Abstract

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic had imposed considerable risk on public health, and had generated unprecedented levels of panic. There are increasing concerns over the possible negative impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of children/adolescents. This review was conducted to describe the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of children and adolescents. An electronic search was conducted in PubMed, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and the WHO Global Health database on COVID-19. The 2020 updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline and an adapted Joanna Briggs aetiology review methodology were followed in conducting this review. A total of 21 studies from 8 different countries located on 4 continents (Asia, Europe, North America & South America), reporting on sample size of 56,368 met the inclusion criteria. Using the JBI critical appraisal tool for studies reporting on prevalence data, the quality of most of the studies was assessed to be moderate. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress was estimated to range from 7.2% to 78%; of anxiety, from 15% to 78%, depression, from 7.2% to 43.7% and stress, at 17.3%. Correlates for COVID −19 related mental health outcomes were identified as female gender and social isolation among others. The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected the mental health of children and adolescents. It is recommended that governments and health agencies prioritize mental health, especially for children and adolescents to prevent long-term effects on them.

1. Background

The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has imposed considerable risk on public health, human safety, and wellbeing and had generated an unprecedented level of panic. COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and having been first detected as a human infection in Wuhan China, in November 2019, the disease had spread across the globe leading to extensive global health burden and socio-economic catastrophe (Gebru et al., Citation2021; Verschuur et al., Citation2021).

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic considering its fast rate of spread within a short period and rate of death. In an attempt by governments to control the spread of the disease, varieties of drastic measures were imposed, including total/partial lockdown, travel ban/border closures, closure of schools, isolation, and quarantine protocols. These measures resulted in restrictions in the movement of people and an abrupt change in everyday lifestyles, separation from friends, loved ones, and families. These sudden changes had the potential to impact negatively on mental health and emotional wellbeing (Phiri et al., Citation2021). Evidence from past outbreaks of SARS epidemics showed that people who recovered develop mental health disorders (Cheng et al., Citation2004; Cheng & Wong, Citation2005; Chua et al., Citation2004) and specifically Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD (Wu et al., Citation2005) and a similar trend is emerging with COVID-19 pandemic (Phiri et al., Citation2021)—but the emphasis has largely been directed at the adult population.

Mental health problems have been widely reported in the general population during this pandemic across countries (Hossain et al., Citation2020; Newby et al., Citation2020; Xiong et al., Citation2020). Most of these reports have focused on adults, including healthcare workers (Batra et al., Citation2020; Muller et al., Citation2020; Newby et al., Citation2020). However children and adolescents deserve a high level of attention because of their vulnerability to mental health problems especially during emergencies and disasters (Danese et al., Citation2020; Paus et al., Citation2008). Apart from that, there is also high tendency to misinterpret mental health problems in children, resulting in low detection, diagnosis and general underreporting. In the wake of COVID −19, the vulnerability of children to mental health problems is heightened by a subtle neglect as children are considered to have a lesser risk of suffering from severe COVID-19 disease and death (Shekerdemian et al., Citation2020). However, they could be hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated measures such as school closures, lack of outdoor activity, and abnormal feeding and sleeping habits which are likely to disturb children’s normal routines, and lead to boredom, discomfort, impatience, irritability, and a variety of neuropsychiatric symptoms and risky behaviours (Ghosh et al., Citation2020; Meherali et al., Citation2021)

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), about half of the world’s students population (862 million children) were affected by the closure of schools (UNESCO, Citation2020) and this would have a negative effect on the mental health of children and adolescents (Ghosh et al., Citation2020; G. G. Wang et al., Citation2020). As an educational intervention during the pandemic, most schools in many countries resorted to online learning to promote continuity in the education system with varying degree of satisfaction among students (Moy & Ng, Citation2021; Thapa et al., Citation2021). The online learning could also be perceived as a source of stress especially to first time users and students in locations with poor internet, logistic access, and inadequate technical support among other factors (Fawaz & Samaha, Citation2021; Hasan & Bao, Citation2020).

An earlier systematic review conducted by Nearchou et al. (Citation2020) in June 2020 concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic may have a negative effect on the mental health of children and adolescents. The study further reported that emotional reactions to COVID −19 such as stress, fear, worry and concern predicted mental health outcomes in young people. However, the findings had little or no focus on children. Some of the studies included in the review focused greatly on adult population. Some of the studies included were also appraised to be of low quality. The reviewers, therefore, recommended the need for researchers to improve the quality of future studies to generate more robust evidence to guide policy and intervention.

1.1. Aim of the review

The main aim of this review was to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents and to identify the risk or protective factors for mental health in children and adolescents.

1.2. Objectives of the review

The specific objectives of this review include:

Describe the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic

Identify risk factors for mental health impact on children and adolescents during COVID-19

Determine the protective factors for mental health impact on children and adolescents during COVID-19

1.3. Review question

The main systematic review question which was asked to guide the review methodology was: “Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact negatively on the mental health of children and adolescents?”

2. Materials and methods

This review aimed to synthesize relevant primary studies to describe the effect of COVID-19 pandemic/lockdown measures on the mental health of children and adolescents by using a systematic review methodology.

2.1. Formulating the review question

Formulating a concise review question for the appropriate type of review to be conducted is a critical step for a successful systematic review. There are several formats available for framing review questions. For instance, the PICO (population, intervention comparison, and outcome) format is widely used for effectiveness reviews (Booth & Cleyle, Citation2006; Fineout-Overholt & Johnston, Citation2005; Munn et al., Citation2018). This review aimed at describing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic or lockdown measure on the mental health of children and adolescents. To frame the question for this review, the PEO format (Moola et al., Citation2015) was identified as appropriate and was used. The PEO format is used for aetiology and/risk reviews (Moola et al., Citation2015). Since the type of research question guides selection of methodology, the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for conducting aetiology review was adapted and used for this review (Moola et al., Citation2015) while the 2020 updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Page et al., Citation2021) was adapted for reporting. The PEO format stands for population (type of participant), exposure (independent variable) and outcome (dependent variable). The main facets of the question are summarized in Table .

Table 1. Review question in PEO format

An initial scoping search was conducted in Google Scholar and Cochrane Library using the main terms of the topic in Table . This was done to ascertain whether there is an existing systematic review that has addressed the review question adequately to avoid unintentional duplication. Another reason for carrying out an initial scoping search of the selected databases was to gain a fair idea of the range or depth of existing literature available.

