Abstract

It has been suggested that with age comes experience in how to deal effectively with stressors, and therefore resources needed to uphold constructive leadership behaviors partly depend on managers’ age. This relation between age and leadership behaviors may also depend on the level of support that managers are given. In the present study, we depart from Conservation of resource theory and lifespan theory to examine the link between managers’ age and inefficient leadership, with stress as a mediator in this relation. We also investigate whether social support buffers the relations between managers’ age, stress, and inefficient leadership. Self-report survey data from a randomly selected sample of Swedish managers were collected at two time points, six months apart. In total, 781 managers answered the survey at both times. We found that, as expected, managers age was negatively related to inefficient leadership through stress. In other words, younger managers perceive themselves as more stressed and because of that more inefficient. Contrary to what we expected, these relations were not influenced by social support. Our study is among the first to study managers’ age as an antecedent to inefficient leadership behaviors. The study also adds to the understanding of this relation by including stress as a mechanism. Furthermore, our research contributes to the examination of potential boundary conditions for when age may translate into stress and inefficient work behaviors by investigating social support as a potential moderator.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

The ability to deal with stressors and consequently uphold constructive managerial role behaviors has partly been suggested to depend on managers’ age (Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013; Zacher et al., Citation2015). Although under-researched, a proposed explanation for such age-based differences in behaviors is that with older age comes more resources, for example in terms of abilities to regulate emotion (Kim & Kang, Citation2017; Scheibe et al., Citation2021). Unlike older managers, younger managers may thus find it hard to rely on maturity and wisdom to anticipate problems and calmly respond (Oshagbemi, Citation2004). From a lifespan perspective (Baltes, Citation1987), younger managers may therefore more easily find themselves in situations where they lack resources and strategies to deal with stress, and consequently become inefficient. Younger and older managers are here to be understood in relative terms. Lifespan theory suggests that development is a continuous process, and therefore age should be studied as a continuous variable (Zacher et al., Citation2015).

Managers’ inefficient leadership are characterized by acting messy, confused, and insecure, for example by giving vague instructions and being unable to provide a clear structure and plans for operations (Larsson et al., Citation2012). Although a distinct set of behaviors, these inefficient leadership behaviors share similarities in terms of outcomes with a passive leadership style, such as acting laissez-faire (Larsson et al., Citation2012; Lundmark et al., Citation2021). In general, few studies have researched the link between managers’ age and their leadership behaviors, and findings thus far show mixed results (Zacher et al., Citation2015). These inconsistent results have been argued due to the neglect of examining mediating mechanisms, and a fragmented understanding of moderators in the age–leadership process (Scheibe et al., Citation2021).

Thus, the aim of the present study is to examine whether managers’ stress constitutes a mediating mechanism in the relation between their age and inefficient leadership behaviors. We thereby add to the sparse literature on lifespan research in management that take in consideration that different developmental aspects and challenges may face managers depending on their age. By increasing our understanding of why managers’ age may make them more or less vulnerable to exerting inefficient leadership behaviors, we can also start developing appropriate measures to counteract the development of such actions within the managerial role. Thereby potentially also helping those of younger age in their transition into a more efficient managerial role.

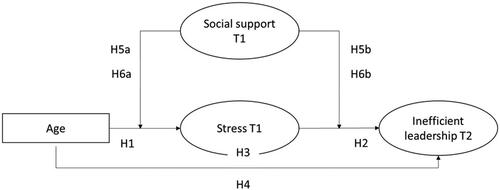

Furthermore, from a contextual perspective, situational factors may act as key boundary conditions in the interplay between managers’ age, stress, and leadership behaviors (Oc, Citation2018; Scheibe et al., Citation2021). Managers’ social context in terms of support (i.e. from the organization and from peers), may be seen as potential resources that can buffer the influence of age on stress so that the relation between age and stress is reduced. It can also shape how differences in levels of stress translate into managers’ behaviors (Hobfoll et al., Citation1990; Scheibe et al., Citation2021). Hence, to find out more about the potential contextual boundary conditions of age–stress-inefficient leadership relations, an additional aim of our study is to examine the buffering impacts of managers’ perceived social support (see for hypothesized relations). In doing so our study also contributes to answering what can be done to reduce age-dependent differences in managers’ stress and inefficient leadership, an area of research in which more studies have been called for (Larsson & Björklund, Citation2021).

Theory and hypothesis

Managers’ age as an antecedent to their levels of stress

Conservation of Resource Theory (COR; Hobfoll, Citation1989) stipulates that individuals’ ability to manage stressors are dependent on their possibilities to acquire and maintain resources (e.g. in terms of personal resources such as skills, experience and efficacy). For example, a manager with experience from handling difficult situations in the past may have gained knowledge and efficacy to more effectively, and calmly, deal with present challenges (Oshagbemi, Citation2004). Hence, when there is a lack of resources, possibilities to cope with stressors are reduced which can result in increased levels of stress (Hobfoll, Citation1989).

