Abstract

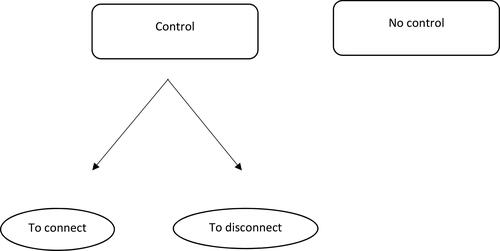

As Covid-19 circulated worldwide, lockdowns forced individuals to connect virtually in order to continue maintaining relationships. The current study sought to understand the impact of these online interactions on students’ mental health and wellbeing. Semi structured interviews were conducted with 17 students. Two main themes were uncovered: control (1) and no control (2). Participants reported that having control over online interactions helped them to choose when, how often and with whom to connect as well as disconnect which benefited and enhanced their wellbeing during the lockdown period. On the other hand, lack of control over interactions online resulted in students feeling anxious, stressed and unable to maintain healthy boundaries. The concept of control and its link to wellbeing has previously been explored in literature and this study reinforces the idea that individuals experience an enhanced sense of wellbeing when able to control important areas of their lives.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

1.1. Covid outbreak

On 11 March 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak (which originated in the province of Wuhan, China) was declared as a global pandemic by World Health Organisation (WHO) due to the rapid spread and severity of cases (Velavan & Meyer, Citation2021). To reduce the spread of the virus and its devastating effects on public health, governments across the globe responded by introducing unprecedented measures (Loades et al., Citation2020). Such measures resulted in periods of lockdown, quarantine, and self-isolation, which required people to stay at home and have very limited in-person interactions to minimise the spread of the virus (Atalan, Citation2020; Kharroubi & Saleh, Citation2020). These measures negatively impacted individuals, with many reporting a significant increase in loneliness, anxiety, depression, insomnia, alcohol and substance use, self-harm, and suicidal behaviours (Kumar & Nayar, Citation2021; Meyerowitz-Katz et al., Citation2021). As a result of the compulsory lockdown and the unpredictable nature of the pandemic, many individuals experienced a loss of control which negatively impacted their wellbeing (Usher et al., Citation2020).

1.2. Control and wellbeing

One theoretical framework that is able to explain why losing control over important aspects of one’s life during COVID-19 and being forced into lockdown had a detrimental impact on individuals’ mental health is Perceptual Control Theory (PCT, (Powers, Citation1973). According to PCT, having control or having things according to our preferences is essential to wellbeing and successful functioning. However, if/when that control is taken away (lockdown, isolation, inability to meet friends and family), individuals might begin to experience distress as they seek to restore control over important aspects of their lives. If they are unable to restore control, psychological distress can develop (Carey et al., Citation2015).

Previous qualitative research exploring individuals’ lived experience of mental health distress has found common themes around control and loss of control as key aspects in the process of maintaining wellbeing and recovering from ill health. These studies included a variety of groups such as adolescents (Churchman et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2021, Citation2022), university students (Higginson & Mansell, Citation2008), primary care patients (McEvoy et al., Citation2012) experiencing a range of difficulties such as bipolar disorder (Mansell et al., Citation2010), eating problems (Alsawy & Mansell, Citation2013). Across most of these studies, people describe the most acute periods during their difficulties, as loss of control or being at ‘rock bottom’ and the process of recovery as re/gaining control.

1.3. Internet use

Whilst isolated and unable to maintain in-person interactions, individuals aimed to restore control over important areas of their lives by turning to digital technology to connect, maintain relationships, access information, services and education (Beaunoyer et al., Citation2020; Gabbiadini et al., Citation2020; Pandey et al., Citation2021). The amount of time spent on digital devices using technology, known as screen time, drastically increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, online communications became the primary source of interaction with family, friends, and others (Garfin, Citation2020).

Prior to COVID-19 spreading across the world and the reinforced national lockdowns that followed, studies emerged around the excessive use of internet suggesting that internet addiction is a growing and concerning problem (Fernandes et al., Citation2020). Studies exploring the use of internet (whether excessive or problematic) (Çikrıkci, Citation2016; Pandya & Lodha, Citation2021) indicated that this might have a negative impact on individuals, particularly young people (Çikrıkci, Citation2016). Young people (in their pursuit to find social acceptability, belong to a community, and maintain anonymity) have been identified as a vulnerable group particularly susceptible to internet addiction (Cheung et al., Citation2018). It has been reported that this dysfunctional and excessive internet use among young people, has the potential to pose a threat to their physical as well as mental health. Various studies have highlighted how excessive internet use can lead to a number of issues such as cognitive deficits (Ioannidis et al., Citation2019), various mental health difficulties (depression, physical aggression, sleep-related issues), physical health challenges, and relational problems (Saunders et al., Citation2017).

However, with the imposed COVID-19 lockdowns and reduced control over important aspects of their lives, individuals were forced to be creative about their communications and interactions. In their pursuit to restore control and maintain wellbeing, individuals drastically increased their online communications. The lockdowns forced individuals to be creative in all areas of their lives and as a result, new initiatives such as virtual holidays, virtual meals and virtual dating were born (Pandya & Lodha, Citation2021). Virtual meetings (e.g. voice calls, video calls, online multiplayer games and watching movies together in groups online) increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic and offered users a perceived sense of social support while reducing feelings of loneliness, boredom, and anger (Gabbiadini et al., Citation2020).