In order to build a comprehensive search strategy for the database, facet analysis was carried out to identify synonyms for each of the main terms in the question—see, in Table . The following terms were identified under the population component: children, adolescents, teenagers. For the exposure component, the following terms were identified: COVID-19, COVID19, lockdown, quarantine, isolation, lock-down, and sars-cov-2. The terms under the outcome component included: mental health, stress, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicide, depression, and anxiety. All these terms were used to construct a comprehensive search strategy to be used for database search—see, Table .

Table 2. Search strategy using Boolean Operators (OR & AND)

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included in the review only if they met the following criteria: if the study is COVID-19 related, conducted on humans and, published in English between 1 December 2020 and 10 June 2021. Also, the outcome measure must have been recorded quantitatively and in a binary data format (n/N) or in the percentage of the proportion of participants who experienced an event, where applicable. The outcome measure must be a mental health-related outcome and for this review, the primary outcomes of interest were depression, anxiety, and stress. The secondary outcome includes post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicidal behaviour and risk/mitigating factors for mental health impact due to COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the study must be conducted on children or adolescents or both with ages not more than 18 years. Studies were not included if they were not published in English, were qualitative studies, animal studies, not COVID-19 related or if participants were older than 18 years—see, Table .

Table 3. Inclusion & exclusion criteria

2.3. The electronic database search

Four major databases were selected for the electronic search. These databases included: PubMed, CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE with full text, and the World Health Organization (WHO) COVID-19 Global literature on coronavirus disease. The WHO Global literature on coronavirus disease is a database dedicated to global COVID-19 research. The three reviewers (SSO, MA & AOY) conducted the final electronic search independently in the selected databases on 10 June 2021 using the search strategy designed.

2.4. Conducting the electronic search

To retrieve as many relevant published articles and to minimize selection bias, the main terms were searched as Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) Term and as a free text or under “All Fields”. If the synonym of the main term is also a MeSH term, then it is also searched under MeSH and also under “All Fields”. During the database search, the main term and its synonyms were combined using the Boolean operator “OR”. The Boolean operator “AND” was used to combine the searches across the PEO components—see, Table details of the search strategy using the Boolean operators.

The PubMed platform was searched using this search strategy as follows: (covid-19 OR covid 19 OR sars-cov-2 OR quarantine OR lockdown OR lock-down) AND (mental health OR depression OR anxiety OR stress OR suicide OR posttraumatic stress disorder OR post-traumatic stress disorder) AND (children OR teenager OR adolescents). The following filters applied to the search result: English Language, Journal articles, publications from 1 December 2020, to 10 June 2021, Human studies, and Child: birth to 18 years. On the WHO platform, items were specifically searched under Main Subject and under “Title, abstract and subject”. The search was limited to articles published in the English language.

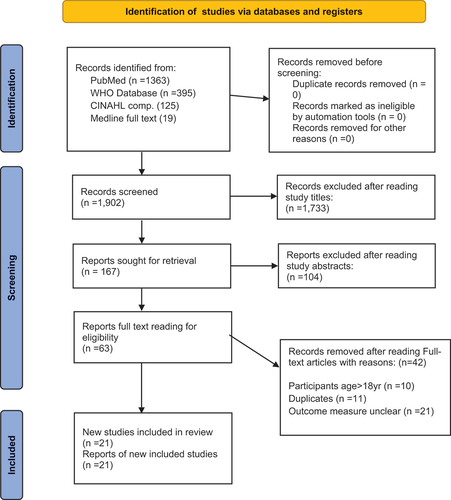

Disagreements arising at the third stage were discussed thoroughly and an agreement was reached before a decision was taken to either include the article or not. No study author was contacted for clarification on data and therefore, any article that did not have adequate information for example, on the age of participants or an unclear outcome measure were excluded from the review. All studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected for inclusion and data extraction. The selection process through which articles were selected has been summarized in Figure using the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (The PRISMA 2020 statement) flow chart (Page et al., Citation2021).

2.5. Selection of studies

The three reviewers manually scrutinized all the records independently and selected studies that met the inclusion criteria for final inclusion in the review. The reviewers (SSO, MA & AOY) first read the titles of each article and made a selection based on a judgment of relevance. The second stage of selection involved reading the abstracts of all the studies selected at the first stage. The final stage of selection was based on reading the full text of all articles selected at the second stage. This stage was carefully done to remove duplicates.s

2.6. Data extraction from included studies

Data from each primary study included in the review were extracted using a data extraction format designed by the reviewers. All 3 reviewers (SSO, MA & AOY) extracted data on the author and year of publication, the country where the study was conducted, participants, the age range of participants, and sample size (Table ).

Table 4. Excluded papers and reasons for exclusion

Another data set extracted from the studies was data on the primary outcome (in the form; number of participants who experienced an outcome of interest divided by sample size, n/N). The primary outcomes of interest for the review are Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and suicide ideation. Data was also collected on protective factors for mental health as well as risk factors.

2.7. Quality appraisal

The JBI critical appraisal tool for studies reporting on prevalence data was used to appraise the 21 studies which met the inclusion criteria for the study since all the studies provided prevalence data on mental health outcomes. The appraisal specifically focused on nine areas; the sampling frame and sampling technique, adequacy of sample size, description of study setting and subjects, coverage of identified sample, valid methods used to identify mental health indicators, standard tools used for measurements of mental health indicators, statistical analysis and adequacy of response rate (Munn et al., Citation2015). The total number of “yes” for items that are applicable to each study were averaged to determine if the study was of low, moderate or high quality.

3. Results/Findings

A total of 21 articles (33.3%) were deemed to have met the inclusion criteria and were finally selected for inclusion in the review. Table contains a summary information on the 42 studies excluded and the reasons for exclusion. A general overview of the 21 articles selected is provided in Table . The 21 studies are from 8 different countries located in 4 continents (Asia, Europe, North America & South America. Most of the studies were conducted in China which had 13 articles in total, followed by Italy which had 2 search papers. The rest of the countries are the Netherlands, Brazil, Turkey, United States of America (USA), India, and Spain—all of which had 1 research article each. All the 21 studies have recruited a total of 56,368 participants (children and adolescents) below 18 years. All these children and adolescents have experienced the COVID-19 pandemic, or, lockdown measures or isolation or school closure, and had to stay home over a while. The findings relating to the various outcome measures are summarized in and discussed below.

Table 5. Characteristics of studies included in the review

Table 6. Data extracted from the studies on outcome measures

3.1. Prevalence of depressive symptoms

There were sixteen (16) studies reported data on the prevalence of depression. From the extracted data, the prevalence of depression symptoms ranges from 7.2% to 43.7%. The total number of participants from the 16 studies is 50,196 children and adolescents. Data extracted from these studies suggest that COVID-19 pandemic had a substantial impact on the mental health of the children and adolescents at the various places of study. Out of the 50,196 participants (children and adolescents), 14,139 participants experienced depressive symptoms, which represents a pooled prevalence estimate of 28.2%. Thus, almost a third of the participants had depression.

