Abstract

To optimize outcomes in Late-Life Depression (LLD), there remains a need for innovative augmentation treatments. Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) is demonstrated as an effective augmentation psychotherapy for LLD in a one-to-one setting. This study investigated the feasibility of implementing Case Manager delivered group PST for LLD in a community setting. The design was a mixed-methods pilot one-group pre-test post-test quasi-experimental feasibility study in adults aged 60+ years meeting criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD). Feasibility measures were inclusion, attendance, and attrition rate. PST was delivered in groups of 6–9 participants over 8 weeks. Participants completed a weekly self-rated depression scale from weeks 1–8, and pre-and post-intervention rater assessed depression and self-rated assessments of quality of life, insomnia, disability, and anxiety. Focus group interviews took place at week 8 for the first and last study cohort. Twenty-nine participants (inclusion rate of 91%) were enrolled, a recruitment rate of 2.2 participants/month. Of these, 26 (90%) completed week 8 assessments and 25 (96%) attended 5 or more PST sessions, while 15 (58%) attended all sessions. Self-rated depression, anxiety, and insomnia scores decreased significantly with medium-to-large effect sizes, while there was non-significant improvement in rater-assessed depression and self-rated disability and quality of life. Qualitative data showed participants found PST an easy-to-use technique and felt empowered and hopeful in recovering from depression. The results justify a replication of the study in a large RCT exploring the efficacy of offering a group-based Case Manager facilitated PST to older adults with LLD, in a community setting. Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT03408821

1. Introduction

Late-life depression (LLD) is overwhelming our healthcare system, and current pharmacological treatment options are limited and inadequate (McCall & Kintziger, Citation2013). Current medication treatment options for LLD rely mostly on antidepressants, offering a mean pooled response rate of 44% compared to 35% with placebo. Additionally, medications are often accompanied by a significantly high rate of adverse effects and discontinuation (Nelson et al., Citation2008). Hence, LLD treatment frequently necessitates augmentation with psychotherapy.

Various forms of psychotherapy have been examined in depression including supportive therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, reminiscence therapy, and problem-solving therapy (PST; Huang et al., Citation2015). Specifically, CBT, life review therapy, and problem-solving therapy may be more effective compared to other therapies (Cuijpers et al., Citation2014; Jonsson et al., Citation2016). Among the available psychotherapy options, there has been increasing interest with PST as it has been shown to improve depression remission rates, improve disability, reduce suicidal ideation, and has been adapted for LLD (Arean et al., Citation2010; Gustavson et al., Citation2016). PST is also effective in preventing major depression in older adults with subsyndromal symptoms (Dias et al., Citation2019). A recent systematic review provides evidence that PST significantly reduces depressive symptoms compared to waitlist control (Shang et al., Citation2021). Therefore, there is substantial evidence for the use of PST in the treatment of depression.

Meta-analyses have demonstrated that group psychotherapy for depression is more effective than treatment as usual (Huntley et al., Citation2012). It may be possible that this is because group therapy sessions are typically longer than individual therapy sessions, or that group therapy provides additional peer support, which is not available in individual therapy (Van Bronswijk et al., Citation2019). Delivering group psychotherapy interventions may help utilize resources more efficiently, increase access to care, and reduce wait-times for treatment interventions. Group CBT interventions have been found to be effective in reducing depressive symptoms in both working age and older adult populations compared to a waitlist control (Krishna et al., Citation2015). However, to our knowledge, PST has not yet been offered in groups by allied health staff such as nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, recreational therapists, and/or occupational therapists.

This study examined the feasibility of training clinicians to deliver PST, via a group-based community setting, and evaluated changes in depressive symptoms as well as comorbid anxiety, disability, and quality of life in community dwelling seniors suffering from mild-to-moderate LLD. The primary hypothesis was that group PST can be successfully implemented via an academic institutional geriatric mental health outreach program through a community library. The secondary explorative hypotheses of this study were that participants may experience improvements in depressive symptoms, quality of life, anxiety, insomnia, and functional disability.

2. Methods

This pilot one-group pre-test post-test quasi-experimental longitudinal study was approved by the Western University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board under approval # 111113 on 14 February 2018 and registered at clinicaltrials.gov with NCT03408821 on 18 January 2018.