Many people engaged in virtual meetings during lockdowns to recreate in-person meetings, which increased intimacy and togetherness between friends, families, and romantic partners (Brown & Greenfield, Citation2021; Strouse et al., Citation2021). Whilst younger generations reported using social media interactions (e.g. liking, commenting, scrolling, etc.) and text messaging the most, they felt greatest satisfaction from video call interactions (Juvonen et al., Citation2021). Masur (Citation2021) suggested that online interactions that involve a more active role within the individual (e.g. making conversation, commenting, liking) are associated with greater satisfaction than passive interactions (e.g. browsing and scrolling) (Masur, Citation2021). Direct online interactions have been reported to facilitate a stronger sense of social presence and connectedness (Nguyen et al., Citation2021; Winstone et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, passive interactions (e.g. browsing and scrolling) have been reported to increase the likelihood of negative effects on individuals’ health (Masur, Citation2021).

1.4. Lockdown and internet use

But with social distancing and lockdowns in place, individuals had no choice but to use social media and the internet to connect, socialise and access support. Particularly, university students (whilst completing their ongoing studies in isolation) relied heavily on online interactions as a result of being physically isolated and living away from family and friends (Misirlis et al. Citation2020). Once face-to-face interactions became limited during the pandemic, students became primarily dependent on online interactions to gain social support, maintain relationships, and feel a sense of belonging (Magis-Weinberg et al. Citation2021; Stebleton et al., Citation2022). Equally, sharing intimate moments with friends online, along with funny and positive online interactions alleviated loneliness and stress during the pandemic (Juvonen et al., Citation2021; Marciano et al., Citation2022). These were some of the positive outcomes related to online interactions during COVID-19. These reports are similar to earlier findings conducted prior to COVID-19, where the need to belong was positively related to screen time and use of social media (Kim et al., Citation2016).

Nevertheless, students also reported facing challenges and having negative experiences. One major area that students reported negative experiences in included the use of internet for the purpose of studying/continuing attending university online (Saha et al., Citation2021). Students experienced various frustrations and challenges as they sought to continue their studies online including slow internet, lack of adequate equipment, power shortages, etc., which added to students’ stress and anxiety (Misirlis et al., Citation2020; Sifat, Citation2020).

Additionally, the excessive use of online interactions during COVID-19 also led to negative consequences. During the pandemic, individuals experienced an increase exposure to negative content, social comparison, and fear of missing out (Marciano et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, an increase in social media use was shown to potentially further exacerbate the reduced perception of control in individuals. Brailovskaia et al.’s (Citation2021) study found that individuals who experienced loss of control over important areas of their lives were more prone to engage in excessive social media use due to fear of missing out (FoMO) (Brailovskaia et al., Citation2021).

Negative content, such as COVID-19-related news consumption and fear-mongering adverts negatively impacted individuals and particularly active users such as young people. Reports have found that exposure to misinformation in addition to the pandemic’s ongoing detrimental impact was associated with increased anxiety, depression, and isolation in young people accessing this information on social media platforms (Strasser et al., Citation2022). Studies reported that rumination of negative content mediated the relationship between social media exposure and psychological distress. On the other hand, being mindful and controlling social media exposure acted as a protective factor (Hong et al., Citation2021).

1.5. Aims

Considering the mixed literature available on the positive and negative outcomes of internet use among young people coupled with the unique COVID-19 period and the imposed lockdowns where individuals were forces to move all interactions online, the current study sought to understand how online interactions impacted the mental health and wellbeing of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study explored whether students engaged in online interactions, what type of interactions they engaged in, the frequency of these interactions and also the impact of these interactions on their wellbeing and mental health.

2. Method

This study received ethical approval from the University of Manchester Ethics Committee (Ref: 2022-13544-23234).

2.1. Design

The study was conducted using a qualitative design and data was collected through semi-structured interviews. The interviews were audio recorded using Zoom software and then transcribed verbatim. The data was analysed using a reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Interviews, coding and analysis were conducted by two researchers.

2.2. Participants

University students were recruited online via social media posts and through research posters distributed across a university in the North-West of England. A total of 17 participants were recruited and interviewed for the study. Of these, 12 were females (70.59%) and 5 were males (29.41%). The inclusion criteria consisted of having access to a digital device and internet connection during the pandemic. Participants were also required to have access to Zoom in order to take part in the study.

In order to maintain participants’ confidentiality during the study, participants were assigned an ID number by the researcher after they consented to participate in the study. Qualtrics (questionnaire software) was used to collect demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, year of study, and place of residence during lockdown periods). This was done using participant ID numbers to ensure participants’ confidentiality. Interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom on an encrypted laptop using the university’s encrypted connection. The interviews were anonymised at the point of transcription.

The exclusion criteria included living with or having received a diagnosis of a mental health condition. The majority of the students who took part in the study were White British except for seven students who identified as White Irish, Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan and Nordic. The mean age was 22.18 (SD = .73).

2.3. Materials

A demographics questionnaire was created using Qualtrics. Participants were asked for their age, gender, ethnicity, year of study in 2020, accommodation in 2020, year of study in 2021, accommodation in 2021, and current year of study. Each participant completed the Qualtrics survey and submitted it before the interview commenced. In some instances, where the students could not access the questionnaire, they received it as an email attachment, which they later completed and submitted.

Additionally, a topic guide was developed to help with conducting the interviews. The guide consisted of questions based on three topics; the types of online interactions students had during the pandemic, who they had online interactions with, and how the online interactions impacted their wellbeing. Example questions included ‘how often did you have these interactions?’, ‘with whom did you have these interactions?’, ‘how did you feel before and after these interactions?’. The topic guide provided a flexible structure to the interview and did not control the conversations.

