Abstract

Contemporary materialism/consumerism emphasizes excessive spending to own the latest and greatest products. Maintaining an appearance of wealth is economically unfeasible for most. Materialism can generate beliefs of insufficient funds and inadequacy to afford goods. Materialism is the possession of goods for happiness, centrality, and success. Material goods become a focus to someone’s life to signal well-being. Financial scarcity theory explains people believe they are constantly behind or unable to pay for their needs. These individuals will perform tradeoffs to fulfill needs. Perceived lack of finances drives consumers to buy goods that fill perceived deficiencies. Path analysis demonstrated financial scarcity related to higher materialism. Higher financial scarcity related to lower household income and thereby higher materialism. Higher financial scarcity related to higher impression management and thereby higher materialism. These results indicated the possession of goods can artificially inflate someone’s socioeconomic status to compensate for self-perceived paucity.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

A scarcity mindset is when someone experiences limitations by their resources and has a small-minded outlook in what is possible (Cannon et al., Citation2019; Goldsmith et al., Citation2021; Mani et al., Citation2013; Meuris & Leana, Citation2015). For example, someone with just twenty dollars for groceries the remainder of the month is counting their cents to afford their next meal. They are not looking for costly new products; they are focused on meeting basic psychological needs. By contrast, someone with an abundance mindset may have a series of vacations abroad in the upcoming months. Traveling is an experiential opportunity with the potential for new forms of income (e.g., creating new products to sell) even if it accrues debt. Priorities shift beyond someone’s immediate space, finances, and purview to a wider gamut of possibilities. It is possible for individuals to experience different mental states of scarcity: social (i.e. void of connections to others) (Kalil et al., Citation2023), cognitive (i.e. mental fatigue) (Veltri & Ivchenko, Citation2017), time (Shah et al., Citation2018), resource (i.e. supplies) (Huijsmans et al., Citation2019), and financial (i.e. insufficient funds to expenses) (Mullainathan & Shafir, Citation2013). Materialism is the possession and attachment to goods as a central purpose in life (Kasser, Citation2003; Pandelaere, Citation2016). Material goods can create a façade of financial well-being that portrays to others financial abundance (i.e. subjective financial well-being) compared to household income/savings (i.e. objective financial well-being) (Biswas-Diener, Citation2008; Yurchisin & Johnson, Citation2004). This project focuses on deepening our understanding of the financial scarcity mindset and the pursuit of material goods to alleviate perceived financial concerns.

With modern advancements in technology and distribution, most of the industrialized world has access to affordable necessities (e.g. food and clothing) that can be delivered to someone’s residence with a click of a button (Dickson, Citation2000; Ghosh, Citation1998). Consumers often have more than what they need. In fact, consumer market demand for global personal luxury (e.g. cosmetics, watches, handbags, perfumes, and jewelry) exceeded $256 billion in 2020 (Loranger & Roeraas, Citation2023). Why are consumers spending beyond their means when their basic needs are met? Why do consumers participate in excessive shopping for goods soon forgotten after purchasing? Advertisements and social comparison has fostered a culture of materialism (Zukin & Maguire, Citation2004). This creates a sense of inadequacy in self-worth because of the endless supply of new goods someone could desire (Kasser, Citation2003). So, while someone can earn enough income to survive in modern society, someone can still live with a financial scarcity mindset concerned they will not be able to afford their expenses (De Bruijn & Antonides, Citation2022). De Bruijn and Antonides (Citation2022) found people from both low and high income to experience or not experience financial scarcity. Income is not an immediate indicator for having a financial scarcity mindset. Financial scarcity is a psychological state of mind. This sense of paucity is not just the lack of savings in a bank account. It is also perceived financial well-being from others. For instance, at a speakeasy bar with several friends, if someone pays for a round of drinks, it gives the impression that someone is financially well-off with the ability to pay for others. Even if it stacks on someone’s existing debt, socially it portrays financial well-being. In that moment, it can create an illusion of financial abundance that temporarily alleviates a perceived lack of self-worth. Unfortunately, past experiences of financial ruin and poverty can last beyond an immediate moment. Some individuals can pursue a lifetime of accruing wealth to try to avoid feelings of being without or poverty. A financial scarcity mindset considers someone’s current economic status and social appearances when making decisions. At present, financial scarcity on materialism antecedents warrant quantitative investigation. Therefore, the project’s purpose was to study the effects of financial scarcity on materialism with mediators: household income and impression management.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Financial scarcity theory and social status

The theory of financial scarcity posits when someone lacks the resources to cover necessities they will apply cognitive resources to find alternative ways to fulfill them (Mullainathan & Shafir, Citation2013). A financial scarcity mindset is one’s appraisal of their subjective financial situation (Hilbert et al., Citation2022a). This financial appraisal evokes neglect and narrowing of attention on a given pertinent situation (Shah et al., Citation2012). For example, someone struggling to pay for this week’s groceries has a narrow focus on their next trip to the store and will neglect next month’s rent in the meantime. Financial stress relating to social status and perceived lower ranking can have negative health outcomes (e.g. coronary heart disease) (Cundiff et al., Citation2020). The purpose of this project expands on financial scarcity theory and the pursuit of material goods to fill the sense of lacking sufficient funds.

Materialism and the possession of goods for social value

Materialism/consumerism is the excessive attachment to material possessions (Abela, Citation2006; Ahuvia & Wong, Citation2002; Inglehart, Citation2015). Consumers invest both economic and psychological resources in possessions to gain satisfaction beyond a product’s basic utilitarian function. Media, advertising, and culture have shaped modern consumerism (Zukin & Maguire, Citation2004). Media generally portrays more affluence and materialism than real life, which becomes internalized by viewers (Shrum et al., Citation2004). Materialism includes the hedonistic spirit of overspending to fulfill illusionary new needs (Ritzer, Citation2005, p. 60). For example, spending a fortune on a newly released wristwatch (when someone owns a dozen) is a false need even if the shopper says, ‘I need to buy it’. Ritzer (Citation2005) explains materialistic societies will have a perpetuating cycle of new products consumers believe they need. Consumers participate in this excessive spending for external and internal reasons. For example, fitting into a community/tribe is a form of external social validation (Cova, Citation1997). Meanwhile, purchasing because someone can afford it to add to their personal collection is an internal reason (Kasser & Ryan, Citation1996). Many consumers will purchase goods to symbolize high income status (Hampson et al., Citation2021; Tay et al., Citation2018).

Materialism is the possession of goods as a representation of someone’s success, happiness, and centrality (Richins & Dawson, Citation1992; Watson & Howell, Citation2023). Success represents their ability to afford goods (e.g., financially well-off to own a house). Happiness means buying goods brings joy for someone. Centrality means the possession of goods (e.g. luxury goods) is a meaningful part of their lives. A person that values materialism as a central part of their lives will spend money to live a certain lifestyle that gives them a sense of purpose. For instance, a person may surround themselves with gold objects to live with a grand sense of nobility. Money spent on objects represents someone’s values and can portray financial status or identity to others (Pandelaere, Citation2016; Shrum et al., Citation2013). A study among children found peer culture and pressure to relate to higher materialism (Banerjee & Dittmar, Citation2008). Social approval from others, extrinsically rewards money spent on visible possessions (Kasser & Ryan, Citation1996). Materialistic consumers tend to be status-driven and make social comparisons to display wealth (Martins, Citation2003; Richins & Dawson, Citation1992). Social approval from others and ownership of goods can create a façade of abundance but social capital based on consumer values. For example, flying first class and staying at an airport lounge associates someone with high society that peers value. Thereby, we posited those with a financial scarcity mindset will place greater value on possessions to compensate for internal perceptions of having a lower financial state of well-being.