3.2. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms

Data on the proportion of participants who experienced anxiety was measured in 17 studies which include. The sample size in all these studies put together amounts to 36,396 and out of which 10,048 (27.6%) reported symptoms of anxiety. Thus, approximately one-third of these participants reported experiencing anxiety. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms ranges from 15% to 78%.

3.3. Stress in children and adolescents

Only two of the studies (Tang et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2020) had presented measurements on stress among the study participants. The total sample size for the two studies is 5,367 and out of this sample, 930 representing 17.3% reported stress.

3.4. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

In all, there were three studies (Ma et al., Citation2021; Shek et al., Citation2021; C. Zhang et al., Citation2020) that provided data on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) with a combined sample size of 6,674 out of which 877 participants experienced PTSD, representing 13.1%.

3.5. Prevalence of suicide attempt, ideation, or plan

Information on suicide was provided in only one of the studies (Zhang et al., Citation2020) which involved a sample size of 1,241 participants, out of which 50.7% (629) had engaged in various suicidal behaviours such as suicidal ideation: 29.7% (369/1241); suicidal plan: 14.6% (181/1241); and suicidal attempts: 6.4% (79/1241).

3.6. Risk and Protective factors of mental health problems

The prevailing risk factors for poor mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, stress, PTSD, and suicide) related to COVID-19 were identified by 19 of the studies. Two studies did not report any significant risk factors (L. Zhang et al., Citation2020; Segre et al., Citation2021). Female gender was identified to be associated with high levels of COVID −19 related mental health outcomes by seven (7) studies with a total sample size of 22,587. Adolescence (older adolescent) was identified by 5 studies, 4 from China and 1 from Spain (Pizarro-Ruiz & Ordóñez-Camblor, Citation2021) while social isolation was also reported in various forms in 5 studies. The forms included staying without parents, (Garcia de Avila et al., Citation2020b), staying without companion on weekdays (F. F. Chen et al., Citation2020a), adolescents going through strict quarantine for 8–10 hours (Pizarro-Ruiz & Ordóñez-Camblor, Citation2021), long term home restrictions with less face-to-face communications and less pleasure. Other risk factors included residing in boarding house, living in areas of high infections (Xie et al., Citation2020; J. Zhou et al., Citation2020), fear of contracting COVID- 19, (Abawi et al., Citation2020; Xie et al., Citation2020), family member infected with COVID −19, identified in 2 studies from China and Turkey (S. Chen et al., Citation2020; Kılınçel et al., Citation2021) and exposure to TV news or information about COVID-19 identified in 2 studies, (Kılınçel et al., Citation2021; Li et al., 2021).

Moreover, family loss of income, rural dwelling or home location, and poor socioeconomic status were identified in 4 studies, while previous psychopathology was identified by 2 studies in Spain and Italy (Kılınçel et al., Citation2021; Pisano et al., Citation2021). Parental educational level or qualification (S. Chen et al., Citation2020; SaSama et al., Citation2021), poor parent-child relationship (J. Wang et al., Citation2021), poor sleep (Li et al., 2021; J. Zhou et al., Citation2020), insufficiency of food and perceived discrimination (Li et al., Citation2021b), Smart phone use and internet addiction (Duan et al., Citation2020) were also identifiesd as correlates. However, there was conflicting reports on school level as a correlate for covid 19—related mental health outcomes. While lower grade level students had high prevalence of anxiety and depression in Wuhan—China (S. Chen et al., Citation2020), and anxiety and OCD-related behaviours in USA (McKune et al., 2021), on the contrary, high school students had higher prevalence of anxiety and stress than junior school students in C. X. Zhang et al.’s (Citation2020) study in Guangdong—China. Factors such as PositiveYouth development PYD (Shek et al. (Citation2021), positive coping and resilience (C. Zhang et al., Citation2020), optimism (Xie et al., Citation2020), and exercise/physical activity (F. S. Chen et al., Citation2020; Li et al., 2021) were identified as protective or mitigating against COVID-19 related mental health outcomes.

4. Discussion

A systematic review conducted during the early days of the pandemic suggests that the pandemic was affecting children and adolescents’ mental health (Nearchou et al., Citation2020b). However, there were not many robust primary studies at the time of that study. This review was conducted to synthesize and describe the mental health impact of COVID-19 on children and adolescents from primary studies. The primary outcome measures of interest included the anxiety, depression, and stress. Secondary outcomes were Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and suicidal behaviour. The review further examined the mitigating factors as well as risk factors of COVID-19 and mental health of children and adolescents. The overall evidence gathered points to the fact that COVID-19 has negatively affected the mental health of a sizeable proportion of children and adolescents.

5. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety and stress

In this review, the prevalence rates of depression, anxiety, and stress from the individual studies ranged from 7.2% to 43.7%, 15% to 78%, and 15.2% to 26.1% respectively. In an earlier review, it was found that the range of prevalence of depression was from 22.6% to 43.7% and that of anxiety from 18.9% to 37.4% (Nearchou et al., Citation2020b). Similarly, a meta-analysis reported the pooled prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among college students as 31.2%, 39.4%, and 26.0% respectively (Batra et al., Citation2021). Comparatively, the levels of depression and anxiety have marginally reduced, and this could be due to the time difference that has allowed for better adjustment to the COVID-19 situation, although the studies included in the previous study were rated as low to moderate in methodological quality.

The current review investigated the risk and mitigating factors for the prevalence of the mental health outcomes of interest. These correlates have been classified into personal/individual factors (such as age, school grade, gender, and being in a boarding house, previous psychopathology), family factors (such as income, educational status of parent, employment, parent-child interaction, infected family member), community factors (such as rural dwelling, high infection area, access to friends), and media (smart phone use, internet browsing, extensive exposure to television news on COVID-19).

Age and gender are significant individual determinants of mental health generally. In the present review, about six (6) studies reported that the adolescent cohort experienced a higher risk of depression and anxiety compared to younger children. This finding agrees with Paus et al., that adolescents are vulnerable to mental disorders, especially depression (Paus et al., Citation2008b). This is because adolescence is a critical time for acquiring and sustaining important emotional and social habits for mental health. Therefore, the sudden and drastic changes in social life patterns as a result of the school closures and other restrictions associated with the pandemic may have been overwhelming for adolescents to adjust to or cope with (Gazmararian et al., Citation2021), resulting in the signs and symptoms of depression experienced by many. This current review also reported that older adolescents, adolescents in high school or higher school grades were particularly at higher risk of depression, anxiety, and stress. Similarly, student status was associated with greater levels of depression symptoms and PTSD symptoms, according to a systematic review (Xiong et al., Citation2020). On the contrary, two studies reported lower school and grade level as risk factors for depression and anxiety (S. F. Chen et al., Citation2020a; McKune, Acosta, Diaz, Brittain, Joyce-Beaulieu, et al., Citation2021). This may be because young children and adolescents do not fully understand the disease and therefore are less worried.

