on CBT such as these creates confusion for psychotherapists and clients alike, and it complicates efforts to study CBT outcomes. As stated previously, the purpose of the TM-MCBT is to organize the central ideas of all CBT-based therapies in a flexible way that is useful for treating any client, regardless of their specific challenges or diagnoses.

4. Practical and conceptual application of TM-MCBT

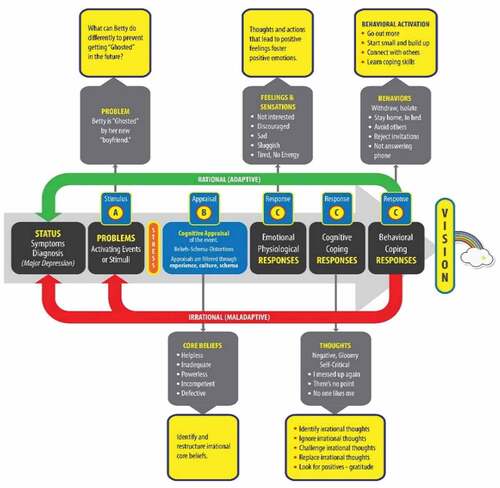

As a practical application of TM-MCBT, the example illustrated in shows a client named Betty who meets the diagnosis threshold for major depression, experiencing a problem or activating stimulus (“getting Ghosted”). She has expressed that her personal vision is a desire to become happier. The sequence outlined in the TM-MCBT process for identifying Betty’s status and goal, in turn, characterizes that a maladaptive coping response can lead to isolation and a depressed mood.

This activating event (”Getting Ghosted”) causes Betty to experience stress, which, in turn, brings up several irrational core beliefs, including a sense of helplessness, inadequacy, powerlessness, incompetence, and feeling like she is defective. Her cognitive appraisal then causes Betty to feel like she is no longer interested in dating. She feels discouraged, sad, sluggish, and tired. Her irrational cognitive coping responses (the stories she starts telling herself) are self-critical and include statements like “I messed up again,” “there is no point to dating,” and “no one likes me.” Betty’s irrational coping behaviors include avoiding others, rejecting invitations, not answering the phone, and staying in bed.

Once again, illustrates how the same sequence of steps across the stages of the TM-MCBT was followed to characterize the antecedents of Betty’s problems, including her diagnosis, goals, and personal vision, irrational core beliefs, and maladaptive cognitive and behavioral coping responses. Subsequently, the conceptual application displays the selection and application of CBT interventions. Specifically, her psychotherapist will help Betty become mindful of the situation that is activating her and learn how she can effectively apply adaptive responses. Her psychotherapist will also help Better examine her cognitive appraisal of the event and understand how her irrational core beliefs, including believing she is helpless, inadequate, powerless, incompetent, and defective, can impact how she feels, both physically and emotionally. Moreover, the process will help Betty learn to use her goals and value-based vision as a standard against which she can begin to identify and modify her irrational core beliefs, cognitive distortions, and irrational cognitive and behavioral coping responses. The process will also help guide the selection of interventions, including mindfulness and acceptance, designed to address Betty’s unique situation in a way that is comprehensively based and systematically delivered.

5. Benefits of a trans-theoretical and trans-diagnostic approach

As mentioned previously, the rise of “branded” therapies, which often refresh and rename longstanding principles and practices that fall under the CBT umbrella, has resulted in three significant obstacles to progress in evidence-based psychotherapy. The first is a confusing lexicon that impedes the understanding of core therapeutic concepts, particularly especially for new therapists and clients. The second is a tangled web of empirical research that is difficult to synthesize and vulnerable to bias. The third, and perhaps the most concerning, is the adoption by psychotherapists of an “eclectic” approach that combines interventions from various evidence-based therapies while sacrificing the theoretical structures on which their empirical validity depends.

The TM-MCBT addresses these problems by providing a structure that encompasses multiple theoretical branches of CBT and is independent of any particular mental illness diagnosis. It is proposed not as a new, superior therapeutic protocol but as an organizing framework for the many CBT-based branded therapies that already exist. Both the trans-theoretical and trans-diagnostic qualities offer essential benefits to therapists, researchers, and clients.

As the continued evolution of CBT demonstrates, no single theory applies to all cases or capable of accommodating all advances in techniques or technology. There is a need for a structure that integrates the core concepts of CBT while retaining the flexibility to account for the many variations in its application. The TM-MCBT does this by organizing interventions around the logic of Albert Ellis’s ABC model, which encompasses the defining theoretical elements of CBT. The phases of TM-MCBT represent stages of a client’s experience or development, not specific protocols, so they can accommodate a wide range of intervention techniques without changing the structure of the model. The model’s multiple feedback loops show that these phases do not simply progress linearly from beginning to end but can manifest in more complex ways. This flexibility allows the model to encompass multiple theories within an over-arching structure that acknowledges their commonalities and provides a basis for synthesizing their empirical results.

As the field of psychotherapy moves away from its previous emphasis on discrete diagnoses, any model intended for practical use by therapists and researchers must also be trans-diagnostic. Many branded therapies were developed to treat criterion-referenced diagnostic categories that tend to simplify and devalue critical psychological phenomena that counselors have subjectively labeled and categorized according to a limited set of pre-defined diagnostic criteria (Fusar-Poli et al., Citation2019). This has contributed to an explosion of protocols, manuals, training requirements, and recommendations about different frameworks and theories, which can result in implementation challenges (Gros et al., Citation2016). It is essential to integrate culturally adapted interventions that consider how and why each person is unique, responds differently, and has different beliefs due to variances in biopsychosocial, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds. We may hamper our understanding of the client’s emotions and responses if we subjectively label and treat mental health conditions according to pre-defined diagnoses, rather than considering the holistic, multidimensional factors that affect each individual.