From a life-span perspective, becoming older has been suggested to strengthen personal resources, as with age comes maturity and experience of challenging events (Oshagbemi, Citation2004). Consequently, life-span development theories suggest that age is important for managers’ capability to process and regulate emotions (Scheibe et al., Citation2021; Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013). It has also been proposed that motivation and efficiency in avoiding or down-regulating high-arousal affective work events increases with age, which reduces stress (Scheibe & Zacher, Citation2013). Alternatively, it has been suggested that as individuals become older, they also become more better at choosing and using regulatory strategies that are effective given the context and their resources at hand. In turn, the use of more effective emotional regulation strategies is related to positive wellbeing (Mikkelsen et al., Citation2023). In support of these claims, research has also shown that managers’ development of emotional skills and emotional regulation is age-related. Furthermore, that such development is not only based on experience in the managerial role but a result of a combination of developmental experiences along multiple dimensions (e.g. neurobiological as well as social) both on and off the job and over time (Baltes, Citation1987; Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013). Older managers have also been found to report less sources of stress and being able to cope better with stress (Siu et al., Citation2001). Results from a recent study reveals that younger managers suffer from higher levels of burnout and lower levels of vigor when compared to older managers (Irehill et al., Citation2023). Similarly, positive relations between age and affective wellbeing in general have also been found (i.e. older persons rate higher wellbeing; Reed & Carstensen, Citation2012).

Thus, combining COR theory with the suggestions from life-span development research on differences in managers’ abilities to handle stressors depending on age, younger, rather than older, managers are more likely to experience stress. This is because younger managers have less access to resources in terms of strategies for handling demanding situations. Alternatively, they may have harder time to appropriately match strategies with the situation at hand. Based on these arguments we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis1: Managers’ age is negatively associated with their levels of stress at Time 1 (T1).

The association between managers’ level of stress and their inefficient leadership behaviors

A manager acting inefficient can be stressful and performance inhibiting for employees (Larsson et al., Citation2012; Lundmark et al., Citation2021). However, although a clear picture of the outcomes of an inefficient leadership style are starting to emerge, less is known about what causes managers to act in such fashion, and hence what can be done to reduce it (Harms et al., Citation2017). Kaluza et al. (Citation2020) in a review of the literature suggests that less effective leadership forms can in part be understood as a result of managers’ lack of resources to deal with stressors. From a COR perspective (Hobfoll, Citation1989), managers’ personal resources are critical for their possibility to perform an effective leadership (Byrne et al., Citation2014). Thus, managers stress, resulting from the inability to access personal resources (i.e. such as adequate emotional regulation strategies) may contrary increase their use of inefficient leadership behaviors (Arnold et al., Citation2015). Research on the influence of stress on leadership behaviors are still sparse, especially when it comes to how stress influence managers’ inefficient leadership styles (Kaluza et al., Citation2020; Arnold et al., Citation2015). However, from a theoretical perspective, managers’ experiencing stress may strive to protect or conserve remaining resources by reducing their involvement in managerial role designated behaviors (Byrne et al., Citation2014). For example, they can spend less time on preparations and planning and hence experience themselves as more unclear and messier in their communication with employees. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2: Managers’ level of stress at T1 is positively associated with their levels of inefficient leadership behaviors at 6-month follow-up (T2).

Managers’ age indirect and direct relation to their inefficient leadership behaviors

Age is sometimes used as a control variable or moderator in organizational and management research (Zacher et al., Citation2015), but studies that directly examine the influence of age and work outcomes are rare (Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013). Research on the relation between managers’ age and behavioral outcomes in terms of leadership is even more rare (Rosing & Jungmann, Citation2019). Only recently, managers’ age as an antecedent to leadership behaviors has received a more focused attention, primarily because of the general growing interest for researching an aging workforce (Zacher et al., Citation2015).

In the present suggested lifespan models on managers’ age and its relation to leadership behaviors, age is an antecedent that may influence their task competence, interpersonal attributes, and motivation to lead (Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013). Among these characteristics, managers’ emotional stability is highlighted as a factor that can be expected to increase over adulthood, and thereby contribute to improved efficiency (Zacher et al., Citation2015). From that, age can be considered important for the development of emotional regulation strategies, as personal resources to counteract work related stress (Oshagbemi, Citation2004), and in turn perform an efficient leadership (Zacher et al., Citation2015; Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013). Thus, since younger, rather than older, managers can be expected to experience higher levels of stress, younger managers can also indirectly be expected to express more inefficient leadership behaviors. We therefore hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3: Managers’ age is indirectly negatively associated with their inefficient leadership at behaviors at T2, mediated by their levels of stress at T1.

In addition to an indirect relation between managers’ age and inefficiency, a direct relation to their inefficient leadership may be present. Younger managers can for example be less skillful in building trustful relationships and less developed capabilities for interpersonal communication (Benjamin & O’reilly, Citation2011; Larsson & Björklund, Citation2021). In the few studies that examine the relation between managers’ age and leadership behaviors findings have been mixed. Some provide evidence for such direct relations (e.g. Barbuto et al., Citation2007), and others not or only in part (e.g. Zacher et al., Citation2011). Among studies focusing on ineffective leadership styles, a number have found a positive relation between age and laissez-faire leadership (i.e. withdrawing from responsibilities, not being present when needed; Skogstad et al., Citation2014), indicating that older managers may be perceived as more passive, whereas some found non-significant effects (see for example the compilation of studies in Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013). Contrary, Larsson & Björklund (Citation2021) in a mixed industry sample found younger managers to self-report acting inefficient more frequently compared to older colleagues.