Also, female adolescents had a significantly higher risk of developing depression and anxiety compared to their male counterparts, according to data obtained from ten (10) studies. This finding is supported by a cross-country study and a meta-analysis which report that due to the intricacies of gender differences, females generally experience worse mental health than boys, with varying directions and degrees of the gender gap (Batra et al., Citation2021; Campbell et al., Citation2021). The implication of this piece of evidence concerning age and gender is that mental health interventions should pay special attention to the emotional and psychological wellbeing of adolescents, especially female adolescents, so they can be protected from developing psychological symptoms.

Notwithstanding, children and adolescents who had previous psychopathology or past psychiatric referral were at higher risk of depression and anxiety during the pandemic, as reported by two studies (Kılınçel et al., Citation2021; Pisano et al., Citation2021) in this review. This can be attributed to an exacerbation of symptoms (Lin et al., Citation2021) as a result of reduced access to health care services due to lockdowns and fear of contracting the COVID-19 virus. On the contrary, Bobo et al.’s (Citation2020) primary survey in France using both closed and open-ended questions found that for children and adolescents with ADHA there was more psychological stability or better wellness, reduction in school-related anxiety, adaptable modifications to the children’s routines, and higher self-esteem. Also, parents’ awareness of the importance of inattention and ADHD symptoms in their children’s learning challenges appears to have increased as a result of the lockdown situation (Bobo et al., Citation2020). This means that the impact of COVID-19 and its associated lockdown could have both positive and negative effects on the mental health outcomes of children and adolescents.

Furthermore, family-related factors such as loss of household income and the educational level of the mother are another risk factor for children and adolescents to develop depression and anxiety, according to the data (McKune et al., 2021; SaSama et al., Citation2021). As primary caregivers, educational status of mothers can have significant influence on the care given to children especially during the pandemic. Other risk factors that have been extracted from the studies and which appear to be linked to loss of household income include insufficient food and the poor parent-child relationship (Li et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has led to numerous job losses, and this may have resulted in economic hardships and the inability of such parents to provide basic needs for their families. Therefore, insufficient food has been detected as a risk factor for chronic mental health problems among children (Li et al., Citation2021a; Paslakis et al., Citation2021). Also, a parent who has lost his/her livelihood through the pandemic may be unable to maintain a healthy mindset, or psychological wellbeing (Griffiths et al., Citation2021; Posel et al., Citation2021) and that could impact negatively on the parent-child relationship, and this will expose the child to the risk of mental illhealth as observed in the primary studies. This is because poor parent-child relationships do not promote open communication. Additionally, because of school closures and restrictions on movement, many children spend several hours at home alone while their parents are working, especially on weekdays (F. S. Chen et al., Citation2020b). These culminate in boredom leading to depression and anxiety.

The review also discovered that a higher risk of depression and anxiety were significantly associated with having a family member who is infected with COVID-19 (Kılınçel et al., Citation2021), and fear of contracting COVID-19 (Abawi et al., Citation2020; Shek et al., Citation2021). Thus, depression, anxiety, and stress were prevalent in children who were living in fear of contracting COVID-19. This finding is also supported by another review (Xiong et al., Citation2020). As members of the family children are equally concerned about all members of the family and therefore it is expected for them to be worried. Apart from that, the children maybe aware that due to their close contact they will be required to undergo screening and quarantine for days which may separate them from their loved ones leading to fear.

In addition to the personal and family-related factors, community-related factors were also identified to influence the risk of depression and anxiety among children and adolescents during the pandemic. Notable among them is living in a rural dwelling or living in an area with an increased number of infections known as hotspots, as reported by four (4) studies (SaSama et al., Citation2021a; Xie et al., Citation2020a; J. Zhou et al., Citation2020a; S.-J. Zhou et al., Citation2020b). Rural settlements are usually characterized by unfavourable disparities in vital resources which may be necessary for proper adjustment and coping with the pandemic. For example, most schools switched to online learning during the periods of school closure. This required access to a computer and the internet, which may be lacking in rural areas. Children and adolescents within these areas are left behind in such online learning experiences, which can have dire psychological effects such as feelings of being discriminated against, self pity, and anger. Similarly, anxiety and depression were found to be lower in metropolitan areas and higher in rural areas and higher psychological symptoms were recorded among children in highly infectious areas (Marques de Miranda et al., Citation2020).

Our review also revealed that face-to-face communication with friends was limited as were opportunities to engage in hobbies and other physical activities as a result of home restrictions and strict quarantine, and this also presented increased risk factors for depression and anxiety (F. S. Chen et al., Citation2020; Li et al., 2021). Adolescents generally prefer to associate with their peers even more than family as they get to socialise and engage in extracurricular activities which help in their total upbringing. Also, regular physical activity and exercise have been identified in this review as protective or mitigating factors against depression and anxiety during the pandemics and this is supported by Maugeri et al. (Citation2020). Therefore, parents, teachers, religious and community youth organisation should device innovative strategies or programmes that offer young people opportunity to communicate, share ideas, learn and engage with their peers.

In this review, media-related concerns such as extended smart phone use, internet addiction, browsing about COVID-19 information and frequent exposure to television news on the COVID-19 also posed a risks for depression, anxiety, and stress among children and adolescents. Therefore, parents and guardians/caregivers need to take active steps against excessive exposure of children to television news on the happenings of COVID-19 pandemic. While television is a great source of information, some information may not be appropriate for the consumption of children and adolescents. Contrary to this finding, Gazmararian et al. (Citation2021) reported that about 51% of adolescents in Georgia used social media to help them cope with the anxiety, fear and stress of the pandemic. Prior to the lockdowns, children and adolescents used internet mostly for entertainment on social media but had to re-direct the use of the internet to online learning. This was met with some challenges that contributed to stress and anxiety among children and adolescent. While the transition to remote online learning as a result of the COVID-19 may yield positive perceptions from students, there are some problem areas that need attention to maximize the benefit for students on different curricula (Kaurani et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, evidence suggest that e-learning perceptions influence student’s psychological distress (Hasan & Bao, Citation2020). However, Moy and Ng (Citation2021) studied university students in Malaysia and did not find perception towards e-learning to be associated with stress, anxiety, or depression.