H1: A higher financial scarcity mindset will positively relate to higher materialism.

Prior research discussed the possibility that ‘lower levels of well-being cause people to be materialistic (failing to find inner sources of happiness, they may turn to external gratification)’ (Van Boven, Citation2005, p. 133). Material objects portray outward appearances of subjective financial well-being (e.g., owning a luxury car that makes someone feel a part of high society) even though such possessions drain someone’s objective financial well-being (e.g. household income/savings). Related research found approximately half of participants with a lower annual income (<$35K) indicated experiential and materialistic purchases made them happier (e.g. appliances like washing machines) (Van Boven & Gilovich, Citation2003). Whereas participants with higher annual income (>$35K) more likely indicated experiential purchases made them happier. For those with less discretionary income, possessions are an important source of happiness. Possessions fill contemporary needs and signal financial well-being to others (Nanda & Banerjee, Citation2021).

Socioeconomic status and signaling wealth through possessions

A financial scarcity mindset narrows focus on impending bills (Mullainathan & Shafir, Citation2013; Zhao & Tomm, Citation2018). Eye tracking research found individuals randomly assigned to a limited budget condition to focus more on menu prices compared to those with a large budget (Tomm et al., Citation2016). This narrowing of focus on finances neglects foresight on long-term goals that could meaningfully improve someone’s financial status (Berg, Citation2015). For example, it takes substantial effort, time, risk, and money, to change someone’s career and thereby elevate someone’s income. Many professions like accounting or marketing management often require advanced degrees, training, and resume building to qualify for positions. Meanwhile, financial scarcity requires some immediacy to make more money. In fact, Zhao and Tomm (Citation2018) argued, financial scarcity results in counterproductive behaviors to resolve immediate financial demands. For example, it is rare for ‘get rich quick’ tactics to lead to long-term steady income (e.g. winning the lottery and gambling). It is possible for someone lacking funds to do more of the same work such as taking on additional shifts (e.g. restaurant server working overtime). However, this will not necessarily lead to a substantial bracket increase in socioeconomic status (e.g. movement from $30,000 into the $50,000 annual income range). It is hard without loans or financial capital to generate more income. Investing in someone’s education or starting a new business requires capital. Thereby, a financial scarcity mindset will likely associate with lower household income because there is a lack of financial resources for bold multiyear career advancement.

Moreover, a scarcity mindset is a liability of poorness (Morris et al., Citation2022). Morris et al. (Citation2022) overviewed liabilities of poorness that complicate low-income individuals from entrepreneurship (i.e. a method of societal contribution and generating more income). Literacy gaps (e.g. reading, and writing numeracy), intense personal pressures (e.g. food insecurity and health problems), lack of safety net (no savings, few assets, and no health coverage) and a scarcity mindset (e.g. reactive versus proactive, decisions as tradeoffs/compromises, short-term orientation, and avoiding long-term commitments) are common barriers low-income individuals face. This hinders someone’s ability to take risks like business ventures or long-term investments (e.g. higher education/purchase a home) that have greater odds of producing long-term financial gains.

Effective branding and advertising over time has influenced consumers to believe goods can elevate someone’s socioeconomic status by association (e.g. jewelry signaling success) (Bastos & Levy, Citation2012; De Mooij & Hofstede, Citation2010). The purchase of an expensive product and its gratification is swift compared to long-term career development. It is easier to make a purchase and obtain the sense of wealth by holding a designer product, compared to the daily painful challenges of long-term planning, learning, and work without certainty of a payoff. For example, it is recreational to visit a boutique on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hill, California to purchase a designer bag, compared to years of studying and thousands of dollars to become a human resource manager. Material goods can psychologically supplement needs for achievement with social reinforcement and perceived value from goods (Ed Diener & Biswas-Diener, Citation2002). For instance, western societies favor car ownership as an indicator of success and acceptance into groups. Friends frown upon friends that often request rides that add 30–60 min to their commute home. Costs, like time and gas shift, to car owners that burden friendships. Ownership of possessions are socially reinforced and can produce social capital.

Research analysis of longitudinal data with 14,790 participants demonstrated financial scarcity strongly related to low income and thereby psychological health problems (Sommet et al., Citation2018). The researchers found low income by itself was not a clear predictor of unhappiness or psychological health problems in their two studies. It was the presence of a financial scarcity mindset that contributed to an individual’s sense of lacking or being without. Financial scarcity mindset elevates to the forefront of their cognition their socioeconomic status and related worries. It is similar to ruminating on a problem which causes stress constantly thinking about it. For example, pay volatility, such as gig work and reliance on service tips, can induce a state of financial scarcity (Sayre, Citation2022). Individuals in this mindset ruminate and shift cognitive resources to earn more money. Sayre (Citation2022) found financial scarcity to prompt physical symptoms and negatively impact sleep. Materials goods can divert attention away from thinking about lacking finances and low socioeconomic standing.

H2: Household income will mediate the relationship between financial scarcity and materialism, wherein financial scarcity will indirectly relate to lower household income.

Someone’s socioeconomic status comes with different lived experiences, influenced by their environment (Atkinson, Citation2021). Over time, this shapes an individuals’ attitudes, perspectives, and values. For instance, persons from lower socioeconomic status spend a larger proportion of their income on necessities like food, transportation, and housing (Hill, Citation2001; Richards, Citation1965). A study of Latin American consumers found below average socioeconomic households spent 50–75% on consumer products and those in the lowest income bracket spent nearly all money on consumer products (e.g. groceries) (D’Andrea et al. Citation2006). Financial scarcity and the iterative habits shape the beliefs of a socioeconomic class (McDonough & Calderone, Citation2006). Our study examines the relationship between financial scarcity with household income on the pursuit of material goods.

In the digital era, there is high online advertisement viewership that has shaped our subjective financial well-being. Researchers reported Americans are exposed to an average of $500 in online advertisements each year (e.g. sidebar and banner ads) (Lewis et al., Citation2015). Ubiquitous marketing and advertising have created a culture of consumerism (Abela, Citation2006). With continuous advertising, materialistic beliefs became more commonplace in modern society. For instance, successful vacuum cleaning advertisements implied they reduced cleanup time so parents can spend more time with their children. Society learned household products, like vacuums, can solve everyday problems and improve quality of life. With the absence of greater objective financial well-being (e.g. income/savings) advertisements have shifted consumers to believe possessions is comparable wealth (Biswas-Diener, Citation2008). For example, luxury brands/goods help individuals feel upper-class when the ability to greatly change someone’s socio-economic status is unlikely or a challenging endeavor (Han et al., Citation2010). This research indicates the commonality of these beliefs in modern society and the importance of studying antecedents to materialism.

Materialism is the preoccupation of valuing possessions and the social image they portray (Bauer et al., Citation2012). Purchasing and owning impressive belongings fills a sense of self-worth based on this social construct. For example, owning a Harley–Davidson motorcycle allows entrance and acceptance into a community that reinforces a set of beliefs (Schembri, Citation2009). Appearance (e.g. black leather jackets) and bike modifications (e.g. Screaming Eagle pipes) are some unifying values. Owning certain goods signals to others status and success. It is similar to an outward expression of how financially well-off someone is without stating how much is in their bank account. Material goods can compensate for someone’s low socioeconomic status to create a perception of greater personal wealth. Social connections reinforce the value of these material purchases.