The study participants were aged 60 or older (mean 72.8, SD 5.1) and provided valid written informed consent. They met diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) as confirmed by completion of module A of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., Citation2010). Inclusion criteria were as follows: a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17; Hamilton, Citation1960) total score of ≥8 and <24 at baseline; a Mini Mental Status Exam (Folstein et al., Citation1975) score of ≥25; fluent in English, both written and oral; reside in a community setting; have adequate vision and hearing to participate in PST, of either gender and greater than 59 years of age.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: suicidal ideation requiring inpatient admission to hospital for stabilization; an unstable medical condition requiring hospital admission; a life expectancy of less than 6 months or currently receiving palliative care; psychotic symptoms; a lifetime history of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia as per self-report; currently alcohol dependent or have another substance dependence as per self-report; diagnosed with moderate-to-severe dementia as per self-report; and planning admission to a long-term care facility within next 6 months.

3. Study intervention

Problem Solving Therapy (PST) was delivered using the manualized six stages of problem resolution including a) identifying and clarifying the problem, b) setting clear achievable goals, c) brain-storming to generate solutions, d) selecting a preferred solution, e) implementing the solution, and f) evaluation (Mynors-Wallis et al., Citation1995). The CMs taught participants a structured approach to cope with and resolve issues using the six stages of problem resolution. The focus of the PST sessions was on issues the study participants currently had in their life and not on problems from their past.

Participants attended eight weekly sessions of PST lasting 1.5 to 2.5 hours. The trained clinicians utilized PST’s structured approach to help participants cope with and resolve issues (Mynors-Wallis et al., Citation1995). The first session included a welcome, introductions, discussion of group rules regarding confidentiality, an overview of the problem-solving approach and an introduction of the depression/problem-solving cycle. Sessions 2 through 6 started with a review of group rules, followed by a check-in where participants were asked to describe important psychosocial aspects of their lives from the previous week. Each week, one of the participants was asked to volunteer to act as the “problem solver” over the next week for a particular problem that they were interested in addressing. All participants were asked to engage in pleasant activities on a daily basis, noting the date, activity, and how satisfied the activity made them feel on a scale of 0 to 10 (with 0 = Not at all and 10 = Super). The final meeting was used as a time to celebrate the accomplishments of the group, listing all of the problems mentioned and those solved by the participants, an opportunity to share social time together and a discussion of next steps.

The PST groups were led by Geriatric Mental Health Outreach Program clinicians (n = 6) who were trained in a 20-hr PST certification training program in accordance with the University of Washington’s Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions Center. Problem-Solving Therapy was delivered in groups of six to nine participants at a London Public Library. At least two clinicians facilitated each PST cohort group.

4. Measures

A Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) was used to rule out a major neurocognitive disorder (mean 28.83 ± SD 1.39). The MMSE includes 11 items that focus on the participants orientation to time, place, recall ability, and short-term memory. Total scores range from 0 to 30 with higher scores signifying preserved cognitive function (Folstein et al., Citation1975).

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) is a 17-item rater-administered scale that has items scored on a scale of 1–3 or 1–5. The HRSD-17 is completed by a trained rater who assesses severity of depression in the domains of mood, guilt, suicidal ideation, sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, weight gain/loss, hypochondriasis, sexual impairment, anxiety, insight into depressed mood, as well as physiological symptoms of depression and anxiety. Scores on the HRSD-17 range from 0 to 52 with higher scores signifying more severe depression (Bobo et al., Citation2016).

The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G) evaluates the 14 body systems and the severity of comorbid physical illnesses with each on a scale of 0–4, with 0 representing no issue to 4 representing severe problems with that organ system. Five scores are calculated for the scale: the total score, the total number of categories endorsed, the severity (ratio of total score/number of categories endorsed), and the number of categories at level 3 or level 4. Total scores range from 0 to 56 (Miller et al., Citation1992).

EuroQol 5 Dimension 5 level (EQ-5D-5 L) assesses participant’s self-rated health state on that day. Participants are asked to indicate how much difficulty they have in a health dimension using one of the five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, or extreme problems. Higher scores indicate greater severity of problems with a health dimension or overall. Participants are also asked to rate their current health state on a scale from 0 (“the worst health you can imagine”) to 100 (“the best health you can imagine”; Tawiah et al., Citation2019).

The Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) is an 8-item, self-rated measure of the extent of sleep difficulties with each item representing a different aspect of sleep. Ratings are from 0 to 4, with 0 being no difficulty with the item and 4 being the most difficulty with the item. Scores range from 0 to 24 (Soldatos et al., Citation2000).

The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2 (WHODAS-2) is a 36-item, self-rated questionnaire assessing participant’s difficulties, due to physical- or mental-health issues in activities over the past 30 days. Participants provide responses from 1 to 5, with 1 being “none” and 5 being “extreme or cannot do.” Higher scores indicate greater difficulty with the total score ranging from 0 to 100 (Garin et al., Citation2010).