This review also identified some factors that mitigate or are protective against depression and these include: regular physical exercise/activity, being optimistic, positive coping, and resilience. However, physical activity is observed to be greatly reduced during lockdowns and online learning (Chu & Li, Citation2022; Maugeri et al., Citation2020).

6. Prevalence and correlates post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicidal behaviours

The overall prevalence rate of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the review was 13.1%. from three (3) studies (C. Zhang et al., Citation2020; Ma et al., Citation2021; Shek et al., Citation2021). Similarly, Batra et al. (Citation2021) reported a total prevalence of 29.8% for PTSD among college students in a meta-analysis. With regards to risk factors, adolescents had a higher risk of developing PTSD than young children. Also, the fear of contracting COVID-19 infection and being in boarding houses were the other risk factors for PTSD. Boarding houses may be likened to institutionalised care which has been identified to negatively affect the psychological, emotional and social development of children and adolescents (Desmond et al., Citation2020). Hence, in the event of a pandemic, the preferred place the child may be the home, with all their loved ones present, which creates a sense of security even in adversity. On the other hand, positive youth development (PYD) was found to be the mitigating factor against the development of PTSD. PYD programmes offer opportunities for young people to learn about, respect, and explore diversity, as well as to build the interpersonal skills necessary to traverse differences in a productive and civil manner (Arnold, Citation2020). Such programmes should be initiated and promoted across countries to empower the youth to overcome the negative effects of the pandemic.

Also, data on suicidal behaviour was obtained from only one of the studies (Zhang et al., Citation2020), which reported a 50.7% prevalence of suicidal behaviour in various forms. Presence of suicidal ideas, suicidal plan, and suicidal attempts were 29.7%, 14.6%, and 6.4% respectively. This is a longitudinal study that had data on the participants on suicide recorded before the pandemic and during the pandemic, the researchers followed up on the participants to collect the second data. And, the data gathered suggest a significant increase in suicidal behaviours during the pandemic compared to data before the pandemic. A higher prevalence of suicidal ideations were also recently reported in a meta-analysis by Batra et al. (Citation2021). This suggests that COVID-19 had a huge negative impact on the mental health of children and adolescents in terms of suicide requiring active measures to restore and improve their mental health status. However, more research studies are needed to get more robust evidence.

7. Strengths and weaknesses of this review

One of the strengths of this review is that it contains data from many studies, compared to earlier reviews. Also, the methodological quality of the studies included in this review is generally of moderate quality. The majority of the studies recruited adequate sample sizes and collected data using standardized measuring instruments. Also, three reviewers scrutinized and worked in collaboration to select papers for inclusion and on data extraction to avoid selection or data extraction biases. Furthermore, the reviewers followed strictly, the predetermined inclusion criteria and selected only articles that met the inclusion criteria.

Regardless, this review has weaknesses and so the results should be interpreted with these limitations in mind. Firstly, the reviewers selected and searched only 4 databases. And, even though these four databases are major databases, it is possible that other databases not searched could contain other relevant articles. In addition, only articles published in English were included. All these are considered limitations as they threaten the completeness of evidence included in this review against what may actually exist.

8. Recommendations and conclusion

In summary, the evidence gathered showed that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted negatively the mental health of children and adolescents. On primary outcomes, the prevalence of depression was 28.2% and ranges from 7.2% to 43.7%. The prevalence of anxiety was 27.1% and ranges from 15% to 78%. On stress, the prevalence was 17.1% and it ranges from 15.2% to 26.1%. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was prevalent in 13.1% of the participants while suicidal behaviour was recorded in 50.7%. It was also revealed that adolescents had more of the psychological impact compared to children and female adolescents were at higher risk of experiencing anxiety, depression, and stress.

The findings generated in this review point to the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted negatively the mental health of children and adolescents. It is therefore recommended that a special mental health interventions be designed to pay attention to adolescents especially females to protect their psychological and emotional wellbeing. Majority of the studies accessed were cross-sectional studies. And, it is not yet known how these mental health experiences of the children and the adolescents are going to affect them in the future. In this regard, it is recommended that future research should consider undertaking longitudinal designs that will follow the participants for an extended period to determine if there will be residual effects in their adulthood. Policy-wise, government and state agencies responsible for mental health policy should consider prioritizing mental health for children and adolescents with specific attention directed at mitigating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is also worth noting that among all the studies that were included in the review, none came from the African continent. It is recommended that African researchers take this task up and generate context-specific evidence to guide mental health care, especially in children and adolescents.

Data availability statement

This review manuscript report on previously published data. The individual articles forming the basis of the manuscript are included therein. Readers can search for the articles online or request for the articles by writing to the corresponding author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abawi, O., Welling, M. S., Eynde van den, E., van Rossum, E. F. C., Halberstadt, J., van den Akker, E. L. T., & van der Voorn, B. (2020). COVID-19 related anxiety in children and adolescents with severe obesity: A mixed-methods study. Clinical Obesity, 10(6), e12412. https://doi.org/10.1111/cob.12412

- Ademhan Tural, D., Emiralioglu, N., Tural Hesapcioglu, S., Karahan, S., Ozsezen, B., Sunman, B., Nayir Buyuksahin, H., Yalcin, E., Dogru, D., Ozcelik, U., & Kiper, N. (2020a). Psychiatric and general health effects of COVID‐19 pandemic on children with chronic lung disease and parents’ coping styles. Pediatric Pulmonology, 55(12), 3579–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25082

- Arnold, M. E. (2020). America’s moment: Investing in positive youth development to transform youth and society. Journal of Youth Development, 15(5), 16–36. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2020.996

- Batra, K., Sharma, M., Batra, R., Singh, T. P., & Schvaneveldt, N. (2021). Assessing the psychological impact of COVID-19 among college students: An evidence of 15 countries. Healthcare (Basel Switzerland), 9(2), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020222

- Batra, K., Singh, T. P., Sharma, M., Batra, R., & Schvaneveldt, N. (2020). Investigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 9096. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239096

- Bobo, E., Lin, L., Acquaviva, E., Caci, H., Franc, N., Gamon, L., Picot, M.-C., Pupier, F., Speranza, M., Falissard, B., & Purper-Ouakil, D. (2020). How do children and adolescents with Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) experience lockdown during the COVID-19 outbreak? Encephale, 46(3), S85–S92.