H3: Household income, as a mediator, will indirectly relate to higher materialism.

Moreover, the pursuit of money and financial well-being is a major motivator in modern society (Drever et al., Citation2015; Shim et al., Citation2009). The amount of money and ability to pay for goods consistently over time is valued in society. For example, someone’s career is often associated with financial status and the quality of life they are perceived to have. Compare first impressions meeting a janitor versus a medical doctor and most will assume the medical doctor has it made in life. Meanwhile, someone who is temporarily out of work because of layoffs would be considered in a dire financial state because of the lack of funds to pay monthly bills. Those in a state of financial scarcity are more cognizant of present finances and their implications (Kalil et al., Citation2023; Mullainathan & Shafir, Citation2013). For instance, of a $200 paycheck needed to last the next two weeks, someone will likely care about every cent that goes to pay for their next meal.

Impression management with materials goods

Living on the edge of not being able to afford basic needs has social consequences (Rank, Citation1994). For example, borrowing from a friend and not paying them back can result in the souring of a friendship. Appearing financially well-off with material goods can create a façade that fills a lack of self-worth (Dittmar, Citation2007). It is socially reinforced by positive feedback or acceptance from others. For instance, one friend able to drive their group of friends around without cars, builds social capital. This translates into invitations, positive praise, and inclusion. Certain material goods, like a car, can compensate for a lack of funds when used to garner social connections and benefits. Importantly, social connections require effort to maintain. Impression management attempts to maintain perceptions of showing care, positivity, and involvement (e.g. social cause, community participation). Researchers found materialism to associate with greater status-seeking impression management on social media (Tuominen et al., Citation2022). For example, the purchase and posting of luxury goods/unique experiences on social can increase someone’s perceived status. Symbolic possessions are used to impress others over direct behaviors that someone may lack the skills/practice in doing. This impression management ideally translates into ongoing social connection and social capital.

Impression management is the attempt to shape how others view an individual (Goffman, Citation2016; Tedeschi, Citation2013). Researchers explain two components of impression management (1) motivation to control what others think of them and (2) construction of an ideal image (Leary & Kowalski, Citation1990). For example, some individuals will buy a home in a gentry neighborhood they can barely afford. By living in such a neighborhood, they hope to have greater success and well-being associated to the area (Higley, Citation1995, p. 127). There is a misbelief that external objects (e.g. clothes and housing) can independently improve someone’s social standing (Dittmar et al., Citation1996; Yurchisin & Johnson, Citation2004). A positive social image is fleeting. It is also an internal response to someone’s social environment often evaluated in comparison to others. For instance, even if someone buys the latest and greatest objects of today, tomorrow there will be something new others find more valuable. It becomes an endless struggle to appear well-off when the market is constantly changing to promote shopping. It becomes a struggle of never being good enough despite excessive working and spending to shape the opinions of others who can dismiss someone’s status with one judgmental comment (e.g. ‘That was so yesterday’).

H4: Impression management will mediate the relationship between financial scarcity and materialism, wherein financial scarcity will indirectly relate to higher impression management.

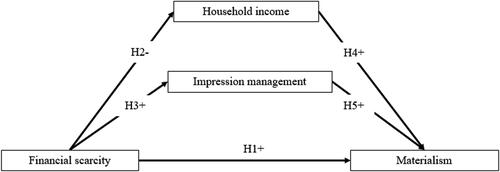

In modern consumeristic society, living in poverty has negative stigmas (Kluegel & Smith, Citation2017; Williams, Citation2009). It implies having to work multiple jobs to pay off excessive debt. It implies not having the funds to experience a night out with friends. It implies living in impoverished parts of town that lack opportunities (e.g. underfunded schools and low paying jobs). Perceived stigma of poverty was found to be internalized and associated with greater levels of depression (Mickelson & Williams, Citation2008). Financial scarcity mindset is a psychological state of feeling impoverished (De Bruijn & Antonides, Citation2022). The negative stigmas of financial scarcity and poverty can drive individuals to reshape how others view them (Piff et al., Citation2018). By possessing high-end brands and more material objects, it attempts to obtain positive affiliations to high society even though someone’s fundamental human self-worth remains the same (Kraus et al., Citation2012). For example, people in high society can afford expensive resort vacations and hire help for menial tasks. Impression management through owning material goods uses possessions to symbolize wealth and abundance as an outward expression of someone’s identity (Belk, Citation1988). In other words, individuals attempt to use material goods to dispel perceived low economic status and increase their sense of self-worth. shows the hypothesized model of relationships between a financial scarcity mindset on materialism.

Figure 1. Hypothesized parallel mediation effects on materialism.

H5: Impression management, as a mediator, will indirectly relate to higher materialism.

Prior research has studied how poverty-related ‘concerns impair cognitive capacity’ and expend mental resources to address immediate concerns (Vohs, Citation2013). Vohs (Citation2013) implied this short-term view and depletion of cognitive resources can promote unhealthy impulsive behaviors. Feelings of incompetence, self-doubt, and personal inadequacy are sources for compulsive behaviors (e.g. chronic and repetitive purchasing) (Brister & Brister, Citation1987). In times of distress many consumers will turn to material goods to reduce anxiety and experience a sense of self-control (Hirschman, Citation1992). Material goods, like vehicles, are often an extension of someone’s identity (Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2011). Possessions can be a physical (e.g. fishing casting net) or symbolic (e.g. t-shirt with political message) extensions of oneself (Belk, Citation1988). Possessions act as external signals of someone’s ideologies (e.g. social morals) and personal identifying characteristics (e.g. occupation). People use possessions to shape the opinions of others, such as signaling financial well-being. For example, accessorizing with extravagant gold jewelry has royal and lavish lifestyle affiliations. Therefore, purchasing material goods to portray economic status can alleviate thoughts and appearances of indebtedness.

Method

Overview of study and participants

The participant data collection platform, CloudResearch, was utilized to collect survey data (Douglas et al., Citation2023). CloudResearch data quality research was found to have satisfactory attention, honesty, comprehension, and reliability among participants (Peer et al., Citation2022). Participants agreed to the consent form, answered demographic questions, and responded to survey questions. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available. The convenience sample represented the demographic diversity of the United States acceptable to conduct generalizable research (see ) (Coppock & McClellan, Citation2019; Levay et al., Citation2016). The researchers utilized recommended data quality procedures (Buhrmester et al., Citation2016). Nine hundred seven participants initially completed the survey. Sixteen did not complete the survey. Nine did not pass attention checks (e.g. selection of answer choice embedded in section). Attention checks reduce the potential for careless responses (Ward et al., Citation2017). The researchers performed analysis on the remaining participants (N = 882). Online survey collection provides the ability to assess for fully completed surveys and add requirements to complete all questions in a section (Ebert et al., Citation2018). A large diverse sample reduces the potential for online survey collection by better representing the general population (Ball, Citation2019; Terhanian et al., Citation2016). The study had 49.3% male participation. The median household income was between $60,000 and $69,999 (USD). The median household size was three individuals. The study had 48.6% of participants self-reporting homeownership.

Table 1. Demographic frequencies and percentages.

Path analysis measures

Independent variable

The psychological inventory of financial scarcity (PIFS) scale was utilized to measure a participants’ level of perceived financial scarcity (i.e. self-perception of inadequate money to buy needs) (Van Dijk et al., Citation2022). The scale is composed of 12-items on a 7-point scale from 1–Strongly disagree to 7–Strongly agree (e.g. ‘I often don’t have money to pay for the things that I really need’) (α=.93). The measure was used as a validated measure for self-evaluating a participant’s sense of financial scarcity in their real lives (Hilbert et al., Citation2022b).