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) is a 7-item self-rated measure of anxiety with each item scored from 0 to 3. Total scores range from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating greater anxiety symptoms (Kroenke et al., Citation2001).

5. Procedures

Potential participants were recruited from patients of the London Geriatric Mental Health Outreach Team, community healthcare providers, or recruited via a paper poster placed at London Public Library (LPL) locations, on the LPLs webpage, or in the LPL magazine. Participants were recruited from February 2018 until March 2019. Upon completing written informed consent, participants were screened as per inclusion and exclusion criteria by the Research Assistant (RA), administered an MMSE, section A of a Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., Citation1998), and a HAM-D17. Following the administration of these scales, participants meeting eligibility criteria were invited to participate in this study. The initial assessment also included administration of a CIRS-G, EQ-5D-5 L, AIS, WHODAS-2, GAD-7, and collection of demographic data. Following the final PST session, participants attended a final assessment with the RA which included a HAM-D17, EQ-5D-5 L, AIS, WHODAS-2, GAD-7, a Likert scale to measure acceptability of the PST program. Following the first groups and last groups, completion a focus group was conducted at the London Public Library to collect qualitative data to determine the long-term sustainability of PST for seniors in London, ON and the surrounding area.

6. Data analysis plan

Quantitative data was analyzed using a paired-samples t-test for a dataset of available values. The baseline characteristics of those who attended all 8 sessions of PST were compared to the baseline characteristics of those who attended 0–7 sessions of PST using a Chi-Square test for independence for categorical variables and an independent samples t-test for continuous variables. An estimate of potential clinical significance was calculated by Hedges’ g, which is generally a better estimate when the sample size is smaller (Hedges, Citation1981). Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS Statistics Software version 25 and using a significance level at p < 0.05.

The qualitative component of the study used a descriptive-exploratory method to explore perspectives of the participants to better understand their viewpoint in relation to PST (Fain, Citation2017). Data collection took the form of focused group discussions (FGDs) using an interview guide. Focus group interviews took place at week 8 for the first and last study cohort. An inductive thematic analysis rooted in Braun and Clark’s six-phase framework for thematic analysis was completed on the transcribed data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Two research team members performed open coding for developing and modifying codes as they interpreted the data followed by aggregating the codes and examining them for patterns to create groups and subthemes.

7. Study fidelity

We collected feasibility outcome measures including total time required to meet our recruitment target (a priori defined as n = 40), total number of potential participants screened, total number of participants meeting eligibility criteria, total number enrolled, rate of attendance, and retention rate.

To measure acceptability of the PST program at Week 8, participants responded to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree to strongly agree” to statements asking participants to indicate if they found the program helpful, the date and time of day to be convenient, the location of the program to be convenient, if they like the program instructors, enjoyed the program, and if they were happier upon completion compared to before starting the program.

8. Results

Participant baseline characteristics are illustrated in . Participants were mostly older age, Caucasian, female, retired, well educated, and having mild-to-moderate depression severity. Participants had a moderately high physical illness comorbidity. Participants had an early onset of their depression, with 86% having had their first episode of depression before the age of 60. About 58.6% of participants had recurrent episodes of depression, with 21% having greater than 10 lifetime episodes. Most participants were on psychotropics with 76% taking at least one psychotropic medication to manage their depression.

Table 1. Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics

Our a priori primary outcome criteria were that we would recruit 40 participants within 1 year. We were able to approach 49 potential participants over a period of 13 months of recruitment, 32 showed interest in the study and of these, 29 (91%) met eligibility criteria (see CONSORT diagram, ). Of those enrolled, our criteria were that 60% would complete the PST program, and we achieved a higher retention rate than planned (n = 26 completed 8 week outcome measures, 90%). Adherence rates were defined a priori as attendance of a minimum of 5 of the planned 8 sessions, and 96% (n = 25 of 26 completers) met these criteria with 58% of participants (n = 15 of 26 completers) attending all 8 sessions.