To combat this, the TM-MCBT focuses on core psychological mechanisms rather than symptoms. Its flexibility allows therapists to construct approaches to personal change that are appropriate for different cases without having to navigate multiple treatment frameworks. It is designed to support individuals in learning to recognize, regulate, and balance feelings, sensations, thoughts, and behaviors in a manner that is socially tolerable and sufficiently flexible to permit spontaneous reactions as well as the ability to delay inappropriate spontaneous reactions. By understanding and effectively applying the TM-MCBT, therapists can better understand the strategic integration and application of various cognitive-behavioral therapies. This helps them more effectively identify the root causes of clients’ problems and teach them to modify the emotional impact of situations, irrational, and maladaptive beliefs and responses. As a result, clients are better able to apply adaptive rational cognitions and responses, which are more aligned with the goals of experiencing superior health and wellness outcomes, building closer relations, and living a more purposeful and successful life.

Consequently, the adoption of the TM-MCBT by both practitioners and the research community could result in a paradigm transformation. By integrating theories and frameworks that have been scientifically proven to be effective, rather than relying on continually evolving inspirational theories and subjective interpretations. Therefore, we would ultimately transform the way we identify, diagnose, treat, and prevent mental health conditions due to the increased integration of empiricism and science (Fusar-Poli et al., Citation2019). We would also be able to scientifically help people integrate Buddhist techniques to become more aware, mindful, and accepting of emotions, cognitions, and responses. People would be able to modify their emotions, beliefs, behaviors, and the emotional impact of activating situations for sustainable success, whether they are self-developing or collaborating with a counselor.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Galen Cole

Dr. Galen Cole, Ph.D., MPH, LPC, ABCP is a licensed counselor, board-certified psychotherapist, a nationally certified clinical hypnotherapist, and an integrated-trauma specialist. He provides clinical services to individuals, couples, and families at two different locations in the Atlanta-Metropolitan area. He relies on evidenced-based practices in Trauma-Informed Mindful Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Positive Psychology to help his clients develop resilience and achieve personal fulfillment and authentic happiness. He also conducts intensive training on MCBT across the United States and around the globe. Concurrent with his work in mental health, he has served at the highest levels of government at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He has appeared in television shows, worked in Hollywood, and published numerous scientific papers and books that address both mental and public health issues at the intersection between philosophy and science.

References

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press.

- Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling good: The new mood therapy. William Morrow and Company.

- Cattell, J. M. (1890). V.—Mental tests and measurements. Mind, os-XV(59), 373–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/os-XV.59.373

- Cole, G. E., Holtgrave, D. R., & Rios, N. M. (1993). Systematic development of trans-theoretically based behavioral risk management programs. 4 RISK: Health, Safety, & Environment 1990-2002, 4(7), 67–91. https://scholars.unh.edu/risk/vol4/iss1/7/

- Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., de Wit, L., & Ebert, D. (2020). The effects of fifteen evidence-supported therapies for adult depression: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy Research, 30(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1649732

- Ellis, A. (1958). Rational psychotherapy. The Journal of General Psychology, 59(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1958.9710170

- Feeling Good. (2020). 047 Tools … not schools of therapy. https://feelinggood.com/2017/07/24/047-tools-not-schools-of-therapy

- The Feeling Good Institute. (2018). What is TEAM therapy? http://www.feelinggoodinstitute.com/feeling-good-institute/what-is-team-therapy

- Freud, S. (1938). An outline of psychoanalysis. Hogarth Press.

- Fusar-Poli, P., Solmi, M., Brondino, N., Davies, C., Chae, C., Politi, P., Borgwardt, S., Lawrie, S. M., Parnas, J., & McGuire, P. (2019). Transdiagnostic psychiatry: A systematic review. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 18(2), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20631

- Gros, D. F., Allan, N. P., & Szafranski, D. D. (2016). Movement towards transdiagnostic psychotherapeutic practices for the affective disorders. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 19(3), e10–e12. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102286

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

- Gross, J. J. (2001). Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00152

- Gross, A. C., & Fox, E. J. (2009). Relational frame theory: An overview of the controversy. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 25(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393073

- Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3

- Hofmann, S. G. (2020). Imagine there are no therapy brands, it isn’t hard to do. Psychotherapy Research, 30(3), 297–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1630781

- James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology: Volume I. Henry Holt and Company.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Linehan, M. M. (1993). Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

- Meichenbaum, D. (1977). Cognitive-behavior modification: An integrative approach. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Seligman, M. (2004, February). The new era of positive psychology. [video]. TEDTalk. https://www.ted.com/talks/martin_seligman_the_new_era_of_positive_psychology

- Sharma, M. P., Mao, A., & Sudhir, P. M. (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive behavior therapy in patients with anxiety disorders: A case series. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 34(3), 263–269. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.106026

- Siegel, D. (2018). Aware: The science and practice of presence–The groundbreaking meditation practice. Penguin Random House.

- Wolpe, J. (1968). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Conditional Reflex, 3(4), 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03000093

- Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. Guilford Publications.