Mediator variables

Impression management from the Hogan Personality Inventory (HPI) measured an individual’s level of contemplation of how others view them (Hogan & Hogan, Citation1992). The variable was composed of 6-items (e.g. ‘Withhold information from others’ and ‘Am preoccupied with myself’) (α=.68). Subsequent research of impression management exhibited predictive validity with social skills (Prewett et al., Citation2013).

Household income was self-reported annual earnings in U.S. dollars. Participants responded to the prompt ‘What is your household income?’ and selected their income range from eleven bracketed levels (1–Less than $10,000, 2–$10,000–19,999, to 11–$100,000+). This followed a standard ordinal probit method to impute as a continuous variable (Bhat, Citation1994; Stern, Citation1991). Household income is a measure of someone’s objective financial well-being.

Dependent variable

Materialism measured an individual’s value in possessions as a sign of someone’s success, centrality, and happiness using 9-items (α=.81) (Richins, Citation2004). Example items from the three components include the following: 1) success–’The things I own say a lot about how well I’m doing in life’, 2) centrality–’I like a lot of luxury in life’, and 3) happiness–’I’d be happier if I could afford to buy more things’. Subsequent research demonstrated predictive validity of materialism positively relating to conspicuous online consumption (Anggarawati et al., Citation2023) and lower income sufficiency evaluations (Castro & Bleys, Citation2023).

Succinct measures with good reliability scores can measure constructs and reduce the downsides of lengthy questionnaires associated to survey fatigue (Donnellan et al., Citation2006; Schmidt et al., Citation2003).

Control variables

Path analysis included gender, household size, and homeownership as covariates. There was dummy coding of gender (female=2 and male=1) and homeownership (homeowner=1, renter/other=0). Household size was included to account for potential differences when additional family members in one home can alter spending priorities (He & Jia, Citation2024). For example, children and older adults in larger households could shift priorities to physiological needs, opposed to single households that value status purchases to impress potential future partners. Homeownership was studied as a potential status symbol and including this measure allowed for this variable’s analysis (Garðarsdóttir & Dittmar, Citation2012).

Results

Path analysis results

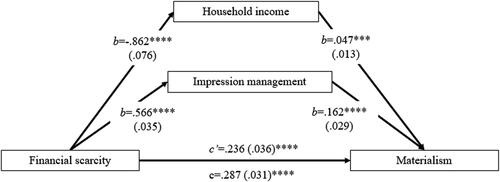

displays descriptive statistics and variable correlations. Correlational results between variables demonstrated appropriate discriminant validity (Cheung et al., Citation2023). Skewness (within ± 2.0) and kurtosis (within ± 7.0) values demonstrated being within moderate normality thresholds (Kline, Citation2015; Wong, Citation2016). SPSS PROCESS Macro V3.5 (model 4) with the 10,000 bootstrapped sampling procedure was used to conduct parallel mediation analysis (Hayes, Citation2012; Citation2017; Kane & Ashbaugh, Citation2017; Preacher & Hayes, Citation2004) (see and ). VIF (variance inflation factor) values indicated acceptable moderate variable correlation when regressed on materialism (Miles, Citation2014). We considered results statistically significant, when zero was not between the 95% upper and lower bound confidence intervals. Analysis of model fit utilizing SPSS AMOS V25 showed good fit based on recommended to report indexes and cutoff points for large sample sizes (greater than 200 participants) (χ2/df = 4.079, p<.0001, RMSEA=.059 (<.06), SRMR=.030 (<.80), CFI=.969) (Hooper et al., Citation2008; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; MacCallum et al., Citation1996). There was a direct positive relationship between financial scarcity to higher materialism [b=.232, t = 6.429, SE=.036, p<.0001 (LLCI .1614 ULCI .3033)] (support for H1). Financial scarcity related to lower household income [b=-.850, t=-11.166, SE=.076, p<.0001 (LLCI -.9997 ULCI -.7008) (support for H2). Household income related to higher materialism [b=.047, t = 3.481, SE=.013, p<.001 (LLCI .0202 ULCI .0723) (support for H3). Financial scarcity related to higher impression management [b=.566 t = 15.983, SE=.035, p<.0001 (LLCI .4965 ULCI .6355) (support for H4). Impression management related to higher materialism [b=.162, t = 5.654, SE=.029, p<.0001 (LLCI .1054 ULCI .2176) (support for H5). The statistically significant direct path of financial scarcity on materialism with simultaneous significant indirect paths indicates partial mediation (Hayes, Citation2018). Additionally, homeownership, as a covariate, positively associated with higher household income (b = 1.425, t = 7.552, SE=.189, p<.0001), but did not significantly relate to impression management and materialism.

Figure 2. Hypothesized parallel mediation effects on materialism.

Notes: Covariates included gender, household size, and homeownership.

*p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001, ****p<.0001.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and cross-level correlations.

Table 3. Parallel mediation modeled effects of financial scarcity on materialism.

Discussion

General discussion

Within the context of financial scarcity theory, results showed financial scarcity related to higher materialism. This expands on the Cundiff et al. (Citation2020) framework of social status, financial stress, and negative physical health implications. Results evinced material objects can fill psychological disparities in perceived social status. Material goods can signal to others success and happiness to cope with internal perceptions of inferiority. For example, owning a new BMW car, despite not being able to afford it, can generate the social appearance of financial well-being. Touting material goods can artificially inflate someone’s social status through feedback and acceptance by others (Matt, Citation2003). Possessions can augment someone’s identity into a higher socioeconomic status by association to goods that symbolize wealth (Davidson, Citation2008). These findings contribute to our understanding of financial scarcity theory and how consumers attempt to address perceived inadequacies.

Moreover, household income mediated financial scarcity on materialism. Financial scarcity related to lower household income and thereby positively related to higher materialism. This implies a financial scarcity mindset can deter earning more income, which buttress prior research (Sommet et al., Citation2018). It takes investments to generate more income (e.g. spending thousands of dollars to earn a college degree). If someone believes they cannot afford to spend more, long-term investments are out of their purview. A scarcity mindset narrows someone’s focus on more immediate needs which can undermine their ability to earn more income in the long-term. Mediation results also indicates lower socioeconomic status can drive an individuals’ pursuit for possessions to fill self-perceptions of financial deficiency. For example, researchers have found consumers of lower economic status to prefer branded luxury goods with conspicuous (‘loud’) brand logos to signal status versus those of higher socioeconomic status that prefer inconspicuous (‘quiet’) branding (Han et al., Citation2010). Material goods can embellish someone’s finances as a façade to their actual financial well-being. This provides support for the effects of purchasing material goods to improve someone’s subjective well-being.

Additionally, impression management mediated financial scarcity on materialism. Financial scarcity related to higher impression management. Impression management positively related to higher materialism. This demonstrated social acceptance motivates individuals to buy goods to improve someone’s perceived social standing. This buttress attempts to gain social capital by using materialism goods to shape others’ opinions (Tuominen et al., Citation2022). Social capital is a valued currency in society. Positive opinions of individuals can translate into workplace promotions and invites to events. Caring about what others think can be stressful, but material goods offer individuals an opportunity to evaluate their social standing. It can also provide a source of commonality that unifies a group. For example, sustainable companies with well-known clothing brands allow consumers to unify on a common goal of supporting environmentally ethical companies (Mohr et al., Citation2022). Despite markup prices, consumers can identify and share their beliefs with fashionwear as signals to others. By increasing social standing, this can improve someone’s perceived subjective financial well-being. Societal acceptance and satisfaction in life regardless of financial income/savings is also important for someone’s overall happiness.