2.4. Procedure

Recruitment occurred using a poster, which was specifically designed and used for the study. The poster was placed around the university and posted on social media with a brief caption. The poster advertisement provided details about the study and informed potential participants that the researchers were offering a shopping voucher as a thank you for taking part in the study. Additional information included contact details for both researchers, how to take part in the study, what would happen with participants’ data, and participants’ rights to withdraw.

All participants were given an information sheet, which offered detailed information about the study. Additionally, informed consent was obtained prior to participants being interviewed. At the beginning of the interview, the participants were asked if they had read the participant information sheet and whether they had any questions about it. Then, they were provided with a verbal overview of the document to ensure that participants understood the information offered in the document. Next, participants were sent a link to the demographics questionnaire to complete before the interview began. Interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom. The length of the interviews ranged between 12 and 45 min.

During the interviews, participants were asked several questions regarding their online interactions and how the interactions may have impacted their well-being. All interviews followed the natural flow of the conversation and expanded on the thoughts and feelings of the participants. At the end of the interview, participants were fully debriefed and informed of the time they had to request to remove their data from the study in the event they changed their mind.

2.5. Data analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and then analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA). RTA was used to analyse the data, as it is an accessible and theoretically flexible approach (Byrne, Citation2022). From an epistemological viewpoint, an essentialist approach was used in the data analysis, taking into consideration the experiential aims of this study. This approach was taken to gain an understanding of students’ experiences of online interactions through a direct reflection of the language participants used to communicate (Byrne, Citation2022). Data was coded inductively at a semantic level. This was to ensure that the codes were identified through descriptive analysis of the data, focusing on the reality of what the participants were saying by exploring the explicit language participants used (Braun et al., Citation2019; Byrne, Citation2022).

Data analysis was carried out by following the six phases to RTA as outlined by Braun and Clarke (Braun et al., Citation2019). Phase 1: the researchers engaged and familiarised themselves with the data by reading and re-reading transcripts and noting down initial ideas. Phase 2: once researchers familiarised themselves with the data, initial codes were generated by colour coding and using the comment feature on Microsoft Word (2021). Phase 3: coded data was reviewed and organised into groups with shared meanings, which generated initial potential themes. Phase 4: the initial themes were reviewed against coded data extracts and the overall data set to ensure that they were accurately representing the data. A thematic map was also developed at this stage to have a clear visualisation of the distinct themes. Phase 5: themes were refined and defined to ensure they were clear and coherent. Phase 6: a report of the findings was produced including themes, subthemes, and data extracts to illustrate how online interactions impacted students’ wellbeing during the periods of lockdown. Ellipses ([…]) indicate omitted text to provide clearer understanding of the data extract.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

During the first 2020 lockdown, 64.7% (11) of participants lived at home with their family and 35.3% (6) lived in other accommodation such as university halls, rented accommodation, or house sharing. During the second 2020/21 lockdown, 52.9% (9) participants lived at home and 47.1% (8) lived in other accommodation. Participants’ current year of study at university ranged between 3rd year at undergraduate level to postgraduate level. During lockdown periods, participants’ year of study varied between first year at undergraduate level to postgraduate level. Most of the data were clustered around years 3, 4 and postgraduate study (see ).

Table 1. Demographics information.

3.2. Reflexive thematic analysis

The interviews generated a wealth of information presenting details about students’ online interactions during lockdown as well as their views on how these interactions directly or indirectly impacted their well-being.

The data generated two main themes which were able to summarise students’ experiences: On one hand, students emphasised that online interactions gave them more control, (1) while at the same time, they felt they had no control (2). The first theme contains two subthemes: to connect (i) and to disconnect (ii). For an overview of the thematic map, please see .

Control [‘to control something is to act to bring it to a specified condition, and then maintain it close to that condition even if unpredictable external forces and changes in environmental properties tend to alter it’ (Powers, Citation2008, p. xi)]

The first theme that became apparent from participants’ views and feedback in relation to online interactions and the impact these had on their wellbeing was ‘control’. Participants reported that being able to control (when to connect or disconnect) positively impacted their wellbeing. Most of the participants emphasised that online interactions during lockdown offered them more control and choice over how they interacted directly and indirectly with individuals and online content: ‘I suppose it’s like a different mode of social interactions … I was in control of it. So, when you’re out face to face, it’s like you don’t wanna say: ‘oh, I’ve got to go now sorry, because you’ll feel bad but when I was on my laptop it was like I was in control if I didn’t want to meet online. I didn’t have to feel bad about saying: oh, I don’t want to, or like, you know you can kind of just end the call and that’s it. You haven’t got to drive home or anything like that so yeah, like I think that’s kind of why I like it, ‘cause I felt in control of the social interaction’ (P12).

Considering the impact on their wellbeing, students highlighted that having control over their interactions and ability to step away from detrimental posts/interactions was beneficial to their wellbeing: ‘So sometimes I would have to step away from it and I am quite good at knowing when okay I need a break like this isn’t making me feel good’ (P14). Similarly, P15 highlighted how control allowed them to choose what they were viewing on social media platforms: ‘It was after the summer when we got locked down again. I unfollowed a lot of people on Instagram, but not friends but people, you know like, people that I’d followed like models or, you know, people like that. Erm, I think that was really good for my well-being’.

News related information about COVID-19 was described as ‘fearmongering’ (P2,5) and created feelings of distress and overwhelmingness in participants as it made them feel powerless about what was happening in the world, thus reducing their perception of control. To cope, participants often took action to control their exposure of unwanted content in forms of blocking and muting pages, unfollowing people, and deleting apps, which helped improve their mental wellbeing.