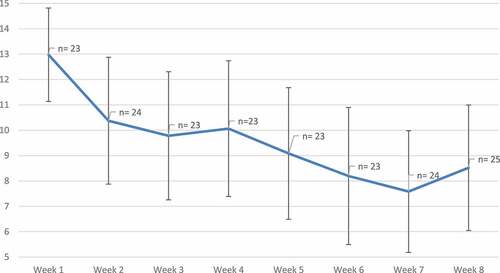

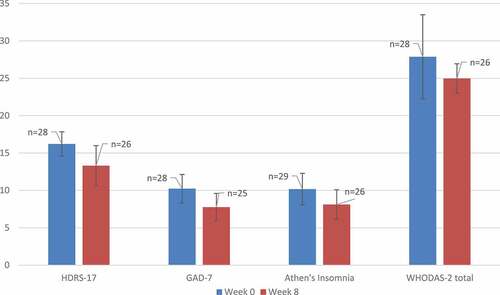

presents changes in symptoms associated with late-life depression in this small cohort. While all results should be read with caution due to the preliminary nature of this study, there were beneficial effects of the intervention with a significant difference in the mean fall in the PHQ-9 scale scores over the 8 week duration with a large effect size (4.41, t = 4.26, degrees of freedom 22, Hedge’s g = 0.79). Additionally, a pre-post independent t-test revealed that there was a significant decrease in GAD-7 (change = —1.98 ± 4.60, p= 0.042) and Athens Insomnia Scale scores (change = —1.69 ± 3.99, p= 0.040). The mean ± 95% confidence interval of mood, anxiety, insomnia, and disability scores are illustrated in .

Table 2. Paired-samples t-test and the corresponding effect sizes of data comparing effects of pre- and post-Problem Solving Therapy intervention on depression and related comorbidity symptoms at baseline (week 0) and end of study (week 8) from available participant data. SD: Standard Deviation, SE: Standard Error, HDRS-17: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder, WHODAS-2: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2, EQ-5D-5 L: EuroQol 5 Dimension 5 Level, VAS: visual analogue scale, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire

Figure 2. Mean change in mood and disability symptoms ± 95% confidence interval . HDRS-17: Hamilton depression rating scale, GAD-7: generalized anxiety disorder, WHODAS-2: world health organization disability assessment.

A pre-post independent t-test of the available complete data and Supplementary Table S1 presents results of the baseline comparison between those who attended all sessions of PST compared to those who attended 0–7 PST sessions. Of note, participants who attended all 8 sessions of PST had a significantly lower baseline GAD-7 score compared to those who were partial attenders (8.36 ± 5.50 vs. 12.11 ± 4.08, p = 0.05). However, baseline HDRS-17 score, PHQ-9, Athen’s Insomnia score, WHODAS-2, or EQ-5D-5 L scores or gender did not differ between those who were perfect attenders compared to those who were partial attenders (Supplementary Table S1). All study completers (n = 26) completed Likert scale evaluations. Ninety-two percent agreed or strongly agreed that the PST program was helpful, 96% strongly agreed that they liked the program instructors and 96% agreed or strongly agreed that they enjoyed the program.

9. Qualitative results: focus group

Of the 29 participants enrolled, 13 took part in two focus groups. Seven major themes and 30 sub-themes were identified emerging from the participant experience (see, ). The first identified major theme, participant preconceptions, identified participant misperceptions but also hope prior to initiating the intervention. The second major theme, appraising PST, outlined participants’ overall impressions of PST including that it is a helpful, useful, and structured technique. The major theme of social impact included the participants’ sense of community with their group and the ability to overcome stigma. The self-growth and development major theme outlined the self-empowerment and increase in self-esteem experienced by participants. Enablers of PST were a major theme that integrated the positive abilities of PST facilitators who overcame barriers and provided a safe environment. The improved symptomology major theme identified reductions in depression and fatigue. The final major theme, proposed actions for enhancing PST, suggested that Canadian patients with LLD could benefit from wider implementation of group PST as an adjunctive therapy.

Study participants found PST to be a helpful and useful technique that they could use independently in the future. Despite initial misperceptions and related anxiety about joining PST, participants felt comfortable and safe while participating. In the end, participants reported that they had developed a sense of community within their study groups. Participants also indicated that the stigma they experience from having a mental health disorder was decreased by discovering that others within their community have similar experiences.

Other themes included preconceptions, appraising PST, social impact, self-growth and development, enablers, improved symptomology, and proposed actions for enhancing PST. Selected subthemes and examples of quotes are transcribed below.

10. Participant preconceptions

10.1. Being hopeful

Before taking part in the study, participants had high hopes for the program outcomes, leading most of them to feel excited. This made most of them excited to take part in the PST. “Personally, I found it hopeful. I have been dealing with depression on and off for my life and any help at all I considered hopeful. Well it (PST) gave me hope that I don’t necessarily have to live with a chronic depression.”