Implications

Results show variables associated to individuals with a financial scarcity mindset. They tend to be in a lower socioeconomic bracket and care about social perceptions (i.e., impression management). Consumers seek to fulfill their perceived deficiencies with possessions. This artificially inflates their financial status (i.e. subjective financial well-being) as opposed to earning more income to be in a higher socioeconomic status (i.e. objective financial well-being). The outward appearance of material wealth is fulfilling internal shortcomings. In fact, buying expensive goods inadvertently spends the income/savings that if wisely spent could elevate someone’s financial situation. For example, earning a higher education degree could meaningfully increase someone’s annual income over the long-term. Organizations, like universities, that significantly improve the quality of life for citizens can tap into these underlying reasons consumers purchase material goods for status. Universities can advertise historical data showing average graduate income rates and successes they produce in their respective communities. Over the long term these are meaningful improvements in society and improving someone’s financial well-being.

Moreover, financial scarcity is a mindset of having insufficient funds to pay for goods and services.

It is a psychological construct reinforced by contemporary materialism that encourages the purchase of the latest and greatest. Our findings elucidate the importance of supporting alternative ways to generate long-term societal happiness so citizens do not continue to incur insurmountable amounts of debt for goods they cannot afford. Buying conspicuously branded or materialistic goods to impress others subtracts from someone’s finances. Meanwhile, researchers have studied long-term happiness to come from experiential consumption (Alba & Williams, Citation2013; Batat et al., Citation2019). Experiences can take longer to consume (e.g. savoring a meal with friends), take years of practice (e.g. forest birdwatching), and create lifelong memories (e.g. trip around the world). Experiences are more likely to last longer than material goods. Conspicuous material goods often depend on others to acknowledge and will become out of fashion soon after their purchase. For instance, a luxury dress worn to a gala twice risks being called out (for being worn again) and sinking someone’s reputation for style. An outward pursuit to validate someone’s financial well-being through the purchase of expensive goods is often short-lived.

Furthermore, our findings illuminate social and socioeconomic influences on why consumers with a financial scarcity mindset buy materialistic goods. Luxury brands have capitalized on consumer desires for high-class status with over-pricing (e.g. bid on one designer product) (Yeoman, Citation2011). While consumers cannot afford exclusive prestige priced products, it creates an elite brand image that supports the purchase of their other marked up products also called ‘mass luxury’ (Yang and Mattila Citation2014). These are luxury products that are more affordable and accessible to average consumers despite their markup price. The purchase of unaffordable goods does not meaningfully help someone struggling to pay bills on time. Instead, we advocate for educating the public on financial literacy and how the possession of goods does not change someone’s self-worth. Self-worth is dignity and respect someone can give to themselves without material objects (Shultziner & Rabinovici, Citation2012). Self-worth is not trying to fit in by owning the most expensive house or car. It is a recognition that there will continue to be new products to buy and an insatiable appetite for exclusivity. However, someone’s current socioeconomic status can be sufficient to live with dignity and respect when someone is financially responsible.

Limitations and future research

First, given modern capitalistic societies have socioeconomic hierarchies (i.e. low, middle, and upper classes), experiencing financial scarcity will likely persist (Massey et al., Citation1993). Based on our results, individuals will try to fulfill perceived financial scarcity with material goods. However, results are time sensitive to consumer beliefs. It is possible for a countervailing movement to reduce buying goods as a central part of one’s life. For example, we believe it is possible to counteract feelings of inadequacies from materialistic culture with education and mindfulness. Research on mindful consumption describe consumers can be satisfied without excessive spending when they focus on caring for oneself, their community, and for nature (Sheth et al., Citation2011). Mindful consumption may be a way of the future because of excessive debt and overconsumption of natural resources that make high levels of materialism unsustainable.

Furthermore, we believe results from this project provide important insights on opportunities to help consumers stuck in a financial scarcity mindset. First, material goods act as temporary relief from feelings of inadequate self-worth. Second, when having a financial scarcity mindset, low-income and caring about what others think (i.e. impression management) are factors that precede materialism. Mindfulness can help individuals untangle beliefs that drive excessive consumption. For example, people experiencing addictions can receive support to unravel underlying reasons and change behaviors (Murnane & Counts, Citation2014). Likewise, consumers can understand their reasons for excessive buying and change their shopping habits. We believe it is possible to change consumer culture and encourage financial responsibility. For instance, participation in ‘Buy Nothing Day’ is combined with lessons on personal welfare, wastefulness, and financial responsibility (Paschen et al., Citation2020). If culture shifts, results will be relevant for materialistic societies, but less so in more sustainable and mindful ones.

Second, businesses will continue to adapt to changing consumer needs. Results from this study may be time sensitive to societal values. What society prizes as wealth and valuable will change over time. Companies have been able to capitalize on consumers’ needs to feel luxurious and ownership of high-end possessions (Kapferer, Citation2012). However, there is an undercurrent preference for less. Research on minimalism has studied a preference for less for aesthetic appeal (Hook et al., Citation2023; Kang et al., Citation2021; Pangarkar et al., Citation2021). In other words, simplicity is viewed by many favorably (e.g. chic and classy). Possession of more is not always a symbol of wealth. Simplicity and open space centers attention on a single artifact instead of objects diluted by surrounding clutter.

Minimalism can become a form of elegance individuals with a financial scarcity mindset can gravitate towards. This is honoring and cherishing fewer possessions instead of amassing soon forgotten goods. Studying minimalism was beyond the scope of this project. How individuals cope with financial scarcity in materialistic societies is a vast concern. Approximately 32% of U.S. citizens would need to borrow money, sell something, or not be able to cover an unexpected $400 expenditure (The Federal Reserve Board of Governors in Washington DC, Citation2022). It is apparent from this lack of savings, many individuals are spending beyond their means and not satisfied with what they have. Future research can investigate relationships between a financial scarcity mindset and minimalism, as a mechanism to fulfill a desire for abundance. For instance, using one entertainment system in a living room daily increases the value of use, over having multiple systems spread across a house used occasionally. Minimalists can find other ways to increase the value of objects owned.

Third, the main effect in analysis found a financial scarcity mindset related to higher materialism. This builds on prior research describing how consumers attempt to seek associations with high society through possessions (Kraus et al., Citation2012). Associations with brands and owning more objects are related to abundance and wealth in modern materialistic society (Edward Diener & Oishi, Citation2000). How long do consumers feel these positive effects such as a sense of abundance and wealth? Prior research studied the pursuit of material goods tends to relate to lower levels of happiness (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, Citation2002; Kasser & Ahuvia, Citation2002). However, other research suggests experiential purchases provide more long-term benefits (e.g., trips with friends abroad) (Alba & Williams, Citation2013; Batat et al., Citation2019). This project focused on material goods and not on long-term happiness associated to experiential purchases.

Future research can investigate how products needed for experiences compare to non-experiential products. For example, fishing, camping, and team sports gear are material goods, but often necessary items for group activities. Shoppers may categorize these products that support their social needs rather than material goods for collection or display to others. The purchase of experiential products is still the ownership of possessions, but their purpose is to create memories with others. Understanding the distinction between possessions for their purpose of symbolic ownership versus aiding an experience, can help businesses design new products that fulfill consumer’s end goal. For instance, even experiential products like a camping tent can be designed for functionality or an elaborate display to show off to friends. Certain consumers are in a quest to impress others, while others prefer utilitarian value. Researchers can investigate if financial scarcity shoppers are willing to tradeoff function for style for experiential goods.