These mixed results could perhaps be seen as a result of context or source of ratings or form of ineffective leadership styles being evaluated. In similarity to Larsson & Björklund (Citation2021), we use self-ratings from a mixed sample of managers and study inefficient leadership behaviors. These leadership behaviors also differ from laissez-faire in that they do not include withdrawal or non-presence, instead they deal with actions such as unclear communication, insecurity in decisions, flawed planning, and creating confusion (Larsson et al., Citation2012). Therefore, in addition to a negative indirect relation, we suggest that younger managers are inclined to view themselves as more derail from expected managerial role behaviors (i.e. as acting more inefficient regardless of stress levels). Consequently, we hypothesis that:

Hypothesis 4: Managers’ age is directly negatively associated with their inefficient leadership at behaviors at T2.

Social support as a contextual buffer in the age - stress - inefficient leadership relation

Context have been proposed to play an important role for the understanding of the circumstances in which age differences plays an important role for managers’ experience and for their behaviors (Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013). Consequently, beyond the above outlined main-effects (i.e. mediation) model, Walter & Scheibe (Citation2013) suggest a context-specific model to account for the interplay of situational factors in the relations between age – emotions – behaviors. Here contextual factors are seen as potential boundary conditions for when age may translate into work behaviors (i.e. such as leadership actions; Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013).

Both in leadership research in general, as well as in studies focusing on age differences in leadership behaviors, contextual factors as boundary condition are understudied (e.g. in comparison with individual factors such as personality or skills; Oc, Citation2018; Zacher et al., Citation2015). At the same time explanations for variability in age dependent differences in outcomes between different studies is often attributed to context, and therefore calls for finding out how context may shape this process have been made (Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013; Zacher et al., Citation2015). Among contextual factors that may act as a buffer, both in the age – stress relation and in the stress – inefficient leadership relation, managers’ perceptions of their social context may play a crucial role (Hobfoll et al., Citation1990; Oc, Citation2018).

Managers’ social context is often highlighted as a vital for boosting their performance (e.g. Milner et al., Citation2018). Such support has also repeatedly portrayed as a potential contextual buffer that can help reduce the influence of deteriorating antecedents on both wellbeing and inefficient behaviors (Jolly et al., Citation2021). From a COR perspective the social context provides resources that can help mitigate or compensate for the depleting effect that a lack of other resources (e.g. personal) may have (Hobfoll et al., Citation1990). A high degree of social resources may thus boost personal resources (e.g. in terms of self-efficacy), or replace other resources to buffer the influence of stressors on outcomes of stress (Hobfoll et al., Citation1990; Wikhamn & Hall, Citation2014). Two significant social resources suggested to be able to buffer strain in leadership processes are the support provided to managers by their organization and by their peers (Oc, Citation2018).

Organizational support, as a component of social support, can be understood as the degree to which individuals perceive that their organization values their contribution and cares about their wellbeing (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002). Organizational support has been associated with a range performance and wellbeing outcomes, including negatively associated with stress (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017). Beyond direct relations, organizational support has been suggested to have a buffering effect on the relation between stressors and stress, and between stress and wellbeing outcomes (Jolly et al., Citation2021). Thus, we suggest that organizational support may constitute a boundary condition for when age differences matter for experiencing stress and for when stress matters for being inefficient. Based on theory and the above-mentioned findings we therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5: Managers’ organizational support at T1 moderates (a) the relation between managers’ age and stress at T1, and (b) the relation between managers’ stress at T1 and inefficient leadership behaviors at T2. Organizational support influences these associations so that the negative relation between age and stress, and positive relation between stress and inefficient leadership, is reduced when organizational support is high rather than low.

Peer support, as a component of social support, refers to colleagues giving and receiving help based on a shared understanding of what is helpful, mutual respect and responsibility for operations (Mead et al., Citation2001). As for organizational support, peer support has been suggested to boost performance and wellbeing, and help reduce stress (Agarwal et al., Citation2020). As for organizational support, we suggest that peer support may also constitute a social resource that act as a boundary condition for when age differences influence stress and for when stress influence inefficient leadership. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 6: Mangers’ peer support at T1 moderates (a) the relation between managers’ age and stress at T1, and (b) the relation between managers’ stress at T1 and inefficient leadership behaviors at T2. Peer support influences these associations so that the negative relation between age and stress, and positive relation between stress and inefficient leadership, is reduced when peer support is high rather than low.

Methods

Sample and procedures

With the help of Statistics Sweden (i.e. a government agency), individuals in managerial positions were randomly selected from the Swedish occupational register. The register covers all Swedish wageworkers and is yearly updated. In the register, occupations are reported according to the Swedish Standard Classification of Occupations, in which individuals holding managerial positions can be identified. At the first time point (T1, spring 2019), 5000 managers (out of approximately 300 000 managers, with at total workforce of approximately 4 500 000) were invited to participate. The invitation was sent by mail, with a physical questionnaire to be filled in and returned using an attached response envelope. The possibility to answer via an online version was also given by providing secure personal logins in the mailed invitations. Of those invited, 1331 responded (27%) after three friendly reminders. These respondents also received a follow-up survey after 6 months (T2, autumn 2019). After friendly reminders, the response rate at T2 was N = 781 (59% of the respondents at T1). These 781 managers constitute the panel sample of our study. The mean age of the participating managers was 48.73 (SD = 10.42, ranging between 19 and 65 years of age), 66% had a university degree, and 48% were females. On average, they had been working as a manager for 11.3 years (SD = 8.68) and at their current workplace for 6.63 years (SD = 5.99). No statistically significant differences were found in terms of age, gender, education level or tenure between managers answering to the survey at T1 compared to T2. Compared to the managerial workforce in Sweden at large the present sample is somewhat of older age, of female gender, of higher education and among managers in public organizations, and of individuals born in Sweden. A pattern found in many labor force studies (Statistics Sweden, Citation2023).