10.2. Misperceptions

Prior to joining the study, some participants were deterred by the title Problem-Solving Therapy. However, this negative association to the title dissipated as they participated through the program. “… When I received this referral, I was not keen at all. The name itself indicates to me that it would be very concrete, and it just didn’t really interest me or excite me but once I got involved with the group, I realized that it is much [more] dynamic than I had initially expected. It gave me a totally different experience than I anticipated. At first I thought well this doesn’t really seem to interest me but then I thought that on experiencing some difficulties, I better get to work and do something and see how it goes and as I said, you know because it is so interactive, we all shared.”

11. Appraising PST

11.1. Helpful

The majority of participants liked the group interaction and sharing components of PST. They believed it was an opportunity to receive help for mental health symptoms. Participants found the program interesting and planned to continue to use the techniques after the program finished. Quote: “The group was so interactive, and we had opportunities to share common experiences and learn from others. When we share; we are not the only person. That’s very helpful just to know that I am not eccentric or unusual in what I am experiencing. These are shared thoughts and experiences that a lot of us [have] at this stage in life.”

11.2. PST as a useful technique

Participants found PST to be a structured, simple, and easy technique. They liked the concept of breaking large problems into smaller, more manageable chunks. “I walked in here the first day overwhelmed. I learned to narrow my focus on one thing instead [of] on the whole thing. The main thing I learned is how to break a problem down into small pieces and I will use that in my life from now on. From something huge that just makes me paralyzed, take it, break it down, and then be able to attack the little piece.”

11.3. Structured program

Participants found it beneficial that facilitators clearly outlined the expectations and rules during the intervention.

“I found that they [facilitators] were so organized and so structured in the way they ran the group that it helped us to make progress in the group. It was very predictable; it was very structured and highly organized.”

12. Social impact

12.1. Sense of community

Participants indicated that they had a sense of entitativity and felt comfortable sharing personal things within the group that they would not normally share with others. The stigma of sharing personal problems within the group was overcome when participants discovered that other members shared similar issues: “If you’re just by yourself the way that you feel and the problems that you’re experiencing tend to blow up into bigger and bigger things. It was interesting to be with a group of people that had not the same but similar issues that they were trying to deal with. You’re talking to people that would understand better than other people, other friends perhaps … I think there’s a certain synergy that comes from other people in the group.”

13. Self-growth and development

13.1. Self-empowerment

Facilitators helped to motivate participants to engage in the program and encouraged them to utilize customized solutions that worked best for them. This empowered participants to act in an autonomous fashion

“They [facilitators] gave the pages for the person who was going to solve that problem of the week to take home … They [participants] had taken ownership of those ideas. [Participants] were then able to follow up on them.”

13.2. Self-esteem

Building connections with other participants during PST helped to break down the stigma surrounding mental health: “We’re all different and we have similar issues … I’ve never found it easy to talk about, and this gave me a feeling that it should be talked about …. Mental health is not a topic that people share easily and that’s absolutely wrong. Considering the age of this group, we’re the generation that nobody talked about it. Families wouldn’t discuss it, didn’t want anyone to know that there were any issues in their family. They thought it reflected on the whole family.”

14. Enablers of PST

14.1. Trust

Participants felt safe and comfortable to share with the group by building trust with the facilitators and other participants.

“… I am understood and kind of inspired through other people to speak about the table [referring to personal problems]. I thought I had the only table. I trusted everyone here. I don’t have any way of explaining that level of comfort, I just felt it.”

14.2. Safe atmosphere

Participants felt comfortable and protected among their peers and the PST facilitators, indicating that they could share very personal things without concern of judgment.

“… I immediately felt safe … I knew that I could share absolutely anything. As a matter of fact, I shared something that I haven’t shared with anyone … I noticed that every single solitary person in this group shared and they talked openly … There wasn’t one who didn’t have things to say that were helpful but I think the facilitators encouraged that …. I was totally, completely comfortable as if I’d known these people for ages.”

14.3. Compassion

The support, empathy, and patience shown by the PST facilitators were welcomed and appreciated by participants. Participants also noticed that facilitators managed to maintain control of the group while still showing compassion.

“Thank God for their [facilitators] patience because sometimes we would go off on a tangent and they would be able to see it and drag us back. I think was critical when you’re talking about limited time … we’re dealing in something that’s hard to quantify and that is personalities. I think that these were natural people and the natural ability to want to help.”

14.4. Sense of humor

Facilitators were noted by participants to be supportive while encouraging self-expression. They did not dismiss ideas and found opportunities for humour, which the participants enjoyed.