Fourth, high society is not only related to abundance and wealth, but also power (Kraus et al., Citation2009; Toft, Citation2018). Personal power (e.g. degree of autonomy and control) and societal power (e.g. influence in public policies or with others) are complex constructs (Fiske et al., Citation2016; Van Dijke & Poppe, Citation2006). As a common human motivator, the pursuit for power extends to business operations, organizational structure, and throughout society (Lawrence & Buchanan, Citation2017). While a financial scarcity mindset is likely related to feeling a lack of power (related to a need for control) (Hirschman, Citation1992), studying power was beyond the scope of this project.

Our main effect found a financial scarcity mindset to relate to higher materialism, which suggests someone with a financial scarcity mindset would desire power as a vehicle to accumulate more wealth. Materialism is the belief possessions are central to someone’s livelihood and symbolizes someone’s success (Richins & Dawson, Citation1992). Material goods require money and a degree of influence with others. For example, a materialistic individual may seek a managerial promotion to earn more income, but also requires persuading a team to achieve daily goals. Future research can investigate how the pursuit of power can alleviate a financial scarcity mindset and a lack of self-worth. We believe someone with a financial scarcity mindset with a strong pursuit for material goods would also desire a degree of personal and social power.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen Bok

Stephen Bok is an Assistant Professor at California State University, East Bay in the College of Business and Economics Department of Marketing. He earned his Ph.D. in Business Marketing as a distinguished Graduate Doctoral Teaching Fellow at The University of Texas at Arlington. As a former Stanford Research Fellow at the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education, he fostered an interest in positive psychology and its effect on organizational behaviors. The power of compassion and forward thinking has influenced his philosophical outlook on life.

James Shum

James Shum earned his bachelor’s degree in Accounting at Loyola Marymount University. Work experience with the KPMG accounting firm in San Francisco inspired him to continue his studies to earn his master’s degree in Taxation at Golden Gate University.

Maria Lee

Maria Lee obtained her undergraduate bachelor’s degree in Urban Studies and Planning at San Francisco State University. Then she received her master’s degree in Urban Planning from University of California, Irvine. Due to her growing interest in promoting health and wellness in the community, she then went on to receive her certification as a Nutritional Therapy Practitioner (NTP) from Nutritional Therapy Association. She learned about the societal need to prevent disease and chronic health problems. Since obtaining her NTP certification, she has promoted education of health and nutrition for youth as well as for patients in a clinical setting.

References

- Abela, A. V. (2006). Marketing and consumerism: A response to O’Shaughnessy and O’Shaughnessy. European Journal of Marketing, 40(1/2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560610637284

- Ahuvia, A. C., & Wong, N. Y. (2002). Personality and values based materialism: Their relationship and origins. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(4), 389–402. Elsevierhttps://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1204_10

- Alba, J. W., & Williams, E. F. (2013). Pleasure principles: A review of research on hedonic consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(1)Elsevier:, 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2012.07.003

- Anggarawati, S., Armelly, A., Salim, M., Odilawati, W., Saputra, F. E., & Atmaja, F. T. (2023). The mediating role of narcissistic behavior in the relationship between materialistic orientation and conspicuous online consumption behavior on social media. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2285768. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2285768

- Atkinson, W. (2021). Fields and individuals: From Bourdieu to Lahire and back again. European Journal of Social Theory, 24(2)SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England:, 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431020923281

- Ball, H. L. (2019). Conducting online surveys. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 35(3), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419848734

- Banerjee, R., & Dittmar, H. (2008). Individual differences in children’s materialism: The role of peer relations. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207309196

- Bastos, W., & Levy, S. J. (2012). A history of the concept of branding: Practice and theory. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 4(3), 347–368. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/17557501211252934

- Batat, W., Peter, P. C., Moscato, E. M., Castro, I. A., Chan, S., Chugani, S., & Muldrow, A. (2019). The experiential pleasure of food: A savoring journey to food well-being. Journal of Business Research, 100, 392–399. Elsevierhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.024

- Bauer, M. A., Wilkie, J. E. B., Kim, J. K., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2012). Cuing consumerism: Situational materialism undermines personal and social well-being. Psychological Science, 23(5), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611429579

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

- Berg, L. (2015). Consumer vulnerability: Are older people more vulnerable as consumers than others? International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(4), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12182

- Bhat, C. R. (1994). Imputing a continuous income variable from grouped and missing income observations. Economics Letters, 46(4), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(94)90151-1

- Biswas-Diener, R. (2008). Material wealth and subjective well-being. The Science of Subjective Well-Being, 307–322. https://smartlib.umri.ac.id/assets/uploads/files/77459-subjective-well-being.pdf#page=321.

- Brister, D., & Brister, P. (1987). The vicious circle phenomenon. Diadem.

- Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). Amazon’s mechanical turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393980

- Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2002). Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(3), 348–370. https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/29/3/348/1800916. https://doi.org/10.1086/344429

- Cannon, C., Goldsmith, K., & Roux, C. (2019). A self-regulatory model of resource scarcity. Edited by Amna Kirmani. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 29(1), 104–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1035

- Castro, D., & Bleys, B. (2023). Do people think they have enough? A subjective income sufficiency assessment. Ecological Economics, 205, 107718. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800922003792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107718

- Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2023). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y

- Coppock, A., & McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research & Politics, 6(1), 205316801882217. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018822174

- Cova, B. (1997). Community and consumption: Towards a definition of the ‘linking value’ of product or services. European Journal of Marketing, 31(3/4), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569710162380

- Cundiff, J. M., Boylan, J. M., & Muscatell, K. A. (2020). The pathway from social status to physical health: Taking a closer look at stress as a mediator. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(2), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420901596

- D’Andrea, G., Ring, L. J., Lopez Aleman, B., & Stengel, A. (2006). Breaking the myths on emerging consumers in retailing. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 34(9), 674–687. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550610683193

- Davidson, N. M. (2008). Property and relative status” Michigan Law Review, 107(5), 757–817. HeinOnline

- De Bruijn, E.-J., & Antonides, G. (2022). Poverty and economic decision making: A review of scarcity theory. Theory and Decision, 92(1), 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-021-09802-7

- De Mooij, M., & Hofstede, G. (2010). The Hofstede model: Applications to global branding and advertising strategy and research. International Journal of Advertising, 29(1), 85–110. https://doi.org/10.2501/S026504870920104X

- Dickson, P. R. (2000). Understanding the trade winds: The global evolution of production, consumption, and the internet. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(1), 115–122.). https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/27/1/115/1791516. https://doi.org/10.1086/314313

- Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 119–169. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014411319119

- Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and Subjective well-being across nations. Culture and Subjective Well-Being, 185–218. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=36c977fd5337fbaa53762563428fd4081c8e132d

- Dittmar, H. (2007). Consumer culture, identity and well-being: The Search for the “good life” and the “body perfect. Psychology Press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=4Ed4AgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=SuNo_yqZj2&sig=pQ2NucfPpUbya3GVvtaEDdFozN8.