The ability to control what information and content they were exposed to was evident in students’ feedback: ‘I suppose it makes you feel like you have a bit more like control over what you see online’ (P6). By taking control over their online interactions, participants were able to personalise their interactions with the content available online: ‘I also found that that social media was easier to curate my own experience. They have a really good blocking system, so when I’m getting frustrated with things like Covid, and if I just didn’t wanna like listen to it you know day in and day out cause you know it was kinda hard to avoid. I found it really easy to block that information a bit and just have that escapism’ (P16).

Online interactions offered participants the ease of access to connect with whom they wanted when they wanted. Picking and choosing when and who to speak to offered students choice and control: ‘Well, I can go on Discord and have like 20 people I can talk to. And if I don’t wanna talk to them. I just don’t. It’s kinda like you just pick and choose whenever you want to do it’ (P17).

The control theme contains two subthemes (a) to connect and (b) to disconnect.

Connect

In their interviews, participants explained how having control over their online interactions provided them with great opportunities to connect with loved ones as well as new individuals. Participants recognised that because of the imposed lockdown and covid restrictions they were able to spend more time online which impacted their relationships on a number of levels. Participants reflected that they ‘were able to speak more frequently’ (P11), which led to greater levels of ‘intimacy’ (P11), and helped them to ‘bond a lot more’ (P1). Participants reported that they were able to engage in meaningful and deep conversations which led to increased closeness: ‘it gives you a sense of closeness, you get more personal with them’ (P10).

The ability to connect online coupled with the restrictions of lockdown where individuals were forced to stay at home, allowed individuals to choose when and how often to connect with family and friends which directly impacted the quality of their relationships: ‘I guess you tend to get a lot closer with some of those friends, being on with them basically 24/7. Yeah, I guess it’s just, you learn a lot more about certain people’ (P10). A number of participants reflected on the impact of this increased communication and recognised that increased time spent online together strengthened their relationships and deepened their bond: ‘I felt that a lot with many of the interactions that I had with my friends online that sometimes when we were having conversations, normally we would have not at face value conversations but for example, just quite general topics. But then, when we got to online and particularly during the peak of lockdown, we began to open up to each other a lot more. I think we learned more about one another. During that time than we ever had when we were in person’ (P11).

The connection expanded beyond family members or friends and included forming new meaningful relationships too: ‘But like cause you’re trying to impress on the dating app. I feel like you actually sometimes get some good conversations, because people put in the time and the effort. So that’s kind of nice to have like different debates with people. Yeah. So I would say like it was a bit nice to like have like constant conversation. I mean it’s easy to say when you’re a girl like, cause I definitely think guys have a different experience on dating apps. But yeah, it’s basically almost a guaranteed conversation when you would want it was nice’ (P16). On both occasions, participants highlighted the key aspects that facilitated these interactions: the ability to connect when they wanted and the time available to invest in these relationships.

Disconnect

Participants also highlighted how having control over their online interactions ‘made it really a lot easier to disconnect’, as it was ‘far easier to like cut people off’ using online channels (P5).

The opportunity to manage relationships online offered participants more control and awareness over what was important to them, and which relationships no longer worked or needed sustaining: ‘Online interactions also gave the notion of maybe how not so close you were with individuals and then after the lockdown those relationships simply fizzled out which wasn’t a bad thing. It definitely illustrated okay, where are your priorities, it helped to see which friendships you treasured and which ones not necessarily you no longer wanted’ (P11).

A number of participants also recognised that some of their relationships changed during this period and because of the online platforms they could choose who to connect with: ‘So, I could definitely tell that there was a change there in that I then just like sacked off the other [laughs] sacked off like half because I was like: ‘you are too much, you’re not’, I think you become more I don’t want to say more picky, but you definitely become a lot more selective in like who you communicate with’ (P5). Participants felt that using online platforms made it easier not only to assess relationships but also be bold in how they used their time and who they connected with: ‘You couldn’t physically see them; definitely you know it’s hard to cut off a relationship for someone that you see every day at work or school, so like, you know, stuff like that. You kind of have to be a grown up and be like if I see them every day, you gotta be civil and try but if you’re not seeing them every day like you don’t owe them your time if you don’t like them’ (P16).

No control

The second theme that summarises participants’ views on the impact of online interactions on their welling is ‘no control’. Participants spoke about various online interactions (direct and/or indirect) over which they had no control over, and which negatively impacted them.

With increased flexibility during lockdown, participants felt as though they were expected to be available ‘24/7’ (P12): ‘But I suppose in like a negative way as I’ve said it’s like where do you draw the line with these, because like it it’s just hard because, like you can get contacted at all times can’t you, it’s like there’s never really off an off button so’ (P12).

Participants felt this was valid in the context of working from home as students felt that they were consumed with work and unable to take ‘sick days’, which were associated with anger, frustration, guilt, and stress related to feeling as though they were not working hard enough and losing control over personal boundaries: ‘like the boundaries sort of blur and like your work and personal life just become like one like amalgamation of everything. And there isn’t really that like separation, or like boundary for yourself’ (P6). This negatively impacted participants’ wellbeing as they felt they did not have any other choice but to work, which meant they could not take the time to relax and look after their mental wellbeing.

In the context of work demands, one participant described online interactions during the lockdown as giving people an excuse to overstep and overdemand therefore taking control away. But in an attempt to regain control and set boundaries they had to become: ‘really stringent and say I only work a Wednesday and a Friday, because I was getting contacted outside my working hours’ (P12).

Some participants reported that they had trouble staying in touch with a lot of individuals at once and struggled to meet others’ expectations to interact online, describing their experience as ‘too much’ (P5) and overwhelming. However, they felt an obligation to interact online and stay ‘in the loop’ (P5). Others emphasised the struggle between controlling their time and maintaining a healthy work-life balance: ‘It takes down my barriers really because I’ve been sitting there having my chill time and then I’ll get contacted by work like why isn’t this done, it needs to be done and then it’s like well, I’ve got no choice have I? I’ve got go and do it ‘cause you’ve contacted people’ (P12).