Measures

The internal consistency (reliability) in terms of Omega (ω) of all scales are reported in . All measures used are well-validated in a general work context, please see references below for further information on validity and reliability of the used scales.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Managers’ age

Managers’ age was obtained from the Swedish occupational register and was measured as a chronological variable.

Stress

Managers perceived stress was measured using a four-item scale from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire 2nd version, COPSOQ II (Pejtersen et al., Citation2010), a questionnaire that has been validated in a multitude of settings and languages (including Swedish; Berthelsen et al., Citation2014). Responses ranged from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘all the time’). An example item is ‘How often have you been tense’.

Inefficient leadership

Managers perceived inefficient leadership was assessed with a four-item scale ‘Uncertain, unclear, and messy’ from Destrudo-L (Larsson et al., Citation2012). Although Destrudo-L was originally developed in a military setting, it has recently been validated in a general workforce context (Lundmark et al., Citation2021). Answers ranged from 1 (‘never/hardly ever’) 6 (‘always/almost always’) on a six-point Likert scale. An example item is ‘I give unclear instructions’.

Organizational support

Managers perceived organizational support was measured through a three-item scale from COPSOQ II (Pejtersen et al., Citation2010). Responses were given on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 7 (‘strongly agree’). An example item is ‘My organization cares about my opinions’.

Peer support

Managers perceived peer support was obtained through a three-item scale from COPSOQ II (Pejtersen et al., Citation2010). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘never/hardly ever’) to 5 (‘always’). An example item is ‘How often are your colleagues willing to listen to your problems at work?’

Control measures

Manager s’ gender has in leadership research (Eagly & Johnson, Citation1990), as well as in research on the influence of managers’ age (e.g. Buengeler et al., Citation2016), been found to influence behavioral and wellbeing outcomes. Larsson & Björklund (Citation2021) found that young male managers, compared with older male managers and female managers, reported higher levels of inefficient leadership behaviors. In contrast, female managers, compared with male managers, are generally found to report higher levels of stress (Gyllensten & Palmer, Citation2005). Thus, to reduce the risk of gender as an additional-variable explanation to the hypothesized age-based differences, managers’ reports on stress and inefficient leadership was controlled for using data on their registered gender (1= male, 2 = female). Additionally, in research, managers’ lack of social support has been found to influence their stress and inefficient leadership (Jolly et al., Citation2021, Schilling, Citation2009). Therefore, for the same reason as above, we controlled for managers’ organizational and peer support for both their reported stress and inefficient leadership in the structural model (i.e. testing hypotheses 1-4). In subsequent interaction analyses (hypotheses 5-6), organizational and peer support are instead modeled as moderators, and therefore only gender is used as a control variable.

Analysis

All data analyses were performed in Mplus version 8.8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998-2017), with robust full information maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) to account for potential nonnormality (Little, Citation2013). The only exception was for bootstrapping procedures to test indirect effect as only the maximum likelihood estimator (ML) is optional. Statistically significant differences in our examinations were determined using a significance level of p < .05. The analyses were conducted sequentially in three steps:

First, a measurement model (confirmatory factor analysis; CFA; Little, Citation2013), including all latent variables (i.e. stress, inefficient leadership, organizational support and peer support), was estimated. Model fit of the measurement model was assessed using the conventional fit indices provided in Mplus: the comparative fit index, CFI; the Tucker-Lewis index, TLI; the standardized root mean residual, SRMR; and the root mean square error of approximation; RMSEA. As cut-off criteria’s, CFI and TLI > .90; and SRMR and RMSEA < .08, would indicate an acceptable fit, whereas CFI and TLI > .95; and SRMR < .08 and RMSEA < .06, would indicate a good fit (Kline, Citation2023).

Second, to test hypothesis 1, 2 and 3, a structural model was estimated. Here, inefficient leadership at T2 was regressed on managers’ reported stress at T1 and their age, and stress regressed on age. The control variables (i.e. gender, organizational support at T1, and peer support at T1) were set to predict managers’ stress and inefficient leadership. Additionally, organizational support and peer support were allowed to covary, as by default setting in Mplus, to reduce the risk of biased estimates. To test the indirect effect of age on inefficient leadership at T2 through stress we used the model indirect command, and to confirm the indirect relation we also used the recommended bootstrapping procedure (Rucker et al., Citation2011). We used a bootstrapping sample of 5000 to estimate biased-corrected confidence intervals (CI) at 95%.

Third, to test hypotheses 4 and 5, interaction terms between age and organizational support at T1, and age and peer support at T1, and stress at T1 and organizational support at T1, and stress at T1 and peer support at T1 were added to the structural model. All in accordance with the suggested theoretical model for testing contextual influence in these relations (Scheibe et al., Citation2021).

Results

Descriptive statistics for variables, bivariate correlations, and scale reliability estimates (omega; ω), are presented in .