- Dittmar, H., Beattie, J., & Friese, S. (1996). Objects, decision considerations and self-image in men’s and women’s impulse purchases. Acta Psychologica, 93(1-3), 187–206. Elsevier https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6918(96)00019-4

- Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192

- Douglas, B. D., Ewell, P. J., & Brauer, M. (2023). Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. Plos One, 18(3), e0279720. USAhttps://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279720

- Drever, A. I., Odders-White, E., Kalish, C. W., Else-Quest, N. M., Hoagland, E. M., & Nelms, E. N. (2015). Foundations of financial well-being: Insights into the role of executive function, financial socialization, and experience-based learning in childhood and youth. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49(1), 13–38. Wiley Online Libraryhttps://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12068

- Ebert, J. F., Huibers, L., Christensen, B., & Christensen, M. B. (2018). Paper- or web-based questionnaire invitations as a method for data collection: Cross-sectional comparative study of differences in response rate, completeness of data, and financial cost. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(1), e24. https://www.jmir.org/2018/1/e24/. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8353

- Fiske, S. T., Dupree, C. H., Nicolas, G., & Swencionis, J. K. (2016). Status, power, and intergroup relations: The personal is the societal. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.012

- Garðarsdóttir, R. B., & Dittmar, H. (2012). The relationship of materialism to debt and financial well-being: The case of iceland’s perceived prosperity. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(3), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.12.008

- Ghosh, S. (1998). Making business sense of the internet. Harvard Business Review, 76(2), 126–135. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA20496574&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=00178012&p=AONE&sw=w.

- Goffman, E. (2016). The presentation of self in everyday life. In Social theory re-wired (pp. 482–493). Routledge.

- Goldsmith, K., Roux, C., & Cannon, C. (2021). Understanding the relationship between resource scarcity and object attachment. Current Opinion in Psychology, 39, 26–30. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352250X20301202?casa_token=4XfQSZP1RFwAAAAA:WmDDf59ubTJEf_npLzO99bsA-7bIurZ3eZPRaGYpbMNPQK3amsyyqiI5caUd9I94R9eUh4uir_M. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.012

- Hampson, D. P., Ma, S. (., Wang, Y., & Han, M. S. (2021). Consumer confidence and conspicuous consumption: A conservation of resources perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(6), 1392–1409. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12661

- Han, Y. J., Nunes, J. C., & Drèze, X. (2010). Signaling status with luxury goods: The role of brand prominence. Journal of Marketing, 74(4), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.4.15

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

- He, W., & Jia, S. (2024). Exploring multigenerational co-residence in the United States. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 17(2), 517–538. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJHMA-06-2022-0089/full/html. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHMA-06-2022-0089

- Higley, S. R. (1995). Privilege, power, and place: The geography of the American upper class. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hilbert, L. P., Noordewier, M. K., & van Dijk, W. W. (2022a). The prospective associations between financial scarcity and financial avoidance. Journal of Economic Psychology, 88, 102459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2021.102459

- Hilbert, L. P., Noordewier, M. K., & van Dijk, W. W. (2022b). Financial scarcity increases discounting of gains and losses: Experimental evidence from a household task. Journal of Economic Psychology, 92, 102546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2022.102546

- Hill, R. P. (2001). Surviving in a material world: The lived experience of people in poverty. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Hirschman, E. C. (1992). The consciousness of addiction: Toward a general theory of compulsive consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(2), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1086/209294

- Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (1992). Hogan personality inventory manual. 2nd ed. Hogan Assessment Systems.

- Hook, J. N., Hodge, A. S., Zhang, H., Van Tongeren, D. R., & Davis, D. E. (2023). Minimalism, voluntary simplicity, and well-being: A systematic review of the empirical literature. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(1), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1991450

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008 Evaluating model fit: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature [Paper presentation]. In 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, 2008:195–200.

- Hu, L-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10705519909540118. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huijsmans, I., Ma, I., Micheli, L., Civai, C., Stallen, M., & Sanfey, A. G. (2019). A scarcity mindset alters neural processing underlying consumer decision making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(24), 11699–11704. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818572116

- Inglehart, R. (2015). The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles among western publics. Princeton University Press.

- Kalil, A., Mayer, S., & Shah, R. (2023). Scarcity and inattention. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper. no. 2022–2076.

- Kane, L., & Ashbaugh, A. R. (2017). Simple and parallel mediation: A tutorial exploring anxiety sensitivity, sensation seeking, and gender. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 13(3), 148–165. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.13.3.p148

- Kang, J., Martinez, C. M. J., & Johnson, C. (2021). Minimalism as a sustainable lifestyle: Its behavioral representations and contributions to emotional well-being. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, 802–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.02.001

- Kapferer, J.-N. (2012). Abundant rarity: The key to luxury growth. Business Horizons, 55(5), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2012.04.002

- Kasser, T. (2003). The high price of materialism. MIT press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2ekg225NTSwC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&ots=UoO7tG7Nye&sig=ZRtuZ5XVJSTNysCr0MNA-L09iaY.

- Kasser, T., & Ahuvia, A. (2002). Materialistic values and well-being in business students. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.85

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(3), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296223006

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications.

- Kluegel, J. R., & Smith, E. R. (2017). Beliefs about inequality: Americans’ views of what is and what ought to be. Routledge.

- Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., & Keltner, D. (2009). Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 992–1004. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016357

- Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., Rheinschmidt, M. L., & Keltner, D. (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychological Review, 119(3), 546–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028756

- Lawrence, T. B., & Buchanan, S. (2017). Power, institutions and organizations. The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 477–506). Sage Publications London.

- Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34

- Levay, K. E., Freese, J., & Druckman, J. N. (2016). The demographic and political composition of mechanical turk samples. Sage Open, 6(1), 215824401663643. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016636433

- Lewis, R., Rao, J. M., & Reiley, D. H. (2015). Measuring the effects of advertising: The digital frontier. In Economic analysis of the digital economy (pp. 191–218). University of Chicago Press.

- Loranger, D., & Roeraas, E. (2023). Transforming luxury: Global luxury brand executives’ perceptions during COVID. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 14(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2022.2097938

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

- Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science (New York, N.Y.), 341(6149), 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238041

- Martins, C. (2003). Becoming consumers: Looking beyond wealth as an explanation for villa variability. Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal (2002), 84–100. https://traj.openlibhums.org/article/id/3808/download/pdf/. https://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC2002_84_100

- Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2938462. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938462

- Matt, S. J. (2003). Keeping up with the Joneses: Envy in American Consumer Society, 1890-1930. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- McDonough, P. M., & Calderone, S. (2006). The meaning of money: perceptual differences between college counselors and low-income families about college costs and financial aid. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(12), 1703–1718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764206289140

- Meuris, J., & Leana, C. R. (2015). The high cost of low wages: Economic scarcity effects in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 35, 143–158. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0191308515000027?casa_token=PdYFtyVzg5cAAAAA:3LZbsegMEIqy6zH1fTBN7IaFAYxUWSBdcoVV4ZR2tjvRFbVRQsH59m7-fqjNucyGmDghzS0eW0E. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2015.07.001

- Mickelson, K. D., & Williams, S. L. (2008). Perceived stigma of poverty and depression: examination of interpersonal and intrapersonal mediators. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(9), 903–930. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.9.903

- Miles, J. (2014). Tolerance and variance inflation factor. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. Wiley Online Library.

- Mohr, I., Fuxman, L., & Mahmoud, A. B. (2022). A triple-trickle theory for sustainable fashion adoption: The rise of a luxury trend. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 26(4), 640–660. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JFMM-03-2021-0060/full/html. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-03-2021-0060

- Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., Audretsch, D. B., & Santos, S. (2022). Overcoming the liability of poorness: Disadvantage, fragility, and the poverty entrepreneur. Small Business Economics, 58(1), 41–55. Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00409-w

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. Macmillan.