Furthermore, many participants experienced a lack of choice and control over their exposure to content on social media. Much of social media is based on algorithms and news feeds which exposed participants to a lot of unwanted content, for example, community member posts, suggested posts, explore pages on Instagram, and TikTok videos: ‘that’s constantly on your Facebook feed, so again like it’s that thing of you can’t really escape it, because it’s always there’ (P6).

Some participants talked about seeing posts on triggering topics, such as weight loss and body image, which were harmful to their mental health due to social comparison and trying to achieve unrealistic standards. Others felt frustration over the spreading of misinformation about the pandemic. Being ‘flooded’ (P5) with COVID-19 related news information was described as ‘scaremongering’ (P2), overwhelming and stressful for participants due to feeling a lack of control over the suffering in the world: ‘I cannot keep watching this or I’m just gonna go insane because it’s just horrible, things that I have no control over […] I feel a bit powerless and that’s not a nice feeling’ (P8).

Seeing other people’s posts about going out and enjoying their life on social media also increased participants fear of missing out and loneliness. This was particularly relevant to the second lockdown when different places had different restrictions.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to understand how online interactions during lockdown impacted students’ wellbeing.

Students reported that they used online interactions to engage and communicate with friends, family, or others, keep up to date with the latest developments around the word, continue their studies and/or work during the lockdown periods. When reflecting how these interactions impacted their mental health students talked about the importance of control. For the majority of students having control over the type and length of interactions improved their experiences online and their sense of wellbeing. Previous studies have explored how important a sense of control can be for individuals and how perceived control can lead to a perceived sense or subjective wellbeing (de Quadros-Wander, McGillivray and Broadbent, Citation2014).

This is in line with the principles of Perceptual Control Theory (PCT, (Powers, Citation1973) which explains that control is essential to successful living. All living things (including humans) are continuously striving to control things that are important to them. If/when control is reduced or taken away, individuals might be experiencing psychological distress, as they fail to maintain control over important areas of their lives. The importance of control has been clearly explored in the context of mental health where individual have reported reduced levels of control when experiencing psychological distress and increased levels of control during the recovery process. This was reported across a range of difficulties and challenges (Alsawy & Mansell, Citation2013; Higginson & Mansell, Citation2008; Mansell et al., Citation2010; McEvoy et al., Citation2012; Stevenson-Taylor & Mansell, Citation2012).

In the context of the current study, reduced or no control over important areas of life took place on a worldwide scale as lockdowns were imposed and individuals were forced to isolate at home in order to reduce the spread of Covid-19. As a result, various studies have reported an increase in mental health difficulties and challenges among the general population as well as vulnerable individuals (O’Connor et al., Citation2021; Pieh et al., Citation2021; Wu et al., Citation2021).

Despite the obvious and necessary restrictions which reduced individuals’ control over important areas of their lives (seeing loves ones, going on holiday, attending events, celebrating milestones etc.), participants in the current study found new ways to restore control over those important areas of their lives. Using social media and online channels, individuals attended virtual dates, engaged in virtual tourism, took part in virtual parties, and held regular family conferences (De’ et al., Citation2020). The ability to control these interactions online was reported as increasing participants’ sense of wellbeing.

Participants reported that having control over online interactions gave them the opportunity to choose when to connect and when to disconnect. Despite restrictions and only being able to connect online, participants reported numerous benefits when able to choose how often and with whom to connect.

One area that participants reported that was positively impacted was the quality of their relationships. Students recognised that with more time available (due to the restrictions in place) and the opportunity to choose who to spent time online with, their relationships (with loved ones and others) significantly improved. It is well recognised that talking out loud or externally exploring things that might be worrying or bothering us is an effective way of relieving distress while simultaneously strengthening relationships (Jaffe, Citation2014). Participants in the current study were able to reflect on their experiences and recognised how an increase in communication led to an increase in intimacy and ability to bond with loved ones as well as new individuals.

Previous literature has reported that good communication has the potential to improve family functioning and increase resilience (Walsh, Citation2016), which was demonstrated in the current study despite the unprecedented times experienced during Covid-19 where families were separated or isolated. Interactions with trusted individuals offered students the opportunity to offload, self-disclose and become more open about their feelings, which offered relief, intimacy, social connectedness as well as reduced isolation and loneliness which is in line with current literature exploring this topic (Marciano et al., Citation2022; Nguyen et al., 2022; Winstone et al., Citation2021).

While increased communication strengthened relationships, reduced communication led to the end of certain relationships for participants. Students reported that having control over their online interactions offered the opportunity not only to connect but also disconnect and be able to end certain relationships that they no longer valued or benefited from. According to PCT, when individuals are able to identify and achieve important goals (such as maintaining or ending relationships) they experience an increased sense of control which ultimately leads to improved well-being (Mansell et al., Citation2012).

While having control over interactions was reported as improving and increasing wellbeing among participants, having limited or no control was described as negatively impacting participants.