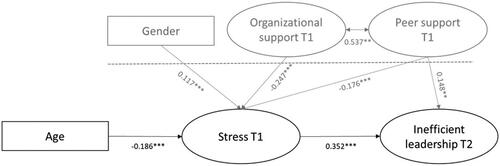

The measurement model showed an acceptable fit, χ2 (146) = 442.146, p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.051 [90% CI 0.046 0.056], CFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.932, SRMR = 0.044, wherefore we continued to estimate the structural model. The model fit of the structural model, testing main and mediated effects, (see ) was also deemed acceptable, χ2 (180) = 639.674, p = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.057 [90% CI 0.052 0.062], CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.901, SRMR = 0.051. In the model, with control for gender, organizational support at T1 and peer support at T1, age was negatively related to stress at T1 (β = –0.186, p < 0.000), and stress at T1 positively related to inefficient leadership at T2 (β = 0.352, p < 0.000). Thus, hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported. The test of specific indirect effects (hypothesis 3) showed that age was indirectly negatively related to inefficient leadership at T2 (β = –0.065, p < 0.000), which was confirmed by the bootstrapping procedure (95% CI [–0.100 –0.037]). Thus, hypothesis 3 was also supported, younger managers were more likely to experience stress, and therefore indirectly act more inefficiently. No statistically significant direct relation between age and inefficient leadership (hypothesis 4) was found (β = –0.054, p = 0.226). Gender as a control measure was related to stress in the expected direction (i.e. indicating that female leaders perceive higher levels of stress, β = 0.117, p = 0.001), but not related to inefficient leadership (β = –0.040, p = 0.312). Likewise, organizational support at T1 was related to stress at T1 (β = –0.247, p < 0.000), but not inefficient leadership at T2 (β = –0.022, p = 0.682). As expected, peer support was also negatively related to stress (β =–0.176, p < 0.001), but unexpectedly positively related to inefficient leadership (β = 0.148, p = 0.009).

Figure 2. Structural equational model.

Note. N = 781. Non-statistically significant paths were omitted for presentation parsimony. Control variables above the dotted line. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The subsequent test of the context-specific moderation model included four interaction terms. The interactions of age and organizational support at T1 and age and peer support at T1 in the age-stress relation, as well as stress at T1 with organizational support at T1 and stress at T1 with peer support at T1 in the stress–inefficient leadership relation. The confidence intervals of model results showed that none of these interactions were statistically significant. Neither organizational support at T1 (95% CI [–0.005 0.010]), nor peer support at T1 (95% CI [–0.014 0.006]), moderated the relation between age and stress at T1. Similarly, neither organizational support at T1 (95% CI –0.022 0.149]), nor peer support at T1 (95% CI [–0.193 0.068]), moderated the relation between stress at T1 and inefficient leadership at T2. Thus, hypotheses 4 and 5 were rejected.

Post-hoc analyses

As it could be argued that stress may be perceived as more of a situational state and therefore not lasting over a period of 6-months, we retested the model cross-sectionally with the same panel sample (N = 781), using measures of both stress and inefficient leadership at T1. The model fit of this cross-sectional model was χ2 (180) = 624.873, p = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.056 [90% CI 0.051 0.061], CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.901, SRMR = 0.052. These model fit results are only marginally different from the above tested model with two measurement-points. Overall, all tested relations revealed similar strength in relations in both models. However, in the cross-sectional model the relation between stress and inefficient leadership was somewhat stronger compared to the same relation in the model using two measurement points (β = 0.386, p < 0.000 in the cross-sectional model vs. β = 0.352, p < 0.000 in the structural model). This difference could likely be explained by a common method variance effect in the cross-sectional model. A subsequent test of the correlation between stress at T1 and stress at T2 also indicated that the perceived level of stress among participants was relatively stable over time (β = 0.770, p < 0.000).

It could also be reasoned that tenure in the managerial role can be an alternative explanation to the found results. As our survey included a question on managerial tenure, we therefore we re-tested the structural model using this variable as an additional control. Model results were not far from that of the above tested structural model. χ2 (197) = 472.984, p = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.056 [90% CI 0.050 0.063], CFI = 0.916, TLI = 0.902, SRMR = 0.055. None of the significant relations in the model were altered (i.e. age was related to stress, and stress was related to inefficient leadership). In the model, managerial tenure had no statistically significant relation with stress (β = –0.064, p = 0.279), but a relation was found related to inefficient leadership (β = –0.222, p = 0.001). Because only 446 of the respondents had answered the question of managerial tenure, we chose not to include this variable in the above analyses as this would reduce the sample size substantially. Additionally, although the test of the moderation model terminated normally, we performed post-hoc tests with each interaction term tested separately to see if this would alter the non-statistically significant interaction results, which it did not.

Discussion

The present study sought to uncover the mechanisms by which managers’ age may be linked to inefficient leadership behaviors, and answer calls to examine the mediating process between managers’ age and leadership behaviors (Scheibe et al., Citation2021; Walter & Scheibe, Citation2013; Zacher et al., Citation2015). In line with the suggested mediation model (), we found that stress mediated the relation between managers’ age and inefficient leadership behaviors (hypotheses 1, 2 and 3). As we found no direct relation between managers’ age and their inefficient leadership behaviors (hypothesis 4), the results suggest that younger managers as a group act more inefficiently than older leaders because of stress. In turn this can be explained by that younger managers have fewer, less developed, or less appropriates strategies to manage strain than their older colleagues. Alternatively, be more exposed to stressors overall. In turn this may trigger, and in part explain why younger managers are somewhat more prone to display inefficient leadership behaviors. From a COR theory perspective (Hobfoll, Citation1989), the results emphasize the importance for organizations in helping, especially younger, managers to access resources that can reduce their level of stress and/or make them less vulnerable for becoming inefficient when experiencing stress.