- Booth, A., & Cleyle, S. (2006). Clear and present questions: Formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech, 24(3), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830610692127

- Campbell, O. L. K., Bann, D., & Patalay, P. (2021). The gender gap in adolescent mental health: A cross-national investigation of 566,829 adolescents across 73 countries. SSM - Population Health, 13, 100742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100742

- Chen, S., Cheng, Z., & Wu, J. (2020). Risk factors for adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison between Wuhan and other urban areas in China. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00627-7

- Cheng, S. K.-W., Tsang, J. S.-K., Ku, K.-H., Wong, C.-W., & Ng, Y.-K. (2004). Psychiatric complications in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) during the acute treatment phase: A series of 10 cases. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184(4), 359–360. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.184.4.359

- Cheng, S. K. W., & Wong, C. W. (2005). Psychological intervention with sufferers from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): Lessons learnt from empirical findings. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 12(1), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.429

- Chen, X., Qi, H., Liu, R., Feng, Y., Li, W., Xiang, M., Cheung, T., Jackson, T., Wang, G., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2021). Depression, anxiety and associated factors among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: A comparison of two cross-sectional studies. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01271-4

- Chen, F., Zheng, D., Liu, J., Gong, Y., Guan, Z., & Lou, D. (2020a). Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 36–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061

- Chua, S. E., Cheung, V., McAlonan, G. M., Cheung, C., Wong, J. W., Cheung, E. P., Chan, M. T., Wong, T. K., Choy, K. M., Chu, C. M., Lee, P. W., & Tsang, K. W. (2004). Stress and psychological impact on SARS patients during the outbreak. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(6), 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370404900607

- Chu, Y.-H., & Li, Y.-C. (2022). The impact of online learning on physical and mental health in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052966

- Cusinato, M., Iannattone, S., Spoto, A., Poli, M., Moretti, C., Gatta, M., & Miscioscia, M. (2020). Stress, resilience, and well-being in Italian children and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228297

- Danese, A., Smith, P., Chitsabesan, P., & Dubicka, B. (2020). Child and adolescent mental health amidst emergencies and disasters. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(3), 159–162. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.244

- Desmond, C., Watt, K., Saha, A., Huang, J., & Lu, C. (2020). Prevalence and number of children living in institutional care: Global, regional, and country estimates. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(5), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30022-5

- Di Riso, D., Bertini, S., Spaggiari, S., Olivieri, F., Zaffani, S., Comerlati, L., Marigliano, M., Piona, C., & Maffeis, C. (2021). Short-term effects of COVID-19 lockdown in Italian children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: The role of separation anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5549. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115549

- Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

- Durcan, G., Barut, K., Haslak, F., Doktur, H., Yildiz, M., Adrovic, A., Sahin, S., & Kasapcopur, O. (2021). Psychosocial and clinical effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in patients with childhood rheumatic diseases and their parents. Rheumatology International, 41(3), 575–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04790-x

- Dyer, J., Wilson, K., Badia, J., Agot, K., Neary, J., Njuguna, I., Kibugi, J., Healy, E., Beima-Sofie, K., John-Stewart, G., & Kohler, P. (2021). The psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth living with HIV in Western Kenya. AIDS and Behavior, 25(1), 68–72.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03005-x

- Ezpeleta, L., Navarro, J. B., de la Osa, N., Trepat, E., & Penelo, E. (2020). Life conditions during COVID-19 lockdown and mental health in Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197327

- Fawaz, M., & Samaha, A. (2021). E‐learning: Depression, anxiety, and stress symptomatology among Lebanese university students during COVID‐19 quarantine. Nursing Forum, 56(1), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12521

- Fineout-Overholt, E., & Johnston, L. (2005). Teaching EBP: Asking searchable, answerable clinical questions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 2(3), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2005.00032.x

- Garcia de Avila, M., Hamamoto Filho, P., Jacob, F., Alcantara, L., Berghammer, M., Jenholt Nolbris, M., Olaya-Contreras, P., & Nilsson, S. (2020a). Children’s anxiety and factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory study using the children’s anxiety questionnaire and the numerical rating scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165757

- Garcia de Avila, M., Hamamoto Filho, P., Jacob, F., Alcantara, L., Berghammer, M., Jenholt Nolbris, M., Olaya-Contreras, P., & Nilsson, S. (2020b). Children’s anxiety and factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory study using the children’s anxiety questionnaire and the numerical rating scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165757

- Gazmararian, J., Weingart, R., Campbell, K., Cronin, T., & Ashta, J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of students from 2 semi-rural high schools in Georgia*. Journal of School Health, 91(5), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.13007

- Gebru, A. A., Birhanu, T., Wendimu, E., Ayalew, A. F., Mulat, S., Abasimel, H. Z., Kazemi, A., Tadesse, B. A., Gebru, B. A., Deriba, B. S., Zeleke, N. S., Girma, A. G., Munkhbat, B., Yusuf, Q. K., Luke, A. O., & Hailu, D. (2021). Global burden of COVID-19: Situational analysis and review. Human Antibodies, 29(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.3233/HAB-200420

- Ghosh, R., Dubey, M. J., Chatterjee, S., & Dubey, S. (2020). Impact of COVID −19 on children: Special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatrica, 72(3). https://doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05887-9

- Griffiths, D., Sheehan, L., van Vreden, C., Petrie, D., Grant, G., Whiteford, P., Sim, M. R., & Collie, A. (2021). The impact of work loss on mental and physical health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Baseline findings from a prospective cohort study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 31(3), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-021-09958-7

- Hasan, N., & Bao, Y. (2020). Impact of “e-Learning crack-up” perception on psychological distress among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A mediating role of “fear of academic year loss”. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105355. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105355

- Hawke, L. D., Barbic, S. P., Voineskos, A., Szatmari, P., Cleverley, K., Hayes, E., Relihan, J., Daley, M., Courtney, D., Cheung, A., Darnay, K., & Henderson, J. L. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on Youth Mental Health, Substance Use, and Well-being: A Rapid Survey of Clinical and Community Samples: Répercussions de la COVID-19 sur la santé mentale, l’utilisation de substances et le bien-être des adolescents : Un sondage rapide d’échantillons cliniques et communautaires. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65(10), 701–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720940562

- Hermosillo-de-la-torre, A. E., Arteaga-de-luna, S. M., Acevedo-Rojas, D. L., Juárez-Loya, A., Jiménez-Tapia, J. A., Pedroza-Cabrera, F. J., González-Forteza, C., Cano, M., & Wagner, F. A. (2021). Psychosocial Correlates of suicidal behavior among adolescents under confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic in aguascalientes, Mexico: A cross-sectional population survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094977

- Hossain, M. M., Tasnim, S., Sultana, A., Faizah, F., Mazumder, H., Zou, L., McKyer, E. L. J., Ahmed, H. U., & Ma, P. (2020). Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. F1000Research, 9, 636. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.24457.1