Students experienced increased job demands and workloads due to the expectation of being available all the time because of the isolation and the lockdowns. It was inferred that due to the flexible nature of online interactions, the boundaries between work life and personal life were crossed. As a result, some students reported that they were expected to work outside their contracted working hours or when they were sick, leading to reduced feelings of control over personal boundaries. In these circumstances, students experienced increased guilt, anger, frustration, and anxiety which negatively impacted their wellbeing. This has previously been reported in literature specifically in the area of PCT (Carey et al., Citation2015) but also more recently in the context of social media use during covid (Brailovskaia et al., Citation2021). Brailovskaia et al. (Citation2021) overtly reported that ‘lack of control over important life events can be experienced as a high psychological burden and foster symptoms of anxiety, depression, and helplessness’ (Brailovskaia et al., Citation2021, p. 2)

Participants reported that in certain instances they had no control over the information available to them on social media and as a result they were exposed to negative content that evoked feelings of social comparison and fear of missing out which negatively impacted their mental health. Marciano et al. (Citation2022) explored the link between digital media use and adolescent mental health during Covid-19 and found that while friendships and one to one conversations can have positive implications for individuals and mitigate loneliness and stress, exposure to negative content, comparison and fear of missing out can have a detrimental effect (Marciano et al., Citation2022). Students in the current study talked about being increasingly exposed to posts regarding weight-loss and body image which was triggering for them.

Furthermore, excessive exposure to news-related information about the pandemic increased stress, anxiety, and depression among students leading to rumination which has also been reported in literature elsewhere (Strasser et al., Citation2022). Hong et al. (Citation2021) proposed that rumination mediated the relationship between social media exposure to COVID-19 related news and psychological distress (Hong et al., Citation2021).

When individuals experience loss of control over important areas of their lives, they strive to restore control by using any means necessary and this process might look like trial and error until control is restored (Mansell et al., Citation2012). In the current study, students mentioned that in order to restore control over their experiences they attempted to block, mute, unfollow, and delete pages or apps. This provided them with a sense of relief and improved their psychological wellbeing. Previous research has indicated that a strong perception of control has the capacity to promote psychological wellbeing and recovery from anxiety and depression related symptoms (McEvoy et al., Citation2012; Usher et al., Citation2020).

5. Conclusions

The current study aimed to gain a deeper understanding of how online interactions impacted the wellbeing of university students during lockdown. Overall, participants had both positive and negative experiences while interacting online. The importance of control was particularly evident in students’ feedback. According to students being able to control their online interactions contributed and benefited their wellbeing. On the other hand, having limited or no control over online interactions caused students to feel stressed, anxious, and experience reduced wellbeing. Therefore, exploring the link between ‘the ability to be in control’ and the impact this might have on wellbeing could be explored further.

6. Limitations

Although the current study generated meaningful data which showed parallels with current literature exploring the topic of online use during lockdown, some limitations apply. Whilst remote interviews allowed the recruitment of students from various part of the country to participate, the sample of participants were predominately white women. Therefore, the experiences of the students in this study may not be reflective of a larger, more diverse population of ethnic minorities and males. More in-depth studies could investigate the experiences of ethnic minorities and males to increase the generalisation of the current findings. Future studies might also consider the use of alternative and innovative ways of collecting data such as ‘Online Photovoice (OPV), Online Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (OIPA) and Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR)’ (Doyumğaç et al., Citation2020; Ünsal Seydooğulları, Citation2023).

Furthermore, the current study was conducted in 2022, therefore, students were required to think retrospectively about their experiences during the 2020/2021 lockdown periods. This might have impacted students’ ability to accurately reflect on their experiences and certain important information may have been forgotten or missed.

Finally, the time and location of the online interactions may have significantly impacted how students perceived their interactions. The COVID-19 lockdowns were an extremely negative experience for many students across the globe (Velavan & Meyer, Citation2021). Family illness, job losses and potential death, were factors that could have affected how students interacted and their perception of those interactions. Research has shown that individuals experiencing grief were more likely to use social media to communicate and express their grief (Varga & Varga, Citation2019), meaning that their perceptions and recollection of their interactions may have differed based on their personal circumstances.

7. Implications and future directions

The current study has several implications and recommendations for future research and practice. During times of isolation, students reported that having control over their online interactions enhanced their wellbeing and provided them with a sense of safety and normality. The development and implementation of interventions that consider the importance of control as well as meaningful relationships and social support via online interactions should be explored. These may include components that focus on promoting meaningful interactions, such as video interactions and online group activities, but which ensure that individuals have full control over most/all aspects of the interactions. Additionally, explaining how these interactions might benefit and enhance psychological wellbeing for students during times of crises could be beneficial.

Other interventions may consider promoting healthy social media use by teaching students how social media can benefit their mental health, by reinforcing the importance of controlling and filtering content; while also highlighting the potential negative impacts of excessive social media use and screen time, particularly during periods of social isolation. Furthermore, increasing students’ access to online mental health support and counselling services, with a focus on regaining control over personal and life goals, could be essential.

Educators and health professionals could also collaborate to develop student support services that promote greater choice and control for students. This may involve facilitating online interactions with other students to form meaningful relationships, strengthen peer support, and help foster a sense of belonging for students.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who took the time to share their experiences and make this study possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anamaria Churchman

Anamaria Churchman, PhD, CPsychol, is a Lecturer at The University of Manchester where she completed her PhD in Clinical Psychology. Her research interests include the role of transdiagnostic approaches (particularly Method of Levels therapy) and working therapeutically with families and young people.

Bali Jasmine Hemmings

Bali Jasmine Hemmings, MSc, PWP, is a Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner who has completed her Masters in Health and Clinical Psychology at The University of Manchester.

Anushka Basu

Anushka Basu, MSc, is currently undertaking training to qualify as a Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner which entails working with common mental health problems and delivering low-intensity CBT treatments within NHS Talking Therapies. She has completed her Masters in Health and Clinical Psychology at the University of Manchester.