To understand this process, we examined whether support from peers or the organization could be understood as context-specific social resources that could help buffer against stress and inefficient leadership behaviors, as proposed by Scheibe et al. (Citation2021) context-specific model. However, we found no support for such claims (hypotheses 5 and 6). These findings could be seen as somewhat surprising. In previous studies focusing on age as an antecedent to managers’ experiences and behaviors, social support has been highlighted as a measure for helping especially younger managers who may struggle with the transition into a managerial role and identity (Larsson & Björklund, Citation2021; Uen et al., Citation2009). In addition, support is often suggested as a buffer against stress in models of the work environment (e.g. Hobfoll et al., Citation1990). Contrary to such suggestions, in the structural model we also unexpectedly found peer support (as a control measure) to be positively associated with inefficient leadership.

A possible explanation for these results may be found in the dual outcome paths that social support may include. That is, beyond being perceived as a resource it can also induce a felt obligation to return support from others, thereby increasing levels of stress and inefficient behaviors (Jolly et al., Citation2021; Thompson et al., Citation2020). In addition, there is also a lack of knowledge on what kind of social resources matter for managers, and if these differ depending on managers age (Scheibe et al., Citation2021). Thus, we suggest that future research examine more specifically what support young managers are in need of, as well as whether other contextual factors, such as role clarity or provision of leadership training, are more successful in reducing levels of stress and inefficient leadership behaviors.

Implications for research and practice

Our study contributes to the growing field of a lifespan perspective on leadership (Zacher et al., Citation2015). Our findings indicate that managers’ age does matter for what kind of leadership behavior that they report, and that young managers perceive themselves as more inefficient compared to older colleagues. In addition, by using COR theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989), we shed light on stress as the mechanisms that can explain why inefficient leadership behavior seems to differ by age. Studies of leadership behavior from a lifespan perspective are still scarce (Irehill et al., Citation2023), and we suggest that future research continue to examine when, how, and why leadership may differ by age. In particular, future studies could focus on other forms of leadership, in an effort to uncover whether the same processes are present there. As research have shown mix results when it comes to the relation between managers’ age and laissez-faire leadership, we suggest that examining if this can be explained by a similar mediation process.

From a practical perspective, our study offers a number of implications for organizations. Given that stress is a trigger of inefficient leadership behaviors, it is important for organizations to help (especially young) managers develop favorable strategies to deal with the strain that may come with the managerial role. Beyond raising awareness of inefficient leadership and its consequences, this could also include training in emotional regulation skills to increase resilience (Edelman & Van Knippenberg, Citation2017; Haver et al., Citation2013), for example, as part of leadership development programs. However, to prevent the emergence of inefficient leadership behaviors due to stress, it is also important to ensure that young managers are provided with good working conditions, with a balance between demand and resources (Irehill et al., Citation2023). Thus, giving them possibilities to grow successively and successfully into the managerial role. It may also be beneficial for organizations to provide young managers with more specific forms of developmental support, such as mentoring programs (Benjamin & O’reilly, Citation2011), and flexible working conditions (Tulgan, Citation2011), to further reduce the risk of stress and inefficient leadership.

Study limitations and future research directions

The findings of the present study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, we relied on managers’ self-ratings of stress and inefficient leadership behaviors, which are susceptible to common method bias and thus may inflate relations between the two constructs (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). However, in the current study we separated the measurement of stress and inefficient leadership behaviors in time, which may reduce such risks (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Our results can also be seen as in line with previous findings based on employee ratings of managers. For example, Barbuto et al. (Citation2007) showed that older managers were perceived more efficient than younger by their employees. Although manager self-ratings are not uncommon in studies of leadership behavior (Arnold et al., Citation2015), future research may strengthen confidence in our findings by using a multilevel design with manager ratings of stress and employee ratings of inefficient leadership. In future, adapting questions, for example on peer-support, to better target managers conditions (i.e. clarifying manager-peers rather than peers in general) could also be helpful in this line of research.

Second, we only had two measurement points six months apart, which is suboptimal in regard to examining mediation, which is a process over time that arguably would demand at least three measurement points (Preacher, Citation2015). However, given that our predictor age is a demographic, we argue that two measurement points are sufficient in our case, especially since age is not self-report but a register variable. Also, because of the used nonexperimental design, the results do not hold for drawing strong conclusions about directions of relations. Neither does the used model take baseline levels of stress and inefficient leadership into account, to test for change over time or reversed relations between variables. However, the use of autoregressors or a cross-lagged model has been criticized (i.e. especially in two-wave designs) in recent literature as the potential of spurious relations is high (Lucas, Citation2023). Indicating that they are less fitting for establishing existing casual relationships.