“We had some good laughs, which is kind of nice. There was humour involved. Some of the stuff was pretty heavy to us, so that ability to inject humour was a pleasant asset.”

15. Improved symptomology

15.1. Therapeutic

Participants reported feeling calm, invigorated, and more relaxed following PST sessions. Some observed that the program was helpful but did not result in complete remission of symptoms: “It [PST] helped me and I think many of us probably to make incremental small changes that helped my current mental health issues or depression or all the issues that I am experiencing. I am not saying for 8 weeks, I am all better. But it has helped and I feel that; I can measure that. That’s what I like best about the group, I can move forward and think about it more and continue those improvements.”

15.2. Reduced anxiety

Participants reported a reduction in feelings of anxiety and increased motivation to engage in daily pleasurable activities, which acted as a diversion therapy for participants.

“I went out to dinner with friends, something I hadn’t done in a long time. It was a challenge to do it and it got me away from thinking of my negative stuff. Once I was into the activity, it was a very pleasant time cause my mind was taken away from all the negative stuff and I got involved in the present moment.”

16. Proposed actions for enhancing PST

16.1. PST as an adjunctive therapy

Participants conveyed that they felt PST was a useful tool that could be used independently once learned. They felt that it may not be a stand-alone treatment but would work well as an add-on to existing treatments.

“It’s [PST] providing a new look at what to do. A kind of pattern or outline when the cars begin to go off the rails. Look this up and try and implement it step-by-step and it might save you a lot of wear and tear, and in my opinion the sudden bursts of temper that I have to always fight. This is good. This has provided a tool or an instrument to deal quickly with it, on your own, that is critical because, let’s face it, right now the medical system is underfunded and understaffed. I think the more people can do on their own to help themselves, the better in the long run.”

16.2. Format of PST sessions

Participants had conflicting views on the components of the program with some wanting more time for sharing and weekly check-ins, while others wanting more time for problem solving. Participants felt it was important to have introductory and closing sessions.

“You need that opportunity to learn what we’re all gonna do here the first day. It takes away the anxiety or it helps with everything that each of us may have felt coming into the room. When we had our first day everything was explained clearly. I think that’s extremely important. To end on a session like that too, saying here’s the things we wanted to accomplish and how did we do at that, rather than compromising the time with a session as well.”

17. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the feasibility of delivering group PST via trained case managers in the treatment of LLD in a real-world setting. This study met most of the feasibility outcome measures. We aimed to enroll 40 participants within 1 year and retain a minimum of 60% (n = 24) participants. Our rate of recruitment was lower (n = 29); however, we achieved a 91% retention rate (n = 26) at 8 weeks. Study recruitment had to be stopped prematurely as funding was not available to run further groups. The results of this study suggest that a future study of PST in a small city like London, Canada with a population of 384,000, may anticipate an enrollment rate of 2.2 participants per month.

In this study, participants acted as their own controls. Participant self-assessed symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia saw statistically significant improvements with self-assessed depression changes demonstrating a large effect size and anxiety and insomnia a small effect size. The large effect size seen in PHQ-9 scores is similar to the effect sizes reported in a recent meta-analysis (Hedges g = 0.66 in older adults age ≥55–75 years and 0.97 in older old adults age 75 years and older; Cuijpers et al., Citation2020). Most participants indicated the program was helpful and that they felt improvements in their mood after completing PST. Participants indicated that receiving PST with peers reduced stigma and provided a sense of safety and support. There were no reported adverse effects.

This study aligns with previous literature findings suggesting that PST has large effect sizes and may be favoured over other forms of therapy such as CBT or reminiscence therapy (Jonsson et al., Citation2016). PST has a theoretical advantage over other psychotherapies as it helps approach practical life problems, such as managing a health problem, or adapting to a nursing home. However, older adults may be unable to access formal therapy providers due to the stigma of attending mental health facilities (Patricia A. Arean et al., Citation2012). Our observed retention rate (91%) suggests the benefits of delivering PST in a community-based, stigma-reduced library setting.

We were able to recruit at a rate of 2.2 participants per month, which suggests the inherent benefits of delivering therapy in groups in that clinicians resources can be utilized more efficiently. In addition, the results of the qualitative analysis support the potential benefits of psychotherapy being delivered in groups. Participants suggested the group format offered peer support, reduced stigma, instilled a sense of hope, developed group cohesiveness, and allowed them to identify universality with the other participants. These findings are therefore consistent with the literature in identifying potential benefits that group therapy may offer over individual psychotherapy (Van Bronswijk et al., Citation2019).