- Murnane, E. L., & Counts, S. (2014 Unraveling abstinence and relapse: Smoking cessation reflected in social media [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1345–1354. Toronto Ontario Canada: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557145

- Nanda, A. P., & Banerjee, R. (2021). Consumer’s subjective financial well-being: A systematic review and research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 750–776. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12668

- Pandelaere, M. (2016). Materialism and well-being: The role of consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology, 10, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.027

- Pangarkar, A., Shukla, P., & Charles, R. (2021). Minimalism in consumption: A typology and brand engagement strategies. Journal of Business Research, 127, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.033

- Paschen, J., Wilson, M., & Robson, K. (2020). # BuyNothingDay: Investigating consumer restraint using hybrid content analysis of Twitter data. European Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 327–350. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/EJM-01-2019-0063/full/html?casa_token=Uyb5BsTnl9oAAAAA:tZsSS4gCb42ch8k5H5aOftImliAfs8gSitjkMYzf0uffRDzPYtma8YKrdvH9oUmSms7yTRfRSbkBWw5aGfZsNxoCTA1HTrOuFsp7tcs5QQ0hQUwq0A. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-01-2019-0063

- Peer, E., Rothschild, D., Gordon, A., Evernden, Z., & Damer, E. (2022). Data quality of platforms and panels for online behavioral research. Behavior Research Methods, 54(4), 1643–1662. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01694-3

- Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2018). Unpacking the inequality paradox: The psychological roots of inequality and social class. In Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 57, pp. 53–124). Elsevier.

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers: a Journal of the Psychonomic Society, Inc, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03206553

- Prewett, M. S., Tett, R. P., & Christiansen, N. D. (2013). A review and comparison of 12 personality inventories on key psychometric characteristics. In Handbook of personality at work (pp. 191–225). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203526910-12/review-comparison-12-personality-inventories-key-psychometric-characteristics-matthew-prewett-robert-tett-neil-christiansen.

- Rank, M. R. (1994). Living on the edge: The realities of welfare in America. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/rank08424

- Richards, L. G. (1965). Consumer practices of the poor. Welfare Rev, 3, 1.

- Richins, M. L. (2004). The material values scale: measurement properties and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1086/383436

- Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316. The University of Chicago Presshttps://doi.org/10.1086/209304

- Ritzer, G. (2005). Enchanting a disenchanted world: Revolutionizing the means of consumption. Pine Forge Press.

- Ruvio, A. A., & Shoham, A. (2011). Aggressive driving: A CONSUMPTION EXPERIENCE. Psychology & Marketing, 28(11), 1089–1114. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20429

- Sayre, G. M. (2022). The costs of insecurity: Pay volatility and health outcomes. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(7), 1223–1243. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001062

- Schembri, S. (2009). Reframing brand experience: The experiential meaning of Harley–Davidson. Journal of Business Research, 62(12), 1299–1310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.11.004

- Schmidt, F. L., Le, H., & Ilies, R. (2003). Beyond alpha: An empirical examination of the effects of different sources of measurement error on reliability estimates for measures of individual-differences constructs. Psychological Methods, 8(2), 206–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.8.2.206

- Shah, A. K., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2012). Some consequences of having too little. Science (New York, N.Y.), 338(6107), 682–685. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1222426

- Shah, A. K., Zhao, J., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2018). Money in the mental lives of the poor. Social Cognition, 36(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2018.36.1.4

- Sheth, J. N., Sethia, N. K., & Srinivas, S. (2011). Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0216-3

- Shim, S., Xiao, J. J., Barber, B. L., & Lyons, A. C. (2009). Pathways to life success: A conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(6), 708–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2009.02.003

- Shrum, L. J., Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2004). A process model of consumer cultivation: The role of television is a function of the type of judgment. In The psychology of entertainment media: Blurring the lines between entertainment and persuasion (pp. 177–192). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/L-Shrum/publication/342988954_A_Process_Model_of_Consumer_Cultivation_The_Role_of_Television_Is_a_Function_of_the_Type_of_Judgment/links/5f1086da299bf1e548baa6b9/A-Process-Model-of-Consumer-Cultivation-The-Role-of-Television-Is-a-Function-of-the-Type-of-Judgment.pdf.

- Shrum, L. J., Wong, N., Arif, F., Chugani, S. K., Gunz, A., Lowrey, T. M., Nairn, A., Pandelaere, M., Ross, S. M., Ruvio, A., Scott, K., & Sundie, J. (2013). Reconceptualizing materialism as identity goal pursuits: Functions, processes, and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1179–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.010

- Shultziner, D., & Rabinovici, I. (2012). Human dignity, self-worth, and humiliation: A comparative legal–psychological approach. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 18(1), 105–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024585

- Sommet, N., Morselli, D., & Spini, D. (2018). Income inequality affects the psychological health of only the people facing scarcity. Psychological Science, 29(12), 956797618798620–956797618791921. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618798620

- Stern, S. (1991). Imputing a continuous income variable from a bracketed income variable with special attention to missing observations. Economics Letters, 37(3), 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(91)90224-9

- Tay, L., Zyphur, M., & Batz, C. L. (2018). Income and subjective well-being: Review, synthesis, and future research. In Handbook of well-being. DEF Publishers.

- Tedeschi, J. T. (2013). Impression management theory and social psychological research. Academic Press.

- Terhanian, G., Bremer, J., Olmsted, J., & Guo, J. (2016). A process for developing an optimal model for reducing bias in nonprobability samples: The quest for accuracy continues in online survey research. Journal of Advertising Research, 56(1), 14–24. https://www.journalofadvertisingresearch.com/content/56/1/14.short. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2016-009

- The Federal Reserve Board of Governors in Washington DC. (2022). “Dealing with Unexpected Expenses.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2022-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2021-dealing-with-unexpected-expenses.htm.

- Toft, M. (2018). Upper-class trajectories: capital-specific pathways to power. Socio-Economic Review, 16(2), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwx034

- Tomm, B., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2016). Scarcity captures attention and induces neglect: Eyetracking and behavoral evidence. PsyArXiv.

- Tuominen, J., Rantala, E., Reinikainen, H., Luoma-Aho, V., & Wilska, T.-A. (2022). The brighter side of materialism: Managing impressions on social media for higher social capital. Poetics, 92, 101651. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304422X22000080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2022.101651

- Van Boven, L. (2005). Experientialism, materialism, and the pursuit of happiness. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.132

- Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1193–1202. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1193

- Van Dijk, W. W., van der Werf, M. M. B., & van Dillen, L. F. (2022). The psychological inventory of financial scarcity (PIFS): A psychometric evaluation. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 101, 101939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2022.101939

- Van Dijke, M., & Poppe, M. (2006). Striving for personal power as a basis for social power dynamics. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(4), 537–556. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.351

- Veltri, G. A., & Ivchenko, A. (2017). The impact of different forms of cognitive scarcity on online privacy disclosure. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 238–246. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563217301693?casa_token=23wl0Y-2kBEAAAAA:mD61EEXJJg6tblPrIB9Hcd5eJsnu_AHVRC8eWUJJ96uYW4fzdGurY8UAdLPtnUpzl8SwOJYmI7Q. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.018

- Vohs, K. D. (2013). The poor’s poor mental power. Science (New York, N.Y.), 341(6149), 969–970. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244172