References

- Alsawy, S., & Mansell, W. (2013). How do people achieve and remain at a comfortable weight?: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 6, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X13000184

- Atalan, A. (2020). Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 56, 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.06.010

- Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

- Brailovskaia, J., Stirnberg, J., Rozgonjuk, D., Margraf, J., & Elhai, J. D. (2021). From low sense of control to problematic smartphone use severity during Covid-19 outbreak: The mediating role of fear of missing out and the moderating role of repetitive negative thinking. PloS One, 16(12), e0261023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261023

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences, 48, 843–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103

- Brown, G., & Greenfield, P. M. (2021). Staying connected during stay-at-home: Communication with family and friends and its association with well-being. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.246

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11135-021-01182-Y/FIGURES/D

- Carey, T. A., Mansell, W., & Tai, S. (2015). Principles-based counselling and psychotherapy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315695778

- Cheung, J. C.-S., Chan, K. H.-W., Lui, Y.-W., Tsui, M.-S., & Chan, C. (2018). Psychological well-being and adolescents’ internet addiction: a school-based cross-sectional study in Hong Kong. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(5), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10560-018-0543-7/TABLES/6

- Churchman, A., Mansell, W., & Tai, S. (2019a). ‘A qualitative analysis of young people’s experiences of receiving a novel, client-led, psychological therapy in school’. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12259

- Churchman, A., Mansell, W., & Tai, S. (2019b). A school-based feasibility study of method of levels: a novel form of client-led counselling. Pastoral Care in Education, 37(4), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2019.1642375

- Churchman, A., Mansell, W., & Tai, S. (2020a). A school-based case series to examine the feasibility and acceptability of a PCT-informed psychological intervention that combines client-led counselling (Method of levels) and a parent–child activity (Shared goals). British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 49(4), 587–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1757622

- Churchman, A., Mansell, W., & Tai, S. (2020b). The development of a parent-child activity based on the principles of perceptual control theory. Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 13, e20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X20000203

- Churchman, A., Mansell, W., & Tai, S. (2021). A process-focused case series of a school-based intervention aimed at giving young people choice and control over their attendance and their goals in therapy. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 49(4), 565–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1815650

- Churchman, A., Mansell, W., & Tai, S. (2022). Experiences of adolescents and their guardians with a school-based combined individual and dyadic intervention. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 50(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1862052

- Çikrıkci, Ö. (2016). The effect of internet use on well-being: Meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 560–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.021

- de Quadros-Wander, S., McGillivray, J., & Broadbent, J. (2014). The influence of perceived control on subjective wellbeing in later life. Social Indicators Research, 115(3), 999–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0243-9

- De’, R., Pandey, N., & Pal, A. (2020). Impact of digital surge during Covid-19 pandemic: A viewpoint on research and practice. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102171

- Doyumğaç, İ., Tanhan, A., & Kiymaz, M. S. (2020). Understanding the most important facilitators and barriers for online education during COVID-19 through online photovoice methodology. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v10n1p166

- Fernandes, B., Nanda Biswas, U., Tan-Mansukhani, R., Vallejo, A., & Essau, C. A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on internet use and escapism in adolescents. Revista de Psicología Clínica Con Niños y Adolescentes, 7(nº 3), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2020.mon.2056

- Gabbiadini, A., Baldissarri, C., Durante, F., Valtorta, R. R., De Rosa, M., & Gallucci, M. (2020). Together apart: The mitigating role of digital communication technologies on negative affect during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 554678. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2020.554678/BIBTEX

- Garfin, D. R. (2020). Technology as a coping tool during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Implications and recommendations. Stress and Health, 36(4), 555–559. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2975

- Higginson, S., & Mansell, W. (2008). What is the mechanism of psychological change? A qualitative analysis of six individuals who experienced personal change and recovery. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 81(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608308X320125

- Hong, W., Liu, R.-D., Ding, Y., Fu, X., Zhen, R., & Sheng, X. (2021). Social media exposure and college students’ mental health during the outbreak of COVID-19: The mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of mindfulness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(4), 282–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/CYBER.2020.0387/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/CYBER.2020.0387_FIGURE3.JPEG

- Magis-Weinberg, L., Gys, C. L., Berger, E. L., Domoff, S. E., & Dahl, R. E. (2021). Positive and negative online experiences and loneliness in Peruvian adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 717-733. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12666

- Ioannidis, K., Hook, R., Goudriaan, A. E., Vlies, S., Fineberg, N. A., Grant, J. E., & Chamberlain, S. R. (2019). Cognitive deficits in problematic internet use: Meta-analysis of 40 studies. British Journal of Psychiatry, 215(5), 639–646. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.3

- Jaffe, L. (2014). How talking cures: Revealing Freud’s contributions to all psychotherapies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Juvonen, J., Schacter, H. L., & Lessard, L. M. (2021). Connecting electronically with friends to cope with isolation during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(6), 1782–1799. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407521998459

- Kharroubi, S., & Saleh, F. (2020). Are lockdown measures effective against COVID-19? Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 549692. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPUBH.2020.549692/BIBTEX

- Kim, Y., Wang, Y., & Oh, J. (2016). Digital media use and social engagement: How social media and smartphone use influence social activities of college students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.1089/CYBER.2015.0408/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/FIGURE1.JPEG

- Kumar, A., & Nayar, K. R. (2021). COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. Journal of Mental Health, 30(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1757052

- Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the context of COVID. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239.e3. 19 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

- Mansell, W., Carey, T. A., & Tai, S. J. (2012). A transdiagnostic approach to CBT using method of levels. (1st Ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203081334

- Mansell, W., Powell, S., Pedley, R., Thomas, N., & Jones, S. A. (2010). The process of recovery from bipolar I disorder: A qualitative analysis of personal accounts in relation to an integrative cognitive model. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(2), 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466509X451447