This study found that participants who attended all 8 sessions of PST had a lower baseline anxiety score compared to those who were partial attenders. However, the results indicated that there was a significant decrease in anxiety and insomnia following the course of PST treatment. Therefore, although anxiety symptoms may impact attendance rates for a few reasons (e.g. stigma, fear of judgment), PST still had a medium effect size in reducing anxiety symptoms. This was despite nearly half of the group being partial attendees (attending between 0 and 7 sessions). Encouragement, validation, and support are therefore recommended to reduce any potential reservations that seniors may have in participating in psychotherapy given the potential benefits, especially those who may have anxiety symptoms.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and the lack of a randomized concurrent comparator group. Therefore, this study cannot comment on how PST compares with other psychological treatments or how participants would respond based on medication changes or augmentation strategies. There are other novel psychotherapy modalities such as “Engage” which has been shown to be non-inferior to PST (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2021).

Although drop-out rates in this study were low, an analysis of a pooled multiple imputation dataset to account for missing data provided results inconsistent with the analysis of the original dataset. This indicates that data missing due to dropouts or incompletely collected values could have an impact on the results of the study. However, data from complete attenders (n = 15) versus non-complete attenders (n = 14) showed non-significant differences with small effect size (see Supplement Table S1). Hence, taking into account the small sample size of this pilot behavioural intervention study, there remains a concern of not drawing firm conclusions about program efficacy.

Those who did not attend at week 8 may have dropped out for many reasons and may not have found the intervention helpful. Unfortunately, the views of those participants were not available for the qualitative analysis. Due to limited staffing resources, focus groups were only conducted for PST cohorts 1 and 4. The focus group facilitator was the same staff who administered the study scales which may have introduced a potential bias. Nevertheless, it was felt that saturation was reached for the qualitative analysis as we were able to get qualitative data from 45% of the participants enrolled. We acknowledge that the data may have been more robust if dropped out participants could have also joined the focus groups. Hence, we recommend subsequent larger studies to confirm and validate our findings.

Based on previous findings of efficacy of PST in those with LLD and accompanying executive dysfunction, and/or, dysthymia, as found previously (P. A. Arean et al., Citation2010; Malouff et al., Citation2007), it could be that our results of clinician delivered group PST in the community are also effective in these subgroups and hence need further investigation.

In summary, our study findings suggest that a clinician delivered group-based PST program offered in the community is feasible and was effective in improving symptoms of LLD. These findings need further replication in a definitive randomized controlled trial.

Author contributions

AV and EI assisted with the study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting the paper. MS assisted with the study design and data interpretation. CW and KSPL assisted with data analysis and interpretation. SG helped with the qualitative design, qualitative data analysis, and interpretation. LVB assisted with the staff PST training program and supervision. JS edited the manuscript and assisted with a literature search. PA and DS provided scientific expertise. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.5 KB)Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the Bell Let’s Talk Fund, Canada. We would like to thank all the participants who took part in the study. We also wish to acknowledge the Case Managers and staff from the Geriatric Mental Health Program, London Health Sciences Centre, who provided the Problem-Solving Therapy; Amey Allen, Nancy Bol, Katy D’Angelo, Patrick Fleming, Lisa Joworski, Sarah McGrath-McKinley, and Amir Saeidi. We are immensely indebted and wish to thank our community partner, the London Public Library, London, Canada and their staff including Carolyn Doyle and Megan Paquette.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2022.2107001

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexopoulos, G. S., Raue, P. J., Banerjee, S., Marino, P., Renn, B. N., Solomonov, N., Arean, J. A., Hull, T. D., Kiosses, D. N., Mauer, E., Areán, P. A., & Adeagbo, P. A. (2021). Comparing the streamlined psychotherapy “Engage” with problem-solving therapy in late-life major depression. A randomized clinical trial. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(9), 5180–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0832-3

- Arean, P. A., Raue, P., Mackin, R. S., Kanellopoulos, D., McCulloch, C., & Alexopoulos, G. S. (2010). Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(11), 1391–1398. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091327

- Arean, P. A., Raue, P. J., Sirey, J. A., & Snowden, M. (2012). Implementing evidence-based psychotherapies in settings serving older adults: Challenges and solutions. Psychiatric Services, 63(6), 605–607. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100078 Washington, D.C