Third, the response rates indicate that there is a potential risk for selection bias, which limits the generalizability of the results (ref). As presented in the method section, the used panel sample is, compared to the managerial workforce in Sweden, somewhat of older age, of female gender, of higher education, working in public organizations, and born in Sweden. The response rate is within the range of what can be expected in workforce population studies (Statistics Sweden, Citation2023). However, future research may consider using alternative complementary study designs and, when possible, design the data collection in accordance with recommendations (e.g. short questionnaires and offer rewards when possible; Guo et al., Citation2016)

Fourth, from a contextual perspective, we only tested two aspects of social support as a control and moderators. Neither of these social support variables acted as a buffer the age-stress-inefficient leadership relations, however, this does not mean that there are other important context factors that may, nor that these factors are non-influential in all circumstances. For example, a recent study showed that role clarity as an element of the (task) context, rather than social context, explained variance in younger versus older managers display of an effective leadership (Tafvelin et al., Citation2023). In other words, given the multitude of potential influential contextual actors for the leadership process (Oc, Citation2018), our study only offers a limited testing of the contextual model suggested in previous studies (e.g. Scheibe et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, organizational factors such as gender distribution, the size of the organization, and managerial position, could also be expected to influence managers’ leadership behaviors. Such organizational contextual factors could also influence managers’ expectancies, and their organizations potential for delivery (i.e. due to size), of social support (Johns, Citation2024; Oc, Citation2018). In the present study we did not have the data to estimate or control for these or other organizational contextual factors. As such, we suggest that future studies strive to include more aspects of context to examine the interplay of these factors. For example, this could help explain the circumstances for when social support is influential for buffering the relation between perceived stress and inefficient leadership.

Conclusion

Our study indicates that young managers are more prone to self-report inefficient leadership behaviors compared to their older colleagues, and that this relation could be explained by their experience of stress. Our findings contribute to the growing field of a lifespan perspective on leadership, which suggest that leadership research need to take managers age into account to fully understand leadership processes. We propose that future research continue to explore how organizations can adapt and support young individuals entering managerial roles to ensure a sustainable working life for managers regardless of age.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority [2019-02119].

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Given restrictions from the Swedish ethical review authority, the data cannot be made freely available. Access to the data may thus only be provided to other researchers after consultation with the corresponding author and if these requests are reasonable and in line with Swedish law.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robert Lundmark

Robert Lundmark is an Associate Professor in Work and Organizational Psychology at Umeå University. His research is focused on leadership and organizational interventions.

Hanna Irehill

Hanna Irehill is a PhD student at the Department of Psychology, Umeå University. Her PhD project focuses on young managers in the private sector.

Susanne Tafvelin

Susanne Tafvelin is an Associate Professor in Work and Organizational Psychology at Umeå University. Her research is focused on leadership, leadership training, and employee wellbeing.

References

- Agarwal, B., Brooks, S. K., & Greenberg, N. (2020). The role of peer support in managing occupational stress: A qualitative study of the sustaining resilience at work intervention. Workplace Health & Safety, 68(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079919873934

- Arnold, K. A., Connelly, C. E., Walsh, M. M., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2015). Leadership styles, emotion regulation, and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039045

- Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 611–626. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611

- Barbuto, J. E., Fritz, S. M., Matkin, G. S., & Marx, D. B. (2007). Effects of gender, education, and age upon leaders’ use of influence tactics and full range leadership behaviors. Sex Roles, 56(1-2), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9152-6

- Benjamin, B., & O’reilly, C. (2011). Becoming a leader: Early career challenges faced by MBA graduates. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(3), 452–472. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2011.0002

- Berthelsen, H., Westerlund, H., & Søndergård Kristensen, T. (2014). COP SOQ II: en uppdatering och språklig validering av den svenska versionen av en enkät för kartläggning av den psykosociala arbetsmiljön på arbetsplatser. Stockholm: Stressforskningsinstitutet.

- Buengeler, C., Homan, A. C., & Voelpel, S. C. (2016). The challenge of being a young manager: The effects of contingent reward and participative leadership on team-level turnover depend on leader age. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(8), 1224–1245. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2101

- Byrne, A., Dionisi, A. M., Barling, J., Akers, A., Robertson, J., Lys, R., … & Dupré, K. (2014). The depleted leader: The influence of leaders’ diminished psychological resources on leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(2), 344–357.

- Eagly, A. H., & Johnson, B. T. (1990). Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 233–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.233

- Edelman, P. J., & Van Knippenberg, D. (2017). Training leader emotion regulation and leadership effectiveness. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(6), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9471-8

- Guo, Y., Kopec, J. A., Cibere, J., Li, L. C., & Goldsmith, C. H. (2016). Population survey features and response rates: A randomized experiment. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1422–1426. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303198

- Gyllensten, K., & Palmer, S. (2005). The role of gender in workplace stress: A critical literature review. Health Education Journal, 64(3), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/001789690506400307

- Harms, P. D., Credé, M., Tynan, M., Leon, M., & Jeung, W. (2017). Leadership and stress: A meta-analytic review. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.10.006

- Haver, A., Akerjordet, K., & Furunes, T. (2013). Emotion regulation and its implications for leadership: An integrative review and future research agenda. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(3), 287–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051813485438

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

- Hobfoll, S. E., Freedy, J., Lane, C., & Geller, P. (1990). Conservation of social resources: Social support resource theory. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(4), 465–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407590074004

- Irehill, H., Lundmark, R., & Tafvelin, S. (2023). The well-being of young leaders: Demands and resources from a lifespan perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1187936. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1187936

- Johns, G. (2024). The context deficit in leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 35(1), 101755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2023.101755

- Jolly, P. M., Kong, D. T., & Kim, K. Y. (2021). Social support at work: An integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(2), 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2485

- Kaluza, A. J., Boer, D., Buengeler, C., & van Dick, R. (2020). Leadership behaviour and leader self-reported well-being: A review, integration and meta-analytic examination. Work & Stress, 34(1), 34–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1617369

- Kim, N., & Kang, S. W. (2017). Older and more engaged: The mediating role of age‐linked resources on work engagement. Human Resource Management, 56(5), 731–746. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21802

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). Guilford publications.

- Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554

- Larsson, G., & Björklund, C. (2021). Age and leadership: Comparisons of age groups in different kinds of work environment. Management Research Review, 44(5), 661–676. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-01-2020-0040

- Larsson, G., Brandebo, M. F., & Nilsson, S. (2012). Destrudo‐L: Development of a short scale designed to measure destructive leadership behaviours in a military context. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 33(4), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437731211229313

- Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press.

- Lucas, R. E. (2023). Why the cross-lagged panel model is almost never the right choice. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 6(1), 25152459231158378. https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459231158378

- Lundmark, R., Stenling, A., von Thiele Schwarz, U., & Tafvelin, S. (2021). Appetite for Destruction: A Psychometric Examination and Prevalence Estimation of Destructive Leadership in Sweden. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 668838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.668838

- Mead, S., Hilton, D., & Curtis, L. (2001). Peer support: A theoretical perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095032

- Mikkelsen, M. B., O’Toole, M. S., Elkjaer, E., & Mehlsen, M. (2023). The effect of age on emotion regulation patterns in daily life: Findings from an experience sampling study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 65(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12970

- Milner, J., McCarthy, G., & Milner, T. (2018). Training for the coaching leader: How organizations can support managers. Journal of Management Development, 37(2), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-04-2017-0135

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Oc, B. (2018). Contextual leadership: A systematic review of how contextual factors shape leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.004

- Oshagbemi, T. (2004). Age influences on the leadership styles and behaviour of managers. Employee Relations, 26(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450410506878

- Pejtersen, J. H., Kristensen, T. S., Borg, V., & Bjorner, J. B. (2010). The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(3_suppl), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494809349858

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Preacher, K. J. (2015). Advances in mediation analysis: A survey and synthesis of new developments. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 825–852. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015258

- Reed, A. E., & Carstensen, L. L. (2012). The theory behind the age-related positivity effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 339. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00339

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

- Rosing, K., & Jungmann, F. (2019). Lifespan perspectives on leadership. In Work across the lifespan (pp. 515–532). Academic Press.

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

- Scheibe, S., & Zacher, H. (2013). A lifespan perspective on emotion regulation, stress, and well-being in the workplace. In The role of emotion and emotion regulation in job stress and well being (pp. 163–193). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Scheibe, S., Walter, F., & Zhan, Y. (2021). Age and emotions in organizations: Main, moderating, and context-specific effects. Work, Aging and Retirement, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waaa030

- Schilling, J. (2009). From ineffectiveness to destruction: A qualitative study on the meaning of negative leadership. Leadership, 5(1), 102–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715008098312

- Siu, O-l., Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., & Donald, I. (2001). Age differences in coping and locus of control: A study of managerial stress in Hong Kong. Psychology and Aging, 16(4), 707–710. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.16.4.707

- Skogstad, A., Hetland, J., Glasø, L., & Einarsen, S. (2014). Is avoidant leadership a root cause of subordinate stress? Longitudinal relationships between laissez-faire leadership and role ambiguity. Work & stress, 28(4), 323–341.

- Statistics Sweden. (2023). Kvalitetsdeklaration Arbetskrafts undersökningarna (AKU) [Quality declaration of Workforce surveys]. https://www.scb.se/contentassets/c12fd0d28d604529b2b4ffc2eb742fbe/am0401_kd_2023_230210.pdf

- Tafvelin, S., Irehill, H., & Lundmark, R. (2023). Are young leaders more sensitive to contextual influences? A lifespan perspective on organizational antecedents of transformational leadership. Nordic Psychology., 1–17.

- Thompson, P. S., Bergeron, D. M., & Bolino, M. C. (2020). No obligation? How gender influences the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1338–1350. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000481

- Tulgan, B. (2011). Generation Y: All grown up and now emerging as new leaders. Journal of Leadership Studies, 5(3), 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.20237

- Uen, J., Wu, T., & Huang, H. (2009). Young managers’ interpersonal stress and its relationship to management development practices: An exploratory study. International Journal of Training and Development, 13(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2419.2008.00314.x

- Walter, F., & Scheibe, S. (2013). A literature review and emotion-based model of age and leadership: New directions for the trait approach. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(6), 882–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.10.003

- Wikhamn, W., & T., Hall, A. (2014). Accountability and satisfaction: Organizational support as a moderator. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(5), 458–471. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-07-2011-0022

- Zacher, H., Clark, M., Anderson, E. C., & Ayoko, O. B. (2015). A lifespan perspective on leadership. In B. P. Matthils, D. T. A. M. Kooij, & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), Aging workers and the employee-employer relationship (pp. 87–104). Springer.

- Zacher, H., Rosing, K., & Frese, M. (2011). Age and leadership: The moderating role of legacy beliefs. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.006