- Marciano, L., Ostroumova, M., Schulz, P. J., & Camerini, A.-L. (2022). Digital media use and adolescents’ mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 793868. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPUBH.2021.793868/BIBTEX

- Masur, P. K. (2021). Digital communication effects on loneliness and life satisfaction. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/ACREFORE/9780190228613.013.1129

- McEvoy, P., Schauman, O., Mansell, W., & Morris, L. (2012). The experience of recovery from the perspective of people with common mental health problems: Findings from a telephone survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(11), 1375–1382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.06.010

- Meyerowitz-Katz, G., Bhatt, S., Ratmann, O., Brauner, J. M., Flaxman, S., Mishra, S., Sharma, M., Mindermann, S., Bradley, V., Vollmer, M., Merone, L., & Yamey, G. (2021). Is the cure really worse than the disease? The health impacts of lockdowns during COVID-19 Commentary Handling editor Seye Abimbola. BMJ Global Health, 6(8), e006653. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006653

- Misirlis, N., Zwaan, M. H., & Weber, D. (2020). International students’ loneliness, depression and stress levels in Covid-19 crisis: The role of social media and the host university. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.12806. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.4256624

- Nguyen, M. H., Gruber, J., Marler, W., Hunsaker, A., Fuchs, J., & Hargittai, E. (2021). Staying connected while physically apart: Digital communication when face-to-face interactions are limited. New Media & Society, 24(9), 2046–2067. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820985442

- O’Connor, R. C., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., McClelland, H., Melson, A. J., Niedzwiedz, C. L., O’Carroll, R. E., O’Connor, D. B., Platt, S., Scowcroft, E., Watson, B., Zortea, T., Ferguson, E., & Robb, K. A. (2021). Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 218(6), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1192/BJP.2020.212

- Pandey, V., Astha, A., Mishra, N., Greeshma, R., Lakshmana, G., Jeyavel, S., Rajkumar, E., & Prabhu, G. (2021). Do social connections and digital technologies act as social cure during COVID-19? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 634621. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2021.634621/BIBTEX

- Pandya, A., & Lodha, P. (2021). Social connectedness, excessive screen time during COVID-19 and mental health: A review of current evidence. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 3, 45. https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.684137

- Pieh, C., Budimir, S., Delgadillo, J., Barkham, M., Fontaine, J. R. J., & Probst, T. (2021). Mental health during COVID-19 Lockdown in the United Kingdom. Psychosomatic Medicine, 83(4), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000871

- Powers, W. T. (1973). Behavior: The control of perception. Aldine Pub. Co.

- Powers, W. T. (2008). Living control systems III: The fact of control. https://philpapers.org/rec/POWLCS-2

- Saha, A., Dutta, A., & Sifat, R. I. (2021). The mental impact of digital divide due to COVID-19 pandemic induced emergency online learning at undergraduate level: Evidence from undergraduate students from Dhaka City. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.045

- Saunders, J. B., Hao, W., Long, J., King, D. L., Mann, K., Fauth-Bühler, M., Rumpf, H.-J., Bowden-Jones, H., Rahimi-Movaghar, A., Chung, T., Chan, E., Bahar, N., Achab, S., Lee, H. K., Potenza, M., Petry, N., Spritzer, D., Ambekar, A., Derevensky, J., … Poznyak, V. (2017). Gaming disorder: Its delineation as an important condition for diagnosis, management, and prevention. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.039

- Sifat, R. I. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Mental stress, depression, anxiety among the university students in Bangladesh. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(5), 609–610., 67(5), pp. 609–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020965995

- Stebleton, M. J., Kaler, L. S., & Potts, C. (2022). “Am I Even Going to Be Well-Liked in Person?”: First-year students’ social media use, sense of belonging, and mental health. Journal of College and Character, 23(3), 210–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2022.2087683

- Stevenson-Taylor, A. G. K., & Mansell, W. (2012). Exploring the role of art-making in recovery, change, and self-understanding–An interpretative phenomenological analysis of interviews with everyday creative people. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 4(3), 104. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v4n3p104

- Strasser, M. A., Sumner, P. J., & Meyer, D. (2022). COVID-19 news consumption and distress in young people: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 300, 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.007

- Strouse, G. A., McClure, E., Myers, L. J., Zosh, J. M., Troseth, G. L., Blanchfield, O., Roche, E., Malik, S., & Barr, R. (2021). Zooming through development: Using video chat to support family connections. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(4), 552–571. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.268

- Ünsal Seydooğulları, S. (2023). University students’ wellbeing and mental health during COVID-19: An online photovoice approach. Journal of Happiness and Health, 3(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.47602/johah.v3i2.60

- Usher, K., Bhullar, N., & Jackson, D. (2020). Life in the pandemic: Social isolation and mental health. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(15-16), 2756–2757. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15290

- Varga, M. A., & Varga, M. (2019). Grieving college students use of social media. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 29(4), 290–300., https://doi.org/10.1177/1054137319827426

- Velavan, T. P., & Meyer, C. G. (2021). COVID-19: A PCR-defined pandemic. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 103, 278–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.189

- Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience. The Guilford Press. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=RY1_CgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Strengthening+Family+Resilience&ots=ZkyuA1MAF3&sig=fdXtGP_w6GYjbibecIASC9C7BbY#v=onepage&q=Strengthening Family Resilience&f = false

- Winstone, L., Mars, B., Haworth, C. M. A., & Kidger, J. (2021). Social media use and social connectedness among adolescents in the United Kingdom: A qualitative exploration of displacement and stimulation. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-021-11802-9/FIGURES/4

- Wu, T., Jia, X., Shi, H., Niu, J., Yin, X., Xie, J., & Wang, X. (2021). Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117