- Bobo, W. V., Angleró, G. C., Jenkins, G., Hall-Flavin, D. K., Weinshilboum, R., & Biernacka, J. M. (2016). Validation of the 17-item Hamilton depression rating scale definition of response for adults with major depressive disorder using equipercentile linking to clinical global impression scale ratings: analysis of Pharmacogenomic Research Network Antidepressant Medication Pharmacogenomic Study (PGRN-AMPS) data. Human Psychopharmacology, 31(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2526

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Eckshtain, D., Ng, M. Y., Corteselli, K. A., Noma, H., Quero, S., & Weisz, J. R. (2020). Psychotherapy for depression across different age groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(7), 694–702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0164

- Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Pot, A. M., Park, M., & Reynolds, C. F., 3rd. (2014). Managing depression in older age: Psychological interventions. Maturitas, 79(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.05.027

- Dias, A., Azariah, F., Anderson, S. J., Sequeira, M., Cohen, A., Morse, J. Q., Cuijpers, P., Patel, V., & Reynolds, C. F., 3rd. (2019). Effect of a lay counselor intervention on prevention of major depression in older adults living in low- and middle-income countries: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3048

- Fain, J. A. (2017). Reading, understanding, and applying nursing research. F.A. Davis Company.

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

- Garin, O., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Almansa, J., Nieto, M., Chatterji, S., Vilagut, G., Alonso, J., Cieza, A., Svetskova, O., Burger, H., Racca, V., Francescutti, C., Vieta, E., Kostanjsek, N., Raggi, A., Leonardi, M., & Ferrer, M. (2010). Validation of the “World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, WHODAS-2” in patients with chronic diseases. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-51

- Gustavson, K. A., Alexopoulos, G. S., Niu, G. C., McCulloch, C., Meade, T., & Areán, P. A. (2016). Problem-solving therapy reduces suicidal ideation in depressed older adults with executive dysfunction. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.07.010

- Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 23(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

- Hedges, L. V. (1981). Distribution theory for glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 6(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986006002107

- Huang, A. X., Delucchi, K., Dunn, L. B., & Nelson, J. C. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychotherapy for late-life depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(3), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.003

- Huntley, A. L., Araya, R., & Salisbury, C. (2012). Group psychological therapies for depression in the community: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(3), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092049

- Jonsson, U., Bertilsson, G., Allard, P., Gyllensvard, H., Soderlund, A., Tham, A., Andersson, G., & Branchi, I. (2016). Psychological treatment of depression in people aged 65 years and over: a systematic review of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. PLoS One, 11(8), e0160859. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160859

- Krishna, M., Lepping, P., Jones, S., & Lane, S. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioural psychotherapy treatment for sub-clinical depression. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 16(7–16), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2015.05.043

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., & Schutte, N. S. (2007). The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.005

- McCall, W. V., & Kintziger, K. W. (2013). Late life depression: a global problem with few resources. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 36(4), 475–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2013.07.001

- Miller, M. D., Paradis, C. F., Houck, P. R., Mazumdar, S., Stack, J. A., Rifai, A. H., Mulsant, B., & Reynolds, C. F. (1992). Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: Application of the cumulative illness rating scale. Psychiatry Research, 41(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n

- Mynors-Wallis, L. M., Gath, D. H., Lloyd-Thomas, A. R., & Tomlinson, D. (1995). Randomised controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. Bmj, 310(6977), 441–445. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.310.6977.441

- Nelson, J. C., Delucchi, K., & Schneider, L. S. (2008). Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: a meta-analysis of the evidence. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(7), 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000308883.64832.ed

- Shang, P., Cao, X., You, S., Feng, X., Li, N., & Jia, Y. (2021). Problem-solving therapy for major depressive disorders in older adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(6), 1465–1475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01672-3

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., and Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 20), 22–33;quiz 34–57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9881538/. PMID: 9881538.

- Sheehan, D. V., Sheehan, K. H., Shytle, R. D., Janavs, J., Bannon, Y., Rogers, J. E., Milo, K. M., Stock, S. L., & Wilkinson, B. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(3), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi

- Soldatos, C. R., Dikeos, D. G., & Paparrigopoulos, T. J. (2000). Athens Insomnia Scale: Validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 48(6), 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00095-7

- Tawiah, A. K., Al Sayah, F., Ohinmaa, A., & Johnson, J. A. (2019). Discriminative validity of the EQ-5D-5 L and SF-12 in older adults with arthritis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1129-6

- van Bronswijk, S., Moopen, N., Beijers, L., Ruhe, H. G., & Peeters, F. (2019). Effectiveness of psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine, 49(3), 366–379. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171800199X