- Jackson, S. B., Stevenson, K. T., Larson, L. R., Peterson, M. N., & Seekamp, E. (2021). Outdoor activity participation improves adolescents’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052506

- Kang, S., Sun, Y., Zhang, X., Sun, F., Wang, B., & Zhu, W. (2020). Is physical activity associated with mental health among Chinese adolescents during isolation in COVID-19 pandemic? Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 11(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.200908.001

- Kaurani, P., Batra, K., Rathore Hooja, H., Banerjee, R., Jayasinghe, R. M., Leuke Bandara, D., Agrawal, N., & Singh, V. (2021). Perceptions of dental undergraduates towards online education during COVID-19: Assessment from India, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 12, 1199–1210. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S328097

- Khan, A. H., Sultana, M. S., Hossain, S., Hasan, M. T., Ahmed, H. U., & Sikder, M. T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health & wellbeing among home-quarantined Bangladeshi students: A cross-sectional pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.135

- Kılınçel, Ş., Kılınçel, O., Muratdağı, G., Aydın, A., & Usta, M. B. (2021). Factors affecting the anxiety levels of adolescents in home‐quarantine during COVID ‐19 pandemic in Turkey. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 13(2), e12406. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12406

- Lin, P.-I., Srivastava, G., Beckman, L., Kim, Y., Hallerbäck, M., Barzman, D., Sorter, M., & Eapen, V. (2021). A framework-based approach to assessing mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 655481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.655481

- Liu, R., Chen, X., Qi, H., Feng, Y., Xiao, L., Yuan, X.-F., Li, Y.-Q., Huang, -H.-H., Pao, C., Zheng, Y., & Wang, G. (2021). The proportion and associated factors of anxiety in Chinese adolescents with depression during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Affective Disorders, 284, 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.020

- Li, W., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Ozaki, A., Wang, Q., Chen, Y., & Jiang, Q. (2021a). Association of home quarantine and mental health among teenagers in Wuhan, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(3), 313. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5499

- Li, W., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Ozaki, A., Wang, Q., Chen, Y., & Jiang, Q. (2021b). Association of home quarantine and mental health among teenagers in Wuhan, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(3), 313. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5499

- Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y. A., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

- Ma, Z., Idris, S., Zhang, Y., Zewen, L., Wali, A., Ji, Y., Pan, Q., & Baloch, Z. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic outbreak on education and mental health of Chinese children aged 7–15 years: An online survey. BMC Pediatrics, 21(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02550-1

- Marques de Miranda, D., da Silva Athanasio, B., Sena Oliveira, A. C., & Simoes-e-Silva, A. C. (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845

- Maugeri, G., Castrogiovanni, P., Battaglia, G., Pippi, R., D’Agata, V., Palma, A., Di Rosa, M., & Musumeci, G. (2020). The impact of physical activity on psychological health during Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. Heliyon, 6(6), e04315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04315

- McKune, S. L., Acosta, D., Diaz, N., Brittain, K., Beaulieu, D. J., Maurelli, A. T., & Nelson, E. J. (2021a). Psychosocial health of school-aged children during the initial COVID-19 safer-at-home school mandates in Florida: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 603. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10540-2

- Meherali, S., Punjani, N., Louie-Poon, S., Abdul Rahim, K., Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., & Lassi, Z. S. (2021). Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: A rapid systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073432

- Melegari, M. G., Giallonardo, M., Sacco, R., Marcucci, L., Orecchio, S., & Bruni, O. (2021). Identifying the impact of the confinement of Covid-19 on emotional-mood and behavioural dimensions in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Research, 296, 113692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113692

- Mohler-Kuo, M., Dzemaili, S., Foster, S., Werlen, L., & Walitza, S. (2021). Stress and mental health among children/Adolescents, their parents, and young adults during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Switzerland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094668

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Sears, K., Sfetcu, R., Currie, M., Lisy, K., Tufanaru, C., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., & Mu, P. (2015). Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute’s approach. JBI Evidence Implementation, 13(3), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000064

- Moy, F. M., & Ng, Y. H. (2021). Perception towards E-learning and COVID-19 on the mental health status of university students in Malaysia. Science Progress, 104(3), 00368504211029812. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504211029812

- Muller, A. E., Hafstad, E. V., Himmels, J. P. W., Smedslund, G., Flottorp, S., Stensland, S. Ø., Stroobants, S., Van de Velde, S., & Vist, G. E. (2020). The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441

- Munn, Z., Moola, S., Lisy, K., Riitano, D., & Tufanaru, C. (2015). Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054

- Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., & Jordan, Z. (2018). What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

- Nearchou, F., Flinn, C., Niland, R., Subramaniam, S. S., & Hennessy, E. (2020). Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes in children and adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228479

- Newby, J. M., O’Moore, K., Tang, S., Christensen, H., & Faasse, K. (2020). Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. PLOS ONE, 15(7), e0236562. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236562

- Nuñez, A., Le Roy, C., Coelho-Medeiros, M. E., & López-Espejo, M. (2021). Factors affecting the behavior of children with ASD during the first outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurological Sciences, 42(5), 1675–1678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05147-9

- Okely, A. D., Kariippanon, K. E., Guan, H., Taylor, E. K., Suesse, T., Cross, P. L., Chong, K. H., Suherman, A., Turab, A., Staiano, A. E., Ha, A. S., El Hamdouchi, A., Baig, A., Poh, B. K., Del Pozo-Cruz, B., Chan, C. H. S., Nyström, C. D., Koh, D., Webster, E. K., & Draper, C. E. (2021). Global effect of COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep among 3- to 5-year-old children: A longitudinal study of 14 countries. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 940. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10852-3

- Oosterhoff, B., Palmer, C. A., Wilson, J., & Shook, N. (2020). Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with mental and social health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Paiva, E. D., Silva, L. R. D., Machado, M. E. D., Aguiar, R. C. B. D., Garcia, K. R. D. S., & Acioly, P. G. M. (2021). Child behavior during the social distancing in the COVID-19 pandemic. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 74(suppl 1), e20200762. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0762

- Paslakis, G., Dimitropoulos, G., & Katzman, D. K. (2021). A call to action to address COVID-19–induced global food insecurity to prevent hunger, malnutrition, and eating pathology. Nutrition Reviews, 79(1), 114–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa069

- Paus, T., Keshavan, M., & Giedd, J. N. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(12), 947–957.

- Phiri, P., Ramakrishnan, R., Rathod, S., Elliot, K., Thayanandan, T., Sandle, N., Haque, N., Chau, S. W. H., Wong, O. W. H., Chan, S. S. M., Wong, E. K. Y., Raymont, V., Au-Yeung, S. K., Kingdon, D., & Delanerolle, G. (2021). An evaluation of the mental health impact of SARS-CoV-2 on patients, general public and healthcare professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 34, 100806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100806

- Pınar Senkalfa, B., Sismanlar Eyuboglu, T., Aslan, A. T., Ramaslı Gursoy, T., Soysal, A. S., Yapar, D., & İlhan, M. N. (2020). Effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on anxiety among children with cystic fibrosis and their mothers. Pediatric Pulmonology, 55(8), 2128–2134. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.24900

- Pisano, S., Catone, G., Gritti, A., Almerico, L., Pezzella, A., Santangelo, P., Bravaccio, C., Iuliano, R., & Senese, V. P. (2021). Emotional symptoms and their related factors in adolescents during the acute phase of Covid-19 outbreak in South Italy. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 47(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-021-01036-1

- Pizarro-Ruiz, J. P., & Ordóñez-Camblor, N. (2021). Effects of Covid-19 confinement on the mental health of children and adolescents in Spain. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 11713. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91299-9

- Posel, D., Oyenubi, A., Kollamparambil, U., & Picone, G. A. (2021). Job loss and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown: Evidence from South Africa. PLOS ONE, 16(3), e0249352. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249352

- Qin, Z., Shi, L., Xue, Y., Lin, H., Zhang, J., Liang, P., Lu, Z., Wu, M., Chen, Y., Zheng, X., Qian, Y., Ouyang, P., Zhang, R., Yi, X., & Zhang, C. (2021). Prevalence and risk factors associated with self-reported psychological distress among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. JAMA Network Open, 4(1), e2035487. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35487

- Raviv, T., Warren, C. M., Washburn, J. J., Kanaley, M. K., Eihentale, L., Goldenthal, H. J., Russo, J., Martin, C. P., Lombard, L. S., Tully, J., Fox, K., & Gupta, R. (2021a). Caregiver perceptions of children’s psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), e2111103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11103

- Raviv, T., Warren, C. M., Washburn, J. J., Kanaley, M. K., Eihentale, L., Goldenthal, H. J., Russo, J., Martin, C. P., Lombard, L. S., Tully, J., Fox, K., & Gupta, R. (2021b). Caregiver perceptions of children’s psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), e2111103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11103

- Rogers, A. A., Ha, T., & Ockey, S. (2021). Adolescents’ perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: Results from a U.S.-based mixed-methods study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.039

- Sama, B. K., Kaur, P., Thind, P. S., Verma, M. K., Kaur, M., & Singh, D. D. (2021). Implications of COVID‐19‐induced nationwide lockdown on children’s behaviour in Punjab, India. Child: Care, Health and Development, 47(1), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12816

- Saurabh, K., & Ranjan, S. (2020). Compliance and psychological impact of quarantine in children and adolescents due to Covid-19 pandemic. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 87(7), 532–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3

- Segre, G., Campi, R., Scarpellini, F., Clavenna, A., Zanetti, M., Cartabia, M., & Bonati, M. (2021). Interviewing children: The impact of the COVID-19 quarantine on children’s perceived psychological distress and changes in routine. BMC Pediatrics, 21(1), 231. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02704-1

- Shekerdemian, L. S., Mahmood, N. R., Wolfe, K. K., Riggs, B. J., Ross, C. E., McKiernan, C. A., Heidemann, S. M., Kleinman, L. C., Sen, A. I., Hall, M. W., Priestley, M. A., McGuire, J. K., Boukas, K., Sharron, M. P., & Burns, J. P., for the International COVID-19 PICU Collaborative. (2020). Characteristics and outcomes of children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection admitted to US and Canadian pediatric intensive care units. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1948

- Shek, D. T. L., Zhao, L., Dou, D., Zhu, X., & Xiao, C. (2021). The impact of positive youth development attributes on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Chinese adolescents under COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(4), 676–682.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.011

- Tang, S., Xiang, M., Cheung, T., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2021). Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016

- Thapa, P., Bhandari, S. L., & Pathak, S. (2021). Nursing students’ attitude on the practice of e-learning: A cross-sectional survey amid COVID-19 in Nepal. PLOS ONE, 16(6), e0253651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253651

- Unesco, U. (2020). COVID-19 educational disruption and response. Unesco.

- Verschuur, J., Koks, E. E., & Hall, J. W. (2021). Global economic impacts of COVID-19 lockdown measures stand out in high-frequency shipping data. PLOS ONE, 16(4), e0248818. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248818

- Wang, J., Wang, H., Lin, H., Richards, M., Yang, S., Liang, H., Chen, X., & Fu, C. (2021). Study problems and depressive symptoms in adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: Poor parent-child relationship as a vulnerability. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00693-5

- Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., & Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet, 395(10228), 945–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X

- WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020

- Wu, K. K., Chan, S. K., & Ma, T. M. (2005). Posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(1), 39–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20004

- Xie, X., Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 898. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

- Yeasmin, S., Banik, R., Hossain, S., Hossain, M. N., Mahumud, R., Salma, N., & Hossain, M. M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Children and Youth Services Review, 117, 105277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105277

- Zhang, C., Ye, M., Fu, Y., Yang, M., Luo, F., Yuan, J., & Tao, Q. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teenagers in China. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(6), 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.026

- Zhang, L., Zhang, D., Fang, J., Wan, Y., Tao, F., & Sun, Y. (2020a). Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2021482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21482

- Zhang, L., Zhang, D., Fang, J., Wan, Y., Tao, F., & Sun, Y. (2020b). Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2021482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21482

- Zhang, X., Zhu, W., Kang, S., Qiu, L., Lu, Z., & Sun, Y. (2020). Association between physical activity and mood states of children and adolescents in social isolation during the COVID-19 epidemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207666

- Zhou, S.-J., Wang, -L.-L., Yang, R., Yang, X.-J., Zhang, L.-G., Guo, Z.-C., Chen, J.-C., Wang, J.-Q., & Chen, J.-X. (2020). Sleep problems among Chinese adolescents and young adults during the coronavirus-2019 pandemic. Sleep Medicine, 74, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.001

- Zhou, S.-J., Zhang, L.-G., Wang, -L.-L., Guo, Z.-C., Wang, J.-Q., Chen, J.-C., Liu, M., Chen, X., & Chen, J.-X. (2020a). Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(6), 749–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4

- Zreik, G., Asraf, K., Haimov, I., & Tikotzky, L. (2021). Maternal perceptions of sleep problems among children and mothers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic in Israel. Journal of Sleep Research, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13201